Abstract

We present a method for prediction of functional sites in a set of aligned protein sequences. The method selects sites which are both well conserved and clustered together in space, as inferred from the 3D structures of proteins included in the alignment. We tested the method using 86 alignments from the NCBI CDD database, where the sites of experimentally determined ligand and/or macromolecular interactions are annotated. In agreement with earlier investigations, we found that functional site predictions are most successful when overall background sequence conservation is low, such that sites under evolutionary constraint become apparent. In addition, we found that averaging of conservation values across spatially clustered sites improves predictions under certain conditions: that is, when overall conservation is relatively high and when the site in question involves a large macromolecular binding interface. Under these conditions it is better to look for clusters of conserved sites than to look for particular conserved sites.

Keywords: protein domains, prediction of functional residues, evolutionary conservation

Despite recent growth of the protein sequence and structure databases, there remains only a small fraction of proteins whose functions have been experimentally characterized. It is sometimes possible to infer the function of uncharacterized proteins by comparison to the sequences or structures of functionally annotated homologs. Common descent does not necessarily imply functional similarity, however (Hegyi and Gerstein 1999; Devos and Valencia 2000; Todd et al. 2001) and functional annotation transferred from one homologous protein to another can result in incorrect functional assignment. To verify functional assignments one must examine the common features conserved among homologs and attempt to identify functionally important sites.

Several investigators have considered the problem of functional site prediction using multiple sequence alignments (Casari et al. 1995; Andrade et al. 1997; Hannenhalli and Russell 2000; Li et al. 2003). Casari et al. (1995), for example, applied principal component analysis to a vector representation of protein sequences in a multidimensional “sequence space,” to derive subfamily-specific residues involved in protein function. Andrade et al. (1997) proposed a rigorous clustering algorithm based on a self-organizing map as a means to identify protein subfamilies and retrieve characteristic sequence patterns. As functional similarity can be inferred from clades in phylogenetic trees, some methods of functional site prediction use phylogenetic analysis to identify residues associated with functional divergence (Lichtarge et al. 1996; Sjolander 1998; Aloy et al. 2001; Madabushi et al. 2002; del Sol Mesa et al. 2003). The evolutionary trace (ET) method, for example, delineates invariant residues responsible for subgroup specificity by partitioning the dendrogram into an increasing number of subgroups of similar sequences with subsequent analysis of their three-dimensional (3D) structures (Lichtarge et al. 1996; Aloy et al. 2001; Madabushi et al. 2002).

Despite the efforts in this field, the accuracy of functional site predictions remains low, suggesting that it may be worthwhile to consider other aspects beyond sequence conservation. Use of structure information is one possibility, because knowledge of the protein structure is necessary for predicting many aspects of protein function (Teichmann et al. 2001). Given that functionally important surface regions often contain residues with specific characteristics, some methods attempt to identify functional sites on the basis of physicochemical properties of individual residues, their electrostatic contribution, and their location in the 3D structure (Jones and Thornton 1997; Tsai et al. 1997; Elcock 2001; Bartlett et al. 2002). Landgraf and colleagues (2001), for example, offered an automated method for functional site prediction by identifying 3D clusters of conserved residues using residue-specific (regional) and global similarity scores.

Here we present a method which is based on the assumption that the structural location of functional sites is conserved between homologous proteins and that functionally important residues tend to cluster together in space, forming three-dimensional residue clusters or surface patches. In the method considered here, each residue is assigned a score which depends on its own conservation in homologs and the conservation of residues in its spatial neighborhood, as judged from the analysis of known structures within a given protein family. We hypothesize that high-scoring sites are more likely to be involved in specific binding or catalysis, and that one may identify functionally important residues even in the absence of structural data on protein–ligand or macromolecular complexes.

We tested the method on a benchmark of 86 protein domain families, including families with a wide variety of functions and sequence diversity. To assess the accuracy of functional site predictions, we applied a rigorous receiver operating characteristic (ROC) test (see Materials and Methods). This gave us a means to compare different scoring schemes directly, by calculating the actual number of correctly predicted functional sites at a given level of false assignments. We show that including information about conserved structural features in some cases helps to make more accurate predictions, especially for DNA/RNA binding macromolecular interfaces. When sequence diversity is low, spatial averaging also helps to detect functional sites against the high background of sequence conservation.

Results

Functional site predictions based on sequence conservation and sequence conservation with spatial averaging

Functionally relevant residues in proteins are often conserved among all or a majority of members of a protein family. Accordingly, these residues can be identified from the analysis of positional conservation in multiple sequence alignments using different sequence conservation measures. Here, we employed information content and maximum likelihood estimates of the expected number of substitutions per position (substitution rate), as calculated by the PAML package (Yang 1997). We found that substitution rates performed better in terms of detecting functional sites than information content; the recognition rate at 5% false positives (R0.05) for the whole test set was 0.32 and 0.25 using PAML substitution rate and information content, respectively. This difference is especially pronounced for highly divergent domain families and could be due to the fact that the substitution rate calculated by PAML takes into account the phylogenetic history of the protein family.

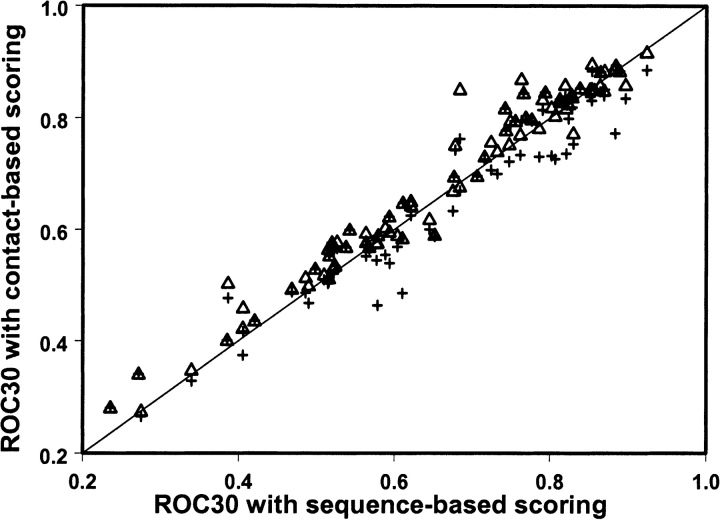

To determine whether clustering of conserved residues in space and consideration of their solvent accessibility help to identify functional sites, we compared scoring functions based on sequence conservation alone and sequence conservation with spatial averaging (see Materials and Methods). Figure 1 ▶ shows the ROC30 statistic for the contact-based scoring function with an optimized distance cutoff (the distance cutoff yielding the best performance for each domain family) and with a fixed distance cutoff (less than 6 Å), plotted against ROC30 values obtained with a sequence-based scoring function. As can be seen from the figure, the contact-based scoring function with optimized distance cutoff detects more functional sites for 73% of domain families compared to sequence-based scoring function. Because the value of optimal distance cutoff is difficult to determine a priori for each domain family, in our work we used the 6 Å distance cutoff, which has been shown to yield the best performance.

Figure 1.

The ROC30 statistic for each domain family obtained with the contact-based scoring function (equation 1) and optimized distance interval cutoff is plotted vs. ROC30 values calculated with the original sequence-based scoring function (triangles). The ROC30 statistic for each domain family obtained with the contact-based scoring function (equation 1) and the distance cutoff less than 6 Å is also shown.

Functional site predictions for different functional categories

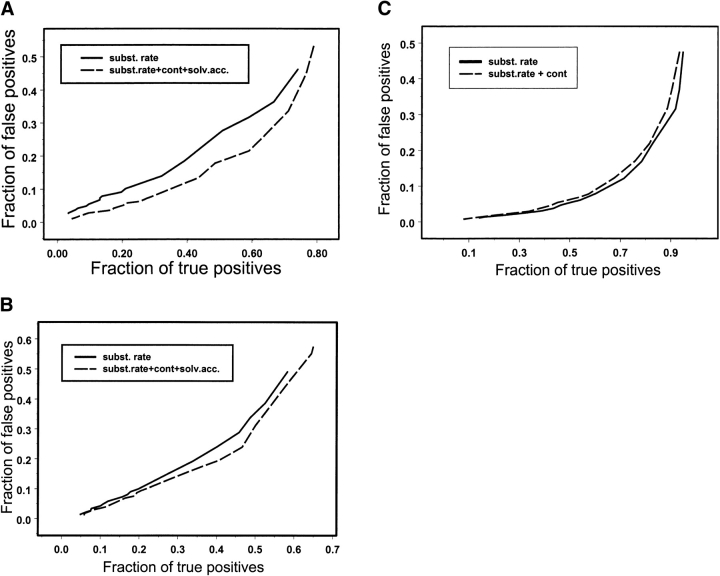

Analyzing different functional categories we found that conserved contacts and solvent accessibility are particularly useful for predicting DNA/RNA-binding and protein–protein binding interfaces. The difference in recognition accuracies can be represented by ROC plots (Fig. 2A,B ▶), which show the fraction of false positives for any given recognition rate. For example, at 5% of false positives the structure-based scoring function detects about 20% of DNA/RNA-binding and 14% of protein–protein binding sites, whereas sequence-based scoring function yields a recognition rate of 9%–10%. An improvement in the ROC30 statistic upon including structural information is also observed for DNA/RNA binding and protein–protein binding sites, as can be seen from Table 1. It was shown earlier that the level of conservation of DNA-binding and protein–protein binding sites and, as a consequence detection accuracy, depends on the conservation of the entire protein sequence (Luscombe and Thornton 2002; Nooren and Thornton 2003). Given that the average sequence identity in our test families is about 30%, DNA/RNA-binding and protein–protein binding sites are also predicted with limited accuracy.

Figure 2.

The fraction of correctly identified DNA/RNA binding sites (A), protein–protein binding sites (B), and catalytic sites (C) is plotted against the fraction of incorrectly identified functional sites for different scoring functions: the original sequence-based scoring function (solid line) and contact-solvent-accessibility-based scoring function (equation 2; dashed line). The contact-based scoring function (equation 1) is used in case of catalytic site prediction. The contacts are defined between residues separated by a distance of 6 Å.

Table 1.

Average ROC30values calculated with different scoring functions for different functional categories of test domains: catalytic, DNA/RNA-binding and protein-protein binding domains

| Catalytic sites | DNA/RNA binding sites | Protein-protein interfaces | All | |

| Subst. rates | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.37 |

| Subst. rates+contacts | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.38 |

| Subst. rates +contacts+solv.acc. | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.37 |

We found that the success rate in detection of catalytic sites is higher than for other types of functional sites, about 47% true positives recognized at the 5% false positive rate (Fig. 2C ▶). The increased prediction accuracy for catalytic sites can be explained by the fact that catalytic sites apparently are under stronger selection pressure (not counting those cases where different functional groups could mediate the same catalytic mechanisms in homologous enzymes [Todd et al. 2002]), such that even families with a high degree of sequence diversity exhibit strong conservation of catalytic sites. As can be seen from Figure 2C ▶, structure information does not seem to assist the prediction of catalytic sites. Examination of Table 1 shows that residue solvent exposure is also not a very important factor in predicting catalytic sites, which agrees with the previous observation that despite their polarity, catalytic residues have lower solvent exposure compared to other residues (Bartlett et al. 2002).

It should be noted that there is great variety among different catalytic domains. They can vary in terms of the type of enzymatic activity, the sizes of protein clefts, and interacting ligands. These factors apparently make it difficult to predict active sites using structure-based scoring function with the fixed distance cutoff. As a consequence, the sequence-based scoring function alone gives more reliable predictions for sufficiently diverse domain families where conserved active sites become more apparent. On the other hand, DNA/RNA binding and protein–protein binding sites very often are nonspecific and form contiguous patches on the surface of the protein. These factors apparently allow the contact-solvent-accessibility scoring function to improve detection of functional sites.

Statistical significance of functional site predictions

To compare the results obtained by our method to the outcome of random assignments, we performed a binomial test for each domain family. The number of trials in the binomial test was equal to the overall number of functional residues in a given domain alignment, and the probability of success was calculated as a number of functional residues in the alignment divided by the overall number of residues in the alignment. Using the contact-solvent-accessibility scoring function, we found that predictions of functional sites for 57% of domain families are significant with P-values <0.05 (P-value here denotes the probability of finding an equal or higher number of correctly predicted functional sites purely from the binomial distribution). Values for domains with annotated catalytic, DNA/RNA-binding, and protein–protein binding sites were 76%, 35%, and 20%, respectively. Sequence conservation scoring yielded significant predictions of catalytic sites for 65% of domains, DNA/ RNA-binding sites for 24% of domains, and protein–protein interfaces for 20% of domains (50% overall). In all cases the site was predicted to be functional if it belonged to the top 5% of the most conserved sites in domain alignment.

These results are comparable to those of the 3D cluster analysis employed by Landgraf et al. (2001). Those investigators identified 36% of all interface residues at a threshold of less than 1% expected from reshuffled alignments and 67% at the less stringent threshold of 10%. An automated method based on the ET approach found the correct locations of catalytic residue clusters for 62 out of 80 enzymes (78% of clusters compared to 76% of catalytic domains with significant predictions found by our method) for multiple alignments with less than 30% identity (Aloy et al. 2001). Aloy et al. defined the predicted site/cluster to be correct if the overlap between the volume of predicted cluster and the volume of annotated functional site was more than 50%. Their method was considered to find a right prediction for a given protein if at least one of the predicted functional clusters was correct.

Conserved structural features help to predict functional residues for domain alignments with low sequence diversity

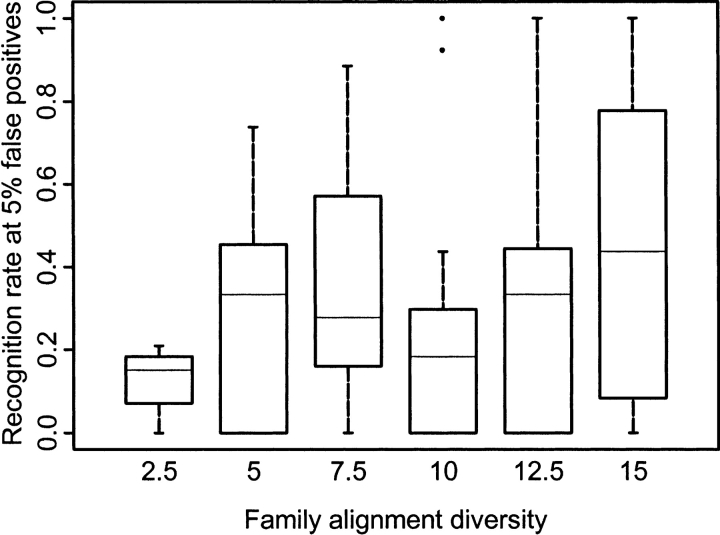

Our test set can be considered rather heterogeneous in terms of the sequence diversity of domain families (Table 2). For domain families with low sequence diversity, sequence and structure similarity is extensive and the degree of residue conservation is high for all positions in alignments. Sequence profiles based on low-diversity alignments perform relatively poorly in a database search (Panchenko and Bryant 2002), and we similarly found that functional residue identification is problematic in these cases. As shown in Figure 3 ▶, for low-diversity domain alignments (where the number of different amino acid types per column, Nobs is less than 5 and average sequence identity is about 45%), the average recognition rate (R0.05) is less than 0.2, whereas for more diverse alignments (Nobs is greater than 15 and average sequence identity is about 20%), the average recognition rate is twice as high. In agreement with these results, Aloy et al. (2001) reported that for multiple alignments with sequence identity of more than 30%, their method of functional site prediction has very limited applications.

Table 2.

Names of 86 CDD families used together with the pdb codes of their first structures, average sequence identities of family alignments (average number of different amino acid types per column, Nobs), alignment lengths, and the overall numbers of functional sites

| Name | Pdb code | %identity/Nobs | Length | Domain description | Number of functional sites |

| 35EXOc | 2kzm | 21/12 | 101 | 3′–5′ exonuclease | 5 (5C) |

| 53EXOc | 1xo1 | 35/8 | 213 | 5′–3′ exonuclease | 8 (8C) |

| ACTIN | 1dga | 34/9 | 305 | Actin | 24 (18P) |

| ADF | 1cof | 24/10 | 115 | Actin depolymerisation factor/cofilin-like domains | 10 (10P) |

| alkPPc | 1elz | 40/6 | 325 | Alkaline phosphatase homologs | 13 (13C) |

| Aminopeptidase | 1b65 | 30/6 | 59 | L-Aminopeptidase domain | 2 (2C) |

| AP2 | 1gcc | 47/5 | 59 | DNA-binding domain found in transcription regulators in plants | 11 (11D) |

| AP2Ec | 1qtw | 28/8 | 211 | AP endonuclease family 2 | 13 (9C) |

| Arfaptin | 1i4d | 25/6 | 193 | Arfaptin domain | 11 (11P) |

| BPI | 1bpl | 16/11 | 131 | BPI/LBP/CETP domain | 13 |

| C1 | 1faq | 28/11 | 43 | Protein kinase C conserved region 1 | 8 (8C) |

| C2 | 1dqv | 26/14 | 63 | Protein kinase C conserved region 2 | 4 (4C) |

| CASc | 1cp3 | 37/8 | 203 | Caspase, interleukin-1 β converting enzyme homologs | 16 (16C) |

| CBM9 | 1i82 | 39/6 | 145 | Family 9 carbohydrate-binding module | 18 |

| CH | 1aoa | 22/13 | 75 | Calponin homology domain | 36 (36P) |

| ChtBD3 | 1aiw | 30/9 | 38 | Chitin/cellulose binding domain | 2 |

| cNMP (CAP_ED) | 1rgs | 19/14 | 91 | Cyclic nucleotide-monophosphate binding domain | 4 |

| CPT | 1qhx | 38/3 | 170 | Chloramphenicol phosphotransferase | 21 (15C) |

| DED | 1a1z | 22/7 | 61 | Death effector domain | 9 (9P) |

| DEXDc | 1d9x | 25/15 | 96 | DEAD-like helicases superfamily | 9 |

| DSPc | 1vhr | 28/8 | 118 | Dual specificity phosphatases | 6 (6C) |

| DSRM | 1di2 | 26/13 | 56 | Double-stranded RNA binding motif | 12 (12D) |

| ENDO3c | 1muy | 22/9 | 125 | Endonuclease III | 19 (8C) |

| eu-GS | 2hgs | 38/5 | 442 | Eukaryotic glutathione synthetase | 29 (7C) |

| fer2 | 1b9r | 26/15 | 60 | 2Fe-2S iron-sulfur cluster binding domain | 10 |

| FGF | 1qqk | 32/8 | 113 | Acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor family | 22 (22P) |

| FH | 1e17 | 57/7 | 52 | Forkhead, winged helix | 5 (5D) |

| FlpREC | 1flo | 34/4 | 338 | Flp recombinase domain | 7 (7C) |

| FYVE | 1vfy | 35/9 | 55 | FYVE, zinc-binding domain | 13 |

| G-α | 1azt | 39/10 | 304 | G protein α-subunit | 61 (52P) |

| GlcAT-I | 1fgg | 44/6 | 213 | β, 3-glucuronyltransferase I domain | 12 (12C) |

| Glm_e | 1ccw | 51/4 | 368 | Coenzyme B12-dependent enzyme glutamate mutase | 14 (14C) |

| GuKc | 1gky | 27/10 | 130 | Guanylate kinase homologs | 15 (10C,4P) |

| GYF | 1gyf | 26/7 | 56 | GYF-domain | 16 (16P) |

| H15 | 1hst | 33/11 | 77 | linker histone 1 and histone 5 domains | 15 (15D) |

| H2A | 1aoi | 65/4 | 114 | Histone 2A | 7 (7D) |

| HDc | 1f0j | 18/16 | 91 | Metal-dependent phosphohydrolases with conserved ‘HD’ motif | 4 (4C) |

| HECTc | 1c4z | 29/8 | 312 | HECT domain | 29 (14C,15P) |

| HELICc | 1d2m | 17/16 | 130 | Helicase superfamily C-terminal domain | 16 (13D) |

| HPT | 1qsp | 21/10 | 86 | Histidine Phosphotransfer domain | 5 |

| HTH_ARSR | 1smt | 23/13 | 71 | Arsenical Resistance Operon Repressor | 26 (24D) |

| HTH_XRE | 1lmb | 22/15 | 51 | Helix-turn-helix XRE-family like proteins | 7 (7D) |

| KISc | 3kar | 43/10 | 245 | Kinesin motor, catalytic domain, ATPase | 8 |

| LIGANc | 1dgs | 44/7 | 284 | NAD+ dependent DNA ligase adenylation domain | 10 (1C) |

| LMWPc | 1dlp | 34/15 | 112 | Low-molecular-weight phosphatase family | 6 (6C) |

| MADS | 1mnm | 43/4 | 85 | MCM1, Agamous, Deficiens, and serum response factor domain | 6 (6D) |

| MBD | 1qk9 | 31/6 | 61 | Methyl-CpG binding domain | 8 (8D) |

| Mog1 | 1eq6 | 37/4 | 165 | Homolog to Ran-Binding Protein Mog1p | 22 (22P) |

| MYSc | 2mys | 41/11 | 576 | Myosin, large ATPases | 16 |

| PAX | 1pdn | 68/3 | 128 | Paired Box domain | 34 (34D) |

| PDZ | 3pdz | 24/15 | 62 | PDZ domain | 12 (12P) |

| PI3Kc | 1e8x | 26/10 | 272 | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase, catalytic domain | 35 (27C) |

| PIPKc | 1bo1 | 36/6 | 264 | Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases | 45 (37C) |

| PLCc | 1gym | 28/8 | 189 | Phospholipase C, catalytic domain | 11 (11C) |

| PNPsynthase | 1ho4 | 44/6 | 230 | Pyridoxine 5′-Phosphate synthase domain | 18 (18C) |

| POLXc | 2bpf | 40/6 | 294 | DNA polymerase X family | 13 (3C,10D) |

| PP2Ac | 1aui | 37/7 | 235 | Protein phosphatase 2A homologs, catalytic domain | 16 (13C) |

| PP2Cc | 1a6q | 26/13 | 178 | Serine/threonine phosphatases, family 2C, catalytic domain | 9 (9C) |

| PRCH | 1prc | 50/6 | 224 | Photosynthetic reaction center complex, subunit H | 6 |

| PROF | 1dlj | 32/8 | 108 | Profilin | 17 (11P) |

| PTB | 2nmb | 17/11 | 113 | Phosphotyrosine-binding domain, phosphotyrosine-interaction domain | 10 |

| PTPc | 2shp | 37/13 | 195 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | 6 (6C) |

| PTS_IIA_fru | 1a6j | 31/7 | 118 | PTS system, fructose/mannitol specific IIA subunit | 2 (2C) |

| PTS_IIA_lac | 1e2a | 38/5 | 99 | PTS system, lactose/cellobiose specific IIA subunit | 7 (7C) |

| PTS_IIA_man | 1pdo | 27/9 | 100 | PTS system, mannose/sorbose specific IIA subunit | 7 (7C) |

| PTS_IIB_glc | 1iba | 32/7 | 81 | PTS system, glucose/sucrose specific IIB subunit | 7 (7C) |

| PTS_IIB_lac | 1h9c | 36/4 | 98 | PTS system, lactose/cellobiose specific IIB subunit | 7 (7C) |

| RA | 1rax | 20/11 | 66 | RasGTP binding domain from guanine nucleotide exchange factors | 13 (13P) |

| RhoGAP | 1am4 | 26/13 | 138 | GTPase-activator protein for Rho-like GTPases | 5 (5P) |

| RPA | 1ewi | 19/9 | 48 | Human Replication Protein A | 7 (7D) |

| S4 | 1dm9 | 23/13 | 51 | S4/Hsp/tRNA synthetase RNA-binding domain | 5 (5D) |

| SAM | 1b0x | 21/13 | 57 | Sterile alpha motif | 5 (4P) |

| SEC14 | 1aua | 18/13 | 129 | Sec14p-like lipid-binding domain | 16 |

| Sec7 | 1pbv | 26/10 | 178 | Sec7 domain | 22 (22C) |

| SERPIN | 1ova | 34/12 | 280 | Serine proteinase inhibitor | 14 (14P) |

| SH2 | 2shp | 29/16 | 70 | Src homology 2 domains | 8 |

| SNc | 2sns | 30/9 | 91 | Staphylococcal nuclease homolog | 7 (7C) |

| TBOX | 1xbr | 43/7 | 169 | T-box DNA binding domain | 25 (25D) |

| TNF | 1a8m | 23/9 | 103 | Tumor necrosis factor | 7 (7P) |

| Topo6_Spo | 1d3y | 32/8 | 250 | DNA topoisomerase VI subunit A | 4 (4C) |

| ToxGAP | 1he1 | 41/4 | 116 | GTPase-activating protein domain | 15 |

| UBCc | 2ucz | 29/13 | 129 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme B2 and UBC homologs | 6 P (5P,1C) |

| VWA | 1dzi | 19/16 | 119 | von Willebrand factor type A domain | 5 (5P) |

| XPG | 1a76 | 32/8 | 254 | Xeroderma pigmentosum G N- and I-regions | 38 (8C,32D) |

| ZnF_GATA | 2gat | 45/6 | 51 | Zinc finger DNA binding domain | 19 (17D) |

| ZnMc | 1smp | 31/12 | 91 | Zinc-dependent metalloprotease | 7 (7C) |

Number of active sites, DNA/RNA binding and protein-protein binding sites are denoted by letters C, D, and P, respectively, and shown in parentheses.

Figure 3.

The site recognition rate (R0.05) obtained with the sequence based scoring function is plotted for different sequence diversity ranges. Domain family diversity is calculated as the average number of different amino acid types per column in the CDD alignment. Results are shown as a boxplot (Chambers 1998), where the central line in each box shows the median recognition rate within a given bin of diversity, the upper and lower boundaries of the box show the upper and lower quartiles, and the vertical lines extend to a value 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outlier values beyond these ranges are shown as individual points.

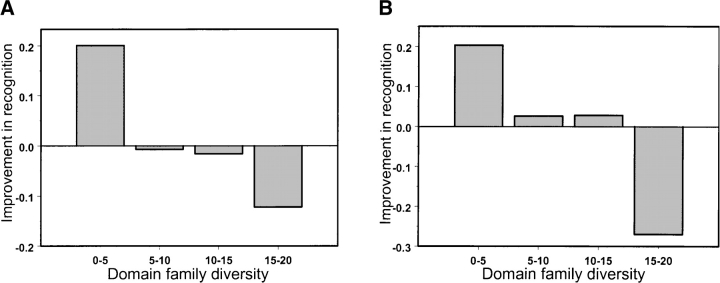

We found that spatial averaging nonetheless improves functional site recognition for low-diversity alignments. As can be seen from Figure 4A ▶, the site recognition rate increases for low-diversity families upon including the structure-based term in the scoring function. The improvement in accuracy exceeds 20% for this range of diversity, mostly affecting domain families with catalytic and DNA/RNA-binding sites. Moreover, including the solvent accessibility term in the scoring function improves the prediction accuracy for families with medium sequence diversity (Nobs between 5 and 15), as shown in Figure 4B ▶. Diverse domain families with highly conserved functional sites, on average, show a decline in recognition rate when structure-based scoring function is used. For example, the recognition rate for a very diverse family of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases (HDc; average percent identity 18%) drops from 100% recognition with the original sequence-based scoring to 50% with contact-based scoring. This family has a particularly conserved HD-motif, which suggests that the conservation signal is high enough to be detected by sequence-based scoring alone. Structure-based scoring in this case can flatten the overall signal by averaging the conservation measure over neighboring residues.

Figure 4.

Improvement in the site recognition rate upon including the structural term in the scoring function is plotted vs. the sequence diversity of domain families. The difference in recognition rate is calculated as the average recognition rate (R0.05) obtained with the contact-based scoring function (A) or contact-solvent-accessibility scoring function (B) minus the average recognition rate for the sequence-based scoring function.

Discussion

In an attempt to identify functionally important sites, we present a method which quantifies the conservation of protein sites in terms of preserving amino acid types and local structural environments. First, the scoring function, which accounted for the local environment and/or surface exposure of protein sites, was found to perform better than sequence-based scoring alone in many cases, serving mainly as a filter to eliminate nonfunctional residue conserved positions. The largest improvement was observed for predicting DNA/RNA binding sites. This observation is in agreement with the previous studies which similarly demonstrated that accounting for 3D clusters of conserved residues reduced the number of false positives identified (Landgraf et al. 2001).

Second, it was shown that the sequence divergence of domain alignments is a prerequisite for the successful functional prediction, and structurally conserved features help to discriminate functional and nonfunctional sites for families with low sequence diversity. Accordingly, to increase blind prediction accuracy we can formulate several rules based on these observations. The first: To predict functional residues for low-diversity families, whenever possible diversify them with more distantly related family representatives and, if not possible, use a structure-based scoring function. The second rule can be applied if the general function of the domain family is known: Whenever possible use contact-based and solvent accessibility-based scoring for predicting DNA/RNA binding and protein–protein binding sites; for catalytic sites use a contact-based scoring function for low-diversity families and the original sequence-based scoring function for all others. If a blind prediction of functional residues is being attempted, the simple strategy would be to apply these rules for initial family screening and then define functional residues as those having conservation scores among the top 7%, 6%, and 5% of conservation scores for catalytic, DNA/RNA binding, and protein–protein binding sites, respectively. These conservation score cutoffs correspond approximately to the error rate of 5% false positives.

As we showed, spatial averaging does not always help the function prediction, and prediction accuracy still remains quite low. Madabushi et al. (2002) demonstrated that the number of clusters (or size of the largest cluster) of functional residues determined by the ET method was larger than the number of clusters predicted by random simulations for 98% of their test cases (at the significance level of 5%). It should be noted that this result does not imply that the ET method is able to correctly identify active sites for 98% of test proteins at the 5% significance level. Similarly to Landgraf et al. (2001), we showed that the accuracy of functional site prediction, in fact, was far from reaching 100%. Applying ROC analysis we found that 47% of active sites, 20% of DNA/RNA binding sites, and 14% of protein–protein interfaces can be predicted at a 5% false positive rate. We note that the limited accuracy of functional prediction can be caused by the differences in functional specificity among homologous family members as well as by the functional plasticity of protein molecules. Even proteins sharing the same evolutionary origin and functional activity may show variability in the physicochemical properties of functional residues and their location in a 3D structure (Todd et al. 2001, 2002; Lichtarge and Sowa 2002).

Materials and methods

A benchmark for evaluating the methods of functional sites prediction

We selected 86 domain alignments from the curated Conserved Domain Database (CDD), a current version of which is available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2002). Multiple alignments in the CDD have been manually curated to reconcile sequence alignments with protein 3D structures and structure-structure alignments. Based on the crystal structures and experimental data from the literature, conserved functional sites have been annotated for each CDD domain by inspection of protein–ligand, protein–DNA/RNA, and protein–protein complexes for all structure representatives. Functionally important sites were defined as those residues making contacts with a ligand or a macromolecule. CDD alignments represent alignments of conserved core structures formed by presumably homologous sites, and positions outside the conserved cores are removed from the alignment, resulting in alignment lengths between 38 and 576 residues.

The selected test set covered a broad range of different functional categories including 37 domains with annotated catalytic sites, 17 domains with annotated DNA/RNA binding sites, 20 domains with annotated protein–protein binding sites, and domains from other functional groups (domains containing disulfide bonds and domains with less than two annotated functional sites were excluded). Names of CDD families used in the test set together with their sequence diversity, length, the number and the type of functional sites are listed in Table 2. By definition, CDD alignments have at least one structural family representative, whereas in our test set the number of structures per family ranged from 1 to 15, with three structures per family on average.

Calculation of sequence conservation

We used two different measures to estimate the level of conservation at each position in CDD alignments. The first measure, information content, was based on counting the number of different amino acid types per aligned column and inferring the relationships between amino acid types with the pseudocount method (Altschul et al. 1997), where pseudocount frequencies were calculated using the PAM70 amino acid substitution matrix. The second measure of evolutionary conservation of different sites, the substitution rate per site, was calculated using the PAML3.12 package (Yang 1997) with its implementation of the Jones, Taylor, and Thornton amino acid substitution model (Jones et al. 1992), where the variable substitution rates across sites were described with the γ-model. Phylogenetic trees required for this analysis were constructed by the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei 1987) with the PHYLIP package (Felsenstein 1989).

Scoring the clusters of conserved residues

For each position in the alignment, two regional conservation scores were calculated. The first one represented the average over conservation scores for residues located within a given distance from each position “i” of the alignment, namely,

|

(1) |

where Δij is equal to 1 if residues i and j are in contact, and 0 otherwise. Cj is the residue conservation score of residue j, N is the total number of positions in the alignment, and n is the number of residues in contact with residue “i.” Contacts were defined between the virtual Cβ atoms (points 2.4 Å away from Cα atom) of residues separated along the chain by at least five peptide bonds and having the distance less than a given distance cutoff (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 Å). It should be noted that contacts were calculated for all structural representatives of domain alignments, and only conserved contacts were used in the evaluation of Ccont. The contact between positions i and j was defined as conserved if aligned residues in these positions formed the contact in all structural representatives. For those residues which did not make any contacts, the original residue conservation value was assigned. Inter-residue contacts conserved between all structural representatives were shown to increase prediction accuracy for 60% of domain families (for families with more than one structure) compared to the scoring function based on one representative structure (data not shown).

The second regional conservation score gave emphasis to solvent accessible residues, because these residues are very often involved in the formation of functionally important interfaces:

|

(2) |

where Δsolv is equal to 1, if solvent accessibility of position “i” is greater than 0.05, and 0 otherwise. Reversing equation 2 and considering only buried residues in contact did not improve the prediction accuracy (data not shown). The cutoff threshold of 0.05 was derived from an analysis of homologous protein structures forming a conserved hydrophobic interior (Miller et al. 1987). Solvent-accessible area was calculated by the DSSP algorithm (Kabsch and Sander 1983), where solvent accessibility of residue “X” was defined as the ratio of its solvent-accessible area in protein structure to that for extended tripeptide Gly-X-Gly. The solvent accessibility of position “i” in a multiple alignment was calculated by averaging solvent accessibility values in a given position for all structural representatives.

Evaluation of prediction accuracy

To evaluate the accuracy of functional site predictions, we calculated the number of correctly predicted functional sites (true positives) and the number of incorrectly predicted functional sites (false positives) found at different thresholds of conservation score. True positives were identified as those functionally important sites which had scores higher than a given score threshold. False positives, in turn, were identified as sites with scores higher than a given threshold, but unrelated to the functional activity of a given domain family. To measure the performance of retrieval methods, the truncated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) has been widely used (Gribskov and Robinson 1996; Schaffer et al. 2001). A ROCn statistic was calculated as the sum of the number of true positives found at 1,2,3, . . . n false positive levels (ti) divided by the overall number of true positives (T): ROCn = (∑I=1, . . . , n ti)/nT. Here, the total number of true positives (T) was calculated as the total number of annotated functionally important sites in a given domain family, whereas the total number of false positives was equal to the difference between the total number of sites in the alignment and the number of functional sites annotated for a family. Knowing the number of true positives detected and overall number of true positives, it is possible to calculate the fraction of true positives detected and, correspondingly, the fraction of false positives detected, and plot them in the order of decreasing score threshold (see Fig. 2 ▶). The false positive cutoff “n” was set to 30, which corresponds approximately to the first quarter of false positives detected. In those cases where the prediction performance was compared for different families with the different numbers of false positives, the R0.05 was used.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Spouge, Ben Shoemaker, and Michael Galperin for helpful suggestions, and the NIH Intramural Research Program for support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03465504.

References

- Aloy, P., Querol, E., Aviles, F.X., and Sternberg, M.J. 2001. Automated structure-based prediction of functional sites in proteins: Applications to assessing the validity of inheriting protein function from homology in genome annotation and to protein docking. J. Mol. Biol. 311 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, M.A., Casari, G., Sander, C., and Valencia, A. 1997. Classification of protein families and detection of the determinant residues with an improved self-organizing map. Biol. Cybern. 76 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, G.J., Porter, C.T., Borkakoti, N., and Thornton, J.M. 2002. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J. Mol. Biol. 324 105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casari, G., Sander, C., and Valencia, A. 1995. A method to predict functional residues in proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J.M. 1998. Programming with data. A guide to the S language. Springer Verlag, New York.

- del Sol Mesa, A., Pazos, F., and Valencia, A. 2003. Automatic methods for predicting functionally important residues. J. Mol. Biol. 326 1289–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos, D. and Valencia, A. 2000. Practical limits of function prediction. Proteins 41 98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcock, A.H. 2001. Prediction of functionally important residues based solely on the computed energetics of protein structure. J. Mol. Biol. 312 885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP—Phylogeny inference package. Cladistics 5 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Gribskov, M. and Robinson, N.L. 1996. Use of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to evaluate sequence matching. Comput. Chem. 20 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannenhalli, S.S. and Russell, R.B. 2000. Analysis and prediction of functional sub-types from protein sequence alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 303 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi, H. and Gerstein, M. 1999. The relationship between protein structure and function: A comprehensive survey with application to the yeast genome. J. Mol. Biol. 288 147–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.T., Taylor, W.R., and Thornton, J.M. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. and Thornton, J.M. 1997. Prediction of protein–protein interaction sites using patch analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 272 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W. and Sander, C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf, R., Xenarios, I., and Eisenberg, D. 2001. Three-dimensional cluster analysis identifies interfaces and functional residue clusters in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 307 1487–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Shakhnovich, E.I., and Mirny, L.A. 2003. Amino acids determining enzyme-substrate specificity in prokaryotic and eukaryotic protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100 4463–4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtarge, O. and Sowa, M.E. 2002. Evolutionary predictions of binding surfaces and interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtarge, O., Bourne, H.R., and Cohen, F.E. 1996. An evolutionary trace method defines binding surfaces common to protein families. J. Mol. Biol. 257 342–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscombe, N.M. and Thornton, J.M. 2002. Protein–DNA interactions: Amino acid conservation and the effects of mutations on binding specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 320 991–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madabushi, S., Yao, H., Marsh, M., Kristensen, D.M., Philippi, A., Sowa, M.E., and Lichtarge, O. 2002. Structural clusters of evolutionary trace residues are statistically significant and common in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 316 139–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer, A., Panchenko, A., Shoemaker, B., Thiessen, P., Geer, L., and Bryant, S. 2002. CDD: A database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 281–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S., Janin, J., Lesk, A.M., and Chothia, C. 1987. Interior and surface of monomeric proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 196 641–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooren, I.M. and Thornton, J.M. 2003. Structural characterisation and functional significance of transient protein–protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 325 991–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchenko, A.R. and Bryant, S.H. 2002. A comparison of position-specific score matrices based on sequence and structure alignments. Protein Sci. 11 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N. and Nei, M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, A.A., Aravind, L., Madden, T.L., Shavirin, S., Spouge, J.L., Wolf, Y.I., Koonin, E.V., and Altschul, S.F. 2001. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 2994–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjolander, K. 1998. Phylogenetic inference in protein superfamilies: Analysis of SH2 domains. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 6 165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teichmann, S.A., Murzin, A.G., and Chothia, C. 2001. Determination of protein function, evolution, and interactions by structural genomics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd, A.E., Orengo, C.A., and Thornton, J.M. 2001. Evolution of function in protein superfamilies, from a structural perspective. J. Mol. Biol. 307 1113–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. Plasticity of enzyme active sites. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.J., Lin, S.L., Wolfson, H.J., and Nussinov, R. 1997. Studies of protein–protein interfaces: A statistical analysis of the hydrophobic effect. Protein Sci. 6 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. 1997. PAML: A program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13 555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]