Abstract

Background

Chronic wound pathogenic biofilms are host-pathogen environments that colonize and exist as a cohabitation of many bacterial species. These bacterial populations cooperate to promote their own survival and the chronic nature of the infection. Few studies have performed extensive surveys of the bacterial populations that occur within different types of chronic wound biofilms. The use of 3 separate16S-based molecular amplifications followed by pyrosequencing, shotgun Sanger sequencing, and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis were utilized to survey the major populations of bacteria that occur in the pathogenic biofilms of three types of chronic wound types: diabetic foot ulcers (D), venous leg ulcers (V), and pressure ulcers (P).

Results

There are specific major populations of bacteria that were evident in the biofilms of all chronic wound types, including Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Peptoniphilus, Enterobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Finegoldia, and Serratia spp. Each of the wound types reveals marked differences in bacterial populations, such as pressure ulcers in which 62% of the populations were identified as obligate anaerobes. There were also populations of bacteria that were identified but not recognized as wound pathogens, such as Abiotrophia para-adiacens and Rhodopseudomonas spp. Results of molecular analyses were also compared to those obtained using traditional culture-based diagnostics. Only in one wound type did culture methods correctly identify the primary bacterial population indicating the need for improved diagnostic methods.

Conclusion

If clinicians can gain a better understanding of the wound's microbiota, it will give them a greater understanding of the wound's ecology and will allow them to better manage healing of the wound improving the prognosis of patients. This research highlights the necessity to begin evaluating, studying, and treating chronic wound pathogenic biofilms as multi-species entities in order to improve the outcomes of patients. This survey will also foster the pioneering and development of new molecular diagnostic tools, which can be used to identify the community compositions of chronic wound pathogenic biofilms and other medical biofilm infections.

Background

Biofilms are well documented as medical problems associated with implants [1-9] and certain diseases [10-17]. However, the nature and importance of chronic wound pathogenic biofilms (CWPB) is only now beginning to be realized as reviewed and discussed in the scientific literature [18-25]. Chronic wounds, including diabetic foot ulcers (D), venous leg ulcers (V), and pressure ulcers (P), are often resistant to natural healing and require long term medical care [26-38]. Chronic wounds and their associated pathogenic biofilms [20,22,24,39-44] are also associated as a primary contributing factor in hundreds of thousands of annual deaths and billions of dollars in direct medical costs annually [20,22,38,45-55].

For decades, medical microbiologists have relied on culture techniques to elucidate the complexity of infections including CWPB [56,57]. These techniques with only minor advancements have been used over the past 150 years and are currently the mainstay of the clinical microbiology laboratories. These culture methods can be used to identify the "culturable" bacteria associated with such biofilms. However, the use of laboratory culture techniques is typically only able to detect (as isolates) those organisms which grow relatively quickly and easily in laboratory media. This presents an important problem and descrepency because many of the bacteria in wound biofilms are recalcitrant to culture [58]. Thus, there is a lack of information about the diversity of populations that occur in association with CWPB. A better understanding of bacterial populations associated with CWPB is necessary to enable development of next generation management and therapeutics [59-62].

No studies have been identified which have utilized deep sequencing molecular methods (pyrosequencing) to evaluate the diversity of microbial populations that occur within the pathogenic biofilms associated with each of the three major types of chronic wounds. This report describes the first use of partial ribosomal amplification and pyrosequencing (PRAPS) to look at the microbial diversity in chronic wounds. Combined with two more traditional molecular methods; full ribosomal amplification, cloning and Sanger sequencing (FRACS) and partial ribosomal amplification, density gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and Sanger sequencing (PRADS) we are providing a comprehensive survey of the microbial populations that are present in three types of chronic wound biofilms: venous leg ulcers, diabetic foot ulcers, and pressure ulcers. The compilation of data obtained with each of these methods provides one of the first comprehensive surveys of bacteria that are occur in three different types of chronic wound biofilms.

Results and Discussion

Comparison of Molecular Methods and wound types

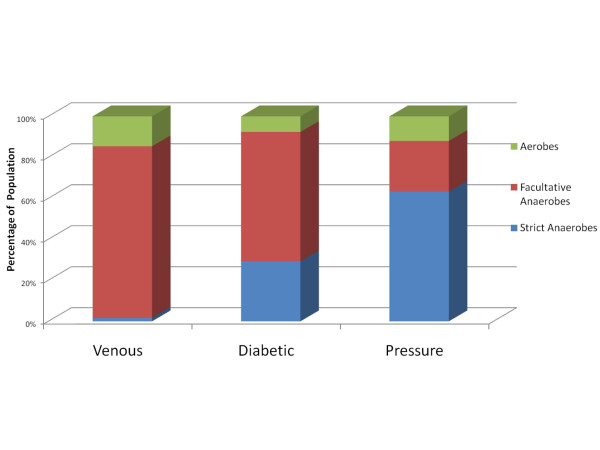

It should be noted that this paper is not intended to contrast each of the molecular methods, or to purposefully compare wound types, but rather to detail the results of each individually in the hopes of gaining an understanding of the microbial diversity within pathogenic biofilms. Although this study could be used to compare or contrast the three molecular methods, we sought instead to use these relatively different strategies to better survey and report the diversity in the different types of wounds. A portion of the bias of one molecular method (e.g. due to primer specificity and universality) we intended to be somewhat compensated by the other methods, each of which utilize different "universal" 16S primers. Another important note is that these analyses do not represent the diversity within a given wound from a single patient; instead these data represented diversity among a given chronic wound type. In-depth comparison of the populations between each wound type as part of this study would also have been outside the scope of the methodologies and experimental design employed. The primary observations that could be logically employed when comparing wound types are two-fold. Each wound type demonstrated populations and diversity that were markedly more prevalent than those seen in other wound types as discussed below. Each wound group also demonstrated a different level of oxygen tolerance among its bacterial populations (Figure 1). This second observation indicates there may be a common pathophysiology among wound types that likely affects the ecology of the wound environment and may play an important role in determining the bacterial genera that can become integrated as part of a wound biofilm. These observations obviously cannot be fully addressed within the scope of this survey yet they do provide important directions for future research.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Bacterial Populations in Chronic Wounds in Relation to Aerotolerance. Diabetic, venous, or pressure ulcer types were analyzed separately using pyrosequencing and the resulting populations grouped into 3 catagories based upon their suggested aerotolerance. This figure graphically illustrates the relative distribution of these functional catagories among the wound types.

PRAPS

The Rowher lab [63] was the first to pyrosequencing approaches to evaluate the diversity of complex microbial ecosystems by looking at environmentally isolated genome sequences from two sites in the Soudan Mine, Minnesota, USA. A few studies have utilized a PRAPS approach to evaluate the genetic diversity of clinical samples [64] or as as a form of clinical isolate genotyping [65-69]. To date, PRAPS has not been used to evaluate the biodiversity of clinically infected biofilm samples, particularly CWPB.

A total of 193890 sequences were generated among the 4 samples including the pooled control sample of which over 129,000 sequences were utilized in the actual PRAPS analysis, gave a comprehensive functional survey of pathogenic biofilm populations within each wound type (Table 1). Facultative gram negative rods predominated in the V wounds. The predominant bacterial types in V biofilms were Enterobacter, Serratia, Stenotrophomonas, and Proteus spp. (Table 2). Strict anaerobes, cocci, and gram positives were scarce. In D samples the primary bacterial genera were Staphylococcus, Peptoniphilus, Rhodopseudomonas, Enterococcus, Veillonella, Clostridium, and Finegoldia spp. Facultative and strict anaerobic gram positive cocci were most prevalent (Table 3). Finally, in P samples, the predominant species were Peptoniphilus, Serratia, Peptococcus, Streptococcus, and Finegoldia spp. Thus, strict anaerobic gram positive cocci dominated the communities within P biofilms (Table 4).

Table 1.

Overview of the phenotypes of microbial populations as determined using pyrosequencing (PRAPS).

| Pressure Ulcer seq | Pressure Ulcer genus | Diabetic Foot Ulcer seq | Diabetic Foot Ulcer genus | Venous Let Ulcer seq | Venous Leg Ulcer genus | |

| Anaerobe | 17105 | 12 | 10519 | 15 | 523 | 6 |

| Aerobe | 3241 | 9 | 2740 | 12 | 4402 | 9 |

| Facultative anaerobes | 6686 | 15 | 22673 | 19 | 25226 | 16 |

| Gram positive | 18751 | 18 | 22821 | 20 | 984 | 12 |

| Gram negative | 8281 | 17 | 13111 | 26 | 29167 | 19 |

| Rod | 8384 | 25 | 14682 | 34 | 29729 | 25 |

| Cocci | 18648 | 12 | 21250 | 12 | 422 | 6 |

| UWB | 440 | 8 | 656 | 7 | 1724 | 3 |

The data from pyrosequencing (PRAPS) is broken down into the number of sequences (seq) from each sample associated with the indicated phenotypic characteristic (anaerobe, gram positive, etc). Also shown are the number of genera that were associated with each of the phenotypic categories. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to a database sequences.

Table 2.

Results obtained for venous leg ulcer sample using pyrosequencing (PRAPS). This table provides the identified genera of the bacteria found using pyrosequencing (PRAPS) in the V sample, the number of sequences corresponding to a given genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the relative shape (rod or cocci) of the genus.

| Genus | Seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Enterobacter spp. | 14288 | 44.83 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Serratia spp. * | 6132 | 19.24 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Stenotrophomonas spp. | 3532 | 11.08 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| Proteus spp. | 2469 | 7.75 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| UWB | 1446 | 4.54 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| Proteus mirabilis. | 1080 | 3.39 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Salmonella spp. | 739 | 2.32 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Clostridium spp. | 408 | 1.28 | + | Anaerobe | Rod |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | 337 | 1.06 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| UWB | 261 | 0.82 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| Pseudomonas spp.* | 185 | 0.58 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| Staphylococcus spp.* | 143 | 0.45 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Brevundimonas diminuta | 123 | 0.39 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| Streptococcus spp. | 107 | 0.34 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 102 | 0.32 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| Enterococcus spp. | 94 | 0.29 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Pantoea spp. | 81 | 0.25 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Corynebacterium striatum* | 81 | 0.25 | + | Aerobe | Rod |

| Peptoniphilus spp. | 65 | 0.20 | + | Anaerobe | Cocci |

| E. coli | 31 | 0.10 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Bacillus spp. | 25 | 0.08 | + | Aerobe | Rod |

| Paenibacillus spp. | 24 | 0.08 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Eubacterium spp. | 24 | 0.08 | + | Anaerobe | Rod |

| Klebsiella spp. | 21 | 0.07 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Xanthomonas spp. | 17 | 0.05 | - | Aerobe | Rod |

| UWB | 17 | 0.05 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| Ferrimonas spp. | 17 | 0.05 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Finegoldia magna | 13 | 0.04 | + | Anaerobe | Cocci |

| Dendrosporobacter quercicolus | 13 | 0.04 | - | Anaerobe | Rod |

UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences. * The asterisk identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the V pool. The only bacterium cultured that was not found using PRAPS was Citrobacter. The % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

Table 3.

Results obtained for diabetic foot ulcer sample using pyrosequencing (PRAPS).

| Genus | Seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 10874 | 29.72 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Peptoniphilus spp. | 2555 | 6.98 | + | Anaerobic | Cocci |

| RhodoPseudomonas spp. | 2541 | 6.94 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Enterococcus spp. | 2341 | 6.40 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Veillonella spp. | 1978 | 5.41 | - | Anaerobic | Cocci |

| Clostridium spp. | 1975 | 5.40 | + | Anaerobic | Rod |

| Finegoldia magna | 1953 | 5.34 | + | Anaerobic | Cocci |

| Haemophilus spp. | 1701 | 4.65 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 1301 | 3.56 | - | Aerobic | Rod |

| Morganella spp. | 1240 | 3.39 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Serratia spp. | 1125 | 3.07 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Proteus spp. | 1072 | 2.93 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Dialister spp. | 1029 | 2.81 | - | Anaerobic | Rod |

| Streptococcus spp. | 751 | 2.05 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Stenotrophomonas spp. | 669 | 1.83 | + | Aerobe | Rod |

| Peptococcus niger | 588 | 1.61 | + | Anaerobic | Cocci |

| UWB | 342 | 0.93 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| Klebsiella spp. | 326 | 0.89 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Actinomyces spp. | 307 | 0.84 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Gordonia spp. | 302 | 0.83 | + | Aerobic | Rod |

| Delftia spp. | 251 | 0.69 | - | Aerobic | Rod |

| Gemella spp. | 168 | 0.46 | + | Anaerobic | Cocci |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 157 | 0.43 | + | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| UWB | 143 | 0.39 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| UWB | 107 | 0.29 | unk | Unk | Unk |

| Salmonella enterica | 102 | 0.28 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 99 | 0.27 | - | Anaerobic | Rod |

| Varibaculum cambriense | 54 | 0.15 | + | Anaerobic | Rod |

| Enterobacter spp. | 52 | 0.14 | - | Facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Bacillus spp. | 51 | 0.14 | + | aerobic | Rod |

| Eikenella spp. | 42 | 0.11 | - | facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Anaerococcus spp. | 42 | 0.11 | + | anaerobic | Cocci |

| Hydrogenophaga spp. | 40 | 0.11 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | 36 | 0.10 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| E coli | 32 | 0.09 | - | facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Sphingomonas spp. | 26 | 0.07 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| Acidovorax spp. | 26 | 0.07 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| Prevotella spp. | 22 | 0.06 | - | anaerobic | Rod |

| UWB | 20 | 0.05 | unk | unk | Unk |

| Eubacterium spp. | 20 | 0.05 | + | anaerobic | Rod |

| Bacteroides spp. | 20 | 0.05 | - | anaerobic | Rod |

| UWB | 17 | 0.05 | unk | unk | Unk |

| UWB | 16 | 0.04 | unk | unk | Unk |

| Selenomonadaceae spp. | 16 | 0.04 | - | anaerobic | Rod |

| Brevibacterium spp. | 14 | 0.04 | + | aerobic | Rod |

| Riemerella spp. | 13 | 0.04 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| UWB | 11 | 0.03 | unk | unk | Unk |

| Bradyrhizobium spp. | 11 | 0.03 | - | aerobic | Rod |

| Pantoea agglomerans | 10 | 0.03 | - | facultative anaerobe | Rod |

This table provides the identified genus of the bacteria found using pyrosequencing (PRAPS) in the D sample, the number of sequences corresponding to this genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the shape of the genus. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences. * The asterisk identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the diabetic foot ulcer pool (D sample). Bacteria that were cultured and were not found using PRAPS include Citrobacter and Pseudomonas. % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

Table 4.

Results obtained for the pressure ulcer sample (P) using pyrosequencing (PRAPS).

| Genus | Seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Peptoniphilus spp. | 10543 | 38.38 | + | Anaerobe | Cocci |

| Serratia spp. | 5234 | 19.05 | - | facultative anaerobe | Rod |

| Peptococcus niger. | 3042 | 11.07 | + | anaerobe | Cocci |

| Streptococcus spp. | 3016 | 10.98 | + | facultative anaerobe | Cocci |

| Finegoldia magna | 1743 | 6.34 | + | anaerobe | Cocci |

| Dialister spp. | 1374 | 5.00 | - | anaerobe | rod |

| Pectobacterium spp. | 528 | 1.92 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Enterobacter spp. | 392 | 1.43 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Proteus spp. | 308 | 1.12 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Veillonella spp. | 186 | 0.68 | - | anaerobe | cocci |

| UWB | 141 | 0.51 | Unk | unk | unk |

| UWB | 121 | 0.44 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Clostridium spp. | 93 | 0.34 | + | anaerobe | rod |

| Corynebacterium striatum | 73 | 0.27 | + | aerobe | rod |

| Delftia spp. | 65 | 0.24 | - | aerobe | rod |

| UWB | 63 | 0.23 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Enterococcus spp. | 62 | 0.23 | + | facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 56 | 0.20 | + | facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Hydrogenophaga spp. | 54 | 0.20 | - | aerobe | rod |

| Eggerthella lenta | 33 | 0.12 | + | anaerobe | rod |

| UWB | 31 | 0.11 | Unk | unk | unk |

| UWB | 31 | 0.11 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Prevotella spp. | 31 | 0.11 | - | anaerobe | rod |

| Varibaculum cambriense | 28 | 0.10 | + | anaerobe | rod |

| Actinomyces europaeus | 28 | 0.10 | + | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Ferrimonas spp. | 27 | 0.10 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Bacillus spp. | 24 | 0.09 | + | aerobe | rod |

| UWB | 22 | 0.08 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 22 | 0.08 | - | anaerobe | rod |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | 20 | 0.07 | - | aerobe | rod |

| UWB | 17 | 0.06 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Riemerella spp. | 15 | 0.05 | - | aerobe | rod |

| UWB | 14 | 0.05 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Stenotrophomonas spp. | 14 | 0.05 | - | aerobe | rod |

| Shewanella spp. | 11 | 0.04 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Eubacterium spp. | 10 | 0.04 | + | anaerobe | rod |

This table provides the identified genus of the bacteria found using pyrosequencing (PRAPS) in the P sample, the number of sequences corresponding to this genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the shape of the genus. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences. * The asterisk identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the P pool. Bacteria that were cultured and were not found using PRAPS include Acinetobacter, Leclercia, Morganella, and Pseudomonas. The % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

FRACS

The use of Full Ribosomal Amplification, Cloning and Sanger Sequencing (FRACS) has been utilized for at least 18 years to evaluate the biodiversity of environmental samples [70-72]. This method has also been used to evaluate the microbial diversity of environmental biofilms [73] and at least one study utilized this approach to evaluate the microbial diversity of diabetic foot ulcers [74].

When using FRACS for 200 random clones from each library and following vector screening and quality scoring, we found that between 179 and 194 sequences from each library could be analyzed. The break down of genotypes demonstrated similar trends (Table 5) as were observed using PRAPS. Strict anaerobes, cocci, and gram positives were scarce in the V group (Table 6). Facultative and strict anaerobic gram positive cocci were most prevalent in the D group (Table 7), and strictly anaerobic gram positive dominated the P group (Table 8). In V samples the predominant bacterial genus, identified by FRACS, were overwhelmingly Pseudomonas spp. (including P. aeruginosa and P. fluorescens) followed by Enterobacter spp. (including E. cloacae), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Proteus spp., and Staphyloccoccus aureus (Table 6). In the D sample the predominant species was overwhelmingly Staphylococcus aureus followed by Anaerococcus lactolyticus, Anaerococcus vaginalis, Bacterioides fragilis, Finegoldia magna, and Morganella morganii (Table 7). Finally, predominant bacteria in the P sample were Peptoniphilus ivorii, Anerococcus spp., Streptococcus dysgalactiae, and Peptoniphilus spp. (Table 8).

Table 5.

Overview of the phenotypes of microbial populations as determined using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS).

| Category | Pressure Ulcer seq | Pressure Ulcer sp. | Diabetic Foot Ulcer seq. | Diabetic Foot Ulcer sp. | Venous Leg Ulcer seq | Venous Leg Ulcer sp. |

| aerobes | 20 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 114 | 7 |

| facultative anaerobes | 21 | 8 | 102 | 15 | 69 | 15 |

| anaerobes | 143 | 13 | 75 | 15 | 7 | 3 |

| Cocci | 136 | 11 | 137 | 14 | 14 | 6 |

| Rods | 48 | 15 | 41 | 17 | 176 | 19 |

| gram positive | 153 | 14 | 136 | 15 | 21 | 9 |

| gram negative | 31 | 12 | 42 | 17 | 169 | 16 |

| UWB | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

The data from Sanger sequencing (FRACS) is broken down into the number of sequences (seq) from each sample (P, D, and V) that were related to a given characteristic (anaerobe, gram positive etc). Also shown are the number of genera that were associated with each of the phenotypic categories. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences.

Table 6.

Results obtained for venous leg ulcer sample (V) using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS).

| Genus species | Number seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Pseudomonas sp*. | 45 | 23.20 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa.* | 30 | 15.46 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens* | 20 | 10.31 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Enterobacter spp. | 19 | 9.79 | - | facultative | rod |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. | 14 | 7.22 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 10 | 5.15 | - | facultative | rod |

| Staphylococcus aureus* | 7 | 3.61 | + | Facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Proteus vulgaris | 6 | 3.09 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Shewanella algae | 6 | 3.09 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Proteus mirabilis. | 6 | 3.09 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| UWB | 4 | 2.06 | unk | unk | unk |

| Clostridium perfringens | 4 | 2.06 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Klebsiella spp.* | 4 | 2.06 | - | facultative | rod |

| Serratia marcescens * | 3 | 1.55 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Clostridium spp. | 2 | 1.03 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Helcococcus kunzii | 2 | 1.03 | + | facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Staphylococcus spp.* | 2 | 1.03 | + | Facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 | 1.03 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Bacillus fusiformis. | 1 | 0.52 | + | aerobic | rod |

| Enterococcus avium* | 1 | 0.52 | + | Facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Enterococcus faecalis* | 1 | 0.52 | + | Facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Peptococcus spp. | 1 | 0.52 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 1 | 0.52 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Salmonella spp. | 1 | 0.52 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 0.52 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Shigella spp. | 1 | 0.52 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

This table provides the identified genera of the bacteria found using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS) in the V sample, the number of sequences corresponding to this genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the shape of the genus. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences. The asterisk * identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the V pool. Bacteria that were cultured and were not found using FRACSS include Acinetobacter, Citrobacter, and Corynebacterium. The % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

Table 7.

Results obtained for diabetic foot ulcer sample (D) using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS).

| Genus species | Seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Staphylococcus aureus * | 70 | 39.33 | + | facultative | Cocci |

| Anaerococcus lactolyticus | 16 | 8.99 | + | anaerobic | Cocci |

| Anaerococcus vaginalis | 15 | 8.43 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Bacterioides fragilis | 7 | 3.93 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Finegoldia magna | 6 | 3.37 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Morganella morganii | 5 | 2.81 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Enterococcus faecalis* | 5 | 2.81 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Peptoniphilus harei | 5 | 2.81 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Clostridium novyi | 4 | 2.25 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Veillonella atypica | 4 | 2.25 | - | anaerobic | cocci |

| Abiotrophia para-adiacens | 4 | 2.25 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Veillonella parvula | 4 | 2.25 | - | anaerobic | cocci |

| Citrobacter murliniae * | 3 | 1.69 | - | facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Haemophilus spp. | 3 | 1.69 | - | facultative | rod |

| Clostridium spp. | 3 | 1.69 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Haemophilus segnis | 3 | 1.69 | - | faculative | rod |

| Enterococcus avium* | 3 | 1.69 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Proteus spp.* | 2 | 1.12 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 | 1.12 | - | facultative | rod |

| Dialister spp. | 2 | 1.12 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus | 2 | 1.12 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | 0.56 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Klebsiella oxytoca* | 1 | 0.56 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 0.56 | - | facultative | rod |

| Pseudoalteromonas spp. | 1 | 0.56 | - | facultative | rod |

| Porphyromonas levii | 1 | 0.56 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Delftia acidovorans | 1 | 0.56 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Dialister invisus | 1 | 0.56 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis* | 1 | 0.56 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Staphylococcus spp.* | 1 | 0.56 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Granulicatella spp. | 1 | 0.56 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

This table provides the identified genera of the bacteria found using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS) in the D sample, the number of sequences corresponding to this genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the shape of the genus. The asterisk * identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the D pool. Bacteria that were cultured and were not found using FRACSS include Pseudomonas, Serratia, and Streptococcus. The % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

Table 8.

Results obtained for the pressure ulcer sample (P) using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS).

| Genus species | Seq | % | Gram | Aerotolerance | Shape |

| Peptoniphilus ivorii | 51 | 27.42 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Anaerococcus lactolyticus | 20 | 10.75 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Anaerococcus vaginalis | 16 | 8.60 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae* | 14 | 7.53 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Peptoniphilus harei | 14 | 7.53 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Peptococcus niger | 12 | 6.45 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Serratia marcescens | 12 | 6.45 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Finegoldia magna | 10 | 5.38 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Peptoniphilus indolicus | 7 | 3.76 | + | anaerobic | cocci |

| Clostridium hathewayi | 4 | 2.15 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Prevotella buccalis | 3 | 1.61 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa* | 3 | 1.61 | - | aerobic | rod |

| UWB | 2 | 1.08 | Unk | unk | unk |

| Dialister invisus | 2 | 1.08 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Dialister spp. | 2 | 1.08 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Delftia acidovorans | 2 | 1.08 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens* | 2 | 1.08 | - | aerobic | rod |

| Helcococcus kunzii | 1 | 0.54 | + | facultative anaerobe | cocci |

| Enterococcus faecalis* | 1 | 0.54 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis* | 1 | 0.54 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Streptococcus pyogenes* | 1 | 0.54 | + | facultative | cocci |

| Clostridium perfringens | 1 | 0.54 | + | anaerobic | rod |

| Klebsiella granulomatis | 1 | 0.54 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | 0.54 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Proteus vulgaris* | 1 | 0.54 | - | Facultative anaerobe | rod |

| Porphyromonas uenonis | 1 | 0.54 | - | anaerobic | rod |

| Pseudomonas spp.* | 1 | 0.54 | - | aerobic | rod |

This table provides the identified genera of the bacteria found using shotgun Sanger sequencing (FRACS) in the P sample, the number of sequences corresponding to the given genus, the known gram staining properties, the aerotolerance (anaerobic, anaerobic, or facultative anaerobic) nature of the genus, and the shape of the genus. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences. The asterisk * identifies bacteria previously cultured from a single culture result from each subject's medical record from subjects in the P pool. Bacteria that were cultured and were not found using FRACSS include Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, Leclercia and Morganella. The % represents the percentage of the total sequences analyzed within the sample.

PRADS

The use of a Partial Ribosomal Amplification, DGGE, and Sanger sequencing (PRADS) has been utilized extensively to study microbial diversity [75-80]. This approach has also been used extensively to study the microbial diversity of biofilms [81-84] and has even been used to study clinical biofilms [85]. The primary use of DGGE by itself is to provide an indication of diversity. The number of bands seen in a gel, in many cases, can provide a relative measure of the number of different bacteria present. It is understood that each of the bands seen in a DGGE gel can represent multiple species and even the same species can be represented by multiple bands as we observed in the current study (data not shown).

By excising the predominant bands from each sample, cloning them into a vector, and sequencing them, the identity of the bacteria from each band are identified. In the V sample the primary bacteria were Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, and Proteus spp. (Table 9). This is similar to the results seen using both FRACSS and PRAPS. In the D sample, PRADS identified Pseudomonas, Haemophilus, Citrobacter, and Stenotrophomonas as the predominant species (Table 9). In the P sample the primary species identified was Serratia, Dialister, and Peptococcus spp. (Table 9).

Table 9.

Results obtained for each of the samples using DGGE band extraction and sequencing (PRADS).

| V seq | V genus | D seq | D genus | P seq | P genus |

| 18 | Enterobacter spp.* | 13 | Pseudomonas spp.* | 34 | Serratia spp. |

| 17 | Pseudomonas spp.* | 12 | Haemophilus spp. | 13 | Dialister spp. |

| 4 | Proteus spp. | 11 | Citrobacter spp.* | 10 | Peptococcus spp. |

| 2 | Klebsiella spp.* | 11 | Stenotrophomonas spp. | 3 | Pseudomonas spp.* |

| 2 | Pectobacterium spp. | 10 | Morganella spp. | 2 | Citrobacter spp. |

| 2 | Erwinia spp. | 10 | Staphylococcus spp. | 2 | Morganella spp. |

| 1 | Serratia spp.* | 5 | Acinetobacter spp. | 2 | Proteus spp.* |

| 1 | UWB | 5 | Acinetobacter spp. | 1 | Haemophilus spp. |

| 1 | Haemophilus spp. | 4 | Morganella spp. | 1 | Klebsiella spp. |

| 4 | Proteus spp.* | 1 | Leminorella spp. | ||

| 3 | Delftia spp. | 1 | Pectobacterium spp. | ||

| 3 | Obesumbacterium spp. | 1 | Peptoniphilus spp. | ||

| 2 | Dialister spp. | 1 | Prevotella spp. | ||

| 2 | Mannheimia spp. | 1 | UWB | ||

| 1 | Comamonas spp. | ||||

| 1 | Grimontia spp. | ||||

| 1 | Klebsiella spp.* | ||||

| 1 | Macrococcus spp. | ||||

| 1 | Methylophaga spp. | ||||

| 1 | Pantoea spp. | ||||

| 1 | Pectobacterium spp. | ||||

| 1 | Rahnella spp. | ||||

| 1 | Serratia spp.* | ||||

| 1 | Streptococcus spp.* | ||||

| 1 | UWB |

This table provides the identified genus of the bacteria found in each of the samples as determined by DGGE band excision, cloning and sequencing (PRADS). The number of sequences corresponding to this genus is provided. The physiological aspects of these isolates are described elsewhere in most cases. UWB refers to unknown wound bacteria or sequences without significant similarity to database sequences.

Culturing

A review of the literature identifies Staphylococcus spp. as the predominant organisms associated with wounds based upon culturing [86-88]. As discussed in the introduction, this is primarily due to the ability of this bacterium to be propagated in culture media under typical laboratory conditions. Pseudomonas spp., another easy to culture bacteria is also frequently isolated from chronic wounds using culture methods [89,90]. Other species that have been most consistently identified in association with chronic wounds include E. coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, Enterococcus. and Proteus spp. [25,58,86,88,90-95]. One notable commonality of the above organisms is the ease with which they can be cultured in standard laboratory growth media under aerobic conditions. These claims are upheld by the data presented here, as all of the isolates identified using the clinical cultures are relatively easy to propogate under aerobic conditions in standard laboratory media (Table 10).

Table 10.

Bacteria cultured during standard of care from three wound groups.

| Subjects | V group | Subjects | D group | Subjects | P group |

| 4 | Enterococcus | 2 | Citrobacter | 4 | Staphylococcus |

| 3 | Staphylococcus | 2 | Enterococcus | 2 | Streptococcus |

| 2 | Enterobacter | 2 | Klebsiella | 2 | Enterococcus |

| 2 | Pseudomonas | 2 | Serratia | 1 | Escherichia |

| 1 | Klebsiella | 2 | Staphylococcus | 1 | Leclercia |

| 1 | Serratia | 2 | Streptococcus | 1 | Proteus |

| 1 | Citrobacter | 1 | Proteus | 1 | Pseudomonas |

| 1 | Acinetobacter | 1 | Pseudomonas | 1 | Acinetobacter |

| 1 | Escherichia | 1 | Enterobacter |

Subject's medical records were examined, and the positive culture nearest to the date of sample collection for molecular analysis was considered. All thirty (30) subjects except for one (1) subject in the P group had a culture recorded in their medical records. The number of subjects within each group to culture positive for a bacterial genus is listed next to the genus. Many of the subjects were cultured for both aerobes and anaerobes, but the clinical laboratories reported no obligate anaerobes.

Culture results for 29 of the 30 subjects were found by auditing the subjects' past and current longitudinal medical records. The bacteria isolated are indicated for comparative purposes in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 6, 7, 8 and reported fully in Table 10. Cultures were positive for some bacteria that were not identified using PRAPS, FRACS, or PRADS. In the V group, Citrobacter was identified via culture and was not discovered with molecular methods. In the D group, all bacteria that were cultured were identified using molecular methods. In the P group, Acinetobacter and Escherichia spp. were cultured but not identified via molecular methods. As noted in the methods, the samples used for culturing were not necessarily collected in parallel with the samples collected for molecular analyses. Continuous longitudinal attempts to culture anaerobic bacteria had also been made and were unsuccessful for any of these patients. This highlights the problems with laboratory culture methods especially with the P type chronic wound, which is predicted to be primarily anaerobic using each of the molecular methods.

Comparison to normal flora

The microbial flora of normal skin is also considered complex. A bacterial diversity study of normal skin flora from 6 healthy subjects was performed using molecular methods [96]. It was found that there were hundreds of bacterial species among the individuals. The conclusions of this study indicated that normal flora of skin is highly diverse and only a few bacteria are common among the individuals. These included Propionibacteria, Corynebacteria, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus spp. [96]. These results were largely corroborated by a previous study which collected and analyzed swabs from the forehead of 5 individuals. This study also found Staphylococcus and Propionibacteria spp. as well as high prevalence of methylophilus spp. [97]. Few other studies were found evaluating normal skin microflora suggesting that more extensive studies of healthy skin microflora are also needed. The primary bacteria that occur on healthy skin also correlate to the primary bacteria cultured from wound biofilms. Future studies are needed to evaluate the normal flora and chronic wound biofilm flora from the same patients.

Anaerobes in pathogenic biofilms

In relation to anaerobes, the literature is now beginning to show their importance in chronic wound pathogenic biofilms. Even though such wounds are typically exposed to air [88] anaerobes may be most prevelant physiological type for a given wound or a given wound type as shown in this study. Many of these newer studies show the importance of anaerobes such as Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Finegoldia and Peptoniphilus spp. [88,89,91,93,94,98], which were also seen as important in the current survey. However, as noted previously, only a few studies have looked at the populations of bacteria in various wound types. Bowler et al [88] evaluated venous leg ulcers using cultural isolation techniques that included special considerations for the propogation of anaerobes. They found that anaerobes represented 49% of the total microbial composition in such wounds. This does not agree with our analyses of the V type ulcer, which showed only 1.6% of sequences were matched to anaerobes. However, almost 30% of the sequences from D and 62% of sequences from P wound types were matched to anaerobes. An interesting observation is that the differences in the functional diversity of the pathogenic biofilms may suggest important differences in the physiology of these three types of wounds. As indicated previously, the pathophysiology of a wound type may select for certain physiological or functional populations within the associated pathogenic biofilm. Thus, the bacterial populations which are prevelant might in turn suggest differences in management of the individual CWPB are necessary.

As has been demonstrated in the laboratory [59,99], anaerobes may cope with the toxic effects of oxygen by interacting with aerobic or facultative anaerobic bacterial populations in a symbiotic manner as part of a process known as coaggregation. Aerobic species may consume oxygen and create localized environments, allowing the obligate anaerobes to gain advantage when in close proximity. The Lewandowski lab has also shown that oxygen only penetrates microns into the surface of biofilms suggesting that internal regions may support only anaerobes and facultative anaerobes [100]. Such synergistic interactions and advantages of biofilm phenotype have been shown for specific aerobes and anaerobes. Using animal models it has also been shown that mixtures of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria have been shown to produce disease states which cannot be reproduced by the individual species alone [61,101,105]. These findings suggest a complexity to the host-pathogen interaction that adds a new dimension to Koch's postulates. These finding also dramatically highlight the failings of culture methods to identify major populations of importance within each of the wound types.

Conclusion

The primary contrasts we see in these data are the differences found in bacterial populations within wound types using culture (Table 10) and molecular analyses (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Here we show that culturing failed to identify major contributing populations, especially strict anaerobes, within the given wound types. Standard culturing techniques are inherently biased as they only examine only the 1% of all microorganisms which are able to grow fairly rapidly in pure culture. Culturing also requires several days before the culturable bacteria can be identified whereas molecular methods such as PCR can typically be completed within several hours. In addition, certain of the isolates we have shown are primary populations within a wound type, may never be cultured in the laboratory due to reduced metabolic activity, obligate cooperation with other bacteria, requirements for specialized nutrients, or growth in specific environmental conditions [106]. Molecular methods unlike culture methods also have more potential to provide quantitative data. Arguably, we have shown that molecular methods will allow populations residing within biofilms to be more fully characterized. The continued development of molecular methods may lead to vastly improved tools for diagnostics that will identify and provide quantification of the diverse species potentially present in chronic wounds thereby allowing physicians to better tailor their treatment to each patient's unique pathogenic biofilm populations. This dramatically highlights the need to move microbiological analyses of chronic wound pathogenic biofilms toward molecular approaches.

If clinicians can gain a better understanding of the wound's microbiota, it will give us a greater understanding of the wound's ecology and will allow us to better manage the wound. It is important to consider the bacterial populations within pathogenic biofilms for many reasons. These reasons typically relate to the fact that the higher bacterial population diversity within a pathogenic biofilm provides the bacterial community as a whole with an enhanced ability to persist and thrive in a variety of antagonistic situations, even in spite of combined host and medicinal attack [107]. The current study has shown that a wide variety of bacteria with different physiological and phenotypic preferences are common as part of pathogenic biofilm communities in chronic wounds. Additionally, we can see that different types of wounds may have different bacterial populations that are prevalent. Thus, the CWPB in one wound or wound type may indicate a therapy that is different than that indicated in another wound or wound type. As noted previously, such conclusions are beyond the scope of this survey but are suggested by the results. These conclusions also provide direction for future research. The use of traditional culture techniques are widely used, but we and others have consistantly demonstrate that they are not likely to be the best way to elucidate the bacterial populations within CWPB.

Methods

Biofilms from a total of 30 chronic wound patients were included in this survey study. A total of 30 chronic wounds were sampled and grouped into one of three categories of wounds: venous leg ulcers (V), diabetic foot ulcers (D), or pressure ulcers (P). To identify the microbial populations that occur in these types of wounds and to gain a preliminary understanding of their relative importance, we took advantage of three powerful molecular approaches that included PRADS [108], FRACS [109], and PRADS [110]. These techniques allowed the bacterial diversity that occurs within these CWPB types to be evaluated.

Protocol for subject enrollment, DNA extraction, and Sample Preparation

Under the guidance of IBR protocols, chronic wounds of 30 subjects treated at the Southwest Regional Wound Care Center (Lubbock, Texas) were debrided as per standard of care; the debridement samples were collected with sterile tools into sterile collection tubes and frozen until processing for DNA extraction. Samples from 10 subjects with venous leg ulcers, 10 subjects with diabetic foot ulcers, and 10 subjects with pressure (decubitus) ulcers were included in this study. Debridement samples (300 mg ± 150 mg) were collected into Lysing Matrix E tubes from the FastDNA® SPIN for Soil Kit from MP Biomedicals LLC (Solon, OH). The tubes were frozen at -70°C until DNA extraction could be performed. When DNA extraction was performed, the samples were removed from the freezer and allowed to thaw at room temperature. Subsequently, the DNA extraction protocol for the kit was followed with the exception that human debridement samples were used in place of soil samples. The extracted sample DNA was stored at -70°C. After measuring the relative concentration of bacterial DNA present based upon 16s quantitative PCR using 16S Universal Eubacterial primers 530F (5'-GTG CCA GCM GCN GCG G) and 1100R (5'-GGG TTN CGN TCG TTG), the 10 samples from each of the three wound groups were pooled at equal bacterial DNA ratios to create three pools of DNA, each representing a major category of chronic wound.

Partial ribosomal amplification and pyrosequencing (PRAPS)

The modified 16S Eubacterial primers 530F and 1100R were used for amplifying the 600 bp region of 16S rRNA genes. The primer pair used for 454 Amplicon Sequencing was designed with special Fusion Primers at the 5' end of each primer as follows: 530F-A (5'-GCC TCC CTC GCG CCA TCA GGT GCC AGC MGC NGC GG) and 1100R-B (5'-GCC TTG CCA GCC CGC TCA GGG GTT NCG NTC GTT G). All wound DNA samples were diluted to 100 ng/μl. A 100 ng aliquot of sample DNA was used for a 50 μl PCR reaction. HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (QIAGEN, CA, USA) was used for PCR under the following conditions: 94°C for 3 minutes followed by 32 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds; 60°C for 40 seconds and 72°C for 1 minute; and a final elongation step at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified using the PSI Ψ Clone PCR 96 Kit (Princeton Separations Inc, Freehold, NJ). Following PCR amplification, samples were normalized in concentration and sent on dry ice to the Medical Biofilm Research Institute [111] for pyrosequencing using genome sequencer FLX system's standard amplicon sequencing protocols (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland).

Full ribosomal amplification, cloning and Sanger sequencing (FRACS)

The Eubacterial 16S primers 27F (5'-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG) and 1525R (5'-AAG GAG GTG WTC CAR CC) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). These primers amplify roughly 1500 bp spanning almost the entire 16S gene. A total of 100 ng of sample DNA was used for each 50 μl PCR reaction. HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used for PCR using the following conditions: 94°C for 3 minutes followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 40 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes. A final elongation step at 72°C for 10 minutes was also included. The amplified fragments were subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and transformed into a competent E. coli K12 strain. Following blue/white screening using standard methods, 200 clones from each library were isolated and subcultured. The plasmid DNA was extracted by using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Bidirectional sequencing using T7 and SP6 primers was performed by Agencourt Technologies (Beverly, MA).

Partial Ribosomal Amplification, DGGE, and Sanger sequencing (PRADS)

The 16S Eubacterial primers 1070F (5'-ATG GCT GTC GTC AGC T) and 1492R+GC (5'-GCC GCC TGC AGC CCG CGC CCC CCG TGC CCC CGC CCC GCC GCC GGC CCG GGC GCC TTA CCC TTG TTA CGA CTT) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). These primers produced an approximately 450 bp 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) amplicon with a GC clamp to be analyzed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). PCR reactions (50 μl of sample DNA) were performed using 2× PCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI). Each reaction mixture consisted of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 μM of both the 1070F and 1492R+GC primers, 0.025 U/μl Taq DNA polymerase, and 100 ng template DNA.

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) was performed on the 16S amplicons described above using the DCode™ DGGE system (Bio-rad). A 40%–70% denaturing gradient was optimal for separation of the approximately 450 bp 16S amplicons, where 7 M urea and 40% formamide is defined as 100%. Gels also contained an 8%–12% acrylamide gradient with a 12% native stacking gel. Different volumes of each sample were loaded for optimal visualization of bands with varying intensities. The gel was run at 60 V for 20 hours and was then stained with SYBR Gold® (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and visualized with a FluorChem™ 8800 fluorescence imager (Alpha Innotech Inc. San Leandro, CA). Nineteen predominant bands that could be visualized by eye were excised using a sterile, disposable scalpel and placed in 20 μl TE buffer (Figure 1). This included 4 bands from the venous leg ulcer group (group V), 8 from the diabetic foot ulcer group (group D), and 6 from the pressure ulcer group (group P).

The TOPO TA Cloning® kit (Invitrogen Inc. Carlsbad, CA) was used to clone the DNA from the excised DGGE bands (pCR® 2.1-TOPO® vector and One Shot Chemically Competent E. coli cells). The maximum amount of DNA (4 μl diffused DNA in TE buffer) was used in each of the cloning reactions following the manufacture's instructions. Twelve clones per band were selected and grown overnight in 250 μl LB broth containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin in 96 well plates. The same 50 μl PCR reaction was prepared as described above using the M13F and M13R primer set instead of 1070F and 1492R+GC and 5 μl of the overnight culture was added to each 50 μl PCR reaction as the template DNA. The initial 96°C denaturing step was sufficient to rupture the E. coli cells, releasing its DNA as the starting template. These PCR products were then sequenced by the University of Washington's High-Throughput Genomics Unit (Seattle, WA).

Culturing

Samples were not collected in parallel with samples collected for the PRAPS, FRACS, or PRADS; but culture results were instead collected retrospectively from the subjects' medical records. All samples were collected under IBR protocols. This information is provided as a contrast to the type of data normally collected from wounds. Results were examined from each subject's medical record. The culture results were collected usually within a week of the samples that was collected for the PRAPS, FRACS, and PRADS analyses. Sharp debridement from the subject's wound was placed in thioglycolate broth with indicator (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) and incubated at 35°C for up to 24 hours with the lid tightly closed before being transferred to a CLIA certified microbiology laboratory for thorough aerobic and anaerobic culture analyses. Bacteria were identified using Gram stains, non-selective and selective/differential media, and biochemical tests.

Bioinformatics

Assembly, including vector scanning, quality analysis, and consensus calling, of sequencing data was performed using Seq-Man Pro assembler (DNAstar Madison, WI). Sequences were assembled using SeqMan Pro Assembler at 96% similarity, match size of 25, match spacing of 50, minimum sequence length of 100, 0.0 and 0.7 gap and gap extension penalties, and a minimum mismatch of 8 at end bases. Multiple alignments were performed with MegAlign (DNAstar Madison, WI). BLAST analyses were performed using WND.BLAST [112] and a custom 16S ribosomal database derived from RDPII version 9 [113,114]. The database was first parsed with a custom script to provide genus and species names as hit definitions following BLAST analyses. For FRACS E-values < 10E-100 were considered acceptable for determining genus, while hits of E = 0.0 and associated full alignments > 1400 bp were considered acceptable for determining genus and species. For PRADS and PRAPS all species determinations are considered putative, E-values of 10–100 are considered acceptable for determining genus, while E-values better than 10–140, along with full input sequence alignments, and genus/species agreement of all similarly scoring top hits were required to list a putative species.

Authors' contributions

SED was responsible for primary conception of the methods, project management, data interpretation, and development and approval of the final version of the manuscript. YS helped develop methods, performed most of the laboratory studies, and data compilation. PS and GJ performed DGGE and all associated writing and data interpretations. DR helped with interpretation of results, compiling data, and writing of early drafts of the manuscript. RW was vital in developing the project concepts, interpretation of results and approval of final draft of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

USDA disclaimer: The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the United States Department of Agriculture. Dr. Dowd's work on this project was performed as part of a USDA trust agreement for development of next generation sequencing technologies for the study of host-pathogen interactions and diversity.

Contributor Information

Scot E Dowd, Email: sdowd@lbk.ars.usda.gov.

Yan Sun, Email: s_yan_99@yahoo.com.

Patrick R Secor, Email: psecor@erc.montana.edu.

Daniel D Rhoads, Email: danrhoads@gmail.com.

Benjamin M Wolcott, Email: glorfindelvsp@yahoo.com.

Garth A James, Email: GJames@erc.montana.edu.

Randall D Wolcott, Email: randy@randallwolcott.com.

References

- Nickel JC, Heaton J, Morales A, Costerton JW. Bacterial biofilm in persistent penile prosthesis-associated infection. J Urol. 1986;135:586–588. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buret A, Ward KH, Olson ME, Costerton JW. An in vivo model to study the pathobiology of infectious biofilms on biomaterial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1991;25:865–874. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820250706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SP, Pulido JS, Miller D, Ellis B, Alfonso E, Scott M, Costerton JW. Biofilm and scleral buckle-associated infections. A mechanism for persistence. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:933–938. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward KH, Olson ME, Lam K, Costerton JW. Mechanism of persistent infection associated with peritoneal implants. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:406–413. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-6-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005:7–11. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Naber K, Hacker J, Ziebuhr W. Detection of the icaADBC gene cluster and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from catheter-related urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:570–575. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(02)00101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump JA, Collignon PJ. Intravascular catheter-associated infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s100960050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaisrie SC, Malekzadeh S, Biedlingmaier JF. In vivo analysis of bacterial biofilm formation on facial plastic bioimplants. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1733–1738. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199811000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando E, Monden K, Mitsuhata R, Kariyama R, Kumon H. Biofilm formation among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with urinary tract infection. Acta Med Okayama. 2004;58:207–214. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C, Kondella K, Bernschneider T, Heppert V, Wentzensen A, Hansch GM. Post-traumatic osteomyelitis: analysis of inflammatory cells recruited into the site of infection. Shock. 2003;20:503–510. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000093542.78705.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan P, Nair MK, Annamalai T, Venkitanarayanan KS. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bovine mastitis isolates of Staphylococcus aureus for biofilm formation. Vet Microbiol. 2003;92:179–185. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel JC, Emtage J, Costerton JW. Ultrastructural microbial ecology of infection-induced urinary stones. J Urol. 1985;133:622–627. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel JC, Costerton JW, McLean RJ, Olson M. Bacterial biofilms: influence on the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33 Suppl A:31–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.suppl_a.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW. Cystic fibrosis pathogenesis and the role of biofilms in persistent infection. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:50–52. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME, Gilmore MS, Engelbert M. Immunology of Staphylococcal biofilm infections in the eye: new tools to study biofilm endophthalmitis. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:405–413. doi: 10.1089/10445490260099692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percival SL, Bowler PG, Dolman J. Antimicrobial activity of silver-containing dressings on wound microorganisms using an in vitro biofilm model. Int Wound J. 2007;4:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TJ. Infection following soft tissue injury: its role in wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:124–128. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32801a3e7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo Q, Vickery K, Deva AK. Pr21 role of bacterial biofilms in chronic wounds. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77 Suppl 1:A66. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04127_20.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks A. Prontosan wound irrigation and gel: management of chronic wounds. Br J Nurs. 2006;15:1222–1228. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.22.22559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SC, Martinez L, Kirsner R. The diabetic foot: the importance of biofilms and wound bed preparation. Curr Diab Rep. 2006;6:439–445. doi: 10.1007/s11892-006-0076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saye DE. Recurring and antimicrobial-resistant infections:considering the potential role of biofilms in clinical practice. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53:46–8, 50, 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, Pulcini ED, Secor P, Sestrich J, Costerton JW, Stewart PS. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjodsbol K, Christensen JJ, Karlsmark T, Jorgensen B, Klein BM, Krogfelt KA. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. Int Wound J. 2006;3:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2006.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton J. Managing leg and foot ulcers: the role of Kerraboot. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9:S26–S30. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2004.9.Sup3.15943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer SM, Bauer RJ, Velazquez OC. Angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, and induction of healing in chronic wounds. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2005;39:293–306. doi: 10.1177/153857440503900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko DA, Rowley-Jones D. Stress ulceration. Br J Hosp Med. 1985;34:186–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M, Cullum N, Nelson EA, Petticrew M, Sheldon T, Torgerson D. Systematic reviews of wound care management: (2). Dressings and topical agents used in the healing of chronic wounds. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M, Cullum N, Sheldon T. The debridement of chronic wounds: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:iii–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem H, Kirsner RS, Falanga V. Protocol for the successful treatment of venous ulcers. Am J Surg. 2004;188:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CS. Venous ulcers. Am J Surg. 1994;167:37S–40S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Chronic wounds. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:689–700. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Land L. Topical negative pressure for treating chronic wounds: a systematic review. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:238–242. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2001.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga V. The chronic wound: impaired healing and solutions in the context of wound bed preparation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;32:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga V. Wound healing and chronic wounds. J Cutan Med Surg. 1998;3 Suppl 1:S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Harding KG. Diabetic foot ulcers. Lancet. 2003;361:1545–1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckrich K, Aronovitch SA. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers: a comparison of costs in medical vs. surgical patients. Nurs Econ. 1999;17:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Kanzaki H, Tada J, Arata J. Staphylococcus aureus infection on cut wounds in the mouse skin: experimental staphylococcal botryomycosis. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;11:234–238. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(95)00448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R, Harding KG. Bacteria and wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:91–96. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez JC, Peral MC, Rachid M, Santana M, Perdigon G. Interference of Lactobacillus plantarum with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in infected burns: the potential use of probiotics in wound treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11:472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Cutting K, Kingsley A. Topical antimicrobials in the control of wound bioburden. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006;52:26–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. Wound care: Askina Transorbent and Askina Biofilm Transparent. Br J Nurs. 2000;9:304–307. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2000.9.5.6367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki AB. Evaluating and managing open skin wounds: colonization versus infection. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13:382–397. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R. Burn wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:403–434. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri N, Gupta V, Joshi RM. Aerobic bacterial isolates from burn wound infections and their antibiograms--a five-year study. Burns. 2004;30:241–243. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour AD, Shankowsky HA, Swanson T, Lee J, Tredget EE. The impact of nosocomially-acquired resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a burn unit. J Trauma. 2007;63:164–171. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000240175.18189.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi F, Onder G, Russo A, Bernabei R. Pressure ulcer and mortality in frail elderly people living in community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;44 Suppl 1:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi F, Sgadari A, Bernabei R. Pressure ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:422. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, Guadagnoli E, Meara E, Platt R. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:196–203. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LE, Cook G, Costerton JW. Biofilm on ventriculo-peritoneal shunt tubing as a cause of treatment failure in coccidioidal meningitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:376–379. doi: 10.3201/eid0804.010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SD, Newton K, Blough D, McCulloch DK, Sandhu N, Wagner EH. Patient-level estimates of the cost of complications in diabetes in a managed-care population. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;16:285–295. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199916030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SD, Newton K, Blough D, McCulloch DK, Sandhu N, Reiber GE, Wagner EH. Incidence, outcomes, and cost of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:382–387. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Stensel V, Forsberg RC, Davignon DR, Smith DG. A prospective study of risk factors for diabetic foot ulcer. The Seattle Diabetic Foot Study. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1036–1042. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Smith DG, Davignon D. Increased mortality associated with diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 1996;13:967–972. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199611)13:11<967::AID-DIA266>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuckin M, Goldman R, Bolton L, Salcido R. The clinical relevance of microbiology in acute and chronic wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2003;16:12–23. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson PD. Immunology, microbiology, and the recalcitrant wound. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2000;46:77S–82S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CE, Hill KE, Wilson MJ, Stephens P, Hill CM, Harding KG, Thomas DW. Use of 16S ribosomal DNA PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis for analysis of the microfloras of healing and nonhealing chronic venous leg ulcers. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3549–3557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3549-3557.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Allison C, Schilling KM. Effect of oxygen, inoculum composition and flow rate on development of mixed-culture oral biofilms. Microbiology. 1996;142 ( Pt 3):623–629. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-3-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore B, Youldon J, Thrasher DR, Vance I. Effects of nitrate treatment on a mixed species, oil field microbial biofilm. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:454–462. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrand D, McBride BC. Exological relationships of bacteria involved in a simple, mixed anaerobic infection. Infect Immun. 1980;27:44–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.44-50.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley P, Wilson S, Hall-Stoodley L, Boyle JD, Lappin-Scott HM, Costerton JW. Growth and detachment of cell clusters from mature mixed-species biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5608–5613. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5608-5613.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RA, Rodriguez-Brito B, Wegley L, Haynes M, Breitbart M, Peterson DM, Saar MO, Alexander S, Alexander EC, Jr., Rohwer F. Using pyrosequencing to shed light on deep mine microbial ecology. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna RA, Fasciano LR, Jones SC, Boyanton BL, Ton TT, Jr., Versalovic J. DNA Pyrosequencing-Based Bacterial Pathogen Identification in a Pediatric Hospital Setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2007 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00630-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasson J, Olofsson M, Monstein HJ. Classification, identification and subtyping of bacteria based on pyrosequencing and signature matching of 16s rDNA fragments. 2002. APMIS. 2007;115:668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharizadeh B, Kalantari M, Garcia CA, Johansson B, Nyren P. Typing of human papillomavirus by pyrosequencing. Lab Invest. 2001;81:673–679. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trama JP, Mordechai E, Adelson ME. Detection and identification of Candida species associated with Candida vaginitis by real-time PCR and pyrosequencing. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JA, Butchko AR, Durso MB. Use of pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA fragments to differentiate between bacteria responsible for neonatal sepsis. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s1525-1578(10)60015-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins KL, Arnold C, Threlfall EJ. Rapid detection of gyrA and parC mutations in quinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica using Pyrosequencing technology. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;68:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossler D, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Lin C, McGill TJ, Wisotzkey JD, Jurtshuk P, Jr., Fox GE. Phylogenetic diversity in the genus Bacillus as seen by 16S rRNA sequencing studies. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:266–269. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli K, Bosshard F, Werlen C, Lais P, Siegrist H, Zehnder AJ, Van M., Jr. Microbial composition and structure of a rotating biological contactor biofilm treating ammonium-rich wastewater without organic carbon. Microb Ecol. 2003;45:419–432. doi: 10.1007/s00248-002-2037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabereiter-Gurtner C, Saiz-Jimenez C, Pinar G, Lubitz W, Rolleke S. Phylogenetic 16S rRNA analysis reveals the presence of complex and partly unknown bacterial communities in Tito Bustillo cave, Spain, and on its Palaeolithic paintings. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:392–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser C, Stockigt C, Raasch C, Wingender J, Timmis KN, Wenderoth DF, Flemming HC, Liesegang H, Schmitz RA, Jaeger KE, Streit WR. Metagenome survey of biofilms in drinking-water networks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7298–7309. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7298-7309.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redkar R, Kalns J, Butler W, Krock L, McCleskey F, Salmen A, Jr PE, DelVecchio V. Identification of bacteria from a non-healing diabetic foot wound by 16 S rDNA sequencing. Mol Cell Probes. 2000;14:163–169. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.2000.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Chen YX, Liu H, Wang YP. [Preliminary application of PCR-DGGE to analyzing microbial diversity in biofilters treating air loaded with ammonia] Huan Jing Ke Xue. 2004;25:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasiah IA, Wong L, Anderson SA, Sissons CH. Variation in bacterial DGGE patterns from human saliva: over time, between individuals and in corresponding dental plaque microcosms. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertoglu B, Calli B, Girgin E, Inanc B, Ozturk I. Comparative analysis of nitrifying bacteria in full-scale oxidation ditch and aerated nitrification biofilter by using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2005;40:937–948. doi: 10.1081/ese-200056115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyautey E, Lacoste B, Ten-Hage L, Rols JL, Garabetian F. Analysis of bacterial diversity in river biofilms using 16S rDNA PCR-DGGE: methodological settings and fingerprints interpretation. Water Res. 2005;39:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez O, Gasol JM, Massana R, Mas J, Pedros-Alio C. COMPARISON OF DIFFERENT DGGE (DENATURING GRADIENT GEL ELECTROPHORESIS) PRIMER SETS FOR THE STUDY OF MARINE BACTERIOPLANKTON COMMUNITIES. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xiao Y, Yang ZH, Zeng GM, Ma YH, Liu YS, Wang RJ, Xu ZY. [Bacterial diversity in sequencing batch biofilm reactor (SBBR) for landfill leachate treatment using PCR-DGGE] Huan Jing Ke Xue. 2007;28:1095–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte IC, Oliveira LL, Saavedra NK, Fantinatti-Garboggini F, Oliveira VM, Varesche MB. Evaluation of the microbial diversity in a horizontal-flow anaerobic immobilized biomass reactor treating linear alkylbenzene sulfonate. Biodegradation. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10532-007-9143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GT, Webster G, Wimpenny JW, Kim BH, Kim HJ, Weightman AJ. Bacterial community structure, compartmentalization and activity in a microbial fuel cell. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:698–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster NS, Negri AP. Site-specific variation in Antarctic marine biofilms established on artificial surfaces. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1177–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain AJ, Bartolo RG, Catrenich CE, Charbonneau D, Ledder RG, Rickard AH, Symmons SA, Gilbert P. Microbial characterization of biofilms in domestic drains and the establishment of stable biofilm microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:177–185. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.177-185.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ku CY, Xu J, Saxena D, Caufield PW. Survey of oral microbial diversity using PCR-based denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. J Dent Res. 2005;84:559–564. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I, Frazier EH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of chronic venous ulcers. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:426–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbancic-Rovan V, Gubina M. Bacteria in superficial diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Med. 2000;17:814–815. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00374-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler PG, Davies BJ. The microbiology of infected and noninfected leg ulcers. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:573–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell-Jones RS, Wilson MJ, Hill KE, Howard AJ, Price PE, Thomas DW. A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:143–149. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K, Debus ES, St J, Ziegler U, Thiede A. Bacterial population of chronic crural ulcers: is there a difference between the diabetic, the venous, and the arterial ulcer? Vasa. 2000;29:62–70. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.29.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler PG, Davies BJ, Jones SA. Microbial involvement in chronic wound malodour. J Wound Care. 1999;8:216–218. doi: 10.12968/jowc.1999.8.5.25875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I. Microbiological studies of decubitus ulcers in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:207–209. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90912-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson C, Hoborn J, Moller A, Swanbeck G. The microbial flora in venous leg ulcers without clinical signs of infection. Repeated culture using a validated standardised microbiological technique. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:24–30. doi: 10.2340/00015555752430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontiainen S, Rinne E. Bacteria in ulcera crurum. Acta Derm Venereol. 1988;68:240–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CE, Wilson MJ, Hill KE, Stephens P, Hill CM, Harding KG, Thomas DW. Use of molecular techniques to study microbial diversity in the skin: chronic wounds reevaluated. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9:332–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Tseng CH, Pei Z, Blaser MJ. Molecular analysis of human forearm superficial skin bacterial biota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607077104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekio I, Hayashi H, Sakamoto M, Kitahara M, Nishikawa T, Suematsu M, Benno Y. Detection of potentially novel bacterial components of the human skin microbiota using culture-independent molecular profiling. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:1231–1238. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trengove NJ, Stacey MC, McGechie DF, Mata S. Qualitative bacteriology and leg ulcer healing. J Wound Care. 1996;5:277–280. doi: 10.12968/jowc.1996.5.6.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Watson GK, Allison C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and coaggregation in anaerobe survival in planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities during aeration. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4729–4732. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4729-4732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K, Lewandowski Z. Microelectrode measurements of local mass transport rates in heterogeneous biofilms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;59:302–309. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980805)59:3<302::AID-BIT6>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I. Role of anaerobic bacteria in aortofemoral graft infection. Surgery. 1988;104:843–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I. Role of encapsulated anaerobic bacteria in synergistic infections. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;14:171–193. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]