Abstract

A comparative study on the solution structures of bovine microsomal cytochrome b5 (Tb5) and the mutant V45H has been achieved by 1D and 2D 1H-NMR spectroscopy to clarify the differences in the solution conformations between these two proteins. The results reveal that the global folding of the V45H mutant in solution is unchanged, but the subtle changes exist in the orientation of the axial ligand His39, and heme vinyl groups. The side chain of His45 in V45H mutant extends to the outer edge of the heme pocket leaving a cavity at the site originally occupied by the inner methyl group of Val45 residue. In addition, the imidazole ring of axial ligand His39 rotates counterclockwise by ~3° around the His-Fe-His axis, and the 4-heme vinyl group turns to the space vacated by the removed side chain due to the mutation. Furthermore, the helix III of the heme pocket undergoes outward displacement, while the linkage between helix II and III is shifted leftward. These observations are not only consistent with the pattern of the pseudocontact shifts of the heme protons, but also well account for the lower stability of V45H mutant against heat and urea.

Keywords: cytochrome b5, mutant V45H, NMR, solution structure

Cytochrome b5 (Cyt b5) is a membrane-bound protein, and functions as an electron carrier, participating in a series of electron-transfer processes in biological systems (Strittmatter and Velick 1957). It contains a heme moiety with two histidine residues as its axial ligands. The His/His ligation rules out ligand binding in a physiological process and keeps its heme cycling between Fe2+ and Fe3+ forms. Val45 of Cyt b5 is a highly conserved residue in the heme hydrophobic pocket and involved in the hydrophobic interaction with Ala81 of Cyt c (Wu et al. 2000). It is located at the left side of the axial ligand His39 (in the view from His39), and is in contact directly with the heme. It is predicted that the mutation at this site may cause perturbation on the orientation of the heme and the axial ligand plane, and provide information on how the geometry of the axial ligands influences the microenvironments of the heme pocket, as well as the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties. To illustrate the importance of Val45, three mutants (V45Y, V45H, and V45E) were constructed to examine the effects of the polarity, electric charge, and volume of the substituted residues on stability and redox potential of the protein. All of these mutants have been characterized, and their physical and electrochemical properties have also been reported (Wang et al. 2000). The redox potentials of V45Y, V45H, V45E, and the wild-type (WT) bovine cytochrome b5 (Tb5) are −35 mV, (8 mV, −26 mV, and −10 mV, respectively. Also, the stability of these mutants toward heat and urea is lower than that of Tb5. Therefore, the 3D solution structures of bovine Tb5 and its mutants may provide a solid base to understand the factors that govern the physical and chemical properties of the mutants.

In our previous study (Cao et al. 2003), 1D and 2D 1H NMR spectra were employed to probe the influences on the heme microenvironment of cytochrome b5 caused by the mutations. The results demonstrated that the ratios of heme isomers (major to minor) are smaller than that in Tb5. The 4-vinyl group of the heme in Tb5 assumes cis-orientation, while that was predicted to take both cis- and trans-orientation in the mutants. In addition, on the basis of the evaluation of the pseudocontact shifts of the heme protons the torsion φ angle between the Fe-N(II) axes and the average plane of two axial ligands was predicted to be smaller by ~3° than that of the WT protein. However, it was not clear that the change in the φ angle should be attributed to the heme rotation around its normal, or to the orientation variation of the axial ligand planes about His-Fe-His axis.

To discover the reason for the variation in the heme geometry and changes in the orientation of the axial ligands and heme vinyl groups, the 3D structures of Tb5 and its mutant V45H in solution have been determined by 1D and 2D1H-NMR spectroscopy under the same condition. Herein, we report the solution structures of Tb5 and its mutant V45H. Two structures are superimposed and compared in detail to demonstrate the subtle variations in the φ angle, orientation of the axial ligand and the heme vinyl groups, as well as in the local conformation of the helix III and the linkage between helix II and III. How the structural variations influence the properties and biological function of the proteins, such as the hydrophobicity of heme pocket, the binding between the heme and protein matrix and the redox potential, as well as the stability against heat-induced denaturation are also presented.

Materials and methods

NMR sample preparation

The oxidized-state trypsin-solubilized bovine liver microsomal cytochrome b5 (Tb5) and the mutant V45H were expressed and purified as previously described (Brautigan et al. 1978). The proteins were dissolved in a deuterated 25 mM aqueous phosphate buffer, and the pH of the solution was carefully adjusted to 7.0. The concentration of the NMR sample is ~3 mM.

NMR spectroscopy

1H-NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian unity Inova600 spectrometer operating at a proton Larmor frequency of 600.145 MHz. To detect connectivities among hyperfine-shifted signals, a NOESY spectrum (Macura et al. 1982; Marion and Wüthrich 1983) with a recycle time of 100 msec and mixing time of 30 msec and within a spectral width of 53 ppm in both frequency dimensions was acquired. To optimize the detection of connectivities in the diamagnetic region (~−3.5 ppm to 12.5 ppm), NOESY spectra were recorded with recycle time of 1.5 sec and mixing times of 50 msec, 100 msec, 150 msec, and 200 msec, respectively. TOCSY (Bax and Davis 1985) and DQF-COSY (Rance et al. 1983; Derome and Williamson 1990) spectra were recorded in H2O and D2O, respectively. All data consisted of 4 K data points in the acquisition dimension and 1 K experiments in the indirect dimension. Raw data were weighted with a squared cosine function, zero-filled, and Fourier-transformed to obtain a final matrix 4096 × 4096 data points. All spectra were collected at 293 K either on the H2O or on the D2O samples and were processed using the Varian software VNMR (version 6.1B) and analyzed through the XEASY program (Eccles et al. 1991).

Constraints used in structure calculations

Intensities of dipolar connectivities were converted to upper distance limits, which were used as the input file for the structure calculation. The peak volumes measured in NOESY spectra acquired with different mixing times were calibrated simultaneously using a scaling factor for the intensities of well-defined and isolated peaks in one spectrum with respect to the others using the program CALIBA (Guntert et al. 1991). Stereospecific assignments were obtained by the program GLOMSA (Guntert et al. 1991) based on the preliminary calculated structures.

Pseudocontact shifts (pcs) were used as additional constraints in the calculation and given by equation 1 (Kurland and McGarvey 1970):

|

(1) |

Therein Δ χax and Δ χth are the axial and rhombic magnetic susceptibility anisotropies, ri the length of the nuclei i from the metal ion, and li, mi, and ni are the direction cosines of the position vector of atom i with respect to the orthogonal reference system formed by the principle axes of the magnetic susceptibility tensor. The pseudocontact shifts were obtained by subtracting the shifts of the reduced form, which was estimated for the WT protein, from the observed chemical shifts of the oxidized form of the variant V45H. The pcs constraints were derived by fitting equation 1 through the program FANTASIAN (Banci et al. 1996, 1997b), using a preliminary family of 30 conformers as the input model. The fitting was performed separately on each member of the family and the averaged value of Δ χax and Δ χrh was taken as starting value in the PSEUDYANA structure calculation. An upper distance limit of 0.2 Å was set between the pseudoatom defining the origin of the magnetic anisotropy tensor and the iron atom of the heme residue. The location of this residue and the tensor orientation were optimized during the structure calculations until the final values deviation no more than 5% from the initial ones. Because the reduced Tb5 was used as a model to calculate the pcs, to avoid the calculation errors caused by the mutation, no pcs constraints were introduced for the residue that was mutated and for its neighboring residues. Meanwhile, no pcs restraints were used for the heme and the axial heme ligands (His39 and His63) that experienced a nonnegligible contact shift.

Structure calculations

The structures were calculated using the program DYANA 1.5 (Guntert et al. 1998). It contains the program PSEUDYANA (Banci et al. 1998), which made it suitable for the incorporation of pcs restraints. A preliminary family of 30 conformers was obtained using NOE constraints and the pcs constraints. Two axial ligands (His39 and His63) were coordinated to the iron atom by additional upper (2.10 Å) and lower (1.90 Å) distance limits from Nɛ2 atoms to the central iron atom in the structure calculation. Additionally, no angle is imposed between the heme plane and the Hisiron bond. In particular, no assumption was made on the location of the heme group and the iron (III) ion, which were determined only by the NOEs and the pcs. Restrained energy minimization (REM) was then applied to each member of the family by using the AMBER Package (Pearlman et al. 1997), and the pseudocontact shifts were included as constraints by means of the module PCSHIFTS.

Results

Sequence-specific assignment

Extensive lists of assignments for the oxidized cytochrome b5 from different organisms have been reported in the literature (Lee et al. 1990). In many cases, there are two forms in solution due to two conformations of heme ring differing by an 180° rotation around the meso-α, γ axis (Kellor and Wüthrich 1980). In our experiments, two forms are observed in the solution. The ratios of two forms are 6.5:1 for Tb5 and 4.3:1 for V45H, respectively (Cao et al. 2003). The assignments obtained in this study are extended to ~80% of the total protons including those of the heme and all residues except for Ala3. Most of the present assignments are consistent with the data reported in literature referred to oxidized bovine cytochrome b5. The assignment data were involved in supplemental materials.

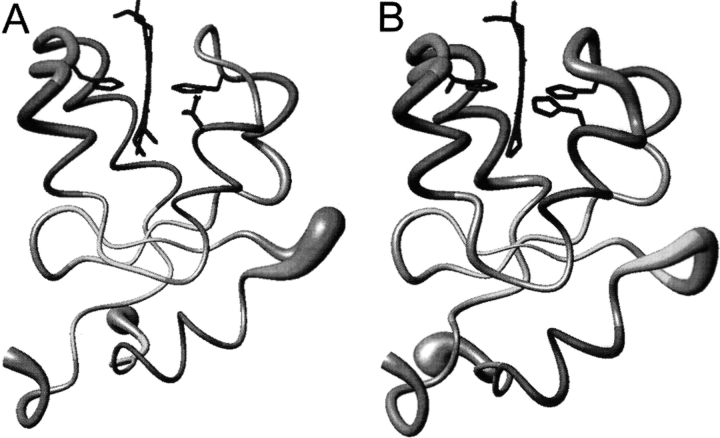

Secondary structures from NMR data

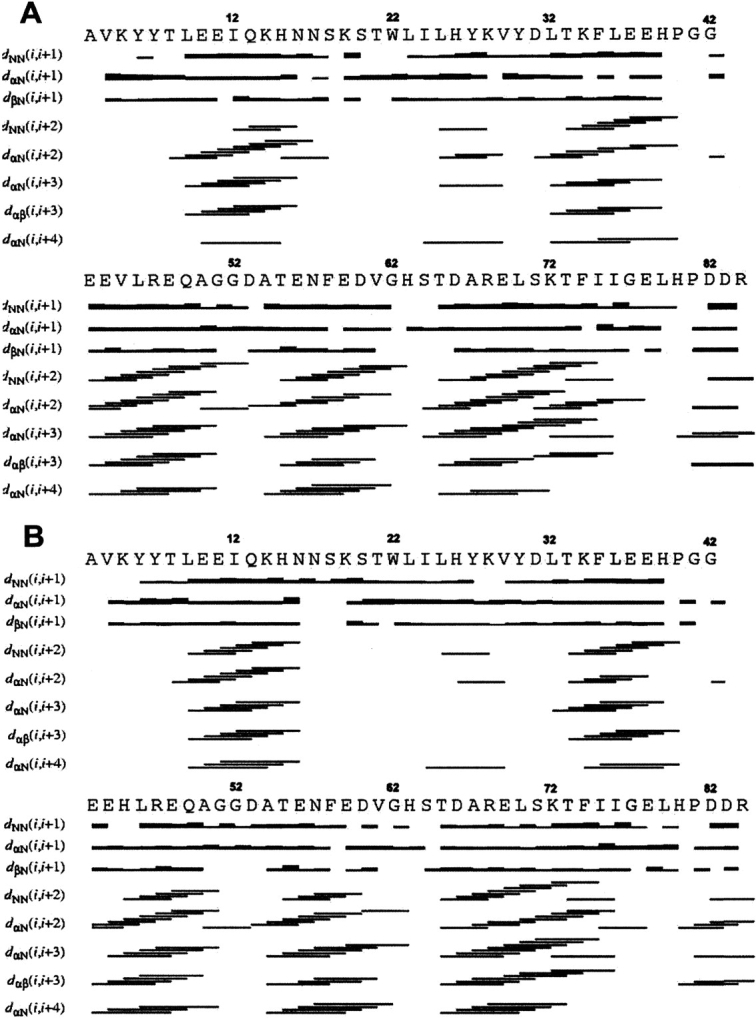

The elements of secondary structure were identified by interpreting the pattern of assigned NOEs. Short- and medium-range NOE networks in proteins were summarized in Figure 1 ▶, from which five elements of helical secondary structure were identified. They were similar to the helical secondary structural elements present in all cytochrome b5 crystal and solution structures (Banci et al. 1997a; Wu et al. 2000), except for the length of a few helices. The pattern of long-range NOEs (data not shown) revealed the existence of a β-sheet centered on the antiparallel β-strands (residues 21–25 and 28–32), the former being parallel to the segment 51–54, and the latter antiparallel to the region 75–79. Besides, a parallel β-sheet was also observed for the segments 78–80 and 5–7. In these regions, the protons NH23, NH24, NH25, NH29, NH30, NH31, NH32, and NH76 were slowly exchanged amide protons, which are consistent with tight elements of β-secondary structure.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the short- and medium-range NOE connectivities of proteins: Tb5 (A) and the mutate V45H (B).

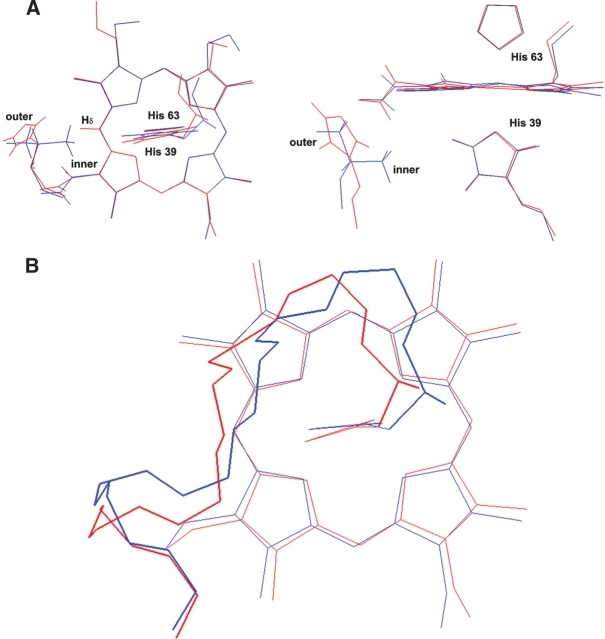

Solution structure of Tb5

A total of 1488 NOE distance constraints, 33 stereospecific assignment constraints, and 206 pseudocontact shift constraints were used in the structure calculation. The relative weight for all kinds of constraints above was kept equal. Two hundred random structures were annealed in 15,000 steps with the above constraints. A family of 30 structures obtained from PSEUDYANA with the lowest target function has the RMSD values of 0.49 ± 0.09 Å and 1.20 ± 0.13 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively (calculated for residue 5–80). Ten iterations of PSEUDYANA calculation were performed before the magnetic anisotropy tensor reached convergence. Then, the family of the structures was subjected to further refinement with the program AMBER. The resulting family has the RMSD values of 0.53 ± 0.12 Å and 1.25 ± 0.17 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively. Figure 2A ▶ shows the resulting average structure of the family represented as a tube whose radius is proportional to the RMSD of the family, which is characterized by high resolution in regions close to the paramagnetic center. The RMSD values for the backbone and heavy atoms are reported in supporting materials. The quality of the structure in terms of stereochemical parameters was evaluated using the program PROCHECK_NMR (Laskowski et al. 1996). Analysis of the ensemble of 30 Tb5 structures using PROCHECK_NMR revealed that 79.6% of residues lie in most favored regions, 17.9% of residues in additionally allowed regions, and 1.4% of residues in generously allowed regions of the Ramachandran φ, ψ dihedral angle plot (plot not shown).

Figure 2.

The average solution structures of the Tb5 (A) and V45H (B) represented as a tube whose radius is proportional to the RMSD values of the proteins.

Solution structure of V45H

A total of 1682 NOE distance constraints, 24 stereospecific assignments constraints, and 209 pseudocontact shift constraints were used in structure calculation. Two hundred random structures were annealed in 15,000 steps with the above constraints. A family of 30 structures obtained from PSEUDYANA with the lowest target function has the RMSD values of 0.43 ± 0.09 Å and 1.02 ± 0.13Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively (as above). Then, the family of the structures was subjected to further refinement with the program AMBER. The resulting family has the RMSD values of 0.47 ± 0.09 Å and 1.11 ± 0.18 Å for backbone and heavy atoms, respectively. Figure 2B ▶ shows the resulting average structure of the family represented as a tube. The RMSD values for the backbone and heavy atoms are reported in supplemental materials. PROCHECK_NMR Analysis of the ensemble of 30 structures revealed that 73.3% of residues lie in most favored regions, 19.5% in additionally allowed regions, and 3.4% in generously allowed regions of the Ramachandran φ, ψdihedral angle plot.

The magnetic susceptibility tensor

The final Δχax and Δχrh values are 2.14 × 10−32 m3 and −0.89 × 10−32 m3 (Tb5), 2.53 × 10−32 m3 and −0.85 × 10−32 m3 (V45H), respectively. They are slightly different from those previously reported in the literature for rat and rabbit cytochrome b5 (Δχax = 2.83 × 10−32 m3, Δχrh = −1.06 × 10−32 m3; Δχax = 2.66 × 10−32 m3, Δχrh = −0.91 × 10−32 m3) (Amesano et al. 1998; Banci et al. 2000) and those for bovine cytochrome b5 four-site mutant (Δχax = 2.71 × 10−32 m3, Δχrh = −1.07 × 10−32 m3) (Wu et al. 2001). The principal Z-axis of the magnetic susceptibility tensor is nearly aligned to the perpendicular to the mean heme plane, making an angle of 7° (Tb5) and 9° (V45H) with it.

Discussion

In this study, 3D structures of Tb5 and its mutant V45H in solution were determined under the same conditions. Thus, it allows us to compare their conformation in solution, to evaluate the influences of structural variation on the properties of the proteins and to clarify the reason for their different behaviors, such as pseudocontact shifts, redox potential, and stability against heat and urea.

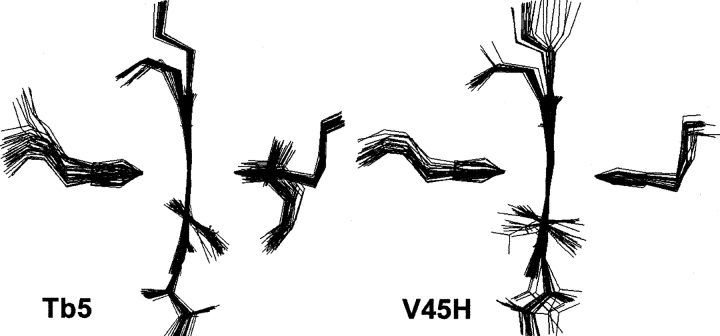

Variation in the geometry of the heme and the axial ligands

Figure 3A ▶ shows the comparison of the orientations of two axial ligands between the solution structures of Tb5 and V45H. The torsion angle between the imidazole ring of His39 and the Fepyrrol II N axis in the solution structure of Tb5 is −39.1°, while it was −29.4° in the solution structure of V45H. This suggests that the imidazole ring of His39 rotated CCW by 9.6° about the heme normal in view from His39. Meanwhile, the torsion angles between imidazole ring of His63 and Fepyrrol N (II) axis are −32.0° in the solution structure of Tb5 and −35.7° in the solution structure of V45H, respectively, indicating a rotation of the imidazole ring of His63 by 3.7° in the CW direction. Therefore, the φ angles between the Fepyrrol N (II) axis and the average plane of two axial ligands are −35.6° and −32.6° in the solution structures of Tb5 and V45H, respectively. The average plane of two axial ligands in the mutant rotates CCW ~3° due to the mutation. These results are well consistent with those predicted from the pseudo contact shifts of the heme proton (Cao et al. 2003). From Figure 3A ▶, it is also clear that the rotation of the heme is very subtle, and the variation of the φ angel is mainly resulted from the CCW rotation of the imidazole ring of His39.

Figure 3.

The superimposed diagram of V45H and WT proteins: (A) The comparison of the orientations of two axial ligands and the side chain of residue 45 in Tb5 (blue) and V45H (red). (B) The comparison of the conformation of helix III and the linkage between helix II and III (fit residues from 30 to 39 and 54 to 73) of REM mean structures of Tb5 (blue)/V45H (red).

It is interesting why the replacement of Val45 with His45 causes the change of the φ angle. As noted previously, Val45 is a highly conserved and hydrophobic residue in Tb5. Two methyl groups (denote as outer and inner methyl, respectively) of the side chain of Val45 are important components of hydrophobic heme pocket on the helix III. As shown in Figure 3A ▶, the outer methyl group extends to the edge of the heme, while the inner methyl group locates at the left side of axial ligation residue His39, and is very close to the Hɛ1 proton of the imidazole ring of His39. The distance between the nearest proton of the inner methyl and Hɛ1 proton of the imidazole ring of His39 is ~2.3 Å, and the free rotation of imidazole ring of His39 is restrained due to the van der Waals contact between these two groups. However, in the mutant V45H the residue His45 is lack of a γ-methyl group and its side chain is much longer than that of the Val residue. Hence, the side chain of His45 takes the orientation as that of the outer methyl group of Val45 in WT b5 to avoid unfavorable van der Waals contact with the heme. The imida/zole ring of His45 lies at outer edge of the heme pocket, which is evidenced by the abnormal high field chemical shift of Hβ, as previously documented (Cao et al. 2003). On the other hand, His45 is a polar residue with a positive charge. Thus, the outward orientation of the side chain of His45 is preferred to avoid decreasing the free energy of the hydrophobic heme pocket. Therefore, a cavity is created at the site originally occupied by the inner methyl group of Val45. The volume of the cavity could be estimated from the distance between the Nɛ2 atom of imidazole ring of His39 and the nearest atom of residue 45 in the vicinity of the replacement. When Val45 is replaced with His45, the nearest atom in the vicinity of the replacement is the β-carbon of His45. The distance between the β-carbon of His45 and the Nɛ2 atom of His39 is 7.5 Å, and the vacancy in the vicinity of the replacement is estimated as a cubic of 3.5 Å according to Matthews’ approach (Eriksson et al. 1992b). Because formation of a cavity in the hydrophobic core of the protein is expected to reduce favorable van der Waals contacts and stability, the protein structure tends to relax somewhat in response to the mutation. Therefore, the cavity allows the CCW rotation of the imidazole ring of His39 to increase the overall compactness of the protein.

Variation in conformation of the helix III of V45H

On the other hand, Figure 3B ▶ clearly shows that the local conformation of helix III and the linkage between helix II and helix III (cover residue 39–42) are changed in the V45H mutant. The peptide backbone of the helix III shows a little outward displacement from the heme center in the V45H solution structure. The extent, by which the helix III shifted outward can be estimated by the distances between the Nɛ2 atom of His39 and the β-carbon of residue 45, in both Tb5 and the mutant. The distance in Tb5 is 7 Å, while it is 7.5 Å in the mutant. Thus, the helix III is shifted away from the heme center and is estimated to be 0.5 Å. Meanwhile, the linkage between the helix II and helix III is deviated toward the left side as well, in comparison with that of Tb5. These conformation variations may be related to the outward orientation of the side chain of His45 and the CCW rotation of the imidazole plane of the axial ligand His39. As described in the previous section, the imidazole ring of His45 extended to the outer edge of the heme pocket due to its big volume and polarity. Meanwhile, The CCW rotation of the imidazole plane of His39 requires adjusting the orientation of the peptide chain to maintain the ligation of His39 to the heme. These structural variations may pull the linkage (His39–Pro40) between helix II and III and the head part (Gly41–Glu42) of the helix III moving to the left side of the molecule.

Orientation of the heme vinyl groups in the mutant

In our former study (Cao et al. 2003), the orientations of heme vinyl groups were predicted on the basis of NOE observations: 4-heme vinyl groups are only in the cis-orientation in Tb5, while for the V45H mutant, both the cis-and trans-orientation of the 4-vinyl group are observed.

From the solution structures determined in this paper, the cis-orientation of 4-heme vinyl group in Tb5 is confirmed, but the vinyl group and heme moiety are not in a plane. The vinyl group actually is tilted toward the inner methyl of Val45 by a torsion angle of, on average, 56°, with the heme moiety in the mean structure, which is a little bigger than that (43°) in the X-ray structure (Fig. 4 ▶). On the other hand, the orientations of 4-vinyl groups in the family of solution structures of the V45H mutant are not homogenous, as shown in Figure 4 ▶. Among 30 solution structures, 20 conformers have their heme 4-vinyl groups oriented to the cavity by a torsion angle of ~77°, on average, in respect to the heme moiety. The other 10 conformers have their 4-vinyl groups oriented to the opposite side of the molecule.

Figure 4.

The orientations of the heme moieties and heme vinyl groups in Tb5 and V45H.

Furthermore, the conformations of the heme moieties in the family of the Tb5 solution structures are highly convergent as shown in Figure 4 ▶, and two heme vinyl groups are all in the cis-orientation. Compared with Tb5, the conformations of the heme moieties in the V45H mutant are less convergent. In addition, the heme 2-vinyl groups in the family of the mutant solution structures show inhomogeneous orientations (oriented toward both sides of the heme). These facts indicate that the binding between the heme and protein matrix in Tb5 is very tight, while in the V45H mutant the binding between them is much looser. These structural changes of the molecule should give unfavorable influences on the interaction between the heme and the protein matrix, and resultantly, on the stability of the mutant protein against heat and urea, which will be discussed later in detail.

Factors influencing the stability of the mutants

The stability of the variant V45H toward heat and urea has been reported to be much lower than that of Tb5 (Wang et al. 2000). In the thermodynamic analysis for thermal denaturation, the mutant V45H demonstrated lower melting temperature (Tm 61.6°) compared with that (66.7°) of Tb5 by the ΔTm value of −5.1°. In addition, the free energy cost of the heat denaturation is −5.6 kJ/mole (equal to ~−1.34 kcal/mole−1).

In 1992, Matthews and colleagues (Eriksson et al. 1992a,b) reported that mutations in which a bulky buried residue is replaced with a small residue could create cavities in the hydrophobic core of a protein. The sizes and the shapes of such cavities can vary substantially, depending on factors such as local geometry, whether or not a cavity already exist at the site of substitution, and the degree to which the protein structure relaxes to occupy the space vacated by the substituted residue. The introduction of a hydrophobic cavity into a protein is expected to reduce stability, and the destabilization scale is related with the cavity size. For their cases (T4L lysozyme), the energy term that increases with the size of the cavity can be expressed either in terms of the cavity volume (24–33 cal mole−1 Å−3) or in terms of the surface area (20 cal mole−1 Å−2). In the present case, the volume of the cavity resulted from the replacement of Val with His in the mutant V45H is ~42.9 Å3 (a cubic of 3.5 Å), and the free energy cost of the heat denaturation is ~−1.34 kcal/mole-1. Therefore, the destabilization scales linearly with cavity size in cytochrome b5 is ~31.2 cal mole−1 Å−3, which is comparable with that reported for T4 lysozyme.

As noted previously, Val45 is a highly conserved and hydrophobic residue and its two methyl groups in the side chain of Val45 make up the inner wall of the heme hydrophobic pocket on the helix III. The inner methyl group of Val45 is very close to axial ligand His39, and supports the imidazole ring of His39 at its equilibrium position. Meanwhile, the outer methyl lies at the outer edge of the heme pocket to protect the hydrophobic heme pocket from the access of water molecules. Therefore, the heme including its two vinyl groups, axial ligands, and protein matrix in Tb5 are packed perfectly, and the heme and heme pocket fit each other very well. On the other hand, the creation of a cavity in the hydrophobic pocket of the mutant would remove favorable van der Waals interactions existing in the protein. To respond to the mutation, readjustment of the protein takes place to reduce the size of the cavity and to increase the overall compactness of the protein, that is, to restore protein stability. In mutant V45H the replacement of Val with His residue forms a cavity of 42.9 Å3 in the heme pocket, which allows the surrounding groups, such as 4-vinyl and imidazole ring of His39, to turn slightly to the cavity.

In addition, the outward displacement of helix III and the conformation change of the link-bridge between helix II and III also make the binding of the heme and its protein pocket much looser and cause the protein to become unstable. Furthermore, the replacement of the hydrophobic methyl group of Val45 in Tb5 by a polar imidazole ring with a positive charge of His45 in the mutant leads to the decrease of the hydrophobicity of the heme pocket and an increase of the accessibility of water to the heme pocket. The change of the hydrophobicity of the heme pocket due to the introduction of a polar group and positive charge on the 45th residue diminishes the interaction between the heme and its pocket. Therefore, these structural variations in the solution structure provided a reasonable explanation for the lower stability of the V45H mutant.

The redox potential of V45H

Investigations of electron transferring on V45H showed that the redox potential of the mutant is positively shifted by 11 mV, and the electron transfer rate becomes slower (Wang et al. 2000). In the present system, the decrease in hydrophobicity of the heme pocket of the mutant may negatively affect the reduction potential. Also, in the mutant, the average plane of two axial ligands rotated CCW by ~3° (view from His39); this may decrease the spin density delocalization from Fe (III) to heme 3e(π) molecular orbitals, and results in a negative change of the redox potential. The multiple orientation of the heme 2- and 4-vinyl groups of the V45H mutant in the solution also has a negative effect on the redox potential.

However, it was reported that the electrostatic potential around the heme-exposed area dominates the redox potential of the heme proteins. In the case of a negatively charged protein such as cytochrome b5, the introduction of a positive charge at the heme-exposed surface always stabilize the reduction state of the iron ion, and make the redox potential shift positively. For the mutant V45H, a positive charge was introduced into the heme-exposed surface by residue His45. Therefore, the decrease in the density of negative charge at the heme-exposed area leads to the redox potential moving positively.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study provided further insight into the importance of residue Val45 in cytochrome b5. Val45 is a conserved residue, and two methyl groups in its side chain are key components of the hydrophobic heme pocket on the helix III. The outer methyl group is located at the edge of heme to protect the hydrophobic heme pocket from the access of water molecules in solution. The inner methyl makes favorable van der Waals contacts with the axial ligand His39 and 4-vinyl group, and is crucial for the stabilization of the conformation of these two components of the electron-transferring system. The mutation of Val45 by a His residue resulted in the formation of a cavity at the space occupied by the inner methyl of Val45, which leads to the CCW rotation of the axial ligand His39 and the inhomogeneous orientations of the heme 2- and 4-vinyl groups. Furthermore, introducing a polar imidazole moiety with a positive charge at the exposed surface of the heme pocket leads to a decrease of the hydrophobicity of the heme pocket. Therefore, these structural variations disrupted the perfect packing of the heme moiety, heme vinyl groups, and the axial ligands in the molecule, and weakened the binding of the heme with the protein hydrophobic pocket, and consequently, rationalized the changes in the properties and the stability of the mutant. The results obtained in this study also provide additional data for the general attempt to quantitate the energy cost of cavity creation in proteins.

Data deposition

The codes of the solution structures of the WT cytochrome b5 (Tb5)and its mutant V45H in the Protein Data Bank are 1NX7 and 1SH4.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by National Science Foundation of P.R. China (no. 20132030) and by Chinese Academy of Sciences. The authors are indebted to the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biophysics, ETH-Hönggerberg Zürich, Switzerland, for the programs CALIBA, DYANA (version 1.5), and XEASY, and to Prof. Bertini of the Florence University, Italy, for the programs PSEUDYANA and PCSHIFT. We also thank Prof. James W. Caldwell of UCSF, for the program AMBER (version 5.0), and Tripos Inc. for SYBYL software.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

1D, one-dimensional

2D, two-dimensional

3D, three-dimensional

CCW, counterclockwise

DQF-COSY, double-quantum-filtered correlation spectroscopy

NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance

NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

ppm, parts per million

REM, restrained energy minimization

Tb5, trypsin-solubilized cytochrome b5

TOCSY, total correlated spectroscopy

WT, wild type

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.04721104.

References

- Amesano, F., Banci, L., Bertini, I., and Felli, I.C. 1998. The solution structure of oxidized rat microsomal cytochrome b5. Biochemistry 37 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Bren, K.L., Cremonini, M.A., Gray, H.B., Luchinat, C., and Turano, P. 1996. The use of pseudocontact shifts to refine solutions structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins: Met80Ala cyanocytochrome c as an example. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Ferroni, F., and Rosato, A. 1997a. Solution structure of reduced microsomal rat cytochrome b5. Eur. J. Biochem. 249 270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Gori Savellini, G., Romagnoli, A., Turano, P., Cremonini, M.A., Luchinat, C., and Gray, H.B. 1997b. Pseudocontact shifts as constraints for energy minimization and molecular dynamics calculations on solution structures of paramagnetic metalloproteins. Proteins 29 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Cremonini, M.A., Gori Savellini, G., Luchinat, C., Wüthrich, K., and Guentert, P. 1998. PSEUDYANA for NMR structure calculation of paramagnetic metalloproteins using torsion angle molecular dynamics. J. Biomol. NMR 12 553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banci, L., Bertini, I., Rosato, A., and Scaacchier, S. 2000. Solution structure of oxidized microsomal rabbit cytochrome b5. Factors determining the heterogeneous binding of the heme. Eur. J. Biochem. 267 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, A. and Davis, D.G. 1985. MLEV-17-based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 65 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Brautigan, D.L., Ferguson-Miller, S., and Margoliash, E. 1978. Mitochondrial cytochrome c: Preparation and activity of native and chemically modified cytochrome c. Methods Enzymol. 53 128–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C., Zhang, Q., Wang, Z.Q., Wang, Y.F., Wang, Y.H., Wu, H., and Huang, Z.X. 2003. 1H-NMR studies of the effect of mutation at valine45 on heme microenvironment of cytochrome b5. Biochimie 85 1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derome, A.E. and Williamson, M.P. 1990. Rapid-pulsing artifacts in double-quantum-filtered cosy. J. Magn. Reson. 88 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, C., Guntert, P., and Wüthrich, K. 1991. Efficient analysis of protein 2D NMR spectra using the software package EASY. J. Biomol. NMR 1 111–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.E., Baase, W.A., Wozniak, J.A., and Matthews, B.W. 1992a. A cavity-containing mutant of T4 lysozyme is stabilized by buried benzene. Nature 355 371–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.E., Baase, W.A., Zhang, X.-J., Heinz, D.W., Blaber, W., Baldwin, E.P., and Matthews, B.W., 1992b. Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Science 255 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert, P., Braun, W., and Wüthrich, K. 1991. Structure determination of the Antp (C39S) homeodomain from nuclear magnetic resonance data in solution using a novel strategy for the structure calculation with the programs DIANA, CALIBA, HABAS and GLOMSA. J. Mol. Biol. 217 517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert, P., Mumenthaler, C., and Wüthrich, K. 1998. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellor, R.M. and Wüthrich, K. 1980. Structural study of the heme crevice in cytochrome b5 based on individual assignment of the 1H-NMR lines of the heme group and selected amino acid residues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 621 204–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland, R.J. and McGarvey, B.R. 1970. Isotropic NMR shifts in transition metal complexes: Calculation of the fermi contact and pseudocontact terms. J. Magn. Reson. 2 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., Rullmann, J.A.C., MacArthur, M.W., Kaptein, R., and Thornton, J.M. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.B., La Mar, G.N., Kehres, L.A., and Fujinari, E.M. 1990. Proton NMR study of the influence of hydrophobic contacts on protein prosthetic group recognition in bovine and rat ferricytochrome b5. Biochemistry 29 9623–9631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macura, S., Wüthrich, K., and Ernst, R.R. 1982. The relevance of J cross-peaks in two-dimensional NOE experiments of macromolecules. J. Magn. Reson. 47 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D. and Wüthrich, K. 1983. Application of phase sensitive two-dimensional correlated spectroscopy (COSY) for measurements of 1H-1H spin-spin coupling constants in proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 113 967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman, D.A., Case, D.A., Caldwell, J.W., Ross, W.S., Cheatham, T.E., Ferguson, D.M., Seibel, G.L., Singh, U.C., Weiner, P.K., and Kollman, P.A. 1997. AMBER 5.0. University of California, San Francisco, CA.

- Rance, M., Sorensen, O.W., Bodenhausen, G., Wagner, G., Ernst, R.R., and Wüthrich, K. 1983. Improved spectral resolution in COSY proton NMR spectra of proteins via double quantum filtering. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 117 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter, P. and Velick, S.F. 1957. The purification and properties of microsomal cytochrome reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 228 785–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q., Wang, Y.H., Wang, W.H., Xue, L.L., Wu, X.Z., Xie, Y., and Huang, Z.X. 2000. The effect of mutation at valine-45 on the stability and redox potentials of trypsin-cleaved cytochrome b5. Biophys. Chem. 83 3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Gan, J.H., Xia, Z.X., Wang, Y.H., Wang, W.H., Xue, L.L., Xie, Y., and Huang, Z.X. 2000. Crystal structure of recombinant trypsin-solubilized fragment of cytochrome b5 and the structural comparison with Val61His mutant. Proteins 40 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.B., Wang, Y.H., Qian, C.M., Lu, J., Li, E., Wang, W.H., Lu, J.X., Xie, Y., Wang, J.F., Zhu, D.X., et al. 2001. Solution structure of cytochrome b5 mutant (E44/48/56A/D60A) and its interaction with cytochrome c. Eur. J. Biochem. 268 1620–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]