On a national level, Hurricane Katrina highlighted gaps in services and demonstrated the need for good community practices of care for those medically at risk during disaster events. Locally, the Brevard County Health Department (BCHD) initiated a response to this need in 1992 after returning from deployment for Hurricane Andrew. Having a 72-mile-long Atlantic coastline; a county that is one-third water and mostly flood plains; more than 500,000 residents, one-fifth of whom have special needs;1 and a robust manufactured housing community, Brevard recognized its own vulnerability.

BCHD took the lead by creating dialogues with interested community members—those with special needs and those caring for people with special needs. These discussions led to community partnerships and mutual aid agreements culminating in the Coordinated Care Special Needs Shelter (CCSNS) model practice—a virtual network of care wrapping all of the necessary goods and services of the special needs independent citizen safely around them. Victorious events of this network of care were successfully demonstrated in the 2004 hurricane season, when Brevard County expertly sheltered and safely shepherded home or to safe havens 100% of its most vulnerable citizens on three separate occasions, consecutively.

BACKGROUND

Located along Florida's central eastern coastline, Brevard County is a geographically and socioeconomically diverse community. Due to its subtropical climate, Brevard has its share of natural disasters such as hurricanes and tornadoes. The environmental situation in the county is also unique due to its lengthy coastline along the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian River lagoon system, the Banana River, and the St. John's River and flood plain system. These hydrological circumstances create a county that is one-third water; of the remaining land mass, 60% is flood-prone. Combined with 10% manufactured homes and one-fifth of its population having one or more disabilities, BCHD has up to 1,500 people with special needs during mass disaster events. And as the events surrounding Hurricane Katrina have demonstrated, ensuring the welfare of our most vulnerable independent citizens during a disaster event is both a moral and a national priority.

INITIATIVE SUMMARY

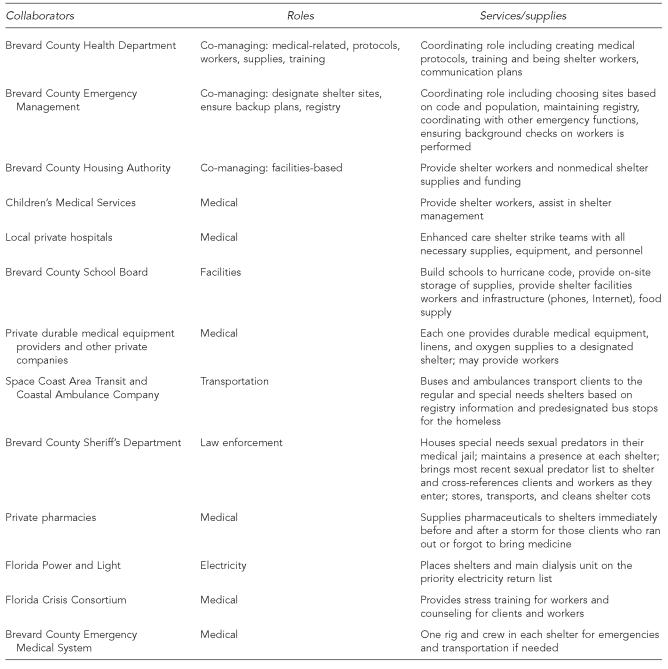

As part of its core public health mandate to protect the health and welfare of its citizens, BCHD took the lead by gathering community members involved in caring for the county's most vulnerable citizens of all ages. As with any daunting task, this was best accomplished by dividing the coordinating responsibility among three community stakeholders: BCHD, Brevard County Housing Authority (BCHA), and Brevard County Emergency Management (BCEM). This partnership works together to oversee the entire CCSNS system, but each member is also responsible for managing its area of interest with its traditional partners, creating more cohesion among all stakeholders (Figure).

Figure.

Collaborators, roles, and services/supplies provided for the Coordinated Care Special Needs Shelter

The BCHD is responsible for all things health and medical: workers, pharmaceuticals, supplies, protocols, medical and behavioral trainings, and crisis intervention, if needed. Other responsibilities include creating memoranda of understanding (MOU) with hospitals, durable medical equipment companies, home health agencies, dialysis centers, and oxygen and linen supply companies. A key element creating buy-in with these medical partners is specifying only one shelter for them to supply, including a consolidation shelter if necessary, rather than having them track down their individual patients throughout the entire county during an incident. As it can take up to two hours to traverse the county on a normal day, they appreciate our efforts to make their responsibility manageable.

Another unique aspect to our shelters is an enhanced shelter section staffed by our hospitals. Standard evacuation convention calls for citizens with an enhanced level of special needs (i.e., those with a home ventilator, those who are bed-bound, and hospice patients) to mobilize to the nearest tertiary facility. Experience with this traditional practice led to hospital overcapacity at a time of critical need, financial loss, and difficulty in maintaining the individuals' pre-event health status. Analysis demonstrated a more medically and fiscally sound option for our clients and the hospitals. Each hospital system now designates a fully equipped enhanced shelter strike team consisting of a doctor, nurses, medical equipment, supplies, and pharmaceuticals (palletized and ready to go), providing a higher level of medical care within our shelter. And even though the special needs registry is updated yearly and assigns patrons into specific levels of care (i.e., general, special, enhanced), this allows nursing retriaging of clients at the shelters even at the height of the storm, as medical conditions often change.

Other areas of expertise for BCHD include providing shelter worker training to its own employees, volunteers, and county and school workers. The medical and nursing directors set medical protocols, the epidemiology department provides infection control guidelines, and the preparedness department provides incident command training and establishes communication and backup consolidation plans.

The yearly planning cycle begins in December, at the close of the hurricane season, when lessons learned are reviewed and incorporated into plans. Monthly stakeholder meetings begin in January to ensure partnerships and plans are in place by June—the official start of the hurricane season. BCHD learned early on that fundamental to making these meetings useful is to limit their number and ensure the right associate mix. For instance, the Special Needs Advisory Group consists of principal leaders from all the different health disciplines. However, the home health care, medical equipment providers, and pharmaceutical groups also have their own forum, so that all concerns, ideas, and disagreements can be voiced in a common-ground setting and then brought up to the advisory group level.

BCHA's main focus is facilities—ensuring that hurricane-worthy buildings designated by emergency management function and have working backup electricity and water, and providing space for and transporting supplies. This involves bringing together a diverse mix of associates—including county facilities workers, public works employees, and crucial members of the school board (i.e., representatives from their county-wide facilities and information technology departments, principals, assistant principals, school facilities and cafeteria workers)—from each designated shelter. One of our lessons learned is to ensure at least twice-yearly meet-and-greet appointments with these critical infrastructure individuals, as many of these positions can turn over quickly.

Recognizing that special needs shelters are a priority for its constituents, Brevard County provides additional shelter workers in addition to yearly financial support to purchase medical supplies and equipment and rent generators. Each of our four special needs shelters has two shelter managers from the county who are responsible for that specific shelter and who not only work closely with their health department shelter supervisor cohorts during operations, but also meet in peacetime to plan and provide for a more cohesive team approach. BCHD takes the lead on health-related issues, but if there is a lack of water to flush toilets, the county manager creates a solution. Another “secret” related to county workers is to use Parks and Recreation's expertise to manage the daycare for our shelter workers' families.

BCEM brings to the table its traditional partners of law enforcement, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS), the 911 call center, private ambulance service companies, public transportation, and Animal Services. BCEM was the natural repository for the annually updated special needs client registry allowing for bus or ambulance transportation coordination. Law enforcement is responsible for safety issues, including background screening of all workers and clients, making sexual predators with special needs aware of their provision of a medical jail shelter, maintaining a presence at our facilities, and allowing for safe passage for shelter workers during curfews. Communication among all and with EMS is maintained throughout the event, and Animal Services kennels pets belonging to both the workers and the sheltered.

BCEM also has accountability to designate shelters, ensuring they meet hurricane codes and have full backup generators. They have been working with their state-level counterparts to obtain federal grants to provide these generators; so far their efforts have yielded only one generator, which is in the process of being hooked up to a central facility. Contingency planning—BCEM's forte—includes using county funds for one generator rental and working with the hospitals to provide a generator and hook-up to each of the other two shelters.

This cohesive structure has been established through written MOUs and preplanned shelter roles that the BCHD team trains with drills and just-in-time instruction. Many shelter workers have no medical background, but successfully perform the required preestablished responsibilities due to shelter team training and through unambiguous assignments.

Nationally, Hurricane Katrina highlighted gaps in services, demonstrating that communities need local plans in place to care for those medically at risk during disaster events. CCSNS addresses these needs by establishing and maintaining a network of partnerships. This model, which has been tested by multiple real-life incidents, evolved to include explicit communication/backup plans, established medical protocols, and typing of skill sets to allow triage into assigned levels of care. Brevard County and BCHD invented innovative solutions to resolve issues that will arise for other communities, including the need to do background screenings on both workers and the sheltered, and contingency consolidation plans if clients cannot return home.

OUTCOME AND EVALUATION

The ability to develop, test, and implement change is essential for any venture that wants to continuously improve. Creatively combining these change ideas with a process evaluation tool such as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle tests for real improvement. BCHD successfully uses this PDSA concept in its continual improvement of the CCSNS model. During the yearly planning cycle, processes are identified and evaluated at full stakeholder meetings. Novel concepts resulting from newer technologies, opportunities, and partners are brought to the table and reviewed in a PDSA cycle. Currently, we are studying new ways to transport cots and looking into the new portable on demand storage industry. After this study process, new agreements and methods are incorporated into the model and tested. During-the-event innovations are identified, reviewed, and, if successful, integrated. Debriefings and after-incident reports also demonstrate lessons learned that are celebrated and added to the model. The triumph of this process evaluation leads to dynamic model improvement that keeps all stakeholders integrated into the CCSNS's success.

For our 2004 hurricane season, our shelters served an average of 1,500 clients during each of the three hurricane events. Plans for backup electricity and resupply of oxygen were utilized to ensure that the 275 oxygen-dependent people survived. Pharmacies stayed open for our shelters and dispensed needed medications. Enhanced hospital-sponsored care within the shelters transferred about 20 individuals into their care and successfully treated others who stayed within the standard special needs area. Fallback communication plans within the shelter and to incident command in the Emergency Operations Center allowed for information and resource sharing. Excellent communication regarding dialysis patients that were housed in general, special needs, and enhanced care shelter areas was also lifesaving. The Florida Crisis Consortium provided much-needed crisis counseling to those in the shelters and the workers. The consolidation plan for our largest mobile home community, consisting of about 5,000 units, was successfully enacted for those who no longer had a home.

In light of other national disasters with unstructured planning and untested models of care, the public health success of the CCSNS is very clear. The relatively simple and economic implementation of the CCSNS model by other communities can prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality. Brevard County would be humbled to be involved in this process. The positive outcome evaluation of this model was demonstrated by the success of attaining our goal: ensuring the health, welfare, and safe return home of 100% of our sheltered, most medically vulnerable individuals through our full continuum of care safety net, during the three consecutive hurricane events in 2004.

DISCUSSION

The CCSNS model successfully works though a network of collaborative efforts championed by the BCHD and supported by our county government, emergency management, school district, law enforcement, transit authority, children's medical services, and public and private medical partners, to name but a few. This mantle of care wraps services around independent people with special needs, ensuring their health, welfare, and eventual safe passage home after a mass incident.

This community network, long maintained by the BCHD, also grows through partnership-driven evolution. Examples include the full-service hospital teams (physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and equipment) now available within the shelter during the height of the storm. The county provides both fiscal and human resources. The school district ensures available hurricane-worthy shelters with generators, food and water, and facility workers. Private businesses appreciate having a predesignated shelter to supply with linens, oxygen, medical equipment, and personnel. Law enforcement transports and disinfects cots, supplies officers at each site, shelters sexual predators with special needs at their medical facility, and provides victim advocates for stress counseling.

This entire blanket of security attending to each and every need of all of our medically vulnerable but independent population sheltered during a mass incident is more than any single private or government entity could undertake alone. As it continues to grow in scope and complexity, it attains even greater accomplishment and acceptance each year, functioning as an interdependent, community-based response to an essential public health need, thus perpetuating continuous buy-in from all parties. By allying together, this network offers the full breadth of protection, shares costs, offers equitability among all partners, and in the long term saves money.

Although the value cannot be demonstrated in exact dollar figures, one hospital was losing $75,000 per day by closing its surgery ward, where they set up their enhanced care shelter. By incorporating an economical medical team within our CCSNS, the hospital can now perform profitable surgeries and necessary life-sustaining medical interventions that would have otherwise been deferred. Fiscally economical answers and fair solutions exist for all involved.

The sustainable nature of the CCSNS model actually derives from the strength of its community collaboration. In this new age of preparedness, post-Katrina and 9/11, the entire community has a vested interest in ensuring the health, welfare, and safe return home of our most vulnerable population during disaster events. By presenting neighborhood stakeholders with an accomplished model that has been tested during real-life mass incidents, any community partner will quickly realize that through continued performance of its normal operations and with minimal added effort and cost base, it can be a successful part of this complete blanket of care.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census. 2000. [cited 2008 Jan 28]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html.