Abstract

Legumes can acquire nitrogen (N) from NO3−, NH4+, and N2 (through symbiosis with Rhizobium bacteria); however, the mechanisms by which uptake and assimilation of these N forms are coordinately regulated to match the N demand of the plant are currently unknown. Here, we find by use of the split-root approach in Medicago truncatula plants that NO3− uptake, NH4+ uptake, and N2 fixation are under general control by systemic signaling of plant N status. Indeed, irrespective of the nature of the N source, N acquisition by one side of the root system is repressed by high N supply to the other side. Transcriptome analysis facilitated the identification of over 3,000 genes that were regulated by systemic signaling of the plant N status. However, detailed scrutiny of the data revealed that the observation of differential gene expression was highly dependent on the N source. Localized N starvation results, in the unstarved roots of the same plant, in a strong compensatory up-regulation of NO3− uptake but not of either NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation. This indicates that the three N acquisition pathways do not always respond similarly to a change in plant N status. When taken together, these data indicate that although systemic signals of N status control root N acquisition, the regulatory gene networks targeted by these signals, as well as the functional response of the N acquisition systems, are predominantly determined by the nature of the N source.

Nitrogen (N) is one of the mineral nutrients needed in the greatest amount for plant nutrition. It very often limits plant growth because of spatial and temporal fluctuations of its concentration in the soil, which hamper sustained acquisition by the root system. For this reason, plants have developed adaptive responses allowing them to modulate the efficiency of root N acquisition as a function of both external N availability and their own nutritional status (for review, see Von Wiren et al., 2000; Forde, 2002a). Typical responses to low N provision include increased activity and affinity of uptake systems (Crawford and Glass, 1998; Gazzarrini et al., 1999; Lejay et al., 1999; Rawat et al., 1999) and enhanced lateral root growth promoting root branching and, thus, soil exploration (Forde and Lorenzo, 2001). The regulatory mechanisms involved in these responses are mostly characterized at the physiological level but still remain largely unknown at the molecular level. To understand these mechanisms is challenging, because unlike many other nutrients, N may be acquired in a variety of forms: predominantly nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+) but also amino acids and peptides (Williams and Miller, 2001; Tsay et al., 2007). In addition, several plant species, particularly legumes, have the ability to indirectly acquire N from the atmospheric N2 through symbiosis with N2-fixing bacteria. The general rule in agro-ecosystems is that N nutrition occurs from several forms of N that are simultaneously taken up by the roots. Even in legumes, symbiotic N2 fixation often may not account for the majority of total N accumulation, because the uptake of NO3− and NH4+ is favored by the plant when these ions are available (Wery et al., 1986; Silsbury, 1987; Carroll and Mathews, 1990). Given that the control of N nutrition has barely been investigated in plants supplied with different N sources, the mechanisms involved in the coordinated regulation of the acquisition of the various N forms are not known.

A general model of control of root N acquisition has been proposed, mostly from data obtained with NO3−-fed plants (Forde, 2002a). In its general principle, the scheme holds true for both root NO3− uptake systems and root development. It combines regulatory mechanisms involving local NO3− signaling and the systemic action of long-distance signals of the plant N status. It is now well established that NO3− is a signal molecule that acts locally to regulate many aspects of plant intake, metabolism, and development (for review, see Crawford, 1995; Stitt, 1999; Miller et al., 2007). On one hand, NO3− induces the expression of many proteins required for its utilization by the plant, such as NO3− transporters of the NRT1 and NRT2 families, enzymes of NO3− assimilation, and enzymes of the pentose phosphate pathway or carboxylic acid metabolism (ensuring, respectively, the supply of reducing power for NO3− reduction and carbon skeletons for amino acid synthesis). On the other hand, NO3− stimulates lateral root growth through a specific signaling pathway mediated by the ANR1 transcription factor (TF) and the NRT1.1 NO3− transporter (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Remans et al., 2006). It is now clear that the signaling effect of NO3− goes far beyond the control of processes related to its own assimilation pathway. Several transcriptomic approaches on Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and rice (Oryza sativa) have already identified more than a thousand genes differentially expressed upon NO3− supply (Wang et al., 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004; Scheible et al., 2004). Despite the fact that the experimental procedures and/or species were different, many of the genes identified were common between these studies, suggesting a robust regulatory network associated with the NO3− signal (Gutierrez et al., 2007a).

In comparison to local NO3− signaling, little is known about the genes involved in the long-distance control of root NO3− acquisition by the N status of the plant. A model based on a satiety signal that would be translocated from the shoots to the roots and leading to the down-regulation of NO3− transport systems has been proposed (Imsande and Touraine, 1994). It has been demonstrated in various species that the early steps of root NO3− acquisition are under negative feedback exerted by downstream N metabolites of the whole plant. Split-root experiments have revealed that the uptake of roots continuously fed with NO3− is up-regulated in response to the N limitation experienced by another part of the root system, demonstrating that the feedback repression is mediated by a systemic signal (Burns, 1991; Gansel et al., 2001). Evidence supports the hypothesis that this satiety signal is related to the downward transport of N metabolites. Amino acids are major constituents of both xylem and phloem saps, and it has been suggested that the size and/or composition of the amino acid pool cycling between roots and shoot may integrate the N status of all organs and convey this information to the roots (Cooper and Clarkson, 1989). The use of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and Arabidopsis nitrate reductase-deficient mutants has confirmed that products of NO3− assimilation are involved in the feedback repression of NO3− uptake (Gojon et al., 1998; Lejay et al., 1999). Furthermore, exogenous supply of amino acids strongly represses both NO3− uptake and the expression of key NO3− transporter genes in the roots (Müller and Touraine, 1992; Krapp et al., 1998; Zhuo et al., 1999; Nazoa et al., 2003). Interestingly, it has been independently shown that systemic signaling mechanisms possibly related to both NO3− and N metabolites modulate lateral root development in response to changes in NO3− supply (Zhang et al., 1999).

Whether the same models may be applied to the regulation of the acquisition of other N sources remains an open question. Indeed, in comparison with NO3− uptake, much less is known about regulatory mechanisms controlling either NH4+ or N2 acquisition. On one hand, with the exception of Glu (Walch-Liu et al., 2006), it is unclear if N forms other than NO3− are able to trigger local signaling (Loque and Von Wiren, 2004). On the other hand, it is tempting to postulate that root acquisition of the various N forms is under a general control exerted by a systemic signaling pathway related to the level of downstream product of N assimilation in the whole plant. This would allow distinct processes involved (NO3− uptake, NH4+ uptake, amino acid uptake, peptide uptake, N2 fixation) to be coordinately regulated and to match the N demand of the whole plant (Cooper and Clarkson, 1989; Parsons et al., 1993; Imsande and Touraine, 1994). Several observations are in agreement with this hypothesis. For instance, NH4+ uptake and nodule N2 fixation activity are inversely correlated with Gln or/and Asn concentration in the roots and, conversely, exogenous supply of amino acids in the root medium down-regulates root NH4+ uptake and N2 fixation (Lee et al., 1992; Bacanamwo and Harper, 1997; Neo and Layzell, 1997; Rawat et al., 1999). This suggests that downstream N metabolites may also repress the acquisition of those N sources. Short-term inhibition of N2 fixation by high provision of NO3− has also been extensively described (for review, see Streeter, 1988). An early study has reported that NO3− suppresses nodulation locally while repressing the fixation activity of nodule systemically (Hinson, 1975). Several studies suggest that this repression may be mediated by phloem-translocated amino acids, most probably by modulating O2 diffusion in the nodules (Parsons et al., 1993; Neo and Layzell, 1997). However, some reports do not support the occurrence of common regulatory mechanisms for the acquisition of the various N sources. For example, split-root experiments in Arabidopsis have shown that unlike NO3−-fed plants, NH4+-fed plants are unable to display systemic responses to localized N limitation (i.e. stimulation of N uptake and lateral root growth), suggesting that NH4+ acquisition is predominantly regulated at the local level (Zhang et al., 1999; Gansel et al., 2001).

We initiated a study on the model legume Medicago truncatula with two main objectives. First, we aimed to elucidate if the three main pathways for N acquisition, namely NO3− uptake, NH4+ uptake, and N2 fixation, are under the control of systemic feedback repression exerted by the N status of the whole plant. Secondly, we performed large-scale transcriptome studies to delineate the gene networks responding to this systemic signaling in the roots and to determine whether these networks are common for all three N sources. Several transcriptome studies have already been performed to analyze the molecular responses of the roots to a change of the nitrogen status of the plant (Scheible et al., 2004; Gutierrez et al., 2007b). However, none of these studies allowed discrimination between the action of local or systemic signaling pathways. Given that we specifically focused on the systemic regulatory mechanisms and used an appropriate experimental system (split-root plants), this study provides an unprecedented description of the genome-scale reprogramming of transcription triggered by long-distance signals of nutrient status, which play a central role in the integration of root ion acquisition in the whole plant.

RESULTS

Experimental Strategy

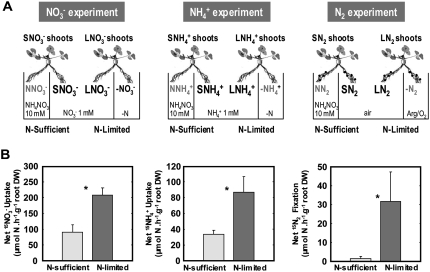

To focus on the systemic feedback repression of root N acquisition by the N status of the whole plant, split-root experiments were performed to investigate the response of one side of the root system to N treatments applied on the other side (Fig. 1A). Hydroponically grown plants fed with either 1 mm NO3−, 1 mm NH4+, or fixing N2 were subjected during 4 d to two contrasted N regimes corresponding to the supply of 10 mm NH4NO3 solution to the treated side of the root system (NN roots) or to the N starvation of the treated side of the root system (−N roots). The plants subjected to these repressive or de-repressive treatments were hereafter called, respectively, N-sufficient (S) and N-limited (L) plants.

Figure 1.

Comparison of S and L plants. A, Description of the three types of split-root systems. Hydroponically grown plants fed with either 1 mm KNO3, 1 mm NH4Cl, or fixing N2 (nodulated in presence of Rhizobium meliloti) were subjected, over a period of 4 d, to two contrasted N regimes. In S plants, a concentrated (10 mm) NH4NO3 solution was applied on the treated side of the root system (NN roots). In L plants, the N source was removed to the treated side of the root system (−N roots). For NO3−-fed and NH4+-fed plants, this last treatment was achieved by transferring the roots to N-free solution. For N2-fixing plants, it was achieved by suppressing N2 from the root atmosphere (replacement of normal air by a 80%:20% argon:O2 mixture). S and L roots were continuously exposed to the same local environment during the treatment. Names of the organs submitted to transcriptome analysis are indicated in black, others are in gray. B, NO3−, NH4+, and N2 acquisition of the S and L roots. From the left to the right are: net NO3− intake of SNO3− and LNO3− roots, net NH4+ intake of SNH4+ and LNH4+ roots, net N2 intake of SN2 and LN2 roots. The values are the means of six replicates of one biological repeat. They are representative of three independent biological repeats. Vertical bars indicate sd. *Significant difference according to t test (P < 0.001).

Given that the changes occurring in the untreated side of the root system result from an altered N supply to the other organs of the plant, they are indicative of the action of systemic signaling pathways. The experimental set-up described in Figure 1A allowed us to reveal the physiological and molecular responses of the roots to systemic signals of whole-plant N status (L roots versus S roots) and to compare these responses between the three N sources. Two main assays were performed to characterize these responses. First, root N uptake was measured by 15N labeling (15NO3− uptake, 15NH4+ uptake, or 15N2 fixation). Second, to identify the molecular basis of the N intake modification, transcriptome analysis was performed using Affymetrix Medicago genome arrays and high-throughput quantitative real-time (Q-RT)-PCR. Although we intend to focus on the responses occurring in S and L roots, transcriptome analysis was also performed in the S and L shoots and in the treated roots of NO3−-fed plants subjected to N starvation.

Root N Acquisition Is under Systemic Feedback Repression by High N Status of the Plant Regardless of the N Source

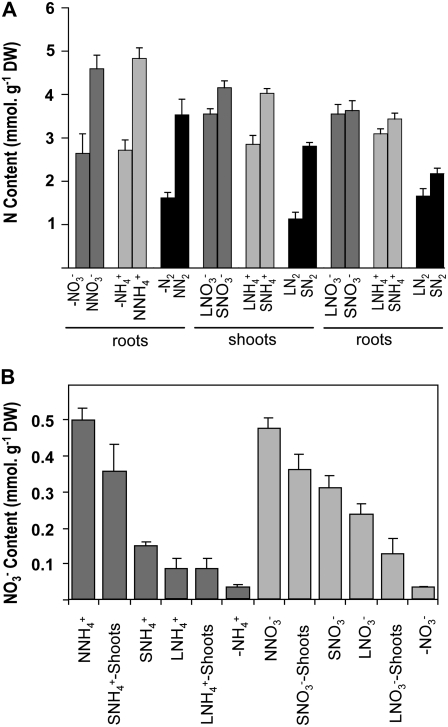

To verify that the treatments described in Figure 1A resulted in significant changes in the N status of the whole plant, total N content was assayed in roots and shoots of all groups of plants (Fig. 2A). In treated roots, N starvation or supply of 10 mm NH4NO3 led to marked differences in the total N contents of the tissues after 4 d; a 40% to 50% decrease occurred in −N roots as compared to NN roots, regardless of the N source. The treatments also resulted in differences in total N concentration in shoots, but the effect strongly depended on the N source (60% for N2-fixing plants, 29% for NH4+-fed plants, and 15% for NO3−-fed plants). Nevertheless, total N concentration in untreated roots was not or only slightly affected by the treatments. The two treatments resulted in two contrasted levels of N status of the whole plant without significantly altering the N contents of the untreated roots and therefore provided appropriate plant material to investigate systemic responses.

Figure 2.

Nitrogen content of the organs of L and S plants. Plants are described in Figure 1. A, Total N content. B, NO3− content. The values are the means of six replicates. Vertical bars indicate sd.

The rates of N acquisition in untreated roots of S and L plants were measured after 4 d of treatment using 15NO3−, 15NH4+, or 15N2 as tracers (Fig. 1B). The highest uptake rate was observed in L plants supplied with NO3− (in the range of 200 μmol h−1 g−1 root dry weight). In comparison, root N uptake was reduced by 55% and 85% in L plants supplied with NH4+ or N2, respectively. For all three N sources, the supply of 10 mm NH4NO3 to the treated root side of S plants triggered a strong repression of N acquisition in the untreated roots, as compared with L plants. For NO3− and NH4+, the inhibition was approximately 60% in S versus L plants. The repression was more dramatic in N2-fixing plants (>90% inhibition). Similar results were obtained when 20 mm NH4+ was supplied to the treated roots instead of 10 mm NH4NO3 (data not shown). These experiments demonstrate that the three N acquisition pathways in Medicago are under feedback regulation by systemic signals related to the N status of the whole plant.

These results are thus in favor of the hypothesis that common systemic regulatory mechanisms may ultimately and coordinately govern NO3− uptake, NH4+ uptake, and N2 fixation in legumes. To further test this hypothesis, we next investigated the molecular responses associated with the systemic repressions of the acquisitions of these three sources. The transcriptomic approach was initiated on roots and shoots of the three groups of plants described above.

Genome-Wide Transcriptional Reprogramming Is Associated with Local and Systemic N Signaling in NO3−-Fed Plants

Before embarking on the identification of genes that respond in the roots to the systemic signals related to the plant N status (LNO3− roots versus SNO3− roots; see Fig. 1A), we characterized genes that are regulated by the local presence of NO3− (LNO3− roots versus −NO3−; see Fig. 1A). On the basis of the previous studies with Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice (Wang et al., 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004; Scheible et al., 2004), the main molecular responses to NO3− may be anticipated in Medicago, and therefore this offered the opportunity to test our transcript profiling strategy. As anticipated, the 4-d N starvation treatment led to a dramatic decrease in NO3− content of −NO3− roots, which was more than 85% lower than that of LNO3− roots (Fig. 2B). In total, 1,575 genes were found to be differentially expressed between LNO3− and −NO3− roots, with 315 and 1,260 being up-regulated and down-regulated in LNO3− roots as compared to −NO3− roots, respectively (Table I). Many of these genes belong to functional categories previously identified to be NO3−-regulated in Arabidopsis and tomato, indicating that Medicago share similar global molecular responses to NO3− with other species (Supplemental Table S1). A large group was formed by genes involved in NO3− transport and assimilation (Table II). Seven transcripts annotated as NO3− transporters homologous to NRT1 and NRT2 transporters were differentially accumulated in response to NO3−. As in Arabidopsis, a stimulation of expression by NO3− is generally observed. An exception to this was a close homolog of AtNRT2.5, which, like its corresponding gene in Arabidopsis, was repressed by NO3− (Orsel et al., 2002; Okamoto et al., 2003). Three transcripts annotated as ClC channels also display differential accumulation in response to NO3−, which is consistent with a role of these proteins in NO3− transport (De Angeli et al., 2006). Many transcripts annotated as enzymes directly or indirectly related to NO3− assimilation, such as structural enzymes of NO3− assimilation, synthesis of cofactors of these enzymes, production of reducting equivalents for NO3− assimilation, the latter part of glycolysis and organic acid metabolism were also found to be overaccumulated in response to NO3−, which is in good agreement with data obtained on Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2003; Scheible et al., 2004). Responses to NO3− signaling were also expected in the shoots of S plants, because SNO3− shoots display a higher NO3− content than LNO3− shoots (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, the analysis of the 436 genes differentially expressed between LNO3− and SNO3− shoots revealed that many previously characterized NO3-inducible genes were found to be down-regulated in LNO3− shoots compared with SNO3− shoots (Table I; Supplemental Table S2). These include genes involved in NO3− transport and metabolism (Table II) as well as other genes already found to be NO3−-responsive in shoots of other species (e.g. nicotianamine synthase, sulfate transporter, and glutaredoxin; see Wang et al., 2003). Given that the typical molecular responses to NO3− in both the roots and the shoots of NO3−-fed plants were observed, these data provide a strong validation of our transcriptomic strategy.

Table I.

Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by transcriptomic analysis of the various organs of plant grown in split root system (plant material is described in Fig. 1A)

| Up-Regulated

|

Down-Regulated

|

Total | Not Annotated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | FCa > 4 | 2 < FCa <4 | Total | FCa < −4 | −2 > FCa > −4 | |||

| LNO3− versus −NO3− roots | 315 | 103 | 212 | 1,260 | 495 | 765 | 1,575 | 404 |

| LNO3− versus SNO3− roots | 396 | 73 | 323 | 541 | 91 | 450 | 937 | 196 |

| LNO3− versus SNO3− shoots | 327 | 13 | 314 | 109 | 18 | 91 | 436 | 109 |

| LNH4+ versus SNH4+roots | 347 | 27 | 320 | 353 | 35 | 318 | 700 | 150 |

| LNH4+ versus SNH4+ shoots | 180 | 17 | 163 | 195 | 32 | 163 | 375 | 90 |

| LN2 versus SN2 roots | 859 | 710 | 149 | 376 | 205 | 171 | 1,235 | 340 |

| LN2 versus SN2 shoots | 233 | 75 | 158 | 209 | 91 | 118 | 442 | 99 |

Fold-change of transcript accumulation.

Table II.

Differentially accumulated transcripts annotated as related to N assimilation

| Target Identificationa | Annotation | Rootsb

|

Shootsb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNO3− versus NO3− | LNO3− versus SNO3− | LNH4+ versus SNH4+ | LN2 versus SN2 | LNO3− versus SNO3− | LNH4+ versus SNH4+ | LN2 versus SN2 | ||

| Nitrate and Nitrite Reduction | ||||||||

| Msa.1381.1.S1_at | Nitrate reductase NADH | 6.06 | 9.19 | – | – | −2.13 | −4.38 | – |

| Mtr.10604.1.S1_at | Nitrate reductase [NADH] | 10.27 | 7.59 | – | 2.05 | – | −4.16 | – |

| Mtr.42446.1.S1_at | Nitrate reductase | 130.69 | 65.57 | – | 4.23 | −3.59 | −3.52 | 4.94 |

| Mtr.8568.1.S1_at | Nitrite reductase | 13.09 | 2.91 | – | – | −2.66 | −13.13 | |

| Mtr.13053.1.S1_at | Urophorphyrin III methylase | 29.86 | 5.21 | – | – | 5.58 | −15.83 | −10.78 |

| Mtr.13053.1.S1_s_at | Urophorphyrin III methylase | 12.17 | 3.72 | – | – | 4.66 | −11.31 | −9.55 |

| Mtr.22364.1.S1_at | Urophorphyrin III methylase | 3.25 | 3.16 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.44855.1.S1_at | Urophorphyrin III methylase | 14.88 | 4.56 | – | – | 4.13 | −9.88 | −12.51 |

| Mtr.37556.1.S1_at | Ferredoxin-NADP reductase | 10.82 | 2.65 | – | – | 2.30 | −2.36 | −3.48 |

| Mtr.40420.1.S1_at | Nonphotosynthetic ferredoxin | 23.92 | 3.01 | – | 2.83 | −8.31 | −22.55 | −60.97 |

| Mtr.39504.1.S1_at | Glc-6-P 1-dehydrogenase | 11.43 | 4.06 | – | – | 2.11 | −2.60 | −2.16 |

| Msa.2779.1.S1_at | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 4.81 | 2.66 | – | – | – | – | −2.34 |

| Mtr.43234.1.S1_at | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 4.30 | 2.37 | – | – | – | – | −2.09 |

| Msa.2673.1.S1_at | Transaldolase | – | – | – | – | – | – | −2.66 |

| Ammonium Assimilation | ||||||||

| Mtr.4818.1.S1_s_at | Gln synthetase | 9.88 | 3.07 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Msa.1654.1.S1_at | Gln synthetase | 9.38 | 2.97 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.10480.1.S1_at | Gln synthetase | 12.55 | 3.16 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.43850.1.S1_at | Mt N6/Gln synthetase I-like | – | – | – | 3.72 | – | – | – |

| Mtr.12432.1.S1_at | NADH-dependent Glu synthase | 2.06 | 2.17 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.42795.1.S1_at | Glu synthase | −2.98 | – | – | – | – | −2.03 | – |

| Mtr.7084.1.S1_at | Asn synthase | 5.50 | 3.45 | – | – | −4.87 | −3.75 | −11.20 |

| Mtr.7558.1.S1_at | Asn synthetase 2 | 3.51 | 2.85 | – | – | −3.02 | −3.22 | −7.57 |

| Mtr.33541.1.S1_x_at | Asn synthase | 6.52 | 3.62 | – | – | – | – | 7.65 |

| Glycolysis and Organic Acid Metabolism | ||||||||

| Mtr.40930.1.S1_at | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 7.92 | 2.82 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Msa.1072.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.10 |

| Mtr.10198.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | – | – | – | – | 2.71 | – | 3.88 |

| Mtr.13967.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.41 |

| Mtr.34902.1.S1_s_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 66.49 | 7.89 | – | −2.24 | −3.29 | −10.70 | −6.80 |

| Mtr.36140.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.82 |

| Mtr.39390.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.15 |

| Mtr.8683.1.S1_at | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 59.10 | 8.88 | – | – | −2.43 | −7.36 | −4.89 |

| Msa.3137.1.S1_at | Malate dehydrogenase | 2.09 | 2.17 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.40396.1.S1_at | Malate dehydrogenase | 2.02 | 2.20 | – | 2.07 | – | – | – |

| Mtr.45179.1.S1_at | Malate dehydrogenase | 2.58 | – | −2.64 | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.6743.1.S1_at | 2-Oxoglutarate/malatetranslocator-like | – | – | – | 2.16 | – | −2.00 | – |

| Putative Nitrate Transporters | ||||||||

| Mtr.44730.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.4 | – | – | – | −7.36 | – | – | – |

| Mtr.39005.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.4 | – | – | – | −7.97 | – | – | – |

| Msa.3151.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.4 | – | – | – | −6.06 | – | – | – |

| Mtr.35838.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.1 | 35.51 | 3.22 | −2.69 | −5.13 | 1.82 | 1.56 | 2.28 |

| Mtr.5369.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.1 | 69.07 | 4.71 | −2.52 | −9.82 | 1.87 | 1.34 | 2.45 |

| Mtr.27575.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter similar to AtNRT1.1 | 61.61 | 4.55 | −2.58 | −7.06 | – | – | 2.59 |

| Mtr.40975.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter | – | – | 2.28 | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.37657.1.S1_at | NRT1 transporter | – | – | – | 2.26 | −3.80 | −3.38 | – |

| Mtr.35456.1.S1_at | NRT2 transporter similar to AtNRT2.5 | −12.77 | 2.25 | 3.75 | 14.52 | – | – | – |

| Mtr.40270.1.S1_at | NRT2 transporter similar to AtNRT2.1 | 2.07 | 4.94 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.9576.1.S1_at | CLC channel (similar clc-Nt2) | 2.73 | – | – | – | −2.63 | −10.20 | −102.54 |

| Mtr.39260.1.S1_at | CLC channel (similar to Atclc-b) | 2.55 | – | – | – | −2.87 | −10.78 | −43.26 |

| Mtr.32338.1.S1_at | CLC channel (similar to Atclc-e) | −2.50 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Putative Ammonium Transporters | ||||||||

| Mtr.10556.1.S1_at | Putative AMT1 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.3650.1.S1_at | Putative AMT1 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.1706.1S1_at | Putative AMT1 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.46839.1.S1_at | Putative AMT1 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.19853.1.S1_at | Putative AMT2 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.32395.1.S1_s_at | Putative AMT2 transporter | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mtr.43740.1.S1_at | Nodulin 26-like protein (MIP family) | – | – | – | 19.03 | – | – | – |

| Msa.1751.1.S1_at | Nodulin 26-like protein (MIP family) | – | – | – | 4.17 | – | – | – |

Target identifier (Affymetrix or MtTF Q-RT-PCR).

Fold-change of transcript accumulation.

Large-scale molecular responses of the roots to systemic signals related to the plant N status were next characterized by quantifying the variations of gene expression between LNO3− and SNO3− roots (Fig. 1A). The comparison identified 937 differentially expressed genes, 541 being down-regulated and 396 up-regulated in LNO3− roots as compared to SNO3− roots (Supplemental Table S3). These genes are direct or indirect molecular targets of the systemic control exerted by the N status of the whole plant. A subgroup of 156 genes was already identified as differentially expressed in the LNO3− versus −NO3− comparison (Supplemental Table S4). In most cases, common genes were up-regulated by NO3− supply (i.e. in LNO3− roots versus −NO3− roots) and down-regulated by the systemic signaling related to high N status (i.e. in SNO3− roots versus LNO3− roots). Many of the 156 transcripts were annotated as involved in NO3− transport or assimilation (NRT1 and NRT2 transporters, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, Gln synthetase, Glu synthase, Asn synthetase), in the synthesis of cofactors of these enzymes (uroporphyrin methylase), in glycolysis and organic acid metabolism (phosphoglycerate-mutase, phosphoenolpyruvate-carboxylase, malate-dehydrogenase), and in the production of reducting equivalents for NO3− assimilation (ferredoxin-reductase, Glc-6-P-dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconate-dehydrogenase), consistent with the inhibition of NO3− acquisition occurring in SNO3− roots as compared to LNO3− roots (Table II). An example is the closest homolog of the high affinity AtNRT2.1 transporter, strongly repressed in SNO3− roots (Table II). Other root transcripts annotated as proteins not directly related to the NO3− acquisition pathway, such as most of those encoding nonsymbiotic leghemoglobins, display a similar behavior (i.e. overaccumulated in the LNO3− roots as compared to −NO3− roots and SNO3− roots; Supplemental Table S5). However, the above dual regulation was not a systematic feature of N signaling in the roots, because a large majority of genes responding to systemic signals of N status (781 out of 937) did not display differential response in the LNO3− versus −NO3− comparison. Interestingly, the Medicago gene closely related to AtNRT2.5 described below also belongs to this large group of genes, because it displays inverse variations in the LNO3− versus −NO3− and LNO3− versus SNO3− comparisons (Table II). Conversely, among the 1,575 NO3−-responsive genes, 1,419 did not display differential expression in the LNO3− versus SNO3− comparison (the three transcripts encoding ClC channels described below belong to this category; see Table II).

Genome-Wide Transcriptional Reprogramming Associated with Systemic N Signaling in NH4+-Fed Plants and N2-Fixing Plants

Large-scale molecular responses associated with systemic repression of root N acquisition by high N status in NH4+-fed plants and N2-fixing plants (see Fig. 1B) were investigated following a similar strategy to that used for NO3−-fed plants. Many typical NO3−-regulated genes identified in the shoots of NO3−-fed plants were also found to be differentially expressed in the L and S shoots of NH4+-fed plants and N2-fixing plants (Supplemental Tables S5 and S6; Table II). The marked response observed in NH4+-fed plants and N2-fixing plants was easily explained by the fact that both NH4+-fed plants and N2-fixing plants have been deprived of NO3− for 4 d before the experiments, thus amplifying the effect of high NO3− supply in the S treatment. Accordingly, shoot NO3− content was strongly increased in SNH4+ shoots as compared with LNH4+ shoots, where only residual NO3− remains accumulated after 8 d on NO3−-free solution (Fig. 2B).

The root molecular responses associated with the systemic repression of root N acquisition were investigated by comparing the transcriptomes of the untreated roots belonging to either L or S plants (LNH4+ versus SNH4+ and LN2 versus SN2; see Supplemental Tables S7 and S8, respectively). In total, 700 genes were found to be differentially expressed between LNH4+ roots and SNH4+roots (353 up-regulated and 347 down-regulated; Table I), and 1,235 genes were found to be differentially expressed between SN2 roots and LN2 roots (376 up-regulated and 859 down-regulated; Table I). Taking into account both the number of differentially expressed genes and the intensity of the variations, roots supplied with NH4+ displayed a weaker response than roots supplied with NO3− or nodulated roots fixing N2 (Table I). Surprisingly, despite the marked repression of NH4+ uptake in untreated roots of S plants (Fig. 1B), the accumulation of transcripts annotated as enzymes involved in NH4+ assimilation (Gln synthetase, Glu synthase, Asn synthetase) or as NH4+ transporters of the AMT1 family, expected to be involved in NH4+ acquisition (Loque and Von Wiren, 2004), were not significantly modified in SNH4+ versus LNH4+ roots (Table II). The strongest transcriptome response occurred in roots of N2-fixing plants (LN2 versus SN2 comparison); both the number of genes and the intensities of variation were larger than those observed with NO3−-fed roots (Table I). More than 200 transcripts annotated as associated to nodule, such as early and late nodulins, were down-regulated in SN2 roots as compared to LN2 roots, indicating that the symbiotic fixation apparatus is probably a major target of systemic signaling of N status (Supplemental Table S9). This large group contains many transcripts expected to be related to nodule structure, function, and N2 fixation. This group includes 10 transcripts encoding symbiotic leghemoglobins, a transcript encoding a MtN6/Gln synthetase-I-like protein (Mathis et al., 2000), and two transcripts encoding the nodule-26-like protein, a membrane intrinsic protein proposed to be involved in NH4+ transport in the peribacteroid membrane of the nodule (Wallace et al., 2006). Interestingly, this nodule-related group also includes transcripts annotated as protein involved in signaling in the early stages of nodule formation such as MtLYK3, a nod factor receptor (Smit et al., 2007), MtNSP1, a GRAS TF (Smit et al., 2005), and a protein homologous to LjNIN that is involved in nodule inception in Lotus japonicus (Marsh et al., 2007). This suggests that the regulation exerted by the N status of the plant may also target nodule development processes.

The N Source Has a Predominant Effect on the Genome-Wide Transcriptional Reprogramming Triggered by Systemic Signaling of N Status

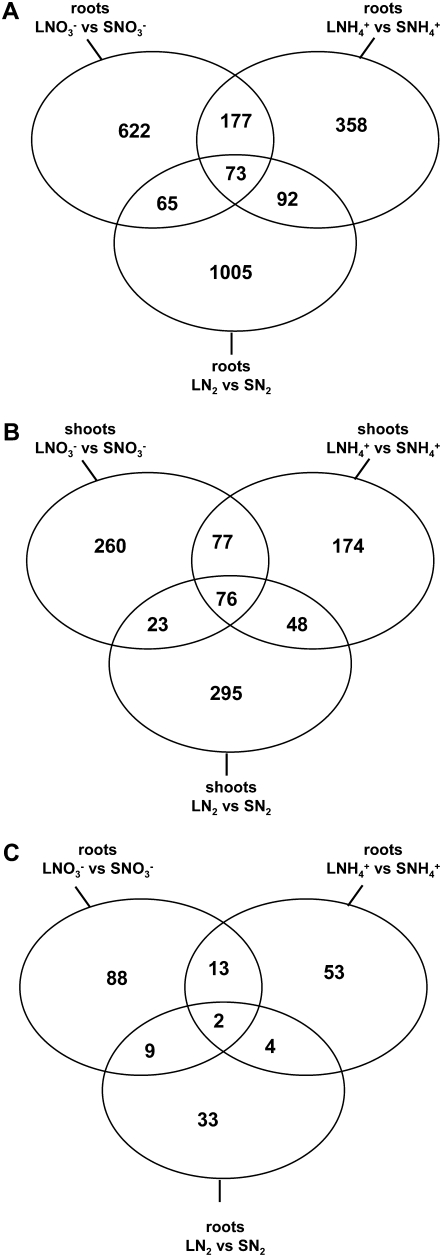

A striking observation resulting from the comparison of the various transcriptomes obtained in either NO3−-fed, NH4+-fed, or N2-fixing plants is that there is only a very small proportion of the genes responding in common to the N treatments in the three groups of plants (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S10). Thus, although the systemic repression of root N acquisition in untreated roots occurred whatever the N source, the molecular responses associated with this repression were mostly specific for each N source. Even more surprising, this was also evidenced in the shoots, indicating that the way the aboveground part of the plant perceives changes in N status is strongly dependent on the type of N nutrition. These data do not provide strong support for the hypothesis of common regulatory mechanisms governing root N acquisition regardless of the N source but rather suggest that specific gene networks are associated with the control of NO3− uptake, NH4+ uptake, or N2 fixation by the N status of the plant. In keeping with this argument, specific subsets of TF genes are modulated by the N sufficiency versus N limitation treatments as a function of the N source (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Table S11).

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams of genes identified as differentially expressed in experiments described in Figure 1. A, Roots. B, Shoots. C, Genes annotated as TFs differentially expressed in roots.

To gain further insight regarding these specific gene networks in the roots, we developed two complementary approaches. First, we used the MAPMAN software (Thimm et al., 2004) to improve the functional classification of the differentially expressed genes (see “Materials and Methods”). Secondly, we performed hierarchical clustering to identify groups of genes coordinately regulated across the various data sets. The MAPMAN-assisted analysis allowed us to subdivide genes in functional groups that may be specifically responsive to a change in N status in the presence of one particular N source. Some of these groups were already identified by a direct analysis. For instance, nodulin transcripts were predominantly responsive in N2-fixing plants (Supplemental Table S9), while transcripts involved in the process of NO3− reduction (including those of the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway) were predominantly responsive in NO3−-fed plants (Table II). Although perfectly consistent with the known effects of each N source, these observations explained only a limited fraction of the specificity. Other gene classes were also found to respond more markedly for some types of nutrition (Supplemental Tables S12 and S13). This included in particular, genes encoding receptor-like kinases or genes related to hormone metabolism in NO3−- and N2-fed plants as compared to NH4+-fed plants, flavonoid-related genes in NO3− fed plants as compared to NH4+- and N2-fed plants, or genes related to cell wall and cellular organization for N2-fixing plants as compared to NH4+- and NO3−-fed plants. Finally, even in functional classes displaying little difference in the number of differentially expressed genes between the three types of plants, the identities of the genes involved in the responses in each group were frequently different (Supplemental Tables S12 and S13). Hierarchical clustering allowed the definition of groups of transcripts displaying a common response to the various factors (Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). The colocalization of genes in a same cluster may suggest that they may be involved in the same type of functional response. Interestingly, some of these groups correspond to functional groups revealed by the MAPMAN-assisted analysis; for example, among genes displaying a response to systemic signaling in NO3−-fed plants (LNO3− versus SNO3− comparison), NO3− assimilation genes and auxin-related genes are clustered together (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Only NO3− Allows Efficient Whole-Plant Compensatory Response to Local N Deprivation

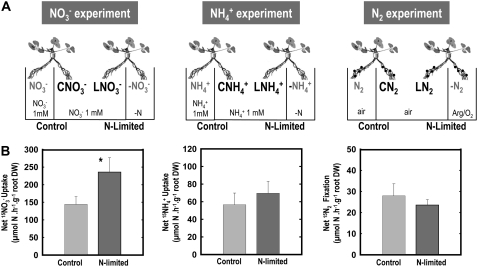

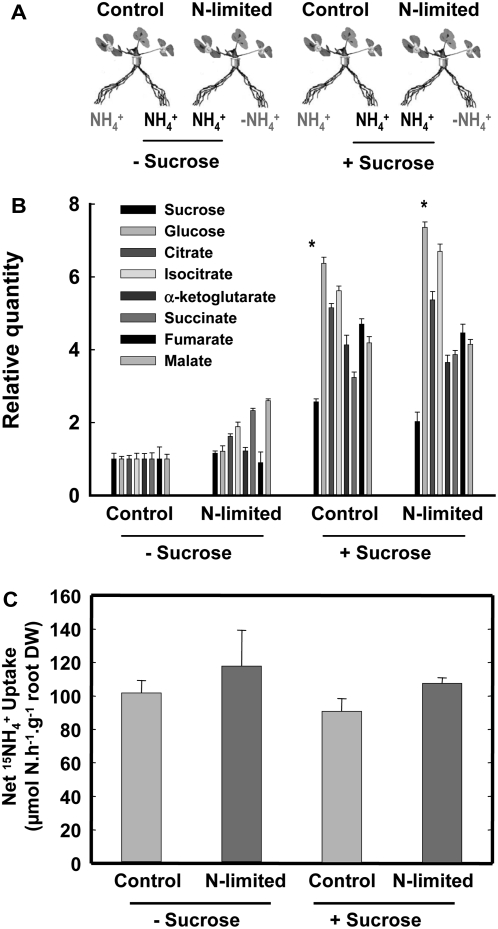

The above experiments allowed the association of each N source to a specific pattern of molecular responses involved in the general repression of root N acquisition by high N status of the plant. To further characterize this association between physiological and molecular responses, we then investigated the effect of other treatments, for which we suspected a differential effect on root N acquisition, depending on the N source. Our previous results with Arabidopsis showed that in comparison with control split-root plants supplied with 1 mm NO3− or 1 mm NH4+ on both sides of the root system, plants subjected to N starvation on one side of the root system (same treatment as the above L plants) display a strong compensatory up-regulation of root N uptake in the untreated roots with NO3−, but not with NH4+, as an N source (Gansel et al., 2001). In both cases, however, suppression of root N uptake in treated roots is expected to lower the N status of the plant. This suggested that in this situation, only the NO3− uptake system was fully responsive to the systemic signaling of whole-plant N status or that this signaling predominantly occurred in NO3−-fed plants. We investigated whether this was also the case in Medicago and extended the study to N2-fixing plants (Fig. 4A). For each N source, L plants subjected for 4 d to N starvation on one side of the root system (same treatment as previously described in Fig. 1A) were compared to untreated plants (hereafter called control plants) left with the same N nutrition regime on both sides of the root system (either 1 mm NO3−, 1 mm NH4+, or air). As expected, N limitations treatments were associated to decreases of the N content in the L roots and in shoots but had little effect on the untreated roots (Supplemental Table S14). Comparisons were done between the untreated roots of L plants and the roots of control plants that were supplied with a same N source (i.e. LNO3− versus CNO3−, LNH4+ versus CNH4+, LN2 versus CN2). Root N acquisition was measured using 15NO3−, 15NH4+, or 15N2 as tracers (Fig. 4B). As anticipated, in NO3−-fed plants, the local N deprivation resulted after 4 d in a 70% increase of 15NO3− uptake rate in the untreated roots as compared to control plants. However, no such response was found for NH4+- or N2-fed plants; 15NH4+ uptake rate in the untreated roots was slightly increased by N limitation, and similar rates of 15N2 fixation were observed in the CN2- and LN2-nodulated roots. As in Arabidopsis, the NO3− uptake system of Medicago plants thus has the ability to compensate a local N deprivation by a marked stimulation in the other parts of the root system. This observation is extremely surprising, because our comparison between S and L plants showed that the acquisition of the three N sources by the root system can actually be under the control of systemic signals of N status of the whole plant (Fig. 1). By comparing the data of both experiments (Figs. 1 and 4), it appears that, in reference to control plants, NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation can be repressed in response to high N supply (S plants) but not de-repressed in response to local N starvation (L plants). This suggests that NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation rates were already at their maximum in control plants and that no additional stimulation could be obtained in response to local N starvation. One hypothesis to explain this result is that NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation in control plants is ultimately limited by carbon availability in the roots and not by the feedback repression exerted by the N status of the whole plant. Indeed, because NH4+ originating from the external medium or the peribacteroid space is mostly assimilated in the roots, any stimulation of either NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation has to be associated with an increased availability of carbon metabolites in the roots to be used as carbon skeletons for the synthesis of amino acids (Givan, 1979; Vance and Heichel, 1991; Schjoerring et al., 2002). Therefore, the absence of compensatory up-regulation of both NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation in untreated roots of L plants might result from insufficient provision of photosynthates. We addressed this question in NH4+-fed plants by performing the same experiments as above but with or without the supply of 1% Suc to the untreated roots (Fig. 5A). The exogenous supply of 1% Suc markedly increased the root concentrations of most carbon metabolites (especially the sugars and carboxylic acids; Fig. 5B) but failed to allow the up-regulation of NH4+ uptake in the untreated roots of L plants as compared to control plants (Fig. 5C). This indicates that the availability of carbon skeletons in the roots was not the limiting factor preventing the adaptive response of NH4+ uptake to local N limitation.

Figure 4.

Comparison of control and L plants. A, Description of the three types of split-root systems. Hydroponically grown plants fed with either 1 mm KNO3, 1 mm NH4Cl, or fixing N2 were subjected for 4 d to two N regimes. In control plants, this same regime was maintained on both sides of the root system (C roots). In L plants, the N source was removed to the treated side of the root system (−N roots) as described in Figure 1. C and L roots were continuously exposed to the same local environment during the treatment. B, NO3−, NH4+, and N2 acquisition of the C and L roots. From the left to the right are: net NO3− intake of CNO3− and LNO3− roots, net NH4+ intake of CNH4+ and LNH4+ roots, net N2 intake of CN2 and LN2 roots. The values are the means of six replicates of one biological repeat. They are representative of three independent biological repeats. Vertical bars indicate sd. *Significant difference according to t test (P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Effect of the addition of exogenous Suc on the response of the roots of NH4+-fed plants to N limitation. The CNH4+ and LNH4+ roots of NH4+-fed plants described in Figure 5 were supplied with 1% Suc during the N limitation treatment: general presentation of the split-root experiment (A); main sugars and organic acids relative content (B); net NH4+ intake (C). The values are the means of six replicates. Vertical bars indicate sd. *A significant difference was found for all compounds between Suc treated and untreated organs according to t test (P < 0.001).

Correlation between Molecular and Physiological Responses of the Roots to Changes in the N Status of the Plant

The transcriptome data described in the first part of this study allowed us to associate, for each N source, large sets of genes responding to the variations of the N status of the plants (N limitation versus N sufficiency). Whether the responses of these genes play a physiological role in the response of root N acquisition remains to be elucidated. However, the comparison between control and L plants offers the opportunity to investigate the regulation of these genes in plants displaying either a strong functional response to a change in N status (NO3−-fed plants) or not (NH4+-fed and N2-fixing plants). To address this point, three subsets of candidate genes regulated by whole-plant signaling of N status (N limitation versus N sufficiency) were selected from the NO3−, NH4+, and N2 data sets (37, 29, and 25 transcripts, respectively; for details see Supplemental Table S14). For each type of nutrition, the expression of the corresponding subset of candidate genes was monitored by Q-RT-PCR in the untreated roots of control and limited plants (Supplemental Table S15). In NO3−-fed plants, a high proportion (50%) of the tested genes were found to be differentially regulated between LNO3 and CNO3 roots. Among these genes, homologues of AtNRT2.1 and AtNRT1.1 NO3− transporters were found to be up-regulated in L roots as compared to control roots. Transcripts annotated as related to hormonal regulation were also differentially expressed, for example: three transcripts encoding auxin-induced proteins (Busov et al., 2004), one encoding a sulfotransferase potentially involved in brassinosteroid signaling (Marsolais et al., 2007), and one encoding a gibberellin 2-oxidase. Analysis of the two other subsets of candidate genes in NH4+-fed and N2-fixing plants revealed that only a low or very low proportion of these genes (25% and 5%) were differentially regulated (LNH4+ versus CNH4+ and LN2 versus CN2 comparisons, respectively). Depending on the N source, a large proportion of candidates genes was differentially expressed in plant displaying the compensatory up-regulation of root N uptake (i.e. with NO3−), while in the absence of a functional response of the N acquisition system (i.e. with NH4+ or N2), the selected genes were predominantly unaffected. Thus, a strong correlation was found between the functional response of N acquisition and the molecular responses illustrated by the expression of the selected candidate genes.

DISCUSSION

Many studies concerning the regulation of root N uptake, predominantly conducted with NO3− as the N source, have resulted in a general model for the adjustment of the N acquisition capacity to the N demand of the plant (Cooper and Clarkson, 1989; Parsons et al., 1993; Imsande and Touraine, 1994). According to this model, the early steps of N acquisition that occur in the roots are under negative feedback control by the N status of the whole plant. This implies that a satiety signal is translocated from the shoots to the roots, where it triggers transduction pathways, resulting in the down-regulation of systems involved in N acquisition. In this study, we showed that in the model legume M. truncatula, not only root NO3− uptake, but also root NH4+ uptake and nodule N2 fixation are under the control of systemic signals related to the N status of the whole plant. This raised the possibility of a common regulatory mechanism involved in the control of the three pathways of N acquisition.

To gain further insight regarding this hypothesis, the effect of large variations of the N status of the whole plant on gene expression in roots fed with NO3−, NH4+, or N2 were compared. Genes responding to systemic signaling have been identified by comparing roots exposed to the same environment but belonging to L or S plants in order to identify common or specific molecular responses. Further investigations using different NO3− and NH4+ concentrations and various time points remain to be done to determine concentration and time-dependent kinetics of these responses. Among the large number of transcripts differentially accumulated, those known to be directly involved in root N acquisition displayed a response very consistent with the repression of N intake by a satiety signal. In the NO3−-fed root comparison, many genes involved in NO3− assimilation were found to be differentially expressed between LNO3− and SNO3− roots. Among those genes, the closest Medicago homolog of AtNRT2.1 is of particular interest. In Arabidopsis, AtNRT2.1 is a major component of the high-affinity root NO3− uptake system and is strongly regulated at the mRNA level by the N status of the plant (Cerezo et al., 2001; Li et al., 2007). Thus, the observation that the putative Medicago AtNRT2.1 ortholog is repressed, along with 15NO3− uptake, in NO3−-fed roots in response to the supply of 10 mm NH4NO3 on the other side of the root system strongly suggests that it constitutes, as AtNRT2.1, a key molecular target of the systemic signals regulating root NO3− uptake. In addition, many transcripts encoding enzymes involved in NO3− assimilation and organic acid metabolism (nitrate reductase, Gln synthetase, Glu synthase, Asn synthetase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, malate dehydrogenase) were also down-regulated in S roots, indicating that the whole pathway is under systemic regulation by the N status of the plant. These results are consistent with the data obtained in Arabidopsis, suggesting that many genes encoding proteins involved in NO3− assimilation are under feedback repression by downstream N metabolites (Scheible et al., 2004). However, the response is not restricted to the NO3− assimilation pathway, because many other genes belonging to a large range of functional classes are also differentially expressed in response to systemic signals. Among them, many genes were found to be related to auxin, cytokinin, or ethylene signaling, suggesting that developmental responses are also targeted by the systemic signal. An analogous situation was found in N2-fixing plants, where a large number of proteins expected to be involved in nodule development and function (early and late nodulins, leghemoglobins) were down-regulated in S plants in parallel with the reduction of N2 fixation capacity. The molecular responses of NH4+-fed roots to systemic signals are surprising, because very few changes were observed for transcripts involved in NH4+ transport or assimilation, despite the strong inhibition of root NH4+ uptake. A regulatory step operating at the protein level might explain this discrepancy. Consistent with this hypothesis, posttranslational mechanisms regulating AMT1 transporters have been recently identified (Loque et al., 2007). Besides genes encoding structural proteins involved in N transport or assimilation, many genes belonging to a large range of functional classes were differentially expressed between L and S roots (in the case of all three N sources). Although some of these data may be explained by the tight connection between the functions of these genes and the N acquisition pathways (e.g. specific steps of C metabolism providing reducing power for NO3− reduction in NO3−-fed roots, for example), many others merit additional work to facilitate a full understanding.

The differentially accumulated transcripts displaying a common response to systemic signals in NO3−-, NH4+-, or N2-fed roots also deserves further attention, because they may correspond to some common components of the N status signaling pathways. Intriguingly, transcripts encoding enzymes involved in trehalose metabolism belong to this category. This metabolite already has been proposed to play a role of signal molecule in modulating carbon metabolism, especially in response to NO3− (Scheible et al., 1997; Wang et al., 2003; Lunn et al., 2006; Stitt et al., 2007). Nevertheless, in contrast to the fact that high N supply (10 mm NH4NO3) of one side of the root system triggers systemic repression of the N acquisition on the other side, the molecular responses associated with this repression were mostly specific of the N source present locally. For example, although NO3−, NH4+, and N2 assimilation share common enzymatic steps in the roots, transcripts encoding the corresponding proteins were regulated by systemic signaling in NO3−-fed roots but not in NH4+-fed and N2-fed roots. Furthermore, even when a functional category displays a similar response to systemic signaling for the three types of nutrition, in most cases, the genes involved in these responses were specific to the local N source. Therefore, the local environment of the root somehow has a major impact on the identity of the genes regulated by systemic signaling of N status in the roots and shoots. Specific responses depending on the N source were also observed in the shoots. Furthermore, in the case of NO3−-fed plants, most of the molecular responses identified in the SNO3− versus LNO3− comparison were maintained in the SNO3− versus −N comparison (data not shown). This suggests that the whole plant reacts to a common treatment (supply of 10 mm NH4NO3 on one side of the root system) in an N source-specific manner. One simple explanation might be that the different systemic responses are due to separate regulatory pathways. These signaling pathways might be differentially modulated in response to changes to the whole-plant N status of the plant according to the N source present in the environment of the root. Alternatively, the specific responses might result from the interactions of two signals, one originated from the N status of the plant common of all treatments and the other specific of the N source. Interestingly, there is evidence indicating that a systemic regulatory mechanism related to NO3− itself may be involved in regulating plant development (Scheible et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1999; Forde, 2002b). However, whether such mechanisms may determine the specificity of the responses of the plant in interaction with others involved in the sensing of downstream N metabolites remains to be clarified.

Systemic regulation of N acquisition by downstream products of N assimilation at the whole-plant level is interpreted as a way for the plant to adjust its N intake to its nutritional demand. This mechanism is expected to be of great importance in the case of a localized N limitation of the root system, because de-repression may allow the plant to compensate the deficit by increasing the acquisition capacity of the other roots still correctly supplied with N and, finally, may thus allow the whole plant to maintain its ability to grow. In this study, we show that such adaptive response to local N limitation occurs efficiently only with NO3− as N source. These results confirm the earlier report indicating that in Arabidopsis, the NH4+ uptake system was not able to compensate a local N limitation (Gansel et al., 2001). The absence of adaptive responses of NH4+ and N2 acquisitions to N limitation correlate at the molecular level with a lack of responses of genes identified as differentially expressed in L and S roots. The strong association between molecular and physiological responses argues that these genes are involved in the functional response rather than merely as part of a general stress response due to N shortage. However, direct evidence using reverse genetics needs to be obtained to directly demonstrate their potential role in the functional response of the plant. Root assimilation of NH4+, originating either from the external medium or from N2 fixation, requires an important flux of carbon skeletons from the shoot to the roots. This could potentially be, therefore, a limiting factor for the up-regulation of both NH4+ uptake and N2 fixation in response to local N limitation. However, as evidenced by the Suc supply experiment, this does not seem to be the case here. Thus, the hypothesis that the mechanisms governing NH4+ uptake or N2 fixation may respond differently to N limitation as compared to those involved in the control of NO3− uptake cannot be excluded. An alternative hypothesis is that the root capacity to acquire N from either NH4+ or N2 may be more limited than in the case of NO3−. As a matter of fact, plants supplied homogeneously with 1 mm NO3− had a higher level of N intake and higher N content than plants supplied with 1 mm NH4+ or nodulated plants fixing N2 (Supplemental Table S16). This suggests that even in the absence of N limitation treatment, root N acquisition from NH4+ uptake or from nodule N2 fixation is not able to fulfill the nutritional demand of the plant. As a consequence, if root N acquisition is already up-regulated in NH4+-fed or N2-fixing control plants, further N limitation due to N deprivation on one side of the root system may not result in an additional increase in N intake, whereas high N supply will lead to repression, as in NO3−-fed plants. The physiological consequences of these differences in the plant ability to adapt to local N limitation as a function of the N source are important. In soils, heterogeneous and fluctuating conditions are commonly found, and, therefore, plant root systems are almost continuously submitted to local N limitation because of low N availability in some areas or because the local environmental conditions are unfavorable to N acquisition (abiotic or biotic stress). For example, water deficit is frequently encountered by roots in some soil areas (especially the upper parts) and strongly inhibits nodule activity in the roots present in this zone (Durand et al., 1987; Serraj et al., 1999; Marino et al., 2007). Under such conditions, the root NO3− uptake system seems to have a unique ability to allow the plant to compensate the N deficit by stimulating NO3− acquisition in the roots experiencing a more favorable environment. This better adaptability of NO3− uptake might contribute to explain why, in the long term, NO3− is frequently the preferred N source of herbaceous species, even in legumes.

This study focused on short-term responses of roots to variation of the N status of the plant. These responses mostly occur through changes regarding the capacity of preexisting structures to acquire N (roots or nodule). However, many of the molecular responses characterized by our transcriptomic studies revealed genes involved in hormonal and developmental processes, suggesting that long-term responses modulating the size (i.e. biomass) of the structures responsible for N acquisition (roots or nodules) are also initiated rapidly. It is well known that variations of the N status induce developmental responses aimed at modifying root architecture. For example, NO3− plays an important role in root initiation and elongation (Forde, 2002a). This strongly contributes, together with short-term modulations of root uptake systems, to the integrated response of the whole plant to changes in NO3− availability (Forde, 2002b). In legumes, the supply of N2-fixing plants with high levels of NO3− is known to inhibit nodule development (Carroll and Mathews, 1990; Kinkema et al., 2006). Systemic signaling is likely to have a strong impact on root and nodule development; the characterization and comparison of pathways involved in their control by the N status of the plant deserve further investigations. Whether the mechanisms controlling the development of new structures for N acquisition are entirely connected or independent to the mechanisms controlling the activity of these structures remains to be determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth Conditions

Seeds of Medicago truncatula genotype A17 were chemically scarified in H2SO4 95% for 8 min, cold-treated at 4.0°C in water for 48 h, and then placed at room temperature in the dark for germination. After 4 to 6 d, the primary root tips were cut to promote branching of the root system. Individual plantlets were transferred onto hydroponic culture tanks containing a vigorously aerated basal nutrient solution containing 1 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm MgSO4, 0.25 mm K2SO4, 0.25 mm CaCl2, 50 μm KCl, 30 μm H3BO3, 5 μm MnSO4, 1 μm ZnSO4, 1 μm CuSO4, 0.1 μm (NH4)6Mo7O24, and 0.1 mm Na-Fe-EDTA, pH 5.8, supplemented with 1 mm KNO3 as an N source. Plants were grown under the following environmental parameters: 8-h/16-h light/dark cycle, 250 μmol s−1 m−2 photosynthetically active radiation light intensity, 22°C/20°C day/night temperature, and 70% hygrometry. Nutrient solutions were renewed every week. Nodulated plants were obtained by transferring 3-week-old plants to a nutrient solution with lower KNO3 concentration (0.5 mm) but containing the strain 2011 of Sinorhizobium meliloti. Typically, nodules appeared after 4 to 6 d and were fully functional after 2 weeks.

For split-root experiments, the root systems of 5-week-old plants were separated into two parts, each side being installed in a separate compartment filled with the same basal nutrient solution either supplemented with 1 mm KNO3 (NO3− experiments) or with 1 mm NH4Cl (NH4+ experiments) or left without mineral N (nodulated plants). After 4 d, differential N treatments were initiated that consisted of modifying the N provision to one side of the root system by either supplying these roots with a nutrient solution containing 10 mm NH4NO3 (S plants) or by removing the N source from the environment (L plants). For plants fed with NO3− or NH4+, the N limitation treatment was performed by supplying plants with N-free nutrient solutions. For nodulated plants, N limitation was achieved by removing N2 from the treated compartment by a continuous flow of 80% argon/20% O2. In all groups of plants, the other side of the split-root system was untreated and remained exposed to the same nutrient solution and gaseous environment as before. The nutrient solutions were renewed daily. For Suc treatments, the nutrient solution was supplemented with 1% Suc and 50 mg L−1 penicillin and 25 mg L−1 chloramphenicol.

15N Labeling and Metabolite Measurements

The net intakes of 15NO3−, 15NH4+, and 15N2 were assayed on the untreated side of the split-root system. Roots of nonnodulated plants were exposed to basal nutrient solution supplemented with 1 mm 15NO3− or 1 mm 15NH4+ (99 atom% 15N) for 4 to 6 h and washed for 1 min in 0.1 mm CaSO4. Then, all organs of each plant were collected, dried at 70°C for 48 h, weighed, and analyzed for total 15N content using a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Isoprime mass spectrometer; GV Instruments) coupled to a nitrogen elemental analyzer (Euro vector S.P.A). 15N2 fixation measurements were done on freshly excised nodulated roots placed in air-tight 10-mL tubes containing 2 mL of basal nutrient solution. Ten minutes of labeling was achieved by replacing in each tube 5 mL of air with 5 mL of 80% 15N2/20% O2 mix (99 atom% 15N). Samples (100 μL) of 15N2-enriched air were harvested at the beginning and end of the labeling for precise analysis of the atom% 15N of the 15N2 source and leak check. After labeling, nodules were separated from roots, and both organs were dried and analyzed as described above. This method gave, in our system, equivalent values for 15N2 fixation as those obtained with measurements on intact plant roots described in Voisin et al. (2003; data not shown).

Nitrate was extracted from dried tissues in water at 4°C for 24 h. Nitrate concentration was determined colorimetrically in the presence of sulfanilamide and N-naphtyl-ethylene diamine-dichloride after reduction of NO3− to NO2− on a cadmium column using an autoanalyzer (Brann-Lubbe). Metabolite profiling was performed on 100 mg of root tissue as described in Wagner et al. (2006).

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from frozen samples using Tri-Reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). DNA contamination was eliminated by a DNAse I digest (QIAGEN) and absence of genomic DNA in RNA samples was verified by Q-RT-PCR using intron-specific primers (Mt-Ubi-IntronF/R; Supplemental Table S16). Samples were further purified using Rneasy MinElute Cleanup kit (QIAGEN). Equal amounts of RNA from six individual plants of each experiment were pooled to constitute one biological replicate. For microarray analysis, additional controls of RNA preparations were carried out with the Agilent Bioanalyser 2100 using RNA 6000 NanoChips (Agilent Technologies).

Affymetrix GeneChip

Affymetrix GeneChip Medicago Genome Array contains over 61,200 probe sets: 32,167 based on the EST/mRNA and chloroplast gene sequences of M. truncatula, 18,733 based on the partial genomic sequence of M. truncatula (International Medicago Genome Annotation Group and phase 2/3 Bacterial Artificial Chromosome prediction); 1,896 based on the EST/mRNA sequence of Medicago sativa, and 8,305 based on the genomic sequence of S. meliloti (http://www.affymetrix.com/products/arrays/specific/medicago.affx). Although several probe sets may target the same gene, each Medicago probe set will be designed as a “gene” in the text for simplification. A total of 26 samples have been analyzed: two biological replicates of the 13 different types of shoot and root samples described in Figure 1A. The Affymetrix GeneChip experiments were performed in two laboratories: root transcriptomes at the URGV Plant Genomics Research Unit (Evry, France; http://www.versailles.inra.fr/urgv/microarray.htm) and shoot transcriptomes at the Curie Institut (Paris; http://www.curie.fr). For each sample, 2 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize biotin-labeled cRNAs using the Affymetrix Eukaryotic One-Cycle Target Labeling kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix). The amount of labeled cRNA was determined with RiboGreen RNA Quantification Reagent (Turner Biosystems). Hybridization (15 μg cRNA/array), washing, staining, and scanning Medicago genome arrays were carried out as recommended by the manufacturer's instruction manual (Affymetrix). Affymetrix gene chip data were normalized with the gcrma algorithm (Irizarry et al., 2003) available in the Bioconductor package (Gentleman et al., 2004). This method combines the stochastic model algorithm RMA (based on the quantile normalization method) and the physical model. To determine differentially expressed genes between two conditions, we performed a two-group t test assuming equal variance between groups. The variance of the gene expression per group is assumed to be homoscedastic, and, therefore, to fit this hypothesis, genes displaying extreme variations (too small or too large) were excluded from the analysis. The raw P values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method, which controls the family wise error rate. A gene was declared differentially expressed if the Bonferroni P value was <0.05. Finally, to test the robustness of the gene chip strategy, a set of 40 genes identified as differentially expressed in roots was randomly selected for validation in a third biological replicate. Q-RT-PCR was performed and showed good agreement with data obtained with the Affymetrix genome arrays (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Q-RT-PCR

High-throughput expression profiling of the M. truncatula TFs were performed on three independent biological replicates (two were common to the Affymetrix GeneChip experiments). The resource developed in the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Plant Physiology of Golm consists of a collection of specific primers that allow the monitoring of the accumulation of 752 M. truncatula transcripts annotated as encoding TFs by Q-RT-PCR (Udvardi et al., 2007; K. Kakar and M. Udvardi, unpublished data). RNA samples, cDNA synthesis, quality control, and Q-RT-PCR were performed as described by Czechowski et al. (2004). Efficiency of cDNA synthesis was systematically assessed by Q-RT-PCR of the UBQ10 transcript (TC102473) with primer pairs designed in central and distal regions on the cDNA sequence (Mt-Ubi-exonF/R, Mt-Ubi-3′F/R, Mt-Ubi-5′F/R; Supplemental Table S16). Only cDNA preparations that yielded similar Ct values with the various primer sets were used for comparing TF transcript levels. Then, Q-RT-PCR were performed using the 752 Medicago TFs primers and eight housekeeping genes. The Ct values for all TF genes were normalized to the Ct value of UBQ10, which was the most constant of the eight housekeeping genes included in each PCR runs. Data were analyzed using the SDS 2.2.1 software (Applied Biosystems) as described by (Czechowski et al., 2004). The PCR primer efficiency (E) of each primer pair was estimated from the data obtained from the exponential phase of each individual amplification plot according the equation (1 + E) = 10slope. Primer pairs with E values < 0.8 or with an R2 value < 0.995 were excluded from the analysis. The normalized Ct values were used in a Student's t test to determine if transcripts were differentially accumulated (P-value cutoff 0.05). The fold-change value in transcript level between samples from L and S plants was estimated by the equation (1 + E)(ΔCL-ΔCS), where E is the average PCR efficiency, and ΔCL and ΔCS represent the average normalized Ct values of L and S samples, respectively.

Low throughput Q-RT-PCR were performed in a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics) as previously described (Girin et al., 2007). Primers specific to the Clathrin transcript (TC107843) were used to normalize the data (Supplemental Table S17).

Functional Annotation and Hierarchical Clustering

To improve and homogenize the annotation of the differentially expressed genes identified by the GeneChip study, the Medicago sequences were compared to SwissProt, Tair 6 protein databases using National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) blastx software, and to the Interpro database using Interproscan. For each Medicago sequence, the most similar Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) protein was searched. Then a functional classification of the differentially expressed Medicago transcripts based on similarities with Arabidopsis proteins was performed using MAPMAN software (Thimm et al., 2004; Usadel et al., 2005). This yielded 1,667 Arabidopsis proteins that corresponded to 2,452 of the original 3,007 M. truncatula proteins (some match the same Arabidopsis protein or have no Arabidopsis homologs). The corresponding Arabidopsis genes were then submitted to Map-Man software to allow a functional classification allowing the putative classification of 2,452 differentially expressed M. truncatula genes. Hierarchical clustering of the Affymetrix data was performed using Genesis software (Sturn et al., 2002; http://genome.tugraz.at/). Genes were clustered by average linkage using the Pearson correlation.

Accession Numbers

The Affymetrix GeneChip data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus in compliance with MIAME standards (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through Gene Expression Omnibus Series accession number GSE9818. The identification numbers, sequences matches, and specific primer sets of the differentially accumulated M. truncatula TF transcripts identified by high-throughput Q-RT-PCR are provided in Supplemental Table S18.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Hierarchical clustering of root transcripts identified by the LNO3− versus SNO3− comparison, as a function of the responses to the various treatments.

Supplemental Figure S2. Hierarchical clustering of root transcripts identified by the LNH4+ versus SNH4+ comparison, as a function of the responses to the various treatments.

Supplemental Figure S3. Hierarchical clustering of root transcripts identified by the LN2- versus SN2 comparison, as a function of the responses to the various treatments.

Supplemental Figure S4. Analysis by Q-RT-PCR of the accumulation of differentially accumulated transcripts, initially identified by Affymetrix GeneChip analysis, on a third set of biological replicates.

Supplemental Table S1. Differentially accumulated root transcripts identified by the LNO3− versus −NO3− comparison.

Supplemental Table S2. Differentially accumulated shoot transcripts identified by the LNO3− versus SNO3− comparison.

Supplemental Table S3. Differentially accumulated root transcripts identified by the LNO3− roots versus SNO3− roots comparison.

Supplemental Table S4. Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by LNO3− roots versus −NO3− roots and LNO3− roots versus SNO3− roots comparisons

Supplemental Table S5. Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by the LNH4+ shoots versus SNH4+ shoots comparison.

Supplemental Table S6. Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by the LN2 shoots versus SN2 shoots comparison.

Supplemental Table S7. Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by the LNH4+ roots versus SNH4+ roots comparison.

Supplemental Table S8. Differentially accumulated transcripts identified by the LN2 root versus SN2 root comparison.

Supplemental Table S9. Nodule related transcripts differentially expressed in the LN2 versus SN2 comparison.

Supplemental Table S10. Transcripts displaying differential accumulation in NO3−-, NH4+-, and N2-fixing roots.

Supplemental Table S11. Root transcripts encoding TFs differentially accumulated in response to variations of the N status of the plant.

Supplemental Table S12. Overview of functional genes categories displaying differential responses to variations of the N status of NO3−-, NH4+-, or N2-fed plants.

Supplemental Table S13. Detailed genes categories described in Supplemental Table S12.

Supplemental Table S14. N content of control and L plants described in Figure 4.

Supplemental Table S15. Analysis of accumulation of selected transcripts in roots of L and control plants described in Figure 4.

Supplemental Table S16. Total N content of whole plants cultivated in split-root systems.

Supplemental Table S17. Primers list used for Q-RT-PCR assays.

Supplemental Table S18. Identification numbers, sequences matches, and specific primer sets of the differentially accumulated M. truncatula TF transcripts identified by high-throughput Q-RT-PCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Benoit Albaud for technical assistance in microarray hybridization and Armin Schlereth and Thomas Ott for technical assistance in high-throughput Q-RT-PCR analysis. We thank Françoise Cellier, Marinus Pilon, and Pascal Gamas for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Sixth Framework Programme Grain Legume Integrated Project of the European Union (postdoctoral grant to S.R. and S.F.), by AgroBI incitative action of INRA, and by grants from the scientific directorate “Plante et Produit du Végétal” of INRA and the French “Reseau National des Génopoles.” A.G. and M.L. were supported by the P2R French-German program.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Marc Lepetit (lepetit@supagro.inra.fr).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Bacanamwo M, Harper JE (1997) The feedback mechanism of nitrate inhibition of nitrogenase activity in soybean may involve asparagine and/or products of its metabolism. Physiol Plant 100 371–377 [Google Scholar]

- Burns IG (1991) Short-term and long-term effects of a change in the spatial-distribution of nitrate in the root zone on N uptake, growth and root development of young lettuce plants. Plant Cell Environ 14 21–33 [Google Scholar]

- Busov VB, Johannes E, Whetten RW, Sederoff RR, Spiker SL, Lanz-Garcia C, Goldfarb B (2004) An auxin-inducible gene from loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) is differentially expressed in mature and juvenile-phase shoots and encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Planta 218 916–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Mathews A (1990) Nitrate inhibition of nodulation in legumes. In PM Gresshoff, ed, Molecular Biology of Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 159–180

- Cerezo M, Tillard P, Filleur S, Munos S, Daniel-Vedele F, Gojon A (2001) Major alterations of the regulation of root NO(3)(−) uptake are associated with the mutation of Nrt2.1 and Nrt2.2 genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 127 262–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HD, Clarkson DT (1989) Cycling of amino-nitrogen and other nutrient between shoots and roots in cereals: a possible mechanism integrating shoot and root in the regulation of nutrient uptake. J Exp Bot 40 753–762 [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NM (1995) Nitrate: nutrient and signal for plant growth. Plant Cell 7 859–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NM, Glass ADM (1998) Molecular and physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants. Trends Plant Sci 3 389–395 [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T, Bari RP, Stitt M, Scheible WR, Udvardi MK (2004) Real-time RT-PCR profiling of over 1400 Arabidopsis transcription factors: unprecedented sensitivity reveals novel root- and shoot-specific genes. Plant J 38 366–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angeli A, Monachello D, Ephritikhine G, Frachisse JM, Thomine S, Gambale F, Barbier-Brygoo H (2006) The nitrate/proton antiporter AtCLCa mediates nitrate accumulation in plant vacuoles. Nature 442 939–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand JL, Sheehy JE, Minchin FR (1987) Nitrogenase activity, photosynthesis and nodule water potential in soybean plants experiencing water-deprivation. J Exp Bot 38 311–321 [Google Scholar]

- Forde B, Lorenzo H (2001) The nutritional control of root development. Plant Soil 232 51–68 [Google Scholar]

- Forde BG (2002. a) Local and long-range signaling pathways regulating plant responses to nitrate. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 53 203–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde BG (2002. b) The role of long-distance signalling in plant responses to nitrate and other nutrients. J Exp Bot 53 39–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansel X, Munos S, Tillard P, Gojon A (2001) Differential regulation of the NO3- and NH4+ transporter genes AtNrt2.1 and AtAmt1.1 in Arabidopsis: relation with long-distance and local controls by N status of the plant. Plant J 26 143–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzarrini S, Lejay L, Gojon A, Ninnemann O, Frommer WB, Von Wiren N (1999) Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 11 937–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5 R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girin T, Lejay L, Wirth J, Widiez T, Palenchar PM, Nazoa P, Touraine B, Gojon A, Lepetit M (2007) Identification of a 150 bp cis-acting element of the AtNRT2.1 promoter involved in the regulation of gene expression by the N and C status of the plant. Plant Cell Environ 30 1366–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givan CV (1979) Metabolic Detoxification of Ammonia in Tissues of Higher-Plants. Phytochemistry 18 375–382 [Google Scholar]