Abstract

Cold shock proteins (Csps) are assumed to play a central role in the regulation of gene expression under cold shock conditions. Acting as single-stranded nucleic acid-binding proteins, they trigger the translation process and are therefore involved in the compensation of the influence of low temperatures (cold shock) upon the cell metabolism. However, it is unknown so far how Csps are switched on and off as a function of temperature. The aim of the present study is the study of possible structural changes responsible for this switching process. 1H-15N HSQC spectra recorded at different temperatures and chemical-shift analysis have indicated subtle conformational changes for the cold-shock protein from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima (TmCsp) when the temperature is elevated from 303 K to its physiological temperature (343 K). The three-dimensional structure of TmCsp was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at 343 K to obtain quantitative information concerning these structural changes. By use of residual dipolar couplings, the loss of NOE information at high temperature could be compensated successfully. Most pronounced conformational changes compared with room-temperature conditions are observed for amino acid residues closely neighbored to two characteristic β-bulges and a well-defined loop region of the protein. Because the residues shown to be responsible for the interaction of TmCsp with single-stranded nucleic acids can almost exclusively be found within these regions, nucleic acid-binding activity might be down-regulated with increasing temperature by the described conformational changes.

Keywords: Cold shock protein, NMR, residual dipolar couplings, thermophilic adaptation, RNA binding

The cold-shock response in microorganisms is a transient phenomenon affecting the growth rate of the cell and the saturation of fatty acids as well as the rate of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis at temperatures significantly lower than the normal physiological temperature (Shaw and Ingraham 1976). Whereas the expression under such specific low-temperature conditions is dramatically decreased for most proteins, so-called Cold shock proteins (Csps) show an extremely high-induction level due to the cold shock. Csps play a key role in the regulation of gene expression at low temperatures until physiological temperatures are reached again. Csps share a high similarity with respect to their amino acid sequences (Jones and Inouye 1994; Graumann and Mahariel 1996; Thieringer et al. 1998). Csps are usually folded in a Greek-key-β-barrel, made up of five β-strands, which are arranged into two antiparallel β-sheets. They belong to the OB-fold-family (Murzin 1993). Structures of the major Csps from Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, Csp A and Csp B, as well as Csp B from Bacillus caldolyticus, were determined by X-ray crystallography and/or solution NMR spectroscopy (Schindelin et al. 1993, 1994; Schnuchel et al. 1993; Feng et al. 1998; Newkirk et al. 1999; Mueller et al. 2000). The structural features of Csp A from E. coli revealed putative RNP1 and RNP2 sequence motifs commonly found in ssDNA-binding proteins (Bandziulis et al. 1989). This suggests that Csps possibly have a regulatory role for the adaptation of the organisms to low temperature. Csp A from E. coli was shown to increase the synthesis of several cold stress-inducible proteins after a decrease in temperature. However, different members of the E. coli Csp family are regulated differently. Some appear to perform functions during cell division or during the stationary phase (Murzin 1993) at physiological temperatures. The interaction with single-stranded nucleic acids has been verified by chemical-shift perturbation analysis of CspA/ ssDNA complexes (Newkirk et al. 1999), ssRNA-binding gel-shift assays (Jiang et al. 1996), and site-directed mutagenesis of the ssDNA-binding site of E. coli Csp A (Hillier et al. 1998) and B. subtilis Csp B (Schröder et al. 1995). It is believed that electrostatic, as well as hydrophobic interactions are involved in nucleic acid binding. Nevertheless, the role of these interactions in the cell biology of the cold shock response is still not fully understood (Phadtare et al. 1999).

Csps are small globular proteins consisting of 65 to 70 amino acids. The proteins do not exhibit post-translational modifications or cofactor binding. It was shown that Csps undergo reversible folding/unfolding following a two-state mechanism without slow kinetic phases (Schindler and Schmid 1996). Csps have been identified in a wide variety of microorganisms from psychrophiles to thermophiles. Even among eukaryotic proteins, a domain was found that shows 43% identity with Csp A, the so-called Y-boxdomain (Wistow 1990). From the evolutionary point of view, Csps, therefore, belong to the most conserved proteins presently known. Correspondingly, they have been used as model systems for numerous folding studies and thermodynamic analyses, especially with respect to the molecular mechanisms of thermal stabilization (Frankenberg et al. 1999; Perl and Schmid 2001). The first hyperthermophilic member of the Csp-family, TmCsp, was cloned from Thermotoga maritima (Welker et al. 1999). TmCsp is a small protein of 66 amino acids with a molecular mass of 7474 Da. Its room-temperature structure has already been determined by solution NMR spectroscopy (Kremer et al. 2001). Although TmCsp shows 76% sequence homology (61% identity) to Csp from the mesophilic B. subtilis CspB, its thermal stability (Tm = 361 K) strongly exceeds that of B. subtilis Csp (Tm = 325 K) (Perl et al. 1998). It was suggested (Kremer et al. 2001) that TmCsp gains its high stability compared with its mesophilic and moderately thermophilic analogs from a single peripheral ion cluster around the side chain of Arg 2, as well as increased hydrophobic stacking at the protein surface. This is in agreement with the observation that protein stability seems to be accomplished by the cumulative contributions of very few noncovalent interactions (Matthews 1996). 19F NMR investigations of the thermal unfolding of TmCsp enriched with 5-fluoro-tryptophan revealed a typical two-state folding/unfolding pattern (Schuler et al. 2002). The analysis of the data suggests that the extreme thermal stability of TmCsp is almost exclusively due to a decrease of the unfolding rate constant. Furthermore, it is suggested that entropic factors are important for the thermal stability of this protein. The aim of the present study is the determination of the structure of TmCsp at a temperature close to the bacterium’s optimum physiological temperature and especially its comparison with the structure at 303 K. This comparison should reveal structure–function relationships that are neither provided by the analysis of the room-temperature structure alone nor by a hypothetical structure of a corresponding protein–nucleic acid complex.

Results

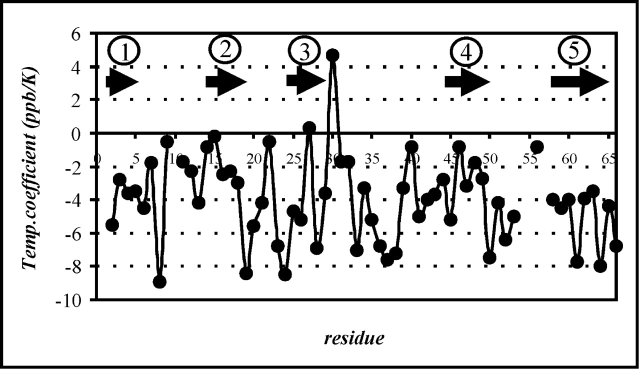

Figure 1 ▶ shows the two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of TmCsp at 328 K. An interesting effect is seen in this figure; many of the 1HN-15N cross-peaks split into at least two signals (e.g., see Gly 3, Lys 4, Glu 33, and His 61) at 328 K, indicating the existence of at least two subtly different conformations of the molecule. Often, the signals due to the different conformations overlap, resulting in asymmetric cross-peaks (e.g., see Lys 19, Val 25, or Leu 40). An analysis of the complete spectrum shows that ~50% of the 1HN-15N cross-peaks are split. At a temperature of 328 K, the average difference between the two signals is 0.03 ppm for 1HN and 0.15 ppm for 15N. This behavior is not restricted to specific secondary structure elements or regions, indicating that the structural changes responsible for this effect are not limited to certain parts of the molecule. The relative intensities of the signals, that is, the population of the different states, depends on the temperature as well. At 343 and 303 K, one of the different conformations clearly dominates.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of TmCsp measured at 328 K. Glutamine side-chain amide correlation peak pairs are interconnected with solid lines and denoted by an asterisk.

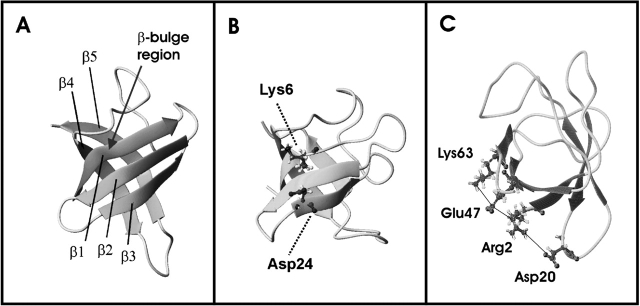

Furthermore, the 1H NMR chemical shifts change with increasing temperature, in most cases, to smaller chemical shift values. This is a well-known phenomenon. Thermal fluctuations cause a decrease of amide proton chemical-shift values due to a higher mobility at elevated temperatures (Baxter and Williamson 1997). The described effect should be most pronounced for residues located within mobile regions of the molecule and less distinct for those in stable areas such as secondary structure elements. Therefore, negative temperature coefficients of variable size are expected, depending on the thermal stability of the individual protein segments. First-order temperature coefficients were determined for the amide proton chemical shifts of TmCsp by linear extrapolation from the chemical shifts at 303, 328, and 343 K. These temperature coefficients are plotted as a function of the amino acid residue number in Figure 2 ▶. The majority of these coefficients is negative, only a few are positive. Values higher than, that is, less negative than −5 ppb/K, indicate amide protons involved in intramolecular hydrogen-bonds (Freund et al. 1995; Rothemund et al. 1996), whereas NH protons with temperature coefficients lower than −5 ppb/K are likely to form a hydrogen bond to water. Values distinctly lower than −5 ppb/K are especially observed for amino acid residues Phe 8 (−8.9 ppb/K), Lys 19 (−8.4 ppb/K), and Asp 24 (−8.5 ppb/K). Furthermore, the average temperature coefficients for the backbone amide protons of β1 (Arg 2–Asp 9) and β5 (Gln 58–Val 65) in their room-temperature extent are −4.6 and −6.2 ppb/K, respectively. These values are clearly lower than for the remaining strands β2, β3, and β4 (e.g., −3.0 ppb/K for β2), indicating that possible temperature-dependent conformational changes are preferentially expected for β1 and β5. Within this context, it is interesting to note that these two β-strands are divided into two segments, β1′ and β1″, as well as β5′ and β5″ by two so-called β-bulges centered at Lys 6 and Ala 60. Temperature coefficients have also been determined for side-chain protons of TmCsp. The chemical-shift changes caused by an increase of temperature from 303 to 343 K turned out to be particularly significant for Hδ and HE of a single aromatic amino acid residue, namely Trp 7. Its HE1-chemical shift changes with a temperature coefficient of −5.5 ppb/K. In contrast, the temperature coefficients for HE1-protons in other aromatic residues (Phe 8, Phe 16, Phe 26, Trp 29, Phe 37, and Phe 48), fall within the range of −1.5 to 0 ppb/K.

Figure 2.

First-order temperature coefficients for the amide-proton chemical shifts of TmCsp determined by linear extrapolation from the chemical shifts measured at temperatures of 303 K, 328 K, and 343 K, respectively. Arrows indicate the extent of β-strands 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, at high temperature. Regular secondary structure elements correlate with first-order temperature coefficients higher than −5 ppb/K, whereas temperature coefficients below −5 ppb/K preferentially occur for amino acid residues located in loop regions.

The described analysis of the temperature dependence of chemical shifts is, however, incapable of delivering reliable quantitative structural information. We therefore decided to determine the three-dimensional structure of TmCsp at 343 K, to gain a more precise insight into the structural features of the protein at the physiological temperature of the hyperthermophilic bacterium. This high-temperature structure is compared with the molecular structure at a lower temperature, that is, under conditions similar to the environment under cold shock. We have also tried to obtain structural information at temperatures up to 353 K, that is, at temperatures close to the melting temperature of TmCsp (361 K). Almost the complete protein backbone could be assigned. However, the decreasing signal-to-noise ratio, especially of the NOESY spectra, prevented us from determining the structure of the protein at 353 K. Note that the absence of NOE information at elevated temperatures does not necessarily indicate a higher flexibility of the molecule. More often, this effect is caused by the onset of rapid amide proton exchange, decreasing spin polarization and increasing electronic noise. It could be shown earlier (Schuler et al. 2002; see above) that TmCsp exhibits a characteristic two-state folding/unfolding pattern. The temperature-dependent conformational changes described here occur well below the melting temperature. Therefore, the NMR structure determined here does not represent a classical folding intermediate.

The secondary structure elements of TmCsp at 343 K were determined using a combination of data, including medium-range interstrand NOEs, 3JHNHα coupling constants as well as deviations of the chemical shifts of backbone nuclei (δ13Cα, δ13C’, δ1Hα) from random-coil values combined with statistical methods and homology search (TALOS; Cornilescu et al. 1999). The results were checked by examining the corresponding Ramachandran plots as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Characteristic interstrand NOEs identified at 343 K show that the global Greek-key topology is conserved at high temperature. Nevertheless, the observation of NOEs is limited to central segments of the β-strands, suggesting a partial melting of the β-sheets at 343 K. This observation is further corroborated by the results derived from TALOS analyses (see Table 1). All five β-strands (β1–β5) observed at 303 K could be identified at 343 K, as well from the characteristic backbone torsion angles Φ and Ψ; however, their length changed. The amino acid residues identified as belonging to these strands at 343 K are given as follows (the extent of the corresponding strands at 303 K is indicated in parenthesis): β1: Gly 3–Val 5 (Arg 2–Asp 9), β2: Tyr 14–Lys 19 (Gly 13–Lys 19), β3: Asp 24–Trp 29 (Asp 24–Trp 29), β4: Gln 44–Ile 50 (Gly 43–Gln 51), β5: Gln 58–Val 64 (Gln 58–Val 65). Note that the extent of the β-strands given here was taken from the finally determined structures and is not completely identical with the TALOS predictions (Table 1). Most amino acid residues originally bordering the β-strands show torsion-angle values that do not allow them to adopt typical planar β-sheet conformation at 343 K. In agreement with the preceding analysis of temperature coefficients, the most pronounced effects can be observed for β1. β1 undergoes a distinct loss of regular secondary structure at high temperature. Its N-terminal part, β1′, is conserved, whereas the original C-terminal part, β1″, starting with Lys 6 appears to be nonstructured at 343 K. It has to be mentioned that the observed loss of secondary structure cannot be ascribed to missing information. Almost all backbone proton chemical shifts could be identified at high temperature, except for residues Ser 10, Gly 36, Lys 38, Glu 52, and Lys 55 localized within loop regions. Furthermore, it should be noted that the reliability of this TALOS analyses is attested by a good agreement between the predicted torsion angle values Φ and the experimentally determined 3JHNHα coupling constants obtained from MOCCA-SIAM spectra.

Table 1.

Dihedral angles Φ and Ψ for amino acid residues in secondary structure elements determined by homology search using the computer program TALOS

| Residue | Φ/° | Ψ/° |

| Arg 2 | −121 | 161 |

| Gly 3 | −124 | 148 |

| Lys 4 | −123 | 136 |

| Val 5 | −91 | 118 |

| Lys 6 | −72 | −39 |

| Trp 7 | −87 | −11 |

| Phe 8 | −82 | 137 |

| Gly 13 | −68 | −25 |

| Tyr 14 | −93 | 2 |

| Gly 15 | 174 | 148 |

| Phe 16 | −135 | 140 |

| Ile 17 | −110 | 113 |

| Thr 18 | −105 | 129 |

| Lys 19 | −83 | 147 |

| Asp 24 | −129 | 138 |

| Val 25 | −107 | 130 |

| Phe 26 | −81 | 121 |

| Val 27 | −109 | 129 |

| Val 45 | 114 | 130 |

| Val 46 | −118 | 151 |

| Glu 47 | −128 | 142 |

| Phe 48 | −128 | 152 |

| Glu 49 | −130 | 147 |

| Ile 50 | −114 | 127 |

| Gln 51 | −101 | 139 |

| Gln 58 | −112 | 116 |

| Ala 59 | −96 | 128 |

| Ala 60 | −90 | −27 |

| His 61 | −98 | −3 |

| Val 62 | −125 | 126 |

| Lys 63 | −105 | 130 |

All residues found by TALOS to be involved in β-strands at 303 K are shown. Gray fields indicate residues found to be located in β-strands at high temperature (343 K).

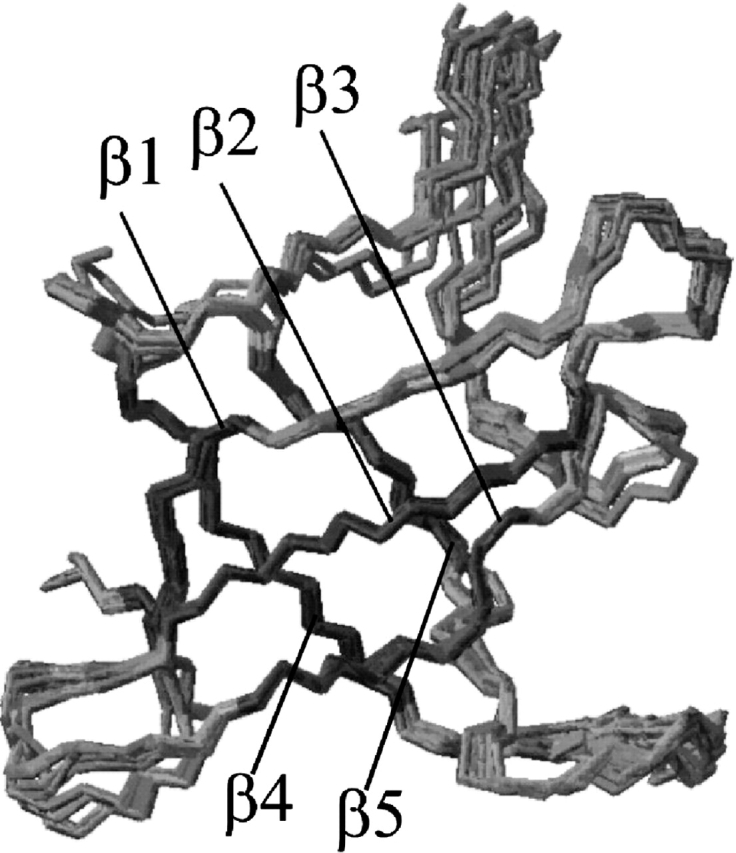

The constraints used in the simulated annealing protocol to calculate the three-dimensional structure of TmCsp at 343 K are summarized in Table 2. Due to the decreasing signal-to-noise ratio at elevated temperatures, 442 NOEs could be identified only at 343 K (for comparison, ca. 800 NOE contacts have been assigned in two-dimensional NOESY spectra at 303 K). Whereas an average number of 14 NOE distance restraints per residue could be used for the refinement of the 303 K structure, only eight NOE distance restraints per residue were available for the determination of the 343 K structure. Nevertheless, the overall solution structure of TmCsp at high temperature is well defined, as demonstrated in Figure 3 ▶, obviously due to the use of residual dipolar couplings that are capable of replacing NOE information to a high extent (Clore et al. 1999). This figure shows a superposition of the backbone atoms of a family of the 10 lowest energy structures generated with the computer program CNS. A backbone-rmsd-value of 0.2 nm could be obtained for the secondary structure elements of the final structural models, taking into account all backbone atoms. To evaluate the quality of the calculated structures, R-factors were determined as described by Gronwald et al. (2000). Values of 0.66 and 0.70 were obtained for the structures calculated with and without residual dipolar couplings, respectively. For the refined structure of TmCsp at 303 K, R-factors of 0.51 and 0.54, respectively, were calculated. This indicates that the structures determined at 303 and 343 K are of comparable quality. The Q-factor defined for residual dipolar couplings by Cornilescu et al. (1998) was 0.27 for the 343 K structure, revealing a good agreement between calculated and experimentally determined residual dipolar couplings. Apart from glycines and residues located in poorly defined and potentially mobile segments, 95% of Φ and ψ values occur in sterically preferred regions of the Ramachandran plot. As usual, longer loop regions, especially that in between β3 and β4, are less well defined. In contrast, the loop between β4 and β5 (amino acid residues Gln 51–Pro 57) is amazingly well defined and exhibits a rmsd value of 0.36 nm only. The latter loop undergoes the most striking backbone conformational change when the temperature is elevated from 303 to 343 K (see also Fig. 4 ▶).

Table 2.

Structural statistics at 343 K

| Restraints | Number |

| NOEs, total | 442 |

| intraresidual (i=j) | 192 |

| sequential (|i−j|=1) | 93 |

| intermediate range (1<|i−j|<5) | 59 |

| long range (|i−j|≥5) | 98 |

| dihedral angle restraints, total | 85 |

| TALOS - angles | 30 |

| Φ - angles | 4 |

| Ψ - angles | 26 |

| Φ - angles from3J-couplings (MOCCA-SIAM) | 25 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 0 |

| 1H-15N residual dipolar couplings | 33 |

| Structural statistics for the five-lowest-energy structures (from 200 calculated structures) | |

| Etotal | 2335 ± 16 kJ/mole |

| ENOE | 928 ± 14 kJ/mole |

| Ebond | 151 ± 5 kJ/mole |

| Eang | 545 ± 14 kJ/mole |

| Emp | 110 ± 3 kJ/mole |

| Evdw | 454 ± 15 kJ/mole |

| Eedih | 40 ± 3 kJ/mole |

| Esani | 107 ± 8 kJ/mole |

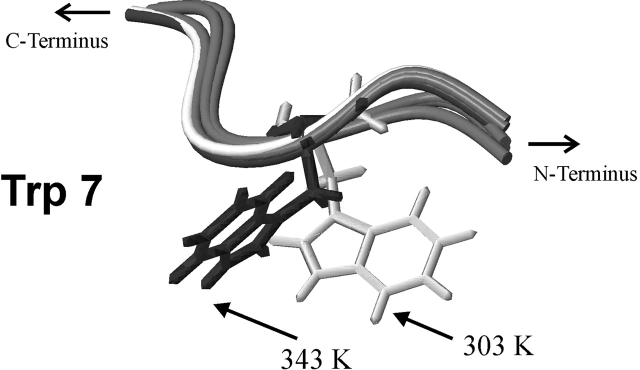

Figure 3.

Superposition of the backbone atoms of a family of the 10 lowest energy structures generated with CNS, overlayed on the mean structure of these 10 structural models. Note the extraordinarily well-defined loop between β-strand 4 and β-strand 5.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the refined backbone structure (ribbon plot) of TmCsp at 303 (A) and 343 K (B,C). The arrow in the 303 K structure points to the β-bulge. In the 343 K structure, the salt bridge Lys 6–Asp 24 (B) and the ion cluster around Arg 2 (C) are indicated. It can be seen that β1 is shortened at elevated temperature; it only consists of residues Gly 3–Val 5 at 343 K, and the second part of β1 at 303 K, residues Lys 6–Asp 9, does not belong to β1 at 343 K. Note the pronounced change of the loop between β4 and β5.

Figure 4 ▶ shows representative TmCsp-structures at 303 and 343 K. In both cases, secondary-structure elements were identified by the algorithm of Kabsch and Sander (1983). Figure 4 ▶ illustrates the above-discussed loss of secondary structure at elevated temperature. A particularly striking shortening is observed for β1. The second part (β1″) of β1 at 303 K, Lys 6–Asp 9, is not recognized to belong to β1 at 343 K. Residue Lys 6 represents the center of a β-bulge that had been found to disrupt β1 into its two parts, β1′ and β1″, at 303 K (Kremer et al. 2001), and seems to act as a breaking point for the secondary structure within the β-strand at high temperature.

Discussion

It could be observed that one of the different TmCsp conformations dominates at 303 and 343 K, whereas comparable populations of the different conformations are found around 328 K. Therefore, we conclude that the protein changes between different conformational states if the temperature is elevated from 303 to 343 K. It can be hypothesized that only the predominant conformer at 303 K (cold shock temperature conditions) shows enough affinity for nucleic acid binding. The conformational changes with increasing temperatures would then reflect a mechanism to down-regulate the protein’s cold shock activity and prevent the bacterium from cold shock-specific gene expression at physiological temperature conditions.

As illustrated in Figures 3 ▶ and 4 ▶, TmCsp is compact and well defined, even at 343 K. Usually, hydrogen bonds are the only noncovalent bonds keeping the three-dimensional structure of mesophilic Csps intact. Additional forces, like ionic interactions, typically contribute to the stability of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Csps (Kremer et al. 2001). In the final high-temperature structures, pronounced shortening of the β-strands is observed, especially close to the β-bulges. This is in line with the fact that the hydrogen-bond energy decreases with the temperature. In contrast, the secondary structure is well conserved close to the peripheral ion cluster around the side chain of residue Arg 2, including the side chains of Asp 20, Arg 2, Glu 47, and Lys 63. This ion cluster has already been found at 303 K, and its existence is now confirmed at high temperature as well. It functions like a bracket, keeping the whole Greek-key motive together, even at high temperature. The side chains of Asp 20, Arg 2, Glu 47, and Lys 63 are closely neighbored in all 343 K structures. This is a prerequisite for the formation of the proposed ionic interactions. The distance from the nitrogen atom of one guanidinium group of Arg 2 to the γ-carbon atom of Asp 20 is 0.53 ± 0.01 nm in the 10 lowest energy structures, the distance from the nitrogen atom of the other guanidinium group of Arg 2 to the δ-carbon atom of Glu 47 amounts to 0.505 ± 0.015 nm, and the distance from the δ-carbon atom of Glu 47 to the ζ-nitrogen atom of Lys 63 is 0.377 ± 0.012 nm. The existence of Arg 2, which dominates the geometry of the ion cluster is, in fact, a unique and crucial feature observed for thermophilic members of the Csp family (Kremer et al. 2001).

Two salt bridges have also been discussed in the room temperature structure, Glu 49–His 61 and Lys 6–Asp 24. They coincide exactly with the centers of the two β-bulge regions, as shown for the salt bridge Lys 6–Asp 24 in Figure 4 ▶. Lys 6 and His 61 located in the β-bulges exhibit backbone angles Φ and Ψ, characteristic for residues in α-helices at 343 K, as well as at 303 K. These findings support the idea that the two salt bridges might represent the driving forces giving rise to the β-bulge formation by preventing the corresponding residues to adopt planar conformations typically found within β-strands. As the influence of interstrand hydrogen bonds on the stability of the protein decreases with increasing temperature (Jaenicke 2000), ionic interactions, particularly the ion cluster and the two salt bridges, are likely to dominate at 343 K, provoking deformations of backbone angles. These deformations are proved by corresponding changes in the torsion angles for some characteristic residues (Trp 7, Phe 8, and Ala 60) at 303 and 343 K.

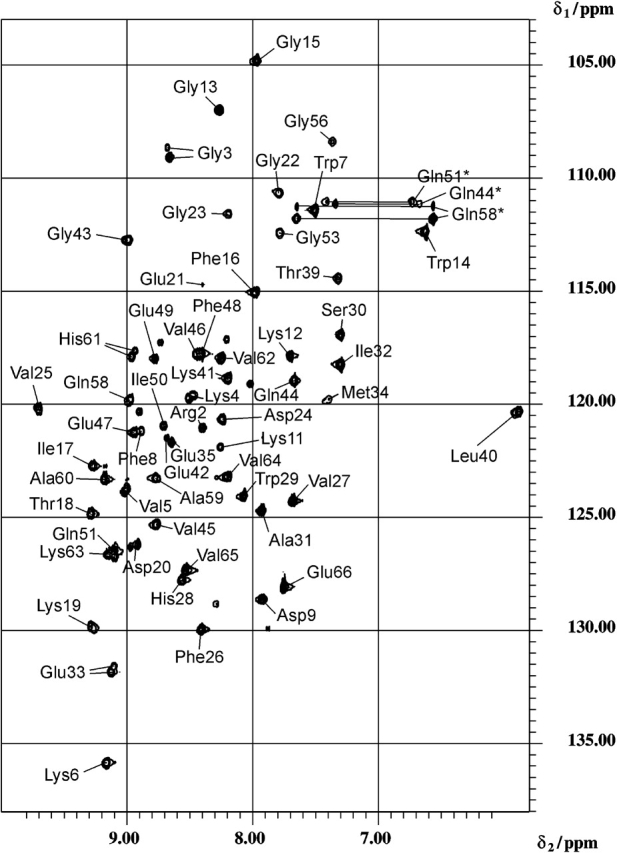

Apart from the conserved RNA-binding motifs RNP1 (Tyr 14, Gly 15, Phe 16, and Ile 17) and RNP2 (Val 25, Phe 26, Val 27, His 28, and Trp 29), it is suggested that especially Lys 6, Trp 7, Lys 12, and Lys 55 are additionally involved into nucleic acid binding (Kremer et al. 2001). This suggestion is in close analogy to the behavior observed for Csp A from E. coli and to the cold shock domain of the human transcription factor YB-1 (Kloks et al. 2002). Titration of the cold shock domain of YB-1 with DNA even suggested stacking of the aromatic ring of Trp 15 (corresponding to Trp 7 in TmCsp) with bases of the nucleic acid. In fact, our analysis of side-chain proton temperature coefficients strongly indicates a special function of Trp 7. Interestingly, Lys 6 and Trp 7 are located in a region of the molecule that is integrated into β1 at 303 K, but does not show regular secondary structure at high temperature. Furthermore, amino acid residue Lys 55 is located within the loop between β4 and β5, which undergoes the most striking backbone conformational change when the temperature is elevated from 303 to 343 K as shown in Figure 4 ▶.

The growth rate of T. maritima clearly decreases at temperatures below 338 K, as reported by Welker et al. (1999). Assuming that the cold shock response correlates with the growth rate, TmCsp is not expressed until the temperature is lower than ca. 338 K. Most amino acid residues necessary for nucleic acid binding (except for Lys 12 and Lys 55) are located in β-strands. It is likely to assume that their side chains are then arranged such that the molecule is capable of binding RNA (active state). Therefore, TmCsp induces other proteins by RNA chaperoning under low-temperature conditions, and allows the organism to be responsive to the new environmental conditions. As the temperature rises, the activity of Csp has to be reduced continuously to prevent misregulation of the protein expression at physiological temperatures. This seems to be accomplished by the influence of ionic interactions, causing torsions of the protein backbone, in particular in β1 and β5, which results in conformational changes of side chains involved into nucleic acid binding as shown for Trp 7 (Fig. 5 ▶). A similar effect could be found for Lys 6 as well. These characteristic conformational changes could be observed in all structures calculated for TmCsp at high temperature. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that Trp 7 is an amino acid residue whose pressure dependence of the 15N chemical shift strongly indicates conformational changes at high temperatures (Arnold 2002). Due to this anomaly, it is speculated that Trp 7 might be of special functional significance. This assumption is in agreement with our analysis of temperature coefficients for characteristic side-chain protons; the lowest first-order temperature coefficient was observed for amino acid residue Trp 7. An interesting hypothesis can be derived from these data. Because at least two basic side chains (Lys 6 and Lys 55) and one hydrophobic side chain (Trp 7) might no longer be available for the interaction at physiological temperature of the bacterium, due to the described conformational changes, the affinity of TmCsp to single-stranded nucleic acids may decrease below a threshold value necessary for sufficiently strong in vivo RNA binding.

Figure 5.

Different conformations of the side chains of residue Trp 7 at 303 and 343 K. These characteristic conformational changes could be observed in all of our structural models calculated for TmCsp at high temperature.

In summary, ionic interactions do not only seem to be the strategy of choice for the thermophilic adaptation of cold shock proteins (ion cluster around Arg 2), there are also indications for a role in temperature-dependent down-regulation. Hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions (ion cluster around the side chain of Arg 2, salt-bridges Lys 6–Asp 24 and Glu 49–His 61) are influenced differently after a temperature raise following the cold shock; whereas hydrogen bonds are weakened due to a faster chemical exchange (loss of secondary structure), ionic interactions obviously resist the increase of temperature. Therefore, the overall fold is conserved especially close to the ion cluster. However, subtle conformational changes affecting the orientation of side chains of residues involved in nucleic acid binding occur, which are assumed to convert the molecule from its active state into the inactive state. Although other or additional regulatory mechanisms cannot be excluded, the proposed temperature-dependent protein inactivation would prevent the bacterium from cold-shock-specific gene expression under physiological conditions in a very elegant and direct way; signal (temperature) sensing and RNA chaperoning are combined in one single molecule.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

TmCsp was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) as described by Welker et al. (1999) and purified according to the procedure established by Wassenberg et al. (1999). For the expression of the 15N and 15N/13C isotope-enriched protein, the procedure established by Kremer et al. (2001) was used. NMR samples contained 1.5 mM protein, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, and 100 mM NaCl.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on Bruker DMX-500 and Bruker DRX-600 spectrometers. 1H-1H 2D-NOESY spectra (mixing time, 250 msec) and 1H-1H 2D TOCSY spectra (isotropic mixing time, 55 msec) were recorded at 343 K and 600 MHz. Proton resonances of the side chains could be assigned from the two-dimensional TOCSY and the HCCH-TOCSY spectrum in 2H2O measured at 343 K. Chemical shifts of nuclei other than 1H were determined on the basis of HSQC, HNCO, and HNCA spectra recorded at 343 K. The latter spectrum also served to check the sequence-specific resonance assignment. HN-Hα-couplings were determined with an accuracy of ± 0.2 Hz from two-dimensional MOCCA-XY16-SIAM spectra (Prasch et al. 1998) recorded at 343 K by Titman-Keeler-fit using an automated computer program (Möglich et al. 2002). For all of the thus-determined couplings, it was possible to limit the Karplus curve to a certain segment by taking into account the information provided by secondary structure prediction algorithms (Cornilescu et al. 1999). The resulting dihedral Φ angles were used directly for structure calculation. Distance restraints were obtained from homonuclear two-dimensional NOESY spectra with a 250-msec mixing time in 1H2O and 2H2O. About 20% of the NOEs were finally identified by automated knowledge-based NOE assignment using a Bayesian Algorithm (Gronwald et al. 2002). The NOE evaluation was iteratively refined by NOE back calculation on the basis of the complete relaxation matrix formalism (Görler and Kalbitzer 1997). The correlation time of reorientation for TmCsp amounts to 1.42 nsec at 343 K in contrast to 4.25 nsec at 303 K. Ψ and additional Φ angle information was obtained by chemical-shift analysis (15N, 1HN, 1Hα, 13Cα, and 13C’) combined with statistical methods and homology search using the program TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999). The 1H NMR chemical shifts were referenced relative to DSS used as an internal reference. The 15N and 13C chemical shifts were indirectly referenced (Wishart et al. 1995). For exact determination of the experimental temperature, a calibration was performed using ethylene glycol (Raiford et al. 1979). Spectra analysis, peak picking, volume integration, as well as relaxation matrix back calculation were performed using the program AUREMOL (Ganslmeier 2002).

Residual dipolar couplings

A prerequisite for the measurement of residual dipolar coupling is the partial alignment of the protein molecules leading to an incomplete averaging of the magnetic dipole–dipole interaction. As shown by Losonczi and Prestegard (1998) mixtures of DMPC and DHPC are highly temperature stable if CTAB is added. The magnetically orienting bicellar solutions were prepared following the procedure described by Losonczi and Prestegard (1998) (molar ratio DMPC : DHPC : CTAB = 3 : 1 : 0.2). Residual 1HN-15N dipolar couplings were measured as the difference of the corresponding couplings measured in oriented (10% w/v DMPC/DHPC/CTAB, 1.5 mM 15N-TmCsp) and isotropic solution (1.5 mM 15N-TmCsp) using 1H-coupled HSQC experiments. A total of 57 residual dipolar 1HN-15N residual dipolar couplings could be measured. The magnitude of the axial (1.85 Hz) and rhombic (0.37 Hz) component of the alignment tensor were determined by examining the distribution of the experimental dipolar couplings.

Structure calculation

Structures were calculated by simulated annealing (Nilges et al. 1988) using the computer program CNS (Brünger et al. 1998). About 550 conformational NMR constraints were taken into account (Table 2). Approximate interproton distances were calculated from the intensities of the NOE cross-peaks in two-dimensional 1H-1H NOESY spectra with an upper bound for distance restraints set to 0.5 nm. The minimum sum of the van der Waals radii (0.18 nm) was used as the lower bound for distance restraints. The initial structure was energy minimized with 1000 cycles of Powell minimization. High-temperature dynamics was run for 30 psec at an initial temperature of 1000 K. The system was then cooled down slowly to a temperature of 100 K in steps of 25 K. At 100 K, a second stage of Powell minimization was performed to receive the final low-energy structure. Figures were generated using the computer program MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996).

Structure quality

Apart from the rmsd, other criteria have also been used to evaluate the quality of the determined structures. The computer program RFAC (Gronwald et al. 2000) provided automated estimation of residual indices (R-factors) for the calculated structures using a Bayesian analysis of the data. Furthermore, Q-factors have been calculated according to Cornilescu et al. (1998), which are a measure for the agreement between the experimental residual dipolar couplings and the residual dipolar couplings calculated from the determined three-dimensional structure. Q-factors lower than 0.3 are indicative for structures of sufficient quality (Cornilescu et al. 1998). Residual dipolar couplings were included in the CNS protocol to optimize the obtained structure by an iterative process of using further coupling data and subsequent structure calculation and determination of the corresponding R-value. Residual dipolar couplings were only taken into account for residues localized within regular secondary structure elements in those structures that had been determined without any orientation data. To check the stereochemical quality of the structures, Ramachandran plots (Ramachandran et al. 1963) were generated by the computer programs MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996) and PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1996). These diagrams also served to confirm the secondary structure elements determined by the algorithm of Kabsch and Sander (1983).

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Dr. Rainer Jaenicke (Frankfurt/M.) and Dr. Ben Schuler (University of Potsdam) for helpful and stimulating discussions. We also thank Ms. Ingrid Cuno for carefully proofreading the manuscript. Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (projects Br 1278/9-1, Kr 1407/4-1, and SFB 521 “Modellhafte Leistungen niederer Eukaryonten”) is gratefully acknowledged.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

COSY, correlation spectroscopy

NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect

NOESY, nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

TOCSY, total correlation spectroscopy

HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum coherence

DSS, Sodium-2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate

MOCCA, modified phase-cycled Carr-Purcell

SIAM, simultaneous acquisition of in-phase and anti-phase multiplets

rmsd, root mean square deviation

ssDNA, single-stranded DNA

Csp, cold shock protein

Tm, Thermotoga maritima

TmCsp, cold shock protein from Thermotoga maritima

Tm, melting temperature

ppb, parts per billion

ppm, parts per million

Φ, Ψ, backbone torsion angles

DMPC, DiMyristoyl Phosphatidyl Choline

DHPC, DiHexanoyl Phosphatidyl Choline

CTAB, hexadecyl (Cetyl) Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide

CNS, crystallography and NMR system

RNP, RiboNucleoProtein

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03281604.

References

- Arnold, M.R. 2002. “High-pressure NMR.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Regensburg, Germany.

- Bandziulis, R.J., Swanson, M.S., and Dreyfuss, G. 1989. RNA-binding proteins as developmental regulators. Genes & Dev. 3 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, N.J. and Williamson, M.P. 1997. Temperature dependence of 1H chemical shifts in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 9 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse- Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system (CNS): A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.M., Starich, M.R., Bewley, C.A., Cai, M., and Kuszewski, J. 1999. Impact of residual dipolar couplings on the accuracy of NMR structures determined from a minimal number of NOE restraints. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 6513–6514. [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, G., Marquardt, J.L., Ottiger, M., and Bax, A. 1998. Validation of protein structure from anisotropic carbonyl chemical shifts in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 6836–6837. [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, G., Delaglio, F., and Bax, A. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, W., Tejero, R., Zimmerman, D.E., Inouye, M., and Montelione, G.T. 1998. Solution NMR structure and backbone dynamics of the major cold shock protein (Csp A) from E. coli: Evidence for conformational dynamics in the single stranded RNA-binding site. Biochemistry 37 10881–10896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg, N., Welker, C., and Jaenicke, R. 1999. Does the elimination of ion pairs affect the thermal stability of cold shock protein from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima? FEBS Lett. 454 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund, J., Vértesy, L., Koller, K.-P., Wolber, W., Heintz, D., and Kalbitzer, H.R. 1995. Complete 1H nuclear magnetic resonance assignments and structural characterization of a fusion protein of the α-amylase inhibitor tendamistat with the activation domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 250 672–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganslmeier, B. 2002. “A software project concerning the automated analysis of multidimensional NMR spectra.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Regensburg, Germany.

- Görler, A. and Kalbitzer, H.R. 1997. Relax, a flexible program for the back calculation of NOESY spectra based on complete-relaxation-matrix formalism. J. Magn. Reson. 124 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann, P. and Mahariel, M.A. 1996. Some like it cold: Response of microorganisms to cold shock. Arch. Microbiol. 166 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwald, W., Kirchhöfer, R., Görler, A., Kremer, W., Ganselmeier, B., Neidig, K.P., and Kalbitzer, H.R. 2000. RFAC, a program for automated NMR R-factor estimation. J. Biomol. NMR 17 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwald, W., Moussa, S., Elsner, R., Jung, A., Ganselmeier, B., Trenner, J., Kremer, W., Neidig, K.P., and Kalbitzer, H.R. 2002. Automated assignment of NOESY NMR spectra using a knowledge based method (KNOWNOE). J. Biomol. NMR 23 271–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.J., Rodriguez, H.M., and Gregoret, L.M. 1998. Coupling protein stability and protein function in E. coli Csp A. Folding 3 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke, R. 2000. Stability and stabilization of globular proteins in solution. J. Biotechnol. 79 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W., Fang, L., and Inouye, M. 1996. The role at the 5′-end untranslated region of the mRNA for Csp A, the major cold shock protein of E. coli, in cold shock adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 178 4919–4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.G. and Inouye, M. 1994. The cold shock response: A hot topic. Mol. Microbiol. 11 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W. and Sander, C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloks, C.P.A.M., Spronk, C.A.E.M., Lasonder, E., Hoffmann, A., Vuister, A.W., Grzesiek, S, and Hilbers, C. 2002. The solution structure and DNA-binding properties of the cold shock domain of the human Y-box protein YB-1. J. Mol. Biol. 316 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL. A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graphics 14 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer, W., Schuler, B., Harrieder, S., Geyer, M., Gronwald, W., Welker, C., Jaenicke, R., and Kalbitzer, H.R. 2001. Solution NMR structure or the cold shock protein from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Eur. J. Biochem. 268 2527–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., Rullmann, J.A., MacArthur, M.W., Kaptein, R., and Thornton, J.M. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losonczi, J.A. and Prestegard, J.H. 1998. Improved dilute bicelle solution for high-resolution NMR of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 12 447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B.W. 1996. Structural and genetic analysis of the folding and function of T4 lysozyme. FASEB J. 10 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möglich, A., Wenzler, M., Kramer, F., Glaser, S.J., and Brunner, E. 2002. Determination of residual dipolar couplings in homonuclear MOCCA-SIAM experiments. J. Biomol. NMR 23 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, U., Perl, D., Schmid, F.X., and Heinemann, U. 2000. Thermal stability and atomic-resolution crystal structure of the Bacillus caldolyticus cold shock protein. J. Mol. Biol. 297 975–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin, A.G. 1993. OB (Oligonucleotide/Oligosaccharide binding)-fold: Common structural and functional solutions for non-homologues sequences. EMBO J. 12 861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newkirk, K., Feng, W., Jiang, W., Tejero, R., Emerson, S.D., Inouye, M., and Montelione, G.T. 1999. Solution NMR structure of the major cold shock protein (Csp A) from E. coli: Identification of a binding epitope for DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91 5114–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges, M., Gronenborn, A.M., Brünger, A.T., and Clore, G.M. 1988. Determination of three-dimensional structures of proteins by simulated annealing with inter-proton distance restraints: Application to crambin, potatoe carboxypeptidase inhibitor and barley serine proteinase inhibitor 2. Protein Eng. 2 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl, D. and Schmid, F.X. 2001. Electrostatic stabilization of a thermophilic cold shock protein. J. Mol. Biol. 313 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl, D., Welker, C., Schindler, T., Schröder, K., Mahariel, M.A., Jaenicke, R., and Schmid, F.X. 1998. Conservation of rapid two-state folding in mesophilic, thermophilic and hyperthermophilic cold shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadtare, S., Alsina, J., and Inouye, M. 1999. Cold shock response and cold shock proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasch, T., Gröschke, P., and Glaser, S.J. 1998. SIAM, a novel NMR experiment for the determination of homonuclear coupling constants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37 802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiford, D.S., Fisk, L.F., and Becker, E.D. 1979. Calibration of methanol and ethylene glycol nuclear magnetic resonance thermometers. Analyt. Chem. 51 2050–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, G.N., Ramakrishnan, C., and Sasisekharan, V. 1963. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 7 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothemund, S., Weiβhoff, N., Beyermann, M., Krause, E., Bienert, M., Mügge, C., Sykes, B.D., and Sönnichsen, F.D. 1996. Temperature coefficients of amide proton NMR resonance frequencies in trifluoroethanol: A monitor of intramolecular hydrogen bonds in helical peptides. J. Biomol. NMR 8 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, H., Mahariel, M.A., and Heinemann, U. 1993. Universal nucleic acid-binding domain revealed by crystal structure of the B. subtilis major cold shock protein. Nature (London) 364 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, H., Jiang, W., Inouye, M., and Heinemann, U. 1994. Crystal structure of CspA, the major cold shock protein of E. coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91 5119–5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, T. and Schmid, F.X. 1996. Thermodynamic properties of an extremely rapid protein folding reaction. Biochemistry 35 16833–16842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnuchel, A., Wiltschek, R., Czisch, M., Herller, M., Willimsky, G., Graumann, P., Mahariel, M.A., and Holak, T.A. 1993. Structure in solution of the major cold shock protein from B. subtilis. Nature 364 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, K., Graumann, P., Schnuchel, A., Holak, T.A., and Mahariel, M.A. 1995. Mutational analysis of the putative nucleic acid-binding surface of the cold shock domain, CspB, revealed an essential role of aromatic and basic residues in binding of single-stranded DNA containing the Y-box motif. Mol. Microbiol. 16 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, B., Kremer, W., Kalbitzer, H.R., and Jaenicke, R. 2002. Role of entropy in protein thermostability: Folding kinetics of a hyperthermophilic cold schock protein at high temperatures using 19F-NMR. Biochemistry 41 11670–11680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M.K. and Ingraham, J.L. 1976. Synthesis of macromolecules by E. coli near the minimal temperature of growth. J. Bacteriol. 94 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer, H.A., Joes, P.G., and Inouye, M. 1998. Cold shock and adaptation. BioEssays 20 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg, D., Welker, C., and Jaenicke, R. 1999. Thermodynamics of the unfolding of the cold shock protein from Thermotoga maritima. J. Mol. Biol. 289 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker, C., Böhm, G., Schurig, H., and Jaenicke, R. 1999. Cloning, overexpression, and physicochemical characterization of a cold shock protein homolog from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Protein Sci. 8 394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.S., Bigam, C.G., Yao, J., Abildgaard, F., Dyson, H.J., Oldfield, E., Markley, J.L., and Sykes, B.D. 1995. 1H, 13C, 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 6 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wistow, G. 1990. Cold shock and DNA binding. Nature 344 823–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]