Abstract

Protein pin array technology was used to identify subunit–subunit interaction sites in the small heat shock protein (sHSP) αB crystallin. Subunit–subunit interaction sites were defined as consensus sequences that interacted with both human αA crystallin and αB crystallin. The human αB crystallin protein pin array consisted of contiguous and overlapping peptides, eight amino acids in length, immobilized on pins that were in a 96-well ELISA plate format. The interaction of αB crystallin peptides with physiological partner proteins, αA crystallin and αB crystallin, was detected using antibodies and recorded using spectrophotometric absorbance. Five peptide sequences including 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54 in the N terminus, 75FSVNLDVK82 (β3), 131LTITSSLS138 (β8) and 141GVLTVNGP148 (β9) that form β strands in the conserved α crystallin core domain, and 155PERTIPITREEK166 in the C-terminal extension were identified as subunit–subunit interaction sites in human αB crystallin using the novel protein pin array assay. The subunit–subunit interaction sites were mapped to a three-dimensional (3D) homology model of wild-type human αB crystallin that was based on the crystal structure of wheat sHSP16.9 and Methanococcus jannaschi sHSP16.5 (Mj sHSP16.5). The subunit–subunit interaction sites identified and mapped onto the homology model were solvent-exposed and had variable secondary structures ranging from β strands to random coils and short α helices. The subunit–subunit interaction sites formed a pattern of hydrophobic patches on the 3D surface of human αB crystallin.

Keywords: αB crystallin, lens, chaperone, small heat shock protein, assembly, molecular modeling

Small heat shock proteins (sHSPs) are a superfamily of proteins with a molecular weight <40 kDa ubiquitously found in a variety of organisms (Wistow 1985). Increased expression of sHSPs occurs in cells in response to abnormal heat, oxidation, osmotic stress, radiation, and other environmental factors. Under conditions of stress, sHSPs can function as molecular chaperones in cells, interacting with unfolded or unfolding target substrate proteins to confer stability on exposed, hydrophobic surfaces and protect against aggregation (de Jong et al. 1989; Piatigorsky 1989; Horwitz 1992; Haslbeck and Buchner 2002). αB crystallin is the archetype of the sHSP family that is characterized by a conserved “α-crystallin core” domain consisting of ~80–100 residues organized as a β sandwich similar to an immunoglobulin fold (Kim et al. 1998; van Montfort et al. 2001; Narberhaus 2002). In humans, αB crystallin has been implicated in protein aggregation-related pathologies including cataract, desmin-related myopathies, cardiomyopathies, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Alexander’s disease (Iwaki et al. 1989, 1993; Stege et al. 1999; Clark and Muchowski 2000; McLean et al. 2002; Jacob et al. 2003; Wyttenbach 2004). In normal cells, αB crystallin is believed to function in the maintenance of lens-specific intermediate filaments that contribute to lens cell transparency (Nicholl and Quinlan 1994; Tardieu 1998; Quinlan and Van Den Ijssel 1999; Alizadeh et al. 2003 Alizadeh et al. 2004) and in the stabilization of partially unfolded proteins that are intermediates in mechanisms of aggregation (Horwitz et al. 1992; Muchowski et al. 1997; Derham and Harding 1999; van Boekel et al. 1999; Horwitz 2003). Although the assembly of αB crystallin subunits is associated with chaperone activity (Aquilina et al. 2004), the interactive domains responsible for assembly of homo- and heteromeric α crystallin complexes remain to be characterized. The absence of an X-ray or NMR structure for full-length αB crystallin is limiting progress in understanding the relationships between primary, secondary, and tertiary structure and the interactions necessary for subunit assembly of αB crystallin. The X-ray crystal structures of Methanococcus jannaschi sHSP16.5 (Mj sHSP16.5) and wheat sHSP16.9 suggested that sHSPs have common structural features and that the α crystallin core domain is an immunoglobulin-like fold consisting of 7–9 β strands organized in the tertiary structure as a β sandwich (Kim et al. 1998; van Montfort et al. 2001; Studer et al. 2002). In the crystal structure of Mj sHSP16.5, two categories of interactions contributed to the quaternary structure: (1) subunit–subunit interactions that resulted in the formation of a dimeric building block, and (2) dimer–dimer interactions that resulted in the formation of larger oligomeric assemblies. The crystal structures identified three hydrophobic subunit–subunit interaction sites, namely an amphipathic helix in the N terminus, a groove in the α crystallin core domain, and an I-X-I/V motif (where I is isoleucine, X is variable, and V is valine) in the C-terminal extension that were involved in formation of dimers, and was subsequently the smallest structural unit for assembly of dodecamers in Mj sHSP16.5 and 24-mers in wheat sHSP16.9 (van Montfort et al. 2001; Studer et al. 2002). Spectroscopic data suggested that the secondary and tertiary structures of αB crystallin were similar to those of Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9 (McHaourab et al. 1997; Koteiche and McHaourab 2002).

In vitro the size of the sHSP complexes may depend on the length and nature of the N terminus and C terminus extensions that flank the α crystallin core domain (Feil et al. 2001). Cryo-electron microscopy indicated that complexes of recombinant human αB crystallin existed as a broad distribution of sizes from 20 to 80 subunits. The quaternary structure observed was a hollow sphere with an internal diameter of ~10 nm (Haley et al. 2000). Human αB crystallin has slightly longer N and C termini compared to Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9, which form helical and flexible structures of 40 and 20 residues, respectively. Assembly depends on solvent conditions as well as posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation of serine residues (MacCoss et al. 2002;Horwitz 2003). Abraham and coworkers reported that truncated and phosphorylated lens αB crystallin formed assemblies that were different from those formed by full-length unmodified wild-type αB crystallin (Cherian and Abraham 1995; Thampi et al. 2002). Experiments involving C. elegans sHSPs 12.2, 12.3, and 12.6 indicated that sHSPs with short N and C termini form small assemblies and have diminished chaperone function (Leroux et al. 1997; Kokke et al. 1998). Similarly in P. furiosus sHSP, the C terminus is believed to play an important role in oligomer formation (Laksanalamai and Robb 2004). Characterization of the interactions between α crystallin dimers is expected to provide new information on the structural basis of sHSP function.

The identification and characterization of residues belonging to the subunit–subunit interaction sites in human αB crystallin, the archetype of the small heat shock protein family, are the objectives of the current report. In the absence of a crystal structure for human αB crystallin, a peptide scanning method called a protein pin array was used to identify peptide sequences in human αB crystallin that interacted with αA crystallin and αB crystallin subunits. Protein pin arrays employ peptides that represent interactive domains of proteins. Interactive domains are usually comprised of multiple sequences that are in close proximity and form a three-dimensional (3D) interactive surface. Though individual peptides only form part of the entire interactive surface, pin arrays have been successful in mapping the discrete sequences that form interactive domains in proteins. Protein pin arrays were used to map antigen epitopes in antigen-antibody interactions and several receptor-ligand interactive sites that depend on the 3D structure of the interacting partner proteins (Slootstra et al. 1996, 1997; Meloen et al. 2000, 2001; Bernard et al. 2004; Timmerman et al. 2004). While it cannot be ruled out that subunit–subunit interactions in αB crystallin require higher-order structure that cannot be detected using protein pin array assays, it is likely that the pin arrays can identify sequences important for the subunit–subunit interactions of αB crystallin. Recently a similar strategy was employed to identify oligomerization and substrate interactions sites in a protein homologous to αB crystallin, Bradyrhizobium japonicum sHSPB (Lentze and Narberhaus 2004). In the absence of a crystal or NMR structure of αB crystallin, a homology model of αB crystallin was constructed using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software and compared with the crystal structures of Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9. The results of the protein pin arrays were mapped onto the 3D-computed model for human αB crystallin. Five interactive sequences, an N terminus helix motif, three β strands in the α crystallin core domain, and a sequence containing the I-X-I/V motif in the C terminus were identified as subunit–subunit interactive sites in αB crystallin using the pin array and 3D model of αB crystallin.

Results

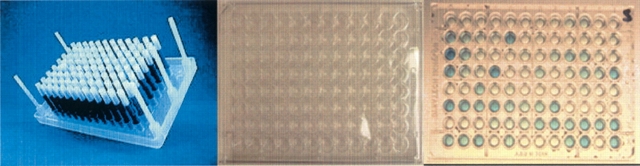

Sequential peptide fragments corresponding to the primary sequence of human αB crystallin were synthesized, immobilized on the pin arrays, and tested for interaction with myoglobin, αA crystallin, and αB crystallin (Fig. 1 ▶). The ELISA-based method used primary antibodies for myoglobin, αA crystallin, or αB crystallin and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies that turned 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate from colorless to blue when binding occurred. When the wells of the ELISA plate contained 0.06 μM myoglobin, no blue color was observed, indicating that no interaction occurred between the immobilized αB crystallin peptides and human myoglobin (Fig. 1B ▶). When each well of the ELISA plate contained 0.05 μM human αB crystallin, 18 wells were dark blue, 11 wells were light blue, and 55 wells were colorless (Fig. 1C ▶). The last three peptides of the αB crystallin pin array were the epitope for the antibody to human αB crystallin, were dark blue, and served as the positive control for the pin array experiment.

Figure 1.

(A,left) Protein pin array and ELISA assay identified interactive sequences of human αB crystallin. Sequential 8-mer peptides were synthesized on the individual tips of derivatized polyethylene pins arranged in a 96-well microtiter plate format. Each pin contained nanomoles of a specific eight-amino-acid in length peptide immobilized on it and consecutive peptides were offset by two amino acids. All peptides were covalently bonded to the surface of the plastic pins. The first peptide was 1MDIAIHHP8, and the last peptide was 168PAVTAAPK175 for the human αB crystallin. In all, 84 peptides corresponding to the 175-amino-acid primary sequence of human αB crystallin were synthesized and immobilized on 84 individual pins of the pin array (Table 2). (B,center) ELISA plate result of the negative control for interactions between human myo-globin and the human αB crystallin peptide library. Blue coloration indicates a positive interaction, and a clear solution indicates no interaction. (C,right) ELISA plate result for the interactions between human αB crystalline and the peptides of the human αB crystallin protein pin array. Blue coloration indicates a positive interaction; a clear solution indicates no interaction.

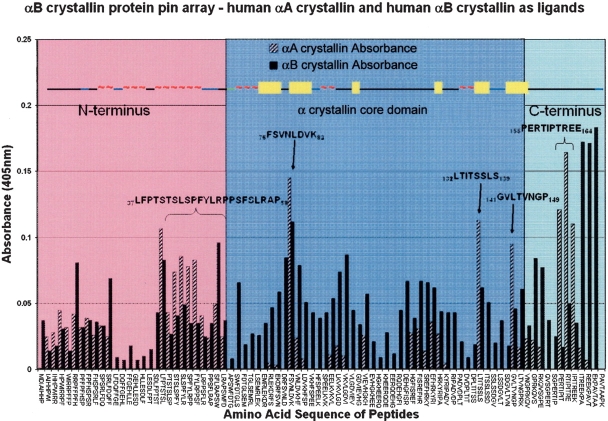

A plot of the absorbance measured (Y-axis) in each well of the ELISA plate against the 8-mer peptide sequence (X-axis) of the αB crystallin pin array resulted in a pattern of high and low absorbance that permitted the identification of interactive sequences (Fig. 2 ▶). The protein pin array identified 18 interactive sequences when human αB crystallin was the target protein (Table 1, column 2) and 11 interactive sequences when human αA crystallin was the target protein (Table 1, column 3). The well corresponding to peptide 57RTIPITRE64 was the most intense blue color when α A crystallin was the ligand, and the well corresponding to peptide 75FSVNLDVK82 was the most intense blue color when αB crystallin was the ligand. For αA crystallin, five consecutive overlapping peptides in the N terminus, three discrete nonoverlapping peptides in the α crystallin core domain, and three consecutive overlapping peptides in the C terminus region were identified by intense blue color. When αB crystallin was the ligand, more peptides had intense blue color and the absorbance pattern was similar to the pattern observed for αA crystallin. As stated above, the last three peptides of the human αB crystallin protein pin array were the epitopes of the αB crystallin antibody used and were not considered in the data analysis. Several interactive sequences that overlapped significantly in their sequence (37LFPTSTSL44, 41STSLSPFY48, 43SLSPFYLR50, 45SPFYLRPP52, 47FYLRPPSF54) and 155PERTIPIT162, 157RTIPITRE164, 159IPITREEK166) were consolidated into longer contiguous sequences 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54 and 155PERTIPITREEK166, respectively.

Figure 2.

A plot of the αB crystallin peptide vs. absorbance when human αA crystallin or human αB crystallin was used as ligand in the human αB crystallin protein pin array. Patterns of absorbance indicates the interactive sequences in human αB crystallin. Absorbance maxima were observed at three sequences in the α crystallin core domain and one in each of the extensions of the C and N termini. The X-axis lists the 8-mer peptides in order on the 84 pins of the protein pin array. The Y-axis is the absorbance measured at 405 nm in each well of the ELISA plate when αA crystallin and αB crystallin were screened using an ELISA-based colorimetric method. Interactions between human αA crystallin and the peptides of the human αB crystallin protein pin array were detected in a similar way. The height of the vertical bars represents the absorbance for each peptide and is proportional to the interaction of that peptide with the ligand protein (human αA crystallin or human αB crystallin). Absorbance readings in the range of 0.00–0.05 were observed in the absence of any ligand and were considered baseline noise. Solid black bars represent the absorbance for human αB crystallin at room temperature; diagonal striped bars represent the absorbance recorded when human αA crystallin was used as the ligand. At room temperature, interactions were not observed at every peptide, and there was a distinct pattern to the interactions. Wells corresponding to interactive peptides were blue and are the taller bars in the plot. Wells without color are short bars or no bars. Peptides that had tall bars for both the human αA crystallin and human αB crystallin experiments were selected as the sequences involved in subunit–subunit interactions, and are identified with arrows and brackets. The predicted secondary structure of human αB crystallin (~, helix; bars, β strands; black lines, unstructured stretch or loop) is at the top of the figure. The figure is divided into three structural regions. Sequences in the left (pink) were in the N-terminal extension. Sequences in the C-terminal extension are to the right (light blue), and sequences in the α crystallin core domain are in the center (dark blue).

Table 1.

Protein contacts for wt human αB crystallin peptides that interacted with either human αA crystallin or human αB crystallin

| Pin # | Peptides that bind αB crystallin | Peptides that bind αA crystallin | Internal protein contacts 4Å - hydrophobic 3Å - ionic cutoff | Exposed residues, i.e., residues capable of intermolecular interactions | Consensus subunit- subunit interaction sequences (αB↔αB, αB↔αA) |

| 5 | 11RRPFFPFH18 | — | F17→I10, H18→F54 | — | — |

| 10 | 21SRLFDQFF28 | — | R22→L55, D25→R123 | — | — |

| 18 | 37LFPTSTSL44 | 37LFPTSTSL44 | F38→T40, F38→T42 P39→ S43 |

L37, S41, L44 | |

| 20 | — | 41STSLSPFY48 | — | S41, L44, S45, P46, F47, Y48 | |

| 21 | — | 43SLSPFYLR50 | — | L44, S45, P46, F47, Y48, L49, R50 | 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54 |

| 22 | — | 45SPFYLRPP52 | — | S45, P46, F47, Y48, L49, R50, P51, P52 | |

| 23 | — | 47FYLRPPSF54 | — | F47, Y48, L49, R50, P51, P52, S53 | |

| 26 | 53SFLRAPSW60 | — | F54→H18, L55→R22, A57→ S19, W60→F118 | — | — |

| 37 | 75FSVNLDVK82 | 75FSVNLDVK82 | F75→N146, S76→R69, V77→ I98 | N78, L79, D80, V81, K82 | 75FSVNLDVK82 |

| 38 | 77VNLDVKHF84 | — | F84→L89 | — | — |

| 44 | 89LKVKVLGD96 | — | L89→F84 | — | — |

| 45 | 91VKVLGDVI98 | — | I98→V77 | — | — |

| 48 | 97VIEVHGKH104 | — | I98→V7, E99→K121, V100→L89 | — | — |

| 54 | 109DEHGFISR116 | — | — | — | — |

| 55 | 111FISREFHR118 | — | F118→W60 | — | — |

| 56 | 113SREFHRKY120 | — | F118→W60 | — | — |

| 57 | 115EFHRKYRI122 | — | F118→W60, K121→E99 | — | — |

| 65 | — | 131LTITSSLS138 | I133→V128 | L131, T132, T134, S135, S136, L137, S138 | 131LTITSSLS138 |

| 70 | 141GVLTVNGP148 | 141GVLTVNGP148 | L143→L89, N146→F75 | G141, V142, T144, V145, G247, P148 | 141GVLTVNGP148 |

| 71 | 143LTVNGPRK150 | — | K150→D127, K150→ | — | — |

| 73 | 147GPRKQVSG152 | — | K150→D127, K150→D129 | — | — |

| 74 | 149RKQVSGPE154 | — | K150 D127, K150 D129 → → | — | — |

| 77 | — | 155PERTIPIT162 | — | P155, E156, R157, T158, I159, P160, I161, T162 | |

| 78 | 157RTIPITRE164 | 157RTIPITRE164 | — | R157, T158, I159, P160, I161, T162, R163, E164 | 155PERTIPITREEK166 |

| 79 | — | 159IPITREEK166 | — | I159, P160, I161, T162, R163, E164, E165, K166 |

Column 1: the pin peptide number; column 2: the peptides that interacted with αB crystallin; column 3: the peptide sequences that interacted with αA crystallin; column 4: the intramolecular interactions identified using the protein contact algorithm (Materials and Methods); column 5: exposed residues containing side chains that are capable of forming intermolecular interactions with either αA crystallin or αB crystallin; column 6: the consensus sequences for subunit-subunit interactions involving either one αA crystallin subunit and one αB crystallin subunit or two αB crystallin subunits.

The protein pin array provided information only on the primary sequence of the interactive regions in human αB crystallin that included intramolecular interactions as well as intermolecular interactions. To distinguish between intramolecular interactions and intermolecular interactions, side-chain contacts were calculated using the 3D homology model for αB crystallin (Table 1, column 4). Protein side-chain contacts included three types of interactions: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and salt bridges. Human αB crystallin does not contain cysteines, and disulfide bonds are not involved in intramolecular interactions. Column 5 lists exposed residues in the interactive sequences that are capable of forming intermolecular interactions with either αA crystallin or αB crystallin. Of the 18 peptides that interacted strongly with αB crystallin, residues belonging to peptides 5, 10, 26, 38, 44– 45, 48, 54–57, and 71–74 were involved in intramolecular interactions and had no exposed residues capable of intermolecular interactions. Interestingly, peptides 5, 10, 26, 38, 44–45, 48, 54–57, and 71–74 that did not have any exposed residues did not show interaction with αA crystallin (column 3). These peptides were excluded from the set of sequences identified as domains for subunit–subunit interactions in αB crystallin. Based on these data, consensus sequences were identified in αB crystallin that interacted with both αA crystallin and αB crystallin (Table 1, column 6). Consensus sequences were defined as sequences that were capable of intermolecular interactions with both αA crystallin subunits and αB crystallin subunits. All 11 peptides that interacted strongly with αA crystallin were identified as αB crystallin subunit–subunit interaction sequences. Human αA crystallin and human αB crystallin are <57% homologous, and form mixed oligomers. Consensus sequences identified by the protein pin arrays are expected to be important for both αA crystallin↔αB crystallin and αB crystallin↔αB crystallin interactions.

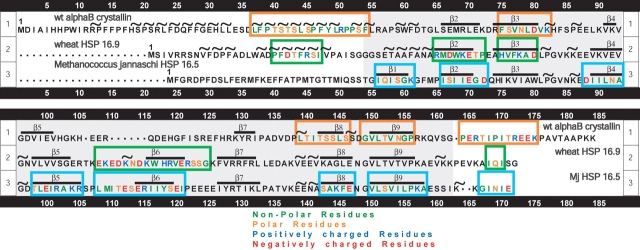

The alignment of the primary sequence for human αB crystallin with the primary sequences for wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5 resulted in good alignment of the predicted secondary structure of αB crystallin with the observed secondary of wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5 (Fig. 3 ▶). Although there was variability in the primary sequence of the N terminus, the secondary structure was largely helical in all three proteins. In the conserved α crystallin core domain, both the primary and secondary structure were similar and consisted of 7, 8, and 9 β strands in αB crystallin, sHSP16.9, and sHSP16.5, respectively. In contrast to the N terminus and the core α crystallin domain, helices and β strands were absent in the C terminus. While the I-X-I/V motif was conserved, the C termini of all three proteins were variable in sequence and length. The secondary structure of the α crystallin core domains was similar for human βB crystallin, wheat sHSP16.9, and Mj sHSP16.5, except that the β6 contained in the loop region of both wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5 was absent in αB crystallin. Subunit–subunit interaction sites (Fig. 3 ▶, orange boxes) identified using the human αB crystallin protein pin arrays aligned well with the interactive sequences identified in the crystal structures of wheat sHSP16.9 (Fig. 3 ▶, green boxes) and Mj sHSP16.5 (Fig. 3 ▶, cyan boxes). The N-terminal sequence 37LFPTSTSLPFYLRPPSF54 corresponded to the sequence 20PFDTFRSI27 that formed a helix in the crystal structure of wheat sHSP16.9. The sequences 75FSVNLDVK82 (β3), 131LTITSSLS138 (β8), and 141GVLTVNGP148 (β9) that formed strands β3, β8, and β9 in the conserved “α crystallin core domain” corresponded to the sequences EAHVFKAD (β3), VEEVKAGL (β8), and GVLTVTVP (β9) in the wheat sHSP16.9. The sequence 155PERTIPITREEK166 contained the conserved I-X-I/V motif that corresponded to the sequence EVKAIQIS in the flexible C-terminal extension of wheat sHSP16.9 crystal structure. Peptides in the loop region of αB crystallin were not identified as subunit–subunit interaction sites by the pin array.

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment, secondary structure elements, and interactive sequences for human αB crystallin, sHSP16.5, and sHSP16.9. The observed secondary structure of wheat sHSP16.9 and Methanococcus jannaschi sHSP16.5 along with the predicted secondary structure of human αB crystallin (~,α helix;-, β strand) are shown. The interactive sequences in the dodecameric quaternary structure of wheat HSP16.9 are in green boxes; the interactive sequences for the Mj sHSP16.5 24-mer structure are in blue boxes. The interactive domains identified in human αB crystallin using protein pin arrays are in orange boxes and corresponded with the interactive sequences observed in the crystal structures of Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9. In the crystal structure of wheat sHSP16.9, the α helix in the N terminus interacted with β4 and β7 in the α crystallin core domain.

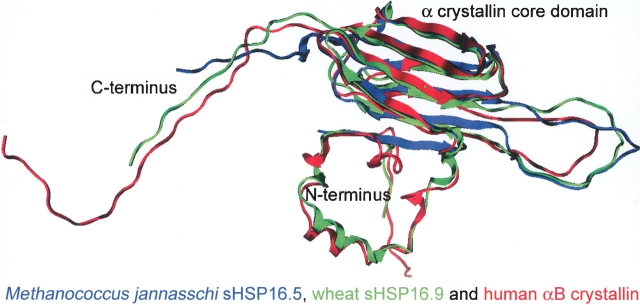

The homology model of human αB crystallin (red) contained three structural domains: the N terminus, the α crystallin core domain, and the C terminus (Fig. 4 ▶). The 65-residue N-terminal region contained three helix-turn-helix motifs in the homology model. The 89-residue α crystallin core domain formed a β sandwich that resembled an immunoglobulin fold. The last 21 residues formed the flexible C terminus that extended from the α crystallin core domain. When the 3D homology model of αB crystallin was superimposed with the crystal structures of wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5, the Cα root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the fit was 3.25 Å. Superimposition of the conserved α crystallin core domains of the three structures resulted in a Cα RMSD of 2.06Å. The α crystallin core domain of αB crystallin consisted of seven β strands organized in two β sheets forming a compact β sandwich. The first sheet was formed from β2, β3, β8, and β9, and the second sheet was formed from β4, β5, and β7 (Figs. 3 ▶, 4 ▶). The β sandwich was formed primarily by the packing of hydrophobic residues F75→N146, V77→I98, F84→L89, I133→V128, L143→L89, and N146→F75, and three ionic bonds, S76→R69, K150→D127, and K150→D129 (Table 1). The N-terminal residues were largely helical and formed three helix-turn-helix motifs. The interactions between F17→I10, H18→F54, S19→A57, R22→L55, F38→T40, F38→T42, and P39→S43 were either intrahelical or interhelical (Table 1, column 4). The interactions between D25 and W60 of the N terminus with the α crystallin core domain residues R123 and F118, respectively, may stabilize the flexible N terminus through an interaction with the α crystallin core domain (Table 1, column 4). The C-terminal extension was flexible and solvent-exposed and was not involved in any intramolecular interactions with either the N terminus or the α crystallin core domain.

Figure 4.

Superposition of the monomeric subunits of Mj sHSP16.5 (blue), wheat sHSP16.9 (green), and human αB crystallin (red). The 3D coordinates of the three structures were superimposed yielding a final RMSD of 3.25 Å. All three structures have the same basic topology. The hydrophobic N terminus is largely helical (except in Mj sHSP16.5, where the N terminus is unresolved in the X-ray structure). An immunoglobulin-like α crystallin core domain consists of β strands (11 in Mj sHSP16.5, eight in wheat sHSP16.9, and seven in αB crystallin) that form two anti-parallel β sheets connected by a flexible loop. The C-terminal extension is highly charged and unstructured. Note that the C-terminal extension is unresolved in the X-ray structure of Mj sHSP16.5.

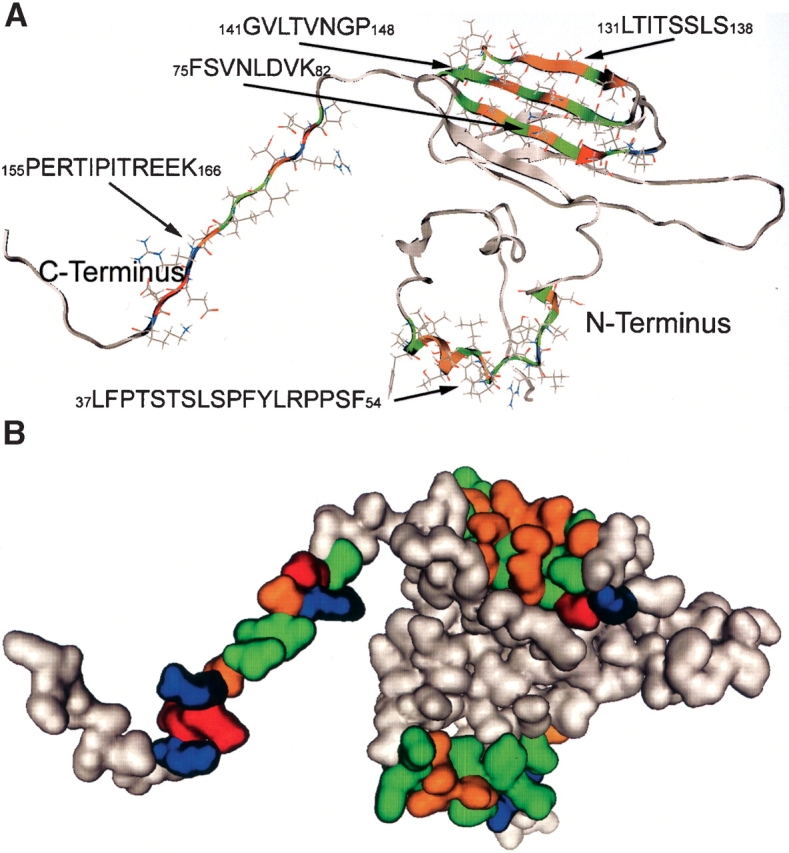

The subunit–subunit interaction sequences LFPTSTSL-SPFYLRPPSF, FSVNLDVK, LTITSSLS, GVLTVNGP, and PERTIPTREEK (green) identified by the αB crystallin protein pin array were mapped onto the 3D homology model of αB crystallin (gray) (Fig. 5A ▶). Subunit–subunit interaction sites were found in the N-terminal domain, the α crystallin core domain, and the C terminus. Interactive sequences in αB crystallin did not map to the loop region connecting the two β sheets in the α crystallin core domain. In each β strand, the surface-exposed residues (ball and stick) contributed to an interface for interaction with subunits in assembly of the α crystallin complex. The N-terminal sequence LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF formed a helix and was solvent-exposed. The α crystallin core domain sequences FSVNLDVK, LTITSSLS, and GVLTVNGP formed strands β3, β8, and β9, and buried residues from these three β strands interacted to form the compact hydrophobic core of the β sandwich. The C-terminal extension sequence PERTIPTREEK was in the unstructured region of the C terminus and was solvent-exposed.

Figure 5.

(A,top) Mapping of the interactive sequences to the 3D computer model of human αB crystallin. All five binding regions (one in the N terminus, one in the C terminus, and three in the α crystallin core domain) are solvent-exposed in the monomeric subunit. Interactive sites identified by the protein pin arrays are in color and coded as follows: blue, acidic; red, basic; green, hydrophobic; orange, hydrophilic. (B,bottom) A space-filling representation of human αB crystallin using the same colors as in A.

A space-filled model of αB crystallin was generated to view the structural topology of the αB crystallin subunit–subunit interactions sites (Fig. 5B ▶). The hydrophobic surface is presented as green, hydrophilic surface is orange, and charged surface is red or blue for positive or negative charges, respectively. The surfaces not involved in the subunit–subunit interaction are white. The N-terminal helical sequence LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF was solvent-exposed, with an exposed hydrophobic surface calculated to be 79%. The hydrophobic surface for the sequences FSVNLDVK, LTITSSLS, and GVLTVNGP that formed β3, β8, and β9 was calculated to be 65%, 68%, and 71%, respectively, and an average of 68% for the interface formed by all three β strands. The calculated hydrophobic surface for the C-terminal extension PERTIPTREEK was 58% hydrophobic. The high proportion of hydrophobic surface in the interactive sequences was consistent with the importance of hydrophobic side chains in interactions between human αB crystallin subunits.

Discussion

The results obtained using the αB crystallin protein pin array identified five consensus sequences involved in the interactions between subunits of αB crystallin and αA crystallin: 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54, 75FSVNLDVK82, 131LTITSSLS138, 141GVLTVNGP148, and 155PERTIPI-TREEK166. Although several groups have identified individual residues that might be important for structure and/or function of αB crystallin, the results reported in this paper are the first to identify specific interactive sequences in αB crystallin that might be important in both structure and function. The sequences identified using protein pin arrays were consistent with interactive sequences identified using the X-ray crystal structures of Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9 (Kim et al. 1998; van Montfort et al. 2001). In spite of the remarkable overlap in the interacting sequences of αB crystallin, wheat sHSP16.9, and Mj sHSP16.5, it is intriguing that αB crystallin does not form mono-disperse assemblies as observed in wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5. Although the α crystallin core domain is highly conserved, the N- and C-termini of αB crystallin are not only longer but vary significantly in sequence compared to those of wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5. These differences in the primary sequence can account for the variability in the quaternary structure and the observed poly-dispersity of αB crystallin assemblies in solution. The 3D structural model of human αB crystallin constructed using the 2.8 Å crystal structure of wheat sHSP16.9 contained an “α crystallin core” domain composed of seven β strands that formed a compact β sandwich characteristic of sHSPs, and agrees remarkably well with previous homology models (Muchowski et al. 1999b; Feil et al. 2001; van Montfort et al. 2001; Guruprasad and Kumari 2003). Superposition of the human αB crystallin homology model with the wheat sHSP16.9 and Mj sHSP16.5 crystal structures resulted in remarkable overlap that agreed with the secondary structure predicted by McHaourab using electron spin resonance (ESR) data (Koteiche et al. 1998; Koteiche and McHaourab 1999). Point mutations of conserved residues in αB crystallin that had little or no effect on complex assembly or chaperone function were outside the interactive sequences identified using protein pin arrays (Plater et al. 1996; Hepburne-Scott and Crabbe 1999; Muchowski et al. 1999a; Derham et al. 2001). When mutations were made in B. japonicum sHSPH (small heat shock protein H, found in mammals) within sequences that were homologous to those identified by the αB crystallin pin arrays (F118, I124, S133), smaller assemblies were observed, whereas mutations made outside of the sequences identified by the pin array (H83, E87, G102, D109, E110) did not change the oligomeric assembly of sHSPH (Lentze et al. 2003). N78D and N146D mutations in 76FSVNLDVK83 and 141GVLTVNGP149 resulted in larger oligomeric assemblies (Gupta and Srivastava 2004) that were consistent with the pin array results that identified these sites as subunit–subunit interaction sites. Together, these data reinforce the importance of the α crystallin core domain in dimerization and the role of the N and C termini of αB crystallin in higher-order assembly.

Deletion of the N-terminal conserved motif SRLF-DQFFG in both αA and αB crystallin resulted in altered subunit exchange dynamics but did not change the oligomer size distribution in either protein (Pasta et al. 2003). Although the sequence21SRLFDQFF28 interacted strongly with αB crystallin, there was no significant interaction with αA crystallin. In addition, the 3D model of αB crystallin indicated that the sequence SRLFDQFFG was involved in intramolecular interactions and stabilization of the N terminus. αB crystallin truncation mutants in which the first 56 residues in the N terminus and the last 18 residues in the C terminus and αA crystallin N- and C-terminal truncation mutants in which residues corresponding to the αB crystallin sequences 1–56, 1–65, and 1–85 were deleted resulted in smaller oligomers that are consistent with the pin array data (Bova et al. 2000; Feil et al. 2001). The pin array identified the N-terminal sequence 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54 and the C-terminal sequence 155PERTIPITREEK166 that appear in these deletion regions. Cross-linking experiments between αA crystallin and αB crystallin also suggested that C terminus extensions in both αA crystallin and αB crystallin are in close proximity in the oligomer (Swaim et al. 2004). It is likely that the sequences 37LFPTSTSLSPFYLRPPSF54 and 155PERTIPITREEK166 are involved in higher-order assembly and are not involved in the dimer formation. The α crystallin core domain sequences 75FSVNLDVK82, 131LTITSSLS138, and 141GVLTVNGP148 may contribute to the formation of a dimer interface. This hypothesis is consistent with previous experiments that found the conserved C-terminal motif I-X-I to be critical for assembly but not for dimer formation (Kim et al. 1998; Studer et al. 2002; Thampi and Abraham 2003) and the α crystallin core domain to be the structural determinant of dimerization (Koteiche and McHaourab 2002). Domain swapping of the N and C termini between C. elegans sHSP12.2 and αB crystallin showed that the N and C termini of αB crystallin were responsible for higher-order assemblies (Kokke et al. 2001). These independent reports support the hypothesis that the N terminus sequence 37LFPTSTSLPFYLRPPSF54 and the C terminus sequence 155PERTIPITREEK166 are important for assembly. The αA crystallin C terminus truncation mutations (1–168 and 1–172) that were outside the homologous αB crystallin C terminus sequence 155PERTIPITREEK166, identified by the pin array did not alter the oligomeric assembly (Bova et al. 2000). When the αA crystallin C terminus was truncated (1–157, 1–162, 1–163) to include the homologous αB crystallin C terminus sequence 155PER-TIPITREEK166, identified by the pin array, a dramatic effect on the oligomeric assembly was observed (Bova et al. 2000).

Recent studies exploring the role of multiple sequences in the chaperone function of αB crystallin suggest that the when αB crystallin acts as a molecular chaperone, sequences identified in this report are important for selective interactions of αB crystallin with a diverse number of target proteins (Putilina et al. 2003). The effectiveness of the protein pin arrays in identifying interactive sequences is due, in part, to the fact that the β strand-rich α crystallin core domain forms a large extended solvent-exposed surface that may not require significant contributions dependent upon 3D molecular organization. Unlike enzymes and antibodies, which have highly specific interactions with partner proteins and have specialized 3D tertiary structures for these interactions, molecular chaperones interact selectively, rather than specifically, with a variety of proteins. Multiple domains of varying affinity are expected to be advantageous in adaptation of molecular chaperones to variable domains exposed on the surfaces of partially unfolded or unfolding proteins. The 3D model of the structure of the α crystallin core domain, conserved in most sHSPs, was remarkably similar to the crystal structure for Mj sHSP16.5 and wheat sHSP16.9, suggesting that structural conservation of the α crystallin core domain in the absence of primary sequence conservation may be important for the function of sHSPs. Even though the sequence homology in the conserved α crystallin core domain is <40% in the sHSPs studied, the α crystallin core domain interactive sequences identified in this report corresponded to α strands in the structures of all three sHSPs and suggest a preference for that structural motif in sHSPs (Caspers et al. 1995). The αA crystallin mini-chaperone identified by Sharma et al. (2000) using proteolysis and the Neurospora crassa sHSP30 functional domains identified by Narberhaus (2002) using two-hybrid analysis overlapped with the interactive sequences identified by the protein pin arrays (Sharma et al. 2000; Plesofsky and Brambl 2002). The current results are consistent with a binding model involving multiple interactive sites on the surface of the sHSPs and suggest a complex multidomain mechanism for the adaptive and selective binding of ligands to sHSPs with a variety of substrates under conditions of cellular stress. There is an intriguing possibility that a conserved set of interactive domains on the surface of the conserved α crystallin core domain in sHSPs can vary their selective affinity dynamically for adaptation to a diverse set of interactive sequences on target proteins. The structure-function relationships established by the protein pin arrays and the 3D model of αB crystallin will enable site direct mutational analyses of these structurally and functionally important sequence motifs in αB crystallin and other homologous small heat shock proteins. The results confirm the utility of protein pin arrays for the identification of functional sequences that are involved in binding filaments and binding and preventing the unfolding and aggregation of chaperone target proteins.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of pins, binding, and detection of peptides binding to ligand proteins

The αB crystallin protein pin array was designed to measure the binding of multiple peptides to either myoglobin or αA crystallin or αB crystallin in a parallel and simultaneous manner. Peptides corresponding to residues 1–175 of human αB crystallin were synthesized employing a simultaneous peptide synthesis strategy developed by Geysen, called Multipin Peptide Synthesis (Mimotopes) (Geysen 1990; Chin et al. 1997). These peptides were synthesized on derivatized polyethylene pins arranged in a microtiter plate format (Fig. 1A ▶). Each peptide was eight amino acids in length, and consecutive peptides were offset by two amino acids. All peptides were covalently bonded to the surface plastic pins. The first peptide was 1MDIAIHHP8, and the last peptide was168PAVTAAPK175 for the human αB crystallin. Eighty-four peptides corresponding to the 175-amino-acid primary sequence of human αB crystallin were synthesized. Human Myoglobin (cat. no. 6036) and mouse anti-human Myoglobin antibody (cat. no. M7773) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant human αA and αB crystallin were expressed and purified to greater than 98% purity as determined by SDS-PAGE (Muchowski et al. 1999b). Anti-human αA crystallin (cat. no. SPA-221) and anti-human αB crystallin (cat. no. SPA-222) antibodies were purchased from Stressgen. After synthesis, the pins were precoated at room temperature with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% Tween-20, and 0.1% sodium azide in 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.2) (PBS) for 1 h, and washed three times for 10 min each with 10 mM PBS. To screen for binding to the peptides, fixed concentrations of myoglobin, αA crystallin, or αB crystallin were dissolved in 10 mM PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The pin array was washed three times for 10 min each with 10 mM PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20. Monoclonal/polyclonal primary antibodies for myoglobin, αA crystallin, or αB crystallin were diluted into PBS buffer, added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the pin array was washed three times for 10 min each with 10 mM PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20. Anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate secondary antibodies were diluted into PBS buffer, added to each well, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The pin array was washed three times for 10 min each with 10 mM PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20. A chromogenic substrate of horseradish peroxidase 3,3′,5,5′-Tetra-methylbenzidine (TMB) (Pharmingen) which is colorless was added, and the reaction was carried out for 45 min. A positive reaction resulted in the formation of a blue color. The reaction was stopped by adding 6N sulfuric acid, which changed the color from blue to yellow. The absorption at 450 nm was measured by an ELISA reader (BioTek). The pin array was regenerated by sonicating in a water bath (VWR Aquasonic) with 100 mM PBS, containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 0.1% 2-mercap-toethanol at 60°C for 10 min. Next, the pin array was rinsed three times in deionized water, preheated to 60°C for 30 sec each time, and shaken in water preheated at 60°C for 30 min. The pin array was then washed with methanol at 60°C for 15 sec and air-dried and stored at −20°C for future use. Each ligand was assayed 2–5 times against the human αB crystallin protein pin array peptides. A single pin array was used for all experiments and did not show any significant decrease in efficiency, even after repeated use up to 30 times.

Molecular modeling of human αB crystallin

The homology modeling program Molecular Operating Environment (Chemical Computing Group) was used to construct the 3D homology model of human αB crystallin. MOE employs a number of techniques including and not limited to multiple sequence alignment, structure superposition, contact analyzer, and fold identification to develop homology models based on available high-resolution crystal and/or NMR structures of the template protein molecule (Levitt 1992). It also uses advanced techniques such as analysis of the stereochemical quality of the predicted models which takes into account parameters like planarity, chirality, φ/ψ preferences, χ angles, nonbonded contact distances, unsatisfied donors, and acceptors (Fechteler et al. 1995). The overall result agreed well with existing biochemical information for the αB crystallin structure.

The wheat sHSP16.9 crystal structure was chosen as the template for the homology modeling of human αB crystallin because the wheat sHSP16.9 has the highest degree of sequence similarity with human αB crystallin (40% in the α crystallin core domain and 25.4% overall) of all the available crystal structures of sHSPs. In building the homology model of human αB crystallin, the primary sequence of human αB crystallin was first coarsely aligned to that of the template protein wheat sHSP16.9 primary sequence using ClustalX (Jeanmougin et al. 1998; Aiyar 2000). The predicted secondary structure of human αB crystallin was then obtained (JPhred) and verified with the available spin labeling information about the structural elements (Koteiche and McHaourab 1999). The verified predicted secondary structure of human αB crystallin (Fig. 4 ▶) was then structurally aligned with the observed secondary structure of the wheat sHSP16.9. This alignment was used by MOE to create a series of 10 energy-minimized putative models. Each model was evaluated using the ModelEval module of MOE, and the best model was picked as the final model. This model was further verified by Procheck (Morris et al. 1992).

For calculation of the percent surface that was hydrophobic for the subunit–subunit interaction sequences, an electrostatic potential was applied to the homology model and a script was used to generate the hydrophobic surface area based on the hydrophobic residues. Internal residue interactions were identified using the Protein Contact module of MOE.

Table 2.

Sequential 8-mer peptides of human αB crystallin that were synthesized in a protein pin array format

| # | Peptide | Hydrophobicity | Mol. wt. (Da) | # | Peptide | Hydrophobicity | Mol. wt. (Da) |

| 1 | MDIAIHHP | 0.67 | 915.09 | 43 | SPEELKVK | 0.04 | 911.07 |

| 2 | IAIHHPWI | 1.12 | 968.17 | 44 | EELKVKVL | 0.32 | 939.16 |

| 3 | IHHPWIRR | 0.6 | 1096.31 | 45 | LKVKVLGD | 0.39 | 853.06 |

| 4 | HPWIRRPF | 0.67 | 1090.31 | 46 | VKVLGDVI | 0.68 | 824.02 |

| 5 | WIRRPFFP | 0.88 | 1100.35 | 47 | VLGDVIEV | 0.72 | 824.97 |

| 6 | RRPFFPFH | 0.62 | 1085.3 | 48 | GDVIEVHG | 0.37 | 806.87 |

| 7 | PFFPFHSP | 0.95 | 957.12 | 49 | VIEVHGKH | 0.36 | 900.04 |

| 8 | FPFHSPSR | 0.51 | 956.09 | 50 | EVHGKHEE | −0.18 | 945.99 |

| 9 | FHSPSRLF | 0.63 | 972.13 | 51 | HGKHEERQ | −0.41 | 1002.06 |

| 10 | SPSRLFDQ | 0.27 | 931.03 | 52 | KHEERQDE | −0.6 | 1052.08 |

| 11 | SRLFDQFF | 0.63 | 1041.19 | 53 | EERQDEHG | −0.47 | 980.96 |

| 12 | LFDQFFGE | 0.68 | 984.09 | 54 | RQDEHGFI | 0.14 | 983.06 |

| 13 | DQFFGEHL | 0.47 | 974.05 | 55 | DEHGFISR | 0.16 | 942.01 |

| 14 | FFGEHLLE | 0.73 | 973.11 | 56 | HGFISREF | 0.48 | 974.1 |

| 15 | GEHLLESD | 0.18 | 880.92 | 57 | FISREFHR | 0.35 | 1073.24 |

| 16 | HLLESDLF | 0.7 | 955.09 | 58 | SREFHRKY | −0.1 | 1104.25 |

| 17 | LESDLFPT | 0.59 | 903.02 | 59 | EFHRKYRI | 0.13 | 1130.33 |

| 18 | SDLFPTST | 0.49 | 848.93 | 60 | HRKYRIPA | 0.11 | 1022.23 |

| 19 | LFPTSTSL | 0.79 | 847 | 61 | KYRIPADV | 0.28 | 943.12 |

| 20 | PTSTSLSP | 0.44 | 770.86 | 62 | RIPADVDP | 0.28 | 863.98 |

| 21 | STSLSPFY | 0.66 | 882.99 | 63 | PADVDPLT | 0.42 | 808.9 |

| 22 | SLSPFYLR | 0.72 | 964.15 | 64 | DVDPLTIT | 0.55 | 854.97 |

| 23 | SPFYLRPP | 0.7 | 958.15 | 65 | DPLTITSS | 0.49 | 814.91 |

| 24 | FYLRPPSF | 0.83 | 1008.21 | 66 | LTITSSLS | 0.7 | 802.94 |

| 25 | LRPPSFLR | 0.57 | 967.2 | 67 | ITSSLSSD | 0.35 | 790.84 |

| 26 | PPSFLRAP | 0.61 | 866.05 | 68 | SSLSSDGV | 0.25 | 732.75 |

| 27 | SFLRAPSW | 0.71 | 945.1 | 69 | LSSDGVLT | 0.5 | 772.86 |

| 28 | LRAPSWFD | 0.62 | 973.11 | 70 | SDGVLTVN | 0.37 | 785.85 |

| 29 | APSWFDTG | 0.56 | 861.92 | 71 | GVLTVNGP | 0.57 | 737.85 |

| 30 | SWFDTGLS | 0.64 | 893.96 | 72 | LTVNGPRK | 0.16 | 866.03 |

| 31 | FDTGLSEM | 0.44 | 880.99 | 73 | VNGPRKQV | 0.04 | 879.02 |

| 32 | TGLSEMRL | 0.4 | 888.07 | 74 | GPRKQVSG | −0.04 | 809.92 |

| 33 | LSEMRLEK | 0.16 | 987.2 | 75 | RKQVSGPE | −0.12 | 881.99 |

| 34 | EMRLEKDR | −0.27 | 1058.24 | 76 | QVSGPERT | 0.04 | 854.93 |

| 35 | RLEKDRFS | −0.12 | 1032.18 | 77 | SGPERTIP | 0.23 | 837.95 |

| 36 | EKDRFSVN | −0.13 | 976.06 | 78 | PERTIPIT | 0.49 | 908.09 |

| 37 | DRFSVNLD | 0.19 | 947.02 | 79 | RTIPITRE | 0.27 | 967.16 |

| 38 | FSVNLDVK | 0.44 | 903.04 | 80 | IPITREEK | 0.16 | 967.15 |

| 39 | VNLDVKHF | 0.46 | 953.1 | 81 | ITREEKPA | −0.02 | 925.07 |

| 40 | LDVKHFSP | 0.47 | 924.07 | 82 | REEKPAVT | −0.1 | 911.04 |

| 41 | VKHFSPEE | 0.19 | 954.06 | 83 | EKPAVTAA | 0.19 | 767.89 |

| 42 | HFSPEELK | 0.25 | 968.09 | 84 | PAVTAAPK | 0.36 | 735.89 |

Columns 2 and 6: The peptide sequence. Columns 3 and 7: Hydrophobicity (arbitrary units) as provided by manufacturer (Mimotopes). Columns 4 and 8: The calculated molecular weight as provided by the manufacturer (Mimotopes).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Christophe Verlinde, Dr. Elinor Adman, Dr. Andrew Farr, and James Dooley for technical support with molecular modeling. Supported by EY04542 from the NEI.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.041152805.

References

- Aiyar, A. 2000. The use of CLUSTAL W and CLUSTAL X for multiple sequence alignment. Methods Mol. Biol. 132 221–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, A., Clark, J., Seeberger, T., Hess, J., Blankenship, T., and FitzGerald, P.G. 2003. Targeted deletion of the lens fiber cell-specific intermediate filament protein filensin. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44 5252–5258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2004. Characterization of a mutation in the lens-specific CP49 in the 129 strain of mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45 884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina, J.A., Benesch, J.L., Ding, L.L., Yaron, O., Horwitz, J., and Robinson, C.V. 2004. Phosphorylation of αB-crystallin alters chaperone function through loss of dimeric substructure. J. Biol. Chem. 279 28675–28680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, J., Harb, C., Mortier, E., Quemener, A., Meloen, R.H., Vermot-Desroches, C., Wijdeness, J., van Dijken, P., Grotzinger, J., Slootstra, J.W., et al. 2004. Identification of an interleukin-15α receptor-binding site on human interleukin-15. J. Biol. Chem. 279 24313–24322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bova, M.P., McHaourab, H.S., Han, Y., and Fung, B.K. 2000. Subunit exchange of small heat shock proteins. Analysis of oligomer formation of αA-crystallin and Hsp27 by fluorescence resonance energy transfer and site-directed truncations. J. Biol. Chem. 275 1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers, G.J., Leunissen, J.A., and de Jong, W.W. 1995. The expanding small heat-shock protein family, and structure predictions of the conserved “α-crystallin domain”. J. Mol. Evol. 40 238–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian, M. and Abraham, E.C. 1995. Decreased molecular chaperone property of α-crystallins due to posttranslational modifications. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J., Fell, B., Shapiro, M.J., Tomesch, J., Wareing, J.R., and Bray, A.M. 1997. Magic angle spinning NMR for reaction monitoring and structure determination of molecules attached to multipin crowns. J. Org. Chem. 62 538–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.I. and Muchowski, P.J. 2000. Small heat-shock proteins and their potential role in human disease. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, W.W., Hendriks, W., Mulders, J.W., and Bloemendal, H. 1989. Evolution of eye lens crystallins: The stress connection. Trends Biochem Sci. 14 365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derham, B.K. and Harding, J.J. 1999. α-crystallin as a molecular chaperone. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18 463–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derham, B.K., van Boekel, M.A., Muchowski, P.J., Clark, J.I., Horwitz, J., Hepburne-Scott, H.W., de Jong, W.W., Crabbe, M.J., and Harding, J.J. 2001. Chaperone function of mutant versions of α A- and α B-crystallin prepared to pinpoint chaperone binding sites. Eur. J. Biochem. 268 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechteler, T., Dengler, U., and Schomburg, D. 1995. Prediction of protein three-dimensional structures in insertion and deletion regions: A procedure for searching data bases of representative protein fragments using geometric scoring criteria. J. Mol. Biol. 253 114–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil, I.K., Malfois, M., Hendle, J., van Der Zandt, H., and Svergun, D.I. 2001. A novel quaternary structure of the dimeric α-crystallin domain with chaperone-like activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276 12024–12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geysen, H.M. 1990. Molecular technology: Peptide epitope mapping and the pin technology. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 21 523–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R. and Srivastava, O.P. 2004. Effect of deamidation of asparagine 146 on functional and structural properties of human lens αB-crystallin. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruprasad, K. and Kumari, K. 2003. Three-dimensional models corresponding to the C-terminal domain of human αA- and αB-crystallins based on the crystal structure of the small heat-shock protein HSP16.9 from wheat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 33 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley, D.A., Bova, M.P., Huang, Q.L., McHaourab, H.S., and Stewart, P.L. 2000. Small heat-shock protein structures reveal a continuum from symmetric to variable assemblies. J. Mol. Biol. 298 261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck, M. and Buchner, J. 2002. Chaperone function of sHsps. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 28 37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburne-Scott, H.W. and Crabbe, M.J. 1999. Maintenance of chaperone-like activity despite mutations in a conserved region of murine lens αB crystallin. Mol. Vis. 5 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, J. 1992. α-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89 10449–10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. α-crystallin. Exp. Eye Res. 76 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, J., Emmons, T., and Takemoto, L. 1992. The ability of lens α crystallin to protect against heat-induced aggregation is age-dependent. Curr. Eye Res. 11 817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki, T., Kume-Iwaki, A., Liem, R.K., and Goldman, J.E. 1989. α B-crystallin is expressed in non-lenticular tissues and accumulates in Alexander’s disease brain. Cell 57 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki, T., Iwaki, A., Tateishi, J., Sakaki, Y., and Goldman, J.E. 1993. α B-crystallin and 27-kd heat shock protein are regulated by stress conditions in the central nervous system and accumulate in Rosenthal fibers. Am. J. Pathol. 143 487–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, J., Robertson, N.J., and Hilton, D.A. 2003. The clinicopathological spectrum of Rosenthal fibre encephalopathy and Alexander’s disease: A case report and review of the literature. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 74 807–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanmougin, F., Thompson, J.D., Gouy, M., Higgins, D.G., and Gibson, T.J. 1998. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23 403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.K., Kim, R., and Kim, S.H. 1998. Crystal structure of a small heat-shock protein. Nature 394 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokke, B.P., Leroux, M.R., Candido, E.P., Boelens, W.C., and de Jong, W.W. 1998. Caenorhabditis elegans small heat-shock proteins Hsp12.2 and Hsp12.3 form tetramers and have no chaperone-like activity. FEBS Lett. 433 228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokke, B.P., Boelens, W.C., and de Jong, W.W. 2001. The lack of chaperone-like activity of Caenorhabditis elegans Hsp12.2 cannot be restored by domain swapping with human αB-crystallin. Cell Stress Chaperones 6 360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koteiche, H.A. and McHaourab, H.S. 1999. Folding pattern of the α-crystallin domain in αA-crystallin determined by site-directed spin labeling. J. Mol. Biol. 294 561–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. The determinants of the oligomeric structure in Hsp16.5 are encoded in the α-crystallin domain. FEBS Lett. 519 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koteiche, H.A., Berengian, A.R., and McHaourab, H.S. 1998. Identification of protein folding patterns using site-directed spin labeling. Structural characterization of a β-sheet and putative substrate binding regions in the conserved domain of α A-crystallin. Biochemistry 37 12681–12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laksanalamai, P. and Robb, F.T. 2004. Small heat shock proteins from extremophiles: A review. Extremophiles 8 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentze, N. and Narberhaus, F. 2004. Detection of oligomerisation and substrate recognition sites of small heat shock proteins by peptide arrays. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentze, N., Studer, S., and Narberhaus, F. 2003. Structural and functional defects caused by point mutations in the α-crystallin domain of a bacterial α-heat shock protein. J. Mol. Biol. 328 927–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, M.R., Melki, R., Gordon, B., Batelier, G., and Candido, E.P. 1997. Structure-function studies on small heat shock protein oligomeric assembly and interaction with unfolded polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 272 24646–24656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, M. 1992. Accurate modeling of protein conformation by automatic segment matching. J. Mol. Biol. 226 507–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCoss, M.J., McDonald, W.H., Saraf, A., Sadygov, R., Clark, J.M., Tasto, J.J., Gould, K.L., Wolters, D., Washburn, M., Weiss, A., et al. 2002. Shotgun identification of protein modifications from protein complexes and lens tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 7900–7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaourab, H.S., Berengian, A.R., and Koteiche, H.A. 1997. Site-directed spin-labeling study of the structure and subunit interactions along a conserved sequence in the α-crystallin domain of heat-shock protein 27. Evidence of a conserved subunit interface. Biochemistry 36 14627–14634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, P.J., Kawamata, H., Shariff, S., Hewett, J., Sharma, N., Ueda, K., Breakefield, X.O., and Hyman, B.T. 2002. TorsinA and heat shock proteins act as molecular chaperones: Suppression of α-synuclein aggregation. J. Neurochem. 83 846–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloen, R.H., Puijk, W.C., and Slootstra, J.W. 2000. Mimotopes: Realization of an unlikely concept. J. Mol. Recognit. 13 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloen, R.H., Langeveld, J.P., Schaaper, W.M., and Slootstra, J.W. 2001. Synthetic peptide vaccines: Unexpected fulfillment of discarded hope? Biologicals 29 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, A.L., MacArthur, M.W., Hutchinson, E.G., and Thornton, J.M. 1992. Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins 12 345–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski, P.J., Bassuk, J.A., Lubsen, N.H., and Clark, J.I. 1997. Human α B-crystallin. Small heat shock protein and molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 272 2578–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski, P.J., Hays, L.G., Yates 3rd, J.R., and Clark, J.I. 1999a. ATP and the core “α-Crystallin” domain of the small heat-shock protein αB-crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 274 30190–30195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski, P.J., Wu, G.J., Liang, J.J., Adman, E.T., and Clark, J.I. 1999b. Site-directed mutations within the core “α-crystallin” domain of the small heat-shock protein, human αB-crystallin, decrease molecular chaperone functions. J. Mol. Biol. 289 397–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narberhaus, F. 2002. α-crystallin-type heat shock proteins: Socializing mini-chaperones in the context of a multichaperone network. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66 64–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholl, I.D. and Quinlan, R.A. 1994. Chaperone activity of α-crystallins modulates intermediate filament assembly. EMBO J. 13 945–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasta, S.Y., Raman, B., Ramakrishna, T., and Rao Ch, M. 2003. Role of the conserved SRLFDQFFG region of α-crystallin, a small heat shock protein. Effect on oligomeric size, subunit exchange, and chaperone-like activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278 51159–51166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatigorsky, J. 1989. Lens crystallins and their genes: Diversity and tissue-specific expression. FASEB J. 3 1933–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plater, M.L., Goode, D., and Crabbe, M.J. 1996. Effects of site-directed mutations on the chaperone-like activity of αB-crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 271 28558–28566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesofsky, N. and Brambl, R. 2002. Analysis of interactions between domains of a small heat shock protein, Hsp30 of Neurospora crassa. Cell Stress Chaperones 7 374–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putilina, T., Skouri-Panet, F., Prat, K., Lubsen, N.H., and Tardieu, A. 2003. Subunit exchange demonstrates a differential chaperone activity of calf α-crystallin toward β LOW- and individual γ-crystallins. J. Biol. Chem. 278 13747–13756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, R. and Van Den Ijssel, P. 1999. Fatal attraction: When chaperone turns harlot. Nat. Med. 5 25–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slootstra, J.W., Puijk, W.C., Ligtvoet, G.J., Langeveld, J.P., and Meloen, R.H. 1996. Structural aspects of antibody-antigen interaction revealed through small random peptide libraries. Mol. Divers. 1 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slootstra, J.W., Puijk, W.C., Ligtvoet, G.J., Kuperus, D., Schaaper, W.M., and Meloen, R.H. 1997. Screening of a small set of random peptides: A new strategy to identify synthetic peptides that mimic epitopes. J. Mol. Recognit. 10 217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stege, G.J., Renkawek, K., Overkamp, P.S., Verschuure, P., van Rijk, A.F., Reijnen-Aalbers, A., Boelens, W.C., Bosman, G.J., and de Jong, W.W. 1999. The molecular chaperone αB-crystallin enhances amyloid β neurotoxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 262 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer, S., Obrist, M., Lentze, N., and Narberhaus, F. 2002. A critical motif for oligomerization and chaperone activity of bacterial α-heat shock proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 269 3578–3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaim, C.L., Smith, D.L., and Smith, J.B. 2004. The reaction of α-crystallin with the cross-linker 3, 3′-dithiobis (sulfosuccinimidyl propionate) demonstrates close proximity of the C termini of αA and αB in the native assembly. Protein Sci. 13 2832–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu, A. 1998. α-Crystallin quaternary structure and interactive properties control eye lens transparency. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 22 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thampi, P. and Abraham, E.C. 2003. Influence of the C-terminal residues on oligomerization of α A-crystallin. Biochemistry 42 11857–11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thampi, P., Hassan, A., Smith, J.B., and Abraham, E.C. 2002. Enhanced C-terminal truncation of αA- and αB-crystallins in diabetic lenses. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43 3265–3272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman, P., Van Dijk, E., Puijk, W., Schaaper, W., Slootstra, J., Carlisle, S.J., Coley, J., Eida, S., Gani, M., Hunt, T., et al. 2004. Mapping of a discontinuous and highly conformational binding site on follicle stimulating hormone subunit-β (FSH-β) using domain Scan and Matrix Scan technology. Mol. Divers. 8 61–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel, M.A., de Lange, F., de Grip, W.J., and de Jong, W.W. 1999. Eye lens αA- and αB-crystallin: Complex stability versus chaperone-like activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1434 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Montfort, R.L., Basha, E., Friedrich, K.L., Slingsby, C., and Vierling, E. 2001. Crystal structure and assembly of a eukaryotic small heat shock protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow, G. 1985. Domain structure and evolution in α-crystallins and small heat-shock proteins. FEBS Lett. 181 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyttenbach, A. 2004. Role of heat shock proteins during polyglutamine neurodegeneration: Mechanisms and hypothesis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 23 69–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]