Abstract

We made whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal cells of hippocampal slices in combination with brief dendritic glutamate pulses to study the role of constitutive inwardly rectifying K+ channels (IRK, Kir2.0) and G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK, Kir3.0) in the processing of excitatory inputs. Phasic activation of GIRK channels by baclofen (20 μm) produced a reversible reduction of glutamate-evoked postsynaptic potentials (GPSPs), our equivalent of EPSPs, by about one-third. Conversely, tertiapin (30 nm), a selective inhibitor of GIRK channels, and Ba2+ (200 μm), a non-selective blocker of inwardly rectifying K+ channels, enhanced GPSPs and, in voltage-clamp experiments, reduced the underlying K+ conductances, indicating a functionally significant background GIRK conductance, in addition to constitutive IRK channel activity. When examined after suppression of endogenous adenosinergic inhibition, using either adenosine deaminase or the selective A1 receptor antagonist, 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine, tertiapin failed to influence either the GPSPs or the inwardly rectifying K+ conductance. Voltage-clamp recordings from acutely isolated CA1 pyramidal cells not exposed to ambient adenosine exhibited no response to tertiapin, whereas Ba2+ was still capable of reducing hyperpolarizing inward rectification. Our data indicate that in hippocampal pyramidal cells, two components of the inwardly rectifying K+ conductance can be identified, which together exert a tonic modulation of excitatory synaptic input: one arises from constitutive putative IRK channels, the other is mediated by the background activity of GIRK channels that results from the tonic activation of A1 receptors by ambient adenosine.

A variety of voltage-dependent conductances located in the somatic and dendritic membrane of pyramidal cells have recently been shown to modulate the amplitude and shape of EPSPs and to influence the integration of synaptic events (Johnston et al. 1996; Magee, 2000). Several active ionic mechanisms have been identified that either amplify or attenuate EPSPs. Among those are voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca2+ currents, in particular the persistent Na+ current (INaP) and the T-type Ca2+ current, which enhance subthreshold EPSPs (Stuart & Sakmann, 1995; Lipowsky et al. 1996; Gillessen & Alzheimer, 1997; Urban et al. 1998). The transient (A-type) K+ current and the hyperpolarization-activated cation current, Ih, serve as counterparts, dampening and linearizing the excitatory input (Hoffman et al. 1997; Magee, 1998, 1999; Stuart & Spruston, 1998). The prominent role of dendritic conductances in the processing of EPSPs is underscored by the fact that with the apparent exception of INaP, all of the above conductances are expressed at higher densities in the dendrite than in the soma of pyramidal cells from the hippocampus and neocortex (Magee & Johnston, 1995; Hoffman et al. 1997; Magee, 1998). Recently, we have reported that this somatodendritic gradient also holds for G-protein-activated inward rectifier K+ (GIRK) channels, suggesting that this current is also prominently involved in signal integration (Takigawa & Alzheimer, 1999a).

We have now characterized the effect of GIRK channel activation on EPSP shape and compared it to the action of the constitutive inward rectifier K+ (IRK) channels. While the latter appear to be tonically active, the former display a minimal open probability in the absence of GIRK channel agonists (Yi et al. 2001). The list of substances capable of opening GIRK channels in a G-protein-dependent, membrane-delimited fashion comprises an impressively large number of neuromodulators including adenosine, GABA (acting on GABAB receptors), serotonin, dopamine, adrenalin, acetylcholine, opioids, and somatostatin (Sodickson & Bean, 1998; Yamada et al. 1998; Karschin, 1999). At the molecular level, GIRK channels are heterotetramers of the Kir3.0 (GIRK) subfamily of inwardly rectifying channels, whereas IRK channels are homo- or heterotetramers of the Kir2.0 (IRK) subfamily (Dascal, 1997; Yamada et al. 1998). Owing to the lack of selective channel blockers, it has not been possible so far to elucidate and compare the effects of IRK and GIRK channels on the integration of excitatory input. We have now used the novel peptide inhibitor tertiapin, which has been isolated from the venom of the honey bee, to study this question. Tertiapin blocks GIRK1 and GIRK4 channels with nanomolar affinity while having no effect on IRK1 channels, ATP-sensitive inwardly rectifying K+ channels or voltage-dependent K+ channels (Jin & Lu, 1998; Kitamura et al. 2000). Our data indicate that in addition to the phasic effects associated with agonist-induced GIRK current activation, both IRK and GIRK channels attenuate EPSPs in a tonic fashion. The prominent background activity of GIRK channels in the absence of exogenous agonists is attributable to an A1 receptor-mediated purinergic tonus in the nervous tissue.

METHODS

Slice preparation and acute dissociation

Using standard procedures, transverse hippocampal slices, 300 μm thick, were prepared from the brain of Wistar rats (2–3 weeks old), which were deeply anaesthetized with a ketamine-xylazine solution (1 ml kg −1 of K-113, RBI/Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) prior to decapitation. All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines, and with the approval of the Animal Care Committee at the University of Munich. After dissection, slices were incubated in warmed (35°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) for 25 min and then maintained at room temperature (21–24°C) in the same solution. ACSF was constantly gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2 and had the following composition (mm): NaCl 125, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 25, d-glucose 10 (pH 7.4). For electrophysiological measurements, individual slices were transferred to a recording chamber that was mounted on the stage of an upright microscope (Olympus BX50WI). The use of Dodt infrared gradient contrast in conjunction with a contrast-enhanced CCD camera (Hamamatsu) allowed us to identify the somata and dendritic processes of pyramidal cells in the hippocampal CA1 region. During experiments, slices were kept submerged in ACSF that was constantly exchanged by means of a gravity-driven superfusion system (flow rate 2–3 ml min−1).

Acutely isolated pyramidal cell somata of the hippocampal CA1 region were prepared using an established method of combined enzymatic-mechanical dissociation (Takigawa & Alzheimer, 1999a, b). Briefly, small pieces of slice tissue (1–2 mm2) were incubated for 90 min at 29 °C in standard bath solution (composition see below) containing 19 U ml−1 papain. After washing, tissue pieces were maintained in standard bath solution at room temperature. Before each recording session, individual tissue pieces were dissociated mechanically using Pasteur pipettes of increasingly smaller bore diameter. After dissociation, the cell suspension was immediately transferred to the recording chamber, which was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope equipped with Hoffman modulation optics.

Electrophysiological recordings

EPSP-like waveforms were evoked using short iontophoretic pulses of sodium glutamate (250 mm), which was applied focally onto the apical dendrite of CA1 pyramidal neurones (100–150 μm from the soma) by means of a new iontophoretic device with fast capacity compensation (MVCS-02C, npi, Tamm, Germany). Iontophoretic pulses 0.5–1 ms long were delivered at 0.2 Hz. Illustrated membrane potential responses to glutamate are averages of four consecutive sweeps. To functionally isolate the recorded neurone from the synaptic input arising in neighbouring neurones co-activated by glutamate pulses, experiments were always conducted in the presence of TTX (1 μm). The NMDA component of EPSPs was suppressed with D-APV (20 μm) to eliminate non-linearities due to NMDA receptor activation. Spontaneous IPSPs were abolished with bicuculline (10 μm). Electrophysiological signals obtained in the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique were recorded, amplified and analysed with the aid of an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, CA, USA) in conjunction with a Digidata 1200 interface and pCLAMP 6 software (Axon Instruments). All recordings were made at room temperature. Signals were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 3–5 kHz. Recording pipettes were filled with (mm): KMeSO4 130, KCl 10, MgCl2 2, EGTA 10, Hepes 10, Na2-ATP 2, Na-GTP 2 (pH 7.25–7.30) and had a resistance of about 5 MΩ. Voltage readings were corrected for liquid junction potentials.

Current signals from acutely isolated pyramidal cell somata recorded in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode were sampled at 3–5 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB) using an Axopatch 200 amplifier in conjunction with a TL-1 interface and pCLAMP 6 software (all from Axon Instruments). All recordings were made at room temperature. The standard bath solution was composed of (mm): NaCl 150, KCl 3, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, Hepes 10, d-glucose 10 (pH 7.4). After whole-cell access was established, inwardly rectifying K+ currents were investigated in an extracellular solution containing (mm): NaCl 85, KCl 60, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 2, Na-Hepes 5, Hepes 5, d-glucose 10, TTX 0.001 (pH 7.4). Patch pipettes were filled with (mm): potassium gluconate 135, Hepes 5, MgCl2 3, EGTA 5, Na2-ATP 2, Na-GTP 2 (pH 7.25, adjusted with KOH and Tris, final K+ 151 mm). Electrode resistance in the whole-cell configuration was 8–15 MV before series resistance compensation (75–80%). A remotely controlled, solenoid-operated Y-tube system was used for rapid substance application.

TTX and tertiapin were purchased from Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel), adenosine deaminase was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany), and all other substances were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis (t test or ANOVA, significance set at P < 0.05) was performed with the use of Origin (4.1) software.

RESULTS

The GABAB receptor agonist, baclofen, inhibits excitatory synaptic transmission at the Schaffer collateral- commissural pathway-CA1 pyramidal cell synapse at both the presynaptic and postsynaptic site, with only the latter resulting from GIRK channel activation (Lüscher et al. 1997). In order to separate the GIRK channel-mediated shunting of EPSPs from the presynaptic effects of baclofen, we functionally disconnected CA1 pyramidal cells by adding TTX (1 μm) to the bathing solution and used very brief iontophoretic glutamate pulses to the apical dendrite to mimic EPSP waveforms in the postsynaptic neurone (Fig. 1A). The mean amplitude of these glutamate-evoked postsynaptic potentials (GPSPs) at a resting membrane potential (RMP) of −80 mV was 10.9 ± 0.86 mV (n = 29). The inhibitory effect of baclofen (20 μm) on GPSPs is illustrated in Fig. 1B. On average, the peak amplitude of GPSPs evoked at a RMP of −80 mV was reduced to 71.7 ± 4.9% (n = 15) of the control value, in a reversible fashion. In order to maintain equal driving forces for GPSPs in the absence and presence of baclofen, the hyperpolarizing action of the compound was compensated for by appropriate DC injection through the whole-cell pipette. When the membrane potential was not held manually, baclofen hyperpolarized the neurones by −8.0 ± 0.4 mV (RMP under control conditions −69.8 ± 1.2 mV, n = 24). That the reduction by baclofen of GPSPs was indeed mediated by GIRK channel activation was demonstrated in experiments in which baclofen failed to affect GPSPs when applied in the presence of the GIRK channel blockers Ba2+ (200 μm, n = 5) or tertiapin (30 nm, n = 4) (data not shown). In the course of these experiments, we made the surprising observation that application of the blockers alone produced a significant amplification of GPSPs. As shown in Fig. 1C, the selective GIRK channel inhibitor, tertiapin (30 nm), caused a reversible enhancement of GPSPs to 114.8 ± 3.7% of control values (n = 7). Addition of Ba2+ (200 μm, n = 4), a non-selective blocker of inwardly rectifying K+ channels, to the tertiapin-containing bath solution further increased GPSP amplitude (Fig. 1D). Again, the RMP was held manually at −80 mV by DC injection to compensate for the depolarizing effect of tertiapin (5.0 ± 1.2 mV, control RMP −68.4 ± 2.8 mV, n = 12) or Ba2+ (7.4 ± 1.6 mV, control RMP −68.8 ± 1.7 mV, n = 9) that is observed under conditions where the membrane potential was allowed to change freely. Given the differential selectivity of the two channel blockers, these data suggest that GPSPs are tonically inhibited by both IRK and GIRK channels.

Figure 1. Attenuation and amplification of glutamate-evoked postsynaptic potentials (GPSPs) by activation or inhibition of inward rectifier K+ currents, respectively.

A, schematic drawing illustrating the recording conditions. Under visual control, an iontophoretic pipette filled with sodium glutamate was moved close to the apical dendrite of a CA1 pyramidal neurone at a distance of 100–150 μm from the soma. B, reversible reduction of GPSP by baclofen (20 μm). The resting membrane potential was held at −80 mV during measurement of GPSPs by means of DC injection through the recording pipette (glu = glutamate). The inset summarizes data from 15 experiments. C, tertiapin (30 nm) produced an enhancement of GPSPs (n = 7). D, application of Ba2+ (200 μm) in the presence of tertiapin revealed an additional component of the tonic inhibition of GPSPs (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Experiments in voltage-clamp mode demonstrated directly the blocking action of tertiapin and Ba2+ on a standing inwardly rectifying K+ current. From a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV, current responses to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage steps between −70 and–150 mV were measured under control conditions, in the presence of tertiapin alone and after further addition of Ba2+ (n = 4). As expected for channel blockers that discriminate between inwardly rectifying K+ currents and the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih), tertiapin, and more so Ba2+, reduced K+ channel-mediated hyperpolarizing inward rectification without affecting the time course of Ih activation (Fig. 2A). That the current blocked by tertiapin and Ba2+ was indeed mediated by K+ channels became evident when we constructed I–V curves by plotting the amplitude of the current responses measured at the end of the voltage step as a function of the command potential. The three curves illustrated in Fig. 2B were then subtracted subsequently from each other to directly obtain the I–V relationship of the tertiapin-sensitive (presumed GIRK) current and the barium-sensitive, tertiapin-insensitive (presumed IRK) current (inset of Fig. 2B). Under our recording conditions, both currents crossed the zero-current line very close to the calculated equilibrium potential of K+ (−96 mV). Consistent with previous experiments performed at a physiological K+ gradient (Okuhara & Beck, 1994; Sodickson & Bean, 1996), the I−V relationship of the K+ currents was almost linear within this voltage range.

Figure 2. Pharmacological separation of two components of standing inwardly rectifying K+ conductance.

A, from a holding potential of −80 mV, depolarizing and hyperpolarizing voltage steps were applied (inset). The left panel illustrates current responses under control conditions (black traces) and in the presence of tertiapin (30 nm, red traces). The right panel depicts current responses in the presence of tertiapin (same as on the left) and after further addition of Ba2+ (200 μm, green traces). Illustrated data are from a single experiment, but were split to better illustrate the differential effect of the two channel inhibitors. Each current trace is an average of four consecutive sweeps. B, current-voltage (I–V) curves were constructed from the data shown in A, with the currents measured at the end of each voltage step. The inset shows the I–V curves of tertiapin-sensitive (red) and barium-sensitive, tertiapin-insensitive K+ currents (green) obtained by subtraction of the I–V curve determined in tertiapin from the control curve and by subtraction of the I–V curve determined in tertiapin/Ba2+ from that determined in tertiapin alone, respectively. The dashed line indicates the zero-current level.

Whereas the effect of Ba2+ on GPSPs and hyperpolarizing inward rectification might be attributed to the inhibition of a constitutive inwardly rectifying K+ current, the similar, but less pronounced effect of tertiapin was puzzling, pointing to either tonic GIRK channel activation by a spontaneously released or formed neuromodulator, or some kind of intrinsic GIRK channel activity, or a combination of both. Since the excitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurones is under constant purinergic control (Dunwiddie, 1980; Dragunow, 1988; Haas & Greene, 1988; Alzheimer et al. 1993), ambient adenosine is a likely candidate to account, at least in part, for the background activity of GIRK channels through tonic activation of the A1 receptor subtype. We used two established strategies to release CA1 pyramidal neurones from purinergic inhibition. Firstly, we applied the adenosine degrading enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA, 10 μg ml−1) to remove ambient adenosine from the extracellular space. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, tertiapin failed indeed to further increase GPSPs when applied in the presence of ADA. Secondly, and more specifically, we employed 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX, 100 nm), a selective blocker of the A1 receptor subtype (Lohse et al. 1987). Since adenosine might also affect Ih (Pape, 1992), which is known to influence the shape of EPSPs (see Introduction), we performed the second series of experiments in the presence of ZD 7288 (40 μm), an established inhibitor of Ih (Harris & Constanti, 1995), to rule out any ambiguities arising from an attendant adenosinergic modulation of Ih. In agreement with previously published data, ZD 7288 produced a significant enhancement of GPSPs (Magee, 1999); this, however, did not abrogate the GPSP-increasing effect of DPCPX (Fig. 3B). Again, tertiapin failed to produce any further enhancement of GPSPs (Fig. 3B), indicating that the purinergic tonus is a prerequisite for the amplification of GPSPs by tertiapin.

Figure 3. Tonic G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channel activation is mediated by ambient adenosine.

A, application of the adenosine degrading enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA, 10 μg ml−1) enhanced the amplitude of GPSPs and abrogated the augmenting effect of tertiapin. Depicted is one of two identical experiments. B, cumulative bath application of ZD 7288 (40 μm), DPCPX (100 nm) and tertiapin (30 nm) revealed the relative contribution of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current, Ih, and adenosine-activated GIRK conductance to the shape of GPSPs. The inset summarizes data from five experiments, demonstrating the lack of effect of tertiapin after blockade of A1 receptors by DPCPX (D, 100 nm; Z = ZD 7288, T = tertiapin). C, current responses to a hyperpolarizing voltage step during cumulative drug application, as indicated by like numbers. D, current amplitudes were measured at the end of the voltage step and plotted as a function of the command potential. The inset summarizes data from four experiments after normalization to the current responses obtained under control conditions at the largest voltage step (C = control). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Recordings in voltage-clamp mode confirmed this finding in terms of changes in the underlying ion conductances (n = 4). As illustrated in Fig. 3C, D, ZD 7288 (40 μm) suppressed the slowly activating, Ih-dependent component of hyperpolarizing inward rectification. Subsequent addition of DPCPX reduced further the inward rectification by eliminating an apparently instantaneous current component, an effect that is mediated by inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Consistent with its effect in current-clamp recordings of GPSPs, the cocktail of ZD 7288 and DPCPX abrogated any effect of tertiapin on the neuronal I–V relationship.

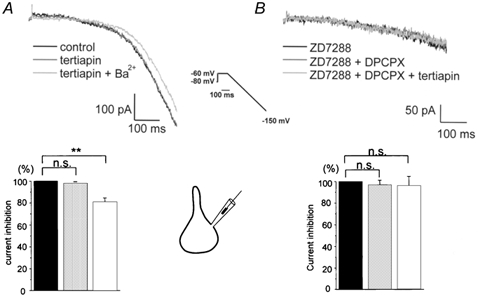

We examined next the effect of Ba2+ and tertiapin under conditions where pyramidal cells are not exposed to extracellular adenosine. For this purpose, we performed voltage-clamp recordings on acutely isolated CA1 pyramidal neurones that were continuously superfused with fresh solution to flush away any newly formed or released adenosine. To increase current flow through inwardly rectifying K+ channels, extracellular K+ was elevated to 60 mm and inward K+ current responses were evoked by hyperpolarizing voltage ramps, as reported previously (Takigawa & Alzheimer, 1999a). In contrast to its effect in the slice preparation, tertiapin now failed to affect the neurones' I–V relationship, whereas Ba2+ was still capable of reducing hyperpolarizing inward rectification by a significant percentage (Fig. 4A). Demonstrating the lack of tonic A1 receptor activation under these recording conditions, DPCPX (100 nm), again applied in the presence of ZD 7288, did not influence the hyperpolarizing current response (Fig. 4B). As expected from the previous experiments, when added to the mixture of ZD 7288 and DPCPX, tertiapin did not alter the current response.

Figure 4. Absence of tonic GIRK, but not IRK channel activity in acutely isolated CA1 pyramidal cells.

Hyperpolarizing voltage ramps in high extracellular K+ were used to evoke inward K+ current responses from pyramidal-shaped somata (insets between A and B). A, Ba2+(200 μm), but not tertiapin (30 nm), was capable of reducing inward rectification in a significant fashion, as indicated by the like-coloured columns of the histogram below current traces, which summarizes data from six experiments. Current amplitudes were measured at maximal hyperpolarization and normalized to control values. B, in the presence of ZD 7288 (40 μm), cumulative application of DPCPX (100 nm) and tertiapin (30 nm) failed to reduce inward rectification. The histogram with like-coloured columns was constructed as described in A, with the currents normalized to the response in ZD 7288 (n = 5). **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Using the GABAB receptor ligand baclofen as a GIRK channel agonist under conditions where its presynaptic action on transmitter release is eliminated, we found that activation of somatodendritic GIRK currents caused a considerable reduction in GPSP amplitude, presumably by shunting of the synaptic current en route to the soma. When evoked at a RMP of −80 mV, GPSPs, our equivalent of EPSPs in TTX-treated slices, were reduced by baclofen to 72% of control values. In a previous study, we observed a similar extent of GPSP reduction by the cholinergic GIRK channel agonist carbachol (Seeger & Alzheimer, 2001), suggesting that several agonists are likely to target GIRK channels to influence the somatodendritic processing of synaptic inputs. Firing of local GABAergic interneurones as well as activity of cholinergic, serotonergic or adrenergic projection fibres will thus cause a phasic attenuation of synaptic potentials in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Our study does not allow us to determine the relative contribution of dendritic versus somatic sites to the GIRK channel-mediated reduction of GPSPs. However, we have reported previously that local activation of GIRK channels at various sites along the apical dendrite always led to a significant reduction of EPSPs, indicating that dendritic GIRK channels alone are capable of producing considerable shunting of synaptic current as it is propagated towards the soma (Seeger & Alzheimer, 2001). Owing to the prominent dendritic localization of both the GIRK channels and the receptors they are coupled to (Takigawa & Alzheimer, 1999a), GIRK channel activation might thus modulate the processing of postsynaptic potentials in a spatially restricted fashion, depending upon the dendritic sites where the coupling occurs. Based on immunohistochemical evidence, some dendritic GIRK channels appear to be located in close proximity to postsynaptic densities (Drake et al. 1997). At this location, GIRK channel activation might bear direct significance on the gating behaviour of NMDA channels by favouring their voltage-sensitive Mg2+ block. As the synaptic signal travels along the dendritic tree, activation of the GIRK current will not only shunt part of the synaptic current; the associated membrane hyperpolarization will also influence the availability of a number of voltage-dependent ion channels such as T-type Ca2+ channels, A-type K+ channels, and H-channels, which all play a significant role in the dendritic processing of subthreshold signals (see Introduction).

Is it conceivable that baclofen exerts an additional inhibitory effect on GPSPs through the concomitant reduction of somatic and, in particular, dendritic Ca2+ channels (Hille, 1994; Kavalali et al. 1997)? Inhibition of dendritic Ca2+ currents by GABAB receptor activation has been implicated in the reduction of the dendritic Ca2+ influx associated with back-propagating action potentials (Chen & Lambert, 1997), but modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein-coupled receptors should only play a minor role in the subthreshold voltage range. The baclofen-sensitive Ca2+ channels (most prominently N and P/Q type) contribute to the high voltage-activated Ca2+ current, whereas amplification of subthreshold EPSPs has been attributed mainly to low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels.

In addition to the phasic, GIRK channel-mediated inhibition of EPSPs that occurs during agonist application, we have obtained evidence for a tonic down-modulation of excitatory synaptic input, which appears to arise from a significant background activity of both IRK and GIRK channels. The ionic mechanism and the pharmacology of this standing inhibition are summarized in the schematic presented in Fig. 5. Whereas Ba2+ does not discriminate between GIRK and IRK channels, the selective GIRK channel blocker tertiapin allowed us to isolate a component of the standing inwardly rectifying K+ current that is mediated by background GIRK channel activity. Our experimental evidence that ambient adenosine maintains a tonic GIRK current activation in the slice preparation is the following: (1) the augmentation of GPSPs by tertiapin was abrogated in the presence of the adenosine degrading enzyme ADA, (2) more specifically, the selective A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX fully reproduced the action of ADA, (3) the reduction of inwardly rectifying K+ conductance by tertiapin disappeared when examined in the presence of DPCPX, and (4) in acutely isolated cell somata not exposed to ambient adenosine, the effect of tertiapin, but not of Ba2+, on K+ channel-mediated inward rectification was completely abrogated. From the latter we conclude that in native CNS neurones, GIRK channels display minimal activity in the absence of agonists. This extends and supports previous findings from cardiac GIRK channels in native preparations and heterologous expression systems, where the intrinsic open probability of GIRK channels is < 0.01 (Ivanova-Nikolova & Breitwieser, 1997; Nemec et al. 1999; Yakubovich et al. 2000).

Figure 5. Ionic mechanism and pharmacology of standing inwardly rectifying K+ conductance in pyramidal cells of the hippocampus.

See Discussion for explanation.

Using pharmacological approaches, estimates for the mean endogenous extracellular adenosine concentration in the hippocampal slice are between 140 and 200 nm (Dunwiddie & Diao, 1994). Dispelling concerns that the slice preparation gives rise to artificially high extracellular adenosine levels, ambient adenosine levels estimated in vivo are within the same range. When determined in the brain of awake rats by means of microdialysis, the resting adenosine concentration in the extracellular space was 40 nm, with physiological elavations up to 460 nm (Ballarin et al. 1991). Given the high affinity of adenosine for the rat brain A1 receptor (Kd 10–70 nm, Dunwiddie & Masino, 2001; Huber et al. 2001), the ambient adenosine concentration should be sufficient to produce a sustained activation of A1 receptors and GIRK channels in neurones of the intact brain.

Despite its tonic activation, A1 receptors do not display appreciable desensitization, but remain responsive to rises in extracellular adenosine. For example, exogenous adenosine (50–100 μm) is still capable of inducing substantial inwardly rectifying K+ currents in pyramidal neurones of the hippocampal slice (Alzheimer & ten Bruggencate, 1991). Thus it seems likely that the coupling of A1 receptors to GIRK channels serves a double function. Under physiological conditions, it contributes to the RMP and modulates excitatory synaptic transmission. Under pathophysiological conditions, the dramatic rise in extracellular adenosine exerts a presumed neuroprotective effect through membrane hyperpolarization and a substantial shunt of the excitatory synaptic input.

Because removal of purinergic inhibition completely abrogated the effect of tertiapin on GPSPs and inward rectification, continuously released or produced extracellular adenosine appears to be the sole source for the tonic activation of GIRK channels. The GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 55845 (2 μm) failed to influence the shape of GPSPs (data not shown), suggesting that the level of extracellular GABA resulting from spontaneous release is insufficient to influence GIRK channels through tonic activation of GABAB receptors.

Since in rat brain, the other family of K+ channels that contributes to background K+ channel activity, namely the two-pore domain K+ channels, require much higher concentrations of Ba2+ for effective inhibition (Patel & Honore, 2001), it seems reasonable to attribute the effects of Ba2+ observed in this study to the inhibition of inwardly rectifying K+ channels. In addition to its participation in setting the RMP (Sutor & Hablitz, 1993), our data indicate that this constitutive current is prominently involved in the somatodendritic processing of EPSPs. Constitutive K+ channel-mediated inward rectification should hence be included in the list of voltage-dependent ion currents that shape EPSPs and bear significance on synaptic integration. Given the non-linear I–V relationship of the inwardly rectifying K+ conductance, its shunting effect will be the larger the more the neurone is hyperpolarized and the smaller the incoming EPSPs. Thus, the role of background activity of IRK and GIRK channels might be envisioned as a mechanism by which to reduce synaptic noise and small (presumably less relevant) synaptic signals. In contrast, large synaptic signals will be much less affected, and supralinear EPSP summation might even be facilitated (Wessel et al. 1999), owing to the instantaneous activation and deactivation kinetics of the inwardly rectifying K+ conductance in response to rapid voltage changes. In functional terms, the standing inwardly rectifying K+ conductance might operate as a filter that alters the signal-to-noise ratio of the excitatory synaptic input in favour of strong, repetitive signals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the DFG (SFB 391 A9, and a Heisenberg-Fellowship to C.A.). We thank Luise Kargl and Franz Rucker for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Alzheimer C, Sutor B, ten Bruggencate G. Disinhibition of hippocampal CA3 neurons induced by suppression of an adenosine A1 receptor-mediated inhibitory tonus: pre- and postsynaptic components. Neuroscience. 1993;57:565–575. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer C, ten Bruggencate G. Postsynaptic inhibition by adenosine in hippocampal CA3 neurons: Co2+- sensitive activation of an inwardly rectifying K+ conductance. Pflügers Archiv. 1991;419:288–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00371109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballarin M, Fredholm BB, Ambrosio S, Mahy N. Extracellular levels of adenosine and its metabolites in the striatum of awake rat: inhibition of uptake and metabolism. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1991;142:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lambert NA. Inhibition of dendritic calcium influx by activation of G-protein-coupled receptors in the hippocampus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:3484–3488. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascal N. Signalling via the G protein-activated K+ channels. Cellular Signalling. 1997;9:551–573. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M. Purinergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Progress in Neurobiology. 1988;31:85–108. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Bausch SB, Milner TA, Chavkin C. GIRK1 immunoreactivity is present predominantly in dendrites, dendritic spines, and somata in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1007–1012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV. Endogenously released adenosine regulates excitability in the in vitro hippocampus. Epilepsia. 1980;21:541–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1980.tb04305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Diao L. Extracellular adenosine concentrations in hippocampal brain slices and the tonic inhibitory modulation of evoked excitatory responses. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;268:537–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillessen T, Alzheimer C. Amplification of EPSPs by low Ni2+- and amiloride-sensitive Ca2+ channels in apical dendrites of rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:1639–1643. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL, Greene RW. Endogenous adenosine inhibits hippocampal CA1 neurones: further evidence from extracellular and intracellular recording. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1988;337:561–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00182732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris NC, Constanti A. Mechanism of block by ZD 7288 of the hyperpolarization-activated inward rectifying current in guinea pig substantia nigra neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:2366–2378. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.6.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Modulation of ion channel function by G protein-coupled receptors. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A, Padrun V, Déglon N, Aebischer P, Möhler H, Boison D. Grafts of adenosine-releasing cells suppress seizures in kindling epilepsy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:7611–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131102898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova-Nikolova TT, Breitwieser GE. Effector contributions to G beta gamma-mediated signaling as revealed by muscarinic potassium channel gating. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;109:245–253. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin WL, Lu Z. A novel high-affinity inhibitor for inward-rectifier K+ channels. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13291–13299. doi: 10.1021/bi981178p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Christie BR. Active properties of neuronal dendrites. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:165–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karschin A. G Protein regulation of inwardly rectifying K+ channels. News in Physiological Sciences. 1999;14:215–220. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.5.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalali ET, Zhuo M, Bito H, Tsien RW. Dendritic Ca2+ channels characterized by recordings from isolated hippocampal dendritic segments. Neuron. 1997;18:651–663. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura H, Yokoyama M, Akita H, Matsushita K, Kurachi Y, Yamada M. Tertiapin potently and selectively blocks muscarinic K+ channels in rabbit cardiac myocytes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000;293:196–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky R, Gillessen T, Alzheimer C. Dendritic Na+ channels amplify EPSPs in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:2181–2191. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse MJ, Klotz KN, Lindenborn-Fotinos J, Reddington M, Schwabe U, Olsson RA. 8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) - a selective high affinity antagonist radioligand for A1 adenosine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1987;336:204–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00165806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic hyperpolarization-activated currents modify the integrative properties of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:7613–7624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic Ih normalizes temporal summation in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;2:848. doi: 10.1038/12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Dendritic integration of excitatory synaptic input. Nature Reviews in Neuroscience. 2000;1:181–190. doi: 10.1038/35044552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. Characterization of single voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels in apical dendrites of rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:67–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemec J, Wickman K, Clapham DE. Gβγ binding increases the open time of IKACh: kinetic evidence for multiple Gβγ binding sites. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:246–252. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77193-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara DY, Beck SG. 5-HT1A receptor linked to inwardly-rectifying potassium current in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;71:2161–2167. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC. Adenosine promotes burst activity in guinea-pig geniculocortical neurones through two different ionic mechanisms. Journal of Physiology. 1992;447:729–753. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AJ, Honore E. Properties and modulation of mammalian 2P domain K+ channels. Trends in Neurosciences. 2001;24:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01810-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger T, Alzheimer C. Muscarinic activation of inwardly rectifying K+ conductance reduces EPSPs in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;535:383–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodickson DL, Bean BP. GABAB receptor-activated inwardly rectifying potassium current in dissociated hippocampal CA3 neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:6374–6385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06374.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodickson DL, Bean BP. Neurotransmitter activation of inwardly rectifying potassium current in dissociated hippocampal CA3 neurons: Interactions among multiple receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:8153–8162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08153.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Sakmann B. Amplification of EPSPs by axosomatic sodium channels in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Spruston N. Determinants of voltage attenuation in neocortical pyramidal neuron dendrites. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3501–3510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03501.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutor B, Hablitz JJ. Influence of barium on rectification in rat neocortical neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;157:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90643-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa T, Alzheimer C. G protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) currents in dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal cells. Journal of Physiology. 1999a;517:385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0385t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa T, Alzheimer C. Variance analysis of current fluctuations of adenosine- and baclofen-activated GIRK channels in dissociated neocortical pyramidal cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999b;82:1647–1650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.3.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban NN, Henze DA, Barrionuevo G. Amplification of perforant-path EPSPs in CA3 pyramidal cells by LVA calcium and sodium channels. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:1558–1561. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel R, Kristan WB, Jr, Kleinfeld D. Supralinear summation of synaptic inputs by an invertebrate neuron: dendritic gain is mediated by an “inward rectifier” K+ current. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:5875–5888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05875.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich D, Pastushenko V, Bitler A, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. Slow modal gating of single G protein-activated K+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:737–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Inanobe A, Kurachi Y. G protein regulation of potassium ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1998;50:723–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi BA, Lin YF, Jan YN, Jan LY. Yeast screen for constitutively active mutant G protein-activated potassium channels. Neuron. 2001;29:657–667. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]