Abstract

We have recently reported on the design of a 20-residue peptide able to form a significant population of a three-stranded up-and-down antiparallel β-sheet in aqueous solution. To improve our β-sheet model in terms of the folded population, we have modified the sequences of the two 2-residue turns by introducing the segment DPro-Gly, a sequence shown to lead to more rigid type II′ β-turns. The analysis of several NMR parameters, NOE data, as well as ΔδCαH, ΔδCβ, and ΔδCβ values, demonstrates that the new peptide forms a β-sheet structure in aqueous solution more stable than the original one, whereas the substitution of the DPro residues by LPro leads to a random coil peptide. This agrees with previous results on β-hairpin-forming peptides showing the essential role of the turn sequence for β-hairpin folding. The well-defined β-sheet motif calculated for the new designed peptide (pair-wise RMSD for backbone atoms is 0.5 ± 0.1 Å) displays a high degree of twist. This twist likely contributes to stability, as a more hydrophobic surface is buried in the twisted β-sheet than in a flatter one. The twist observed in the up-and-down antiparallel β-sheet motifs of most proteins is less pronounced than in our designed peptide, except for the WW domains. The additional hydrophobic surface burial provided by β-sheet twisting relative to a “flat” β-sheet is probably more important for structure stability in peptides and small proteins like the WW domains than in larger proteins for which there exists a significant contribution to stability arising from their extensive hydrophobic cores.

Keywords: NMR, β-turn, β-sheet stability, β-sheet structure, β-sheet twist, peptide design

Unravelling the factors involved in β-sheet folding and stability is a subject of great current interest because of the relevance of this knowledge to advance in the successful prediction of protein structure from amino acid sequence, which is crucial in the field of structural genomics. It will also contribute to improve our understanding of the mechanisms of amyloidgenesis, that is, the formation of amyloid fibrils present in conformational diseases, such as Alzhei-mer’s and spongiform encephalopathies (Kelly 2000; Gorman and Chakrabartty 2001). The conformational study of protein fragments and designed peptides able to adopt β-sheet motifs, a fruitful approach in the case of helices (Parthasarathy et al. 1995; Aurora and Rose 1998; Rohl and Baldwin 1998; Serrano 2000), was hindered by the high tendency to aggregate of the sequences containing good β-sheet forming residues, most of which are hydrophobic. However, the field of β-sheet peptide conformational studies changed during the last decade, when the efforts of several groups led to the successful design of water-soluble peptides able to form monomeric β-hairpins, that is, two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet structures (for review, see Smith and Regan 1997; Blanco et al. 1998; Gellman 1998; Lacroix et al. 1999; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 1999; Serrano 2000). Several factors contributing to β-hairpin formation, that is, intrinsic amino acid β-turn and β-sheet tendencies, hydrogen-bonding network, interstrand side-chain–side-chain interactions, and hydrophobic clusters were identified from the analysis of the conformational behavior of those peptides (Smith and Regan 1997; Blanco et al. 1998; Gellman 1998; Lacroix et al. 1999; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 1999, 2001; Santiveri et al. 2000; Serrano 2000; Espinosa et al. 2001; Syud et al. 2001, 2003; Blandl et al. 2003; Russell et al. 2003). Following the success with β-hairpin structures, several designed peptides were reported to adopt more complex antiparallel β-sheets, mostly three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets (Das et al. 1998; Kortemme et al. 1998; Schenck and Gellman 1998; Sharman and Searle 1998;de Alba et al. 1999a, b; Griffiths-Jones and Searle 2000; Chen et al. 2001; López de la Paz et al. 2001; Santiveri et al. 2003; Syud et al. 2003) and even four-stranded β-sheets (Das et al. 1999, 2000; Syud et al. 2003), in a monomeric state.

To gain further insight into the factors involved in the formation and stability of the antiparallel β-sheets, we focused on enhancing the stability of the three-stranded β-sheet-forming peptide designed in our lab (Peptide BS1; de Alba et al. 1999b; Fig. 1 ▶). Taking into account the relevant role that the β-turn region plays in β-hairpin folding (de Alba et al. 1996, 1997a, b, 1999a; Haque and Gellman 1997; Muñoz et al. 1997, 1998; Griffiths-Jones et al. 1999; Blandl et al. 2003), we decided to start by optimizing the turn sequences. After considering the successful strategy developed by the groups of Gellman (Haque and Gellman 1997) and Balaram (Karle et al. 1996; Das et al. 1998; Kaul and Balaram 1999) for β-hairpin stability consistent in introducing the sequence dPG into the turn, we substituted the GS sequence in the two turns of our design peptide by the pair dPG (Fig. 1 ▶). As a control, the conformational behavior of a peptide with lPG sequences at the two turns (Peptide BS3; Fig. 1 ▶) was also investigated.

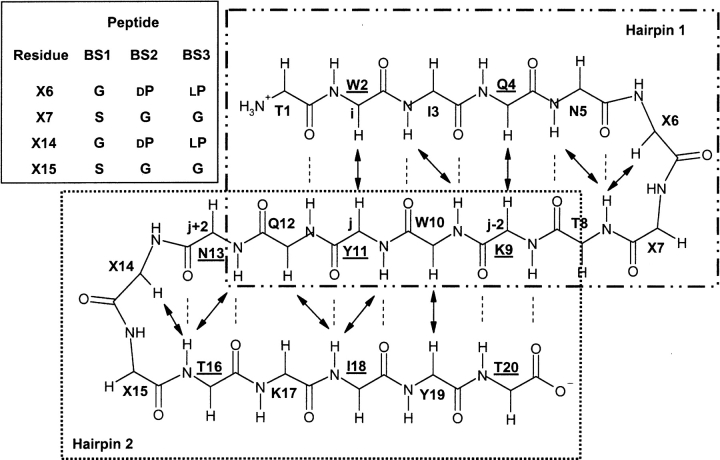

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the peptide backbone conformation of the three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet motif adopted by peptide BS1 (de Alba et al. 1999b) and expected for peptide BS2. Turn residues are indicated by “X.” Turn residues for peptides BS1 and BS2 as well as for the control peptide BS3 are shown in the inset. β-Strand residues whose side chains are oriented upward of the β-sheet plane are underlined. All other side chains of β-strand residues are downward. β-Sheet hydrogen-bonds are indicated by dotted lines linking the NH proton and the acceptor CO oxygen. The long-range NOEs involving backbone CβH and NH protons observed for peptide BS2 in aqueous solution are shown by black arrows. The two large rectangles surround residues belonging to each of the two β-hairpins that compose the β-sheet motif. Interstrand diagonal NOEs are defined as those between residue i at one strand and either residue j − 2 or residue j + 2 at the adjacent strand. As an example, W2, K9, and N13 are labeled as i, j − 2, and j + 2, respectively.

Results

Peptides BS2 and BS3 are monomers

The monomeric states of peptides BS2 and BS3 in aqueous solution were evidenced by the absence of any significant change in line widths and chemical shifts between 1D 1H NMR spectra recorded at 0.1 and 1 mM, the concentration used for acquisition of two-dimensional 1H and 13C NMR spectra. In addition, the average molecular weight (Mav) obtained from sedimentation equilibrium experiments carried out with dilute samples of the two peptides, and the molecular weights calculated from the amino acid composition (Mth) are very similar (Mav/Mth is 0.99 and 1.00 for peptides BS2 and BS3, respectively).

Peptide BS2 adopts a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet structure

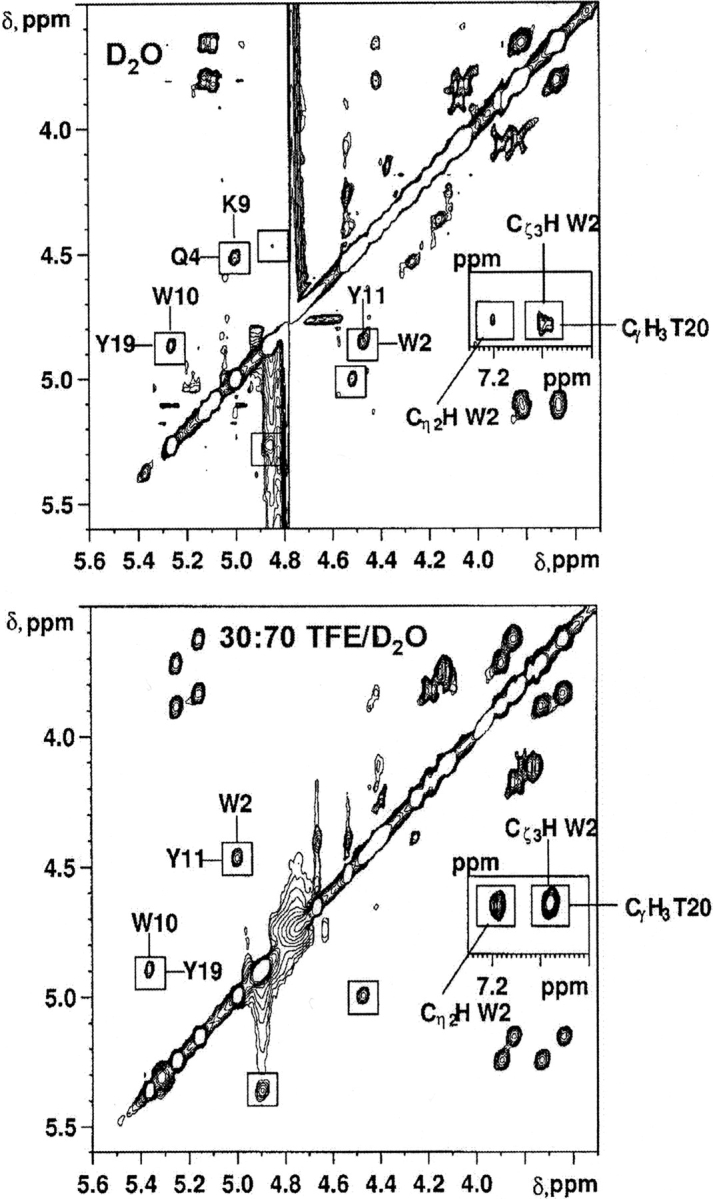

To assess whether peptide BS2 adopts the target β-sheet structure (Fig. 1 ▶), we have analyzed several NMR parameters, including NOE data and CαH, 13Cα, and 13Cβ conformational shifts (Δδ= δobserved − δrandom coil), in aqueous solution and in 30% TFE. Most of the NOEs involving backbone protons of residues in the hydrogen-bonded β-strands expected for the target β-sheet structure were observed for peptide BS2 in aqueous solution and in 30% TFE (Figs. 1 ▶ and 2 ▶; Table 1). A large number of NOEs involving side-chain protons of residues at adjacent strands on the same side of the β-sheet were also observed. A few characteristic NOEs were not observed, because they lie very near to the diagonal in the NOESY spectra (i.e., the CαH Q12-CαH K17 NOE) or overlap with other cross-peaks. Although the set of NOEs is compatible with the target β-sheet structure, it is not sufficient to demonstrate the β-sheet’s existence, because the NOE pattern is also compatible with the equilibrium among two independent β-hairpins (either hairpin 1 or hairpin 2; Fig. 1 ▶) and the random coil state (de Alba et al. 1999b). However, the presence of two long-range NOEs involving aromatic protons of W2 and methyl protons of T20 (Fig. 2 ▶; Table 1), residues located in the edge strands of the β-sheet (Fig. 1 ▶), does demonstrate the formation of the desired three-stranded β-sheet. These two NOEs are more intense in 30% TFE than in aqueous solution (Fig. 2 ▶), which indicates that peptide BS2 adopts a same β-sheet structure in the presence or absence of TFE, but with an increased population in the alcoholic mixture.

Figure 2.

Selected regions of the NOESY spectra of peptide BS2 in D2O (top) and in 30 : 70 TFE/D2O (bottom) at pH 3.5 and 25°C. Interstrand CαH-CαH NOE cross-peaks are labeled and boxed. The long-range NOEs between side-chain protons of residues W2 and T20 are shown in the inset.

Table 1.

Total number of NOE connectivities involving side-chain protons observed for peptide BS2 in aqueous solution and in 30% TFE

| NOE | Water | 30% TFE |

| Sc-sc of a residue at the first strand and a residue at the third stranda,b | 2 | 2 |

| Sc-sc and sc-bb of facing i,j residuesa | 49 | 64 |

| Sc-sc and sc-bb of i, i + 2 residuesa | 36 | 34 |

| Sc-sc of diagonal i, j ± 2 residuesa | 41 | 41 |

| Sc-bb involving other residues than i,j or i,i + 2a | 12 | 12 |

The profiles of the ΔδCαH, ΔδCα, and ΔδCβ conformational shift values provide additional evidence of the formation of the target β-sheet by peptide BS2. Excluding the residues at the amino- and carboxy-termini, which may be affected by charge-end effects, the profiles experimentally found for peptide BS2 in aqueous solution are consistent with those characteristic of a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (Spera and Bax 1991; Wishart et al. 1991; Santiveri et al. 2001), three stretches of residues with negative ΔδCα values, and positive ΔδCαH and ΔδCβ values (all of which have a large absolute value) corresponding to the β-strands (residues 1–5, 8–13, and 16–20; Fig. 1 ▶). These stretches are separated by two regions corresponding to the two β-turns (residues 6–7 and 14–15; Fig. 1 ▶) that exhibit small ΔδCαH values and at least one residue with a positive ΔδCα value and a negative ΔδCβ value (residues 6 and 14; Fig. 1 ▶). The only deviations from the characteristic β-sheet pattern are the ΔδCαH values observed for residues I3, Y11, and I18, and the ΔδCα values obtained for T8 (with a null value), T16 and Y19 residues (Fig. 3 ▶). The fact that residues I3, Y11, and I18 are adjacent to aromatic residues and face them in the target β-sheet (Fig. 1 ▶), being thus affected by their ring current effects, accounts for their negative ΔδCαH values (instead of the positive values expected for strand residues), as has been observed in some β-hairpin-forming peptides (de Alba et al. 1996; Santiveri et al. 2000). Regarding the two turns (residues 6–7 and 14–15; Fig. 1 ▶), the patterns observed in peptide BS2 (positive ΔδCα values and negative ΔδCβ values for dP6 and dP14, and small positive ΔδCα values for G7 and G15; Fig. 3 ▶) are compatible with either the target type II′ β-turn or a type I′ β-turn (Santiveri et al. 2001). These two types of β-turn lead to identical strand register. The profiles observed in aqueous and in 30% TFE differ in the magnitude of the values; they are larger in absolute value in 30% TFE, especially in the β-strand residues. This is clear-cut evidence that, as indicated by NOE data (see above), a same β-sheet structure is adopted by peptide BS2 in the presence or absence of TFE, but its population is larger in the alcoholic mixture. This result corroborates earlier studies (de Alba et al. 1995, 1996, 1997a,de Alba et al. b; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 1997; Maynard et al. 1998; Andersen et al. 1999; López de la Paz et al. 2001) that showed TFE, as a cosolvent, stabilizes β-sheet structures and not just helices, as was generally believed.

Figure 3.

Histograms of ΔδCαH (top), ΔδCα (middle), and ΔδCβ (bottom) values as a function of sequence for peptide BS2 in D2O (white bars) and in 30 : 70 TFE/D2O (black bars) at pH 3.5 and 25°C, and for control peptide BS3 (gray bars) in D2O at pH 3.5 and 25°C. δCαHrandom coil values were taken from Bundi and Wüthrich (1979) and δCαrandom coil and δCβrandom coil values from Wishart et al. (1995a). For Gly, the averaged ΔδCαH value is shown. Residue P is a D-amino acid in peptide BS2 and a L-amino acid in control peptide BS3. Strand and turn regions are indicated at top. Turn residues are boxed.

On the basis of the average ΔδCαH, ΔδCα, and ΔδCβ values for the strand residues (Materials and Methods; Santiveri et al. 2001) the β-sheet population of peptide BS2 at pH 3.5 and at 25°C is estimated as 61% in aqueous solution and 79% in 30% TFE (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated β -sheet populations for peptides BS1 and BS2 in D2O at pH 3.5 and 25° C and for peptide BS2 in 30:70 TFE/D2O and free energy variation (ΔGu) for β-sheet unfolding in D2O

| Peptide BS2 in D2O | Peptide BS2 in 30% TFE | Peptide BS1ain D2O | |

| β-Sheet population | |||

| % from ΔδCαHb | 78 (+0.31 ppm) | 100 (+0.49 ppm) | 20 (+0.08 ppm) |

| % from ΔδCαb | 48 (−0.77 ppm) | 61 (−0.98 ppm) | 30 (−0.48 ppm) |

| % from ΔδCβb | 56 (+0.95 ppm) | 76 (+1.30 ppm) | 14 (+0.23 ppm) |

| Averaged %c | 61 ± 16, 59 ± 14 | 79 ± 20 | 21 ± 8, 17 ± 9 |

| ΔGu, kcal mole−1,d,e | +0.3 ± 0.4, +0.2 ± 0.3 | — | −0.8 ± 0.3, −0.9 ± 0.4 |

| Δ ΔGBS2 vs BS1, kcal mole−1,e,f | +1.1 ± 0.5, +1.1 ± 0.5 | ||

| Δ Δ GdPG vs GS, kcal mole−1,e,g | +0.6 ± 0.5, +0.6 ± 0.5 | ||

| ΔGop10°C, kcal mole−1,h,i | +0.2 ± 0.2 (+0.4 ± 0.1j) | ||

a Evaluated as described for peptide BS2 on the basis of the δ-values previously reported. (de Alba et al. 1999b).

b The corresponding Δδ value obtained as the averaged value for strand residues, excluding the N- and C-terminal residues and the residues adjacent to the β-turns, is given in parenthesis. Those residues with a Δ δCαH or with a Δ δCαH-value deviating from the expected for a β-strand were also excluded (see Materials and Methods).

c Averaged β-sheet population obtained as the mean value of the three independent-estimations based on Δ δCαH, Δ δCα, and Δ δCβ values. β-Sheet populations estimated at 10°C are given in italics. Reported errors are the standard deviations.

d Obtained from the estimated β-sheet populations by assuming a two-state β-sheet folding-unfolding equilibrium and applying the equations: ΔGu = −RT ln Keq.

e Errors were estimated by error propagation analysis.

f Δ Δ GBS2 vs BS1 = ΔGBS2 − ΔGBS1.

G Δ ΔGdPG vs GS = ½ Δ ΔGBS2 vs BS1.

h Obtained from the H/D exchange rates of the eight most protected amide protons for peptide BS2 in aqueous solution at pH 3.5 and 10°C (Table ST6) and applying the correction for taking into account the effect of the cis-trans equilibrium of the two Pro residues (Materials and Methods).

i Reported errors are the standard deviations.

j Considering only the five most protected amide protons (Table ST6).

Control peptide BS3 in aqueous solution is a mainly random coil peptide

In contrast to peptide BS2, most of the observed NOEs in the NOESY spectrum of peptide BS3 in aqueous solution were intraresidual or sequential (data not shown). The only nonsequential NOEs were a few very weak i, i+2 NOEs involving side-chain protons of residues with aromatic rings and long side chains that may arise from some low-populated local nonrandom conformations. None of the NOEs expected for the target β-sheet structure or for any other antiparallel β-sheet (with different strand alignments) are observed. The fact that the CαH and Cβ conformational shifts observed for the control peptide BS3 (Fig. 3 ▶) are very small in absolute value and mostly negative, in contrast to the positive sign characteristic of β-strands, also indicates the absence of any β-sheet structure. The negative ΔδCαH values of I3-Q4 and Y11-Q12, relatively large in absolute value (|ΔδCαH|>0.15 ppm), which would suggest the existence of some low populated helix regions (Fig. 3 ▶) are probably due to the anisotropy effect of the aromatic rings of residues W2, W10, and Y11 (Wintjens et al. 2001; Pajon et al. 2002). In regard to the Cα conformational shifts (Fig. 3 ▶), the negative and large magnitude ΔδCα values of the N5 and N13 residues are characteristic of Pro-preceding amino acids (Wishart et al. 1995a; Wintjens et al. 2001; Pajon et al. 2002). Some other residues corresponding to the β-strands in peptide BS2 display negative ΔδCα values, but they are generally small in magnitude. They could also be an indication of some β-sheet tendency, as have been found in isolated strands of a designed β-hairpin (Maynard et al. 1998). Nevertheless, on the whole, peptide BS3 in aqueous solution behaves as an essentially random-coil peptide.

CD data for peptide BS2 and for control peptide BS3

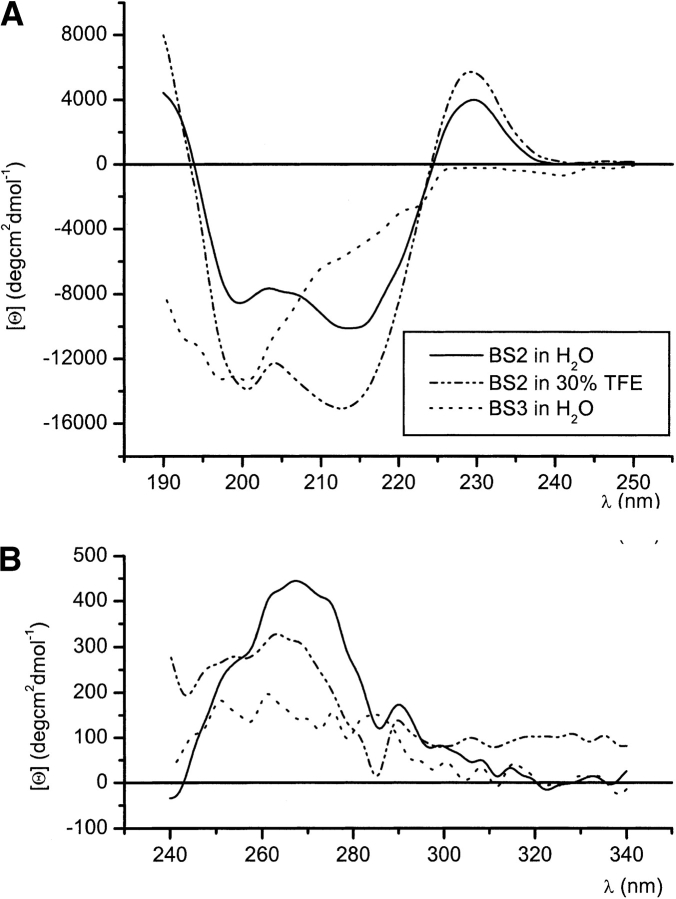

The far-UV CD spectra of peptide BS2 in aqueous solution and in the mixed solvent 30 : 70 TFE/H2O (Fig. 4 ▶) display a minimum at ~214 nm, which is characteristic of β-sheet structures (Johnson Jr. 1988) and a maximum at ~230 nm, which is ascribable to contributions from the aromatic residues (W2, W10, Y11, Y19; Johnson Jr. 1988; Woody 1995). The positive values below 195 nm are also indicative of β-sheet structure, as β-sheets have a maximum about 195 nm. Using the CDPro program (Sreerama and Woody 2000), the best fits of these CD spectra give β-sheet populations of 82% and 92% (including regular and distorted β-sheets and turn) and random coil populations of 18% and 8% in aqueous solution and 30% TFE, respectively. The far-UV CD spectrum of the control peptide BS3 in aqueous solution (Fig. 4 ▶) differs greatly from that of peptide BS2 and is indicative of a disordered peptide. The best fit of this CD spectrum using the CDPro program (Sreerama and Woody 2000) yields a random coil population of 61%. These results are in excellent agreement with our previous conclusions from NMR parameters.

Figure 4.

Far-UV (A) and near-UV (B) circular dichroism spectra of pep-tides BS2 in H2O (continuous line) and in 30 : 70 TFE/H2O (dotted/dashed line) at pH 3.5 and 10°C, and for control peptide BS3 (dotted line) in H2O at pH 3.5 and 10°C.

More interestingly, the near-UV CD spectra of peptide BS2 shows a positive broad band centered at ~270 nm in aqueous solution and at ~265 nm in 30% TFE, whereas peptide BS3 in aqueous solution displays a nearly flat near-UV CD spectrum, as observed in most peptides (Fig. 4 ▶). These signals arise from the aromatic side chains of the two Trp and two Tyr residues present in peptide BS2 and from the interactions between a Trp and a Tyr side chain in each pair of facing Trp and Tyr residues (W2-Y11 and W10-Y19; Fig. 1 ▶; Strickland 1974; Woody and Dunker 1996). They clearly indicate that aromatic side chains in the anti-parallel β-sheet adopted by peptide BS2 are well ordered.

Stability of the β-sheet formed by peptide BS2

Peptides adopting a single structure should approach the cooperative thermal unfolding transition usually observed in protein structures. In that case, thermodynamic parameters (ΔGu, ΔHu, ΔSu, and even ΔCp0) can be obtained for the folded–unfolded transition, as has been done for some β-sheet-forming peptides (Santiveri et al. 2002). The 1H chemical shifts of all nonexchangeable protons of peptide BS3 exhibit a linear temperature dependence within the 0–80°C range (r-values > 0.95), and a very small total change in δ-value between the highest and the lowest temperatures (|Δδ| ≤ 0.10 ppm, in which Δδ = δ0° − δ80°, ppm), as expected for a random coil peptide (Santiveri et al. 2002). In contrast, many protons of peptide BS2 experience a large total change in δ-value (|Δ δ| ≥ 0.10 ppm; Table ST5) and a nonlinear thermal dependence (Fig. 5 ▶). The shape of the δ versus T curves is reminiscent of a broad sigmoidal curve, where the plateau corresponding to the unfolded state has not been reached (Fig. 5 ▶). Even at 80°C, the curve is still far away from the unfolded state plateau (40% β-sheet population as estimated from Δ δCαH), which precludes a complete thermodynamic analysis because of the large correlation errors among the different thermodynamic parameters.

Figure 5.

Thermal dependence of the δ-values of several protons and of the splitting of CαH and Cα′H Gly protons (ΔδGly) of peptide BS2 in D2O at pH 3.5. Error for each experimental point is ±0.01ppm. Experimental points are linked with a line to guide the eye.

To characterize quantitatively one particular factor contributing to β-sheet stability, it is always useful to have a value of the unfolding free energy at a given temperature (298 K). The simplest thing is to consider a two-state unfolding equilibrium, for which the free energy is given by ΔGu = − RT ln Keq. The adoption of a two-state model is justified as follows. The profile of the temperature dependence of the splitting between the CαH and Cα′H protons of Gly residues in β-turns (ΔδGly = δCαH − δCα′H, ppm) has been taken as a diagnostic of the formation of the corresponding β-hairpin (Griffiths-Jones and Searle 2000). The profiles of G7 and G15 in BS2 show an identical behavior, except for a small shift in magnitude ascribable in principle to sequence differences (see Fig. 5 ▶, bottom right). Because G7 belongs to the amino-terminal β-hairpin and G15 to the carboxy-terminal one, that behavior indicates that the folding of the two hairpins is simultaneous, and consequently, the folding of the entire β-sheet occurs as a two-state transition. This is in contrast to that reported for a three-stranded β-sheet design (Griffiths-Jones and Searle 2000), for which a four-state folding pathway was proposed, because the profiles of thermal unfolding of the two β-turns as monitored by the ΔδGly splittings were completely different. Values of ΔGu obtained from the estimated populations in peptide BS2 for a two-state model are given in Table 2.

The NH/ND exchange rates (kex) could be measured for a total of 14 amide protons in peptide BS2 and 10 in peptide BS3 (see Materials and Methods; Supplemental Table ST6). In the case of the control peptide BS3, all exchange at approximately their intrinsic exchange rate or even faster (log P ≤ 0; Supplemental Table ST6), as expected for a random-coil peptide. In contrast, eight of the amide protons in peptide BS3 exhibit slower exchange rates than their intrinsic ones (log P >0.2; Supplemental Table ST6), although the degree of protection is small. The free energy change for β-sheet unfolding evaluated by assuming, as done in proteins (Wagner and Wüthrich 1979; Jeng and Dyson 1995; Woodward 1995; Englander et al. 1996), that the exchange of the most protected amide protons occurs by complete unfolding of the peptide structure is in excellent agreement with that obtained on the basis of the estimated β-sheet population (Table 2).

The β-sheet structure adopted by peptide BS2 displays a large right-handed twist

To further characterize the β-sheet adopted by peptide BS2, we have determined its structure in aqueous solution and in 30% TFE by using distance restraints derived from the intensities of the long-range, medium-range, and sequential CαHi-NHi+1 NOEs (159 and 169, respectively) and dihedral φ angle constraints for residues exhibiting 3JCαH-NH > 8 Hz (9 and 12, respectively). Intraresidual and sequential NOEs, apart from the CαHi-NHi+1 NOEs, were excluded due to the contribution of random coil conformations to their intensities. This contribution is negligible in the case of the se-quential CαHi-NHi+1 NOEs because of their short distance, 2.2 Å, in the β-sheet conformation. The resulting structures are well defined in both water and 30% TFE (Fig. 6 ▶; pairwise RMSD values for backbone atoms are 0.6 ± 0.2 Å and 0.5 ± 0.1 Å, respectively) and the side chains of most residues at the strands are also well defined (pairwise RMSD values for all heavy atoms are 1.1 ± 0.2 Å and 1.0 ± 0.2 Å, respectively). The close agreement of the values displayed by the χ1 and χ2 angles of the ordered side chains in water and in 30% TFE (Table ST7) is evidence of the similarity of the structures adopted in both solvents, as concluded from the qualitative analysis of the NMR parameters. Accordingly, the pair-wise RMSD values of the structure ensemble including the best 20 in water and the best 20 in 30% TFE calculated structures (0.8 ± 0.3 Å for backbone atoms and 1.2 ± 0.3 Å for all heavy atoms) are only slightly higher than the RMSD values obtained for each solvent individually.

Figure 6.

Stereoscopic view of the superposition of all heavy atoms of the best 20 structures calculated for the β-sheet motif formed by peptide BS2 in aqueous solution. Backbone (in black) and side-chain atoms (in red) are displayed at top, and only backbone atoms in the middle. (Bottom) The backbone atoms of the best 20 structures calculated for the β-sheet motif adopted by peptide BS2 (in black) and for a prototype WW domain (in blue; PDB code: 1e0m; Macías et al. 2000) superimposed over the backbone atoms of the β-strands. The “C” label indicates the carboxy-termini.

The calculated structures appear very twisted by visual inspection (Fig. 6 ▶), and in fact, the overall degree of twist is 43 ± 3°, 39 ± 2°, and 82 ± 4° between strands 1–2, 2–3, and 1–3, respectively (see Materials and Methods). The corresponding values for a model of the “ideal” up-and-down three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet structures with two type II′ β-turns are 9 ± 5°, 7 ± 3°, and 9 ± 7°.

To investigate the distance constraints responsible for the β-sheet twist, we classified the NOEs involving side-chain protons into three groups as follows: (1) diagonal i, j ± 2 (see Fig. 1 ▶) plus those between first and third strand; (2) i, i+2 residues; and (3) side-chain backbone other than i, j, or i, i+2 residues (Table 1; Supplemental Table ST4). We performed seven additional structure calculations by excluding each group individually, then pairs of groups, and then finally, the three groups. We observed that the twist mainly originates from the NOEs of group 1, followed by those of group 2. Nevertheless, even the flattest calculated structure (that excluding the three groups) is more twisted than the models for the “ideal” up-and-down three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet structures with either type I′ or type II′ β-turns (the flattest of all). Using this series of structures (10 sets in total), we found that the degree of twist (overall degree of twist between strands 1–3) correlates with the buried hydrophobic surface and with the total buried surface, with the r-values being 0.89 and 0.94, respectively.

Comparison of the three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet adopted by peptide BS2 with the same motif in protein structures

Although it is well known that protein β-sheets usually display a right-handed twist (Richardson 1981), the large degree of twist displayed by the β-sheet structures calculated for peptide BS2 (see above; Fig. 6 ▶) prompted us to examine three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet motifs of proteins. We found that the degree of twist between the first and the third strand (Materials and Methods) in 10 three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets of a few proteins (145–436 residues) is in the range of 27° to 60°, whereas in noncomplexed WW domains (27–39 residues of length; Supplemental Table ST8), it amounts to 84° to 97°. Although these results do not constitute a thorough statistical examination of the three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet motif in proteins, they suggest that antiparallel β-sheets are less twisted in large proteins than in the peptide BS2 or than in smaller proteins, such as the WW domains.

Because the lengths of the three β-strands constituting the β-sheet motif in the designed peptide BS2 and in the WW domains are the same, we investigated whether any sequence similarity exists between the designed peptide BS2 and the WW domains by performing a manual structural alignment between them (Table 3). Considering the WW domains of known three-dimensional structures in their free state, we found that three β-strand positions are occupied by either aromatic or hydrophobic residues in both WW domains and in peptide BS2 (10, 11, and 19), and one by a N residue (position 13), which is in peptide BS2 and in some of the WW domains is facing a T residue (position 16). Residues at positions 10 and 19 are among those conserved in WW domains. The sequence of peptide BS2 exhibits the highest similarity with the WW domain from YJQ8 yeast (Macías et al. 2000), in which positions 2, 3, and 18 are occupied by hydrophobic or aromatic residues, and position 17 by a K residue. However, peptide BS2 lacks the residues preceding the amino-terminal strand (P and W) and those following the carboxyterminal strand (P), which have been shown to contribute to the stability of WW domains (Macías et al. 2000). It is also interesting to note the good matching of the backbone atoms of the β-sheet adopted by peptide BS2 to the template derived from WW domains (Fig. 6 ▶).

Table 3.

Structural sequence alignment of the designed peptide BS2 with noncomplexed WW domains of known three-dimensional structure

| β1 | β2 | β3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pdba | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |||||||||||

| BS2b | T | W | I | Q | N | DP | G | T | K | W | Y | Q | N | dP | G | T | K | I | Y | T | |||||||||||

| 1e0mc | L | P | P | G | W | D | E | Y | K | T | H | N | G | K | T | Y | Y | Y | N | H | N | T | K | T | S | T | W | T | D | P | |

| 1i6cd | L | P | P | G | W | E | K | R | M | S | R | S | S | G | R | V | Y | Y | F | N | H | I | T | N | A | S | Q | W | E | R | P |

| 1e01e | A | V | S | E | W | T | E | Y | K | T | A | D | G | K | T | Y | Y | Y | N | N | R | T | L | E | S | T | W | E | K | P | |

| 1e0nf | L | P | P | G | W | E | I | I | H | E | N | G | R | P | L | Y | Y | N | A | E | Q | K | T | K | L | H | Y | P | P | ||

Residues conserved in WW domains are shown in bold. Residues that are similar in peptide BS2 and in the WW domains are indicated in bold and underlined and those that are similar in the peptide BS2 and in the WW domain from YJQ8 yeast are in italics and underlined. β-Strands and residue numbering in peptide BS2 are indicated at the top. Number of β-strand residues whose side chain are oriented upward and downward the β-sheet plane are in bold and underlined, respectively.

a Pdb code.

b This paper.

c Prototype (Macías et al. 2000).

d Human Pin1_4. (Wintjens et al. 2001).

eFBP28WW mouse (Macías et al. 2000).

fYJQ8 yeast. (Macías et al. 2000).

Discussion

BS1 was the first peptide designed in our group able to adopt a monomeric three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet in aqueous solution (Fig. 1 ▶; de Alba et al. 1999b). The design was based on our previous results in β-hairpin peptides, intrinsic amino acid β-sheet and β-turn propensities, statistically derived pairwise cross-strand side-chain interactions, and solubility criteria. As shown here, the incorporation of DPro residues at the two turns of peptide BS1 greatly stabilizes the three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, increasing its population from 21% in peptide BS1 up to 61% in peptide BS2, and yielding free-energy variation values for β-sheet unfolding (ΔGu) of +0.3 and −0.8 Kcal mole−1, respectively (Table 2). The ΔGu value evaluated for peptide BS2 is in excellent agreement with that obtained from HN/DN exchange data (ΔGop10°C; Table 2), which mutually reinforces their validity. According to the obtained ΔGu values, the β-sheet structure is ~1.1 kcal mole−1 more stable in peptide BS2 than in peptide BS1 (Δ ΔGBS2 vs. BS1; Table 2). Hence, by assuming an independent and additive contribution to stability for each β-turn, the contribution to ΔGu of the dPG turn sequence relative to the GS turn sequence is ~0.6 kcal mole−1 (Δ ΔGdPG vs. GS; Table 2). Despite the many assumptions and the potential error sources implicit in the ΔGu estimation, the resulting value compares reasonably well with some previously reported values that are in the range of from 0.5 to 1.0 kcal mole−1 (Syud et al. 1999; Cochran et al. 2001; Blandl et al. 2003). For example, Δ ΔG of dPG relative to NG in two different β-hairpin peptides is 0.64 kcal mole−1 in a cyclic 10-residue peptide (Cochran et al. 2001) and 0.5 ± 0.1 kcal mole−1 in a linear 12-residue peptide (Syud et al. 1999). They are also within the range reported for the contributions of cross-strand side-chain–side-chain interactions in β-hairpins (de Alba et al. 1995; Searle et al. 1999; Russell and Cochran 2000; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 2001; Stanger et al. 2001).

Substitution of the DPro residues (peptide BS2) by LPro residues (peptide BS3) leads to a complete destabilization of the β-sheet motif, as reported for other β-sheet-forming peptides (Schenck and Gellman 1998). DPro is able to stabilize β-sheets because it fits well into the topology of II′ β-turns that are appropriate for the 2:2 β-hairpins forming the β-sheet motif (Fig. 1 ▶). On the contrary, the LPro-Gly sequence leads to type II β-turns with geometry unsuitable for the β-sheet motif. Our results confirm previous findings in three-stranded antiparallel β-sheets (Schenck and Gellman 1998; Chen et al. 2001) and in β-hairpin peptides (de Alba et al. 1997a,b, 1999a; Haque and Gellman 1997; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 1997, 1999; Smith and Regan 1997; Blanco et al. 1998; Gellman 1998; Lacroix et al. 1999; Serrano 2000) about the relevant role of β-turn sequence in antiparallel β-sheet formation. However, the contribution of appropriate β-turn sequences to β-hairpin stability (~0.5–1.0 kcal mole−1; see above; Cochran et al. 2001) is rather low and is approximately equivalent to one or two favorable cross-strand side-chain interactions (de Alba et al. 1995; Searle et al. 1999; Russell and Cochran 2000; Ramírez-Alvarado et al. 2001; Stanger et al. 2001), which suggests that a suitable β-turn sequence is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of β-sheet motifs containing β-hairpins. As already proposed (Santiveri et al. 2002), the basis for the requirement of appropriate β-turn sequences might stem from the bending of the peptide chain at the turn region to facilitate the packing of the side chains from different strands. Even if the appropriate contact between side chains occurs within the random-coil ensemble, a turn sequence that is incompatible with the β-turn geometry required for β-hairpin formation will prevent β-sheet formation, because its contribution to stability is unfavorable and counterbalances and overpasses favorable stabilizing side-chain interactions. The fact that most antiparallel β-sheets in proteins do not exhibit optimal β-turn sequences can be explained by the presence of a very large number of side-chain interactions. Once the requirement of a suitable turn sequence, or at least a nondestabilizing turn sequence is fulfilled, the formation and final stability of the β-sheet motif will depend on side-chain interactions, reinforced by backbone hydrogen bonds.

The three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet adopted by peptide BS2 exhibits a high degree of right-handed twist. The degree of twist is very similar to that found in small proteins, such as the WW domains, whereas it is more pronounced in three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet motifs in large proteins. Also, the degree of twist appears to correlate with the amount of buried surface. Thus, a large right-handed β-sheet twist will contribute favorably to β-sheet stability by increasing the amount of hydrophobic surface buried. A large twist of the β-sheet is not as important in proteins, where β-sheets are surrounded by segments of the protein, so that at least one of their faces is inaccessible to solvent. However, the two β-sheet faces are solvent exposed in designed β-sheet peptides, or naturally occurring small β-sheet proteins, such as the WW domains. Therefore, the amount of solvent-exposed hydrophobic surface becomes critical for stability, and the additional burial of hydrophobic surface due to a high degree of twist is an important factor for the stability of the β-sheet motif. This is probably the rational basis for previous results on β-hairpin peptides, indicating that the 3:5 β-hairpins, which are more twisted than the 4:4 β-hairpins, are more stable, although no definitive conclusion about the importance of hydrophobic surface burial could be drawn there (de Alba et al. 1997b).

Considering that we made no use at all of WW-domain sequences for the design of peptide BS2 (see above; de Alba et al. 1999b), the remarkable structural similarity of the peptide BS2 and the isolated WW domains (Fig. 6 ▶) merits further analysis. There exists very low-sequence similarity between peptide BS2 and the WW domains, except for one (Table 3). Interestingly, two structurally equivalent positions in peptide BS2 and WW domains (positions 10 and 19) with similar residues correspond to residues conserved in the WW domains and are proposed as important for their stability (Macías et al. 2000). The lack of the conserved stabilizing interaction between the amino-terminal W and the carboxy-terminal P residues in peptide BS2 suggests that this interaction is not essential for β-sheet formation, although it contributes to increase their stability, and could also be related to the binding of Pro-containing sequences to WW domains. Peptide BS2 can serve as a good scaffold to investigate the requirements for peptide binding to WW domains.

Conclusions

The analysis of the ability to adopt a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet by a 20-residue peptide with two dPro-Gly β-turns relative to equivalent peptides with Gly-Ser and lPro-Gly β-turns and of the characteristics of the adopted β-sheet motif (twist and hydrophobic surface burial) gives us insights into several features that are important in β-sheet formation. First, a suitable β-turn sequence is necessary, but not sufficient for the formation of β-sheet motifs containing β-hairpins. Once this requirement is fulfilled, the formation and final stability of the β-sheet motif depends on the interactions between side chains at the strands. Second, a high degree of right-handed twist contributes to β-sheet stability by favoring the burial of hydrophobic surface. Finally, the designed peptide BS2 constitutes a good scaffold to investigate the factors involved in β-sheet stability in general, and in WW domains in particular. Moreover, peptide BS2 is a suitable model to study the factors contributing to the binding of Pro-containing peptides to WW domains.

Materials and methods

Peptide synthesis

Peptides BS2 and BS3 were provided by DiverDrugs (Barcelona, Spain) and Neosystem (Strasbourg, France), respectively.

Sedimentation equilibrium

Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed to obtain the average molecular weight of peptide samples at ~0.01–0.05 mM concentrations in aqueous solution at pH 3.5 and containing 150 mM NaCl to screen nonideal effects involving charged residues at high peptide concentrations. Peptide samples (70 μL) were centrifuged at 60,000 r.p.m. in 12-mm triple-sector Epon charcoal centrepieces, using a Beckman Optima XL-A ultracentrifuge with a Ti60 rotor. Radial scans were taken at different wavelengths every 2 h until equilibrium conditions were reached. The data were analyzed using the program XLAEQ from Beckman. The partial specific volumes of the peptides were calculated on the basis of their amino acid composition and corrected for temperature (Laue et al. 1992).

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were acquired on a Jasco J-810 instrument. Peptide samples were prepared in pure H2O at pH 3.5. The concentrations of the peptide samples were determined by ultraviolet absorbance measurements and were 37 μM and 23 μM for peptides BS2 and BS3, respectively. Cells with path lengths of 0.1 and 0.5 cm were used for measurements in the far-UV and in the near-UV, respectively. CD spectra were recorded at 10°C by taking points at 0.2-nm intervals, with a scan speed of 50 nm/min−1, a response time of 2 sec, and 1 nm band width. Each spectrum was the average of eight scans, and was corrected by substraction of the solvent spectrum acquired under the same conditions. Mean residue ellipticity ([Θ], deg cm2dmole−1) values were obtained from equation 1:

|

(1) |

where Θ is the observed ellipticity, l is the cell path length expressed in centermeters, c is the molar concentration of the peptide sample, and N is the number of amino acids in the peptide sequence.

NMR spectra

Peptide samples for NMR experiments were prepared in 0.5 mL of H2O/D2O (9 : 1 ratio by volume) or in pure D2O. Peptide concentrations were ~1 mM. The pH was measured with a glass micro-electrode and was not corrected for isotope effects. The temperature of the NMR probe was calibrated using a methanol sample. Sodium [3-trimethylsilyl 2,2,3,3-2H] propionate (TSP) was used as an internal reference. The 1H-NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AMX-600 pulse spectrometer operating at a proton frequency of 600.13 MHz. One-dimensional spectra were acquired using 32 K data points, which were zero filled to 64 K data points before performing the Fourier transformation. Phase-sensitive two-dimensional correlated spectroscopy (COSY; Aue et al. 1976), total correlated spectroscopy (TOCSY; Rance 1987), nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY; Jeener et al. 1979; Kumar et al. 1980) and rotating frame nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY; Braunschweiler and Ernst 1983; Bothner-By et al. 1984) spectra were recorded by standard techniques using presaturation of the water signal and the time-proportional phase incrementation mode (Redfield and Kuntz 1975). A mixing time of 200 msec was used for NOESY and ROESY spectra. TOCSY spectra were recorded using a 80-msec MLEV17 with z filter spin-lock sequence (Rance 1987). The 1H-13C hetero-nuclear single quantum coherence spectra (HSQC; Bodenhausen and Ruben 1980) at natural 13C abundance were recorded in 1-mM peptide samples in D2O. Acquisition data matrices were defined by 2048 × 512 points in t2 and t1, respectively. Data were processed using the standard XWIN-NMR Bruker program on a Silicon Graphics computer. The two-dimensional data matrix was multiplied by a square-sine-bell window function with the corresponding shift optimized for every spectrum and zero filled to a 2 K × 1 K complex matrix prior to Fourier transformation. Baseline correction was applied in both dimensions. The 0 ppm 13C δwas obtained indirectly by multiplying the spectrometer frequency that corresponds to 0 ppm in the 1H spectrum, assigned to internal TSP reference, by 0.25144954 (Bax and Subramanian 1986; Spera and Bax 1991).

The thermal dependence of 1H chemical shifts of peptides BS2–BS3 in D2O at pH 3.5 was measured by recording a series of one-and two-dimensional TOCSY spectra at 5°C intervals over the range of from 0 to 80°C.

NMR assignment

The 1H NMR signals of peptides BS2 and BS3 in aqueous solution were readily assigned by standard sequential assignment methods (Wüthrich et al. 1984; Wüthrich 1986). Then, the 13C resonances were straightforwardly assigned on the basis of the cross-correlations observed in the HSQC spectra between the proton and the carbon to which it is bonded. The 1H and 13C δ-values of peptides BS2 and BS3 are available as Supporting Information (Supplemental Tables ST1, ST2, and ST3) and have been deposited at the PESCADOR database (http://ucmb.ulb.ac.be/Pescador/;Pajon et al. 2002).

Hydrogen exchange

The NH exchange of peptides BS2 and BS3 was followed by a tandem method. The exchange reaction was started by dissolving the lyophilized peptide in D2O at pH 3.5. Once transferred to a 5-mm NMR tube and shimmed, a series of consecutive one-and two-dimensional TOCSY experiments were run at 10°C for 6–12-h periods. The first two-dimensional spectrum was recorded 13–16 min after dissolving the peptide. Two-dimensional TOCSY spectra were acquired with 2048 complex data points in t2 and with 256 t1 increments with four scans per increment. The acquisition time for each two-dimensional TOCSY was ~24 min.

Hydrogen exchange rates were determined by fitting cross-peak volumes that were measured using the XWIN-NMR program (Bruker) to a first-order exponential decay:

|

(2) |

where I represents the volume of the cross-peak, I(0) is the cross-peak volume at t = 0, kex is the experimental rate of hydrogen exchange, and t is the time in minutes. Data were fitted with the program Microcal Origin 5.0.

Hydrogen exchange analyses can be described in terms of a structure unfolding model, in which exchange only takes place from an ‘open,’ or O, form of the amide hydrogen atom, but not from the ‘closed,’ or C, (Linderström-Lang 1955; Hvidt and Nielsen 1966; Englander and Kallenbach 1983)

|

(3) |

In this scheme, ku and kf are the local unfolding and folding rates, respectively, and krc is the intrinsic rate constant for the exchange reaction, which is dependent on the primary sequence. The intrinsic exchange rate constants for each amide proton, krc, were calculated as described. (Bai et al. 1993). The dominant mechanism of exchange for most proteins at moderate pH and temperature tends toward the limiting condition kf >> ku and kf >> krc, known as the EX2 limit. Hence, the measured exchange rate, kex reduces to equation 4:

|

(4) |

where Kop is the equilibrium constant for local transient opening of a hydrogen bonded site. This equilibrium constant relates to ΔGop, the structural free energy difference between the closed and open states:

|

(5) |

with R being the gas constant and T the absolute temperature.

The free energy of β-sheet unfolding can be obtained from the exchange rates of the slow-exchanging amide protons by assuming, as done in proteins (Wagner and Wüthrich 1979; Jeng and Dyson 1995; Woodward 1995; Englander et al. 1996), that the exchange of the most protected amide protons occur via global unfolding. In this case, ΔGop can be considered equal to ΔGu (unfolding free-energy variation). Hence,ΔGu= ∑ΔGop(i)/i, where i refers to the slow-exchanging amide protons. To account for the fact that the proline residues in the unfolded state do not have time to reach their isomeric equilibrium distribution during the exchange experiments, the obtained ΔGu value was corrected by the effect of the two Pro residues present in peptide BS2 [0.25 kcal mole−1; evaluated as described (Bai et al. 1994)].

Estimation of β-sheet populations

Independent determinations of β-sheet populations were performed for peptides BS1 and BS2 from:ΔδCαH(δCαH(observed) − δCαH(random coil), ppm), the ΔδCα (δCα(observed) − δCα(random coil), ppm), and the ΔδCβ (δCβ(observed) − δCβ(random coil), ppm) values averaged over the strand residues, excluding the amino- and carboxy-terminal residues and the residues adjacent to the β-turns (Santiveri et al. 2001). In the case of the ΔδCαH-based estimation, those residues with a ΔδCαH value deviating from the expected negative value characteristic of β-strands due to the ring current effects of aromatic rings were also excluded. In peptide BS2, they are I3, Y11, and I18 (only in aqueous solution) residues, which in the adopted β-sheet motif, are facing aromatic residues (Fig. 1 ▶), as observed in many β-hairpin peptides (de Alba et al. 1997a, 1999a; Santiveri et al. 2000, 2001). In the case of the ΔδCα -based estimation, those residues exhibiting a negative ΔδCα value instead of the expected positive one characteristic of β-strands (Spera and Bax 1991; Santiveri et al. 2001) were excluded. In peptide BS2, only the ΔδCα value of Y19 residue deviated from the expected one, which should arise from deviation from the β-sheet characteristic φ and ψ angles due to its proximity to the peptide C-end. The reference values for CαH chemical shifts of each residue in the random coil state were taken from Bundi and Wüthrich (1979) and for 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts from Wishart et al. (1995a). Because these 13C δ-values are referenced to DSS and peptides BS1–BS3 to TSP, the corresponding correction was applied (≈0.1 ppm; Wishart et al. 1995b). The reference values for 100% β-hairpin were the mean conformational shifts reported for protein β-sheets, 0.40 ppm (Wishart et al. 1991) for ΔδCαH ,−1.6 ppm (Santiveri et al. 2001) for ΔδCα, and 1.7 ppm (Santiveri et al. 2001) for ΔδCβ.

Structure calculation

Intensities of medium- and long-range NOEs were evaluated qualitatively and used to obtain upper-limit distant constraints, for example, strong (3.0 Å), intermediate between strong and medium (3.5 Å), medium (4.0 Å), intermediate between medium and weak (4.5 Å), weak (5.0 Å), and very weak (5.5 Å). Pseudo atom corrections were added where necessary. φ-angles were constrained to the range of from -180° to 0°, except for Asn and Gly. For those residues with 3JCαH-NH > 8.0 Hz φ angles were restricted to the range of from −160° to −80°. Structures were calculated on a Silicon Graphics computer using the program DYANA (Guntert et al. 1997).

Estimation of the degree of β-sheet twist

The overall degree of twist between two β-strands was estimated as the angle between the main axis of the cylinders defined by the backbone atoms at the strands using the program MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996).

Estimation of polar (ΔASApolar) and nonpolar (ΔASAnonpolar) surface areas buried upon β-hairpin formation

The solvent-accessible polar and nonpolar areas for the structure formed by the peptide BS2 were calculated using the program VADAR (Wishart et al. 1996). The polar and nonpolar surface areas buried upon β-sheet formation were computed, respectively, as the differences between the solvent-accessible polar and non-polar areas averaged over the 20 best calculated structures and those corresponding to a completely extended structure.

Electronic supplemental material

Eight tables listing the 1H and 13C δ values of peptides BS2 in aqueous solution and in 30% TFE (ST1 and ST2), and of peptide BS3 in aqueous solution (ST3), the nonsequential NOEs observed for peptide BS2 (ST4), the change in 1H δ value between 0 and 80°C for peptide BS2 (ST5), the exchange data for peptides BS2 and BS3 (ST6), the structural data for peptide BS2 (ST7), and a comparison of BS2 and WW domain structures (ST8).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. C. López and Mr. L. de la Vega for technical assistance, Dr. C. Alfonso for the sedimentation equilibrium experiments, and Dr. D.V. Laurents for English correction. This work was supported by the Spanish DGICYT project no. PB98-0677 and European project no. CEE B104-97-2086. C.M.S. was a recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the Autonomous Community of Madrid, Spain.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material: See www.proteinscience.org

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03520704.

References

- Andersen, N.H., Dyer, R.B., Fesinmeyer, R.M., Gai, F., Liu, Z., Neidigh, J.W., and Tong, H. 1999. Effect of hexafluoroisopropanol on the thermodynamics of peptide secondary structure formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 9879–9880. [Google Scholar]

- Aue, W.P., Bertholdi, E., and Ernst, R.R. 1976. Two-dimensional spectroscopy. Application to NMR. J. Chem. Phys. 64 2229–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Aurora, R. and Rose, G.D. 1998. Helix capping. Protein Sci. 7 21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., Milne, J.S., Mayne, L., and Englander, S.W. 1993. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins 17 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1994. Protein stability parameters measured by hydrogen exchange. Proteins 20 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, A. and Subramanian, J. 1986. Sensitivity-enhanced two-dimensional heteronuclear shift correlation NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 67 565–570. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, F.J., Ramírez-Alvarado, M., and Serrano, L. 1998. Formation and stability of β-hairpin structures in polypeptides. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandl, T., Cochran, A.G., and Skelton, N.J. 2003. Turn stability in β-hairpin peptides: Investigation of peptides containing 3:5 type I G1 bulge turns. Protein Sci. 12 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhausen, G. and Ruben, D.J. 1980. Natural abundance nitrogen-15 NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 69 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bothner-By, A.A., Stephens, R.L., Lee, J.M., Warren, C.D., and Jeanloz, R.W. 1984. Structure determination of a tetrasaccharide: Transient nuclear Overhauser effects in the rotating frame. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106 811–813. [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweiler, L. and Ernst, R.R. 1983. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing: Application to proton correlation spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 53 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bundi, A. and Wüthrich, K. 1979. 1H-NMR parameters of the common amino acid residues measured in aqueous solution of linear tetrapeptides H-Gly-Gly-X-Ala-OH. Biopolymers 18 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.Y., Lin, C.K., Lee, C.T., Jan, H., and Chan, S.I. 2001. Effects of turn residues in directing the formation of the β-sheet and in the stability of the β-sheet. Protein Sci. 10 1794–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, A.G., Tong, R.T., Starovasnik, M.A., Park, E.J., McDowell, R.S., Theaker, J.E., and Skelton, N.J. 2001. A minimal peptide scaffold for β-turn display: Optimizing a strand position in disulfidecyclized β-hairpins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, C., Raghotama, S.R., and Balaram, P. 1998. A designed three-stranded β-sheet peptide as a multiple β-hairpin model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 5812–5813. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999. A designed four-stranded β-sheet structure in a designed, synthetic polypeptide. Chem. Commun. 11 967–968. [Google Scholar]

- Das, C., Nayak, V., Raghothama, S., and Balaram, P. 2000. Synthetic protein design: Construction of a four-stranded β-sheet structure and evaluation of its integrity in methanol-water systems. J. Pept. Res. 56 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, E., Blanco, F.J., Jiménez, M.A., Rico, M., and Nieto, J.L. 1995. Interactions responsible for the pH dependence of the β-hairpin conformational population formed by a designed linear peptide. Eur. J. Biochem. 233 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, E., Jiménez, M.A., Rico, M., and Nieto, J.L. 1996. Conformational investigation of designed short linear peptides able to fold into β-hairpin structures in aqueous solution. Fold. Des. 1 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, E., Jiménez, M.A., and Rico, M. 1997a. Turn residue sequence determines β-hairpin conformation in designed peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, E., Rico, M., and Jiménez, M.A. 1997b. Cross-strand side-chain interactions versus turn conformation in β-hairpins. Protein Sci. 6 2548–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999a. The turn sequence directs β-strand alignment in designed β-hairpins. Protein Sci. 8 2234–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba, E., Santoro, J., Rico, M., and Jiménez, M.A. 1999b. De novo design of a monomeric three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet. Protein Sci. 8 854–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander, S.W. and Kallenbach, N.R. 1983. Hydrogen exchange and structural dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids. Q. Rev. Biophys. 16 521–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander, S.W., Sosnick, T.R., Englander, J.J., and Mayne, L. 1996. Mechanisms and uses of hydrogen exchange. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, J.F., Muñoz, V., and Gellman, S.H. 2001. Interplay between hydrophobic cluster and loop propensity in β-hairpin formation. J. Mol. Biol. 306 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellman, S.H. 1998. Minimal model systems for β-sheet secondary structure in proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2 717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, P.M. and Chakrabartty, A. 2001. Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides: Structures of amyloid fibrils and alternate aggregation products. Biopolymers 60 381–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones, S.R. and Searle, M.S. 2000. Structure, folding, and energetics of cooperative interactions between β-strands of a de novo designed three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 8350–8356. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones, S.R., Maynard, A.J., and Searle, M.S. 1999. Dissecting the stability of a β-hairpin peptide that folds in water: NMR and molecular dynamics analysis of the β-turn and β-strand contributions to folding. J. Mol. Biol. 292 1051–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert, P., Mumenthaler, C., and Wüthrich, K. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque, T.S. and Gellman, S.H. 1997. Insights into β-hairpin stability in aqueous solution from peptides with enforced type I′ and type II′ β-turns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 2303–2304. [Google Scholar]

- Hvidt, A. and Nielsen, S.O. 1966. Hydrogen exchange in proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 21 287–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeener, J., Meier, B.H., Bachmann, P., and Ernst, R.R. 1979. Investigation of exchange processes by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 71 4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, M.F. and Dyson, H.J. 1995. Comparison of the hydrogen-exchange behavior of reduced and oxidized Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry 34 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Jr., W.C. 1988. Secondary structure of proteins through circular dichroism spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 17 145–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karle, I.L., Awasthi, S.K., and Balaram, P. 1996. A designed β-hairpin peptide in crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 8189–8193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul, R. and Balaram, P. 1999. Stereochemical control of peptide folding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.W. 2000. Mechanisms of amyloidogenesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 824–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wuthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme, T., Ramírez-Alvarado, M., and Serrano, L. 1998. Design of a 20-amino acid, three-stranded β-sheet protein. Science. 281 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Ernst, R.R., and Wüthrich, K. 1980. A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement (2D NOE) experiment for the elucidation of complete proton-proton cross-relaxation networks in biological macromolecules. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 95 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, E., Kortemme, T., López de la Paz, M., and Serrano, L. 1999. The design of linear peptides that fold as monomeric β-sheet structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue, T.M., Shak, B.D., Ridgeway, T.M., and Pelletier, S.L. 1992. Computer aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In Analytical ultracentrifugation in biochemistry and polymer science, (eds. S.E. Harding, A.J. Rowe, and J.C. Horton), pp. 90–125. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK.

- Linderström-Lang, K. 1955. Chem. Soc. (London), Spec. Publ. 2 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- López de la Paz, M., Lacroix, E., Ramírez-Alvarado, M., and Serrano, L. 2001. Computer-aided design of β-sheet peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 312 229–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macías, M.J., Gervais, V., Civera, C., and Oschkinat, H. 2000. Structural analysis of WW domains and design of a WW prototype. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, A.J., Sharman, G.J., and Searle, M.S. 1998. Origin of β-hairpin stability in solution: Structural and themodynamic analysis of the folding of a model peptide supports hydrophobic stabilization in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 1996–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, V., Thompson, P.A., Hofrichter, J., and Eaton, W.A. 1997. Folding dynamics and mechanism of β-hairpin formation. Nature. 390 196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, V., Henry, E.R., Hofrichter, J., and Eaton, W.A. 1998. A statistical mechanical model for β-hairpin kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 95 5872–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajon, A., Vranken, W.F., Jiménez, M.A., Rico, M., and Wodak, S.J. 2002. Pescador: The PEptides in solution conformAtion database: Online resource. J. Biomol. NMR. 23 85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, R., Chaturvedi, S., and Go, K. 1995. Design of α-helical peptides: Their role in protein folding and molecular biology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 64 1–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Alvarado, M., Blanco, F.J., Niemann, H., and Serrano, L. 1997. Role of β-turn residues in β-hairpin formation and stability in designed peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 273 898–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Alvarado, M., Kortemme, T., Blanco, F.J., and Serrano, L. 1999. β-hairpin and β-sheet formation in designed linear peptides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Alvarado, M., Blanco, F.J., and Serrano, L. 2001. Elongation of the BH8 β-hairpin peptide: Electrostatic interactions in β-hairpin formation and stability. Protein Sci. 10 1381–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rance, M. 1987. Improved techniques for homonuclear rotating-frame and isotropic mixing experiments. J. Magn. Reson. 74 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, A.G. and Kuntz, S.D. 1975. Quadrature Fourier detection: Simple multiplex for dual detection. J. Magn. Reson. 19 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.S. 1981. The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure. Adv. Protein Chem. 34 167–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohl, C.A. and Baldwin, R.L. 1998. Deciphering rules of helix stability in peptides. Methods Enzymol. 295 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J. and Cochran, A.G. 2000. Designing stable b-hairpins: Energetic contributions from cross-strand residues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 12600–12601. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J., Blandl, T., Skelton, N.J., and Cochran, A.G. 2003. Stability of cyclic β-hairpins: Asymmetric contributions from side chains of a hydrogen-bonded cross-strand residue pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiveri, C.M., Rico, M., and Jiménez, M.A. 2000. Position effect of cross-strand side-chain interactions on β-hairpin formation. Protein Sci. 9 2151–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001. 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts as a tool to delineate β-hairpin structures in peptides. J. Biomol. NMR. 19 331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiveri, C.M., Santoro, J., Rico, M., and Jiménez, M.A. 2002. Thermodynamic analysis of β-hairpin-forming peptides from the thermal dependence of 1H NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124 14903–14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiveri, C.M., Rico, M., Jiménez, M.A., Pastor, M.T., and Pérez-Payá, E. 2003. Insights into the determinants of β-sheet stability: 1H and 13C NMR conformational investigation of three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet-forming peptides. J. Pept. Res. 61 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, H.L. and Gellman, S.H. 1998. Use of a designed triple-stranded an-tiparallel β-sheet to probe β-sheet cooperativity in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 4869–4870. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, M.S., Griffiths-Jones, S.R., and Skinner-Smith, H. 1999. Energetics of weak interactions in a β-hairpin peptide: Electrostatic and hydrophobic contributions to stability from lysine salt bridges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 11615–11620. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, L. 2000. The relationship between sequence and structure in elementary folding units. Adv. Protein Chem. 53 49–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.K. and Regan, L. 1997. Construction and design of β-sheets. Acc. Chem. Res. 30 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Spera, S. and Bax, A. 1991. Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cβ 13C NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- Sreerama, N. and Woody, R.W. 2000. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: Comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 287 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger, H.E., Syud, F.A., Espinosa, J.F., Giriat, I., Muir, T., and Gellman, S.H. 2001. Length-dependent stability and strand length limits in antiparallel β-sheet secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98 12015–12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, E.H. 1974. Aromatic contributions to circular dichroism spectra of proteins. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 2 113–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syud, F.A., Espinosa, J.F., and Gellman, S.H. 1999. NMR-based quantification of β-sheet populations in aqueous solution through use of reference peptides for the folded and unfolded states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 11578–11579. [Google Scholar]

- Syud, F.A., Stanger, H.E., and Gellman, S.H. 2001. Interstrand side chain–side chain interactions in a designed β-hairpin: Significance of both lateral and diagonal pairings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 8667–8677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syud, F.A., Stanger, H.E., Mortell, H.S., Espinosa, J.F., Fisk, J.D., Fry, C.G., and Gellman, S.H. 2003. Influence of strand number on antiparallel β-sheet stability in designed three- and four-stranded β-sheets. J. Mol. Biol. 326 553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G. and Wüthrich, K. 1979. Correlation between the amide proton exchange rates and the denaturation temperatures in globular proteins related to the basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 130 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintjens, R., Wieruszeski, J.M., Drobecq, H., Rousselot-Pailley, P., Buee, L., Lippens, G., and Landrieu, I. 2001. 1H NMR study on the binding of Pin1 Trp-Trp domain with phosphothreonine peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 276 25150–25156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Sykes, B.D., and Richards, F.M. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222 311–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Holm, A., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes. B.D., 1995a. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR. 5 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Yao, J., Abildgaard, F., Dyson, H.J., Oldfield, E., Markley, J.L., and Sykes, B.D. 1995b. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 6 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Willard, L., and Sykes, B.D. 1996. VADAR. Volume angles define_s area, version 1.3. University of Alberta. Protein Engineering Network of Centres of Excellence. Edmonton, Canada.

- Woodward, C.K. 1994. Hydrogen exchange and protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. 1995. Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol. 246 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. and Dunker, A.K. 1996. Aromatic and cystine side chain circular dichroism in proteins. In Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules (ed. G. Fasman), pp. 109–158. Plenum Press, New York.

- Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Wüthrich, K., Billeter, M., and Braun, W. 1984. Polypeptide secondary structure determination by nuclear magnetic resonance observation of short proton-proton distances. J. Mol. Biol. 180 715–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]