Abstract

Phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT) catalyzes the penultimate step in prokaryotic coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis, directing the transfer of an adenylyl group from ATP to 4′-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) to yield dephospho-CoA (dPCoA). The crystal structures of Escherichia coli PPAT bound to its substrates, product, and inhibitor revealed an allosteric hexameric enzyme with half-of-sites reactivity, and established an in-line displacement catalytic mechanism. To provide insight into the mechanism of ligand binding we solved the apoenzyme (Apo) crystal structure of PPAT from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In its Apo form, PPAT is a symmetric hexamer with an open solvent channel. However, ligand binding provokes asymmetry and alters the structure of the solvent channel, so that ligand binding becomes restricted to one trimer.

Keywords: phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase, apoenzyme, coenzyme A, tuberculosis, X-ray structure

Members of the superfamily of nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterases share the ability to catalyze the transfer of adenylate groups from ATP to diverse substrates, for example, in the transfer of aminoacyl adenylates to cognate tRNAs by class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (First and Fersht 1993; Perona et al. 1993; Schmitt et al. 1994). The crystal structures of ligand-bound phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT), the penultimate and rate-limiting enzyme of bacterial coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis, revealed surprising structural similarities to nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterases (Izard and Geerlof 1999; Izard 2002). PPAT transfers an adenylyl group from ATP to 4′-phosphopantetheine (Ppant) to yield pyrophosphate and 3′-dephospho-CoA (dPCoA), and the latter is then phosphorylated to generate CoA (Robishaw and Neely 1985). Curiously, the crystal structures of Escherichia coli PPAT bound to either Ppant, ATP, or dPCoA revealed that PPAT is an allosteric hexameric enzyme with half-of-sites reactivity, and that it catalyzes its reaction by an in-line displacement mechanism (Izard and Geerlof 1999; Izard 2002). In part, this occurs through binding of the adenyl moiety to PPAT (Izard 2002), in a fashion akin to the binding of ATP to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (First and Fresht 1993), and PPAT catalysis was shown to involve invariant His 18 present in a T/HxGH motif, which is a hallmark for many enzymes of the nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterase superfamily (Izard 2002).

A striking feature of PPAT is that its mode of product formation is highly concerted, with only one trimer of the PPAT hexamer binding to Ppant or dPCoA, whereas both trimers bind to ATP (Izard and Geerlof 1999; Izard 2002). The structures of the catalytic center of E. coli PPAT bound to Mn2+-ATP or Ppant revealed roles for the side chain of invariant His 18 in stabilizing the pentacovalent intermediate, whereas those of conserved Thr 10 and Lys 42 were shown to orient the nucleophile of Ppant for attack on the α-phosphate of ATP (Izard 2002). The crystal structure of the enzyme in complex with dPCoA also showed that binding to dPCoA provoked a vice-like movement of residues that line the surface of the active site (Izard and Geerlof 1999). Finally, the high-resolution crystal structure of PPAT in complex with CoA, which feedback inhibits the enzyme (Izard 2003), revealed, surprisingly, that CoA bound to the “unoccupied” trimer present in the PPAT:Ppant and PPAT:dPCoA complex. In this scenario, the binding of the adenylyl moiety of CoA is distinct, and does not overlap with the adenylyl binding site of dPCoA. Furthermore, although both pantotheine moieties bind within the exact same pocket of the active site within the two protomers, the pantotheine arm of CoA bends in the opposite direction of that observed for the pantotheine arm of dPCoA when bound to PPAT. Finally, the crystal structure of the PPAT:CoA complex indicates that the exclusive nature of CoA binding, but not of dPCoA binding, is due to steric constraints (Izard 2003).

Approximately 4%–5% of all reactions in intermediary metabolism rely on CoA as an essential cofactor (Begley et al. 2001). Given the high energetic costs associated with CoA biosynthesis it is not surprising that the pathway is regulated by feedback inhibition. This occurs at two levels in the biosynthetic pathway: at the level of the first enzyme, pantothenate kinase, and at the level of PPAT, and both of these enzymes are rate-limiting (Jackowski and Rock 1984). In eukaryotes, comparable enzymes regulate CoA biosynthesis, yet the final two steps are catalyzed by a dual-function enzyme coined CoA synthase, which contains a PPAT-like domain that functions in an autonomous fashion (Aghajanian and Worrall 2002; Daugherty et al. 2002; Zhyvoloug et al. 2002). However, from a structural standpoint CoA synthase is markedly different from the bacterial PPATs, suggesting that PPAT represents an excellent target for antibiotics, especially to combat deadly drug-resistant pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Recently, high-density mutagenesis has shown that the CoA pathway is essential in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG (Sassetti et al. 2003). Indeed, based upon the PPAT crystal structures a series of inhibitors have been generated that appear to effectively target the E. coli enzyme (Zhao et al. 2003). The appropriate design of such inhibitors, however, first requires a more thorough understanding of the dynamics of this bacterial enzyme. The first PPAT structure determined was that from E. coli in complex with dPCoA (Izard and Geerlof 1999), with ATP and with Ppant (Izard 2002), and in complex with CoA (Izard 2003). More recently, PPAT structures from other species have been reported. The crystal structure of PPAT from Bacillus subtilis has been determined in complex with ADP (PDBID 1O6B) to 2.2 Å resolution and that of Thermus thermophilus in complex with 4′-phosphopantetheine (Takahashi et al. 2004) to 1.5 Å. However, no structural information is available on unliganded PPAT. Here we report the X-ray structure of the Apo form of M. tuberculosis PPAT to 2 Å resolution. This is the first report of a three-dimensional structure of an enzyme of the CoA biosynthetic pathway from M. tuberculosis. Furthermore, these analyses define the first step in the catalytic cycle for nucleotidyltransferase α/β phosphodiesterases, and we discuss how the binding of ligands provokes conformational changes that switch a symmetrical apoenzyme to an allosterically regulated enzyme.

Results and Discussion

Overall structure of tuberculin PPAT

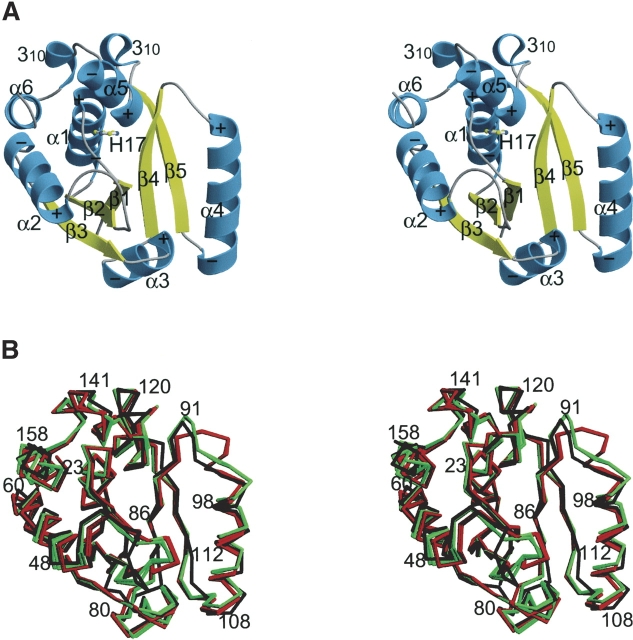

The structure of the M. tuberculosis PPAT subunit in the asymmetric unit is organized as a central β-sheet surrounded by α-helices (Fig. 1A ▶). The biological hexamer is generated by crystallographic two- and threefold symmetry. The electron density is missing (when contoured at 0.5 σ for the last four amino acids (158–161), and is weakest for the loop that connects β-strand β2 with the α-helix α2 (residues 40–41). This loop contains an invariant lysine involved in stabilizing the pentacovalent transition state of the α-phosphate during catalysis. CoA is known to copurify with PPAT (Geerlof et al. 1999) but the active site does not show electron density for CoA, and rather shows several ordered water molecules. Thus, our structure represents the apo-form of the tuberculin enzyme.

Figure 1.

The crystal structure of M. tuberculosis phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase (PPAT). (A) Stereocartoon drawing of the structure of the tuberculin PPAT protomer. αHelices are depicted by light blue helical ribbons and β strands by yellow arrows. The N terminus of each helix is marked with a positive sign while the C terminus of each helix is indicated with a negative sign, in agreement with the helix dipole moment. As in the case of other dinucleotide binding folds, PPAT is folded into two symmetrically related halves. The first half consists of three βstrands (β1, β2, and β3) connected by intervening β-helices (α1 and α2), while the second half contains two β strands (β4 and β5) related by α-helices (α3 and α4). A tandem repeated motif consisting of a short 310-helix followed by an α-helix (α5 and α6) comprises the C terminus. A short linker sequence connects the two halves of the fold. The catalytic histidine is shown in ball-and-stick representation. (B) Stereo Cα-trace superposition of tuberculin (black) PPAT onto coliform PPAT bound to ligands (red; Ppant or dPCoA bound subunits) and unliganded coliform PPAT (green). The view shown is the same view as that presented in (A). The largest discrepancies between the apo-form of PPAT (black) and the liganded subunits of E. coli PPAT (red) is found for residues located on the loop following β-strands β2 and β4. The largest difference between the M. tuberculosis apo-form PPAT structure and the E. coli PPAT structures is found for the loop connecting strand β2 with helix α2, which closes over the active site.

Comparison of tuberculin and E. coli PPAT

The tuberculin polypeptide chain has one deletion with respect to the E. coli protein in the loop connecting helix α4 and strand β5 and an overall sequence identity of 41% and a sequence similarity of 77%. In the E. coli PPAT structures, only one trimer within the hexamer (the “liganded” trimer) binds dPCoA in the PPAT:dPCoA structure or to Ppant in the PPAT:Ppant structure. Furthermore, although ATP was found bound to all six protomers within the PPAT hexamer, only the liganded trimer showed full ATP binding while the “unliganded” trimer indicated weak ATP binding as judged by the electron density and the refined temperature factors (Izard 2002). Finally, while CoA was found in all six subunits, the binding mode of CoA was significantly different in the “liganded” versus the “unliganded” trimer (Izard 2003). However, in all ligand-bound PPAT structures, the liganded trimers are more similar to each other than to any of the unliganded trimers.

Our M. tuberculosis PPAT apo-structure is most similar to the unliganded subunit of the E. coli enzyme (Fig. 1B ▶) and the Cα positions of the secondary structure elements (residues 3–8, 15–27, 30–36, 47–57, 64–69, 73–79, 120–122, 127–135, and 141–143) can be superimposed onto the 65 equivalent Cα positions of the unliganded subunit of the PPAT:ATP, PPAT:CoA, PPAT:Ppant, and PPAT:dPCoA structures with root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.61 Å, 0.65 Å, 0.66 Å, and 0.7 Å, respectively. By contrast, when superimposing our tuberculin apo-structure onto the liganded subunit of the PPAT:ATP, PPAT:CoA, PPAT:Ppant, and PPAT:dPCoA structures, the RMSD are 0.67 Å, 0.69 Å, 0.72 Å, and 0.77 Å, respectively (Fig. 1B ▶).

The most significant structural difference between the tuberculin PPAT apo-structure and either subunit of the four E. coli PPAT structures is found in the loop connecting β2 and α2 (residues 37–43;Fig. 1B ▶). Invariant Lys 41 is positioned at the tip of this loop, and is involved in stabilizing the pentacovalent transition state of the α-phosphate during catalysis (Fig. 2 ▶).

Figure 2.

Stereo superposition of the E. coli PPAT structure bound to dPCoA onto the M. tuberculosis PPAT apo-structure. Residues involved in binding to dPCoA or pyrophosphate, as seen in the E. coli PPAT:dPCoA structure, are shown in red and the equivalent residues found in the M. tuberculosis are shown in blue. The product (dPCoA) is shown in ball-and-stick representation. Movements of the catalytic lysine are indicated.

An additional difference in the conformation of the liganded subunit of the E. coli PPAT structures compared to our apo-form occurs on the loop connecting β4 and α4 M. tuberculosis PPAT residues 90–94; Fig. 1B ▶). This affects the position of invariant Arg 90, which is involved in stabilizing the β- and α-phosphates of ATP and facilitates the adoption of a productive conformation of the pyrophosphate group (Fig. 2 ▶).

Liganded and unliganded PPAT hexamers

As expected, when comparing either E. coli trimer within the hexamer to one of the two identical trimers in the M. tuberculosis hexamer, the ligand-free E. coli PPAT trimer superimposes better onto the apo-form than the liganded trimer (Fig. 3 ▶). In the globular shaped PPAT hexamer, a solvent channel runs though the entire oligomer along its triad (Fig. 4 ▶). The active sites of the subunits of the coliform enzyme face toward the inside of the large cavity of the solvent channel with a narrow cross-section at the center of the hexamer; therefore, substrates and products cannot diffuse from one trimer to the next within the E. coli PPAT hexamer. The mouth of the E. coli PPAT hexamer is lined with several hydrophilic residues (Lys 42, Lys 43, Arg 137, and His 138; Fig. 4B,C ▶ ). In contrast, the mouth of the channel of the M. tuberculosis PPAT hexamer has a Met 135 in place of Arg 137 and His 138 is replaced by Leu 136. Therefore, the mouth of the solvent channel of the tuberculin structure is more hydrophobic (Fig. 4A ▶).

Figure 3.

Cα trace superposition of the of E. coli PPAT (three shades of gray) hexamer as seen in the PPAT:dPCoA structure onto the apo-form of M. tuberculosis PPAT (three shades of red). The N and C termini are indicated. For clarity, the hexamer is depicted in two halves of trimers. (A) The 195 Cα positions of residues forming β strands or α helices of the unliganded E. coli PPAT trimer can be superimposed onto the equivalent Cα positions of the apo-from of M. tuberculosis PPAT with RMSD of 0.9 Å.

Figure 4.

Stereo electrostatic surface potential of the PPAT hexamer along the triad looking into the solvent channel. (A) The opening of the M. tuberculosis symmetric hexamer in its apo-form is much wider than that seen for the (B) unliganded E. coli PPAT trimer or the (C) liganded trimer within the asymmetric E. coli PPAT bound hexamer. The view of (C) is from the bottom of the view shown in (B); in other words, the view in (C) is rotated by 180° around a horizontal axis (red, negative; blue, positive; white, uncharged).

Comparison of the molecular surfaces of the apo-structure (Fig. 4A ▶) with those of the unliganded (Fig. 4B ▶) or liganded PPAT (Fig. 4C ▶) structure reveals that the apo-form has a much larger opening for the solvent channel. Residues located before and on helix α4 communicate with each other in a twofold related interaction. These residues (91–95 in E. coli ) are disordered in the ligand bound subunits, whereas they are ordered in the unliganded or apo-structure. Of course, in the symmetric hexamer of the apo-structure, the subunits across the dyad are related by a 180° rotation. However, in the half-of-sites bound E. coli PPAT structures, the liganded subunit can be superimposed onto the unliganded subunit by a rotation of 178.9°, which results in movements of almost 8 Å. Therefore, differences in subunit communication across the oligomer’s twofold axis relaxes, and opens the mouth of the solvent channel at the oligomer’s three-fold axis in the tuberculin apo-structure.

Moreover, the loop connecting β2 and α2 (residues 37–43) containing the catalytic Lys 41 residue located at the tip of the solvent channel closes over the active site upon ligand binding (Fig. 2 ▶). These movements of >8 Å are responsible for a wider solvent channel opening in the apo-structure compared to the ligand bound E. coli structures, and thus they also contribute in transitioning the enzyme from its symmetric to asymmetric forms. Of course, while it is tempting to speculate that the tuberculin enzyme might also display half-of-sites binding, further structural and biochemical data will be required to determine if this is indeed the case.

Finally, our apo-form of tuberculin PPAT may have important implications when considering the design of specific inhibitors for this essential enzyme. To date, the design of inhibitors has focused on those structurally related to its substrate Ppant (Zhao et al. 2003). However, the structure presented herein suggest an alternative approach, in which compounds designed to block the mouth of the solvent channel, which would prevent the entry of substrates, could represent powerful new tools to disable the enzyme and compromise bacterial growth and survival.

Materials and methods

PPAT purification

We obtained M. tuberculosis genomic DNA from Colorado State University, and subcloned the 483 bp ORF of PPAT into the pET3a (Novagen) expression vector. The final construct contained an additional Glu residue that preceded the PPAT sequence. Tuberculin PPAT was purified essentially as described for the coliform enzyme (Geerlof et al. 1999). Briefly, the protein was expressed in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3) and induced with 1 mM IPTG (4 h, 37°C). Cell pellets were frozen at −20°C. Upon thawing, cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 0.5 mM PMSF. Cell debris was removed by ultracentrifugation. Expressed protein was purified first using an anion-exchange column (HiLoad Q-sepharose, Amersham) over a gradient to 1 M NaCl. Following dialysis into 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, PPAT was further purified over a Red Sepharose column (Amersham) and finally by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200, Amersham). The protein was dialyzed into 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM DTT, and 150 mM NaCl, concentrated to 18 mg mL−1, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C.

Structure determination

Native M. tuberculosis PPAT crystals were grown as described (Brown et al. 2004) and belonged to space group R32 (a = 68.7 Å and α = 91.9°). The M. tuberculosis PPAT structure was solved by molecular replacement using the E. coli PPAT:dPCoA (Izard and Geerlof 1999) structure as a search model in the program AMoRe (Navaza 1990). The product dPCoA and the solvent structure were omitted from the model. An electron density map, based upon the phases from the molecular replacement solution, immediately showed the position of the entire backbone of the protein, with the majority of side chains being apparent.

Crystallographic refinement

The M. tuberculosis PPAT structure was refined using the program CNS (Brünger et al. 1998) using standard protocols. Water molecules were initially identified in Fo – Fc maps and were screened for reasonable geometry and for a refined thermal factor of < 65 Å2. Table 1 shows the overall crystallographic R-factor and the free R-factor for all observed reflections within the indicated resolution range. A Ramachandran plot analysis by the program PROCHECK (Collaborative Computational Project, No. 4 1994) indicates that 92.4% of all the residues lie in most favorable regions and the remaining 7.6% lie in additional allowed regions, and that there are no residues in the generously allowed or disallowed regions. This structure analysis also showed that all stereo-chemical parameters are better than expected at the given resolution.

Table 1.

Crystallographic refinement statistics

| Resolution range | 20–1.99 Å |

| Last shell | 2.11–1.99 Å |

| No. of reflections (working set) | 14,056 |

| No. of reflections test set | 749 |

| Number of amino acid residues | 157 |

| Number of protein atoms | 1201 |

| Number of solvent molecules | 132 |

| R-factor (overall)a | 0.229 |

| R-factor (2.11–1.99 Å)a | 0.289 |

| Rfree (overall)b | 0.258 |

| Rfree (2.11–1.99 Å)b | 0.320 |

| Average main-chain B-factor (Å2) | 218.8 |

| Average side-chain B-factor (Å2) | 30.3 |

| Average water molecule B-factor (Å2) | 39.4 |

| RMSD from ideal geometry | |

| Covalent bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.2 |

aR-factor = ∑hkl ||Fobs|−|Fcale||/∑hkl|Fobs|

b The free R-factor is a crossvalidation residual calculated by using 5% of the native data, which were randomly chosen and excluded from the refinement.

Protein Data Bank accession code

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 1tfu.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Philippe Bois for preparing the tuberculin PPAT expression construct. We are grateful to John Cleveland for helpful discussions and for critical review of the manuscript. We thank Charles Ross for maintaining the X-ray and computing facilities, and the Hauptman-Woodward Institute (Buffalo, NY) for defining the initial crystallization conditions. The authors are members of the TB Structural Genomics Consortium (http://www.tbgenomics.org). This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant AI55894, the Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant CA21765, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.04816904.

References

- Aghajanian, S. and Worrall, D.M. 2002. Identification and characterization of the gene encoding the human phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase and dephospho-CoA kinase bifunctional enzyme (CoA synthase). Biochem. J. 365 13–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley, T.P., Kinsland, C., and Strauss, E. 2001. The biosynthesis of coenzyme A in bacteria. Vitam. Horm. 61 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.L., Morris, V.K., and Izard, T. 2004. Rhombohedral crystals of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase. Acta Crystallogr. D60 195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., Delano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, N., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, No. 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D50 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty, M., Polanuyer, B., Farrell, M., Scholle, M., Lykidis, A., de Crecy-Lagard, V., and Osterman, A. 2002. Complete reconstitution of the human coenzyme A biosynthetic pathway via comparative Genomics. J. Biol. Chem. 277 21431–21439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First, E.A. and Fersht, A.R. 1993. Involvement of threonine 234 in catalysis of tyrosyl adenylate formation by tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 32 13644–13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerlof, A., Lewendon, A., and Shaw, W.V. 1999. Purification and characterization of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274 27105–27111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard, T. 2002. The crystal structures of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase with bound substrates reveal the enzyme’s catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 315 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2003. A novel adenylate binding site confers phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase interactions with coenzyme A. J. Bacteriol. 185 4074–4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard, T. and Geerlof, A. 1999. The crystal structure of a novel bacterial adenylyltransferase reveals half of sites reactivity. EMBO J. 18 2021–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowski, S. and Rock, C.O. 1984. Metabolism of 4′-phosphopantetheine in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 158 115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona, J.J., Rould, M., and Steitz, T.A. 1993. Structural basis for transfer RNA aminoacylation by Escherichia coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 32 8758–8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robishaw, J.D. and Neely, J.R. 1985. Coenzyme A metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. 248 E1–E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti, C.M., Boyd, D.H., and Rubin, E.J. 2003. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, E., Meinnel, T., Blanquet, S., and Mechulam. Y. 1994. Methionyl-tRNA synthetase needs an intact and mobile 332KMSKS336 motif in catalysis of methionyl adenylate formation. J. Mol. Biol. 242 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H., Inagaki, E., Fujimoto, Y., Kuroishi, C., Nodake, Y., Nakamura, Y., Arisaka, F., Yutani, K., Kuramitsu, S., Yokoyama, S., et al. 2004. Structure and implications for the thermal stability of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr. D60 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L., Allanson, N.M., Thomson, S.P., Maclean, J.K., Barker, J.J., Primrose, W.U., Tyler, P.D., and Lewendon, A. 2003. Inhibitors of phosphopantetheine adenylyltransferase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 38 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhyvoloug, A., Nemazanyy, I., Babich, A., Panasyuk, G., Pobigailo, N., Vudmaska, M., Naidenov, V., Kukharenko, O., Palchevskii, S., Savinska, L., et al. 2002. Molecular cloning of CoA Synthase. The missing link in CoA biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 277 22107–22110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]