Abstract

Top down proteomics in a TOF-TOF instrument was further explored by examining the fragmentation of multiply charged precursors ions generated by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization. Evaluation of sample preparation conditions allowed selection of solvent/matrix conditions and sample deposition methods to produce sufficiently abundant doubly and triply charged precursor ions for subsequent CID experiments. As previously reported, preferential cleavage was observed at sites C-terminal to acidic residues and N-terminal to proline residues for all ions examined. An increase in non-preferential fragmentation as well as additional low mass product ions was observed in the spectra from multiply charged precursor ions providing increased sequence coverage. This enhanced fragmentation from multiply charged precursor ions became increasingly important with increasing protein molecular weight and facilitates protein identification using database searching algorithms. The useable mass range for MALDI TOF-TOF analysis of intact proteins has been expanded to 18.2 kDa using this approach.

Introduction

Fragmentation of intact protein gas phase ions, termed top-down proteomics, is becoming more frequently utilized primarily in ion trapping instruments. As was first reported by Loo et al. [1], multiply-charged intact protein ions are formed via electrospray ionization (ESI) and can be collisionally activated to produce sequence specific fragment ions. Typically, the fragmentation of highly multiply charged intact proteins results in a product ion spectrum displaying a multitude of product ions possessing a range of charge states making spectral interpretation challenging. The high resolving power and mass accuracy of Fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometry has made this instrument platform the method of choice for the interpretation of the complicated product ion spectra produced by fragmentation of multiply charged protein ions. Indeed, automated interpretation algorithms have been constructed based on this approach [2, 3]. Using FTMS proteins over 200 kDa have been successfully fragmented and sequence specific product ion assignments have been made [4]. Lower mass resolving quadrupole ion trapping instruments have also been successfully utilized for top down proteomics experiments. In order to meet the challenge of spectral interpretation ion/ion reactions have been employed to reduce the product ion charge by subjecting the product ion population to proton transfer reactions, thereby resulting in the formation of predominantly singly charged product ions and a more readily interpretable product ion spectrum [5]. This strategy removes the product ion charge-state ambiguities arising from dissociation of large multiply charged protein ions and has been successfully demonstrated on ions as large as elastase (25.9 kDa) although it is limited by the m/z range of the instrument [6]. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization tandem time-of-flight (MALDI TOF-TOF) mass spectrometry has also been used to produce product ion spectra of intact proteins ions [7, 8]. One advantage of this approach is the selection of dominant singly charged precursor ions formed by MALDI and the resulting simplified product ion spectrum. However, the demonstrated mass range for such an experiment is only 12 kDa.

The most common ion activation method used in both FT-ICR and quadrupole ion trapping instruments for top down proteomics is collision activated dissociation (CAD) in some form. Specialty CAD approaches such as sustained off-resonance irradiation (SORI) CAD, very low energy (VLE) and multiple-excitation collisional activation (MECA) have been explored in efforts to generate more sequence rich product ion spectra from FT-ICR instruments. Electron capture dissociation (ECD) has proven to be a powerful method for generating rich product ion spectra [9-20]. More recently, electron transfer dissociation (ETD) has been demonstrated to provide extensive sequence coverage for proteins as large as 66 kDa in a quadrupole ion trapping instrument [21].

In addition to the activation method, another factor that influences fragmentation of intact proteins is the precursor ion charge state. The fragmentation of a variety of proteins with different charge states was extensively investigated in McLuckey’s laboratory, including human hemoglobin α- and β-chain ions [22, 23], insulin [24], apomyoglobin [25], ubiquitin [24], ferro-, ferri- and apo-cytochrome C ion [26], ribonuclease A and B [27] and native and reduced elastase [6]. To summarize this body of work, more primary structure information is obtained when intermediate charge states are subjected to CID and post ion/ion reaction.

As described above, recent work indicates that MALDI TOF-TOF instrumentation is able to produce fragments from intact protein molecular ions [7, 8] albeit with limited mass range. Predominantly singly charged ions are formed in the MALDI process; therefore, any potential advantage that intermediate or high charge states provide in fragmentation efficiency is lost. However, by varying the experimental conditions, such as matrix choice, matrix solution, matrix/analyte ratios, crystallization conditions, sample deposition method, etc., multiply charged MALDI ions can be generated. For example, Frankevich et al. [28] reported that matrices with higher ionization energy, e.g. α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA), show a much higher yield of multiply charged protein ions. The influence of matrix solution conditions on the formation of peptide and protein ions was investigated by Cohen and Chait, which revealed that formation of high molecular weight analyte ions are favored in a matrix solution composition of 2:3:1 (v:v:v) formic acid:water:actonitrile (isopropanol or methanol), especially with slow matrix crystal growth method [29]. By using a new sample preparation method, which involved the creation of a thin film of protein-doped (CHCA) matrix formed in the presence of glycerol on the top of a previously deposited pad of CHCA matrix, a Zhou and Lee observed highly charged protein ions [30]. When the matrix/analyte is co-crystallized on polyether ether ketone, an “electron free” surface, an unusually large fraction of multiply charged ions is produced, compared to the normally used stainless steel surface [28]. The charge state, as well as the signal intensity, is also related to the way the sample is spotted as evidenced by electrospray deposition of analyte resulting in multiply charged ions being produced at threshold laser irradiance [31]. There is one report of the use of multiply charged precursor ions in MALDI TOF-TOF experiments for protein identification in bacterial proteomes [32] that demonstrates the advantage of using multiple precursors to enhance database searching results.

In this report, we evaluate sample preparation conditions for generating multiply charged intact protein ions in a MALDI source, compare MALDI TOF-TOF product ion spectra generated from singly and multiply charged precursor ions, and expand the current protein mass limit for MALDI TOF-TOF analysis. It is anticipated that the additional product ion information generated through the use of multiply charged precursor ions will assist in automated protein identification in top-down proteomics experiments.

Experiments

Materials

All proteins were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) and include bovine ubiquitin, E. coli thioredoxin, horse heart myoglobin, and bovine milk β-lactoglobulin. The matrix, re-crystallized CHCA, was purchased from Bruker Daltonics (Billerica, MA). Analytical grade acetonitrile and isopropanol were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA).

Sample Preparation

Stock protein solutions were prepared in deionized water at a concentration of 50 pmol/μl. Saturated CHCA solutions in 1:2 water:acetonitrile (v:v) or 1:3:2 formic acid:water:acetonitrile (FWA) (v:v:v) were freshly made as the freshness of CHCA solution is very important.

The ultra-thin layer method of sample preparation employed here was adapted from previous work [33]. Both the conditions of the matrix layer preparation as well as the composition of the matrix/sample solution were examined for maximum yield of multiply charged protein ions. Firstly, saturated CHCA solution in 1:2 water:acetonitrile was diluted 4-fold with acetonitrile. This matrix solution was subsequently further diluted in either 1:4 or 1:9 (v:v) in 50% or 25% water/isopropanol (WI). A small aliquot (ca. 0.3 μl) of the diluted CHCA solution was spotted on a 192-well stainless sample plate and air dried to achieve a uniform ultra-thin matrix layer. An aliquot (0.5 μl) of protein:saturated CHCA solution mixture 1:4 (v:v) was then applied on top of the dried ultra-thin matrix layer.

MALDI TOF-TOF Mass Spectrometry

All mass spectra were acquired on an Applied Biosystems 4700 Proteomics Analyzer equipped with TOF/TOF ion optics and a diode pumped Nd:YAG laser with 200 Hz repetition rate. The operating principle of this mass spectrometer was detailed previously [7]. The potential difference between acceleration voltage and floating collision cell defines the collision energy, which was 1 keV in all experiments. Re-optimized instrument settings were employed to achieve optimal sensitivity [8].

All the MS/MS spectra resulted from accumulation of 10000 laser shots. Air was used as the collision gas such that nominally single collision conditions were achieved. Since pure protein standards were used, a wide mass window was utilized to obtain maximum precursor ion transmission. Generally, the width of mass window is set to 50 Da if the mass of precursor ion is less than 5000 Da, 100 Da for precursor mass < 9000 Da, 200 Da for less than 12000 Da and 300 Da for precursors >12,000 Da. The maximum recorded product ion m/z ratio was limited by the instrument control software to the selected precursor ion m/z ratio. MS/MS data were acquired using the instrument default calibration which was updated daily with protein standards.

Results and Discussion

Effect of Sample Preparation

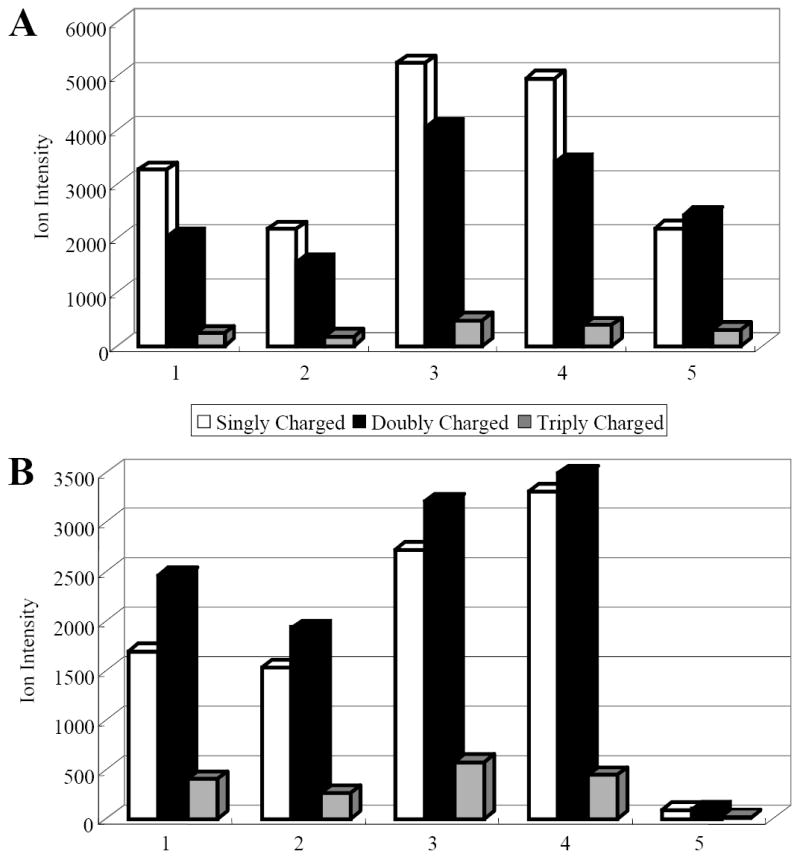

Previous studies revealed that sample preparation is critical for MALDI analysis [34]. The commonly used methods include dried-droplet, thin-layer and sandwich preparation. Among them, the thin-layer preparation features higher sensitivity in the detection of peptide and proteins, and has demonstrated tolerance to salts [35]. The ultra-thin layer method [33], developed from thin-layer method, facilitates the detection of membrane proteins in the present of detergent when 1:3:2 FWI is employed as the matrix solvent. The matrix solution composition itself also plays an important role in the incorporation of analyte with matrix. Intense analyte signals were observed when 1:3:2 formic acid:water:organic solvent (isopropanol, acetonitrile, methanol) was selected as the matrix solvent [29]. In this report, 1:3:2 FWA and 3:1:2 FWA were used as spotting matrix solutions in the ultra-thin layer method as the sample preparation method to examine the effect of sample preparation on the yield of multiply charged myoglobin ions. In Cadene’s method, the ultra-thin layer is constructed by applying diluted matrix solution to a whole sample plate (50X50 mm) and leveling the ultra-thin matrix layer with a Kimwipe [33]. Here, the ultra-thin matrix layer preparation was slightly modified by applying a further diluted matrix solution to the sample plate. Five-fold and ten-fold dilution of the matrix solution in 1:1 and 1:4 WI were examined. Figure 1 shows the myoglobin ion yield produced from different ultra-thin layer preparations and spotting matrix solutions. The ion intensity represents the mean from 3 replicates, each with 10000 laser shots. As presented in Figure 1A and 1B, the myoglobin ion yield (singly, doubly and triply-charged) was enhanced with ultra-thin layer sample preparation compared to the dried droplet method, except for the 1:9 dilution in 50% WI /1:3:2 FWA preparation. Dilution of ultra-thin matrix solution in 25% WI yielded more protein ions, regardless the spotting matrix solution employed. In addition, a higher concentration of formic acid in the spotting matrix solution results in more multiply charged protein ions as shown in Figure 1B where the yield of doubly charged myoglobin ions exceeds that of singly charged ions. However, the overall signal was lower with high formic acid concentrations and these conditions may cause adventitious formylation and protein degradation. These results suggest that a combination of dilution in 25% WI of matrix solution and the use of 1:3:2 FWA spotting matrix solution provides enhanced yields of multiply charged protein ions.

Figure 1.

Yield of singly, doubly and triply charged myoglobin ions generated from different ultra-thin layer preparations. A. Spotting matrix solution 1:3:2 FWA, B. Spotting matrix solution 3:1:2 FWA. To prepare ultra-thin matrix layer saturated CHCA solution in 1:2 water:isopropanol was first diluted 1:4 in acetonitrile followed by further dilution with different solvent compositions: 1) 1:4 dilution in 50% WI, 2) 1:9 dilution in 50% WI, 3) 1:4 dilution in 25% WI , 4) 1:9 dilution in 25% WI and 5) dried droplet method.

Ubiquitin

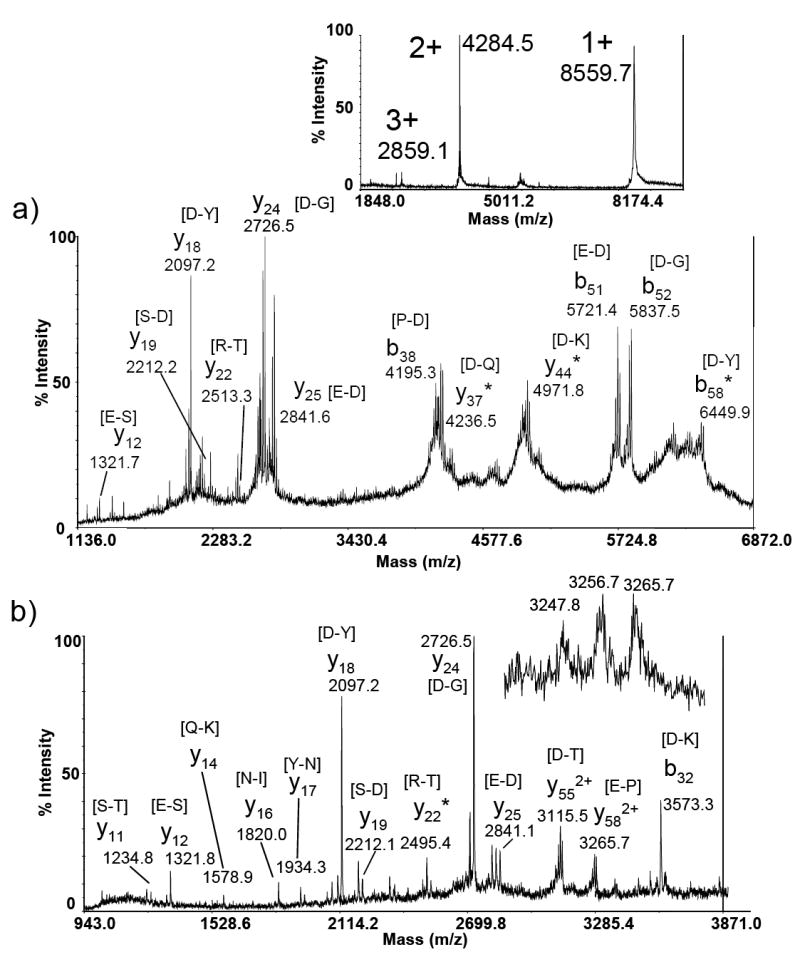

Ubiqitin is an 8.6 kDa protein that has been extensively used as a model protein for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) studies. MS/MS spectra of multiply charged ubiquitin ions have been collected by a variety of activation methods, including SORI-CAD [36], laser-induced dissociation [37, 38], BIRD [39], ECD [20], post ion-ion reaction [40], and ETD [21]. Fragmentation of singly charged ubiquitin was also examined in a MALDI TOF-TOF instrument [7, 8]. In a recent study, doubly charged ubiquitin ions were fragmented by laser induced dissociation (LID) in a MALDI TOF-TOF instrument [32]. In the present study, both singly and doubly charged precursor ions, shown in the insert in Figure 2A, were selected for CID in a MALDI TOF-TOF instrument. As stated in Experimental section, the maximum m/z ratio recorded by the 4700 software is limited by precursor ion m/z. Therefore, for the doubly charged ubiquitin ion, the maximum m/z recorded was 4283.86.

Figure 2.

MALDI TOF-TOF product ion spectrum of a) singly charged ubiquitin and b) doubly charged ubiquitin. Insert shows water losses of doubly charged product ions. Insert shows intensities of precursor ions in MALDI mass spectrum. Asterisks indicate loss of water or ammonia from product ion. The amino acids in brackets as peak labels indicate the peptide bond broken to produce the assigned product ion.

As observed previously, the high mass region (> 4000 Da) of MS/MS of singly charged ubiquitin ions features preferential cleavage to form b- and y-ions at sites C-terminal to acidic amino acids as well as efficient loss of water and/or ammonia from these ions. Thus many of the observed product ions are clusters of signals separated by 17/18 Da. In addition to the product ions resulting from preferential cleavage (y18 and y24), some non-preferential cleavage products are also observed in the low mass region, for example y19 [S-D] and y22 [R-T] ions. An increased number of non-preferential cleavage products are produced when doubly charged ubiquitin ions undergo CID, as shown in Fig. 2B. These include the y11, y14, y16, and y17 ions that are not present in the spectrum of singly charged ubiquitin. These signals provide additional information for protein identification. The b32 ion, centered at m/z 3573.3, is only present in the MS/MS spectrum of the doubly charged ubiquitin ion. Interestingly, the complementary fragment of b32 ion, the y44 ion, is observed in the MS/MS spectra of singly charged ubiquitin ions.

The mass resolution of the TOF-TOF instrument limits isotopic resolution of multiply charged product ions; however, there is evidence that doubly charged product ions, due to the generation of a doubly charged product ion and a neutral fragment, are present. As shown in the insert in Fig. 2B, a group of unresolved signals with m/z spacings of 7 – 8Th indicate the possibility of the signal at m/z 3265.7 being doubly charged (singly charged ions should be mass resolved). The measured m/z ratios do not match any predicted singly charged b- or y-ions of ubiquitin. If they are considered as doubly charged ions, this cluster of signals can be assigned as the doubly charged y58 ion (preferential cleavage after Asp) and its associated water and ammonia losses. The results in Figure 2 are similar to those reported for LID of singly and doubly charged ubiquitin [32].

Thioredoxin

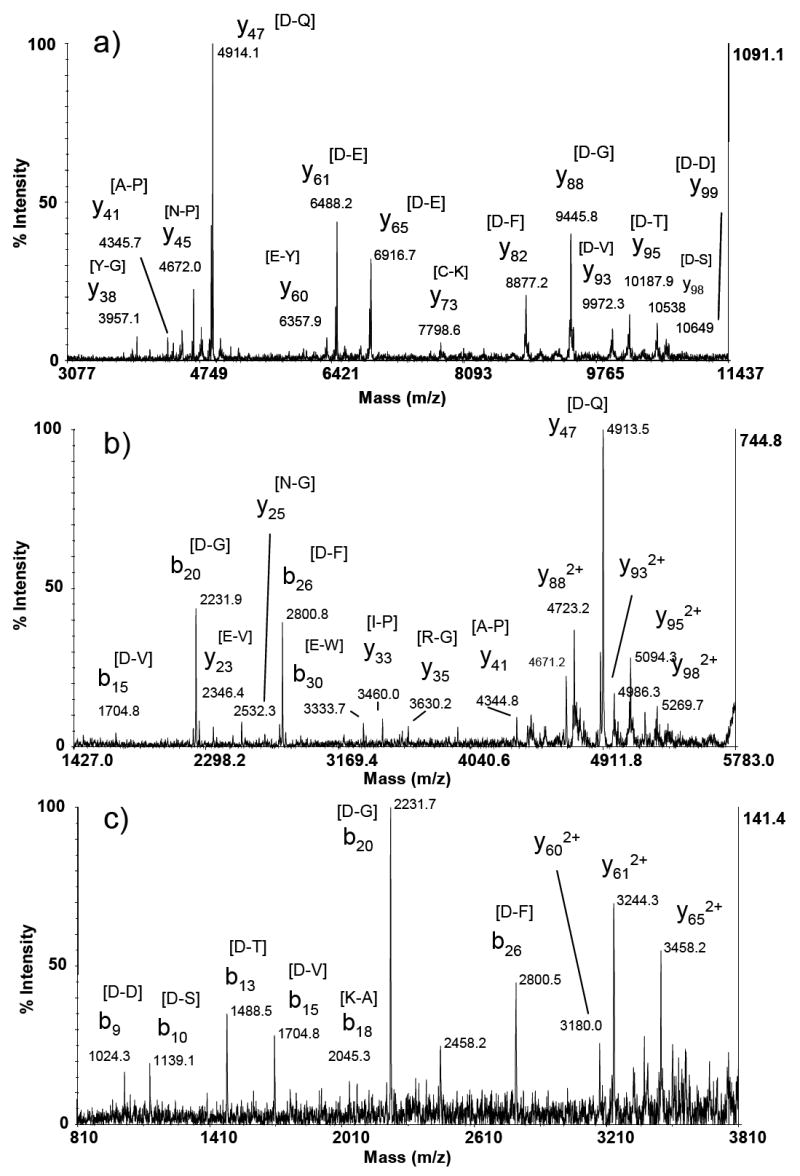

Thioredoxin has been widely studied as a model protein for top down proteomics since preferential cleavage was first shown in a MALDI TOF experiment by Yu et al. [41]. TOF-TOF tandem mass spectra of singly charged thioredoxin have been previously reported [8] and are included in Figure 3 for comparison to spectra of multiply charged thioredoxin ions. As shown previously, efficient generation of preferential cleavage products occurs in the TOF-TOF instrument (Figure 3A) leading to abundant product ions signals from the 12 kDa protein. When doubly charged thioredoxin ions were selected for CID, additional low mass signals were observed (Figure 3B) that correspond to preferential (b15, b20, y23, b30, and y33) and non-preferential cleavages (y25, y35). Also, doubly charged fragments of abundant signals seen in the spectrum of singly charged thioredoxin were observed. When triply charged thioredoxin precursor ions were subjected to CID, the same trend toward additional low mass product ions as well as doubly charged ions corresponding to preferential cleavage sites observed in the spectrum of singly charged thioredoxin occurred (Figure 3C). The lower signal-to-noise ratio in Figure 3C is most likely due to the triply charged precursor intensity being approximately 10% that of the singly and doubly charged molecular ions (data not shown). Again, the additional sequence specific information provided by the CID spectra of multiply charged precursor ions in the MALDI TOF-TOF experiment should enhance the ability to identify proteins via database searching algorithms (see below).

Figure 3.

MALDI TOF-TOF product ion spectrum of a) singly charged, b) doubly charged, and c) triply charged thioredoxin. The amino acids in brackets as peak labels indicate the peptide bond broken to produce the assigned product ion.

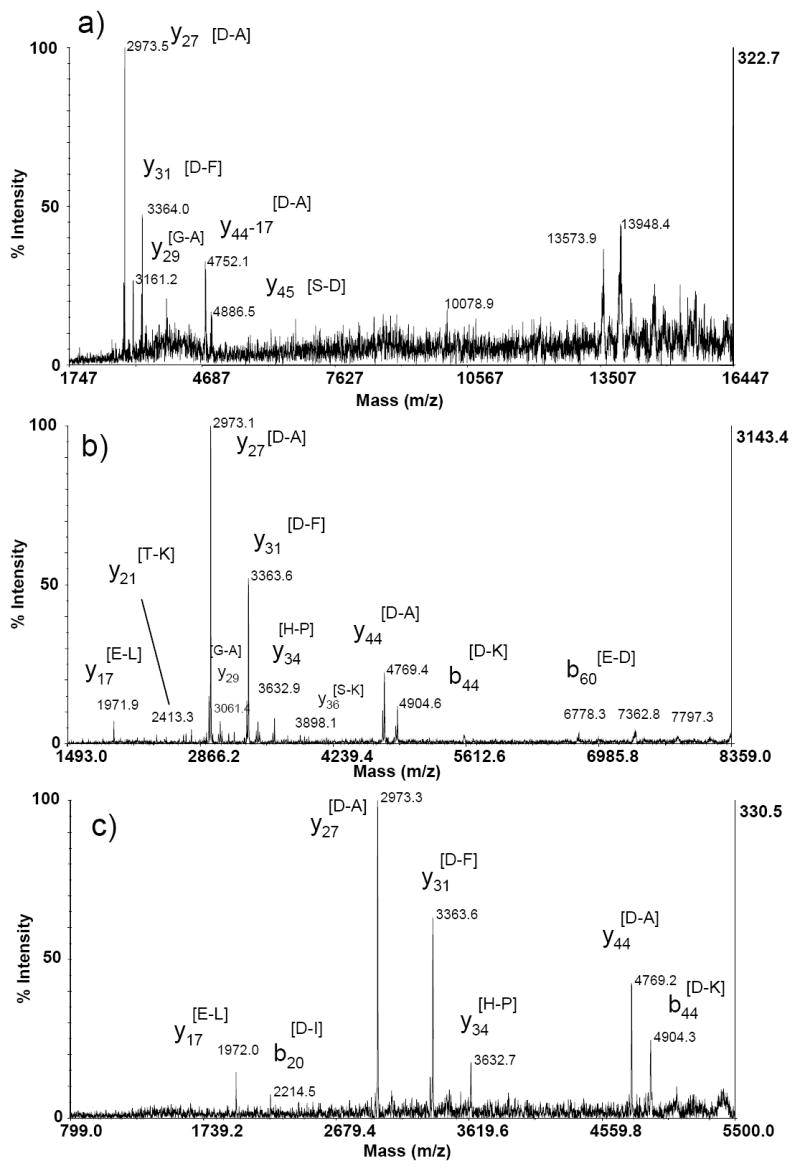

Myoglobin

To the best of our knowledge, only proteins with molecular weight less than 12,000 Da have been directly fragmented using TOF-TOF mass spectrometry. For higher molecular weight proteins, either the efficiency of fragmentation is poor or the product ions can not be well focused or transmitted to the detector. Figure 4A shows a typical MS/MS spectrum of singly charged horse myoglobin (average MW of 16950 Da). There is limited product ion information in the low mass region, such as y27, y31 and y44/b43-NH3 ions. In the high mass region, some unresolved broad signals appear, but are not interpretable in terms of providing sequence specific information. MS/MS spectra of multiply charged (up to 3+) myoglobin ions are presented in Fig. 4B&C. The y17, y27, y31, y44/b43-NH3 and b44 ions dominate the spectra of multiply charged precursor ions and all correspond to preferential cleavage C-terminal to acidic residues.

Figure 4.

MALDI TOF-TOF product ion spectrum of a) singly charged, b) doubly charged, and c) triply charged myoglobin. The amino acids in brackets as peak labels indicate the peptide bond broken to produce the assigned product ion.

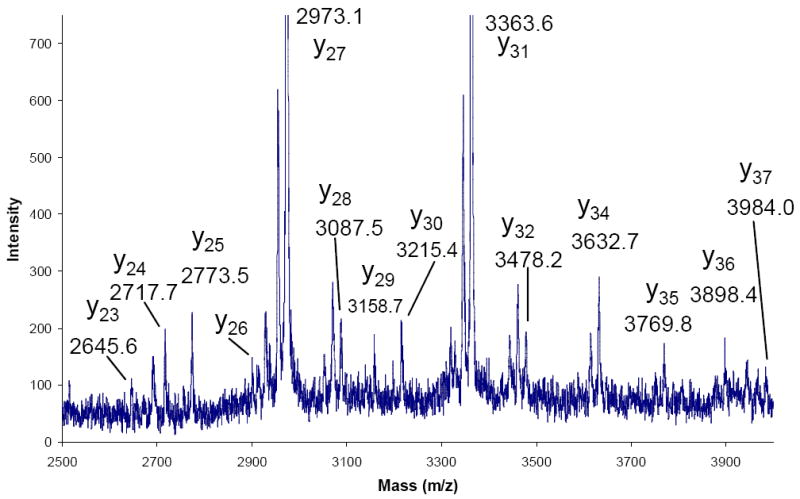

The excellent signal-to-noise ratio and notable observation of the non-preferential cleavage product ions y21, y29, and y36 caused further exploration of low intensity signals in the spectrum of doubly charged myoglobin. In the expanded region of 2500-4000 Th (Figure 5), a nearly complete series of y ions were observed from y23 to y37 with only the y33 ion appearing in the noise. Although these signals are of low abundance, their presence indicates that substantial sequence information in the form of a sequence tag can be generated for intact protein ions up to 17kDa in mass.

Figure 5.

Expanded region of product ion spectrum of doubly charged myoglobin from m/z 2500 to 4000 indicating a nearly complete y series.

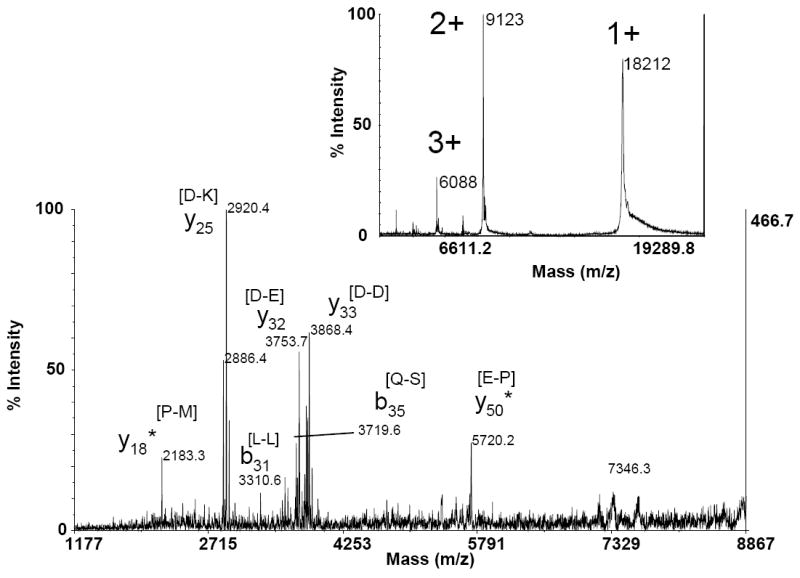

β-lactoglobulin

The highest molecular weight protein examined in this study was β-lactoglobulin, MWave 18320 Da. The MALDI mass spectrum in Figure 6 (insert) indicates the abundance of singly-, doubly-, and triply-charged molecular ions from β-lactoglobulin. The tandem mass spectrum of singly charged β-lactoglobulin did not produce sufficient product ion signals; however, the doubly charged precursor ion at m/z 9122 yielded a series of intense y-series product ions (y25, y32, and y33) resulting from preferential cleavage (Figure 6). Additional product ions due to non-preferential cleavages were also observed at lower intensities. Based on the results presented for myoglobin, we predict that if sufficient numbers of triply charged precursor ions can be generated, additional sequence information could be obtained.

Figure 6.

MALDI TOF-TOF production ion spectrum of doubly charged β-lactoglobulin. Insert shows the MALDI mass spectrum indicating intensities of precursor ions. The amino acids in brackets as peak labels indicate the peptide bond broken to produce the assigned product ion.

Protein Identification

The use of peak lists generated from MS/MS spectra has been shown in preliminary studies with a custom algorithm to be useful for accurate protein identification most likely due to the specificity of the fragmentation observed [42]. In the present study, the use of MS-TAG (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/4.0.8/html/mstag.htm) allows identification of all proteins except bovine beta-lactoglobulin in the current study when masses from the product ion spectra (Figures 2-5) are input using a setting of “no enzyme” and inserting the correct species (supplemental table 1). It is likely that the few product ions observed for beta-lactoglobulin prohibits accurate identification in this case and, as predicted above, if sufficient numbers of triply charged precursor ions could be generated along with an MS/MS spectrum, a positive identification should be possible.

Discussion

The experiments presented in this report demonstrate the utility of multiply charged precursor ion selection in MALDI TOF-TOF experiments for generating sequence specific information. Consistent with other tandem mass spectrometry results on a wide variety of instrument platforms, preferential cleavage C-terminal to acidic residues and N-terminal to proline residues is observed. Moreover, selection and fragmentation of multiply charged precursor ions produced additional product ions, both preferential and non-preferential cleavage products, as well as multiply charged product ions. Using appropriate choices of matrix and sample preparation methods to generate multiply charged precursor ions for subsequent CID, the applicable mass range of MALDI TOF-TOF experiments has been extended to 18.2 kDa. The sequence specific information generated in these experiments can be utilized to search protein databases for protein identification.

Since the discovery of MALDI, it has been clear that sample preparation methods are critically important for the efficient ionization of macromolecules. It follows that sample preparation is also important for the generation of multiply charged protein ions. The use of the ultra-thin layer method with diluted matrix solution in combination with a 1:3:2 FWA spotting solution provides adequate yields of multiply charged ions for MALDI TOF-TOF experiments.

The observation of product ions from multiply charged precursors is not surprising given the extensive literature from electrospray tandem mass spectrometry experiments. It is interesting to note; however, that as larger proteins were examined in the present study, multiply charged precursors provided improved spectral quality and more extensive sequence coverage than singly charged precursors. This may be due to: a) higher ion currents for multiply charged precursors using optimized sample preparation conditions, b) more efficient transmission and focusing of product ions from multiply charged precursors, and/or c) a true charge effect on efficiency of fragmentation. The charge effect may be manifested in at least two ways: 1) charge retention on larger numbers of product ions and/or 2) enhanced charge induced fragmentation efficiency. Given the charge repulsion model of Rockwood et al [43], it seems unlikely that the low charge states examined here would be subject to charge repulsion mechanisms.

It is clear that proteins of increasing mass are amenable to top-down proteomics using the MALDI TOF-TOF platform. The sequence specific information generated by this approach can be used in automated database searches to positively identify proteins (unpublished results). Thus, this experiment can potentially be accomplished in a high throughput manner. Indeed, Demirev et al. have demonstrated the utility of this approach in profiling bacterial proteomes [32]. A key factor in expanding the useable mass range will be the ability to generate multiply charged ions from MALDI ion sources: therefore, examination of MALDI sample preparation strategies, such as non-metallic surfaces [28] and electrospray deposition [31] or even the recently reported MALDESI approach [44], is an important area of future investigation. Obviously, the analytical parameter space available for exploration is large, including sample preparation, activation methods, hardware/software improvements, however, the utility of the approach has been demonstrated albeit with a limited number of small proteins. High throughput top-down proteomics analysis is potentially within reach using the MALDI TOF-TOF platform.

Supplementary Material

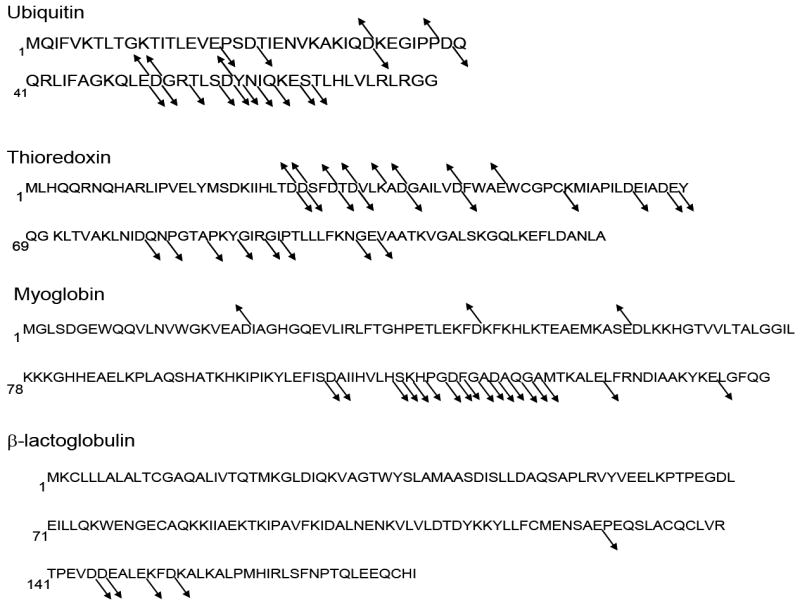

Figure 7.

Protein sequences of the proteins examined in the present study with arrows indicating the observed b- and y-ions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge funding by NIH NHLBI NO1- HV-28181. KLS would like to acknowledge the excellent mentoring and support provided by Dr. R. Graham Cooks throughout his career.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Smith RD. Primary Sequence Information from Intact Proteins by Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Science. 1990;248:201–204. doi: 10.1126/science.2326633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephenson JL, McLuckey SA, Reid GE, Wells JM, Bundy JL. Ion/Ion Chemistry as a Top-Down Approach for Protein Analysis. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2002;13:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mekecha TT, Amunugama R, McLuckey SA. Ion Trap Collision-Induced Dissociation of Human Hemoglobin Alpha-Chain Cations. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2006;17:923–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Lee TD. Charge State Distribution Shifting of Protein Ions Observed in Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1995;6:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu ZY, Schey KL. Optimization of a Maldi Tof-Tof Mass Spectrometer for Intact Protein Analysis. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2005;16:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan JM, McLuckey SA. Charge State Dependent Collision-Induced Dissociation of Native and Reduced Porcine Elastase. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2003;38:245–256. doi: 10.1002/jms.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin M, Campbell JM, Mueller DR, Wirth U. Intact Protein Analysis by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Tandem Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2003;17:1809–1814. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karas M, Gluckman M, Schafer J. Ionization in Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization: Singly Charged Molecular Ions Are the Lucky Survivors. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;35:1–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(200001)35:1<1::AID-JMS904>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zubarev RA, Kelleher NL, McLafferty FW. Electron Capture Dissociation of Multiply Charged Protein Cations. A Nonergodic Process. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1998;120:3265–3266. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerda BA, Horn DM, Breuker K, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron Capture Dissociation of Multiply-Charged Oxygenated Cations. A Nonergodic Process. European Mass Spectrometry. 1999;5:335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zubarev RA, Kruger NA, Fridriksson EK, Lewis MA, Horn DM, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron Capture Dissociation of Gaseous Multiply-Charged Proteins Is Favored at Disulfide Bonds and Other Sites of High Hydrogen Atom Affinity. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1999;121:2857–2862. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breuker K, McLafferty FW. Native Electron Capture Dissociation for the Structural Characterization of Noncovalent Interactions in Native Cytochrome C. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2003;42:4900–4904. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh H, Breuker K, Sze SK, Ge Y, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Secondary and Tertiary Structures of Gaseous Protein Ions Characterized by Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry and Photofragment Spectroscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:15863–15868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212643599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge Y, Lawhorn BG, ElNaggar M, Strauss E, Park JH, Begley TP, McLafferty FW. Top Down Characterization of Larger Proteins (45 Kda) by Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:672–678. doi: 10.1021/ja011335z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breuker K, Oh HB, Horn DM, Cerda BA, McLafferty FW. Detailed Unfolding and Folding of Gaseous Ubiquitin Ions Characterized by Electron Capture Dissociation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:6407–6420. doi: 10.1021/ja012267j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi SDH, Hemling ME, Carr SA, Horn DM, Lindh I, McLafferty FW. Phosphopeptide/Phosphoprotein Mapping by Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:19–22. doi: 10.1021/ac000703z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLafferty FW, Horn DM, Breuker K, Ge Y, Lewis MA, Cerda B, Zubarev RA, Carpenter BK. Electron Capture Dissociation of Gaseous Multiply Charged Ions by Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2001;12:245–249. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLafferty FW. Tandem Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Complex Biological Mixtures. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2001;212:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerda BA, Breuker K, Horn DM, McLafferty FW. Charge/Radical Site Initiation Versus Coulombic Repulsion for Cleavage of Multiply Charged Ions. Charge Solvation in Poly(Alkene Glycol) Ions. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2001;12:565–570. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zubarev RA, Horn DM, Fridriksson EK, Kelleher NL, Kruger NA, Lewis MA, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. Electron Capture Dissociation for Structural Characterization of Multiply Charged Protein Cations. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:563–573. doi: 10.1021/ac990811p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown RS, Lennon JJ. Sequence-Specific Fragmentation of Matrix-Assisted Laser-Desorbed Protein Peptide Ions. Analytical Chemistry. 1995;67:3990–3999. doi: 10.1021/ac00117a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu ZY, Schey KL. Optimization of a Maldi Tof-Tof Mass Spectrometer for Intact Protein Analysis. Journal of the American Chemical Society. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.12.018. Accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaaff TG, Cargile BJ, Stephenson JL, McLuckey SA. Ion Trap Collisional Activation of the (M+2h)(2+)-(M+17h)(17+) Ions of Human Hemoglobin Beta-Chain. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:899–907. doi: 10.1021/ac991344e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells JM, Stephenson JL, McLuckey SA. Charge Dependence of Protonated Insulin Decompositions. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2000;203:A1–A9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton KA, Chrisman PA, Reid GE, Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Gaseous Apomyoblobin Ion Dissociation in a Quadrupole Ion Trap: [M+2h](2+)-[M+21h](21+) International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2001;212:359–376. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells JM, Reid GE, Engel BJ, Pan P, McLuckey SA. Dissociation Reactions of Gaseous Ferro-, Ferri-, and Apo-Cytochrome C Ions. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2001;12:873–876. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(01)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid GE, Stephenson JL, McLuckey SA. Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Ribonuclease a and B: N-Linked Glycosylation Site Analysis of Whole Protein Ions. Analytical Chemistry. 2002;74:577–583. doi: 10.1021/ac015618l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katta V, Chow DT, Rohde MF. Applications of in-Source Fragmentation of Protein Ions for Direct Sequence Analysis by Delayed Extraction Maldi-Tof Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1998;70:4410–4416. doi: 10.1021/ac980034d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen SL, Chait BT. Influence of Matrix Solution Conditions on the Maldi-Ms Analysis of Peptides and Proteins. Analytical Chemistry. 1996;68:31–37. doi: 10.1021/ac9507956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Demirev PA, Feldman AB, Kowalski P, Lin JS. Top-Down Proteomics for Rapid Identification of Intact Microorganisms. Analytical Chemistry. 2005;77:7455–7461. doi: 10.1021/ac051419g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankevich V, Zhang J, Dashtiev M, Zenobi R. Production and Fragmentation of Multiply Charged Ions in ‘Electron-Free’ Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2003;17:2343–2348. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yergey AL, Coorssen JR, Backlund PS, Blank PS, Humphrey GA, Zimmerberg J, Campbell JM, Vestal ML. De Novo Sequencing of Peptides Using Maldi/Tof-Tof. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2002;13:784–791. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marley K, Mooney DT, Clark-Scannell G, Tong TTH, Watson J, Hagen TM, Stevens JF, Maier CS. Mass Tagging Approach for Mitochondrial Thiol Proteins. Journal of Proteome Research. 2005;4:1403–1412. doi: 10.1021/pr050078k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunawardena HP, He M, Chrisman PA, Pitteri SJ, Hogan JM, Hodges BDM, McLuckey SA. Electron Transfer Versus Proton Transfer in Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions of Polyprotonated Peptides. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:12627–12639. doi: 10.1021/ja0526057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coon JJ, Ueberheide B, Syka JEP, Dryhurst DD, Ausio J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Protein Identification Using Sequential Ion/Ion Reactions and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9463–9468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503189102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senko MW, Speir JP, McLafferty FW. Collisional Activation of Large Multiply-Charged Ions Using Fourier-Transform Mass-Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1994;66:2801–2808. doi: 10.1021/ac00090a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little DP, Speir JP, Senko MW, Oconnor PB, McLafferty FW. Infrared Multiphoton Dissociation of Large Multiply-Charged Ions for Biomolecule Sequencing. Analytical Chemistry. 1994;66:2809–2815. doi: 10.1021/ac00090a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan ZQ, Kelleher NL, Oconnor PB, Aaserud DJ, Little DP, McLafferty FW. 193 Nm Photodissociation of Larger Multiply-Charged Biomolecules. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes. 1996;158:357–364. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price WD, Schnier PD, Williams ER. Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Large Biomolecule Ions by Blackbody Infrared Radiative Dissociation. Analytical Chemistry. 1996;68:859–866. doi: 10.1021/ac951038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid GE, Wu J, Chrisman PA, Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Charge-State-Dependent Sequence Analysis of Protonated Ubiquitin Ions Via Ion Trap Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:3274–3281. doi: 10.1021/ac0101095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu W, Vath JE, Huberty MC, Martin SA. Identification of the Facile Gas-Phase Cleavage of the Asp-Pro and Asp-Xxx Peptide Bonds in Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1993;65:3015–3023. doi: 10.1021/ac00069a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schey KL, Schwacke JH. Implementation and Performance of a Protein Identification Algorithm for Intact Protein Maldi/Tof/Tof Spectra. Proceedings of the 51st ASMS Conference; 2003; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia Y, Liang XR, McLuckey SA. Ion Trap Versus Low-Energy Beam-Type Collision-Induced Dissociation of Protonated Ubiquitin Ions. Analytical Chemistry. 2006;78:1218–1227. doi: 10.1021/ac051622b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pitteri SJ, McLuckey SA. Recent Developments in the Ion/Ion Chemistry of High-Mass Multiply Charged Ions. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2005;24:931–958. doi: 10.1002/mas.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.