Abstract

Mice lacking the extracellular matrix protein microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAGP1) display delayed thrombotic occlusion of the carotid artery following injury as well as prolonged bleeding from a tail vein incision. Normal occlusion times were restored when recombinant MAGP1 was infused into deficient animals prior to vessel wounding. Blood coagulation was normal in these animals as assessed by activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time. Platelet number was lower in MAGP1-deficient mice, but the platelets showed normal aggregation properties in response to various agonists. MAGP1 was not found in normal platelets or in the plasma of wild-type mice. In ligand blot assays, MAGP1 bound to fibronectin, fibrinogen, and von Willebrand factor, but von Willebrand factor was the only protein of the 3 that bound to MAGP1 in surface plasmon resonance studies. These findings show that MAGP1, a component of microfibrils and vascular elastic fibers, plays a role in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Introduction

Upon injury to the vessel wall, platelets and protein components of the coagulation pathway interact with the subendothelial extracellular matrix to arrest bleeding through formation of a hemostatic plug. The extracellular matrix (ECM) component collagen has long been known to be an important vessel wall protein that mediates platelet tethering and promotes firm platelet adhesion. However, collagen is not the exclusive subendothelial protein responsible for von Willebrand factor (VWF) interaction.1,2 We now show that another prominent vessel wall ECM component, microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAGP1), also participates in hemostasis

MAGP1 is a component of fibrillin-rich microfibrils. These 10- to 15-nm structures serve multiple functions in the ECM, one of which is to help structure elastic fibers.3–5 In large vessels, microfibrils and elastic fibers produced by smooth muscle cells3 are organized into elastic sheets, or lamellae, that are oriented circumferentially between the cell layers. MAGP1 is also produced by endothelial cells, which are capable of synthesizing elastic fibers under appropriate circumstances.6,7 The MAGP1-containing microfibrils remain at the surface of elastic lamellae where they can easily interact with cells.8–10 In fact, microfibrils have been shown to promote platelet adhesion and subsequent activation and aggregation11,12 through an interaction mediated by von Willebrand factor.13

The biologic function of MAGP1 is unknown. It is a relatively small protein (∼20 kDa) compared with fibrillin (∼350 kDa), its binding partner in the microfibril. The amino-terminal half of the molecule contains trisaccharide and tetrasaccharide O-linked sugars, a site for tyrosine sulfation, and one or more glutamine residues that act as amine acceptors for transglutaminase reactions.14 The carboxyl-terminal half of the protein contains the molecule's 13 cysteine residues and defines a fibrillin-binding domain.15 Other proteins that interact with MAGP1 include tropoelastin,16 collagen VI,17 decorin,18 biglycan,19 and Notch1.20 There is no binding of MAGP1 to collagens I, II, and V.17 MAGP1 can also influence the way that cells interact with ECM and, in this respect, functionally resembles thrombospondin, tenascin, and other members of the matricellular family of ECM proteins. There is no evidence that MAGP1 interacts with integrins, although interactions with other cell-surface matrix-binding proteins have not been extensively studied.

To better understand the functional role of MAGP1, we used gene targeting to inactivate the MAGP1 gene (Mfap2) in mice. The targeting strategy was designed to delete exons 3 to 6, which encode a portion of the signal peptide and nearly half of the coding sequence of the molecule. Analysis of the founder lines confirmed that the targeting strategy had successfully given rise to the expected mutant allele. Progenies from founder lines were initially propagated in a mixed background and then bred into the C57BL/6 and Black Swiss lines. Several traits with variable penetrance were observed in the outbred Black Swiss mice, but most were absent in the inbred C57 background (J.S.W., Thomas J. Brockelmann, R.A.P., C.C.W., Fernando Segade, Russell H. Knutsen, and R.P.M. Deficiency in microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 leads to complex phenotypes in multiple organ systems. Submitted December 2007). One phenotype that persisted with complete penetrance in both backgrounds was prolonged thrombosis and bleeding times after vascular injury. In mice lacking MAGP1, thrombus formation is delayed despite normal blood coagulation in vitro, suggesting that MAGP-containing microfibrils play a role in hemostasis and thrombosis.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Tissue culture reagents were from the Washington University Tissue Culture Support Center (St Louis, MO). Restriction endonucleases and other enzymes were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI) or Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Human von Willebrand factor, fibrinogen, and fibronectin were purchased from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO), Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), or Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) unless noted. Polyclonal MAGP-GST antibody was raised against the amino-terminal half of bovine recombinant MAGP1.14 Monoclonal anti-V5 antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Mice

MAGP1-deficient mice were generated by homologous recombination in RW.4 129/SvJ-derived embryonic stem cells (J.S.W. et al, manuscript submitted). Embryonic stem (ES) cells heterozygous for the knockout construct were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which were transferred into the uteri of pseudopregnant females. The resulting chimeric animals were mated to C57BL/6 females, and agouti offspring were screened by Southern blotting of tail genomic DNA for germ-line transmission of the targeted Mfap2 allele. Knockout-positive animals were initially bred to Black Swiss females and later backcrossed for 10 generations into the C57BL/6 strain, which was used for all studies in this report. The Washington University Animal Studies Committee approved all experimental protocols and all mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility.

Photochemically induced carotid artery thrombosis in mice

The protocol of Eitzman et al21 was followed with slight modification.22 Male mice (10-12 weeks old) were anesthetized with pentobarbital, secured in the supine position, and placed under a dissecting microscope. Following a midline cervical incision, the right common carotid artery was isolated and a Doppler flow probe (model 0.5 VB; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was applied. Thrombosis was induced by injection of rose bengal dye (Fisher Scientific) into the tail vein in a volume of 120 μL at a concentration of 50 mg/kg using a 29-gauge needle. Just before injection, a 1.5 mW, 540 nm green light laser (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) was applied to the desired site of injury from a distance of 6 cm. The laser remained on until thrombosis occurred. Flow in the vessel was monitored with the Doppler probe for 150 minutes from the onset of injury, at which time the animal was humanely killed. In some experiments, various doses of purified recombinant MAGP1 or saline (control) were injected into the tail vein 5 minutes before induction of thrombosis.

Tail vein bleeding time

Tail vein bleeding time was determined as described by Broze et al.23 Briefly, mice were anesthetized (ketamine 75 mg/kg; medetomidine 1 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and placed prone on a warming pad. A transverse incision was made with a scalpel over a lateral vein at a position where the diameter of the tail was 2.25 to 2.5 mm. The tail was immersed in normal saline (37°C) in a hand-held test tube. The time from the incision to the cessation of bleeding was recorded as the bleeding time.

Activated partial thromboplastin time

Citrate-anticoagulated mouse plasma (100 μL) was mixed with 100 μL Alexin HS reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). After a 2-minute preincubation at 37°C, 100 μL of 0.25 M CaCl2 was added and the clotting time was determined.

Prothrombin time

Citrate-anticoagulated mouse plasma (100 μL) was warmed to 37°C for 1 minute and then mixed with 200 μL Thrombomax HS with calcium (Sigma-Aldrich) and the clotting time was determined.

Von Willebrand factor antigen

An immunoturbidometric assay (STA Liatest VWF; Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ) for von Willebrand factor antigen was performed on citrate-anticoagulated mouse plasma according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assay was standardized with normal human plasma.

Analysis of blood cell counts and platelet aggregation

Peripheral blood was obtained by cardiac puncture from anesthetized 12-week-old MAGP1+/+ and MAGP1−/− mice. Platelet number was obtained using a Hemavet 850 automated hematologic analyzer (CDC Technologies, Oxford, CT).

Platelet aggregation was monitored by measuring light transmission through a suspension of stirred washed platelets (1-3 × 108/mL for mouse and 2 × 108/mL for human) or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) using a PAP-4 aggregometer (Bio/Data, Horsham, PA). Aggregation reagents were obtained from Helena Laboratories (Beaumont, TX). Human and mouse washed platelets and PRP were obtained as described by Cazenave et al.24

Ristocetin cofactor assay

Ristocetin cofactor assays were performed to determine the effect of recombinant bovine MAGP1 on human von Willebrand factor activity. The maximum slope of platelet agglutination was measured using a PAP-4 aggregometer (Bio/Data) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reaction mixtures included 400 μL lyophilized human platelets (Bio/Data), 50 μL ristocetin (AggRecetin; Bio/Data), and 50 μL of each test sample. The test samples contained 1 part normal pooled plasma and 3 parts MAGP1 (0-100 μg/mL) diluted in Tris-buffered saline. Standard curves were constructed with 12.5% to 100% plasma in the absence of MAGP1. In experiments with added MAGP1, human plasma was used at a fixed 50% dilution.

Recombinant bovine MAGP1 protein preparation

Full-length bovine MAGP1 cDNA was cloned into the pQE vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and M15 cells were transformed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein was produced and purified using the nickel-NTA agarose system (Qiagen) by incubating bacterial lysates with nickel-NTA agarose and washing according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein was eluted with 8 M urea buffer, pH 4.5, and analyzed for purity and integrity by Coomassie stained gels. The eluted protein was then dialyzed against 2 changes, 4 L each, of 50 mM acetic acid. Protein concentration in dialyzed samples was quantified by amino acid analysis prior to lyophilization.

Blood pressure, vascular distensibility, and cross-sectional area

Mice were anaesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane inhaled through a nose cone and kept warm by radiant heat. A catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted into the right common carotid artery and the blood pressure was monitored for 20 minutes. The isoflurane concentration was reduced to 0.5% during this period for at least 5 minutes and the average heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean pressure were recorded. In other mice, the right common carotid artery was exposed and heparin (1000 units/mL, approximately 50 units/mouse) was injected into the left ventricle to prevent blood clots during dissection. The artery was removed, cannulated, and mounted on a pressure and force arteriograph (Danish Myotechnology, Copenhagen, Denmark). Pressure-diameter curves for the arterial segments from wild-type and MAGP1−/− animals were obtained as described.25,26

For vessel cross-sectional area measurements, wild-type and MAGP−/− animals were anesthetized and the left heart was cannulated to allow perfusion fixation with saline and then Histochoice (Amresco, Solon, OH) fixative at 100 mmHg. The right carotid artery was then dissected free from surrounding tissues and excised from the aortic arch to an area distal to the carotid bifurcation. The vessels were imbedded in paraffin, bifurcation side down, and cut on a microtome using 5-μm sections. Triplicate sections were taken at the bifurcation and every 100 μm from the bifurcation. Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) staining of one section from each genotype at a similar level was performed, and stained sections were imaged using Axiovision software and a Zeiss Axioskop (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY). Image J software (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD) was used to manually trace along the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and the external elastic lamina (EEL) with medial area (expressed in arbitrary units) defined as the area between the 2 lamellae.

Immunohistochemistry

Carotid arteries from thrombosis studies were harvested and frozen in OCT (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Cross sections were obtained, and the slides were air dried, treated with 4°C acetone, and incubated with affinity-purified MAGP-GST antibody (1:1000 dilution). After incubation at room temperature for 1 hour, the slides were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with biotinylated antirabbit secondary antibody. Slides were developed using Elite ABC and DAB kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis

Proteins of interest were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with or without 50 mM dithiothreitol. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred from the gels to nitrocellulose membranes for 1 hour at 70 V in 10 mM 3-[cyclohexylamino]-1-propanesulfonic acid, 10% methanol (vol/vol). For Western blotting analysis, the membranes were first blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature. The blots were then incubated with specific primary antibodies (1:1000) for 1 hour, washed 3 times with blocking buffer, and incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of a peroxidase-linked donkey anti–rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) in blocking buffer for 1 hour. After washing 3 times with PBS, the blots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoblot analysis was also used to assess circulating MAGP1 levels in mouse plasma. Mouse blood was collected from a transected carotid artery directly into a tube containing ACD anticoagulant. Plasma (2 μL) from either wild-type or MAGP1−/− mice was separated by SDS-PAGE using reducing conditions on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. After transfer to nitrocellulose, the blot was developed using a polyclonal rabbit antimouse MAGP1 antiserum (1:500 dilution). To determine the limits of MAGP1 detection, 650 ng/mL, 25 ng/mL, or 1 ng/mL recombinant MAGP1 was added to MAGP1−/− plasma and analyzed by Western blot using identical conditions. Between 1 and 25 nm MAGP1 could be reliably detected using this technique.

Ligand blotting analysis

Ligand blotting was performed as previously described.27 Briefly, proteins were run on SDS-PAGE under either reducing or nonreducing conditions and transferred to nitrocellulose as described in the preceeding paragraph. The blots were blocked after transfer with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature. Purified recombinant MAGP1 was added to the blocking buffer to a final concentration of 1 μg/mL, and the blots were incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C under gentle shaking. Bound protein was detected with MAGP-GST antibody (1 hour at 37°C) after 3 washes with blocking buffer and then incubated with secondary antibody as described above. Ligand blots in which MAGP1 was omitted from the blocking buffer or where primary antibody was omitted were found to be negative.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay

Bovine MAGP1-V5–6His–tagged protein was expressed by SaOS2 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-MAGP1-V5–6His vector.15 After partial purification from the medium using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), samples were dialyzed, lyophilized, and resuspended in 2 mL Tris-buffered saline (TBS).

Fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and fibronectin (100 μg each) were iodinated using Iodogen (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and approximately 106 cpm of each protein was incubated with 200 μL of the partially purified SaOS2 cell–derived MAGP1-V5–6His–tagged protein in 300 μL TBS, 2 mM CaCl2 for 2 hours at room temperature. The specific activity of each protein was as follows: fibronectin = 937 000 cpm/μg; fibrinogen = 410 000 cpm/μg; VWF = 693 000 cpm/μg. To reduce nonspecific binding, immobilized protein A gel (40 μL, Immunopure; Pierce) was added and incubated for 1 hour. After centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with 40 μL immobilized protein A gel plus anti-V5 antibody at 4°C overnight. The samples were centrifuged and the pellets were washed 4 times with 2 mM CaCl2 in TBS buffer. SDS sample buffer (50 μL) was added and the samples heated at 100°C for 5 minutes. An aliquot of the mixture (20 μL) was subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 5% polyacrylamide gel under reducing or nonreducing conditions followed by autoradiography. For competition experiments, a 10-fold excess of unlabeled protein was added during the overnight incubation.

Surface plasmon resonance assays

Interactions between proteins were studied by surface plasmon resonance using the BIAcore X system, at 25°C (Uppsala, Sweden). Recombinant bovine MAGP1 was covalently immobilized on the BIAcore CM-5 sensor chip (carboxylated dextran matrix) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The CM-5 chip was activated with a 1:1 mixture of 75 mg/mL 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide and 11.5 mg/mL N-hydroxysuccinimide for 7 minutes. MAGP1 (36 μg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.3) was injected over the CM-5 sensor chip for 7 minutes at a flow rate of 10 μL/min (25°C). Remaining active groups on the matrix were blocked with 1 M ethanolamine/HCl, pH 8.5. Immobilization of MAGP1 resulted in a surface concentration on the sensorchip of 3.9 ng/mm2. Analytes were prepared in HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA and 0.005% [v/v[surfactant P20; BIAcore) and injected at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. The nonlinear fitting of association and dissociation curves according to a 1:1 model was used for the calculation of kinetic constants (BIAevaluation software, version 3.2; BIAcore). Individual experiments were performed 3 times.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined with the Student 2-tailed t test for independent samples. P at less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

MAGP1-deficient mice have prolonged thrombosis and bleeding times after vascular injury

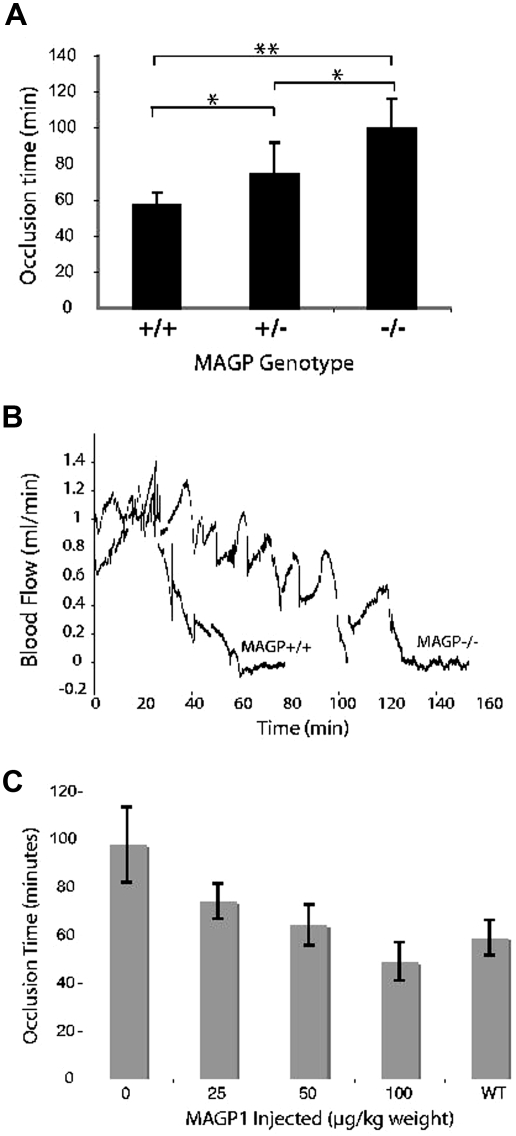

Figure 1A compares the time to thrombus formation after photochemical injury of the common carotid artery of wild-type and MAGP1-deficient mice. In MAGP1−/− mice the occlusion time was 99 plus or minus 16.3 minutes (mean ± SD) compared with 57 plus or minus 6.7 minutes for wild-type animals (P < .005). Interestingly, mice heterozygous for the MAGP1 deletion (MAGP1+/−) showed intermediate values (73 ± 17.8 minutes), indicative of a gene dosage effect. Figure 1B is a representative recording comparing carotid blood flow in wild-type and MAGP1−/− mice. In addition to the prolonged time to cessation of flow, large irregular spikes were frequently observed in the MAGP1−/− animals. This is in contrast to what occurs in the wild-type vessel, which shows a rapid, almost linear, cessation of flow once the clot begins to form.

Figure 1.

Effect of MAGP1 deficiency on thrombotic occlusion of the carotid artery. (A) Blood flow in the common carotid artery was monitored continuously with an ultrasonic flow probe. Local endothelial injury was induced by application of a 540-nm laser beam to the carotid artery followed by injection of rose bengal dye (50 mg/kg) into the lateral tail vein. Shown is the time to occlusion of blood flow following injury. Error bars indicate mean plus or minus standard deviation (n = 8 for each group). **P < .005, *P < .05. (B) Representative blood flow recordings showing the delayed occlusion time and stochastic flow pattern in MAGP1−/− animals. Rose bengal dye was injected at time = 0 minutes. (C) Infusion of recombinant MAGP1 re-establishes normal occlusion time in MAGP1−/− mice. Recombinant bovine MAGP1 was injected into the tail vein as a single bolus 5 minutes before rose bengal injection. An equivalent bolus of saline served as the control. Error bars indicate mean plus or minus SD (n = 6 for each group).

To examine whether the absence of MAGP1 also affects hemostasis in the venous system, we measured the bleeding time in the mouse tail vein.23 After incision, the tail was immersed in saline kept at 37°C, and the bleeding time was taken as the time required for the bleeding to stop. The bleeding times in the MAGP1-deficient mice were almost double those of their MAGP1 wild-type siblings (150 ± 19 vs 81 ± 15 seconds) showing that the absence of MAGP1 affects hemostasis in both high (arterial) and low (venous) blood pressure systems.

Normal occlusion time is restored in the MAGP1-deficient mouse by injection of recombinant MAGP1

Injection of recombinant bovine MAGP1 into the tail vein 5 minutes before laser injury was able to reverse the extended occlusion times documented in MAGP1-deficient mice. As seen in Figure 1C, a MAGP1 dose of 50 μg/kg body weight was sufficient to return the occlusion time values to those observed in wild-type animals (∼60 minutes). The effect was dose dependent over the range of 0 to 100 μg/kg body weight. The dose-dependent response is in agreement with results shown in Figure 1A demonstrating that MAGP+/− mice have occlusion times intermediate between wild-type and MAGP−/− animals. The recombinant protein had no effect at 50 μg/kg on the occlusion time of wild-type animals (not shown).

To insure that the injected amounts of MAGP1 were higher than endogenous circulating MAGP1 levels, plasma from wild-type animals was probed by immunoblot using antibodies to mouse MAGP1. Plasma from MAGP1−/− animals served as a negative control. MAGP1−/− plasma supplemented with known concentrations of recombinant MAGP1 served as a positive control and defined the limits of detection for the assay. No MAGP1 was detected in wild-type plasma using assay conditions that detected as little as 25 ng MAGP1/mL plasma. Hence, even the lowest level of MAGP1 infused in these experiments (25 μg/kg or approximately 0.8 μg/mL plasma) is in excess over any endogenous protein that might exist at concentrations below those detected in our assay.

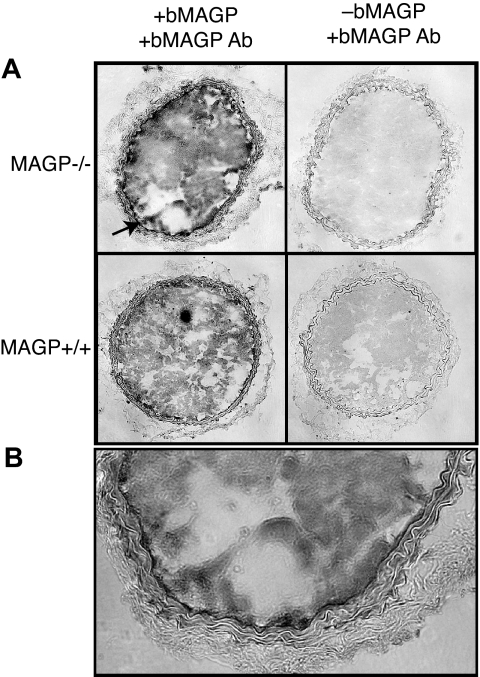

Using an antibody that recognizes bovine but not mouse MAGP1, immunohistochemistry of frozen sections of carotid artery from MAGP1-injected mice documented recombinant protein in the thrombus and vessel wall of both wild-type and MAGP1−/− animals (Figure 2). Interestingly, intense reactivity was associated with the internal elastic lamina of the MAGP1−/− injured vessel with less detectable protein at the injury site in wild-type animals. The presence of recombinant protein at the thrombus-vessel wall interface is consistent with injected MAGP1 binding to the subendothelial region after injury and facilitating thrombus formation and anchorage to the vessel wall.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry showing localization of infused, recombinant bovine MAGP1 at the site of vascular injury. (A) Photomicrographs on the left are cross sections of carotid arteries from MAGP1+/+ and MAGP1−/− mice infused with 50 μg/kg recombinant bovine MAGP1 5 minutes prior to laser-induced injury. Vessels were harvested after complete cessation of blood flow and frozen sections immunostained using a bovine MAGP1-specific antibody. Staining is evident in the thrombus of both genotypes but is particularly prominent in the internal elastic lamina in the MAGP1−/− mouse (↗, and at higher power in panel B). Panels on the right show staining with antibovine MAGP1 of injured vessels from animals not injected with bovine MAGP1.

MAGP1-deficient mice have normal coagulation and platelet function in vitro

Because abnormalities in coagulation cascade pathways can interfere with hemostasis and thrombus formation, we determined the activated partial thromboplastin time and the prothrombin time to assess the functionality of the intrinsic and extrinsic clotting pathways, respectively. Table 1 shows that the clotting parameters are normal in the MAGP1-deficient mice, indicating that the clotting pathways were unaffected by the absence of MAGP1. Von Willebrand factor antigen levels were also similar in wild-type and MAGP1-deficient mice (Table 1); in both cases, the mean levels were approximately 40% that of human pooled plasma.

Table 1.

Hemostatic parameters for MAGP+/+ and MAGP−/− mice

| MAGP1+/+ (n) | MAGP1−/− (n) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aPTT, s | 28.5 ± 1.7 (4) | 29.4 ± 0.7 (3) | .57 |

| PT, s | 11.6 ± 1.5 (3) | 12.6 ± 1.2 (4) | .33 |

| VWF antigen, %* | 42.3 ± 6.4 (3) | 44.5 ± 17.1 (4) | .82 |

Percentage of VWF concentration in normal human plasma.

P values are for comparison between genotypes.

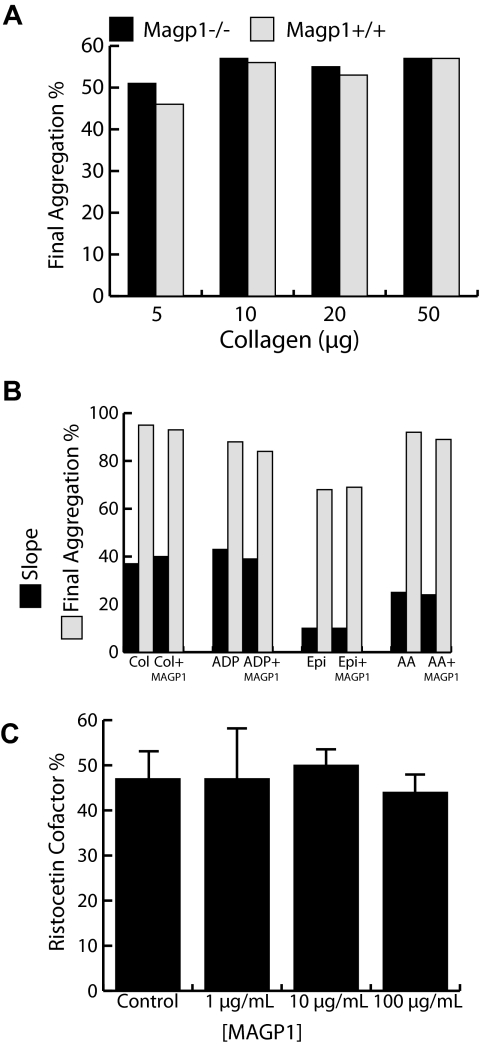

Platelets play an important role during hemostatic plug formation and many bleeding problems are related to abnormal platelets. Therefore, we inspected several platelet parameters in MAGP1−/− mice. While MAGP1-deficient mice have a significantly lower (P < .03) number of platelets (770 ± 202 ×109/L [770 000 ± 202 000 platelets/μL] blood, n = 8) compared with wild-type animals (1020 ± 159 × 109/L [1 020 000 ± 159 000 platelets/μL] blood, n = 7), platelet function was essentially normal. Aggregation assays using platelet-rich plasma (PRP) from MAGP1−/− and wild-type mice with the agonists collagen (Col, 10 μg/mL), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP, 20 μM), arachidonic acid (AA, 500 μg/mL), and epinephrine (Epi, 300 μM) showed no difference between the 2 genotypes. Figure 3A shows representative data for aggregation of platelets from wild-type and MAGP1-deficient animals in response to increasing concentrations of collagen. The results indicated that platelets from both genotypes respond similarly. We also tested whether MAGP1 had a direct effect on human platelet aggregation by conducting aggregation studies with the agonists mentioned above in the presence or absence of recombinant MAGP1 (50 μg/mL). The results showed that, in both cases, there were no differences in any of the aggregation parameters, confirming that in vitro neither the absence nor presence of MAGP1 alters platelet aggregation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Platelet function in MAGP1-deficient mice. (A) The percentage of platelets that aggregate in response to different levels of collagen is the same for both genotypes. (B) The presence of MAGP1 (50 μg/mL) has no effect on human platelet aggregation induced by various agonists, including collagen (Col, 10 μg/mL), adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP, 20 μM), arachidonic acid (AA, 500 μg/mL), and epinephrine (Epi, 300 μM). Aggregation was monitored by measuring light transmission through a suspension of stirred washed platelets (1-3 × 108/mL for mouse and 2 × 108/mL for human) using an aggregometer. Data are expressed as either the slope of the aggregation curve or as percentage of cells that underwent aggregation. (C) Recombinant bovine MAGP1 has no effect on the ristocetin cofactor activity of human plasma. All experiments contained normal human plasma diluted 1:1 with Tris-buffered saline, yielding 50% ristocetin cofactor activity in the control sample. Error bars indicate mean plus or minus standard deviation of 4 experiments. None of the values differed significantly (P ≥ .25).

Additional experiments were performed to determine the effect of recombinant bovine MAGP1 on human von Willebrand factor activity. As shown in Figure 3C, the ristocetin cofactor activity of normal human plasma was unaffected by the presence of MAGP1 at concentrations of 1 to 100 μg/mL. These results suggest that MAGP1 does not modulate the interaction between von Willebrand factor and platelets.

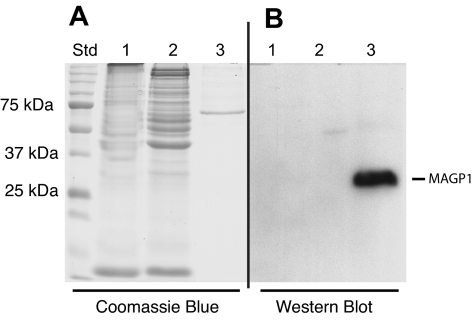

MAGP1 is not present in platelets

The possibility that platelets might contain MAGP1 was investigated by immunoblot of whole washed bovine platelet extracts prepared as described by Cazenave et al.24 Bovine platelets were used to obtain sufficient cells for rigorous biochemical analysis. Figure 4A shows a Coomassie blue–stained gel indicating the distribution and relative amounts of protein in the platelet extract (lanes 1,2). Lane 3 contains partially purified recombinant MAGP1 expressed by transfected SaOS2 cells as a positive control. Although not visible by Coomassie blue staining (lane 3), SaOS2 cell–derived MAGP1 protein was readily detected by immunoblot with the MAGP1-specific antibody (Western blot, lane 3). There was no immunoreactive MAGP1 detected in the platelet extracts (Western blot, lanes 1,2).

Figure 4.

Immunoblot of platelet extracts. Bovine washed platelets were boiled in SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie blue staining or transferred to nitrocellulose for immunodetection with an antibody to bovine MAGP1. (A) Coomassie blue–stained gel. (B) Immunoblot analysis of proteins in panel A after transfer to nitrocellulose. Lane 1: Platelet extract under nonreducing conditions (no DTT). Lane 2: Platelet extract under reducing conditions (+ DTT). Lane 3: Semipurified bovine MAGP1 expressed by mammalian SaOS2 cells (+ DTT).

MAGP1−/− mice have normal vessel structure and blood pressure

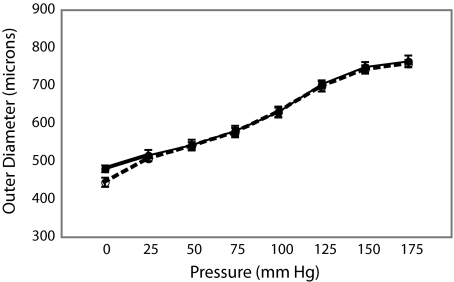

To determine whether the absence of MAGP1 alters vessel structure and cardiovascular hemodynamics, which might impact thrombus formation, blood pressure and vascular compliance were compared between genotypes. Figure 5 shows that pressure-diameter curves are identical for wild-type and MAGP1−/− mice, confirming that vessel diameter is the same for both animals at any given pressure. There were also no significant differences in medial cross-sectional area (287.2 ± 91 units for wild-type vs 341 ± 97 for MAGP1−/−) or in blood pressure (systolic/diastolic = 128/84 for wild-type vs 130/89 for MAGP−/−) between genotypes.

Figure 5.

Outer diameter versus pressure for the right carotid artery in wild-type and MAGP−/− mice. Pressure-diameter curve showing that the carotid artery in wild-type (—) and MAGP−/− (----) animals has identical mechanical properties, identical diameters, and equal pressures.

MAGP1 interacts with fibrinogen, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor

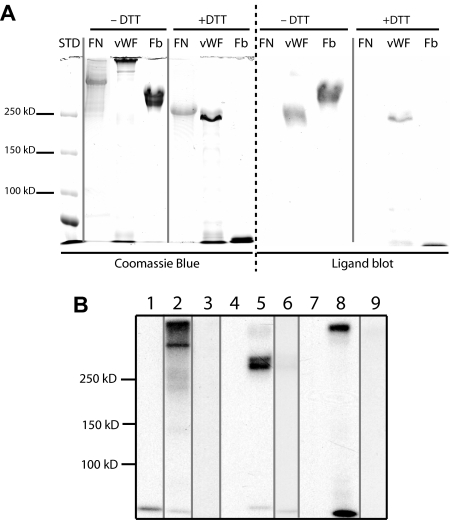

That MAGP1's role in hemostatic plug formation does not appear to be through a direct effect on platelet function suggests a possible interaction with some other plasma or ECM protein. Candidate plasma proteins were tested for binding to MAGP1 using 3 different assay techniques: ligand blots, coimmunoprecipitation, and surface plasmon resonance binding. The results in Figures 6A,B document an interaction between MAGP1 and both von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen. In the immunoprecipitation experiments, the specificity of binding was confirmed by showing that the addition of excess unlabeled fibrinogen or VWF to the precipitation reaction blocked binding of labeled protein. No interaction was observed between MAGP1 and fibronectin by immunoblot, but an interaction with fibronectin was detected in the coimmunoprecipitation experiments.

Figure 6.

Analysis of MAGP1 interaction with selected plasma proteins. MAGP1's ability to interact with plasma proteins was assayed by ligand blot (A) and coimmunoprecipitation (B). (A) Lanes: FN indicates fibronectin; VWF, von Willebrand factor; Fb, fibrinogen; and STD, molecular weight standards. The left side of the panel is a Coomassie blue–stained gel (± DTT) of the separated proteins. The right side shows a ligand blot of the same proteins after transfer to nitrocellulose, incubation with MAGP1, and bound MAGP1 detected with an antibody to MAGP1 after extensive washing to remove unbound protein. (B) SDS-PAGE autoradiogram showing coprecipitation of [125I]-labeled plasma proteins and V5-tagged MAGP1. Lanes: 1, fibronectin with V5 antibody only (negative control); 2, fibronectin coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 using V5 antibody; 3, fibronectin coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 as in lane 2, but in the presence of 10-fold excess unlabeled fibronectin; 4, fibrinogen with V5 antibody; 5, fibrinogen coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 using V5 antibody; 6, fibrinogen coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 as in lane 5, but in the presence of 10-fold excess unlabeled fibrinogen; 7, von Willebrand factor with V5 antibody; 8, von Willebrand factor coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 using V5 antibody; and 9, von Willebrand factor coprecipitated with MAGP1-V5 as in lane 8, but in the presence of 10-fold excess von Willebrand factor. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes.

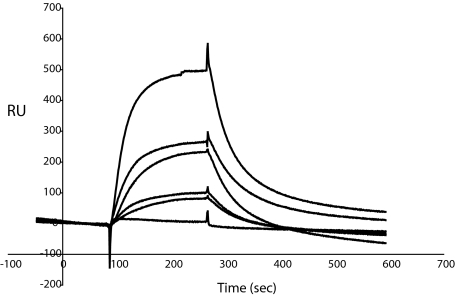

Further characterization of the protein interactions was obtained using surface plasmon resonance with MAGP1 coupled to the sensor chip and fibrinogen, fibronectin, or VWF injected as analyte. Under the assay conditions tested, only von Willebrand factor bound to MAGP1, with a calculated Kd of 2.05 × 10−7 M (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Characterization of MAGP1 and VWF interactions using surface plasmon resonance. Different concentrations of von Willebrand factor were injected over MAGP1 immobilized on a BIAcore CM-5 sensor chip. Sensorgram shows 6 different analyte concentrations (0.052 μM, 0.105 μM, 0.21 μM, 0.32 μM, 0.42 μM, and 0.85 μM). One representative experiment is shown. The response difference (the difference between experimental and control flow cells) is given in resonance units (RU).

Discussion

MAGP1 is an abundant protein found in elastic fibers in blood vessels and in other elastic tissues. Its ability to bind multiple proteins suggests that MAGP1 could be a bridging molecule to facilitate the association and assembly of complex matrix structures.16,18 As we show in this report, mice that lack MAGP1 display a bleeding abnormality characterized by prolonged tail vein bleeding time and delayed thrombotic occlusion of the carotid artery despite having normal blood coagulation parameters. Furthermore, platelet aggregation induced by various agonists is similar between wild-type and knockout animals, suggesting normal in vitro platelet function in the absence of MAGP1. The absence of MAGP1 in platelets is consistent with this conclusion. The bleeding and thrombotic abnormalities have been observed in 2 genetic backgrounds (C57BL/6, this study; and Black Swiss, not shown). MAGP1-deficient mice do not manifest spontaneous hemostatic abnormalities in the absence of vascular injury.

The mechanism responsible for abnormal thrombotic occlusion is not immediately evident, but one possibility is that MAGP1 deficiency diminishes the ability of the thrombus to adhere to the injured blood vessel wall. Because MAGP1 does not interact with integrins, it is unlikely that thrombus stabilization occurs directly through MAGP1-mediated integrin activation of platelets. Detection of MAGP1 in the thrombus and in the vessel wall of MAGP1−/− mice following infusion of MAGP1 protein suggests that it exerts its stabilizing effects by direct interactions between components of the thrombus and components of the vascular matrix. Indeed, we have shown that MAGP1 can interact with several proteins important to thrombus formation and platelet adhesion, including fibrinogen, fibronectin, and VWF. This unusual property suggests that MAGP1 functions to anchor protein components of the thrombus to the structural matrix of the vascular wall.

The location of MAGP1 in the vessel wall makes it ideal to serve an anchoring function for the forming clot. MAGP1 is produced by endothelial cells in culture where it colocalizes with fibrillin to form a honeycomb network underneath the cell layer.7 As a component of elastic fiber microfibrils, MAGP1 is enriched in the elastic lamellae found in all elastic and muscular arteries. In these vessels, the subendothelial matrix consists of the endothelial basement membrane in close association with the internal elastic lamina, such that upon endothelial injury or denudation, the internal elastic lamina will be exposed and will be a major surface for thrombus attachment. In smaller arteries and veins, elastic fibers and microfibrils (and hence MAGP1) are present in the vessel wall even though they do not form the concentric lamellae seen in muscular and elastic arteries. Our data are consistent with several studies showing that microfibrils promote platelet adhesion and aggregation11,12 through an interaction mediated by VWF.13,28 While the microfibrillar component that promotes VWF binding was not characterized in these early studies, our findings identify this protein as MAGP1.

MAGP1 resembles the thrombospondins (TSPs) in its ability to bind multiple proteins and in its propensity to modulate cell-matrix interactions. Even the knockout animals share similarities in that, like MAGP1-null mice, TSP-1– and TSP-2–null mice have hemostatic defects.29 Mice that lack TSP-1, for example, have enhanced thrombus embolization30 caused by defective thrombus adherence to the injured blood vessel wall, similar to what we have described for the MAGP1-deficient mouse. TSP2 mice have a bleeding diathesis that manifests as a prolonged bleeding time. In characterizing the TSP-1 phenotype, no indication was found for a role for TSP-1 in platelet aggregation or in coagulation-mediated thrombosis, but evidence was presented for protection by TSP-1 of VWF cleavage by ADAMTS13.30 Whether MAGP1 can serve a similar function through its ability to bind VWF must await more detailed mapping studies of MAGP1-binding sites within the VWF molecule.

In conclusion, the results presented in this study implicate MAGP1 and, hence, microfibrils and elastic fibers, in hemostasis and thrombosis. Mice lacking MAGP1 have prolonged bleeding after transection of the tail vein and prolonged thrombotic occlusion of the carotid artery after endothelial injury. Since in vitro assays of blood coagulation and platelet function are normal in these mice, the defect in MAGP1 deficiency probably involves impaired interaction of the developing thrombus with components of the vessel wall.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Ciliberto for excellent technical support, Yifang Zhao for assistance with tissue processing and immunohistology, and Russell Knutsen for the vascular compliance and blood pressure studies. We also thank Dr Evan Sadler for providing the von Willebrand factor antibody.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL71960, HL74138, and HL53325 (R.P.M.), HL55520 (D.M.T.), and FAPESP no. 2006/06560-4 (C.C.W.). J.S.W. was supported by training grant T32 HL007873 and by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.C.W. and T.J.B. performed in vitro assays and platelet characterization studies; C.P.V. was responsible for the carotid injury studies; J.S.W. prepared and purified recombinant MAGP1 protein; A.S. contributed the immunohistology; R.A.P. was responsible for the MAGP1 knockout mice; and D.M.T and R.P.M. performed scientific oversight and data interpretation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert P. Mecham, Department of Cell Biology and Physiology, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8228, 660 South Euclid Ave, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: bmecham@wustl.edu.

References

- 1.de Groot PG, Ottenhof-Rovers M, van Mourik JA, Sixma JJ. Evidence that the primary binding site of von Willebrand factor that mediates platelet adhesion on subendothelium is not collagen. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:65–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI113602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner DD, Urban-Pickering M, Marder VJ. Von Willebrand protein binds to extracellular matrices independently of collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:471–475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson MA, Cleary EG. The immunohistochemical localization of microfibril-associated glycoprotein (MAGP) in elastic and non-elastic tissues. Immunol Cell Biol. 1987;65:345–356. doi: 10.1038/icb.1987.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson MA, Kumaratilake JS, Cleary EG. The protein components of the 12-nanometer microfibrils of elastic and non-elastic tissues. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4590–4598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kielty CM, Sherratt MJ, Marson A, Baldock C. Fibrillin microfibrils. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:405–436. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mecham RP, Madaras J, McDonald JA, Ryan U. Elastin production by cultured calf pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1983;116:282–288. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041160304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber E, Rossi A, Solito R, Agliano M, Sacchi G, Gerli R. The pattern of fibrillin deposition correlates with microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1 (MAGP-1) expression in cultured blood and lymphatic endothelial cells. Lymphology. 2004;37:116–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis EC. Smooth muscle cell to elastic lamina connections in the developing mouse arota: Role in aortic medial organization. Lab Invest. 1993;68:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis EC. Endothelial cell connecting filaments anchor endothelial cells to the subjacent elastic lamina in the developing aortic intima of the mouse. Cell Tiss Res. 1993;272:211–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00302726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross R, Bornstein P. The elastic fiber, I: the separation and partial characterization of its macromolecular components. J Cell Biol. 1969;40:366–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.40.2.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birembaut P, Legrand YJ, Bariety J, et al. Histochemical and ultrastructural characterization of subendothelial glycoprotein microfibrils interacting with platelets. J Histochem Cytochem. 1982;30:75–80. doi: 10.1177/30.1.6274953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legrand YJ, Fauvel-Lafeve F. Molecular mechanism of the interaction of subendothelial microfibrils with blood platelets. Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1992;34:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fauvel-Lafeve F, Legrand YJ. Binding of plasma von Willebrand factor by arterial microfibrils. Thromb Haemost. 1990;64:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trask BC, Broekelmann TJ, Mecham RP. Post-translational modifications of microfibril associated glycoprotein-1 (MAGP-1). Biochem. 2001;40:4372–4380. doi: 10.1021/bi002738z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segade F, Trask BC, Broekelmann T, Pierce RA, Mecham RP. Identification of a matrix binding domain in MAGP1 and 2 and intracellular localization of alternative splice forms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11050–11057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown-Augsburger P, Broekelmann T, Mecham L, et al. Microfibril-associated glycoprotein (MAGP) binds to the carboxy-terminal domain of tropoelastin and is a substrate for transglutaminase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28443–28449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finnis ML, Gibson MA. Microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAGP-1) binds to the pepsin-resistant domain of the alpha3(VI) chain of type VI collagen. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22817–22823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trask BC, Trask TM, Broekelmann T, Mecham RP. The microfibrillar proteins MAGP-1 and fibrillin-1 form a ternary complex with the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan decorin. Molec Biol Cell. 2000;11:1499–1507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinboth B, Hanssen E, Cleary EG, Gibson MA. Molecular interactions of biglycan and decorin with elastic fiber components: biglycan forms a ternary complex with tropoelastin and microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3950–3957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto A, Lau R, Hein PW, Shipley JM, Weinmaster G. Microfibrillar proteins MAGP-1 and MAGP-2 induce Notch1 extracellular domain dissociation and receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10089–10097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eitzman DT, Westrick RJ, Xu Z, Tyson J, Ginsburg D. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 deficiency protects against atherosclerosis progression in the mouse carotid artery. Blood. 2000;96:4212–4215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vicente CP, He L, Pavao MS, Tollefsen DM. Antithrombotic activity of dermatan sulfate in heparin cofactor II-deficient mice. Blood. 2004;104:3965–3970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broze GJ, Jr, Yin ZF, Lasky N. A tail vein bleeding time model and delayed bleeding in hemophiliac mice. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:747–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cazenave JP, Ohlmann P, Cassel D, Eckly A, Hechler B, Gachet C. Preparation of washed platelet suspensions from human and rodent blood. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;272:13–28. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-782-3:013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faury G, Pezet M, Knutsen RH, et al. Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1419–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI19028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagenseil JE, Nerurkar NL, Knutsen RH, Okamoto RJ, Li DY, Mecham RP. Effects of elastin haploinsufficiency on the mechanical behavior of mouse arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1209–H1217. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00046.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werneck CC, Trask BC, Broekelmann TJ, et al. Identification of a major microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1-binding domain in fibrillin-2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23045–23051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fauvel F, Grant ME, Legrand YJ, et al. Interaction of blood platelets with a microfibrillar extract from adult bovine aorta: requirement for von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:551–554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyriakides TR, Zhu YH, Smith LT, et al. Mice that lack thrombospondin 2 display connective tissue abnormalities that are associated with disordered collagen fibrillogenesis, an increased vascular density, and a bleeding diathesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:419–430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonnefoy A, Daenens K, Feys HB, et al. Thrombospondin-1 controls vascular platelet recruitment and thrombus adherence in mice by protecting (sub)endothelial VWF from cleavage by ADAMTS13. Blood. 2006;107:955–964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]