Abstract

A protein showing strong antiviral activity against Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV) was purified from the digestive juice of B. mori larvae. A homology search of the deduced amino acid sequence of the protein cDNA revealed 56% homology with Drosophila melanogaster lipase and 21% homology with human lipase. As lipase activity of the protein was confirmed in vitro, this protein was designated Bmlipase-1. Northern blot analysis showed that the Bmlipase-1 gene is expressed in the midgut but not in other tissues, nor is it activated by BmNPV infection. In addition, the Bmlipase-1 gene was shown not to be expressed in the molting and wandering stages, indicating that the gene is hormonally regulated. Our results suggest that an insect digestive enzyme has potential as a physiological barrier against BmNPV at the initial site of viral infection.

Insects exhibit effective immune system measures such as humoral and cellular responses against microbial infection (4). Insect immunity in antibacterial reactions has been the most extensively studied (7, 8, 13). On the other hand, little is known about insect immunity against viruses (16). Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus (BmNPV) is a most significant virus in the sericultural industry, often causing severe economic damages. The immune mechanisms of B. mori against this virus remain totally obscure.

The infection cycle of BmNPV is mediated by two phenotypically different viral particles: the occlusion-derived virus (ODV) and the budded virus (BV) (9). Occlusion bodies consisting of a crystalline matrix of polyhedron proteins contain ODV particles. When the occlusion bodies are ingested by B. mori larvae, they are dissolved by the alkaline gut juice. The enveloped virions are released and then initiate infection in the midgut columnar epithelial cells. In the case of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus, it was shown that a proportion of the parental virus travels through the midgut epithelial layer, possibly utilizing the plasma membrane reticular system, and enters the hemocoel at the same time, infecting the hemocytes (3). In contrast to ODV, the BV particle consists of a single nucleocapsid surrounded by an envelope acquired as it buds from the plasma membrane of an infected cell and spreads beyond the midgut through the tracheae.

Studies on antiviral immunity in insects are still in their infancy, and defense mechanisms at an early stage of viral infection in the alimentary canal remain unknown. The aim of the present study was to determine whether B. mori contains proteins showing anti-BmNPV activity in the gut in order to obtain a clue as to the antiviral mechanisms involved in insect immunity.

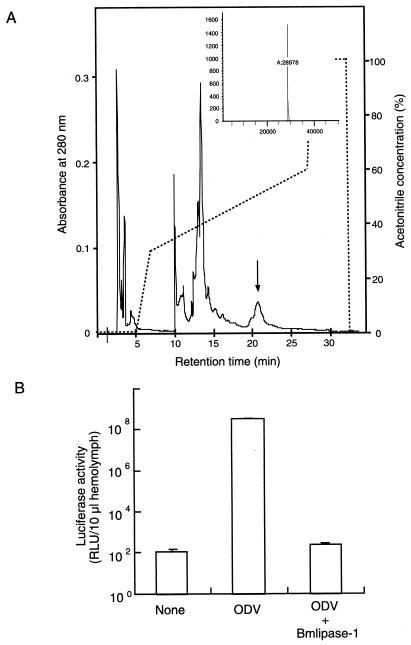

A protein showing anti-BmNPV was purified through ammonium sulfate fractionation, gel filtration, and reverse-phase high-performance liquid-column chromatography (HPLC) (Fig. 1A). The protein was eluted with 49.5% acetonitrile-0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) by reverse-phase HPLC. The homogeneity of the antiviral peak fraction was examined both by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) using a Voyager RP biospectrometry system (PerSeptive Biosystems) and by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) using a Series 1100MSD (Hewlett-Packard). The results showed no contamination of this protein fraction (Fig. 1A, inset). The molecular mass of this protein was calculated to be 28,988 Da by MALDI-TOF MS and 28,978 Da by LC-MS. The protein showed strong antiviral activity against ODV of BmNPV (Fig. 1B). All fifth-instar larvae inoculated with ODV (22.5 ng/larva) treated with this protein (2.2 μg/larva) entered the pupal stage, although all control larvae inoculated with nontreated ODV died within 168 h postinfection (hpi) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Final HPLC purification profile and antiviral activity of Bmlipase-1. (A) Purification profile of Bmlipase-1. Bmlipase-1 was eluted with 49.5% acetonitrile-0.05% TFA by reverse-phase HPLC. The arrow indicates the Bmlipase-1 position. The inset shows the LC-MS spectrum with molecular mass of Bmlipase-1. B. mori larvae of the Daizo race were reared on mulberry leaves, whereas larvae of the Tokai × Asahi race were fed an artificial diet (Nihonnosanko). The silkworms were maintained in the silkworm rearing room under controlled environmental conditions at 27°C. The digestive juice was collected from B. mori (Daizo race) larvae in an ice-cold tube by mild electric shock, and ammonium sulfate was added to give a 40% saturation. The precipitate was suspended in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and treated with 50% n-butanol (final concentration) overnight at 4°C, and the lower aqueous layer was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min. Half-volume ice-cold acetone was added to this solution to precipitate proteins in the aqueous layer. The precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min, dried, and dissolved in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The solution equilibrated with the same buffer was applied to a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column attached to a fast-performance liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia). Each fraction was tested for antiviral activity. Antiviral fractions were further purified through a reverse-phase column, Sephasil C8 SC 2.1/10, attached to a SMART system (Pharmacia) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile-0.05% TFA. (B) Antiviral activity against BmNPV-ODV. Infectivity was expressed as relative light units/10 μl of hemolymph. The data shown are means ± standard deviations of results from five experiments. The infectivity of BmNPV treated with 2.2 μg of Bmlipase-1 per larva (indicated as ODV + Bmlipase-1) was compared to that of nontreated BmNPV (indicated as ODV). As a negative control, the same amount of hemolymph from nontreated B. mori larvae was used to measure the background levels of luciferase activity (indicated as None). The ODV concentration was22.5 ng/larva. Luciferase activity was measured at 136 hpi. The antiviral activity was assayed using BmNPVp10luc, which contained a luciferase reporter gene driven by the p10 promoter (15). The recombinant BmNPV was a gift from Shuichiro Tomita from our institute. The virus expresses a luciferase reporter gene at 15 hpi. The infection and mortality levels were quantified in the Tokai × Asahi race. The ODV was purified by ultracentrifugation on sucrose gradient (14). The ODV (22.5 ng/larva) suspension was mixed with the purified protein (2.2 μg/larva) and dissolved in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). This mixture was incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Fifth-instar larvae just after ecdysis were orally inoculated with 5 μl of ODV mixture. Thirty larvae were used for each treatment. The hemolymph was collected at various hpi and assayed for luciferase activity. Ten microliters of hemolymph was added to 50 μl of luciferase assay buffer (Promega), and luciferase activity was measured using a Luminocounter 700 (Microtech-Nition).

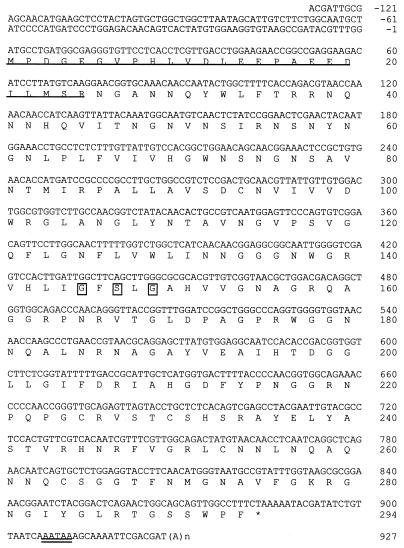

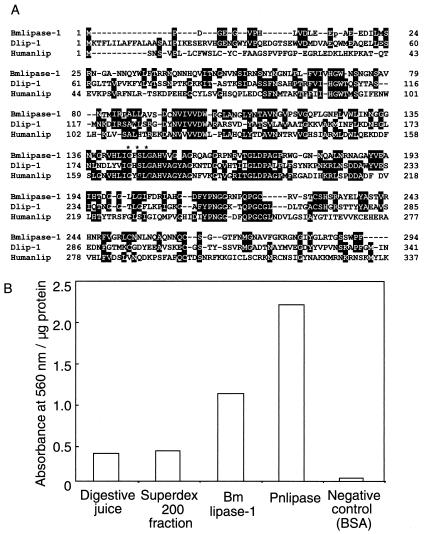

A partial N-terminal amino acid sequence (NH2-NGANNQYWLFTRRNQNNHQVITNGNVNSI) of the protein was determined by using a 492cLc protein sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). This sequence was identical to that of an expressed sequence tag (EST) clone. The complete nucleotide sequence of the protein was determined based on the EST clone designated mg809 (Fig. 2). The molecular mass of the deduced amino acid sequence was calculated to be 28,974 Da, coincident with the masses as measured by MALDI-TOF MS and LC-MS. A computer-aided homology search for the deduced amino acid sequence of this protein showed 56% homology with Drosophila melanogaster lipase (1) and 21% with human lipase (6) (Fig. 3A). The amino acid residues for the active site of the lipase family (GXSXG) (10), where X is any amino acid residue, were completely conserved. Thus, lipase activity was examined to confirm that the purified protein has biological activity consistent with a lipase. The results showed that the protein has lipase activity (Fig. 3B), suggesting that a lipase is involved in immune mechanisms against viral infection in the alimentary canal. This protein was therefore designated Bmlipase-1. A Bmlipase-1 analogue cDNA was also cloned. The deduced amino acid sequence of this clone showed 71.3% homology with that of Bmlipase-1 (data not shown), suggesting that Bmlipase-1 forms a gene family.

FIG.2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of Bmlipase-1 cDNA. The putative signal sequence of purified Bmlipase-1 is underlined. Boxed amino acid residues denote the active site of the lipase family (10). An asterisk shows the termination codon (TAA). The polyadenylation signal is double-underlined. B. mori EST database (Silkbase; http://www.ab.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/silkbase/) was screened based on the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified protein. A clone (mg809) isolated from the midgut cDNA library showed homology with this protein. The nucleotide sequence of the mg809 clone, kindly provided by Kazuei Mita from our institute, was determined to lack the sequence of the 5′ region. Complete nucleotide sequence was obtained by a First Choice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion) using mRNA extracted from the midgut and purified by a Quick Prep mRNA kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The nucleotide sequence was determined by dye-terminator cycle sequencing using a DNA sequencer (ABI 373A).

FIG. 3.

Structural and functional properties of Bmlipase-1. (A) Comparison of the amino acid sequence of Bmlipase-1 with that of D. melanogaster lipase (accession number AE003759-4) (1) and human lipase (6). The amino acid sequence from positions 338 to 500 of human lipase is omitted. Identical amino acid residues are boxed in black. The active site of the lipase family (GXSXG) is shown with asterisks. (B) Lipase activity measurement. The data shown are a typical result of three independent experiments. Lipase activity of both nonpurified digestive juice and Superdex 200 fraction is also shown. As positive and negative controls, Phycomyces nitens lipase (Pnlipase) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were used, respectively. The protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. Lipase activity was assayed according to the method of Arreguin-Espinosa et al. (2). P. nitens lipase was obtained from Wako. Lipase activity was measured at 560 nm and is expressed per milligram of protein.

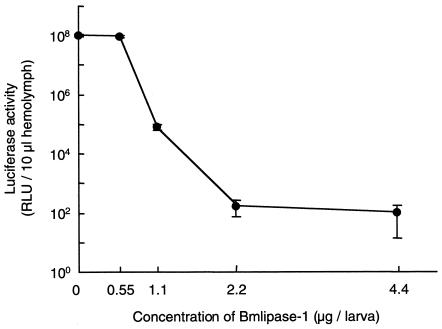

In the final purification, 66 μg of the pure Bmlipase-1 was obtained from digestive juice of 200 B. mori larvae (data not shown), indicating that a larva contains approximately 0.33 μg of Bmlipase-1 in the digestive juice. The effect of Bmlipase-1 concentration on a fixed amount of ODV (860 ng/larva) was examined (Fig. 4). The results showed that ODV treated with more than 2.2 μg of Bmlipase-1 per larva cannot propagate at all (Fig. 4), and mortality at this concentration was 0% (data not shown). The 50% lethal dose of ODV was also calculated to be 12.0 ng/larva, with 95% confidence limits between 10.6 and 13.7 ng/larva, by the computer program PriProbit (version 1.63) by M. Sakuma (data not shown). These results indicate that endogenous Bmlipase-1 (0.33 μg/larva) can suppress infection with up to 128.7 ng of ODV per larva. However, 100% mortality was observed in larvae infected with 22 ng of ODV per larva. In the case of larvae infected with less than 5.5 ng of ODV per larva, the mortality was 0% (data not shown), suggesting that antiviral factors, including Bmlipase-1, work well when ODV concentration is less than 5.5 ng/larva. The reasons that silkworm larvae are not resistant to infection with ODV at concentrations of up to 128.7 ng/larva remain unknown. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that the silkworm is resistant to ODV infection at concentrations of less than 5.5 ng/larva.

FIG. 4.

Effect of Bmlipase-1 on BmNPV-ODV infectivity. ODV infectivity was examined after treatment of ODV (860 ng/larva) with different concentrations of Bmlipase-1. Data shown are means ± standard deviations of results from five experiments. Luciferase activity was measured at 136 hpi. Detailed experimental conditions are described in the legend to Fig. 1. Note that luciferase activity of hemolymph samples from nontreated B. mori larvae was also measured to determine the background level, and the level of relative light units (RLU) per 10 μl of hemolymph was 120 ± 3.4.

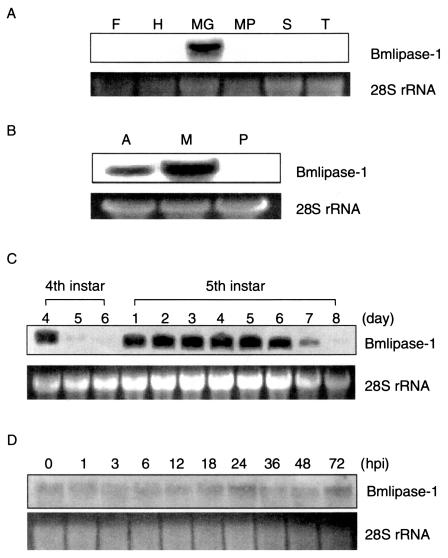

Gene expression of Bmlipase-1 was analyzed by Northern blotting. The Bmlipase-1 gene was expressed in the midgut but not in other tissues such as the fat body, hemocyte, Malpighian tubule, silk gland, and trachea (Fig. 5A). The midgut was further separated into three portions, and Bmlipase-1 gene expression was examined. The Bmlipase-1 gene was expressed in the anterior and middle portions but not in the posterior portion of the midgut (Fig. 5B). The Lip-1 gene, a D. melanogaster lipase gene, was demonstrated to be expressed at the foregut-midgut boundary in embryos by whole-mount in situ hybridization (10). Bmlipase-1 gene expression in fourth- and fifth-instar larvae was analyzed. The results showed that gene expression strongly declines at the molting stage between the fourth and fifth instars and at the wandering stage just before pupation (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the Bmlipase-1 gene is hormonally regulated. It is natural to consider that Bmlipase-1 is not necessary at the molting and wandering stages, because B. mori larvae do not ingest food during these stages. Thus, the probability of viral infection at these stages is very low. The relationship between Bmlipase-1 gene expression and BmNPV infection was examined, and viral infection was found not to activate the Bmlipase-1 gene (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of Bmlipase-1 gene expression. (A) Bmlipase-1 gene expression in the fat body (F), hemocyte (H), midgut (MG), Malpighian tubule (MP), silk gland (S), and trachea (T). As an internal marker, 28S rRNA is shown in the lower panel. Tissues such as the midgut, hemocyte, silk gland, trachea, fat body, and Malpighian tubule were prepared from two fifth-instar larvae. The midgut was further separated into anterior, middle, and posterior portions. Total RNA from each tissue was isolated with ISOGEN (Nippon Gene). Northern blotting (11) was conducted with 20 μg of RNA and screened with a digoxygenin-labeled Bmlipase-1 probe prepared by PCR DIG labeling mix (Roche). (B) Bmlipase-1 gene expression in the anterior (A), middle (M), and posterior (P) portions of the midgut. (C) Bmlipase-1 gene expression in fourth and fifth instars. Fourth-instar days 5 and 6 are the molting stage. Fifth-instar day 8 is the wandering stage. (D) Effects of BmNPV infection on Bmlipase-1 gene expression. Bmlipase-1 gene expression was analyzed at different time intervals after BmNPV infection.

In this study, we identified a protein having strong antiviral activity against BmNPV from B. mori larvae. The insect immune system response against NPV can be divided into two phases: primary defense against ODV in the alimentary canal and secondary defense against BV in other tissues such as the fat body, trachea, and hemocyte. Concerning the secondary defense stage, it has been shown that apoptosis is initiated during baculovirus replication in insect cells and that specific viral gene products, P35 and P49, are responsible for blocking the apoptotic response (5, 17). Moreover, it has been reported that cells of Helicoverpa zea larvae infected with Autographa californica M NPV are encapsulated by hemocytes and subsequently cleared, demonstrating that the insect cellular immune response is effective against viral pathogens (16). Although apoptosis and cellular immune responses have been shown to play an important role in the secondary defense stage against BV infection, the primary defense stage against ODV remains totally obscure. As far as we know, our results regarding Bmlipase-1 are the first demonstration that a protein from the digestive juice of the insect alimentary canal can be effective against viral pathogens.

Bmlipase-1 gene regulation is unique. Gene expression of this enzyme is not upregulated by viral infection but seems to be hormonally regulated, suggesting that the main role of the enzyme is food digestion. However, Bmlipase-1 is also involved in primary defense against viral infection to protect B. mori midgut epithelial cells from ODV at the initial infection stage. The antiviral mechanisms of Bmlipase-1 which suppress BmNPV replication remain unclear. A. californica M NPV protein P74 is associated with the ODV envelope. P74 is essential for oral infection with ODV and has been proposed to play a role in midgut attachment and/or fusion (12). It will be interesting to determine if Bmlipase-1 destroys the virion envelope and, as a result, prevents viral attachment to the midgut through a P74 homolog. It remains to be clarified whether Bmlipase-1 inhibits multiplication of other viruses such as cytoplasmic polyhedrosis and densonucleosis viruses that are also pathogenic for B. mori. More proteins are likely involved in primary defense, and understanding the insect immune mechanisms against viral pathogens is important for both the silk industry and general agricultural pest control.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The nucleotide sequence of Bmlipase-1 has been deposited with the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank Data Libraries under accession number AB076385.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toru Arakawa and Yoji Furuta for their helpful suggestions.

This work was supported in part by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences of the Bio-Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution in Japan and by Grants-in-Aid (Bio Design Program and Insect Technology Program) from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. D. A. 2000. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287:2185-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arreguin-Espinosa, R., B. Arreguin, and C. González. 2000. Purification and properties of a lipase from Cephaloleia presignis (Coleoptera, chrysomelidae). Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 31:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett, J. W., A. J. Brownwright, M. J. Primavera, A. Retnakaran, and S. R. Palli. 1998. Concomitant primary infection of the midgut epithelial cells and the hemocytes of Trichoplusia ni by Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus. Tissue Cell 30:602-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boman, H. G., and D. Hultmark. 1987. Cell-free immunity in insects. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41:103-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clem, R. J., M. Fechheimer, and L. K. Miller. 1991. Prevention of apoptosis by a baculovirus gene during infection of insect cells. Science 254:1388-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirata, K., H. L. Dichek, J. A. Cioffi, S. Y. Choi, N. J. Leeper, and L. Quintana. 2000. Cloning of a unique lipase from endothelial cells extends the lipase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14170-14175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann, J. A., F. C. Kafatos, C. A. Janeway, and R. A. Ezekowitz. 1999. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 284:1313-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khush, R. S., and B. Lemaitre. 2000. Genes that fight infection: what the Drosophila genome says about animal immunity. Trends Genet. 16:442-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda, S. 1989. Expression of foreign genes in insects using baculovirus vectors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 34:351-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pistillo, D., A. Manzi, A. Tino, P. Pilo Boyl, F. Graziani, and C. Malva. 1998. The Drosophila melanogaster lipase homologs: a gene family with tissue and developmental specific expression. J. Mol. Biol. 276:877-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 12.Slack, J. M., E. M. Dougherty, and S. D. Lawrence. 2001. A study of the Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus ODV envelope protein p74 using a GFP tag. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2279-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stöven, S., I. Ando, L. Kadalayil, Y. Engström, and D. Hultmark. 2000. Activation of the Drosophila NF-κB factor relish by rapid endoproteolytic cleavage. EMBO J. 1:347-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Summers, M. D., and G. E. Smith. 1978. Baculovirus structural polypeptides. Virology 84:390-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomita, S., T. Kanaya, J. Kobayashi, and S. Imanishi. 1995. Isolation of p10 gene from Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus and study of its promoter activity in recombinant baculovirus vector system. Cytotechnology 17:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washburn, J. O., B. A. Kirkpatrick, and L. E. Volkman. 1996. Insect protection against viruses. Nature 383:767. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoog, S. J., J. J. Schiller, J. A. Wetter, N. Chejanovsky, and P. D. Friesen. 2002. Baculovirus apoptotic suppressor P49 is a substrate inhibitor of initiator caspases resistant to P35 in vivo. EMBO J. 21:5130-5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]