Abstract

An altered version of peptide deformylase from Plasmodium falciparum (PfPDF), the organism that causes the most devastating form of malaria, has been cocrystallized with a synthesized inhibitor that has submicromolar affinity for its target protein. The structure is solved at 2.2 Å resolution, an improvement over the 2.8 Å resolution achieved during the structural determination of unliganded PfPDF. This represents the successful outcome of modifying the protein construct in order to overcome adverse crystal contacts and other problems encountered in the study of unliganded PfPDF. Two molecules of PfPDF are found in the asymmetric unit of the current structure. The active site of each monomer of PfPDF is occupied by a proteolyzed fragment of the tripeptide-like inhibitor. Unexpectedly, each PfPDF subunit is associated with two nearly complete molecules of the inhibitor, found at a protein–protein interface. This is the first structure of a eukaryotic PDF protein, a potential drug target, in complex with a ligand.

Keywords: crystal engineering, drug design, malaria, PDF, Plasmodium

Prokaryotic protein synthesis begins with a formylmethionine residue. The resulting amino-terminal formyl group is subsequently removed by a metalloenzyme, peptide deformylase (PDF), during bacterial protein maturation. The resulting amino-terminal methionine is removed in many cases by methionine aminopeptidase, which has essentially no activity for N-formylated methionine substrates. Some proteins that fail to undergo this process of maturation are inactive. In support of this understanding, inhibitors of the first step of this process have been shown to be bacterio-static in vitro (Apfel et al. 2001b). In recent years, inhibitors of bacterial peptide deformylases have made significant pre-clinical progress as novel antibacterial agents (Apfel et al. 2001a,b; Hackbarth et al. 2002; Wise et al. 2002; Roblin and Hammerschlag 2003), including very encouraging in vivo results (Clements et al. 2001). The unexpected finding of a human mitochondrial peptide deformylase has apparently not dampened enthusiasm for this potential new class of antibacterials. The lack of reported toxicity to human and other animal cells, despite evident antibacterial action, has prompted the suggestion that the human mitochondrial PDF protein may not be functional, or that the tested inhibitors may not be reaching the mitochondrion (Nguyen et al. 2003).

Here, we focus on the peptide deformylase from a major human pathogen, a unicellular eukaryotic protozoan, Plasmodium falciparum. P. falciparum is the causative agent of the most deadly form of malaria, a disease that causes up to 2 million deaths annually, mostly of children under the age of five (WHO 2000). The P. falciparum genome was found to contain an ORF with homology to bacterial def genes that code for the peptide deformylase protein (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001). The P. falciparum peptide deformylase (PfPDF), contained a signal sequence, suggesting it would be targeted to the apicoplast, a specialized organelle found in organisms from the phylum Apicomplexa (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001). Recombinant PfPDF can be overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified, with in vitro tests confirming that this protein can function as a deformylase (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001). Initial studies with high concentrations of two antibacterial PDF inhibitors were able to suppress the in vitro growth of P. falciparum (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001; Wiesner et al. 2001). This suggests that inhibitors specifically targeting PfPDF might be promising leads for the development of new antimalarial drugs.

Recognizing the potential importance of PfPDF as a drug target, an initial crystallographic study of PfPDF was undertaken by Kumar et al. (2002), who reported a structure of PfPDF at 2.8 Å resolution. This structure determination overcame a number of vexing difficulties in protein purification, crystallization, diffraction, and phase determination. The carboxy-terminal hexahistidine-containing PfPDF used for this previous study was prone to aggregation, as evidenced by size-exclusion chromatography and dynamic light-scattering experiments (Kumar et al. 2002).

Despite these unfavorable indications, routine screening of crystallization conditions resulted in large protein crystals. The diffraction of these crystals was very weak, with most crystals diffracting to <8 Å initially. This was considerably improved by the repeated application of a flash-annealing technique (Yeh and Hol 1998). The resulting diffraction nominally extended to 2.8 Å, although with significant anisotropy along one axis (Kumar et al. 2002). The eventual solution demonstrated that the asymmetric unit contained 10 subunits of PfPDF, arranged in a complex pattern of noncrystallographic symmetry. The large number of protein molecules within the asymmetric unit, the limited resolution, and anisotropy of these initial PfPDF crystals made them far from ideal for further studies of enzyme inhibitor complexes.

Design strategy for new construct and crystallization screening

In this study, we report progress in overcoming the challenges posed by the initial Form I crystals of PfPDF. We sought to rationally modify the protein in a manner that we hypothesized might reduce the problems initially encountered. One potentially modifiable feature that we noted was that several residues at the carboxyl terminus, especially Glu 238, Pro 239, and Leu 240, participate in a network of intersubunit interfaces (Fig. 1A ▶). Examination of the B factors for these carboxy-terminal residues and the superposition of the individual subunits in the original structure led us to conclude that this peripherally positioned portion of the carboxyl terminus was less ordered than the central area of the PfPDF monomer. We hypothesized that deletion of a limited number of these residues would disrupt the network of intersubunit contacts that were necessary to form the 10-fold noncrystallographic symmetry, and lead to improved diffraction properties.

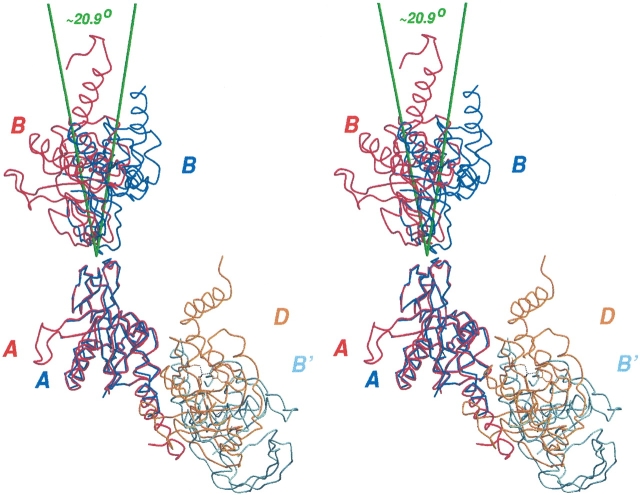

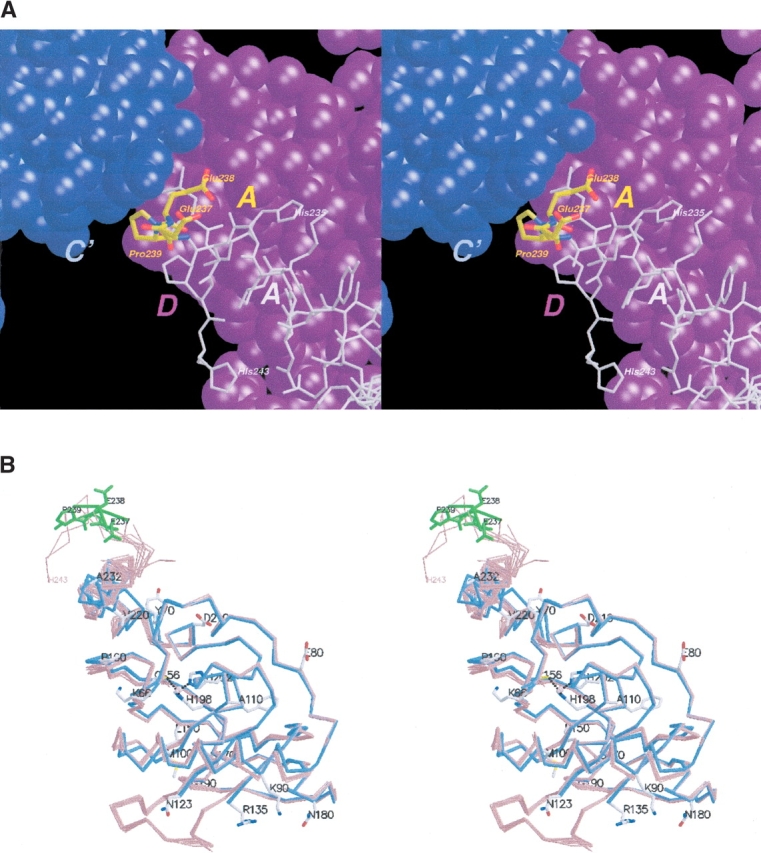

Figure 1.

(A) Ternary interface found in crystal Form I structure. Stereo view, showing carboxy-terminal residues Glu 237-Glu 238-Pro 239 (yellow) of subunit A and their position at the three-way interface among A (yellow, with remaining residues in gray), C′ (blue), and the D (magenta) subunits in the Form I crystal structure. These residues were removed in the newly designed construct used in the current study, in hopes of perturbing the undesirable noncrystallographic symmetry features found in the Form I crystals. A and B, and Figs. 2, B and C ▶, and 3 were created using MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991) and Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon 1997). (B) Superposition of PfPDF monomers in two crystal forms. Stereo view, superposition of PfPDF subunits from the current structure (blue, Form II crystals, cocrystallized with inhibitor) and previous structure (red, Form I crystals, with no active-site ligand; Kumar et al. 2002).

The actual construct used for this study differs from the one used for the Form I crystal structure in several respects. Previously, the amino-terminal 63 residues were truncated from the expression construct, as these residues contained the apicoplast-targeting signal. It was later found (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001) that a construct with an amino-terminal 57-residue truncation led to improved expression, so this modification was used in subsequent constructs. Following up on the original hypothesis that Glu 238 and Leu 240 were engaged in important intermolecular contacts resulting in the undesirable NCS and diffraction in the original structural study, a new carboxyl terminus was created (Fig. 1A ▶). In the original construct, the sequence from Ser 236 to the terminus consisted of SEEPL-EHHHHHH. This was modified to S-LEHHHHHH. In both cases, the final eight residues consisted of LEHHHHHH to accommodate the pET-29b vector that adds the carboxy-terminal hexahistidine tag to the proteins. This modified PfPDF, six residues longer at the amino terminus and three residues shorter at the carboxyl terminus, was used for the present study.

We concurrently added a recently synthesized, moderately potent PfPDF inhibitor that had an IC50 of 130 ± 26 nM against PfPDF (Nguyen et al. 2003) to our crystallization screens, in order to structurally characterize the interaction between PfPDF and ligands or inhibitors. Furthermore, the presence of a ligand, inhibitor, or product can stabilize the region of the protein near the active site and improve the diffraction properties of the crystal, which was also a prime interest of this study.

Results

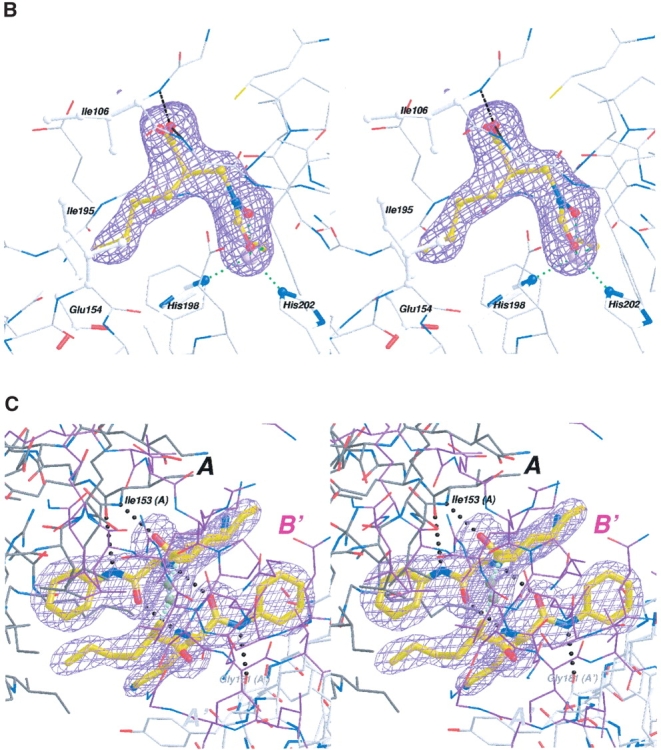

New crystallization conditions were identified for the modified PfPDF used in this study. As hoped, the resultant (Form II) crystals diffract to higher resolution (~2.2 Å versus 2.8 Å) than the former (Form I) crystals, without the severe anisotropy or complex 10-fold noncrystallographic symmetry observed in the previous study. In addition, for the first time in a eukaryotic PDF, we observe electron density for a small molecule inhibitor bound at the active site of the enzyme (Figs. 1B ▶ and 2 ▶).

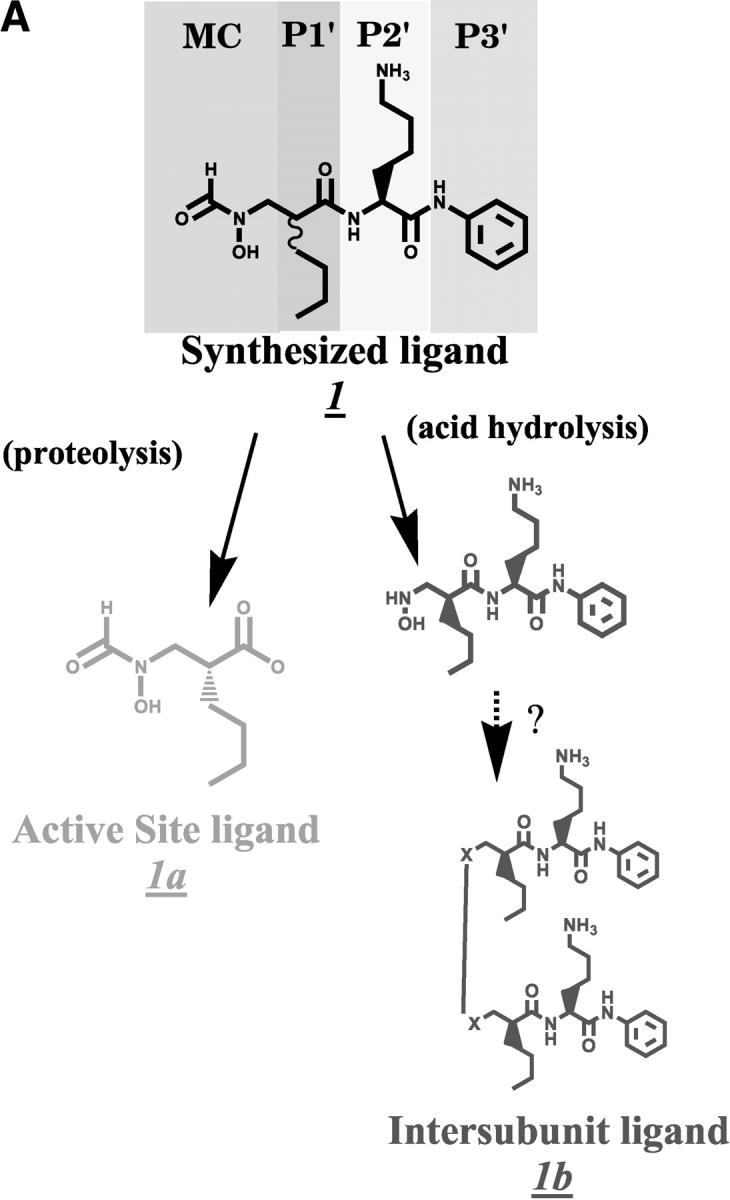

Figure 2.

(A) Chemical structures–synthesized inhibitor and the fragments found in electron density. Scheme showing the chemical structures of the synthesized inhibitor 1 and the proteolysed fragment found at the active site (1a, gold). The synthesized inhibitor can be seen as a tripeptide-like arrangement including a metal-chelating head group, a P1′ group (with an n-butyl side chain), a P2′ L-Lysine, and the P3′ group shown. The P1′ residue in the synthesized inhibitor is an ~1:1 mixture of R- and S-isomers. The large molecule at the intersubunit boundary structurally resembles a dimer of the hydrolyzed fragment (shown in 1b, green), although the nature of the linker is still uncertain, as indicated by the question marks. (B) Stereo view of the proteolysed inhibitor and electron density at the active site. The electron density shown is from a SigmaA-weighted difference Fourier omit map, contoured at 3.5 σ, with both active-site ligand atoms omitted from the model. The position of the ligand (of the A subunit) in the final model is shown. (C) Stereo view of inhibitor electron density found at the intersubunit sites. The electron density shown is from a SigmaA-weighted difference Fourier omit map, contoured at 3.5 σ, with all intersubunit inhibitor atoms omitted from the model. This electron density feature was found twice in the asymmetric unit of the crystal Form II structure, related by the noncrystallographic twofold. The relationship of one of these two intersubunit ligands to three adjacent subunits of PfPDF is depicted. Two of these are crystallographically related (shown in black A and gray A′, respectively), whereas the other represents the noncrystallographically related PfPDF monomer (shown in magenta in B). The two copies of this intersubunit ligand are quite similar, and can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d. of 0.30 Å for all 50 nonhydrogen atoms. Also shown are intraligand hydrogen bonds between the two halves of this ligand and the hydrogen bonds main-chain atoms of the A and A′. subunits

The crystal grown in the presence of PfPDF inhibitor (molecule 1, which is an ~1:1 mixture of R and S isomers at the P1′ residue, Fig. 2A ▶) has space group P65 and diffracts to 2.2 Å resolution. These crystals contain two monomers of PfPDF per asymmetric unit with a proper noncrystallographic twofold axis virtually perpendicular to the z-axis (~89.5°), whereas its projection onto the xy plane is inclined ~66.6° from the x-axis. Correction of the sequence used to trace the electron density (see Materials and Methods) led to an improved local fit to the electron density and the resolution of geometric and chemical problems in the initial model, such as unusual dihedral angles and an unusual highly (88%–100%) solvent-exposed Phe 85 side chain. In the final stages of refinement, the peptide bond of Pro 71 could be better modeled in the cis conformation rather than trans. Residues Ala 124–Glu 134 were removed from the final Type II crystal structure, as the electron density in this region of the maps was too weak to retain this disordered loop. The first residue seen in electron density was Lys 66 in both subunits present in the P65 asymmetric unit of the Type II crystal structure. The last residue seen in electron density was Asp 230 and Ala 232 in the two subunits of the model. Final eventual refinement statistics for the current Form II crystal containing bound inhibitor (Table 1) include Rwork and Rfree values of 18.9% and 22.0%, respectively. Addition of the two omitted residues and limited re-refinement of the previous crystal Form I PfPDF model improved the Rwork from 23.1% to 22.5% and Rfree from 29.6% to 27.7%. Further refinement of the crystal Form I structure was not attempted due to the limited resolution of the data and the complexities imposed by the large number of atoms in the asymmetric unit.

Table 1.

Data processing and refinement statistics

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9800 |

| Resolution (Å) | 41.6–2.18 |

| Space group | P65, a = b = 102.423Å, c = 118.345Å |

| Number of protein subunits/asymmetric unit | 2 |

| VM (Å3 Da−1) | 4.0 |

| Solvent content (%) | 70 |

| Unique reflections | 36742 |

| Total reflections | 230882 |

| Completeness | 99.9% |

| Multiplicity | 6.3 (6.3) |

| Rsym (last shell, 2.30–2.18Å) | 11.1 (71.4)a |

| I/σ (last shell, 2.30–2.18Å) | 11.4 (2.6) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution: | 20.0–2.18Å |

| Number of protein atoms | 2555, mean B value 39.6Å2 |

| Number of protein residues | 310 |

| Number of water molecules | 139, mean B value 39.1Å2 |

| Number of metal Co ions | 2, mean B value 29.0Å2 |

| Number of other atoms: | |

| Active site ligands (2) | 26, mean B value 38.8Å2 |

| Intersubunit ligands (4) | 104, mean B value 37.8Å2 |

| Number of atoms, total | 2838 |

| Rwork (last shell, 2.24 ± 2.18Å) | 0.198 (0.251) |

| Rfree (last shell, 2.24–2.18Å) | 0.214 (0.275) |

| RMS deviations from ideal geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.315 |

| Chirality | 0.098 |

| Ramachandran analysis | |

| Most favorable | 91.2% |

| Allowed | 8.8% |

| Generously allowed/disallowed | 0%/0% |

a Even though the Rsym for the outer shell is high, the redundancy in this shell is high as well, which tends to increase Rsym (Weiss 2001). The I/σ (I) is better than 2, a statistically based rationale for a cutoff (Gewirth et al. 1996). The inclusion of the data in the 2.24 to 2.18 Å shell appears to be justified by the low value of Rwork (0.251) and Rfree (0.275) in this shell.

Structure of the PfPDF monomer bound to inhibitor

Superposition of the PfPDF monomers from the current Form II crystal structure and the previous Form I structure shows the overall high similarity between the monomers (Fig. 1B ▶), with an r.m.s. deviation of between 0.53 Å and 0.64 Å for 151 Cα atoms when the Form II and Form I subunits are compared (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics for superposition of PfPDF subunits

| Superimposed residues | r.m.s. deviation Cα atoms | |

| PfPDF Form II (A vs B) | 66–123; 135–230 | 0.67Å |

| PfPDF Form II (A vs B) | 67–123; 135–212 | 0.10Å |

| PfPDF Form II (A, B) vs Form I (A–J) | 67–123; 135–212 | range: 0.53–0.64Å |

| PfPDF Form I(A) vs Form I (B–J) | 67–123; 135–212 | range: 0.28–0.35Å |

Pairwise comparison of atomic position of subunits from liganded (crystal Form II) and unliganded (crystal Form I) structures. Residues 124–134 were disordered in the Form II structure; thus, these residues are not included in any of the comparisons. Residues 67–212 are even more structurally similar than the whole subunit comparisons suggest, as shown by comparing line 1 vs. line 2 below.

Both subunits of the PfPDF:inhibitor complex contained density at the active site of the enzyme. However, only 13 of the 28 nonhydrogen atoms of the synthesized inhibitor could be modeled into this density (Fig. 2B ▶). The lack of electron density for the remaining inhibitor is likely due to unanticipated proteolytic cleavage degradation occurring during crystal growth. This would be consistent with the excellent electron density seen in both subunits for both the N-formylhydroxylamine moiety coordinated to the metal and the norleucine main chain and side chain. The abrupt absence of electron density beyond the first peptide bond between the n-butyl side chain and the lysine of 1 would also be consistent with proteolytic cleavage. Presumably, density corresponding to more inhibitor atoms likely would be detectable if the P2′ and/or P3′ inhibitor positions were disordered rather than proteolytically absent. The identification of functional groups in the active site ligand is further supported by interactions with cobalt and the anticipated network of ligand hydrogen bonding at the N-formylhydroxylamine moiety, the observed R chirality at the norleucine-like P1′ residue, the appropriate length of side chain density for the n-butyl group, and a geometry consistent with hydrogen bonding of the P1 carbonyl to the backbone amide of Ile 106 (2.8 Å). When the active-site ligand atoms are removed from the model, SigmaA (Read 1986) weighted difference Fourier omit maps contain strong electron density, shown in Figure 2B ▶, that closely matches all of these features of the resulting 2 (R)-[(formylhydroxy-amino)-methyl] hexanoic acid, (molecule 1a in Fig. 2A ▶). The active site ligands of both subunits in the form II crystal structure are very similar with an r.m.s.d. of 0.093 Å for all 13 atoms.

The S1′ site of PfPDF is the largely hydrophobic groove that interacts with the first side chain of the pseudotripeptide PDF inhibitors, which mimics the configuration of the methionine side chain of the natural substrate. The n-butyl P1′ side chain of the inhibitor approaches within 4 Å the aliphatic portions of the Ile 106, Glu 154, and His 198 side chains in both subunits of the current structure, and also Ile 195 within 4.6 Å. The closest approach between the inhibitor side-chain atoms and the protein atoms is larger than 3.5 Å, likely reflecting both the hydrophobic nature of this interaction and the somewhat smaller size of the n-butyl side chain relative to the methionine of the natural substrate.

The active site of PfPDF appears to be large enough to accomodate the entire inhibitor molecule if it were intact, as evident from the discussion by Kumar et al (2002). Using the same construct reported here, our group has crystallized PfPDF in complex with other ligands, which are bound at the active site uncleaved and in full occupancy (B.P. Ingason, B. Krumm, and W.G.J. Hol, unpubl.).

An unexpected additional ligand

An additional interesting density feature was observed in the difference Fourier electron-density maps. It is peptide like, but unlike the active-site ligand electron density, it contains a center with a D-amino acid configuration, thereby excluding the possibility that it is a part of the PfPDF protein. We suspect that the D-amino acid configuration of the P1′ group should make this inhibitor more resistant to proteolysis than the L-counterpart, which was the fragment found at the active site. The shape of this unexpected electron density accommodates two nearly complete head-to-head copies of the inhibitor molecule (Fig. 2C ▶). Structural features of the P1′, P2′, and P3′ components of the intact inhibitor correspond very well with the density in both halves of this feature. However, the remaining linking density, which continuously bridges the two halves of this density, is large enough for ~4–5 carbon, oxygen, and/ or nitrogen atoms. The linking density is thus too small to correspond to two intact copies of the metal chelating (N-formylhydroxylamine-methyl-) group, and also appears too small for two copies of the slightly smaller hydroxylamine-methyl group that would result from hydrolysis of the formyl group of the intact inhibitor. Furthermore, the linker density is morphologically most consistent with a covalent link between the two halves of this unexpected ligand. All attempts to model this as noncovalently linked molecules left implausibly large features in difference-density maps, or led to unacceptably close intermolecular contacts, essentially compelling us to consider covalent models. Although the identity of these linker atoms are unknown, a linear –CH2-NH-NH-CH2 – chain is approximately the correct size (Fig. 2C ▶). Because of the uncertainty pertaining to the linker, the model chosen for the linker should be considered as exploratory and provisional, rather than conclusive. Unfortunately, no remaining crystals or inhibitor stock solution was available for additional physicochemical experimentation that could address this issue further.

In addition to attempts to model this density with a single covalently bonded molecule or two noncovalently linked modified ligands, we also examined the effects of interpreting this density as two half-occupancy molecules of the intact inhibitor. However, the mean temperature factors for the inhibitor, previously 37.8 Å2, become 22.4 Å2, and then demonstrate a striking difference from the 39.6 Å2 mean temperature factor of the protein. Closer inspection of this model disclosed further implausible differences in the B factors between atoms in close contact; examples are Ile 153-N (B = 30.2 Å2) and the inhibitor’s P1′ carbonyl O (B = 9.0 Å2). We consider the low overall temperature factors and the marked disparity of these temperature factors for atoms in close contact with each other to be less plausible features of this alternative approach, and, hence, have preferred a covalent structure as proposed above.

Comparison of the PfPDF dimers in the two crystal forms

One of our goals was to engineer the crystals of PfPDF to disrupt the complex intersubunit interactions found with the original construct of PfPDF in crystal Form I (Fig. 1A ▶) by using a protein variant in which key contact residues, in this case Glu 237, Glu 238, and Pro 239, were altered. Further light can be shed on the effects of the new construct by an analysis of the differences observed in the intersubunit interfaces between the previous and current models.

In the simplest analysis, the quaternary structure between the A and B subunits (and similar relationships between the E and J subunits and G and I subunits) in the previous Form I structure and the two subunits (A and B) found in the asymmetric unit of the current Form II structure have many similarities (Fig. 3 ▶). In both cases, the two subunits are related by a comparably positioned noncrystallographic dyad. The buried surface interface between these subunits is 1192 Å2 in the Form II crystal structure and varies between 923 Å2 (A and B subunits) and 975 Å2 (G and I subunits) in the Form I crystal. All of these interfaces include a salt bridge between Lys 183 and Glu 144, and Van der Waals contacts between Ile 187 and aliphatic portions of the side chains of Leu 185 and Lys 186. Despite these clear similarities, there are small differences in this dimer interface in the two crystal structures. As a result, when the A subunits are superimposed, it can be seen that roughly a 21° rotation separates the corresponding B subunits in the two crystal forms (Fig. 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the quaternary structures, Form I vs. Form II. To compare the quarternary structure found in the form II crystal structure (blue and light blue Cα traces, A, B, B′) with that found in the form I crystal structure (red and orange Cα traces, A, B, D), we have superimposed a single subunit (A) from each structure, and show the adjacent subunits with substantial interfaces with this subunit. In form I crystals, the B and D subunits make significant contacts with the A subunit. In form II crystals, the B subunit and another, symmetry-related B′ subunit make significant contacts with the A subunit. The interface between the A and B subunits in the different crystal forms is close enough to lead to the near alignment of the Cα traces near the A:B interfaces. Nevertheless, the B subunit is distinctly displaced by a ~21° rotation relative to the other crystal form. The green lines, passing through the centroid of the corresponding upper PfPDF subunits, illustrate the differing orientations of this subunit in the two crystal forms. Unlike the similarities noted in the A:B (crystal form I) vs. A:B (crystal form II) interface shown at the top of the diagram, the contrasting Cα traces at the other major interface, the A:D (crystal form I) vs the A:B′ (crystal form II) interface, demonstrate a markedly dissimilar interface, as shown at the bottom part of the diagrams.

Figure 3 ▶ also shows the superposition of the A:D dimer of the Form I crystal structure and the A:B′ dimer found in the Form II crystal structure. It is immediately apparent that this A:B′ intersubunit interface is substantially different from the Form I crystal structure A:D dimer interface.

Structural consequences of the deletion of residues 237–239 of the Form I crystal structure

In the Form I crystal structure, a ternary AC′ D complex is formed with several carboxy-terminal residues of the A subunit wedged into a cleft formed by subunits D and C′ (Fig. 1A ▶). The tiny A–C′ interface buries ~210 Å2, with a sharp kink at Pro 239 of the A subunit, allowing a hydrophobic contact between the Pro and the His 184 side chain of the C′ subunit. Subunits B:C:D′ and E:B′:A′ also exhibit a similar ternary complex. Perturbations to the structure of the carboxy-terminal tail at these positions likely have disturbed the fragile contacts at this critical nexus of intersubunit interactions in Form I crystals. With the first histidine of the hexahistidine tag shifted into the sequence position occupied previously by the Pro 239 residue, the A–C′ interface is no longer formed, as the bulkier histidine side chain would lead to a steric clash between the imidazole side chains of residue 239 in the engineered PfPDF and would clash with the His 184 side chain of the C′ subunit in crystal Form I. Interfering with the formation of the tiny A:C′ interface has resulted in (1) the formation of slightly different AB dimers (Fig. 3 ▶), and (2) to an entirely different arrangement of these dimers in the new Form II crystal lattice. By perturbing a small intersubunit interface, we have achieved our goal of finding a new crystal form of PfPDF that does not contain that interface. As hoped, this has led to improved diffraction and an elimination of the unfavorable noncrystallographic symmetry seen in the initial Form I crystal structure. In addition, we obtained the first view of a ligand in the active site of P falciparum PDF.

Materials and methods

The full-length PfPDF coding sequence was cloned into pET29b (Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2001). The amino and carboxyl terminus truncations were performed by PCR using primers 5′-GGGGATC CATATGTCAAAAAATGAAAAGGATGAGATAAAA-3′ and 5′-GGGGCTCGAGTGAGTGAGTAGCCTTATAATCCCTAATTA G-3′ and plasmid pET29bPfPDF as the template. The PCR product was digested with restriction endonucleases NdeI and XhoI, and cloned into pET22b (Novagen). The resulting construct pET22b-NΔ57PfPDF CΔ234 was used for generating the PfPDF variant carboxy-terminal histidine tag, with truncations of the first amino-terminal 57 amino acid residues and carboxyl terminus to amino acid residue S234. Protein expression was carried out in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells grown in minimal media containing 60 μg/mL kanamycin at 37°C. Induction of protein expression for the Co(II) substituted PfPDF variant was done with 100 μM IPTG at 30°C for 6 h in the presence of 100 μM of CoCl2. The protein was purified by cation exchange chromatography (SP-sepharose, Pharmacia) and followed by Talon [Cobalt(II)-NTA] affinity column chromatography (Clontech). The purified protein was dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl( pH 7.0 buffer).

The purified modified PfPDF, in a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES (pH 6.0), 10 mM NaCl, was concentrated to 6.8 mg/mL and screened for cocrystallization conditions in sitting drop vapor diffusion trays with the supplied inhibitor added to a final concentration of 3.6 mM, using 2 + 2 mL drops over a 0.5-mL reservoir. This first attempt to cocrystallize PfPDF in the presence of ligand 1 (Fig. 2 ▶) utilized an ~1:1 mixture of the R,S stereochemistry, analogous to D-Nle and L-Nle, respectively, at the first chiral center containing the n-butyl side chain, whereas the other chiral center was solely the S-isomer (L-Lys). The final step of the synthesis of the inhibitor mixture involved the addition of trifluoro-acetic acid (TFA). Subsequent experience with other recently synthesized inhibitors has occasionally led to loss of the formyl group of the inhibitor, likely due to TFA-catalyzed hydrolysis.

A single rod-like crystal was identified in a well containing 1.2 M NaH2PO4, 0.8 M K2HPO4, 0.2 M Li2SO4, and 0.1 M CAPS with an actual pH of 6.1. Attempts to repeat and/or optimize these crystallization conditions were not successful. Fourteen weeks after the initial preparation of the crystallization tray, the only crystal obtained was broken into several large shards during the transfer of the crystal to cryoprotection solution consisting of mother liquor supplemented with 30% PEG 200. The supply of the inhibitor had been exhausted in attempts to find and optimize crystallization conditions, and thus, no inhibitor was added to the cryoprotection solution.

Molecular replacement with the program MOLREP (Vagin and Teplyakov 1997) using a carboxy-terminally truncated single subunit of the model from Kumar et al. (2002), without accompanying waters or metal ion, yielded a solution with two subunits per asymmetric unit in space group P65, resulting in a VM of 4.0 Å3 /Da and a solvent content of ~70%. Density modification, including solvent flattening and twofold NCS averaging using DM (Cowtan and Main 1998) yielded an excellent map. Electron density and anomalous density confirmed the presence of a cobalt ion at the metal-binding site of PfPDF. REFMAC5 (Murshodov et al. 1997) was used for the refinement of the initial model. Inspection of the difference maps during the course of refinement disclosed density for residues Glu 81 and Pro 160. Consultation of the sequence found on PlasmoDB (Bahl et al. 2003) revealed that these residues were inadvertently missing from the sequence used for tracing the original PfPDF model.

Omission of the ligand atoms was used in conjunction with the CCP4 program SIGMAA (Read 1986) to examine omit maps to further corroborate the density for the ligands.

The program MOE (MOE 2003) was used to create an initial model of the ligands. The PRODRG server (van Aalten et al. 1996) was then used to generate appropriate geometric descriptions of the ligands during refinement.

PDB deposition

The coordinates of the final model and the structure factors have been submitted to the PDB (pdb code = 1RL4). Revised coordinates for the structure from Form 1 crystals (1JYM), using the corrected sequence information, have also been submitted to the PDB code = 1RQC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christophe Verlinde for many helpful and stimulating discussions and Francis Athappilly for his dedication to maintaining our computer environment. We also thank the staff of the beamline 5.0.2 at Advanced Light Source for their kind support. This work was supported in part by a grant from the NIH (AI40575 to D.P.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03456404.

References

- Apfel, C.M., Evers, S., Hubschwerlen, C., Pirson, W., Page, M.G., and Keck, W. 2001a. Peptide deformylase as an antibacterial drug target: Assays for detection of its inhibition in Escherichia coli cell homogenates and intact cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 1053–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfel, C.M., Locher, H., Evers, S., Takacs, B., Hubschwerlen, C., Pirson, W., Page, M. G., and Keck, W. 2001b. Peptide deformylase as an antibacterial drug target: Target validation and resistance development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 1058–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, A., Brunk, B., Crabtree, J., Fraunholz, M.J., Gajria, B., Grant, G.R., Ginsburg, H., Gupta, D., Kissinger, J.C., Labo, P., et al. 2003. PlasmoDB: The Plasmodium genome resource. A database integrating experimental and computational data. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 212–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracchi-Ricard, V., Nguyen, K.T., Zhou, Y., Rajagopalan, P.T., Chakrabarti, D., and Pei, D. 2001. Characterization of an eukaryotic peptide deformylase from Plasmodium falciparum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 396 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.M., Beckett, R.P., Brown, A., Catlin, G., Lobell, M., Palan, S., Thomas, W., Whittaker, M., Wood, S., Salama, S., et al. 2001. Antibiotic activity and characterization of BB-3497, a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan, K. and Main, P. 1998. Miscellaneous algorithms for density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirth, D., Otwinowski, Z., and Majewski, W. 1996. The HKL2000 manual, 5th ed. Yale University, New Haven, CT.

- Hackbarth, C.J., Chen, D.Z., Lewis, J.G., Clark, K., Mangold, J.B., Cramer, J.A., Margolis, P.S., Wang, W., Koehn, J., Wu, C., et al. 2002. N-alkyl urea hydroxamic acids as a new class of peptide deformylase inhibitors with antibacterial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 2752–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. Molscript—A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Nguyen, K.T., Srivathsan, S., Ornstein, B., Turley, S., Hirsh, I., Pei, D., and Hol, W.G. 2002. Crystals of peptide deformylase from Plasmodium falciparum reveal critical characteristics of the active site for drug design. Structure 10 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, E.A. and Bacon, D.J. 1997. Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Macromol. Crystal. Pt B 277 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOE (The Molecular Operating Environment) Version 2003.02. Software. Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, Canada. http://www.chemcomp.com.

- Murshudov, G.N., Vagin, A.A., and Dodson, E.J. 1997. Refinement of macro-molecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D 53 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.T., Hu, X., Colton, C., Chakrabarti, R., Zhu, M.X., and Pei, D. 2003. Characterization of a human peptide deformylase: Implications for antibacterial drug design. Biochemistry 42 9952–9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read, R.J. 1986. Improved Fourier coefficients for maps using phases from partial structures with errors. Acta Crystallogr. A 42 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Roblin, P.M. and Hammerschlag, M.R. 2003. In vitro activity of a new antibiotic, NVP-PDF386 (VRC4887), against Chlamydia pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 1447–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin, A. and Teplyakov, A. 1997. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 30 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- van Aalten, D.M., Bywater, R., Findlay, J.B., Hendlich, M., Hooft, R.W., and Vriend, G. 1996. PRODRG, a program for generating molecular topologies and unique molecular descriptors from coordinates of small molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 10 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.S. 2001. Global indicators of X-ray data quality. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 34 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Expert Committee on Malaria. 2000. World Health Organ Tech. Rep. Ser. 892. [PubMed]

- Wiesner, J., Sanderbrand, S., Altincicek, B., Beck, E., and Jomaa, H. 2001. Seeking new targets for antiparasitic agents. Trends Parasitol. 17 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise, R., Andrews, J.M., and Ashby, J. 2002. In vitro activities of peptide deformylase inhibitors against gram-positive pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 1117–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, J.I. and Hol, W.G. 1998. A flash-annealing technique to improve diffraction limits and lower mosaicity in crystals of glycerol kinase. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 479–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]