Abstract

A growing class of proteins in biological processes has been found to be unfolded on isolation under normal solution conditions. We have used NMR spectroscopy to characterize the structural and dynamic properties of the unfolded and partially folded states of a 52-residue alanine-rich protein (Ala-14) at temperatures from −5°C to 40°C. At 40°C, alanine residues in Ala-14 adopt φ and ψ angles, consistent with a significant ensemble population of polyproline II conformation. Analysis of relaxation rates in the protein reveals that a series of residues, Gln 35–Ala 36–Ala 37–Lys 38–Asp 39–Asp 40–Ala 41–Ala 42, displays slow motional dynamics at both −5°C and 40°C. Temperature-dependent chemical shift changes indicate that this region is the site of helix initiation. The remaining N-terminal residues become increasingly dynamic as they extend from the nucleation site. The C terminus remains dynamic and changes less with temperature, indicating it is relatively unstructured. Ala-14 provides a high-resolution portrait of the unfolded state and the process of helix nucleation and propagation in the absence of tertiary contacts, information that bears on early events in protein folding.

Keywords: unstructured proteins, helix formation, protein folding, protein structure, NMR

Up to 40% of residues in globular proteins have dihedral angles within the α-helix region, making this the most prevalent secondary structural element in proteins (Hovmöller et al. 2002). The factors that determine α-helix structure have been intensively investigated experimentally and theoretically, and several algorithms have been developed that attempt to predict the helical structure present in a given sequence under specified conditions of solvent and temperature (Baldwin 1995; Munoz and Serrano 1995b; Rohl and Baldwin 1998). Despite these efforts, there remain important unresolved questions concerning the transition state, stability, and dynamics of helix formation in nascent folding proteins as well as model peptides (Sosnick et al. 1996; Eaton et al. 1997; Myers and Oas 1999). One issue concerns the extent to which alternative structures, including 3/10 or pi helices, contribute to helix formation (Daggett and Levitt 1992). A second concerns the conformational manifold of the unfolded state itself (Wright and Dyson 1999; Shortle and Ackerman 2001). Unfolded proteins have been asserted to contain significant amounts of polyproline II structure in addition to residual α or β structure (Shi et al. 2002). A third centers on the role of local side chain–side chain and side chain–main chain interactions in controlling the nucleation and localization of helix structure within a sequence (Munoz and Serrano 1995b; Aurora and Rose 1998).

Most information concerning isolated α-helix formation (as opposed to α-helical assemblies such as helical bundles and coiled coils) has emerged from analysis of peptide models, starting with Baldwin’s classic series of Ala-rich peptides (Baldwin 1995) and extending by now to a large set of model sequences. Early work on simple short peptide fragments attempted to assess the roles of helix nucleation, propagation, capping, and side chain–side chain interactions, and effects of charges and dipoles on helix formation (Kallenbach et al. 1996). Many helices in proteins are amphipathic, allowing strong interactions among their nonpolar segments with polar interactions at the surface. This has been demonstrated for a family of coiled-coil proteins, in which bulky hydrophobic side chains at positions a and d of a heptad repeat form specific interfacial interactions (“knobs-into-holes”) between helices (Lupas 1997). Because helix formation is a complex interplay among different interactions, quantitatively evaluating the contribution of the participating forces has proven challenging, and no entirely satisfactory predictive scheme for α-helix formation is now available. In part this is because the diversity of interactions among side chains and backbone groups is large (Doig and Baldwin 1995; Munoz 2001): long side chains in principle can interact with vicinal side chains up to eight residues away, making the library of needed pair-wise interactions extensive. Moreover, there remain issues concerning the additivity of free energy effects for pairs of side chains that lie within interaction range. There is then a need to analyze the process of helix nucleation and propagation at the highest possible resolution, in order to improve helix prediction for folding algorithms as well as to understand the process of nascent helix formation in protein folding.

Here we investigate the structural properties of the 52-residue polypeptide Ala-14 in solution using a series of isotope-edited NMR experiments to monitor dynamics and conformational preferences of individual side chains. We demonstrate that the alanine residues in Ala-14 favor a polyproline II (PII) conformation at 40°C, showing that length and heterogeneity in sequence do not inhibit the propensity of alanine for assuming PII structure. Other residues can also be seen to have PII conformation, in most cases to a lesser extent than alanine. We identify a helix nucleation site located between residues 37 and 42 in Ala-14; these residues have H-bonded amides and lower mobility at low and high temperatures. Local side chain–side chain interactions determine the location of this site rather than the alanine content per se. As temperature is lowered, propagation from this site is detected extending preferentially toward the N terminus of the molecule. These results present a detailed portrait of the structure of this nascent folding process in a unimolecular chain: the disordered structure is limited to subsets of the Ramachandran space in the case of the Ala residues, and helix propagation occurs from the C-terminal third of the protein and proceeds most clearly toward the N terminus in the absence of tertiary contacts.

Results

Ala-14

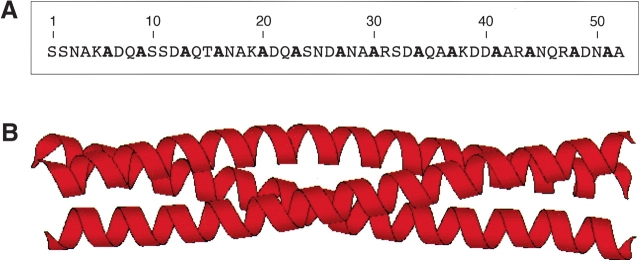

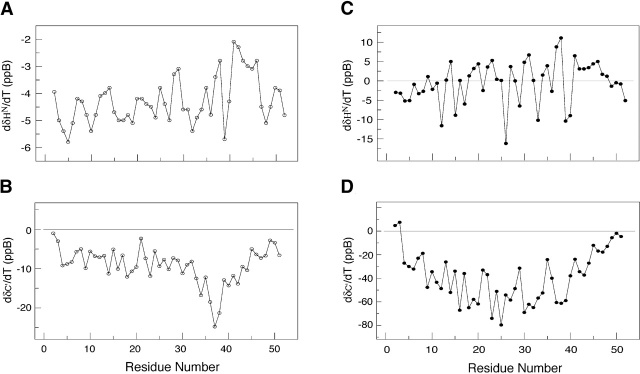

Ala-14 is a 52-residue recombinant protein that contains alanine residues at all the hydrophobic a and d positions of the heptad-repeat sequence of the Escherichia coli outer membrane lipoprotein (Fig. 1A ▶; Shu et al. 2000; Liu and Lu 2002). Previous studies have shown that Ala-14 is largely unfolded under normal solution conditions, although it can form a well-defined trimeric alanine zipper in the crystalline state (Fig. 1B ▶; Liu and Lu 2002). A network of long-range intermolecular interactions observed in the crystal structure of Ala-14 is thought to control its folding into an α-helical trimer structure (Liu and Lu 2002). On the other hand, Ala-14 is monomeric in solution even at high protein concentrations (Fig. 2A ▶). On the basis of CD measurements at 0°C, Ala-14 contains ~20% α-helical structure (Fig. 2B ▶). CD spectra of Ala-14 in the presence of increasing concentrations of the chemical denaturant GdmCl show a weak positive band at ~220 nm (Fig. 2B ▶). This type of spectrum has been observed in unfolded polypeptides (Tiffany and Krimm 1968; Rippon and Walton 1971; Drake et al. 1988; Woody 1992; Park et al. 1997) and has been assigned to the polyproline II helical structure (Woody 1992; Sreerama and Woody 1994; Bhatnagar and Gough 1996; Shi et al. 2002). Ala-14 offers an ideal model in which to investigate the structure, folding, and dynamics of isolated helix formation in a polypeptide chain of 52 amino acids, substantially larger than most model peptides.

Figure 1.

Ala-14 forms a parallel triple-stranded α-helical coiled coil in crystals. (A) Sequence of Ala-14. The alanine residues that occupy the A and D positions comprising the core of the alanine-zipper trimer interface are shown in bold. (B) A side view of the crystal structure of the Ala-14 trimer (residues 3–50).

Figure 2.

Ala-14 is largely unfolded in solution. (A) Representative sedimentation equilibrium data (34 krpm) of Ala-14 collected at 4°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.8) in ~6 mg mL−1 protein concentration. The natural logarithm of the absorbance at 232 nm is plotted against the square of the radial position. Lines indicate the expected slopes for monomeric, dimeric, and trimeric states. The random distribution of residuals indicates that the data fit well to an ideal single-species model. (B) Circular dichroism spectra of a 10 mg mL−1 solution of Ala-14 in PBS (pH 7.0) and 0°C as a function of GdmCl concentration.

Heteronuclear assignments

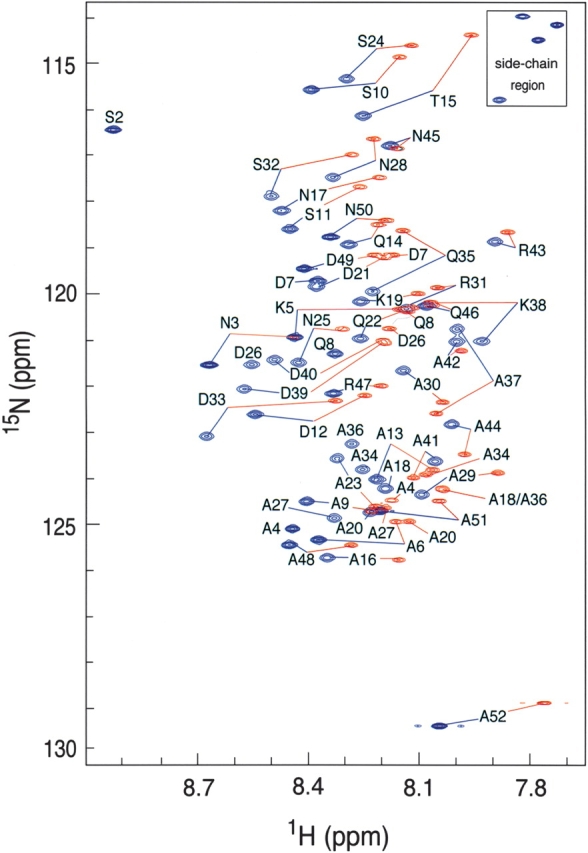

In order to evaluate the conformational properties of Ala-14, we produced singly (15N) and doubly (15N/13C) labeled Ala-14 and performed a series of NMR experiments for assigning the backbone resonances of the protein to their respective locations within the protein sequence. The monomeric state of Ala-14 in our samples was confirmed using sedimentation equilibrium analysis at concentrations of 1.2 mM to 3.6 mM. The 1H–15N HSQC spectra of Ala-14 at 40°C and −5°C are shown in Figure 3 ▶. At 40°C, the spectra display sharp peaks and a pronounced lack of chemical shift dispersion consistent with a predominantly disordered conformation. Reduction in temperature to −5°C improved resolution in the 1HN chemical shifts. The standard deviations of all 1HN chemical shifts are 0.12 (40°C), 0.16 (15°C), and 0.20 (−5°C); they markedly increase with lowered temperature. The 15N chemical shifts display a slight reduction in resonance dispersion, with standard deviations of 3.21 (40°C), 3.16 (15°C), and 2.99 (−5°C). The 2D HSQC spectra of Ala-14 at different protein concentrations (100 μM, 500 μM, and 1 mM) at −5°C showed no detectable changes in either the chemical shifts or relative peak intensities, indicating no weak association under NMR conditions. Thus, the spectral changes of Ala-14 between 40°C and −5°C represent conformational changes within the isolated monomer.

Figure 3.

Superposition of the 600-MHz proton-nitrogen correlation (HSQC) spectra of Ala-14 in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.8) at −5°C (blue) and 40°C (red). Residue-specific assignments of the backbone 1H and 15N frequencies are indicated except Ser 1 in the −5°C spectrum and Ser 1, Ser 2 in the 40°C spectrum.

The heteronuclear backbone assignments of Ala-14 were obtained for residues Ser 2 through Ala 52 using the triple resonance experiments (HNCO [Kay et al. 1994], HNCACB [Wittekind and Mueller 1993], HNCA [Farmer et al. 1992], and HCACO [Grzesiek and Bax 1993]) to establish nearest-neighbor connectivities. Resonances of the 20 Ala residues and several repeated stretches of the Ala-14 sequence at −5°C overlapped. To shift the various overlapping peaks, we collected the HNCA and HNCO spectra of Ala-14 at 15°C. Heteronuclear assignments were extended to other temperatures for 1HN, 15N, 13C′, and 13Cα chemical shifts. The 1HN(i)–15N(i) chemical shifts were transferred to higher temperatures using 2D 1H–15N HSQC. Two-dimensional H(N)CA and H(N)CO spectra, omitting the nitrogen-evolution period, were used to obtain 2D 1HN(i)–13Cα(i) and 2D 1HN(i)–13C′(i-1) correlations, respectively, at additional temperatures. The chemical shift assignments transferred by temperature titration were verified by collection of 3D HNCA, HNCACB, HNCO, and HCACO spectra at 40°C. The assignments were checked by collection of the 1H–15N HSQC-NOESY-HSQC (Zhang et al. 1997) at −5°C for identification of the 1HN(i)–1HN(i + 1) NOEs. The sequential NOE cross-peaks were observed in a continuous stretch from residues 2 through 51 at −5°C. The backbone chemical shift assignments for Ala-14 at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C are given in Electronic Supplemental Material.

Chemical shifts

The deviation of chemical shifts from their random-coil values (Δδ = δobs − δcoil) is dependent on the φ, ψ backbone torsion angles and the local chemical environment, and therefore provides a highly sensitive indicator of secondary structural propensities (Wishart et al. 1991). Given the fact that the chemical shifts of both native and nonnative proteins are temperature dependent (Shalongo et al. 1994), the temperature dependence of the random-coil chemical shifts (δcoil) is necessary to allow meaningful comparison of Δδ values at different temperatures. The values of Δδ were corrected for the temperature-dependent chemical shifts for each atom as shown

|

(1) |

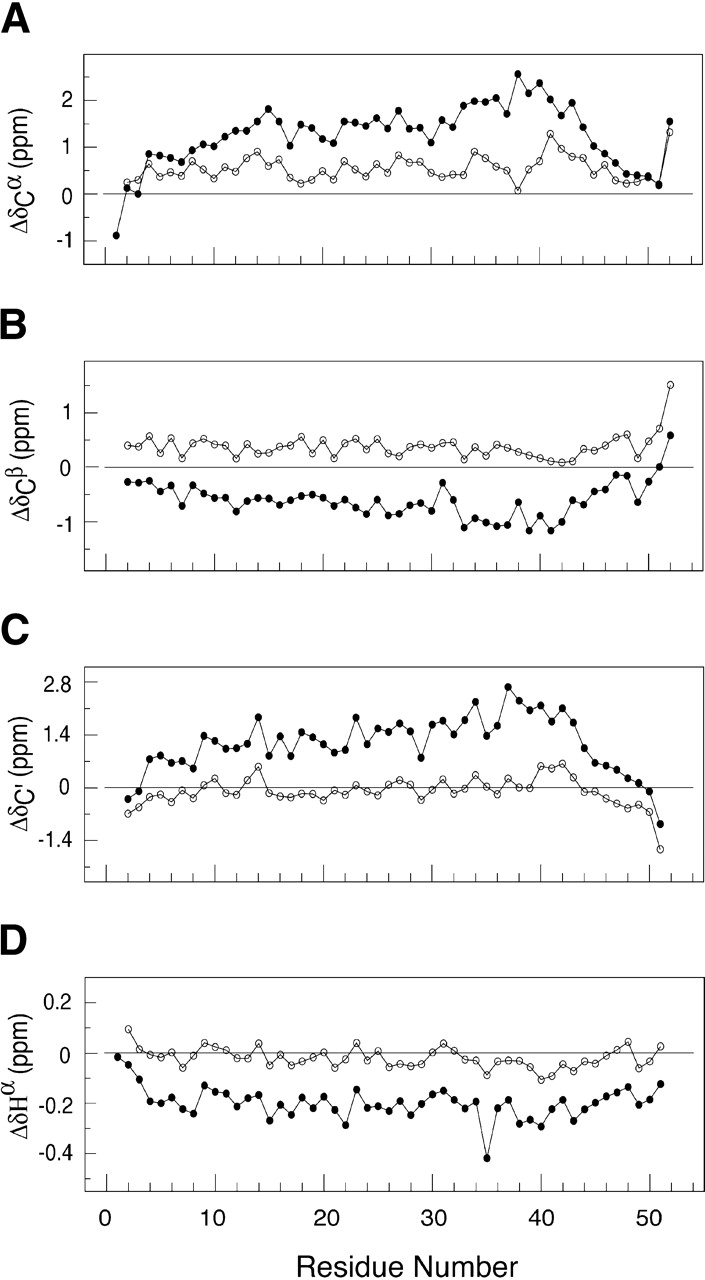

where δcoil is the reference value for the amino-acid-specific random-coil chemical shift given at T = 25°C, and Δδcoil/ΔT is the temperature-dependent correction factor for the random-coil chemical shifts of a particular nuclei. Estimates of Δδcoil/ΔT were measured using chemical shift data collected on Ala 14 at 30°C, 35°C, and 40°C. The 15% trimmed mean of Δδcoil/ΔT was used to exclude outliners, and the values of Δδcoil/ΔT obtained were ΔδHN/ΔT = −4.3 ± 0.7, ΔδHα/ΔT = 1.6 ± 0.6, ΔδN/ΔT = −5.3 ± 0.9, ΔδC′/ΔT = −8.2 ± 2.9, ΔδCα/ΔT = 1.4 ± 5.8, and ΔδCβ/ΔT = 8.3 ± 3.8 ppb/K. The values measured are slightly smaller in amplitude than previously measured values of the so-called random-coil temperature-dependent shifts observed in other peptides and proteins (Shalongo et al. 1994). Corrected values of Δδ are presented for the 1Hα, 1HN, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, and 15N nuclei in Figure 4 ▶. At 40°C, the chemical shifts display only marginal variation from random-coil values. This is consistent with a predominantly unstructured sequence with ΔδCα showing a slight bias toward helix and ΔδCβ toward β-structure whereas the ΔδC′ and ΔδHα shifts show no structural preference. On cooling to −5°C, positive values are observed for ΔδC′ and ΔδCα with averages of 1.17 ± 0.73 and 1.27 ± 0.65 ppm, respectively, and negative values of both ΔδHα and ΔδCβ with averages of −0.20 ± 0.06 and −0.60 ± 0.32 ppm, respectively. The direction of the chemical shifts is consistent with a preference for α-helical conformation from residues Lys 5 through Asn 45, with the largest shifts toward helical values observed for residues Asp 33 through Arg 43 at −5°C. The amide ΔδHN values are strongly dependent on hydrogen-bond length, which results in a 3.6 per residue periodicity in the ΔδHN values in coiled-coil sequences (Kuntz et al. 1991; Zhou et al. 1992; Bracken et al. 1999). No periodicity is observed in the ΔδHN values of Ala-14 at −5°C, indicating an absence of helical curvature as seen in stable coiled coils (Blanco et al. 1992; Zhou et al. 1992).

Figure 4.

Chemical shift deviations from random-coil values for 13Cα (A), 13Cβ (B), 13C′ (C), and 1Hα (DA) resonances of Ala 14 in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.8) at −5°C (solid circles) and 40°C (open circles). The positive values of 13Cα and 13C′ and negative values of 1Hα are indicators of α-helical structure.

The chemical shift data were analyzed using the program TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999). The program uses a database of chemical shifts to empirically estimate the φ, ψ angles based on the chemical shifts of residues i and neighboring residues i − 1 and i + 1. The program is designed for prediction of φ, ψ backbone torsion angles in native proteins. Here it serves as a useful gauge of the extent and ensemble preferences of partially folded structure within Ala-14. At −5°C, 17 residues (25 residues contain eight or more structural matches) within the sequence are assigned to α-helical secondary structure by TALOS predictions. These residues are 2, 3, 23, 27, 28, 30, and 33–43, with the most strongly α-helical region extending from Gln 22 to Asn 45. Extended structure is observed at the chain termini. At 15°C, the number of residues predicted falls off sharply. Only three residues, Ala 41, Ala 42, and Arg 43, are predicted to adopt α-helical conformation. Weaker indications of helix are observed at adjacent residues Ala 34 to Asp 40 and Ala 44. At 40°C, a number of φ, ψ angles are predicted to fall in the PII conformational space (Table 1; residues 3, 5, 17,19, 26, 33, 50, and 51). Residues 41–43 are the sole residues that indicate a weak preference for α-helical conformation, and all other residues are predicted to occupy extended conformations in Ramachandran space with average predicted angles of φ = −83°C and ψ=138°C.

Table 1.

Structural parameters of Ala 14 at 40°C

| NMR measurements | TALOS predictionsa | ||||

| Residue | 3JHNHα (Hz) | φ | φ | ψ | NMR measurements IHβiNi/IHβiNi+1 |

| Ser 2 | |||||

| Asn 3 | −78 ± 16 | 140 ± 21 | |||

| Ala 4 | −85 ± 17 | 136 ± 18 | |||

| Lys 5 | −82 ± 13 | 135 ± 20 | |||

| Ala 6 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | −75 | −83 ± 15 | 140 ± 17 | |

| Asp 7 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | −82 | −81 ± 17 | 134 ± 21 | |

| Gln 8 | −82 ± 19 | 137 ± 20 | |||

| Ala 9 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | −75 | −86 ± 15 | 136 ± 19 | |

| Ser 10 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | −81 | −79 ± 15 | 142 ± 16 | |

| Ser 11 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | −81 | −85 ± 20 | 135 ± 19 | |

| Asp 12 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | −81 | −77 ± 17 | 139 ± 18 | |

| Ala 13 | −87 ± 22 | 135 ± 16 | |||

| Gln 14 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | −83 | −86 ± 12 | 144 ± 17 | |

| Thr 15 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | −86 | −91 ± 17 | 129 ± 16 | |

| Ala 16 | 5.9 ± 0.4 | −73 | −74 ± 16 | 144 ± 16 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| Asn 17 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | −85 | −79 ± 17 | 139 ± 22 | |

| Ala 18 | −90 ± 21 | 134 ± 20 | |||

| Lys 19 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | −84 | −82 ± 13 | 135 ± 20 | |

| Ala 20 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | −75 | −83 ± 15 | 140 ± 17 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Asp 21 | −83 ± 14 | 136 ± 22 | |||

| Gln 22 | −85 ± 18 | 139 ± 19 | |||

| Ala 23 | −86 ± 15 | 136 ± 19 | |||

| Ser 24 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | −81 | −82 ± 15 | 138 ± 15 | |

| Asn 25 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | −85 | −77 ± 18 | 139 ± 18 | |

| Asp 26 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | −79 | −81 ± 15 | 140 ± 17 | |

| Ala 27 | |||||

| Asn 28 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | −86 | −79 ± 17 | 146 ± 12 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Ala 29 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | −74 | |||

| Ala 30 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | −75 | −84 ± 15 | 137 ± 20 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Arg 31 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | −83 | −86 ± 16 | 146 ± 10 | |

| Ser 32 | 6.9 ± 0.2 | −80 | −87 ± 16 | 132 ± 16 | |

| Asp 33 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | −82 | −78 ± 16 | 140 ± 17 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| Ala 34 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | −72 | −78 ± 20 | 134 ± 16 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| Gln 35 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | −82 | −81 ± 16 | 145 ± 10 | |

| Ala 36 | −81 ± 16 | 138 ± 16 | |||

| Ala 37 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | −73 | −74 ± 16 | 136 ± 17 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| Lys 38 | −79 ± 18 | 137 ± 14 | |||

| Asp 39 | −76 ± 17 | 134 ± 14 | |||

| Asp 40 | −75 ± 16 | 137 ± 13 | |||

| Ala 41 | −84 ± 16 | −13 ± 11 | |||

| Ala 42 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | −73 | −77 ± 14 | −22 ± 18 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| Arg 43 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | −82 | −90 ± 16 | −7 ± 17 | |

| Ala 44 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | −72 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | ||

| Asn 45 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | −85 | −80 ± 17 | 139 ± 17 | |

| Gln 46 | |||||

| Arg 47 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | −83 | −84 ± 14 | 137 ± 18 | |

| Ala 48 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | −77 | −85 ± 15 | 143 ± 17 | |

| Asp 49 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | −82 | −90 ± 23 | 131 ± 27 | |

| Asn 50 | −84 ± 17 | 136 ± 18 | |||

| Ala 51 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | −77 | −95 ± 27 | 125 ± 21 | |

| Ala 52 | 7.3 ± 0.9 | −83 | |||

a TALOS predictions with five or more chemical shift matches to the database of structures are shown, and those with eight or more matches are indicated in bold.

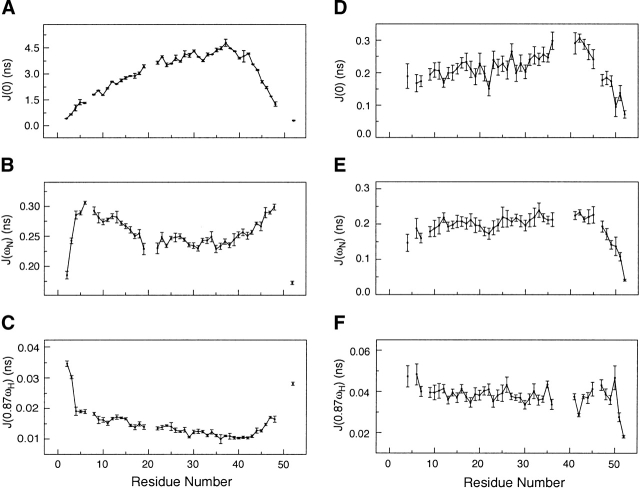

Figure 5 ▶ illustrates the temperature dependence of the 13C′ (ΔδC′/ΔT) and 1HN (ΔδHN/ΔT) resonances, obtained by linear fits to data from low temperatures (−10°C, −5°C, and 0°C) as well as high temperatures (30°C, 35°C, and 40°C). The values of ΔδC′/ΔT from 30°C to 40°C are small, ~−8 ppb/K. Low values of ΔδC′/ΔT have been observed in both random-coil and fully structured residues. Larger deviations are generally attributable to population shifts between distinct chemical environments, folded and unfolded conformations; for example, Ala 37 and Lys 38 display ΔδC′/ΔT <−20 ppb/K (Fig. 5B ▶). The direction of change in the ΔδC′/ΔT values for these residues is consistent with the formation of helical conformation. At low temperatures, the majority of the residues from Ala 4 to Ala 44 display ΔδC′/ΔT values <−20 ppb/K. The direction of ΔδC′/ΔT is consistent with the idea that a conformational shift toward a more helical population occurs as the temperature is lowered.

Figure 5.

Temperature-dependent chemical shift deviations for the 13C′ and 1HN resonances of Ala-14 at −5°C (A, B) and 40°C (C, D). Both folded and unfolded structures display small temperature-dependent changes in the carbonyl chemical shifts (~0–15 ppb; panels B and D) and in the amide resonances (−2 to −7 ppb; panels A and C). Residues that undergo conformational transitions between distinct chemical environments typically display greater variability in the temperature-dependent shifts. Large negative values for 13C′ resonances (<−20 ppb) indicate a transition toward helical structure.

The values of ΔδHN/ΔT at high temperature are small, −4.3 ± 0.7 ppb/K. Typically, ΔδHN/ΔT values of −6 ppb/K are seen in random-coil sequences, whereas values around −2 ppb/K are observed in hydrogen-bonded structures (Merutka et al. 1995; Otlewski and Cierpicki 2001). Substantially larger or smaller values are generally attributed to changes in conformational populations. Between 30°C and 40°C, the largest deviations are observed at residues 41 and 42 with values of −2.1 ± 0.3 and −2.3 ± 0.4, respectively (Fig. 5A ▶). On cooling, the ΔδHN/ΔT values measured from −10°C to 0°C (Fig. 5C ▶) deviate significantly from values obtained from either “random-coil” or hydrogen-bonded structures; they range from a minimum value of −11 ppb/K to a maximum value of +16 ppb/K. Such large variations in chemical shift temperature gradients are observed in partially folded structures (Anderson et al. 1997).

Collectively, the ΔδC′/ΔT and ΔδHN/ΔT values display maximum variations in the C′ (Ala 37, Lys 38) and HN (Ala 41, Ala 42) chemical shifts at high temperature that are consistent with initial formation of i to i + 4 α-helical hydrogen bonding in this region of the protein. Between 0°C and −10°C, the values of the temperature coefficients are larger in magnitude than expected for either fully structured or unstructured protein, indicating that the majority of the residues are actively involved in a transition toward increasing α-helical structure.

NOESY data

N15-edited NOESY spectra were recorded to verify the sequence-specific assignments and assess helical content. At −5°C, NOESY spectra recorded with a 125-msec mixing time confirm the presence of helical content with a continuous stretch of dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs between residues 2 and 51. Stable helical regions often display medium-range dNN(i,i + 3) and dNN(i,i + 4) NOEs as well; however, at −5°C, we detect no dNN NOEs beyond dNN(i,i + 1), possibly indicating a fluctuating helical structure. At 40°C, the 15N NOESY-HSQC spectra were recorded with a 300-msec mixing time. In contrast to the NOE data collected at −5°C, no dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs are present at high temperature; instead, numerous dαN and dβN NOEs are observed. The degree of overlap in the Hα, Hβ and HN regions prevents unambiguous assignment of the majority of these peaks. However, we could measure dβN(i) and dβN(i + 1) NOEs for residues Ala 16, Ala 20, Asn 28, Ala 30, Asp 33, Ala 34, Ala 37, Ala 42, and Ala 44. The intensities of the dβN(i) and dβN(i + 1) NOEs were quantitated to calculate the ratio of dβN(i)/dβN(i + 1) NOEs. These ratios vary as a function of φ and ψ values adopted, thereby providing an indication of the region of Ramachandran space occupied. For Ala-14, the dβN(i)/dβN(i + 1) ratios vary from 4 to 0.3 (see Table 1). The absence of amide–amide NOEs indicates that little or no helical content is present at 40°C.

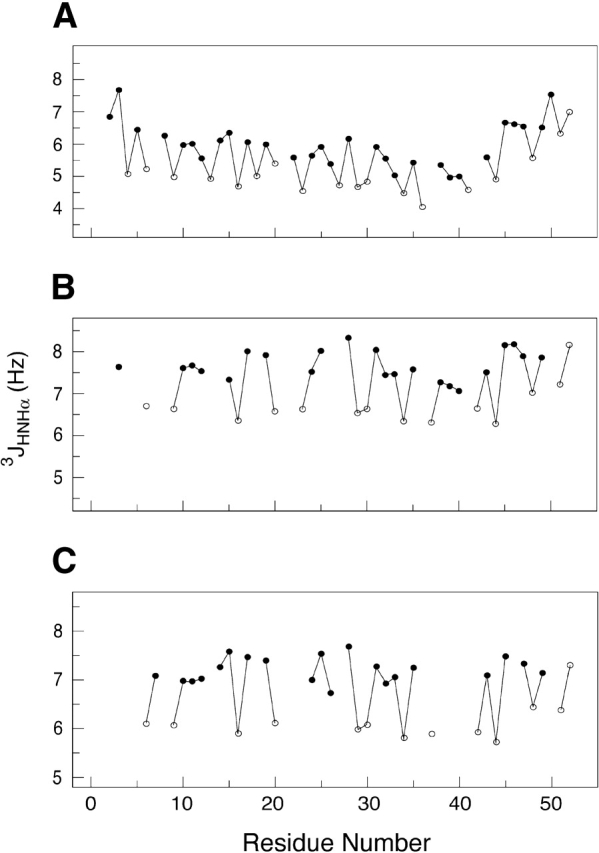

Scalar coupling constants

The 3JHNHα scalar coupling constants were measured using 2D HMQC-J experiments (Kuboniwa et al. 1994) at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C. Initial measurements of 3JHNHα display significantly lower values for all of the alanines. HMQC-J experiments were verified using 15N-labeled ubiquitin, and the resulting 3JHNHα values were in excellent agreement with published values (Wang and Bax 1996). To increase the accuracy of the HMQC-J experiments, we directly measured the T1α proton relaxation rates using a 13C/15N-labeled Ala-14 sample dissolved in 100% D2O. The pulse sequence used was a modified version of the HCACO experiment, incorporating a selective 1Hα longitudinal relaxation period prior to the HCACO transfer sequence. At −5°C, the average T1α relaxation times for the Ala residues have slightly lower values (T1αAla = 0.59 ± 0.03 sec) compared with all other residues (T1αOther = 0.68 ± 0.02 sec). These trends diminished at 15°C (T1αAla = 0.56 ± 0.03 sec; T1αOther = 0.55 ± 0.02 sec) and at 40°C (T1αAla = 0.50 ± 0.01 sec; T1αOther = 0.47 ± 0.03 sec). The coupling constants for the majority of residues were obtained at −5°C, those of Asp 21, Ala 37, and Ala 42 excepted because of overlap; at 15°C, residues 4, 5, 7, 8, 13, 14, 18, 21, 22, 36, 41, and 50 could not be monitored. At 40°C, substantial peak degeneracy obscured residues 3, 4, 5, 8, 13, 21, 22, 23, 27, 36, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46, and 50. At all temperatures, 3JHNHα values of Ala residues are about 1 Hz lower than all nonalanine residues, consistent with the lower average values of Ala residues seen in “random-coil” models (Smith et al. 1996; Plaxco et al. 1997). At −5°C, the average 3JHNHα values of the alanine (excluding Ala 51, Ala 52) and nonalanine resonances are 5.0 ± 0.3 Hz and 5.9 ± 0.5 Hz, respectively (Fig. 6A ▶). Starting from the N terminus, the scalar coupling constants gradually decline in value, with the lowest values from residues Ala 29 through Ala 44 (4.9 ± 0.4 Hz). Residues 45–52 at the C terminus display significantly higher 3JHNHα values (6.6 ± 0.4 Hz). The trend in scalar couplings is consistent with the presence of increasing helical content as the temperature decreases. The 3JHNHα values acquired at 40°C range from 5.7 to 7.5 Hz, with the alanines (excluding Ala 51, Ala 52) having a mean value of 6.0 ± 0.2 Hz compared with 7.2 ± 0.3 Hz for other residues (excluding Ser 2, Asn 3). The φ angles calculated based on these coupling constants indicate an average φ = −74°C for the alanines and φ = −83°C for other residues. These values lie in a region corresponding to α helical and PII conformation.

Figure 6.

The JHNHα scalar coupling constants of Ala-14 at −5°C (A), 15°C (B), and 40°C (C). The alanine residues are shown as open circles, and all other residues are shown as solid circles. The JHNHα values observed in α helices typically range between 4.0 and 5.0 Hz.

15N relaxation analysis

15N relaxation rates were measured using a sample with 1.5 mM monomer concentration of Ala-14 at −5°C and 40°C. Values of the measured relaxation rates are given in the Electronic Supplemental Material. Some of the relaxation rates, Ser 1, for example, could not be measured because of solvent exchange of the free N terminus, whereas other residues were undetermined because of chemical shift degeneracy, including Asp 7, Ala 20, and Asp 21 at −5°C, and Lys 5, Gln 8, Ala 37, Lys 38, Asp 39, Asp 40, and Gln 46 at 40°C. The average R1, R2, and NOE relaxation rates for residues 4 to 47 are, respectively, 1.44 ± 0.11, 10.2 ± 2.5, and 0.39 ± 0.07 at −5°C; and 1.44 ± 0.08, 1.56 ± 0.13, and −0.84 ± 0.17 at 40°C.

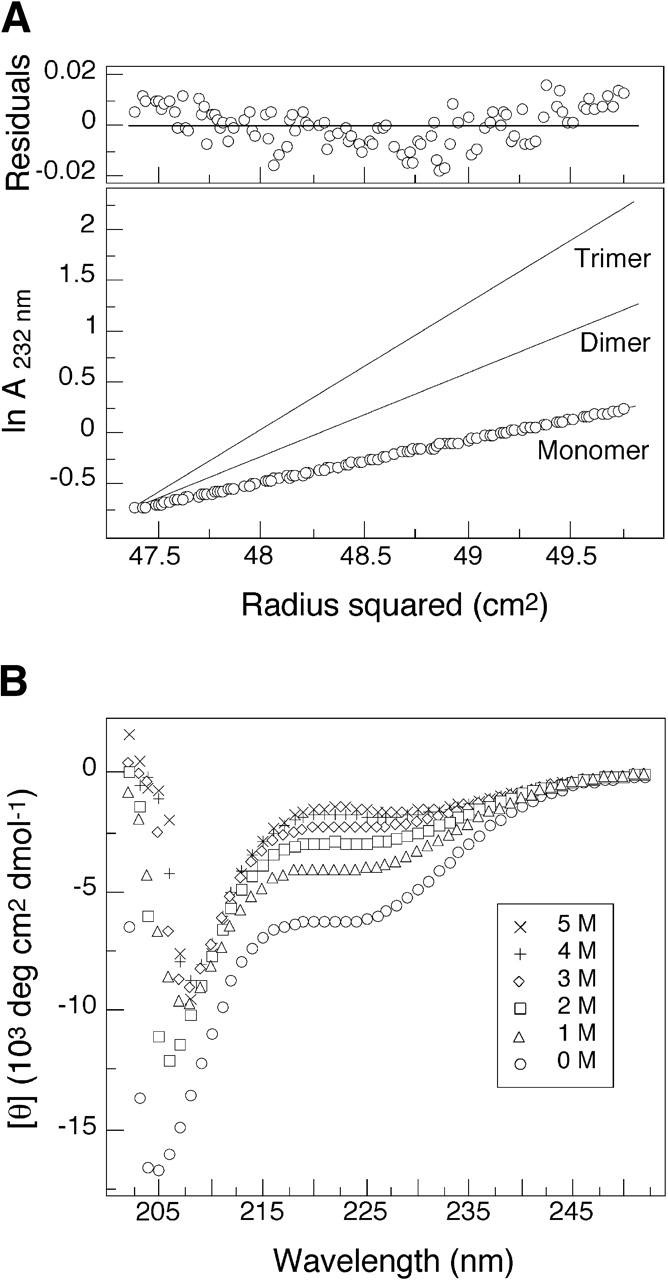

The absence of rigid structure in Ala-14 restricts the type of dynamics analysis that can be applied, due to the lack of a single overall correlation time and the complexity of internal motions. Reduced spectral density mapping provides a simple analysis that requires no model assumptions, and gives estimates of the spectral densities at J(0), J(ωN), and J(0.87ωH), which contain contributions from overall as well as local dynamics (Farrow et al. 1995a). At 40°C, the spectral density values of J(0) and J(ωN) between residues 5 and 30 reveal no particular trend, the average values of J(0) = 0.21 ± 0.02 nsec and J(ωN) = 0.20 ± 0.02 nsec (Fig. 7 ▶) indicating that fast subnanosecond motions are present. However, the J(0) values for residues 36, 41, 42, and 43 are slightly elevated compared with J(ωN), indicating slightly reduced motions in this region. In contrast, the spectral densities calculated at −5°C display substantially slower motional processes overall (Fig. 7 ▶). The maximum values of J(0) occur at residues Gln 35 to Asp 39, and the minimum values of the J(0.87ωH) occur from Gln 35 to Ala 44, indicating that this region undergoes the slowest reorientational motions in the protein. The J(0) values smoothly decrease from Ala 37 to the N terminus, and the J(0.87ωH) values show a parallel increase in this same region: this indicates a gradual transition to faster motions near the N terminus. The dynamic motions increase more sharply going from Ala 37 toward the C terminus, indicating that the C-terminal end of the protein displays greater flexibility. Data collected at both −5°C and 40°C indicate slower motions centered near Ala 37. If no structural changes occurred on cooling from 40°C to −5°C, then the J(0) values should scale with viscosity and temperature (η/T), increasing by approximately fourfold. Instead, we observe a 15-fold increase in the values of J(0) at −5°C compared with 40°C, indicating significant structure formation increasing the effective correlation time experienced by the peptide backbone.

Figure 7.

Plots of the reduced spectral densities of Ala-14. (A) J(0) at −5°C. (B) J(ωN) at −5°C. (C) J(0.87ωH) at −5°C. (D) J(0) at 40°C. (E) J(ωN) at 40°C. (F) J(0.87ωH) at 40°C. Lower values of J(0) and higher values of J(0.87ωH) indicate faster motions. The values of J(ωN) initially increase because of faster motions and then begin to rapidly decrease because of subnanosecond motions as seen in the termini of the polypeptide chain.

Discussion

In one view of how proteins fold to their native conformation, local secondary structure formation has been assumed to guide the process; this forms the basis of a hierarchical model of folding (Baldwin and Rose 1999a,b). In this model, short-range interactions lead to local regions of secondary structure that accrete cooperative structural elements as the folding reaction proceeds. Ala-14 presents an unusual opportunity to investigate the unfolded state in a chain of substantial length. The process of helix formation and propagation can be monitored in atomic detail despite lack of a fixed native folded structure. Our results show that initial helix formation in Ala-14 occurs between residues 36 and 42. Interestingly, this region is identified by the AGADIR program (Munoz and Serrano 1995a,b; Lacroix et al. 1998) as having the highest probability of helix formation in the molecule, although numerically the prediction does not match experiment. Our results also show that helical structure propagates from this helix-nucleation site toward the N terminus of the protein.

What is responsible for helix initiation at this site? Inspection of the nucleating site and its immediate vicinity in Ala-14, Ala 34–Gln 35–Ala 36–Ala 37–Lys 38–Asp 39–Asp 40–Ala 41–Ala 42–Arg 43–Ala 44–Asn 45, reveals several potential interactions that promote nascent helix formation. In terms of propensities, this sequence is 50% Ala, which is known to be helix stabilizing (Spek et al. 1999). However, there is at least one other comparably Ala-rich sequence in the protein, N terminal to this site. The presence in this site of two Asp side chains with helix-terminating capability points to a role for side chain–side chain interactions. H-bonds and/or salt bridges between side chains at positions i, i + 3, or i + 4 in helices also stabilize α-helix structure (Marqusee and Baldwin 1987; Gans et al. 1991; Lyu et al. 1992; Lavigne et al. 1996; Spek et al. 1998). Two such interactions center on the pair of Asp side chains: one between Gln 35 and Asp 39, the second between Asp 40 and Arg 43. This idea is supported by a substitution experiment based on the AGADIR program. Replacement of Asp 39 and Asp 40 by Ala side chains decreases the predicted helix content, despite the low propensity of Asp relative to Ala. Thus, without site-directed mutagenesis or testing short peptide models comprising the nucleation site, we can infer reasonably that the presumptive side chain–side chain interactions involving Asp 39 and Asp 40 have a role in nucleating α helix. In addition, helix capping has been identified as a contributor to the stability of short helical segments (Aurora and Rose 1998). Possible capping occurs at the N terminus via Ser 32 side-chain to Asn 35 main-chain interactions. Potential C-terminal capping interactions are possible by Asn through direct hydrogen-bond formation between the Asn side chain and exposed backbone amide protons (Gong et al. 1995). Asn 45 in the nucleation site of Ala-14 might thus act as a termination signal, preventing the helix from reaching the C terminus, and account for the strong preferential propagation toward the N terminus.

The presence in the GCN4 leucine-zipper dimer of a short region near the C terminus with high helical probability based on AGADIR predictions has previously been proposed to nucleate dimer folding via a collision-diffusion mechanism (Holtzer et al. 1997; Myers and Oas 1999, 2002; Zitzewitz et al. 2000). Whether or not it plays a role in nucleating trimer formation, the region in which we detect initiation of helix formation in Ala-14 is native to the parent Lpp-56 sequence (Shu et al. 2000). The region is highly conserved among gram-negative bacteria as well.

On nucleation, helix formation in Ala-14 occurs in the absence of intermolecular association, and no colligative effects were observed under all conditions used. Cooling increases the overall helical content, which builds at the site of initiation and the surrounding sequence. Motions in the ps-ns regime, probed using NMR relaxation analysis, point to the most stable region occurring at the site of helix initiation. These motions increase as one moves from the initiation site to the N terminus, and sharper changes are observed toward the C terminus. The flexible loop and terminal regions seen in folded proteins have previously been found to undergo more abrupt transitions in dynamics between ordered and disordered regions (Palmer and Bracken 1999; Bracken 2001). The striking continuity of motional change in Ala-14 indicates an ensemble of rapidly interconverting helices of varying length. The data are consistent with helix initiation occurring within residues 36–42, followed by propagation of helix toward the N terminus.

Of equal interest is the nature of the unfolded state of the protein prior to formation of helix. Ala-14 is an alanine-rich protein with 20 alanines in 52 residues. At 40°C, each Ala has a 3JHNHα coupling constant value near 6 Hz, indicative of either mixed α and β conformations or PII secondary structure. Recent evidence from short Ala-containing model peptides supports the latter interpretation. In these model peptide studies, no detectable short-range dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs are observed, despite the presence of numerous dαN and dβN contacts. This is distinct from NOE spectra observed in the majority of unfolded state proteins that typically display dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs, used for obtaining sequential assignments (Dyson and Wright 1991). The absence of dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs has been noted in the unfolded state apo-plastocyanin, which adopts extended conformations under nondenaturing conditions (Bai et al. 2001). This lack of NOEs excludes the presence of a significant population of α-helical structure, and the observed coupling constants for a predominantly β and PII conformation would yield much higher 3JHNHα values than observed (Shi 2002; Shi et al. 2002). Ala-14 exhibits similar behavior: lack of short-range dNN(i,i + 1) NOEs indicating low helix content and coupling constants too low to accommodate β conformation in the absence of helix. In addition, the chemical-shift-based φ–ψ estimation using TALOS indicates that PII conformation is the dominant secondary structure present at 40°C.

For the Ala side chains that predominate in Ala-14, the picture we obtain indicates conversion from a predominantly PII conformational manifold to one that progressively switches to α helix at low temperature values. This is consistent with recent studies on short Ala peptides (Shi 2002). Finding similar behavior in Ala-14 greatly extends these findings: first, Ala-14 is much longer and second, it is heterogeneous in sequence. Significant occupancy of PII conformation in peptides with less alanine content has also been reported (Shi 2002). This means that the transition from unfolded chain to helix with extensive H-bond formation between internal NH and CO groups requires desolvation of the extended backbone postulated to be present in the PII conformation (Sreerama and Woody 1999; Shi et al. 2002). It seems likely that the transition state between α helix and unfolded conformations entails solvent reorganization that finally releases water molecules close to the backbone and allows intramolecular H-bond formation (Garcia and Sanbonmatsu 2001).

A curious observation with respect to Ala-14 in solution is that NMR samples of the protein do not freeze at surprisingly low temperatures. Samples are stable in solution at −10°C for several days. In our case, perhaps the protein itself may be acting as a cryoprotectant, as in the case of antifreeze peptides found in teleost fish (Davies and Sykes 1997). Although there are diverse strategies to prevent crystallization of ice by peptides that act noncolligatively and bind ice, one class of these proteins consists of short α-helical peptides that are rich in Ala and contain, in addition, evenly spaced Thr or Ser side chains (Davies and Sykes 1997; Zhang and Laursen 1999; Kuiper et al. 2002). The optimum periodicity appears to be at sites 11 residues from each other; in Ala-14, no such regularity is seen. However, a sequence of Ser and Thr side chains spaced either 10, 12, or 13 residues apart occurs that might suffice to offer some partial cryoprotection in combination with the high concentration of the samples. However, natural antifreeze peptides seem to confer more modest protection than what we observe: for example, 40 mg mL−1 of the natural peptides reduce the freezing temperature by <2°C (Davies and Sykes 1997). Thus, some degree of supercooling may occur in the NMR tubes (Skalicky and Szyperski 2000).

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The uniformly 15N- and doubly 13C/15N-labeled Ala-14 protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS in M9 minimal media at 20°C using a previously published protocol (Marley and Bracken 2001; Liu and Lu 2002). The Ala-14 protein was purified from the soluble fraction to homogeneity by reverse-phase HPLC as described previously (Lu et al. 1999). Samples for NMR experiments were prepared by dissolving lyophilized protein in the sample buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 5.8, 0.05% sodium azide in 90% H2O/10% D2O) and dialyzing overnight against the sample buffer. Protein concentrations were approximately 6 mg mL−1. For experiments using 100% D2O, the buffered 13C/15N-labeled Ala-14 sample was lyophilized and then resuspended in 100% D2O.

Sedimentation equilibrium analysis

Sedimentation equilibrium measurements were carried out on a Beckman XL-A (Beckman Coulter) analytical ultracentrifuge using an An-60 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 4°C. Protein samples were dialyzed for 12–16 h against 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.8) or PBS (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl), loaded at initial concentrations of 6, 12, and 18 mg mL−1, and analyzed at rotor speeds of 34 and 37 krpm. Data were acquired at two wavelengths per rotor speed and processed simultaneously using a nonlinear least squares fitting routine (Johnson et al. 1981). Solvent density and protein partial specific volume were calculated according to solvent and protein composition, respectively (Laue et al. 1992). Molecular weights were all within 10% of those calculated for an ideal monomer, with no systematic deviation of the residuals.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

CD spectra were acquired on an Aviv 62DS (Aviv Associates) circular dichroism spectropolarimeter equipped with a Hewlett Packard 89100A temperature controller. Protein samples (10 mg mL−1) in PBS (pH 7.0) were incubated at the desired GdmCl concentration for 24 h. No further signal change was observed after 48 h of incubation. The cuvette was 0.01 cm in pathlength. The wavelength dependence of molar ellipticity, [θ], was monitored at 0°C as the average of five scans, using a 5-sec integration time at 1.0-nm wavelength increments. Spectra were baseline-corrected against the cuvette with buffer alone. Fractional helix content was calculated from the CD signal by dividing the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm by the value expected for 100% helix formation by helices of comparable size, −36,000° cm2 dmole−1 (Luo and Baldwin 1997).

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian INOVA AS600 spectrometer operating at 599.82 MHz equipped with a 5-mm, triple-resonance, three-axis gradient probe. All experiments were performed using gradient-selected sensitivity enhancement for generating phase-sensitive spectra in 1H–15N dimensions (Muhandiram and Kay 1994). Additional acquisition dimensions used States-TPPI data collection for generating phase-sensitive spectra (Marion et al. 1989). The proton carrier was centered on the H2O frequency. The proton chemical shifts were referenced to the H2O frequency measured with respect to DSS. The 15N and 13C chemical shifts were indirectly referenced using referencing ratio values measured by Wishart et al. (1985). NMR sample temperatures were calibrated using either 100% methanol for temperatures below 25°C or 100% ethylene glycol above 25°C. Temperature calibration values for methanol and ethylene glycol standard samples were provided by Varian Instruments. NMR data were processed using the software nmrPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed using SPARKY (Goddard and Kneller 2002). Secondary shifts were calculated using recent random-coil values (Wishart et al. 1995), and the secondary structure predictions based on the observed shifts of 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 15N, 1HN, and 1Hα resonances were performed using the TALOS program (Cornilescu et al. 1999).

NMR assignments

Sequential backbone resonance assignments were achieved using the following triple-resonance experiments acquired on a 15N/13C-labeled sample: HNCA (Farmer et al. 1992), HNCACB (Wittekind and Mueller 1993), HNCO (Kay et al. 1994) at −5°C. Additional triple-resonance experiments were collected at 15°C and 40°C to confirm the assignments and resolve ambiguities. The HNCA experiment was acquired with 1536 (t3), 48 (t2), and 32 (t1) complex points, with spectral widths of 8000 (1HN), 1240 (15N), and 2000 Hz (13Cα), respectively. The HNCACB data set consisted of 1024 (t3), 32 (t2), and 64 (t1) complex points with spectral widths of 5397 (1HN), 1240 (15N), and 8800 Hz (13Cα/β), respectively. The HNCO data were collected with 1536 (t3), 34 (t2), and 70 (t1) complex data points, with spectral widths of 8000 (1HN), 1240 (15N), and 1220 Hz (13C′), respectively. The Hα chemical shifts were assigned with the HCACO30 spectra recorded on a uniformly 15N/13C-labeled sample in 100% D2O buffer at −5°C and 15°C with 1536 (t3), 52 (t2), and 110 (t1) complex data points, and with spectral widths of 8000 (1HN), 2000 (13Cα), and 1460 Hz (13C′), respectively.

The backbone chemical shift assignments were transferred to different temperatures using a series of 2D experiments collected in increments of 5°C from −10°C to 40°C. The HN and N resonances were obtained from the 15N–1H HSQC spectra collected with 1024(t2) and 256(t1) complex data points and spectral widths of 8000 (1H) and 1240 Hz (15N), respectively. Chemical shifts for the 13C′ resonance were identified using 2D H(N)CO spectra acquired with 1536 (t2) and 128 (t1) complex points, and with spectra widths of 8000 (1HN) and 1220 Hz (13C′). The Hα chemical shifts were obtained using the 2D H(CA)CO spectra with 1536 (t2) and 128 (t1) complex points and spectra widths of 8000 (1Hα) and 2000 Hz (13C′), respectively.

NOESY data collection

1H/15N NOESY-HSQC spectra were recorded with a mixing time of 300 msec at 40°C with spectral widths of 8000 Hz (1HN), 800 (15N), and 5400 Hz (1H), with 1024(t3), 48(t2), and 96(t1) complex points, respectively. At −5°C, 1H and 15N HSQC-NOESY-HSQC data were collected (Zhang et al. 1997) with a mixing time of 125 msec using spectral widths of 8000 Hz (1HN), 800 (15N), and 800 Hz (15N), with 1024(t3), 48(t2), and 48(t1) complex points, respectively. Additional 2D NOESY spectra were collected and different mixing times to maximize sensitivity and ensure that spin diffusion effects were minimal. NOESY peaks volumes were integrated using the software SPARKY (Goddard and Kneller 2002).

Measurement of 3JHNHα coupling constants

The 3JHNHα coupling constants were acquired on the 15N-labeled sample using the 2D CT-HMQC-J experiments (Kuboniwa et al. 1994) at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C, with gradient selection and sensitivity enhancement. All three spectra were collected with 1024 (t2) and 50 (t1) complex points, with spectral widths of 8000 (1HN) and 1240 Hz (15N), using dephasing periods of 40, 55, 70, 85, 100, 115, and 130 msec. The data were extracted by fitting the integrated peak intensities as a function of dephasing period, Iy(t), to the following equation (Kuboniwa et al. 1994):

|

(2) |

where

|

(3) |

is the apparent reduction in the JHNHα scalar coupling constant, which is influenced by the longitudinal Hα relaxation time (T1α). The multiple quantum relaxation time for 1HN–15N two-spin coherence is given by T2MQ. The values of T1αwere directly measured using a modified version of the 3D HCACO experiment that incorporated a period for longitudinal proton relaxation. For the T1α measurements, the sample was dissolved in 100% D2O. The 2D Hα–C′ planes were acquired as a function of T1α relaxation delay times of 0.004 (×2), 0.023, 0.05, 0.08, 0.12 (×2), 0.16, 0.22, 0.30, 0.44, and 0.80 sec at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C. The spectral widths were 8000 (1Hα) and 800 Hz (13C′), with 1536 (t2) and 96 (t1) points in the 13C′ dimension. Curve fitting of the data was done using the nonlinear fitting routines implemented in the GNU freeware program GRACE. Backbone φ dihedral angles were derived from 3JHNHα coupling constants using the equation of 3JHN–Hα = 6.98cos2(φ − 60) − 1.38cos(φ − 60) + 1.72 (Wang and Bax 1996).

Measurement of NMR 15N relaxation rates

The 15N longitudinal (R1), transverse (R2), and 1H–15N heteronuclear NOE experiments were performed at −5°C and 40°C with water flip-back pulses using pulse sequences described previously (Farrow et al. 1995b). The proton carrier was set to the frequency of water in all experiments. Spectral widths of the 15N and 1H were set to 800 and 8000 Hz, respectively, with 48 complex points in the 15N dimension and 1024 complex points acquired during acquisition. Duplicate data sets were collected at each temperature to assess experimental error. The R1 and R2 data sets were collected with 8 transients/FID, and the NOE experiments were carried out with 64 transients/FID. For R1 measurements, time delays of 0 (×2), 0.13, 0.28, 0.46 (×2), 0.70, 1.03, and 1.54 sec were done at −5°C and 40°C. For R2 measurements, the relaxation delay times were 0 (×2), 0.051, 0.085, 0.170, 0.255 (×2), 0.374, and 0.544 sec at 40°C, and 0 (×2), 0.017, 0.050, 0.100, 0.151 (×2), 0.202, and 0.269 sec at −5°C. The heteronuclear NOE experiments were performed with and without proton saturation applied to the amide protons. For NOE spectra collected with proton saturation, a 5-sec relaxation period was followed by a 4-sec proton saturation period, whereas NOE spectra recorded in the absence of saturation used a 9-sec relaxation delay. The relaxation data sets were processed as described previously (Skelton et al. 1993; Bracken 2001). Peak height uncertainties from duplicate measurements were used to estimate measurement errors. The R1 and R2 values were determined using a nonlinear fitting to a single exponential function implemented in the program SPARKY (Goddard and Kneller 2002). NOE values were determined as the ratios of the peak intensities measured from spectra acquired with and without proton saturation. Reduced spectral density mapping was performed according to previously published protocols (Farrow et al. 1995b; Bracken et al. 1999).

Electronic supplemental material

Supplemental Table 1: 1H, 15N, 13C backbone chemical shift of Ala 14 at −5°C; Supplemental Table 2: 1H, 15N, 13C backbone chemical shift of Ala 14 at 15°C; Supplemental Table 3: 1H, 15N, 13C backbone chemical shift of Ala 14 at 40°C; Supplemental Table 4: 3JHNHα scalar couplings of Ala 14 at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C; Supplemental Table 5: longitudinal relaxation time, T1α, for Ala 14 at −5°C, 15°C, and 40°C.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI42382 (M.L.), by the Irma T. Hirschl Trust (M.L.), by the American Heart Association (C.B.), and by a Stanley Stahl Fellowship (C.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03383004.

References

- Anderson, N.H., Neidigh, J.W., Harris, S.M., Lee, G.M., Liu, Z., and Tong, H. 1997. Extracting information from the temperature gradient of polypeptide NH chemical shifts. 1. The importance of conformational averaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 199 8547–8561. [Google Scholar]

- Aurora, R. and Rose, G.D. 1998. Helix capping. Protein Sci. 7 21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y., Chung, J., Dyson, H.J., and Wright, P.E. 2001. Structural and dynamic characterization of an unfolded state of poplar apo-plastocyanin formed under nondenaturing conditions. Protein Sci. 10 1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.L. 1995. α-helix formation by peptides of defined sequence. Biophys. Chem. 55 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.L. and Rose, G.D. 1999a. Is protein folding hierarchic? I. Local structure and peptide folding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999b. Is protein folding hierarchic? II. Folding intermediates and transition states. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, R.S. and Gough, C.A. 1996. Circular dichroism of collagen and related polypeptides. In Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules (ed. G. Fasman), pp. 183–199. Plenum, New York.

- Blanco, F.J., Herranz, J., Gonzalez, C., Jimenez, M.A., Rico, M., Santoro, J., and Nieto, J.L. 1992. NMR chemical shifts: A tool to characterize distortions of peptide and protein helices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 9676–9677. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, C. 2001. NMR spin relaxation methods for characterization of disorder and folding in proteins. J. Mol. Graph. 19 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, C., Carr, P.C., Cavanagh, J., and Palmer, A.G. 1999. Temperature dependence of intramolecular dynamics of the basic leucine zipper of GCN4: Implications for the entropy of association with DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 285 2133–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, G., Delaglio, F., and Bax, A. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daggett, V. and Levitt, M. 1992. Molecular dynamics simulations of helix denaturation. J. Mol. Biol. 223 1121–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, P.L. and Sykes, B.D. 1997. Antifreeze proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig, A.J. and Baldwin, R.L. 1995. N- and C-capping preferences for all 20 amino acids in α-helical peptides. Protein Sci. 4 1325–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, A.F., Siligardi, G., and Gibbons, W.A. 1988. Reassessment of the electronic circular dichroism criteria for random coil conformations of poly(L-lysine) and the implications for protein folding and denaturation studies. Biophys. Chem. 31 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, H.J. and Wright, P.E. 1991. Defining solution conformations of small linear peptides. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20 519–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, W.A., Munoz, V., Thompson, P.A., Chan, C.K., and Hofrichter, J. 1997. Submillisecond kinetics of protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, B.T., Venters, R.A., Spicer, L.D., Wittekind, M.G., and Muller, L.A. 1992. A refocused and optimized HNCA: Increased sensitivity and resolution in large macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 2 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Zhang, O., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay, L.E. 1995a. Comparison of the backbone dynamics of a folded and unfolded SH3 domain existing in equilibrium in aqueous buffer. Biochemistry 34 868–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow, N.A., Zhang, O., Szabo, A., Torchia, D.A., and Kay, L.E. 1995b. Spectral density function mapping using 15N relaxation data exclusively. J. Biomol. NMR 6 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans, P.J., Lyu, P.C., Manning, M.C., Woody, R.W., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1991. The helix-coil transition in heterogeneous peptides with specific side-chain interactions: Theory and comparison with CD spectral data. Biopolymers 31 1605–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A.E. and Sanbonmatsu, K.Y. 2001. Exploring the energy landscape of a β-hairpin. Proteins 42 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, T.D. and Kneller, D.G. 2002. SPARKY 3. University of California, San Francisco.

- Gong, Y., Zhou, H.X., Guo, M., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1995. Structural analysis of the N- and C-termini in a peptide with consensus sequence. Protein Sci. 4 1446–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek, S. and Bax, A. 1993. The origin and removal of artifacts in 3D HCACO spectra of proteins uniformly enriched with 13C. J. Magn. Reson. B 102 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer, M.E., Lovett, E.G., d’Avignon, D.A., and Holtzer, A. 1997. Thermal unfolding in a GCN4-like leucine zipper: 13Cα NMR chemical shifts and local unfolding curves. Biophys. J. 73 1031–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmöller, S., Zhou, T., and Ohlson, T. 2002. Conformations of amino acids in proteins. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58 768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.L., Correia, J.J., Yphantis, D.A., and Halvorson, H.R. 1981. Analysis of data from the analytical ultracentrifuge by nonlinear least-squares techniques. Biophys. J. 36 575–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach, N.R., Lyu, P.C., and Zhou, H.X. 1996. CD spectroscopy and the helix-coil transition in peptides and polypeptides. In Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules (ed. G.D. Fasman), pp. 202–259. Plenum Press, New York.

- Kay, L.E., Xu, G.-Y., and Yamazaki, T. 1994. Enhanced sensitivity triple-resonances spectroscopy with minimal H2O saturation. J. Magn. Reson. A 109 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa, H., Grzesiek, S., Delaglio, F., and Bax, A. 1994. Measurement of HN-Hα J couplings in calcium-free calmodulin using new 2D and 3D water-flip-back methods. J. Biomol. NMR 4 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper, M.J., Fecondo, J.V., and Wong, M.G. 2002. Rational design of α-helical antifreeze peptides. J. Pept. Res. 59 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz, I.D., Kosen, P.A., and Craig, E.C. 1991. Amide chemical shifts in many helices in peptides and proteins are periodic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 1406–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, E., Viguera, A.R., and Serrano, L. 1998. Elucidating the folding problem of α-helices: Local motifs, long-range electrostatics, ionic-strength dependence and prediction of NMR parameters. J. Mol. Biol. 284 173–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue, T.M., Shah, B.D., Ridgeway, T.M., and Pelletier, S.L. 1992. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In Analytical ultracentrifugation in biochemistry and polymer science (eds. S.E. Harding et al.), pp. 90–125. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK.

- Lavigne, P., Sonnichsen, F.D., Kay, C.M., and Hodges, R.S. 1996. Interhelical salt bridges, coiled-coil stability, and specificity of dimerization. Science 271 1136–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. and Lu, M. 2002. An alanine-zipper structure determined by long range intermolecular interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 277 48708–48713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M., Ji, H., and Shen, S. 1999. Subdomain folding and biological activity of the core structure from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41: Implications for viral membrane fusion. J. Virol. 73 4433–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, P.Z. and Baldwin, R.L. 1997. Mechanism of helix induction by trifluoroethanol: A framework for extrapolating the helix-forming properties of peptides from trifluoroethanol/water mixtures back to water. Biochemistry 36 8413–8421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A. 1997. Predicting coiled-coil regions in proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, P.C., Gans, P.J., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1992. Energetic contribution of solvent-exposed ion pairs to α-helix structure. J. Mol. Biol. 223 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D., Ikura, M., Tschudin, R., and Bax, A. 1989. Rapid recording of 2D NMR spectra without phasecycling: Application to the study of hydrogen exchange in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 85 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Marley, J., Lu, M., and Bracken, C. 2001. A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 20 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqusee, S. and Baldwin, R.L. 1987. Helix stabilization by Glu-. . .Lys+ salt bridges in short peptides of de novo design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84 8898–8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merutka, G., Dyson, H.J., and Wright, P.E. 1995. ‘Random coil’ 1H chemical shifts obtained as a function of temperature and trifluoroethanol concentration for the peptide series GGXGG. J. Biomol. NMR 5 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhandiram, D.R. and Kay, L.E. 1994. Gradient-enhanced triple-resonance three dimensional NMR experiments with improved sensitivity. J. Magn. Res. B 103 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, V. 2001. What can we learn about protein folding from Ising-like models? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, V. and Serrano, L. 1995a. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. II. Helix macrodipole effects and rational modification of the helical content of natural peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 245 275–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995b. Helix design, prediction and stability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 6 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J.K. and Oas, T.G. 1999. Reinterpretation of GCN4-p1 folding kinetics: Partial helix formation precedes dimerization in coiled coil folding. J. Mol. Biol. 289 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. Mechanism of fast protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71 783–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otlewski, J. and Cierpicki, T. 2001. Amide proton temperature coefficients as hydrogen bond indicators in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 21 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A.G. and Bracken, C. 1999. Spin relaxation methods for characterization of picosecond-nanosecond and microsecond-millisecond motions in proteins. In NMR in supramolecular chemistry (ed. M. Pons), pp. 171–190. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands.

- Park, S.H., Shalongo, W., and Stellwagen, E. 1997. The role of PII conformations in the calculation of peptide fractional helix content. Protein Sci. 6 1694–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxco, K.W., Morton, C.J., Grimshaw, S.B., Jones, J.A., Pitkeathly, M., Campbell, I.D., and Dobson, C.M. 1997. The effects of guanidine hydrochloride on the ‘random coil’ conformations and NMR chemical shifts of the peptide series GGXGG. J. Biomol. NMR 10 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippon, W.B. and Walton, A.G. 1971. Optical properties of the polyglycine II helix. Biopolymers 10 1207–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohl, C.A. and Baldwin, R.L. 1998. Deciphering rules of helix stability in peptides. Methods Enzymol. 295 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalongo, W., Dugad, L., and Stellwagen, E. 1994. Analysis of the thermal transitions of a model helical peptide using 13C NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 2500–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z. 2002. “ Structure in the unfolded state of polypeptides and stabilizing interactions in α-helices and proteins.” Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

- Shi, Z., Woody, R.W., and Kallenbach, N.R. 2002. Is polyproline II a major backbone conformation in unfolded proteins? Adv. Protein Chem. 62 163–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle, D. and Ackerman, M.S. 2001. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science 293 487–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu, W., Liu, J., Ji, H., and Lu, M. 2000. Core structure of the outer membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 299 1101–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalicky, J.J. and Szyperski, T. 2000. Toward structural biology in supercooled water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 3230–3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton, N.J., Palmer, A.G., Akke, M., Kördel, J., Rance, M., and Chazin, W.J. 1993. Practical aspects of two-dimensional proton-detected 15N spin relaxation measurements. J. Magn. Reson. B 102 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.J., Bolins, K.A., Schwalbe, H., MacArthur, M.W., Thornton, J.M., and Dobson, C.M. 1996. Analysis of main chain torsion angles in proteins: Prediction of NMR coupling constants for native and random coil conformations. J. Mol. Biol. 225 494–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnick, T.R., Jackson, S., Wilk, R.R., Englander, S.W., and DeGrado, W.F. 1996. The role of helix formation in the folding of a fully α-helical coiled coil. Proteins 24 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek, E.J., Bui, A.H., Lu, M., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1998. Surface salt bridges stabilize the GCN4 leucine zipper. Protein Sci. 7 2431–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek, E.J., Olson, C.A., Shi, Z., and Kallenbach, N.R. 1999. Alanine is an intrinsic α-helix stabilizing amino acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 5571–5572. [Google Scholar]

- Sreerama, N. and Woody, R.W. 1994. Poly(pro)II helices in globular proteins: Identification and circular dichroic analysis. Biochemistry 33 10022– 10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999. Molecular dynamics simulations of polypeptide conformations in water: A comparison of α, β, and poly(pro)II conformations. Proteins 36 400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany, M.L. and Krimm, S. 1968. New chain conformation of poly(glutamic acid) and polylysine. Biopolymers 6 1379–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.C. and Bax, A. 1996. Determination of the backbone dihedral angles φ in human ubiquitin from reparameterized empirical Karplus equations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118 2483–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, D.G., Arne, H., Hodges, R.S., and Sykes, B.D. 1985. 1H, 13C, 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigation of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR 5 67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Sykes, B.D., and Richards, F.M. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222 311–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Yao, J., Abildgaard, F., Dyson, J.J., Oldfield, E., Markley, J.L., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 6 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittekind, M. and Mueller, L. 1993. HNCACB, a high sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with α-and proton and nitrogen resonances with α- and β-carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. B 101 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, R.W. 1992. Circular dichroism and conformation of unordered polypeptides. Adv. Biophys. Chem. 2 37–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.E. and Dyson, H.J. 1999. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: Re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 293 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, O., Forman-Kay, J.D., Shortle, D., and Kay, L.E. 1997. Triple-resonance NOESY-based experiments with improved spectral resolution: Application to structural characterization of unfolded, partially folded and folded proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 9 181–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. and Laursen, R.A. 1999. Artificial antifreeze polypeptides: α-helical peptides with KAAK motifs have antifreeze and ice crystal morphology modifying properties. FEBS Lett. 455 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N.E., Zhu, B-Y., Sykes, B.D., and Hodges, R.S. 1992. Relationship between amide proton chemical shifts and hydrogen bonding in amphipathic α-helical peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 4320–4326. [Google Scholar]

- Zitzewitz, J.A., Ibarra-Molero, B., Fishel, D.R., Terry, K.L., and Matthews, C.R. 2000. Preformed secondary structure drives the association reaction of GCN4-p1, a model coiled-coil system. J. Mol. Biol. 296 1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]