Abstract

We report molecular dynamics calculations of neuraminidase in complex with an inhibitor, 4-amino-2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid (N-DANA), with subsequent free energy analysis of binding by using a combined molecular mechanics/continuum solvent model approach. A dynamical model of the complex containing an ionized Glu119 amino acid residue is found to be consistent with experimental data. Computational analysis indicates a major van der Waals component to the inhibitor-neuraminidase binding free energy. Based on the N-DANA/neuraminidase molecular dynamics trajectory, a perturbation methodology was used to predict the binding affinity of related neuraminidase inhibitors by using a force field/Poisson-Boltzmann potential. This approach, incorporating conformational search/local minimization schemes with distance-dependent dielectric or generalized Born solvent models, correctly identifies the most potent neuraminidase inhibitor. Mutation of the key ligand four-substituent to a hydrogen atom indicates no favorable binding free energy contribution of a hydroxyl group; conversely, cationic substituents form favorable electrostatic interactions with neuraminidase. Prospects for further development of the method as an analysis and rational design tool are discussed.

Keywords: inhibitors of influenza neuraminidase, molecular dynamics, computational analysis of binding free energy, continuum solvent models, perturbation methodology

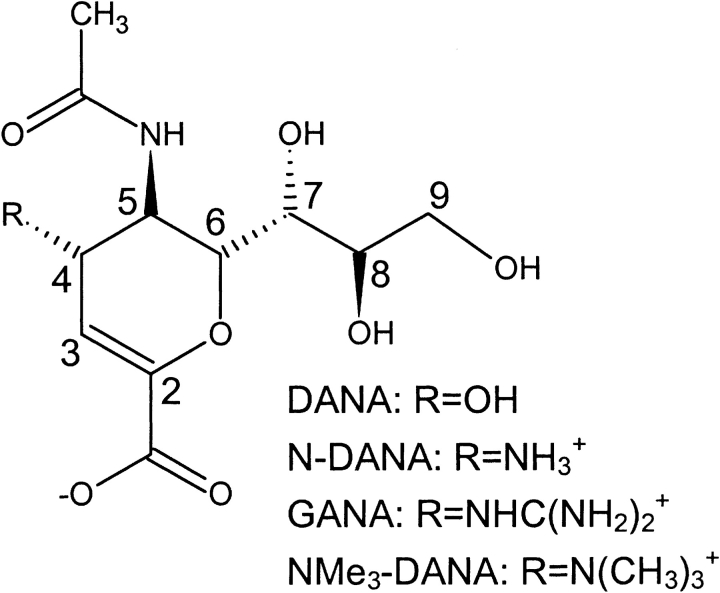

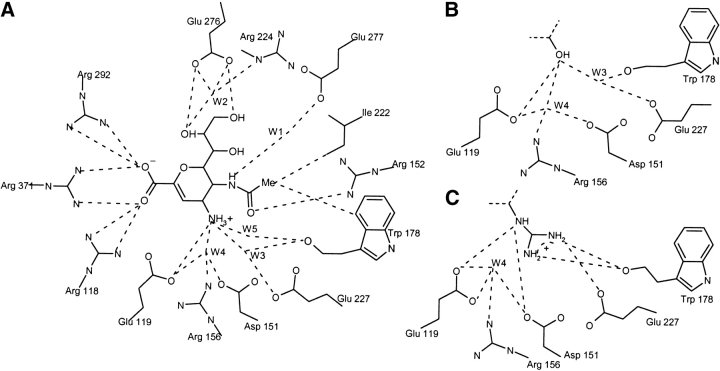

Neuraminidase, a membrane-bound glycoprotein on the surface of influenza virus particles, cleaves terminal sialic acid residues from cell-surface glycoconjugates to enable the budding of progeny virion from infected cell surfaces. The crystal structure of the globular head domain of neuraminidase in complex with its natural inhibitor, 2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid (DANA; Fig. 1▶) highlights a number of key amino acid residues (Fig. 2▶), including an arginine triad (Arg118, Arg292, and Arg371) that forms a salt-bridge with the ligand carboxylate group. The four-hydroxyl group of DANA interacts with Glu119; however, computational analysis has indicated potential for favorable interactions with further acidic residues Asp151 and Glu227. Substitution of the 4-hydroxyl of DANA with an amino group (N-DANA in Fig. 1▶) leads to improved binding affinity (Ki), from 4 μM to 40 nM (Holzer et al. 1993). Subsequent replacement of the four-amino group with a guanidino functionality gives the tight binding 1 nM zanamivir inhibitor (GANA in Fig. 1▶). The corresponding crystal structures indicate conservation of overall binding mode, although new polar interactions are forged at the four-position (Fig. 2▶). A recent computational study of N-DANA/neuraminidase (Smith et al. 2001) has questioned the protonation state of Glu119, modeling the residue in its neutral tautomer prior to calculation of the energy-minimized protein–ligand binding affinity via a continuum electrostatics treatment (Gilson and Honig 1988).

Figure 1.

Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors.

Figure 2.

(A) Direct and water-mediated crystallographic interactions between neuraminidase and N-DANA. (B) Crystallographic interactions at four-position of DANA with neuraminidase. (C) Crystallographic interactions at four-position of GANA with neuraminidase.

An alternative approach to calculation of binding affinity incorporates the effects of thermal averaging via postprocessing of an ensemble of protein–ligand configurations with a force field/continuum model potential. These combined molecular mechanics (MM)/continuum model approaches typically use Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) or generalized Born (GB) solvent, and are commonly denoted as MM-PB/SA or MM-GB/SA methods, respectively. In addition to being more computationally expedient than are traditional statistical perturbation free energy calculations (Jorgensen 1989), these methods have proved unexpectedly versatile: For example, the approach has achieved success in rationalizing nucleic acid structure (Srinivasan et al. 1998), including sequence-dependent solvation of DNA helices (Cheatham et al. 1998), RNA–protein interactions (Lee et al. 2000), protein folding (Reyes and Kollman 2000), carbohydrate–lectin (Bryce et al. 2001), and other ligand–protein interactions (S. Hou et al. 2002; T. Hou et al. 2002). In its simplest form, the MM/continuum model method evaluates the receptor-ligand binding free energy from energetic analysis of a single simulation of the explicitly solvated ligand–protein complex. However, it is possible to introduce further efficiency via perturbation of the molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory, exploring the energetic consequences of structural variation of ligand or protein. For example, a “fluorine-scanning” approach was successfully adopted to explore biotin-avidin interactions (Kuhn and Kollman 2000a,b). In this study, key ligand hydrogen atoms were replaced with fluorine for sampled configurations along the biotin–avidin trajectory, and the binding free energy was re-evaluated via the hybrid MM/continuum model potential. Structurally larger perturbations have been considered using this approach, qualitatively for analysis of HIV protease inhibitors (Kalra et al. 2002) and quantitatively for matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (Donini and Kollman 2000). Calculation of neuraminidase inhibitor binding free energies presents a challenge to a perturbative MM/continuum model approach. Substitution of a charged guanidino moiety for a hydroxyl group at C4 in DANA (Fig. 1▶) leads a 104-fold increase in Ki (Holzer et al. 1993) as several new polar contacts are made. Therefore, reoptimization of local amino acid–ligand interactions must be considered.

The aim of this study, therefore, is in the first instance to construct an experimentally validated dynamical model of N-DANA/neuraminidase complex, before proceeding to analysis of energy contributions to affinity of the complex via the combined MM/continuum model approach. We then explore the ability of a perturbative MM/continuum model strategy to rank a series of DANA-based inhibitors of neuraminidase, based on the N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory. To enable this, we extend the method by introduction of a conformational search of perturbed functional group rotamers, with energy minimization of ligand and enzyme environment in the presence of a solvent dielectric. Optimization schemes using distance-dependent dielectric (DDD) and GB solvent models are evaluated. The energetics of the ensemble of configurations are subsequently evaluated using a combined MM/PB potential. We also use the perturbative approach to obtain estimates of group contributions to binding affinity, via perturbation of inhibitor four-substituents to hydrogen atoms. Thus, we seek to evaluate a perturbed MM/continuum model method as an efficient route to calculation and analysis of multiple ligand-receptor binding free energies.

Results and Discussion

Molecular dynamics

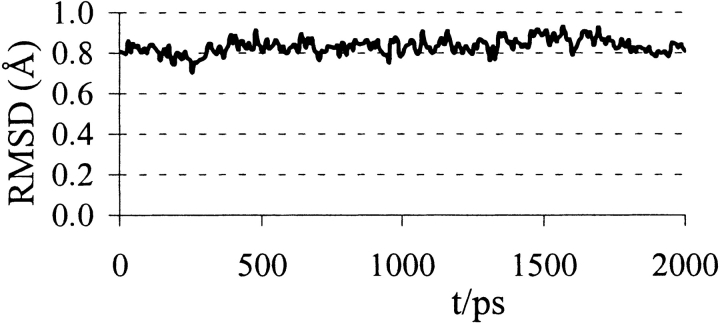

Over the 2-nsec MD trajectory of neuraminidase/N-DANA complex, a protein conformation close to the crystal structure is preserved with a converged backbone RMSD of ~0.8 Å (Figs. 3▶, 4▶). The simulation samples the direct and water-mediated ligand–protein polar contacts observed from crystallography (Tables 1▶, 2▶). Key average protein–ligand distances (Table 1▶) differ from experiment by a mean unsigned error (MUE) of only 0.27 Å. Further information is provided by analysis of hydrogen bonds, taken as donor–acceptor heavy-atom distance ≤4.0 Å and deviation from linearity of ≤60° (Table 1▶). High occupancies and short distances typify the hydrogen bonds formed between the arginine triad (Arg118, Arg292, and Arg371) and the carboxyl atoms of N-DANA. Similarly, atoms O8 and O9 of the glycerol chain of N-DANA (Fig. 1▶) are held by strong hydrogen bonds to Glu276, present throughout the simulation (Table 1▶). At the four-position, hydrogens of the cationic NH3+ group of N-DANA forge interactions with acidic residues Glu119 and Asp151, principally to Glu119 Oɛ1, with partially occupied hydrogen bonds with the carboxylate atoms of Asp151 (Table 1▶).

Figure 3.

Protein root mean square deviation (Å) from crystal structure during the simulations of the neuraminidase/N-DANA complex.

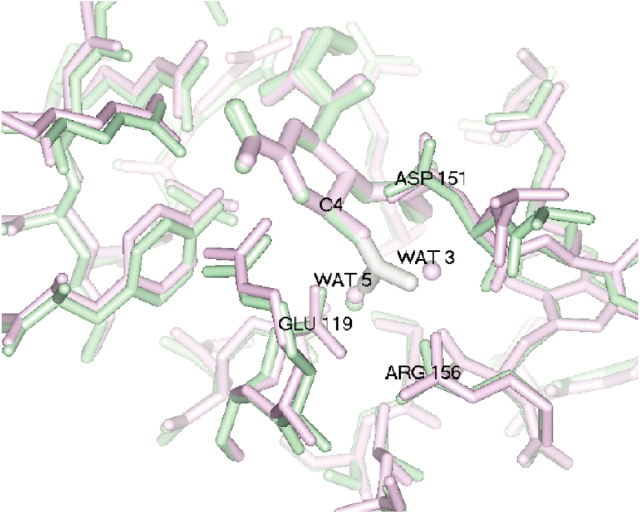

Figure 4.

Superposition of MD average (green) and crystal structure (purple) of N-DANA/neuraminidase, and superposition of guanidino group of GANA (white) with waters W3 and W5 of N-DANA.

Table 1.

Average distances (Å) between ligand and protein atoms

| Ligand | Protein | RMD | RHB | %occ | RXRD | RDDD | RGB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-NH3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ1 | 2.88 (0.14) | 2.88 (0.13) | 98.4 | 2.96 | 2.70 | 2.80 |

| 4-NH3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ2 | 3.97 (0.32) | 3.70 (0.17) | 49.2 | 4.26 | 4.29 | 4.15 |

| 4-NH3+ N | Asp151 Oδ1 | 3.84 (1.11) | 3.06 (0.32) | 61.9 | 4.36 | 3.67 | 3.96 |

| 4-NH3+ N | Asp151 Oδ2 | 3.67 (0.87) | 3.15 (0.31) | 69.0 | 2.75 | 2.90 | 3.53 |

| carboxyl O1 | Arg118 Nη1 | 3.89 (0.52) | 3.61 (0.23) | 70.6 | 3.32 | 3.73 | 3.87 |

| carboxyl O1 | Arg118 Nη2 | 3.01 (0.45) | 2.89 (0.18) | 83.3 | 2.72 | 3.00 | 3.13 |

| carboxyl O1 | Arg371 Nη1 | 3.43 (0.22) | 3.43 (0.22) | 100.0 | 3.52 | 3.44 | 3.38 |

| carboxyl O1 | Arg371 Nη2 | 2.87 (0.12) | 2.87 (0.12) | 100.0 | 2.90 | 2.71 | 2.81 |

| carboxyl O2 | Arg292 Nη1 | 3.02 (0.21) | 3.04 (0.21) | 100.0 | 3.44 | 2.75 | 2.97 |

| carboxyl O2 | Arg292 Nη2 | 3.24 (0.26) | 3.22 (0.24) | 98.4 | 3.38 | 2.96 | 3.17 |

| carboxyl O2 | Arg371 Nη1 | 2.89 (0.12) | 2.88 (0.12) | 100.0 | 2.75 | 2.71 | 2.82 |

| carboxyl O2 | Arg371 Nη2 | 3.75 (0.22) | 3.70 (0.18) | 90.5 | 3.65 | 3.55 | 3.73 |

| glycerol O8 | Glu276 Oɛ1 | 2.72 (0.17) | 2.72 (0.17) | 100.0 | 2.68 | 2.38 | 2.65 |

| glycerol O8 | Glu276 Oɛ2 | 3.81 (0.38) | 3.65 (0.26) | 64.3 | 3.69 | 3.85 | 3.83 |

| glycerol O9 | Glu276 Oɛ1 | 3.20 (0.41) | 3.17 (0.38) | 97.6 | 3.46 | 2.92 | 3.16 |

| glycerol O9 | Glu276 Oɛ2 | 2.88 (0.26) | 2.86 (0.26) | 100.0 | 2.57 | 2.68 | 2.85 |

| glycerol O9 | Arg224 Nη1 | 3.60 (0.27) | 3.51 (0.24) | 54.8 | 3.96 | 3.62 | 3.57 |

| glycerol O9 | Arg224 Nɛ | 3.27 (0.24) | 3.27 (0.23) | 63.5 | 3.49 | 3.23 | 3.25 |

| N-acetyl O | Arg152 Nη2 | 3.52 (0.86) | 2.95 (0.13) | 68.3 | 2.82 | 3.02 | 3.50 |

| MUE | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

From MD simulation (RMD), when in a hydrogen bond (RHB) with percentage occupancy (%occ); and after minimization using DDD (RDDD) and GB (RGB) solvent models. Standard deviations (Å) in parentheses. Mean unsigned error (MUE) is with respect to distances in crystal structure (RXRD).

Table 2.

Average distances (in Å) of water-mediated hydrogen bonds between N-DANA and protein from simulations (RMD) and crystal structures (RXRD)

| Solute | Water | %occ | RHB | RXRD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu 227 Oɛ1 | W1 | 100.0 | 2.70 | (0.11) | 2.66 |

| Glu 277 Oɛ2 | W1 | 99.2 | 2.66 | (0.11) | 2.81 |

| N-acetyl N | W1 | 100.0 | 2.91 | (0.13) | 2.85 |

| Arg 224 Nɛ | W2 | 65.9 | 3.54 | (0.25) | 3.58 |

| Glu 276 Oɛ1 | W2 | 38.1 | 3.65 | (0.25) | 3.89 |

| Glu 277 Oɛ2 | W2 | 38.9 | 3.05 | (0.51) | 3.54 |

| glycerol O5 | W2 | 42.0 | 2.97 | (0.26) | 2.92 |

| Glu 227 Oɛ1 | W3 | 22.2 | 3.66 | (0.27) | 3.65 |

| Glu 227 Oɛ2 | W3 | 53.2 | 2.75 | (0.16) | 2.72 |

| N-acetyl N | W3 | 40.5 | 3.21 | (0.21) | 3.42 |

| 4-NH3N | W3 | 95.2 | 3.08 | (0.24) | 2.94 |

| Trp 178 O | W3 | 48.4 | 2.79 | (0.17) | 3.17 |

| Glu 119 Oɛ1 | W4 | 50.8 | 3.30 | (0.33) | 3.38 |

| Glu 119 Oɛ2 | W4 | 52.4 | 2.74 | (0.19) | 2.66 |

| Arg 156 Nη1 | W4 | 25.4 | 3.64 | (0.24) | 3.05 |

| Arg 118 Nη2 | W4 | 39.7 | 3.50 | (0.31) | 4.07 |

| Asp 151 Oδ2 | W4 | 42.4 | 2.71 | (0.22) | 2.68 |

| 4-NH3N | W4 | 36.5 | 3.76 | (0.20) | 3.61 |

| 4-NH3N | W5 | 27.0 | 3.00 | (0.20) | 2.75 |

Standard deviations (Å) in parentheses and occupancy (%occ) are shown. Distances to N-DANA are in bold.

Smith et al. (2001) have performed a crystallographic and computational study of DANA and N-DANA complexed to neuraminidase, using energy minimization calculations by using the CVFF potential (Dauber-Osguthorpe et al. 1988). Based on energetics and hydrogen-bond distance, they suggested that the carboxyl side chain of Glu119 is protonated in the N-DANA/neuraminidase complex. At the resolution of the crystal structure (1.7 Å), the ionization state of the residue cannot be determined directly, although an environment of proximal arginines (Arg118 and Arg156) and the cationic ammonium substituent of N-DANA strongly suggest Glu119 is ionized. In this study using the AMBER force field (Wang et al. 2000), we find anionic Glu119 has an average Oɛ1…N N-DANA distance of 2.88 Å over the trajectory, in reasonable agreement with an experimental value of 2.96 Å (Table 1▶; Fig. 4▶). The MD value is larger than the corresponding distance of 2.69 Å found from the energy-minimized structure of Smith et al. (2001). We also perform energy minimization of the crystal structure of N-DANA/neuraminidase in explicit solvent by using the AMBER force field, and obtain a shortened distance of 2.82 Å. However, these minimized distances lie within the calculated standard deviation of the MD value (Table 1▶). The crystallographic value is also within 1 SD of the MD distance, indicating that this model is structurally consistent with experiment, and thus, it is difficult to distinguish ionization state based on small differences in bond length in light of thermal fluctuations of interatomic separations.

In addition to direct interactions with neuraminidase, the N-DANA ligand also samples a number of water-mediated interactions with the protein (Fig. 2A▶; Table 2▶). Hydrogen-bond distances for a number of crystallographically resolved active site waters generally show high occupancy over the simulation time scale (Table 2▶). In particular, water W1 is fully resident over the entire trajectory, with an average hydrogen-bond distance of 2.91 Å, in good agreement with a crystallographic distance of 2.85 Å. At the four-position of the ligand ring, the NH3+ substituent interacts with a number of amino acid residues via three sites, labeled W3, W4, and W5 (Fig. 2A▶; Table 2▶). Waters W3 and W5 occupy locations in the acidic pocket, corresponding closely to their crystallographic position and to the experimentally determined location of the terminal N atoms of the gua-nidino moiety of GANA (Fig. 4▶).

In summary, with Glu119 modeled in its ionized state, the inhibitor–protein trajectory demonstrates a stable protein conformation, a low root mean square deviation (RMSD) with respect to the crystal geometry, and interaction distances in good agreement with experiment. Direct and water-mediated inhibitor–protein contacts observed from static X-ray structures are highly occupied. Based upon this MD ensemble, we proceed to thermodynamic analysis of inhibitor binding to neuraminidase.

Energetic analysis of binding

Energetic postprocessing via the MM-PB/SA potential over an ensemble of structures drawn from the N-DANA inhibitor/neuraminidase trajectory determines an absolute binding free energy for the complex of -15.1 kcal/mole, before inclusion of a solute entropy contribution (Table 3▶). Calculation of the solute  term is considered problematic and time-consuming (Cheatham et al. 1998; Kuhn and Kollman 2000a) and has been omitted from preceding computational studies of neuraminidase inhibitor binding (Jedrzejas et al. 1995; Taylor and von Itzstein 1996; Wall et al. 1999; Smith et al. 2001). Inclusion of a solute vibrational

term is considered problematic and time-consuming (Cheatham et al. 1998; Kuhn and Kollman 2000a) and has been omitted from preceding computational studies of neuraminidase inhibitor binding (Jedrzejas et al. 1995; Taylor and von Itzstein 1996; Wall et al. 1999; Smith et al. 2001). Inclusion of a solute vibrational  component of 10.0 kcal/mole calculated here gives an overall

component of 10.0 kcal/mole calculated here gives an overall  of −5.1 kcal/mole. Thus, the absolute binding free energy is underestimated relative to the experimental value of −10.2 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). As we expect this contribution to be comparable for the similarsized inhibitors considered here, and to facilitate comparison with other neuraminidase studies, the solute entropy contribution to binding is omitted from further discussion. A second assumption made in calculation of

of −5.1 kcal/mole. Thus, the absolute binding free energy is underestimated relative to the experimental value of −10.2 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). As we expect this contribution to be comparable for the similarsized inhibitors considered here, and to facilitate comparison with other neuraminidase studies, the solute entropy contribution to binding is omitted from further discussion. A second assumption made in calculation of  is neglect of internal energy change of inhibitor and protein upon complex formation, by use of a single MD simulation to generate the geometries of bound and unbound protein and ligand species.

is neglect of internal energy change of inhibitor and protein upon complex formation, by use of a single MD simulation to generate the geometries of bound and unbound protein and ligand species.

Table 3.

Total calculated binding free energies and components for N-DANA (kcal/mole)

| Model |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-DANA | −183.3 (16.2) | −26.5 (2.9) | 199.3 (17.6) | −4.4 (0.1) | −89.6 (4.8) | −15.1 (5.9) |

| N-DANA (GB) | −183.3 (16.2) | −26.5 (2.9) | 167.3 (14.2) | −4.7 (0.1) | −75.7 (5.1) | −47.2 (3.6) |

| N-DANA (XR) | −179.1 | −26.2 | 187.9 | −4.4 | −88.6 | −21.9 |

Ensemble averaged MM/PB (bold) and MM/GB models; single-conformation MM/PB calculation based on X-ray crystal structure (XR). Standard deviations are in parentheses.

Table 4.

Total free energies of binding, using MM/PB potential (this work), for neuraminidase inhibitors (kcal/mole), and comparison with other studies

| Method | N-DANA | GANA | DANA | NMe3-DANA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This worka | −21.9 | — | — | — |

| This workb | −15.1 | — | — | — |

| This work (DDD)c | −35.1 | −41.9 | −2.8 | −38.2 |

| This work (GB)d | −22.9 | −29.8 | 19.7 | −23.9 |

| Taylor and von Itzsteine | −10 | −13 | 1 | 2 |

| Taylor and von Itzsteinf | −20 | −21 | −13 | −7 |

| Smith et alg | −20.1 | — | 7.0 | — |

| Smith et al.h | −12.7 | — | −3.0 | — |

| Jedrzejas et al. | — | — | −8.6 | — |

| Wall et al.j | −11.2 | −10.6 | −10.1 | −6.2 |

| Experimentk | −10.2 | −12.4 | −7.4 | −6.9 |

a Single X-ray conformation calculation.

b Ensemble-averaged calculation without structural relaxation.

c Ensemble-averaged calculation with structural relaxation using DDD solvent model.

d Ensemble-averaged calculation with structural relaxation using GB solvent model.

e Multiple-conformation calculation (Taylor and von Itzstein 1996).

f Single (lowest energy) conformation calculation (Taylor and von Itzstein 1996).

g Charged Glu119 side-chain; single conformation (Smith et al. 2001).

h Neutral Glu119 side-chain; single conformation (Smith et al. 2001).

j Using ΔGbind = 0.122 〈ΔEelec〉 + 0.472 〈ΔEvdw〉+ 2.603 kcal/mole. Simulations were performed at 310 K (Wall et al. 1999).

k Expressed at 300 K (Holzer et al., 1993).

Incorporating these approximations, an ensemble-averaged binding free energy of −15.1 kcal/mole for N-DANA is obtained, in reasonable agreement with a calculated  of −21.9 kcal/mole based on the crystal structure energy-minimized in explicit solvent (Tables 3▶, 4▶). Inspection of energetic contributions to

of −21.9 kcal/mole based on the crystal structure energy-minimized in explicit solvent (Tables 3▶, 4▶). Inspection of energetic contributions to  for ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations is informative (Table 3▶), indicating cancellation of a large favorable electrostatic protein–ligand interaction energy with an unfavorable polar desolvation contribution. As the unfavorable change in electrostatics of solvation is incompletely compensated by the Coulombic N-DANA/neuraminidase interaction, net positive electrostatic components (

for ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations is informative (Table 3▶), indicating cancellation of a large favorable electrostatic protein–ligand interaction energy with an unfavorable polar desolvation contribution. As the unfavorable change in electrostatics of solvation is incompletely compensated by the Coulombic N-DANA/neuraminidase interaction, net positive electrostatic components ( ) of 16.0 and 8.8 kcal/mole are obtained for ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations, respectively. Consequently, van der Waals forces make an important contribution here to binding: For ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations,

) of 16.0 and 8.8 kcal/mole are obtained for ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations, respectively. Consequently, van der Waals forces make an important contribution here to binding: For ensemble-averaged and single conformation calculations,  is −26.5 kcal/mole and −26.2 kcal/mole, respectively (Table 3▶).

is −26.5 kcal/mole and −26.2 kcal/mole, respectively (Table 3▶).

To evaluate the contribution of the ligand 4-NH3+ substituent to overall binding affinity, the group is mutated to a H atom for each configuration of the ligand/neuraminidase ensemble and  reevaluated for the consequent 4-H analog of DANA (H-DANA) by using the MM/continuum model approach (Table 5▶). A favorable net contribution of the ammonium group of -40.1 kcal/mole is obtained; this appears to be mainly electrostatic with no stabilizing contribution from van der Waals interactions. The net favorable contribution to

reevaluated for the consequent 4-H analog of DANA (H-DANA) by using the MM/continuum model approach (Table 5▶). A favorable net contribution of the ammonium group of -40.1 kcal/mole is obtained; this appears to be mainly electrostatic with no stabilizing contribution from van der Waals interactions. The net favorable contribution to  must therefore arise from other contacts, as one might expect, for example, with hydrophobic residues Ile222 and Trp178 (Fig. 2A▶).

must therefore arise from other contacts, as one might expect, for example, with hydrophobic residues Ile222 and Trp178 (Fig. 2A▶).

Table 5.

Calculated change in binding free energy and its components, using MM/PB potential (kcal/mole), on substitution of C4 functional group for H via direct perturbation (DP) and via relaxed perturbation using DDD and GB solvent models

| Perturbation |  |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-DANA → H-DANA (DP) | 125.8 | −0.5 | −85.2 | 40.1 |

| N-DANA → H-DANA (GB) | 129.4 | −1.9 | −87.1 | 40.4 |

| N-DANA → H-DANA (DDD) | 133.1 | −10.5 | −91.9 | 30.7 |

| DANA → H-DANA (GB) | −6.0 | 1.7 | 2.2 | −2.1 |

| DANA → H-DANA (DDD) | −4.5 | −0.2 | 3.2 | −1.5 |

| GANA → H-DANA (GB) | 126.8 | 7.3 | −86.6 | 47.5 |

| GANA → H-DANA (DDD) | 132.2 | −0.1 | −94.8 | 37.3 |

| NMe3-DANA → H-DANA (GB) | 103.0 | 4.1 | −65.5 | 41.6 |

| NMe3-DANA → H-DANA (DDD) | 96.4 | 1.8 | −64.3 | 33.9 |

In a study of selected neuraminidase inhibitors (Woods et al. 2001), it has been noted that calculation of binding free energy and in particular ΔGsolv using the PB model is sensitive to solute configuration. The PB solvation free energy for N-DANA ( ) is reported in Table 3▶. A standard deviation of 4.8 kcal/mole for

) is reported in Table 3▶. A standard deviation of 4.8 kcal/mole for  does indeed reflect a measure of variability over the ensemble of configurations. However, although solvation and desolvation free energies are subject to fluctuation, the observed negative correlation of desolvation contributions with electrostatic protein–ligand binding energy over the course of the trajectory (Lee et al. 2000) ensures a lower configurational dependence of overall

does indeed reflect a measure of variability over the ensemble of configurations. However, although solvation and desolvation free energies are subject to fluctuation, the observed negative correlation of desolvation contributions with electrostatic protein–ligand binding energy over the course of the trajectory (Lee et al. 2000) ensures a lower configurational dependence of overall  (Table 3▶).

(Table 3▶).

For comparison, we also calculate the desolvation contribution via the analytical GB model. The GB model appears to underpredict the absolute desolvation energy of the N-DANA/neuraminidase complex and the ligand solvation energy relative to the physically rigorous PB model (Table 3▶). This leads to a more negative overall binding free energy of −47.2 kcal/mole. Inclusion of solute entropic contributions results in overestimation of absolute  by 27.0 kcal/mole relative to experiment, using the force field/GB potential.

by 27.0 kcal/mole relative to experiment, using the force field/GB potential.  shows a similar spread to the values obtained via the PB approach (Table 3▶). Several comparisons of PB and GB solvation energies have been made (Edinger et al. 1997; Srinivasan et al. 1999; David et al. 2000); GB approximates relative PB energetics well if appropriately parametrized (Wang and Wade 2003). However, particularly for absolute solvation energies of species with net charge (Edinger et al. 1997) and with increased burial of charge on binding (Srinivasan et al. 1999), the models can diverge.

shows a similar spread to the values obtained via the PB approach (Table 3▶). Several comparisons of PB and GB solvation energies have been made (Edinger et al. 1997; Srinivasan et al. 1999; David et al. 2000); GB approximates relative PB energetics well if appropriately parametrized (Wang and Wade 2003). However, particularly for absolute solvation energies of species with net charge (Edinger et al. 1997) and with increased burial of charge on binding (Srinivasan et al. 1999), the models can diverge.

A number of binding affinity calculations for neuraminidase inhibitors have been previously performed (Table 4▶). Studies by Taylor and von Itzstein (1996) and by Smith et al. (2001) used a thermodynamic cycle approach to calculate the electrostatic contribution to binding via the PB model. The Taylor study ranked inhibitors according to an average binding energy of a small set of conformations of the enzyme–inhibitor complex, with structures obtained from a dynamics/quenching protocol, using explicit solvent and a distance-dependent dielectric (DDD) of ɛ(r) = r; and also according to the single lowest energy obtained from that approach. Smith et al. (2001) calculated  from the crystal structure, optimizing only protein hydrogen and ligand atoms. By using a single N-DANA/neuraminidase structure, both studies predicted a binding free energy of −20 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). Modeling Glu119 in its neutral form, Smith et al. found a reduced magnitude of

from the crystal structure, optimizing only protein hydrogen and ligand atoms. By using a single N-DANA/neuraminidase structure, both studies predicted a binding free energy of −20 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). Modeling Glu119 in its neutral form, Smith et al. found a reduced magnitude of  for N-DANA of −12.7 kcal/mole. These estimates are lower limits, due to the neglect of van der Waals interactions and nonpolar contributions to solvation energy. Interestingly, although total

for N-DANA of −12.7 kcal/mole. These estimates are lower limits, due to the neglect of van der Waals interactions and nonpolar contributions to solvation energy. Interestingly, although total  broadly agree, the components are quite different for the studies. Indeed, the N-DANA/neuraminidase electrostatic interaction energy is estimated to be −170 kcal/mole for the Taylor study and −209.6 kcal/mole and Smith study, incorporating a neutral Glu119 residue; the calculated electrostatic interaction energy of −179.1 kcal/mole in this work lies between these two values (Table 3▶). Differences in net electrostatic interaction were attributed to differences in solute atom point charges and radii, derived variously from CVFF (Dauber-Osguthorpe et al. 1988) and SIP (Smith and Hall 1999) parametrizations and electrostatic potential fitting. However, both previous PB studies predict a net favorable electrostatic interaction of N-DANA with neuraminidase; this contrasts with the single-conformation calculation here, which finds a net unfavorable electrostatic interaction, outweighed by a favorable van der Waals contribution to association.

broadly agree, the components are quite different for the studies. Indeed, the N-DANA/neuraminidase electrostatic interaction energy is estimated to be −170 kcal/mole for the Taylor study and −209.6 kcal/mole and Smith study, incorporating a neutral Glu119 residue; the calculated electrostatic interaction energy of −179.1 kcal/mole in this work lies between these two values (Table 3▶). Differences in net electrostatic interaction were attributed to differences in solute atom point charges and radii, derived variously from CVFF (Dauber-Osguthorpe et al. 1988) and SIP (Smith and Hall 1999) parametrizations and electrostatic potential fitting. However, both previous PB studies predict a net favorable electrostatic interaction of N-DANA with neuraminidase; this contrasts with the single-conformation calculation here, which finds a net unfavorable electrostatic interaction, outweighed by a favorable van der Waals contribution to association.

Incorporating the effect of conformational averaging,  predicted by the minimized ensemble from the Taylor study is reduced to −10 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). Although close to the MD ensemble averaged

predicted by the minimized ensemble from the Taylor study is reduced to −10 kcal/mole (Table 4▶). Although close to the MD ensemble averaged  of −15.1 kcal/ mole obtained here (Table 4▶), the latter value additionally incorporates van der Waals, nonpolar solvation, and thermal contributions. The electrostatic components are more similar than in the single-conformation studies, but the Taylor study still predicts a net favorable electrostatic contribution, in contrast to a net

of −15.1 kcal/ mole obtained here (Table 4▶), the latter value additionally incorporates van der Waals, nonpolar solvation, and thermal contributions. The electrostatic components are more similar than in the single-conformation studies, but the Taylor study still predicts a net favorable electrostatic contribution, in contrast to a net  of 16.0 kcal/mole obtained here (Table 3▶). To summarize, therefore, our computational analysis indicates a net unfavorable electrostatic free energy contribution to binding of N-DANA, compensated by attractive van der Waals and nonpolar solvation contributions. This observation regarding electrostatics agrees with MM-PB/SA studies of other protein–ligand systems (Donini and Kollman 2000; Kuhn and Kollman 2000a,b; T. Hou et al. 2002; Kalra et al. 2002) and with purely PB calculations (Misra et al. 1994; Shen and Wendoloski 1996; Bruccoleri et al. 1997), but contrasts with previous PB studies of neuraminidase inhibitors (Jedrzejas et al. 1995; Taylor and von Itzstein 1996; Smith et al. 2001). Comparison of neuraminidase studies highlights sensitivity of calculation of absolute

of 16.0 kcal/mole obtained here (Table 3▶). To summarize, therefore, our computational analysis indicates a net unfavorable electrostatic free energy contribution to binding of N-DANA, compensated by attractive van der Waals and nonpolar solvation contributions. This observation regarding electrostatics agrees with MM-PB/SA studies of other protein–ligand systems (Donini and Kollman 2000; Kuhn and Kollman 2000a,b; T. Hou et al. 2002; Kalra et al. 2002) and with purely PB calculations (Misra et al. 1994; Shen and Wendoloski 1996; Bruccoleri et al. 1997), but contrasts with previous PB studies of neuraminidase inhibitors (Jedrzejas et al. 1995; Taylor and von Itzstein 1996; Smith et al. 2001). Comparison of neuraminidase studies highlights sensitivity of calculation of absolute  according to choice of solvent model parameters (solute radii and charges), force field, and conformational sampling. However, it is reasonable to expect less sensitivity in inhibitor ranking according to calculated

according to choice of solvent model parameters (solute radii and charges), force field, and conformational sampling. However, it is reasonable to expect less sensitivity in inhibitor ranking according to calculated  .

.

Perturbative calculations for inhibitor ranking

We now explore the potential of the MM/continuum model approach to rank the binding affinity of other neuraminidase inhibitors, GANA, DANA, and 4-trimethylamino-DANA (NMe3-DANA), based on the N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory. The four-ammonium group of N-DANA is replaced with other functional groups (e.g., NH3+ → NHCH(NH2)2 for configurations along the trajectory and the binding free energy reevaluated via the hybrid MM/PB potential. We permit structural relaxation around the perturbed ligand, with energy minimization of an 8 Å sphere encompassing ligand and proximal amino acids. Multiple rotamers of the perturbed ligand fragment are considered, in addition to conformational sampling of amino acid side chains engendered by MD simulation. Structural relaxation via energy minimization of a perturbed inhibitor and its amino acid sphere was performed using two strategies to incorporate the effect of aqueous solvent on structure: a DDD of 4r (Gelin and Karplus 1975); or the GB solvent model (Tsui and Case 2001).

As a prerequisite to analysis of relaxed perturbed trajectories, we evaluate the effect of implicit solvent models on structure and energetics of the reference N-DANA/neuraminidase ensemble. The mean unsigned errors with respect to the crystallographic ligand-protein distances for GB (0.29 Å) and DDD (0.28 Å) solvent models (Table 3▶) are comparable to that obtained from MD (Table 1▶). Some structural rearrangement of the explicitly solvated MD configurations occurs on optimization of ligand and its protein environment in the presence of implicit GB or DDD solvent (Tables 1▶, 3▶, 6▶). On average, protein–ligand distances in the DDD-derived ensemble are reduced by 0.14 Å relative to experiment, and reduced by 0.11 Å relative to MD. By using the GB solvent model, distances are essentially the same as from crystallography. As expected, optimization of protein–ligand contacts via local minimization of configurations drawn from the 300 K ensemble leads to a more negative predicted absolute  , relative to the unrelaxed ensemble energies. For the GB-derived ensemble evaluated using the MM/PB potential, there is an increase in affinity from −15.1 kcal/mole to −22.9 kcal/mole (Tables 3▶, 7▶). As for the MD reference ensemble, the binding free energy comprises a net positive electrostatic component and a favorable van der Waals interaction. For minimization in the presence of DDD solvent, energetic stabilization is more pronounced: A large negative

, relative to the unrelaxed ensemble energies. For the GB-derived ensemble evaluated using the MM/PB potential, there is an increase in affinity from −15.1 kcal/mole to −22.9 kcal/mole (Tables 3▶, 7▶). As for the MD reference ensemble, the binding free energy comprises a net positive electrostatic component and a favorable van der Waals interaction. For minimization in the presence of DDD solvent, energetic stabilization is more pronounced: A large negative  of −35.1 kcal/mole calculated within the DDD-derived ensemble has a negative net electrostatic component (Table 8▶). As documented elsewhere (Schaefer et al. 1999; Wang and Wade 2003), the DDD model overweights solute electrostatic interactions, evidenced here by reduced average interaction distances (Table 1▶) relative to MD and crystallography, and a correspondingly deleterious effect on van der Waals interactions (Table 8▶).

of −35.1 kcal/mole calculated within the DDD-derived ensemble has a negative net electrostatic component (Table 8▶). As documented elsewhere (Schaefer et al. 1999; Wang and Wade 2003), the DDD model overweights solute electrostatic interactions, evidenced here by reduced average interaction distances (Table 1▶) relative to MD and crystallography, and a correspondingly deleterious effect on van der Waals interactions (Table 8▶).

Table 6.

Distances (Å) between C4 substituent atoms on ligand and protein, for crystal structures (RXRD), and average structures via relaxed perturbation using DDD (RDDD) and GB (RGB) solvent models

| Ligand | Protein | RXRD | RDDD | RGB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-OH O | Glu119 Oɛ1 | 3.18 | 3.09 (0.54) | 2.85 (0.16) |

| 4-OH O | Glu119 Oɛ2 | 4.27 | 4.12 (0.33) | 4.08 (0.27) |

| 4-OH O | Asp151 Oδ1 | 3.47 | 4.04 (1.07) | 3.92 (0.62) |

| 4-OH O | Asp151 Oδ2 | 3.85 | 4.44 (1.19) | 4.29 (1.11) |

| MUE | 0.35 | 0.35 | ||

| 4-NH3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ1 | 2.96 | 2.70 (0.04) | 2.80 (0.05) |

| 4-NH3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ2 | 4.26 | 4.29 (0.40) | 4.15 (0.32) |

| 4-NH3+ N | Asp151 Oδ1 | 4.36 | 3.67 (0.85) | 3.96 (1.29) |

| 4-NH3+ N | Asp151 Oδ2 | 2.75 | 2.90 (0.58) | 3.53 (0.83) |

| MUE | 0.28 | 0.36 | ||

| Gua N4 | Trp178 O | 3.14 | 3.12 (0.36) | 3.18 (0.23) |

| Gua N4 | Glu227 Oɛ1 | 4.04 | 4.50 (0.20) | 4.50 (0.22) |

| Gua N4 | Glu227 Oɛ2 | 2.91 | 3.79 (0.77) | 3.32 (0.27) |

| Gua N3 | Asp151 O | 3.14 | 3.23 (0.42) | 3.01 (0.23) |

| Gua N3 | Asp151 Oδ1 | 3.97 | 3.69 (1.44) | 4.01 (1.02) |

| Gua N3 | Asp151 Oδ2 | 5.60 | 4.45 (1.38) | 4.97 (1.39) |

| Gua N3 | Trp178 O | 2.84 | 2.83 (0.08) | 3.00 (0.19) |

| Gua N3 | Arg156 Nη1 | 3.41 | 3.27 (0.14) | 3.07 (0.08) |

| Gua N2 | Asp151 Oδ1 | 2.91 | 3.62 (1.06) | 3.79 (0.80) |

| Gua N2 | Asp151 Oδ2 | 4.59 | 4.15 (1.18) | 4.21 (1.32) |

| Gua N2 | Glu119 Oɛ1 | 3.38 | 3.35 (0.13) | 3.20 (0.16) |

| Gua N2 | Glu119 Oɛ2 | 4.32 | 4.05 (0.16) | 4.14 (0.28) |

| MUE | 0.37 | 0.32 | ||

| NMe3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ1 | — | 3.86 (0.16) | 3.73 (0.13) |

| NMe3+ N | Glu119 Oɛ2 | — | 4.17 (0.29) | 4.03 (0.19) |

| NMe3+ N | Asp151 Oɛ1 | — | 4.89 (0.93) | 4.67 (1.00) |

| NMe3+ N | Asp151 Oɛ2 | — | 4.16 (0.67) | 4.40 (0.53) |

Standard deviations in parentheses. Mean unsigned error (MUE) is with respect to distances in crystal structure (RXRD).

Table 7.

Total calculated binding free energies and components using ensemble-averaged MM/PB model (kcal/mole) after replacing group NH3+at C4 by OH, N(CH3)3+and NHC(NH2)2+, followed by local minimization using the GB solvent model

| Model |  |

|

|

ΔΔGnpRL |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANA | −62.9 (15.4) | −29.3 (1.7) | 116.3 (10.4) | −4.4 (0.1) | 19.7 (12.0) |

| N-DANA | −198.3 (18.3) | −25.7 (1.7) | 205.6 (17.8) | −4.4 (0.1) | −22.9 (4.8) |

| NMe3-DANA | −171.9 (12.5) | −31.7 (2.1) | 184.4 (12.3) | −4.8 (0.1) | −23.9 (4.6) |

| GANA | −195.7 (17.2) | −34.9 (2.3) | 205.4 (15.4) | −4.7 (0.1) | −29.8 (4.7) |

Unperturbed trajectory in bold. Standard deviations in parentheses.

Table 8.

Total calculated binding free energies and components using MM/PB model (kcal/mole) after replacing group NH3+at C4 by OH, N(CH3)3+, and NHC(NH2)2+, followed by local minimization using the DDD solvent model

| Model |  |

|

|

ΔΔGnpRL |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANA | −92.7 (10.7) | −7.8 (3.1) | 102.0 (12.3) | −4.4 (0.1) | −2.8 (9.0) |

| N-DANA | −230.3 (14.3) | 2.5 (2.7) | 197.2 (15.1) | −4.5 (0.1) | −35.1 (5.1) |

| NMe3-DANA | −193.6 (9.1) | −9.8 (3.4) | 169.9 (9.0) | −4.8 (0.1) | −38.2 (3.8) |

| GANA | −229.3 (16.7) | −8.1 (3.1) | 200.2 (13.6) | −4.6 (0.1) | −41.9 (5.7) |

Unperturbed trajectory in bold. Standard deviations in parentheses.

We now consider calculation of  for three other neuraminidase inhibitors using perturbation of the N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory, with structural relaxation and subsequent energetic analysis using the MM/PB potential.

for three other neuraminidase inhibitors using perturbation of the N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory, with structural relaxation and subsequent energetic analysis using the MM/PB potential.

GB-derived ensemble

Within the GB-derived ensemble, the most favorable binding affinity is predicted for the ligand GANA, with a calculated  of −29.8 kcal/mole (Table 7▶). Binding of GANA with the protein has the largest van der Waals contribution of the four inhibitors. Structurally, minimization of GANA/neuraminidase configurations in GB solvent reproduces the majority of crystal contacts of the guanidino group, with a MUE for interaction distances at C4 of 0.32 Å (Table 6▶). Relaxation occurs as the guanidino group is accommodated within the acidic pocket: The Glu119 Oɛ1 hydrogen bond distance to the ligand 4-N atom increases from 2.88 Å for N-DANA in the reference MD ensemble (Table 1▶) to 3.20 Å for GANA in the GB-derived ensemble, close to its value of 3.38 Å in the crystal (Table 6▶). The guanidino substituent of GANA also displaces waters bound in the N-DANA/neuraminidase complex. For example, water W3 occupies the approximate location of atom N4 of GANA (Fig. 4▶), with a W…Oɛ2 Glu227 distance in the reference N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory of 2.75 Å (Table 2▶). The corresponding GANA N4…Oɛ2 Glu227 interatomic separation is larger, at 3.32 Å in the GB-minimized ensemble (Table 6▶), but is in reasonable agreement with a distance of 2.91 Å in the GANA/neuraminidase crystal structure.

of −29.8 kcal/mole (Table 7▶). Binding of GANA with the protein has the largest van der Waals contribution of the four inhibitors. Structurally, minimization of GANA/neuraminidase configurations in GB solvent reproduces the majority of crystal contacts of the guanidino group, with a MUE for interaction distances at C4 of 0.32 Å (Table 6▶). Relaxation occurs as the guanidino group is accommodated within the acidic pocket: The Glu119 Oɛ1 hydrogen bond distance to the ligand 4-N atom increases from 2.88 Å for N-DANA in the reference MD ensemble (Table 1▶) to 3.20 Å for GANA in the GB-derived ensemble, close to its value of 3.38 Å in the crystal (Table 6▶). The guanidino substituent of GANA also displaces waters bound in the N-DANA/neuraminidase complex. For example, water W3 occupies the approximate location of atom N4 of GANA (Fig. 4▶), with a W…Oɛ2 Glu227 distance in the reference N-DANA/neuraminidase trajectory of 2.75 Å (Table 2▶). The corresponding GANA N4…Oɛ2 Glu227 interatomic separation is larger, at 3.32 Å in the GB-minimized ensemble (Table 6▶), but is in reasonable agreement with a distance of 2.91 Å in the GANA/neuraminidase crystal structure.

Although the method correctly identifies GANA as the tightest binding inhibitor, the ranking of the four ligands is not in accord with experiment, with GANA > NMe3-DANA > N-DANA > DANA (Table 4▶). This would appear to be due to overestimation of the stability of NMe3-DANA. Because of three lipophilic methyl groups at the four-position, this ligand forges strong van der Waals interactions with neuraminidase, and experiences a low desolvation penalty. Relative to N-DANA, desolvation and favorable van der Waals interactions stabilize NMe3-DANA by 21.6 and 6.0 kcal/mole, respectively (Table 7▶), although electrostatic interaction with protein is predictably lowered relative to N-DANA due to absence of hydrogen bonds (Table 7▶). The calculated ranking of the inhibitors may also be due to inadequate treatment of protein-bound water molecules (Fig. 2▶), which could lead to underestimation of the binding affinity of DANA and N-DANA particularly. The zwitterionic inhibitors are clearly distinguished from the anionic DANA ligand, as indicated by mutation of four-substituents to a H atom. Calculations find a favorable group free energy contribution by cationic substituents of magnitude 40.4 to 47.5 kcal/mole (Table 5▶). This is principally electrostatic for the NH3+ group, although favorable van der Waals contributions are made by the larger NMe3+ and NHCH(NH2)2+ groups. The net contribution of the neutral OH group to binding is unfavorable (2.1 kcal/mole). Similarly, a GRID study of neuraminidase found no significant favorable interaction could be detected with a hydroxyl probe at the four-position of DANA but only at glycerol and carboxylate regions of the inhibitor (von Itzstein et al. 1996).

DDD-derived ensemble

We now consider calculation of relative binding affinity of the inhibitors via the MM/PB potential within the DDD-derived ensemble. As for the GB-derived ensemble, GANA has the most favorable calculated interaction energy of the four ligands, with a  of −41.9 kcal/mole (Table 8▶). The ranking of ligands follows the ordering calculated via the GB-derived ensemble, with overstabilization of NMe3-DANA (Table 4▶). We note that the binding affinity of neuraminidase inhibitors has also been calculated from analysis of ensembles by using the LIE method (Wall et al. 1999), incorporating atomistic solvent. Although the approach found difficulty in identifying GANA as the most potent inhibitor (Table 4▶), a good correlation between differential electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energy and experimentally determined binding free energy was obtained for the full set of 15 inhibitors (cross-validation regression coefficient q2 of 0.74). The optimal multiple linear regression fit obtained a ranking of N-DANA > GANA > DANA > NMe3-DANA (Table 4▶).

of −41.9 kcal/mole (Table 8▶). The ranking of ligands follows the ordering calculated via the GB-derived ensemble, with overstabilization of NMe3-DANA (Table 4▶). We note that the binding affinity of neuraminidase inhibitors has also been calculated from analysis of ensembles by using the LIE method (Wall et al. 1999), incorporating atomistic solvent. Although the approach found difficulty in identifying GANA as the most potent inhibitor (Table 4▶), a good correlation between differential electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energy and experimentally determined binding free energy was obtained for the full set of 15 inhibitors (cross-validation regression coefficient q2 of 0.74). The optimal multiple linear regression fit obtained a ranking of N-DANA > GANA > DANA > NMe3-DANA (Table 4▶).

As before for the GB-derived ensemble, perturbation of four-substituents to a H atom in conjunction with the DDD solvent model (Table 5▶) distinguishes the favorable cationic group free energies (30.7–37.3 kcal/mole) from the unfavorable hydroxyl group interaction (1.5 kcal/mole). The similarity in relative energetics for the DDD and GB solvent models is reflected structurally, with comparably small deviations from crystallographic distances at C4 (Table 6▶). For example, the mean unsigned error for contacts at the four-position of GANA is 0.37 Å for DDD, compared with 0.32 Å for the GB solvent model (Table 6▶). This is in accord with consideration of all N-DANA/neuraminidase ligand polar contacts (Table 1▶).

With respect to the anionic ligand, DANA, we note that calculated  is considerably less favorable than for the zwitterionic ligands (Table 4▶); similarly, the standard deviation on

is considerably less favorable than for the zwitterionic ligands (Table 4▶); similarly, the standard deviation on  for this inhibitor is significantly larger than for the zwitterionic ligands, with values of 12.0 kcal/ mole via GB or 9.0 kcal/mole via DDD minimization approaches (Tables 7▶, 8▶). Increasing the sampling frequency to 42 snapshots over the trajectory did not diminish the magnitude of this uncertainty. Inspection of DANA/neuraminidase configurations indicates a measure of conformational heterogeneity in protein accommodation of the anionic ligand within the zwitterionic reference trajectory. This fluctuation may be indicative of the need for treatment of important bound water molecules via an explicit solvent model.

for this inhibitor is significantly larger than for the zwitterionic ligands, with values of 12.0 kcal/ mole via GB or 9.0 kcal/mole via DDD minimization approaches (Tables 7▶, 8▶). Increasing the sampling frequency to 42 snapshots over the trajectory did not diminish the magnitude of this uncertainty. Inspection of DANA/neuraminidase configurations indicates a measure of conformational heterogeneity in protein accommodation of the anionic ligand within the zwitterionic reference trajectory. This fluctuation may be indicative of the need for treatment of important bound water molecules via an explicit solvent model.

Conclusions

The complex of N-DANA with influenza neuraminidase has been simulated by using MD calculations. A dynamical model of the complex containing an ionized Glu119 residue in the active site of the protein was found to be consistent with experimental data. Contrary to previous computational neuraminidase studies, free energy analysis of the protein–ligand ensemble using a combined MM/continuum solvent model approach found net electrostatics to disfavor inhibitor binding, with a significant favorable contribution arising instead from van der Waals interactions with the protein. Although net positive electrostatic binding free energies appear to be a general feature of ligand-receptor interactions, we note that calculation of absolute  is expected to be more sensitive to parameters such as solute radii and atom-centered partial charges, compared with the relative free energies of binding calculated here.

is expected to be more sensitive to parameters such as solute radii and atom-centered partial charges, compared with the relative free energies of binding calculated here.

A perturbation methodology was explored, using a combined MM/PB potential to evaluate ensembles of structures determined from conformational search/local minimization schemes using DDD or GB solvent models. Based on a 2-nsec MD trajectory of N-DANA/neuraminidase complex in aqueous solution, the approach was applied to estimate group free energy contributions and to predict binding affinity for four neuraminidase inhibitors. Group free energy analysis agrees with a previous GRID study (von Itzstein et al. 1996) in that the 4-OH group makes no favorable contribution to  of DANA. Conversely, cationic groups at the four-position form favorable electrostatic interactions. Both minimization approaches agree on a ranking of GANA > NMe3-DANA > N-DANA > DANA, in which the NMe3-DANA ligand appears to be overstabilized. The magnitudes of calculated relative

of DANA. Conversely, cationic groups at the four-position form favorable electrostatic interactions. Both minimization approaches agree on a ranking of GANA > NMe3-DANA > N-DANA > DANA, in which the NMe3-DANA ligand appears to be overstabilized. The magnitudes of calculated relative  are comparable for GB and DDD approaches. Structural interpretation of calculated

are comparable for GB and DDD approaches. Structural interpretation of calculated  is not straightforward. The perturbation strategies detect the majority of crystallographically observed contacts of the four-substituent. However, for the DDD model, known to underscreen charge–charge interactions, a general contraction in protein–ligand interatomic distances relative to experiment and explicit solvent calculations is observed. This leads to overestimated protein–ligand electrostatic interactions and alteration of the balance with van der Waals contributions predicted by MM-PB/SA analysis of explicit solvent MD. We also note that the perturbation via GB and DDD solvent models underpredict

is not straightforward. The perturbation strategies detect the majority of crystallographically observed contacts of the four-substituent. However, for the DDD model, known to underscreen charge–charge interactions, a general contraction in protein–ligand interatomic distances relative to experiment and explicit solvent calculations is observed. This leads to overestimated protein–ligand electrostatic interactions and alteration of the balance with van der Waals contributions predicted by MM-PB/SA analysis of explicit solvent MD. We also note that the perturbation via GB and DDD solvent models underpredict  for DANA, and may result from the use of a reference trajectory using a zwitterionic inhibitor, leading to difficulty in appropriately relaxing the enzyme around significant changes in ligand charge distribution. Here, replacement of a cationic group with the hydroxyl function of DANA breaks a protein–ligand salt-bridge, leading to fluctuation in local structure and poor convergence in calculated

for DANA, and may result from the use of a reference trajectory using a zwitterionic inhibitor, leading to difficulty in appropriately relaxing the enzyme around significant changes in ligand charge distribution. Here, replacement of a cationic group with the hydroxyl function of DANA breaks a protein–ligand salt-bridge, leading to fluctuation in local structure and poor convergence in calculated  for DANA. Dependence on reference trajectory was similarly highlighted by a MM-PB/SA study of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (Donini and Kollman 2000), in which zwitterionic ligands were understabilized relative to anionic ligands, when evaluated within a reference trajectory based on an anionic ligand.

for DANA. Dependence on reference trajectory was similarly highlighted by a MM-PB/SA study of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (Donini and Kollman 2000), in which zwitterionic ligands were understabilized relative to anionic ligands, when evaluated within a reference trajectory based on an anionic ligand.

A perturbative MM/continuum model approach shows promise in calculating binding affinity from a single MD trajectory. Clearly, the choice of reference ligand/protein trajectory and relaxation of a perturbed ligand within that trajectory requires careful consideration. A recent study (David et al. 2000) concluded that the GB solvent model yields more accurate gradients than does the DDD model, relative to the reference PB solution. To combine the advantages of the DDD approach, in particular computational expediency, with improved accuracy, an implicit solvent model with improved solvent screening properties model such as the NPSA method (Wang and Wade 2003) could be considered in future development. Improvements to the method to should enable it to be integrated into the drug design process, providing rapid ensemble-averaged evaluation of binding free energy for a library of fragment modifications to inhibitors, the most promising of which can be subsequently validated by more computationally intensive free energy perturbation calculations.

Materials and methods

Force field and MD

Atomic coordinates of subtype N9 (A/TERN/AUSTRALIA/ G70C/75) influenza neuraminidase/N-DANA inhibitor complex were taken from the crystal structures of the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB): PDB code, 1F8C (Smith et al. 2001); resolution, 1.7 Å. Structures of complexes containing DANA (Smith et al. 2001) and GANA (Varghese et al. 1995), discussed in this work, correspond to PDB codes 1F8B and 1NNC, respectively. Inhibitor charges were derived from a multiconformational RESP-based approach (Bayly et al. 1993; Cornell et al. 1993), using the HF/6-31G* electrostatic potential via the Gaussian 98 package (Frisch et al. 1998). Conformations were generated from Monte Carlo simulations using default AMBER* force field parameters from Mac-roModel version 5 (Mohamadi et al. 1990). Nonelectrostatic parameters were modeled from the parm99 force field (Wang et al. 2000).

All oligosaccharides were removed from the crystal structure. Cations were retained (one near the active site), and chloride anions were added to neutralize the system. All waters of hydration within 3 Å of the active site were preserved. Protein hydrogens were added by using the program PROTONATE (Case et al. 1996). The tautomeric states of histidines were assigned according to local environment in the crystal. Amino and guanidino substituents on inhibitors were protonated, in accord with physiological pH. In addition, the side chain of Asn294 in the N-DANA/neuraminidase complex was rotated to invert the location of the Oδ1 and Nδ2 atoms of the amide group, and to form hydrogen bonds instead of repulsive interactions with nearby Ala246 O and Arg292 Nɛ atoms. This was due to probable misassignment in the crystal structure (the spurious interactions were highlighted by MD simulations; correction led to a lower root mean square deviation and improved overall agreement with the crystal structure). Prior to minimization and MD, the enzyme–inhibitor complex was immersed in a box of TIP3P water (Jorgensen et al. 1983) comprising ~5900 atoms. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed in conjunction with the particle-mesh Ewald method (Essmann et al. 1995) for long-range electrostatic interactions. A cutoff of 8 Å was used for Lennard-Jones interactions and SHAKE (Ryckaert et al. 1977) to constrain all covalent bonds involving hydrogen. MD simulations using the AMBER suite of programs (Case et al. 1996) were carried out at 300 K with a time step of 2 psec. Initial minimization was followed by a short MD run to remove initial bad contacts of water and counterions and to fill vacuum pockets, in combination with restraints to keep the initial conformation of the complex fixed. Subsequent equilibration involved smoothly decreasing harmonic restraints on the complexes and alternating P and V constraints over 50-psec intervals. A 60-psec equilibration phase of NVT dynamics without constraints was followed by 2-nsec NVT production trajectories. Structures were archived for structural analysis every 4 psec.

Energetic analysis

Energetic postprocessing of the trajectories was performed by using a MM and continuum solvent model approach (Srinivasan et al. 1998). This method calculates a gas-phase contribution to binding using an all-atom force field and incorporates the influence of solvent via the PB (Gilson et al. 1987) or GB continuum solvent models (Still et al. 1990; Jayaram et al. 1998), leading to the MM-PB/SA and MM-GB/SA approaches, respectively. A free energy difference between bound and free protein receptor (R) and ligand (L) is calculated at points along the trajectories by using the equation

|

(1) |

where  and

and  is the enthalpy and entropy of R-L binding, respectively, without solvent contributions, and T is temperature.

is the enthalpy and entropy of R-L binding, respectively, without solvent contributions, and T is temperature.  is composed of ensemble-averaged electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies,

is composed of ensemble-averaged electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies,  and

and  . The vibrational solute entropy term was calculated from summation over normal modes by using the nmode module of AMBER6 (Case et al. 1996). Because of issues of computational tractability, residues >6 Å from the active site were neglected; the resulting subsystem was minimized by using a DDD constant of 4r and entropic contributions calculated (Kuhn and Kollman 2000a; Wang et al. 2001; S. Hou et al. 2002). The average of two configurations was used to estimate the entropy contribution to binding.

. The vibrational solute entropy term was calculated from summation over normal modes by using the nmode module of AMBER6 (Case et al. 1996). Because of issues of computational tractability, residues >6 Å from the active site were neglected; the resulting subsystem was minimized by using a DDD constant of 4r and entropic contributions calculated (Kuhn and Kollman 2000a; Wang et al. 2001; S. Hou et al. 2002). The average of two configurations was used to estimate the entropy contribution to binding.  is the ensemble-averaged difference in solvation free energy between R and L, bound and free. The electrostatic contribution to solvation is

is the ensemble-averaged difference in solvation free energy between R and L, bound and free. The electrostatic contribution to solvation is  . The linear PB equation was solved by using the DelPhi program (Gilson et al. 1987), with a 0.5 Å grid resolution extending 20% beyond the solute. A solute dielectric of unity and solvent dielectric of 80 was used, in conjunction with PARSE radii (Sitkoff et al. 1994) and RESP atom-centered charges. The MSMS program (Sanner et al. 1996) was used to calculate the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) for nonpolar contributions to solvation,

. The linear PB equation was solved by using the DelPhi program (Gilson et al. 1987), with a 0.5 Å grid resolution extending 20% beyond the solute. A solute dielectric of unity and solvent dielectric of 80 was used, in conjunction with PARSE radii (Sitkoff et al. 1994) and RESP atom-centered charges. The MSMS program (Sanner et al. 1996) was used to calculate the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) for nonpolar contributions to solvation,  , evaluated as (0.00542•SASA + 0.92) kcal/mole. GB calculations used a parametrization consistent for use with AMBER (Jayaram et al. 1998; Tsui and Case 2001). In this case, nonpolar contributions were evaluated as (0.0072•SASA) kcal/mole. Configurations were drawn from the last nanosecond of the trajectory, at 32-psec intervals to ensure minimal correlation of configurations, providing 32 configurations for each complex. Energetic analysis of X-ray geometries was performed on the crystal structure energy-minimized in the presence of explicit solvent molecules.

, evaluated as (0.00542•SASA + 0.92) kcal/mole. GB calculations used a parametrization consistent for use with AMBER (Jayaram et al. 1998; Tsui and Case 2001). In this case, nonpolar contributions were evaluated as (0.0072•SASA) kcal/mole. Configurations were drawn from the last nanosecond of the trajectory, at 32-psec intervals to ensure minimal correlation of configurations, providing 32 configurations for each complex. Energetic analysis of X-ray geometries was performed on the crystal structure energy-minimized in the presence of explicit solvent molecules.

Perturbative calculations

To enable perturbation of inhibitor chemical groups within the MM/continuum model methodology, an algorithm was implemented to substitute a new fragment functional group on to an existing ligand molecular framework via rigid body superposition (Kearsley 1989), coupled with conformational search of possible fragment rotamers. Where subsequent relaxation of ligand and its immediate environment was permitted, minimization of aminoacid residues within an inclusive 8 Å radius around the ligand was performed, involving 2500 steps of steepest descents (500 steps)/conjugate gradients (2000 steps). The effect of solvent on structure was modeled using two approaches: a DDD ɛ(r) = 4r (Gelin and Karplus1975); or a GB potential (Tsui and Case 2001). Application of this conformational search/implicit solvent minimization, with subsequent calculation of conformer energies by the hybrid MM/PB potential to each configuration, permitted evaluation of 20 equispaced configurations from the last nanosecond of the trajectory.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from Wellcome Trust Grant 063492 and the Ramsay Trust.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

We also point out a very recently published study of four neuraminidase ligands using a combined force field/continuum model approach, which similarly highlights the importance of nonpolar interactions in determining ligand potency ( Masukawa, K.M., Kollman, P.A., and Kuntz, I.D. 2003. Investigation of neuraminidase substrate recognition using molecular dynamics and free energy calculations. J. Med. Chem. 46 5628–5637 ).

Abbreviations

DANA, 2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid

N-DANA, 4-amino-2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid

GANA, 4-guanidino-2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid

NMe3-DANA, 4-trimethylamino-2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid

MD, molecular dynamics

PB, Poisson-Boltzmann

GB, generalized Born

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03129704

References

- Bayly, C.I., Cieplak, P., Cornell, W.D., and Kollman, P.A. 1993. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: The RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 97 10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- Bruccoleri, R.E., Novotny, J., and Davis, M.E. 1997. Finite difference Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatic calculations: Increased accuracy achieved by harmonic dielectric smoothing and charge. J. Comput. Chem. 18 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, R.A., Hillier, I.H., and Naismith, J.N. 2001. Carbohydrate–protein recognition: Molecular dynamics simulations and free energy analysis of oligosaccharide binding to concanavalin A. Biophys. J. 81 1373–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case, D.A., Pearlman, D.A., Caldwell, J.W., Cheatham III, T.E., Ross, W.S., Simmerling, C.L., Darden, T.A., Merz, K.M., Stanton, R.V., Cheng, A.L., et al. 1996. AMBER6. University of California, San Francisco.

- Cheatham III, T.E., Srinivasan, J., Case, D.A., and Kollman, P.A. 1998. Molecular dynamics and continuum solvent studies of the stability of polyG–polyC and polyA–polyT DNA duplexes in solution. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 16 265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, W.D., Cieplak, P., Bayly, C.I., and Kollman, P.A. 1993. Application of RESP charges to calculate conformational energies, hydrogen bond energies, and free energies of solvation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 9620–9631. [Google Scholar]

- Dauber-Osguthorpe, P.L., Roberts, V.A., Osguthorpe, D.J., Wolff, J., Genest, M., and Hagler, A.T. 1988. Structure and energetics of ligand-binding to proteins: Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase trimethoprim, a drug receptor system. Proteins 4 31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, L., Luo, R., and Gilson, M.K. 2000. Comparison of generalized Born and Poisson models: Energetics and dynamics of HIV protease. J. Comput. Chem. 21 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Donini, O.A.T. and Kollman, P.A. 2000. Calculation and prediction of binding free energies for matrix metalloproteinases. J. Med. Chem. 43: 4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, S.R., Cortis, C., Shenkin, P.S., and Friesner, R.A. 1997. Solvation free energies of peptides: Comparison of approximate continuum solvation models with accurate solution of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Phys. Chem. B 101 1190–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Essmann, U., Perera, L., Berkowitz, M.L., Darden, T., Lee, H., and Pedersen, L.G. 1995. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R., Zakrzekski, V.G., Montgomery, J.A., Stratmann, R.E., Burant, J.C., et al. 1998. Gaussian 98. Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, PA.

- Gelin, B.R. and Karplus, M. 1975. Sidechain torsional potentials and motion of amino acids in proteins: Bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 72 2002–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, M.K. and Honig, B. 1988. Calculation of the total electrostatic energy of a macromolecular system: Solvation energies, binding energies and conformational analysis. Proteins 4 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, M.K., Sharp, K.A., and Honig, B.H. 1987. Calculating the electrostatic potential of molecules in solution: Method and error assessment. J. Comput. Chem. 9 327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer, C.T., von Itzstein, M., Jin, B., Pegg, M.S., Stewart, W.P., and Wu, W.-Y. 1993. Inhibition of sialidases from viral, bacterial and mammalian sources by analogs of 2-deoxy-2,3-didehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid modified at the C-4 position. Glycoconj. J. 10 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, S., Wang, J., Cioslowski, J., Kollman, P.A., and Kuntz, I.D. 2002. Molecular dynamics and free energy analyses of cathepsin D–inhibitor interactions: Insight into structure-based ligand design. J. Med. Chem. 45 1412–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, T., Guo, S., and Xu, X. 2002. Predictions of binding of a diverse set of ligands to gelatinase-A by a combination of molecular dynamics and continuum solvent models. J. Phys. Chem. 106 5527–5535. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram, B., Sprous, D., and Beveridge, D.L. 1998. Solvation free energy of biomolecules: Parameters for a modified generalized Born model consistent with the AMBER force field. J. Phys. Chem. B 102 9571–9576. [Google Scholar]

- Jedrzejas, M.J., Singh, S., Brouillette, W.J., Air, G.M., and Luo, M. 1995. A strategy for theoretical binding constant, Ki, calculations for neuraminidase aromatic inhibitors designed on the basis of the active site structure of influenza virus neuraminidase. Proteins 23 264–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W.L. 1989. Free energy calculations: A breakthrough for modelling organic chemistry in solution. Acc. Chem. Res. 22 184–189. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, W.L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J.D., Impey, R.W., and Klein, M.L. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, P., Reddy, T.V., and Jayaram, B. 2002. Free energy component analysis for drug design: A case study of HIV-1 protease-inhibitor binding. J. Med. Chem. 44 4325–4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearsley, S.K. 1989. On the orthogonal transformation used for structural comparisons. Acta Crystallogr. A 45 208–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, B. and Kollman, P.A. 2000a. Binding of a diverse set of ligands to avidin and streptavidin: An accurate quantitative prediction of their relative affinities by a combination of molecular mechanics and continuum solvent models. J. Med. Chem. 43 3786–3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2000b. A ligand that is predicted to bind better to avidin than biotin: Insights from computational fluorine scanning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 3909–3916. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.R., Duan, Y., and Kollman, P.A. 2000. Use of MM-PB/SA in estimating the free energies of proteins: Application to native, intermediates, and unfolded villin headpiece. Proteins 39 309–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra, V.K., Hecht, J.L., Sharp, K.A., Friedman, R.A., and Honig, B. 1994. Salt effects on ligand-DNA binding : Minor groove binding antibiotics. J. Mol. Biol. 238 245–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadi, F., Richards, N.G., Guida, W.C., Liskamp, R., Caufield, C., Chang, G., Hendrickson, T., and Still, W.C. 1990. Macromodel: An integrated software system for modelling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 11 440–467. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, C.M. and Kollman, P.A. 2000. Structure and thermodynamics of RNA–protein binding: Using molecular dynamics and free energy analyses to calculate the free energies of binding and conformational change. J. Mol. Biol. 297 1145–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert, J.P., Ciccotti, G., and Berendsen, H.J.C. 1977. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sanner, M.F., Olson, A.J., and Spehner, J.C. 1996. Reduced surface: An efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers 38 305–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M., Bartels, C., and Karplus, M. 1999. Solution conformations of structured peptides: Continuum electrostatics versus distance-dependent dielectric functions. Theor. Chem. Acc. 101 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. and Wendoloski, J. 1996. Electrostatic binding energy calculation using the finite difference solution to the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation: Assessment of its accuracy. J. Comput. Chem. 17 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Sitkoff, D., Sharp, K.A., and Honig, B. 1994. Accurate calculation of hydration of free energies using macroscopic solvent models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 1978–1988. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.J. and Hall, N.E. 1999. Solvation parameters for amino acids. J. Comput. Chem. 20 428–442. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.J., Colman, P.M., von Itzstein, M., Daylec, B., and Varghese, J.N. 2001. Analysis of inhibitor binding in influenza virus neuraminidase. Protein Sci. 10 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, J., Cheatham, T.E., Cieplak, P., Kollman, P.A., and Case, D.A. 1998. Continuum solvent studies of the stability of DNA, RNA and phosphoramidate-DNA helices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 9401. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, J., Trevathan, M.W., Beroza, P., and Case, D.A. 1999. Application of a pairwise generalized Born model to proteins and nucleic acids: Inclusion of salt effects. Theor. Chem. Acc. 101 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Still, W.C., Tempczyk, A., Hawley, R.C., and Hendricksen, T.J. 1990. Semi-analytical treatment of solvation for molecular mechanics and dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 6129. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N.R. and von Itzstein, M. 1996. A structural and energetics analysis of the binding of a series of N-acetylneuraminic-acid–based inhibitors to influenza virus sialidase. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 10 233–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, V. and Case, D.A. 2001. Molecular dynamics simulations of nucleic acids using a generalized Born solvation model. Biopolymers 56 275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, J.N., Epa, V.C., and Colman, P.M. 1995. Three-dimensional structure of the complex of 4-guanidino-neu5ac2en and influenza virus neuraminidase. Protein Sci. 4 1081–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Itzstein, M., Dyason, J.C., Oliver, S.W., White, H.F., Wu, W.-Y., Kok, G.B., and Pegg, M.S. 1996. A study of the active site of influenza viral sialidase: An approach to the rational design of novel anti-influenza drugs. J. Med. Chem. 39 388–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall, I.D., Leach, A.R., Salt, D.W., Ford, M.G., and Essex, J.W. 1999. Binding constants of neuraminidase inhibitors: An investigation of the linear interaction energy method. J. Med. Chem. 42 5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Cieplak, P., and Kollman, P.A. 2000. How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 21 1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Morin, P., Wang, W., and Kollman, P.A. 2001. Use of MM-PBSA in reproducing the binding free energies to HIV-1 RT of TIBO derivatives and predicting the binding mode to HIV-1 RT of efavirenz by docking and MM-PBSA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 5221–5230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. and Wade, R.C. 2003. Implicit docking models for flexible protein–protein docking by molecular dynamics simulation. Proteins 50 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.J., King, M.A., and Essex, J.W. 2001. The configurational dependence of binding free energies: A Poisson-Boltzmann study of neuraminidase inhibitors. J. Comput. Mol. Des 15 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]