Abstract

Yeast phosphatidylinositol transfer protein (Sec14p) function is essential for production of Golgi-derived secretory vesicles, and this requirement is bypassed by mutations in at least seven genes. Analyses of such ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants suggest that Sec14p acts to maintain an essential Golgi membrane diacylglycerol (DAG) pool that somehow acts to promote Golgi secretory function. SPO14 encodes the sole yeast phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-activated phospholipase D (PLD). PLD function, while essential for meiosis, is dispensable for vegetative growth. Herein, we report specific physiological circumstances under which an unanticipated requirement for PLD activity in yeast vegetative Golgi secretory function is revealed. This PLD involvement is essential in ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants where normally Sec14p-dependent Golgi secretory reactions are occurring in a Sec14p-independent manner. PLD catalytic activity is necessary but not sufficient for ‘bypass Sec14p’, and yeast operating under ‘bypass Sec14p’ conditions are ethanol-sensitive. These data suggest that PLD supports ‘bypass Sec14p’ by generating a phosphatidic acid pool that is somehow utilized in supporting yeast Golgi secretory function.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SEC14 gene product (Sec14p) plays an essential role in protein exit from the yeast Golgi complex and represents the major phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) transfer protein (PITP) of yeast (1, 2). The case for how Sec14p stimulates Golgi secretory function is derived primarily from analyses of mutations that permit efficient Golgi secretory activity (and cell viability) in the face of sec14 deletion mutations (1–10). Characterization of these ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations suggests that Sec14p maintains the integrity of a critical Golgi diacylglycerol (DAG) pool that is somehow required for Golgi secretory function (4, 7). This concept stems from two general findings (see Fig. 1). First, ‘bypass Sec14p’ is generated by genetic inactivation of the cytidine 5′-diphosphate (CDP)-choline pathway for phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) biosynthesis; a pathway that consumes DAG (3). Biochemical insight into this genetic relationship was provided by the demonstration that Sec14p is an inhibitor of the CDP-choline pathway (4, 5). Second, accelerated PtdIns-metabolism represents another in vivo mechanism for effecting a ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotype (7, 9). Consistent with those findings, the PtdIns-transfer activity of mammalian PITP is necessary for rescue of Sec14p defects (11), and both Sec14p and mammalian PITPs stimulate PtdIns metabolism in phosphoinositide-dependent reactions that have been reconstituted in permeabilized mammalian cells (12–15). Thus, Sec14p may also potentiate PtdIns metabolism in an action that would resupply the Golgi DAG pool (7).

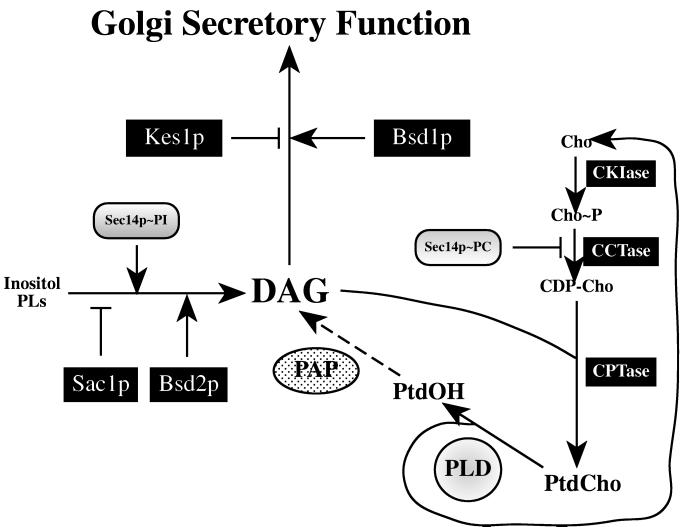

Figure 1.

A role for PLD in bypass of the essential Sec14p requirement for yeast Golgi membrane secretory function. The gene products identified by ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations are highlighted (black boxes), and their known (or inferred) physiological functions are indicated. CKIase (choline kinase; CKI1 gene product), CCTase (cholinephosphate cytidylyltransferase; PCT1 gene product), and CPTase (cholinephosphotransferase; CPT1 gene product) represent structural genes of the CDP-choline pathway for PtdCho biosynthesis. Loss-of-function mutations in each of these genes effect genetically recessive ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotypes (3). Likewise, loss-of-function for SacIp (SAC1 gene product) or Kes1p (KES1 gene product) represent recessive ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations (7, 8, 10). Genetically dominant ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations define the BSD1 and BSD2 genes (encode Bsd1p and Bsd2p, respectively). While kes1 and BSD1 mutations are suggested to act downstream of the DAG requirement for Golgi function (7, 10) and perhaps act to reduce the DAG requirement for Golgi secretory function, the remaining suppressors are proposed to act via Sec14p-independent maintenance of a Golgi DAG pool that is critical for Golgi-derived secretory vesicle biogenesis. DAG maintenance is promoted by decreased consumption via PtdCho biosynthesis (cki1, pct1, and cpt1) or by increased production via accelerated inositol phospholipid metabolism (sac1 and BSD2). These effects are proposed to fulfill the respective functions of PtdCho- and PtdIns-bound Sec14p (Sec14p∼PC and Sec14p∼PI) (4, 5, 7). None of these ‘bypass Sec14p’ modes is sufficient for Sec14p-independent Golgi secretory function in the absence of PLD. We propose that PLD may make sufficient PtdOH available to PAPs to provide the additional metabolic DAG input to support the ‘bypass Sec14p’ condition. Cho, choline; Cho∼P, choline-phosphate; CDP-choline, CDP-Cho.

Recently, it has been suggested that PtdIns-4,5-P2-stimulated phospholipase D (PLD) plays an essential role in promoting Golgi-derived vesicle budding, and that PITPs may function in such a regulatory loop by providing PtdIns to lipid kinases so as to fuel phosphoinositide synthesis (16). Localized enrichment of phosphoinositides might facilitate the proper spatial recruitment of vesicle coat proteins, thereby facilitating vesicle budding (17). A primary foundation for this hypothesis is the demonstration that the GTP-bound form of ADP-ribosylation factor synergizes with PtdIns-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns-4,5-P2) in stimulation of mammalian PLD activity (18, 19). Although this hypothesis is attractive, direct evidence for a physiological role for PLD in mammalian secretory pathway function remains lacking. Indeed, the sole PtdIns-4,5-P2-activated PLD in yeast, while essential for sporulation, is dispensable for vegetative growth (20). Sec14p is essential for the viability of vegetative cells (1, 2).

We now identify specific physiological circumstances under which PLD activity is essential for yeast Golgi secretory function. This obligate PLD requirement is recorded in ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants where normally Sec14p-dependent Golgi secretory reactions are occurring in a Sec14p-independent manner. The data indicate that generation of PtdOH likely defines the critical contribution of PLD to the ‘bypass Sec14p’ condition. The present body of evidence can be reconciled by one of two models: first, that PLD-generated PtdOH contributes to the critical Golgi membrane DAG pool by serving as substrate for PtdOH phosphohydrolases or, second, that DAG serves as precursor to a critical PtdOH pool.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and Genetic Techniques.

All yeast media have been described (21). Standard methods were employed for yeast transformation and gene disruption experiments (22, 23).

Yeast Strains.

The strains employed included: CTY182 (MATa ura3–52, lys2–801, Δhis3–200), CTY1–1A (CTY182 sec14–1ts), CTY100 (CTY1–1A sac1–26), CTY102 (CTY1–1A pct1–2), CTY124 (CTY1–1A BSD1–124), CTY159 (MATa ura3–52, lys2–801, Δhis3–200, sec14–1ts, kes1–1), CTY160 (MATa ura3–52, Δhis3–200, sec14–1ts, cki1–1), and CTY213 (MATa ura3–52, Δhis3–200, sec14–1ts, BSD2–1). Isogenic spo14Δ derivatives included: CTY1092 (CTY182 spo14Δ∷URA3), CTY1079 (CTY1–1A spo14Δ∷HIS3), CTY1127 (CTY100 spo14Δ∷HIS3), CTY1096 (CTY102 spo14Δ∷URA3), CTY1129 (CTY124 spo14Δ∷HIS3), CTY1098 (CTY159 spo14Δ∷URA3), CTY1099 (CTY160 spo14Δ∷URA3), and CTY1093 (CTY213 spo14Δ∷URA3). Strain CTY1122 (MATa ura3–52, lys2–801, Δhis3–200, ade2–101, leu2–3,-112, sec14–1ts, pct1–2, spo14Δ∷URA3) was employed in the complementation experiments involving mutant spo14 genes encoding the PLDΔN and catalytically inactive PLD polypeptides.

Invertase Secretion Index.

Invertase secretion indices were determined as described (24). In alcohol challenge experiments, ethanol (1.5% final concentration) was added to cells at the time of shift to 37°C and yeast extract/peptone (YP) (0.1% glucose) medium, and this ethanol concentration was maintained throughout the 2-hr postshift incubation.

Lipid Analyses.

Methods for radiolabeling yeast cells with [32P]orthophosphate and [14C]acetate in inositol and choline-containing medium, and accompanying methods for lipid analysis and quantitation, have been described (4, 7).

RESULTS

Rationale for Identifying Yeast Mutants Defective in PtdCho Turnover.

The Sec14p requirement for Golgi secretory function is relieved by genetic inactivation of the CDP-choline pathway for PtdCho biosynthesis (Fig. 1; ref. 3). This effect is observed regardless of whether the CDP-choline pathway contributes to net PtdCho synthesis (e.g., when yeast are grown in choline-replete medium), or whether it functions solely in choline salvage when yeast are cultured in choline-free media (yeast cannot synthesize choline de novo) (3). Mutants exhibiting ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotypes only in choline-free media should exhibit defects in cellular functions devoted to PtdCho turnover and liberation of choline. A candidate for such a function was PLD, the SPO14 gene product, which hydrolyzes PtdCho to choline and PtdOH (20).

A spo14Δ∷HIS3 disruption allele was introduced into sec14–1ts strains, and these double mutants were assessed for choline-remedial ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotypes. Surprisingly, spo14Δ∷HIS3 failed to suppress sec14–1ts mutations, regardless of the choline content of the growth medium. Instead, PLD deficiency exacerbated Sec14p growth and secretory defects when sec14–1ts strains were incubated at semipermissive temperatures. While sec14–1ts, SPO14 strains grew well at 33.5°C, this temperature was restrictive for growth of isogenic sec14–1ts, spo14Δ strains (not shown). Consistent with these results, plasmid-curing experiments further demonstrated that spo14Δ∷HIS3 also failed to suppress sec14 null mutations. These data suggested that PLD might not represent the sole mechanism by which free choline could be generated in vegetative cells and revealed a refinement to the genetic screen for yeast mutants defective in choline generation. This refinement was to repeat the screen with a sec14–1ts, spo14Δ∷HIS3 parental strain deficient in PLD activity.

Revertants of a sec14–1ts, spo14Δ∷HIS3 strain that grew at 37°C in choline-free media were selected. Such sec14–1ts pseudorevertants normally are recovered easily, and these invariably represent ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations that suppress the lethality of sec14 null mutations (3, 8). Surprisingly, the sec14–1ts, spo14Δ∷HIS3 strain yielded very few revertants at 37°C, and this result was obtained when either complex or minimal growth media (+ or − choline) were employed (Fig. 2A). The spontaneous reversion frequency was at least 500-fold lower for the sec14–1ts, spo14Δ∷HIS3 strain (<1 × 10−8/cell per generation) relative to the isogenic SPO14, sec14–1ts strain (ca. 5 × 10−6/cell per generation). These data demonstrated that facile recovery of ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants required a wild-type SPO14 gene.

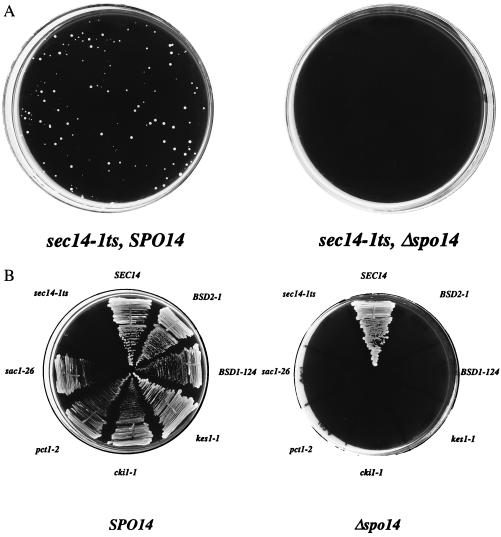

Figure 2.

(A) Reversion frequencies for sec14–1ts in SPO14 and Δspo14∷HIS3 yeast strains. CTY1–1A (sec14–1ts, SPO14) and CTY1079 (sec14–1ts, Δspo14∷HIS3) were spread onto yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YPD) agar and incubated at 37°C (restrictive for sec14–1ts) for 72 hr. The sec14–1ts, SPO14 strain readily reverted to Ts+ while the isogenic spo14Δ∷HIS3 strain failed to do so. Detailed strain genotypes are provided in the Materials and Methods. (B) ‘Bypass Sec14p’ requires PLD function. Isogenic pairs of SPO14 and Δspo14 yeast strains (as indicated) were incubated on YPD agar at 37°C for 72 hr. This temperature is permissive for SEC14 wild-type yeast, irrespective of whether the strains are SPO14 or spo14Δ:, but is restrictive for growth and secretory function for the isogenic sec14–1ts derivatives. The sec14-associated growth defect at 37°C is suppressed in sec14–1ts, SPO14 strains by the indicated ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations (sac1–26, pct1–2, cki1–1, kes1–1, BSD1–124, and BSD2–1, respectively). Isogenic spo14Δ strains fail to ‘bypass Sec14p’ as judged by their inability to grow at 37°C. This growth defect is abolished by introduction of a wild-type SEC14 allele to these strains. SPO14 strains included: CTY182 (SEC14), CTY1–1A (sec14–1ts), and the ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutant strains were CTY100 (sec14–1ts, sac1–26), CTY102 (sec14–1ts, pct1–2), CTY160 (sec14–1ts, cki1–1), CTY159 (sec14–1ts, kes1–1), CTY124 (sec14–1ts, BSD1–124), and CTY213 (sec14–1ts, BSD2–1). The respective spo14Δ strains were CTY1092, CTY1079, CTY1127, CTY1096, CTY1099, CTY1098, CTY1129, and CTY1093. Detailed strain genotypes are provided in the Materials and Methods.

A Functional SPO14 Gene Is Required for Manifestation of ‘Bypass Sec14p’ Phenotypes.

To determine whether PLD represents an essential component of the mechanism(s) by which known classes of ‘bypass Sec14p’ alleles exerted their suppressor phenotypes (see Fig. 1), we introduced spo14Δ alleles into sec14–1ts strains harboring individual ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations. These PLD-deficient derivative strains then were analyzed for their abilities to grow and secrete under Sec14p-deficient conditions. As shown in Fig. 2B, ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations overcame sec14–1ts-associated growth defects only in the context of a SPO14 genetic background. Introduction of spo14Δ alleles abolished the suppressor phenotype of each ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutation and reimposed the essential Sec14p requirement for cell viability to each yeast strain.

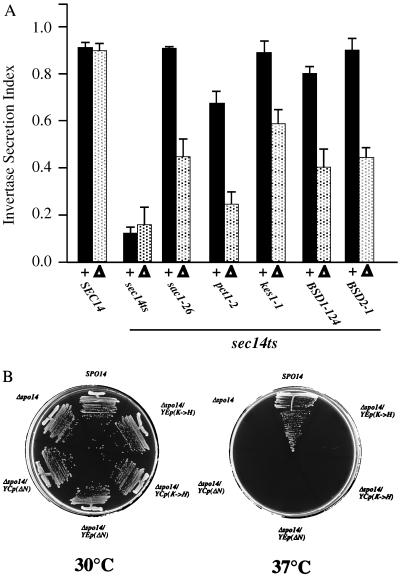

This PLD requirement for ‘bypass Sec14p’ was recapitulated in assays assessing secretory pathway function. Wild-type strains grown at 37°C exhibited a secretion index (0.87 ± 0.03) that indicated efficient trafficking of invertase through the secretory pathway to the cell surface (Fig. 3A). This efficiency was not compromised by introduction of a spo14Δ allele, indicating that PLD insufficiency exerted no ill effect on Golgi secretory function in yeast expressing wild-type Sec14p. By contrast, an isogenic sec14–1ts strain exhibited a secretion index of only 0.13 ± 0.02. This value was diagnostic of a major intracellular pool of invertase that was blocked in transit from the yeast Golgi complex (1, 3, 24, 25). Introduction of a spo14Δ allele again had no effect on the magnitude of the sec14–1ts secretory block. ‘Bypass Sec14p’ mutations permit Sec14p-independent Golgi secretory function, and this effect was reflected in the elevated secretion indices measured for the corresponding mutants. These values ranged from 0.90 ± 0.05 to 0.62 ± 0.06 and substantially exceeded those determined for the isogenic sec14–1ts strain at 37°C (Fig. 3A). Indeed, these secretion indices approached those measured for wild-type yeast strains. However, spo14Δ derivatives of the ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains exhibited significant reductions (ca. 2-fold) in secretion index relative to their PLD-sufficient partners, indicating reimposition of a sec14 secretory block. We noted that the secretion indices of the PLD-insufficient ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains reproducibly exceeded those of the sec14–1ts control (Fig. 3A). Such data suggest that genetic inactivation of PLD did not abolish the effects of individual ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutations, but that it reduced these effects to below the threshold levels of Golgi function required to sustain cell viability.

Figure 3.

(A) Efficiency of invertase secretion in wild-type, sec14–1ts, and ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains as a function of PLD. The secretion index measures invertase secretion efficiency at 37°C (24). Wild-type and sec14–1ts parental strains indicate secretory efficiency under Sec14p-proficient and deficient conditions, respectively, while the secretion indices of the various ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains quantitate the efficiency with which the indicated mutations suppress sec14–1ts-associated secretory defects. The SPO14 strain data are presented as solid bars and indicated (+) below them (n ≥ 4). The spo14Δ strain data are presented as stippled bars and indicated (Δ) below them (n ≥ 4). Strains are described in Fig. 2B. (B) PLD catalytic activity is not sufficient for ‘bypass Sec14p’. A set of isogenic sec14–1ts, pct1–2 strains were streaked for single colonies on YPD medium and incubated for 48 hr at the indicated temperatures. The SPO14 derivative (CTY102) served as a positive ‘bypass Sec14p’ control (robust growth at 37°C) while the spo14Δ derivative (CTY1096) represented the ‘bypass Sec14p’-incompetent control (no growth at 37°C). Complementation of spo14Δ in the ‘bypass Sec14p’ context was assessed for low-copy (YCp) and high-copy (YEp) configurations of the spo14ΔN allele (indicated as ΔN; encodes a catalytically active PLD that fails to undergo localization to the nuclear membrane during meiosis; ref. 26) and the spo14K→H allele (encodes catalytically inactive PLD; refs. 20 and 28).

As another measure of Golgi secretory function, pulse-radiolabeling studies (10) were employed to monitor carboxypeptidase Y (CPY) delivery to the yeast vacuole in SPO14 and spo14Δ derivatives of ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains. Consistent with the invertase results, CPY trafficking through the Golgi complex to the vacuole proceeded at wild-type rates for SEC14, SPO14 and SEC14, spo14Δ strains. SPO14 derivatives of ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains also exhibited wild-type rates of CPY delivery to the vacuole when operating under Sec14p-proficient conditions. However, PLD dysfunction in ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains lacking functional Sec14p imposed kinetics for CPY trafficking from the Golgi complex to the yeast vacuole that were intermediate between those recorded at 37°C for sec14–1ts and wild-type strains (not shown).

Catalytic Activity Is Necessary But Not Sufficient For ‘Bypass Sec14p’.

We employed genetic methods to assess the relationship between PLD catalytic activity and ‘bypass Sec14p’. Participation of PLD in sporulation requires both catalytic activity and its redistribution from a diffuse localization to membranes (26). Deletion of the PLD N terminus yields an active enzyme (PLDΔN) that is nonfunctional in promoting meiosis because it fails to relocalize (26). We tested whether PLDΔN expression from either low- or high-copy plasmids fulfilled the PLD requirement for ‘bypass Sec14p’. As shown in Fig. 2B, neither configuration for PLDΔN expression restored Sec14p-independent growth to spo14Δ derivatives of ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants. Thus, PLD catalytic activity was insufficient for support of ‘bypass Sec14p’.

Mutations that inactivate PLD catalytic activity without compromising relocalization have been described (26, 27). One such allele, spo14K→H, disturbs an HKD motif that has been proposed to participate directly in catalysis of choline scission from PtdCho (27, 28). To determine whether PLD catalytic activity was necessary for Sec14p-independent Golgi function in bypass Sec14 mutants, YCp(spo14K→H) and YEp(spo14K→H) plasmids were introduced into Δspo14∷HIS3 derivatives of ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains. Again, both configurations of spo14K→H failed to impart Sec14p-independent growth to spo14Δ derivatives of ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants (Fig. 3B). Both PLDΔN and the catalytically inactive spo14K→H PLD are expressed as full-length polypeptides that exhibit reasonable stability in vivo (26). These data demonstrated that PLD catalytic activity was necessary, but not sufficient, for ‘bypass Sec14p’. PLD localization was also of functional importance.

Ethanol Challenge Imparts Growth and Secretory Defects to ‘Bypass Sec14p’ Mutants Operating Under Sec14p-Deficient Conditions.

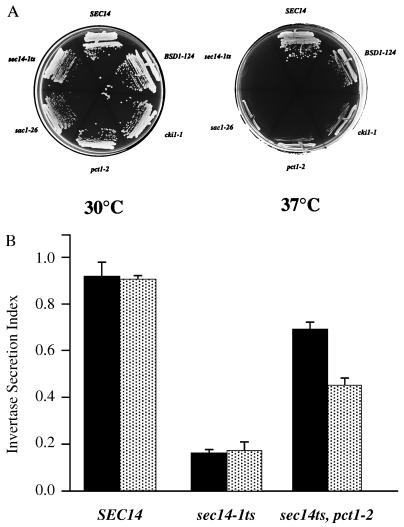

PLD activity might support ‘bypass Sec14p’ because it reduces PtdCho levels in Golgi membranes (3). Alternatively, PLD might generate a lipid precursor that is limiting in the Golgi membranes of Sec14p-deficient cells (4, 7, 9). We wished to address which effect defined the relevant contribution of PLD to ‘bypass Sec14p’. PLD catalyzes PtdCho hydrolysis to choline and PtdOH via a transphosphatidylation reaction that employs water as nucleophile (27, 29). Primary alcohols (e.g., ethanol) compete with water in this reaction and result in production of both PtdOH and phosphatidylalcohol as reaction products (29). We tested whether challenge of PLD-proficient ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains with sublethal concentrations of ethanol elicited pharmacological reimposition of a Sec14p requirement for cell viability. As expected, introduction of ethanol (3% vol/vol) into glucose-containing complex media was not detrimental to the growth of wild-type yeast or ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains harboring functional Sec14p. However, such an ethanol challenge was strongly growth inhibitory to these same ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains operating under conditions of Sec14p deficiency (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) ‘Bypass Sec14p’ strains are sensitive to ethanol under conditions of Sec14p insufficiency. Yeast strains were streaked on YPD agar in the presence of 3% ethanol and incubated at either 30°C or 37°C for 72 hr. The wild-type and sec14–1ts strains (CTY182 and CTY1–1A, respectively) served as (+) and (−) growth controls for the sec14–1ts-restrictive temperature of 37°C. The representative ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants (all harboring sec14–1ts) grew well at the sec14–1ts-permissive temperature of 30°C, but grew only poorly at the sec14–1ts-restrictive temperature of 37°C. These strains grow well on YPD at 37°C (see Fig. 2B). (B) Ethanol reimposes a secretory defect to ‘bypass Sec14p’ strains. Secretory indices were measured essentially as described in Fig. 2A for the following SPO14 strains: wild-type (CTY182); sec14–1ts (CTY1–1A); sec14–1ts, pct1–2 (CTY102). The experimental procedure was modified by splitting each culture into two equal aliquots at the time of shift to 37°C and YP (0.1%) glucose medium, with one aliquot challenged with ethanol (1.5% final concentration), and the other left unchallenged. The data (n ≥ 5) for the unchallenged (−) and the challenged (+) samples are given in solid and stippled bars, respectively.

We also measured the efficiency of invertase secretion, as a function of ethanol challenge, for pct1 strains (Fig. 4B). Ethanol diminished secretory pathway function in the pct1–2 ‘bypass Sec14p’ strain, but not in its isogenic SEC14 or otherwise wild-type sec14–1ts strains. Although yeast PLD is not as proficient as mammalian PLD in utilizing ethanol for transphosphatidylation (20), and phosphatidylethanol is metabolized by yeast (not shown), ethanol (1.5% vol/vol) elicited a 39% reduction in the secretory competence of the ‘bypass Sec14p’ strain at 37°C (Fig. 4B). This modest difference was significant (>99.9% confidence level by Student’s t test), and the ethanol-mediated reduction in the Sec14p-independent secretion efficiency of the pct1–2 strain was ca. 50% of that recorded with spo14Δ (see Fig. 3A). These results suggest that PtdOH production, and not hydrolysis of PtdCho per se, represents the critical PLD activity required for the ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotype.

Bulk PtdOH Levels Are Sensitive to PLD Activity.

To assess whether PLD activity resulted in measurable increases in bulk PtdOH content, we radiolabeled SPO14 or spo14Δ derivatives of pct1–2, sec14–1ts and sac1–26, sec14–1ts yeast strains to steady-state with [32P]orthophosphate, washed the cells, and shifted the cells to label-free medium for a 2-hr chase at 33.5°C. This temperature is semipermissive for sec14–1ts. Phospholipids subsequently were extracted and analyzed. Bulk PtdOH levels were increased significantly in the SPO14 strains (2.2 ± 0.2% of total phospholipid and 1.8 ± 0.6% of total phospholipid for pct1 and sac1 strains; n = 3) relative to the spo14Δ derivatives (0.5 ± 0.1% and 0.4 ± 0.1% of total phospholipid pct1 and sac1 strains; n = 3). This experimental protocol was repeated for measurement of bulk DAG by [14C]acetate radiolabeling. Bulk membrane DAG levels were not increased significantly in SPO14 strains (12.2 ± 0.9% and 17.9 ± 0.7% of total chloroform-soluble counts for sac1 and pct1 strains; n = 3) relative to spo14Δ derivatives (12.2 ± 1.6% and 18.9 ± 0.7% of total chloroform-soluble counts for sac1 and pct1 strains, respectively; n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Because ADP-ribosylation factor stimulates mammalian PLD activity in vitro (18, 19), PtdOH has been speculated to be a critical stimulator of vesicle budding in a regulatory pathway that also employs PITP (16). Indeed, PtdOH contributes an important, but undefined function for efficient protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the mammalian Golgi complex (30–32). Yet, yeast PLD is insensitive to activation by ADP-ribosylation factor (33) and is nonessential for secretory pathway function. Thus, yeast and mammalian PLDs might execute distinct physiological functions. A caveat remains, however. Yeast exhibit a PtdIns-4,5-P2-insensitive PLD activity of undetermined function that, while exhibiting biochemical properties quite distinct from those of the SPO14 gene product, might yet share some functional redundancy with it (34).

We demonstrate that PtdIns-4,5-P2-stimulated PLD activity intersects with secretory pathway function under special circumstances. Specifically, PLD is essential for the Sec14p-independent Golgi function of ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants. These data are in accord with the observation that PLD is somehow required for cki1-mediated ‘bypass Sec14p’ (35). We also provide evidence that this requirement involves generation of PtdOH that is required for Sec14p-independent survival of ‘bypass Sec14p’ mutants. Since increased SPO14 gene dosage fails to suppress Sec14p deficiencies in otherwise wild-type yeast (not shown), PLD must somehow be activated under ‘bypass Sec14p’ conditions to generate PtdOH. Such enhancement could occur at the level of PLD expression, specific activity, or localization, or PtdCho might become more accessible to PLD under ‘bypass Sec14p’ conditions.

Because PLD is dispensable for vegetative growth and secretion in the presence of Sec14p, but is required for maintenance of ‘bypass Sec14p’, PLD activity recapitulates Sec14p function in a meaningful way. One interpretation of these PLD data is that PtdOH, not DAG, is the key lipid effector for Sec14p-dependent Golgi secretory function. The proposed DAG requirement thereby is explained by DAG serving as a precursor to PtdOH (7, 34). A prediction of this model is that DAG kinase activity represents an important supporting activity for ‘bypass Sec14p’. Yet, expression of E. coli DAG kinase in yeast specifically exacerbates sec14 phenotypes and abolishes ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotypes (7). In addition, there is as yet no evidence to indicate that yeast can convert DAG to PtdOH. Inspection of the yeast genome fails to identify genes with eukaryotic DAG kinase signatures or with similarities to E. coli DAG kinase. Biochemical demonstration of yeast DAG kinase activity also remains elusive (not shown).

An alternative possibility is that PLD-generated PtdOH serves as a precursor for DAG production and that PLD activity defines one of several sources of metabolic input that help supply the essential Golgi membrane DAG pool under conditions of Sec14p insufficiency. By this model, yeast PtdOH-phosphohydrolases (PAPs) function downstream of PLD by converting PtdOH to DAG (Fig. 1). Two lipid pyrophosphatases have been described recently that exhibit Mg2+-independent PAP activity in vitro, and double-null strains exhibit increased bulk PtdOH levels (36). Yet, such double-null strains do not exhibit ‘bypass Sec14p’ phenotypes, nor are such strains compromised for ‘bypass Sec14p’ (not shown). Biochemical data indicate that yeast exhibit additional, and as yet uncharacterized, Mg2+-dependent and Mg2+-independent PAP activities (ref. 36; not shown). The acid test for a PAP involvement in ‘bypass Sec14p’ requires a molecular description of the entire yeast PAP repertoire so that appropriately deficient strains can be analyzed.

In summary, we find that PLD is required for ‘bypass Sec14p’ in yeast and that this condition correlates with increases in bulk membrane PtdOH. The issue of whether DAG, PtdOH, or both lipids are required for Sec14p-dependent Golgi functions remains an open question.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to George Carman (Rutgers University) for helpful discussions, for sharing data before publication, and for plasmid reagents. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM44530 to V.A.B. J.E. and P.C.S. were also supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PtdCho

phosphatidylcholine

- PtdIns

phosphatidylinositol

- PtdOH

phosphatidic acid

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- PITP

PtdIns transfer protein

- Sec14p

yeast PITP

- PLD

phospholipase D

- PAP

PtdOH-phosphohydrolase

- YPD

yeast extract/peptone/dextrose

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1. Bankaitis V A, Malehorn D E, Emr S D, Greene R. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1271–1281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bankaitis V A, Aitken J R, Cleves A E, Dowhan W. Nature (London) 1990;347:561–562. doi: 10.1038/347561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleves A E, McGee T P, Whitters E A, Champion K M, Aitken J R, Dowhan W, Goebl M, Bankaitis V A. Cell. 1991;64:789–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90508-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGee T P, Skinner H B, Whitters E A, Henry S A, Bankaitis V A. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:273–287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skinner H B, McGee T P, McMaster C, Fry M R, Bell R M, Bankaitis V A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:112–116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleves A E, McGee T P, Bankaitis V A. Trends Cell Biol. 1991;1:30–34. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(91)90067-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearns B G, McGee T P, Mayinger P, Gedvilaite A, Phillips S E, Kagiwada S, Bankaitis V A. Nature (London) 1997;387:101–105. doi: 10.1038/387101a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleves A E, Novick P J, Bankaitis V A. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2939–2950. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagiwada S, Kearns B G, McGee T P, Fang M, Hosaka K, Bankaitis V A. Genetics. 1996;143:685–697. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang M, Kearns B G, Gedvilaite A, Kagiwada S, Kearns M, Fung M K Y, Bankaitis V A. EMBO J. 1996;15:6447–6459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alb J G, Jr, Gedvilaite A, Cartee R T, Skinner H B, Bankaitis V A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8826–8830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay J C, Martin T F J. Nature (London) 1993;366:572–575. doi: 10.1038/366572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas G M H, Cunningham E, Fensome A, Ball A, Totty N F, Truong O, Hsuan J J, Cockroft S. Cell. 1993;74:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay J C, Fissette P L, Jenkins G H, Fukami K, Takenawa T, Anderson R A, Martin T F J. Nature (London) 1995;374:173–177. doi: 10.1038/374173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham E, Tan S K, Swigart P, Hsuan J, Bankaitis V A, Cockroft S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6589–6593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liscovitch M, Cantley L C. Cell. 1996;81:659–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka K, Orci L, Amherdt M, Bednarek S Y, Hamamoto S, Schekman R, Yeung T. Cell. 1998;93:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown H A, Gutowski S, Moomaw C R, Slaughter C, Sternweis P C. Cell. 1993;75:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90323-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cockroft S, Thomas G M, Fensome A, Geny B, Cunningham E, Gout I, Hiles I, Totty N F, Truong O, Hsuan J J. Science. 1994;263:523–526. doi: 10.1126/science.8290961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose K, Rudge S A, Frohman M A, Morris A J, Engebrecht J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:12151–12155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman F, Fink G R, Hicks J B. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1983. pp. 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothstein R J. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salama S R, Cleves A E, Malehorn D E, Whitters E A, Bankaitis V A. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4510–4521. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4510-4521.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Cell. 1980;21:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudge S A, Morris A J, Engebrecht J. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:81–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung T-C, Roper K, Zhang Y, Rudge S, Temel R, Hammond S M, Morris A J, Moss B, Engebrecht J, Frohman M A. EMBO J. 1997;16:4519–4530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colley W C, Sung T C, Roll R, Jenco J, Hammond S M, Altshuller Y, Bar-Sagi D, Morris A J, Frohman M A. Curr Biol. 1997;7:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heller M. Adv Lipid Res. 1978;16:267–326. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-024916-9.50011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ktistakis N T, Brown H A, Waters M G, Sternweis P C, Roth M G. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:295–306. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bi K, Roth M G, Ktistakis N T. Curr Biol. 1997;7:301–307. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddhanta A, Shields D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17995–17998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.17995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudge S A, Cavenagh M M, Kamath R, Sciorra V, Morris A J, Kahn R A, Engebrecht J. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2025–2036. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waksman M, Tang X, Eli Y, Gerst J E, Liscovitch M. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:36–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sreenivas A, Patton-Vogt J L, Bruno V, Griac P, Henry S A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16635–16638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toke D A, Bennett W L, Oshiro J, Wu W-I, Voelker D R, Carman G M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14331–14338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]