Abstract

Searching for nervous system candidates that could directly induce T cell cytokine secretion, I tested four neuropeptides (NPs): somatostatin, calcitonin gene-related peptide, neuropeptide Y, and substance P. Comparing neuropeptide-driven versus classical antigen-driven cytokine secretion from T helper cells Th0, Th1, and Th2 autoimmune-related T cell populations, I show that the tested NPs, in the absence of any additional factors, directly induce a marked secretion of cytokines [interleukin 2 (IL-2), interferon-γ, IL-4, and IL-10) from T cells. Furthermore, NPs drive distinct Th1 and Th2 populations to a “forbidden” cytokine secretion: secretion of Th2 cytokines from a Th1 T cell line and vice versa. Such a phenomenon cannot be induced by classical antigenic stimulation. My study suggests that the nervous system, through NPs interacting with their specific T cell-expressed receptors, can lead to the secretion of both typical and atypical cytokines, to the breakdown of the commitment to a distinct Th phenotype, and a potentially altered function and destiny of T cells in vivo.

Keywords: T helper cells 1 and 2

T cells secrete various cytokines through which they affect a broad spectrum of normal and pathological immune processes. The current dogma is that T cells can be stimulated to secrete cytokines mainly, if not solely, by antigens processed and presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and by immunocyte-derived factors, such as cytokines and chemokines.

CD4+ T cells can actually be divided into at least two major mutually exclusive T cell subsets distinguished according to their cytokine secretion profile. Upon antigenic-stimulation, T helper 1 (Th1) cells secrete interleukin 2 (IL-2), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), whereas Th2 cells release IL-4 and IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10. Th1 cells are major players in delayed-type hypersensitivity and pro-inflammatory responses, whereas Th2 cells induce B cell growth and differentiation and thus induce Ig production. Interestingly, the differentiation of CD4+ T cells from pluripotent precursor Th0 cells to either Th1 or Th2 cells is determined predominantly by the cytokine environment (primarily by the respective levels of IFN-γ, IL-12 and IL-4) (1). Moreover, the T cells themselves may participate in the Th1/Th2 decision process, through autocrine activation loops (2).

Segregation of T cells to Th1/Th2 is based only on the level of cytokine secretion because intracellular determination of cytokines show that the dichotomy is not necessarily absolute (2–4).

Cytokine secretion by helper T cells is particularly important in autoimmunity (5) because chronic autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis are predominantly caused by Th1 cells. Th2 cells can antagonize Th1 functions (6) and in numerous autoimmune conditions prevent and/or cure autoimmune diseases. However, recent studies found exceptions to this rule, suggesting that the in vivo behavior of a given T cell population may be unpredictable from its in vitro cytokine secretion profile. For example, (i) anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) Th2-type T cells can be not only inefficient suppressors of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) induced by effector Th1 cells (7), but can cause EAE (8); thus Th1 and Th2 cells can both transfer EAE; (ii) anti-MBP Th0-type T cells (producing both Th1 and Th2 cytokines) can be encephalitogenic and able to transfer EAE to naive mice (9); and (iii) Th2-type T cells can induce pancreatitis and diabetes in immune-compromised nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice (10).

Interestingly, from a different angle of the topic, it was recently observed that that the cytokine secretion of the same T cell population was different in the lymph nodes (producing both Th1 and Th2 cytokines) than in the central nervous system (CNS) environment (producing only Th1 cytokines). This observation suggested that within the CNS, specific factors (mainly IL-12 producing microglia acting as APCs, not neurons) can modulate the cytokine secretion of T cells, can select Th1/Th2 pathway, and can control effector CD4+ T cell cytokine profile in EAE (9).

Based on these findings and others, I speculated that T cells may be influenced, especially in the CNS, by effector molecules other than their specific antigen or lymphocyte-derived factors. Such influence may be manifested by an altered pattern of cytokine secretion, that may further affect T cell-mediated processes in general, and determine whether autoimmune T cells would become pathogenic or protective in particular.

In search for such nerve-secreted candidates that could directly induce T cell cytokine secretion, I studied the direct effects of four NPs: somatostatin (SOM), calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), neuropeptide Y (NPY), and substance P (Sub P). These NPs are secreted from nerve endings in the peripheral and CNS, as well as in all the lymphoid organs, where T cells reside (11).

Previous studies have shown that T cells carry specific receptors for SOM, CGRP, Sub P, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (12–17), and the three former, as well as NPY, were found in a previous study (18) to directly affect T cell activation and subsequent integrin-mediated adhesion to extracellular matrix components via their specific T cell expressed NP receptors.

In the present study, SOM, CGRP, NPY, and Sub P were tested for their respective ability to directly induce cytokine secretion from several autoimmune-related antigen-specific Th0, Th1, and Th2 T cells, and NP-driven cytokine secretion was compared with classical antigenic-stimulated cytokine secretion.

My results show that NPs, in the absence of any additional molecules, directly induce a marked secretion of cytokines (IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10) from T cells. Moreover, the tested NPs were found to have the ability to drive distinct Th1 and Th2 populations to a “forbidden” cytokine secretion: secretion of Th2 cytokines from a Th1 T cell line and vice versa, a phenomenon that could not be triggered by classical antigenic stimulation. This breakdown of the strict commitment of T cells to a distinct Th1 or Th2 profile may result in a potentially altered function and destiny of T cells in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

SJL/J female mice and NOD/Lt male mice were from The Jackson Laboratory.

Materials.

MBP87–99 peptide and NPY were synthesized by standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry and purified by HPLC. Recombinant Hsp-65 and Cop 1 were prepared as described, respectively (19, 20). SOM, CGRP, and Sub P were from Sigma.

Initiation and Propagation of Antigen-Specific T Cell Lines.

Numerous anti-MBP87–99 T cell lines were established from lymph nodes of mice injected in both hind foot pads with MBP87–99 peptide (100–200 μg/mouse) emulsified (1:1, vol/vol) either in 4 mg/ml of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, complete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco), or incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. Ten to twenty days postimmunization, lymph nodes were removed, cultured, and selected in vitro by using the immunizing peptide (5–10 μg/ml) as described (20). Following four to six rounds of antigenic stimulation, and periodically afterwards, the cells were analyzed for their specificity to MBP87–99 peptide in a proliferation assay and for their cytokine secretion by ELISA. Cells were used for experiments, typically 1 week after stimulation.

Proliferation Assay.

For antigenic stimulation, T cells (1–5 × 104) were incubated in round-bottom 96 well plates (Nunc) with their antigen (5–10 μg/ml) and irradiated (3,000 rad) syngeneic spleen cells as APCs (5 × 105).

For NP-induced stimulation, T cells were incubated only with one NP at 10−8 M for 48-hr incubation, pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (1 Ci = 37 GBq), and harvested 12 hr later. Results are expressed as mean ± SD cpm thymidine incorporation for six replicate wells.

Cytokine Determination by ELISA.

Cytokine levels were measured in supernatants removed after 20 hr from cultures set up in parallel (and in the same conditions) to the proliferation assays by a quantitative sandwich ELISA by using pairs of antibodies obtained from PharMingen, according to the manufacturer instructions. Results are expressed in pg/ml as mean ± SD concentration of duplicate culture supernatants, measured in duplicate wells by ELISA.

Cytokine Determination by Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISPOT).

Sterile immobilon 96 wells plates (MultiScreen, Millipore) were coated (overnight, 4°C) with 100 μl of 2 mg/ml purified rat anti-mouse cytokine antibody (PharMingen) in coating buffer, washed four times with sterile double distilled water, and blocked (1 hr, 37°C) with RPMI 1640 medium containing 3% BSA, washed again and seeded with T cells at six dilutions (5 × 10−5, 2.5 × 10−5, 5 × 10−4, 1 × 10−4, 2 × 10−3, and 4 × 10−2 cells/well).

Given NPs (10−8 M in PBS) were then added for overnight incubation (in 5% CO2, 37°C incubator). Control plates were supplemented only with PBS. Supernatants were then discarded, the plates washed (four times for 10 min) with PBS-T (PBS/0.05% Tween), and then exposed to 100 μl of 2 mg/ml (in 10% FCS/PBS) of biotin-conjugated anti-murine cytokine antibody (PharMingen) (overnight, 4°C). The plates were then washed (six times for 10 min) with PBS-T, incubated (30 min at room temperature) with 1:250 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated ExtraAvidin (Sigma), and washed again (eight times for 10 min). One tablet of 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma) was then dissolved in 2.5 ml of dimethylformamide and added to 47.5 ml of 0.2 M acetate buffer. H2O2 (25 μl) was then added, and 100 μl/well of this developing solution was added for 25 min (room temperature). The reaction was stopped by rinsing with running distilled water, and the plates were left up side down up to a complete dry. After 24 hr, spots in all cell dilutions were counted (inverted light binocular microscope, Zeiss) and summed up. The spot counts in parallel nonstimulated control cultures were subtracted from the NP-stimulated assay spot counts (A. Canaan and Y. Reisner, personal communication).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance was analyzed by the Student’s t test.

RESULTS

CGRP Induces Cytokine Secretion from a Th0-Type Anti-MBP87–99 T Cell Line.

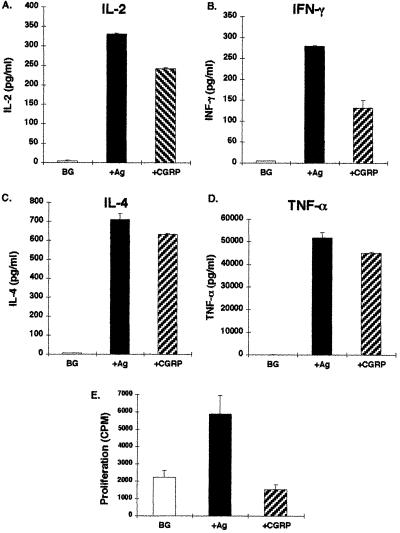

To explore the possibility that a NP can directly induce T cell cytokine secretion, I treated a Th0 anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th0–4) with CGRP at a physiological concentration of 10−8 M (18). Fig. 1 A–D show that CGRP, in the absence of any additional factor, caused the secretion of cytokines at levels comparable in magnitude to those measured upon antigenic stimulation.

Figure 1.

CGRP induces cytokine secretion from Th0-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line, without an effect on cell proliferation. A Th0 anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th0–4) was stimulated either with its antigen (10 μg/ml) and syngeneic APCs, or only with CGRP (10−8 M), and 20 hr postincubation the supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-2 (A), IFN-γ (B), IL-4 (C) and Tnf-α (D) measured by ELISA. Proliferation assays were performed within the same experiment (E). The cytokine results are of one experiment out of two performed and are expressed in pg/ml as mean ± SD concentration of duplicate culture supernatants, measured in duplicate wells in the ELISA plates. Results of control cultures are expressed as background (BG).

CGRP-induced cytokine secretion was not correlated with an increased proliferation of the T cells (Fig. 1E), as with antigenic stimulation.

The effects of CGRP, SOM, Sub P, and NPY on the cytokine secretion of two other Th0 lines (data not shown) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Direct induction of cytokine secretion by NPs

| T-cell line/clone

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Th0 anti-MBP87–99 | Th1, anti-MBP87–99 | Th2

|

|||

| Anti-MBP87–99 | Anti Cop-1 | Anti-Hsp-65 | |||

| SOM | IL-2 | IL-2 | IL-2 | 0 | 0 |

| IFN-γ | 0 | IFN-γ | IFN-γ | IFN-γ | |

| IL-4 | 0 | IL-4 | 0 | ND | |

| IL-10 | 0 | IL-10 | IL-10 | ND | |

| CGRP | IL-2 | 0 | IL-2 | IL-2 | 0 |

| IFN-γ | 0 | IFN-γ | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 0 | IL-4 | ND | 0 | ND | |

| 0 | 0 | IL-10 | IL-10 | ND | |

| NPY | 0 | IL-2 | 0 | IL-2(?) | IL-2 |

| 0 | IFN-γ | IFN-γ | IFN-γ | 0 | |

| 0 | IL-4 | 0 | 0 | ND | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | |

| Sub P | 0 | 0 | 0 | IL-2 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | IFN-γ | IFN-γ | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | |

ND, not done.

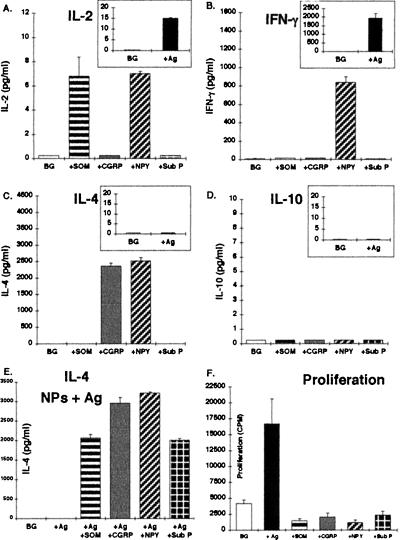

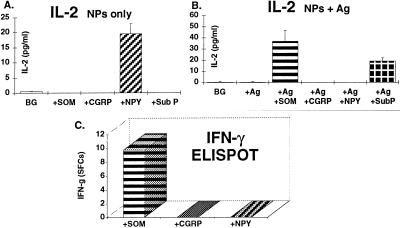

NPs Induce Secretion of Th1 and Th2 Cytokines from a Th1 T Cell Line.

To investigate whether other NPs besides CGRP can directly induce T cell cytokine secretion, and to compare the respective NP- and antigen-induced cytokine release profiles, I used antigen-specific T cell lines already committed to a specific Th1 or Th2 cytokine secretion profile. A Th1-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th1–1) was stimulated either with its antigen and syngeneic APCs or with either one of the following NPs: CGRP, SOM, NPY, and Sub P (10−8 M). As seen in Fig. 2 A–D (Insets), following a classical antigenic-stimulation, this Th1-type T cell line secreted substantial amounts of IFN-γ and low levels of IL-2, but no IL-4 or IL-10, thus confirming its Th1 phenotype.

Figure 2.

Cytokine secretion profile of a Th1-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line, following antigenic and NPs stimulation. A Th1-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th1–1) was stimulated either with its antigen and syngeneic APCs, or with CGRP, SOM, NPY, or Sub P (10−8 M) or simultaneously with both the antigen and APCs and a given NP (E). Following 18 hr incubation, supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-2 (A), IFN-γ (B), IL-4 (C), and IL-10 (D) were measured by ELISA. A proliferation assay was performed in parallel (F).The cytokine results are of one experiment out of two performed and are expressed in pg/ml as mean ± SD concentration of duplicate culture supernatants, measured in duplicate wells in the ELISA plates. The proliferation results are expressed in CPM as mean ± SD of six replicates.

Stimulation with the different NPs indicated that NPY evoked the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2 (Fig. 2 A and B) to ≈50% of the levels of these cytokines induced by antigenic stimulation (Fig. 2 Insets). SOM induced only the release of IL-2, whereas Sub P did not evoke the secretion of any cytokine. However, the most striking phenomenon observed was that both CGRP and NPY induced a substantial release of IL-4 (Fig. 4C), a Th2-type cytokine, not secreted at all upon antigenic stimulation. Furthermore, upon stimulation of these Th1 cells with both the antigen and either one of the NPs, the atypical IL-4 secretion was now induced by all four NPs (Fig. 2E). This observation suggests that whereas CGRP and NPY can induce the atypical secretion of a Th2 cytokine (IL-4) from a resting nonactivated Th1-type T cells, Sub P and SOM can induce such a secretion only from antigen-activated cells. Taken together, these results showed that the NPs studied are able to directly induce the secretion of both typical and atypical cytokines from Th1 T cells. The cytokine secretion induced by the NPs was not accompanied by an effect on T cell proliferation (Fig. 2F).

Figure 4.

Cytokine secretion profile of a Th2-type anti-Cop-1 T cell clone following antigenic and NP-driven stimulation. A Th2-type anti-Cop-1 T cell clone (SS-22–1) was stimulated in parallel with either the antigen (Cop 1) and APCs (A–C, Insets) or with one of the following NPs: SOM, CGRP, NPY, and Sub P (10−8 M). Following 20 hr incubation, supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-2 (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C) were measured by ELISA. The results are of one experiment out of two performed and are expressed in pg/ml as mean ± SD concentration of duplicate culture supernatants, measured in duplicate wells in the ELISA plates.

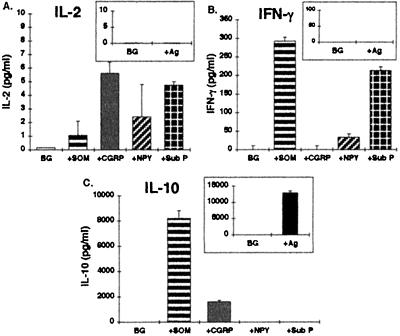

NPs Induce Secretion of Th2 and Th1 Cytokines from a Th2 T Cell Line.

To further investigate the phenomenon of NP-induced cytokine secretion from antigen-specific T cells, I repeated the experiment described above with a Th2-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (termed Mi-BP-Th2–3). Fig. 3 A–D (Insets) shows that upon stimulation with the antigen, this Th2 T cell line secreted the typical cytokines expected: high levels of IL-4 and IL-10, but no IL-2 or IFN-γ. In comparison, direct stimulation with NPs (in the absence of antigen and APCs) showed a very different pattern (Fig. 3 A–D): Although SOM and CGRP could directly induce the secretion respectively of IL-4 and IL-10, which are typical Th2 cytokines, the four NPs induced the secretion of IFN-γ, a Th1-type cytokine that is not secreted upon antigenic stimulation. Following stimulation with SOM and CGRP, minute amounts of atypical IL-2 were also released. Strikingly, though the antigen did not induce any IL-2 secretion, the atypical IL-2 secretion was significantly more pronounced when the Th2 cells were stimulated with both the antigen and some of the NPs (Fig. 3E). This phenomenon was most pronounced with regards to Sub P, which upon incubation with the resting Th1 T cells evoked no IL-2 secretion (Fig. 3A), but when applied together with antigen, which by itself had no atypical effect, evoked a 35-fold increase in IL-2 secretion (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Cytokine secretion profile of a Th2-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line, following antigenic and NPs stimulation. A Th2-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th2–3) was stimulated either with its antigen and syngeneic APCs, or with CGRP, SOM, NPY, or Sub P (10−8 M) or simultaneously with both the antigen and APCs and a given NP. Following 20 hr incubation, supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-2 (A), IFN-γ (B), IL-4 (C), and IL-10 (D) were measured by ELISA. Results of the antigenic stimulation alone are shown in A–D Insets. T cells in the same experiment were stimulated simultaneously with the antigen, syngeneic APCs, and either one of the four NPs, and the levels of all cytokines mentioned above were measured, of which only IL-2 is shown (E). Incubations of T cells with APCs only served as controls (BG). The same T cell line was stimulated with either one of the NPs (10−8 M) and the secretion of all four cytokines, of which only IL-2 (F) and IFN-γ (G) are shown, was detected by ELISPOT. The results are of one experiment out of two performed, and are expressed in SFCs.

The NPs-Induced Secretion of Th1 Cytokines from Th2 Cells Is Detected by an ELISPOT Assay.

To confirm by an additional method the phenomenon of NP-driven atypical cytokine secretion, I further employed the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (21–24). This sensitive and quantitative assay detects cytokine molecules secreted in the vicinity of the cell from which they are derived. Each spot in the read-out represents a “footprint” of the original cytokine-producing cell, and the assay units are therefore termed spot-forming cells (SFCs). I thus analyzed whether IL-2 and IFN-γ SFCs can be detected following treatment of the Th2-type anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Mi-BP-Th2–3) with SOM, CGRP, NPY, or Sub P.

Fig. 3 F and G shows that following a 24-hr-long treatment of these Th2 T cells with NPs, both IL-2 and IFN-γ SFCs were detected, the most prominent being CGRP-induced IL-2, and SOM-induced IFN-γ SFCs.

Taken together, the results show that NPs by themselves can induce the secretion of both typical and atypical cytokines from Th2 T cells, and that such secretion can be detected by both ELISA and ELISPOT.

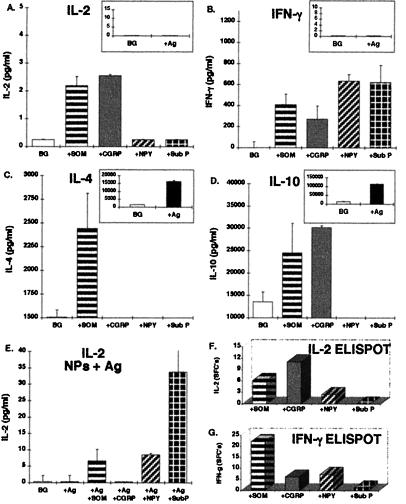

NPs Induce “Forbidden” Secretion of Th1 Cytokines from Th2-Type Anti-Copolymer-1 (Cop-1) T Cell Clone.

I further wished to study whether the phenomenon of NP-induced atypical T cell cytokine secretion is more general, and occurs with other non-MBP-directed antigen-specific T cells. In addition, because T cell lines are likely to be composed of a heterogeneous cell population, I wanted to investigate whether NPs can induce an atypical cytokine secretion from an antigen-specific T cell clone, representing a homogeneous population derived from one single cell. For these two purposes, I employed a mouse CD4+ T cell clone termed S-22-1, directed against the synthetic Cop-1 (20). Upon antigenic stimulation, this Th2-cell clone secretes IL-4 and IL-10, but no IL-2 or IFN-γ, and suppresses EAE in vivo (20). I stimulated these cells in parallel with either the antigen (Cop-1) and APCs, or one of the NPs.

The cytokine secretion following antigenic stimulation was indeed typical of a Th2 phenotype (Fig. 4 A–C, Insets), displaying a very robust secretion of IL-10, but no IL-2 or IFN-γ. Direct stimulation with SOM, and to a lesser extent with CGRP, induced the typical secretion of IL-10, at levels equivalent to around 75% and 15%, respectively, of those secreted upon antigenic stimulation. Furthermore, SOM, Sub P, and to a much lesser extent NPY, induced an atypical IFN-γ secretion at levels comparable to those secreted by the Th0 T cell line (Fig. 1B), but lower than those secreted by the Th1 T cell line (Fig. 2B).

Taken together, the results show that the direct interaction between the NPs and the Th2-type anti-Cop-1 T cells, resulted in a secretion of both typical (IL-10) and atypical (IFN-γ) cytokines.

NPs Induce Atypical Th1 Cytokine Secretion from an Anti-Hsp-65 Th2-Type T Cell Clone.

I next investigated the NP-induced cytokine secretion of an additional T cell clone of a different specificity: a mouse (NOD) anti-human Hsp-65 T cell clone termed C9, previously causing diabetes in NOD recipient mice (19), and at present secreting IL-4 and IL-10, but no IL-2 or IFN-γ (data not shown). I stimulated the C9 clone either with the antigen and APCs or with SOM, CGRP, NPY, or Sub P. The results obtained confirmed that the antigenic stimulation of the C9 clone does not induce the secretion of any Th1-cytokine (data not shown). In contrast, treatment with NPY (in the absence of any additional factor) led to the release of IL-2 (Fig. 5A), at a level comparable to that secreted by the Th1 anti-MBP87–99 T cell line (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the simultaneous stimulation of the C9 clone with the antigen, APCs and either of the NPs, revealed that SOM and Sub P induced an atypical IL-2 secretion (Fig. 5B), although neither the antigenic stimulation alone nor the SOM or Sub P-induced stimulation alone succeeded in evoking such a secretion.

Figure 5.

NP-induced secretion of Th1 cytokines from a Th2-type anti-Hsp-65 clone. Anti-Hsp-65 T cell clone (C9) was stimulated for 20 hr with either SOM, CGRP, NPY, or Sub P (10−8 M) (A) or with the antigen and APCs (B), or simultaneously with the antigen, APCs, and either of the four NPs (B), and the level of IL-2 (A and B) was determined by ELISA. IFN-γ secretion from the same clone, induced by direct stimulation with either of the NPs, was detected by ELISPOT (C).

These results suggest that SOM and Sub P can induce atypical IL-2 secretion from antigen-activated Th2 cells, but not from resting cells.

When the NPs were incubated in control cultures only with the APCs for control, no cytokine secretion was detected (data not shown).

Finally, ELISPOT assays done with the C9 clone showed that SOM induced atypical secretion of IFN-γ (Fig. 5C) not detected by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

Nerve fibers that release NPs are widespread in the mammalian central and peripheral nervous systems, in certain endocrine tissues, and in all the primary and secondary lymphoid organs (11).

The targets of NPs include T cells because the latter express on their surface specific receptors for various neuropeptides such as SOM, CGRP, Sub P, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (12–17).

Combining the presence of peptidergic neurotransmitters at numerous locations where T cells reside or pass through, with the occurrence of their specific receptors on T cells, strongly suggest a functional correlation.

Studies performed in recent years have yielded an increasing body of evidence suggesting that the NPs play a role in regulation of the immune response (25–30, 34). However, not much is known on the direct effects of NPs on T cell function.

In a study aiming to explore whether specific neuropeptides can directly affect T cell function, my colleagues and I have recently found that SOM, CGRP, and NPY directly induce, whereas Sub P fully blocks, integrin-mediated adhesion of T cells to components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). These effects are mediated through specific receptors for these neuropeptides expressed on T cells (18).

In the present study, I examined whether SOM, CGRP, NPY, and Sub P can directly induce T cell cytokine secretion in the absence of any additional factors. The results obtained show that the four NPs tested directly induce the secretion of cytokines from antigen-specific T cell cultures of Th0, Th1, and Th2 subsets. Further conclusions also emerge: (i) NP-induced T cell cytokine secretion is not correlated with increased cell proliferation, as is the case with antigen-driven cytokine secretion; (ii) although some NPs can directly activate resting T cells and drive them to secrete cytokines, others, such as Sub P, induce cytokine secretion mainly from antigen-activated T cells and thus exert an immunomodulatory mode of action (25); (iii) the ability of a specific NP to induce the secretion of a given cytokine can vary from one T cell subset to the other (Table 1), probably as a result of the background secretion of the specific cells and their differentiation history; and (iv) some NPs can drive distinct Th1 and Th2 subsets into an atypical (forbidden) cytokine secretion not observed under classical antigenic stimulation. Thus, certain NPs may induce simultaneously the secretion of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines from either Th2 or Th1 cells.

The NP-induced atypical cytokine secretion raises questions as to the stability of the Th1 and Th2 phenotypes in vivo and as to the legitimacy to rigidly classify T cell populations to either one of these two subsets only according to the profile of in vitro assayed antigen-driven stimulation.

In fact, NP-induced cytokine secretion may now create the need for a new classification.

As to the mechanism by which NPs can drive T cell populations to deviate from their typical cytokine release profiles, one could speculate that such deviation can reflect changes occurring either on a population level or on a single cell level. In favor of the ’population phenomenon’ is the fact that the anti-MBP87–99 T cell lines (unlike the anti-Hsp-65 and anti-COP-1 T cell clones) used in this study are likely to consist of a mixture of antigen-specific T cells that may differ in several parameters including the presence, density, and state of various receptors. It is therefore possible that NPs awake a dormant subpopulation of Th1 cells within a Th2 T cell line (or vice versa), or even stimulate, via NP receptors, silent cells that partially or completely lack a T cell receptor and are therefore refractory to antigenic stimulation (leading to cytokine secretion). However, the fact that the NP-induced atypical cytokine secretion was observed here not only in distinct T cells lines, but also in two T cell clones, lead me to favor the hypothesis that the phenomenon can occur on a single-cell level. Moreover, from the quantitative point of view, the ability of NPs to induce in some cases the secretion of atypical cytokines at levels comparable to those secreted upon antigenic stimulation (Figs. 2C and 4C) suggests that these NPs might be activating more than just a minor dormant fraction of cells within the T cell population.

On the basis of these arguments, I speculate that NPs may have the ability to break the commitment of single Th1 and Th2 cells already engaged in a distinct pattern of cytokine secretion. However, further experiments are needed to elucidate the precise mechanism(s) leading to the NP secretion of atypical cytokines.

Be the mechanism as it may, it is of small relevance (if at all) to the potential outcomes of the NP-induced cytokine secretion. Once released, the atypical cytokines are expected to affect various cells in their vicinity, including the same cells that secreted them (through autocrine regulatory loops) and consequently affect immune function.

When considering the plausible consequences of the NP-induced cytokine secretion, it comes to mind that the CNS and the peripheral organs such as the endocrine and immune organs are interconnected and exchange reciprocal information. In the context of inflammation, for instance, the migration, adhesion, and extravasation of T cells into inflamed sites, as well as the immigration of CD4+ T cells into the CNS, are greatly influenced by cytokines, and the release of some of them could be under the control of NPs.

NP-induced T cell cytokine secretion may also be of particular relevance to autoimmune diseases, in which the functionality and pathogenicity of CD4+ T cells have been correlated with secretion of particular cytokines. Known examples are (i) the human multiple sclerosis and its animal model EAE, both correlating with an increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, and the latter also with a lack of detectable IL-4 and IL-10 (5, 9); (ii) T cell-mediated insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in humans and in NOD mouse, where the development of peri-insulitis, insulitis, and β cell destruction are associated with TNF-β, IFN-γ, and IL-2 (28).

Based on the above, one may speculate that upon encounter with NPs, whether in the periphery or in the CNS, autoimmune Th1 and Th2 T cells can be directly triggered to secrete both typical and atypical cytokines. The NP-induced atypical cytokine secretion may subsequently tilt the fine balance determining whether such autoimmune T cells will lead to disease or rather to its suppression. Moreover, pre-exposure of autoimmune T cells to NPs in vivo, especially in the CNS, could also modulate the outcome of their subsequent encounter with the specific antigen, possibly shifting the balance between pathogenicity, protection, or ineffectiveness. Such an hypothesis could explain why the in vivo destiny of autoimmune T cells cannot be predicted only from their in vitro-determined Th phenotype and why the cytokine profile of the same T cells can differ in the periphery and in the CNS, as recently observed (8).

The NP-mediated secretion of both typical and atypical T cell cytokines may also have a role in T cell differentiation. It is currently believed that the differentiation of pluripotent CD4+ T cells into the Th1 and Th2 phenotype is mainly regulated by the cytokine environment (1, 31). IFN-γ and IL-12 are the major cytokines promoting Th1 phenotype, whereas IL-4 has the greatest influence in driving Th2 differentiation. Interestingly, my results, showing that SOM, CGRP, NPY, and Sub P can all lead to IFN-γ secretion, whereas SOM, CGRP, and to a lesser extent NPY cause IL-4 release, make these NPs good candidates to affect T cell differentiation.

Recent studies have shown that a single population of precursor T cells (Th0) can give rise to both Th1 and Th2 effector cells (1, 32). Accordingly, if one assumes that the process by which some NPs drive Th1 and Th2 cells to secrete atypical cytokines occurs at the single cell level, then such a process can possibly be viewed as a de-differentiating event rather than as a shift from one subset to the other. Thus, the commitment of differentiated T cells to an exclusive Th1 or Th2 subtype would be reversed into a Th0 state because of direct interaction with NPs. Similar conversion to a Th0-like phenotype, was shown recently to be inducible by removing IL-12 from Th1 cells and subsequently treating them with IL-4 plus antigen (making them IL-4 producers), and by removing IL-4 from Th2 cells and treating them with IFN-γ and IL-12 (making them IFN-γ producers) (33). Thus, fixed Th1 or Th2 phenotypes can be reversed in vitro exclusively by the combinatorial effect of at least two specific cytokines in the presence of antigen and APCs.

My results suggest that NPs, through the activation of their specific T cell expressed receptors, can directly induce the same type of phenomenon, probably by neutralizing the transcriptional or translational inhibition of forbidden genes. Such inhibition (or shut off) was reported to occur in the Th0-type uncommitted precursor cells, which transcribe both IL-4 and IFN-γ, during their polarization and differentiation, ending in a commitment to either Th1 or Th2 phenotype (32).

If NPs can indeed induce the de-differentiation of already committed cells, or bias the ongoing differentiation of young pluripotent T cells into one specific T cell subset under in vivo conditions (which has still to be proven), one can speculate that they may serve the immune system as a plasticity tool to adapt its T cell armory to changing conditions or insults. Thus NPs secreted at the command of the nervous system may drive T cells into the secretion of specific sets of cytokines, that would in turn influence the phenotype of further recruited T cells.

Taken together, the results of the present study contribute to a better understanding of the neuro-immune interactions and of the factors that may influence T cell cytokine secretion in vivo, and may thus provide means for possible therapeutic interventions in T cell-mediated dis-regulations and disorders.

Acknowledgments

I thank Prof. L. Steinman for his scientific contribution and financial support. I am also grateful to Drs. R. Aharoni and D. Teitelbaum for the anti-Cop-1 T cell clone, Dr. D. Elias and Prof. I. R. Cohen for the anti-Hsp-65 T cell clone, and Dr. A. Canaan for assistance with the ELISPOT assays.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SOM

somatostatin, CGRP, calcitonin gene-related protein, NP- Y, neuropeptide Y

- Sub P

substance P

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- IL

interleukin

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- NOD

nonobese diabetic

- CNS

central nervous system

- ELISPOT

enzyme-linked immunospot

- SFC

spot-forming cell

- Cop-1

copolymer-1

- Th cell

T helper cell

References

- 1. Constant S L, Bottomly K. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assenmacher M, Schmitz J, Radbruch A. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1097–1101. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seder R A, Prussin C. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:163–166. doi: 10.1159/000237535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palm N, Germann T, Goedert S, Hoehn P, Koelsch S, Rude E, Schmitt E. Immunobiology. 1996;196:475–484. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(97)80064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merrill J E, Benveniste E N. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benveniste E N. Human Cytokines: Their Role in Research and Therapy. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1995. pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoruts A, Miller S D, Jenkins M K. J Immunol. 1995;155:5011–5017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lafaille J J, Keere F V, Hsu A L, Baron J L, Haas W, Raine C S, Tonegawa S. J Exp Med. 1997;186:307–312. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakowski M L, Owens T. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2840–2847. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pakala S V, Kurrer M O, Katz J D. J Exp Med. 1997;186:299–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weihe E, Nohr D, Michel S, Muller S, Zentel H J, Fink T, Krekel J. Int J Neurosci. 1991;59:1–23. doi: 10.3109/00207459108985446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura H, Koike T, Hiruma K, Sato T, Tomioka H, Yoshida S. Immunology. 1987;62:655–658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sreedharan S P, Kodama K T, Peterson K E, Goetzl E J. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:949–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiedermann C J, Sertl K, Pert C B. Blood. 1986;68:1398–1401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payan D G, Goetzl E J. J Immunol. 1985;135:783s–786s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottaway C A, Greenberg G R. J Immunol. 1984;132:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umeda Y, Arisawa M. Neuropeptides. 1989;14:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(89)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levite M, Cahalon L, Hershkovitz R, Steinman L, Lider O. J Immunol. 1998;160:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias D, Reshef T, Birk O S, van der Zee R, Walker M D, Cohen I R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3088–3091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aharoni R, Teitelbaum D, Sela M, Arnon R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10821–10826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taguchi T, McGhee J R, Coffman R L, Beagley K W, Eldridge J H, Takatsu K, Kiyomo H. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bocher W O, Herzog Hauff S, Herr W, Heermann K, Gerken G, Meyer Zum Buschenfelde K H, Lohr H F. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:52–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Hambleton S, Britton W J, Hill A V, McMichael A J. J Exp Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.elGhazali G E, Paulie S, Andersson G, Hansson Y, Holmquist G, Sun J B, Olsson T, Ekre H P, Troye Blomberg M. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2740–2745. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nio D A, Moylan R N, Roche J K. J Immunol. 1993;150:5281–5288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hagen P M, Krenning E P, Kwekkeboom D J, Reubi J C, Anker Lugtenburg P J, Lowenberg B, Lamberts S W. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang F, Millet I, Bottomly K, Vignery A. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21052–21057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khachatryan A, Guerder S, Palluault F, Cote G, Solimena M, Valentijn K, Millet I, Flavell R A, Vignery A. J Immunol. 1997;158:1409–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston J A, Taub D D, Lloyd A R, Conlon K, Oppenheim J J, Kevlin D J. J Immunol. 1994;153:1762–1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calvo C F, Chavanel G, Senik A. J Immunol. 1992;148:3498–3504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seder R A, Paul W E. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura T, Kamogawa Y, Bottomly K, Flavell R A. J Immunol. 1997;158:1085–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura T, Lee R K, Nam S Y, Podack E R, Bottomly K, Flavell R A. J Immunol. 1997;158:2648–2653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor A W, Streilein J W, Cousins S W. J Immunol. 1994;153:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]