Abstract

Compared to chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), the onset of aging appears to be delayed in the human species. Herein, we studied human-chimpanzee orthologous gene pairs to investigate the selective forces acting on genes associated with aging in different model systems, which allowed us to explore evolutionary hypotheses of aging. Our results show that aging-associated genes tend to be under purifying selection and stronger-than-average functional constraints. We found little evidence of accelerated evolution in aging-associated genes in the hominid or human lineages, and pathways previously related to aging were largely conserved between humans and chimpanzees. In particular, genes associated with aging in non-mammalian model organisms and cellular systems appear to be under stronger functional constraints than those associated with aging in mammals. One gene that might have undergone rapid evolution in hominids is the Werner syndrome gene. Overall, our findings offer novel insights regarding the evolutionary forces acting on genes associated with aging in model systems. We propose that genes associated with aging in model organisms may be part of conserved pathways related to pleiotropic effects on aging that might not regulate species differences in aging.

Keywords: comparative genomics, life history, longevity, natural selection

1. Introduction

Genome comparisons between humans and our closest living evolutionary relatives, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), may shed light on the genetic changes involved in the evolution of the unique human traits (Watanabe et al., 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005; Varki and Altheide, 2005). A first step to understand the evolution of human features is to study the selective forces that originated them. Typically, natural selection shapes the evolution of species through one of two mechanisms: purifying selection, which promotes the conservation of existing phenotypes, and positive selection, which favors the emergence of new phenotypes (Vallender and Lahn, 2004). Despite the low sequence divergence between human and chimpanzee genes, it is possible to study these selective forces throughout the genome and identify signatures of evolutionary changes that can provide insights about the evolution of human-specific traits (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005; Nielsen et al., 2005).

The most commonly used method to study selective forces is the Ka/Ks test, where Ka and Ks represent the number of substitutions per, respectively, nonsynonymous and synonymous sites between two protein-coding sequences. Nonsynonymous mutations result in changes in the amino acid sequence of the protein while synonymous mutations do not. Although Ka gives an estimate of a gene’s rate of evolution, because mutation rates vary across the genome, Ks is used to estimate the background mutation rate and normalize Ka for gene comparisons. In the classical test, if nucleotide substitutions occur through a purely random process Ka/Ks = 1, which indicates neutral selection, Ka/Ks < 1 indicates purifying selection or structural constraints and Ka/Ks > 1 indicates, though it does not necessarily prove or disprove, positive selection. Even though post-translational and regulatory differences are impossible to detect using this method, the Ka/Ks test has proven to be a powerful and accurate tool in detecting selective pressures across groups of genes and even to provide clues about the selective pressures acting on individual genes (Clark et al., 2003; Dorus et al., 2004; Vallender and Lahn, 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005; Nielsen et al., 2005).

In this work, we studied the selective forces operating since the divergence of humans and chimpanzees 5 to 7 million years ago (Varki and Altheide, 2005). While differences in cognitive functions, speech, or bipedalism have so far received the bulk of attention in such studies (Clark et al., 2003; Dorus et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005; Nielsen et al., 2005), one major difference between chimpanzees and humans concerns life history traits: development, all growth phases, and lifespan are considerably extended in humans when compared to chimpanzees (McKinney and McNamara, 1991). Life history theory predicts that under lower adult mortality rates selection will favor a later maturity and a longer lifespan (reviewed in Charnov, 1993). Indeed, it has been estimated that the adult life expectancy of chimpanzees in the wild is about 60% less than it was for human hunter-gatherers (Hill et al., 2001). Nonetheless, little is known concerning the genetic mechanisms responsible for the evolution of human life history.

Of great interest to biomedical research is the fact that the onset of aging appears to occur at later ages in humans, even when compared to chimpanzees in captivity. Humans are longer-lived than chimpanzees, with a record longevity of 122 years compared to 74 years in chimpanzees, albeit the vastly larger sample size for humans may overestimate the difference between the two species. Importantly, humans appear to feature a delayed onset of several age-related diseases and a later acceleration of mortality, a common characteristic of aging (Finch, 1990; Hill et al., 2001; Erwin et al., 2002; Morbeck et al., 2002; Finch and Stanford, 2004; de Magalhaes, 2006). Such differences in aging might be explained by changes in extrinsic mortality rates during the evolution of hominins (herein used to refer to the lineage leading to modern humans whereas hominids refers to humans and the great apes) that possibly affect selection on the pathways that govern aging (Kirkwood and Austad, 2000). Even if such hypothesis is correct, however, and even though it is clear that genetic alterations must be responsible for the delayed onset of aging in humans (Miller, 1999; de Magalhaes, 2003; Partridge and Gems, 2006), the essence of those genetic changes remains largely unknown.

Because natural selection is the ultimate cause of aging, evolutionary biology is crucial to understand the aging phenotype (Rose, 1991). From an evolutionary perspective, aging can be seen as a polygenic and highly complex process whose phenotype changed markedly since chimpanzees and humans shared their last common ancestor. Herein, we took advantage of the recent sequencing of the chimpanzee and human genomes to investigate–using Ka/Ks ratios–the selective forces acting on genes previously related to aging in model systems, which in turn allowed us to explore evolutionary hypotheses of aging. One controversial topic in evolutionary models of aging concerns the extent to which mechanisms of aging are conserved (“public”) across diverse organisms (Martin et al., 1996; Partridge and Gems, 2002). Here, we explored whether mechanisms of aging identified in different model organisms may also specify species differences in aging (Partridge and Gems, 2006). We also investigated whether the evolution of longevity in hominins may be due to multiple changes in a wide range of defensive and repair mechanisms (Partridge and Gems, 2002; Kirkwood, 2005). Lastly, mutations in the ASPM and MCPH1 genes result in microcephaly, and evidence of positive selection in these genes in the primate lineage leading to humans has been used to hypothesize that they are involved in the evolution of brain size (reviewed in Vallender and Lahn, 2004). Following this rationale, we explored whether genes associated with premature aging phenotypes in humans may also be potential targets of positive selection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources and types of data

We employed the datasets assembled by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005), consisting of 13,454 human-chimpanzee orthologous gene pairs plus 7,043 4-way gene alignments of human, chimpanzee, mouse, and rat orthologs. The orthology of these gene alignments is considered unambiguous. Ka/Ks ratios for each alignment were previously calculated by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005) as well as estimates of lineage-specific protein changes. Given the similarity between human and chimpanzee genes, however, there will be few, and not infrequently zero, synonymous substitutions. To obviate this problem, another estimate of background mutation rates used was Ki, which is calculated based on the local intergenic/intronic substitution rate. Ka/Ki ratios have the same interpretation as Ka/Ks ratios, and Ka/Ki ratios provide an additional control for false positives when looking at individual genes. The average Ka/Ks ratio for human-chimpanzee orthologous gene pairs was 0.23. The average Ka/Ki ratio was also 0.23 with 4.4% of the genes with Ka/Ki > 1 and 29% of human and chimpanzee orthologs encoding identical proteins. For 4-way comparisons, the average Ka/Ks ratio in hominids was 0.20 while in murids it was 0.13 (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005). We also used the dataset of Clark et al. (2003), which consists of 7,645 human-chimpanzee-mouse alignments, to discriminate between selection in the chimpanzee lineage and selection in the human lineage and attempt to infer accelerated evolution in the human lineage. p-values from Model 2 in the calculations by Clark et al. (2003), which give a likelihood ratio test of rejecting the null hypothesis of no positive selection in the human lineage, were used in conjunction with the dataset of Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005).

Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), a species of Old World monkeys that diverged from apes about 25 million years ago, live up to 40 years and their onset of aging occurs at considerably earlier ages than in humans or chimpanzees; mice (Mus musculus) and rats (Rattus norvegicus), rodents that diverged from primates roughly 80 million years ago, live less than 5 years and age considerably faster than primates (Finch, 1990; de Magalhaes, 2006). To serve as an additional test, human-rhesus, human-mouse, and human-rat homolog gene pairs were downloaded from ENSEMBL v.37 (Birney et al., 2006). Ka/Ks ratios were obtained only for genes for which we had the highest confidence, and we excluded pairs such as pseudogenes and poorly-annotated genes. (Nonetheless, not eliminating gene pairs at all for any of these datasets did not significantly affect our general results and conclusions.) Overall, for 9,857 human-rhesus genes the average Ka/Ks ratio was 0.20, for 12,063 human-mouse genes the average Ka/Ks ratio was 0.13, and for 11,594 human-rat genes the average Ka/Ks ratio was 0.13. Whereas possible we also employed orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) genes to infer whether differences between human and chimpanzee proteins were due to human- or chimpanzee-lineage specific changes.

2.2. Selection of putative aging-related genes

To study genes previously related to aging, we obtained a list of 243 curated human genes, of which 242 encode proteins, associated with aging in different model systems from the GenAge dataset (de Magalhaes et al., 2005). These genes are candidates for determinants of human longevity and aging, though none of them have been proven to play a causal role in human aging and the degree of evolutionary conservation in function of genes and pathways that control aging is unclear. We also investigated a group of 14 genes that have been associated with human longevity or survival in old age. Both lists of genes are available online (http://genomics.senescence.info/evolution/chimp.html).

In addition, we used Gene Ontology (GO) annotation, which describes how gene products behave in a cellular context (Ashburner et al., 2000), to select GO categories encompassing mechanisms or functions previously associated with aging in model systems or hypothesized to be related to aging (reviewed in Martin et al., 1996; Partridge and Gems, 2002; de Magalhaes, 2005a). Briefly, we selected GO categories related to DNA repair and processing based on empirical evidence of an association between these pathways and aging in model systems (e.g., Fraga et al., 1990), including DNA repair (reviewed in Hasty et al., 2003; Lombard et al., 2005; Martin, 2005), DNA methylation (reviewed in Richardson, 2003), and protein amino acid ADP-ribosylation (reviewed in Burkle et al., 2004). Stress, oxidative stress, the electron transport chain, and hypoxia have also been hypothesized to play a role in aging (reviewed in Sohal and Weindruch, 1996; Cadenas and Davies, 2000; Finkel and Holbrook, 2000; Katschinski, 2006), as supported by experimental results from model systems (e.g., Lin et al., 1998; Migliaccio et al., 1999; Moskovitz et al., 2001). There is also abundant empirical evidence associating hormones, and neuropeptide hormones in particular, with aging in a number of model organisms (Brown-Borg et al., 1996; Flurkey et al., 2001; Tatar et al., 2003). Other aging-associated pathways in model organisms that we selected include ubiquitin (reviewed in Gray et al., 2003), heat shock proteins (Yokoyama et al., 2002), JNK (Wang et al., 2003), glutathione transferase enzymes (Ayyadevara et al., 2005), and histone deacetylase genes (Rogina et al., 2002).

2.3. Calculating average Ka/Ks ratios for gene categories

The Ka and Ks values of GO categories were taken from the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005). To calculate Ka and Ks values for other gene categories or groups, such as GenAge or a GenAge subset, we employed the method used by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005) to calculate the Ka/Ks ratio for each GO category. Values of Ka and Ks concatenated for all genes in a given category C were calculated using:

being ai and Ai the number of nonsynonymous substitutions and sites and si and Si the number of synonymous substitutions and sites per gene i in category C.

2.4. Detecting rapidly and slowly evolving gene categories

We employed the binomial probability method used by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005) to identify rapidly (i.e., with higher-than-average Ka/Ks ratios) and slowly (i.e., with lower-than-average Ka/Ks ratios) evolving GO categories. To identify other gene categories potentially undergoing rapid or slow evolution, we also employed the method used by these authors. The binomial probability is typically used to calculate the probability of several successive events, each with two possible outcomes. Herein, the events are substitutions which can be synonymous or nonsynonymous. Assuming a binominal distribution, we calculated the binomial probability as follows (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005).

The probability pA of a nonsynonymous substitution event occurring in a given category C was estimated from the expected proportion of nonsynonymous substitutions using:

where ka and ks represent average Ka and Ks values for all human-chimpanzee gene pairs. Consequently, for the total number of substitution events in category C, the probability pC that we observe an equal or higher number of nonsynonymous substitutions was calculated as:

being aC and sC the total number of nonsynonymous and synonymous substitutions in category C. Likewise, we identified slowly evolving categories by calculating the probability of observing an equal or smaller number of nonsynonymous substitutions.

This method allowed us to identify categories that have a Ka/Ks ratio significantly above or below the average. The binomial probability does not allow a direct rejection of the null hypothesis of no acceleration or no constraint in a particular category. Instead, it is a metric designed to detect the most extreme outliers that are potentially undergoing rapid or slow evolution. Based on simulations conducted by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), its cut-off value was set at 0.001. With test statistic < 0.001, 98 GO categories were found to feature elevated Ka/Ks ratios but only 30 would be expected by chance. This means that most, but not all, of these categories have undergone rapid evolution when compared to the genome-wide average. Similarly, 251 GO categories were found to feature lower Ka/Ks ratios when only 32 would be expected by chance (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005).

2.5. Genome coverage

Because the dataset of the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005) is derived from a draft sequence of the chimpanzee genome, not all human genes have been matched to orthologs in the chimpanzee genome and so our results should not be considered as comprehensive. For instance, of GenAge’s 242 protein-coding genes, 211 could be correctly analyzed. Similarly, of GenAge’s 242 protein-coding genes, we obtained 169 human-rhesus, 216 human-mouse, and 205 human-rat gene pairs that could be correctly analyzed. Therefore, genes of potential interest may have been left out of our analysis, but trends in groups–such as GO or GenAge categories–with a large number of genes are unlikely to change even when complete results are available.

2.6. Computational and statistical analyses

To retrieve the genes of interest and analyze our results, we designed and implemented an automated system of modules written in Perl. The system is part of the Ageing Research Computational Tools (ARCT, described in de Magalhaes et al., 2005) and is used to retrieve, parse, and data-mine the different datasets used in this work: the datasets of the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), the GenAge dataset, and the dataset of Clark et al. (2003). The system then generates a new set of results, such as Ka/Ks ratios for each GenAge category, which can be statistically analyzed.

As mentioned above, we employed the statistical tests used by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), which were also the ones used in similar works (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2005). The Mann-Whitney U test (MWU) was used to compare different groups of genes. When comparing a subset of genes with the whole dataset we excluded the subset of genes from the dataset to avoid non-independence problems. Whereas necessary, computer simulations were conducted with randomly selected gene pairs to infer the probability of, by chance, observing our results. Each simulation involved 100,000 randomly permuted data sets. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS package version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL).

3. Results

3.1. Selective forces acting on putative aging-related genes

To investigate the overall selective forces acting on genes associated with aging in model systems, we first compared the Ka/Ks ratios of these genes and pathways with the Ka/Ks ratio of all human-chimpanzee orthologous gene pairs. Typically, purifying selection is predominant in human genes and the average Ka/Ks ratio for human-chimpanzee orthologs is 0.23 (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005). Groups of genes with significantly higher Ka/Ks ratios are putative cases of rapid evolution, and thus more likely to be associated with phenotypic changes, and vice-versa. Consequently, we tried to find evidence of positive selection or, at least, evidence of rapid or accelerated evolution in pathways and genes previously related to aging, based on the assumption that such genes and pathways are more likely to specify the greater longevity of humans relative to chimpanzees. As detailed in the Materials and Methods, we used the datasets and statistical methods developed by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), which have been previously shown to be capable of detecting meaningful biological findings.

3.1.1. Purifying selection is predominant in aging-associated genes

We obtained 242 protein-coding human genes associated with aging, primarily in model organisms, from build 12 of the GenAge database (de Magalhaes et al., 2005), of which 211 genes could be correctly analyzed. While it is unclear what proportion, if any, of these 211 genes control human aging, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this list is enriched for such genes, and it allowed us to estimate the evolutionary pressures affecting putative aging-related genes. We were surprised to find that the GenAge dataset as a whole–i.e., using concatenated Ka and Ks values (see Materials and Methods)–had a statistically significant lower Ka/Ks ratio (0.16) than the average (0.23) for human-chimpanzee orthologs (p < 0.001; MWU). This suggests that aging-associated genes tend to be under stronger functional constraints than what would be expected by chance. Likewise, functional categories present in GenAge appear to have undergone purifying selection since chimpanzees and humans diverged (Table 1), and we found little evidence of rapid evolution (but see below).

Table 1.

Selective forces operating on GenAge functional categories.

| GenAge category | n | Ka/Ks | p-value higha | p-value lowa | n in 4-way comparisonsb | Ka/Ks in hominids | Ka/Ks in murids | Homo AA diff.c | Pan AA diff.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apoptosis | 65 | 0.13 | 1 | 2.8E−09 | 43 | 0.082 | 0.10 | 14 | 15 |

| calcium | 6 | 0.18 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 2 | 0 |

| metabolism cell cycle control | 42 | 0.13 | 1 | 7.5E−07 | 26 | 0.057 | 0.11 | 10 | 9 |

| DNA condensation | 28 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 8 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 6 | 9 |

| DNA repair | 38 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.79 | 16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 9 | 11 |

| DNA | 15 | 0.24 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 7 | 0.079 | 0.14 | 4 | 2 |

| replication energy apparatus | 19 | 0.12 | 1 | 5.1E−05 | 12 | 0.13 | 0.082 | 7 | 6 |

| growth and development | 66 | 0.14 | 1 | 5.9E−10 | 44 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 37 | 17 |

| other | 47 | 0.17 | 1 | 2.9E−3 | 27 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 12 | 16 |

| redox and oxidative | 23 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 0.11 | 13 | 0.10 | 0.071 | 4 | 3 |

| regulation signaling | 52 | 0.13 | 1 | 1.9E−08 | 27 | 0.13 | 0.097 | 15 | 16 |

| stress response | 31 | 0.14 | 1 | 2.4E−4 | 14 | 0.10 | 0.087 | 4 | 5 |

| transcriptional regulation | 39 | 0.15 | 1 | 2.6E−3 | 22 | 0.062 | 0.084 | 3 | 7 |

This binomial probability is not used to directly reject the null hypothesis of a given GenAge category not undergoing rapid (probability high) or slow (probability low) evolution but provides a metric to identify categories potentially undergoing rapid or slow evolution. The test statistic threshold was set at 0.001 (see Materials and Methods).

Ka/Ks ratios in hominids are based on 4-way alignments and hence are expected to be different from Ka/Ks ratios based on only chimpanzee and human alignments, as described (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005).

Amino acid differences (AA diff.) represent amino acid changes estimated to have occurred specifically in the human (Homo) or chimpanzee (Pan) lineage.

It is possible for functionally constrained genes to be linked to lineage-specific phenotypic changes, which can be detected as lineage-specific accelerated evolution in, for instance, hominids when compared to murids (Dorus et al., 2004). For all 7,043 4-way gene alignments using chimpanzee, human, mouse, and rat orthologs computed by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), the average Ka/Ks ratio was 0.20 in hominids and 0.13 in murids. The average Ka/Ks ratio for genes in GenAge was 0.13 in hominids and 0.12 in murids, which does not suggest a general pattern of accelerated evolution of aging-associated genes in hominids. We also failed to detect accelerated evolution in GenAge’s functional categories (Table 1). Categories like calcium metabolism (n = 3) and DNA condensation (n = 8) had considerably higher Ka/Ks ratios in the hominid lineage but given the small number of genes in each of these categories we cannot exclude these are false positives.

We also tried to find evidence of human lineage-specific protein changes in GenAge. Overall, there were 66 human lineage-specific changes compared to 55 chimpanzee lineage-specific changes. Based on simulations, the probability of observing such a higher proportion of human lineage-specific changes over chimpanzee lineage-specific changes in a group of genes with this many amino acid changes is 32%, which does not suggest that the proportion of human lineage-specific protein changes in GenAge is higher than what would be expected by chance. In GenAge categories the strongest outlier was growth and development proteins in which more than twice as many changes occurred in the human lineage than in the chimpanzee lineage (Table 1). This could suggest lineage-specific selection since the probability of observing such a high proportion of human lineage-specific changes is 1.2%. Lastly, we employed the dataset of Clark et al. (2003) to determine whether human lineage-specific evolution occurred in GenAge or its categories (see Materials and Methods), but we found no evidence of accelerated evolution in the human lineage on any of these pathways (not shown).

Due to the close similarity between humans and chimpanzees, analyses of Ka/Ks ratios are more accurate when focusing on groups of genes. Nonetheless, results from individual genes in GenAge confirm our assessment that these putative aging-related genes tend to undergo purifying selection. Barring sequencing errors, and already excluding proteins with less than 95% of the human sequence aligned with the chimpanzee sequence, 56 proteins are perfectly conserved between humans and chimpanzees. By chance one would expect to find 43 such proteins–i.e., 29% of GenAge proteins aligned at least 95% with the chimpanzee orthologous sequence. Simulations indicate that the probability of observing such a high proportion of proteins perfectly conserved between humans and chimpanzees is 8.1%. Similarly, even though 4.4% of all genes have a Ka/Ki ratio above 1, only 2 of 211 genes in GenAge (APOC3 and PMCH) fulfilled this criterion. Based on simulations, the probability of observing such a low number of genes with a Ka/Ki ratio above 1 is 0.45%. In addition to BRCA1, which previous results including linkage disequilibrium analysis have suggested to be under positive selection (Huttley et al., 2000), and WRN (see below), other genes in GenAge with potential for positive selection include CDKN2A (Ka/Ki = 0.90) and EMD (Ka/Ki = 0.84 and Ka/Ks = 1.22).

We also studied the Ka/Ks ratios of GenAge using human-rhesus, human-mouse, and human-rat gene pairs. Although shorter-lived and evolutionary and biologically more distant organisms from humans (see Materials and Methods), these additional species provide a complementary model to human-chimpanzee gene pairs. Using human-rhesus gene pairs, the average Ka/Ks ratio for genes in GenAge was 0.16, significantly lower than the average (0.20) for all human-rhesus gene pairs (p < 0.001; MWU). The results from human-mouse and human-rat gene pairs did not confirm this idea, though, and the average Ka/Ks ratio of genes in GenAge was not lower than expected by chance (not shown). Therefore, it appears that the stronger-than-average functional constraints observed in GenAge genes in primates are not observed in the rodent lineage. We have no satisfactory explanation for this observation.

3.1.2. Selection in aging-associated GO categories

Of course, it can be argued that GenAge contains only a fraction, if any, of genes involved in human aging because most remain to be identified. To further investigate the selective forces acting on putative aging-related pathways and explore whether positive selection or rapid evolution may have acted on repair and defense mechanisms since humans and chimpanzees diverged, we examined Ka/Ks ratios, obtained from the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (2005), in GO categories that could potentially be related to aging (Table 2). Most pathways hypothesized to play a role in aging and somatic maintenance do not appear to have undergone rapid evolution, but there are a few exceptions. For example, there is some evidence that DNA repair (GO:0006281; Ka/Ks = 0.26; n = 121) and GO categories associated with DNA repair may have undergone rapid evolution after humans and chimpanzees diverged (Table 2). It was not clear, however, whether accelerated evolution in these GO categories occurred in the human rather than the chimpanzee lineage as lineage-specific protein changes occurred in both lineages (not shown but see discussion).

Table 2.

List of GO categories hypothesized to be related to aginga.

| GOb | Name | n | Ka/Ks | p-value highc | p-value lowc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Process GO categories related to DNA repair or processing | |||||

| 0006974 | response to DNA damage stimulus | 148 | 0.27 | 9.0E−07 | 1 |

| 0006281 | DNA repair | 121 | 0.26 | 1.1E−04 | 1 |

| 0042770 | DNA damage response, signal transduction | 15 | 0.38 | 3.2E−04 | 1 |

| 0006306 | DNA methylation | 11 | 0.087 | 1 | 1.8E−04 |

| 0006471 | protein amino acid ADP-ribosylation | 10 | 0.36 | 3.3E−03 | 1 |

| 0006298 | mismatch repair | 9 | 0.32 | 5.8E−03 | 1 |

| 0006282 | regulation of DNA repair | 5 | 1.1 | 4.6E−08 | 1 |

| 0030330 | DNA damage response, signal transduction by p53 class mediator | 3 | 1.4 | 1.3E−13 | 1 |

| Other Biological Process GO categories | |||||

| 0006950 | response to stress | 594 | 0.27 | 1.1E−17 | 1 |

| 0006118 | electron transport | 216 | 0.23 | 0.039 | 0.96 |

| 0006511 | ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism | 82 | 0.20 | 0.65 | 0.38 |

| 0006512 | ubiquitin cycle | 70 | 0.10 | 1 | 4.6E−11 |

| 0006979 | response to oxidative stress | 27 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.066 |

| 0007254 | JNK cascade | 23 | 0.12 | 1 | 2.6E−04 |

| 0006120 | mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone | 12 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.054 |

| 0001666 | response to hypoxia | 5 | 0.043 | 1 | 0.014 |

| Molecular Function GO categories | |||||

| 0005179 | hormone activity | 77 | 0.37 | 1.2E−08 | 1 |

| 0004840 | ubiquitin conjugating enzyme activity | 44 | 0.094 | 1 | 5.1E−06 |

| 0003773 | heat shock protein activity | 29 | 0.080 | 1 | 4.4E−08 |

| 0003684 | damaged DNA binding | 24 | 0.37 | 8.5E−05 | 1 |

| 0005184 | neuropeptide hormone activity | 15 | 0.39 | 4.8E−03 | 1 |

| 0004364 | glutathione transferase activity | 14 | 0.50 | 4.5E−04 | 1 |

| 0004407 | histone deacetylase activity | 8 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.082 |

Although the topic remains highly contentious, and the mechanisms of aging in primates are largely unknown, we selected GO categories encompassing mechanisms or functions typically associated with aging in model systems or hypothesized to be related to aging (see Materials and Methods).

Subcategories without evidence of positive selection or rapid evolution were omitted unless they were deemed as potentially relevant to aging.

This binomial probability is not used to directly reject the null hypothesis of a given GenAge category not undergoing rapid (probability high) or slow (probability low) evolution but provides a metric to identify categories potentially undergoing rapid or slow evolution. The test statistic threshold was set at 0.001 (see Materials and Methods).

We found no evidence that GO categories related to oxidative stress, such as response to oxidative stress (GO:0006979; Ka/Ks = 0.16; n = 27), have undergone rapid evolution (Table 2). The response to stress category (GO:0006950) could have undergone rapid evolution, but this is misleading because of its subcategories, namely, DNA repair and response to pest/pathogen/parasite (GO:0009613) that appear to have undergone rapid evolution. When the influence of these subcategories that could represent sources of bias was eliminated, response to stress was no longer considered under rapid selection (not shown). Similarly, there was evidence of rapid evolution (Ka/Ks = 0.50; n = 14) in the glutathione transferase activity (GO:0004364). Because glutathione transferases typically associated with aging, such as GSTA4 and GSTP1, were not found to be undergoing positive selection, and because some proteins from this GO category play a role in response to environmental stressors which typically tend to be associated with rapid evolution, these findings are not necessarily related to aging, even if intriguing. Similarly, hormone activity (GO:0005179) appeared to have undergone rapid evolution (Ka/Ks = 0.37 with n = 77), yet changes in hormones may be related to adaptations in processes other than aging. Indeed, genes from this GO category with Ka/Ks > 1 have been related to different functions, including processes typically associated with rapid evolution such as immune response, reproduction, and development, so it is not clear that rapid evolution in this GO category is associated with aging.

Overall, pathways and mechanisms previously related to aging found highly conserved between humans and chimpanzees include topoisomerases such as TOP3B, the JNK pathway including MAPK8 and MAPK9, IGF1, its receptor IGF1R, and IGFBP3, the Sir2 homolog SIRT1, the TOR homolog FRAP1, TP53, heat shock proteins (GO:0003773) such as HSPA1B, HSPA8, HSPA9B, HSP90AA1, and HSPD1, histone deacetylases (GO:0004407) like HDAC1 and HDAC3, and ubiquitin cycle (GO:0006512) such as SUMO, UBB, UBE2I, and UCHL1. The complete results are available online (http://genomics.senescence.info/evolution/chimp.html).

3.2. Genes linked to aging in different models are under different selection forces

As mentioned before, GenAge features genes associated with aging in different model systems, including genes derived from organisms ranging from yeast to rodents, cellular models, and progeroid syndromes–though some overlap is possible. Therefore, we investigated whether different evolutionary pressures acted on genes associated with aging in different model systems (Table 3). Interestingly, genes directly related to aging in non-human mammals (n = 21) and humans (n = 3) had the highest average Ka/Ks ratios (0.33 and 0.47, respectively) while genes associated with aging in non-mammalian models–typically invertebrates–had the lowest average Ka/Ks ratio (0.083). The higher average Ka/Ks ratio of genes linked to aging in non-human mammals–typically rodents–could be due to a few genes, such as WRN and BRCA1, because if these two genes were excluded the average Ka/Ks ratio of this category dropped to 0.19. Also in non-human mammals, genes associated with premature aging had a slightly higher Ka/Ks ratio (0.34; n = 16) than genes associated with life-extension (0.27; n = 6), though again this appears to be due to the presence of BRCA1 and WRN in the former. Genes associated with cellular models of aging also had a very low Ka/Ks ratio (0.11). Lastly, we found no significant indication of accelerated evolution in hominids when compared to murids, except in genes related to aging in mammals which may again be due to the influence of a few genes such as BRCA1 and WRN.

Table 3.

Selective forces operating on GenAge categories by selection process.

| GenAge categorya | n | Ka/Ks | p-value highb | p-value lowb | n in 4-way comparisonsc | Ka/Ks in hominids | Ka/Ks in murids | Homo AA diff.d | Pan AA diff.d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human | 3 | 0.472 | 0.017 | 0.99 | 2 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 4 | 8 |

| mammal | 21 | 0.331 | 0.0026 | 1 | 9 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 9 | 10 |

| model | 22 | 0.083 | 1 | 4.6E−07 | 14 | 0.069 | 0.10 | 2 | 3 |

| cell | 14 | 0.109 | 1 | 5.7E−4 | 6 | 0.068 | 0.19 | 2 | 1 |

| functional | 55 | 0.184 | 0.99 | 0.017 | 22 | 0.094 | 0.11 | 8 | 4 |

| upstream | 25 | 0.138 | 1 | 1.1E−3 | 15 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 9 | 2 |

| downstream | 46 | 0.097 | 1 | 7.6E−16 | 28 | 0.085 | 0.080 | 22 | 17 |

| putative | 56 | 0.159 | 1 | 2.3E−4 | 38 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 16 | 19 |

Genes linked to aging based on: human = evidence directly linking the gene product to aging in humans; mammal = evidence directly linking the gene product to aging in a non-human mammalian model organism; model = evidence directly linking the gene product to aging in a non-mammalian animal model organism; cell = evidence directly linking the gene product to aging in a cellular model system; functional = evidence linking the gene product to a pathway or mechanism linked to aging; upstream = evidence directly linking the gene product to the regulation or control of genes previously linked to aging; downstream = evidence showing the gene product to act downstream of a pathway, mechanism, or other gene product linked with aging; putative = indirect or inconclusive evidence linking the gene product to aging.

This binomial probability is not used to directly reject the null hypothesis of a given GenAge category not undergoing rapid (probability high) or slow (probability low) evolution but provides a metric to identify categories potentially undergoing rapid or slow evolution. The test statistic threshold was set at 0.001 (see Materials and Methods).

Ka/Ks ratios in hominids are based on 4-way alignments and hence are expected to be different from Ka/Ks ratios based on only chimpanzee and human alignments, as described (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005).

Amino acid differences (AA diff.) represent amino acid changes estimated to have occurred specifically in the human (Homo) or chimpanzee (Pan) lineage.

We also looked at the Ka/Ks ratios of genes (n = 14) associated with human longevity or survival in the elderly that might thus be associated with healthy aging. The average Ka/Ks ratio was 0.16 with no significant evidence of a higher or lower than average Ka/Ks ratio. None of these genes had a Ka/Ks ratio > 1. The strongest outliers were SIRT3 with a Ka/Ks = 0.85 (but Ka/Ki = 0.42) and APOC3 with a Ka/Ki = 1.19 (but Ka/Ks = 0.35). The complete results are available online (http://genomics.senescence.info/evolution/chimp.html).

Analyses of the GenAge dataset according to selection clusters using human-rhesus, human-mouse, and human-rat gene pairs were largely in accordance with the abovementioned results obtained using human-chimpanzee gene pairs. For example, genes associated with aging in lower organisms and cellular models always had a lower Ka/Ks ratio than genes associated with aging in mammals.

3.3. Evolution of genes associated with segmental progeroid syndromes

As mentioned above, we found limited evidence of positive selection or rapid or accelerated evolution in GenAge genes. Apart from BRCA1, it is unclear whether any of the genes in GenAge have undergone positive selection since humans and chimpanzees diverged. Nonetheless, we wanted to evaluate whether genes associated with premature aging in humans could also be related to the evolution of aging in the human lineage.

The three genes in which mutations cause what most dramatically resembles premature aging in humans are WRN, ERCC8, and LMNA, of which WRN, the gene responsible for Werner’s syndrome, is the most striking case. Other genes that might also be considered segmental progeroid syndromes include BSCL2, ERCC6, NBN, and AGPAT2 (Martin, 1978 & 2005; de Magalhaes, 2005a). We failed to find significant evidence of positive selection or rapid evolution in either hominins or hominids in any of these genes, except for WRN.

In the case of WRN, both the Ka/Ks (0.91) and Ka/Ki (0.59) ratios indicate the gene could have undergone rapid evolution since humans and chimpanzees diverged. WRN also had a higher Ka/Ks ratio (0.75) in hominids than in murids (0.31), which could suggest accelerated evolution in the former, and higher-than-average Ka/Ks ratios in the human-rhesus gene pair (0.53), human-mouse gene pair (0.32), and human-rat gene pair (0.29). Although these results could be false positives (see discussion), they suggest possible adaptive changes in the WRN gene in the hominid lineage. Previously, Clark et al. (2003) reported that WRN could have undergone accelerated evolution in the human lineage (p = 0.028). Using a human-chimpanzee-orangutan protein alignment, however, we found 11 chimpanzee-specific protein changes but only 4 human-specific protein changes in WRN plus 2 changes that could not be attributed to either lineage. Because the chimpanzee genome sequence is still considered a draft, however, errors in it could artificially increase the number of chimpanzee lineage-specific protein changes.

Our results and Ka/Ks ratios have been incorporated into the GenAge database (http://genomics.senescence.info/genes/human.html) and could be useful for researchers working on aging to study the evolution of aging-associated genes across primates. They are further available online (http://genomics.senescence.info/evolution/chimp.html).

4. Discussion

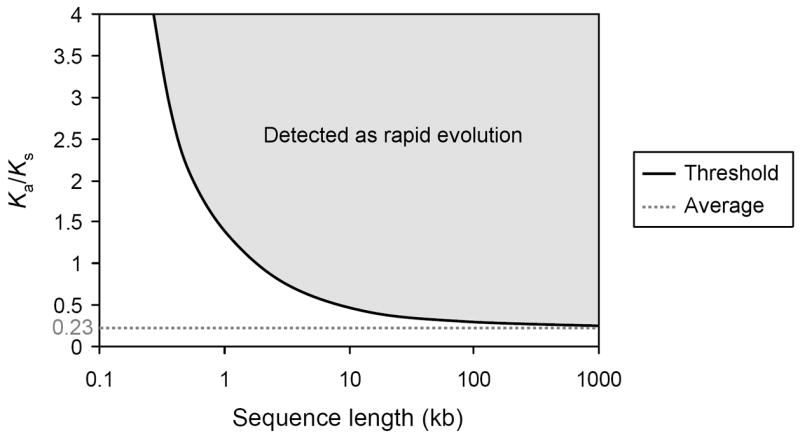

Multiple primate genomes will be necessary to understand the genetic changes that contributed to the distinguishing features of the human aging process and thus our work should be considered preliminary or explorative. Our approach for identifying genes responsible for the interspecies differences in longevity is novel and promising but its limit of detection is still confined to relatively strong signals (Figure 1). Moreover, such large-scale, genome-wide analyses are so far only feasible in protein-coding regions, yet it is likely that differences in gene regulation also specify species differences in aging and there could be important changes in regulatory regions, RNA genes, or even some unknown gene product that are not detectable by our method. Despite these limitations, our work offers new insights regarding the evolutionary forces acting on genes associated with aging in model systems.

Figure 1.

Approximate limit of detection of rapid evolution using our test statistic as a function of sequence length and Ka/Ks ratio. The straight black line represents the Ka/Ks ratio threshold above which a given protein-coding sequence will be detected as undergoing rapid evolution. Sequence length, which may be a single gene or a concatenated sequence of a large group of genes (the average human-chimpanzee gene pair, only including the protein-coding sequence, is approximately 1.4 kb), is plotted on a logarithmic scale. The dotted gray line is the average Ka/Ks ratio for all human-chimpanzee gene pairs (0.23). Ka/Ks ratios assume a constant Ks and a constant proportion of synonymous and nonsynonymous sites in relation to sequence length, both of which were estimated from the average of all human-chimpanzee gene pairs.

Although we found evidence of selection in a few genes and pathways previously associated with aging, we urge caution in interpreting these results. For instance, genes in GO categories may be involved in functions unrelated to aging and thus any evidence of rapid evolution may reflect selection on another trait (but see below). One potentially interesting finding was the putative rapid evolution of DNA repair proteins. Other works have reported evidence of positive selection in DNA metabolism genes, including ERCC8, in recent human evolution (Wang et al., 2006). These results could be associated with hypotheses of aging predicting that DNA repair/metabolism genes play a role in species differences in aging (reviewed in de Magalhaes, 2005a; Martin, 2005). On the other hand, rapid evolution of DNA repair genes is not unique of long-lived humans or hominids and, in fact, some results suggest accelerated evolution in DNA repair genes in murids when compared to hominids (Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2005). More detailed studies encompassing several mammalian genomes are warranted to examine whether changes to DNA repair/metabolism genes are involved in the evolution of aging.

Overall, our results using the GenAge dataset show that, at least in the primate lineage, genes associated with aging in model systems tend to be under purifying selection and stronger-than-average functional constraints. Even though it is possible for genes under strong functional constraints to play a role in the evolution of lineage-specific traits, we found little evidence of accelerated evolution in putative aging-related genes in the hominid or human lineages. Genes with such patterns of selection tend to have key biological functions conserved among mammals and these evolutionary forces typically preserve existing phenotypes. Because our work is the first to explore the evolutionary pressures acting on aging-associated genes and pathways, however, different explanations can be conceptualized, and our results do not disprove any potential involvement these genes may have on human aging. Certainly, phenotypically-important changes in one or a few genes–maybe even changes in regulatory regions–are likely to be undetected by our analyses. For instance, although we found no evidence of rapid evolution in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (GO:0006118 and GO:0006120), rapid evolution in a few of these proteins has been reported in anthropoid primates (Grossman et al., 2004), and it has been hypothesized that this represents a life-extending adaptation (de Magalhaes, 2005b). Though speculative, an alternative hypothesis is that genes involved in aging require extreme precision, because they are likely to have other functions, and subtle, so far impossible to detect changes led to the life-extension of humans.

Apart from the GO categories results, which can be subject to different interpretations, we found little evidence of a widespread optimization of multiple maintenance and repair mechanisms, even though this may be due to limitations in our analyses. The differences we found in selection pressures acting on genes associated with aging in different models systems, such as the observation that genes associated with aging in non-mammalian model organisms are under stronger functional constraints than genes associated with aging in mammals, are novel. These results might reflect, in human-chimpanzee gene pairs, a higher degree of conservation throughout evolution of genes whose homologs are involved in aging in non-mammalian model organisms. In fact, the proportion of human homologs of aging-related genes in model organisms has been reported to be higher than expected by chance (Budovsky et al., 2007). This high conservation of aging-related genes might be related to their reported higher-than-average interactions (Promislow, 2004; Budovsky et al., 2007). Our results, albeit only explorative, do not appear to support the hypothesis that most genes and mechanisms that have been the focus of research in model organisms are likely to regulate species differences in aging, at least in primates. Even if the mechanisms of aging identified so far in model systems do not explain differences in aging between hominids, it is plausible that these mechanisms are conserved between organisms, for instance, as part of a conserved mechanism linking reproduction and food availability to aging (Partridge and Gems, 2002). In other words, perhaps the biological functions of these genes are part of conserved pathways related to pleiotropic effects on aging that impact on intra-species differences in aging but do not regulate inter-species differences in aging.

As mentioned in the introduction, our rationale in this work is based on the concept, supported by modern evolutionary theory (e.g., Charnov, 1993; Kirkwood and Austad, 2000), that the extended human lifespan and delayed onset of aging are a product of direct selective pressures. With the little that we know about the genetics of aging in primates, however, we cannot exclude alternatives. Maybe the delayed onset of aging in humans is a by-product of selection acting on other traits, such as development, growth, or reproduction. For instance, one hypothesis is that, after humans and chimpanzees diverged, natural selection may have acted primarily on developmental pathways to extend development, growth, and lifespan (de Magalhaes and Church, 2005). In fact, one mechanism shown to act on development, growth, and aging is the endocrine system (reviewed in McKinney and McNamara, 1991; Partridge and Gems, 2002; de Magalhaes, 2005a; de Magalhaes and Church, 2005). Hormonal adaptations, even those related to development and reproduction, may thus have some impact on aging. The higher proportion of human-specific protein changes in GenAge proteins associated with growth and development and the putative rapid evolution in hormone activity GO categories support this view. If the delayed onset of human aging is a by-product of the delayed human development then genes related to aging in model systems may be expected to be under purifying selection.

Lastly, our results indicate a putative rapid evolution of WRN, a gene in which mutations result in a phenotype that resembles accelerated aging in human patients. Our results do not prove that WRN has undergone adaptive changes, and admittedly may be a result of chance, though because WRN encodes a relatively large protein with 1432 amino acids Ka/Ks ratios are less likely to be exaggerated than those of genes coding smaller proteins. Moreover, it is an intriguing coincidence that the gene associated with the most impressive human progeroid syndrome is one of the genes in GenAge with the highest Ka/Ks ratio. It is tempting to speculate that changes to WRN are also involved in the evolution of aging in primates and hominids. Since humans and chimpanzees diverged, most protein changes to WRN were chimpanzee lineage-specific, which makes it unlikely that protein changes to WRN contributed to the evolution of human longevity. This could suggest a pattern of selection on WRN similar to that observed in the MCPH1 gene where selection is most pronounced in earlier portions of the lineage (Vallender and Lahn, 2004). Analyses of changes to the WRN protein during primate and mammalian evolution merit further attention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank David Reich and Joana Costa for comments on previous drafts and Steve Elledge and members of the Church lab for valuable discussions. J. P. de Magalhães is supported by NIH-NHGRI CEGS grant to G. M. Church.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyadevara S, Engle MR, Singh SP, Dandapat A, Lichti CF, Benes H, Shmookler Reis RJ, Liebau E, Zimniak P. Lifespan and stress resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans are increased by expression of glutathione transferases capable of metabolizing the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. Aging Cell. 2005;4:257–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E, et al. Ensembl 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D556–561. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Borg HM, Borg KE, Meliska CJ, Bartke A. Dwarf mice and the ageing process. Nature. 1996;384:33. doi: 10.1038/384033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budovsky A, Abramovich A, Cohen R, Chalifa-Caspi V, Fraifeld V. Longevity network: Construction and implications. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkle A, Beneke S, Muiras ML. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1599–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas E, Davies KJ. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnov EL. Life History Invariants: Some Explorations of Symmetry in Evolutionary Ecology. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG, Glanowski S, Nielsen R, Thomas PD, Kejariwal A, Todd MA, Tanenbaum DM, Civello D, Lu F, Murphy B, Ferriera S, Wang G, Zheng X, White TJ, Sninsky JJ, Adams MD, Cargill M. Inferring nonneutral evolution from human-chimp-mouse orthologous gene trios. Science. 2003;302:1960–1963. doi: 10.1126/science.1088821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP. Is mammalian aging genetically controlled? Biogerontology. 2003;4:119–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1023356005749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP. Open-minded scepticism: inferring the causal mechanisms of human ageing from genetic perturbations. Ageing Res Rev. 2005a;4:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP. Human disease-associated mitochondrial mutations fixed in nonhuman primates. J Mol Evol. 2005b;61:491–497. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP, Church GM. Genomes optimize reproduction: aging as a consequence of the developmental program. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:252–259. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP, Costa J, Toussaint O. HAGR: the Human Ageing Genomic Resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database Issue):D537–543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhaes JP. Species selection in comparative studies of aging and antiaging research. In: Conn PM, editor. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Elsevier Academic Press; Burlington, MA: 2006. pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dorus S, Vallender EJ, Evans PD, Anderson JR, Gilbert SL, Mahowald M, Wyckoff GJ, Malcom CM, Lahn BT. Accelerated evolution of nervous system genes in the origin of Homo sapiens. Cell. 2004;119:1027–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin JM, Hof PR, Ely JJ, Perl DP. One gerontology: advancing understanding of aging through studies of great apes and other primates. In: Erwin JM, Hof PR, editors. Aging in Nonhuman Primates. Karger; Basel: 2002. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE. Longevity, Senescence, and the Genome. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago and London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE, Stanford CB. Meat-adaptive genes and the evolution of slower aging in humans. Q Rev Biol. 2004;79:3–50. doi: 10.1086/381662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flurkey K, Papaconstantinou J, Miller RA, Harrison DE. Lifespan extension and delayed immune and collagen aging in mutant mice with defects in growth hormone production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6736–6741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111158898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraga CG, Shigenaga MK, Park JW, Degan P, Ames BN. Oxidative damage to DNA during aging: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in rat organ DNA and urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4533–4537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DA, Tsirigotis M, Woulfe J. Ubiquitin, proteasomes, and the aging brain. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003:RE6. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2003.34.re6. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman LI, Wildman DE, Schmidt TR, Goodman M. Accelerated evolution of the electron transport chain in anthropoid primates. Trends Genet. 2004;20:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty P, Campisi J, Hoeijmakers J, van Steeg H, Vijg J. Aging and genome maintenance: lessons from the mouse? Science. 2003;299:1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1079161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Boesch C, Goodall J, Pusey A, Williams J, Wrangham R. Mortality rates among wild chimpanzees. J Hum Evol. 2001;40:437–450. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2001.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttley GA, Easteal S, Southey MC, Tesoriero A, Giles GG, McCredie MR, Hopper JL, Venter DJ. Adaptive evolution of the tumour suppressor BRCA1 in humans and chimpanzees. Australian Breast Cancer Family Study. Nat Genet. 2000;25:410–413. doi: 10.1038/78092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katschinski DM. Is there a molecular connection between hypoxia and aging? Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:482–484. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005;120:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TB, Austad SN. Why do we age? Nature. 2000;408:233–238. doi: 10.1038/35041682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YJ, Seroude L, Benzer S. Extended life-span and stress resistance in the Drosophila mutant methuselah. Science. 1998;282:943–946. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard DB, Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Franco S, Gostissa M, Alt FW. DNA repair, genome stability, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:497–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM. Genetic syndromes in man with potential relevance to the pathobiology of aging. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1978;14:5–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM. Genetic modulation of senescent phenotypes in Homo sapiens. Cell. 2005;120:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GM, Austad SN, Johnson TE. Genetic analysis of ageing: role of oxidative damage and environmental stresses. Nat Genet. 1996;13:25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney ML, McNamara KJ. Heterochrony: The Evolution of Ontogeny. Plenum; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature. 1999;402:309–313. doi: 10.1038/46311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimpanzee Sequencing, Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA. Kleemeier award lecture: are there genes for aging? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B297–307. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.b297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morbeck ME, Galloway A, Sumner DR. Getting old at Gombe: skeletal aging in wild-ranging chimpanzees. In: Erwin JM, Hof PR, editors. Aging in Nonhuman Primates. Karger; Basel: 2002. pp. 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Moskovitz J, Bar-Noy S, Williams WM, Requena J, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (MsrA) is a regulator of antioxidant defense and lifespan in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12920–12925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231472998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Bustamante C, Clark AG, Glanowski S, Sackton TB, Hubisz MJ, Fledel-Alon A, Tanenbaum DM, Civello D, White TJ, J JS, Adams MD, Cargill M. A scan for positively selected genes in the genomes of humans and chimpanzees. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L, Gems D. Mechanisms of ageing: public or private? Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:165–175. doi: 10.1038/nrg753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L, Gems D. Beyond the evolutionary theory of ageing, from functional genomics to evo-gero. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promislow DE. Protein networks, pleiotropy and the evolution of senescence. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271:1225–1234. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson B. Impact of aging on DNA methylation. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:245–261. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogina B, Helfand SL, Frankel S. Longevity regulation by Drosophila Rpd3 deacetylase and caloric restriction. Science. 2002;298:1745. doi: 10.1126/science.1078986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MR. Evolutionary Biology of Aging. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Bartke A, Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1081447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallender EJ, Lahn BT. Positive selection on the human genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(Spec No 2):R245–254. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A, Altheide TK. Comparing the human and chimpanzee genomes: searching for needles in a haystack. Genome Res. 2005;15:1746–1758. doi: 10.1101/gr.3737405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Kodama G, Baldi P, Moyzis RK. Global landscape of recent inferred Darwinian selection for Homo sapiens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:135–140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509691102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MC, Bohmann D, Jasper H. JNK signaling confers tolerance to oxidative stress and extends lifespan in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2003;5:811–816. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, et al. DNA sequence and comparative analysis of chimpanzee chromosome 22. Nature. 2004;429:382–388. doi: 10.1038/nature02564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama K, Fukumoto K, Murakami T, Harada S, Hosono R, Wadhwa R, Mitsui Y, Ohkuma S. Extended longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans by knocking in extra copies of hsp70F, a homolog of mot-2 (mortalin)/mthsp70/Grp75. FEBS Lett. 2002;516:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02470-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.