Abstract

To study the contribution of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to Ca2+ regulation and its interaction with the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) were measured in single, voltage clamped, smooth muscle cells. Increases in [Ca2+]c were evoked by either depolarisation (−70 mV to 0 mV) or by release from the SR by caffeine (10 mm) or flash photolysis of caged InsP3 (InsP3). Depletion of the SR of Ca2+ (verified by the absence of a response to caffeine and InsP3) by either ryanodine (50 μm), to open the ryanodine receptors (RyRs), or thapsigargin (500 nm) or cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 10 μm), to inhibit the SR Ca2+ pumps, reduced neither the magnitude of the Ca2+ transient nor the relationship between the influx of and the rise in [Ca2+]c evoked by depolarisation. This suggested that Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from the SR did not contribute significantly to the depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c. However, although Ca2+ was not released from it, the SR accumulated the ion following depolarisation since ryanodine and thapsigargin each slowed the rate of decline of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient. Indeed, the SR Ca2+ content increased following depolarisation as assessed by the increased magnitude of the [Ca2+]c levels evoked each by InsP3 and caffeine, relative to controls. The increased SR Ca2+ content following depolarisation returned to control values in approximately 12 min via Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity. Thus inhibition of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger by removal of external Na+ (by either lithium or choline substitution) prevented the increased SR Ca2+ content from returning to control levels. On the other hand, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger did not appear to regulate bulk average Ca2+ directly since the rates of decline in [Ca2+]c, following either depolarisation or the release of Ca2+ from the SR (by either InsP3 or caffeine), were neither voltage nor Na+ dependent. Thus, no evidence for short term (seconds) control of [Ca2+]c by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was found. Together, the results suggest that despite the lack of CICR, the SR removes Ca2+ from the cytosol after its elevation by depolarisation. This Ca2+ is then removed from the SR to outside the cell by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. However, the exchanger does not contribute significantly to the decline in bulk average [Ca2+]c following transient elevations in the ion produced either by depolarisation or by release from the store.

Diverse mechanisms regulate the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) to produce either contraction or relaxation in smooth muscle (Himpens et al. 1995; Horowitz et al. 1996; Bolton et al. 1999). Increases in [Ca2+]c and with it contraction are achieved by (a) Ca2+ influx via channels in the sarcolemma and/or (b) Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) by activation of InsP3 receptors (InsP3R) or ryanodine receptors (RyR). Ca2+ influx may be triggered by depolarisation which activates voltage-sensitive channels or by receptors via ligand-gated channels. In turn, Ca2+ influx itself may trigger Ca2+ release from the SR via RyR in the process of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) so amplifying the initial Ca2+ signal (Endo et al. 1970; see reviews by Fabiato, 1983; Jaggar et al. 2000). Yet, in smooth muscle, the role of CICR remains controversial. Although apparently contributing to [Ca2+]c in several smooth muscles such as portal vein, vas deferens and bladder (e.g. Grégoire et al. 1993; Burdyga et al. 1995; Kamishima & McCarron, 1997; Imaizumi et al. 1998; Bolton & Gordienko, 1998) other reports (e.g. in portal vein and gastric myocytes) deny any contribution from CICR, at least to the rise in [Ca2+]c produced by depolarisation (Guerrero et al. 1994; Fleischmann et al. 1996; Kamishima & McCarron, 1996; Kohda et al. 1997; White & McGeown, 2000).

Several mechanisms are also involved in restoring [Ca2+]c to resting levels (∼100 nm) in smooth muscle and with it relaxation. These include (a) the extrusion of Ca2+ via a sarcolemma Ca2+-ATPase pump, (b) the exchange of Ca2+ for Na+ by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in the sarcolemma, (c) the re-uptake of Ca2+ into the SR by a Ca2+-ATPase pump (SERCA) and (d) a uniporter for the uptake of Ca2+ into the mitochondria (see inter aliaMissiaen et al. 1991; Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1992; McCarron et al. 1994; Drummond & Fay, 1996; McCarron & Muir, 1999; Schmigol et al. 1999). The contribution of each may be substrate dependent and vary with both [Ca2+]c and smooth muscle type. Of these mechanisms, the role of the SR in Ca2+ removal (as in the elevation of [Ca2+]c) is again disputed. At steady state, release from the SR (e.g. by CICR) should be matched by Ca2+ uptake i.e. the store should contribute to Ca2+ removal (i.e. by uptake) after releasing the ion (Baró & Eisner, 1995; Kamishima & McCarron, 1998; ZhuGe et al. 1999; Schmigol et al. 2001). However following depolarisation, the uptake of Ca2+ into the store may proceed in the absence of prior Ca2+ release (Katsuyama et al. 1991; Kohda et al. 1997; Kamishima et al. 2000; White & McGeown, 2000). Since the SR is of finite capacity, its role in Ca2+ removal, in the absence of Ca2+ release, is thus difficult to understand. How then does the store contribute to Ca2+ removal? Presumably, as yet ill-defined mechanisms enable the store to clear the excess Ca2+ accumulated during depolarisation, to restore steady state [Ca2+] values.

Of the other mechanisms involved in Ca2+ removal, the role of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in smooth muscle is controversial (see review by Blaustein & Lederer, 1999) although this function in both cardiac (see reviews by Blaustein, 1988; Bers et al. 1996) and skeletal muscle (Gilbert & Meissner, 1982; see review by Gonzalez-Serratos et al. 1996) remains undisputed. In smooth muscle, two exchanger functions have been investigated; its contribution (a) to the maintenance of the SR Ca2+ content and (b) to the regulation of [Ca2+]c. The first possibility was based on the close anatomical apposition of the SR and exchanger in certain gastric and vascular smooth muscles (Moore et al. 1993; Juhaszova et al. 1994) and relied on evidence largely obtained from studies of the exchanger in reverse mode (Ca2+ entry) activity (e.g. Borin et al. 1994; Bychkov et al. 1997; Nazer & van Breeman, 1998a; Arnon et al. 2000; Ahn et al. 2001; Wu & Fry, 2001). Whether or not forward mode (Ca2+ extrusion) Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity decreased SR Ca2+ content is unclear. The second possibility arose from experiments in which the external [Na+] was lowered and the ensuing increases in tone and/or [Ca2+]c attributed to the presence of a functioning Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in either forward or reverse mode. Results from such ionic manipulations are difficult to interpret; alterations in extracellular [Na+] may have other effects beside that of altering exchanger activity - most notably changing the membrane potential.

Clearly our understanding of two of the principal mechanisms (the SR and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger) for Ca2+ regulation in smooth muscle is incomplete. Yet an understanding of both is a pre-requisite to understanding Ca2+ homeostasis. The present study addressed these problems. The role of both the SR and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in Ca2+ regulation have been examined following depolarisation in gastrointestinal muscle, where Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity and a role of the SR in Ca2+ removal have been proposed (Mueller & van Breemen, 1979; Romero et al. 1993; Ohata et al. 1996). To do this, the contribution to the overall rise in [Ca2+]c by CICR was first examined. Secondly, the importance of the SR in Ca2+ removal was determined and thirdly the role of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, which may operate independently or in conjunction with the SR, was explored. To investigate these problems, isolated myocytes were studied under voltage-clamp conditions to allow changes in Ca2+ transport arising from changes in membrane potential to be controlled and [Ca2+]c was simultaneously measured using fluo-3 or fura-2. Increases in [Ca2+]c were evoked either by releasing the ion from the store (using either caffeine or flash photolysis of caged InsP3) or by depolarisation to activate inward Ca2+ currents. The relationship between the Ca2+ current (ICa), the rise in [Ca2+]c and the velocity of the decline were examined before and after interventions to inhibit the uptake or release of Ca2+ from the SR. The voltage and external [Na+] dependence of the rate of [Ca2+]c decline were used to estimate the contribution of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to Ca2+ removal while measurement of the external [Na+] dependence of caffeine-evoked [Ca2+]c transients allowed a study of the exchanger's contribution to the maintenance of the SR Ca2+ content. The results showed that CICR did not contribute significantly to the depolarisation-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c and that this increase could be accounted for solely by Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma. However, the SR, but not the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, contributed to the removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol (despite the absence of release). This resulted in a substantially increased SR Ca2+ content which returned to pre-stimulus levels over a period of minutes by Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity. Preliminary observations have been presented (Bradley et al. 2001).

METHODS

From male guinea-pigs (500–700 g) stunned by a blow to the head and killed by exsanguination following the guidelines of the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, a segment of distal colon (∼5 cm) was removed and transferred to a Sylgard-coated (Dow Corning) Petri dish containing an oxygenated (95 % O2-5 % CO2) physiological saline solution of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 118.4, NaHCO3 25, KCl 4.7, NaH2PO4 1.13, MgCl2 1.3, CaCl2 2.7, and glucose 11 (pH 7.4). The circular muscle was dissected as far as possible from the longitudinal layer following removal of the mucosaand single cells prepared using a two-step enzymatic process as previously described (McCarron & Muir, 1999). The muscle was initially digested (30 min at 35 °C) with papain (1–4 mg ml−1) and dithioerythritol (0.5 mg ml−1) in a low Ca2+ solution containing (mm): sodium glutamate 80, NaCl 54, KCl 5, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 0.1, Hepes 10, glucose 10, and ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid 0.2 (EDTA, to remove heavy metals); the pH was adjusted at room temperature to 7.3 using NaOH. During a second incubation, the tissue was further digested (30 min at 35 °C) in the low Ca2+ solution containing in addition collagenase (type H or F; 1–3 mg ml−1), then rinsed several times with the enzyme-free low Ca2+ solution and then rinsed again in S-MEM (Eagle) spinner Ca2+-free medium (GibcoBRL). Single smooth muscle cells were dispersed by trituration with a Pasteur pipette, stored at 4 °C and used on the same day (McCarron & Muir, 1999).

Solutions

The extracellular solution used in the patch clamp experiments contained (mm): sodium glutamate 80, NaCl 40, tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) 20, MgCl2 1.1, CaCl2 3, Hepes 10 and glucose 30 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). When a Na+-free extracellular solution was used, NaCl and Na glutamate were each replaced with LiCl or choline chloride (120 mm; pH adjusted to 7.4 with LiOH). The pipette solution contained (mm): Cs2SO4 85, CsCl 20, MgCl2 1, Hepes 30, MgATP 3, pyruvic acid (sodium salt) 2.5, malic acid 2.5, NaH2PO4 1, creatine phosphate (disodium salt) 5, guanosine phosphate 0.5 (sodium salt), fluo-3 penta-ammonium salt 0.15 or 0.1 and caged InsP3 trisodium salt 0.05 (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Where fura-2 pentapotassium salt (0.05 mm) was used, fluo-3 penta-ammonium salt and caged InsP3 trisodium salt were omitted from the pipette solution. Low concentrations of chloride in the pipette and bathing solution, were used to minimise chloride currents.

Current recordings

Whole cell currents were amplified by an Axopatch-1D (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA), low pass signals were filtered at 500 Hz (8-pole Bessel filter; Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA, USA), and digitally sampled at 1.5 kHz using a Digidata interface, pCLAMP software (version 6.0.1, Axon Instruments) and Axotape (Axon Instruments) and stored for analysis.

Ca2+ measurements

Either fluo-3 or fura-2, introduced into the cell from the patch pipette, was used to measure [Ca2+]c. Fluorescence was measured using a microfluorimeter as described previously (McCarron & Muir, 1999). Excitation wavelengths (340 and 380 nm, 7 nm bandpass for fura-2 and 488 nm bandpass, 9 nm for fluo-3) were provided by a Delta Scan (Photon Technology Inc., London). The cell was illuminated every 10 ms for 8.5 ms at each wavelength (a complete 340 nm/380 nm ratio was obtained every 20 ms and [Ca2+]c measurements were thus made at 50 Hz (unless otherwise indicated). Background fluorescence, measured before cell membrane rupture, with the pipette attached to the cell, was subtracted from the fluorescence counts obtained during the experiments. With caged InsP3, the non-ratiometric Ca2+ indicator fluo-3 was used.

The Kd for fura-2 (280 nm) was determined from an in vitro calibration, as were Rmin and Rmax, which were decreased by 15 % to adjust for cell viscosity (Poenie, 1990). Fluo-3 fluorescence signals were expressed as ratios (F/F0 or ΔF/F0) of fluorescence counts (F) relative to control values before stimulation (F0). Where fluo-3 fluorescence signals were converted into [Ca2+]c (nm), the Kd for fluo-3 was 390 nm, Rmin was assumed to be 0 and Rmax was determined from in vitro calibrations (Cannell et al. 1994). Experiments were carried out mainly at room temperature (18–22 °C) to minimise ‘run-down’ but results were also verified at 35 °C as indicated in the text. Original fluorescence recordings were not filtered, smoothed or averaged except where indicated.

Intracellular Ca2+ was increased by depolarising the membrane, usually from a holding potential of −70 mV to 0 mV, or by caffeine (10 mm) applied by pressure ejection using a pneumatic pump (PicoPump PV 820, WPI, Herts, UK) or by the photorelease of caged InsP3. To photolyse caged InsP3 (referred to as InsP3 throughout the paper) the output of a xenon flash lamp (Optoelektronik, Hamburg, Germany) was passed through a UG-5 filter to select UV light and merged into the excitation light path of the microfluorimeter. The nominal flash lamp energy was 57 mJ (measured at the output of the fibre optic bundle) with a flash duration of about 1 ms.

Prior to the start of each experiment, cells were activated either by InsP3 or by caffeine every 60–120 s until responses of approximately constant magnitude were obtained (∼10–15 min). This was taken to indicate a steady SR Ca2+ content and consistent SR refilling. Where the effects of depolarisation on InsP3- or caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients were examined, the response (to InsP3 or caffeine) immediately before the depolarisation was used for the comparison.

Analysis of [Ca2+]c decline

The rate of the [Ca2+]c decline (d[Ca2+]c/dt) was measured as a function of [Ca2+]c. Due to noise inherent in the high temporal resolution of [Ca2+]c, the decline of the Ca2+ transient was smoothed by fitting polynomials to the data obtained, beginning with either the first data point after repolarisation or the first point after the peak of either the InsP3 or caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient. The polynomial (3rd to 9th order) fit to the data was selected by the highest r2 value. (Note r2, the coefficient of determination, represents the strength of linearity in a given relationship and is usually taken as a measure of the goodness of fit.) The derivative was obtained by averaging the slopes of two adjacent data points. In addition, percentage decay rates of the transient were used to determine changes in the rate of decline of the [Ca2+]c. The data were normalised to percentages of the overall decrease in [Ca2+]c after repolarisation. The times from 0 to 95 % decay (at 10 % intervals) were measured and plotted as a percentage decay against time from repolarisation.

When the effects of thapsigargin and ryanodine on the decline of [Ca2+]c were examined, the experiments did not begin until the drugs had been effective in inhibiting the responses to caffeine and InsP3.

The calculated and measured increase in [Ca2+]c due to ICa

The amount of Ca2+ estimated from the Ca2+ transient and measured by the Ca2+ indicator is termed ‘measured’ Ca2+ while that expected to arise from ICa is termed ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c. The latter was determined over the first 200 ms of the voltage clamp pulse using the following equation: ∫-ICadt/2FV where ∫-ICadt is total charge entry, F is the Faraday constant and V is the cell volume. ICa was integrated by measuring the area under the curve with reference to the current level after elimination of ICa with cadmium chloride (1 mm).

Calculation of the anticipated Na+-Ca2+ exchanger current

The magnitude of the anticipated current was calculated from the equation INa-Ca = DBFV, where D is the rate of [Ca2+]c decline (nm s−1), B is the buffer capacity (a dimensionless number), F is the Faraday constant (C mol−1) and V is the cell volume (in litres). The cell volume was calculated by measuring the lengths and breadths of ∼100 cells; each cell was represented as two cones attached together at the base and the volume calculated to be 2 pl. The buffer power of the cell was estimated (from the same experiments) from the relationship between the influx of Ca2+ (based on ICa) divided by the increase in ‘measured’ [Ca2+]i minus the baseline [Ca2+]i over the first 200 ms (assuming negligible attenuation of the signal by intracellular Ca2+ sequestration).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. of n cells and Student's t test was used to compare test and control conditions. Where data were normalised, a paired Mann-Whitney test was applied; P < 0.05 was considered significant. Microsoft Excel (Reading, UK) or Minitab (State College, PA, USA)statistical software were used. In experiments to determine the contribution of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to the regulation of the SR Ca2+ content, in 4 out of 13 cells the response to caffeine remained greater than 120 % of control 12 min after depolarisation. The basis for this was unclear and these experiments were rejected.

Drugs and chemicals

Fura-2 pentapotassium salt was purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, UK). Caged Ins(1,4,5)P3-trisodium salt, fluo-3 penta-ammonium salt, thapsigargin, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and ryanodine were purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (UK) Nottingham, UK). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK). Thapsigargin, CPA and ryanodine were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO, final bath concentration < 0.2 %). All other chemicals were dissolved in extracellular or pipette solutions as appropriate.

RESULTS

Depolarising pulses increased [Ca2+]c transiently (from a resting [Ca2+]c of 41 ± 5 nm to 227 ± 26 nm, n = 25, P < 0.001). This increase was inhibited by each of the Ca2+ channel antagonists, Cd2+ (1 mm, n = 12) and nimodipine (1 μm, n = 6) suggesting the presence of L-type Ca2+ channels in the sarcolemma. [Ca2+]c was also increased by InsP3 and by caffeine (10 mm), each of which released Ca2+ from the SR store (for InsP3 from 57 ± 8 nm to 264 ± 25 nm, n = 30; for caffeine from 56 ± 6 nm to 246 ± 23 nm, n = 40; P < 0.001; not shown).

The role of CICR in the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient

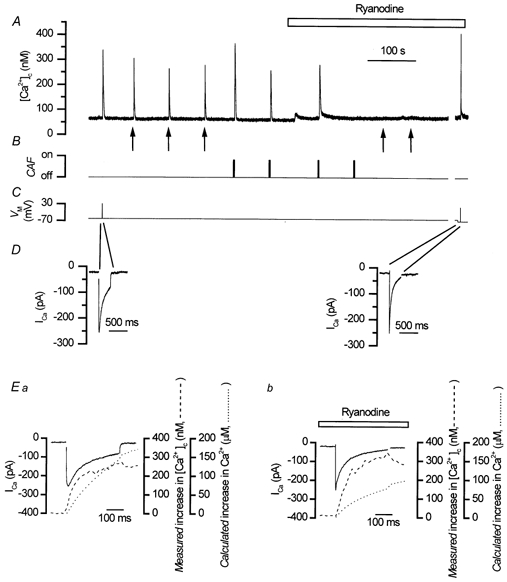

The SR was depleted of Ca2+ by caffeine (10 mm, sequentially applied at 1–2 min intervals) in the presence of ryanodine (50 μm; Fig. 1A). Caffeine increased [Ca2+]c (by 246 ± 23 nm, n = 21); this increase was significantly reduced by ryanodine (to an increase of 10 ± 4 nm; n = 21, P < 0.01). The decrease in the response to caffeine, by ryanodine could be explained by a fall in the SR Ca2+ content, a possibility assessed by examining the subsequent Ca2+ transients evoked by InsP3. After inhibition of the caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient, by ryanodine, the response to InsP3 (255 ± 38 nm, n = 19) was also inhibited (13 ± 5 nm, n = 19; P < 0.01; Fig. 1A) suggesting that the SR Ca2+ content had indeed decreased. In contrast, after this depletion, the [Ca2+]c increase in response to depolarisation was not decreased (234 ± 31 nm before and 347 ± 57 nm in ryanodine after caffeine; n = 21) but rather increased significantly (P < 0.05) even though ICa was comparable (261 ± 43 pA before and 222 ± 33 pA in ryanodine; n = 21, P = 0.07, Fig. 1D). The voltage pulse in the presence of ryanodine was adjusted to give a similar peak current to control (Fig. 1C) to compensate for ‘rundown’. These results suggest that, since the peak [Ca2+]c was not decreased, CICR was unlikely to have contributed to the [Ca2+]c rise during depolarisation.

Figure 1. Ryanodine-induced SR store Ca2+ depletion did not reduce the magnitude of depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients.

Depolarisation (C) triggered an inward Ca2+ current (ICa; D) and a Ca2+ transient (A). Caffeine (10 mm, B; CAF) and InsP3 (A, ↑) each produced Ca2+ transients (A). In the presence of ryanodine (50 μm), the responses to both caffeine (B) and InsP3 (A) were abolished (A); the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient (C) was not reduced (A). At the break in the record (∼3 min; A-C) several depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients in response to different voltages were investigated to match peak ICa amplitude in ryanodine to that of control (D and Ea and b). In Ea (control) and in Eb (in ryanodine, 50 μm) the time course of the ‘measured’ [Ca2+]c increase (dashed line) followed that of the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c (dotted line.; see Methods) over the period of the depolarisation. Depolarisation activated ICa (Ea, continuous line, control, −60 to +30 mV, and Eb, continuous line, in ryanodine, −70 mV to +15 mV; C and D). The amount of Ca2+ entering the cell, i.e. the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c, in both control (Ea, dotted line) and in ryanodine (Eb, dotted line) was sufficient (by 200-fold) to account for the ‘measured’ increase in [Ca2+]c (control Ea, dotted line, and in ryanodine Eb, dashed line). Ryanodine had no significant effect on the ‘measured’ [Ca2+]c (Eb, dashed line) but reduced the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c (Eb, dotted line). These results show that CICR did not contribute to the depolarisation-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c. A-E are components of the same experiment. Note the expanded time axis in D.

The contribution of CICR to the depolarisation-evoked [Ca2+]c increase was further explored by analysing the relationship between Ca2+ influx (i.e. the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c from the integral of ICa, see Methods) and the ‘measured’ Ca2+ increase indicated by fluo-3. To aid comparison between the ‘calculated’ and ‘measured’ [Ca2+]c the ‘calculated’ Ca2+ influx was expressed as the Ca2+ concentration (μm) which would result from influx of the ion, based on the cell volume and buffer power, rather than on the molar flux of ions. The ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c (87 ± 13 μm before and 69 ± 10 μm in ryanodine) significantly exceeded the ‘measured’ increase (after the baseline Ca2+ was subtracted; 183 ± 24 nm before and 329 ± 57 nm in ryanodine; Fig. 1E); the relationship between the two was not increased by ryanodine as would have been expected had CICR been operative. The rise in [Ca2+]c following depolarisation, therefore, could indeed be accounted for by the influx of Ca2+per se, without additional release from the SR and was increased rather than decreased when CICR was prevented with ryanodine (see also White & McGeown, 2000).

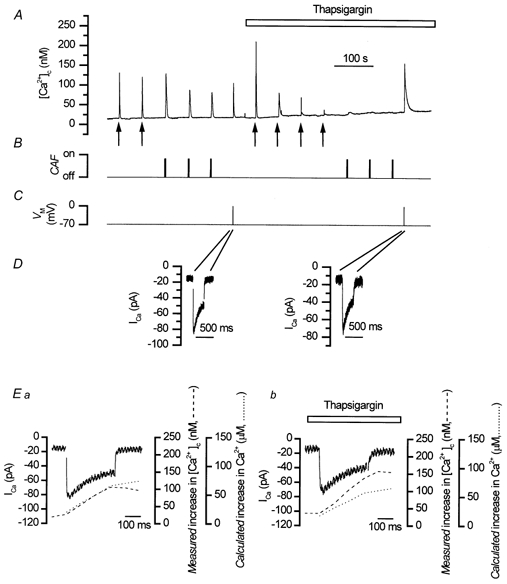

Further evidence for this view, came from experiments in which the SR was depleted of Ca2+ by inhibiting the activity of SERCA pumps by thapsigargin and by CPA. In the presence of thapsigargin (500 nm) the responses to caffeine and InsP3 were each reduced significantly, indicating that the SR had been depleted of Ca2+ (for caffeine 190 ± 59 nm before and 2 ± 2 nm in thapsigargin, n = 5; for InsP3 181 ± 39 nm before and 3 ± 2 nm in thapsigargin, n = 3; P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). In contrast, thapsigargin did not significantly reduce the rise in [Ca2+]c produced by depolarisation (208 ± 108 nm before and 172 ± 60 nm in thapsigargin, n = 5, P > 0.05; Fig. 2A) nor change the peak ICa (101 ± 21 pA before and 82 ± 20 pA in thapsigargin, n = 5; P > 0.05; Fig. 2D) significantly. However, the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c in both the presence and absence of the drug remained higher (38 ± 8 μm before and 31 ± 8 μm in thapsigargin) than the ‘measured’ [Ca2+]c (166 ± 72 nm before and 153 ± 56 nm in thapsigargin; n = 5; Fig. 2E) and the relationship between the two was not increased by thapsigargin (P > 0.05). This confirms the view that the Ca2+ entering the cell (as calculated from ICa) could itself adequately account for the rise in [Ca2+]c produced by depolarisation. Unlike the results obtained with ryanodine, however, the relationship between rise in [Ca2+]c following depolarisation and ICa was not increased by thapsigargin; the reason for the difference in [Ca2+]c amplitude between thapsigargin and ryanodine is unclear.

Figure 2. Thapsigargin-induced SR store Ca2+ depletion did not reduce the magnitude of depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients.

Caffeine (10 mm, B; CAF) and InsP3 (A, ↑) each evoked Ca2+ transients (A). Depolarisation (−70 mV to 0 mV, C) triggered ICa (D, note the expanded time axis) and a Ca2+ transient (A). Thapsigargin (500 nm), an inhibitor of SERCA pumps on the SR, abolished Ca2+ transients evoked by InsP3 (A) and caffeine (B, A) but not that evoked by depolarisation (which in some cells was increased) (A). In Ea (controls) and in Eb (thapsigargin) the time course of the ‘measured’ [Ca2+]c increase (dashed line) closely followed that of the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c (dotted line) over the duration of the depolarisation. ICa (control, Ea, continuous line; in thapsigargin, Eb, continuous line) was triggered by a depolarisation (−70 mV to 0 mV; C and D). The ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c was determined (during the first 200 ms of the depolarising pulse) from an integral of ICa. The amount of Ca2+ entering the cell, i.e. the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c in control (Ea, dotted line) and in thapsigargin (Eb, dotted line) was more than adequate (by 200-fold) to account for the ‘measured’ rise in [Ca2+]c (control, Ea, dotted line; and in thapsigargin, Eb, dashed line measured at 10 Hz). These results confirm that CICR does not contribute to the depolarisation-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c. A-E are components of the same experiment.

Similar results were obtained with CPA (10 μm). Responses to InsP3 and caffeine were significantly reduced in the presence of CPA, indicating that the store had been depleted (for InsP3 348 ± 137 nm before and 2 ± 2 nm in CPA, n = 4; for caffeine 367 ± 204 nm before and 5 ± 4 nm in CPA, n = 3; P < 0.05 in both cases). The depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient (206 ± 106 nm before and 432 ± 167 nm in CPA, n = 4, P > 0.05), and the peak ICa (261 ± 131 pA before and 227 ± 105 pA in CPA, n = 4, P > 0.05) were each unchanged by CPA. As with thapsigargin, the ‘calculated’ increase in [Ca2+]c (from ICa) remained higher (49 ± 11 μm before and 46 ± 11 μm in CPA) than the ‘measured’ Ca2+ (223 ± 95 nm before and 396 ± 129 nm in CPA, n = 4) and the relationship between the two was not increased by CPA (P > 0.05). Clearly, Ca2+ influx during depolarisation adequately accounted for the rise in [Ca2+]c observed over the same period, without resort to Ca2+ release from the SR.

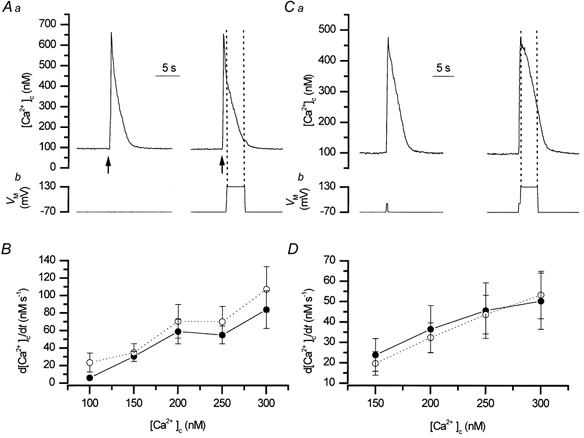

The role of the SR store in the removal of Ca2+ following depolarisation

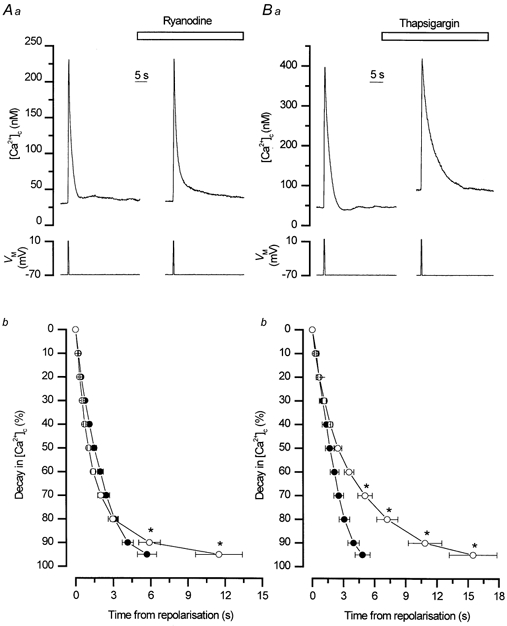

Although CICR did not contribute to the transient evoked by depolarisation, Ca2+ uptake by the SR may be a component of the mechanism for Ca2+ removal. Interestingly, the rate of decline of the transient in ryanodine, which disrupted SR function (Fig. 1), was slowed significantly compared to controls after the 90 % decay point (Fig. 3Aa) even though the amplitude of the transient was not decreased (Fig. 1). For example, the mean time for [Ca2+]c to decay by 95 % after repolarisation was 5.7 ± 0.7 s in control compared to 11.5 ± 1.8 s in ryanodine (n = 21, P < 0.01; Fig. 3Ab). Slowing of this latter phase of the decline of the transient, by ryanodine, suggests that the SR store contributed to the removal of [Ca2+]c by uptake following depolarisation. Similarly, when the SERCA pumps were inhibited with thapsigargin or CPA the rates of decline of Ca2+ transients were also slowed (Fig. 3Ba) although the amplitude was not decreased, i.e. there was no Ca2+ released during the depolarisation (Fig. 2). Thus the 90 % decay time after repolarisation was prolonged significantly in thapsigargin (4.0 ± 0.5 s before and 10.9 ± 1.6 s in thapsigargin, P < 0.05, n = 5; Fig. 3Bb) and in CPA (3.7 ± 1 s before and 8.6 ± 1.4 s in CPA, n = 4, P < 0.05). At 150 nm [Ca2+]c the rate of decline was 27 ± 4 nm s−1 in control and 14 ± 5 nm s−1 after SR Ca2+ had been blocked with thapsigargin (500 nm), whereas at 400 nm [Ca2+]c it was 142 ± 25 nm s−1 in control and 108 ± 11 nm s−1 after thapsigargin (500 nm). Together these results suggest that following depolarisation the SR accumulated, rather than released, Ca2+. Note that the test depolarisations in the presence of ryanodine, thapsigargin or CPA were only applied after the responses to caffeine and InsP3 had been inhibited (8–15 min; data not shown).

Figure 3. Ryanodine and thapsigargin each slowed the rate of decline of depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients.

Ryanodine (50 μm) slowed the rate of decline of depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients at the 95 % level (* P < 0.01) without significantly decreasing the amplitude (Aa). The mean percentage decay rates from 0 to 95 % for [Ca2+]c in the absence and presence of ryanodine are shown in Ab (n = 21). Inhibition of the SR store uptake by thapsigargin (500 nm) also slowed the decline of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient without decreasing its amplitude significantly (Ba). Thapsigargin was more effective than ryanodine especially at higher [Ca2+]c. The mean perecntage decay rates from 0 to 95 % for [Ca2+]c in the absence and presence of thapsigargin are shown in Bb (n = 5). The decline was slowed significantly from the 70 to the 95 % levels by thapsigargin (* P < 0.05). These results suggest that the SR removes Ca2+ from the cytosol following a depolarisation-evoked increase, particularly at lower Ca2+ concentrations. •, control; ○, drug treated.

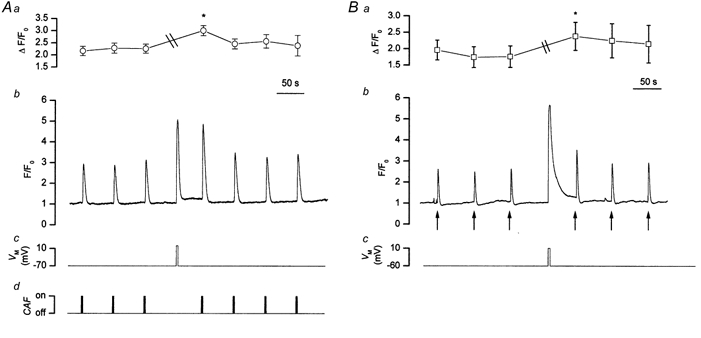

If the SR accumulated Ca2+, after a depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c, then the amplitude of a subsequent caffeine- or InsP3-evoked transient should increase. On the other hand, if CICR had contributed to the rise in [Ca2+]c during depolarisation, i.e. the SR was depleted, the amplitude of a subsequent caffeine- or InsP3-evoked Ca2+ transient would have been reduced. These alternatives were examined by comparing the magnitudes of the caffeine- and InsP3-evoked transients before and after depolarisation (Fig. 4). The Ca2+ transients were each increased significantly after depolarisation (for caffeine, 2.3 ± 0.2 F/F0 units above baseline before and 3.0 ± 0.2 F/F0 units above baseline after depolarisation n = 24, P < 0.01; Fig. 4A; for InsP3, 1.8 ± 0.3 F/F0 units above baseline before and 2.4 ± 0.4 F/F0 units above baseline after depolarisation; n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The possibility that these increases were due to a change in baseline [Ca2+]c, so affecting receptor sensitivity, was eliminated by applying linear regression analysis to the results. The percentage increases in the caffeine and InsP3 responses following depolarisation were compared with changes in baseline [Ca2+]c before and after depolarisation. There was no correlation between the two phenomena (r2 = 0.106 for experiments examining increases in the responses to InsP3, n = 6, and r2 = 0.182 for experiments examining increases in the responses to caffeine, n = 24) and it was concluded that the increase in the Ca2+ transients, produced by caffeine and InsP3, after depolarisation was due to an elevation in SR Ca2+ content.

Figure 4. Caffeine-evoked (A) and InsP3-evoked (B) Ca2+ transient amplitudes were each enhanced by prior depolarisation.

Caffeine (10 mm, CAF, Ad) and InsP3 (Bb, ↑) each evoked approximately reproducible Ca2+ transients (Ab and Bb; Ca2+ measurements were made at 10 Hz.). Depolarisation (3 s, −70 mV to 0 mV, Ac, or 3 s, −60 to +10 mV, Bc) increased [Ca2+]c (Ab and Bb). Following a depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c the caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient was increased to 174 % of that prior to depolarisation (Ab) and the InsP3-evoked Ca2+ transient to 145 % of that before depolarisation (Bb). Aa is a summary of the significant increase (* P < 0.01) in [Ca2+]c evoked by caffeine before and after depolarisation (n = 24) and (Ba) of that (* P < 0.05) evoked by InsP3 before and after depolarisation (n = 6). ‘\\’ indicates the time during which depolarisation-induced increases in [Ca2+]c occurred in both cases. The fluorescence ratio reached 2.9 ± 0.2 F/F0 units above baseline in Aa and 2.7 ± 0.6 F/F0 units above baseline in Ba and have been omitted from the figure to enable the caffeine and InsP3 responses to be followed more easily.

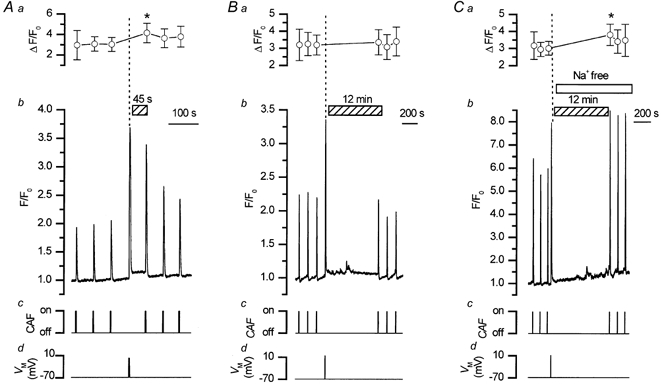

Contribution of the exchanger to Ca2+ removal following uptake into the SR

To maintain steady-state, the increased SR Ca2+ load produced following depolarisation must be restored to control levels by Ca2+ extrusion. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger may perform this role. This possibility was examined by investigating the time taken for the SR Ca2+ content to be restored to resting levels following depolarisation when forward mode activity of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger had been inhibited by replacement of external Na+. If the exchanger was involved in the removal of excess SR Ca2+, its inhibition would slow the restoration of the SR content to control levels. The amplitudes of caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients (an indication of the SR Ca2+ content) were determined, therefore, at different time intervals (45 s, 3 min, 6 min and 12 min) following depolarisation. These Ca2+ transients were increased significantly 45 s after depolarisation (141 ± 4 % of control; n = 29, P < 0.01), remained elevated for 3 min (151 ± 14 % of control; n = 7) and 6 min (142 ± 14 % of control; n = 5) but had returned close to control levels in most cells 12 min after depolarisation (110 ± 4 %; n = 26).

The contribution of the exchanger to restoring SR Ca2+ levels after depolarisation was then examined when its forward mode activity had been inhibited by removal of external Na+. In these experiments, the increase in store content was first assessed 45 s after depolarisation as measured by the increased magnitude of the caffeine-evoked transient. Then in the same cell, after the SR Ca2+ content had been restored to control values, the response to caffeine was again examined 12 min after the depolarisation. Finally when the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was inhibited by replacing Na+ with either Li+ or choline isosmotically in the bathing solution, the response to caffeine was examined again 12 min after the depolarisation. The results show that, in the presence of Na+, the store content which was elevated after 45 s returned to control within 12 min. However when Ca2+ removal by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was inhibited, the store content remained increased after the 12 min test period (Table 1 and Fig. 5). In a separate series of experiments carried out at 35 °C similar results were obtained (Table 2).

Table 1.

Effects of inhibition of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity on the SR Ca2+ content 45 s and 12 min after a depolarisation-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c at room temperature

| Changes in [Ca2+]c expressed as ΔF/F0 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %change in ΔF/F0 | ||||||||

| Caffeine before | Depolarisation | Caffeine 45 s after | Caffeine 12 min after | at 45s | at 12 min | n | P | |

| Na+ present | 3 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | — | 135 ± 5 | — | 9 | <0.01 |

| 3.2 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | — | 3.4 ± 0.7 | — | 100 ± 5 | 9 | > 0.05 | |

| Na+ replaced by LiCl | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | — | 142 ± 11 | — | 4 | < 0.01 |

| 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | — | 3.8 ± 0.6 | — | 121 ± 9 | 9 | < 0.05 | |

| Na+ present | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | — | 3.1 ± 0.3 | — | 106 ± 4 | 4 | > 0.05 |

| Na+ replaced by choline | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | — | 3.7 ± 0.6 | — | 165 ± 11 | 4 | < 0.01 |

The magnitude of responses to depolarisation (usually −70 mV to +10 mV) and caffeine (10 mM, in this and subsequent tables) before and 45s and 12 min after depolarisation are expressed as differences in the fluorescence ratio (ΔF/F0± s.e.m.) and as the percentage changes (± s.e.m.) in the magnitude of the responses to caffeine after depolarisation, with the caffeine response prior to depolarisation taken as 100%. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was inhibited immediately after the depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c, either by replacement of [Na+]o with LiCl or choline-Cl. P <0.05 was taken as significant. n, number of experiments.

Figure 5. Restoration of caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients, following depolarisation, was dependent on the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger.

Caffeine (10 mm; Ac, Bc and Cc, CAF) evoked approximately reproducible Ca2+ transients (Ab, Bb and Cb; Ca2+ measurements were made at 10 Hz). Depolarisation (−70 mV to +10 mV; Ad, Bd and Cd) also increased [Ca2+]c (Ab, Bb and Cb). Following depolarisation (45 s), the SR store had accumulated Ca2+, as indicated by the increased amplitude of the caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient (Ab) and the latter had returned close to control levels 12 min after the depolarisation (Bb). However, when external Na+ was replaced by Li+, so inhibiting forward mode activity of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, the caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient did not return to control levels within the 12 min period (Cb). Aa, Ba and Ca show summarised results of the changes in the fluorescence ratio (F/F0) above baseline produced by caffeine before and after depolarisation (perpendicular dotted line; all experiments were paired, n = 9; * P < 0.05). Clearly the SR Ca2+ content, as indicated by the Ca2+ transients evoked by caffeine, remains increased following depolarisation only when the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is inhibited, thus preventing the removal of Ca2+ from the cell suggesting that the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and the SR are involved in Ca2+ removal. Ab-d, Bb-d and Cb-d show results from three different cells.

Table 2.

Effects of inhibition of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity on the SR Ca2+ content 12 min after a depolarisation-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c at 35°C

| Changes in [Ca2+]c expressed as ΔF/F0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine before | Depolarisation | Caffeine 12 min after | % change | n | P | |

| Na+ present | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 77 ± 22 | 3 | > 0.05 |

| Na+ replaced by LiCl | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 2.4 | 5.0 ± 1.6 | 161 ± 6 | 3 | < 0.05 |

| Na+ replaced by choline Cl | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 141 ± 20 | 3 | < 0.05 |

The magnitude of responses to depolarisation (usually −70 mV to +10 mV) and caffeine before and 12 min after depolarisation are expressed as differences in the fluorescence ratio (ΔF/F0± s.e.m.) and as percentage changes (± s.e.m.) in the magnitude of responses to caffeine after depolarisation, with the caffeine response prior to depolarisation taken as 100%. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was inhibited immediately after the depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c either by replacement of [Na+]o with LiCl or choline-Cl. P < 0.05 was taken as significant. n, number of experiments.

The increase in the magnitude of the caffeine response following depolarisation could have been due to reverse mode exchanger activity thus increasing the SR Ca2+ content. This was not so; a 12 min period in Na+-free solution failed to significantly increase the Ca2+ transient evoked by caffeine (1.8 ± 0.1 F/F0 units above baseline compared to 1.7 ± 0.5 F/F0 units above baseline after 12 min in Na+-free solution, P > 0.05, n = 3).

The role of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in the regulation of the bulk [Ca2+]c

Following depolarisation

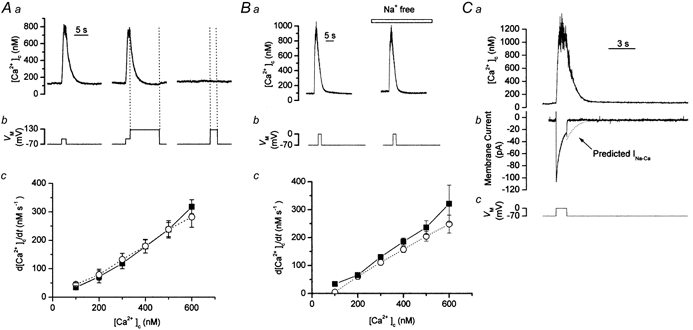

In the next series of experiments the contribution of the exchanger to regulating bulk average [Ca2+]c, as opposed to the SR Ca2+ content, was examined. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is voltage dependent (Reeves & Hale, 1984); its forward mode activity (efflux of 1 Ca2+ and influx of 3 Na+) can be inhibited by clamping at membrane potentials more positive than that of the equilibrium potential of the exchanger (ENa-Ca). However, at voltages negative to ECa (+130 mV at resting Ca2+ concentrations) Ca2+ may enter via channels. The rate of [Ca2+]c decline measured is the resultant of efflux and influx of the ion so that any influx will appear to slow the rate of decline. Therefore the effects of changing the membrane potential to one which allows Ca2+ influx will give the impression that the decline of [Ca2+]c is voltage dependent and may be misconstrued as evidence for exchanger activity. To overcome this, cells were clamped close to ECa (+130 mV) and the rate of decline of the Ca2+ transient compared to that at −70 mV, a membrane potential at which voltage-operated Ca2+ channels would be largely closed, negligible Ca2+ influx would occur and the driving force on the Ca2+ ion would encourage forward mode exchanger activity. In the event, there was no significant difference in the rates of decline of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients at either membrane potential (Fig. 6A; for example, at 400 nm [Ca2+]c the rates of decline were: controls, −70 mV, 178 ± 23 nm s−1, and at +130 mV, 179 ± 24 nm s−1; P > 0.05, n = 5).

Figure 6. The decline in [Ca2+]c following depolarisation was independent of both membrane voltage and extracellular Na+.

A, depolarisation from −70 mV to 0 mV (Ab) initially increased [Ca2+]c (measured using fura-2); this returned to resting levels on repolarisation (Aa). Clamping close to ECa (+130 mV, Ab) to inhibit exchanger forward mode did not change the rate of decline of the Ca2+ transient (Aa). The absence of a Ca2+ transient during a control pulse to +130 mV (included in each experiment) confirmed that ECa had been reached (Ab). Summarised data (Ac) showed no significant differences between the rates of decline of controls and when membrane voltage was clamped at +130 mV (n = 5) demonstrating that Ca2+ removal was voltage independent. ▪, control; ○, at +130 mV. Ba shows records of Ca2+ transients, evoked by depolarisation (−70 mV to 0 mV, Bb). Inhibition of exchanger forward mode activity by replacing external Na+ with Li+ (Na+ free) failed to alter the rate of decline of [Ca2+]c (Ba). The mean rates of decline (n = 5, Bc; ▪, control; ○, Na+ free) of [Ca2+]c were unchanged following substitution, indicating that the removal of Ca2+ was Na+ independent. C, depolarisation (−70 mV to 0 mV, C) raised [Ca2+]c (Ca) (fluorescence trace has been smoothed using a sliding boxcar average of three data points). Comparison of the measured current (Cb) with the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger current (INa-Ca) predicted for stoichiometric exchange of 3 Na+ ions for 1 Ca2+ ion (Cb, dotted line), indicated the absence of the latter which confirmed that the exchanger was not involved in removal of Ca2+ from the cytosol following depolarisation. The change in the level of noise in the current recording occurred because of a change in sampling from 1.5 kHz to 500 Hz.

As an alternative to clamping at +130 mV, forward mode activity was prevented by isosmotic replacement of extracellular Na+ with Li+ (as LiCl). At −70 mV, replacement of extracellular Na+ had no significant effect on the rate of decline of the Ca2+ transients caused by depolarisation (Fig. 6B; for example, at 400 nm [Ca2+]c, the rate of decline of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient was 186 ± 13 nm s−1 in control and 158 ± 11 nm s−1 in Na+-free solutions; P > 0.05, n = 5). Lack of involvement of the exchanger in [Ca2+]c removal, following depolarisation, was further supported from experiments which investigated the possible existence of an inward current which should accompany the decline of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient were the exchanger to be active (presuming an exchange stoichiometry of 3 Na+ ions for 1 Ca2+ ion), i.e. there would be a net movement of positive charge into the cell. In the event no such inward current was found (Fig. 6C).

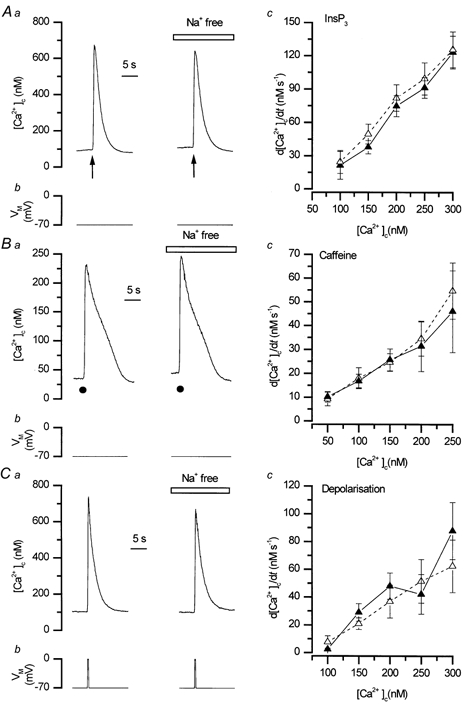

Following Ca2+ release from the SR by InsP3 or caffeine

The rates of decline of the Ca2+ transients evoked by either InsP3 or caffeine (for InsP3P > 0.05 and for caffeine P > 0.05; Fig. 7 and Table 3) were unaffected by inhibiting forward mode activity either by replacement of external Na+ by Li+ or by clamping the cell at +130 mV (P > 0.05, Fig. 7 and Fig. 8; Tables 3 and 4). The absence of voltage- and Na+-dependence, suggests that the exchanger does not contribute to Ca2+ removal following release of the ion from the store.

Figure 7. The rate of decline of the Ca2+ transient following Ca2+ release from the SR store was Na+ independent.

The rate of decline of the Ca2+ transients (measured using fluo-3; at 10 Hz) evoked by InsP3 (Aa, ↑) or by caffeine (10 mm, •, Ba) were unaffected by replacement of external Na+ by Li+ (Na+ free). The data for InsP3 and caffeine in the presence and absence of Na+ are summarised in Ac, n = 10 and Bc, n = 4–6 respectively. The rate of decline of Ca2+ transients evoked by depolarisation (Cb, −70 mV to 0 mV (Ca) and the corresponding summarised data (Cc, n = 6) also were unaffected by external Na+ substitution. ▴, control; ▵, Na+ free.

Table 3.

The effects of inhibiting Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity either by clamping at +130 mV or replacement of [Na+]o with LiCl on rates of decline in [Ca2+]c at room temperature

| InsP3 | Caffeine | Depolarisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | |

| Control | 70 ± 19 | 200 | 4 | — | — | — | 50 ± 14 | 300 | 3 |

| +130 mV | 59 ± 14 | 200 | 4 | — | — | — | 53 ± 12 | 300 | 3 |

| Control | 123 ± 15 | 300 | 10 | 31 ± 11 | 200 | 4 | 48 ± 10 | 200 | 6 |

| Na+ replaced by LiCl | 126 ± 16 | 300 | 10 | 35 ± 7 | 200 | 4 | 37 ± 12 | 200 | 6 |

Rates of decline (d[Ca2+]c/dt± s.e.m.) were measured at a given Ca2+ concentration (nM) of Ca2+ transients evoked by InsP3, caffeine and depolarisation. n, number of experiments. Depolarisation was usually from −70 mV to 0 mV.

Figure 8. The rate of decline of Ca2+ following release from the SR was voltage independent.

The rates of decline of the Ca2+ transients (measured using fluo-3; at 10 Hz) evoked by InsP3 (A, ↑) or depolarisation (from −70 mV to 0 mV; C) were unaffected when membrane voltage was clamped at +130 mV. B and D show summarised data (n = 4 and n = 3, respectively, control and at +130 mV). Inhibition of the exchanger by clamping at +130 mV did not affect the rate of removal of [Ca2+]c following Ca2+ influx or release from the SR. •, control (−70 mV); ○, +130 mV.

Table 4.

The effects of inhibiting Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity either by clamping at +130 mV or replacement of [Na+]o with LiCl on rates of decline in [Ca2+]c at 35°C

| InsP3 | Caffeine | Depolarisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | d[Ca2+]c/dt (nM s−1) | [Ca2+]c (nM) | n | |

| Control | 149 ± 48 | 200 | 4 | 64 ± 17 | 150 | 4 | 148 ± 14 | 200 | 3 |

| +130 mV | 153 ± 35 | 200 | 4 | 56 ± 15 | 150 | 4 | 123 ± 11 | 200 | 3 |

| Control | 169 ± 29 | 150 | 3 | 59 ± 22 | 150 | 3 | 157 ± 32 | 200 | 3 |

| Na+ replaced by LiCl | 158 ± 47 | 150 | 3 | 85 ± 43 | 150 | 3 | 144 ± 79 | 200 | 3 |

Rate of decline (d[Ca2+]c/dt ± s.e.m.) at a given Ca2+ concentration (nM) of Ca2+ transients evoked by InsP3, caffeine and depolarisation. n, number of experiments. Depolarisation was usually from −70 mV to 0 mV.

The role of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in Ca2+ accumulation (i.e. reverse mode)

When forward mode exchanger activity is inhibited, operation in reverse mode (efflux of 3 Na+ and influx of 1 Ca2+) could increase [Ca2+]c (Ozaki & Urakawa, 1981; Aickin et al. 1984; Ashida & Blaustein, 1987; Aaronson & Benham, 1989). Examination of this possibility by comparing [Ca2+]c in the presence and absence of external Na+ revealed that resting [Ca2+]c did not differ significantly (112 ± 8 nm in the presence and 111 ± 9 nm in the absence of external Na+, n = 9, P > 0.05). The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, in either forward or reverse mode, was clearly not involved directly in the regulation of bulk average [Ca2+]c but may contribute to accumulation of Ca2+ by the SR store when in reverse mode (Aaronson & van Breeman, 1981; Ashida & Blaustein, 1987; Borin et al. 1994). To test this, forward mode activity was inhibited by the removal of external Na+, and the effect of reverse mode activity on InsP3- and caffeine-evoked transients were each examined. No significant increases in the magnitude of the InsP3- or caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients were observed (for InsP3, control 415 ± 44 nm; in Na+-free solution 474 ± 60 nm, n = 6, P > 0.05; for caffeine, control 240 ± 38 nm; in Na+-free solution 280 ± 39 nm, n = 6, P > 0.05). This suggests that reverse mode activity does not regulate store content in colonic myocytes.

DISCUSSION

The contribution of both the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and the SR to Ca2+ homeostasis in smooth muscle has hitherto been unclear. The role of the SR may depend upon whether or not CICR (the process by which depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ entry triggers the release of Ca2+ from the SR) is present. Following CICR, the SR would presumably re-accumulate the ion to restore its [Ca2+] to pre-depolarisation levels (Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1992; Baró et al. 1993; Kamishima & McCarron, 1998, Schmigol et al. 1999). This may be accompanied by a fall in [Ca2+]c (Baró & Eisner, 1995) to maintain steady-state SR Ca2+ values. However, evidence suggests that this relationship may not be ubiquitous in smooth muscle. CICR is observed in some (Grégoire et al. 1993; Burdyga et al. 1995; Kamishima & McCarron, 1997), but not all (e.g. Fleischmann et al. 1996; Kamishima & McCarron, 1996; Kamishima et al. 2000) smooth muscles. Secondly, the present study has shown that the SR accumulates Ca2+, following depolarisation, despite the lack of CICR, i.e. in the absence of release. In consequence, the SR Ca2+ content would exceed resting levels, i.e. steady-state SR Ca2+ conditions would initially not apply. Support for this role of the SR in Ca2+ control is evident from the present findings, namely, (1) substantial depletion of the SR Ca2+ content (by ryanodine, CPA or thapsigargin) was unaccompanied by any reduction in the amplitude of the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient, i.e. there was no release (CICR) and Ca2+ influx alone accounted for the transient; (2) despite this, inhibition of SR Ca2+ uptake slowed the rate of [Ca2+]c decline suggesting that the SR accumulated the ion; (3) the significant increase in the SR Ca2+ content was verified by the increased magnitude of both the InsP3- and caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients; (4) the SR [Ca2+] was restored to resting levels by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, inhibition of which, by removal of external Na+, prevented this; and (5) in contrast, the exchanger did not contribute to the rate of decline of [Ca2+]c following depolarisation-evoked increases. Together these results suggest that the SR and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, acting in series, maintain steady-state conditions within guinea-pig colonic myocytes. Where Ca2+ uptake, following a depolarisation-evoked rise, caused SR store overload, Ca2+ content was restored and the excess Ca2+ removed, over time, by exchanger activity.

The key to the mechanism by which the SR and the exchanger together remove the elevated SR Ca2+ may lie in the proximity of the two structures to each other. In both arterial and gastric smooth muscle the exchanger is not randomly distributed on the sarcolemma but is restricted to regions in close apposition to the SR (Moore et al. 1993; Juhaszova et al. 1994), where concentrations of Na+ and Ca2+ may exceed bulk average values (Leblanc & Hume, 1990; see review by van Breeman et al. 1995). Despite the exchanger's low affinity for Ca2+ (DiPolo & Beaugé, 1983), this anatomical arrangement and the resulting ion gradients facilitate Na+-Ca2+ exchanger activity. The exchanger's low affinity for Ca2+ normally precludes its activation over the physiological range of [Ca2+]c and its contribution to Ca2+ removal. On the other hand, the SERCA pump has a high affinity for Ca2+, i.e. it is activated by low Ca2+ concentrations well within the physiological range (DiPolo & Beaugé, 1983; Kargacin & Fay, 1991; Grover & Khan, 1992; Kargacin, 1994). This arrangement could act like a two-stage pump to prime the SR and permit the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to extrude Ca2+ from the cell (Moore et al. 1993). In the present study, the SR store continued to accumulate Ca2+ from the cytoplasm when Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma had ceased. SR accumulation of Ca2+ which has entered during depolarisation appears not to rely on the close structural proximity of the SR to the sarcolemma but proceeds wherever [Ca2+]c is sufficiently adequate to activate the accumulation process. On the other hand, Ca2+ extrusion by the exchanger requires the close proximity of the SR to activate its low Ca2+ affinity mechanism.

This view of SR function differs from that of the ‘superficial buffer barrier’ hypothesis (see reviews by van Breeman & Saida, 1989; Chen & van Breeman, 1993; van Breeman et al. 1995), which proposes that Ca2+ accumulation depends on the close proximity of the SR to the sarcolemma (Sturek et al. 1992; Yoshikawa et al. 1996; Rembold & Chen, 1998; Asano & Nomura, 1999). The Ca2+, so accumulated, is extruded by the exchanger. It is unlikely in the ‘superficial buffer barrier’ hypothesis that Ca2+ accumulation by the SR can proceed where no contiguity between this structure and the sarcolemma exists (Miyashita et al. 1997; Nazer & van Breeman, 1998a,b). In the present proposal the close proximity of the SR with the sarcolemma is necessary for the extrusion of the ion rather than for its accumulation.

Besides regulating SR Ca2+, the exchanger may regulate bulk average [Ca2+]c in some (Ashida & Blaustein, 1987; McCarron et al. 1994; Zhu et al. 1994; McGeown et al. 1996; Nazer & van Breeman, 1998b; Wang et al. 2000) but not all smooth muscles (e.g. Droogman & Casteels, 1979; Mulvany et al. 1984; Janssen et al. 1997; Kamishima & McCarron, 1998). The present results failed to substantiate such a role. Thus, (a) inhibition of exchanger activity failed to affect the rate of Ca2+ removal from the cytosol following depolarisation, (b) no membrane current was seen during the decline of [Ca2+]c as would have been expected had the exchanger contributed to the removal of [Ca2+]c and (c) an increase in [Ca2+]c by its release from the SR by InsP3 or caffeine failed to activate the exchanger (see also Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1991). Clearly, the exchanger is not activated by a transient increase in bulk average [Ca2+]c, induced either by depolarisation or by release from the SR by caffeine or InsP3 either at room temperature or at 35 °C. It may be activated by Ca2+ released into the restricted space between the SR and the sarcolemma, for example, following overloading of the SR after depolarisation.

The SR, in addition, may contribute to [Ca2+]c uptake without direct participation of the exchanger. Indeed, the absence of exchanger activity when the SR Ca2+ content is at steady-state, suggests that, at least in the present study, uptake may precede SR/exchanger involvement in Ca2+ control. The significant slowing in the rate of decline of depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transients, either when SR Ca2+ uptake was inhibited (by thapsigargin or CPA) or the SR store rendered leaky by ryanodine, supports this view. The involvement of the SR in the removal of [Ca2+]c following depolarisation is complicated by CICR. Where CICR exists, SR involvement in Ca2+ removal might be anticipated since the SR store would be refilling (Ganitkevich & Isenberg, 1992; Baró et al. 1993; Kamishima & McCarron, 1998; Schmigol et al. 1999). That SR accumulation of Ca2+ should occur in the absence of CICR, as found in the present study, is therefore surprising (Kohda et al. 1997; Kamishima et al. 2000; White & McGeown, 2000).

Interestingly the SR contribution to [Ca2+]c decline, as assessed by the effects of thapsigargin and ryanodine on the depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ transient, increased as [Ca2+]c approached resting levels (Fig. 3). For example, at 150 nm [Ca2+]c the rate of decline was 27 ± 4 nm s−1 in control and 14 ± 5 nm s−1 after thapsigargin, whereas at 400 nm [Ca2+]c it was 142 ± 25 nm s−1 in control and 108 ± 11 nm s−1 after SR Ca2+ had been blocked with thapsigargin. At higher [Ca2+]c other removal mechanisms predominate; mitochondria, for example, provide up to 50 % of the total removed (> 500 nm [Ca2+]c; McCarron & Muir, 1999). Since neither the exchanger nor the SR Ca2+ pumps contribute significantly to removal at high [Ca2+]c (present study) and mitochondria contribute little to removal at low [Ca2+]c (e.g. ∼150 nm) the sarcolemma Ca2+ pumps appear to provide the balance. Thus Ca2+ removal by sarcolemma pump activity contributes to removal over the physiological [Ca2+]c range with significant contributions from the mitochondria at high and from the SR Ca2+ pump at low [Ca2+]c.

On the interrelationship between the [Ca2+]c, the SR and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger the present study has shown that depolarisation-evoked Ca2+ influx does not trigger Ca2+ release from the SR by CICR. Despite this, the SR contributes to the removal of [Ca2+]c following depolarisation by accumulating it so that an excess amount of Ca2+ enters the SR. The SR subsequently releases Ca2+ which is then removed from the cell by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger over a period of several minutes (see also Garashuk et al. 1997). In SR Ca2+ overload, following depolarisation, when the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was inhibited, repeated application of caffeine evoked Ca2+ transients of constant magnitude (an indication of the increased SR Ca2+ load). The magnitude of the caffeine response may be regulated by the gating of the ryanodine receptor rather than the SR Ca2+ content. The ryanodine receptors on the SR may adapt, as part of a negative feedback which controls the amount of Ca2+ released (Yasui et al. 1994; Sham et al. 1998; Györke, 1999). It is tempting to suggest that, even though there may be a large amount of Ca2+ available in the SR for release, at a high, local [Ca2+]c the ryanodine receptors’ open probability falls and so the bulk [Ca2+]c declines. Conversely, where the SR was not overloaded, i.e. after the 12 min control period in normal bathing solutions, the SR Ca2+ content rather than ryanodine receptor adaptation determined the magnitude of the caffeine-evoked response.

The question arises as to why the cell invests in an energy expensive process to accumulate excess Ca2+ into the SR when no mechanism for its release is apparently operative? One possibility is that SR loading increases spontaneous Ca2+ discharge, i.e. Ca2+ sparks (Nelson et al. 1995; ZhuGe et al. 2000) towards the sarcolemma. These may account for the hyperpolarising spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs; Benham & Bolton, 1986) at the sarcolemma. That is, the SR Ca2+ accumulation following depolarisation, may contribute to a negative feedback system that, by hyperpolarizing the sarcolemma, limits Ca2+ influx and helps to restore cell [Ca2+]c. In the present study, the SR Ca2+ content increased by approximately 30 % following depolarisation, presumably due to pump activity. Interestingly, in arterial smooth muscle, depending on vessel size, 20–50 % of Ca2+ entering the cell is spontaneously released from the SR, presumably towards the sarcolemma (see review by van Breeman et al. 1995). SR Ca2+ loading during depolarisation, therefore, could, via feedback, oppose activity. Furthermore, the Ca2+ released from the SR which produces STOCs is not re-accumulated (Stehno-Bittel & Sturek, 1992); it may be extruded by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (present results). Indeed, its low Ca2+ affinity may be well suited to this function; the local sarcolemma Ca2+ concentrations, as a result of store release, may reach 150 μm in some smooth muscle (Perez et al. 1999; ZhuGe et al. 2000). Clearly, in guinea-pig colonic myocytes, the exchanger has a highly specialised role in Ca2+ removal from the SR after a depolarisation-evoked rise in [Ca2+]c. The interplay between local ionic gradients and the structural alignment of organelles may be important in enabling the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to regulate Ca2+ store content in colonic smooth muscle.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (054328/Z/98) and the British Heart Foundation (PG/98108). J.McC. is a Caledonian Research Foundation Fellow. We would like to thank Mr John W. Craig for his excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Aaronson PI, Benham CD. Alterations in [Ca2+]i mediated by sodium-calcium exchange in smooth muscle cells isolated from the guinea-pig ureter. Journal of Physiology. 1989;416:1–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson PI, van Breeman C. Effects of sodium gradient manipulation upon cellular calcium, 45Ca fluxes and cellular sodium in the guinea-pig taenia coli. Journal of Physiology. 1981;319:443–461. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SC, Lee SJ, Goo YS, Sim JH, So I, Kim KW. Protein kinase C suppresses spontaneous, transient, outwards K+ currents through modulation of the Na/Ca exchanger in guinea-pig gastric myocytes. Pflügers Archiv. 2001;441:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s004240000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC, Brading AF, Burdyga TV. Evidence for sodium-calcium exchange in the guinea-pig ureter. Journal of Physiology. 1984;347:411–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon A, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP. Ouabain augments Ca2+ transients in arterial smooth muscle without raising cytosolic Na+ American Journal of Physiology. 2000;279:H679–691. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Nomura Y. Ca2+ buffering action on Bay K8644-induced Ca2+ influx in rat femoral arterial smooth muscle. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;366:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00858-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida T, Blaustein MP. Regulation of cell calcium and contractility in mammalian arterial smooth muscle: the role of sodium-calcium exchange. Journal of Physiology. 1987;392:617–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BararÓoacute; I, Eisner DA. Factors controlling changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration produced by noradrenaline in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1995;482:247–258. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BarÓ I, O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. Changes of intracellular [Ca2+] during refilling of sarcoplasmic reticulum in rat ventricular and vascular smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1993;465:21–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Bolton TB. Spontaneous transient outward currents in single visceral and vascular smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Journal of Physiology. 1986;381:385–406. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Bassani JWM, Bassani RA. Na-Ca exchange and Ca fluxes during contraction and relaxation in mammalian ventricular muscle. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;779:430–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP. Sodium/calcium exchange and the control of contractility in cardiac muscle and vascular smooth muscle. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1988;12:S56–S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:763–854. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton TB, Gordienko DV. Confocal imaging of calcium release events in single smooth muscle cells. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1998;164:567–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton TB, Prestwich SA, Zholos AV, Gordienko DV. Excitation-contraction coupling in gastrointestinal and other smooth muscles. Annual Review of Physiology. 1999;61:85–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borin ML, Tribe RM, Blaustein MP. Increased intracellular Na+ augments mobilization of Ca2+ from SR in vascular smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C311–317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.1.C311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KN, Flynn ERM, Muir TC, Craig JW, McCarron JG. Ca2+ store regulation by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) following depolarisation in guinea-pig colonic myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2001;80:1633. [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga TV, Taggart MJ, Wray S. Major difference between rat and guinea-pig ureter in the ability of agonists and caffeine to release Ca2+ and influence force. Journal of Physiology. 1995;489:327–335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov R, Gollasch M, Ried C, Luft FC, Haller H. Regulation of spontaneous transient outward potassium currents in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1997;95:503–510. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Spatial non-uniformities in [Ca2+]i during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1942–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, van Breeman C. The superficial buffer barrier in venous smooth muscle: sarcoplasmic refilling and unloading. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109:336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipolo R, BeaugÉ L. The calcium pump and sodium-calcium exchange in squid axons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1983;45:313–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.45.030183.001525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droogman G, Casteels R. Sodium and calcium interactions in vascular smooth muscle cells of the rabbit ear artery. Journal of General Physiology. 1979;74:57–70. doi: 10.1085/jgp.74.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond RM, Fay FS. Mitochondria contribute to Ca2+ removal in smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431:473–481. doi: 10.1007/BF02191893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Tanaka M, Ogawa I. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned skeletal muscle fibres. Nature. 1970;228:34–36. doi: 10.1038/228034a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. American Journal of Physiology. 1983;245:C1–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann BK, Wang Y-X, Pring M, Kotlikoff M. Voltage-dependent calcium currents and cytosolic calcium in equine airway myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:347–358. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich VYa, Isenberg G. Depolarisation-mediated intracellular calcium transients in isolated smooth muscle of guinea-pig urinary bladder. Journal of Physiology. 1991;435:187–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganitkevich VYa, Isenberg G. Caffeine-induced release and re-uptake of Ca2+ by Ca2+ stores in myocytes from guinea-pig urinary bladder. Journal of Physiology. 1992;458:99–117. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garashuk O, Yari Y, Konnerth A. Release and sequestration of calcium by ryanodine-sensitive stores in rat hippocampal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JR, Meissner G. Sodium-calcium ion exchange in skeletal muscle sarcolemmal vesicles. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1982;69:77–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01871244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Serratos H, Hilgemann DW, Rozyka M, Gauthier A, Rasgado-Flores H. Na-Ca exchange studies in sarcolemmal skeletal muscle. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;779:556–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire G, Loirand G, Pacaud P. Ca2+ and Sr2+ entry induced Ca2+ release from the intracellular Ca2+ store in smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein. Journal of Physiology. 1993;474:483–500. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover AK, Khan I. Calcium pump isoforms: Diversity, selectivity and plasticity. Cell Calcium. 1992;13:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(92)90025-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero A, Fay FS, Singer JJ. Caffeine activates a Ca2+-permeable, non-selective channel in smooth muscle cells. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:375–394. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Györke S. Ca2+ spark termination: Inactivation and adaptation may be manifestations of the same mechanisms. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;114:163–166. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himpens B, Missiaen L, Casteels R. Ca2+ homeostasis in vascular smooth muscle. Journal of Vascular Research. 1995;32:207–219. doi: 10.1159/000159095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Menice CB, Laporte R, Morgan KG. Mechanisms of smooth muscle contraction. Physiological Reviews. 1996;76:967–1003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi Y, Tori Y, Ohi Y, Nagano N, Atsuki K, Yamamura H, Muraki K, Watanabe M, Bolton TB. Ca2+ images and K+ current during depolarisation in smooth muscle cells of the guinea pig vas deferens and urinary bladder. Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:705–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.705bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2000;278:C235–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen LJ, Walters DK, Wattie J. Regulation of [Ca2+]i in canine airway smooth muscle by Ca2+ATPase and Na+/Ca2+ exchange mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:L322–330. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.2.L322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhaszova MA, Ambesi A, Lindenmayer GE, Bloch RJ, Blaustein MP. Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in arteries: identification by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence microscopy. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C234–242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.1.C234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamishima T, McCarron JG. Depolarization-evoked increases in cytosolic calcium concentration in isolated smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:61–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamishima T, McCarron JG. Regulation of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration by Ca2+ stores in single smooth muscle cells from rat cerebral arteries. Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:497–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.497bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamishima T, McCarron JG. Ca2+ removal mechanisms in rat cerebral resistance size arteries. Biophysical Journal. 1998;75:1767–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamishima T, Davies NW, Standen NB. Mechanisms that regulate [Ca2+]i following depolarisation in rat systemic arterial smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 2000;522:285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargacin G. Calcium signalling in restricted diffusion spaces. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:262–272. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargacin G, Fay FS. Ca2+ movement in smooth muscle cells studied with one-and two-dimensional diffusion models. Biophysical Journal. 1991;60:1088–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82145-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuyama H, Ito S, Itoh T, Kuriyama H. Effects of ryanodine on acetylcholine-induced Ca2+ mobilization in single smooth muscle cells of the porcine coronary artery. Pflügers Archiv. 1991;419:460–466. doi: 10.1007/BF00370789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda M, Komori S, Unno T, Ohashi H. Characterization of action potential-triggered [Ca2+]i transients in single smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig ileum. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;122:477–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Hume JR. Sodium current-induced release of calcium from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1990;248:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.2158146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron JG, Muir TC. Mitochondrial regulation of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and the InsP3-sensitive Ca2+ store in guinea-pig colonic smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1999;516:149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.149aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron JG, Walsh JV, Fay FS. Sodium/calcium exchange regulates cytoplasmic calcium in smooth muscle. Pflügers Archiv. 1994;426:199–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00374772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeown JG, Drummond RM, McCarron JG, Fay FS. The temporal profile of calcium transients in voltage clamped gastric myocytes from Bufo marinus. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:321–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, Wuytack F, Raemaekers L, Desmedt H, Droogmans G, Declerck I, Casteels R. Ca2+ extrusion across plasma membrane and Ca2+ uptake by intracellular stores. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1991;50:191–232. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90014-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y, Sollott SJ, Cheng L, Kinsella JL, Koh E, Lakatta G, Froehlich JP. Redistribution of intracellular Ca2+ stores after β-adrenergic stimulation of rat tail artery SMC. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:H244–255. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EDW, Etter EF, Philipson KD, Carrington WA, Fogerty KE, Lifshitz LM, Fay FS. Coupling of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, Na+/K+ pump and sarcoplasmic reticulum in smooth muscle. Nature. 1993;365:657–660. doi: 10.1038/365657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E, van Breemen C. Role of intracellular Ca2+ sequestration in b-adrenergic relaxtion of a smooth muscle. Nature. 1979;281:682–683. doi: 10.1038/281682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Aalkær C, Petersen TT. Intracellular sodium, membrane potential and contractility of rat mesenteric small arteries. Circulation Research. 1984;54:740–749. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazer MA, van Breeman C. Functional linkage of Na+-Ca2+ exchange and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release mediates Ca2+ cycling in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 1998a;24:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazer MA, van Breeman C. A role for the sarcoplasmic reticulum in Ca2+ extrusion from rabbit inferior vena cava smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1998b;274:H123–131. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.H123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata H, Kawanishi T, Hisamitsu T, Takahashi M, Momose K. Functional linkage of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger from stores in cultured smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig ileum. Life Sciences. 1996;58:1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki H, Urakawa N. Involvement of a Na-Ca exchange mechanism in contraction induced by low-Na solution in isolated guinea-pig aorta. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;390:107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00590191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Patlak JB, Nelson MT. Functional coupling of ryanodine receptors to KCa channels in smooth muscle from rat cerebral arteries. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:229–237. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poenie M. Alteration of intracellular fura-2 fluorescence by viscosity. A simple correction. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JP, Hale CC. The stoichiometry of the cardiac sodium-calcium exchange system. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259:7733–7739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rembold CM, Chen X-L. The buffer barrier hypothesis, [Ca2+]i homogeneity, and sarcoplasmic reticulum function in swine carotid artery. Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:477–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.477bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero F, Frediani-Neto E, Paiva TB, Paiva AC. Role of the Na+/Ca2+ exchange in the relaxant effects of sodium taurocholate on guinea-pig ileum smooth muscle. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1993;348:325–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00169163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmigol AV, Eisner DA, Wray S. The role of the sarcoplasmic reticulum as a Ca2+ sink in rat uterine smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 1999;570:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmigol AV, Eisner DA, Wray S. Simultaneous measurements of changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum and cytosolic [Ca2+] in rat uterine smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:707–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0707h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]