Abstract

The fully reduced hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL), which is a good model of random coil structure, has been converted to highly organized amyloid fibrils at low pH by adding ethanol. In the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol, the fully reduced HEWL adopts β-sheet secondary structure at pH 4.5 and 5.0, and an α-to-β transition is observed at pH 4.0. A red shift of the Congo red absorption spectrum caused by the precipitation of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol is typical of the presence of amyloid aggregation. EM reveals unbranched fibrils with a diameter of 2–5 nm and as long as 1–2 μm. The pH dependence of the initial structure of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol suggests that Asp and His residues may play an important role.

Keywords: Amyloid fibril formation, hen lysozyme, disulfide reduction

Protein amyloid aggregation has been recognized as a major cause of several important diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (the fourth most common cause of death in the Western world), Parkinson’s disease, type II or noninsulin-dependent diabetes, and the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. About 17 different proteins have been found to form amyloid in vivo. Amyloid fibrils formed from those proteins share some common morphological features, but these proteins do not have a conserved sequence or native structural motif (Kelly 1996; Lansbury 1999).

Recent studies show that amyloid formation is not only possible with disease-associated proteins, but also with proteins that are not associated with any known amyloid diseases under certain conditions (Guijarro et al. 1998; Chiti et al. 1999; Dobson 1999; Fandrich et al. 2001; Kallberg et al. 2001). Hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL), an extensively studied small protein with four disulfide bonds, is a recent example (Goda et al. 2000; Krebs et al. 2000). Amyloid fibrils formed from all these proteins that are not associated with any known amyloid diseases not only share similar morphological features with amyloid fibrils from disease-associated proteins, but also can be inherently highly cytotoxic (Bucciantini et al. 2002). Based on these observations, Dobson proposed that amyloid aggregation was a generic property of all polypeptides (Guijarro et al. 1998; Dobson 1999).

Study of the amyloid aggregation of nondisease-associated proteins cannot only help us understand the mechanism of amyloid fibrillogenesis, but also extend our understanding of the basic relationship between protein sequence and structure. A common strategy to convert a nondisease-associated protein to amyloid fibrils is destabilizing the protein either by mutation or by partial denaturation with heating or addition of alcohols (Chiti et al. 1999; Rochet and Lansbury 2000). Most of the above studies are based on partially denaturing the native structure of the target proteins; in other words, those target proteins still maintain a substantial amount of their native structures. One question remaining is whether or not unstructured polypeptides can form amyloid fibrils. To address this question, we used here the fully reduced HEWL as a random coil model polypeptide. In this article, we show that under appropriate conditions, the fully reduced HEWL can be converted to typical amyloid fibrils.

Results

Reduction of HEWL and structural characterization of the fully reduced HEWL

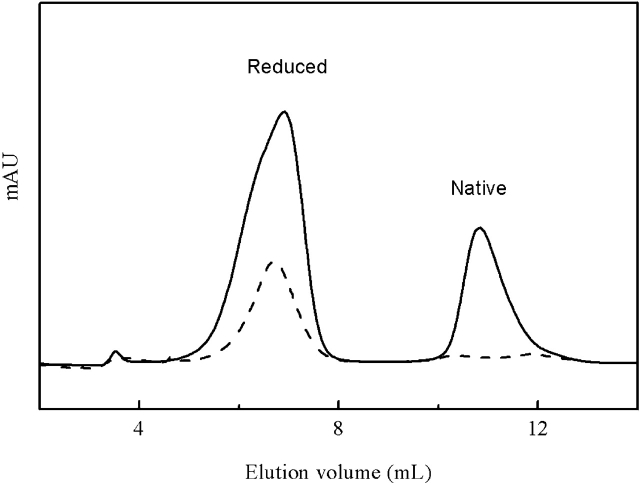

AEMTS is an efficient free sulfhydryl blocking reagent, and it will add one positive charge to the blocked protein for every sulfhydryl blocked (Kenyon and Bruice 1977), making it easy to separate different partially reduced proteins by cation exchange chromatography (Cao et al. 2001). As shown in Figure 1 ▶, HEWL is very difficult to be fully reduced by DTTred. If the system is not protected from the air oxidation, substantial native HEWL peak can be detected after 24 h reduction in the presence of 7 M GdHCl, 0.2 M DTTred at pH 8.6. While under the protection of nitrogen gas, a very nice symmetric fully reduced HEWL peak can be observed, and no detectable native HEWL. The purity of the fully reduced HEWL obtained here is greater than 95%, and nonreduced HEWL is negligible.

Figure 1.

Cation exchange chromatographs of partially reduced (bold line) and fully reduced HEWL (dashed line).

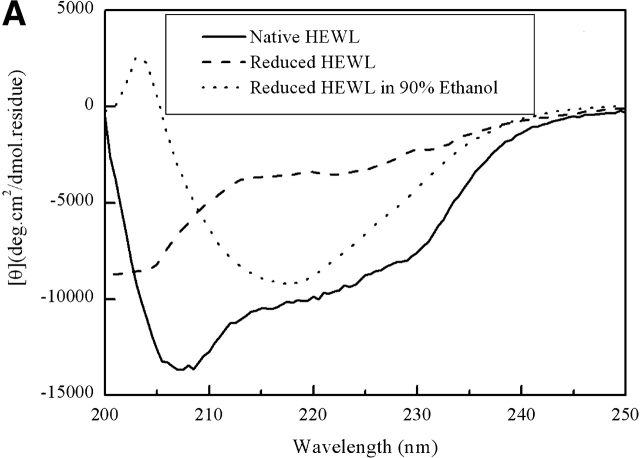

The CD spectra of the fully reduced HEWL (Fig. 2 ▶) show no tertiary structure, and the negative peak at about 200 nm is a common CD feature of random coil structure. Therefore, the fully reduced HEWL can be used as a model of random coil polypeptide.

Figure 2.

Far-UV (A) and near-UV (B) CD spectra (at pH 4.5) of native HEWL (bold line), fully reduced HEWL (dashed line), and fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol (dotted line).

Inducing structure from the fully reduced HEWL

For all amyloidogenic proteins to self-assembly into fibrils, an intermediate with an ordered secondary structure and a nonnative tertiary structure must be populated to some extent. Both TFE and ethanol have been widely used to change the conformation of proteins and polypeptides, and have been successfully used to induce protein amyloid formation in vitro (Chiti et al. 1999; Goda et al. 2000; Krebs et al. 2000). To induce structure from the fully reduced HEWL, both TFE and ethanol were tested.

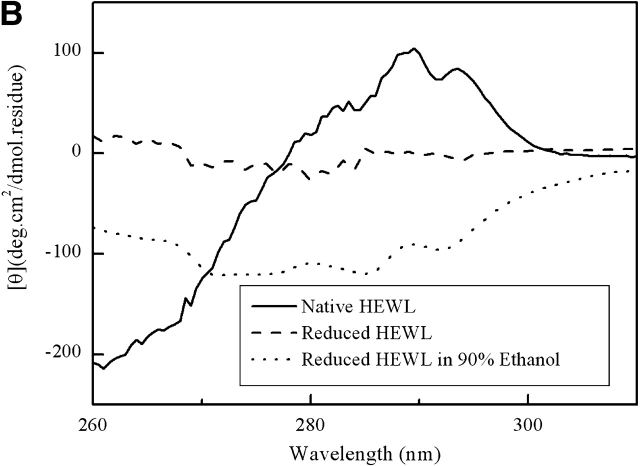

Figure 3 ▶ shows that TFE at concentration of 10% (v/v) can induce substantial α-helical structure in the fully reduced HEWL, and increasing the concentration of TFE only slightly increases the amount of induced α-helical structure. The induced α-helical structure is stable. No sign of α-to-β transition or amyloid fibrillogenesis was observed after weeks of incubation.

Figure 3.

CD spectra of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of different concentration of TFE.

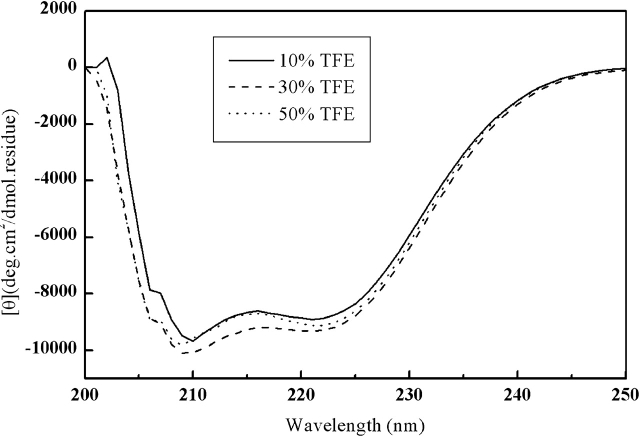

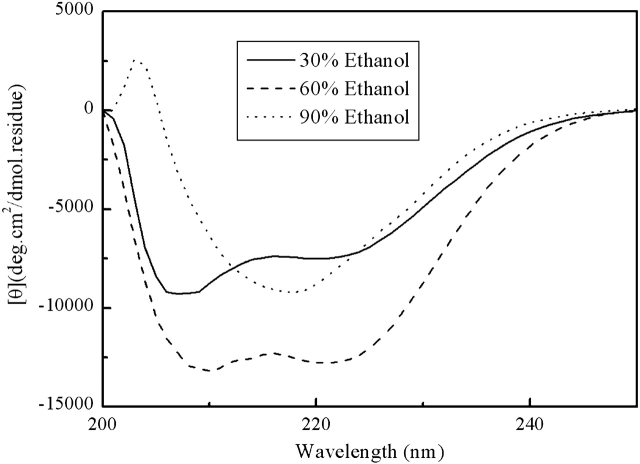

Figure 4 ▶ shows the CD spectra of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of different concentrations of ethanol at pH 4.5. At low concentration, ethanol can induce α-helical structure in the fully reduced HEWL. However, at high concentration of ethanol (≥90% v/v), the CD spectrum shows a single negative peak around 215 nm, which is a typical feature of β-structure.

Figure 4.

CD spectra of the fully reduced HEWL at pH 4.5 in the presence of different concentration of ethanol.

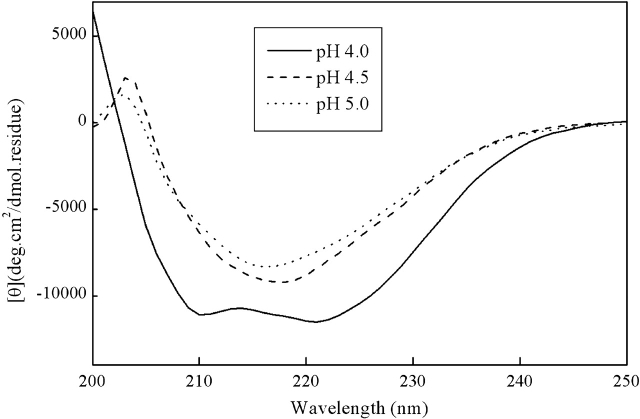

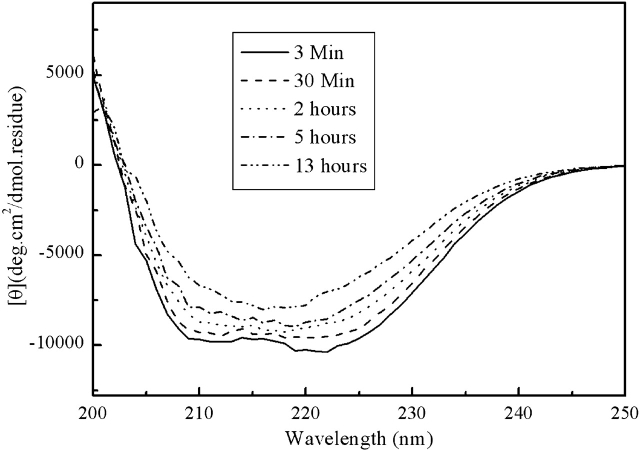

As shown in Figure 5 ▶, the initial conformation of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol is also pH dependent. At pH 4.5 and 5.0, β-structure is formed almost immediately (within 3 min of manual mixing and spectrum recording time); while at pH 4.0, the initial conformation is mainly α-helical. The initial α-helical conformation at pH 4.0 will gradually transform to a β-structure after incubation for several hours at room temperature (Fig. 6 ▶). An interesting result is that the CD spectra (and so the β-structure contents) at all three pH conditions after 24-h incubation are similar, indicating that the difference among different pH conditions is kinetical.

Figure 5.

Initial CD spectra (about 3 min after mixing with ethanol) of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.0 (bold line), 4.5 (dashed line), and 5.0 (dotted line).

Figure 6.

Conformational change process of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.0. The first and last CD spectra were recorded at 3 min and 13 h postincubation, respectively.

To examine the protein concentration-dependent conformational changes, the CD spectra of 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, and 2.0 mg/mL fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.5 were recorded (data not shown). Results show that the initial β-structure of the fully reduced HEWL does not change with the change of protein concentration in the range used here.

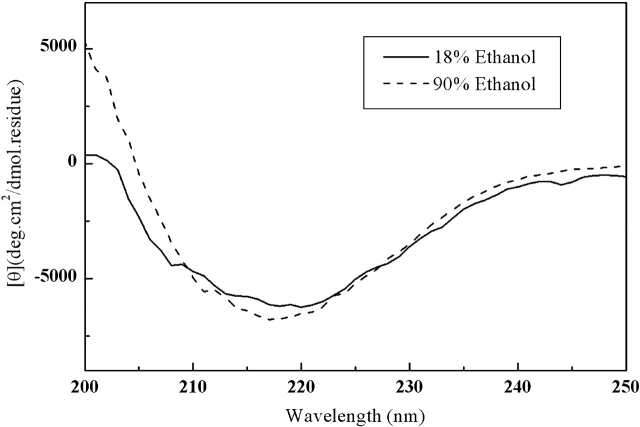

To examine the stability of the β-structure of the fully reduced HEWL and the reversibility of the conformation transformation, fully reduced HEWL incubated in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.5 was diluted fivefold to a final ethanol concentration of 18% (v/v). The CD spectra of the original and diluted solutions (Fig. 7 ▶) show that the diluted solution maintains most of the original β-structure. As 18% (v/v) ethanol cannot induce a β-structure in the fully reduced HEWL, this result demonstrates that the ethanol-induced β-structure of the fully reduced HEWL is relatively stable, and the reverse transformation from a β-structure to a helical structure is very slow. This is also an indication that the β-structure may be formed intermolecularly.

Figure 7.

CD spectra of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.5 (bold line) and the same solution diluted fivefold (dashed line).

As shown in Figure 2B ▶, the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol has some nonnative near-UV CD signal, indicating the existence of some nonnative hydrophobic packing.

Amyloid fibrils characterization

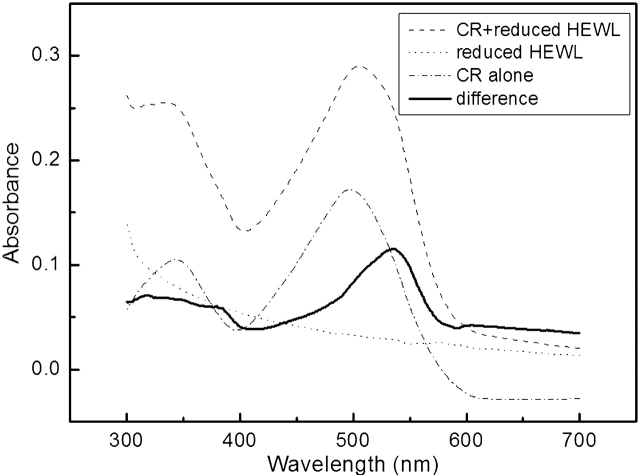

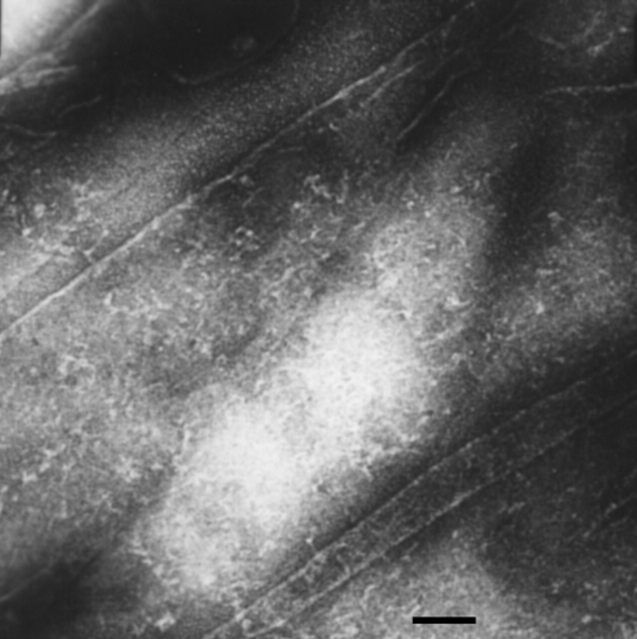

The fully reduced HEWL was incubated at room temperature, both in the absence and presence of 2–6 mM DTTred. At high concentration of the fully reduced HEWL (≥4 mg/mL), Gel is formed after about a week’s incubation. Congo red binding assay of the aggregations of the fully reduced HEWL (Fig. 8 ▶) shows a red shift of the maximum absorbance of Congo red from 497 nm to 537 nm, which is a characteristic of amyloid aggregation. EM (Fig. 9 ▶) reveals fibrils of 2–5 nm in diameter and as long as 1–2 μm in length.

Figure 8.

Absorbance spectra of a suspension of 1 μM incubated fully reduced HEWL alone (dotted line) and in the presence of 10 μM CR (dashed line), and of CR alone (dotted dashed line). The difference spectrum (bold line) is obtained by subtracting the spectra of reduced HEWL alone and CR alone from the spectrum of HEWL + CR.

Figure 9.

Electron micrograph of negatively stained fibrils formed from fully reduced HEWL, incubated at room temperature for 2 mo (scale bar = 100 nm).

Discussion

α-to-β transition and amyloid fibril formation

The transformation of an α-helical segment of monomeric PrPC to a β-strand conformation is the main cause/result of the formation of aggregated PrPSc (Harrison et al. 1997), and an α-to-β transition is also regarded as a key step in the amyloid β-protein fibrillogenesis (Kirkitadze et al. 2001). α-to-β transition is also a common feature of amyloid fibrillogenesis in vitro from both nature proteins and designed peptides (Mihara and Takahash 1997; Fezoui et al. 2000). On the other hand, a survey of 1324 nonredundant proteins in PDB shows 37 segments of at least seven residues, which exist as helices in their native state, were predicted as β-strand structure; and experiments have managed to convert some of them into amyloid fibrils (Kallberg et al. 2001). These studies support the hypothesis that either α-to-β conformational changes or α/β-discordant helices in amyloidogenic proteins lead to amyloid fibril formation and cause diseases (Kelly 1996; Kallberg et al. 2001).

It is worthy to note that the fully reduced HEWL undergoes an α-to-β transition in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.0. Although no α-to-β transition step has been observed at pH 4.5 and pH 5.0, the similar amount of intermolecular β-structure induced by ethanol at all three pH conditions after 24-h incubation suggests that α-to-β transition steps might exist at pH 4.5 and 5.0 also, but with a faster kinetics that is not observable due to the slow mixing and spectrum recording time. In other words, the pH condition can significantly affect the α-to-β transition kinetics. CD spectra of native HEWL also show that HEWL has more α-helical structure at pH around 4.5 (data not shown) as judged by the CD value at 220 nm. A pH dependence of the kinetics was also observed in the first step in the Aβ amyloid fibrillogenesis, with two sharp transitional zones that were coincident with the pK values of Asp and His, and the most rapid kinetics occurred in the pH range of 4.5–5.0 (Kirkitadze et al. 2001). Therefore, the pH dependence of the α-to-β transition kinetics for the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol may be due to the ionization/protonation of Asp and His residues.

α-to-β transition is also observed in the correct folding pathway of β-lactoglobulin (Kuwajima et al. 1987; Kuwata et al. 2001), which shows a CD signal overshoot at a millisecond time scale. Similar overshoot in the folding pathway of HEWL has been mainly contributed to the distortion of disulfide bonds (Chaffotte et al. 1992). However, pH (Cao et al. 2002) and organic solvents (Lai et al. 2000), such as ethanol and TFE, can significantly change the amplitude of the overshoot of HEWL, suggesting some degree of α-to-β transition in the early folding stage of HEWL. It is not clear whether or not there is any kind of correlation between the α-to-β transitions in the fibrillogenesis and folding process of HEWL.

Comparison with the fibrillogenesis of disulfide-intact HEWL

The fibrillogeneses of the disulfide-intact and the fully reduced HEWL show obvious differences. The fully reduced HEWL in the absence of structure-inducing reagents such as ethanol shows no ordered structure, and can be roughly considered as a random coil model, as shown in Figure 2 ▶. In the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol, the disulfide-intact HEWL is destabilized and partially unfolded, the very first intermediate, before the formation of interpolypeptide interaction and intermolecular β-structure, is possibly also a folding intermediate. Although the peptide chain of the fully reduced HEWL, without the four disulfide bonds’ constraint, is flexible and can explore much greater conformational space than the disulfide-intact HEWL, so, even after significant α-helical structure formed in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol at pH 4.0, the early α-helical intermediate is totally different from that of the disulfide-intact HEWL, and is not likely relevant to the folding process of HEWL. As can be seen in Figure 2 ▶, both secondary and tertiary structures in the presence of 90% (v/v) ethanol are different between the disulfide-intact (Goda et al. 2000) and the fully reduced HEWL.

The different flexibilities and structures between the native and the fully reduced HEWL might be one of the causes of the different morphology between the final amyloid fibrils. Different mechanisms might also be involved. The fibrils formed from the fully reduced HEWL has a diameter of 2–5 nm, which is thinner than 7 nm for the native HEWL (Goda et al. 2000; Krebs et al. 2000). But it is also possible that other reasons, such as incubating conditions, may be more important to the morphology of the amyloid fibrils.

The fibrillogenesis of the fully reduced HEWL is also different from the fibrillogenesis of the 3S lysozyme reported recently (Takase et al. 2002). The 3S lysozyme, which maintains most of the native structure of disulfide-intact lysozyme with only subtle difference (Takase et al. 2002), is also one way to partially destabilize lysozyme’s native structure. Therefore, the fibrillogenesis of 3S lysozyme is more relevant to that of disulfide-intact lysozyme than to that of fully reduced HEWL. In the same report, an extensively reduced lysozyme is also converted to a protofilament. But this extensively reduced lysozyme is not fully reduced as pointed out by the authors (Takase et al. 2002); so it cannot be used as a random coil model. While in our experiments, the purity of the fully reduced HEWL is greater than 95% as checked by cation exchange chromatography.

In this article, we have managed to convert the fully reduced HEWL, a nearly random coil polypeptide, to highly ordered amyloid fibrils. Our results support Dobson’s hypothesis (Guijarro et al. 1998; Dobson 1999) that amyloid fibrillogenesis is a generic property of all polypeptides.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Ultrapure GdHCl and DTTred were purchased from Sigma. AEMTS was prepared according to the method of Kenyon and Bruice (1977). Water used was of Millipore quality. All others chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available.

Preparation of the fully reduced HEWL

HEWL (15 mg/mL) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 7M GdHCl, and 0.2 M DTTred at pH 8.6 was degassed by humidified ultrapure nitrogen gas and incubated for 24 h at room temperature. The reduced HEWL solution was acidified to pH 3 by acetic acid, and then desalted by elution on a G25 superfine column with 100 mM acetic acid solution. The purified protein was ultrafiltered by Ultrafree-15 (MWCO 5000, Millipore) to a final concentration of 10–20 mg/mL (in the presence of 100 mM acetic acid), and stored at −20°C. The purity of the reduced HEWL (>95%) was checked on cation exchange chromatography (HiTrap SP), after being blocked with AEMTS at pH 8.0.

To prevent oxidation, all the experiments were carried out at acidic condition. For long-time incubation, experiments were also carried out in the presence of 2–6 mM DTTred for comparison.

Preparation of the fully reduced HEWL amyloid fibrils

Stock solution of the fully reduced HEWL were dissolved at a concentration of about 2 mg/mL in 90% ethanol, 20 mM acetic acid, pH 4.5, with/without 2 mM DTTred; the resulting solution was incubated at room temperature for different lengths of time. To accelerate the formation of fibrils, after 24 h of incubation at the above condition, the above solutions were concentrated to about one-third of its original volume by purge of dry ultrapure nitrogen, and then incubated at room temperature. Incubation of the fully reduced HEWL in the presence of 2–6 mM DTTred shows no significant difference from that in the absence of DTTred, that is, air oxidation in the acidic solution used in all our experiments is negligible even in the absence of DTTred.

Circular dichroism

CD spectra were recorded on Jobin Yvon CD6 with 1-mm and 0.1-mm pathlength cylinder quartz cuvettes for near UV and far UV, respectively. The concentrations of HEWL were determined by UV absorbance at 280 nm, with extinction coefficients (ɛ1mg/mL) of 2.63 and 2.37 for native and reduced HEWL, respectively (Goldberg et al. 1991).

Congo red binding assay

A 200-μM stock solution of Congo red was prepared in 50 mM PBS, 100 mM NaCl, and 10% ethanol at pH 6.9. Ethanol was added to the stock solution to prevent CR micelle formation. The CR solution was filtered three times through a 0.2-μM filter before use. In a typical assay, the protein sample was mixed with a solution of CR to yield a final CR concentration of 10 μM and a final protein concentration of 1–3 μM, and then incubated at room temperature for at least 30 min before recording the absorbance spectrum on a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 45 spectrometer.

Electron microscopy

Samples were first filtered to remove nonaggregated material, using a Centricon YM-100 filter (Amicon), and then diluted 10-fold. A 5-μL drop of the diluted solution was applied to a carbon-coated Formvar grid, and blotted after 30 sec. A 5-μL drop of 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate solution was placed on the grid, and blotted after 10 sec, and then washed by a drop of deionized water and air dried. The resulting grid was examined using a JEOL JEM 100CX transmission electron microscope.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (20203001, 90103029), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2001AA235111), and Ministry of Education of China.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

HEWL, hen egg white lysozyme

DTTred, reduced DL-dithiothreitol

TFE, trifluoroethanol

CD, circular dichroism

CR, congo red

GdHCl, guanidine hydrochloride

AEMTS, 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate

EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

Tris-HCl, tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane hydrochloride

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03183404.

References

- Bucciantini, M., Giannoni, E., Chiti, F., Baroni, F., Formigli, L., Zurdo, J., Taddei, N., Ramponi, G., Dobson, C.M., and Stefani, M. 2002. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding disease. Nature 416 507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A., Welker, E., and Scheraga, H.A. 2001. Effect of mutation of proline 93 on redox unfolding/folding of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A. Biochemistry 40 8536–8541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A., Wang, G., Lai, L., and Tang, Y. 2002. Linear correlation between the thermal stability and folding kinetics of lysozyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291 795–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffotte, A.F., Guillou, Y., and Goldberg, M.E. 1992. Kinetic resolution of peptide bond and side chain far UV circular dichroism during the folding of hen egg white lysozyme. Biochemistry 31 9694–9702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti, F., Webster, P., Taddei, N., Clark, A., Stefani, M., Ramponi, G., and Dobson, C.M. 1999. Designing conditions for in vitro formation of amyloid protofilaments and fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 3590–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, C.M. 1999. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrich, M., Fletcher, M.A., and Dobson, C.M. 2001. Amyloid fibrils from muscle myoglobin. Nature 410 165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fezoui, Y., Hartley, D.M., Walsh, D.M., Selkoe, D.J., Osterhout, J.J., and Teplow, D.B. 2000. A de novo designed helix-turn-helix peptide forms nontoxic amyloid fibrils. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 1095–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda, S., Takano, K., Yamagata, Y., Nagata, R., Akutsu, H., Maki, S., Namba, K., and Yutani, K. 2000. Amyloid protofilament formation of hen egg lysozyme in highly concentrated ethanol solution. Protein Sci. 9 369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, M.E., Rudolph, R., and Jaenicke, R. 1991. A kinetic study of the competition between renaturation and aggregation during the refolding of denatured-reduced egg white lysozyme. Biochemistry 30 2790–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro, J.I.I., Sunde, M., Jones, J.A., Campbell, I.D., and Dobson C.M. 1998. Amyloid fibril formation by an SH3 domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 4224–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, P.M., Bamborough, P., Daggett, V., Prusiner, S.B., and Cohen, F.E. 1997. The prion folding problem. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallberg, Y., Gustafsson, M., Persson, B., Thyberg, J., and Johansson, J. 2001. Prediction of amyloid fibril-forming proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276 12945–12950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.W. 1996. Alternative conformations of amyloidogenic proteins govern their behavior. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, G.L. and Bruice, T.W. 1977. Novel sulfhydryl reagents. Methods Enzymol. 47 407–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkitadze, M.D., Condron, M.M., and Teplow, D.B. 2001. Identification and characterization of key kinetic intermediates in amyloid B-protein fibrillogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 312 1103–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, M.R., Wilkins, D.K., Chung, E.W., Pitkeathly, M.C., Chamberlain, A.K., Zurdo, J., Robinson, C.V., and Dobson, C.M. 2000. Formation and seeding of amyloid fibrils from wild-type hen lysozyme and a peptide fragment from the β-domain. J. Mol. Biol. 300 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwajima, K., Yamaya, H., Miwa, S., Sugai, S., and Nagamura, T. 1987. Rapid formation of secondary structure framework in protein folding studied by stopped-flow circular dichroism. FEBS Lett. 221 115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwata, K., Shastry, R., Cheng, H., Hoshino, M., Batt, C.A., Goto, Y., and Roder, H. 2001. Structural and kinetic characterization of early folding events in β-lactoglobin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, B., Cao, A., and Lai, L. 2000. Organic cosolvents and hen egg white lysozyme folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1543 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbury, P.T. 1999. Evolution of amyloid: What normal protein folding may tell us about fibrillogenesis and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 3342–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara, H. and Takahash, Y. 1997. Engineering peptides and proteins that undergo α-to-β transitions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, J. and Lansbury, P.T. 2000. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: Themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase, K., Higashi, T., and Omura, T. 2002. Aggregate formation and the structure of the aggregates of disulfide-reduced proteins. J. Protein Chem. 21 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]