Abstract

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel bears two nucleotide-binding domains (NBD1 and NBD2) that control its ATP-dependent gating. Exactly how these NBDs control gating is controversial. To address this issue, we examined channels with a Walker-A lysine mutation in NBD1 (K464A) using the patch clamp technique. K464A mutants have an ATP dependence (EC50 ≈ 60 μm) and opening rate at 2.75 mm ATP (∼ 2.1 s−1) similar to wild type (EC50 ≈ 97 μm; ∼ 2.0 s−1). However, K464A's closing rate at 2.75 mm ATP (∼ 3.6 s−1) is faster than that of wild type (∼ 2.1 s−1), suggesting involvement of NBD1 in nucleotide-dependent closing. Delay of closing in wild type by adenylyl imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP), a non-hydrolysable ATP analogue, is markedly diminished in K464A mutants due to reduction in AMP-PNP's apparent on-rate and acceleration of its apparent off-rate (∼ 2- and ∼ 10-fold, respectively). Since the delay of closing by AMP-PNP is thought to occur via NBD2, K464A's effect on the NBD2 mutant K1250A was examined. In sharp contrast to K464A, K1250A single mutants exhibit reduced opening (∼ 0.055 s−1) and closing (∼ 0.006 s−1) rates at millimolar [ATP], suggesting a role for K1250 in both opening and closing. At millimolar [ATP], K464A-K1250A double mutants close ∼ 5-fold faster (∼ 0.029 s−1) than K1250A but open with a similar rate (∼ 0.059 s−1), indicating an effect of K464A on NBD2 function. In summary, our results reveal that both of CFTR's functionally asymmetric NBDs participate in nucleotide-dependent closing, which provides important constraints for NBD-mediated gating models.

Defective in cystic fibrosis patients, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel possesses two pore-forming membrane-spanning regions, a regulatory (R) domain and two nucleotide-binding folds (Riordan et al. 1989). These structural components make CFTR a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily and subserve its function as a regulated ion channel (Gadsby & Nairn, 1999; Sheppard & Welsh, 1999). For channel activation, phosphorylation of the R domain is a necessary, but not sufficient, prerequisite (Anderson et al. 1991; Nagel et al. 1992). Once phosphorylated, CFTR also requires the presence of ATP or other γ-phosphate hydrolysable nucleotide analogues for gating (Anderson et al. 1991; Nagel et al. 1992), presumably acting at the nucleotide-binding folds.

CFTR's two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) share features common to a number of ABC superfamily members (Holland & Blight, 1999), including the Walker-A and -B motifs, highly conserved sequences essential for the catalytic activity of many ATPases (Saraste et al. 1990). Despite these common features, CFTR's two NBDs show only ∼ 33 % overall similarity to each other, perhaps indicating potential differences in their functions (Manavalan et al. 1995; Nagel, 1999; Zou & Hwang, 2001). Indeed, each NBD has been hypothesized to play distinct, separable roles in CFTR gating (Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Zeltwanger et al. 1999; cf. Ikuma & Welsh, 2000). Consistent with models involving functionally separate NBDs, several electrophysiological studies have demonstrated two distinct ATP-binding sites involved in CFTR gating. The first site is revealed by the fact that γ-phosphate hydrolysable nucleotides, such as ATP, are required for CFTR activity (Anderson et al. 1991; Nagel et al. 1992). Non-hydrolysable ATP analogues, such as adenylyl imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP), cannot open CFTR (Anderson et al. 1991; Nagel et al. 1992; cf. Aleksandrov et al. 2000); in fact, AMP-PNP has been shown to reduce the opening rate in the presence of ATP (Mathews et al. 1998b; Weinreich et al. 1999). In addition to slowing opening, AMP-PNP reduces the closing rate of channels already opened by ATP, indicating a functional second site for nucleotides after the channel is opened by ATP at the first (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Mathews et al. 1998b; Weinreich et al. 1999). The idea that this second functional site corresponds to NBD2 became prominent because millimolar [ATP] can prolong the opening of a Walker-A lysine mutant at NBD2 (i.e. K1250A), mimicking AMP-PNP's effect on wild type CFTR (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Zeltwanger et al. 1999).

Since NBD2 probably forms the second site, NBD1 was designated as the site involved in channel opening. Supporting this idea, some investigators reported that a mutation in NBD1′s Walker-A motif (i.e. K464A) reduces CFTR's opening rate (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Vergani et al. 2000). However, those earlier reports are being challenged by more recent demonstrations that K464A has little effect on channel opening (Sugita et al. 1998; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999; present study). Similarly, channel opening is little affected by other mutations in NBD1 expected to disrupt interaction with nucleotides (Berger & Welsh, 2000; Vergani et al. 2000). Nevertheless, some studies do seem to indicate an importance for NBD1 in channel opening (Carson & Welsh, 1995; Cotten & Welsh, 1998; Vergani et al. 2000). These conflicting findings create considerable controversy regarding the idea that channel opening involves NBD1.

To examine the contribution of NBD1 during CFTR gating, we assessed the kinetic properties of the Walker-A mutant K464A.

METHODS

Construction of CFTR mutants

Wild type and mutant CFTR-containing plasmids used for transfection were constructed in two stages: the CFTR coding region was first shuttled into pBQ4.7 and then subcloned into pLJ for stable transfections or into pcDNA3.1Zeo(+) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for transient transfections. The plasmids K464A-pRBG4 and K1250A-pRBG4 were gifts from Dr R. R. Kopito (Stanford University, CA, USA), and the plasmid CFTRwt-pBQ4.7 and the retroviral vector pLJ were gifts from Dr M. Drumm (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA). To construct K464A-pBQ and K1250A-pBQ, the 0.7 kb BspEI-BstZ171 fragment from K464A-pRBG4 and the 3.0 kb BspEI-NcoI fragment from K1250A-pRBG4, respectively, replaced the corresponding ones in CFTRwt-pBQ4.7. To create WT-pLJ and K1250A-pLJ, the 4.7 kb EcoICRI fragments from CFTRwt-pBQ4.7 and K1250A-pBQ, respectively, were ligated to Bcl I linkers, cut with BclI, then ligated into the BamHI site of the pLJ vector. For construction of K464A-pLJ, the 3.6 kb BspEI-SalI fragment from K464A-pBQ was exchanged with the corresponding one in WT-pLJ. To generate WT-pCDNA, K464A-pCDNA and K1250A-pCDNA, the 4.7 kb PstI fragments from the corresponding pBQ constructs were subcloned into the PstI site of pCDNA. For the creation of K464A-K1250A-pCDNA, the 2.7 kb BspEI-PflMI fragment from K464A-pCDNA was used to substitute the corresponding region in K1250A-pCDNA. Plasmids used for transfection were sequenced to ensure the presence of the mutations (DNA Core, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA).

Culture and preparation of NIH3T3 and Chinese hamster ovary cells for patch clamp

Wild type and mutant CFTR were stably expressed in NIH3T3 cell lines or transiently expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines (both lines from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) grown at 37 °C and 95 % O2-5 % CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Harlan Biosciences, Madison, WI, USA). Cells were plated on sterile glass chips for 1–2 days before patch clamp recording. To obtain recordings with few channels per patch, we used NIH3T3 cells stably transfected with wild type CFTR (Berger et al. 1991), CFTR-K1250A and CFTR-K464A (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study). To obtain recordings with quasi-macroscopic currents, we used naive CHO cells transiently transfected with the pCDNA constructs using SuperFect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). For transient transfections, the pCDNA constructs were cotransfected with GFP (pEGFP-C3, Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) to allow ready detection of cells expressing CFTR using UV illumination. CFTR channels in both expression systems exhibited similar kinetics (data not shown), suggesting that cell type-specific differences and GFP expression have little influence on gating (see also Winter et al. 1994).

Electrophysiological recording of heterologously expressed CFTR in excised inside-out patches

Using fire-polished pipettes with resistances of 3–6 MΩ in our standard bath solution, we recorded from cells plated onto glass chips that were then transferred into continuously perfused chambers. In our excised inside-out patch recordings, the superfusion solution contained (mm): 150 N-methyl-d-glucamine chloride (NMDG-Cl), 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 8 Tris and 2 MgCl2 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with 1 mN-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG)). Pipette solution contained (mm): 140 NMDG-Cl, 2 MgCl2, 5 CaCl2 and 10 Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.4 with 1 m NMDG). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), except Li4AMP-PNP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA; Promega, Madison, WI, USA). MgATP, Li4AMP-PNP and PKA were diluted in superfusion solution to their final concentrations just before use. Recordings were performed at room temperature (∼ 25 °C) with an EPC9 patch clamp amplifier (Heka Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany), filtered at 100 Hz with a built-in 3-pole Bessel filter, and stored on videotapes using a pulse code modulator-VCR combination (Vetter, Rebersburg, PA, USA and JVC, Elmwood Park, NJ, USA).

Storage and playback of electrophysiological data

CFTR exhibits a slow ATP-dependent gating (∼ 100–1000 ms) and a flickery, ATP-independent gating (∼ 1–10 ms; for example, see Zhou et al. 2001). To eliminate most of these flickers from our analysis of ATP-dependent gating, we filtered our recordings at 25 Hz (resulting in a 10–90 % rise time of 12 ms). Accordingly, the data from most experiments were played back from videotapes, filtered at 25 Hz using an 8-Pole Bessel filter (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) and captured onto a hard disk (Macintosh Quadra 450; Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) at a sampling rate of 125 Hz for kinetic analysis. In a minority of experiments, the played back data were originally filtered at 50 Hz and digitized at 200 Hz using an 8-pole Bessel filter; these recordings were digitally refiltered at 25 Hz (using a Gaussian filtering algorithm written by Dr László Csánady, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary) for consistency during kinetic analysis. Using both filtering protocols gave similar results (data not shown).

Macroscopic dose-response analysis of K464A channels

To quantify the ATP dependence of K464A channels, we normalized baseline-subtracted mean current levels elicited by test [ATP] against mean current levels at 2.75 mm ATP as previously described (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; see Fig. 1). The activity levels during the first application of 2.75 mm ATP were used for comparison with test values. Normalized responses were plotted against [ATP] and fitted with the Michaelis-Menten equation, holding the maximum response at 1. Analyses of the data were performed using Igor Pro (version 4.01; Wavemetrics, Oswego, OR, USA).

Figure 1. ATP dose-response relationships for CFTR-K464A.

A, representative trace of macroscopic CFTR-K464A channel current stimulated by 2.75 mm and 25 μm ATP after steady-state activation by PKA phosphorylation (not shown). B, trace of CFTR-K464A channels exposed to different [ATP] after steady-state activation by PKA and ATP. C, macroscopic dose-response relationship for CFTR-K464A (▪; present study) and wild type CFTR (□; data taken from Zeltwanger et al. 1999). D, open probability versus [ATP] for CFTR-K464A (•; present study) and wild type (○; data taken from Zeltwanger et al. 1999). The maximum Po for CFTR-K464A at 2.75 mm ATP is ∼ 0.37. E, superimposition of macroscopic (□) and microscopic (•) data shown in C and D. Arrows in A and B indicate the baseline current level (all channels closed) and downward deflections are channel openings. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of experiments per data point. Dashed lines are fits of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the CFTR-K464A data (see Methods).

Microscopic dose-response analysis of K464A channels

Recordings from patches with four channels or less were used for detailed kinetic analyses performed with Igor Pro and a suite of programs written by Dr László Csánady (Csánady, 2000). Current traces were baseline corrected, idealized and fitted to a simplified closed-open scheme (C ⇌ O) using a 50 ms dead time to suppress any remaining flickers (see above). An analysis of flickery events in K464A channels using 100 Hz filtering and 500 Hz sampling justified the 50 ms cut-off (data not shown). Channel open probability was also calculated by the fitting program from the events list as the time averaged current divided by the number of channels and the single channel amplitude (Chan et al. 2000). The number of channels per patch was estimated as being the maximum number of channels visible during exposure to 2.75 mm ATP. Based on an estimator derived by Venglarik et al. (1994; see references therein) that assumes all channels are identical and independent, the duration of exposure to 2.75 mm ATP in all experiments (> 100 s) was far longer than the duration required to ensure a P > 0.95 for our estimate of the number of channels (∼ 18 s for 5 channels), given that Po ≈ 0.4, τo ≈ 0.3 s and τc ≈ 0.4 s in the presence of 2.75 mm ATP (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). Kinetic data obtained from wild type channels at 2.75 mm ATP in this study (see Results) were very similar to results obtained previously in this laboratory (Zeltwanger et al. 1999), permitting a direct comparison of wild type dose-response data from our prior study to mutant data from this study.

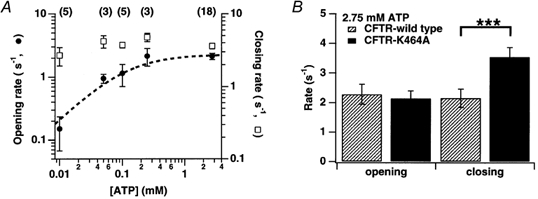

Figure 3. Dependence of CFTR-K464A closing and opening rates on [ATP].

A, plot of mean opening rates (reciprocals of mean closed times; •) and closing rates (reciprocals of mean opened times; □) versus[ATP] for CFTR-K464A. Dashed line is a fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the opening rate data (see Methods). B, comparison of opening and closing rates for CFTR-K464A and wild type at 2.75 mm ATP. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between closing rates for wild type and K464A (P < 0.005).

Estimation of AMP-PNP-prolonged open time

To estimate channel open time for wild type CFTR in the presence of AMP-PNP, we derived time constants from macroscopic relaxations upon removal of all nucleotides (see Zeltwanger et al. 1999). Current relaxations were fitted with single exponential functions using a Levenberg-Marquardt based algorithm within the Igor Pro program to produce time constants used to estimate mean open time. The algorithm reports the relaxation time constant plus or minus the standard deviation for each fit. However, since the solution exchange in our system is relatively slow (∼ 5 s; cf. Zeltwanger et al. 1999), relaxation times for K464A, but not wild type, are probably rate limited more by nucleotide removal rather than actual channel closing (see Results).

To estimate more accurately the AMP-PNP-dependent open time for K464A channels, we analysed recordings with only one or two channels; open events where two channels were open simultaneously were averaged and included as described previously (Fenwick et al. 1982; Wang et al. 1998). Dwell times were ranked in order of decreasing duration, normalized by the number of events and displayed as survivor plots (i.e. the probability of still being open at time t given that the channel was open at time zero versus time). Survivor plots were fitted with a double exponential function using Igor Pro to estimate mean durations in the open and ‘locked open’ (AMP-PNP-dependent) states.

Estimation of apparent locking rate for AMP-PNP

To discriminate between open (O) and AMP-PNP-dependent locked open (L) events, we used the method of Jackson et al. (1983) to determine an appropriate cut-off for classifying events as either O or L (see Scheme 1 in Results). Based on our open time analysis of K464A channels in the presence of 250 μm ATP and 1 mm AMP-PNP (see above), we used a cut-off of 842 ms for both wild type and K464A channels. Use of this cut-off for both types of channels is justifiable, since both K464A and wild type have similar open times (i.e. dwell times in O) at 250 μm ATP alone. The apparent locking rate (rLO; see Scheme 1 in Results) was measured as the cumulative time the channel spent in O before entering L. The cumulative times were displayed as survivor plots and fitted with single exponentials to determine the mean locking rate.

Scheme 1.

Estimation of kinetic parameters for K1250A and K464A-K1250A

For recordings of quasi-macroscopic K1250A and K464A-K1250A channel currents, open probability was estimated by means of variance analysis (Sigworth, 1980): Po = (1 − (σ2/Ii)), where Po represents open probability, σ2 the variance of steady-state current, I the mean steady-state current and i the single channel amplitude. The closed times for these mutants were calculated from the equation: Po = τo/(τo + τc), where τo represents the channel open time estimated from exponential fits to current relaxations using Igor Pro (see above).

Statistical analysis

All averages are reported as the means ± s.e.m., unless otherwise indicated. To determine the statistical significance of differences between the observed means, one-tailed paired and unpaired Student's t tests were used, as appropriate. Differences where P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

As a step towards understanding how CFTR's NBDs participate in gating, we examined the kinetic behaviour of the NBD1 mutant K464A, the NBD2 mutant K1250A and double mutant K464A-K1250A. K464A mutants were examined first. To determine whether K464A affected CFTR's ATP dependence, we performed a dose-response analysis. Some earlier reports indicated that K464A reduced ATP affinity (Anderson & Welsh, 1992; Vergani et al. 2000). This apparent reduction, however, may arise from presteady-state phosphorylation, since previous studies have shown that submaximal phosphorylation can alter ATP affinity and channel kinetics (e.g. Mathews et al. 1998a; Weinreich et al. 1999). To ensure that changes in activity arose from alterations in [ATP], not phosphorylation, test exposures were bracketed with exposures to 2.75 mm ATP as controls, and patches showing > 30 % difference between first and second control exposures were excluded from analysis. Figure 1A shows a typical experiment; after activation by 40 U ml−1 PKA and 2.75 mm ATP (not shown), the patch was exposed to 2.75 mm ATP alone, next to 25 μm ATP, then to 2.75 mm ATP again. The current responses were plotted against [ATP] and fitted with the Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. 1C). Fitting with the Michaelis-Menten equation is meant only to estimate the sensitivity of channel activity to ATP and not to imply any particular kinetic mechanism for CFTR gating. From the fit, the Km for K464A channels was 59 ± 9 μm. For comparison, the Km for wild type channels was 97 ± 16 μm, using the same fit procedure with our previous data (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; Fig. 1C). This comparison indicates that the K464A mutation had little effect on ATP sensitivity.

To estimate the ATP dependence of open probability in K464A mutants, the Po was measured in patches with one to four channels. Figure 1B shows a typical experiment. Channels in the patch were activated to the steady state by PKA (40 U ml−1) and 2.75 mm ATP (not shown) and exposed to 2.75 mm ATP, then to 10 and 100 μm ATP, and then again to 2.75 mm ATP. Figure 1D shows pooled dose-Po data from 18 experiments that were fitted with the Michaelis-Menten equation without any constraints. The fit produced a Km of 63 ± 1 μm with a maximum Po of 0.37 at 2.75 mm ATP. The fit results closely matched the measured data; the measured mean Po for K464A channels was 0.37 ± 0.02 (n = 18) at 2.75 mm ATP, 0.21 ± 0.05 (n = 5) at 100 μm ATP, and 0.19 ± 0.02 (n = 3) at 50 μm ATP, indicating that the EC50 for ATP lies between 50 and 100 μm. The macroscopic and microscopic data also closely matched, as shown in the overlay of both data sets (Fig. 1E). This similarity shows that changes in Po underlie the channel's ATP dependence. Furthermore, a comparison of K464A to wild type (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study, Fig. 1B) shows little change in ATP sensitivity of Po. A Michaelis-Menten fit to our previous wild type data gave a Km of 137 μm with a maximum Po of 0.41, slightly higher than K464A.

We next tested how [ATP] affected channel opening and closing rates in K464A mutants. Earlier reports examining K464A's opening and closing rates gave conflicting results (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; but cf. Sugita et al. 1998; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999). Figure 2A shows sweeps from a recording of a single CFTR-K464A channel exposed to 2.75 mm and 100 μm ATP. Sweeps from a recording of a single CFTR-wild type channel are included for comparison (Zeltwanger et al. 1999). In 100 μm ATP the K464A channel exhibits longer closures, while the duration of openings at both concentrations appears similar. Figure 2B shows the closed and open time distributions from the K464A recordings in Fig. 2A. These distributions were fitted with single exponential functions to estimate mean dwell times. With a 27.5-fold decrease in [ATP], the mean closed time increases ∼ 57 % while open time increases by ∼ 17 % for this particular experiment (Fig. 2B), suggesting that changes in [ATP] mostly affect closed time.

Figure 2. Single-channel kinetics of CFTR-K464A.

A, representative sweeps from experiments with single CFTR-wild type (left-hand sweeps; taken from Zeltwanger et al. 1999) and CFTR-K464A channels (right-hand sweeps) exposed to 2.75 mm (top sweeps) and 100 μm MgATP (bottom sweeps) subsequent to activation by PKA (40 U ml−1) and ATP (2.75 mm). Arrows indicate the baseline and downward deflections indicate openings of the channel. B, survivor plots of closed (left-hand panels) and open dwell times (right-hand panels) at 2.75 mm (top panels) and 100 μm MgATP (bottom panels) for the single CFTR-K464A channel shown in A (cf. wild type distributions in Zeltwanger et al. 1999). Dashed lines indicate single exponential fits to the data; time constants (τ) for the fits are indicated.

These mean dwell times reflect in kinetic terms the transition rates between the channel's closed and open states. To relate dwell times to transition rates, one calculates opening and closing rates as the reciprocals of the mean closed and open times, respectively. The relationship between rates and [ATP] for K464A mutants is shown in Fig. 3A; the data shown represent the mean rates pooled from 18 experiments. The opening, but not closing, rate shows a marked dependence on [ATP]. As expected, a paired comparison of rates at 2.75 mm and 100 μm ATP (near the EC50) uncovers a significant difference for opening (2.3 versus 1.1 s−1, respectively; n = 5, P < 0.005) but not for closing (3.8 versus 3.7 s−1, respectively; n = 5, P ≈ 0.43).

To quantify the ATP sensitivity of opening in K464A mutants, the data were fitted to a Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. 3A). The fit produced a Km of 73 ± 33 μm with a maximum opening rate of 2.2 ± 0.3 s−1. Consistent with the fit results, the measured opening rates were 2.1 ± 0.3 s−1 (n = 18) at 2.75 mm ATP, 1.1 ± 0.4 s−1 (n = 5) at 100 μm ATP and 1.0 ± 0.2 s−1 (n = 3) at 50 μm ATP, indicating an EC50 between 50 and 100 μm. Our findings confirm that ATP-dependent opening is not impaired by the K464A mutation, qualitatively consistent with the data of Sugita et al. (1998) and Ramjeesingh et al. (1999).

Unlike opening, K464A channel closing exhibits little, if any, dependence on ATP. On the one hand, paired comparisons of closing rates at various [ATP] showed no significant differences (see above; Fig. 3A). On the other hand, a comparison of closing rates for K464A and wild type at 2.75 mm ATP does reveal a difference (3.6 ± 0.3 s−1, n = 18 versus 2.1 ± 0.3 s−1, n = 6, respectively; P < 0.005; Fig. 3B). Thus, K464A appears to abolish the ATP dependence of the closing rate seen in wild type. From this result, we suspected that K464A might affect the second functional site for ATP, which is presumed responsible for prolonging open time in wild type channels at millimolar [ATP] (Zeltwanger et al. 1999).

Since this second functional site for ATP is thought to be the site for AMP-PNP action (Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Mathews et al. 1998b; Zeltwanger et al. 1999), we examined whether K464A affected AMP-PNP's prolongation of channel opening. AMP-PNP greatly prolongs open time in wild type CFTR channels already opened by ATP (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Mathews et al. 1998b). An example of this is shown in Fig. 4A. A single wild type channel activated by PKA (40 U ml−1) and ATP (250 μm) opens and shuts rapidly (Fig. 4A, upper trace). Upon addition of AMP-PNP (1 mm), the channel rapidly opens and shuts a few times more and then enters into a long opening, termed a ‘locked open’ event. This locked open event is consistent with the prolonged openings seen in previous studies. Prolonged openings can also be seen in K464A channels exposed to AMP-PNP, but with lower frequency and shorter duration. For example, Fig. 4A (lower trace) shows a single K464A channel activated by PKA (40 U ml−1) and ATP (250 μm), then exposed to AMP-PNP (1 mm). Unlike the wild type example, the K464A channel took much longer to become locked open. Moreover, the time spent being locked open was shorter. These two examples suggest that the K464A mutation reduces the ability to become locked open and to stay locked open by AMP-PNP, further substantiating the idea that K464A affects the second functional site for ATP.

Figure 4. AMP-PNP weakly locks open CFTR-K464A.

A, representative sweeps from experiments with wild type (top trace) and CFTR-K464A single channels (bottom trace) exposed first to PKA (40 U ml−1) and MgATP (250 μm), then with the addition of AMP-PNP (1 mm). Arrows indicate the baseline, downward deflections channel openings. B, survivor plot of open dwell times for CFTR-K464A. Dashed line is a double-exponential fit to the data. Time constants and their relative weights from the fit are indicated.

In addition to its action at the second functional site for ATP, AMP-PNP also acts at the first site by slowing ATP-dependent opening in wild type CFTR channels (Mathews et al. 1998b; Weinreich et al. 1999). The opening of K464A channels is slowed by AMP-PNP as well. The mean closed time for K464A channels exposed to 250 μm ATP and 1 mm AMP-PNP was 1366 ± 260 ms (n = 6), approximately threefold longer than in 250 μm ATP alone (∼ 465 ms; Fig. 3A). This increase in closed time suggests interaction of AMP-PNP at both functional sites for ATP, one for opening and the other for closing.

To quantify the extent to which K464A affects the second functional site, we first estimated the duration of AMP-PNP-dependent locked open events using current relaxation time courses upon removal of AMP-PNP. This method has been used previously to determine locked open duration (Zeltwanger et al. 1999). Figure 5A shows a comparison of relaxations from wild type (top trace) and K464A channels (bottom trace). The channels are activated by PKA, ATP and AMP-PNP to the steady state, then superfused with kinase- and nucleotide-free bath solution. Wild type channels close slowly, while K464A channels rapidly shut, indicating a shortened locked open duration in the mutant. On average, wild type channels show a mean relaxation time constant of 105 ± 22 s (n = 5) and K464A channels 12 ± 3 s (n = 5; P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). However, given that the solution exchange in our system is relatively slow (∼ 5 s; cf. Zeltwanger et al. 1999), relaxation times for K464A are probably rate limited more by nucleotide removal than actual channel closing. Nevertheless, for wild type channels the macroscopic decay accurately reflects the off rate of AMP-PNP, since wild type relaxations are more than 10-fold longer than the exchange dead time.

Figure 5. K464A enhances the dissociation of AMP-PNP.

A, representative traces from experiments with macroscopic currents from CFTR-wild type (top trace) and CFTR-K464A channels (bottom trace) exposed to PKA (40 U ml−1), MgATP (250 μm) and AMP-PNP (1 mm). Current relaxations upon withdrawal of PKA, ATP and AMP-PNP were fitted with single exponential curves to estimate mean open time (see Methods). For the traces shown, the mean relaxation time constant for wild type is 64.8 ± 0.1 s and for CFTR-K464A is 9.1 ± 0.1 s. B, mean relaxation time constants (± s.e.m.) for wild type and K464A channels. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between wild type and K464A (P < 0.01).

To obtain a more accurate estimate for locked open event duration in K464A channels, we analysed the open time distribution from patches with one or two channels in the presence of PKA, ATP and AMP-PNP (Fig. 4B; see Methods). In the open time distribution, two components were observed. One component was ∼ 300 ms, consistent with the mean open time for K464A channels in 250 μm ATP alone (Fig. 4B; cf. Fig. 3). The other component was approximately fourfold longer (∼ 1300 ms). These two components indicate the presence of two distinct open states: a relatively short one characteristic of ATP alone and a longer one due to the addition of AMP-PNP. While relaxation analysis overestimates the locked open time, this method underestimates it. In patches with more than one channel, averaging dwell times where one channel opens briefly while the other locks open will reduce the apparent locked open duration. Thus, the true AMP-PNP-dependent open time lies somewhere between the macroscopic and microscopic measures. Nevertheless, both results strongly demonstrate that the mutation impairs the ability to stay locked open in the presence of AMP-PNP by at least 10-fold.

In addition to reducing the time spent locked open, the K464A mutation also impairs the ability to become locked open, as exemplified by Fig. 4A. In that example, the K464A channel opens and shuts many times before being locked open, while wild type opens and shuts only a few times before locking open. To quantify the ability to become locked open, we used an approach similar to that used by Baukrowitz et al. (1994), who examined the ability of vanadate to lock open CFTR channels opened by ATP. Taking into account that ATP-dependent opening occurs before the channel becomes locked open by AMP-PNP (Hwang et al. 1994), the following simplified model was used:

where C is the closed state, O the open state and L the locked open state; rCO and rOC are the pseudo-first order rate constants for ATP-dependent opening and ATP-independent closing, respectively; rLO is the rate for leaving the locked open state, while rOL is the AMP-PNP-dependent rate for entering the locked open state.

To apply this model to our results, we needed to discriminate between O and L open events. To accomplish this task, we used the method of Jackson et al. (1983), which determines a cut-off time at which there is an equivalent probability of misassigning an event to either of the two states. Using the open duration data from K464A channels exposed to AMP-PNP (Fig. 4B), we calculated a cut-off of 842 ms; openings longer than 842 ms were L state and shorter ones O. This cut-off was used to classify open events for both wild type and K464A channels.

Once open events were classified as being O or L, rOL (i.e. the locking rate) was measured as the cumulative time spent in O before entering L. These cumulative times were then plotted as probability of being in O, not L, versus time to examine their distribution. Figure 6A shows the distributions obtained from two experiments, one with wild type channels and the other with K464A. In the experiments shown, the locking rate for wild type (□) was 1110 ± 70 s−1m−1 (21 events) and for K464A (○) 370 ± 10 s−1m−1 (49 events), qualitatively consistent with the examples in Fig. 4A. On average, wild type channels exhibited a faster locking rate (890 ± 140 s−1m−1, n = 3) than K464A (560 ± 110 s−1m−1, n = 6; P < 0.05; Fig. 6B), indicating that the mutation impairs AMP-PNP's ability to lock open CFTR.

Figure 6. K464A reduces the apparent on-rate of AMP-PNP.

A, Semilog plot of a probability function determined by measuring the cumulative time channels spent in the O state before entering the L state (see Methods). The dwell times are from individual experiments for CFTR-K464A (○) and CFTR-wild type (□). Dashed lines are single exponential fits for estimating the pseudo-first order locking rate (i.e. the O-L transition in Scheme 1). B, comparison of the mean locking rates for CFTR-wild type and CFTR-K464A. Asterisk indicates a significant difference between wild type and K464A (P < 0.05).

This ability to lock open CFTR is thought to be mediated by NBD2, since mutations there can greatly prolong open time (for review see Nagel, 1999; Zou & Hwang, 2001). Thus, channels bearing K1250A, the lysine-to-alanine mutation in the Walker-A motif of NBD2, exhibit a prolonged open state, similar to the AMP-PNP-dependent locked open state (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999; Zeltwanger et al. 1999). We wondered whether K464A reduces channel open time in K1250A mutants as it does with AMP-PNP. To test this idea, we determined the mean open time for both K1250A single mutant and K464A-K1250A double mutant channels using relaxation time courses upon ATP withdrawal (Fig. 7A). In the examples shown, the double mutant relaxes more rapidly than the single mutant. On average, K464A-K1250A channel currents decay fivefold more quickly than K1250A (34 ± 7 s, n = 5 versus 167 ± 37 s, n = 6, respectively; Fig. 7C; cf. Zeltwanger et al. 1999). K464A's reduction of K1250A's open time qualitatively mirrors the results with AMP-PNP.

Figure 7. K464A shortens K1250A relaxation.

A, representative trace of macroscopic current relaxations from CFTR-K1250A (top trace) and CFTR-K464A-K1250A double mutant channels upon withdrawal of PKA (40 U ml−1) and ATP (1 mm). Mean relaxation time constant for the CFTR-K1250A trace shown is 110 ± 1 s and for CFTR-K464A-K1250A is 30 ± 1 s. B, few-channel traces of CFTR-K1250A and CFTR-K464A-K1250A at the steady state in 2.75 mm ATP. Dashed lines indicate baseline (all channels closed); marks at the left indicate open channel current levels (a total of 4 channels for K1250A and 3 for K464A-K1250A). C, comparison of steady-state Po, mean open (relaxation) times and mean closed times for CFTR-K1250A and CFTR-K464A-K1250A. Asterisks indicate significant differences between CFTR-K1250A and CFTR-K464A-K1250A (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005).

We also examined the open probability of K1250A and K464A-K1250A. Figure 7B shows examples of single and double mutants at the steady state in the presence of PKA (40 U ml−1) and ATP (2.75 mm). In this example, all four K1250A channels remain open for most of the sweep, whereas only two of the three double mutants channels are open most of the time, suggesting a lower Po for K464A-K1250A. As expected, K1250A channels exhibit a steady-state Po of 0.89 ± 0.02 (n = 6; Fig. 7C) and double mutants 0.67 ± 0.05 (n = 5; P < 0.005). Our estimates of Po for both mutants are much higher than previously reported (∼ 0.2–0.34 for K1250A and ∼ 0.25 for K464A-K1250A; Carson et al. 1995; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999; but cf. ∼ 0.9 for K1250A; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995). The differences probably arise from measurements of presteady-state phosphorylated K1250A channels which exhibit a lower Po than those at the steady state (A. C. Powe & T.-C. Hwang, unpublished observations).

To see whether the reduced Po of K464A-K1250A mutants arises only from shorter open times, we calculated mean closed times from steady-state Po and relaxation time constants (see Methods). The calculated mean closed time for K1250A at 2.75 mm ATP was 18 ± 4 s (n = 6; Fig. 7C). Thus, K1250A prolongs closed time > 30-fold compared either to wild type or to the K464A single mutant (Fig. 3B). This finding is qualitatively consistent with previous reports (Carson & Welsh, 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999). The mean closed time for K464A-K1250A (17 ± 4 s, n = 5; Fig. 7B) is similar to that for K1250A (P ≈ 0.42). Our results show that the lower Po in the double mutant is mostly due to shortening of K1250A's long open time by K464A.

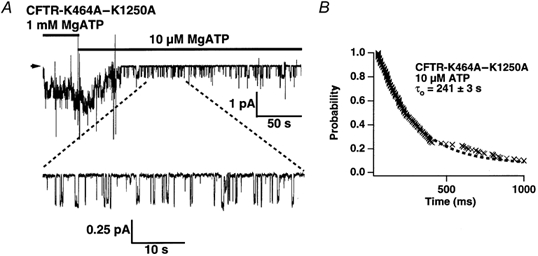

Although K1250A exhibits long open times at millimolar [ATP], the mutant channel opens only briefly at micromolar [ATP] (Zeltwanger et al. 1999). We tested whether K464A-K1250A behaved in a similar manner. A typical example of K464A-K1250A's gating behaviour is shown in Fig. 8A. In 1 mm ATP, double mutant channels remain open for long periods, resulting in the majority of channels being open simultaneously. In 10 μm ATP, the channels open only briefly, with far fewer instances of more than one channel open simultaneously. The expanded trace in Fig. 8A shows that most channel openings at 10 μm ATP last less than a second. This result is qualitatively similar to that shown for K1250A (Zeltwanger et al. 1999). We then examined the open time distribution of K464A-K1250A channels in the presence of 10 μm ATP shown in Fig. 8B (n = 3; 220 events total). A single exponential fit to the distribution provides an estimated open time of 241 ± 3 ms, similar to the open time of wild type, K464A and K1250A at 10 μm ATP (∼ 250 ms; Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study, Fig. 3A). Thus, K464A had little effect on brief openings seen in K1250A at micromolar [ATP].

Figure 8. K464A-K1250A gating at millimolar and micromolar [ATP].

A, representative sweep from experiments with CFTR-K464A-K1250A channels exposed first to 1 mm and then to 10 μm MgATP. Arrow indicates the baseline, downward deflections channel openings. B, survivor plot of open dwell times for CFTR-K464A-K1250A at 10 μm MgATP. Dashed line is a single-exponential fit to the data. Time constant for the fit is 241 ± 3 s (220 events pooled from 3 patches).

DISCUSSION

Functional asymmetry of CFTR's two NBDs

Understanding how CFTR's NBDs control gating is critical for ascertaining how this channel uses ATP to drive opening and closing. Critical for hydrolysis in many ATPases, the highly conserved Walker-A lysines provide good starting points to investigate NBD function in CFTR. Mutations in the Walker-A lysines for NBD1 (K464) and NBD2 (K1250) were used previously to probe the domains' function in gating but with conflicting results (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; cf. Sugita et al. 1998; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999). Several novel insights into the roles of the NBDs emerge from our examination of the Walker-A mutants.

Our results demonstrate a functional asymmetry between CFTR's Walker-A lysines 464 and 1250, since mutation of each results in channels with radically different kinetic properties. We demonstrate that K1250A, but not K464A, affects the opening rate. We also show that both K464A and K1250A affect closing at millimolar [ATP] but in opposite ways. K464A accelerates closing whereas K1250A delays it. These pronounced differences immediately suggest different roles for the two lysines in CFTR. These highly conserved lysines are thought to be critical for ATP hydrolysis in their respective domains and for the whole molecule (Ko & Pedersen, 1995; King & Sorscher, 1998; Ramjeesingh et al. 1999). If these lysines are truly critical for the function of their corresponding NBDs, the two NBDs are also functionally asymmetric. Based on that premise, our results suggests that: (1) while both NBDs are involved in nucleotide-dependent closing, each serves a different role; and (2) NBD2 is involved in opening (see below for further discussion). The idea that these two lysines are functionally different is supported by recent biochemical work. Ramjeesingh et al. (1999) showed that K464A only partly reduced CFTR's ATPase activity while K1250A eliminates it altogether. Aleksandrov et al. (2001) showed that K1250A had no effect on 8-azido-[α-32P]-ATP labelling of CFTR whereas K464A drastically reduced it. Moreover, a sequence comparison of the two NBDs reveals only ∼ 33 % similarity to each other, hinting at a divergence in NBD function (Manavalan et al. 1995; Nagel, 1999; Zou & Hwang, 2001).

In contrast to the idea of asymmetry, a recent study supported a model in which each NBD functions identically but with different ATP affinities (Ikuma & Welsh, 2000). This new model, similar to one proposed by Senior & Gadsby (1997) for P-glycoprotein, posited that at micromolar [ATP] NBD1 controls opening and closing and at millimolar [ATP] NBD2 does. According to that model, ATP binding opens the channel and unbinding or hydrolysis closes it. It was further hypothesized that hydrolysis is the main pathway for closing under normal conditions and that blocking hydrolysis with K464A or K1250A permits closing only through the slow unbinding pathway, resulting in prolonged openings. Based on that model, one would predict that the double mutant K464A-K1250A should exhibit long openings at all ATP concentrations, since the hydrolysis pathway at both NBDs is blocked. We find, however, that the mean open time for K464A-K1250A is ∼ 250 ms at 10 μm ATP and ∼ 30 s at 2.75 mm ATP (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8B). The double mutant open time at 10 μm ATP is similar to that of wild type, K464A and K1250A at the same [ATP] (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study). This finding, together with the dramatic differences between K464A and K1250A mutants, casts considerable doubt on the idea that the NBDs function identically. Thus, our findings, in conjunction with previous studies, support a hypothesis that the two NBDs are functionally, biochemically and perhaps structurally distinct.

Interaction between NBD1 and NBD2 during CFTR gating

In addition to functional asymmetry, our results suggest an interdependence between the two NBDs during gating. The first piece of evidence for NBD interaction comes from our analysis of AMP-PNP's effect on channel closing. AMP-PNP, a non-hydrolysable ATP analogue, greatly delays closing in wild type channels, evident as long open times, or locked open events. (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Mathews et al. 1998b; Zeltwanger et al. 1999). The frequency and duration of these locked open events in the presence of AMP-PNP are reduced by the NBD1 mutation K464A (Figs 4, 5 and 6). Several CFTR gating models propose that AMP-PNP binds to NBD2 to maintain the channel in the open state and that slow dissociation of this non-hydrolysable analogue from NBD2 accounts for the prolonged open time (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Sugita et al. 1998; Zeltwanger et al. 1999). The reduction of AMP-PNP's lock open effect by K464A then suggests that lysine 464 in NBD1 regulates nucleotide action at NBD2. We hypothesized in our previous work (Hwang et al. 1994; Zeltwanger et al. 1999) that NBD2 can bind ATP, like it does AMP-PNP, to prolong open time. The open time prolongation by ATP was not expected to be as pronounced as with AMP-PNP, because rapid hydrolysis at NBD2 would quickly terminate ATP's effect compared to the slow dissociation of non-hydrolysable AMP-PNP. Consistent with this expectation, increasing [ATP] from micromolar to millimolar lengthened mean open time in wild type CFTR by ∼ 50 %; this lengthening was attributed to ATP's action at NBD2 (Zeltwanger et al. 1999). Because K464A reduces the apparent on-rate (i.e. locking rate) of AMP-PNP (Fig. 6), we expected that this mutation should also impair ATP's ability to prolong open time. Indeed, K464A's mean open time at millimolar [ATP] is shorter compared to wild type (Fig. 3B), further corroborating that lysine 464 at NBD1 modulates nucleotide action at NBD2 (cf. Zeltwanger et al. 1999). Furthermore, the NBD2 mutation K1250A greatly prolongs CFTR open time ∼ 300-fold; that prolongation is then reduced ∼ 5-fold by addition of the NBD1 mutation K464A (Fig. 7). Based on gating models proposing that nucleotide action at NBD2 prolongs channel open time, this finding again suggests that lysine 464 modulates NBD2 in controlling channel closing.

Consistent with the idea that NBD1 affects NBD2, Aleksandrov et al. (2001) have shown that the presence of micromolar AMP-PNP at NBD1 could actually stimulate azido-ATP labelling at NBD2. The authors suggest that NBD1 controls nucleotide access to NBD2 allosterically. However, while their results indicate that AMP-PNP can act at NBD1, the precise location of where AMP-PNP acts to lock open CFTR is still open to debate. The data of Aleksandrov et al. (2001) also show diminished labelling of NBD2 by millimolar concentrations of AMP-PNP, suggesting that AMP-PNP can act at NBD2 as well. Correlating these biochemical findings with our electrophysiological results is difficult since both sets of experiments were performed under very different conditions. Nevertheless, irrespective of how nucleotides interact with the NBDs, the fact that a mutation in NBD1 affects the phenotype of an NBD2 mutant strongly suggests NBD-NBD interaction independent of any model for nucleotide-dependent CFTR gating.

Our demonstration of a functional interaction between CFTR's two NBDs is also corroborated by a recent biochemical study indicating physical contact between both domains (Lu & Pedersen, 2000). Lu & Pedersen (2000) also showed that NBD1-NBD2 interaction causes a conformational change in NBD2, suggestive of NBD1 regulation of NBD2 function. Furthermore, Ramjeesingh et al. (1999) showed that K464A reduces ATPase activity by ∼ 80 % and K1250A virtually eliminates it, suggesting that mutating one NBD affects the biochemical activity of the other. Thus, it is unlikely that each NBD acts independently.

Studies of several other ABC family members substantiate this notion of structural intimacy and functional interdependence between NBDs. Recent crystallographic studies of the NBDs from ABC superfamily members indicate not only a stable dimerization but also a sharing of structural elements between the nucleotide-binding clefts of these proteins (Diederichs et al. 2000; Hopfner et al. 2000; but cf. Hung et al. 1998). These structural overlaps in formation of the ATP-binding pockets within a dimer suggest the potential for functional interactions between the folds as well. Indeed, for several ABC proteins, mutations in either of the two NBDs eliminate the ATPase activity in both (for example, Hou et al. 2000; Alberts et al. 2001; Qu & Sharom, 2001), indicating a functional linkage between the domains. Since the structural and biochemical bases for the functional interaction between CFTR's NBD1 and NBD2 are, at the moment, unclear, more studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanism involved in functional NBD-NBD interactions.

Function of CFTR's NBDs in channel opening and closing

How then do the NBDs contribute to CFTR gating? First, we examine their roles in closing the channel. CFTR exhibits two distinct open states: (1) brief openings of ∼ 250 ms duration in micromolar [ATP]; and (2) longer openings in the presence of millimolar [ATP]. Brief openings at micromolar [ATP] occur independently of whether NBD1, NBD2 or both are mutated. Channel open times at 10 μm ATP for wild type, K464A, K1250A and K464A-K1250A are all ∼ 250 ms (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study, Fig. 3 and Fig. 8), indicating that the NBD mutations have no effect on brief openings. This observation supports the idea that once the channel is opened by ATP, no additional involvement of the NBDs is required to maintain channel opening for an average of 250 ms.

In contrast, openings with mean dwell times longer than 250 ms require the presence of millimolar [ATP] (Zeltwanger et al. 1999; present study, Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). The requirement for millimolar [ATP] to prolong opening compared to the micromolar [ATP] required for brief channel opening (for example, see Fig. 3A) suggests the presence of a low-affinity ATP site responsible for keeping the channel open. The presence of this second functional site for nucleotides is supported by earlier experiments with AMP-PNP. While unable to open CFTR, AMP-PNP can lock open the channel for tens of seconds (Gunderson & Kopito, 1994; Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Mathews et al. 1998b; Zeltwanger et al. 1999), reinforcing the idea that a second site prolongs open time. In addition to requiring millimolar nucleotide concentrations, these longer openings are affected by mutations at both NBDs. The NBD2 mutation K1250A prolongs opening (Fig. 7), which suggests that blocking ATP hydrolysis at NBD2 slows exit from an open state. On the other hand, the NBD1 mutation K464A shortens openings at millimolar [ATP] (Fig. 3). K464A also impairs AMP-PNP's ability to lock open CFTR and the channel's ability to remain locked open (Figs 4, 5 and 6), which implies that blocking hydrolysis at NBD1 impairs the ability to enter and remain in the longer open state. Thus, if indeed NBD2 functions to keep the channel open (Hwang et al. 1994; Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Zeltwanger et al. 1999), then our results suggest that lysine 464 at NBD1 helps NBD2 to perform this function.

What are the NBDs' roles in channel opening? Since ATP is required to open CFTR, there must be an ATP-binding site for this gating event. While our results provide no evidence for involvement of NBD1 in channel opening, NBD2 seems to play a role, since the NBD2 mutation K1250A increases closed time > 30-fold (Fig. 7). How does NBD2 control both opening and closing? One possible explanation is that NBD2 is used twice during the gating cycle. The first time, ATP binding followed by hydrolysis at NBD2 opens the channel. While the channel is still open, the hydrolysis products ADP and phosphate dissociate from the domain, freeing NBD2 to bind ATP again. If a new ATP does not bind NBD2, the channel opens for an average of ∼ 250 ms (see above). If ATP, or AMP-PNP, does bind NBD2 during this time window, then the channel remains open until hydrolysis or dissociation occurs, terminating NBD2 occupancy. Thus, one anatomical ATP-binding site can serve as two functional binding sites. In this scenario, hydrolysis at NBD2 permits a closed-to-open transition during its first action and an open-to-closed transition during its second.

Alternatively, NBD1, as previously proposed (Carson et al. 1995; Gunderson & Kopito, 1995; Zeltwanger et al. 1999), opens the channel. If so, why does the K464A mutation not affect the opening rate? There are two possible explanations for this observation: (1) ATP binding, but not hydrolysis at NBD1, opens the channel; or (2) NBD1′s role in channel opening is not revealed by the K464A mutation. Although biochemical studies show that K464A does impair ATPase activity in isolated NBD1 (Ko & Pedersen, 1995; King & Sorscher, 1998) as well as in the whole CFTR molecule (Ramjeesingh et al. 1999), the opening rate of K464A may not be affected if opening of CFTR only requires ATP binding. Two recent reports propose that ATP binding is sufficient for channel opening (Aleksandrov et al. 2000; Ikuma & Welsh, 2000). However, it is puzzling that mutations putatively affecting the nucleotide-binding pocket at NBD1 do not appear to affect channel opening (Berger & Welsh, 2000; Vergani et al. 2000).

Another possibility is that NBD1 may be involved in channel opening, but the domain's role is not revealed by the K464A mutation. Occlusion of NBD1 by covalent modification greatly impedes channel opening (Cotten & Welsh, 1998). Also, studies of the Walker-B and the LSGGQ motifs of NBD1 indicate that this domain may in fact play a role in channel opening (Carson & Welsh, 1995; Vergani et al. 2000). This contrast in effects may indicate that K464 does not play a noticeable role in NBD1 function during opening. However, caution is warranted in interpreting results from site-directed mutagenesis, because determining a mutation's localized effect at the target NBD is now complicated by its allosteric effect on the interacting NBD. This caveat becomes evident in our results as well as those from Aleksandrov et al. (2001). Further experiments are required to determine how NBD1 and NBD2 might colloborate in opening CFTR. If it turns out that NBD1 is truly involved in channel opening, then the delay of opening by NBD2 mutant K1250A would suggest that NBD1 and NBD2 interact to control opening as well as closing.

Conclusions

To examine the contribution of NBD1 during CFTR gating, we assessed the kinetic properties of the Walker-A mutant K464A. We found that K464A had little effect on the apparent ATP dependence or opening rate of the channel. However, the mutation did affect ATP-dependent prolongation of open time. K464A also diminished AMP-PNP's ability to stabilize channel open state by affecting both apparent on- and off-rates of the non-hydrolysable analogue. Finally, K464A reduces the prolongation of open time seen in the NBD2 mutant K1250A at millimolar [ATP], strongly suggesting an interaction between NBD1 and NBD2 during CFTR's open state. Although the NBD1 mutant K464A did not affect opening, the NBD2 mutant K1250A delays opening > 30-fold compared to wild type. Taken together, our results provide evidence for functional asymmetry and interdependence between the NBDs during the gating cycle. Specifically, our findings suggest that: (1) NBD2′s Walker-A lysine participates in both channel opening and closing; and (2) NBD1′s corresponding residue has a profound influence on NBD2′s regulation of channel closing, but not opening.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cindy Zhu for her invaluable expertise in the construction and transfection of the various CFTR mutants used in this study; Dr Mitchell Drumm and Dr Ronald Kopito for providing vectors and CFTR mutants; Dr László Csánady for freely sharing his analysis programs and his generous tutelage in using them; Dr Owen McManus and Dr Birgit Hirschberg for helpful discussions regarding the results; and Dr Silvia Bompadre and Dr Mark Milanick for their comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a UNCF-Merck Science Initiative postdoctoral fellowship (A. C. P.), a Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Grant (L. A.) and a National Institutes of Health R01 grant (T.-C. H.).

REFERENCES

- Alberts P, Daumke O, Deverson EV, Howard JC, Knittler MR. Distinct functional properties of the TAP subunits coordinate the nucleotide-dependent transport cycle. Current Biology. 2001;11:242–251. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov AA, Chang X, Aleksandrov L, Riordan JR. The non-hydrolytic pathway of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ion channel gating. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrov L, Mengos A, Chang X, Aleksandrov A, Riordan JR. Differential interactions of nucleotides at the two nucleotide binding domains of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:12918–12923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MP, Berger HA, Rich DP, Gregory RJ, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Nucleoside triphosphates are required to open the CFTR chloride channel. Cell. 1991;67:775–784. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MP, Welsh MJ. Regulation by ATP and ADP of CFTR chloride channels that contain mutant nucleotide-binding domains. Science. 1992;257:1701–1704. doi: 10.1126/science.1382316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Hwang T-C, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Coupling of CFTR Cl− channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 1994;12:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AL, Welsh MJ. Differences between cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and HisP in the interaction with the adenine ring of ATP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:29407–29412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger HA, Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, Howard PW, Maurer RA, Mulligan R, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Identification and regulation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-generated chloride channel. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88:1422–1431. doi: 10.1172/JCI115450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Travis SM, Welsh MJ. The two nucleotide-binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) have distinct functions in controlling channel activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1711–1717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Structural and functional similarities between the nucleotide-binding domains of CFTR and GTP-binding proteins. Biophysical Journal. 1995;69:2443–2448. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KW, Csánady L, Seto-Young D, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Severed molecules functionally define the boundaries of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator's NH2-terminal nucleotide binding domain. Journal of General Physiology. 2000;116:163–180. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten JF, Welsh MJ. Covalent modification of the nucleotide binding domains of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:31873–31879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csánady L. Rapid kinetic analysis of multichannel records by a simultaneous fit to all dwell-time histograms. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76636-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs K, Diez J, Greller G, Muller C, Breed J, Schnell C, Vonrhein C, Boos W, Welte W. Crystal structure of MalK, the ATPase subunit of the trehalose/maltose ABC transporter of the archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. EMBO Journal. 2000;19:5951–5961. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick EM, Marty A, Neher E. Sodium and calcium channels in bovine chromaffin cells. Journal of Physiology. 1982;331:599–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Control of CFTR channel gating by phosphorylation and nucleotide hydrolysis. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:s77–s107. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson KL, Kopito RR. Effects of pyrophosphate and nucleotide analogs suggest a role for ATP hydrolysis in cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator channel gating. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:19349–19353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson KL, Kopito RR. Conformational states of CFTR associated with channel gating: the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis. Cell. 1995;82:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland IB, Blight MA. ABC-ATPases, adaptable energy generators fuelling transmembrane movement of a variety of molecules in organisms from bacteria to humans. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;293:381–399. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell. 2000;101:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Cui L, Riordan JR, Chang X. Allosteric interactions between the two non-equivalent nucleotide binding domains of multidrug resistance protein MRP1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:20280–20287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung LW, Wang IX, Nikaido K, Liu PQ, Ames GF, Kim SH. Crystal structure of the ATP-binding subunit of an ABC transporter. Nature. 1998;396:703–707. doi: 10.1038/25393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang TC, Nagel G, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma M, Welsh MJ. Regulation of CFTR Cl− channel gating by ATP binding and hydrolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:8675–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140220597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Wong BS, Morris CE, Lecar H, Christian CN. Successive openings of the same acetylcholine receptor channel are correlated in open time. Biophysical Journal. 1983;42:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SA, Sorscher EJ. Recombinant synthesis of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and functional nucleotide-binding domains. Methods in Enzymology. 1998;292:686–697. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)92053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko YH, Pedersen PL. The first nucleotide binding fold of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator can function as an active ATPase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:20093–22096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu NT, Pedersen PL. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: the purified NBF1+R protein interacts with the purified NBF2 domain to form a stable NBF1+R/NBF2 complex while inducing a conformational change transmitted to the C-terminal region. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2000;375:7–20. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manavalan P, Dearborn DG, McPherson JM, Smith AE. Sequence homologies between nucleotide binding regions of CFTR and G-proteins suggest structural and functional similarities. FEBS Letters. 1995;366:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00463-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CJ, Tabcharani JA, Chang XB, Jensen TJ, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Dibasic protein kinase A sites regulate bursting rate and nucleotide sensitivity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Journal of Physiology. 1998a;508:365–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.365bq.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CJ, Tabcharani JA, Hanrahan JW. The CFTR chloride channel: nucleotide interactions and temperature-dependent gating. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1998b;163:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s002329900370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G. Differential function of the two nucleotide binding domains on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1999;1461:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel G, Hwang TC, Nastiuk KL, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. The protein kinase A-regulated cardiac Cl− channel resembles the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Nature. 1992;360:81–84. doi: 10.1038/360081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q, Sharom FJ. FRET analysis indicates that the two ATPase active sites of the P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter are closely associated. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1413–1422. doi: 10.1021/bi002035h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Garami E, Huan LJ, Galley K, Wang Y, Bear CE. Walker mutations reveal loose relationship between catalytic and channel-gating activities of purified CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) Biochemistry. 1999;38:1463–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi982243y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B-S, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou J-L, Drumm ML, Iannuzzi MC, Collins FS, Tsui L-C. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraste M, Sibbald PR, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop — a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior AE, Gadsby DC. ATP hydrolysis cycles and mechanism in P-glycoprotein and CFTR. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 1997;8:143–150. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:s23–s45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigworth FJ. The variance of sodium current fluctuations at the node of Ranvier. Journal of Physiology. 1980;307:97–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita M, Yue Y, Foskett JK. CFTR Cl− channel and CFTR-associated ATP channel: distinct pores regulated by common gates. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:898–908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venglarik CJ, Schultz BD, Frizzell RA, Bridges RJ. ATP alters current fluctuations of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator: evidence for a three-state activation mechanism. Journal of General Physiology. 1994;104:123–146. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergani P, Csánady L, Basso C, Sanchez R, Nairn AC, Gadsby DC. Mutations near the predicted catalytic site of NBD1 affect CFTR Cl− channel function surprisingly little. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:264A. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Zeltwanger S, Yang IC, Nairn AC, Hwang TC. Actions of genistein on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel gating. Evidence for two binding sites with opposite effects. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:477–490. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich F, Riordan JR, Nagel G. Dual effects of ADP and adenylylimidodiphosphate on CFTR channel kinetics show binding to two different nucleotide binding sites. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;114:55–70. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MC, Sheppard DN, Carson MR, Welsh MJ. Effect of ATP concentration on CFTR Cl− channels: a kinetic analysis of channel regulation. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1398–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80930-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltwanger S, Wang F, Wang GT, Gillis KD, Hwang TC. Gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels by adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis. Quantitative analysis of a cyclic gating scheme. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:541–554. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Hu S, Hwang TC. Voltage-dependent flickery block of an open cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel pore. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:435–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0435f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Hwang TC. ATP hydrolysis-coupled gating of CFTR chloride channels: structure and function. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5579–5586. doi: 10.1021/bi010133c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]