Abstract

β-Amyloid (Aβ) is a major protein component of senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease, and is neurotoxic when aggregated. The size of aggregated Aβ responsible for the observed neurotoxicity and the mechanism of aggregation are still under investigation; however, prevention of Aβ aggregation still holds promise as a means to reduce Aβ neurotoxicity. In research presented here, we show that Hsp20, a novel α-crystallin isolated from the bovine erythrocyte parasite Babesia bovis, was able to prevent aggregation of denatured alcohol dehydrogenase when the two proteins are present at near equimolar levels. We then examined the ability of Hsp20 produced as two different fusion proteins to prevent Aβ amyloid formation as indicated by Congo Red binding; we found that not only was Hsp20 able to dramatically reduce Congo Red binding, but it was able to do so at molar ratios of Hsp20 to Aβ of 1 to 1000. Electron microscopy confirmed that Hsp20 does prevent Aβ fibril formation. Hsp20 was also able to significantly reduce Aβ toxicity to both SH-SY5Y and PC12 neuronal cells at similar molar ratios. At high concentrations of Hsp20, the protein no longer displays its aggregation inhibition and toxicity attenuation properties. Size exclusion chromatography indicated that Hsp20 was active at low concentrations in which dimer was present. Loss of activity at high concentrations was associated with the presence of higher oligomers of Hsp20. This work could contribute to the development of a novel aggregation inhibitor for prevention of Aβ toxicity.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, protein folding, chaperone, amyloid, aggregation

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia in the aging population, is accompanied by the accumulation of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) as amyloid fibrils in senile plaques in the cerebral cortex. It is hypothesized by many that Aβ contributes to the neurodegeneration associated with AD via the toxicity of the peptide in aggregated form.

Investigation of the relationship between aggregated Aβ peptide size, structure, and toxicity is ongoing. In an aggregated state containing fibrils, protofibrils, and low molecular weight intermediates/oligomers, Aβ peptide has proven to be toxic to cultured neuronal cells (Koh et al. 1990; Pike et al. 1993; Lambert et al. 1998; Kayed et al. 2003). Aβ structures reported to be toxic include a nonfibrillar species of ∼17–42 kDa (Lambert et al. 1998; Chromy et al. 2003), protofibrils species with hydrodynamic radii on the order of 9–367 nm (Ward et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2002), and fibril species, with some investigators suggesting that the smaller oligomeric Aβ species are more toxic than fibril and protofibril forms (Dahlgren et al. 2002; Chromy et al. 2003; Kayed et al. 2003). Many believe that one strategy for preventing neurodegeneration associated with AD is the prevention of aggregation of Aβ into its toxic oligomeric or fibril forms.

A number of investigators have developed inhibitors of Aβ aggregation with the aim of preventing Aβ toxicity (Ghanta et al. 1996; Lansbury 1997; Pallitto et al. 1999; Lowe et al. 2001). Some of these inhibitors have been small peptides with sequences that mimic the sequence of Aβ believed to be essential for aggregation and fibril formation (Pallitto et al. 1999). Peptide inhibitors of this class have been able to prevent Aβ toxicity by altering the aggregated structure when added at inhibitor to Aβ molar ratios of near 1:1 (Tjernberg et al. 1996; Pallitto et al. 1999). The use of molecular chaperones including α-crystallins and other small heat shock proteins has also been explored as a means of preventing Aβ aggregation and toxicity.

The superfamily of small heat shock proteins, sHSPs, are a diverse group of proteins involved in prevention of protein misfolding and the onset of programmed cell death (van den Ijssel et al. 1999; Bruey et al. 2000). They typically exist as large multimeric complexes containing four to 40 subunits, with molecular masses of 40 kDa or less per subunit. The sHSPs bind to their substrates with high affinity and prevent protein misfolding in an ATP-independent reaction (Jakob et al. 1993). Generally, the α-crystallins are considered to be sHSPs (Horwitz 1992; MacRae 2000). β-Pleated sheet dominates their secondary structure (Horwitz 2000; van Montfort et al. 2001). A conserved 90-amino-acid sequence, located near the C-terminus, termed the α-crystallin domain, is the hallmark of all α-crystallins.

Small heat shock proteins including α-crystallins have been tested for Aβ aggregation and toxicity prevention activity, mixed results have been reported. Human sHsp27 inhibited Aβ1–42 fibril formation (Kudva et al. 1997). When αB crystallin was examined, it was actually found to increase toxicity and β pleated sheet content of Aβ1–40 although it prevented fibril formation of Aβ in vitro at α-crystallin to Aβ molar ratios of 1:1 or 1:5 (Stege et al. 1999).

In work described here, we use a novel small heat shock protein, Hsp20, isolated from the erythrocyte parasite Babesia bovis to prevent aggregation of Aβ and Aβ toxicity. Using two different Hsp20 constructs, a maltose binding protein fusion (Hsp20-MBP) and a polyhistidine fusion (his-Hsp20), we show that Hsp20 has α-crystallin-like properties, and that it can prevent aggregation of denatured alcohol dehydrogenase. Hsp20 is able to prevent amyloid formation of Aβ as indicated by Congo Red binding at molar ratios of Hsp20 to Aβ of 1:1000. Hsp20 attenuates the toxicity of Aβ in SH-SY5Y and PC12 neuronal cells at analogous molar ratios. Hsp20 appears to be able to prevent Aβ aggregation via a novel mechanism and at much lower concentrations than what has been necessary to prevent aggregation with other inhibitors. Hsp20 may be a useful molecular model for the design of the next generation of Aβ aggregation inhibitors to be used in prevention of Aβ toxicity.

Results

Characterization of Hsp20

Hsp20 is a 177-amino-acid, 20.1-kDa protein isolated from Babesia bovis, a protozoan bovine erythrocyte parasite (Brown et al. 2001). Initial characterization by BLAST search of the NCBI database indicated significant sequence similarity with the α-crystallin family of small heat shock proteins. Hsp20 contains a region near its C-terminus that corresponds to the ∼95 amino acid α-crystallin domain common to members of this protein family. These proteins are thought to be involved in the cellular response to stress. Previous work (A. Rice-Ficht, unpubl.) has revealed that Hsp20 expression is up-regulated in times of thermal, nutritional, and oxidative stress to the organism. Based on the apparent involvement of Hsp20 in the stress response coupled with its homology to the α-crystallins, α-crystallin activity assays were applied to Hsp20. A turbidity assay (Fig. 1 ▶) was used to quantitate the ability of Hsp20-MBP to solubilize target proteins at elevated temperatures. A solution of alcohol dehydrogenase when incubated at 58°C for 60 min exhibited a dramatic increase in light scattering due to aggregation of the enzyme. When Hsp20-MBP was included in the solution at time zero in a molar ratio of 2:1 Hsp20:ADH, a 2.3-fold reduction in light scattering was observed at 60 min. To determine the most effective molar ratio for the reduction of light scattering, a series of experiments was conducted in which different mole ratios of Hsp20 were added to ADH (Fig. 2 ▶). At time infinity (determined by curve fitting software), the greatest reduction in light scattering was seen at a molar ratio of 2:1 (Hsp20 to ADH). Since Hsp20-MBP was prepared as a fusion protein with maltose binding protein, we examined the ability of maltose binding protein (MBP) alone to alter aggregation and turbidity of ADH in the same range of concentrations. MBP had no effect on ADH aggregation, suggesting the aggregation-prevention activity was due to the presence of Hsp20. Having established the α-crystallin activity of Hsp20-MBP based on standard assays, we then proceeded to test the ability of Hsp20-MBP to affect Aβ (1–40) fibril formation.

Figure 1.

Light scattering of ADH, as determined by absorbance at 360 nm, at elevated temperature in the presence and absence of Hsp20-MBP. ADH at a concentration of 1.625 μM is incubated in phosphate buffer alone (open circles) and in the presence of 5.75 μM Hsp20 (closed triangles) at 58°C for 1 h.

Figure 2.

Percent reduction of light scattering at time infinity of ADH when mixed with Hsp20-MBP relative to light scattering of ADH alone. The negative of light scattering seen at 2:1 molar ratio (Hsp20:ADH) indicates that light scattering of the Hsp20:ADH mixture was 80% less than light scattering of ADH alone. The near zero value of change in light scattering at 1:1000 Hsp20:ADH mole ratio indicates that light scattering of the mixture was unchanged from light scattering of ADH seen in Figure 1 ▶. All experiments were performed at 58°C. The concentration of ADH was 1.625 μM in each experiment. Light scattering at time infinity was estimated from absorbance versus time curves for each mixture.

Effect of Hsp20-MBP on Aβ fibril formation prevention

Given that Hsp20-MBP was able to prevent aggregation of denatured ADH, we then examined its ability to prevent aggregation and amyloid fibril formation of Aβ(1–40). We used Congo Red binding as a simple indicator of amyloid formation. In these experiments, 20 μM, 50 μM, and 100μM concentrations of Aβ(1–40) were used to create fibrils. Hsp20-MBP at concentrations from 1 nM to 5 μM were added to Aβ(1–40) solutions prior to aggregation. This corresponds to molar ratios of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ of 1:20,000 to 1:20 or 0.00005 to 0.05. After 24 h of incubation, sufficient time for typical fibril formation, Congo Red was added to samples to assess fibril formation. Representative Congo Red absorbance spectra are seen in Figure 3 ▶. Hsp20-MBP alone did not alter Congo Red absorbance. Pure Aβ(1–40) solutions caused a characteristic shift in absorbance to longer wavelengths and an increase in intensity. Hsp20-MBP, when added to Aβ prior to aggregation, attenuated the shift in absorption and increase in intensity associated with Aβ fibril formation. MBP alone, when added to Aβ at similar concentrations had no effect on fibril formation as assessed by Congo Red binding.

Figure 3.

Representative absorbance spectra of Congo Red with Aβ and Aβ-Hsp20 mixtures. One-hundred-millimolar Aβ(1–40) was used in all cases. Hsp20-MBP was added at the beginning of the 24-h aggregation at room temperature with mixing. (Bold line, Congo Red alone; fine line, Aβ alone; light gray line, 1:100 Hsp20:Aβ; dark gray line,1:1000 Hsp20:Aβ.)

We show in Figure 4A ▶ the effect of Hsp20-MBP on reduction of Aβ fibril formation at different concentrations of Aβ and Hsp20-MBP. At Hsp20-MBP concentrations below 0.1 μM, Aβ fibril formation decreased as a function of Hsp20-MBP concentration. However, Hsp20-MBP became less effective at preventing Aβ fibril formation in the higher concentration range. The concentration of Hsp20-MBP needed for optimal prevention of fibril formation appeared to be a function of Aβ concentration, with the lowest concentration of Aβ exhibiting the optimum in prevention of fibril formation at the lowest Hsp20-MBP concentration. In Figure 4B ▶, we replotted the fibril formation data as a function of molar ratio of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ at the three different Aβ concentrations. It would appear from Figure 4B ▶ that the three curves are now superimposed. The optimum in fibril formation for the three concentrations of Aβ tested occurred at or near the same molar ratio of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ between 0.0005 and 0.001. The molar ratio of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ needed to optimally prevent fibril formation was several orders of magnitude lower than that needed to prevent aggregation of ADH.

Figure 4.

Relative fibril formation as estimated from Congo Red binding. Fibril formation is reported relative to fibril formation seen with pure Aβ solutions. Mean plus or minus standard deviation of at least three independent experiments are reported. (A) Relative fibril formation as a function Hsp20-MBP concentration. (B) Relative fibril formation as a function of the molar ratio of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ. Open circles, 20 μM Aβ; squares, 50μM Aβ; triangles, 100μM Aβ.

Electron micrographs of Aβ fibrils, Hsp20-MBP, and Aβ-Hsp20-MBP mixtures that correspond to conditions used in the Congo Red binding studies are shown in Figure 5 ▶. In the images, 100 μM Aβ and 0.1 μM Hsp20-MBP were used. As seen in Figure 5A ▶, Aβ formed long individual fibrils and groups of long fibrils under the aggregation conditions employed. Hsp20-MBP, at 0.1 μM and room temperature, formed species of ∼13.6 nm in diameter, composed of two subunits, 5.4 nm in width each, with a distance of 2.7 nm between subunits (Fig. 5B ▶). In micrographs of the Aβ-Hsp20-MBP mixture (Fig. 5C ▶), small globular species with a 16.3-nm diameter and variable length were observed. These species could be an Hsp20-Aβ complex, large Hsp20-MBP aggregates, and/or Aβ-protofibrils. Aβ fibrils were noticeably absent from micrographs of Aβ-Hsp20 mixtures.

Figure 5.

Representative electron micrographs of Aβ and Hsp20-MBP after 24 h of aggregation (A) 100μM Aβ, (B) 0.1μM Hsp20-MBP, and (C) 100μM Aβ + 0.1μM Hsp20-MBP.

Ability of Hsp20-MBP to prevent toxicity of Aβ

Aβ is typically toxic to neuron-like cells (SY5Y cells, and PC12 cells etc.) when in aggregated form. In Figure 6 ▶, we show the effect of Hsp20-MBP on Aβ toxicity as measured using the MTT assay for 100 μM Aβ added to SH-SY5Y cells and 2 μM Aβ added to PC12 cells. Hsp20-MBP by itself had no effect on SH-SY5Y or PC12 cell viability. However, Hsp20-MBP, when added to Aβ prior to aggregation, had a profound effect on Aβ toxicity observed in both cell types. MBP, when added to Aβ, did not attenuate Aβ toxicity. The toxicity attenuation behavior observed in Figure 6 ▶ mirrors the trends in fibril formation prevention seen in Figure 4 ▶. The concentration of Hsp20-MBP needed for optimal toxicity prevention appears to scale with Aβ concentration, with less Hsp20-MBP needed to prevent toxicity when less Aβ was present. The molar ratio of Hsp20 to Aβ needed for optimal toxicity attenuation is approximately the same as the molar ratio needed for optimal fibril-formation prevention.

Figure 6.

Relative cell viability of SY5Y cells (triangles) and PC12 cells (circles) treated with 100 μM (triangles) and 2 μM (circles) Aβ as a function of Hsp20-MBP concentration. Viability is measured via the MTT reduction assay. N ≥ 6. Aβ(1–40) was incubated for 24 h in the media prior to addition to the cells. Viability as a function of molar ratio of Hsp20-MBP to Aβ; viability is reported relative to control cells.

Ability of His-Hsp20 to prevent Aβ aggregation and toxicity

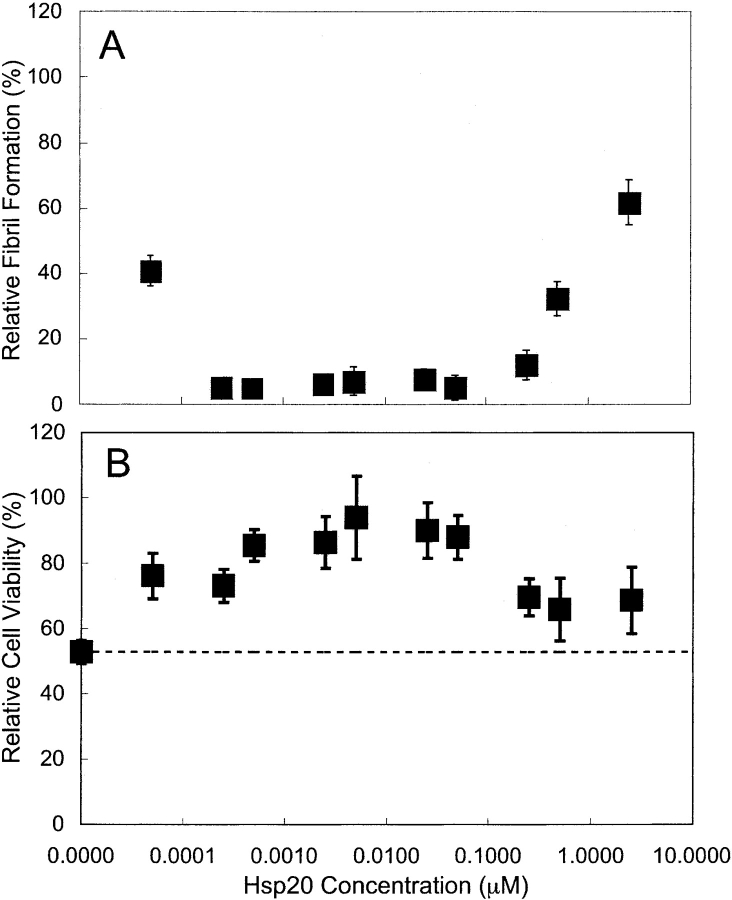

While control experiments demonstrated that MBP alone had no effect on Aβ aggregation and toxicity, it was possible that the MBP fusion contributed to the function of Hsp20. To examine this possibility, we next generated an N-terminal polyhistadine-Hsp20 fusion protein. In experiments parallel to those described above, we examined if the polyhistadine-Hsp20 fusion protein could also prevent Aβ aggregation and toxicity as measured by Congo Red binding and MTT reduction, respectively. As seen in Figure 7 ▶, his-Hsp20 prevents Aβ aggregation and toxicity over a wider range of concentrations and at lower concentrations than the MBP fusion protein. Also, attenuation of toxicity approached 100% with the his-Hsp20 while the Hsp20-MBP attenuated Aβ toxicity to a lesser extent. However, as with the MBP fusion protein, there was a noticeable loss of His-Hsp20 activity at concentrations above 1 μM.

Figure 7.

Relative Aβ fibril formation and SH-SY5Y cell viability as a function of concentration his-Hsp20. (A) Fibril formation is reported relative to fibril formation in pure 50 mM Aβ solutions and determined via Congo Red binding. (B) Cell viability was measured via MTT reduction and reported relative to cells untreated with Aβ or his-Hsp20. Aβ or his-Hsp20 mixtures were mixed, then aggregated with mixing at 37°C for 24 h prior to viability or Congo Red binding measurements.

Size exclusion chromatography of his-Hsp20

To examine the mechanism of loss of activity of his-Hsp20 at higher concentrations we examined size of his-Hsp20 oligomers in solution as a function of concentration. Stock solutions of his-Hsp20 were diluted to 100 μM, 29 μM, and 0.1 μM in PBS shortly before analysis. Chromatograms of his-Hsp20 at the different concentrations can be seen in Figure 8 ▶. At the highest concentration (Fig. 8A ▶), his-Hsp20 elutes as a mixture of a number of oligomers, ranging from an approximate 16-mer, 10-mer, 6-mer, tetramer, dimer, and monomer, with dimer representing about 15% of total protein eluted the column. At intermediate concentrations (Fig. 8B ▶), a mixture of oligomers is still seen, with dimer making up about 42% of the protein eluted from the column. At the lowest concentration, 0.1 μM, a concentration at which his-Hsp20 displays both high aggregation and toxicity prevention activities, only dimer was observed. Analytical ultracentrifugation was used to confirm the presence of high molecular weight oligomers of his-Hsp20 at high concentrations (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Representative size exclusion chromatograms of his-Hsp20 at (A) 100 μM his-Hsp20, (B) 29 μM his-Hsp20, and (C) 0.1 μM his-Hsp20. Separations were performed on a Pharmacia Superose 6 column at room temperature using phosphate buffered saline as an elution buffer.

Inability of Hsp20-MBP to reverse Aβ aggregation

We examined if, once Aβ was aggregated, the addition of Hsp20-MBP could reverse fibril formation. We aggregated Aβ under conditions analogous to those described previously and, after 24 h aggregation, we added Hsp20 at optimal concentrations for fibril formation prevention determined from earlier experiments (100 nM). At all times measured after addition of Hsp20 to aggregated Aβ up to 48 h, there was no loss in fibril content as measured by Congo Red binding and no prevention of Aβ toxicity as measured by the MTT assay in SH-SY5Y cells. Indeed, fibril formation proceeded at the same approximate rate as if no Hsp20 had been added (data not shown).

Discussion

A protein, Hsp20, isolated by Rice-Ficht and coworkers from the bovine erythrocyte parasite B. bovis (Brown et al. 2001) has repeatedly demonstrated α-crystallin activity in vitro. In the results presented here, we demonstrate that Hsp20 both reduces Aβ fibril formation at very low molar ratios, and reduces Aβ toxicity at similar molar ratios. While other small heat shock proteins and α-crystallins have also been examined for their ability to prevent Aβ and other amyloid fibril formation with good success at relatively low molar ratios of α-crystallin to amyloid (Kudva et al. 1997; Hughes et al. 1998; Stege et al. 1999; Hatters et al. 2001), in none of these studies has toxicity inhibition been reported. Indeed, in work reported by Stege and coworkers (1999), α-B-crystallin prevented Aβ fibril formation but enhanced toxicity. Thus, we believe that Hsp20, which has limited sequence homology with other α-crystallins, may act via a unique mechanism to prevent Aβ aggregation and toxicity, and may provide insight on how to design the next generation of Aβ aggregation inhibitors to prevent Aβ toxicity associated with AD.

We show that Hsp20 reduces aggregation of ADH at an optimal mole ratio of 2 Hsp20 to 1 ADH (Figs. 1 ▶, 2 ▶). This is consistent with the observations of van Montfort et al. (2001) that other alpha crystallins are active as dimers. We show that Hsp20-MBP and his-Hsp20 prevent Aβ fibril formation as indicated by the absence of Congo Red binding and of visible fibrils in electron micrographs, at molar ratios near 1:1000 Hsp20 to Aβ or lower (Figs. 3 ▶–5 ▶, 7 ▶). This is in sharp contrast to the near 2:1 molar ratio needed to prevent ADH aggregation. A number of investigators have explored the ability of other small heat shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and α-crystallins to prevent fibril formation in several systems including Aβ (Kudva et al. 1997; Hughes et al. 1998; Stege et al. 1999; Hatters et al. 2001). Most have found that the chaperones or small heat shock proteins can inhibit Aβ aggregation at molar ratios of chaperone to Aβ of 1:10 to 1:100. The low concentrations of Hsp20 and other α-crystallins needed to prevent fibril formation, relative to that needed to prevent ADH aggregation, could be related to specificity of the α-crystallins for β-sheet or fibril-forming proteins. Alternatively, the difference in molar ratios needed to prevent ADH aggregation relative to those needed to prevent Aβ fibril formation could be related to the temperature differences at which the experiments were carried out. The ADH aggregation experiments were carried out at elevated temperature, while the Aβ fibril formation experiments were carried out at room temperature. The quaternary structure of α-crystallins are generally temperature dependent; however, most often, more highly active oligomers (dimers) are formed at higher temperatures (Abgar et al. 2001; van Montfort et al. 2001). Indeed, when we performed fibril formation and toxicity prevention experiments with Hsp20-MBP and Aβ at 37°C instead of room temperature, ∼10 times less Hsp20-MBP was needed to prevent fibril formation (or 1:10,000 Hsp20 to Aβ mole ratio) relative to that needed to maximally prevent fibril formation at room temperature (data not shown).

Another plausible explanation for Hsp20 activity is that Hsp20 interacts with an oligomer of Aβ in a near 2:1 molar ratio; however, the Aβ oligomer may be very dilute in Aβ solutions. In models of Aβ aggregation, investigators postulate that Aβ forms micelles or multimeric nuclei from Aβ monomers or dimers via a high order process (Lomakin et al. 1996; Pallitto and Murphy 2001; Yong et al. 2002). It is from these micelles or nuclei that fibril growth is initiated. Micelles or nuclei would be far less abundant than monomeric Aβ. We propose that binding to or removal of these fibril-initiating species from solution would be sufficient to prevent Aβ fibril formation.

The difference in fibril prevention activity of the two Hsp20 constructs tested, Hsp20-MBP and his-Hsp20, are clearly demonstrated in Figure 7 ▶. We speculate that the almost 100-fold increase in effectiveness of the his-Hsp20 compared to the Hsp20-MBP at preventing fibril formation is due to higher affinity of the his-Hsp20 for Aβ than Hsp20-MBP affinity for Aβ. Differences in Hsp20 structure or stability in the two different constructs may also affect fibril prevention activity of the protein.

As seen in Figures 4 ▶ and 7 ▶, there is an optimum concentration of Hsp20 for Aβ fibril-formation prevention. We suggest several possible explanations for this observation. Oligomerization dynamics of α-crystallins are concentration-dependent (McHaourab et al. 2002). Hsp20 may aggregate to form a less active structure at higher concentrations. High molecular weight oligomers of heat shock proteins, which tend to form at high concentrations, are less active than the low molecular weight oligomers (Liang 2000). Additionally, equilibrium distribution of oligomeric Hsp20 species are likely dependent upon conformers or oligomers of substrate Aβ present in solution. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) data presented in Figure 8 ▶ supports the hypothesis that Hsp20 oligomerization is concentration dependent. At concentrations where his-Hsp20 has high Aβ fibril prevention activity, his-Hsp20 elutes as a dimer from the SEC column, suggesting that the active form of his-Hsp20 is a dimer. At concentrations of his-Hsp20 where the protein displays less fibril prevention activity or no activity, complex mixtures of oligomers were detected via both SEC (Fig. 8 ▶) and analytical ultracentrifugation (data not shown). These data suggest that oligomers larger than the dimer are inactive. Hsp20-MBP becomes inactive in the fibril formation assay at lower concentrations than his-Hsp20, suggesting that the MBP construct contributes to the destabilization of the active dimer. Changes in oligmerization of Hsp20-MBP at low concentrations could not be confirmed because of limits of sensitivity of detection of the FPLC system in the range of concentrations where Hsp20-MBP was active.

Analogous to fibril formation prevention data, Hsp20 attenuates Aβ toxicity at similar molar ratios (Figs. 6 ▶, 7 ▶). These data suggest that the Aβ species which bind Congo Red and have fibril appearance in electron micrographs are toxic, or, more probably, Aβ species which are associated with the formation of Congo Red binding or fibril species are toxic. While nonfibrillar diffusible Aβ species (sometimes referred to as ADDLs), low molecular weight oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils have all been found to be toxic (Pike et al. 1993; Lambert et al. 1998; Kayed et al. 2003; and others), recent evidence suggests that oligomeric Aβ are the toxic (or most toxic) species (Dahlgren et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002; Kayed et al. 2003; for example).

A careful examination of electron micrographs of Aβ-Hsp20 mixtures under optimal fibril formation and toxicity prevention conditions (Fig. 5 ▶) reveals the presence of small globular species. The globular species are not yet well characterized, however, size analysis suggests that the species may be an Hsp20-Aβ complex rather than Aβ protofibrils since the width of these species is atypical for Aβ micelles (5–11 nm), protofibrils (4–8 nm), or fibrils (6–10 nm) (Yong et al. 2002).

A number of different approaches have been explored for prevention of Aβ amyloid fibril formation and toxicity. Pentapeptides such as KLVFF (Pallitto et al. 1999), LPFFD (Soto et al. 1998), GVVIN, and RVVIA (Hetenyi et al. 2002) have been used to disrupt Aβ fibril formation and neurotoxicity. These pentapeptides have the same or similar residues as segments of Aβ essential for fibril formation, bind to Aβ, and alter the structure that Aβ adopts (Soto et al. 1998). Generally, 1:1 molar ratios of peptide inhibitors to Aβ are needed in order to effectively prevent fibril formation (Pallitto et al. 1999). Amphipathic molecules such as hexadecyl-N-methylpiperidinium (HMP) bromide or sulfonated molecules such as Congo Red have also been used to prevent Aβ fibril formation and toxicity. These aggregation and toxicity inhibitors, while effective, appear to act via a different mechanism than Hsp20.

In summary, we believe that we have found, with Hsp20, a novel protein, which reduces both Aβ fibril formation and toxicity at very low molar ratios. These properties make Hsp20 unique relative to other Aβ aggregation inhibitors reported in the literature. Upon further investigation of the mechanism of Hsp20 fibril formation and toxicity prevention, we hope to identify essential interactions between Aβ and Hsp20 necessary for prevention of the formation of toxic Aβ species.

Materials and methods

Materials

Aβ(1–40) was purchased from Biosource International. Cell culture reagents were purchased from GibcoBRL. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise stated.

Hsp20 preparation

Hsp20 was produced in two forms, as an N-terminal fusion protein with maltose binding protein (Hsp20-MBP) and as an N-terminal polyhistidine fusion protein (his-Hsp20). Both proteins were produced in Escherichia coli. The production of the maltose binding protein fusion has been previously described (Brown et al. 2001). The N-terminal polyhistidine fusion protein was made with an intervening Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease site (Carrington et al. 1988) between Hsp20 and a polyhistidine tract. The construct was created through PCR of the Hsp20 coding sequence using a primer containing a 5′, 21-bp extension encoding the TEV protease site. The PCR product was introduced into the pTrcHis2 TOPO protein expression vector (Invitrogen) and transformed into chemically competent TOP10 cells (Invitrogen). His-Hsp20 was prepared by growing cells to OD600 of 0.5 followed by induction with 1 mM IPTG for 5 h, and removal of media. The cells were then lysed in PBS using a French pressure cell and the insoluble his-Hsp20 pellet collected. The pellet containing his-Hsp20 was suspended in Denaturing Binding Buffer (Invitrogen) containing 8 M urea and incubated with Probond resin for 1 h to allow binding of his-Hsp20 to the nickel chromatography resin. The protein was eluted from the resin using 100 mM EDTA, dialyzed overnight into PBS (pH 7.0), 20% glycerol, and frozen at −80°C. Protein purity and molecular weight were confirmed by SDS PAGE. Upon use, Hsp20 was diluted into buffers that did not contain additional EDTA.

Aβ peptide preparation

Stock solutions of 10 mg/mL Aβ(1–40) peptides were dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water. After incubation for 20–30 min at 25°C, the peptide stock solutions were diluted to concentrations of 0.5 mg/mL by addition of sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M NaH2PO4, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4). The peptides were diluted to final concentrations of 20 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM by addition of PBS for Congo Red and electron microscopy (EM) studies. Cell culture medium (below) replaced PBS in toxicity studies. These peptide solutions were rotated at 60 revolutions per minute at 25°C for 24 h to ensure aggregation. In solutions of peptide alone, evidence of fibril formation as measured by Congo Red binding was seen after a lag period of 4–5 h. Congo Red binding increased rapidly after the lag period, then appeared to approach a constant maximum level at between 24 and 48 h.

Cell culture

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (a gift of Dr. Evelyn Tiffany-Castiglioni, College of Veterinary Medicine, Texas A&M University) were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B (fungizone) in a humidified 5% (v/v) CO2/air environment at 37°C. Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) horse serum, 5% (v/v) FBS, 3 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/mL fungizone in a humidified 5% (v/v) CO2/air environment at 37°C. For the toxicity assays, cells were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well in 96-well plates and aggregated peptide solutions were added to the cells 24 h after plating.

Congo Red binding

Congo Red studies were performed to assess the presence of amyloid fibrils in Aβ solution. Congo Red dye was dissolved in PBS to a final concentration of 120 μM. Congo Red solution was added to the peptide solutions at the ratio of 1:9. The peptide solution and control solution were allowed to interact with Congo Red for 30–40 min prior to absorbance measurement with a Model 420 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Spectral Instruments) at 25°C. The fibril formation of the samples was estimated from the absorbance using equation 1:

|

(1) |

where [AβFib] is the concentration of Aβ fibril, 541 At, 403 At, and 403 ACR are the absorbances of the sample and Congo Red at the wavelength of 541 nm and 403 nm, respectively (Klunk et al. 1999). From these data, relative fibril concentrations were calculated as the ratio of sample fibril concentration to pure Aβ fibril concentration.

MTT reduction assay

Cell viability was measured 24 h after peptide addition to cells using the 3, (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction assay. Ten microliters of 12 mM MTT was added to 100 μL of cells plus medium in a 96-well plate. The cells were incubated with MTT for 4 h in a CO2 incubator. Then, 100 μL of a 5:2:3 N, N-dimethylforamide (DMF): sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS): water solution (pH 4.7) was added to dissolve the formed formazan crystals. After 18 h incubation in a humidified CO2 incubator, the results were recorded by using an Emax Microplate reader at 585 nm (Molecular Devices). Percentage cell viability was calculated by comparison between the absorbance of the control cells and that of peptide or peptide:Hsp20 treated cells.

Electron microscopy (EM)

Aβ peptide solution (200 μL), prepared as described above, was mixed, placed on glow discharged grids, and then negatively stained with 1% aqueous ammonium molybdate (pH 7.0). Grids were examined in a Zeiss 10C transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Calibration of magnification was done with a 2,160 lines/mm crossed line grating replica (Electron Microscopy Sciences).

Turbidity assay

ADH turbidity assay

Light Scattering of ADH and Hsp20 was performed as previously described (Horwitz 1992). Briefly, the aggregation of ADH and Hsp20 in solution was measured by the apparent absorption due to scattering at 360 nm in a Gilford Response II spectrophotometer at 58°C. Solutions were mixed at room temperature in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and analyzed immediately. In all experiments 1.625 μM ADH was used. Hsp20 concentrations were varied to obtain different molar ratios of Hsp20 to ADH. Absorbance readings were taken at 1-min intervals for 1 h.

Size exclusion chromatography

The size of his-Hsp20 oligomers as a function of concentration at room temperature was determined using size exclusion chromatography using a Pharmacia FPLC system. Protein samples at different concentrations were loaded on a Superose 6 HR 10/300 column (Pharmacia) and eluted using PBS. Eluted proteins were detected using UV absorbance at either 280 nm or 254 nm. Oligomer sizes were estimated based on the elution volumes of a set of calibration proteins run on the same column under similar conditions. In no cases were chelating agents added to the his-Hsp20 solutions in an attempt to prevent aggregation of the his tagged protein.

Statistical analysis

For each experiment, at least three independent determinations were made. Significance of results was determined via the student t test with p < 0.05 unless otherwise indicated. Data are plotted as the mean plus or minus the standard error of the measurement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and The Welch Foundation to T.G. and by a grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to A.R.-F.

Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.041020705.

References

- Abgar, S., Vanhoust, J., Aerts, T., and Clauwaert, J. 2001. Study of the chaperoning mechanism of bovine lens α-crystallin, a member of the α-small heat shock superfamily. Biophys. J. 80 1986–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.C., Ruef, B.J., Norimine, J., Kegerreis, K.A., Suarez, C.E., Conley, P.G., Stich, R.W., Carson, K.H., and Rice-Ficht, A.C. 2001. A novel 20-kDa protein conserved in Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina stimulates memory CD4+ T lymphocytes responses in B. bovis-immune cattle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 118 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruey, J.M., Ducasse, C., Bonniaud, P., Ravagnan, L., Susin, S.A., Diaz-Latoud, C., Gurbuxani, S., Arrigo, A.P., Kroemer, G., Solary, E., et al. 2000. Hsp27 negatively regulates cell death by interacting with cytochrome c. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, J.C. and Dougherty, W.G. 1988. A viral cleavage site cassette: Identification of amino acid sequences required for tobacco etch virus polyprotein processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85 3391–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy B.A., Nowak R.J., Lambert M.P., Viola K.L., Chang L., Velasco P.T., Jones B.W., Fernandez S.J., Lacor P.N., Horowitz P., Finch C.E., Krafft G.A., and Klein W.L. 2003. Self-assembly of Aβ(1–42) into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry 42 12749–12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, K., Manelli, A., Stine, B., Baker, L., Krafft, G., and LaDu, M.J. 2002. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid β-Peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277 32046–32053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanta, J., Shen, C.L., Kiessling, L.L., and Murphy, R. 1996. A strategy for designing inhibitors of β amyloid toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 271 29525–29528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatters, D.M, Hatters, D.M., Lindner, R.A., Carver, J.A., and Howlett, G.J. 2001. The molecular chaperone, α-crystallin, inhibits amyloid formation by apolipoprotein C-II. J. Biol. Chem. 276 33755–33761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetenyi, C., Kortvelyesi, T., and Penke, B. 2002. Mappling of possible binding sequences of two β sheet breaker peptides on β amyloid peptide of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10 1587–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, J. 1992. α-Crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. PNAS 89 10449–10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2000. The function of α-crystallin in vision. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S., Khorkova, O. Goyal, S. Knaeblein, J., Heroux, J., Reidel, N., and Sahasrabudhe, S. 1998. α2Macroglobulin associates with β-amyloid peptide and prevents fibril formation. PNAS 95 3275–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob, U., Gaestel, M., Engel, K. and Buchner, J. 1993. Small heat shock proteins are molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 268 1517–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed, R. Head, E. Thompson, J., McIntire, T, Milton, S, Cotman, C., and Glabe, C. 2003. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300 486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk, W.E., Jacob, R.F., and Mason, R.P. 1999. Quantifying amyloid β-peptide (Abeta) aggregation using the Congo red-Abeta (CR-abeta) spectro-photometric assay. Anal. Biochem. 266 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh, J.Y., Yang, L.L., and Cotman, C.W. 1990. β-Amyloid protein increases the vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to excitotoxic damage. Brain Res. 533 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudva, Y., Hiddinga, H., Butler, P., Mueske, C., and Eberhardt, N. 1997. Small heat shock protein inhibits in vitro Aβ(1–42) amyloidogenesis. FEBS Lett. 416 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, M.P., Barlow, A.K., Chromy, B.A., Edwards, C., Freed, R., Liosatos, M., Morgan, T., Rozovsky, I., Trommer, B., Viola, K., et al. 1998. Diffusable, nonfibrillar ligands drived from Ab1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. PNAS 95 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbury Jr., P.T. 1997. Inhibition of amyloid formation: A strategy to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.J. 2000. Interaction between β-amyloid and lens αB-crystallin. FEBS Lett. 484 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin, A., Chung, D., Benedek, G., Kirschner, D., and Teplow, D. 1996. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid β-protein fibrils: detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, T. Strzelec, A., Kiessling, L., and Murphy, R. 2001. Structure-function relationships for inhibitors of β amyloid toxicity containing the recognition sequence KLVFF. Biochemistry 40 7882–7889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae, T.H. 2000. Structure and function of small heat shock/α-crystallin proteins: Established concepts and emerging ideas. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57 899–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaourab, H.S., Dodson, E.K., and Koteiche, H.A. 2002. Mechanism of chaperone function in small heat shock proteins. Two-mode binding of the excited states of T4 lysozyme mutants by αA-crystallin. J. Biol. Chem. 277 40557–40566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto, M.M. and Murphy, R.M. 2001. A mathematical model of the kinetics of β-amyloid fibril growth from the denatured state. Biophys. J. 81 1805–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto, M.M., Ghanta, J., Heinzelman, P., Kiessling, L.L., and Murphy R.M. 1999. Recognition sequence design for peptidyl modulators of beta-amyloid aggregation and toxicity. Biochemistry 38 3570–3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike, C.J., Burdick, D., Walencewicz, A.J., Glabe, C.G., and Cotman, C.W. 1993. Neurodegeneration induced by beta-amyloid peptides in vitro: The role of peptide assembly state. J. Neurosci. 13 1676–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto, C., Sigurdsson, E.M., Morelli, L., Kumar, R.A., Castano, E.M.,and Frangione, B. 1998. β-sheet breaker peptides inhibit fibrillogenesis in a rat brain model of amyloidosis: Implications for Alzheimer’s therapy. Nat. Med. 4 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stege, G, Renkawek, K., Overkamp, P. Verschuure, P., van Rijk, A., Reijnen-Aalbers, A., Boelens, W., Bosman, G., and de Jong, W. 1999. The molecular chaperone α-Bcrystallin enhanced amyloid β neurotoxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 262 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjernberg, L.O., Naslund, J., Lindqvist, F., Johansson, J., Karlstrom, A.R., Thyberg, J., Terenius, L., and Nordstedt, C. 1996. Arrest of β-amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 271 8545–8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Ijssel P., Norman, D.G., and Quinlan, R.A. 1999. Molecular chaperones: small heat shock proteins in the limelight. Curr. Biol. 9 R103–R105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Montfort, R.L.M., Basha, E., Friedrich, K.L., Slingsby, C., and Vierling, E. 2001. Crystal structure and assembly of a eukaryotic small heat shock protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.-S., Becerra-Arteaga, A., and Good, T. 2002. Development of a novel diffusion-based method to estimate the size of the aggregated Aβ species responsible for neurotoxicity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, R.V., Jennings, K.H., Jepras, R., Neville, W., Owen, D.E., Hawkins, J., Christie, G., Davis, J.B., George, A., Karran, E.H., et al. 2000. Fractionation and characterization of oligomeric, protofibrillar and fibrillar forms of β-amyloid peptide. Biochem. J. 348 137–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong, W., Lomakin, A., Kirkitadze, M.D., Teplow, D.B., Chen, S.H., and Benedek, G.B. 2002. Structure determination of micelle-like intermediates in amyloid β-protein fibril assembly by using small angle neutron scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]