Abstract

Unlike fetal animals of lowland species, the llama fetus does not increase its cerebral blood flow during an episode of acute hypoxaemia. This study tested the hypothesis that the fetal llama brain maintains cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption by increasing cerebral O2 extraction rather than decreasing cerebral oxygen utilisation during acute hypoxaemia. Six llama fetuses were surgically instrumented under general anaesthesia at 217 days of gestation (term ca 350 days) with vascular and amniotic catheters in order to carry out cardiorespiratory studies. Following a control period of 1 h, the llama fetuses underwent 3 × 20 min episodes of progressive hypoxaemia, induced by maternal inhalational hypoxia. During basal conditions and during each of the 20 min of hypoxaemia, fetal cerebral blood flow was measured with radioactive microspheres, cerebral oxygen extraction was calculated, and fetal cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption was determined by the modified Fick principle. During hypoxaemia, fetal arterial O2 tension and fetal pH decreased progressively from 24 ± 1 to 20 ± 1 Torr and from 7.36 ± 0.01 to 7.33 ± 0.01, respectively, during the first 20 min episode, to 16 ± 1 Torr and 7.25 ± 0.05 during the second 20 min episode and to 14 ± 1 Torr and 7.21 ± 0.04 during the final 20 min episode. Fetal arterial partial pressure of CO2 (Pa,CO2, 42 ± 2 Torr) remained unaltered from baseline throughout the experiment. Fetal cerebral hemispheric blood flow and cerebral hemispheric oxygen extraction were unaltered from baseline during progressive hypoxaemia. In contrast, a progressive fall in fetal cerebral hemispheric oxygen consumption occurred during the hypoxaemic challenge. In conclusion, these data do not support the hypothesis that the fetal llama brain maintains cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption by increasing cerebral hemispheric O2 extraction. Rather, the data show that in the llama fetus, a reduction in cerebral hemispheric metabolism occurs during acute hypoxaemia.

The mammalian brain has a high metabolic rate and is considered to be more vulnerable to oxygen limitation than other organs. During pregnancy, the fetus is at greater risk of hypoxia than the adult since it is dependent not only on maternal cardiorespiratory but also on placental function for adequate oxygen delivery. Amongst the fetal strategies that minimise the adverse effects of oxygen deprivation, the most powerful for maintaining oxygen delivery to, and consumption by, the fetal brain, is a pronounced increase in cerebral blood flow (Cohn et al. 1974; Jones et al. 1981). In fact, in the sheep fetus cerebral blood flow matches the oxygen extraction in such a way that cerebral O2 consumption remains constant until relatively severe degrees of hypoxaemia, such as those associated with an ascending aortic oxygen content of ca 2.2 ml dl−1 (Field et al. 1990). In the sheep fetus, hypoxaemia below this level leads to a progressive fall in fetal cerebral oxygen consumption (Field et al. 1990) and values persistently below ∼50 % of basal cerebral O2 consumption result in cerebral damage, as evidenced by seizure activity (Ball et al. 1994) and/or neuronal death (Gunn et al. 1992; Parer, 1998).

The llama (Lama glama) is a species which has adapted to chronic hypobaric hypoxia and a number of physiological strategies enable it to thrive at altitudes surpassing 4000 m above sea level. Such strategies are genetically determined since they persist in llamas born and living at sea level, they include high affinity of the blood for oxygen (Moraga et al. 1996), efficient O2 extraction by the tissues (Banchero et al. 1971) and small red blood cells to increase surface area for O2 exchange (Lewis, 1976). Our previous studies have reported that during fetal life, unlike other animals such as the monkey (Jackson et al. 1987), the sheep (Cohn et al. 1974) and even the chicken (Mulder et al. 1998), the llama fetus does not show an increase in cerebral blood flow during an episode of acute hypoxaemia (Benavides et al. 1988; Llanos et al. 1993, 1995; Giussani et al. 1996, 1999; Llanos et al. 1998). Thus, in order to maintain cerebral O2 consumption during acute hypoxaemia, an increase in cerebral O2 extraction must occur in the llama fetus or a decrease in cerebral oxygen utilisation would be observed.

In this study cerebral hemispheric O2 extraction and consumption were calculated during basal and graded hypoxaemic conditions in the llama fetus to test the hypothesis that the fetal llama brain maintains cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption by increasing cerebral O2 extraction. In addition, blood flow distribution within the brain was measured to determine detailed regional differences in oxygen delivery to the fetal llama brain.

METHODS

Surgical preparation

Six pregnant llamas, born and raised in Santiago (586 m above sea level and third generation removed from the highlands), were studied in the Laboratory for Developmental Physiology and Pathophysiology at the Universidad de Chile at 217 days of gestation (2.86 ± 0.22 kg, mean ± s.e.m., where term is ca 350 days of gestation and 10.7 ± 0.7 kg, Fowler, 1989). The llamas were housed in an open yard with access to food and water ad libitum. The animals were familiarised with the study metabolic cage and laboratory conditions for 1–2 weeks prior to surgery.

After food and water deprivation for 24 h, polyvinyl catheters (i.d., 1.3 mm) were inserted into the maternal descending aorta and the inferior vena cava via a hindlimb artery and vein, respectively. This procedure was performed under ketamine anaesthesia (10 mg kg−1i.m.; Ketostop, Drag Pharma-Investic, Chile), with local infiltration of lidocaine (lignocaine) (1 % Dimecaina, Laboratorio Beta, Chile). The following day the fetuses were surgically prepared under maternal general anaesthesia (1 g sodium thiopentone, Tiopental Sódico, Laboratorio Astorga, Chile for induction and 1 % halothane in 50/50 O2 and N2O for maintenance). Following lower mid-line laparotomy, a fetal hindlimb was exposed through a small hysterotomy. Polyvinyl catheters (i.d. 0.8 mm) were inserted into the fetal descending aorta via a hindlimb artery and into the inferior vena cava via a hindlimb vein. A fetal forelimb was exposed through a second uterine incision and a catheter was inserted into the ascending aorta via the brachial artery. A sagittal venous sinus catheter was also inserted through a craniotomy (Field et al. 1990). Finally, a catheter was placed in the amniotic cavity for zero pressure reference and the uterine and abdominal incisions were closed. All vascular catheters were filled with heparinised (1000 IU ml−1) saline (0.9 % NaCl), plugged with a copper pin, exteriorised through an incision in the maternal flank and kept in a pouch sewn onto the maternal skin.

During surgery all animals were continuously hydrated with warm 0.9 % NaCl solution (15–20 ml kg−1 h−1) to compensate for any fluid loss. At the end of surgery, and daily after surgery for 5 days, 1 million units of penicillin (Penicilina G Sódica, Laboratorio Chile, Chile) and 500 mg kanamycin (Canamicina Sulfato, Laboratorio Chile, Chile) were administered in the amniotic fluid via the amniotic catheter. After surgery the animals were returned to the yard and an analgesic (Metamizol, 1 g i.m., Dipirona, Laboratorio Chile, Chile) was administered every 12 h for the next 2 days. At least 4 days of post-operative recovery were allowed before the beginning of the experiments. Vascular catheters were maintained patent by daily flushing with heparinised (200 IU ml−1) saline.

All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Medicine Animal Ethics Committee from the University of Chile. Furthermore, all animal procedures, maintenance and experimentation were conducted following the recommendations in the Guiding Principles for Research Involving Animals and Human Beings of the American Physiological Society, and the British Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986.

Experimental protocol

All experiments were based on a 2 h protocol: 1 h normoxaemia followed by 3 × 20 min periods of graded and progressive degrees of hypoxaemia. Following 1 h of the llama breathing room air, fetal hypoxaemia was induced by decreasing the maternal fraction of inspired O2 (FI,O2) to reduce the haemoglobin saturation in the fetal ascending aorta to between 45 and 35 % for the first 20 min period (H20), to between 35 and 25 % for the second 20 min period (H40), and to < 25 % for the final 20 min period (H60). Carbon dioxide (3–5 %) was added to the maternal inspired gas mixture during hypoxaemia to maintain the maternal and fetal arterial partial pressure of CO2 (Pa,CO2) relatively constant. After 1 h graded fetal hypoxaemia, the FI,O2 was returned to room air.

At 20 min intervals during the experimental period ascending aortic and sagittal sinus blood samples were taken from the fetus, and arterial blood samples were taken from the mother to measure pH, PO2 and PCO2 (BMS 3 Mk2 Blood Microsystem and PHM 73 pH/Blood Gas Monitor, Radiometer, Copenhagen, determinations measured at 39 °C), percentage saturation of haemoglobin (%sat Hb) and haemoglobin concentration (Hb) (OSM2 Hemoximeter, Radiometer, Copenhagen). Fetal and maternal arterial and venous pressures and amniotic fluid pressure were measured with strain gauge transducers (Statham P23Db, Hato Rey, Puerto Rico) and fetal and maternal blood pressures and heart rates were recorded continuously throughout the experiment on a Gilson ICM-5 polygraph (Gilson, Emeryville, CA, USA).

Experimental techniques

The fetal combined ventricular output and its distribution was measured during normoxaemia, and at H20, H40 and H60 using the radionuclide-labelled microsphere technique (Heymann et al. 1977). Beads of 15 μm diameter were used labelled with 57CO, 113Sn, 46Sc and 103Ru (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, USA). The beads were injected into the fetal inferior vena cava while reference samples were obtained from the ascending and descending aorta. The rate of withdrawal of the reference samples was 3.2 ml min−1 for 1.5 min. This method allows blood flow determination to all organs except the lungs (Heymann et al. 1977). A total of approximately 1 × 106 beads were injected at each measurement. On completion of the experiment the llama was anaesthetised with 1 g sodium thiopentone i.v. (Tiopental Sódico, Laboratorio Chile). A Caesarean section was performed, the fetus removed and injected with (1 g) sodium thiopentone i.v. Both mother and fetus were killed with saturated KCl injected i.v. whilst under anaesthesia.

At post-mortem the tip of the sagittal sinus catheter was found inside the vessel in all fetuses. No sagittal sinus thrombosis or cerebral cortex haemorrhage was found in any of the fetuses. The sagittal sinus was used for sampling cerebral venous drainage because contamination with venous blood from extra-cerebral tissues is negligible (Purves & James, 1969). As the sagittal sinus drains primarily the cerebral hemispheres, measurements made in the present study represent mainly cerebral hemispheric, instead of total cerebral, O2 extraction and consumption (Purves & James, 1969). The fetal brain and individual organs were removed and weighed. The fetal brain was separated into cerebral hemispheres (which included the midbrain and diencephalon), pons, medulla and cerebellum. All removed tissues were carbonised and radioactivity counted with a multi-channel gamma pulse height analyser (Minaxi 5000, Packard, Canberra, Australia). To ascertain adequate mixing of the microspheres, right and left cerebral hemispheres and right and left kidneys were counted separately. Microsphere mixing was considered adequate when the percentage differences in calculated blood flow to the right and left cerebral hemispheres and kidneys were < 10 %. Similarly, in order to attain adequate accuracy in the measurement of the regional blood flows, the number of microspheres in each organ or any area counted was > 400 (Heymann et al. 1977).

Blood flow to each region of the fetal brain was calculated by comparing the organ radioactivity with the flow rate and radioactivity of the ascending aortic reference sample. Blood flow to all other organs was calculated by comparing the organ radioactivity with the activity and flow rate of the appropriate reference sample (ascending aorta for upper body organs and descending aorta for lower body organs). Fetal combined ventricular output was calculated as the sum of blood flow to all organs except the lungs (Heymann et al. 1977) using the following equation:

where Q̇ is blood flow (expressed in ml min−1), and C is the radioactivity (measured in c.p.m.), and subscripts organ and reference denote the values for organs and references, respectively.

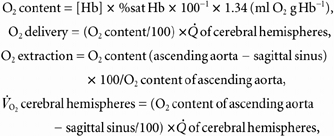

Vascular resistance in the cerebral hemispheres was calculated by dividing perfusion pressure (ascending arterial minus sagittal sinus venous pressure) by cerebral hemispheric blood flow. In addition, blood oxygen content (O2 content, expressed in ml O2 dl−1), cerebral hemispheric oxygen delivery (O2 delivery, expressed in ml O2 min−1 (100 g)−1), cerebral hemispheric oxygen extraction (O2 extraction, expressed in %) and cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption (V̇O2 cerebral hemispheres, expressed in ml O2 min−1 (100 g)−1) were calculated using the following equations:

|

where [Hb] is measured in g dl−1 and Q̇ of cerebral hemispheres is measured in ml min−1 (100 g)−1.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Changes in any measured variable during the experiment were assessed for statistical significance using ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05 (Zar, 1984).

RESULTS

Maternal and fetal blood gas status

During hypoxaemia, maternal arterial O2 tension, %sat Hb and O2 content decreased progressively during H20 (from 100 ± 8 to 60 ± 8 Torr, 99 ± 1 to 93 ± 4 % and 15.8 ± 0.7 to 13.9 ± 0.5 ml dl−1, respectively), H40 (to 39 ± 5 Torr, 79 ± 7 % and to 13.2 ± 0.5 ml dl−1, respectively) and H60 (to 30 ± 5 Torr, to 64 ± 7 % and to 11.2 ± 0.8 ml dl−1, respectively; all P < 0.05). Maternal arterial pH (7.44 ± 0.01) and PCO2 (35 ± 3 Torr) did not change significantly from baseline throughout the experiment.

Fetal blood gas and acid base status in the ascending aorta and sagittal venous sinus are shown in Table 1. The values in arterial blood in the basal period are similar to those obtained previously in chronically catheterised fetal llamas (Llanos et al. 1995). In the llama fetus there were significant progressive decreases in arterial and venous PO2, O2 content, %sat Hb and pH during the experiment (Table 1). While an increase in arterial levels of haemoglobin occurred, venous haemoglobin concentrations remained unchanged from baseline by the end of the hypoxaemia protocol in the llama fetus.

Table 1.

Systemic and sagittal sinus blood gas status in the fetal llama during graded hypoxaemia

| Basal | H20 | H40 | H60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic arterial blood gases | ||||

| pH | 7.36 ± 0.01 | 7.33 ± 0.01 | 7.25 ± 0.05*† | 7.21 ± 0.04*† |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 24 ± 1§ | 20 ± 1§ | 16 ± 1 | 14 ± 1 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 42 ± 2 | 40 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 40 ± 1 |

| Hb saturation (%) | 59 ± 4§ | 43 ± 2§ | 31 ± 3 | 19 ± 2 |

| Hb (g dl−1) | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 11.1 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 0.4§ |

| O2 content (ml O2 dl−1) | 8.2 ± 0.6§ | 6.3 ± 0.4§ | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| Sagittal sinus blood gases | ||||

| pH | 7.31 ± 0.01 | 7.31 ± 0.01 | 7.23 ± 0.04 | 7.17 ± 0.04*† |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 20 ± 1§ | 16 ± 1§ | 13 ± 1§ | 10 ± 1 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 44 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 42 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 |

| Hb saturation (%) | 39 ± 3§ | 24 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 |

| Hb (g dl−1) | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 11.1 ± 0.6 | 10.8 ± 0.6 | 11.7 ± 0.5 |

| O2 content (ml O2 dl−1) | 5.5 ± 0.3§ | 3.5 ± 0.4§ | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| Sagittal sinus arterio-venous difference in O2 content | ||||

| (Aa–Ss) O2 content (ml O2 dl−1) | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.3*† |

Hb, haemoglobin; (Aa–Ss), ascending aorta – sagittal sinus. Values are shown as means ± s.e.m. Measurements were made after 20 (H20), 40 (H40) and 60 (H60) min of hypoxaemia. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are

vs. Basal

vs. H20

vs. all.

The arterio-venous oxygen differences across the fetal cerebral circulation decreased from 2.8 ± 0.4 to 1.4 ± 0.3 ml O2 dl−1 after 60 min hypoxaemia (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Maternal and fetal cardiovascular responses

During hypoxaemia, there was a pronounced increase in maternal mean systemic arterial blood pressure (from 127 ± 6 to 160 ± 7 mmHg at H60, P < 0.05) and in maternal heart rate (from 45 ± 4 to 83 ± 9 beats min−1 at H60, P < 0.05). In the llama fetus, cardiac output and mean systemic arterial pressure, remained unaltered from baseline during the hypoxaemic protocol (Table 2). Although there was a tendency for heart rate to decrease, and for total vascular resistance to increase during acute hypoxaemia, these differences were not significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular responses to graded hypoxaemia in the fetal llama

| Basal | H20 | H40 | H60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 48 ± 2 | 47 ± 1 | 47 ± 3 | 49 ± 3 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1) | 126 ± 3 | 113 ± 12 | 118 ± 9 | 108 ± 6 |

| Cardiac output (ml min−1 kg−1) | 250 ± 13 | 252 ± 23 | 209 ± 7 | 199 ± 30 |

| Total vascular resistance (mmHg min kg ml−1) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

Values are shown as means ± s.e.m. Measurements were made after 20 (H20), 40 (H40) and 60 (H60) min of hypoxaemia.

Regional blood flow, resistance and oxygen delivery in the fetal llama brain

Blood flow and vascular resistance in the fetal brain (total), cerebellum and pons remained unchanged from baseline during each of the 20 min episodes of the hypoxaemia protocol (Table 3). In contrast, an increase in blood flow and a fall in vascular resistance occurred in the fetal medulla, which remained maintained during the entire hypoxaemia protocol (P < 0.05, Table 3). While a fall in oxygen delivery occurred in the fetal brain (total) by H40 and H60 (P < 0.05, Table 3), in the cerebellum, pons and medulla oxygen delivery was more or less maintained during the hypoxaemic protocol, falling significantly only at H60 (P < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Total and regional cerebral blood flows and oxygen deliveries in the fetal llama during graded hypoxaemia

| Basal | H20 | H40 | H60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood flow (ml min−1 (100 g)−1) | ||||

| Total brain | 83 ± 16 | 120 ± 14 | 106 ± 14 | 93 ± 16 |

| Cerebellum | 113 ± 21 | 157 ± 17 | 150 ± 17 | 144 ± 22 |

| Pons | 135 ± 26 | 193 ± 18 | 187 ± 25 | 174 ± 20 |

| Medulla | 147 ± 28 | 225 ± 22* | 224 ± 24* | 228 ± 35* |

| Vascular resistance (mmHg min (100 g) ml−1) | ||||

| Total brain | 0.64 ± 0.11 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.11 |

| Cerebellum | 0.46 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.07 |

| Pons | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.05 |

| Medulla | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.03* | 0.22 ± 0.02* | 0.23 ± 0.04* |

| Oxygen delivery (ml O2 min−1 (100 g)−1) | ||||

| Total brain | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 7.5 ± 1.0 | 4.8 ± 0.6§ | 2.7 ± 0.4§ |

| Cerebellum | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 9.9 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.5§ |

| Pons | 10.4 ± 1.1 | 12.1 ± 1.3 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 0.6§ |

| Medulla | 11.5 ± 1.3 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 0.8§ |

Values are shown as means ± s.e.m. Measurements were made after 20 (H20), 40 (H40) and 60 (H60) min of hypoxaemia. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are

vs. Basal

vs. all.

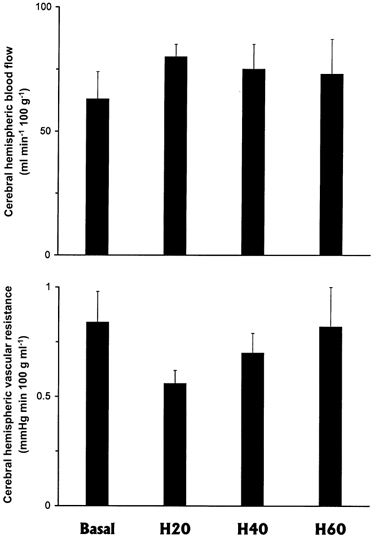

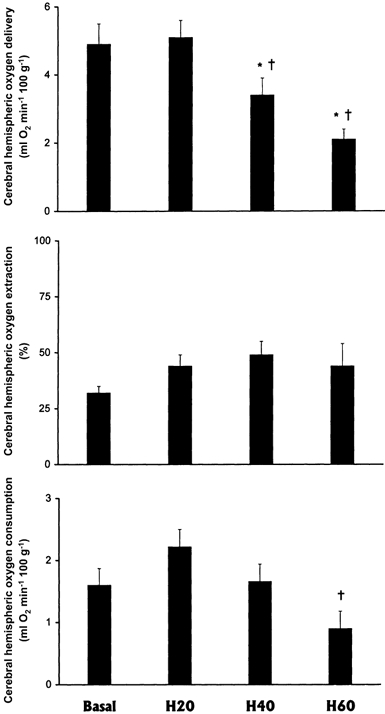

Measurements in the fetal cerebral hemispheres

Cerebral hemispheric blood flow and vascular resistance remained unaltered from baseline through each of the 20 min episodes of progressive hypoxaemia in the llama fetus (Fig. 1). The fall in oxygen delivery to the fetal cerebral hemispheres calculated by H40 and H60 (P < 0.05) was accompanied by a significant fall in cerebral hemispheric oxygen consumption at H60 (Fig. 2). However, cerebral oxygen extraction remained unaltered from baseline throughout each of the hypoxaemic periods in the llama fetus (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Cerebral haemodynamic responses to progressive hypoxaemia in the llama fetus.

Cerebral hemispheric blood flow (upper panel) and vascular resistance (lower panel) in the fetal llama during progressive hypoxaemia (means ± s.e.m., n = 6). Measurements were made after 20 (H20), 40 (H40), and 60 (H60) min of hypoxaemia.

Figure 2. Cerebral metabolic responses to progressive hypoxaemia in the llama fetus.

Cerebral hemispheric oxygen delivery, oxygen extraction and oxygen consumption in the fetal llama during progressive hypoxaemia(means ± s.e.m., n = 6). Measurements were made after 20 (H20), 40 (H40) and 60 (H60) min hypoxaemia. Significant differences (P < 0.05) are: * vs. Basal; † vs. H20.

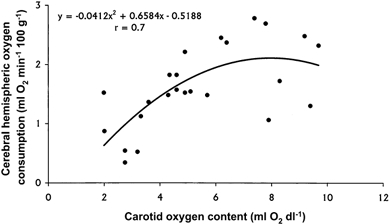

Figure 3. Relationship between cerebral hemispheres oxygen consumption and carotid oxygen content during progressive hypoxaemia in the llama fetus.

A plot of all individual values from all fetuses revealed a curvilinear relationship: cerebral V̇O2 = −0.0412x2 + 0.6584x − 0.5188; r = 0.7, P < 0.05.

A plot of all individual values from all fetuses for cerebral hemispheric oxygen uptake against carotid oxygen content revealed a curvilinear relationship (V̇O2 cerebral = −0.0412x2 + 0.6584x − 0.5188; r = 0.7, P < 0.05). The graph shows that below ca 7 ml O2 dl−1 in carotid oxygen content, a progressive fall in cerebral oxygen consumption occurs in the fetal llama cerebral hemispheres.

DISCUSSION

This study tested the hypothesis that the fetal llama brain maintains cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption by increasing cerebral hemispheric O2 extraction rather than decreasing cerebral hemispheric metabolism during acute hypoxaemia. The data presented do not support this hypothesis and show that cerebral oxygen extraction is maintained but a fall in cerebral hemispheric oxygen consumption occurs in the llama fetus during progressive episodes of hypoxaemia. Additional data presented in the study show that a pronounced redistribution of blood flow occurs in favour of the medulla within the fetal llama brain during hypoxaemia, and that cerebral hemispheric oxygen uptake cannot be maintained below ca 7 ml O2 dl−1 in carotid oxygen content in the llama fetus.

The mechanism by which fetal llamas withstand episodes of hypoxaemia differs from that found in fetal animals of lowland species, such as the sheep, in which cerebral oxygen consumption is maintained during hypoxaemia by an up to 3-fold augmentation in total cerebral blood flow in late gestation (Jones et al. 1977). An increase in cerebral blood flow, albeit to a lower extent (1.7-fold), also occurs at 0.68 gestation (Iwamoto et al. 1989). The increase in brain blood flow in the fetal sheep during acute hypoxaemia is general, such that a pronounced increase in blood flow occurs to all regions of the fetal sheep brain (Richardson et al. 1989). The pronounced increase in cerebral blood flow during acute hypoxaemia in the sheep fetus allows cerebral oxygen uptake to be maintained until ascending aortic blood oxygen content is approximately 2.2 ml dl−1 at 0.85 gestation (Field et al. 1990) and 3.3 ml dl−1 at 0.63 gestation (Gleason et al. 1990). Below this level of oxygenation, cerebral oxygen uptake falls in the fetal sheep brain. In marked contrast, cerebral blood flow does not increase in response to acute hypoxaemia in the fetal llama. This result was observed in both llama fetuses whose mothers were recently brought down from highland areas and in fetuses whose mothers were the third or fourth generation reared in lowland areas (Llanos et al. 1993, 1995, 1998; Giussani et al. 1996, 1999). The threshold for maintenance of cerebral hemispheric oxygen uptake appears much higher in the fetal llama brain than in the fetal sheep brain, as cerebral oxygen uptake in the llama brain could not be maintained below approximately 7 ml O2 dl−1 in the ascending aorta. The pronounced redistribution of blood flow within the fetal llama brain favouring the medulla during the greater part of the hypoxaemic challenge suggests that this area is important in cardiovascular control during acute hypoxaemia in this species.

In fetuses of lowland mammalian species (Cohn et al. 1974; Jones et al. 1981; Jackson et al. 1987) during late gestation, and in the chick embryo (Mulder et al. 1998) during late incubation, the increase in cerebral blood flow during acute episodes of hypoxaemia is mediated by a fall in cerebral vascular resistance. The fall in cerebral vascular resistance in most species studied to date results from a number of mechanisms (see Longo & Pierce, 1991) including decreased tissue oxygen (Jones et al. 1981) and increased tissue carbon dioxide (Rosenberg et al. 1982) levels, an increase in prostaglandins (Leffler et al. 1985), adenosine (Laudignon et al. 1990), arginine vasopressin (Pérez et al. 1989) and nitric oxide (Van Bel et al. 1995), and activation of potassium channels (Kleppisch & Nelson, 1995). In the llama fetus, all studies so far have reported that there is a differential contribution of the adrenergic, nitrergic and vasopressinergic systems to the maintenance of cerebral blood flow during normoxic and hypoxaemic conditions. While treatment of the llama fetus with a selective vasopressin V1 receptor antagonist did not alter blood flow or vascular resistance in the carotid circulation or in the cerebral hemispheres during basal or hypoxaemic conditions (Giussani et al. 1999; Herrera et al. 2000), treatment of the llama fetus with the α-adrenergic receptor antagonist phentolamine led to a pronounced fall in carotid blood flow and a pronounced increase in carotid vascular resistance even during basal conditions. Furthermore, treatment of the fetal llama with phentolamine during hypoxaemia led to severe systemic hypotension, circulatory collapse and fetal death (Giussani et al. 1999). When l-NAME, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor was administered to llama fetuses during normoxia, there was a substantial decrease in the carotid artery blood flow and a pronounced increase in the carotid artery vascular resistance (Riquelme et al. 1998). Treatment of the fetal llama with l-NAME during hypoxaemia led to no further modifications in carotid blood flow or carotid vascular resistance, but the elevated carotid vascular resistance was maintained high even 1 h after the end of the hypoxaemic episode (Riquelme et al. 1998). Combined, these results suggest that in the llama fetus the influence of AVP in regulating the cerebral blood flow is negligible, but that there are important adrenergic and nitrergic contributions to the maintenance of cerebral blood flow during normoxia and hypoxaemia in this species.

It could be argued that the lack of a cerebral vasodilator response to acute hypoxaemia reported in this study in the llama fetus may be attributed to the early gestational age at which these experiments were performed. However, a significant increase in cerebral blood flow during acute hypoxaemia in 0.58–0.68 gestation fetal sheep has been previously reported (Iwamoto et al. 1989), and it is known that an increase in cerebral blood flow and in cerebral oxygen extraction allow both immature and mature fetal sheep to maintain cerebral oxygen consumption during hypoxaemia (Gleason et al. 1990; Field et al. 1990).

In all species studied to date, cerebral metabolic rate and cerebral perfusion are closely coupled. For example, during fetal life, the increase in brain blood flow is closely associated with the increase in fetal brain growth during development (Szymonowicz et al. 1988; Richardson et al. 1989). Furthermore, cerebral blood flow is known to increase during REM-like low voltage states of electrocortical (ECoG) activity in fetal sheep, when an increase in cerebral oxidative metabolism occurs (Richardson et al. 1985). A previous study in the llama fetus reported close coupling between instantaneous changes in carotid blood flow and electrocortical states in the llama fetus, such that a switch in ECoG to low voltage was associated with a marked increase in carotid blood flow (Blanco et al. 1997). The intimate relationship between low voltage ECoG activity and vasodilatation in the carotid circulation in the llama fetus suggests that, as in other species, cerebral oxidative metabolism is also increased during REM-like electrocortical states, and that changes in carotid blood flow and in cerebral blood flow are coupled to cerebral metabolism in this species. Therefore, the fall in cerebral oxidative metabolism that occurs in the llama fetus during episodes of acute hypoxaemia reported in this study matches with the lack of an increase in cerebral blood flow during acute hypoxaemia in this species. These results also suggest that cerebral metabolic rate and cerebral perfusion are closely coupled under conditions of hypoxaemia in the llama fetus.

The fall in oxygen consumption in the fetal llama cerebral hemispheres during acute hypoxaemia reported in the present study may either reflect that the fetal llama is decompensating to the progressive degrees of hypoxaemia or that this species has evolved alternative strategies to withstand the period of cerebral oxygen deprivation. Physiological decompensation seems unlikely with carotid arterial PO2 values of ca 14 mmHg, as this level of arterial oxygenation is slightly lower than the PO2 found in llama fetuses in its usual habitat, at 4400 m above sea level (Llanos et al. unpublished observations). Combined, past and present data therefore favour the interpretation that the fetal llama brain undergoes hypometabolism under episodes of acute hypoxaemia. Such an adaptation has been previously reported in turtles (Pék-Scott & Lutz, 1998; Buck & Bickler, 1998), which, unlike mammals, are able to survive remarkably long periods of anoxia, and surprisingly also in Quechua Indians, indigenous people of South America with a prolonged residence ancestry at high altitude (Hochachka et al. 1994).

In conclusion, the data presented in this study do not support the hypothesis that the fetal llama brain maintains cerebral hemispheric O2 consumption by increasing cerebral hemispheric O2 extraction. Rather the data show that in the llama fetus, a reduction in cerebral hemispheric metabolism occurs during acute hypoxaemia. In addition, the data show that there is partial redistribution of blood flow within the fetal llama brain which favours the medulla during episodes of hypoxaemia. These responses reflect alternative strategies that the fetal llama has developed to avoid cerebral hypoxic damage, demonstrating powerful adaptations evolved in response to the chronic stimulus provided by the sustained hypobaric hypoxia of life at extreme altitude.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Carlos Brito and Juan Carlos Fuenzalida.This work was funded in Chile by FONDECYT No 1970236 and 1010636.

Dino Giussani is a Fellow of the Lister Institute for Preventive Medicine, UK.

REFERENCES

- Ball RH, Espinoza MI, Parer JT, Alon E, Vertommen J, Johnson J. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism in ovine fetuses during asphyxia resulting in seizures. Journal of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 1994;3:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Banchero N, Grover RF, Will JA. Oxygen transport in the llama (Lama glama) Respiration Physiology. 1971;13:102–115. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(71)90067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides CE, Pérezeacute;rez R, Espinoza M, Cabello G, Riquelme R, Parer JT, Llanos AJ. Cardiorespiratory adaptations to hypoxemia in the fetal llama. In: Jones CT, editor. Research in Perinatal Medicine, Fetal and Neonatal Development. VII. Ithaca, New York: Perinatology Press; 1988. pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco CE, Giussani DA, Riquelme RA, Hanson MA, Llanos AJ. Carotid blood flow changes with behavioral states in the late gestation llama fetus in utero. Developmental Brain Research. 1997;104:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck LT, Bickler PE. Adenosine and anoxia reduce N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor open probability in turtle cerebrocortex. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1998;201:289–297. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn HE, Sacks EJ, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Cardiovascular responses to hypoxemia and acidemia in fetal lambs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1974;120:817–824. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field DR, Parer JT, Auslender RA, Cheek DB, Baker W, Johnson J. Cerebral oxygen consumption during asphyxia in fetal sheep. Journal of Developmental Physiology. 1990;14:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler ME. Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids: Llama, Alpaca, Vicuña, Guanaco. Ames, IA, USA: Iowa State University Press; 1989. Reproduction; pp. 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Riquelme RA, Moraga FA, Mcgarrigle HHG, Gaete CR, Sanhueza EM, Hanson MA, Llanos AJ. Chemoreflex and endocrine components of cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxemia in the llama fetus. American Journal Physiology. 1996;271:R73–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.1.R73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Riquelme R, Sanhueza E, Hanson MA, Blanco CE, Llanos AJ. Adrenergic and vasopressinergic contributions to the cardiovascular response to acute hypoxaemia in the llama foetus. Journal of Physiology. 1999;515:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.233ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason CA, Hamm C, Jones MD. Effect of acute hypoxemia on brain blood flow and oxygen metabolism in immature fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:H1064–1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn AJ, Parer JT, Mallard EC, Williams CE, Gluckman PD. Cerebral histologic and electrocorticographic changes after asphyxia in fetal sheep. Pediatric Research. 1992;31:486–491. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera EA, Riquelme RA, Sanhueza EM, Gajardo C, Parer JT, Llanos AJ. Cardiovascular responses to arginine vasopressin blockade during acute hypoxemia in the llama fetus. High Altitude Medicine and Biology. 2000;1:175–184. doi: 10.1089/15270290050144172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann MA, Payne BD, Hoffman JIE, Rudolph AM. Blood flow measurements with radionuclide-labeled particles. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 1977;20:55–79. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(77)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Brown WD, Stanley C, Stone CK, Nickles RJ, Zhu GG, Allen PS, Holden JE. The brain at high altitude: hypometabolism as a defence against chronic hypoxia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1994;14:671–679. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BT, Piasecki GJ, Novy MJ. Fetal responses to altered maternal oxygenation in rhesus monkey. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252:R94–101. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.1.R94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MD, Sheldon RE, Jr, Peeters LL, Meschia GM, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL. Fetal cerebral oxygen consumption at different levels of oxygenation. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1977;43:1080–1084. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MD, Traystman RJ, Jr, Simmons MA, Molteni RA. Effects of changes in arterial O2 content on cerebral blood flow in the lamb. American Journal of Physiology. 1981;240:H209–215. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.2.H209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppisch T, Nelson MT. ATP-sensitive K+ currents in cerebral arterial smooth muscle: pharmacological and hormonal modulation. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H1634–1640. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudignon N, Farri E, Beharry K, Rex J, Aranda JV. Influence of adenosine on cerebral blood flow during hypoxic hypoxia in the newborn piglet. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1990;68:1534–1541. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.4.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler CW, Busija DW, Fletcher AM, Beasley DG, Hessler JR, Green RS. Effects of indomethacin upon cerebral hemodynamics of newborn pigs. Pediatric Research. 1985;19:1160–1164. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JH. Comparative hematology. Studies on camelidae. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 1976;55:367–371. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(76)90063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanos AJ, Riquelme RA, Espinoza MI, Gaete CR, Sanhueza EM, Cabello G, Moraga FA, Parer JT. Hipoxia: Investigaciones Básicas y Clínicas. Lima, Perú: UPCH Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia; 1993. Can the fetal llama successfully climb higher than mount Everest during hypoxia? pp. 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Llanos AJ, Riquelme RA, Moraga FA, Cabello G, Parer JT. Cardiovascular responses to graded degrees of hypoxaemia in the llama foetus. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1995;7:549–552. doi: 10.1071/rd9950549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanos A, Riquelme R, Sanhueza E, Gaete C, Cabello G, Parer J. Cardiorespiratory responses to acute hypoxemia in the chronically catheterized fetal llama at of gestation. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 1998;119:705–709. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(98)01008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo LD, Pearce WJ. Fetal and newborn cerebral vascular responses and adaptations to hypoxia. Seminars in Perinatology. 1991;15:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraga F, Monge C, Riquelme R, Llanos AJ. Fetal and maternal blood oxygen affinity: a comparative study in llamas and sheep. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1996;A115:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(96)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder ALM, van Golde JC, Prinzen FW, Blanco CE. Cardiac output distribution in response to hypoxia in the chick embryo in the second half of incubation time. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.281br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parer JT. Effects of fetal asphyxia on brain cell structure and function: limits of tolerance. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1998;A119:711–716. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(98)01009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PÉk-Scott M, Lutz PL. ATP-sensitive K+ channel activation provides transient protection to the anoxic turtle brain. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:R2023–2027. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PÉrez R, Espinoza M, Riquelme R, Parer JT, Llanos AJ. Arginine vasopressin mediates cardiovascular responses to hypoxemia in fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:R1011–1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.5.R1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves MJ, James IM. Observations on the control of cerebral blood flow in the sheep fetus and newborn lamb. Circulation Research. 1969;25:651–667. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BS, Patrick JE, Abduljabbar H. Cerebral oxidative metabolism in the fetal lamb: relationship to electrocortical state. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;153:426–431. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BS, Rurak D, Patrick JE, Homan J, Carmichael L. Cerebral oxidative metabolism during sustained hypoxemia in fetal sheep. Journal of Developmental Physiology. 1989;11:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme RA, Ferguson TA, Sanhueza EM, Giussani DA, Blanco CE, Hanson MA, Llanos AJ. 25th Annual Meeting of the Fetal and Neonatal Physiological Society. California, USA: Lake Arrowhead; 1998. Nitric oxide (NO) plays a major role in the recovery of the cardiovascular function after an episode of acute hypoxaemia in the llama foetus; 100 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg AA, Jones MD, Traystman RJ, Simmons MA, Molteni RA. Response of cerebral blood flow to changes in PCO2 in fetal, newborn, and adult sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;242:H862–866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.5.H862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymonowicz W, Walker AM, Cussen L, Cannata J, Yu VYH. Developmental changes in regional cerebral blood flow in fetal and newborn lambs. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;254:H52–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.1.H52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bel F, Sola A, Roman C, Rudolph AM. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of the cerebral circulation in the lamb fetus during normoxemia and hypoxemia. Biology of the Neonate. 1995;68:200–210. doi: 10.1159/000244238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 2. NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs; 1984. Multiple comparisons; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]