Abstract

Animal toxins block voltage-dependent potassium channels (Kv) either by occluding the conduction pore (pore blockers) or by modifying the channel gating properties (gating modifiers). Gating modifiers of Kv channels bind to four equivalent extracellular sites near the S3 and S4 segments, close to the voltage sensor. Phrixotoxins are gating modifiers that bind preferentially to the closed state of the channel and fold into the Inhibitory Cystine Knot structural motif. We have solved the solution structure of Phrixotoxin 1, a gating modifier of Kv4 potassium channels. Analysis of the molecular surface and the electrostatic anisotropy of Phrixotoxin 1 and of other toxins acting on voltage-dependent potassium channels allowed us to propose a toxin interacting surface that encompasses both the surface from which the dipole moment emerges and a neighboring hydrophobic surface rich in aromatic residues.

Keywords: Phrixotoxin 1, NMR, spider toxin, structure determination, potassium channel gating modifier

Spider venoms are complex mixtures of toxic peptides, proteins, and low-molecular-mass organic molecules (Escoubas et al. 2000b). Their pharmacological properties are due to the interaction of the venom components with cellular receptors, particularly with ion channels, leading to cellular dysfunction. Spider venoms have proven to be a rich source of highly specific peptide ligands for selected subtypes of potassium, sodium, and calcium channels. The discovery in the venom of the spider Grammostola spatulata (Araneae: Theraphosidae = tarantulas) of the hanatoxins, the first toxins acting on the Kv2.1 voltage-dependent potassium channels (Swartz and MacKinnon 1995) first indicated the potential of spider venoms as a source of potassium channel modulators. Hanatoxins are peptides of 35 amino acids cross-linked by three-disulfide bridges and act in a voltage-dependent manner by modifying the gating properties of Kv2.1 and to some extent of Kv4.2 potassium channels. They were proposed to bind to four equivalent extracellular channel sites near the S3 and S4 segments, close to the voltage sensor (Swartz and MacKinnon 1997a,b; Li-Smerin and Swartz 2000), thus affecting transmembrane movement of the voltage-sensing domain in response to depolarizing voltages. The first described toxin blockers of Kv4 channels were the heteropodatoxins isolated from the venom of Heteropoda venatoria (Araneae: Sparassidae; Sanguinetti et al. 1997), followed by discovery of the phrixotoxins in the venom of Phrixotrichus auratus (Theraphosidae; Diochot et al. 1999). Electrophysiological studies showed that the phrixotoxins block Kv4 channels via a mechanism similar to that of hanatoxins on Kv2 channels, as they bind preferentially to the closed state of the channel, in a voltage-dependent manner (Diochot et al. 1999). The phrixotoxins have been crucial tools to demonstrate that Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channels underlie the transient K+ current Ito1 in cardiac cells and to analyze the contribution of that current in cardiac electrogenesis (Diochot et al. 1999). In contrast to scorpion toxins, which act by pore occlusion, a number of spider toxins appear to bind to sites outside the pore and to act as gating modifiers (Escoubas et al. 2000b). Potassium channel toxins as well as a number of other spider peptides that bind to calcium or sodium ion channels present the same structural organization. They fold into an inhibitor cystine knot motif (ICK), which consists of a compact disulfide-bonded hydrophobic core from which only some short loops emerge (Norton and Pallaghy 1998). In this report, we present the solution structure of Phrixotrichus auratus toxin 1 (PaTx1), determined by two-dimensional 1H NMR, in order to obtain insights into the structure–activity relationship for this family of potassium channel inhibitors.

Results and Discussion

Peptide synthesis

Peptide synthesis, deprotection, and purification proceeded without significant problems and a total of 4.6 mg of pure linear peptide was obtained and submitted to refolding. Re-folding monitored by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of fractions showed fast disappearance of the linear peptide (<2 h) but a slow conversion to the correctly folded toxin at 4°C over 72 h (Fig. 1 ▶). The progressive appearance of the final product was accompanied by the presence of a number of rapidly formed intermediates of undefined structure, which appeared to quantitatively decrease as the toxin folded properly. Over the course of 72 h, most of the linear peptide folded into its expected conformation, and the refolding reaction was terminated as conversion of the remaining intermediate forms appeared to become extremely slow. Final purification yielded more than 3 mg of synthetic PaTx1. Coelution experiments, mass spectrometry, and activity assays on heterologously expressed Kv4 channels demonstrated complete identity with the native toxin isolated from spider venom (data not shown). Refolding of ICK peptides has often been problematic in our hands (P. Escoubas, unpubl.) and as reported by others (DeLa Cruz et al. 2003) yielding very low amounts of correctly folded toxins. Various methods have been used to modify or supplement the refolding buffer composition to increase yields (Kubo et al. 1996; DeLa Cruz et al. 2003). We have found in the case of PaTx1 that refolding at 4°C permitted the conversion of folding intermediates into the final product with good efficiency, and in this case at least, refolding proceeded well with a good yield. When compared to other ICK peptides of different structure, this might be linked to the shorter length of PaTx1 or the reduced flexibility of its intercysteine loops.

Figure 1.

RP-HPLC analysis of the refolding of PaTx1. Traces obtained at different times are superimposed and offset for clarity. Timescale for trace 1 (t = 0). (Black triangle) The linear reduced form of PaTx1.

NMR resonance assignment and secondary structure

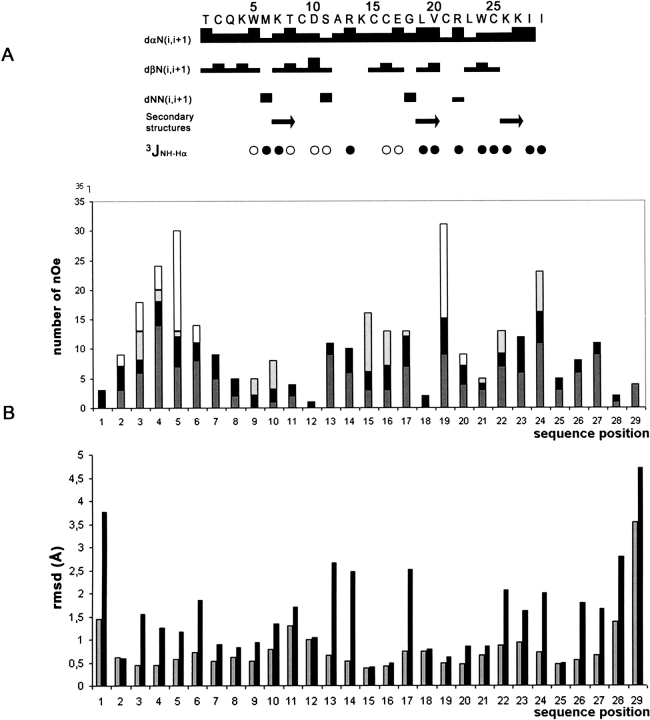

The spin systems were identified on the basis of both COSY and TOCSY spectra. Once the sequential assignment procedure was achieved, almost all protons were identified and their resonance frequencies determined (Table 1). The repartition of the Hαi/HNi+1, Hβi/HNi+1, and HNi/HNi+1 correlations indicates that the toxin is organized in loops, beside three short extended regions characterized by strong Hαi/HNi+1 correlations together with large coupling constants (Fig. 2A ▶).

Table 1.

Resonance assignments of PaTx1 at 290 K

| Residue | HN | Hα | Hβ | Other |

| Y1 | a | 4.21 | 3.09,a | |

| C2 | 8.01 | 4.92 | 2.74, 3.01 | |

| Q3 | 9.02 | 4.35 | 2.02, 2.17 | Hγ 1.91, 260; Hɛ2 8.66, 7.13 |

| K4 | 5.01 | 3.49 | −0.61, 1.26 | Hγ 0.22, 0.53; Hɛ 2.66; Hζ 7.34 |

| W5 | 7.86 | 3.98 | 2.88, 2.99 | Hδ1 7.42; Hɛ1 10.67 |

| M6 | 9.22 | 3.80 | 1.60, 1.92 | Hγ 0.43, 1.25 |

| W7 | 8.61 | 4.89 | 3.30, 3.46 | Hδ1 6.92; Hɛ3 7.59, Hζ2 7.45; Hζ3 7.18; Hɛ1 10.10 |

| T8 | 8.46 | 4.360 | 4.15 | Hγ2 1.14 |

| C9 | 7.69 | 5.01 | 3.22,a | |

| D10 | 8.54 | 4.26 | 3.03,a | |

| S11 | 8.34 | 3.92 | 3.76,a | |

| A12 | 8.02 | 4.34 | 1.30 | |

| R13 | 7.90 | 4.38 | 1.23, 1.66 | Hγ 1.45 Hδ 2.88, 3.05; Hɛ 6.86 |

| K14 | 7.85 | 4.20 | 1.309,a | Hγ 1.75 Hδ 1.59 Hɛ 3.16, Hζ 7.41 |

| C15 | 9.01 | 4.84 | 2.36, 3.03 | |

| C16 | 8.98 | 4.36 | 2.32, 3.22 | |

| E17 | 8.17 | 3.93 | 1.87, 1.81 | Hγ2 2.24 |

| G18 | 8.80 | 3.47, 4.04 | ||

| L19 | 7.34 | 5.09 | 1.07, 1.97 | Hγ 1.184; Hδ 0.57, 0.66 |

| V20 | 9.30 | 4.36 | 1.70 | Hγ 0.67, 0.70 |

| C21 | 8.88 | 4.55 | 2.66, 3.20 | |

| R22 | 8.19 | 4.36 | 1.52, 1.40 | Hγ 1.29, 3.10; Hδ 2.92, 3.10; Hɛ 7.08 |

| L23 | 7.91 | 3.608 | 1.01, 2.11 | Hγ 1.37; Hδ 0.66 |

| W24 | 7.96 | 5.12 | 2.56, 2.86 | Hγ1 6.90; Hɛ3 7.36; Hη2 7.01; Hζ2 7.34; Hζ3 7.02; Hɛ1 10.16 |

| C25 | 8.69 | 4.74 | 2.68, 333 | |

| K26 | 9.40 | 4.81 | 1.57,a | Hγ 1.26, 1.40; Hδ 1.83 Hɛ 2.60 Hζ 7.45 |

| K27 | 8.25 | 4.19 | 1.32, 1.54 | Hγ 0.82, 1.10; Hδ 0.97, 2.03; Hɛ 2.23 Hζ 6.85 |

| I28 | 7.84 | 3.80 | 1.69 | HγI 0.99, 1.39; Hγ2 0.81 Hδ1 0.58 |

| 129 | 8.04 | 3.98 | 1.64 | Hγ1 1.24, 1.49; Hγ2 0.92 Hδ1 0.71 |

a Resonances that cannot be observed.

Nomenclature is in accordance with IUPAC recommendations (Markley et al. 1998).

Figure 2.

(A) Sequence of PaTx1 and sequential assignments. Collected sequential nOe are classified into strong, medium, and weak nOe, and are indicated by thick, medium, and thin lines, respectively. (Arrow) The secondary elements (extended regions); (filled circles) 3JHN-Hα coupling constants ≥ 8 Hz; (open circles) 3JHN-Hα coupling constants ≤ 6 Hz. (B) nOe (top) and RMSD (bottom) distribution vs. sequence of PaTx1. Intraresidue nOe are in dark gray; sequential nOe, in black; medium nOe, in light gray; and long-range nOe, in white. RMSD values for backbone and all heavy atoms are in gray and in black, respectively.

Structure calculation

The structure of PaTx1 was determined by using 318 nOe-based distance restraints, including 139 intraresidue restraints, 85 sequential restraints, 45 medium-range restraints, and 49 long-range restraints. The repartition of these nOe along the sequence is shown in Figure 2B ▶. In addition, 18 hydrogen bond restraints derived from proton exchange and 13 dihedral angle restraints derived from the measurement of coupling constants were included, as well as 9 distance restraints derived from the three disulfide bridges that were assigned by homology with related spider toxins (Escoubas et al. 2000b). Altogether, the final experimental set corresponded to 12.3 constraints per residue on average.

The distance geometry calculation using the whole set of restraints and energy minimization led to a single family of 25 structures (Fig. 3A,B ▶) and the structural statistics are given in Table 2. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) calculated on the whole structure is 1.05 ± 0.29 Å for the backbone and 2.10 ± 0.34 Å for all heavy atoms. If residues 2–28 only are taken into account, these values become 0.71 ± 0.18 Å and 1.68 ± 0.28 Å, respectively, which indicates a poor resolution of N- and C-terminal residues. This is confirmed by the individual RMSD values (Fig. 2B ▶). This low resolution, in particular for the C-terminal part of the toxin is experimentally due to the absence of structural restraints and can be explained by the high mobility of these residues in solution (Fig. 3A ▶).

Figure 3.

(A) Stereopair view of the best fit of 25 solution structures of PaTx1; the backbones of the molecules are represented. (B) MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis 1991) representation. The cystines and N and C termini are labeled. (C) Stick representation of residues Lys 4 and Trp 7. The residue Lys 4 is located in the neighborhood of Trp 7 and its amide proton, placed in the ring current of this tryptophan, has an unusual chemical shift.

Table 2.

Structural statistics of the 25 best structures of PaTx1 obtained by distance geometry and minimization

| RMSD (Å) | Residues 1–29 | Residues 2–28 |

| Backbone | 1.05 | 0.71 |

| All heavy atoms | 2.10 | 1.68 |

| Energies (kcal/mole) | ||

| Total | 40.40 | |

| Bonds | 1.38 | |

| Angles | 22.94 | |

| Impropers | 2.48 | |

| Van Der Waals (repel) | 6.73 | |

| nOe | 6.59 | |

| Cdih | 0.28 | |

| RMSD | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0017 | |

| Angles (°) | 0.4094 | |

| Impropers (°) | 0.2449 | |

| Dihedral (°) | 26.622 | |

| NOe (Å) | 0.0158 | |

| Cdih (°) | 0.5806 | |

All the solutions have good nonbonded contacts and good covalent geometry as shown by the low values of CNS energy terms and low RMSD values for bond lengths, valence angles, and improper dihedral angles. Correlation with the experimental data shows no nOe-derived distance violation greater than 0.2 Å.

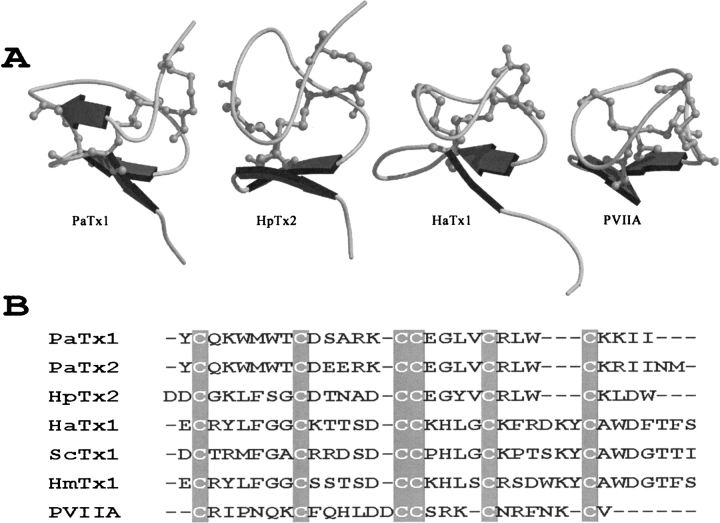

The analysis of the Ramachandran plot for the ensemble of the 25 calculated models (in PROCHECK software nomenclature) reveals that 58.9% of the residues are in the most favored regions, 31.4% in the additional allowed regions, 5.2% in the generously allowed regions, and 4.5% in the disallowed regions (data not shown). The only residue that is found constantly in a disallowed region is Leu 23, which is in a γ-turn conformation: The average angle values for the 25 solutions are 80.6 ± 4.0 for angle ψ and −54.4 ± 8.3 for angle ϕ and a hydrogen bond connects the carboxyl oxygen of Arg 22 and the amide proton of Trp 24. The conformation of this turn present in all ICK toxins depends upon its length, in some toxins described as a β-turn, and in others as a undefined loop (see Fig. 4 ▶).

Figure 4.

(A) MOLSCRIPT representation of the structure of ICK toxins that act against KV channels. From left to right: PaTx1 and HpTx2 (Kv4.2), HaTx1 (Kv2.1), κ-PVIIA (shaker K+). (B) Sequence alignment of PaTx1 with other toxins acting against K+ channels. PaTx1, PaTx2 (Phrixotoxins 1 and 2) from Phrixotrichus auratus, HpTx2 (Heteropodatoxin 2) from Heteropoda venatoria, HaTx1 (Hanatoxin 1) from Grammostola spatulata, ScTx1 (Stromatoxin 1) from Stromatopelma calceata, HmTx1 (Heteroscodratoxin 1) from Heteroscodra maculata, PVIIA (κ-conotoxin PVIIA) from Conus purpurascens (see references in text).

Structure description

The convergence of the 25 final structures (Protein Data Bank identification: 1V7F) allowed us to describe the structure of PaTx1 which consists of a compact disulfide-bonded core from which three loops (3–6, 10–13, and 16–19) and the N and C termini emerge. This fold places PaTx1 in the ICK family. Figure 3A ▶ shows a stereopair representation of the best-fit superimposition of the backbone traces of the 25 best structures and Figure 3B ▶ shows a MOLSCRIPT representation of the average structure.

The existence of Hα19-Hα27, Hα19-HN28, and Hα27-HN20 nOe together with the upfield shift of the HN protons of residues 20 and 26 compared to random coil values and associated with large Hα-HN coupling constants and slowly exchanging HN protons for residues 19, 20, and 26 indicated a short two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet as the only secondary structure. It includes residues 19–20 for the first strand and residues 26–27 for the second strand. The two strands are well detected by the PROCHECK-NMR software. A third extended structure is observed between residues Trp 7 and Cys 9. Hydrogen bonds are detected between the carboxyl oxygen of Trp 7 and the amide proton of Cys 25, and between the amide proton of Cys 9 and the carboxyl oxygen of Leu 23 (Fig. 3B ▶). This third extended strand has been similarly described in several other ICK toxins (Mosbah et al. 2000).

All the amide protons of PaTx1 resonate at conventional frequencies with the exception of Lys 4, which shows an unusual chemical shift for its amide proton (i.e., 5.01 ppm at 290 K, 5.19 ppm at 300 K, and 5.25 ppm at 310 K). Determination of the structure of PaTx1 gives an explanation of this unusual chemical shift: The amide proton is placed in the neighborhood of the aromatic ring of Trp 7 as shown in Figure 3C ▶. The ring current of Trp7 creates an electromagnetic shield that dramatically affects most of the chemical shifts of the Lys 4 protons (Table 1). This is also observed for the chemical shifts of Leu 23, similarly affected by the ring current effect of Trp 24.

Comparison with related toxins

The fold of PaTx1 places it in the inhibitor cystine knot (ICK) peptide family (Craik et al. 2001). The ICK fold family includes numerous toxic and inhibitory peptides from animal venoms. Many ion channels effectors from marine snails, spider, and scorpion venoms share this fold, although this common molecular scaffold supports a wide diversity of pharmacological profiles. Toxins folded according to the ICK motif can demonstrate varying specificity against different subtypes of voltage-dependent calcium (Mosbah et al. 2000; Bernard et al. 2001), sodium (Omecinsky et al. 1996), or potassium channels. In spider toxins, the ICK fold has also been associated with inhibition of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs; Escoubas et al. 2000a, 2003). Among potassium channel toxins, PaTx1 and its isoform PaTx2 are active on Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 potassium channels, κ-conotoxin PVIIA from the cone snail Conus purpurascens acts on shaker channels (Scanlon et al. 1997; Savarin et al. 1998; Shon et al. 1998), the hanatoxins HaTx1 and HaTx2 act on Kv2.1 channels (Swartz and MacKinnon 1995; Takahashi et al. 2000; Lou et al. 2002), and the heteropodatoxin HpTx2 is active on Kv4.2 (Sanguinetti et al. 1997; Bernard et al. 2000). We have also recently described novel toxins from the venom of the theraphosid spiders Stromatopelma calceata (ScTx1) and Heteroscodra maculata (HmTx1 and HmTx2), which inhibit different subtypes of both Kv2 and Kv4 channels (Escoubas et al. 2002). Common features of these peptides are their activity against voltage-dependent channels, related amino acid sequences with highly conserved cysteine arrangement (Fig. 4B ▶), and a similar ICK scaffold with three disulfides bridges and a two- or three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (Fig. 4A ▶).

As the ICK scaffold can bear a variety of pharmacological functions, careful analysis of the molecular surface of the toxin and delineation of a putative functional surface is of utmost importance to understand how subtle variations of the primary sequence influence the spatial structure of the toxin and hence define a specific pharmacology. With that aim, our group has developed a prediction method of the molecular dipole moment which reveals the electrostatic anisotropy of peptides. The molecular surface through which the dipole emerges is hypothesized to be involved in the interaction with the receptor site of the toxin (Blanc et al. 1997; Fremont et al. 1997; Ferrat et al. 2001). This prediction method appears to work well for toxins acting by pore occlusion, for which structure–activity data based on site-directed mutagenesis is available. The predicted interaction surface is confirmed by the reduction in biological activity in series of residue analogs (Sabatier et al. 1994; Inisan et al. 1995; Fremont et al. 1997).

For PaTx1, the overall charge distribution reveals a marked electrostatic anisotropy that is represented by the dipole moment shown in Figure 5A ▶. The electrostatic calculation shows that this dipole emerges through the β-sheet (near the Lys 26) defining a potential interaction surface composed of three basic residues (Lys 26, Lys 27 in the antiparallel β-sheet, and Arg 22 in the turn), two aromatic residues (Trp 24, Trp 5) and two hydrophobic amino acids (Leu 23 and Ile 28).

Figure 5.

(A) Orientation of the dipole moment of PaTx1 (top center) emerging through Lys 26. The resulting putative functional surface of PaTx1 is represented (in the same orientation) in B, centered around Lys 26 and the hydrophobic patch (top center). The same procedure was used to generate the corresponding dipoles of HaTx1 (top left), HpTx2 (top right), ScTx1 (bottom left), and PaTx2 (bottom right). The residues are colored green for polar uncharged residues, blue for basic residues, red for acidic residues, purple for aromatic residues, and yellow for aromatic residues. (B) Putative functional surfaces of the toxins represented in CPK (TURBO software), in the same orientation as in A, centered around basic residues and the hydrophobic patch. The residues are colored green for polar uncharged residues, blue for basic residues, red for acidic residues, purple for aromatic residues, and yellow for aliphatic residues.

The dipole moments of PaTx1, HpTx2, and HaTx1 are compared in Figure 5A ▶. Interestingly, the dipole moment of PaTx1 emerges through Lys 26 similarly to the dipole of HpTx2, which emerges through Lys 27. These two toxins, both isolated from spider venom, although from different families, act on the same channel (Kv4.2) and present a very similar putative surface. Close to the central lysine, another basic residue is present (Arg 22 or Arg 23 for PaTx1 and HpTx2, respectively), as well as an aromatic cluster (Trp 5 and Trp 24 for PaTx1, Phe 7, Trp 25, and Trp 30 for HpTx2) and an aliphatic side chain (Leu 23 or Leu 24 for PaTx1 and HpTx2, respectively). At first glance, these surfaces appear similar to those of other Kv channel inhibitors that occlude the extracellular entryway of the pore, such as conotoxin κ-PVIIA (Shon et al. 1998). In those toxins, a critical lysine residue is involved in pore blocking and is always adjacent to an aromatic residue such as tryptophan or phenylalanine, forming a “critical dyad” as first defined by Dauplais et al. (1997).

However, PaTx1 has been described as a gating modifier (Diochot et al. 1999), and affects channel function by modulating voltage-dependent gating and not by pore occlusion. Similarly, hanatoxin 1, another KV channel gating modifier, acts via binding to the voltage-sensing region of the Kv2.1 channel, on the extracellular loop between segments S3 and S4 (Swartz and MacKinnon 1995,Swartz and MacKinnon 1997a,b,Li-Smerin and Swartz 2001), thus affecting transmembrane movement of the voltage-sensing domain. The three-dimensional structure of HaTx1 has been solved by NMR (Takahashi et al. 2000) and a putative interaction surface was proposed, comprising a large hydrophobic patch (residues Tyr 4, Leu 5, Phe 6, Tyr 27, Ala 29, and Trp 30) surrounded by basic residues (Lys 22, Arg 24, and Lys 26; Fig. 5B ▶).

In comparison with the three-dimensional structures of other gating-modifier toxins (Cse-V and ATX III) Takahashi et al. (2000) proposed that the putative interactive surface of HaTx1 could be homologous to the surface of Cse-V and ATX III. Indeed these peptides present a large hydrophobic patch (composed of five tyrosines for Cse-V and one tyrosine, two prolines, and two tryptophans for ATX III) surrounded by basic residues (Lys 13 and Lys 55 for Cse-V and Arg 1 and Lys 26 for ATX III). The dipole moment calculation applied to HaTx1 shows that the dipole emerges near Lys 26, through a surface composed of basic residues (Arg 24 and Lys 10), as well as aromatic amino acids (Phe 23 and Tyr 27) and an acidic residue (Asp 25). This point of emergence of the dipole moment is perpendicular to the hydrophobic patch described by Takahashi et al. The same calculation applied to Cse-V and ATX III shows that the dipole moment also emerges through the basic residues Arg 1 and Lys 26 for ATX III; Lys 13 and Lys 55 for Cse-V, perpendicular to the hydrophobic patch (data not shown). In Cse-V, these residues are considered essential for the toxicity (Jablonsky et al. 1995).

All these toxins acting on voltage-gated channels thus appear to possess a similar surface pattern, comprising a hydrophobic patch surrounded by basic residues from which the calculated dipole moment emerges. The structure of PaTx1 identifies the same pattern: The dipole moment emerges through Lys 26, perpendicular to Lys 26 and Lys 27, and is associated with a hydrophobic patch composed of Met 6, Trp 5, Trp 7, and Trp 24. For the couple HaTx1/ Kv2.1, the accepting surface on the channel has been determined by site-directed mutagenesis to involve the residues Ile 273, Phe 274, Glu 277, Arg 290, and Arg 296 (Swartz and MacKinnon 1997b). Both hydrophobic and electrostatic interaction would therefore take place at the toxin/channel interface, in accordance with our hypothesis.

To complete our study and verify whether the same model could apply to other toxins modulating Kv channels, we modeled both PaTx2, an isoform of PaTx1 also isolated from Phrixotrichus auratus venom (Diochot et al. 1999), and ScTx1 isolated from the venom of Stromatopelma calceata (Escoubas et al. 2002). PaTx2 possesses a high sequence similarity with PaTx1, differing only by two acidic residues at positions 11 and 12 and two C-terminal residues. PaTx2 is mainly active on Kv4.2 and Kv4.3, whereas ScTx1 is active on Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 and is the most potent inhibitor known to date for the Kv4.2 channel (IC50 = 1.2 nM). These two toxins are known to belong to the gating-modifier family, and their characteristics of channel inhibition are very similar to those of HaTx1, which blocks Kv2.1 and Kv4.2 channels.

The calculation of the dipole moment for the PaTx2 model shows that the dipole emerges from the β-sheet but that the point of emergence is somewhat different when compared to the dipole of PaTx1. It emerges through Arg 27 (through Lys 26 in PaTx1), defining a surface composed of a basic residue (Arg 27), aromatic residues (Trp 5, Ile 28, and Ile 29) and an acidic residue (Glu 17). Similar to PaTx1, the dipole is perpendicular to the hydrophobic patch composed of Met 6, Trp 5, Trp 7, and Trp 24 (Fig. 5A ▶). The difference between the residues from which the dipole moment emerges (Arg 27 for Patx2 and Lys 26 for PaTx1) and the additional presence of an acidic residue could provide an explanation for the reduced affinity of PaTx2 for Kv4.2 (IC50 = 5 nM for PaTx1 and IC50 = 34 nM for PaTx2) and Kv4.3 (IC50 = 28 nM for PaTx1 and IC50 = 71 nM for PaTx2).

For ScTx1, the dipole emerges through Lys 26, from a surface comprising a basic residue (Lys 26) as well as aromatic ones (Phe 6, Ala 8, and Tyr 27; Fig. 5A ▶). In HaTx1, the toxin surface perpendicular to the dipole moment orientation is composed of residues Met 5, Phe 6, Tyr 27, Ala 29, and Trp 30. In the model of ScTx1, no acidic residue is present in the surface from which the dipole moment emerges, in contrast to HaTx1. This feature is perhaps to be correlated with the different affinity of ScTx1 and HaTx1 for the Kv2.1 channel (IC50 = 12.7 nM for ScTx1 and IC50 = 42 nM for HaTx1) and its much higher affinity for Kv4.2.

The sequences of ScTx1, HaTx1, HmTx1, PaTx1, PaTx2, and HpTx2 show conservation of an aromatic residue before the last cysteine (Fig. 4B ▶): tyrosine for ScTx1, HaTx1, and HmTx1, tryptophan for PaTx1, PaTx2, and HpTx2. In HmTx2, a structural analog of HmTx1, this aromatic amino acid is replaced by a hydrophobic residue (Ile instead of Tyr) and unlike HmTx1, HmTx2 has weak activity against Kv2.1 and is devoid of activity on Kv2.2, Kv4.1, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3 (Escoubas et al. 2002). The superposition of the Cα trace of the six toxins shows that these aromatic residues are placed in the same locus, and that the basic residue from which the dipole emerges is located nearby. The conservation of a hydrophobic residue in a position close to a basic residue may therefore be of importance for the interaction with the target channel, forming a functional dyad. The calculated model of the toxin HmTx1 also possesses the same overall pattern of a hydrophobic patch and basic residues but the calculation of the dipole moment of this protein shows that the dipole emerges through the hydrophobic patch and not through the basic residue (data not show). This result has to be interpreted in the light of the different activity of this toxin when compared with HaTx1, in spite of their sequence similarity.

We therefore propose that the conserved orientation of the dipole moment that emerges through or in the immediate vicinity of a basic residue, combined with the presence of a hydrophobic patch could delineate the interaction surface of the toxin with its receptor. The dipole moment of the toxins would help orient the toxin in the electrostatic field of the channel, and binding could result from the combined interaction of the hydrophobic patch and the basic residues from which the dipole emerges, with complementary residues on the channel. Although dipole moments calculated on all so far known gating modifiers show a similar orientation, subtle differences in dipole orientation and toxin surface could affect both the dipole and the charge distribution on the surface, inducing the observed differences in the activity of PaTx1, HaTx1, ScTx1, and HmTx1. To check whether the electrostatic dipole of a gating modifier toxin may act in the same way as for pore blockers, we analyzed the charge distribution of the receptor domain, that is, the S3-S4 segment of Kv4.2. We modeled this segment on the basis of the KvAP X-ray structure (Jiang et al. 2003). The S3 helix is mainly acidic whereas the S4 helix is rich in basic residues. As a consequence, the resulting local dipole is oriented from S3 toward S4 and therefore could play a role in the orientation of the gating modifier toxins with regard to their receptor site.

Based on the above, our results using the dipole moment prediction model appear to be consistent with the contact surface of the voltage-gating modifier toxins, proposed by others (Takahashi et al. 2000). While this work was submitted for publication, an interaction model of Kv gating modifier toxins with the S3–S4 segment of Kv channels was proposed, outlining the same interaction surface (Shiau et al. 2003). However, the structure of mammalian Kv channels is still the objet of controversy, as descriptions of the structures of the KCSA and KvAP channels yielded contradictory results (Jiang et al. 2003). In the recently described KvAP structure, the S3–S4 segment would be buried in the lipid bilayer, a feature difficult to reconcile with the extracellular action of peptide toxins.

We therefore believe that until further work has been conducted to delineate the exact toxin channel contact surface for both hanatoxin type and phrixotoxin type Kv channel gating modifiers, docking modeling remains speculative. Site-directed mutagenesis of PaTx1 will shed additional light on the toxin-receptor binding mechanism on Kv4.2, and confirm the hypothesis of the interacting surfaces based on our structural investigations.

Materials and methods

Peptide synthesis and refolding

PaTx1 was produced by solid-phase synthesis using the 0.1 mMole Fmoc methodology on an Applied Biosystems 433A peptide synthesizer. A Rink amide resin (4-(2′,4′-Dimethoxyphenyl-Fmoc-aminomethyl)-phenoxy resin) was used to provide the amino group at the C terminus. Chemical synthesis, cleavage, and deprotection were performed as previously described (Corzo et al. 2000). The crude linear synthetic peptide was dissolved in 20% aqueous acetonitrile and purified to 90%–95% homogeneity by reversed-phase HPLC on a semipreparative column (5C8MS, 10 × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque). Refolding and formation of the disulfide bridges was achieved by air oxidation for 72 h at 4°C. The linear peptide (10−5 M final) was solubilized in an aqueous refolding buffer containing 2 M ammonium acetate with 1 mM cystine and 8 mM cysteine as the redox couple. Formation of the refolded peptide was monitored by analyzing aliquots by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry after 4 h, and then every 24 h. The refolded synthetic toxin was purified on a C8 RP-HPLC column (5C8MS, 10 × 250 mm, Nacalai Tesque) using a 60-min linear gradient from 0% to 60% aqueous acetonitrile/ 0.1% TFA (2 ml/min). The fraction containing PaTx1 (as confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS) was purified to homogeneity by cation-exchange chromatography using a gradient of ammonium acetate (20 mM to 1 M in 100 min, 1 mL/min) on a Tosoh SP5PW column (4.6 × 70 mm, Tosoh). The structural identity between synthetic and native peptides was verified by RP-HPLC coelution experiments, and by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

All mass spectra were acquired on a Voyager DE-Pro instrument (Applied Biosystems) in either linear or reflector positive mode using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (α-CHCA) as the matrix (5 mg/mL). Spectra were calibrated externally (HPLC fractions) or internally (pure peptides) using standard peptide mixtures. Spectra were processed in Data Explorer, and all mass calculations were done using the GPMAW software (http://www.protein.sdu.dk/gpmaw/index.html).

Sample preparation for NMR

We solubilized 2.6 mg of pure synthetic PaTx1 in 500 μL of a H2O/D2O mixture (9:1 v/v) to give a concentration of 1.5 mM at pH 3.0. The amide proton exchange rates were obtained on a sample solubilized in 500 μL of 100% D2O.

NMR experiments

The 1H NMR spectra were all recorded on a BRUKER DRX500 spectrometer equipped with an HCN probe and self-shielded triple axis gradients were used. The experiments were performed at three different temperatures, 290, 300, and 310 K, to solve assignment ambiguities. Two-dimensional spectra were acquired using the States-TPPI method (Marion et al. 1989) to achieve F1 quadrature detection (Marion and Wüthrich 1983). Water suppression was obtained either using presaturation during the 1.5-sec relaxation delay and during the mixing time for NOESY spectra or with a watergate 3–9–19 pulse train (Piotto et al. 1992) using a gradient at the magic angle obtained by applying simultaneous x, y, and z gradients prior to detection. TOCSY were performed with a spin-lock time of 80 msec and a spin-locking field strength of 8 kHz. The mixing time of the NOESY experiments was set to 80 msec. The individual amide proton exchange rates were determined by recording two series of eight NOESY spectra (each experiment was 5 h long) at 290 and 300 K on the D2O sample. Amide protons still giving rise to nuclear Overhauser effect (nOe) correlations after 40 h of exchange were considered as slowly exchanging and therefore engaged in a hydrogen bond.

Analysis of spectra

The identification of amino acid spin systems and the sequential assignment were done using the standard strategy described by Wüthrich (1986) and regularly used by our group, with the XEASY graphical software (Eccles et al. 1991). The comparative analysis of COSY and TOCSY spectra recorded in water gave the spin system signatures of the protein. The spin systems were then sequentially connected using the NOESY spectra.

Experimental restraints

The integration of nOe data was done by measuring the peak volumes using a routine of XEASY. These volumes were then translated into upper limit distances by the CALIBA routine of the DIANA software (Günter et al. 1991). The lower limit distance was systematically set at 0.18 nm.

The Φ torsion angle constraints resulted from the 3JHN-Hα coupling constant measurements that were measured on a COSY spectrum with 8192 data points in the acquisition dimension. These Φ angles were restrained to −120 ± 40° for a 3JHN-Hα ≥ 8 Hz and to −65 ± 25° for a 3JHN-Hα ≤ 6 Hz. No angle constraint was assigned to a 3JHN-Hα = 7 Hz, a value considered as ambiguous.

Determination of the amide proton exchange rates led us to identify protons involved in hydrogen bonding. The oxygen partners were then identified by visual inspection of the preliminary calculated structures.

Structure calculation

The structures were calculated by the variable target function program DIANA 2.8 (Güntert et al. 1991). A preliminary set of 1000 structures was initiated including only intraresidual and sequential upper limit distances. From these, the 500 best (as judged by the absence of significant nOe violations) were kept for a second round, for which the restraints belonging to the 3 strands were injected together with the distance restraints defining the disulfide bridges (i.e., dSγ-Sγ 0.21 nm, dCβ-Sγ and dSβ-Cγ 0.31 nm) and the hydrogen bonds included in the β strands. The resulting 250 best solutions were selected for a third calculation run, including the whole set of upper limit restraints. The 50 best structures were finally refined by including the dihedral constraints together with the additional distance restraints coming from hydrogen bonds outside the β sheet.

Then, to remove bad van der Waals contacts, these 50 structures were refined by restrained molecular dynamics annealing at 1000 K (parameters file: protein-allhdg), followed by slow cooling and energy minimization (10 cycles of 1000 steps each) in the CNS software (Brunger et al. 1998).

The visual analysis of the final selection of structures was carried out with the TURBO graphic software (Roussel and Cambillau 1989) and the geometric quality of the resulting structures was assessed with the PROCHECK 3.3 and PROCHECK-NMR software (Laskowski et al. 1996).

Electrostatic calculation

The electrostatic potential and dipole moment of the toxin were calculated using the GRASP software (Nicholls et al. 1991) running on a Silicon Graphics Workstation. This calculation includes all ionizable groups in the peptide, based on the amber force field of the residues. The potential maps were calculated with a simplified Poisson–Boltzmann solver (Nicholls and Honig 1991; Nicholls et al. 1991).

Molecular modeling

Molecular modeling of the structures of PaTx2, ScTx1, and HmTx1 was achieved using the published NMR structures coordinates of PaTx1 (for PaTx2) and HaTx1 (for ScTx1 and HmTx1). The structures were calculated using the MODELLER6 software: For each of the measured NMR conformations of a given template, we calculated five models and, based on the lowest MODELLER restraints energy, we kept only the best one. Our final structure was therefore based on 20 models for ScTx1 and HmTx1 and 25 models for PaTx2.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. S. Diochot for providing a sample of native PaTx1 and verification of channel inhibition by the synthetic peptide, as well as to Dr. L.D. Rash for critical reading and English editing of the manuscript. P.E. and H.D. gratefully acknowledge continued support from Dr. T. Nakajima and the Suntory Institute for Bioorganic Research throughout the investigation of spider venom toxins.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.03584304.

References

- Bernard, C., Legros, C., Ferrat, G., Bischoff, U., Marquardt, A., Pongs, O., and Darbon, H. 2000. Solution structure of HpTX2, a toxin from Heteropoda venatoria spider that blocks Kv4.2 potassium channel. Protein Sci. 9 2059–2067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, C., Corzo, G., Mosbah, A., Nakajima, T., and Darbon, H. 2001. Solution structure of Ptu1, a toxin from the assassin bug Peirates turpis that blocks the voltage-sensitive calcium channel N-type. Biochemistry 40 12795–12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, E., Sabatier, J.M., Kharrat, R., Meunier, S., El Ayeb, M., Van Rietschoten, J., and Darbon, H. 1997. Solution structure of maurotoxin, a scorpion toxin from Scorpio maurus, with high affinity for voltage-gated potassium channels. Proteins 29 321–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macro-molecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzo, G., Escoubas, P., Stankiewicz, M., Pelhate, M., Kristensen, C.P., and Nakajima, T. 2000. Isolation, synthesis and pharmacological characterization of δ-palutoxins IT, novel insecticidal toxins from the spider Paracoelotes luctuosus (Amaurobiidae). Eur. J. Biochem. 267 5783–5795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik, D.J., Daly, N.L., and Waine, C. 2001. The cystine knot motif in toxins and implications for drug design. Toxicon 39 43–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauplais, M., Lecoq, A., Song, J., Cotton, J., Jamin, N., Gilquin, B., Roume-stand, C., Vita, C., de Medeiros, C.L., Rowan, E.G., et al. 1997. On the convergent evolution of animal toxins. Conservation of a diad of functional residues in potassium channel-blocking toxins with unrelated structures. J. Biol. Chem. 272 4302–4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLa Cruz, R., Buczek, O., Bulaj, G., and Whitby, F.G. 2003. Detergent-assisted oxidative folding of δ-conotoxins. J. Pept. Res. 61 202–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diochot, S., Drici, M.D., Moinier, D., Fink, M., and Lazdunski, M. 1999. Effects of phrixotoxins on the Kv4 family of potassium channels and implications for the role of Ito1 in cardiac electrogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 126 251–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, C., Güntert, P., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1991. Efficient analysis of protein 2D NMR spectra using the software package EASY. J. Biomol. NMR 1: 111–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas, P., De Weille, J.R., Lecoq, A., Diochot, S., Waldmann, R., Champigny, G., Moinier, D., Ménez, A., and Lazdunski, M. 2000a. Isolation of a tarantula toxin specific for a class of proton-gated Na+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 275 25116–25121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas, P., Diochot, S., and Corzo, G. 2000b. Structure and pharmacology of spider venom neurotoxins. Biochimie 82 893–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas, P., Diochot, S., Célérier, M.L., Nakajima, T., and Lazdunski, M. 2002. Novel tarantula toxins for subtypes of voltage-dependent potassium channels in the Kv2 and Kv4 subfamilies. Mol. Pharmacol. 62: 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubas, P., Bernard, C., Lambeau, G., Lazdunski, M., and Darbon, H. 2003. Recombinant production and solution structure of PcTx1, the specific peptide inhibitor of ASIC1a proton-gated cation channels. Protein Sci. 12 1332–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrat, G., Bernard, C., Fremont, V., Mullmann, T.J., Giangiacomo, K.M., and Darbon, H. 2001. Structural basis for α-K toxin specificity for K+ channels revealed through the solution 1H NMR structures of two noxiustoxiniberio-toxin chimeras. Biochemistry 40 10998–11006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont, V., Blanc, E., Crest, M., Martin-Eauclaire, M.-F., Gola, M., Darbon, H., and VanRietschoten, J. 1997. Dipole moments of scorpion toxins direct the interaction towards small- or large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Lett. Pept. Sci. 4 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Güntert, P., Braun, W., and Wüthrich, K. 1991. Efficient computation of three-dimensional protein structures in solution from nuclear magnetic resonance data using the program DIANA and the supporting programs CALIBA, HABAS and GLOMSA. J. Mol. Biol. 217 517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inisan, A.G., Meunier, S., Fedelli, O., Altbach, M., Fremont, V., Sabatier, J.M., Thevan, A., Bernassau, J.M., Cambillau, C., and Darbon, H. 1995. Structure-activity relationship study of a scorpion toxin with high affinity for apamin-sensitive potassium channels by means of the solution structure of analogues. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 45 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonsky, M.J., Watt, D.D., and Krishna, N.R. 1995. Solution structure of an Old World-like neurotoxin from the venom of the New World scorpion Centruroides sculpturatus Ewing. J. Mol. Biol. 248 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., Lee, A., Chen, J., Ruta, V., Cadene, M., Chait, B.T., and MacKinnon, R. 2003. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature 423 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis, P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, S., Chino, N., Kimura, T., and Sakakibara, S. 1996. Oxidative folding of ω-conotoxin MVIIC: Effects of temperature and salt. Biopolymers 38 733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R.A., Rullmannn, J.A., MacArthur, M.W., Kaptein, R., and Thornton, J.M. 1996. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Smerin, Y. and Swartz, K.J. 2000. Localization and molecular determinants of the Hanatoxin receptors on the voltage-sensing domains of a K(+) channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 115 673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2001. Helical structure of the COOH terminus of S3 and its contribution to the gating modifier toxin receptor in voltage-gated ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 117 205–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, K.L., Huang, P.T., Shiau, Y.S., and Shiau, Y.Y. 2002. Molecular determinants of the hanatoxin binding in voltage-gated K+-channel drk1. J. Mol. Recognit. 15 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D. and Wüthrich, K. 1983. Application of phase sensitive two-dimensional correlated spectroscopy (COSY) for measurements of 1H-1H spin-spin coupling constants in proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 113 967–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion, D., Ikura, M., Tschudin, R., and Bax, A. 1989. Rapid recording of 2D NMR spectra without phase cycling. Application to the study of hydrogen exchange in proteins. J. Magn. Res. 85 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Markley, J.L., Bax, A., Arata, Y., Hilbers, C.W., Kaptein, R., Sykes, B.D., Wright, P.E., and Wüthrich, K. 1998. Recommendations for the presentation of NMR structures of proteins and nucleic acids—IUPAC-IUBMB-IUPAB Inter-Union Task Group on the standardization of data bases of protein and nucleic acid structures determined by NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 256 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosbah, A., Kharrat, R., Fajloun, Z., Renisio, J.G., Blanc, E., Sabatier, J.M., El Ayeb, M., and Darbon, H. 2000. A new fold in the scorpion toxin family, associated with an activity on a ryanodine-sensitive calcium channel. Proteins 40 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A. and Honig, B. 1991. A rapid finite difference algorithm, utililizing successive over-relaxation to solve the Poisson–Boltzman equation. J. Comput. Chem. 12 435–445. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A., Sharp, K.A., and Honig, B. 1991. Protein folding and association: Insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.S. and Pallaghy, P.K. 1998. The cystine knot structure of ion channel toxins and related polypeptides. Toxicon 36 1573–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omecinsky, D.O., Holub, K.E., Adams, M.E., and Reily, M.D. 1996. Three-dimensional structure analysis of μ-agatoxins: Further evidence for common motifs among neurotoxins with diverse ion channel specificities. Biochemistry 35 2836–2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotto, M., Saudek, V., and Sklenar, V. 1992. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR 2 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, A. and Cambillau, C. 1989. Silicon Graphics geometry partner directory. Silicon Graphics, Mountain View, CA.

- Sabatier, J.M., Fremont, V., Mabrouk, K., Crest, M., Darbon, H., Rochat, H., Van Rietschoten, J., and Martin-Eauclaire, M.-F. 1994. Leiurotoxin I, a scorpion toxin specific for Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels. Structure-activity analysis using synthetic analogs. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 43 486–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti, M.C., Johnson, J.H., Hammerland, L.G., Kelbaugh, P.R., Volkmann, R.A., Saccomano, N.A., and Mueller, A.L. 1997. Heteropodatoxins: Peptides isolated from spider venom that block Kv4.2 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 51 491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarin, P., Guenneugues, M., Gilquin, B., Lamthanh, H., Gasparini, S., Zinn-Justin, S., and Ménez, A. 1998. Three-dimensional structure of κ-conotoxin PVIIA, a novel potassium channel-blocking toxin from cone snails. Biochemistry 37 5407–5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, M.J., Naranjo, D., Thomas, L., Alewood, P.F., Lewis, R.J., and Craik, D.J. 1997. Solution structure and proposed binding mechanism of a novel potassium channel toxin κ-conotoxin PVIIA. Structure 5 1585–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau, Y.S., Huang, P.T., Liou, H.H., Liaw, Y.C, Shiau, Y.Y., and Lou, K.L. 2003. Structural basis of binding and inhibition of novel tarantula toxins in mammalian voltage-dependent potassium channels. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 16: 1217–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shon, K.J., Stocker, M., Terlau, H., Stuhmer, W., Jacobsen, R., Walker, C., Grilley, M., Watkins, M., Hillyard, D.R., Gray, W.R., and Olivera, B.M. 1998. κ-Conotoxin PVIIA is a peptide inhibiting the shaker K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 273 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, K.J. and MacKinnon, R. 1995. An inhibitor of the Kv2.1 potassium channel isolated from the venom of a Chilean tarantula. Neuron 15 941–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1997a. Hanatoxin modifies the gating of a voltage-dependent K+ channel through multiple binding sites. Neuron 18 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1997b. Mapping the receptor site for hanatoxin, a gating modifier of voltage-dependent K+ channels. Neuron 18 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H., Kim, J.I., Min, H.J., Sato, K., Swartz, K.J., and Shimada, I. 2000. Solution structure of hanatoxin1, a gating modifier of voltage-dependent K(+) channels: Common surface features of gating modifier toxins. J. Mol. Biol. 297 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley, New York.