Abstract

Present in virtually every species, thioredoxins catalyze disulfide/dithiol exchange with various substrate proteins. While the human genome contains a single thioredoxin gene, plant thioredoxins are a complex protein family. A total of 19 different thioredoxin genes in six subfamilies has emerged from analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Some function specifically in mitochondrial and chloroplast redox signaling processes, but target substrates for a group of eight thioredoxin proteins comprising the h subfamily are largely uncharacterized. In the course of a structural genomics effort directed at the recently completed A. thaliana genome, we determined the structure of thioredoxin h1 (At3g51030.1) in the oxidized state. The structure, defined by 1637 NMR-derived distance and torsion angle constraints, displays the conserved thioredoxin fold, consisting of a five-stranded β-sheet flanked by four helices. Redox-dependent chemical shift perturbations mapped primarily to the conserved WCGPC active-site sequence and other nearby residues, but distant regions of the C-terminal helix were also affected by reduction of the active-site disulfide. Comparisons of the oxidized A. thaliana thioredoxin h1 structure with an h-type thioredoxin from poplar in the reduced state revealed structural differences in the C-terminal helix but no major changes in the active site conformation.

Keywords: NMR, structural genomics, cell-free protein production

Thioredoxins are small (~12–14-kDa) proteins that function as protein disulfide oxidoreductases through the reversible oxidation of two cysteine thiols in a structurally conserved active site. Animals and prokaryotes typically possess one or a few genes encoding thioredoxins; however, genome sequencing projects have revealed the plant thioredoxins to be an unexpectedly large family. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the 19 trx genes are grouped by patterns of intron spacing and amino acid sequence similarity into six subfamilies (m, f, h, x, y, and o) that also correspond to differences in subcellular localization. The eight h-type thioredoxins are each thought to target specific protein subsets, thereby enabling selective redox regulation of biochemical processes at every stage of plant development (Brehelin et al. 2000; Buchanan and Balmer 2004).

The structure and redox properties of animal and bacterial thioredoxins have been studied extensively, but none of the Arabidopsis thioredoxins have been structurally characterized. Likewise, until the recent report of the structure of a poplar thioredoxin (Coudevylle et al. 2005) no h-type plant Trx structures had been solved. Despite the wealth of recent work revealing the complexity of the trx gene family, specific functions and molecular targets for most of the plant thioredoxins remain to be identified. Ongoing genetic, proteomic, and functional studies will need to be combined with structural data to fully characterize the network of redox signaling interactions in which the thioredoxins undoubtedly play a central role.

In this report, we describe the first structure of a thioredoxin from Arabidopsis thaliana, At3g51030.1/AtTrx h1, which was selected from the genome of this model plant system as a structural genomics target. We produced isotopically labeled protein using a novel cell-free expression system (Vinarov et al. 2004), and used automated approaches to assign the 1H, 15N, and 13C resonances and determine the structure of the oxidized protein by NMR spectroscopy (Markley et al. 2003). We also measured the redox-state dependence of backbone chemical shifts and mapped those differences to the protein structure. These results provide an initial structural view of the Arabidopsis thioredoxin family that will help elucidate their functional roles in plant redox regulation.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

Samples of the gene product of A. thaliana gene At3g51030.1 (hereafter AtTrx h1) were prepared in [U-13C,15N]-labeled form according to CESG wheat germ cell-free protocols as described (Vinarov et al. 2004). Briefly, the protein was expressed with an N-terminal His6 fusion tag in wheat germ extract supplemented with [U-13C,15N] amino acids (Cambridge Isotope Labs) and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography. The samples used for NMR structure determination contained ~0.4 mM protein (used for triple-resonance spectra) or 0.8 mM protein (NOESY spectra), 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5), and no reducing agent. After data collection for the structure was completed using oxidized protein, the active-site disulfide was reduced by adjusting the pH to 7.5 and adding 2 mM DTT for analysis of redox-sensitive chemical shifts.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR data were acquired at 25°C on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance CryoProbe and processed with NMR Pipe software (Delaglio et al. 1995). The total acquisition time for all NMR spectra was ~390 h, and no protein degradation or unfolding was detected in comparisons of 1D and 2D spectra collected at the start and the end of data collection. Heteronuclear 15N-1H NOE values were determined from an interleaved pair of two-dimensional gradient sensitivity-enhanced correlation spectra of [U-13C,15N] At3g51030.1 acquired with and without a 3-sec proton saturation period (Farrow et al. 1994) and analyzed using NMR View (Johnson 2004). The translational self-diffusion coefficient of At3g51030.1 was measured with a water-sLED pulse scheme (Altieri et al. 1995) using 5-msec gradient pulses (6–45 G/cm) and a diffusion delay of 80 msec. Over 90% of the backbone 1H, 15N, and 13C resonance assignments were obtained in an automated manner using the program Garant (Bartels et al. 1996), with peak lists from 3D HNCO, HNCACO, HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCACB, and CCONH spectra that were generated automatically with SPSCAN. Side-chain assignments were completed manually from 3D HCCONH, HCCH-TOCSY, and 13C(aromatic)-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra analyzed using XEASY (Bartels et al. 1995). Resonance assignments for the reduced At3g51030.1 were obtained by inspection from the assigned spectra of oxidized At3g51030.1 and confirmed using an HNCACB spectrum collected on the reduced protein.

Structure determination

Distance constraints were obtained from 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC and 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra (τmix=80 msec). Backbone φ and Ψ dihedral angle constraints were generated from secondary shifts of the 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, and 15N nuclei shifts using the program TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999). Structures were generated in an automated manner using the CANDID module of the torsion angle dynamics program CYANA (Herrmann et al. 2002), which produced an ensemble with high precision and low residual constraint violations that required minimal manual refinement. The 20 CYANA conformers with the lowest target function were subjected to a molecular dynamics protocol in explicit solvent (Linge et al. 2003) using XPLOR-NIH (Schwieters et al. 2003).

Results and Discussion

Structure of oxidized AtTrx h1

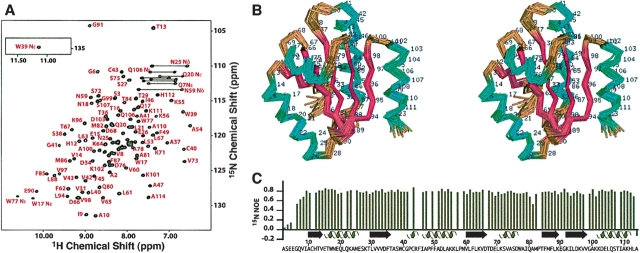

Under the conditions chosen for NMR analysis, the number, dispersion, and line widths of the observed signals in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum (Fig. 1A ▶) and the translational self-diffusion coefficient (Ds=1.5 × 10−6 cm2/sec) were all consistent with a homogeneous, monomeric folded protein. Based on 13Cβ chemical shift values and NOEs between the side chains of Cys 40 and Cys 43, we established that the active-site cysteines were in the oxidized, disulfide-bonded state, consistent with the absence of reducing agents in the sample preparation. A cis peptide linkage conserved throughout the thioredoxin family was confirmed by the presence of a sequential NOE between the 1Hα resonances of Met 82 and Pro 83. The cis-Pro peptide bond and a covalent linkage between the sulfur atoms of Cys 40 and Cys 43 were consequently enforced throughout the structure refinement.

Figure 1.

NMR assignments and 3D structure of At3g51030.1/AtTrx h1. (A) 2D 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of At3g51030.1, with representative assignments indicated by residue number and one-letter amino acid code. (B) Stereo view of the ensemble of 20 NMR structures, with helices in cyan and β-strands in magenta. (C) Heteronuclear 15N-1H NOE values plotted with the amino acid sequence and secondary structure elements indicated.

An automated procedure for iterative NOE assignment (Herrmann et al. 2002) was used in determining the three-dimensional structure of the protein. Molecular dynamics calculations in explicit solvent (Linge et al. 2003) were used in the final refinement. The final conformers were generated from 185 dihedral angle constraints and 1452 unique, NOE-derived distance restraints. Statistics describing the agreement with experimental constraints, coordinate precision, and stereochemical quality are summarized in Table 1. The ensemble of 20 conformers displays the conserved thioredoxin fold (Fig. 2B ▶; Martin 1995), consisting of a five-stranded mixed β-sheet surrounded by four α-helices. Uniformly high (~0.75) 15N–1H NOE values (Fig. 2C ▶) indicate that the AtTrx h1 backbone is relatively rigid, consistent with the precision of the calculated structures and the thermostability that characterizes the thioredoxin family. Atomic coordinates and chemical shift assignments for oxidized AtTrx h1 were deposited in the PDB (accession code 1XFL) and BioMagResBank (entry no. 6318).

Table 1.

Structural statistics for 20 NMR structures

| Constraint summary | ||

| Dihedral angles from TALOS19 | φ | 91 |

| Ψ | 94 | |

| NOE | Long | 372 |

| Medium | 241 | |

| Short | 362 | |

| Intraresidue | 477 | |

| Total | 1452 | |

| Ramachandran from PROCHECK24 | Most favored | 89.25 % |

| Additionally allowed | 10.25 % | |

| Generously allowed | 0.23 % | |

| Disallowed | 0.27 % | |

| Deviation from idealized geometry | ||

| Bond lengths | RMSD (Å) | 0.015 |

| Torsion angle violations | RMSD (°) | 1.1 |

| Constraint violations | ||

| NOE distance | No. > 0.5 Å | 0 ± 0 |

| RMSD (Å) | 0.027 ± 0.001 | |

| Torsion angle violations | No. > 5° | 0.15 ± 0.49 |

| RMSD (°) | 0.66 ± 0.096 | |

| Atomic RMSD to mean structure (residues 6–113) (Å) | Backbone | 0.60 ± 0.11 |

| Heavy atom | 1.00 ± 0.10 | |

| WHATCHECK25 quality indicators | Z-score | 0.08 ± 0.25 |

| RMS Z-score | ||

| Bond lengths | 0.77 ± 0.02 | |

| Bond angles | 0.72 ± 0.02 | |

| Bumps | 0 ± 0.00 | |

Figure 2.

Redox-dependent structural changes in AtTrx h1. (A) HSQC spectra of oxidized (green contours) and reduced (red contours) AtTrx h1, with cross-peaks for residues with significant shift perturbations connected by arrows. (B) Combined 1H/15N shift differences are plotted as a function of AtTrx h1 sequence. (C) Ribbon diagram of AtTrx h1 NMR structure with chemical shift perturbations indicated in green (0.25–1) and magenta (>1). (D) Comparison of structures of AtTrx h1 and poplar Trx h1 (PDB code 1TI3), aligned over all residues using the FATCAT servfer (Ye and Godzik 2004).

Redox-dependent NMR analysis

To assess the degree of structural rearrangement that may accompany changes in the AtTrx h1 oxidation state, we collected a series of spectra of the protein before and after reduction of the active-site disulfide with dithiothreitol (Fig. 2A ▶). Reduction of the disulfide was confirmed by comparing 13Cβ resonances of the active-site cysteines, which shift from 44.9 to 27.0 ppm (Cys40) and from 34.6 to 27.8 ppm (Cys43); these values are similar to those reported for Escherichia coli Trx. Both active-site cysteines and the nearby Asp34 carboxyl group have pKa values above 7, and should remain in the protonated (neutral) charge state at pH 5.5 (Chivers et al. 1997). Redox-dependent spectral changes can therefore be ascribed to conformational changes resulting from the loss of the disulfide linkage.

The greatest 1H/15N chemical shift differences (Fig. 2B ▶) occur in residues surrounding the active-site cysteines (e.g. Ala37–Phe45). Interestingly, Thr84 undergoes a noticeable shift, even though adjacent residues appear unperturbed. However, the adjacent Pro83 forms a conserved cis-peptide bond with residue 82 and contacts the side chain of Cys43. Reduction of the disulfide shifts the Pro83 13Cα downfield and the 13Cβ upfield, both by ~0.5 ppm, suggesting that core packing interactions may vary with the AtTrx h1 redox state. Additional modest shift perturbations cluster in residues connecting strand β5 and helix α4 (Val98, Gly99, Lys101, and Lys102). None of these residues contact the Cys43 (Fig. 2C ▶), but the Pro83 side chain packs against the backbone of Gly99, providing a link to the active site. These residues form part of a highly charged cluster (K101KDE104) positioned at the top of the α4 helix, loosely conserved as a BBAA motif (B=basic; A=acidic) within the h and f subfamilies of the Arabidopsis thioredoxins. Two residues at the C terminus of α4 (Lys111 and His112), over 20 Å away from the active-site disulfide, also display similar shift differences, providing additional evidence for redox-triggered long-range conformational changes.

Comparison with other Trx structures

Numerous thioredoxin structures have been determined, and all display a high degree of structural homology. A comparison of AtTrx h1 with the PDB using the Vector Alignment Search Tool (VAST) showed that eight different Trx structures with sequence identities ranging from 30% to 46% align with Cα r.m.s.d. values of between 1.6 and 2.0 Å, including E. coli (1TRX), Plasmodium falciparum (1SYR), Trypanosomal (1R26), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (1EP7), Drosophila (1XWA), spinach m- and f-type (1FB0 and 1F9M), and human (1ERV). Interestingly, despite sharing 66% sequence identity, the structure of thioredoxin h1 from poplar (Coudevylle et al. 2005) superimposes on AtTrx h1 with a Cα r.m.s.d. of 2.2 Å. Differences between the two structures are localized mainly to the α4 helix (Fig. 2D ▶), where the sequence similarity is relatively low. The deviations may also be due to redox state, since the poplar Trx structure was solved in the reduced form, or from the presence of an alternative active-site sequence. The active-site cysteines are typically located in the highly conserved WCGPC motif, but a few of the plant h-type thioredoxins (e.g., AtTrx h3–5 and poplar Trx h1) contain the sequence WCPPC instead. However, as noted previously, the Gly → Pro substitution causes little or no rearrangement in the conserved Trx active-site geometry, but may create a more rigid structure relative to the WCGPC-containing proteins (Coudevylle et al. 2005).

AtTrx interacting proteins

Functional thioredoxins participate in at least two types of protein–protein interactions. Plant h-type thioredoxins are reduced by NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductases (NTR) and transfer reducing equivalents to target proteins. The structure of the dimeric A. thaliana NTR has been determined (Dai et al. 1996), but the structure of the complex with Trx is unknown. Studies of A. thaliana NTR with different Trx h proteins from barley seed suggested a role for the conserved Lys101, since substitution with isoleucine at this position reduced the binding affinity (Maeda et al. 2003). Conserved hydrophobic residues near the active site that are implicated in the E. coli NTR:Trx interaction (Lennon et al. 2000) are also found in Trxh1 (Trp39, Thr67, Ala81, Gly99, and Ala100); thus it seems likely that plant NTRs will bind a similar surface contiguous with the active site that could include Lys101.

In contrast, target protein recognition by plant thioredoxins is likely to be highly divergent. Hydrophobic loop residues corresponding to Ala81–Pro83 and Val98– Ala100 in AtTrx h1 are thought to participate in substrate binding by bacterial Trx (Eklund et al. 1984; Holmgren 1995), but other residues that have been specifically implicated are not conserved in the h-type thioredoxins. For example, Lys101, present in Trxh1, h2, h7, h8, and chloroplast Trx f, corresponds to a nonpolar aliphatic residue in most eubacterial Trx and chloroplast Trx m (Mora-Garcia et al. 1998) and is a conserved Leu in Trx y (Lemaire et al. 2003). Substitution with lysine at this position (L94K) and adjacent to the active site (E30K) in E. coli Trx was shown to increase binding to chloroplast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase by 10-fold (Mora-Garcia et al. 1998). Yeast complementation studies provide an initial glimpse of how cytosolic targets are partitioned among the set of Arabidopsis h thioredoxins, and suggest that the two active-site motifs, WCGPC and WCPPC, are specificity determinants (Brehelin et al. 2000, 2004). Redox midpoint potentials of AtTrx active-site Gly → Pro or Pro → Gly mutations are essentially unchanged, suggesting that subtle structural changes are responsible for modulating the recognition of target proteins (Brehelin et al. 2004).

Numerous chloroplastic targets have been characterized over the past two decades of investigation into Trx-linked redox regulation of photosynthesis (Buchanan and Balmer 2004). In contrast, only a few targets for the h Trx subfamily have been identified and studied. However, recent proteomics studies have begun cataloging cytosolic proteins that interact with the h-type thioredoxins from A. thaliana (Marchand et al. 2004; Yamazaki et al. 2004).

Cell-to-cell transport of thioredoxin in plants

A particularly intriguing aspect of the cytosolic plant thioredoxins is their potential for long-range transport through the phloem sieve tubes. Over 100 proteins are found in the sap of the phloem translocation system, and one of the most abundant rice phloem proteins, RPP13–1, is an h-type thioredoxin with 61% amino acid sequence identity to AtTrx h1 (Ishiwatari et al. 1995). The rice Trx h protein was also shown to mediate its own transport through plasmodesmata, the intercellular cytoplasmic bridges by which nutrients enter the phloem sieve tubes for transport. Residues of the AtTrx h1 N terminus (M1ASEE5) and the start of the α4 helix (K101KDE104) closely resemble the MAAEE and RKDD motifs that were shown to be essential for plasmodesmal translocation of the rice protein (Ishiwatari et al. 1998). Interestingly, these sequence elements are found only in the thioredoxins of higher plants, and are absent in the bacterial, mammalian, and algal homologs. Among Arabidopsis thioredoxins, the N-terminal sequence is conserved in only the h-type AtTrx 1, 3, 4, and 5, which are the only ones that lack a substantial N-terminal extension. As noted above, the α4 BBAA motif is also restricted to the h Trx subfamily, and strictly conserved only in AtTrx h1 and 2. Thus, depending on the exact sequence requirements, AtTrx h1 may be the only thioredoxin in Arabidopsis that is capable of plasmodesmal translocation, but this potentially unique function has yet to be demonstrated.

In summary, we have determined the first structure of an h-type thioredoxin from Arabidopsis thaliana, AtTrx h1. It adopts the conserved thioredoxin fold and possesses all of the typical functional groups that stabilize and tune the redox properties of the active site. NMR measurements on the reduced and oxidized protein revealed chemical shift differences that are largest in the active site, as well as modest perturbations to more distant residues that are conserved within the Trx h subfamily. Redox-dependent chemical shifts at both ends of the C-terminal α4 helix also correlate with the largest structural differences between AtTrx h1 and the poplar Trx h1 structure. Additional biochemical and structural characterization of these proteins and their functional interactions will be required to understand how this uniquely diverse Trx family provides redox regulation throughout the plant.

Coordinates and restraints have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/) under PDB code 1XFL. All time-domain NMR data and chemical shift assignments have been deposited in BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/) under BMRB accession number 6318.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH Protein Structure Initiative through grant 1 P50 GM64598 (J.L.M., P.I.).

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.051477905.

References

- Altieri, A.S., Hinton, D.P., and Byrd, R.A. 1995. Association of biomolecular systems via pulsed field gradient NMR self-diffusion measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 7566–7567. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, C., Billeter, M., Güntert, P., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. Automated sequence-specific NMR assignments of homologous proteins using the program GARANT. J. Biomol. NMR 7 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehelin, C.,Mouaheb, N., Verdoucq, L., Lancelin, J.M., and Meyer, Y. 2000. Characterization of determinants for the specificity of Arabidopsis thioredoxins h in yeast complementation. J. Biol. Chem. 275 31641–31647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehelin, C., Laloi, C., Setterdahl, A.T., Knaff, D.B., and Meyer, Y. 2004. Cytosolic, mitochondrial thioredoxins and thioredoxin reductases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Photosynthesis Res. 79 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, B.B. and Balmer, Y. 2004. Redox regulation: A broadening horizon. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chivers, P.T., Prehoda, K.E., Volkman, B.F., Kim, B.M., Markley, J.L., and Raines, R.T. 1997. Microscopic pKa values of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 36 14985–14991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, G., Delaglio, F., and Bax, A. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudevylle, N., Thureau, A., Hemmerlin, C., Gelhaye, E., Jacquot, J.P., and Cung, M.T. 2005. Solution structure of a natural CPPC active site variant, the reduced form of thioredoxin h1 from poplar. Biochemistry 44 2001–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, S., Saarinen, M., Ramaswamy, S., Meyer, Y., Jacquot, J.P., and Eklund, H. 1996. Crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana NADPH dependent thioredoxin reductase at 2.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 264 1044–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, H., Cambillau, C., Sjoberg, B.M., Holmgren, A., Jornvall, H., Hoog, J.O., and Branden, C.I. 1984. Conformational and functional similarities between glutaredoxin and thioredoxins. EMBO J. 3 1443–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Muhandiram, R., Singer, A.U., Pascal, S.M., Kay, C.M., Gish, G., Shoelson, S.E., Pawson, T., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay, L.E. 1994. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry 33 5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, T., Güntert, P., and Wüthrich, K. 2002. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 319 209–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, A. 1995. Thioredoxin structure and mechanism: Conformational changes on oxidation of the active-site sulfhydryls to a disulfide. Structure 3 239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari, Y., Honda, C., Kawashima, I., Nakamura, S., Hirano, H., Mori, S., Fujiwara, T., Hayashi, H., and Chino, M. 1995. Thioredoxin h is one of the major proteins in rice phloem sap. Planta 195 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari, Y., Fujiwara, T., McFarland, K.C., Nemoto, K., Hayashi, H., Chino, M., and Lucas, W.J. 1998. Rice phloem thioredoxin h has the capacity to mediate its own cell-to-cell transport through plasmodesmata. Planta 205 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.A. 2004. Using NMR View to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 278 313–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, S.D., Collin, V., Keryer, E., Quesada, A., and Miginiac-Maslow, M. 2003. Characterization of thioredoxin y, a new type of thioredoxin identified in the genome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Lett. 543 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, B.W., Williams Jr., C.H., and Ludwig, M.L. 2000. Twists in catalysis: Alternating conformations of Escherichia coli thioredoxin reductase. Science 289 1190–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linge, J.P., Williams, M.A., Spronk, C.A., Bonvin, A.M., and Nilges, M. 2003. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins 50 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, K., Finnie, C., Østergaard, O., and Svensson, B. 2003. Identification, cloning and characterization of two thioredoxin h isoforms, HvTrxh1 and HvTrxh2, from the barley seed proteome. Eur. J. BioChem. 270 2633–2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, C., Le Marechal, P., Meyer, Y., Miginiac-Maslow, M., Issakidis-Bourguet, E., and Decottignies, P. 2004. New targets of Arabidopsis thioredoxins revealed by proteomic analysis. Proteomics 4 2696–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markley, J.L., Ulrich, E.L., Westler, W.M., and Volkman, B.F. 2003. Macromolecular structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. Methods Biochem. Anal. 44 89–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.L. 1995. Thioredoxin—A fold for all reasons. Structure 3 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Garcia, S., Rodriguez-Suarez, R., and Wolosiuk, R.A. 1998. Role of electrostatic interactions on the affinity of thioredoxin for target proteins. Recognition of chloroplast fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase by mutant Escherichia coli thioredoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 273 16273–16280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters, C.D., Kuszewski, J.J., Tjandra, N., and Clore, G.M. 2003. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinarov, D., Lytle, B., Peterson, F., Tyler, E., Volkman, B., and Markley, J.L. 2004. Cell-free protein production and labeling protocol for NMR-based structural proteomics. Nat. Methods 1 149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, D., Motohashi, K., Kasama, T., Hara, Y., and Hisabori, T. 2004. Target proteins of the cytosolic thioredoxins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y. and Godzik, A. 2004. FATCAT: A web server for flexible structure comparison and structure similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W582–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]