Abstract

AIDS is characterized by a progressive decrease of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes. Destruction of these cells may involve programmed cell death, apoptosis. It has previously been reported that apoptosis can be induced even in noninfected cells by HIV-1 gp120 and anti-gp120 antibodies. HIV-1 gp120 binds to T cells via CD4 and the chemokine coreceptor CXCR4 (fusin/LESTR). Therefore, we investigated whether CD4 and CXCR4 mediate gp120-induced apoptosis. We used human peripheral blood lymphocytes, malignant T cells, and CD4/CXCR4 transfectants, and found cell death induced by both cell surface receptors, CD4 and CXCR4. The induced cell death was rapid, independent of known caspases, and lacking oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation. In addition, the death signals were not propagated via p56lck and Giα. However, the cells showed chromatin condensation, morphological shrinkage, membrane inversion, and reduced mitochondrial transmembrane potential indicative of apoptosis. Significantly, apoptosis was exclusively observed in CD4+ but not in CD8+ T cells, and apoptosis triggered via CXCR4 was inhibited by stromal cell-derived factor-1, the natural CXCR4 ligand. Thus, this mechanism of apoptosis might contribute to T cell depletion in AIDS and might have major implications for therapeutic intervention.

During late phases of HIV-1 infection a dramatic decrease in CD4+ helper T cells leads to the development of AIDS (1). Despite intensive investigations the reason for the destruction of the CD4+ T cells is still not fully elucidated. Direct cytolytic effects of the virus and lysis of infected cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes were invoked in the destruction of the cells (2). However, other mechanisms may contribute to this effect. This assumption is supported by the finding that infection of CD4+ macrophages does not lead to depletion of these cells (3). In addition, the number of dying cells is higher than the number of infected cells. Furthermore, not only T cells but also NK cells and neurons are found dead (3). Therefore, indirect mechanisms may also play a role in helper T cell destruction during AIDS and apoptosis may be one of the mechanisms causing the destruction. In fact, Finkel et al. showed in HIV-1-infected children and simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques that predominantly noninfected cells are eliminated by apoptosis (4). In addition, infected and noninfected T cells of HIV-1-infected individuals show enhanced spontaneous apoptosis in vitro (5) and are more sensitive to activation-induced cell death than T cells from noninfected individuals (5–7). Furthermore, enhanced sensitization is paralleled by enhanced expression of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor and the CD95 ligand (APO-1L/FasL) and by enhanced sensitivity to CD95-mediated apoptosis (8–10).

It has been reported that HIV-1 gp120 crosslinked by anti-gp120 antibodies (Abs) induced apoptosis in infected and noninfected T lymphocytes (11–13). Furthermore, murine T cells expressing a human CD4 transgene were deleted in vivo in the transgenic mice by injection of HIV-1 gp120 and gp120-specific Abs from sera of HIV-1-infected patients (14). Finally, Westendorp et al. (13) showed that stimulation of CD4 by gp120 and anti-gp120-Abs led to enhanced expression of CD95L and induced apoptosis also in noninfected bystander T cells. Apoptosis was induced by increased expression of CD95L and was observed later than 12 h after induction of cell death. In these experiments, however, gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis was only partially inhibited by reagents that block binding of CD95L to CD95 (13). The finding that blocking was never complete suggested that the CD95 system was not the only death-inducing system, but that other such system(s) might exist.

HIV-1 gp120 binds to T cells via CD4 (15) and the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (fusin/LESTR) (16). Therefore, we investigated whether CD4 and CXCR4 mediate gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis also by a CD95-independent mechanism.

METHODS

Cells and Cell Culture Conditions.

Jurkat and human peripheral blood-acute lymphatic leukemia (HPB-ALL) cells are human T cell lines with bright expression of CD3 and CD4. In addition, HPB-ALL cells also express the activation markers CD25 and CD69 brightly. The cells are negative for CD95. All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum.

Purification of Human Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes (PBL).

PBL were isolated from blood of healthy human donors by Ficoll–Hypaque density centrifugation. The mononuclear cell fraction was then depleted from macrophages by adherence to cell culture flasks for 1 h at 37°C.

Immunomagnetic Separation of Human PBL.

After preincubation with Abs against CD4 (HP2/6, kindly provided by G. Moldenhauer, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg) or CD8 (OKT8, Ortho Diagnostic) for 20 min at 4°C, human T cells were depleted by magnetic beads coupled to anti-mouse Ig (Paesel Hanau, Germany). The remaining cells were stained for CD4 and CD8 expression. Contamination of CD8+ (CD4+) cells in the CD4+ (CD8+) population, determined by surface staining, was <0.3% (0.5%) of the cells.

Surface Staining.

Cells (5 × 105) were incubated with 10 μg/ml primary mouse Abs for 15 min at 4°C, washed, incubated for another 15 min with 10 μg/ml phycoerythrin-labeled goat-anti mouse Abs (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and after further washing analyzed in a FACScan cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

Transfections.

CD4 transfectants were obtained by electroporation of 5 × 106 human B lymphoma cells BJAB with 2 μg of the hygromycin-resistance vector pKEX2XL and 10 μg of pCDM8-CD4 (kindly provided by W. Kolanus, University of Munich). Clones were selected in the presence of hygromycin B (450 units/ml). For CXCR4 transfectants 10 μg of pcDNA3-tag-CXCR4 (kindly provided by M. Moulard, University of Marseilles, France) were used and clones were selected in the presence of G418 (4 mg/ml). Clones were then tested for surface expression of CD4/CXCR4 by immunofluorescence.

Induction and Measurement of Cell Death.

Samples containing 5 × 104 HPB-ALL cells or 2 × 105 PBL were incubated in 100 μl of culture medium at 37°C in the presence or absence of 5 μg/ml mAbs against CD4 (HP2/6) (17) or CXCR4 (12G5, R & D Systems) (18). After 15 min, cells were transferred to a microtiter plate previously coated with 100 μg/ml sheep-anti-mouse Ig (Boehringer Mannheim). In Fig. 1B Abs (25 μg/ml) were directly coated to a 96-well plate in buffer to exclude isotype effects. For induction of CD95-mediated cell death 1 μg/ml of the CD95-directed mAb anti-APO-1 (19) was used. The amount of subdiploid nuclei was determined as described (20).

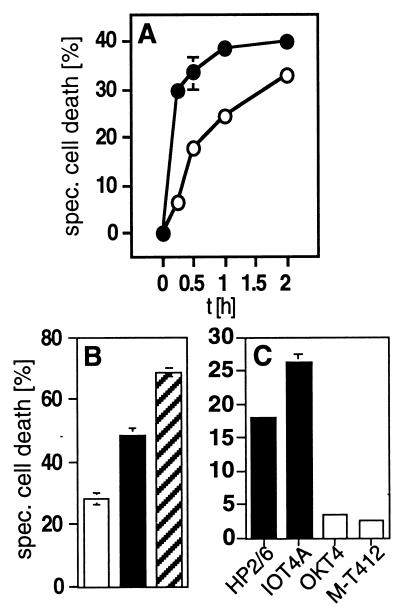

Figure 1.

CD4 and CXCR4 mediate a rapid type of cell death in human cells. (A) Kinetics of anti-CD4- (•) and anti-CXCR4-induced (○) cell death in HPB-ALL cells. Cells were preincubated with the anti-CD4 mAb HP2/6 or the anti-CXCR4 mAb 12G5 for 15 min at 37°C, then receptors were crosslinked by coated sheep-anti-mouse Abs (100 μg/ml). Cell death was determined by FSC/SSC analysis at the indicated time points. One representative experiment of three performed in triplicates is shown. (B) Induction of cell death in HPB-ALL cells by mAbs to CXCR4 (□), to CD4 (■), or to both receptors (▨), respectively. Induction of cell death with both mAbs was additive. Cell death was induced as described in Materials and Methods and was determined 2 h after mAb exposure by FSC/SSC analysis. One experiment representative of two, done in triplicates, is shown. (C) CD4-mediated cell death in HPB-ALL cells is triggered only by mAbs that interfere with gp120 binding, i.e. the anti-CD4 mAbs HP2/6 or IOT4A (■). The anti-CD4 mAbs OKT4 and M-T412 (□) that do not interfere with gp120 binding did not induce cell death. Cell death was determined after 2 h by FSC/SSC analysis. One of two experiments with similar results, done in triplicates, is shown. Panels are expressed as % specific cell death. Background was between 6.63% and 9.49%.

Measurement of Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential (ΔΨm).

After pretreatment of 1 × 105 cells with or without an apoptotic stimulus, cells were harvested and incubated with 40 nM 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (Molecular Probes) (3) for 13 min at 37°C followed by analysis in a FACScan cytometer (21). Reduced ΔΨm can be measured only in a small time window during cell death. Therefore, the absolute amount of cells that show reduced ΔΨm is always lower than the amount of apoptotic cells.

Measurement of Phosphatidylserine Exposure.

After induction of cell death cells were stained on ice with 2.5 μg/ml of the lipophilic dye MC540 (Sigma) or the viability dye propidium iodide (Sigma) and analyzed in a FACScan cytometer (22).

Inhibition of Cell Death by the Caspase Inhibitor Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-(O-methyl)-fluoromethyl Ketone (zVAD-fmk).

Before induction of cell death cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 20–200 μM zVAD-fmk (Bachem) for 30 min at 37°C.

Internalization of CXCR4 by Incubation with Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 (SDF-1).

Cells were incubated with 250 nM synthetic SDF-1 (kindly provided by M. Baggiolini, University of Bern, Switzerland) (23) for 30 min at 37°C. After washing the cells twice with cold medium, they were treated with 0.05 M glycine⋅HCl/0.1 M NaCl (pH 3.0) for 1 min at room temperature to elute SDF-1 from the occupied receptors (24). Subsequently, CXCR4 expression was determined by surface staining and cell death was induced.

Electron Microscopy.

Approximately 1 × 108 cells were fixed with 0.25% glutaraldehyde for 3 min. The cells were embedded in agar, postfixed with reduced osmium, and embedded in Epon 812 (Sigma). Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and examined in a Philips EM 301 electron microscope.

Guanosine 5′-O-(γ-[35S]Thiotriphosphate) (GTP[γ-35S]) Binding Assay.

Cells (1 × 108) were homogenized by nitrogen cavitation. Then a crude membrane fraction was obtained by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Binding of GTP[γ-35S] to membranes was determined as described (25).

RESULTS

CD4 and CXCR4 Mediate a New and Rapid Type of Cell Death in Human Cells.

HIV-1 gp120 binds to T cells via CD4 (15) and the chemokine receptor CXCR4 (16). Therefore, we investigated whether CD4 and CXCR4 mediate gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis. To mimic gp120 binding and to activate both cell surface receptors individually, we initially used mAbs against CD4 (HP2/6) or CXCR4 (12G5). The mAbs used interfere with binding of gp120 as determined by surface staining or inhibit HIV-1 infection, respectively (data not shown, refs. 17 and 18).

Surprisingly, we found that both anti-CD4 and anti-CXCR4 mAbs, crosslinked with anti-mouse Abs, induced a rapid type of cell death in all CD4+CXCR4+ cells studied (human PBL and the T leukemia cells Jurkat and HPB-ALL) (Fig. 1). In the latter cell line maximal cell death induction of ten independent experiments was with anti-CD4 mAbs 35.22% ± 9.18% and anti-CXCR4 mAbs 24.64% ± 8.12%. The cell death observed was dose dependent (data not shown) and reached a plateau within 2 h after CD4 or CXCR4 triggering (Fig. 1A). Engagement of both cell surface receptors was additive (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the anti-CD4 mAbs that bind to epitopes that interfere with gp120 binding (HP2/6, IOT4A), anti-CD4 mAbs that do not interfere with gp120 binding (OKT4, M-T412) were incapable of eliciting cell death upon crosslinking. These data suggest an epitope-specific mechanism of cell death induction (Fig. 1C). Only CD4 and CXCR4 appeared to mediate this novel type of cell death. In fact, crosslinking of CD3 by anti-CD3 mAbs (OKT3) and secondary anti-mouse Abs did not lead to induction of cell death in HPB-ALL cells even after 24 h and in concentrations up to 100 μg/ml of anti-CD3 mAbs, although CD3 is expressed to a much higher extent than CD4 on these cells (mean fluorescence intensity, 1,038.4 vs. 213.0).

The rapid kinetics of the death pathway are distinct from the kinetics of CD95-mediated apoptosis. Therefore, we determined cell death after <2 h in all experiments. Furthermore, HPB-ALL cells were CD95-negative and resistant to anti-CD95-induced apoptosis (data not shown). Thus, these cells provided an ideal model for our investigations and cell death showed the following additional characteristics: It was not mediated by the CD95-, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand system and was independent of known caspases. Thus, it was not inhibited by CD95- and TNF-R1-decoys, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mRNA was not detected by reverse transcription–PCR (data not shown), and cell death was not blocked by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (20–200 μM), respectively (Fig. 2A). Likewise, caspase-8, caspase-3, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage was not observed and cell death was not inhibited by overexpression of bcl-2 in transfected Jurkat cells (data not shown). In addition, endonuclease activation, generation of multimers of 180 bp (“DNA ladder”) or formation of subdiploid nuclei were not detected (Fig. 2B) even 96 h after induction of cell death (data not shown).

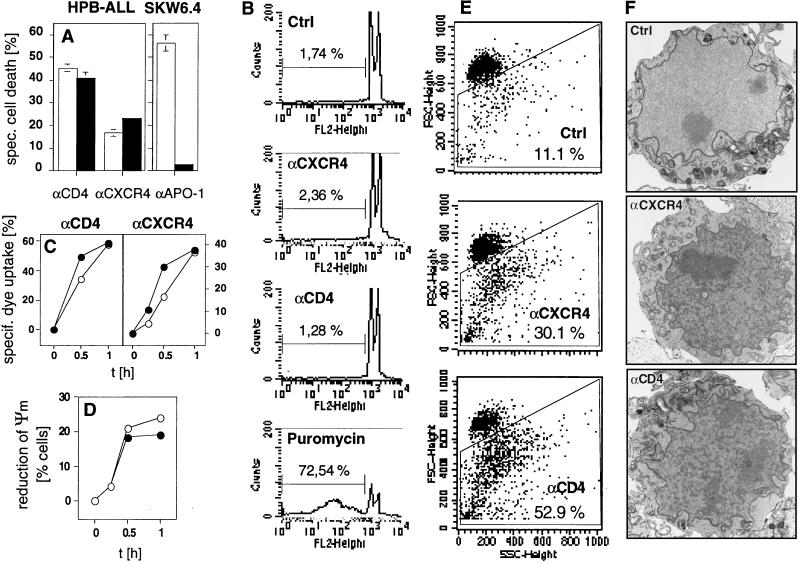

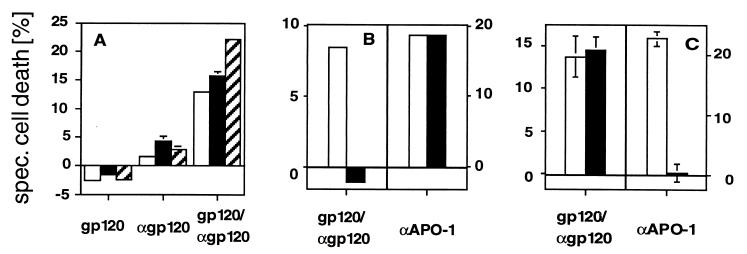

Figure 2.

(A) Cell death induced by anti-CD4 or anti-CXCR4 mAbs is not inhibited by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. HPB-ALL cells or anti-CD95-sensitive SKW6.4 cells were incubated in the absence (□) or presence (■) of 100 μM zVAD-fmk for 30 min at 37°C. Cell death was determined 2 h after triggering with anti-CD4 or anti-CXCR4 mAbs or 24 h after triggering with anti-APO-1 mAbs by FSC/SSC analysis. (B) DNA fragmentation is not observed during CD4- and CXCR4-mediated apoptosis. HPB-ALL cells (5 × 105) were incubated for 2 h with anti-CD4 or anti-CXCR4 mAbs or for 96 h with 10 μg/ml puromycin. Formation of subdiploid nuclei was determined after overnight incubation by propidium iodide staining. (C) Loss of asymmetry in plasma membrane phospholipids precedes loss of cell viability in anti-CD4- and anti-CXCR4-induced apoptosis. At the indicated time points after induction of cell death, HPB-ALL cells were harvested and stained with propidium iodide (○) or the lipophilic dye MC540 (•). The values are the mean ± SD of triplicates of one of two similar experiments. (D) Reduction of ΔΨm occurs during CD4- (○) and CXCR4-mediated (•) cell death. ΔΨm was determined in comparison to anti-mouse-Ig-treated controls at the indicated time points after apoptosis induction in HPB-ALL cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Apoptotic HPB-ALL cells show changes in FSC/SSC typical of apoptosis. The values represent the percentage of apoptotic cells with reduced FSC and increased SSC (gated cells). Cell death was induced as described and determined after 2 h. Experiments were done in triplicates more than five times. One representative example of each group is shown. (F) Anti-CD4- and anti-CXCR4-treated HPB-ALL cells show condensed cytoplasm and condensed chromatin. Representative electron micrographs of HPB-ALL cells (×6,000) treated for 25 min with secondary Abs alone, anti-CXCR4 or anti-CD4 mAbs are shown. Condensation was observed in 0 of 127 (0%) control cells, 21 of 84 (25%) anti-CXCR4- and 46 of 120 (38%) anti-CD4-treated cells. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

However, loss of asymmetry in plasma membrane phospholipids with exposure of surface phosphatidylserine residues stained by the lipophilic dye MC540 (merocyanine 540) was observed and it preceded loss of cell viability as determined by propidium iodide uptake (22, 26) (Fig. 2C). T cells incubated with anti-CD4 or anti-CXCR4 also showed reduction of ΔΨm, an early event during apoptotic cell death (21) (Fig. 2D). In addition, changes in forward/side scatter (FSC/SSC), typical of apoptosis, were observed with reduction in cell size (FSC) and increase in granularity (SSC) (27) (Fig. 2E). Finally, nuclear chromatin condensation was detected during CD4- and CXCR4-mediated cell death by electron microscopy (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these four parameters make it likely that the cell death induced by triggering of CD4 and CXCR4 is a type of rapid apoptosis not previously described.

CD4 and CXCR4 Induce Apoptosis Independently of Each Other.

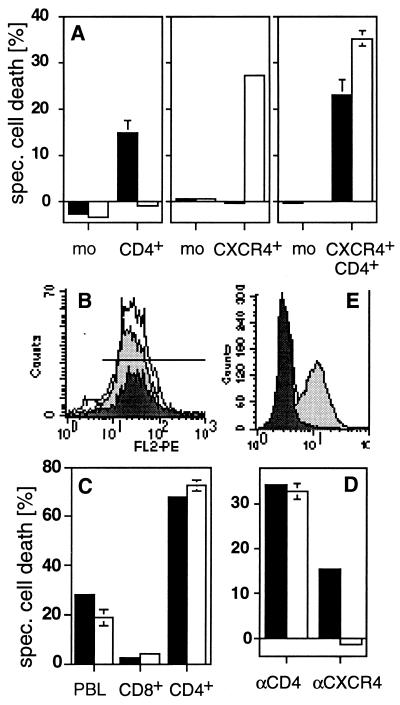

To investigate whether CD4 and CXCR4 may act separately, we stably transfected the CD4−CXCR4− human B lymphoma cells BJAB with either receptor alone or both together. We found that triggering of either receptor alone was sufficient to induce apoptosis (Fig. 3A). Thus, although the transfected cells were malignant B cells lacking p56lck and expressing a different signaling machinery than T cells (28), apoptosis was clearly observed in every transfected clone tested (four CD4+, five CXCR4+ and four CD4+CXCR4+ clones).

Figure 3.

CD4 and CXCR4 induce cell death independently of each other. (A) Anti-CD4-induced cell death (■) was observed in all CD4+ transfectants of the human B lymphoma cells tested. All CXCR4+ transfectants obtained were sensitive to anti-CXCR4-induced cell death (□). Double transfectants were sensitive to cell death induced by both mAbs. One representative example of every group of transfectants is shown. mean fluorescence intensity of CD4/CXCR4 of the clones used was: mock (3.85/2.57), CD4+ (47.12/2.56), CXCR4+ (4.03/65.7), and CD4+CXCR4+ (76.72/102.44). The killing assay was performed five times in triplicates as described in Materials and Methods. (B) CD8+ T cells (dark gray peak) express more CXCR4 than CD4+ T cells (light gray peak) (PBL = white peak). (C) Only CD4+ T cells are killed by anti-CD4 (■) and anti-CXCR4 (□) mAbs. Human PBL were sorted by negative selection with magnetic beads and cell death was induced. The experiment shown was done in triplicates and is representative of five independent experiments. (D) Down-regulation of CXCR4 by SDF-1 prevents anti-CXCR4- but not anti-CD4-induced cell death. HPB-ALL cells were preincubated in the absence (■) or presence (□) of 250 nM SDF-1 for 30 min at 37°C. The assay was performed in triplicates. One of five similar experiments is shown. (E) Down-regulation of CXCR4 was controlled by surface staining. White peak, control antibody; light gray peak, CXCR4 staining; dark gray peak, CXCR4 staining after preincubation with SDF-1 (24). Cell death in A, C, and D was determined by FSC/SSC analysis after 2 h.

Only CD4+ T Cells Are Sensitive to Anti-CD4 and Anti-CXCR4-Induced Apoptosis.

CD8+ T cells expressed a similar density of CXCR4 as CD4+ T cells (mean fluorescence intensity of CXCR4 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was 31.8 and 40.8, respectively (Fig. 3B). Significantly, however, apoptosis triggered through CXCR4 was exclusively induced in CD4+ and not in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3C). SDF-1, the natural ligand of CXCR4 (23, 29), did not induce apoptosis in HPB-ALL cells and PBL (data not shown). This might be due to epitope binding or insufficient crosslinking by SDF-1. However, SDF-1 induced down-regulation of CXCR4 (24) and abrogated anti-CXCR4-induced cell death completely (Fig. 3D).

CD4- and CXCR4-Mediated Apoptosis Does Not Involve Giα Activation.

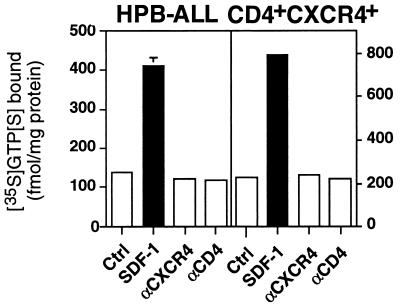

Signaling via CXCR4 was described to involve activation of Giα (30). Our experiments, however, showed that, although SDF-1 activated Giα, induction of apoptosis in HPB-ALL cells and the CD4+CXCR4+ transfectants was independent of Giα activation (Fig. 4). CXCR4-mediated apoptosis might therefore involve signaling via small GTPases (31) or an as yet unknown signaling cascade.

Figure 4.

CD4- and CXCR4-mediated apoptosis does not involve Giα activation. Binding of GTP[γ-35S] to membranes of HPB-ALL cells and CD4+CXCR4+ transfectants was assayed in the absence (Ctrl) or presence of SDF-1 (200 nM), anti-CXCR4 (10 μg/ml), or anti-CD4 mAbs (10 μg/ml). The experiment shown was done in triplicate and is a representative of three experiments done.

Features of gp120/Anti-gp120-Induced Apoptosis in Human PBL Are Identical to Anti-CD4- or Anti-CXCR4-Induced Apoptosis.

Soluble gp120 and anti-gp120 Abs are found in sera of HIV-1-infected individuals (32, 33). Therefore, we investigated, whether the above described form of apoptosis can be induced in human PBL incubated with recombinant T-tropic gp120 (HIV-1 IIIB) and anti-gp120 Abs. An identical type of apoptosis was observed under these conditions (Table 1), whereas gp120 or anti-gp120 alone did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 5). gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis in human PBL showed the same kinetics as CD4- and CXCR4-mediated cell death (data not shown), the changes in FSC/SSC typical of apoptosis and loss of membrane asymmetry preceding loss of cell viability (Fig. 5A). Likewise, activation of Giα by gp120/anti-gp120 was not observed (data not shown). Furthermore, in contrast to CD95-mediated, but in line with CD4- and CXCR4-mediated cell death, DNA was not degraded during gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5B) and activation of the known caspases was not observed (Fig. 5C).

Table 1.

Identity of apoptotic features in gp120/anti-gp120-induced and CD4-/CXCR4-mediated cell death

| Characteristics | Stimulus

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| αCD95 | αCD4 or αCXCR4 | gp120/ αgp120 | |

| DNA degradation | + | − | − |

| Kinetics (onset) | ≈2 h | ≈15 min | ≈15 min |

| Changes in FSC/SSC | + | + | + |

| Loss of membrane asymmetry | + | + | + |

| Chromatin condensation | + | + | ND |

| Cytoplasm condensation | + | + | + |

| Reduction in ΔΨm | + | + | ND |

| 7-Aminoactinomycin D positivity | + | + | ND |

| Inhibition by zVAD-fmk | + | − | − |

| Activation of Giα | − | − | − |

ND, not determined.

Figure 5.

The features of gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis in human PBL are identical to anti-CD4- or anti-CXCR4-induced apoptosis. (A) gp120/anti-gp120-induced cell death in human PBL induced changes in FSC/SSC typical of apoptosis (□). Furthermore, loss of asymmetry in plasma membrane phospholipids as determined by MC540 staining (▨) preceded loss of cell viability as determined by propidium iodide staining (■). After preincubation with 100 ng/ml gp120 (HIV-1 IIIB, Neosystem, Strasbourg, France) for 60 min at 4°C, PBL (5 × 105 cells per sample) were incubated with diluted rabbit anti-gp120 serum (1/500). Cell death was determined after 30 min. The experiment was done in triplicate and is representative of three. (B) gp120/anti-gp120-induced cell death in human PBL does not result in formation of subdiploid nuclei. Cell death was induced in activated CD95-sensitive PBL as described in A. Anti-APO-1 (10 μg/ml) was used as a positive control. Cell death of an aliquot of cells was measured by FSC/SSC analysis (104 cells counted) after 2 h (gp120/anti-gp120) or 24 h (anti-APO-1) (□). The remaining cells were incubated overnight in propidium iodide-lysis buffer and formation of subdiploid nuclei (■) was determined in a FACScan cytometer (104 cells counted) (20). The experiment shown is a representative of two experiments done. (C) gp120/anti-gp120-induced apoptosis did not involve the known caspases. Before induction of cell death as described in B human PBL were pretreated in the absence (□) or presence (■) of the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (20 μM) for 30 min at 37°C. Cell death was determined by FSC/SSC analysis 2 h (gp120/αgp120) or 24 h (αAPO-1) after induction. One experiment representative of three, done in triplicates, is shown.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported previously that the HIV-1 surface glycoprotein gp120 crosslinked by anti-gp120 Abs mediates apoptosis in infected and noninfected cells (11–13). Westendorp et al. have described that the death signal in this process is mediated by the CD95 (APO-1/Fas)/CD95L system (13). However, it was not possible to block death completely by CD95 blocking Abs or CD95 receptor decoys. gp120 binds to T cells via CD4 and CXCR4. Therefore, we investigated which of these surface receptors mediates the gp120-induced death signal. To stimulate CD4 and CXCR4 independently from each other and to induce cell death in human T cells we used CD4 and CXCR4 mAbs.

We found a rapid type of CD95-independent apoptosis in human T cells that reached a plateau in 2 h. This kind of apoptosis is induced by CD4 and CXCR4 separately, because CD4+ or CXCR4+ transfectants are killed by either mAb and down-regulation of CXCR4 in CD4+CXCR4+ HPB-ALL cells inhibited only CXCR4-mediated cell death.

Induction of cell death did not involve the signaling cascades normally initiated by CD4, CXCR4, and some of the known death receptors (p56lck, Giα, and caspase-8, respectively). In addition, we showed that cell death was not mediated by the CD95 or the TNF-R1 system, because it was not inhibited by receptor decoys and blocking Abs. Furthermore, the CD95-insensitive HPB-ALL cells were also not sensitive to TNF-α and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

CD4/CXCR4-induced cell death is independent of the known caspases and does not show cleavage of the classical “death substrate” poly(ADP-ribose). However, condensation of chromatin and cytoplasm characteristic for classical apoptosis have also been found in CD4/CXCR4-induced apoptosis described here. Other enzymes or caspases may exist that serve as executioners of cell death and might cause destruction of the cytoskeleton. Whether the caspase substrates fodrin and lamin (34) are cleaved during CD4- and CXCR4-mediated cell death should be investigated in the future. In fact, other groups have described caspase-independent activation-induced cell death mediated by CD45 or MHC class I (35, 36).

Oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation by endonucleases (DNA ladder) was also not observed in CD4/CXCR4-mediated apoptosis. DNA fragmentation is the hallmark of classical apoptosis but is not essential for cellular destruction. Thus, cytoplasts (cells without nuclei) can undergo apoptotic cell death and show the characteristic features of loss of plasma membrane asymmetry and cytoplasm condensation (37). This is in line with the lack of DNA fragmentation in our experiments and the fact that apoptosis was not impaired.

Several types of apoptosis have been described (blebbing, shrinking, autophagolysosomal, and nonlysosomal type of apoptosis, etc.; ref. 38). All have important common physiological features: the integrity of the plasma membrane and exposure of phosphatidylserine on the outer plasma membrane. These residues, normally located on the inner plasma membrane in healthy cells, may promote phagocytosis by macrophages (22). The described CD4/CXCR4-mediated cell death shows the same characteristics and can therefore be regarded as “apoptosis.”

In addition, CD4/CXCR4-mediated apoptosis shows reduction of ΔΨm, an early event during apoptotic cell death (21). This finding is in line with recent publications that demonstrate release of cytochrome c from mitochondria as a prerequisite for events leading to apoptosis (39).

In addition to the known caspases the signaling molecules associated with CXCR4 and CD4, Giα (30) and p56lck, respectively, were not activated during CXCR4/CD4-mediated apoptosis. p56lck, a T cell-specific src kinase, is not found in the human B lymphoma cells BJAB (28). Transfected with CD4, these cells, however, underwent apoptosis upon crosslinking of CD4 receptors. In addition, as shown by a GTP[γ-35S] binding assay, the natural ligand of CXCR4, SDF-1, activated Giα. This GTPase, however, was not activated during receptor stimulation by anti-CD4, anti-CXCR4, and gp120/anti-gp120. Whether other recently discussed G proteins, Gαq, or Gα12, play a role in CXCR4 signaling (40) remains to be investigated.

Here we show that single CD4+ or CXCR4+ transfectants transduce the death signal. Therefore, the death signals transmitted by CD4 or CXCR4 are most probably independent of each other. In the context of CD4, CXCR4, however, may be the only receptor capable of transducing a death signal. In single CD4 transfectants other chemokine receptors, e. g. CCR5, CCR2b, or CCR3, may substitute for CXCR4. However, whether triggering of these receptors induces cell death is as yet unknown and presently under investigation.

It is of note that gp120 and anti-gp120 Abs induce the same type of cell death in human PBL as mAbs against CD4 and CXCR4. gp120 can be found in sera of HIV-infected individuals on the surface of infected cells, on the surface of free virus, and shed from infected cells (32). In addition, the host generates anti-gp120 Abs as an immune response to the virus (33). Therefore, requirements for the described rapid type of cell death in vivo are fulfilled. The potency of this phenomenon in vitro and its specificity for CD4+ T cells would suggest that it might play a significant role in T helper cell depletion in AIDS.

Direct infection of T cells with HIV-1 has been shown to lead to caspase-mediated apoptosis (41, 42). In addition, infected cells rapidly induced DNA fragmentation in noninfected bystander cells by gp120-CD4-interaction (43, 44). Because DNA fragmentation and caspase activation are not observed in the system described here, the mechanisms used for apoptosis are probably different. Recently, it has been demonstrated that HIV-1 at a high infection rate also directly kills CD4+ T cells by a CD95-independent apoptotic mechanism in vitro (45). Whether this mechanism and the mechanism described here are identical should be investigated in the future.

Because binding of HIV-1 gp120 to CD4 and CXCR4 leads to infection, infection by the virus and induction of apoptosis with gp120 (and anti-gp120) via CD4 and CXCR4 may have different quantitative requirements with respect to gp120. We assume that infection mainly occurs with low amounts of virus whereas induction of apoptosis may require more crosslinking of the binding receptors and hence more gp120 (and anti-gp120) protein. In addition, in contrast to CD45R0-positive T cells, CD45RA-positive T cells are not sensitive to CD4/CXCR4-mediated apoptosis (E. Ritsou, German Cancer Research Center, personal communication). Because the amount of CD45R0-positive T cells increases during disease progression, the sensitivity of these cells might contribute to massive loss of CD4-positive T cells in the late phase of the disease and T cell populations that can be infected or that can be killed by CD4/CXCR4-mediated apoptosis may not entirely overlap.

In any case, our data show that engagement of CD4 or CXCR4 may initiate an efficient and rapid destruction of CD4+ T cells. Thus, the use of anti-chemokine receptor mAbs to prevent HIV-1 infection, might be dangerous. The natural ligand of CXCR4, SDF-1, or its derivatives, however, might be considered for therapy, because they inhibit both infection and CXCR4-mediated apoptosis. The elucidation of the apoptotic signaling cascade triggered by CD4 and CXCR4, therefore, might prove to be useful to identify therapeutic strategies aimed at intervening with the progressive loss of CD4+ T cells in HIV-1-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Peter and C. Scaffidi for help with the caspase experiments; Drs. A. Ehret, S. Mariani, and H. Walczak for helpful discussions; M. Baggiolini for SDF-1; W. Kolanus for pCDM8-CD4; M. Moulard for pcDNA3-tag-CXCR4; G. Moldenhauer for anti-CD4 Abs; and V. Bosch for anti-gp120 rabbit serum. We also thank E. Rieser and M. Giaisi for technical assistance. This work was funded by an AIDS grant from the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Luft- und Raumfahrt to P.H.K.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ΔΨm

mitochondrial transmembrane potential

- FSC

forward scatter

- HPB-ALL

human peripheral blood-acute lymphatic leukemia

- Abs

antibodies

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- SSC

side scatter

- zVAD-fmk

benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-(O-methyl)-fluoromethyl ketone

- GTP[γ-35S]

guanosine 5′-O-(γ-[35S]thiotriphosphate)

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

References

- 1. Fauci A S. Science. 1988;239:617–622. doi: 10.1126/science.3277274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heeney J L. Immunol Today. 1995;16:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gougeon M L, Lecoeur H, Dulioust A, Enouf M G, Crouvoisier M, Goujard C, Debord T, Montagnier L. J Immunol. 1996;159:3509–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkel T H, Tudor-Williams G, Banda N K, Cotton M F, Curiel T, Monks C, Baba T W, Ruprecht R M, Kupfer A. Nat Med. 1995;1:129–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groux H, Torpier G, Monte D, Mouton Y, Capron A, Ameisen J C. J Exp Med. 1992;175:331–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyaard L, Otto S A, Jonker R R, Mijnster M J, Keet R P M, Miedema F. Science. 1992;257:217–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1352911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gougeon M L, Garcia S, Heeney J, Tschopp R, Lecoeur H, Guetard D, Rame V, Daguet C, Montagnier L. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:553–563. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debatin K-M, Fahrig-Fraissner A, Enenkel-Stoodt S, Kreuz W, Benner A, Krammer P H. Blood. 1994;83:3101–3103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katsikis P D, Wunderlich E S, Smith C A, Herzenberg L A, Herzenberg L A. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2029–2036. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bäumler C B, Böhler T, Herr I, Benner A, Krammer P H, Debatin K-M. Blood. 1996;88:1741–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banda N K, Bernier J, Kurahara D K, Kurrle R, Haigwood N, Sekaly R-P, Finkel T H. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1099–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurent-Crawford A G, Krust B, Riviere Y, Desganges C, Muller S, Kieny M P, Dauguet C, Hovanessian A G. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:761–773. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westendorp M O, Frank R, Ochsenbauer C, Stricker K, Dhein J, Walczak H, Debatin K-M, Krammer P H. Nature (London) 1995;375:497–500. doi: 10.1038/375497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Orilkowski T, Dudhane A, Mittler R, Blum M, Lacy E, Hoffmann M K, Riethmüller G. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1553–1557. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivey-Hoyle M, Culp J S, Chaikin M A, Hellmig B D, Matthews T J, Sweet R W, Rosenberg M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:512–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. Science. 1996;272:872–877. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrera A C, Sanchez-Madrid F, Lopez-Botet M, Bernabeu C, De Landazuri M O. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:179–186. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endres M J, Clapham P R, Marsh M, Ahuja M, Turner J D, McKnight A, Thomas J F, Stoebenau-Haggarty B, Choe S, et al. Cell. 1996;87:745–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trauth B C, Klas C, Peters A M J, Matzku S, Möller P, Falk W, Debatin K-M, Krammer P H. Science. 1989;245:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.2787530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci M C, Grignani F, Riccardi C. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, Zanin C, Vayssière J-L, Petit P X, Kroemer G. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1661–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadok V A, Voelker D R, Campbell P A, Cohen J J, Bratton D L, Henson P M. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier J L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Schwartz O, Heard J M, Clark-Lewis I, et al. Nature (London) 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amara A, Le Gall S, Schwartz O, Salamero J, Montes M, Loetscher P, Baggiolini M, Virelizier J-L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F. J Exp Med. 1997;186:139–146. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Möpps B, Frodl R, Rodewald H-R, Baggiolini M, Gierschik P. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2102–2112. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mariani S M, Matiba B, Armandola E A, Krammer P H. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:221–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carbonari M, Cibati M, Cherichi M, Sbarigia D, Pesce A M, Dell’Anne L, Modica A, Fiorilli M. Blood. 1994;83:1268–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perlmutter R M, Marth J D, Lewis D B, Peet R, Ziegler S F, Wilson C B. J Cell Biochem. 1988;38:117–126. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240380206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bleul C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. Nature (London) 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanabe S, Heesen M, Yoshizawa I, Berman M A, Luo Y, Bleul C C, Springer T A, Okuda K, Gerard N, et al. J Immunol. 1997;159:905–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuang T-H, Hahn K M, Lee J-D, Danley D E, Bokoch G M. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1687–1698. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyaizu N, McCloskey T W, Coronesi M, Chirmule N, Kalyanaraman V S, Pahwa S. Blood. 1993;82:3392–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallarda J L, Henrard D R, Liu D, Harrington S, Stramer S L, Valinsky J E, Wu P. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2379–2384. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2379-2384.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan X, Wang J Y J. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lesage S, Steff A-M, Philippoussis F, Pagé M, Trop S, Mateo V, Hugo P. J Immunol. 1997;159:4762–4771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skov S, Klausen P, Claesson M H. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1523–1531. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulze-Osthoff K, Walczak H, Dröge W, Krammer P H. Cell Biol. 1994;127:15–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zakeri Z, Bursch W, Tenniswood M, Lockshin R A. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou H, Henzel W J, Liu X, Lutschg A, Wang X. Cell. 1997;90:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maghazachi A A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:270–274. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glynn J M, McElligott D L, Mosier D E. J Immunol. 1996;157:2754–2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chinnaiyan A M, Woffendin C, Dixit V M, Nabel G J. Nat Med. 1997;3:333–337. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardelli B, Gonzalez C J, Schechter M, Valentine F T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7312–7316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maldarelli F, Sato H, Berthold E, Orenstein J, Martin M A. J Virol. 1995;69:6457–6465. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6457-6465.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gandhi R T, Chen B K, Straus S E, Dale J K, Lenardo M J, Baltimore D. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1113–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]