Abstract

The HIV-1 Gag polyprotein contains a segment called p2, located between the capsid (CA) and nucleocapsid (NC) domains, that is essential for ordered virus assembly and infectivity. We subcloned, overexpressed, and purified a 156-residue polypeptide that contains the C-terminal capsid subdomain (CACTD) through the NC domain of Gag (CACTD-p2-NC, Gag residues 276–431) for NMR relaxation and sedimentation equilibrium (SE) studies. The CACTD and NC domains are folded as expected, but residues of the p2 segment, and the adjoining thirteen C-terminal residues of CACTD and thirteen N-terminal residues of NC, are flexible. Backbone NMR chemical shifts of these 40 residues deviate slightly from random coil values and indicate a small propensity toward an α-helical conformation. The presence of a transient coil-to-helix equilibrium may explain the unusual and necessarily slow proteolysis rate of the CA-p2 junction. CACTD-p2-NC forms dimers and self-associates with an equilibrium constant (Kd = 1.78 ± 0.5 μM) similar to that observed for the intact capsid protein (Kd = 2.94 ± 0.8 μM), suggesting that Gag self-association is not significantly influence by the P2 domain.

Keywords: NMR, protein structure and dynamics, HIV-1, p2

The genome of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) encodes an ~55-kDa polyprotein, called Gag, that is itself sufficient for assembly of virus-like particles (Gheysen et al. 1989; Wills and Craven 1991). Several thousand copies of Gag self-associate at lipid rafts on the plasma membrane and bud to form an immature virion. Subsequent to budding, Gag is proteolytically cleaved by the viral protease into the following mature proteins and peptide fragments (listed from N terminus to C terminus): matrix (MA), capsid (CA), p2, nucleocapsid (NC), p1, and p6 (Fig. 1A ▶). Cleavage leads to a dramatic morphological change, termed maturation (Vogt 1996), in which the mature CA proteins assemble into the conical core particle that encapsidates two copies of the viral genome, the NC proteins coat the viral genome, and the MA proteins remain associated with the viral envelope (Coffin et al. 1997).

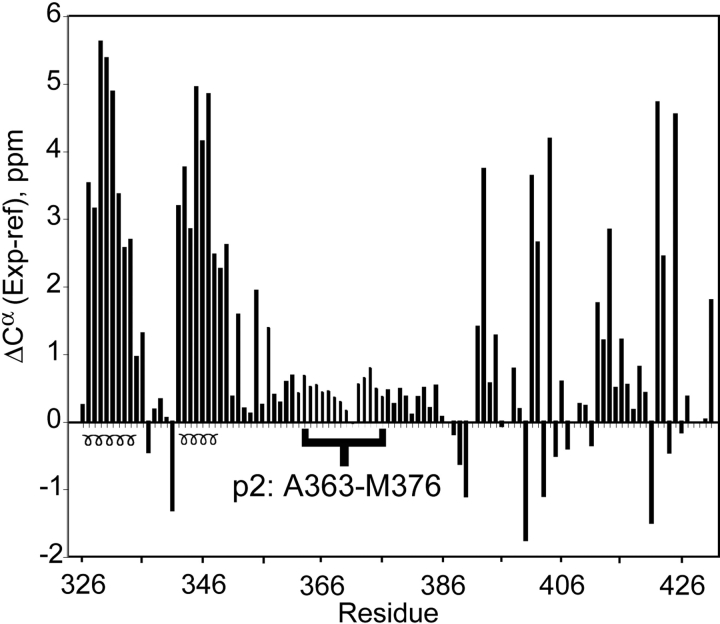

Figure 1.

(A) Cartoon showing the domain structure of the intact HIV-1 Gag polyprotein, along with the CACTD-p2-NC (red, brown, and yellow, respectively) construct utilized in our studies. (B) Representative 1H-15N HSQC spectrum obtained for CACTD-p2-NC at ~1.4 mM concentration. Relatively broad lines correspond to residues of the CACTD domain. (C) Representative strips from the HNCA spectrum showing sequential connectivities for residues of p2 (A363 and A365 are in the same plane).

Although the structures and functions of the mature, functional MA, CA, and NC proteins have been well characterized (Turner and Summers 1999), little is known about the structure and dynamics of the intact Gag polyprotein. Recent NMR studies of an N-terminal Gag fragment that includes the MA domain and the N-terminal domain of CA (MA-CANTD) indicate that a conformational change in the CANTD occurs upon proteolysis of the MA-CA junction (Tang et al. 2002), consistent with an earlier proposal (Gitti et al. 1996). However, structural information for the C-terminal portion of Gag, including the p2, p1, or p6 segments, is currently unavailable. Recent in vivo and in vitro studies indicate that the p2 domain is essential for proper assembly and infectivity (Pettit et al. 1994; Krausslich et al. 1995; Accola et al. 1998). Deletion of p2 severely reduces ordered assembly and infectivity, resulting in crescent-like electron density at the membrane in host cells, and aberrant ‘bent’ core structures in released viral particles (Pettit et al. 1994; Krausslich et al. 1995; Accola et al. 1998). Gag constructs lacking the matrix, p1, and p6 domains, but including p2 are able to assemble into spherical, tubular, and conical particles in vitro, whereas constructs lacking the p2 domain are only able to form conical and tubular particles, resembling mature particles (Gross et al. 2000). Mutation of proteolysis sites at the capsid-p2 and p2-NC junction that abolish cleavage at each site prevent both proper ribo-nuclear protein core and capsid core condensation and lead to the production of particles with severely impaired infectivity (Pettit et al. 1994; Wiegers et al. 1998). In addition, mutation of a glutamic acid residue at the center of p2 to the helix-breakers glycine and proline severely impair viral assembly and replication (Accola et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2002).

Recent computational studies suggest that residues at the capsid-p2 junction should prefer an α-helical conformation (Accola et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2002). However, in the crystal structure of a polypeptide that contains the HIV-1 CACTD and p2, the CACTD is folded, as expected, but no electron density was observed for residues of p2 or the CACTD-p2 junction, indicating that these residues are disordered or undergoing large amplitude motions (Worthylake et al. 1999). Although it is possible that p2 is fully disordered in the crystals, it is equally possible that p2 adopts an independently folded substructure (such as an α-helix) that is itself disordered relative to the CACTD. Similar results were observed for the crystal structure of the intact HIV-1 capsid protein, in which electron density was observed for the N-terminal domain (CANTD), but not for the independently folded C-terminal domain (Momany et al. 1996). Proper folding of p2 could also depend on the presence of the NC domain of Gag. In an attempt to better understand the behavior of p2 in the context of the Gag precursor polyprotein, we subcloned, overexpressed, and purified a 156-residue polypeptide with sequence spanning the C-terminal dimerization domain of capsid through the nucleocapsid domain (CACTD-p2-NC, residues 276–431; Fig. 1A ▶), for NMR-based structural and sedimentation equilibrium (SE) analyses.

Results and Discussion

Sample preparation

Purification of the CACTD-p2-NC construct (prepared by subcloning from the pNL4-3 plasmid; see Materials and Methods) was complicated by the sensitivity of the protein to both proteolysis and oxidation. In order to prevent proteolysis, all buffers were supplemented with an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem, set V) after 0.22-μm filter sterilization and autoclaving. Buffers were supplemented with 3 mM methionine, 3 mM DTT, and 3 mM TCEP after degassing and helium sparging to prevent oxidation. Protein purification was performed at 4°C, and all preps were completed in less than 24 h. Protein yields were approximately 20 mg/L and 15 mg/L of [U-15N] and [U-13C15N]-CACTD-p2-NC, respectively. CACTD-p2-NC mass was confirmed by mass spectroscopy, giving masses of 17,655.8 ± 0.8 Da (17,656 Da calculated) and 18,385.9 ± 0.3 Da (18,385 Da calculated) for [U-15N] and [U-13C15N]-CACTD-p2-NC, respectively.

NMR signal assignment and secondary structure

A representative 1H-15N HSQC spectrum obtained for CACTD-p2-NC is shown in Figure 1B ▶. Although the quality of the spectrum is generally good, a subset of signals exhibits broad linewidths and relatively poor resolution, and this subset is similar in appearance to 1H-15N HSQC data obtained for the isolated CACTD domain (data not shown). This broadening is due to the presence of a weak monomer-dimer equilibrium (Kd of 10 ± 3 μM [Rosé et al. 1992]) and a heterogeneous dimer interface (Gamble et al. 1997). HNCA and HN(CO)CA experiments were utilized to assign a majority of the backbone atoms CACTD-p2-NC. Although rapid T2 relaxation resulting from exchange between monomer and dimer species, as well as exchange between multiple dimer conformations, hindered our efforts to assign residues near the dimer interface of the CACTD domain, 100% of the residues linking the folded portions of CACTD and NC (including all of p2) were readily assigned. Representative spectra showing sequential connectivities for residues K358–N371 (which include the CACTD-p2 junction) are shown in Figure 1C ▶.

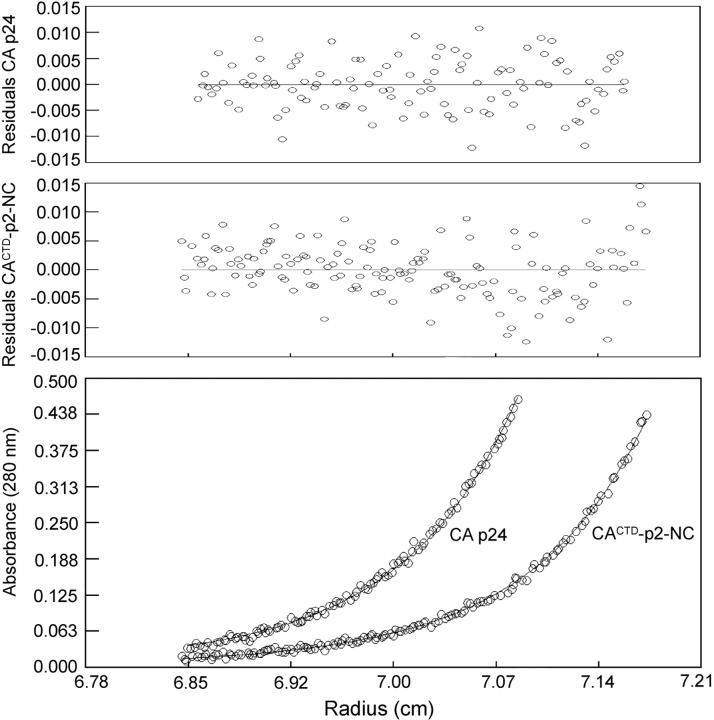

Chemical shift deviations from random coil values for assigned 13Cα atoms are plotted in Figure 2 ▶. Consecutive positive deviations indicate the presence of α-helical secondary structure (Wishart et al. 1991). The helical boundaries identified from the 13Cα (Fig. 2 ▶) and 1HN (data not shown) chemical shift indices are consistent with those observed in the crystal structure of the isolated CACTD (Worthylake et al. 1999), as expected. The isolated CACTD is a globular four-helix protein that forms a weak, disordered dimer promoted mainly by the intermolecular packing of helix 3 (Worthylake et al. 1999), and the isolated NC protein consists of two zinc knuckle domains connected by a flexible linker and flanked by flexible N- and C-terminal tails (Summers et al. 1992). Our NMR data are consistent with these structures. The CSI values for the zinc knuckles of NC do not exhibit regular patterns commonly observed for folded proteins, because these domains lack substantial α-helical or β-sheet structural elements. Most important, small positive chemical shift deviations are observed for residues G351–R386, which includes the p2 segment (Fig. 2 ▶). An internal chemical shift reference (DSS) was used to ensure accuracy in referencing chemical shifts relative to established random-coil values. Although the chemical shift indices are not as large as those observed for the well defined α-helices, they exhibit uniform, positive deviations relative to random coil shifts and are not scattered randomly about zero, as is typically observed in random coil structures.1H-1H NOE data were also obtained for CACTD-p2-NC using 3D 15N-edited and 4D 13C,15N-edited NOESY experiments. The NOE cross-peak patterns and intensities observed for assigned residues of the CACTD and NC domains are consistent with previously reported X-ray (Gamble et al. 1997; Worthylake et al. 1999) and NMR (Summers et al. 1992; De Guzman et al. 1998; Amarasinghe et al. 2000) structures, respectively. Significantly, residues G351–V389, which include the p2 segment, exhibit both strong dNN(i,i+1) and dαN(i,i+1) NOEs and no long-range NOEs. These results are typical of unfolded polypeptides (Wüthrich 1986), and support conclusions from the CSI analysis that residues G351–V389 exist predominantly in a dynamic, random coil conformation.

Figure 2.

Plot of 13Cα chemical shift indices for p2 (in brackets) and adjacent residues of CACTD-p2-NC. Consecutive positive deviations from random coil 13Cα chemical shift values indicate α-helical secondary structure.

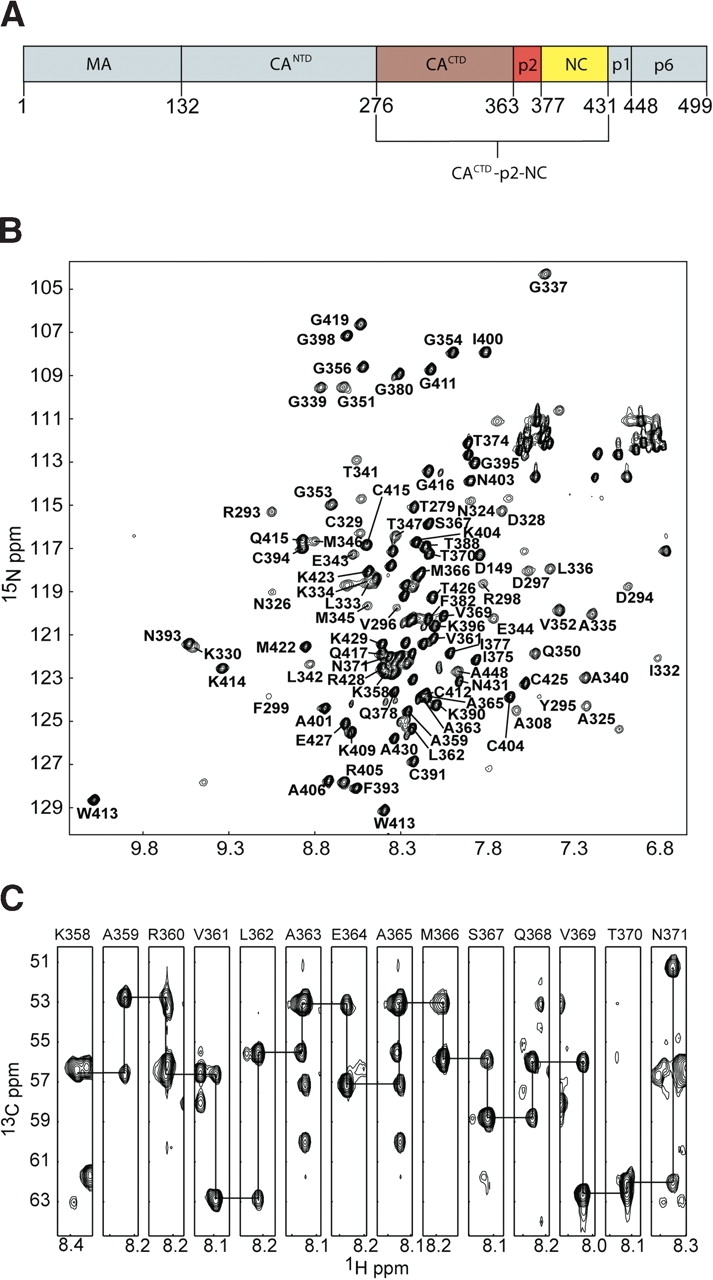

Backbone dynamics

To gain insight into the dynamical properties of p2, 15N T1 and T2 relaxation, and 15N{1H} heteronuclear Overhauser effect (XNOE) data were obtained (Fig. 3 ▶). The XNOE data provide information regarding high-frequency (psec-nsec) backbone motions and are therefore particularly useful for identifying regions of the protein with high internal mobility. The positive XNOE values observed for assigned residues of the folded portions of the CACTD and NC domains (~0.6) are consistent with values expected for folded protein domains (Lee et al. 1998). In contrast, XNOE values for residues A363–M376 are clustered near zero, indicating that p2 and the adjoining residues of the CACTD and NC domains are highly flexible.

Figure 3.

15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE (A) and 15N NMR R1 (=1/T1) (B) and R2 (=1/T2) (C) relaxation and data obtained for CACTD-p2-NC. Only data for well-resolved peaks are shown. Residues corresponding to the p2 linker are colored red; those corresponding to the zinc knuckles are gold. (B) Residues within helices in the CACTD are orange (Helix 1), cyan (Helix 3), and magenta (Helix 4).

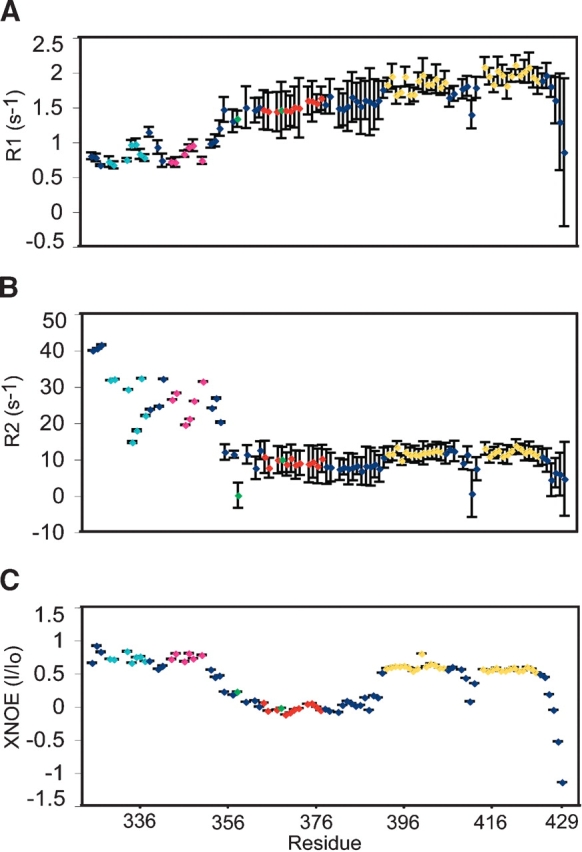

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments

The oligomerization properties of the CACTD-p2-NC protein were examined by SE to determine whether the p2 influences the associative properties of Gag. The SE data obtained for CACTD-p2-NC are consistent with a monomer-dimer equilibrium, with a dissociation equilibrium constant (Kd) of 1.78 ± 0.5 μM (Fig. 4 ▶). This value is in reasonable agreement with results previously obtained for the isolated CACTD (Kd = 10 ± 3μM) and for the intact, full-length CA protein (Kd = 18 ± 1 μM; Gamble et al. 1997; Yoo et al. 1997). We also examined associative properties of intact CA by SE under conditions identical to those employed for CACTD-p2-NC, and observed a monomer-dimer equilibrium with a dissociation constant of 2.94 ± 0.8 μM. Thus the oligomerization properties of CACTD-p2-NC are essentially identical to those observed for the intact CA protein, indicating that p2 does not significantly affect Gag self-association.

Figure 4.

Sedimentation profiles for CACTD-p2-NC and CA p24 (10μM, 20,000 rpm). For both constructs, best fits were obtained for a monomer-dimer equilibrium, affording equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) of 1.78 ± 0.5 μM for CACTD-p2-NC and 2.94 ± 0.8 μM for CA p24.

Biological implications

The assembly of HIV-1 particles is driven primarily by intermolecular Gag–Gag interactions, and the p2 segment appears to play an important role in both virus assembly and maturation (Krausslich et al. 1995; Accola et al. 1998). Mutations that inhibit cleavage of the CA-p2 junction inhibit virus production and lead to the accumulation of Gag in the cytosol (Liang et al. 2002), and the Leu362-Ala363 proteolytic cleavage site is located exactly in the center of a predicted 14-residue α-helix (Accola et al. 1998; Liang et al. 2002, 2003). The NMR relaxation and NOE data indicate that residues G351–V389 of CACTD-p2-NC are flexible, which explains the lack of observed electron density for the p2 residues in the CACTD-p2 crystal structure (Worthylake et al. 1999). However, NMR chemical shift indices indicate that these residues do not adopt a fully random coil conformation. The small positive deviations in the 13Cα chemical shift indices of residues K358–V369 suggest the presence of an α-helical conformation that is in equilibrium with a random coil conformation. CSI values have been shown to correlate with changes in CD spectra of α-helix forming peptides upon addition of TFE, reflecting the percentage of helix formation (Reily et al. 1992). Assuming CSI values of ~3.0 for a full populated α-helix and 0 for a random coil, the average value of 0.476 observed for residues K358–V369 suggests the presence of only a minor helical population. The fact that only a single set of NMR signals are observed for these residues indicates that this equilibrium occurs rapidly on the NMR chemical shift timescale (sub-millisecond), consistent with the 15N relaxation and XNOE results. In addition, the SE experiments indicate that CACTD-p2-NC forms dimers with affinity that is essentially identical to that of the intact capsid protein. This indicates that the transiently formed helix does not promote self-association via, for example, formation of an intermolecular coiled-coil. In view of these findings, it is not clear how the p2 domain facilitates HIV-1 assembly and morphogenesis. One possibility is that p2 might form a stable helix and make intermolecular contacts in the context of the intact, native Gag polyprotein. In this regard, the native HIV-1 Gag polyprotein is posttranslationally myristoylated, and recent NMR and SE studies indicate that myristoylation induces trimerization of both the myristoylated matrix protein (myr-MA) and myr-MA-CA (Tang et al. 2004). It is thus likely that the intermolecular capsid interface is different in the context of a trimeric Gag structure, which could potentially promote the formation of a p2 coiled-coil structure. In addition, previous studies have shown that the N terminus of NC exists in a random coil conformation in the absence of RNA, but forms a helix when the protein binds to RNA stem loop recognition elements (De Guzman et al. 1998; Amarasinghe et al. 2000). It is thus possible that the helical structure could propagate to p2 when the intact Gag binds to RNA. Unfortunately, we have thus far been unable to obtain NMR data for CACTD-p2-NC:RNA complexes of suitable quality to directly address this possibility. Of course, p2 might remain flexible under all conditions, which would presumably be necessary in order for the protease to access the CA-p2 cleavage site during viral maturation.

Finally, a transient helix could play a role in regulating the rate of proteolysis of the CA-p2 cleavage site. In general, the presence of bulky aromatic residues at positions directly N-terminal to the cleavage site facilitates cleavage, whereas bulky aromatic residues directly C-terminal to the cleavage site inhibits cleavage (Pettit et al. 2002). The p2-NC site, which is rapidly cleaved, and the CA-p2 cleavage site do not contain aromatic residues at either the N-terminal or C-terminal positions, suggesting that cleavage rates are regulated by a different mechanism. Interestingly, when the p2 domain was deleted, or the p2-NC cleavage site removed, cleavage at the C terminus of CA increased by 20-fold (Pettit et al. 1994). This suggests that there is a structural component to the relative proteolysis rate at the CA-p2 junction. The presence of a transient helix might inhibit processing, as the helical structures would have to be unwound when bound to the protease.

In summary, our findings indicate that the p2 segment of CACTD-p2-NC does not adopt a stable secondary structure, but instead exists as a dynamic equilibrium of predominantly random coil and, to a smaller extent, helical states. The presence of a dynamic coil-helix equilibrium provides an explanation for the reduced proteolysis rate of the CA-p2 junction, which is important for ordered assembly of the capsid core particle during viral maturation. The p2 domain does not significantly affect the oligomerization properties of the CA or the isolated CACTD domain. Although our findings do not support suggestions that p2 promotes Gag assembly by forming an intramolecular coiled-coil, they do not rule out the possibility that such interactions might occur in the context of the intact, myristoylated, and possibly RNA-associated Gag polyprotein.

Materials and methods

Protein preparation

DNA encoding CACTD-p2-NC was amplified using PCR from the pNL4-3 plasmid (Adachi et al. 1986) encoding the HIV-1 genome. This insert was digested and ligated into the pET-11a vector to obtain the clone CACTD-p2-NC, which was used to transform E. coli Rosetta BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells. Cells were grown in M9 minimal media supplemented with 13C glucose as the sole carbon source and/or 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source to produce [U-13C15N]-CACTD-p2-NC and [U-15N]- CACTD-p2-NC. Cells were grown to an O.D.600 of 0.5–0.6 at 37°C, and then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Upon induction, the incubation temperature was decreased to 30°C, and cells were allowed to grow for 10–12 h before harvesting at an O.D.600 of 1.3–1.6. Cell lysis was performed in two steps. First, Bug Buster reagent (Novagen) in buffer A, consisting of 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 3 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and protease inhibitor cocktail set V (Calbiochem) (pH 7.0) was added to frozen cell pellets at 4°C. All buffers were filter sterilized, autoclaved, degassed, and helium sparged before using. After 45 min, this mixture was subjected to French press lysis. Precipitation of nucleic acids was accomplished by 0.4% polyethylene imine addition on ice while stirring for 40 min. Cell debris and precipitated nucleic acids were removed by centrifugation at 4°C and 37,000g.

Purification was similar to that of HIV-1 NC (De Guzman et al. 1998), still using a combination of anion (SP) and cation (CM) exchange chromatography, where the anion exchange column was removed after protein loading and protein was eluted from the cation exchange column using buffer B (identical to buffer A, except for 1 M NaCl). The CACTD-p2-NC purification scheme involved, however, higher resolution gel filtration (Superdex 75, Amersham), with 500 mM NaCl in buffer A and a 0.1 mL/min flow rate. Fractions containing pure protein after gel filtration were pooled, concentrated, and passed through a 1-mL benzamidine column to remove proteases. The protein was then exchanged into acetate buffer, 25 mM (CD3COO−), 3 mM DTT, 3 mM TCEP, 25 mM NaCl, by membrane ultrafiltration (Centricon) and concentrated to ~600 μL. NMR samples were 5% D2O/95% H2O and ~1.4 mM in concentration.

NMR data collection

All NMR spectra were collected at 30°C with a Bruker AVANCE 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a broadband 5-mm probe-head and shielded Z-axis-gradient coil. 2D 15N HSQC (15N-labeled sample), 3D HNCA (13C15N-labeled sample), and 3D HN(CO)CA (13C15N-labeled sample) data sets were collected to facilitate assignment of backbone 15N, 1HN, 1Hα, and 13Cαresonances (Grzesiek and Bax 1992). 3D 15N-edited NOESY (Kay et al. 1989) and 4D 15N/13C edited NOESY experiments (Kay et al. 1990; τm = 100 ms) were collected to make intraresidue side-chain assignments and identify NOEs between backbone 1HN amide protons and side-chain 1HC protons.

Longitudinal (R1), transversal (R2), and 15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE (XNOE) data for the backbone 15N nuclei of CACTD-p2-NC protein were collected in interleave mode as 1024*(HN) × 96*(N) data sets with 16 scans per point, 4-sec interscan delay for T1 and T2, and 2 × 1024*(HN) × 128*(N) points, 64 scans, and an inter-scan delay of 4 sec for the XNOE experiment. The XNOE experiment consisted of a reference experiment with a recovery delay of 8 sec, and the second experiment (NOE experiment) applied proton saturation during the last 3 sec of the 8-sec recovery delay. 15N T1 (=1/R1) and T2 (=1/R2) experiments employed delays of 10.1, 128.6, 514.6, 643.3, 1286.6, 2058.6, and 2573.2 msec for T1, and 0, 15.9, 31.9, 47.9, 63.8, 79.8, 95.7, and 111.6 msec for T2. The R1, R2, and XNOE experiments were collected in 1.5, 1.5, and 3 d, respectively.

NMR data processing and analysis

All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed using NMRView (Johnson and Blevins 1994). Heteronuclear dimensions were extended via linear prediction and zero-filled prior to Fourier transform. XNOE values were calculated as (I/Io), where I and Io represent the intensity ratio of the 15N-H correlation peak in the presence and absence of 3-sec proton saturation, respectively.

Sedimentation equilibrium

Sedimentation equilibrium (SE) data for CACTD-p2-NC and CA p24 were collected at speeds of 20,000 and 24,000 rpm at 20°C on a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge. All data were collected in absorbance mode at 280 nm. Sample conditions were 25 mM NaPO4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP, Calbiochem protease inhibitor cocktail set V (pH 6.5). CACTD-p2-NC initial concentrations were 10, 20, and 35 μM. Best global fits to a monomer-dimer equilibrium model were obtained for both CA p24 and CACTD-p2-NC using winNONLIN (Johnson and Faunt 1992), resulting in a Kd value of 1.78 ± 0.5 μM for CACTD-p2-NC and 2.94 ± 0.8 for CA p24.

Acknowledgments

We thank David King (HHMI, University of California, Berkeley, CA) for mass spectral measurements; Dr. Dorothy Beckett (University of Maryland) for assistance with sedimentation experiments; Robert Edwards and Yu Chen (HHMI, UMBC) for technical support; and Drs. Jamil Saad, Prem Raj Joseph (HHMI, UMBC), and Gaya Amarasinghe (University of Texas Southwestern Med. Center) for helpful suggestions. Support from the NIH (GM42561) is gratefully acknowledged.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type-1

CACTD, capsid C-terminal domain protein

CA p24, full-length capsid protein

p2, 14-residue protein within Gag

NC, nucleocapsid protein

MA, matrix protein

SE, sedimentation equilibrium

Kd, equilibrium dissociation constant

NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum correlation

HNCA, triple resonance experiment

HN(CO)CA, triple resonance experiment

2D, two-dimensional

3D, three-dimensional

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

R1 (T1), longitudinal relaxation rate (time)

R2 (T2), transversal relaxation (time)

XNOE, heteronuclear 15N{1H} nuclear Overhauser effect

TFE, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol

CSI, chemical shift index

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.04614804.

References

- Accola, M.A., Hoglund, S., and Gottlinger, H.G. 1998. A putative α-helical structure which overlaps the Capsid-p2 boundary in the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Gag precursor is crucial for viral particle assembly. J. Virol. 72 2072–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, A., Gendelman, H.E., Koenig, S., Folks, T., Willey, R., Rabson, A., and Martin, M.A. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe, G.K., De Guzman, R.N., Turner, R.B., Chancellor, K., Wu, Z.-R., and Summers, M.F. 2000. NMR structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to stem-loop SL2 of the Y-RNA packaging signal. J. Mol. Biol. 301 491–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin, J.M., Hughes, S.H., and Varmus, H.E. 1997. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [PubMed]

- De Guzman, R.N., Wu, Z.R., Stalling, C.C., Pappalardo, L., Borer, P.N., and Summers, M.F. 1998. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 Y-RNA recognition element. Science 279 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble, T.R., Yoo, S., Vajdos, F.F., von Schwedler, U.K., Korthylake, D.K., Wang, H., McCutcheon, J.P., Sundquist, W.I., and Hill, C.P. 1997. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278 849–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheysen, D., Jacobs, E., de Foresta, F., Thiriart, C., Francotte, M., Thines, D., and De Wilde, M. 1989. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor Pr55gag virus-like particles from recombinant baculovirus-infected insect cells. Cell 59 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitti, R.K., Lee, B.M., Walker, J., Summers, M.F., Yoo, S., and Sundquist, W.I. 1996. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 273 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, I., Hohenberg, H., Wilk, T., Wiegers, K., Grattinger, M., Muller, B., Fuller, S., and Krausslich, H.-G. 2000. A conformational switch controlling HIV-1 morphogenesis. EMBO J. 19 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek, S. and Bax, A. 1992. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 6291–6293. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.A. and Blevins, R.A. 1994. NMRview: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.L. and Faunt, L.M. 1992. Parameter estimation by least-squares methods. Methods Enzymol. 210 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Marion, D., and Bax, A. 1989. Practical aspects of 3D heteronuclear NMR of proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 84 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Clore, G.M., Bax, A., and Gronenborn, A.M. 1990. Four-dimensional heteronuclear triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy of interleukin-1b in solution. Science 249 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausslich, H.-G., Facke, M., Heuser, A.-M., Konvalinka, J., and Zentgraf, H. 1995. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency virus capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J. Virol. 69 3407–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.M., De Guzman, R.N., Turner, B.G., Tjandra, N., and Summers, M.F. 1998. Dynamical behavior of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 279 633–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C., Hu, J., Russell, R.S., Roldan, A., Kleiman, L., and Wainberg, M.A. 2002. Characterization of a putative α-helix across the capsid-SP1 boundary θ is critical for the multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. J. Virol. 76 11729–11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C., Hu, J., Whitney, J.B., Kleiman, L., and Wainberg, M.A. 2003. A structurally disordered region at the C terminus of capsid plays essential roles in multimerization and membrane binding of the Gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 77 1772–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momany, C., Kovari, L.C., Prongay, A.J., Keller, W., Gitti, R.K., Lee, B.M., Gorbalenya, A.E., Tong, L., McClure, J., Ehrlich, L.S., et al. 1996. Crystal structure of dimeric HIV-1 capsid protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, S.C., Moody, M.D., Wehbie, R.S., Kaplan, A.H., Nantermet, P.V., Klein, C.A., and Swanstrom, R. 1994. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J. Virol. 68 8017–8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, S.C., Henderson, G.J., Schiffer, C.A., and Swanstrom, R. 2002. Replacement of the P1 amino acid of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag processing sites can inhibit or enhance the rate of cleavage by the viral protease. J. Virol. 76 10226–10233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reily, M.D., Thanabal, V., and Omecinsky, D.O. 1992. Structure-induced carbon-13 chemical shifts: A sensitive measure of transient localized secondary structure in peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 6251–6252. [Google Scholar]

- Rosé, S., Hensley, P., O’Shannessy, D.J., Culp, J., Debouck, C., and Chaiken, I. 1992. Characterization of HIV-1 p24 self-association using analytical affinity chromatography. Proteins 13 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers, M.F., Henderson, L.E., Chance, M.R., Bess, J.W.J., South, T.L., Blake, P.R., Sagi, I., Perez-Alvarado, G., Sowder, R.C.I., Hare, D.R., et al. 1992. Nucleocapsid zinc fingers detected in retroviruses: EXAFS studies of intact viruses and the solution-state structure of the nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Protein Sci. 1 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C., Ndassa, Y., and Summers, M.F. 2002. Structure of the N-terminal 283-residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C., Loeliger, E., Luncsford, P., Kinde, I., Beckett, D., and Summers, M.F. 2004. Entropic switch regulates myristate exposure in the HIV-1 matrix protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101 517–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.G. and Summers, M.F. 1999. Structural biology of HIV. J. Mol. Biol. 285 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, V. 1996. Proteolytic processing and particle maturation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214 95–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegers, K., Rutter, G., Kottler, H., Tessmer, U., Hohenberg, H., and Krausslich, H.-G. 1998. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual Gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J. Virol. 72 2846–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills, J. and Craven, R. 1991. Form, function, and use of retroviral gag proteins. AIDS 5 639–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Sykes, B.D., and Richards, F.M. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222 311–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worthylake, D.K., Wang, H., Yoo, S., Sundquist, W.I., and Hill, C.P. 1999. Structures of the HIV-1 capsid protein dimerization domain at 2.6 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 55 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley, New York.

- Yoo, S., Myszka, D.G., Yeh, C., McMurray, M., Hill, C.P., and Sundquist, W.I. 1997. Molecular recognition in the HIV-1 capsid/cyclophilin A complex. J. Mol. Biol. 269 780–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]