Abstract

A central aspect of pathogenesis in the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or prion diseases is the conversion of normal protease-sensitive prion protein (PrP-sen) to the abnormal protease-resistant form, PrP-res. Here we identify porphyrins and phthalocyanines as inhibitors of PrP-res accumulation. The most potent of these tetrapyrroles had IC50 values of 0.5–1 μM in scrapie-infected mouse neuroblastoma (ScNB) cell cultures. Inhibition was observed without effects on protein biosynthesis in general or PrP-sen biosynthesis in particular. Tetrapyrroles also inhibited PrP-res formation in a cell-free reaction composed predominantly of hamster PrP-res and PrP-sen. Inhibitors were found among phthalocyanines, deuteroporphyrins IX, and meso-substituted porphines; examples included compounds containing anionic, neutral protic, and cationic peripheral substituents and various metals. We conclude that certain tetrapyrroles specifically inhibit the conversion of PrP-sen to PrP-res without apparent cytotoxic effects. The inhibition observed in the cell-free conversion reaction suggests that the mechanism involved direct interactions of the tetrapyrrole with PrP-res and/or PrP-sen. These findings introduce a new class of inhibitors of PrP-res formation that represents a potential source of therapeutic agents for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies.

The bovine spongiform encephalopathy epidemic and the appearance of the new variant of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in humans has heightened the urgency to develop therapies for the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE) or prion diseases. TSE pathogenesis appears to result from the accumulation in the central nervous system of the abnormal protease-resistant form of prion protein (PrP-res), which is derived from its normal protease-sensitive isoform, PrP-sen (for review, see ref. 1). The PrP-sen-to-PrP-res conversion involves changes in conformation and/or monomer aggregation without apparent modifications of amino acid residues.

One approach to TSE therapy is to inhibit PrP-res formation in the infected host. Sulfated glycans and the sulfonated amyloid stain Congo red are known inhibitors of PrP-res formation and scrapie agent replication in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma (ScNB) cells (2–4). These polyanions are also protective against scrapie in rodents if administered near the time of infection but, unfortunately, have no therapeutic benefit after the infection has reached the central nervous system (5–8). Their therapeutic ineffectiveness postinfection may be a result of an inability to cross the blood–brain barrier to the brain where most of the PrP-res accumulates and TSE pathogenesis occurs. This problem and/or inherent toxicity also limit the utility of other classes of potential drugs, the polyene antibiotics (9) and anthracycline (10).

Porphyrins and phthalocyanines (Pcs) are tetrapyrrole compounds that possess characteristics that make them of interest as potential inhibitors. These tetrapyrroles bear some structural resemblance to Congo red in that they all contain hydrophobic aromatic rings and can be synthesized with sulfonate groups. Tetrapyrroles can bind strongly and selectively to proteins and affect changes in protein conformation (11–18), potentially critical properties of an effective inhibitor. Tetrapyrroles are available with wide variations in structure, low toxicities in medical applications (19–22), and the apparent ability to cross the blood–brain barrier (23–26).

In the present study, we identified tetrapyrroles that inhibit the formation of PrP-res in ScNB cells and in a cell-free system. Included were deuteroporphyrins IX (DPs) that are analogs of the natural hemes A, B, C, and S (13), meso-substituted porphines, and Pcs. Surprisingly, the structures of some effective inhibitors were inconsistent with the structural features thought to be important in Congo red and other known inhibitors of PrP-res formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tetrapyrrole Compounds.

The compounds used were obtained from either Porphyrin Products (Logan, UT) or Midcentury (Posen, IL) and used as received.

Immunoblot Assay for PrP-res Accumulation in ScNB Cell Cultures.

The immunoblot assay for PrP-res accumulation was performed as described previously (3). In brief, after the treatments of the ScNB cells as described in Results, the cells were lysed with detergent. The lysates were cleared of debris with a low-speed centrifugation and treated with proteinase K (PK) to remove PrP-sen. The PrP-res was pelleted by ultracentrifugation, solubilized in SDS/PAGE sample buffer, and run on 14% acrylamide precast Novex gels. Proteins were electroblotted onto Immobilon membranes (Millipore) and PrP was detected by using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum (R30) raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 89–103 of the mouse PrP amino acid sequence and a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The blots were developed by using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham). Relative PrP-res band intensities were estimated visually by comparing autoradiographic exposure times giving equivalent band intensities.

Metabolic Labeling and Immunoprecipitation of PrP-sen in ScNB Cells.

The ScNB cells (25-cm2 flasks) were pretreated with PcTS-Fe3+ as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The [35S]methionine labeling of the cells and the immunoprecipitation of 35S-PrP-sen were performed as described previously (3) except that a 1-h pulse and no chase was used for the labeling. PcTS-Fe3+ was maintained at 10 μM in the labeling media of all but the control cells.

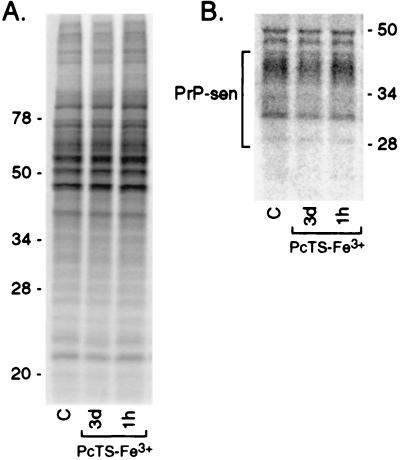

Figure 5.

Phosphor autoradiographic images of 35S metabolic labeling of total proteins (A) and PrP-sen (B) in ScNB cells after pretreatments with 10 μM PcTS-Fe3+. Cultures were seeded and grown to confluence as done in experiments such as those presented in Fig. 2 A and B. PcTS-Fe3+ was added to the culture medium either 3 days or 1 h before labeling of the cells at confluence with [35S]methionine. PcTS-Fe3+ also was maintained at the same concentration in the labeling medium. In A, 5-μl aliquots of 1 ml cell lysates were run directly on the SDS/PAGE gel and the remainder of each lysate was used for the immunoprecipitation of the 35S-PrP-sen samples shown in B.

Cell-Free Conversion Reactions.

PrP-res was purified from the brains of hamsters infected with 263K strain as described previously (27). Preparation of 35S-labeled hamster PrP-sen was carried out as described (28). The PrP-sen used here was the recombinant PrP-sen that lacks a glycophosphatidylinositol anchor because of the introduction of a stop codon at hamster PrP codon 231 (29). Conversions in the presence of GdnHCl were performed as described (28). In brief, PrP-res was incubated in 2.5 M GdnHCl for 1 hr at 37°C. Then the GdnHCl-treated PrP-res was mixed with 35S-labeled PrP-sen (20,000 cpm) in the presence of 1 M GdnHCl/1.25% N-lauryl sarcosine/5 mM cetyl pyridinium chloride/50 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0. For GdnHCl-free conversions [to be detailed elsewhere (M.H. and B.C., unpublished results)], PrP-res was diluted to 50 ng/μl with water and sonicated briefly. Then 100 ng of PrP-res was mixed with 35S-labeled PrP-sen (20,000 cpm) in a total volume of 20 μl, which also contained 200 mM KCl/5 mM MgCl2/0.625% N-lauryl sarcosine/50 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0. Conversion reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 2 days. Nine-tenths of reaction mixture was treated with 20 μg/ml of PK (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0/150 mM NaCl, in 100 μl) for 1 h at 37°C. Digestion by PK was stopped by adding Pefabloc (Boehringer Mannheim) to 2 mM. Thyroglobulin (20 μg) was added as a carrier. The remaining one-tenth of the reaction mixture was analyzed without PK treatment. Methanol precipitates of the proteins were subjected to SDS/PAGE by using 14% acrylamide precast gels (Novex). Radioactive proteins were visualized and quantified by using a Storm PhosphorImager instrument (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

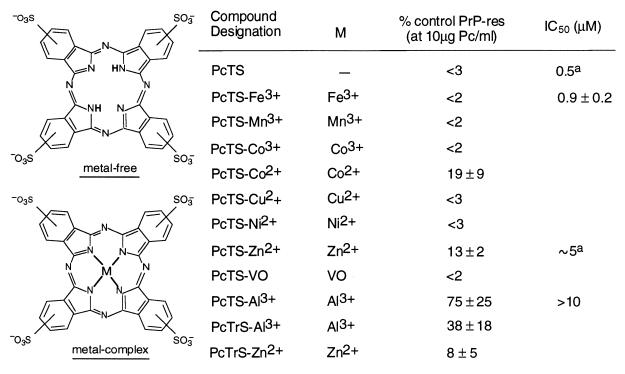

Inhibition of PrP-res Formation by Phthalocyanine (Pc) Sulfonates in ScNB Cells.

Pc sulfonates (Fig. 1) were added to the medium of cells seeded at 5% confluent density and the cultures were allowed to grow to confluence over 3–4 days. The cells then were harvested and analyzed for PrP-res content by immunoblotting. Each Pc sulfonate reduced the level of PrP-res detected at a concentration of 10 μg/ml (≈10 μM) (Fig. 2A). Metal-free, Fe3+, Mn3+, Co3+, Cu2+, Ni2+, and VO compounds were better inhibitors than the Co2+, Zn2+, or Al3+ complexes. Further testing of selected Pc sulfonates at lower concentrations allowed the estimation of the indicated IC50 values with the lowest being the metal-free and PcTS-Fe3+ with IC50 values of <1 μM (Figs. 1 and 2B).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of PrP-res formation in ScNB cells by phthalocyanine (Pc) sulfonates. ScNB cells were cultured for 4 days in the presence of Pcs as described in the text and analyzed for the accumulation of PrP-res by immunoblot (e.g., see Fig. 2). PrP-res band intensities are presented as mean percentage band intensity (±SD) relative to that from untreated control ScNB cells. All Pcs were tested at 10 μM and a few at lower concentrations to estimate the concentration giving 50% inhibition of PrP-res formation relative to control (IC50). PcTS and PcTrS designate compounds with four and three sulfonic acid groups, respectively, per molecule with only one on each peripheral, six-membered ring; variation in ring location results in a mixture of isomers. A superscript “a” indicates that a >80% drop in the 35S-PrP-res formation was observed between 10-fold dilutions of the inhibitor; we report the IC50 as the concentration halfway between the 10-fold dilutions tested, but the actual value could be ±50% of that value.

Figure 2.

Immunoblots of inhibition of PrP-res accumulation in ScNB cultures by PcTS compounds. (A) Effects of PcTS compounds at 10 μM in the culture medium over 4 days. Control is without inhibitor. (B) Concentration dependence of effects of PcTS-Fe3+. “C” designates control. (C) Effect of treatment of ScNB cell lysates with 10 μM PcTS-Fe3+ for 1hr before PK treatment and extraction for the detection of PrP-res by immunoblot. For all of the immunoblots, the primary antibody R30 was used to identify PrP-res in the PK-digested cell extracts.

To control for the possibility that these effects were a result of artifactual interference with the detection of PrP-res rather than an inhibition of PrP-res accumulation in the cells, one of the most effective inhibitors, PcTS-Fe3+, was added at 10 μM (≈10-fold higher than the IC50) to cell lysates before the addition of PK and further processing for the detection of PrP-res. No effect on the PrP-res immunoblot band intensity was observed in comparison with untreated control cell lysates (Fig. 2C), indicating that the PcTS-Fe3+ did not interfere with PrP-res detection.

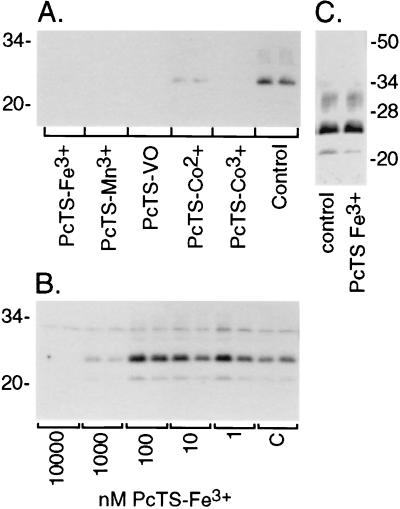

Inhibition of PrP-res Formation by Deuteroporphyrins (DP) in ScNB Cells.

DP(SO3−)2 and DP(SO3−)2Fe3+ appear about equally effective in reducing PrP-res formation at concentrations of 10 μg/ml (≈12 μM) (Fig. 3). Converting the propionate groups to uncharged methyl esters as in DP(SO3−)2Me2 resulted in less inhibition. Inhibitory potency was retained by molecules containing glycols in place of the sulfonates with the Fe3+ complex of DP(glycol)2 being a better inhibitor than the metal-free compound.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of PrP-res formation in ScNB cells by sulfonate- and glycol-substituted deuteroporphyrins (DP). Analysis of effects of DPs on PrP-res accumulation was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods. A superscript “a” indicates that no difference in PrP-res immunoblot signal intensity could be discerned visually between replicates; however, with the autoradiographic methodology used, it was difficult to discriminate differences of ±5%.

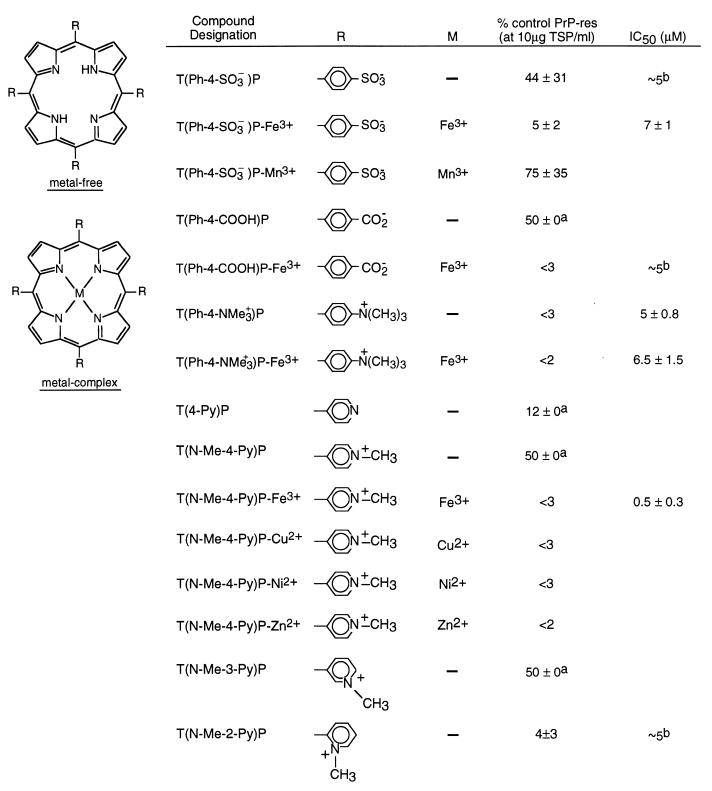

Inhibition of PrP-res Formation by Porphines with Meso Substituents in ScNB Cells.

Among the metal-free tetraphenyl porphines (TPhPs; Fig. 4), the presence of positively charged groups of T(Ph-4-NMe3+)P resulted in a more effective inhibitor than either of the negatively charged carboxylate and sulfonate groups of T(Ph-4-COOH)P and T(Ph-4-SO3−)P, respectively. Insertion of Fe3+ into P(Ph-4-COOH)P increased the inhibition significantly, but an increase was not evident with insertion of either Fe3+ or Mn3+ into T(Ph-4-SO3−)P. The metal-free and Fe3+ complex of T(Ph-4-NMe3+) had comparable IC50 values.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of PrP-res formation in ScNB cells by meso-tetrasubstituted porphines (TSP). Analysis of effects of TSPs on PrP-res accumulation was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 and Materials and Methods. A superscript “a” indicates that no difference in PrP-res immunoblot signal intensity could be discerned visually between replicates; however, with the autoradiographic methodology used, it was difficult to discriminate differences of ≈±5%. A superscript “b” indicates that a >80% drop in the 35S-PrP-res formation was observed between 10-fold dilutions of the inhibitor; we report the IC50 as the concentration halfway between the 10-fold dilutions tested, but the actual value could be ≈±50% of that value.

The tetra-pyridyl porphines (TPyPs; Fig. 4) studied included positively charged N-methyl pyridines and T(4-Py)P. The latter unmethylated compound contains basic pyridine nitrogens that can become positively charged on protonation. At 10 μg/ml (≈10 μM), T(4-Py)P was a somewhat more effective inhibitor than either T(N-Me-4-Py)P or T(N-Me-3-Py)P but less effective than T(N-Me-2-Py)P. Conversion of T(N-Me-4-Py)P to a metal complex with Fe3+, Cu2+, Ni2+, or Zn2+ resulted in a more effective inhibitor.

Lack of Effect of PcTS-Fe3+ on Biosynthesis of PrP-sen and Other Proteins.

To investigate the specificity of tetrapyrrole inhibition of PrP-res formation, we tested one of the most potent inhibitors, PcTS-Fe3+, for effects on the metabolic labeling of PrP-sen and other cellular proteins. Confluent cultures were incubated with [35S]methionine after 3-day or 1-h pretreatments with a fully inhibitory concentration of the tetrapyrrole (10 μM) in the growth medium. As shown in Fig. 5, little difference in the 35S-PrP-sen band intensities or the overall profile of 35S-labeled proteins in the cells were observed. Phosphor audioradiographic quantitation of the PrP-sen bands in four experiments indicated that the 3-day and 1-h pretreated cells had 110 ± 30% and 113 ± 21% (mean ± SEM) of 35S-PrP-sen of untreated control cells, respectively. Moreover, none of the compounds tested in this study affected the rate of growth of the cells to confluence. Thus, the inhibition of PrP-res formation by PcTS-Fe3+ was not a result of effects on cell division, protein biosynthesis in general or the biosynthesis of PrP-sen in particular.

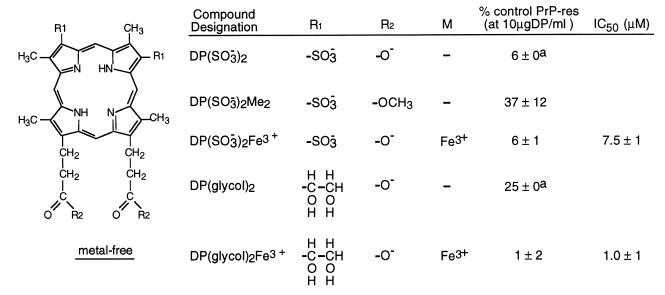

Inhibition of PrP-res Formation in a Cell-Free System.

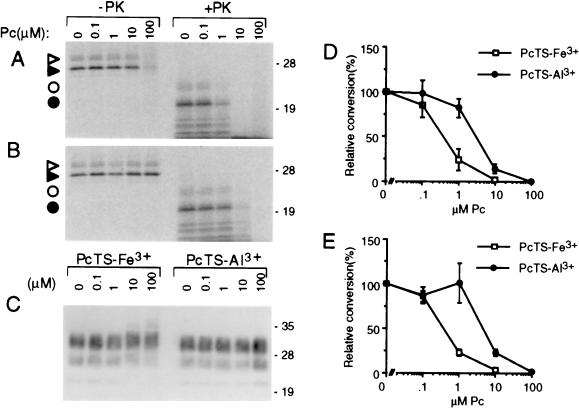

The effects of tetrapyrroles on PrP-res formation was examined in a highly specific, cell-free conversion reaction (28, 30–33). PrP-res isolated from scrapie-infected hamster brain tissue was used to induce the conversion of immunoprecipitated hamster 35S-PrP-sen to 35S-PrP-res. Under two sets of reaction conditions, PcTS-Fe3+ and PcTrS-Al3+ inhibited 35S-PrP-res formation; in each case, the PcTS-Fe3+ had an IC50 (0.4 μM) that was 8-fold lower than that of PcTrS-Al3+ (Fig. 6A, B, D, and E). However, there was no apparent reduction in the PK-resistance and immunoblot detection of the input PrP-res by either compound (Fig. 6C). Additional tests with 10 μg/ml tetrapyrrole under the conditions of Fig. 6D indicated that metal-free PcTS, DP(glycol)2Fe3+, and the metal-free DP(glycol)2 reduced conversion to 0 ± 0%, 3 ± 1%, and 71 ± 16% of control (mean ± SD), respectively. Meso-tetrasubstituted porphines with positively charged substituents were not significantly inhibitory [T(Ph-4NMe3+)P, T(Ph-4-NMe3+)P-Fe3+, T(N-Me-4-Py)P-Fe3+, and T(N-Me-2-Py)P] or were weakly inhibitory [T(N-Me-4-Py)P (66 ± 18% of control)]. Thus, with the exception of the tetrapyrroles with positively charged substituents, a variety of tetrapyrroles that inhibited PrP-res formation in the ScNB cells also inhibited the cell-free system reaction.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of cell-free conversion of PrP-sen to PrP-res by PcTS-Fe3+ (A, D, and E) and PcTrS-Al3+ (B, D, and E) under GdnHCl-free (A, B, and D) or GdnHCl-containing conditions (E). 35S-PrP-sen was incubated with unlabeled PrP-res for 2 days in the presence of the designated concentration of phthalocyanine. One-tenth of the reaction was analyzed by SDS/PAGE without PK digestion; the remainder was digested with PK. (A and B) Phosphor autoradiographic images of 35S-PrP species; open and solid triangles, monoglycosylated and unglycosylated 35S-PrP, respectively, without PK treatment; open and solid circles, monoglycosylated and unglycosylated 35S-PrP-res, respectively, after PK digestion. (C) Immunoblot analysis of the total PrP-res in the PK-digested reaction products using mAb 3F4 [which has an epitope within the normally PK-resistant portion of PrP-res (50)] as described (51). Molecular mass markers are designated in kDa along the right side of A–C. The loss of 35S-PrP in the 100 μM PcTS-Fe3+ lane (-PK) appeared to be due to SDS-insoluble aggregation because higher-molecular-mass 35S-PrP species were visible near the top of the lane (not shown). Because this apparent aggregation was not observed with lower, but highly inhibitory, concentrations of PcTS-Fe3+ (e.g., 1 μM) or with PcTrS-Al3+ or several other inhibitory tetrapyrroles described in the text, we conclude that it was not related to inhibition. (D and E) Graphs of the quantitated 35S-PrP-res products (bands marked with circles in A and B) using GdnHCl-free or GdnHCl-containing conditions, respectively. The data points show the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

The present results show that tetrapyrroles inhibit PrP-res formation in both mouse ScNB cells and the hamster PrP cell-free conversion system. The ScNB cell experiments indicated that this inhibition occurred without apparent cytotoxicity or effects on the rate of PrP-sen biosynthesis. Compared with the prototypic inhibitor Congo red (34), the PcTS-Fe3+ is about 10-fold more potent as an inhibitor in the cell-free conversion reaction (Fig. 6). On the other hand, PcTS-Fe3+ is about 100-fold less potent than Congo red as an inhibitor in the ScNB cell system (Figs. 1 and 2; ref. 2). The basis for the discrepancy in the relative potencies of these inhibitors in these two experimental systems is not known, but may be a result of differences in the PrP molecules involved (mouse vs. hamster) or differences in the extent to which these compounds engage in nonproductive binding to unrelated plasma or cellular proteins in the ScNB system. Both plasma proteins, such as albumin, and cytosolic proteins are known to bind some tetrapyrroles avidly (20, 35–37), which would reduce the tetrapyrrole molecules available for binding to PrP-sen and PrP-res. Furthermore, the self-association of some tetrapyrroles may also reduce the effective tetrapyrrole concentration significantly (38–42).

Potential Mechanism of Inhibition.

Because of the complexity of the ScNB cell culture system, many possible mechanisms of inhibition by tetrapyrroles in this system can be envisioned, ranging from direct effects on PrP-sen↔PrP-res interactions to indirect effects on the biology of the cells. However, since several of these compounds also inhibit the cell-free conversion reaction, which is composed predominantly of PrP species, it is likely that the inhibition by the tetrapyrroles is due to their direct interactions with PrP molecules. The binding of tetrapyrroles to either form of PrP might sterically hinder PrP-res↔PrP-sen interactions or affect the conformations of the molecules in ways that interfere with the conversion reaction. Nonetheless, since the PrP-res preparations presumably are not completely pure, it remains possible that tetrapyrrole interactions with other molecules might play a role in inhibition.

Effect of Structure on Inhibitor Effectiveness.

Since Congo red and most of the other known polyanionic inhibitors of PrP-res formation are sulfonated or sulfated, we anticipated that the sulfonated porphyrins and phthalocyanines might be the best inhibitors. Surprisingly, however, the sulfonates or other anionic groups were not required for inhibition by the porphyrins (Figs. 3 and 4). Indeed, porphyrins with neutral glycol, or even cationic, substituents were effective inhibitors. This aspect of the porphyrins stands in contrast to the polysulfated glycans, which are ineffective when the sulfates are removed or substituted with cationic groups (3).

Previous studies of a variety of tetrapyrrole systems provide a firm basis for predicting the important types of bonding interactions that contribute to both tetrapyrrole↔protein binding and tetrapyrrole self-associations. These are electrostatic interactions of groups on the periphery of the core ring, protic interactions at the central nitrogens if metal-free, axial ligand binding at metal in metal complexes, and π-bonding of the core aromatic ring and any peripheral aromatic rings (38, 39, 41, 43). The large planar core aromatic ring system is likely to be an important feature because it is common to all the tetrapyrrole inhibitors, whereas the peripheral substituents and metals ions (or lack thereof) can vary widely. The identification of the most effective inhibitor and therapeutic agent among tetrapyrrole structures will require the optimization of the combination of core structures and substituents. Important therapeutic parameters likely will include not only the specificity and affinity of PrP binding of these compounds, but also the pharmacokinetics, side effects, toxicity, and delivery to the brain. Many of the tetrapyrrole inhibitors found here are known to be well tolerated in animals, e.g., PcTS-Al3+, PcTrS-Al3+, T(N-Me-4-Py)P-Fe3+, T(Ph-4-SO3−)P, and T(Ph-4-SO3−)P-Fe3+ (19, 21, 44–48). An ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier is expected to be helpful although an inhibitor could be useful prophylactically by preventing PrP-res formation outside the central nervous system. Data on the penetration of the blood–brain barrier by tetrapyrroles are limited. One inhibitor studied here, PcTS-Al3+, and several DP analogs appear to enter the brain (23–26, 48). The intrinsic lipophilicity of tetrapyrroles favors the development of effective modalities for their delivery to the brain.

Tetrapyrroles, TSEs, and Other Amyloidoses.

The mechanism of conversion of PrP-sen to PrP-res appears to resemble the pathogenic processes of amyloid formation associated with a variety of other diseases including Alzheimer’s disease and Type 2 diabetes (1). Thus, it is possible that these tetrapyrroles might serve as inhibitors not only of PrP-res formation, but also of other types of amyloid formation. A recent report showed that another porphyrin, hemin, can inhibit Alzheimer’s β peptide polymerization and cytotoxicity (49). This observation and the present study showing that a broad spectrum of porphyrins and phthalocyanines inhibit PrP-res formation make tetrapyrroles attractive candidates for more extensive study. Fortunately, in the case of TSE diseases, excellent animal models are available for testing their potential therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bob Evans and Gary Hettrick for graphics assistance and Drs. Bruce Chesebro, Joëlle Chabry, Kim Hasenkrug, and Suzette Priola for critical reading of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Pc

phthalocyanine

- PcTS

phthalocyanine tetrasulfonate

- PcTrS

phthalocyanine trisulfonate

- DP

deuteroporphyrin

- PrP-sen

protease-sensitive prion protein

- PrP-res

protease-resistant prion protein

- ScNB

scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells

- TSE

transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

- PK

proteinase K

- GdnHCl

guanidine HCl

References

- 1. Caughey B, Chesebro B. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:56–62. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(96)10054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caughey B, Race R E. J Neurochem. 1992;59:768–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caughey B, Raymond G J. J Virol. 1993;67:643–650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.643-650.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caughey B, Ernst D, Race R E. J Virol. 1993;67:6270–6272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6270-6272.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehlers B, Diringer H. J Gen Virol. 1984;65:1325–1330. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-8-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farquhar C F, Dickinson A G. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:463–473. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-3-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimberlin R H, Walker C A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:409–413. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingrosso L, Ladogana A, Pocchiari M. J Virol. 1995;69:506–508. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.506-508.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demaimay R, Adjou K T, Beringue V, Demart S, Lasmezas C I, Deslys J-P, Seman M, Dormont D. J Virol. 1997;71:9685–9689. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9685-9689.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tagliavini F, McArthur R A, Canciani B, Giaccone G, Porro M, Bugiani M, Lievens P M-J, Bugiani O, Peri E, Dall’Ara P, et al. Science. 1998;276:1119–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslow E, Beychok S, Hardman K D, Gurd F R N. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslow E, Koehler R. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:2266–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caughey W S, Smythe G A, O’Keeffe D H, Maskasky J E, Smith M L. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7602–7622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ignarro L J. Adv Pharmacol (San Diego) 1994;26:35–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neya S, Kaku T, Funasaki N, Shiro Y, Iisuka T, Imai K, Hori H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13118–13123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargrove M S, Olson J S. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11310–11318. doi: 10.1021/bi9603736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storch E M, Daggett V. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11596–11604. doi: 10.1021/bi960598g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter C L, Lloyd E, Eltis L D, Rafferty S P, Lee H, Smith M, Mauk A G. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1010–1017. doi: 10.1021/bi961385u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sternberg E D, Dolphin D, Bruckner C. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4151–4202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sassa S. Curr Med Chem. 1996;3:273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paquette B, van Lier J E. In: Photodynamic Therapy. Henderson B W, Dougherty T J, editors. New York: Dekker; 1992. pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vander Jagt D L, Caughey W S, Campos N M, Hunsaker L A, Zanner M A. In: Malaria and the Red Cell. Eaton J W, Meshnick S R, Brewer G T, editors. New York: Liss; 1989. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stylli S S, Hill J S, Sawyer W H, Kaye A H. J Clin Neurosci. 1995;2:146–151. doi: 10.1016/0967-5868(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drummond G S, Kappas A. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:971–976. doi: 10.1172/JCI112398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bing O, Grundemar L, Ny L, Moeller C, Heilig M. NeuroReport. 1995;6:1369–1372. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199507100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mark J A, Maines M. Pediatr Res. 1992;32:324–329. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199209000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caughey B W, Dong A, Bhat K S, Ernst D, Hayes S F, Caughey W S. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7672–7680. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raymond G J, Hope J, Kocisko D A, Priola S A, Raymond L D, Bossers A, Ironside J, Will R G, Chen S G, Petersen R B, et al. Nature (London) 1997;388:285–288. doi: 10.1038/40876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Caughey B, Nishio J, Ernst D, Race R. In: Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies–Impact on Animal and Human Health. Brown F, editor. Basel: Karger; 1993. pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kocisko D A, Come J H, Priola S A, Chesebro B, Raymond G J, Lansbury P T, Caughey B. Nature (London) 1994;370:471–474. doi: 10.1038/370471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kocisko D A, Priola S A, Raymond G J, Chesebro B, Lansbury P T, Jr, Caughey B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3923–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bessen R A, Kocisko D A, Raymond G J, Nandan S, Lansbury P T, Jr, Caughey B. Nature (London) 1995;375:698–700. doi: 10.1038/375698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bossers A, Belt P B G M, Raymond G J, Caughey B, de Vries R, Smits M A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4931–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demaimay, R., Harper, J., Gordon, H., Weaver, D., Chesebro, B. & Caughey, B. (1998) J. Neurochem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Morgan W T, Smith A, Koskelo P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;624:271–285. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rotenberg M, Margalit R. Biochem J. 1985;229:197–203. doi: 10.1042/bj2290197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taminaga T T, Yushmanov V E, Borissevitch I E, Imasato H, Tabak M. J Inorg Biochem. 1997;65:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(96)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caughey W S, Eberspaecher H, Fuchsman W H, McCoy S, Alben J O. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1969;153:722–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb11784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuhrhop J H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1976;15:648–659. doi: 10.1002/anie.197606481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipskier J F, Tran-Thi T H. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:722–731. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endisch C, Fuhrhop J-H, Buschmann J, Luger P, Siggel U. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6671–6680. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akins D L, Zhu H, Guo C. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:5420–5425. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer H, Orth H. Die Chemie des Pyrrols. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschafts M. B. H.; 1937. pp. 612–618. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng Q, Moan J. Brit J Cancer. 1995;72:565–574. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkelman J. Cancer Res. 1962;22:589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oberley L W, Leuthauser S W C, Pasternak R F, Oberley T D, Schutt L, Sorenson J R J. Agents Actions. 1984;15:535–538. doi: 10.1007/BF01966769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salvemini D, Wang Z, Stern M K, Currie M G, Misko T P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2659–2663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barbanti P, Fabbrini G, Salvatore M, Petraroli R, Cardone F, Maras B, Equestre M, Macchi G, Lenzi G L, Pocchiari M. Neurology. 1996;47:734–741. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howlett D, Cutler P, Heales S, Camilleri P. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:249–251. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolton D C, Seligman S J, Bablanian G, Windsor D, Scala L J, Kim K S, Chen C M J, Kascsak R J, Bendheim P E. J Virol. 1991;65:3667–3675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3667-3675.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kocisko D A, Lansbury P T, Jr, Caughey B. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13434–13442. doi: 10.1021/bi9610562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]