Abstract

The Hedgehog (Hh) signalling pathway has a crucial role in several developmental processes and is aberrantly activated in a variety of cancers. In Drosophila, many of the canonical Hh pathway components are phosphorylated, yet the precise role of these phosphorylation events in the regulation of Hh signal transduction is unclear. Furthermore, the Hh pathway receives input from several kinases that have well-described roles in other cellular functions, some of which have both positive and negative effects on Hh signalling. Several recent studies have characterized the role of specific phosphorylation events in the Hh pathway, and have begun to shed light on how phosphorylation of Hh signalling components affects their subcellular location, stability and activity to mediate the transcriptional response to the Hh gradient.

Keywords: Costal2, Fused, Hedgehog, kinase, phosphorylation

Introduction

Hedgehog (Hh) family proteins are secreted molecules that have a role in many developmental processes, as well as regulating tissue homeostasis in adults. Impaired Hh signalling results in birth defects and recently an alarming number of reports have also implicated inappropriate Hh pathway activation in several types of cancer, providing a strong impetus for understanding the mode of action of Hh.

Several proteins have been identified that regulate the cellular response to secreted Hh in Drosophila melanogaster (Hooper & Scott, 2005). The transmembrane proteins Patched (Ptc) and Interference Hedgehog (Ihog) are required for cells to receive Hh. In the presence of Hh, Ptc activity is repressed, resulting in the de-repression of another transmembrane protein, Smoothened (Smo). Smo then acts through a protein complex containing the kinesin-like protein Costal2 (Cos2), the Ser/Thr kinase Fused (Fu) and the transcription factor Cubitus interruptus (Ci); Smo de-repression results in the stabilization of Ci and its translocation to the nucleus, where it can regulate Hh target genes (Fig 1). Ci transcriptional activity is also regulated through its binding to Suppressor of Fu (Sufu), although the precise role of Sufu remains elusive. Together, the Hh signalling components are able to translate various levels of Hh ligand into different Ci-dependent transcriptional responses. In the Drosophila wing imaginal disc—in which Hh activity is required for patterning of the adult wing—high levels of Hh induce ‘high-level' target genes such as engrailed (en) and ptc, whereas lower levels of Hh induce ‘low-level' target genes such as decapentaplegic (dpp), collier (col) and iroquois (iro). Much of our understanding of the Hh pathway originates from genetic studies involving the deletion or overexpression of pathway components. However, these types of approach have proven inadequate for describing the complex interactions among the Hh pathway components, many of which seem to have dual roles or are involved in feedback loops.

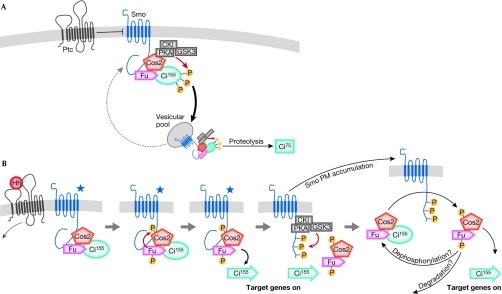

Figure 1.

Model for Hedgehog pathway signalling. (A) The pathway in the absence of Hedgehog (Hh). Patched (Ptc) represses Smoothened (Smo) through an unknown mechanism. Unphosphorylated Smo, Costal2 (Cos2), Fused (Fu) and Cubitus interruptus (Ci)155 form a complex that cycles between the plasma membrane (PM) and a vesicular compartment. Cos2 sequesters protein kinase A (PKA), casein kinase I (CKI) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), directing their activity towards Ci155, which primes the molecule for proteolysis to Ci75. (B) Activation of the signalling pathway by Hh. Ptc repression of Smo is released, causing an unknown change in the Smo molecule (de-repressed Smo is indicated by a star). De-repressed Smo activates Fu, leading to Cos2 phosphorylation and the release of transcriptionally active Ci155 (denoted by an arrow), and resultant dissociation/destabilization of phosphorylated Cos2/Fu. Smo is phosphorylated and stabilized at the PM, where it can further activate other unphosphorylated Cos2–Fu–Ci complexes.

Various Hh signalling components are phosphorylated on multiple residues. Interestingly, some kinases have a role in both pathway repression in the absence of Hh and pathway activation in the presence of Hh. Such opposing dual roles for particular kinases are also observed in the Wnt/Wingless pathway (Price, 2006), suggesting that these pathways might share analogous regulatory mechanisms through phosphorylation. Several recent studies have investigated the role of particular phosphorylation events in Hh signal transduction. Here, we discuss the role of phosphorylation in the Drosophila Hh pathway and attempt to consolidate these recent findings into a model of the cellular response to Hh. We also examine the conservation of the regulation of Hh signalling by phosphorylation from invertebrates to vertebrates.

Kinases acting in the Hh pathway

The Ser/Thr kinase Fu is a positive regulator of Hh signalling in Drosophila, as the absence of Fu reduces pathway activation (Alves et al, 1998). Fu does not display homology with other known kinase subfamilies and seems to function uniquely in the Hh signalling pathway. Fu is composed of two domains: a catalytic amino-terminal domain (Fu-Kin) and a carboxy-terminal regulatory domain (Fu-Reg) that mediates Fu interactions with other proteins. Fu associates with Cos2 in a stoichiometric manner (Ascano et al, 2002; Robbins et al, 1997), and can also interact directly with both Smo and Sufu (Malpel et al, 2007; Monnier et al, 1998). Cos2 and Sufu phosphorylation in response to Hh depends on Fu kinase activity (Dussillol-Godar et al, 2006; Lum et al, 2003; Nybakken et al, 2002); however, it remains to be shown whether this effect is direct. Indeed, the difficulty in purifying functional Fu protein has hindered the identification of its direct substrates, and so its consensus target motif is unknown. Fu is phosphorylated in response to Hh (Therond et al, 1996), and it has been proposed that Fu activity is autoregulated through an intramolecular mechanism (Ascano & Robbins, 2004). Furthermore, there is evidence indicating that phosphorylation of Thr 158 has a role in the regulation of Fu activity (Fukumoto et al, 2001). However, both the underlying mechanism of activation of Fu in response to Hh and the effect of Fu phosphorylation on its activity remain unclear.

Protein kinase A (PKA), casein kinase I (CKI) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) cooperate at several levels to regulate Hh signalling. All three of these Ser/Thr kinases bind to Cos2, and phosphorylate homologous domains on Ci and Smo (Fig 2). Phosphorylation of Ci by PKA, CKI and GSK3 is required for the efficient processing of Ci155 to its transcriptional repressor form, Ci75 (Chen et al, 1998; Jia et al, 2002; Price & Kalderon, 2002), indicating that it has an inhibitory effect on the pathway. Indeed, the loss of phosphorylation by any of these kinases leads to Ci155 accumulation and ectopic target-gene activation owing to reduced Ci155 proteolysis (Jia et al, 2002; Price & Kalderon, 2002). Conversely, phosphorylation of specific PKA and CKI sites on the C terminus of Smo is required for pathway activation in the presence of Hh (Jia et al, 2004; Zhang et al, 2004). A GSK3 consensus site has also been identified in the Smo C terminus; however, the importance of this site is not clear, as an alanine substitution has no effect (Apionishev et al, 2005). The mechanism by which Hh mediates the switch from the negative effect of these kinases to the positive effect is unclear, but it might involve a reorganization/dissociation of the Smo–Cos2–Fu–Ci complex on Hh reception (see below).

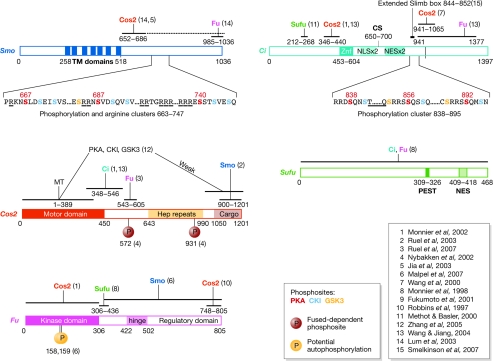

Figure 2.

Hedgehog pathway components and their domains. Important structural domains, binding domains and phosphorylation sites are indicated. The numbers in parentheses indicate the reference in which the domain was characterized. When several references are indicated, the smallest domain characterized is shown. Ci, Cubitus interruptus; CKI, casein kinase I; Cos2, Costal 2; CS, cleavage site; Hep repeats, heptad repeats; Fu, Fused; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; MT, microtubule-interacting domain; NES, nuclear-export signal; NLS, nuclear-localization signal; PEST sequence, a region rich in the amino acids proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine (S) or threonine (T); PKA, Protein kinase A; Smo, Smoothened; Sufu, Suppressor of Fu; TM, transmembrane domains; Znf, zinc finger.

Smo displays homology to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are often associated with Ser/Thr kinases called G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GPRKs). Drosophila Gprk2 has a positive role in Hh signalling (Molnar et al, 2007) and is also a transcriptional target of Hh signalling, indicating a potential mechanism of signal amplification. GPRK2 is required for Smo phosphorylation and internalization in vertebrates (Chen et al, 2004); therefore, it is possible that Gprk2 mediates pathway activity by a similar mechanism in Drosophila. Despite the regulation of Smo by a GPRK, it is important to note that there is no strong evidence of any GPCR-like function for Smo.

Maintaining pathway inactivation in the absence of Hh

In the absence of Hh, Ptc limits the levels of Smo at the plasma membrane. There is evidence that Smo cycles between the plasma membrane and an intracellular compartment in the absence of Hh (Jia et al, 2004; Ruel et al, 2003); therefore, Ptc might prevent Smo accumulation by promoting Smo re-internalization, by reducing its ability to cycle back to the plasma membrane or by increasing its degradation (Denef et al, 2000; Nakano et al, 2004). Consequently, total Smo levels are low in the absence of Hh, and the Smo that is present is associated with Cos2, Fu and Ci (Lum et al, 2003; Ruel et al, 2003). Interestingly, Smo is destabilized in the absence of Hh, whereas Cos2 and Fu are stabilized; it is not clear how Cos2 and Fu escape degradation despite their association with Smo.

Cos2 exerts a negative effect on the Hh pathway. Cos2 has a crucial role in mediating the proteolysis of Ci155 to Ci75 in the absence of Hh. Cos2 recruits PKA, CKI and GSK3 to hyperphosphorylate Ci155, which creates recognition sites for Slimb/Skp1/Cullin/F-box (Slimb/SCF) ubiquitin ligase complexes and directs Ci155 to the proteasome to be cleaved to Ci75 (Jiang & Struhl, 1998; Smelkinson et al, 2007; Zhang et al, 2005). Indeed, the absence of Cos2 can induce ectopic accumulation of Ci155 owing to the lack of Ci proteolysis, which can be restored in this context by overexpressing PKA, GSK3 and CKI (Zhang et al, 2005).

In the absence of Hh, Fu is in a non-phosphorylated and presumably inactive state, which is potentially mediated by autoinhibition through its regulatory domain (Ascano & Robbins, 2004). There is evidence that Fu-Reg is required for the proteolysis of Ci155 to Ci75, indicating a structural role for Fu that is independent of its kinase activity (Lefers et al, 2001; Methot & Basler, 2000). Although Fu relies heavily on Cos2 for stability—as reducing levels of Cos2 reduces levels of Fu (Lum et al, 2003; Ruel et al, 2003)—it is not clear whether a reciprocal arrangement exists between Fu and Cos2. Indeed, there is some evidence for destabilization of Cos2 in cells treated with Fu double-stranded RNA (Liu et al, 2007). This could explain the requirement of the Fu-Reg domain for efficient Ci proteolysis, as Fu constructs with deletions in this domain lose the ability to bind to Cos2 (Robbins et al, 1997) and might therefore lose the ability to stabilize Cos2. Alternatively, it is possible that Fu has a more general structural role in stabilizing the Smo–Fu–Cos2–Ci complex to allow efficient Ci processing. Furthermore, the direct binding of Fu to the C terminus of Smo was recently proposed to have a negative role in Hh signalling (Malpel et al, 2007). Overall, it remains to be determined precisely how Fu acts to silence the Hh pathway.

Phosphorylation events mediating the response to Hh

On binding to Hh, Ptc is inhibited, allowing activation of downstream signalling. Phosphorylation of Smo, Fu, Cos2 and Sufu can be observed in response to Hh, but it is not known how Ptc inhibition triggers these phosphorylation events. Although the presence of Smo is required for phosphorylation of Fu, Cos2 and Sufu, it is unclear whether Smo must itself be phosphorylated to mediate this effect.

Smo is hyperphosphorylated in response to Hh, which induces a conformational change in its C-terminal tail through electrostatic interactions between negatively charged phosphorylated residues that neutralize adjacent clusters of positively charged amino acids (Fig 2; Zhao et al, 2007). Phosphorylated Smo is more stable than the non-phosphorylated form (Denef et al, 2000), and a mutant form of Smo (SmoSD123)—with the three PKA and six CKI phosphorylation sites changed to aspartate residues to mimic phosphorylation—is stabilized at the plasma membrane in the absence of Hh (Jia et al, 2004). This suggests that the phosphorylation and stability of Smo are causally linked, and that the phosphorylation of Smo C-terminal residues is sufficient to stabilize Smo at the plasma membrane and to activate target genes, even in the presence of Ptc activity. It is interesting to note that Hh can induce further accumulation of SmoSD123 (Jia et al, 2004), suggesting either that additional phosphorylation sites exist on Smo or that inhibition of Ptc can act to further stabilize phosphorylated Smo at the membrane. Indeed, there is evidence for additional Hh-stimulated phosphorylation sites on Smo other than PKA and CKI (Apionishev et al, 2005; Zhang et al, 2004), some of which might be regulated by Gprk2 (Molnar et al, 2007).

Fu also becomes hyperphosphorylated in the presence of Hh, and this activity depends on the presence of Smo (Lum et al, 2003; Ruel et al, 2003). Although Fu kinase activity and Fu phosphorylation are observed in the presence of Hh, it is not clear whether phosphorylation of Fu necessarily affects its kinase activity. Alternatively, Fu phosphorylation could regulate its stability or its interaction with other proteins. Therefore, the regulation of Fu activity in the presence of Hh remains largely unknown. On the basis of the recent finding that a membrane-tethered Fu construct is constitutively active, it is tempting to speculate that translocation of Fu to the plasma membrane is sufficient for its activation (Claret et al, 2007). Evidence also indicates that Fu kinase activity is required for Smo phosphorylation and accumulation (Claret et al, 2007), placing Fu activation upstream of these events.

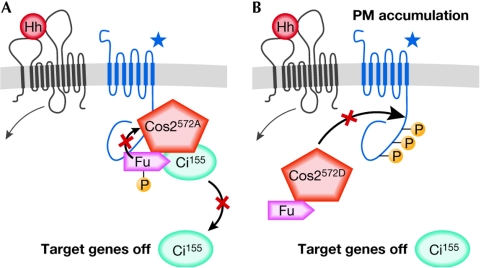

In addition to its role in Ci degradation, Cos2 exerts a negative effect on Smo. Overexpression of Cos2 inhibits Smo phosphorylation and accumulation at the plasma membrane (Jia et al, 2003; Ruel et al, 2003). This inhibitory effect is probably mediated by the direct binding of Cos2, through its C terminus, to Smo (Fig 2). Recently, a functional role for Fu-dependent phosphorylation of Cos2 on Ser 572 has been shown, as an alanine substitution at this position blocked Hh pathway activation (Fig 3A; Liu et al, 2007; Ruel et al, 2007). On Cos2 phosphorylation, the association of Cos2 with Ci and Smo is strongly reduced. Furthermore, substitution of Ser 572 to an aspartate residue (CosS572D), which mimics phosphorylation, also strongly reduced the association of Cos2 with Ci and Smo, leading to the ectopic stabilization of Ci. Ectopically expressed Cos2S572D did not activate Hh target genes in vitro or in vivo, indicating that signalling in Hh-receiving cells might require a dynamic change in the phosphorylation status of Cos2 (Fig 3B). The fact that En expression is lost in cells lacking Cos2 (despite the accumulation of Ci155), and is restored in cells lacking both Cos2 and Sufu (Wang et al, 2000), indicates that Cos2 is necessary to antagonize Sufu. It is possible that unphosphorylated Cos2 is required to recruit Fu/Ci/Sufu to Smo, and that Fu kinase activity then leads to phosphorylation of Sufu and Cos2. On phosphorylation, Cos2 dissociates from Smo and Ci to allow target-gene activation. Therefore, Cos2 could have a positive role in the pathway both by stabilizing Fu and by mediating the interaction of Fu with its substrates.

Figure 3.

Effects of different Cos572 mutations on Hedgehog signalling. (A) When the Costal2 (Cos2) phosphorylation site Ser 572 is mutated to an alanine (A), which is a residue that cannot be phosphorylated, this mutant protein can be found bound to Fused (Fu), Smoothened (Smo) and Cubitus interruptus (Ci), but cannot be released from this complex in response to Hedgehog (Hh). This restricts the activation of Smo, as well as the release and activation of Ci155. (B) When Ser 572 is replaced with a phosphomimetic residue, aspartate (D), Cos2 can no longer interact with Smo and Ci. This allows Smo to accumulate at the plasma membrane (PM), and Ci to be free of Cos2 repression; however, Ci is not processed to its active form.

Hh signalling induces the destabilization of Fu and Cos2, whereas Smo levels are increased (Lum et al, 2003; Ruel et al, 2003). It was recently proposed that Cos2S572D was less stable in vitro than either wild-type Cos2 or Cos2S572A (Liu et al, 2007), raising the possibility that Cos2 phosphorylation is coupled to its degradation. It is not known whether Cos2 phosphorylation is reversible and further studies are necessary to characterize the fate of phosphorylated Cos2.

Owing to the homology between the phosphorylation domains in Ci and Smo, it is tempting to speculate that Cos2 is also necessary to recruit the same kinases to Smo as for Ci. Moreover, it has been proposed that Cos2 is required for Hh-induced Smo stabilization in Hh-receiving cells (Lum et al, 2003). However, several pieces of evidence indicate that little, if any, Cos2 is required for the phosphorylation and stabilization of Smo. Indeed, on Hh reception, Cos2 is destabilized and dissociates from PKA, CKI and GSK3 (Zhang et al, 2005). Furthermore, Smo stability is unaffected in cells lacking Cos2 in vivo (Nakano et al, 2004; Ruel et al, 2003), and Hh-induced Smo phosphorylation and cell-surface accumulation can still be observed in cultured cells in which Cos2 levels are severely reduced by RNA interference (Liu et al, 2007). Finally, Hh-dependent Smo stabilization is also normal in cells lacking Fu and Cos2 in vivo (Liu et al, 2007). These findings suggest that Cos2 is not required to bring together Smo and the kinases that phosphorylate it, but that Smo phosphorylation and stabilization in the absence of Cos2 is still subject to regulation by Hh.

Sufu is phosphorylated in response to Hh and this event is dependent on Fu kinase activity (Dussillol-Godar et al, 2006). Sufu strongly associates with Ci (Lum et al, 2003) and can compete with Cos2 for binding with an N-terminal domain of Ci155 (Wang & Jiang, 2004). Although the loss of Sufu does not result in a change in wing phenotype (Pham et al, 1995), a decrease in the protein levels of both Ci155 and Ci75 can be seen in disc extracts (Lefers et al, 2001; Ohlmeyer & Kalderon, 1998). This decrease in total Ci levels might render the pathway more sensitive to additional aberrations, as Sufu loss enhances the phenotype caused by the lack of Cos2 (Preat et al, 1993). There is evidence indicating that Sufu can stabilize Ci by competing with particular ubiquitin-ligase adaptor proteins for binding to Ci (Zhang et al, 2006). Conversely, ectopic expression of Sufu in the disc weakly reduces the expression of target genes at the anterior–posterior boundary, and causes ectopic dpp and Ptc expression further from the Hh source, owing to the stabilization of Ci155 (Dussillol-Godar et al, 2006). These findings point not only to a role for Sufu in stabilizing Ci, but also to a negative role for Sufu in Hh-receiving cells. Consistent with this idea, Smelkinson and colleagues have shown that the activity of a form of Ci that is unable to undergo proteolysis can be enhanced by the loss of Sufu (Smelkinson et al, 2007). Furthermore, it has been proposed that Sufu limits nuclear entry and activity of Ci (Methot & Basler, 2000); however, the precise mechanism remains unclear, as Sufu can itself translocate into the nucleus in the presence of Ci and Hh. Interestingly, the phenotype of Fu-Kin mutants can be rescued by the loss of Sufu (Preat et al, 1993), which points to a role for Fu in antagonizing Sufu. Overall, it is possible that Sufu buffers Ci levels by preventing Ci degradation, while at the same time suppressing Ci activity.

Is there a common signalling mechanism for all levels of Hh?

On the basis of our knowledge of the Hh pathway, we support a model in which, in the absence of Hh, Cos2 binds to PKA, CKI and GSK3 to direct their activity towards Ci and away from Smo, leading to Ci proteolysis (Fig 1A). On Hh stimulation, Ptc can no longer inhibit Smo, inducing Fu-dependent Cos2 phosphorylation and release/degradation, and therefore stabilizing an active form of Ci155 and allowing the unbound kinases access to Smo (Fig 1B). Phosphorylation of Smo induces a conformational change resulting in its stabilization and accumulation at the plasma membrane. Therefore, Cos2 has a negative effect on Smo accumulation and Fu is able to relieve this inhibition by the phosphorylation of Cos2. Phosphorylated Smo is also able to further induce Fu/Cos phosphorylation (Ruel et al, 2007), indicating that unphosphorylated Fu/Cos2 might still be recruited to phosphorylated Smo to be activated (Fig 1B). This model indicates that Fu activity, Cos2 phosphorylation and Smo accumulation are required to some extent for all levels of Hh signalling, and that the prevalence of these events is directly controlled by the level of Hh.

Conservation of phosphorylation in the Hh pathway

Although it has been proposed that Hh signalling has diverged downstream of Smo in vertebrates, there is still controversy about the precise role of Fu and Cos2, and their functional homologues. Sufu might have a similar role in zebrafish to that in flies; however, it has a crucial repressive role in mice (Huangfu & Anderson, 2006), perhaps assuming some of the repressive functions of Fu and Cos2. In cultured mouse fibroblast cells, the absence of the two closest homologues of Cos2—Kif7 and Kif27—does not perturb Hh signalling (Varjosalo et al, 2006); however, morpholino knockdown experiments indicate that the zebrafish homologue of Kif7 acts like Cos2, as a negative regulator of the pathway (Tay et al, 2005). In addition, the knockdown of one of the Fu homologues in mice does not impair Hh signalling (Huangfu & Anderson, 2006), although the zebrafish homologue of Fu seems to be required (Wolff et al, 2003). Therefore, despite the potential for in vivo redundancy with related kinases and kinesins, there seems to have been a divergence within the Hh pathway between fish and mice.

The Smo C-terminal tail has diverged notably between mammals and flies. The PKA and CKI phosphorylation sites found in Drosophila Smo (dSmo) are not conserved in mammalian Smo (mSmo). It has recently been shown that mSmo, similar to dSmo, undergoes a conformational change in response to Hh, and that a cluster of positively charged amino acids is important in regulating this change (Zhao et al, 2007), suggesting that different phosphorylation sites regulate the electrostatic interaction in mSmo. Indeed, several residues in loop 3, as well as in the C-terminal tail, are essential for high-level mSmo activation (Varjosalo et al, 2006; Zhao et al, 2007). Intriguingly, one report describes a positive role for PKA in Hh signalling in chicken embryos (Tiecke et al, 2007), indicating that it might regulate another domain of Smo or interfere at another level of the pathway. As mentioned earlier, mSmo can also be phosphorylated by GPRK2 (Chen et al, 2004). Therefore, despite sequence divergence between dSmo and mSmo, the mechanism of Smo activation by phosphorylation seems to be conserved.

Although in vertebrates the function of Ci has been split between its three vertebrate homologues, glioma-associated oncogene homologue 1 (Gli1), Gli2 and Gli3, the phosphorylation sites for PKA, CKI and GSK3 are conserved (Price & Kalderon, 2002; Jia et al, 2002). Concordantly, in vitro analysis has shown a role for GSK3 and CKI in the proteolysis of Gli proteins (reviewed by Riobo & Manning, 2007), although no genetic analysis has been performed in vertebrates to determine their in vivo functions. Nevertheless, in both mouse and zebrafish, the absence of PKA activity leads to activation of Hh signalling (Hammerschmidt et al, 1996; Epstein et al, 1996). In addition, it seems that phosphorylation of the Gli proteins primes them for ubiquitination by the Slimb homologue β-Trcp and subsequent proteolysis, resulting in either full degradation or processing to a repressor form (Riobo & Manning, 2007). Therefore, the regulation of Ci/Gli and Smo by phosphorylation seems to be conserved between insects and vertebrates.

Conclusions and perspectives

Although there are still several important gaps in our understanding of Hh signalling (Sidebar A), the characterization of the functional role of specific phosphorylation sites on Hh signalling components has provided new information on how these proteins communicate. There is evidence for additional phosphorylation sites on Cos2 (Nybakken et al, 2002; Ruel et al, 2007) and Smo (Apionishev et al, 2005; Zhang et al, 2004), and there is even an indication that Ptc might be phosphorylated (Denef et al, 2000). In addition, the use of phosphatase inhibitors has indicated that Ser/Thr phosphatases can regulate Hh pathway activity (Denef et al, 2000; Ruel et al, 2007), and a genome-wide RNA-interference screen in S2 cells identified protein phosphatase 2A as being required for the activation of a reporter gene in the presence of Hh (Nybakken et al, 2005). Biochemical and genetic characterization of how phosphorylation events affect the interaction of Hh signalling components, and their stability and activity, will certainly provide much-needed insight into how these proteins cooperate to translate the extracellular morphogen gradient into a graded transcriptional response.

Sidebar A | Key questions in Hedgehog-mediated phosphorylation events.

Fused (Fu): What are the substrates of Fu? Does Fu phosphorylation trigger its catalytic activation?

Costal2 (Cos2): What happens to phospho-Cos2; is it degraded or recycled to a dephosphorylated form?

Suppressor of Fu (Sufu): How is cytoplasmic anchoring of Cubitus interruptus by Sufu regulated by the pathway? How does phosphorylation affect Sufu function?

Smoothened (Smo): What is the first event in Smo activation: stability at the plasma membrane or phosphorylation? What are the different phosphorylation states of Smo? What is the fate of phosphorylated/active Smo?

From left: Pascal P. Thérond, Katie L. Ayers & Reid A. Aikin

Acknowledgments

R.A.A. and P.P.T. are supported by the Ligue Contre le Cancer, ‘équipe labelisée 2008'. K.L.A. is supported by a Marie Curie fellowship. The authors thank S. Raisin, L. Ruel and A. Gallet for helpful discussions and for critically reviewing the manuscript.

References

- Alves G, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Tricoire H, Brissard-Zahraoui J, Lamour-Isnard C, Busson D (1998) Modulation of Hedgehog target gene expression by the Fused serine–threonine kinase in wing imaginal discs. Mech Dev 78: 17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apionishev S, Katanayeva NM, Marks SA, Kalderon D, Tomlinson A (2005) Drosophila Smoothened phosphorylation sites essential for Hedgehog signal transduction. Nat Cell Biol 7: 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascano M Jr, Robbins DJ (2004) An intramolecular association between two domains of the protein kinase Fused is necessary for Hedgehog signaling. Mol Cell Biol 24: 10397–10405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascano M Jr, Nybakken KE, Sosinski J, Stegman MA, Robbins DJ (2002) The carboxyl-terminal domain of the protein kinase Fused can function as a dominant inhibitor of Hedgehog signaling. Mol Cell Biol 22: 1555–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Ren XR, Nelson CD, Barak LS, Chen JK, Beachy PA, de Sauvage F, Lefkowitz RJ (2004) Activity-dependent internalization of Smoothened mediated by β-arrestin 2 and GRK2. Science 306: 2257–2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Gallaher N, Goodman RH, Smolik SM (1998) Protein kinase A directly regulates the activity and proteolysis of Cubitus interruptus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2349–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret S, Sanial M, Plessis A (2007) Evidence for a novel feedback loop in the Hedgehog pathway involving Smoothened and Fused. Curr Biol 17: 1326–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef N, Neubuser D, Perez L, Cohen SM (2000) Hedgehog induces opposite changes in turnover and subcellular localization of Patched and Smoothened. Cell 102: 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussillol-Godar F, Brissard-Zahraoui J, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Boucher D, Fouix S, Lamour-Isnard C, Plessis A, Busson D (2006) Modulation of the suppressor of Fused protein regulates the Hedgehog signaling pathway in Drosophila embryo and imaginal discs. Dev Biol 291: 53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DJ, Marti E, Scott MP, McMahon AP (1996) Antagonizing cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in the dorsal CNS activates a conserved Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Development 122: 2885–2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto T, Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Fujisawa K, Nagata S, Fukunaga R (2001) The Fused protein kinase regulates Hedgehog-stimulated transcriptional activation in Drosophila Schneider 2 cells. J Biol Chem 276: 38441–38448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt M, Bitgood MJ, McMahon AP (1996) Protein kinase A is a common negative regulator of Hedgehog signaling in the vertebrate embryo. Genes Dev 10: 647–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper JE, Scott MP (2005) Communicating with Hedgehogs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 306–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Anderson KV (2006) Signaling from Smo to Ci/Gli: conservation and divergence of Hedgehog pathways from Drosophila to vertebrates. Development 133: 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Amanai K, Wang G, Tang J, Wang B, Jiang J (2002) Shaggy/GSK3 antagonizes Hedgehog signalling by regulating Cubitus interruptus. Nature 416: 548–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Tong C, Jiang J (2003) Smoothened transduces Hedgehog signal by physically interacting with Costal2/Fused complex through its C-terminal tail. Genes Dev 17: 2709–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Tong C, Wang B, Luo L, Jiang J (2004) Hedgehog signalling activity of Smoothened requires phosphorylation by protein kinase A and casein kinase I. Nature 432: 1045–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Struhl G (1998) Regulation of the Hedgehog and Wingless signalling pathways by the F-box/WD40-repeat protein Slimb. Nature 391: 493–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefers MA, Wang QT, Holmgren RA (2001) Genetic dissection of the Drosophila Cubitus interruptus signaling complex. Dev Biol 236: 411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cao X, Jiang J, Jia J (2007) Fused–Costal2 protein complex regulates Hedgehog-induced Smo phosphorylation and cell-surface accumulation. Genes Dev 21: 1949–1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum L, Zhang C, Oh S, Mann RK, von Kessler DP, Taipale J, Weis-Garcia F, Gong R, Wang B, Beachy PA (2003) Hedgehog signal transduction via Smoothened association with a cytoplasmic complex scaffolded by the atypical kinesin, Costal-2. Mol Cell 12: 1261–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malpel S, Claret S, Sanial M, Brigui A, Piolot T, Daviet L, Martin-Lanneree S, Plessis A (2007) The last 59 amino acids of Smoothened cytoplasmic tail directly bind the protein kinase Fused and negatively regulate the Hedgehog pathway. Dev Biol 303: 121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methot N, Basler K (2000) Suppressor of Fused opposes Hedgehog signal transduction by impeding nuclear accumulation of the activator form of Cubitus interruptus. Development 127: 4001–4010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar C, Holguin H, Mayor F Jr, Ruiz-Gomez A, de Celis JF (2007) The G-protein-coupled receptor regulatory kinase GPRK2 participates in Hedgehog signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7963–7968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier V, Dussillol F, Alves G, Lamour-Isnard C, Plessis A (1998) Suppressor of Fused links Fused and Cubitus interruptus on the Hedgehog signalling pathway. Curr Biol 8: 583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier V, Ho KS, Sanial M, Scott MP, Plessis A (2002) Hedgehog signal transduction proteins: contacts of the Fused kinase and Ci transcription factor with the kinesin-related protein Costal2. BMC Dev Biol 2: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Nystedt S, Shivdasani AA, Strutt H, Thomas C, Ingham PW (2004) Functional domains and sub-cellular distribution of the Hedgehog transducing protein Smoothened in Drosophila. Mech Dev 121: 507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken K, Vokes SA, Lin TY, McMahon AP, Perrimon N (2005) A genome-wide RNA interference screen in Drosophila melanogaster cells for new components of the Hh signaling pathway. Nat Genet 37: 1323–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken KE, Turck CW, Robbins DJ, Bishop JM (2002) Hedgehog-stimulated phosphorylation of the kinesin-related protein Costal2 is mediated by the serine/threonine kinase Fused. J Biol Chem 277: 24638–24647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlmeyer JT, Kalderon D (1998) Hedgehog stimulates maturation of Cubitus interruptus into a labile transcriptional activator. Nature 396: 749–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham A, Therond P, Alves G, Tournier FB, Busson D, Lamour-Isnard C, Bouchon BL, Preat T, Tricoire H (1995) The Suppressor of Fused gene encodes a novel PEST protein involved in Drosophila segment polarity establishment. Genetics 140: 587–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preat T, Therond P, Limbourg-Bouchon B, Pham A, Tricoire H, Busson D, Lamour-Isnard C (1993) Segmental polarity in Drosophila melanogaster: genetic dissection of Fused in a Suppressor of Fused background reveals interaction with costal-2. Genetics 135: 1047–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MA (2006) CKI, there's more than one: casein kinase I family members in Wnt and Hedgehog signaling. Genes Dev 20: 399–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MA, Kalderon D (2002) Proteolysis of the Hedgehog signaling effector Cubitus interruptus requires phosphorylation by glycogen synthase kinase 3 and casein kinase 1. Cell 108: 823–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riobo NA, Manning DR (2007) Pathways of signal transduction employed by vertebrate Hedgehogs. Biochem J 403: 369–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins DJ, Nybakken KE, Kobayashi R, Sisson JC, Bishop JM, Therond PP (1997) Hedgehog elicits signal transduction by means of a large complex containing the kinesin-related protein Costal2. Cell 90: 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel L, Rodriguez R, Gallet A, Lavenant-Staccini L, Therond PP (2003) Stability and association of Smoothened, Costal2 and Fused with Cubitus interruptus are regulated by Hedgehog. Nat Cell Biol 5: 907–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel L, Gallet A, Raisin S, Truchi A, Staccini-Lavenant L, Cervantes A, Therond PP (2007) Phosphorylation of the atypical kinesin Costal2 by the kinase Fused induces the partial disassembly of the Smoothened–Fused–Costal2–Cubitus interruptus complex in Hedgehog signalling. Development 134: 3677–3689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelkinson MG, Zhou Q, Kalderon D (2007) Regulation of Ci-SCF(Slimb) binding, Ci proteolysis, and Hedgehog pathway activity by Ci phosphorylation. Dev Cell 13: 481–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay SY, Ingham PW, Roy S (2005) A homologue of the Drosophila kinesin-like protein Costal2 regulates Hedgehog signal transduction in the vertebrate embryo. Development 132: 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therond PP, Knight JD, Kornberg TB, Bishop JM (1996) Phosphorylation of the Fused protein kinase in response to signaling from Hedgehog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 4224–4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiecke E, Turner R, Sanz-Ezquerro JJ, Warner A, Tickle C (2007) Manipulations of PKA in chick limb development reveal roles in digit patterning including a positive role in Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Dev Biol 305: 312–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varjosalo M, Li SP, Taipale J (2006) Divergence of Hedgehog signal transduction mechanism between Drosophila and mammals. Dev Cell 10: 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Jiang J (2004) Multiple Cos2/Ci interactions regulate Ci subcellular localization through microtubule dependent and independent mechanisms. Dev Biol 268: 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Amanai K, Wang B, Jiang J (2000) Interactions with Costal2 and Suppressor of Fused regulate nuclear translocation and activity of Cubitus interruptus. Genes Dev 14: 2893–2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff C, Roy S, Ingham PW (2003) Multiple muscle cell identities induced by distinct levels and timing of hedgehog activity in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Biol 13: 1169–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Williams EH, Guo Y, Lum L, Beachy PA (2004) Extensive phosphorylation of Smoothened in Hedgehog pathway activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17900–17907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Zhang L, Wang B, Ou CY, Chien CT, Jiang J (2006) A Hedgehog-induced BTB protein modulates Hedgehog signaling by degrading Ci/Gli transcription factor. Dev Cell 10: 719–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Zhao Y, Tong C, Wang G, Wang B, Jia J, Jiang J (2005) Hedgehog-regulated Costal2–kinase complexes control phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of Cubitus interruptus. Dev Cell 8: 267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Tong C, Jiang J (2007) Hedgehog regulates Smoothened activity by inducing a conformational switch. Nature 450: 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]