Abstract

NmrA is a negative transcription-regulating protein that binds to the C-terminal region of the GATA transcription-activating protein AreA. The proposed molecular mechanism of action for NmrA is to inhibit AreA binding to its target promoters. In contrast to this proposal, we report that a C-terminal fragment of AreA can bind individually to GATA-containing DNA and NmrA and that in the presence of a mixture of GATA-containing DNA and NmrA, the AreA fragment binds preferentially to the GATA-containing DNA in vitro. These observations are consistent with NmrA acting by an indirect route, such as by controlling entry into the nucleus. Deletion of the final nine amino acids of a C-terminal fragment of AreA does not affect NmrA binding. Wild-type NmrA binds NAD+(P+) with much greater affinity than NAD(P)H, despite the lack of the consensus GXXGXXG dinucleotide-binding motif. However, introducing the GXXGXXG sequence into the NmrA double mutant N12G/A18G causes an ~13-fold increase in the KD for NAD+ and a 2.3-fold increase for NADP+. An H37W mutant in NmrA designed to increase the interaction with the adenine ring of NAD+ has a decrease in KD of ~4.5-fold for NAD+ and a marginal 24% increase for NADP+. The crystal structure of the N12G/A18G mutant protein shows changes in main chain position as well as repositioning of H37, which disrupts contacts with the adenine ring of NAD+, changes which are predicted to reduce the binding affinity for this dinucleotide. The substitutions E193Q/D195N or Q202E/F204Y in the C-terminal domain of NmrA reduced the affinity for a C-terminal fragment of AreA, implying that this region of the protein interacts with AreA.

Keywords: NmrA, site-directed mutagenesis, biocalorimetry, nitrogen metabolite repression

Neurospora crassa, Aspergillus nidulans, and other ascomycetous fungi are able to utilize a wide array of nitrogen sources, and many of the pathways involved are regulated at the level of transcription by pathway-specific control proteins. When the preferred nitrogen sources ammonium or glutamine are present in the growth medium with an alternative nitrogen source, the pathway for the nonpreferred source remains inactive. This situation is known as nitrogen metabolite repression, and the alternate nitrogen utilization pathway is said to be repressed (Wilson and Arst 1998). These observations show that there is a signal transduction pathway that responds to the presence of ammonium/glutamine and targets the control of transcription of the genes involved in nitrogen metabolism.

Two major classes of mutant affecting nitrogen metabolite repression have been described. The first class, exemplified by the nmr-1 and nmrA genes of N. crassa and A. nidulans, respectively, has a partially derepressed phenotype (Dunn-Coleman et al. 1979; Andrianopoulos et al. 1998), implying that they act as negative transcription regulators. The second class is represented by the nit-2 and areA genes of N. crassa and A. nidulans, respectively, and they encode the GATA-binding proteins NIT2 and AreA. These proteins contain single zinc fingers and are required for stimulation of transcription of genes controlled by nitrogen metabolite repression (Grove and Marzluf 1981; Davis and Hynes 1987; Fu and Marzluf 1990; Marzluf 1997; Rutter et al. 2001). Loss-of-function mutants are unable to use non-preferred nitrogen sources, and are said to have a repressed phenotype, in contrast to the wild-type repressible phenotype.

We previously reported the structures of the unliganded wild-type form of the nmrA-encoded NmrA protein, as well as complexes with NAD+ and NADP+ (Nichols et al. 2001; Stammers et al. 2001). Structural comparisons revealed that NmrA has an unexpected similarity to the short-chain dehydrogenase-reductase (SDR) superfamily (Stammers et al. 2001), with the closest relationship to UDP-galactose-4-epimerase (UDP-GE). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments showed that NmrA binds NAD+ and NADP+ with similar affinity but has a greatly reduced affinity for NADH and NADPH. The structure of NmrA in a complex with NADP+ has shown how repositioning a His 37 side-chain allows the different conformations of NAD+ and NADP+ to be accommodated (Lamb et al. 2003). The ability of NmrA to discriminate between the oxidized and reduced forms of the dinucleotides may be linked to a possible role in redox sensing. ITC has demonstrated that NmrA and a C-terminal fragment of the GATA transcription factor AreA interact with a 1:1 stoichiometry and an apparent KD of 0.26 μM. The presence of NAD(P)+ does not significantly affect the strength of the interaction between NmrA and the C-terminal fragment of AreA; moreover, ITC, DSC, and circular dichroism (CD) experiments were unable to find any evidence that NmrA could bind the nitrogen metabolite repression-signaling molecules ammonium or glutamine (Lamb et al. 2003).

The molecular mechanism of the signal transduction pathway responsible for nitrogen metabolite repression in A. nidulans includes control of mRNA stability mediated through the 3′ untranslated region of the areA mRNA and AreA-dependent remodeling of chromatin domains (Barredo et al. 1989; Platt et al. 1996; Muro-Pastor et al. 1999). In vitro, the nmr1-encoded N-terminally deleted forms of NMR1 protein bind directly to the zinc finger region and the extreme C terminus of NIT2 (DeBusk and Ogilvie 1984; Young and Marzluf 1991; Xiao et al. 1995; Muro-Pastor et al. 1999). The interactions were demonstrated using the yeast two-hybrid system, EMSA, and column binding techniques using 6-His- and GST-tagged fragments of the NIT2 protein as bait. These latter observations have formed the experimental basis for a model in which NMR1/NmrA are proposed to exert their transcription-repressing affect by inhibiting NIT2/AreA binding to DNA in the presence of free glutamine in the cell (Xiao et al. 1995; Muro-Pastor et al. 1999).

Here we report that (1) a C-terminal fragment of AreA can bind individually to GATA-containing DNA and NmrA, and (2) that in the presence of a mixture of GATA-containing DNA and NmrA, the AreA fragment binds preferentially to the GATA-containing DNA in vitro. In order to further understand the putative redox sensing ability of NmrA, we report the characterization of four mutant NmrA proteins that are either up- or down-modulated in their ability to bind NAD+ without compromising their ability to bind a C-terminal fragment of AreA in vitro. We also report that in contrast to previous predictions, deletion of the final nine C-terminal amino acids of a C-terminal fragment of AreA does not reduce the affinity for NmrA. However, some mutations in the C-terminal domain of NmrA do reduce the affinity of the interaction between NmrA and a C-terminal fragment of AreA.

Results

AreA662 protein preferentially binds to GATA-containing DNA in the presence of NmrA

Using the independent techniques of fluorescence polarization (FP) and ITC, we wished to determine whether a C-terminal fragment of AreA (designated AreA662) could bind to GATA-containing DNA in the presence of NmrA. We chose to use as targets for the AreA662 protein GATA-containing sequences from the niaD-niiA intergenic region of A. nidulans. In A. nidulans, the genes encoding nitrate reductase (niaD) and nitrite reductase (niiA) are transcribed divergently, and this region has been used as a model system for studying the control of transcription of genes subject to nitrogen metabolite repression (Johnstone et al. 1990; Punt et al. 1991, 1995). Four GATA sites (numbers 5–8) out of a total of 10 in this promoter region are responsible for ~80% of the transcriptional activity and are situated in a pre-set nucleosome-free region (Muro-Pastor et al. 1999). In the presence of nitrate and the absence of ammonium or glutamine, these genes are transcribed; however, in the absence of nitrate or the presence of a mixture of nitrate and/or ammonium/glutamine, transcription is repressed. Transcription of these genes is under the specific control of the NirA activator, which has been proposed to interact with AreA (Narendja et al. 2002).

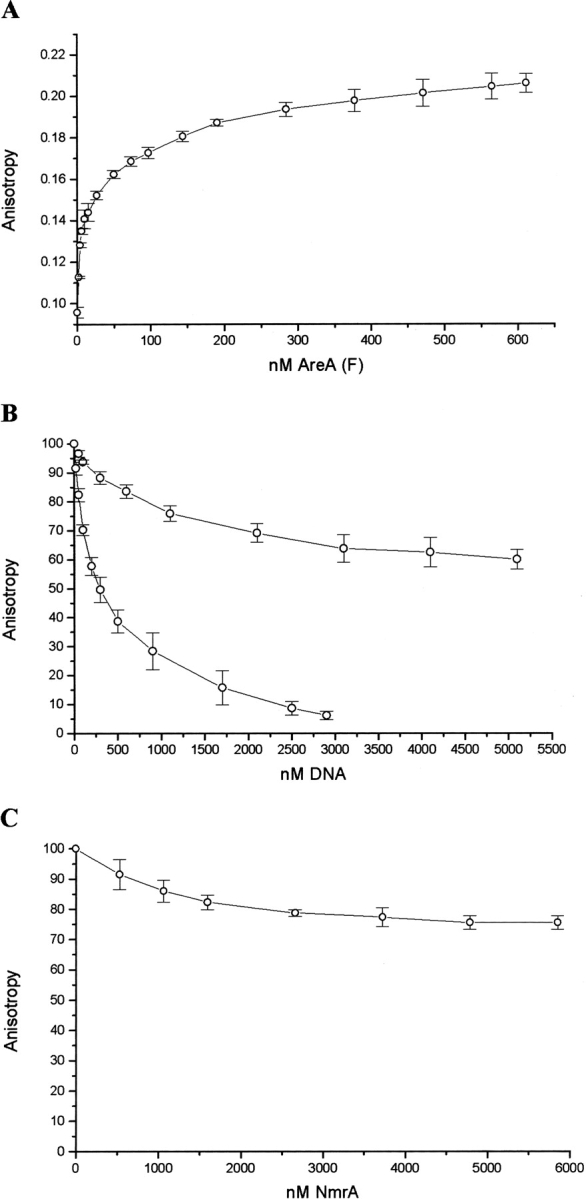

We used a fluorescently labeled double-stranded (ds) oligonucleotide containing GATA site 5 as the target DNA in an FP assay (described in Materials and Methods). The FP experiments showed that AreA662 interacted with the fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide and that adding back nonfluorescently labeled DNA containing GATA site 5 competes out this binding (Fig. 1A,B ▶). In order to confirm whether the interaction between the C-terminal fragment of AreA and DNA is GATA-dependent, we used a mutant ds-oligonucleotide of the same overall nucleotide composition but with the GATA site 5 changed to GTAA, in competition experiments (Fig. 1B ▶). Figure 1B ▶ shows that 2.9 μM GATA-containing DNA was able to compete off ~95% of the fluorescently labeled DNA, whereas at a concentration of 5 μM the non-GATA-containing DNA had only competed off ~40%. These data demonstrate that the interaction of AreA662 with DNA is significantly GATA-dependent. The data shown in Figure 1B ▶ do not fit to a simple 1:1 binding model, and therefore we were unable to determine the binding constants. Equivalent ITC experiments (see below and Fig. 2A ▶) confirmed that the binding of AreA662 with DNA did not fit to a simple 1:1 binding model.

Figure 1.

Analysis of AreA662 binding to GATA site 5 determined by a fluorescence anisotropy assay. (A) The direct titration of HEX-labeled GATA site 5 (prepared by annealing oligonucleotides 519 and 523) with AreA662. The concentration of ds-oligonucleotide was 5 nM. (B) AreA662 (150 nM) binding to Hex-labeled GATA site 5 (75 nM, and made by annealing oligonucleotides 519 and 523) in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled GATA site 5 (lower trace) or unlabeled mutant (GTAA) GATA site 5 (upper trace). GATA site 5 was made by annealing oligonucleotides 522 and 523, and the mutant (GTAA) site 5 was made by annealing oligonucleotides 524 and 525. (C) AreA662 binding to GATA site 5 in the presence of NmrA. Increasing concentrations of NmrA up to 6 μM were added to a preformed complex of AreA662 (150 nM) and HEX-labeled GATA site 5 DNA (75 nM). Data points in all cases were plotted using Origin 5 software and represent the average of three experiments with standard error bars.

Figure 2.

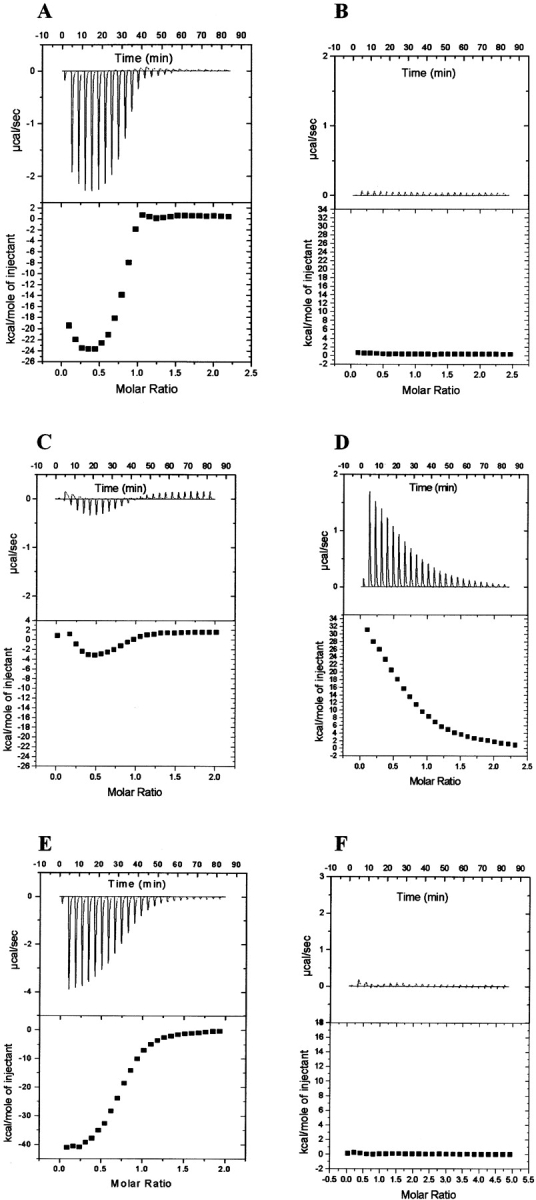

Isothermal titration thermograms showing the binding responses of NmrA to AreA662 in the presence and absence of DNA. (A) The heat exchange associated with the titration of ds-oligonucleotides containing GATA site 9 into a solution of AreA662. (B) The heat exchange associated with the addition of NmrA into a mixture of AreA662 previously titrated with GATA site 9. (C) The heat exchange associated with the titration of ds-oligonucleotides containing mutant GATA site 5 into AreA662. (D) The heat exchange associated with the addition of NmrA to the mixture of AreA662 and mutant GATA site shown in C. (E) The heat exchange associated with addition of ds-oligonucleotides containing GATA site 9 to AreA662 previously titrated with NmrA. (F) The heat exchange associated with the titration of GATA site 9 into NmrA.

To determine whether NmrA could bind to a preformed complex of AreA662 (150 nM) and Hex-labeled GATA site 5-containing DNA (75 nM), increasing concentrations of NmrA were added up to a molar excess of ~35-fold, and the fluorescence anisotropy signal was measured. The resulting data are summarized in Figure 1C ▶, where it can be seen that concentrations of NmrA up to 5.9 μM (~23× the KD for the AreA662:NmrA interaction) the anisotropy signal was reduced by ~24%. The finding that the anisotropy signal was reduced rather than increased indicates that under these conditions the NmrA did not bind to the complex of AreA662/GATA site 5 DNA. Furthermore, the modest reduction in the anisotropy signal (24%) shows that under these conditions the majority of AreA662 remained in a complex with GATA site 5-containing DNA. Similar results were seen when the titrations were then repeated in the presence of a final concentration of 1 mM NAD+ to see whether the oxidized nucleotide affected the binding of AreA662 to NmrA in the presence of the GATA-containing DNA. These results contrast with the data reported for the NMR1/NIT2 proteins of N. crassa (Xiao et al. 1995); therefore, we checked the finding by using an independent assay based on the technique of ITC.

In separate experiments with the same stock of AreA662, we titrated a ds-oligonucleotide containing either GATA site 9 or site 5 into a fixed concentration of AreA until the reaction had gone to completion, thereby capturing the AreA662 in a complex with the GATA-containing ds-oligonucleotide (Fig. 2A ▶). The data in Figure 2A ▶ were generated using GATA site 9 and do not fit a simple 1:1 binding model, and therefore they independently verify the observation from the FP assay described above. Similar data were observed when GATA site 5 was used. NmrA was then titrated onto this mixture but caused no additional heat exchange above background, indicating that NmrA was not binding to AreA in the presence of the GATA-containing ds-oligonucleotide (Fig. 2B ▶). We repeated these experiments using a mutant oligonucleotide that has the same base composition as GATA site 5, but has the GATA site changed to GTAA (Table 1). Figure 2C ▶ shows that this oligonucleotide when titrated into AreA662 showed a complex and much smaller heat exchange compared to Figure 2A ▶, consistent with weak nonspecific binding. When NmrA was titrated into this mixture, the increased heat exchange shown in Figure 2D ▶ was seen. It is possible that the weak nonspecific binding to AreA662 revealed by the use of this non-GATA-containing ds-oligonucleotide is responsible for the inability to fit the data shown in Figures 1B ▶ and 2A ▶ to a simple 1:1 binding model.

Table 1.

Sequences of synthetic oligonucleotides

| Number | Plasmid number | Mutation | AreA662 substrate | Sequence |

| 427 | pRF92 | AreA662Δ9 | 5′CTGGCTTGCGCCCTGACCAGC3′ | |

| 428 | pRF92 | AreA662Δ9 | 5′TAAGCTTGATCCGGCTGCTAAC3′ | |

| 487 | pTR170 | N12G/A18G | 5′ATCGCCGTCGTCGGCGCGACGGGGCGCCAGGGCGCTTCGCTC3′ | |

| 488 | pTR170 | 5′TGTCTTCTTTTGCTGGGCCAT3′ | ||

| 502 | pTR172 | E263Q/E266Q | 5′CGGGAACAGCTTCAGGCCATCCAGGTGGTCTTCGGT3′ | |

| 503 | pTR172 | 5′GTACCCGACTGGAATGTTGAC3′ | ||

| 498 | pTR188 | Q202E/F204Y | 5′CCGGCGCTGCTGGAGATTTACAAAGACGGGCC3′ | |

| 499 | pTR188 | 5′GCCGACGTCATGCTCTGCATC3′ | ||

| 513 | pTR189 | T14V | 5′GTCGTCAACGCGGTGGGGCGCCAGGCC3′ | |

| 514 | pTR189 | 5′GGCGATTGTCTTCTTTTGCTG3′ | ||

| 517 | pTR184 | H37W | 5′CGCGCGCAGGTCTGGTCACTCAAGGGC3′ | |

| 518 | pTR184 | 5′CACATGATGTCCGACGGCCGC3′ | ||

| 531 | pTR191 | E193Q/D195Q | 5′TGGCTAGATGCACAGCATAACGTCGGCCCGGCGCTG′ | |

| 533 | pTR191 | AGGCAGCGGGATGCTCGGGTCAAA | ||

| 519 | GATA site 5 | 5′ (HEX)TCCCACCAGAGATAAGAGATT3′ | ||

| 522 | GATA site 5 | 5′TCCCACCAGAGATAAGAGATT3′ | ||

| 523 | GATA site 5 | 5′AATCTCTTATCTCTGGTGGGA3′ | ||

| 524 | Mutant GATA site 5 | 5′TCCCACCAGAGTAAAGAGATT3′ | ||

| 525 | Mutant GATA site 5 | 5′AATCTCTTTACTCTGGTGGGA3′ | ||

| 528 | GATA site 9 | 5′CCCTATACTATCTAATCGACC3′ | ||

| 529 | GATA site 9 | 5′GGTCGATTAGATAGTATAGGG3′ |

We titrated NmrA onto a fixed concentration of AreA662 (33 μM) until the reaction had gone to completion and the AreA662 was saturated with NmrA (Table 2). A ds-oligonucleotide containing GATA site 9 was then titrated onto this preformed AreA662/NmrA complex, and the resulting heat exchange is shown in Figure 2E ▶. As a control (Fig. 2F ▶), we titrated GATA site 9 onto NmrA and found a minimal heat exchange above the background heat of dilution, indicating that NmrA was unable to bind this DNA, or if it does bind, it does so with zero heat (ΔH=0). As a positive control to check that the stocks of NmrA and AreA662 used still interacted as previously published (KD 3 0.26 μM), we titrated NmrA onto AreA662 and determined the KD for the interaction as 0.25 μM (see Tables 3,4).

Table 2.

The binding of AreA662 to NmrA in the presence of DNA as determined by ITC at 25°C

| Panel | Injector | Cell |

| A | 354 μM GATA site 9 | 33 μM AreA662 |

| B | 440 μM NmrA | 33 μM AreA662 previously titrated with 354 μM GATA site 9 |

| C | 359 μM mutant GATA site 5 | 33 μM AreA662 |

| D | 465 μM NmrA | AreA662 previously titrated with mutant GATA site 5 |

| E | 354 μM GATA site 9 | 33 μM AreA662 previously titrated with 440 μM NmrA |

| F | 360 μM site 9 | 30 μM NmrA |

The binding of AreA662 to NmrA both in the presence and absence of ds oligonucleotides was measured by ITC at the concentration indicated. ‘Panel’ indicates the reagents used in each of the corresponding panels shown in Figure 2 ▶.

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of wild-type and mutant NmrA to dinucleotides as determined by DSC

| Protein | Ligand | Tm°C | ΔHcal kJ mol−1 | ΔHv kJ mol−1 | KD (mM) |

| Wild type | — | 48.0 (0.3) | 690 (66) | 720 (47) | — |

| NAD+ | 51.6 (0.1) | 720 (62) | 700 (46) | 0.19 (0.07) | |

| NADH | 49.3 (0.5) | 710 (81) | 710 (38) | 2.0 (0.9) | |

| NADP+ | 49.7 (0.1) | 730 (56) | 720 (49) | 1.0 (0.3) | |

| NADPH | 48.6 (0.4) | 740 (39) | 720 (58) | 6.4 (2.9) | |

| E263Q/E266Q | — | 45.1 (0.1) | 610 (11) | 580 (17) | |

| NAD+ | 49.5 (0.1) | 650 (23) | 620 (10) | 0.14 (0.01) | |

| NADH | 46.7 (0.1 | 660 (10) | 630 (10) | 1.5 (0.06) | |

| NADP+ | 47.6 (0.1) | 650 (11) | 630 (2.4) | 0.58 (0.04) | |

| NADPH | 45.6 (0.1) | 630 (2) | 620 (6) | 11 (2.4) | |

| N12G/A18G | — | 45.1 (0.1) | 700 (23) | 700 (10) | — |

| NAD+ | 46.0 (0.3) | 700 (21) | 700 (12) | 3.1 (1.7) | |

| NADH | 45.4 (0.1) | 720 (19) | 700 (9) | 1 (1.4) | |

| NADP+ | 46.0 (0.1) | 720 (4) | 710 (17) | 2.8 (0.3) | |

| NADPH | 45.6 (0.1) | 700 (27) | 730 (15) | 6.4 (1.3) | |

| T14V | — | 46.9 (0.1) | 670 (30) | 660 (9) | — |

| NAD+ | 49.0 (0.1) | 710 (12) | 660 (24) | 0.73 (0.06) | |

| NADH | 47.4 (0.2) | 700 (27) | 670 (4.2) | 8.2 (3.5) | |

| NADP+ | 47.4 (0.1) | 670 (9) | 670 (2.4) | 7.4 (0.4) | |

| NADPH | 47.1 (0.1) | 680 (13) | 670 (13) | 17 (3.7) | |

| E193Q/D195N | — | 38.0 (0.4) | 443 (13) | 490 (8) | — |

| NAD+ | 43.8 (0.1) | 573 (17) | 557 (13) | 0.14 (0.03) | |

| NADH | 40.9 (0.3) | 498 (41) | 557 (16) | 0.80 (0.15) | |

| NADP+ | 42.0 (0.1) | 577 (29) | 581 (21) | 0.80 (0.15) | |

| NADPH | 40.7 (0.5) | 561 (17) | 552 (1) | 0.88 (0.12) | |

| Q202E/F204Y | — | 45.2 (0.1) | 603 (21) | 590 (50) | — |

| NAD+ | 49.2 (0.1) | 640 (8) | 615 (8) | 0.19 (0.03) | |

| NADH | 46.8 (0.2) | 649 (58) | 632 (42) | 1.5 (0.36) | |

| NADP+ | 47.0 (0.1) | 611 (33) | 623 (42) | 1.13 (0.6) | |

| NADPH | 45.7 (0.1) | 627 (29) | 615 (17) | 7.8 (2.06) |

The binding of NmrA dinucleotides was measured in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT. NmrA was used in the concentration range 16.1 to 25 μM, and dinucleotides were used at a concentration of 3 mM. Shown are the values for Tm, the mid-point of the thermal transition; KD, the equilibrium dissociation constant; ΔHcal, the calorimetric enthalpy and Δ Hv, the van’t Hoff enthalpy. The values shown are the average (rounded to two significant figures) of three independent determinations. Standard deviation is in parentheses.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of wild-type and mutant NmrA to AreA662, AreA662Δ9and dinucleotides as determined by ITC at 25°C

| NmrA | ||||||

| AreA662 | wild-type | N12G/A18G | E263Q/E266Q | H37W | T14V | Q202E/F204Y |

| n | 1.1 (0.14) | 1.1 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 1.2 | 1.10 | 1.02 (0.07) |

| KD (μM) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.40 (0.04) | 0.18 (0.04) | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.63 (0.08) |

| Δ Hobs (kJ mol−1) | 89 (10.3) | 68.2 (1.2) | 47.5 (2.4) | 84 | 88 | 84 (3) |

| ΔS° (J K−1 mol−1) | 425 (35) | 351.4 (3.1) | 288 (6.4) | 405.7 | 422.3 | 96 (2) |

| c | 141 (30) | 87 (16) | 168 (29) | 134 | 174 | 61 (13) |

| Sample size | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| AreA662Δ9 | NmrA Wild-type |

| n | 0.98 (0.01) |

| KD (μM) | 0.26 (0.01) |

| Δ Hobs (kJ mol−1) | 95 (1) |

| ΔS° (J K−1 mol−1) | 443 (3) |

| c | 100 (4) |

| Sample size | 3 |

| NmrA | ||

| NAD | Wild-type | H37W |

| n | 0.94 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.05) |

| KD (μM) | 72.7 (1.5) | 16.9 (1.9) |

| Δ Hobs (kJ mol−1) | −27.9 (2.3) | −22.9 (2.4) |

| ΔS° (J K−1 mol−1) | −14.8 (7.4) | 14.6 (8.6) |

| c | 1.1 | 3.9 (0.8) |

| Sample size | 3 | 7 |

| NmrA | ||

| NADP | Wild-type | H37W |

| The binding of NmrA to AreA662, AreA662Δ9, NAD+ and NADP+ was measured in 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT by ITC. NmrA was used in the concentration range 262–540 μM, and NAD(P)+ was used in the concentration range 1–4 mM. Shown are the values for n, the stoichiometry of binding; KD, the equilibrium dissociation constant; ΔHobs, the observed enthalpy; and ΔS°, the standard enthalpy change for single site binding. The cg values fall within the range 1–1000 that allows the isotherms to be accurately deconvoluted to derive K values (Wiseman et al. 1989). The data set for the wild-type NmrA contains information previously published in Tables II and III in Lamb et al. (Stammers et al. 2001). The values shown are the average; standard deviation is shown in parentheses. As protein concentrations were estimated by the method of Gill and von Hippel (1989), the concentrations measured will have an error of up to 5%. Additionally both the active and any inactive fraction of the protein being measured will be included in the calculation. Therefore the values of n shown are subject to this error, and the standard error shown is a mathematical calculation based on the number of replicate measurements indicated. | ||

| n | 1.1 (0.07) | 1.1 (0.06) |

| KD (μM) | 109.5 (13.4) | 137 (2.6) |

| Δ Hobs (kJ mol−1) | −48.7 (2.1) | −52.1 (1.4) |

| ΔS° (J K−1 mol−1) | −87.7 (5.9) | −100.7 (4.8) |

| c | 1.9 (0.07) | 1.5 (0.06) |

| Sample size | 2 | 3 |

The data in Figure 2F ▶ show that NmrA does not bind appreciably to a GATA-containing ds-oligonucleotide; therefore the heat exchange seen in Figure 2D ▶ is most simply interpreted as arising from the binding of NmrA to the free fraction of AreA662 present in the mixture. As the amount of free AreA662 in this experiment is not known, it is not possible to determine the KD for the binding of NmrA to AreA662 in this experiment. The heat exchange seen in Figure 2E ▶ is most simply interpreted as meaning that DNA containing GATA site 9 is able to bind to AreA662 even when the AreA662 is precomplexed with NmrA. Because Figures 1C ▶ and 2B ▶ show that NmrA does not bind to a preformed AreA/GATA ds-oligonucleotide complex under the conditions used, the data imply that in the presence of increasing concentrations of GATA-containing ds-oligonucleotide, NmrA dissociates from AreA662.

Overall, the data shown in Figure 2A–F ▶ are most simply interpreted as meaning that AreA662 can bind individually to GATA-containing DNA and NmrA and that in the presence of a mixture of GATA-containing DNA and NmrA, AreA662 binds preferentially to the GATA-containing DNA. As the FP and ITC experiments were carried out in the same buffer, they are directly comparable and independently verify the conclusions drawn.

The extreme C-terminal nine amino acids of AreA662 are not required for the binding of NmrA

The C-terminal nine amino acids of AreA and its homologs (including NIT2 in N. crassa) are highly conserved across a range of filamentous fungi, and deletion mutants of areA lacking these residues have a partially derepressed phenotype (Platt et al. 1996). The yeast two-hybrid system was used to study the interaction of the C-terminal 223 residues of NIT2 with a GAL4 DNA-binding domain fused to the NMR protein. The NIT2 and NMR proteins were reported to interact in this system, and mutations that deleted or caused point mutations in the C-terminal 12 amino acids of NIT2 were reported to disrupt this interaction (Pan et al. 1997). When equivalent C-terminal mutations were made in the wild-type nit-2 gene, the mutations caused a substantial loss of nitrogen repression in vivo (Pan et al. 1997). Given these observations, we wished to test the hypothesis that the C-terminal nine amino acids of AreA662 are required for NmrA to bind.

We constructed a mutant version of AreA662 lacking the C-terminal nine amino acids, and designated the mutant protein AreA662Δ9 (Table 1). The mutant protein was purified in bulk and used in ITC experiments with NmrA, where it was found that the two proteins interacted with a 1:1 stoichiometry and KD (0.26 3M) indistinguishable from that of the interaction between NmrA and AreA662 (Table 4). Purified AreA662Δ9 was also used in FP experiments with a HEX-labeled ds-oligonucleotide containing GATA site 5 (Table 1), and was found to bind in a similar manner to AreA662 (data not shown).

Site-directed mutagenesis can up- and down-modulate dinucleotide binding to NmrA

NmrA lacks the characteristic nucleotide binding motif GXXGXXG found in related SDRs such as UDP galactose epimerase (Thoden et al. 2001), having instead the sequence NXXGXXA. The crystal structures of NmrA in complexes with NAD+ and NADP+ have highlighted residues T14 and H37 as being important in the interactions with the AMP portion of NAD+. In particular, H37 ring stacks with the adenosine base of both NAD+ and NADP+ and undergoes a flip between the two complexes, and a change of H37 to W37 is predicted to result in tighter binding of NAD+. To test this hypothesis and see whether it is possible to modulate nucleotide binding without compromising AreA662 binding, we made three mutations in the Rossman fold and three in the C-terminal domain of NmrA. Table 1 summarizes the details of the mutants constructed. The dinucleotide binding properties of the various mutant proteins were compared to the wild-type protein by DSC analysis or in one case by ITC analysis, and AreA662 binding properties were analyzed by ITC. Although the DSC unfolding transitions are irreversible under the conditions used, the ratio of calorimetric to van’t Hoff enthalpies is close to unity (Table 3) and is consistent with cooperative unfolding of a monomeric protein unit. The properties of the mutant proteins are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, where it can be seen that all of the mutant proteins retained the ability to bind to AreA662 but three had altered affinities for dinucleotides compared to the wild-type.

The mutant proteins N12G/A18G and T14V have diminished affinity for dinucleotides, whereas the H37W mutant has an ~4.2-fold increase in affinity for NAD+ and essentially wild-type affinity for NADP+. This estimate of NAD affinity for the H37W mutant was measured by ITC and is a direct measure of the interaction under the buffer and temperature (25°C) conditions chosen. DSC, on the other hand, is an indirect measure of binding at an elevated temperature, and the values quoted in Table 3 derived by this technique give only a general guide to the extent of the changes in affinity for the various ligands shown by each mutant protein. ITC cannot be used to estimate the KD values of NmrA mutants with reduced affinity for oxidized nicotinamide dinucleotides compared to wild-type, as the affinity is too low to be measured by this technique. For the same reason ITC cannot be used to measure the binding of reduced dinucleotides to either wild-type or mutant NmrA. However, the protein that has a control substitution in the C-terminal domain (E263Q/E266Q) has DSC-estimated KD values for oxidized nucleotide binding that differ from the wild-type value by ~25%. This reasonable match between affinities of the C-terminal mutant and the wild-type gives confidence that the much larger apparent differences between the Rossman fold mutants and wild-type do reflect specific changes in the affinity of nucleotide binding. The DSC-estimated KD values for the binding of wild-type NmrA to NAD+ and NADP+ reported here differ by ~27% and 2.8-fold, respectively, from those previously published (Lamb et al. 2003). The differences may be due to the fact that the KD values reported here were determined in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, whereas the previously published values used potassium phosphate buffer at pH 6.6.

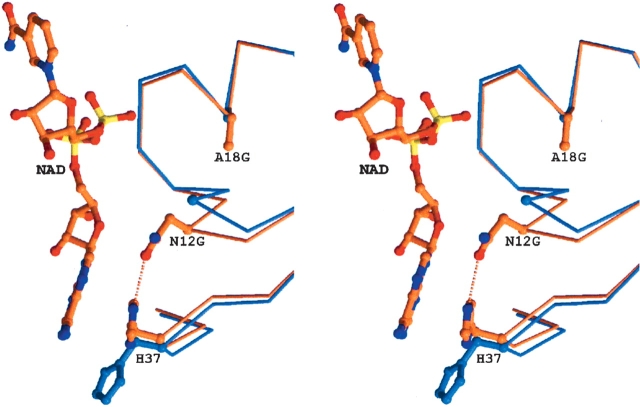

Structure of the NmrA N12G/A18G mutant protein provides a molecular explanation for the reduction in affinity for dinucleotides

As the GXXGXXG or closely related motifs are present in many Rossman fold-containing proteins, it was surprising that engineering in this sequence into NmrA resulted in a diminution of the ability to bind oxidized dinucleotides. In order to try and understand the molecular basis for this reduced affinity for oxidized dinucleotides, we determined the crystal structure of the N12G/A18G double mutant NmrA to 1.4 Å resolution. The statistics for crystallographic structure determination are shown in Table 5. The electron density map for NmrA N12G/A18G confirmed the presence of the mutations at N12G and A18G. Comparing the refined model of NmrA N12G/A18G with either unliganded NmrA or in a complex with NAD shows significant changes in main chain position in the region of the N12G mutation (Fig. 3 ▶). The CA atom of N12G is displaced by 1.9 Å compared to wild-type against an overall rmsd of 0.26 Å for all CA atoms. There is also a loss of a hydrogen-bond from the N12 amide group to His37; the latter side chain then rotates around χ1 (CA-CB atoms) away from its position in both the wild-type unliganded and NAD+-bound NmrA structures toward the conformation found in the complex of NmrA with NADP+ (Stammers et al. 2001). The movement of N12G main chain is a direct result of the A18G mutation, because there is a van der Waals contact between the A18 side chain and the carbonyl oxygen of N12 in wild-type NmrA. In NmrA N12G/A18G, the smaller bulk of G18 allows movement of the main chain in this region such that a contact with residue 18 (via the CA atom) is maintained. N12 forms van der Waals contacts with the adenine ring of NAD+ that are lost directly as a result of N12G or indirectly by the A18G mutation. Such changes together with the repositioning of H37 appear able to account for the reduced binding for NAD+. The different H37 position means that the N12-H37 hydrogen bond does not need to be broken to be correctly orientated for binding NADP+; hence this may explain the relatively lower loss of affinity for this dinucleotide to the N12G/A18G NmrA.

Table 5.

Statistics for crystallographic structure determinations

| X-ray data | |

| Space group | P3221 |

| Unit cell dimensions (a, b, c in Å) | 76.61, 76.61, 103.82 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 25.0–1.40 (1.45–1.40) |

| Unique reflections | 69,599 (6649) |

| Redundancy | 9.3 (4.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (96.2) |

| Average I/σ (I) | 36.2 (2.4) |

| Rmergea | 0.092 (0.605) |

| Refinement statistics: | |

| R-factorb (Rwork/Rfree) | 0.193/0.238 |

| No. atoms (protein/water/ion) | 2565/606/20 |

| Rms bond length deviation (Å) | 0.0070 |

| Rms bond angle deviation (°) | 1.49 |

a Rmerge = ∑|I − <I>|/∑<I>

b R-factor = ∑|Fo − Fc|/∑Fo

Outer shell data are given in parentheses.

Figure 3.

Stereo diagram showing the effect of N12G/A18G mutations on the structure of NmrA. The CA backbone of residues 8–25 and 30–40, and side chains of residues 12, 18, and 37 in the mutant structure are shown in blue. The corresponding CA backbone and side chains as well as the bound NAD+ of the wild-type NmrA-NAD+ complex are shown in orange. The H-bond between residues N12 and H37 in the wild-type NmrA-NAD+ complex is shown as a yellow dashed line. The PDB ID for this structure is 1XGK.

Mutations in the C-terminal domain of NmrA reduce the affinity for AreA662

The structure of NmrA reveals that it is composed of an N-terminal Rossman fold and a C-terminal domain proposed to be involved in binding AreA. Helix α6 forms part of the C-terminal domain, is slightly recessed but is solvent-accessible, and has a particularly long cluster of conserved residues (Stammers et al. 2001). For this reason it was suggested that the C-terminal domain of NmrA is involved in binding to AreA and that helix α6 could be directly involved in the interaction (Stammers et al. 2001). To test this hypothesis directly we made two double mutations in this helix, E193Q/D195N and Q202E/F204Y (Table 1) and compared their properties to the doubly mutant E263Q/ E266Q protein that has the mutant substitutions in helix α9. Using ITC and DSC, we tested the ability of the purified mutant proteins to bind AreA662 and dinucleotides (see Tables 3 and 4). In each case, the mutant proteins were not compromised in their ability to bind dinucleotides, and mutant Q202E/F204Y had an ~2.5-fold increase in KD for AreA662. The E193Q/D195N protein lost its ability to bind AreA662 when stored on ice for 10 d; however, the ability to bind oxidized dinucleotides was unaffected (Tables 3,4) during this time period. The ability of the Q202E/F204Y protein to bind AreA662 and oxidized dinucleotides was unaffected over this time period. The E263Q/E266Q protein was undiminished in its affinity for AreA662 and oxidized dinucleotides over the 10-d period.

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that NmrA binds to C-terminal fragments of AreA with an average KD of 0.26 μM, and we noted that two radically different models for the ability of NmrA to modulate the activity of AreA can be envisaged (Lamb et al. 2003). Firstly, NmrA may interact directly with AreA while it is complexed with DNA and disrupt its interaction with pathway-specific transcription-regulating proteins or the accessory transcription apparatus. Secondly, NmrA may exert its affect by controlling the access of AreA to its target promoters by either a direct or indirect route. The direct route could involve occlusion of the zinc finger region (Xiao et al. 1995), or it could act indirectly by controlling the rate of entry of AreA into the nucleus.

We show here for the first time that, in vitro, a C-terminal fragment of the AreA protein has its affinity for native NmrA protein greatly reduced in the presence of GATA-containing DNA. These observations are consistent with a model in which NmrA and GATA-containing DNA compete for a single or two overlapping sites in the C-terminal region of AreA (Xiao et al. 1995). This model predicts that at high molar excess NmrA should show some competition with GATA-containing DNA for the common or overlapping site on AreA. The data shown in Figure 1C ▶ are consistent with this prediction. These data contrast with the report that the homologous NMR1 protein of N. crassa inhibits the binding of NIT2 to DNA. In those experiments, the NMR1 protein was deleted for the N-terminal 46 amino acids, and the NIT2 fragment was that encoded by the nit-2 KpnI-EcoRI sequence that specifies ~326 amino acids including the zinc finger DNA-binding motif (Xiao et al. 1995). Both the NMR1 and NIT2 fragments used were GST-fusions, and it has been shown that the GST moiety of fusion proteins can dimerize (Panayotou et al. 1993; Ladbury et al. 1995). Interpretation of the reported data is therefore complicated, because any association/dissociation of the NIT2 and NMR1 fragments and their interaction with DNA will be affected by a contribution from the dimerization of the associated GST moieties. The proteins we report here are native NmrA and an N-terminally truncated AreA that contains a small (41 amino acids) pRSETb-encoded fusion sequence containing six His residues. As we previously reported, NmrA binds to C-terminal fragments of AreA and does not bind to the pRSETb-encoded N-terminal fusion sequence (Lamb et al. 2003). Therefore, the analysis of the interactions between NmrA and C-terminal AreA fragments reported here is not complicated by the potential interactions between other sequences fused to NmrA or AreA fragments.

Our results further contrast with data reported for the NIT2:NMR interaction in that we found that the C-terminal nine amino acids of AreA662 are not required for the binding of NmrA. In the N. crassa study, loss of binding between NIT2 and NMR in the yeast two-hybrid system by deleting or mutating the C-terminal 12 amino acids was correlated with a substantial loss of nitrogen repression by the equivalent mutation in vivo (Pan et al. 1997). This phenotype is similar to the partial derepression reported for areA mutants lacking the C-terminal nine amino acids. It is possible that these contrasts may be highlighting some differences in the detailed mechanism of nitrogen metabolite repression between N. crassa and A. nidulans. Alternatively, with hindsight the use of the two-hybrid system may not be optimal to study this particular interaction, as cases of false positives and false negatives have been reported and discussed (Legrain et al. 2001).

The data we present here suggest that, in vivo, NmrA does not prevent the binding of full-length AreA to its cognate promoters under conditions of nitrogen metabolite repression. This suggestion is supported by the observation that in vivo GATA site 5 is occupied by AreA even under conditions of nitrogen metabolite repression in a strain with a wild-type nmrA gene (Muro-Pastor et al. 1999). These observations imply that in vivo NmrA exerts its repressing effect on transcription by an indirect route, possibly by controlling the rate of entry of AreA into the nucleus. As NmrA can discriminate between oxidized and reduced dinucleotides (Lamb et al. 2003), it is possible that NmrA may influence the rate of entry of AreA into the nucleus in response to the redox state of the cytoplasm.

There is a precedent in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the regulation of the use of different nitrogen sources by the cytoplasmic retention of a GATA-binding transcription activating protein. S. cerevisiae has a preferred nitrogen source (glutamine) and uses this selectively by repressing GATA factor-dependent transcription of the genes needed to transport and catabolize nonpreferred sources, in a physiological process called nitrogen catabolite repression (Cox et al. 2000). In this system, GATA-dependent transcription is stimulated by the activator proteins Gln3p and Gat1p. When nitrogen is limiting, Gln3p and Gat1p are found primarily in the nucleus, but when nitrogen is in excess they are excluded from the nucleus. Nuclear exclusion of Gln3p is proposed to involve the formation of a complex between Gln3p and the NCR regulator Ure2p (Beck and Hall 1999; Cox et al. 2000; Kulkarni et al. 2001). The interaction between Gln3p and Ure2p shows an interesting parallel with the AreA/NmrA interaction, and our data suggest that control of access of nutrient-regulated transcription factors to the nucleus by cytoplasmic proteins may be a more widespread mechanism than previously realized.

The program of site-directed mutagenesis we report here shows that it is possible to up- and down-modulate the affinity of NmrA for oxidized dinucleotides without affecting the ability of the mutant NmrA to bind to AreA662. Similarly, it proved possible to reduce the affinity of NmrA for AreA662 without significantly reducing the ability of the mutant proteins to bind oxidized dinucleotides. Surprisingly, the introduction of the classic GXXGXXG motif into the Rossman fold of NmrA caused a diminution rather than increase in affinity for the oxidized dinucleotides. However, the molecular basis for this observation is explained by the structure of the N12G/A18G mutant protein, which shows significant changes in main chain position in the region of the N12G mutation. The change in main chain position and repositioning of the H37 side chain disrupts van der Waals/ aromatic ring stacking contacts with the adenine ring of NAD+, thus causing a reduction in binding for this nicotinamide dinucleotide.

The fact that NmrA has different sequence requirements for binding NAD+ compared to structurally related SDRs may be significant. Clearly it is less likely that NAD+ binding in NmrA is a vestigial property left over from its proposed evolution from a dehydrogenase enzyme, because the “original” SDR-like sequence binds NAD+ less tightly. Indeed, it is consistent with the view that NAD+ binding in NmrA relates to a distinctive biological role such as a redox-sensing control property rather than for a catalytic function, as is the case in SDRs. In contrast to the weakened NAD+ binding of the N12G/A18G NmrA mutant, we show that it also possible to generate a mutant with increased binding for NAD+ viz. H37W.

Helix α6 double mutant Q202E/F204Y has a modest but significant increase in the KD for the binding of NmrA and AreA662 without increasing the KD for oxidized dinucleotide binding (see Tables 3,4), and this result is consistent with helix α6 being directly involved in binding to AreA. The fact that a control mutation, E263Q/E266Q, in helix α9 does not impair AreA662 or oxidized nucleotide binding lends confidence to this interpretation. Interestingly, in DSC analysis the thermal transition midpoint temperatures (Tm) for the unliganded doubly mutant protein E193Q/D195N is dramatically lower (~10°C) than the wild-type protein (Table 3). These mutant substitutions do not increase the Km for dinucleotide binding but do have a large negative effect on AreA662 binding that increases with time. These observations imply that in the doubly mutant E193Q/D195N protein, the integrity of the Rossman fold is not compromised, and that a large effect of the mutant substitutions is on the stability of the C-terminal domain of NmrA (Stammers et al. 2001). These observations argue strongly that the C-terminal domain of NmrA is responsible for the interaction with AreA662, and that the two domains of NmrA function independently.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from local suppliers and were of AnalaR or greater purity. Molecular biology reagents (which were used in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations) and oligonucleotides were purchased from Invitrogen, Pharmacia, or BCL. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used in this work are shown in Table 1.

Molecular biology and biochemistry

Routine molecular biology protocols followed individual manufacturer’s recommendations or were as described (Maniatis et al. 1982; Lamb et al. 1996). All DNA sequencing was carried out on double-stranded plasmid DNA using an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer in the University of Newcastle upon Tyne Facility for Molecular Biology.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was as described (Hemsley et al. 1989) using the oligonucleotides shown in Table 1. The plasmid substrate for areA mutagenesis was pRF48 and for nmrA was pTR121 (Nichols et al. 2001; Lamb et al. 2003).

Purification of NmrA and a C-terminal fragment of AreA

NmrA wild-type and mutant, and C-terminal fragments of AreA (designated AreA662 and AreA662Δ9) were purified using the protocols described (Nichols et al. 2001; Lamb et al. 2003).

Protein and DNA concentrations

Protein and DNA concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically as described (Gill and von Hippel 1989) using the known (DNA) or theoretical molar absorption coefficient calculated by the Vector Nti suite of programs (protein).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry experiments at 25°C were performed using a high-precision VP-ITC titration calorimetric system (Microcal). For the study of protein:protein interactions, NmrA in the injection syringe was titrated into AreA662 or AreA662Δ9, in the calorimetric cell (1.4 mL) in the concentration ranges described in the legends to Tables 2 and 4. For the study of protein:DNA interactions, the ds-oligonucleotides in the injection syringe were titrated into AreA662 in the calorimetric cells. For a description of the more complex titrations, see Table 2. The proteins were dialysed into 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT, and the DNA was dissolved in the same buffer. Oligonucleotides 522 and 523 were annealed to produce GATA site 5, and oligonucleotides 524 and 525 were annealed to produce a mutant GATA site 5 in which the GATA motif was changed to GTAA. Oligonucleotides 528 and 529 were annealed to produce GATA site 9. Oligonucleotides were annealed as described (Reid et al. 2001). The heat evolved following each 10-μL injection was obtained from the integral of the calorimetric signal. The heat due to the binding reaction was obtained as the difference between the heat of reaction and the corresponding heat of dilution. Analysis of data was performed using Microcal Origin Software.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry measurements on NmrA and NmrA mutants were made using a Microcal VP-DSC instrument at a scan rate of 1°C per min and a filtering period of 16 sec. Proteins were dialysed in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT, and the dialysis buffer was retained to dissolve ligands, to dilute proteins, and for baseline controls. The concentrations of protein and ligands are given in the Table 3 legend. Ligand-induced shifts in thermal transition midpoint temperatures (Tm) were used to estimate approximate ligand affinities using standard thermodynamic methods as described (Cooper 1999; Cooper et al. 2000).

Fluorescence anisotropy assays

Oligonucleotides 519 and 522 were annealed to produce GATA site 5 with a Hexachlorofluorescein (HEX) label. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were carried out at 25°C using an SLM-Aminco 8100 fluorimeter in a buffer consisting of 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 1 mM DTT. The excitation wavelength was 530 nm (slit width 8 nm), and the emission was detected through a 3-mm thick 570-nm cut-off filter. A 1-mL fluorescence cuvette with excitation and emission pathlengths 10 mm each was used. For measurements for the direct binding of AreA662 or AreA662Δ9 to GATA-containing DNA, the initial volume was 1 mL, and small volumes of AreA662 or AreA662Δ9 were added to the fluorescent oligonucleotide; the anisotropy was measured after each addition. For competition titrations, small volumes of oligonucleotide were added to a preformed AreA662/Hex-labeled GATA site 5 complex, and the anisotropy was measured after each addition. Anisotropy was measured as described (Reid et al. 2001).

Protein crystallization and structure determination

Unliganded NmrA N12G/A18G was crystallized in the trigonal crystal form as described for wild-type protein (Nichols et al. 2001; Stammers et al. 2001). Crystals were flash frozen using 20% glycerol as cryoprotectant and maintained at 100 K in a stream of cooled nitrogen gas. X-ray diffraction data for NmrA N12G/A18G crystals were collected to 1.4 Å resolution at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility beam-line ID14EH4 (λ = 0.9323 Å) equipped with an ADSC Quantum 4 CCD detector. A total of 180 data frames of 1° oscillation were collected, giving 69,599 unique reflections with ninefold redundancy for 25.0–1.40 Å resolution. The data frames were indexed and integrated with DENZO and scaled with SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor 1996).

The NmrA N12G/A18G structure was solved by rigid-body refinement using the CNS program with the wild-type NmrA coordinates (PDB code 1K6I) as the starting model. The NmrA model was rebuilt from 2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc maps using the O program on a Silicon Graphics Octane workstation, and the N12G/A18G mutations incorporated. Rounds of positional and B-factor refinement with anisotropic B-factor scaling and solvent correction were carried out using CNS. The refined model contains 325 protein residues, 606 water molecules, one glycerol molecule, one phosphate, four potassium and five chlorine ions. There is no density for residues 1–2 and the flexible glycine-rich loop 284–308, which are not modeled in the structure. The electron density shows clearly double conformations for the side chains of residues Asn80, Thr82, Arg239, and Arg329. The final model has a working R-factor of 0.193 (Rfree = 0.238) for data in the resolution range 25.0–1.40 Å, with the retention of good stereochemistry (Table 5).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Wellcome Trust. We thank Prof. Bernard Connolly for synthesizing the HEX-labeled oligonucleotide 519, Elaine Cairns for technical assistance, and Debra Wilson for constructing plasmid pTR191 as part of her final-year undergraduate research project.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.04958904.

References

- Andrianopoulos, A., Kourambas, S., Sharp, J.A., Davis, M.A., and Hynes, M.J. 1998. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans nmrA gene involved in nitrogen metabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 180 1973–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barredo, J.L., Cantoral, J.M., Alvarez, E., Diez, B., and Martin, J.F. 1989. Cloning, sequence analysis and transcriptional study of the isopenicillin N synthase of Penicillium chrysogenum AS-P-78. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T. and Hall, M.N. 1999. The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature 402 689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A. 1999. Thermodynamics of protein folding and stability. In Protein: A comprehensive treatise. (ed. G. Allen), pp. 217–270. JAI Press Inc., Stamford, CT.

- Cooper, A., Nutley, M.A., and Wadood, A. 2000. Differential scanning microcalorimetry. In Protein-ligand interactions: Hydrodynamics and calorimetry. (eds. S.E. Harding and B.Z. Chowdry), pp. 287–318. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Cox, K.H., Rai, R., Distler, M., Daugherty, J.R., Coffman, J.A., and Cooper, T.G. 2000. Saccharomyces cerevisiae GATA sequences function as TATA elements during nitrogen catabolite repression and when Gln3p is excluded from the nucleus by overproduction of Ure2p. J. Biol. Chem. 275 17611–17618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.A. and Hynes, M.J. 1987. Complementation of areA-regulatory gene mutations of Aspergillus nidulans by the heterologous regulatory gene nit-2 of Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84 3753–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBusk, R.M. and Ogilvie, S. 1984. Nitrogen regulation of amino acid utilization by Neurospora crassa. J. Bacteriol. 160 493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn-Coleman, N.S., Tomsett, A.B., and Garrett, R.H. 1979. Nitrogen metabolite repression of nitrate reductase in Neurospora crassa: Effect of the gln-1a locus. J. Bacteriol. 139 697–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.H. and Marzluf, G.A. 1990. nit-2, the major nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa, encodes a protein with a putative zinc finger DNA-binding domain. Mol. Cell Biol. 10 1056–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, S.C. and von Hippel, P.H. 1989. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove, G. and Marzluf, G.A. 1981. Identification of the product of the major regulatory gene of the nitrogen control circuit of Neurospora crassa as a nuclear DNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 256 463–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, A., Arnheim, N., Toney, M.D., Cortopassi, G., and Galas, D.J. 1989. A simple method for site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 6545–6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, I.L., McCabe, P.C., Greaves, P., Gurr, S.J., Cole, G.E., Brow, M.A., Unkles, S.E., Clutterbuck, A.J., Kinghorn, J.R., and Innis, M.A. 1990. Isolation and characterisation of the crnA-niiA-niaD gene cluster for nitrate assimilation in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 90 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, A.A., Abul-Hamd, A.T., Rai, R., El Berry, H., and Cooper, T.G. 2001. Gln3p nuclear localization and interaction with Ure2p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276 32136–32144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladbury, J.E., Lemmon, M.A., Zhou, M., Green, J., Botfield, M.C., and Schlessinger, J. 1995. Measurement of the binding of tyrosyl phosphopeptides to SH2 domains: A reappraisal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92 3199–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, H.K., Newton, G.H., Levett, L.J., Cairns, E., Roberts, C.F., and Hawkins, A.R. 1996. The QUTA activator and QUTR repressor proteins of Aspergillus nidulans interact to regulate transcription of the quinate utilization pathway genes. Microbiology 142 (Pt. 6): 1477–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, H.K., Leslie, K., Dodds, A.L., Nutley, M., Cooper, A., Johnson, C., Thompson, P., Stammers, D.K., and Hawkins, A.R. 2003. The negative transcriptional regulator NmrA discriminates between oxidized and reduced dinucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 278 32107–32114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrain, P., Wojcik, J., and Gauthier, J.M. 2001. Protein–protein interaction maps: A lead towards cellular functions. Trends Genet. 17 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E.F., and Sambrook, J. 1982. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Marzluf, G.A. 1997. Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61 17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro-Pastor, M.I., Gonzalez, R., Strauss, J., Narendja, F., and Scazzocchio, C. 1999. The GATA factor AreA is essential for chromatin remodelling in a eukaryotic bidirectional promoter. EMBO J. 18 1584–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendja, F., Goller, S.P., Wolschek, M., and Strauss, J. 2002. Nitrate and the GATA factor AreA are necessary for in vivo binding of NirA, the pathway-specific transcriptional activator of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 44 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, C.E., Cocklin, S., Dodds, A., Ren, J., Lamb, H., Hawkins, A.R., and Stammers, D.K. 2001. Expression, purification and crystallization of Aspergillus nidulans NmrA, a negative regulatory protein involved in nitrogen-metabolite repression. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57 1722–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. and Minor, W. 1996. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H., Feng, B., and Marzluf, G.A. 1997. Two distinct protein–protein interactions between the NIT2 and NMR regulatory proteins are required to establish nitrogen metabolite repression in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Microbiol. 26 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, G., Gish, G., End, P., Truong, O., Gout, I., Dhand, R., Fry, M.J., Hiles, I., Pawson, T., and Waterfield, M.D. 1993. Interactions between SH2 domains and tyrosine-phosphorylated platelet-derived growth factor β-receptor sequences: Analysis of kinetic parameters by a novel biosensor-based approach. Mol. Cell Biol. 13 3567–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt, A., Langdon, T., Arst Jr., H.N., Kirk, D., Tollervey, D., Sanchez, J.M., and Caddick, M.X. 1996. Nitrogen metabolite signalling involves the C-terminus and the GATA domain of the Aspergillus transcription factor AREA and the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNA. EMBO J. 15 2791–2801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punt, P.J., Greaves, P.A., Kuyvenhoven, A., van Deutekom, J.C., Kinghorn, J.R., Pouwels, P.H., and van den Hondel, C.A. 1991. A twin-reporter vector for simultaneous analysis of expression signals of divergently transcribed, contiguous genes in filamentous fungi. Gene 104 119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punt, P.J., Strauss, J., Smit, R., Kinghorn, J.R., van den Hondel, C.A., and Scazzocchio, C. 1995. The intergenic region between the divergently transcribed niiA and niaD genes of Aspergillus nidulans contains multiple NirA binding sites which act bidirectionally. Mol. Cell Biol. 15 5688–5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.L., Parry, D., Liu, H.H., and Connolly, B.A. 2001. Binding and recognition of GATATC target sequences by the EcoRV restriction endonuclease: A study using fluorescent oligonucleotides and fluorescence polarization. Biochemistry 40 2484–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, J., Reick, M., Wu, L.C., and McKnight, S.L. 2001. Regulation of clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors. Science 293 510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stammers, D.K., Ren, J., Leslie, K., Nichols, C.E., Lamb, H.K., Cocklin, S., Dodds, A., and Hawkins, A.R. 2001. The structure of the negative transcriptional regulator NmrA reveals a structural superfamily which includes the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases. EMBO J. 20 6619–6626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden, J.B., Wohlers, T.M., Fridovich-Keil, J.L., and Holden, H.M. 2001. Molecular basis for severe epimerase deficiency galactosemia. X-ray structure of the human V94m-substituted UDP-galactose 4-epimerase. J. Biol. Chem. 276 20617–20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.A. and Arst Jr., H.N. 1998. Mutational analysis of AREA, a transcriptional activator mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans and a member of the “streetwise” GATA family of transcription factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 62 586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, T., Williston, S., Brandts, J.F., and Lin, L.N. 1989. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 179 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X., Fu, Y.H., and Marzluf, G.A. 1995. The negative-acting NMR regulatory protein of Neurospora crassa binds to and inhibits the DNA-binding activity of the positive-acting nitrogen regulatory protein NIT2. Biochemistry 34 8861–8868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.L. and Marzluf, G.A. 1991. Molecular comparison of the negative-acting nitrogen control gene, nmr, in Neurospora crassa and other Neurospora and fungal species. Biochem Genet. 29 447–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]