Abstract

The transient rise of intracellular Ca2+ in detrusor smooth muscle cells is due to the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. However, it is not known how store refilling is maintained at a constant level to ensure constancy of the contractile response. The aim of these experiments was to characterise the role of L-type Ca2+ channels in refilling. Experiments used isolated guinea-pig detrusor myocytes and store Ca2+ content was estimated by measuring the magnitude of change to the intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) after application of caffeine or carbachol using epifluorescence microscopy. Membrane potential was controlled when necessary by voltage clamp. After Ca2+ stores were emptied they refilled with an exponential time course, with a time constant of 88 s. The value of the time constant was similar to that of the undershoot of [Ca2+]i following store Ca2+ release. The degree of store filling was enhanced by maintained depolarisation, or by transient depolarising pulses, and attenuated by L-type Ca2+ channel antagonists. Inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase prevented refilling. Reduction of the resting [Ca2+]i was accompanied by membrane depolarisation; under voltage clamp reduction of [Ca2+]i decreased the number and magnitude of spontaneous transient outward currents. Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, elicited by caffeine or carbachol, is independent of membrane potential under physiological conditions. However, store refilling occurs via Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels. Ca2+ influx is regulated by a feedback mechanism whereby a fall of [Ca2+]i reduces the activity of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, causing cell depolarisation and an enhancement of L-type Ca2+ channel conductance.

The motor drive to the urinary bladder is predominantly via postganglionic parasympathetic nerves (Brading, 1987). In normal human detrusor muscle contraction is mediated exclusively by acetylcholine binding to muscarinic M3 receptors on the cell membrane. Their activation initiates the generation of inositol trisphosphate (Iacovou et al. 1990), a rise of the intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) (Fry et al. 1994) and muscle contraction (Sibley, 1984).

With detrusor from most animals, and also human tissue under certain pathological conditions such as detrusor instability (Bayliss et al. 1999), ATP acts as a secondary cotransmitter by depolarising the muscle cell. Detrusor smooth muscle is capable of generating action potentials (Creed et al. 1983; Brading & Mostwin, 1989) with the upstroke supported by Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels (Klockner & Isenberg, 1985; Montgomery & Fry, 1992) and which is sufficient to cause a significant rise of [Ca2+]i (Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1991; Wu & Fry, 1998). However, the physiological role of the action potential and the L-type Ca2+ channel in detrusor contractile function is not clear, especially as normal human detrusor muscle can function purely by muscarinic receptor activation and independent of changes to the membrane potential. Ca2+ influx may play a role in generating spontaneous contractions observed in detrusor muscle from unstable bladders (Kinder & Mundy, 1987; Wu et al. 1997) and also mediate the contractile action of purinergic neurotransmitters (Hashitani & Suzuki, 1995; Wu et al. 1999a). However, the role of electrophysiological processes in the generation and maintenance of normal detrusor contractions initiated by cholinergic activation is not understood.

It has been suggested that cross-talk between electrophysiological systems and second messenger pathways may exist in some smooth muscles (Somlyo & Somlyo, 1994). However, little work has been carried out on the involvement of the Ca2+ channel in cholinergic pathways. Ca2+ channel antagonists or removal of extracellular Ca2+ attenuate carbachol-induced contractions, although to a lesser extent than their actions on high K+ or ATP-induced contractions (Mostwin, 1985; Maggi et al. 1988; Kishii et al. 1992). However, it does suggest an involvement of the Ca2+ channel in the contraction mediated by cholinergic activation, although these experiments gave no insight into the mode of action. In addition, Ca2+ channels may also be involved in replenishing intracellular Ca2+ stores, following Ca2+ release by neurotransmitters, to maintain the cycling of Ca2+ in response to repetitive stimuli. Experiments using contraction as an index of the size of such internal Ca2+ stores have shown that in tracheal smooth muscle, the L-type Ca2+ channel is partially involved in the refilling of acetylcholine-sensitive Ca2+ stores (Bourreau et al. 1991). Direct measurement of intracellular Ca2+ has also shown that the Ca2+ channel plays a role in caffeine-sensitive stores in coronary artery smooth muscle (Sturek et al. 1992). However, such a role of the Ca2+ channel in a smooth muscle such as detrusor that contracts phasically (Rivera et al. 1998) has not been examined.

The present study was undertaken firstly to clarify the role of the L-type Ca2+ channel in initiating the rise of intracellular Ca2+ associated with contraction, and secondly to investigate its role in refilling intracellular Ca2+ stores in cholinergic pathways. Our results show that the primary activation of cholinergic pathways is independent of membrane potential and the opening of the L-type Ca2+ channel, but can be modulated by secondary voltage-dependent membrane events. More importantly, the L-type Ca2+ channel may play a role in maintaining Ca2+ entry and refilling functional intracellular Ca2+ stores.

METHODS

Cell isolation

Single detrusor smooth muscle cells were obtained from guinea-pig urinary bladders. Guinea-pigs (400–900 g) were killed by cervical dislocation or concussion in accordance with current UK Home Office procedures. The bladder was quickly removed and placed in Ca2+-free solution containing (mm): NaCl, 105.4; NaHCO3, 20.0; KCl, 3.6; MgCl2, 0.9; NaH2PO4, 0.4; glucose, 5.5; sodium pyruvate, 4.5; Hepes, 4.9; pH 7.1. Small strips of detrusor muscle were cut from the dome of the bladder and cells were dissociated using a collagenase-based enzyme mixture dissolved in Ca2+-free solution as described previously (Montgomery & Fry, 1992).

Solutions

Myocytes were continuously superfused with Tyrode solution containing (mm): NaCl, 118; NaHCO3, 24.0; KCl, 4.0; MgCl2, 1.0; NaH2PO4, 0.4; CaCl2, 1.8; glucose, 6.1; sodium pyruvate, 5.0; pH 7.4, gassed with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. Zero-Ca2+ superfusate contained no added CaCl2 and 0.1 mm EGTA, which buffered the ionised Ca2+ concentration to approximately pCa 8. The intracellular filling solution for patch pipettes contained (mm): KCl, 20; aspartic acid, 100; MgCl2, 5.45; Na2ATP, 5.0; Na3GTP, 0.2; EGTA, 0.05; Hepes, 5.0; pH 7.1 adjusted with KOH.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was measured by epifluorescence microscopy using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2. Cells were loaded with 5 μm fura-2 acetoxymethyl (AM) ester at 25 °C for 30–60 min and then stored at 4 °C for later use. An aliquot of cell suspension was placed in a chamber mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope and superfused at 37 °C with Tyrode solution. The cells were illuminated alternately at 340 and 380 nm. The emitted light was split by a dichroic mirror centred at 410 nm, and collected by a photomultiplier between 410 and 510 nm.

The fura-2 ratio signal was converted to [Ca2+]i values using an in vitro calibration method (eqn (1)). The relationship between [Ca2+]i and the ratio R (fluorescence ratio at 340 nm/380 nm excitation) is given by (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985):

| (1) |

where R is the fluorescence ratio under study, Rmin and Rmax refer to ratio values at zero [Ca2+] and saturating [Ca2+], respectively, β is the ratio at zero and saturating [Ca2+] at 380 nm alone, and Kd (224 nm) is the dissociation constant of fura-2 for Ca2+.

Electrophysiological recordings

Membrane potential and ionic currents were recorded with patch-type electrodes in the whole-cell configuration. An Axopatch-1D amplifier system (Axon Instruments) was used to perform current or voltage clamp. An IBM-compatible computer was used to generate voltage-clamp protocols and record membrane currents via an A/D converter (Digidata 1200; Axon Instruments) with a sampling frequency of 4 kHz and cut-off frequency of 2 kHz. Voltage-clamp protocols were supported by pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate glass (1.5 mm o.d./0.8 mm i.d.) and had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ when filled with the above intracellular solution. For simultaneous recording of [Ca2+]i, cells were dialysed with fura-2 via a patch pipette filled with the intracellular solution containing 100 μm K5-fura-2 (Calbiochem). This gave a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio without a significant effect on the Ca2+ transient (Wu & Fry, 1998).

In some experiments, high resistance (20 MΩ) microelectrodes were used to impale the cell and record the membrane potential without dialysing the intracellular space. Microelectrodes were filled with a potassium aspartate solution containing 1000 mm aspartic acid and 35 mm KCl; pH 7.1 with KOH. These allowed voltage following to be performed with a similar time resolution to that of conventional 3 m KCl-filled microelectrodes, but with a more stable cell penetration. The tip and junction potentials were nulled before cell impalement and remained stable throughout the experiment: the KCl was included to minimise disturbance of the intracellular [Cl−]. Membrane potential was recorded by a unit gain headstage (HS-2), connected to an Axoclamp-2A microelectrode clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments).

Muscle preparations and measurement of isometric tension

Mucosa and serosa were dissected from the bladder and a thin strip of muscle (< 0.4 mm in diameter, 5–6 mm in length) was carefully was cut using a binocular dissection microscope. The muscle strip was tied at one end to a fixed hook and at the other to an isometric tension transducer. The preparation was superfused with Tyrode solution in a horizontal trough (4 mm × 4 mm × 15 mm long) at a rate of 5–10 ml min−1. Muscles were stimulated by addition of agonists to the superfusate. The tension transducer output was amplified and filtered at a cut-off frequency of 15 Hz. The signal was displayed on a storage oscilloscope and down-loaded to a pen recorder.

Statistics

Numerical data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Student's t test was used to test the significance of difference between two data sets of equal variance, and the modified t test used for two data sets of unequal variance. The null hypothesis was rejected when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characterisation of intracellular Ca2+ transients induced by cholinergic activation

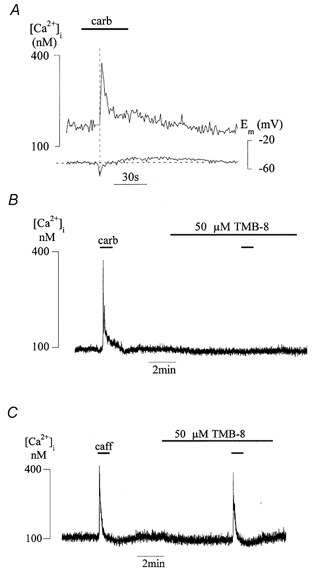

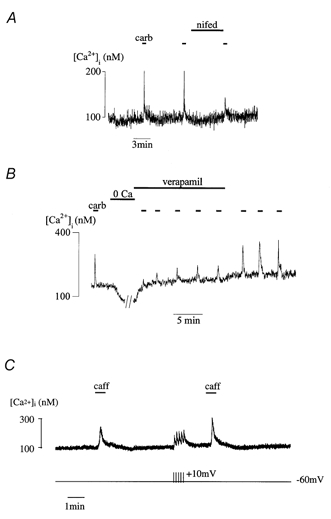

Figure 1A shows that, in an isolated myocyte, the acetylcholine analogue carbachol (20 μm) transiently increased the [Ca2+]i. The Ca2+ transient was preceded or coincided with a hyperpolarisation in 85 % (24 of 28) of cells, followed by a small depolarisation (8.8 ± 1.3 mV, 26 of 28 cells) that always occurred after the peak of the Ca2+ transient. Such a pattern is consistent with the induction of Ca-activated outward and inward currents due to a rise of [Ca2+]i. A qualitatively similar pattern of changes to [Ca2+]i and membrane potential occurred if caffeine was used to generate the Ca2+ transient. It has been demonstrated previously (Wu & Fry, 1998), and confirmed here, that a short (60 s) pre-exposure to an L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist (5–10 μm nifedipine or 20 μm verapamil) did not significantly affect the magnitude of this Ca2+ transient (98.3 ± 5.5 % of control, n = 8, P > 0.05), although this protocol reduced peak inward Ca2+ current by more than 80 % and abolished ATP-dependent Ca2+ transients that are elicited by membrane depolarisation.

Figure 1. Carbachol- and caffeine-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients.

A, intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) and membrane potential (Em) in an isolated detrusor myocyte. The horizontal dashed line indicates the time of peak hyperpolarisation; the vertical line indicates the Em value prior to carbachol additon. B, carbachol (20 μm) induced Ca2+ transients in the absence and presence of 50 μm TMB-8 (the agents were added as indicated by the horizontal bars). C, caffeine (20 mm) induced Ca2+ transients in the absence and presence of 50 μm TMB-8.

Carbachol induces the Ca2+ transient by eliciting Ca2+ release from an intracellular Ca2+ store that is substantially overlapped by a caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ store (Wu & Fry, 1998). However, the mechanism for triggering Ca2+ release by carbachol is different from that by caffeine, as shown by the effect of 8-(N, N-diethylamino)-octyl-3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate, HCl (TMB-8), which preferentially inhibits inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated release from intracellular Ca2+ stores (Anderson et al. 1992; Haughey et al. 1999). In the presence of 50 μm TMB-8 HCl, the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient was effectively abolished (n = 4, see Fig. 1B), whilst caffeine Ca2+ transients persisted (87 ± 7 % of control, P > 0.05, n = 5, Fig. 1C). This suggests that carbachol generates Ca2+ transients via the IP3 cascade, a mode of action not shared by caffeine.

It has been demonstrated in vascular smooth muscle that IP3-induced Ca2+ release (IICR) itself may be modulated by membrane potential (Ganitketvich & Isenberg 1993). However, in the detrusor cells varying membrane potential (Em) between −80 and +20 mV did not alter the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient. These data show that IICR in detrusor muscle is not facilitated by membrane depolarisation and that L-type Ca2+ channels play no role in generation of the Ca2+ transient. Further experiments were carried out to identify the nature of the Ca2+ store.

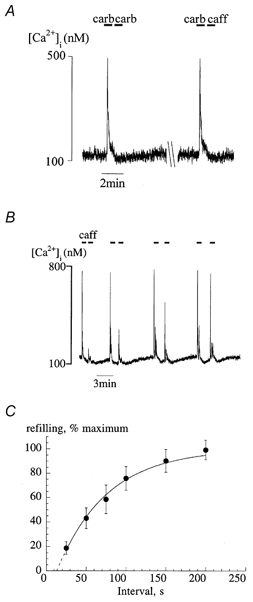

Characteristics of intracellular Ca2+ store refilling

The intracellular Ca2+ store can be depleted completely by a maximal effective concentration of either carbachol (20 μm) or caffeine (10–20 mm). Figure 2A shows that a rapid second exposure to either carbachol or caffeine after an initial carbachol intervention did not elicit a second Ca2+ transient. However, Fig. 2B shows that as the interval between paired exposures (in this case to caffeine) was increased, the Ca2+ transient gradually recovered. Attenuation of the second response was not due to receptor desensitisation, as caffeine and carbachol were equally ineffective in generating the second transient, regardless of the agonist used to generate the first response. Thus although carbachol and caffeine release intracellular Ca2+ via different mechanisms, both agonists seem to act on the same store with equal effectiveness. In the following experiments Ca2+ store properties are explored using both agonists.

Figure 2. Depletion and the time course of restoration of intracellular Ca2+ stores.

A, exposure to two applications of carbachol (20 μm) in rapid succession (left) or carbachol followed by caffeine (20 mm; right). Exposure periods are shown by the horizontal bars. B, paired exposures to caffeine (20 mm) at different intervals as indicated by the horiontal bars. C, plot of the recovery of the caffeine transient as a function of interval (t) between paired exposures. The data are plotted as a percentage of the second vs. first Ca2+ transient magnitude (% recovery) for each pair. Values are means ± s.e.m., n = 7. The line is a least-squares fit using the equation: %Recovery = 100(1 – exp(-(t–t0)/τ)). τ is the time constant of the curve; the curve has been extrapolated to intersect the abscissa at t0.

Figure 3C shows the mean data for the restoration of the maximal caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient, fitted to an exponential function (eqn (2)):

| (2) |

where t0 is a constant representing the intersection of the curve with the abscissa, corresponding to an absolute ‘refractory’ period when caffeine cannot trigger any Ca2+ release from the store (15.8 ± 4.1 s, n = 7). The restitution time constant (τ) for refilling the store was 88 ± 16 s (n = 7).

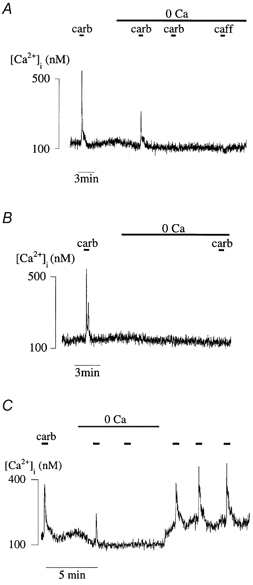

Figure 3. Carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients in zero-Ca2+ solution.

A, Ca2+ transients in 1.8 mm and zero-Ca2+ superfusates; there were three exposures to either carbachol or caffeine during the zero-Ca2+ superfusion. B, Ca2+ transients in 1.8 mm and zero-Ca2+ superfusates; a single carbachol exposure was introduced at the end of the zero-Ca2+ superfusion. C, Ca2+ transients in 1.8 mm and zero-Ca2+ superfusates and return to 1.8 mm Tyrode solution. In each trace carbachol exposure is indicated by the horizontal bars.

Depletion of the Ca2+ store was produced by removal of extracellular Ca2+ and the store could not be refilled in its absence. Figure 3A shows that during superfusion with a zero-Ca2+ solution, the releasable Ca2+ was gradually reduced, and second and third exposures to carbachol or caffeine elicited no further response: note also reduction of the resting [Ca2+]i in this solution. Even with no intermediate agonist application (Fig. 3B), a prolonged exposure to zero-Ca2+ solution completely depleted the Ca2+ store. This suggests an exchange of Ca2+ between extracellular and intracellular spaces, as well as between the sarcoplasm and the intracellular Ca2+ store. Figure 3C shows that upon restoration of extracellular Ca2+, the resting [Ca2+]i recovered and the response to agonists was completely restored (110 ± 6 % of pre-depletion level, n = 7) with a time constant (τ) of 112 ± 35 s. This τ value was not statistically different from the restitution value measured above with paired agonist exposures (Fig. 2C).

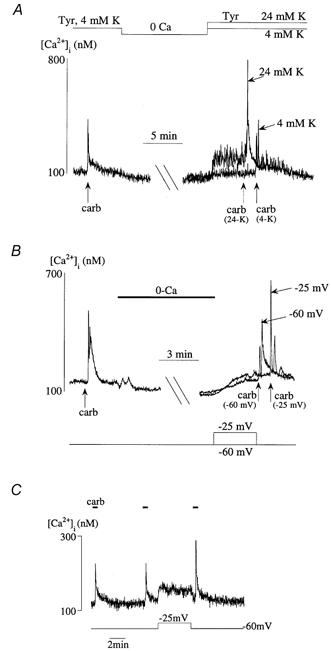

Membrane depolarisation enhances Ca2+ store refilling

Refilling of functional Ca2+ stores after zero-Ca2+ superfusion was facilitated by membrane depolarisation. Figure 4A shows the effect of raising the extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o). After a sufficient period to allow the Ca2+ transient to restore on return to a normal Ca2+-containing superfusate, a myocyte was exposed to carbachol. Figure 4A shows two superimposed carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients: one in a control [K+] (4 mm), and a second in a 24 mm K+ solution. Control carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients were similar to the pre-depletion transient (104 ± 9 %, P > 0.05, n = 9). In the 24 mm K+ solution the resting [Ca2+]i was restored to a higher level compared with that in the 4 mm K+ solution, and moreover the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient was significantly increased (135 ± 9 %; P < 0.05, n = 9). These data show that the quantity of Ca2+ sequestered in functional intracellular Ca2+ stores is related to the availability of sarcoplasmic Ca2+.

Figure 4. Membrane depolarisation and Ca2+ store refilling.

A, carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients before and after zero-Ca2+ solution. Two Ca2+ transients are superimposed after the zero-Ca2+ solution, in 1.8 mm Tyrode solution containing either 4 mm or 24 mm KCl. B, a similar format to A in which the cell membrane potential (Em) was held under voltage clamp. Two carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients are superimposed after zero-Ca2+ solution: one after the cell was briefly depolarised to −25 mV, the other when Em was held constant at −60 mV throughout. C, carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients in a detrusor cell under voltage clamp in Ca2+-containing Tyrode solution throughout. The cell was briefly depolarised from −60 to −25 mV between the second and third transients.

To control Em more precisely in the refilling period after zero-Ca2+ superfusion, experiments were performed under voltage-clamp, when Em was held at either −60 mV (near the normal resting potential) or at −25 mV (near the peak window current value for the L-type Ca2+ current as determined in control experiments). Figure 4B shows that a similar result was obtained to that in Fig. 4A: at −25 mV the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient was enhanced to 146 ± 15 % (P < 0.05, n = 5) of that when the cell was held throughout at −60 mV. The value of Em on replenishment of the carbachol-sensitive Ca2+ store was also important during continuous superfusion in Ca2+-containing Tyrode solution. Figure 4C shows that depolarisation from −60 to −25 mV enhanced the resting [Ca2+]i as well as the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient elicited immediately after repolarisation back to −60 mV (127 ± 14 % of control, P < 0.05, n = 15). Identical results were obtained if caffeine was used to generate Ca2+ transients; depolarisation from −60 to −25 mV enhanced refilling to 125 ± 7 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 8).

In normal extracellular [Ca2+], prolonged superfusion with 5 mm NiCl2 reversibly abolished the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient. As Ni2+ blocks membrane Ca2+ channels the role of such pathways in refilling was further investigated.

L-type Ca2+ channel manipulation and Ca2+ store refilling

Figure 5 shows an experiment when 10 μm nifedipine was added immediately after a carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient and throughout the interval before the next exposure to the agonist. The subsequent Ca2+ transient was significantly attenuated (47 ± 14 % of control, P < 0.05, n = 7). The interval between successive exposures allowed complete restitution in the absence of nifedipine as seen by the first two Ca2+ transients. Identical results were obtained if caffeine was used to elicit Ca2+ transients; they were reduced to 49 ± 5 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 9).

Figure 5. The L-type Ca2+ channel and Ca2+ store refilling.

A, carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients. Nifedipine (10 μm) was introduced between the second and third Ca2+ transients. B, carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients before and after zero-Ca2+ superfusate. Following the zero-Ca2+ solution verapamil (20 μm) was added to the Ca2+-containing superfusate for the first five carbachol exposures, thereafter the verapamil was removed. C, caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in a detrusor cell under voltage-clamp at −60 mV. Between the first and second exposures to caffeine the cell was subjected to a train of five depolarising steps (-60 to +10 mV, 500 ms duration).

Figure 5B shows the effect of verapamil (20 μm) on the refilling of Ca2+ stores after depletion in a zero-Ca2+ solution. When the extracellular Ca2+ was restored in the presence of verapamil, the level of refilling did not return to the control value (65 ± 10 % of control, n = 7, P < 0.05). Complete recovery was only seen when verapamil was removed from the extracellular solution.

These data suggest involvement of L-type Ca2+ channels in refilling intracellular Ca2+ stores. However, T-type Ca2+ channels have also been described in detrusor smooth muscle (Sui et al. 2001) and it may be possible that the Ca2+ antagonists may also block these ion channels. However, the concentrations of antagonists used were chosen to be less than those reported to influence T-type channel conductance (Stengel et al. 1998). Moreover, their actions were similar in the continuous presence of 0.2 mm NiCl2, which is sufficient to selectively block the T-type current in these cells. Nifedipine (10 μm) still reduced the carbachol and caffeine Ca2+ transients (52 ± 10 % of control, n = 3, P < 0.05) and by a magnitude was not significantly different from that in the absence of NiCl2.

Conversely, opening L-type Ca2+ channels should enhance Ca2+ store refilling. Cells were voltage clamped at −60 mV and a train of five depolarising pulses from −60 to +10 mV for 500 ms was applied during the refilling interval. Figure 5C shows that a second application of caffeine after the stimulation procedure enhanced the Ca2+ transient (127 ± 8 % of control, n = 18, P < 0.01). A similar result was obtained if carbachol was used to evoke Ca2+ transients (119 ± 8 % of control, n = 7, P < 0.05).

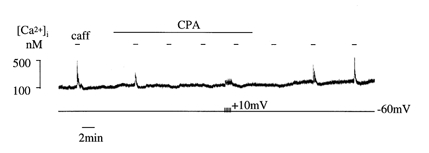

Refilling via L-type Ca2+ entry is dependent on the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump

The exact route whereby Ca2+ enter intracellular Ca2+ stores is unclear. It is possible that the superficial sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is filled directly, by routes that may or may not involve the SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), and that a rise of the bulk sarcoplasmic [Ca2+] is unnecessary (Casteels & Droogmans, 1981; Missiaen et al. 1990; Chen & van Breemen, 1993). However, the results of the present study are not compatible with this mechanism as the magnitude of Ca2+ store refilling is linked to similar changes of the bulk sarcoplasmic [Ca2+]. Lowering [Ca2+]i diminished releasable Ca2+ from the stores, and restoration of the [Ca2+]i after a zero-Ca2+ superfusate preceded the recovery of store releasable Ca2+ (Fig. 3). An alternative route therefore is that Ca2+ enters the sarcoplasm and is then pumped by the SERCA into the SR. To test this, depolarising pulses were applied in the presence of the SERCA inhibitor, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA). Figure 6 shows that 20 μm CPA attenuated the first caffeine Ca2+ transient and abolished subsequent events. During CPA exposure, a train of voltage steps to +10 mV induced ICa and transients of Ca2+ entry, but the caffeine response was not restored; however, upon CPA removal the Ca2+ transients were restored. A small transient increase of the resting [Ca2+]i was induced by CPA, probably by inhibition of sarcoplasmic Ca2+ removal via the SERCA into the SR, which was subsequently dissipated by other Ca2+ removal mechanisms. Additional experiments showed that carbachol transients were also suppressed by superfusion with CPA. This result suggests that SERCA activity is required for Ca2+ to fill the intracellular Ca2+ store, and direct Ca2+ flux from the L-type Ca2+ channel to the SR is unlikely.

Figure 6. Cyclopiazonic acid prevents Ca2+ store refilling.

Caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in a detrusor cell under voltage clamp. Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA; 20 μm) was added to the superfusate for the period indicated. The cell was depolarised by a train of pulses (-60 to +10 mV, 500 ms duration) between the last two caffeine exposures in CPA.

Possible mechanisms for activation of the L-type Ca2+ channel during refilling

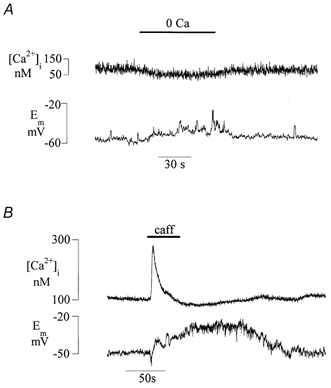

The experiments above have implicated Ca2+ channels in mediating the Ca2+ influx that maintains intracellular Ca2+ stores. Because channel conductance is dependent on the membrane potential Em, this was recorded during some of the conditions described above that affect the level of store filling. Figure 7A shows that brief exposure to a zero-Ca2+ solution reversibly reduced the [Ca2+]i and simultaneously generated oscillating depolarisations. The depolarisations were also recorded using microelectrodes, which excludes possible artifacts in zero-Ca2+ solutions using patch electrodes either from dialysis of the intracellular contents or from a reduced stability of the patch seal. The Em changes may have resulted from reduced screening of negative surface charges on the outer face of the membrane in the zero-Ca2+ solution. However, this was unlikely as superfusate CaCl2 was replaced by equimolar addition of MgCl2. Thus it is most likely that the membrane depolarisation occurs as a result of a reduced [Ca2+]i.

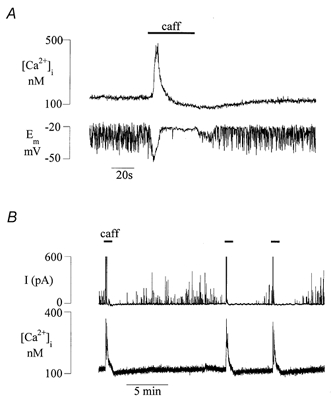

Figure 7. The relationship between [Ca2+]i and membrane potential.

A, simultaneous recordings of [Ca2+]i and Em in a detrusor cell under current clamp. The cell was exposed to a zero-Ca2+ solution for the period indicated. B, simultaneous recording of [Ca2+]i and Em during exposure to 20 mm caffeine.

Further evidence of a role for intracellular Ca2+ in determining Em was sought during caffeine addition in a normal extracellular Ca2+ solution. In Fig. 7B the recording time was longer than in Fig. 1 to include the pronounced undershoot of [Ca2+]i after the Ca2+ transient. The Ca2+ transient itself was associated with a brief hyperpolarisation but the subsequent undershoot of [Ca2+]i was accompanied by a prolonged depolarisation, large enough (about 25 mV) to favour opening of L-type Ca2+ channels. To exclude specifically the chance that this effect of caffeine was due to an increase of cyclic nucleotides from its phosphodiesterase activity, similar experiments used another methylxanthine, IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 0.5 mm), that also has potent phosphodiesterase inhibitory effects. The characteristic changes to intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential induced by caffeine could not be duplicated by IBMX, and excludes complications due to cyclic nucleotide accumulation.

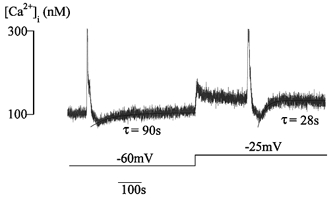

To assess the importance of membrane potential in determining Ca2+ store refilling, the time course of the Ca2+ transient undershoot after caffeine undershoot was measured as a function of Em. Figure 8 shows a paired experiment in which the time constant τ for recovery of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ undershoot was measured whilst the cell was clamped at either −60 or −25 mV. In eleven similar experiments τ was shortened from 118 ± 32 s at −60 mV to 69 ± 18 s at −25 mV (P < 0.05, n = 12). Similar results were obtained from a set of current-clamp experiments; τ was 105 ± 66 s at Em −60 mV and decreased to 75 ± 15 s at Em around −25 mV (P < 0.05, n = 11). These results show that recovery from the Ca2+ undershoot is voltage dependent and that depolarisation during this undershoot, following Ca2+ store depletion, plays a role in promoting recovery of resting [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ store refilling.

Figure 8. Recovery of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient undershoot at different membrane potentials.

Time course of recovery of [Ca2+]i from the undershoot following caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i release. Curves are the least-squares fit through the data points with a single exponential equation: A=A0 (1 – exp(- (t–t0)/τ)). The time course was measured at a holding potential of −60 mV and −25 mV under voltage clamp.

These results suggest that an electrophysiological event sensitive to changes of [Ca2+]i could provide the link between Em and [Ca2+]i. One possibility is a Ca2+-activated K+ current that is present in detrusor muscle during normal activity (Klockner & Isenberg, 1985; Wu et al. 1999b). Control voltage-clamp experiments demonstrated spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) after generation of an inward Ca2+ current, which were abolished completely either by 100 nm iberiotoxin, the BKCa channel antagonist (Galvez et al. 1990), or superfusion with zero-Ca2+ Tyrode solution.

Evidence for the diminished involvement of a Ca2+-activated transient outward current during [Ca2+]i reduction and store refilling was provided by the experiment shown in Fig. 9A. Em and [Ca2+]i were measured simultaneously during application of 20 mm caffeine; the cell was under current clamp with an Em of −20 to −30 mV to enhance the transient hyperpolarisations mediated by Ca2+-activated K+ current. During the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient, a single larger hyperpolarisation was recorded, followed during the undershoot of the Ca2+ transient by a much reduced activity of transient Em changes. Similar results were observed if carbachol was used to elicit the Ca2+ transient.

Figure 9. [Ca2+]i and spontaneous changes to membrane potential and membrane current.

A, simultaneous record of [Ca2+]i and Em in a detrusor cell during exposure to 20 mm caffeine. Em was under current clamp at between −20 and −30 mV when the cell was quiescent before the recording period began. B, simultaneous record of [Ca2+]i and membrane current in a detrusor cell during three applications of 20 mm caffeine.

Figure 9B shows that under voltage clamp, application of caffeine generated a large STOC during the Ca2+ transient itself, followed by complete cessation of activity during the Ca2+ transient undershoot until the [Ca2+]i had returned to the pre-intervention level and the store had refilled. This suggests that intracellular Ca2+, and more importantly the [Ca2+]i around the space between the sarcolemmal membrane and the peripheral SR and which is sensitive to the level of stored Ca2+ in the SR, regulates the BKCa channel and thus the average membrane potential. Such a hypothesis would predict a role for the BKCa channel in regulating the resting membrane potential in detrusor muscle. To test this Em was measured during application of 100 nm iberiotoxin and a depolarisation of 16.6 ± 5.9 mV (n = 4) was recorded; Em was recorded with microelectrodes, to minimise perturbation of the intracellular space.

Refilling assessed by muscle contraction measurements – effect of depolarisation and Ca2+ channel blockade

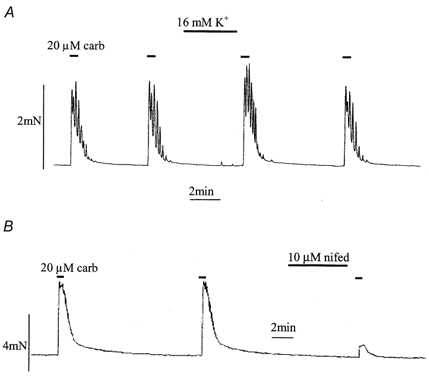

The above experiments using single isolated cells have important implications regarding the contractile behaviour of detrusor smooth muscle, as this is critically determined by the [Ca2+]i, although quantitative extrapolation is difficult. To assess the functional relevance, tension experiments were performed using similar interventions to those used above. Figure 10A shows that brief application of a maximally effective carbarchol concentration (20 μm) produced reproducible contractile events in isolated detrusor muscle strips. Elevation of extracellular K+ from 4 to 16 mm did not itself produce significant contractions (except small contractile oscillations), but increased the subsequent carbachol contraction by 110 ± 2 % (P < 0.05, n = 11). Figure 10B shows that 10 μm nifedipine added in the interval between successive applications of carbachol decreased the following carbachol contraction. On average, carbachol-induced contractile force was reduced to 14 ± 2 % of control (P < 0.01, n = 6). These results are qualitatively consistent with the equivalent experiments measuring intracellular Ca2+ transients under these conditions (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5).

Figure 10. Effect of membrane depolarisation and L-type Ca2+ channel blockade on carbachol-induced contractions.

A, effect of depolarisation on maximal (20 μm) carbachol-elicited isometric contractions of a detrusor muscle strip; superfusate KCl was raised to from 4 to 16 mm between the second and third contractions. B, effect of an L-type Ca2+ channel antagonist; 10 μm nifedipine was added between the second and third contractions.

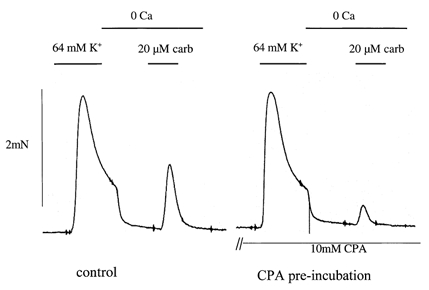

Refilling assessed by muscle contraction measurements – effect of CPA

The role of SERCA in Ca2+ store refilling was examined using carbachol-induced contractions induced 3–4 min after removal of extracellular Ca2+. Under these conditions the contraction was attributed mainly to intracellular Ca2+ store release and contributions from extracellular Ca2+ entry were minimised. Thinner strips (< 0.3 mm in diameter) were used and CPA was superfused for a long period (1.5–2 h) to maximise its penetration into the cells. A high extracellular [K+] (64 mm) was applied briefly prior to Ca2+ removal, and the contraction, which served as an internal control, was used as a measure of Ca2+ entry. The intervention was also a conditioning stimulation to enhance Ca2+ store refilling. Figure 11 shows that the carbachol-induced contraction in zero-Ca2+ was reduced after pre-incubation with 10 μm CPA, although the 64 mm K+-induced contraction was unaffected. The average carbachol contraction in zero-Ca2+ was reduced to 53 ± 10 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 10), whilst the 64 mm K+ contraction was 110 ± 7 % of control (P > 0.05). Thus SERCA inhibition reduced contractile force associated with Ca2+ released from intracellular stores, whilst the contraction due to extracellular Ca2+ entry was unaffected, and thus SERCA plays a functional role in Ca2+ store replenishment. A complete block of the carbachol contraction in zero-Ca2+ solution was difficult to achieve in the intact muscle strips, which may be due to a difficulty of CPA reaching the SR in sufficiently high concentrations throughout the preparation, despite their very small size.

Figure 11. Effect of CPA on carbachol contractions in zero-Ca2+ solution.

A contraction in normal Tyrode solution was elicited by application of 64 mm KCl followed by zero-Ca2+ solution during which 20 μm carbachol was applied. Left, control; right, pre-incubation with 10 μm CPA for 90 min.

DISCUSSION

L-type Ca2+ channels and cholinergic activation

Carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients result from intracellular Ca2+ release, as they could be elicited when the extracellular solution was about 10 nm (Wu & Fry, 1998). The intracellular source is likely to be the SR, as depletion of this store by prior treatment with caffeine abolished the subsequent carbachol response. The action of carbachol is likely to be mediated by IP3 production, as the agonist increases inositol phosphate production over a similar concentration range that generates Ca2+ transients (Iacouvou et al. 1990) and the Ca2+ transient was abolished by prior treatment with TMB-8 (Fig. 1). The efficacy of IP3-mediated release is high as the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient has a similar magnitude to that of the caffeine transient and application of the maximum effective concentration of carbachol (20 μm) abolished the caffeine transient. Such a system would therefore function efficiently to provide activator Ca2+ for the contractile machinery, irrespective of any Ca2+ entry from the sarcolemma.

Detrusor myocytes also express L-type Ca2+ channels at a current density sufficient to support the action potential upstroke (Montgomery & Fry, 1992). However, several lines of evidence suggest that membrane depolarisation, and hence L-type Ca2+ channel activation, is unimportant in the genesis of the carbachol-induced Ca2+ transient: (i) the L-type Ca2+ channel antagonists verapamil and nifedipine had no significant effect; (ii) membrane potential changed very little during carbachol application, a small membrane depolarisation sometimes followed the peak of the Ca2+ transient and (iii) the Ca2+ transient magnitude was independent of membrane potential when clamped between −80 and +20 mV. The Ca2+ transient was often accompanied by a hyperpolarisation, reflecting Ca2+-dependent K+ current activation, which may play a role in limiting excessive Ca2+ entry and hence Ca2+ overload. The cause of the depolarisation that followed the Ca2+ transient was unclear, however; if large enough it could open L-type Ca2+ channels and cause intracellular Ca2+ oscillations (Kohda et al. 1996).

Refilling of functional intracellular Ca2+ stores

Using maximum concentrations of agonists, releasable Ca2+ was completely discharged from the SR into the sarcoplasm, and the functional Ca2+ pool was empty as there was no further response to an immediate second stimulus. The lack of effect of the second exposure was not due to receptor desensitisation, as an alternative agonist acting via a separate mechanism was equally ineffective in releasing Ca2+. Following agonist removal refilling commenced after a delay of about 15 s, estimated from extrapolation of the refilling curve in Fig. 2C. This absolute refractory period may represent the time taken for Ca2+ to be transported from the re-uptake to release site, or the time for the Ca2+ pool to accumulate to a threshold level for further release, as there is evidence that Ca2+ release is a function of the luminal [Ca2+] (Missiaen et al. 1992). Subsequently, the response recovered with an exponential time course and a time constant (τ) of about 90 s. This is similar to the time course of recovery of the undershoot of the caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients in these experiments (107 ± 12 s; mean ± s.e.m., n = 7) and also those reported in myocardium and rat hippocampal neurones (Baro et al. 1993; Garaschuk et al. 1997). Such an interval is sufficient for detrusor muscle which contracts only intermittently during voiding and suggests that a major contributory factor to recovery of the undershoot is SR store refilling. From an experimental viewpoint an interval between stimuli in refilling experiments of at least 5τ was used, which would achieve more than 98 % refilling.

Ca2+ store refilling is dependent on extracellular Ca2+, via Ni2+-sensitive routes. The store Ca2+ content is also determined by the resting [Ca2+]i, as when this is low, e.g. in a zero-Ca2+ solution, the store cannot be refilled. Even in the absence of any triggered Ca2+ release, the Ca2+ store was depleted in the zero-Ca2+ solution. Refilling only commenced when the resting [Ca2+]i began to rise, and full restoration of the Ca2+ pool occurred only after complete recovery of the resting [Ca2+]i. These observations suggest that in detrusor cells the exchange of Ca2+ between the extracellular space, the sarcoplasmic pool and the SR lumen are all in dynamic equilibrium.

The role of the L-type Ca2+ channel in Ca2+ store refilling

One major component of the Ni2+-sensitive refilling pathway is the L-type Ca2+ channel, and evidence for involvement of this channel has come from several experiments using carbachol or caffeine to estimate the content of intracellular Ca2+ stores. (1) Membrane depolarisation enhanced store filling, after depletion by Ca2+ deprivation (Fig. 4). This was achieved either by raising the extracellular [K+] from 4 to 24 mm or under voltage clamp by changing Em from −60 to −25 mV, when Ca2+ entry via the L-type Ca2+ channel window current should be maximal (Montgomery & Fry, 1992). (2) Enhancement was achieved if Em was changed during the interval between successive applications of agonist under normal conditions of constant extracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 4C). (3) Brief depolarising steps under voltage clamp, to elicit a Ca2+ current, enhanced refilling (Fig. 5C). (4) Ca2+ store refilling was attenuated by verapamil or nifedipine after store depletion by either extracellular Ca2+ removal or application of carbachol or caffeine in normal extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5), and (5) Enhancement of refilling by elevated extracellular [K+] and attenuation of the refilling by nifedipine, measured as carbachol-elicited muscle contraction, further supported the functional relevance of the above findings.

The small role of L-type Ca2+ channels in the carbachol-induced rise of [Ca2+]i and their larger role in attenuating replenishment of functional Ca2+ stores explains both the smaller inhibitory effect of Ca2+ antagonists on carbachol-induced contractions compared with those generated by high K+ or ATP (Kishii et al. 1992), and also the progressively greater inhibition of carbachol-induced actions during continued exposure (Mostwin, 1985).

Refilling pathways

The experiments give insight into the processes that fill intracellular Ca2+ stores. It has been proposed that sarcolemmal Ca2+ entry could load preferentially superficial SR from a restricted sarcoplasmic micro-domain before it diffuses into the bulk sarcoplasm (Chen & van Breemen, 1993; van Breemen et al. 1995). Although a SERCA pump is required, store refilling would be independent of a change to the bulk sarcoplasmic [Ca2+]. Such a process is unlikely in detrusor muscle as depletion and replenishment of the Ca2+ store was affected by bulk resting [Ca2+]i. Recovery of resting [Ca2+]i occurred before restoration of the Ca2+ store pool (Fig. 3), which suggests that sarcolemmal Ca2+ influx enters the bulk sarcoplasm before substantial SR refilling.

In some non-excitable cells Ca2+ influx enters the SR via a direct low-resistance pathway, rather than uptake by a SERCA pump (Putney, 1986). Evidence for such a pathway was also provided in a rat aortic smooth muscle cell line (A7r5) by the observation that Mn2+ influx occurred without involvement of the SERCA pump, after SR depletion (Missiaen et al. 1990). In tracheal and oesophageal smooth muscle, a refilling pathway for the acetylcholine-sensitive Ca2+ store, which is sensitive to Ca2+ antagonists, is independent of the SERCA-specific inhibitor cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) (Bourreau et al. 1993; Liu & Farley, 1996; Salapatek et al. 1998). It has also been proposed that a preferred pathway exists whereby Ca2+ enters stores directly via L-type Ca2+ channels, bypassing the sarcoplasm (Janssen & Sims, 1993). In detrusor muscle, however, sarcoplasmic Ca2+ enters the SR mainly via the SERCA pump as CPA abolished subsequent Ca2+ release by caffeine (Fig. 6). Suppression by CPA of carbachol-elicited muscle contractions attributed to intracellular Ca2+ release was also qualitatively demonstrated (Fig. 11). Furthermore when Ca2+ entry was enhanced by depolarisation under voltage clamp, caffeine was still unable to generate a Ca2+ transient in the continued presence of CPA. Therefore, changes to SERCA pump activity significantly affect SR store refilling in detrusor muscle.

Although Ca2+ antagonists attenuated refilling of Ca2+ stores, they were unable to block it completely. Ca2+ entry via T-type Ca2+ channels has been described in detrusor (Sui et al. 2001), and in anococcygeous muscle store depletion-induced Ca2+ entry via these channels has been reported (Wayman et al. 1997). However, a major involvement of these channels in refilling is unlikely in detrusor muscle. Our experiments show that Ca2+ antagonists attenuated Ca2+ refilling to a similar degree in the absence or presence of 0.2 mm NiCl2, a concentration that preferentially blocks the T-type Ca2+ channels (Sui et al. 2001). Moreover, the concentrations of Ca2+ antagonists used will not affect T-type channel conductance (Stengel et al. 1998). Other potential entry pathways that require further investigation are reverse mode Na+-Ca2+ exchange (Wu & Fry, 2001), non-specific cation channels or leak pathways as in a rat pheochromocytoma cell line (Bennett et al. 1998).

Mechanisms for the activation of the L-type Ca2+ channel during store depletion and refilling

Reduction of [Ca2+]i, which occurred during zero-Ca2+ superfusion or after a caffeine Ca2+ transient, was accompanied by membrane depolarisation (Fig. 7). These changes were recorded with both microelectrodes and patch electrodes, so that the Em changes were not an artifact of dialysis of the intracellular contents or stability of the patch seals. Such an effect has important implications as reduction of [Ca2+]i will depolarise the membrane and consequently favour Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels. Depolarisation during the undershoot following Ca2+ release may play a role in promoting store refilling as the time course of recovery from the undershoot was membrane potential dependent, and depolarisation facilitated the rate of recovery (Fig. 8). Conversely, Ca2+ influx would be reduced when the [Ca2+]i is high. One mechanism for this phenomenon is a reduction of outward current through Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels as spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) were abolished during zero-Ca2+ superfusion or the undershoot of caffeine and carbachol Ca2+ transients. This would favour membrane depolarisation as they contribute substantially to net membrane conductance.

The particular importance of this current in mirroring changes to [Ca2+]i and store refilling was evident in that the time courses for their recovery mirrored that for return of the [Ca2+]i to normal after the Ca2+ transient and the restitution time of the Ca2+ transients themselves. The STOC magnitude and frequency is sensitive to the local [Ca2+]i in the space immediately beneath the sarcolemma (Bolton & Imaizumi, 1996), and may be sensitive to the level of stored Ca2+, which can influence the release of Ca2+ into this sarcoplasmic space. The level of stored Ca2+ then could be represented by STOC activity. Consistent with this is the fact that a large STOC and membrane hyperpolarisation often preceded the peak of the Ca2+ transient, but that during the remainder of the transient STOC activity was greatly suppressed and a secondary membrane depolarisation occurred. This therefore suggests that intracellular Ca2+, particularly the [Ca2+]i in the ‘fuzzy space’ immediately adjacent to the sarcolemma, is importantly involved in regulating the BKCa channel and in turn the membrane potential. We propose that [Ca2+]i in the vicinity of the sarcolemma acts as a messenger for the functional SR content via Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Depletion of the store would lead to membrane depolarisation and Ca2+ entry via L-type Ca2+ channels.

In summary, the present study shows that the rise of intracellular [Ca2+] following activation of cholinergic receptors is independent of the membrane potential, but the opening of the L-type Ca2+ channels can be modulated by secondary effects on the membrane. The L-type Ca2+ channel plays an important role in refilling the functional intracellular Ca2+ stores, which would then influence normal detrusor contractile activity.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank The Wellcome Trust and St Peters's Trust for financial support.

REFERENCES

- Anderson L, Hoyland J, Mason WT, Eidne KA. Characterization of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone calcium response in single αT3–1 pituitary gonadotroph cells. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1992;86:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90141-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baro I, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. Changes of intracellular [Ca2+] during refilling of sarcoplasmic reticulum in rat ventricular and vascular smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1993;465:21–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss M, Wu C, Newgreen D, Mundy AR, Fry CH. A quantitative study of atropine-resistant contractions in human detrusor smooth muscle, from stable, unstable and obstructed bladders. Journal of Urology. 1999;162:1833–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DL, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Cheek TR. Ca2+ entry into PC12 cells initiated by ryanodine receptors or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Biochemical Journal. 1998;329:349–357. doi: 10.1042/bj3290349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton TB, Imaizumi Y. Spontaneous transient outward currents in smooth muscle cells. Cell Calcium. 1996;20:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourreau JP, Abela AP, Kwan CY, Daniel EE. Acetylcholine Ca2+ stores refilling directly involves a dihydropyridine-sensitive channel in dog trachea. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:C497–505. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.3.C497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourreau JP, Kwan CY, Daniel EE. Distinct pathways to refill ACh-sensitive internal Ca2+ stores in canine airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C28–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brading A. Physiology of bladder smooth muscle. In: Torrens M, Morrison JFB, editors. The Physiology of the Lower Urinary Tract. London: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 161–191. [Google Scholar]

- Brading AF, Mostwin JL. Electrical and mechanical responses of guinea-pig bladder muscle to nerve stimulation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;98:1083–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb12651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteels R, Droogmans G. Exchange characteristics of the noradrenaline-sensitive calcium store in vascular smooth muscle cells of rabbit ear artery. Journal of Physiology. 1981;317:263–279. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, van Breemen C. The superficial buffer barrier in venous smooth muscle: sarcoplamic reticulum refilling and unloading. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109:336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed KE, Ishikawa S, Ito Y. Electrical and mechanical activity recorded from rabbit urinary bladder in response to nerve stimulation. Journal of Physiology. 1983;338:149–164. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry CH, Gallegos CR, Montgomery BS. The actions of extracellular H+ on the electrophysiological properties of isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:71–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez A, Gimenez-Gallego G, Reuben JP, Roy-Contancin L, Feigenbaum P, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. Purification and characterization of a unique, potent, peptidyl probe for the high conductance calcium-activated potassium channel from venom of the scorpion Buthus tamulus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:11083–11090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich VYa, Isenberg G. Depolarization-mediated intracellular calcium transients in isolated smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig urinary bladder. Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:187–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich VYa, Isenberg G. Membrane potential modulates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ transients in guinea-pig coronary myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:35–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaschuk O, Yaari Y, Konnerth A. Release and sequestration of calcium by ryanodine-sensitive stores in rat hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Suzuki H. Electrical and mechanical responses produced by nerve stimulation in detrusor smooth muscle of the guinea-pig. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;284:177–183. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00386-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey NJ, Holden CP, Nath A, Geiger JD. Involvement of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-regulated stores of intracellular calcium in calcium dysregulation and neuron cell death caused by HIV-1 protein tat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73:1363–1374. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovou JW, Hill SJ, Birmingham AT. Agonist-induced contraction and accumulation of inositol phosphates in the guinea-pig detrusor: evidence that muscarinic and purinergic receptors raise intracellular calcium by different mechanisms. Journal of Urology. 1990;144:775–779. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen LJ, Sims SM. Emptying and refilling of Ca2+ store in tracheal myocytes as indicated by ACh-evoked currents and contraction. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:C877–886. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.4.C877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinder RB, Mundy AR. Pathophysiology of idiopathic detrusor instability and detrusor hyper-reflexia. An in vitro study of human detrusor muscle. British Journal of Urology. 1987;60:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishii K, Hisayama T, Takayanagi I. Comparison of contractile mechanisms by carbachol and ATP in detrusor strips of rabbit urinary bladder. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;58:219–229. doi: 10.1254/jjp.58.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockner U, Isenberg G. Action potentials and net membrane currents of isolated smooth muscle cells (urinary bladder of the guinea-pig) Pflügers Archiv. 1985;405:329–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00595685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda M, Komori S, Unno T, Ohashi H. Carbachol-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations in single smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig ileum. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:315–328. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Farley JM. Depletion and refilling of acetylcholine- and caffeine-sensitive Ca2+ stores in tracheal myocytes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1996;277:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi CA, Manzini S, Parlani M, Conte B, Giuliani S, Meli A. The effect of nifedipine on spontaneous, drug-induced and reflexly-activated contractions of the rat urinary bladder: evidence for the participation of an intracellular calcium store to micturition contraction. General Pharmacology. 1988;19:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(88)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, de Clerck I, Droogmans G, Plessers L, de Smedt H, Raeymaekers L, Casteels R. Agonist-dependent Ca2+ and Mn2+ entry dependent on state of filling of Ca2+ stores in aortic smooth muscle cells of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1990;427:171–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, de Smedt H, Droogmans G, Casteels R. Ca2+ release induced by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate is a steady-state phenomenon controlled by luminal Ca2+ in permeabilized cells. Nature. 1992;357:599–602. doi: 10.1038/357599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BSI, Fry CH. The action potential and net membrane currents in isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Urology. 1992;147:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostwin JL. Receptor operated intracellular calcium stores in the smooth muscle of the guinea pig bladder. Journal of Urology. 1985;133:900–905. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera L, McMurray G, Brading AF. The role of calcium stores in the action of muscarinic agonists on mammalian urinary bladder smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507:21–22P. [Google Scholar]

- Salapatek AMF, Lam A, Daniel EE. Calcium source diversity in canine lower esophageal sphincter muscle. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;287:98–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley GN. A comparison of spontaneous and nerve-mediated activity in bladder muscle from man, pig and rabbit. Journal of Physiology. 1984;354:431–443. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature. 1994;372:231–236. doi: 10.1038/372231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel W, Jainz M, Andreas K. Different potencies of dihydropyridine derivatives in blocking T-type but not L-type Ca2+ channels in neuroblastoma-glioma hybrid cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;342:339–345. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturek M, Kunda K, Hu Q. Sarcoplasmic reticulum buffering of myoplasmic calcium in bovine coronary artery smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:25–48. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui G, Wu C, Fry CH. Inward calcium currents in cultured and freshly isolated detrusor muscle cells: Evidence of a T-type calcium current. Journal of Urology. 2001;165:621–626. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breemen C, Cheng Q, Laher I. Superficial buffer function of smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Trends in Pharmacological Science. 1995;16:98–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88990-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman CP, McFadzean I, Gibson A, Tucker JF. Cellular mechanisms underlying carbachol-induced oscillations of calcium-dependent membrane current in smooth muscle cells from anococcygeous. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;121:1301–1308. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Bayliss M, Newgreen D, Mundy AR, Fry CH. A comparison of the mode of action of ATP and carbachol on isolated human detrusor smooth muscle. Journal of Urology. 1999a;162:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Fry CH. The effects of extracellular and intracellular pH on intracellular Ca2+ regulation in guinea-pig detrusor smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:131–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.131br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Fry CH. Na+/ Ca2+ excahnge and its role in intracellular Ca2+ regulation in guinea-pig detrusor smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2001;280:C1090–1096. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Sui G, Fry CH. Spontaneous action potentials and intracellular Ca2+ transients in human detrusor smooth muscle cells isolated from stable and unstable bladders. British Journal of Urology. 1997;80:164. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Sui G, Fry CH. Characterization of the spontaneous transient outward current in detrusor smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1999b;521:52P. [Google Scholar]