Abstract

We validated laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) for long-term monitoring and detection of acute changes of local cerebral blood flow (lCBF) in chronically instrumented fetal sheep. Using LDF, we estimated developmental changes of cerebral autoregulation. Single fibre laser probes (0.4 mm in diameter) were implanted in and surface probes were placed on the parietal cerebral cortex at 105 ± 2 (n = 7) and 120 ± 2 days gestational age (dGA, n = 7). Basal lCBF was monitored over 5 days followed by a hypercapnic challenge (fetal arterial partial pressure of CO2, Pa,CO2: 83 ± 3 mmHg) during which lCBF changes obtained by LDF were compared to those obtained with coloured microspheres (CMSs). Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was increased and decreased using phenylephrine and sodium nitroprusside at 110 ± 2 and 128 ± 2 dGA. Intracortical and cortical surface laser probes gave stable measurements over 5 days. The lCBF increase during hypercapnia obtained by LDF correlated well with flows obtained using CMS (r = 0.89, P < 0.01). The signals of intracortical and surface laser probes also correlated well (r = 0.91, P < 0.01). Gliosis of 0.35 ± 0.06 mm around the tip of intracortical probes did not affect the measurements. The range of MABP over which cerebral autoregulation was observed increased from 20–48 mmHg at 110 dGA to 35 to > 95 mmHg at 128 dGA (P < 0.05). Since MABP increased from 33 to 54 mmHg over this period (P < 0.01), the range between the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation and the MABP increased from 13 mmHg at 110 dGA to 19 mmHg at 128 dGA (P < 0.01). LDF is a reliable tool to assess dynamic changes in cerebral perfusion continuously in fetal sheep.

The efficiency of cerebral autoregulation is important in protecting the brain from both ischaemia during hypotension and haemorrhage during hypertension. Exact limits of cerebral autoregulation and their developmental changes in the fetus in vivo have not been determined. In part this is due to the fact that methods most commonly used to measure local cerebral blood flow (lCBF), such as the microsphere technique, only permit a limited number of static measurements. Thus, previous studies of cerebral autoregulation in the fetus have measured cerebral blood flow at only a few different blood pressure levels (Tweed et al. 1983; Ashwal et al. 1984; Papile et al. 1985; Szymonowicz et al. 1990; Helou et al. 1994). Exact limits of cerebral autoregulation are difficult to estimate without measurement of the CBF-mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) relationship based on multiple data pairs (Jones et al. 1999). To obtain the required measurements, we developed the ability to carry out laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) measurements in the chronically instrumented fetal sheep. LDF provides continuous monitoring of the capillary blood supply using the Doppler effect induced by moving red cells. LDF has been used successfully to examine the cerebral autoregulation response in the brain of adult rats (Dirnagl et al. 1989) as well as of newborn (Tuor & Grewal, 1994) and adult rabbits (Florence & Seylaz, 1992; Tuor & Grewal, 1994). The limitation of LDF is that it allows only relative and not absolute quantitative lCBF measurements (Dirnagl et al. 1989; Fabricius & Lauritzen, 1996) since the sensitivity of the method is affected by vascular bed geometry and optical properties of the tissue.

Although LDF has been used for several years in the postnatal brain some inherent methodical problems need to be solved to enable its application for chronic use in the brain of the unanaesthetised fetus in utero. Lan et al. (2000) have recently demonstrated how to fix laser probes at the skull to minimise sensitivity to movement artefacts. As a result, they were able to measure acute lCBF changes in the chronically instrumented fetal sheep.

However, further studies are clearly necessary to validate suitability of LDF for measurement in the freely moving fetus in utero and demonstrate its usefulness for chronic studies of fetal physiological responses. We, therefore, validated LDF as a technique for lCBF measurements in utero by comparing it with the well established coloured microsphere (CMS) technique in the chronically instrumented fetal sheep. We compared the reliability of blood flow values obtained by cortical surface and intracortical single fibre laser probes implanted in the cerebral cortex. Measurements using surface probes may be affected by surrounding amniotic fluid and those from intracortical probes may be affected by gliosis, which may be more prominent in the growing brain than the adult. We demonstrated the long-term stability of LDF measurements at two different gestational ages as a precondition for the use of chronically implanted probes. Following validation of the method, we determined limits of cerebral autoregulation by increasing and decreasing fetal MABP at 110 and at 128 days of gestation (dGA).

METHODS

Surgical procedure

Experimental procedures were approved by the animal welfare commission of Thuringia. Long-Wool Merino × German Blackheaded Mutton cross-bred ewes of known gestational age were brought into the animal facilities at least 5 days before surgery and kept in rooms with controlled light-dark cycles (12 h light-12 h dark: lights off at 6.00 p.m. and lights on at 6.00 a.m.). Hay, hay cubes and water were provided ad libitum. After food withdrawal for 24 h, surgery was performed at 105 ± 2 dGA (mean ± s.d., n = 7) or 120 ± 2 dGA (n = 7). Following 1 g of ketamine (Ketamin 10, Atarost, Germany) i.m., anaesthesia was induced by 4 % halothane (Fluothane, Zeneca, Germany) using a face mask. Ewes were intubated and anaesthesia was maintained with 1.0–1.5 % halothane in 100 % oxygen. Ewes were instrumented with catheters inserted into the common carotid artery for blood sampling, into the external jugular vein for post-operative administration of drugs and into the trachea to induce hypercapnia by CO2 insufflation.

Following hysterotomy, fetuses were instrumented with polyvinyl catheters (Rüschelit, Rüsch, Germany) inserted into the left common carotid artery for arterial blood pressure recordings, blood gas and reference blood sampling of microsphere measurements, into the left external jugular vein for drug application and into the saphenous vein for CMS injection. The tips of the catheters were advanced in the ascending aorta, the anterior and the posterior vena cava, respectively. Another catheter was placed in the amniotic cavity and amniotic pressure recordings were used to correct the fetal arterial blood pressure for the hydrostatic pressure. Wire electrodes (LIFYY, Metrofunk Kabel-Union, Berlin, Germany) were implanted into the left suprascapular muscles, muscles of the right shoulder and in the cartilage of the sternum for ECG (electrocardiogram) recording and into the uterine wall to record myometrial activity.

All ewes and fetuses received 0.5 g ampicillin (Ampicillin, Ratiopharm, Germany) intravenously and into the amniotic sac twice a day during the first three postoperative days. Metamizol (Arthripur, Atarost, Germany) was administered intravenously to the ewe (30–50 mg kg−1) as an analgesic for at least 3 days. All catheters were maintained patent via a continuous infusion of heparin at 15 IU ml−1 in 0.9 % NaCl solution delivered at 0.5 ml h−1.

In all animals, two intracortical single fibre laser probes (diameter 400 μm, Moor Instruments Ltd, Axminster, UK) were advanced 10 mm into the left and right parietal cortex through small burr holes in the skull placed 16 mm lateral and 6 mm posterior to bregma. In the younger fetuses, an additional surface laser probe (diameter 1.5 mm, No. DP5b, Moor Instruments) was placed on the intact dura after removing the skull bone 4 mm in diameter above the right parietal cortex 12 mm lateral and 12 mm posterior to bregma. Great care was taken to avoid the presence of large pial vessels below the laser probes that were clearly visible under an operating lamp. This precaution is necessary in order to ensure that the probe is recording only capillary blood supply since the autoregulatory response of cerebral vessels is size dependent with the most pronounced response occurring in small arterioles. All probes were fixed with dental cement on a single skull bone to avoid relative probe movement due to skull growth.

Data acquisition

Local CBF was measured continuously using a Laser Doppler Flowmeter (DRT4, Moor Instruments) with the maximal possible sampling rate of 40 s−1. Fetal arterial blood pressure and amniotic pressure were measured continuously using calibrated pressure transducers (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) connected to the fetal carotid and amniotic catheters. Arterial blood and amniotic pressures as well as the uterine electromyogram (EMG) and the ECG were amplified (Models 5900 and 6600, Gould, Valley View, OH, USA). All data were recorded throughout the experimental period on a multichannel chart recorder (TA11, Gould) with variable chart speeds of 2.5–25 mm min−1 depending on the experimental state. For further data processing data were stored on a hard disk of a PC using a 16 channel A/D board (DT 2801F, Data Translation, Marlborough, MA, USA). Flow data were digitised using a sample rate of 128 s−1 to meet the requirements of the Nyquist frequency. Simultanously, ECG was digitised with a sample rate of 1024 s−1, uterine EMG with 128 s−1 and MABP and amniotic pressures with 64 s−1.

Experimental protocol

Validation of laser Doppler flowmetry: long-term measurements

To validate the long-term stability of LDF measurements, continuous LDF measurements were made for 5 days starting within 11 ± 2 h post-surgery in all fetuses of both groups using the single fibre laser probes in the right parietal cortex and the surface laser probes above the right parietal cortex. Two intracortical and one surface laser probe in fetuses instrumented at 105 dGA were damaged or disconnected within the first postoperative day and could not be further used. To ensure stable physiological conditions, fetal and maternal arterial blood samples were taken daily at 8.00 a.m. for measurement of blood gases and pH using a blood gas analyser (ABL600, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark; measurements corrected to the ewe's body temperature measured rectally).

Validation of laser Doppler flowmetry with the microsphere technique and comparison of lCBF measurements obtained by intracortical and cortical surface laser probes

To validate lCBF changes detected by LDF, lCBF changes obtained by the intracortical laser probes were compared to the relative flow changes in the same brain region measured by the microsphere technique during an lCBF increase following a hypercapnic challenge. In addition, the agreement of LDF measurements obtained by intracortical and cortical surface laser probes were validated during the hypercapnic challenge in fetuses at 110 dGA where both types of probes were implanted.

Hypercapnia was induced at least 5 days after surgery in seven fetuses at 110 ± 2 dGA and six fetuses at 128 ± 2 dGA by insufflation of about 13 l CO2 min−1 into the ewe's trachea. Fetal arterial blood gases were taken before and every 4–5 min after the beginning of CO2 insufflation to monitor the increase of fetal arterial partial pressure of CO2 (Pa,CO2). CMS measurements were conducted in nine animals (five at 110 dGA and four at 128 dGA) 5 min before CO2 insufflation and 16–24 min after the beginning of the hypercapnic challenge when a fetal Pa,CO2 of more than 70 mmHg was achieved. To ensure reproducible experimental conditions, additional fetal and maternal arterial blood gas samples were taken immediately before baseline CMS injection and approximately 2 min before and immediately after CMS injection during hypercapnia. The mean of Pa,CO2 values obtained during the latter blood gas samplings was used to estimated the peak Pa,CO2 values that were correlated to LDF measurements. The local CBF increase obtained by the intracortical laser probes (between baseline CMS injection and CMS injection during hypercapnia) was correlated to the Pa,CO2 changes and compared to the relative flow changes in the same brain region measured by the microsphere technique. Altogether, the hypercapnic challenge lasted approximately 20–25 min.

CMSs were sonicated and vortexed for at least 10 min and drawn up into a sterile syringe immediately before injection. Approximately 106 CMSs of 15 μm diameter (Dye-Trak, Triton Technology, San Diego, CA, USA) were injected into the fetal posterior vena cava via the catheter in the saphenous vein. We avoided microsphere injection during myometrial contractures, which are known to be associated with changes in fetal blood pressure and heart rate (Brace & Brittingham, 1986). The number of CMSs injected was large enough to ensure an adequate number of CMSs per brain tissue sample (> 400) to meet the requirement of a systematic error of less than 10 % (Buckberg et al. 1971). We did not observe cardiovascular side effects of injection of this number of spheres. Beginning 25–30 s before CMS injection, a reference blood sample of 6 ml (1.5 ml NaCl solution from dead space of the catheter and 4.5 ml blood) was withdrawn from the ascending aorta into a heparinised glass syringe at a rate of 2 ml min−1 with a syringe pump (sp200i, World Precision Instruments, Berlin, Germany). The amount of blood withdrawn for CMS reference flows and for blood samples was replaced by maternal arterial blood immediately after withdrawal of each reference blood sample.

Estimation of the limits of cerebral autoregulation

Limits of cerebral autoregulation were explored during acute changes of MABP in seven fetal sheep at 110 ± 2 dGA and seven fetal sheep at 128 ± 2 dGA by continuous lCBF measurement using LDF. MABP was decreased or increased by stepwise infusion of sodium nitroprusside (SNP, 10 μg ml−1, infused at a rate of 0.2 − 0.8 ml min−1) or phenylephrine (PE, 25 μg ml−1, infused at a rate of 0.2–0.5 ml min−1) to the fetal jugular vein. The MABP was allowed to plateau at each infusion rate for a short steady state. Infusion rates were constant over 120 s in the 128 dGA fetuses and over 60 s in the fetuses at 110 dGA to avoid potential volume effects on MABP in the younger animals. Then, infusion rate was increased by 0.1 ml min−1.

Effects of direct infusion of SNP to the cerebral circulation were determined in three additional fetuses at 128 dGA to evaluate any potential direct vasodilative effect of SNP on cerebral vessels that may affect estimation of the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation. In these fetuses, catheters have been inserted into the lingual artery with the tips resting at the junction of the lingual and the carotid arteries without obstructing the carotid artery. We administered 1 μg ml−1 SNP corresponding to 10 % of the concentration used to estimate the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation directly into the right carotid artery because about 5 % of the cardiac output is distributed to the fetal brain (Rudolph & Heymann, 1967). Thus, the intracarotid SNP infusion introduced twice the amount of SNP into the cerebral circulation compared with the amount administered during the intravenous infusion used to study autoregulation.

Microsphere processing and histological examination of the brains

At the end of the experiment, ewes and their fetuses were killed by maternal intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (16 % solution, Narcoren, Merial, Germany). Fetal brains were perfused using 4 % formaldehyde after a short rinse with heparinised isotonic saline. Brain tissue samples weighing 0.5–2.0 g were dissected from the parietal cortex of the right hemisphere as close as possible to the tip of the intracortical laser probe while it remained in the tissue. CMSs in the reference blood samples and tissue samples were counted after digestion of the tissues and the blood as previously described in detail (Walter et al. 1997). Absolute flows were calculated by the formula flowtissue = number of microspherestissue × (flowreference/number of microspheresreference).

The left brain hemispheres with the tips of the single fibre probes remaining in the tissue were post-fixed for 1 week and embedded in paraffin. Coronal slices were stained with haematoxylin/eosin. The penetration canal was found in eight fetuses. The amount of gliosis around the tip of the intracortical laser probes was determined microscopically and quantified morphometrically using an image analysis program (Scion Image 1.62, Scion Corp., Frederick, MD, USA).

Data and statistical analysis

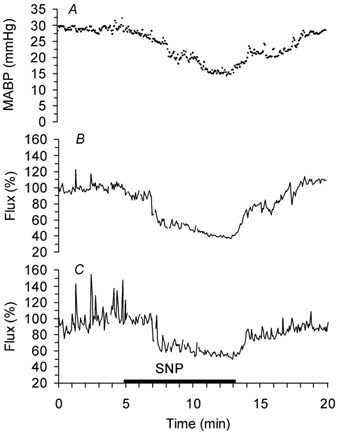

To reduce the amount of data, Laser Doppler and blood pressure data were averaged over 1 s before data analysis. Noise in the zero blood flow signal typically for LDF leads to a so called biological zero that is slightly above the electrical zero of the laser Doppler machine (Lan et al. 2000). Preliminary experiments have shown that the biological zero was 2.4 ± 0.4 % of baseline. This value was similar to that obtained by Lan et al. (2000) and was taken into consideration in calculation of all relative lCBF changes. Movement artefacts and noises were more common in the intracortical than in surface probes (Fig. 1) in part due to the smaller diameter of the glass fibres. These artefacts were easy to recognise due to their spike-like character (Fig. 1) and were removed manually during data evaluation.

Figure 1. Representative tracing of a MABP (A) decrease below the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation and of corresponding lCBF changes measured by a cortical surface (B) and an intracortical (C) laser probe before artefact rejection in a fetal sheep at 110 dGA.

SNP: infusion of sodium nitroprusside. The beginning of the lCBF decrease corresponding to the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation is clearly visible in spite of the spike-like artefacts. 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF.

All LDF values are given as flux relative to baseline. The absolute flows measured in arbitrary perfusion units depend on the placement of the probes because the velocity of the red cells is associated with the vessel size. Therefore the (absolute) arbitrary units are difficult to compare between different probes and correlate only poorly to other techniques of lCBF measurement (Fabricius & Lauritzen, 1996; Dirnagl et al. 1989). Fabricius & Lauritzen (1996) have shown that the relative lCBF changes obtained by LDF are independent of the baseline values. During long-term monitoring, flow values were averaged over the period of measurement and relative variation of each flow value from the average was calculated. Local CBF changes during hypercapnia and estimation of the limits of cerebral autoregulation were calculated relative to the mean flow over the 5 min directly prior to the hypercapnia or drug-induced change of MABP.

Limits of cerebral autoregulation were evaluated by comparing lCBF with MABP values over 2.5 mmHg intervals. The limit of cerebral autoregulation was considered as the point at which lCBF no longer remained stable in the face of changing MABP, i.e. as the point at which a significant difference between lCBF values that belong to ‘neighbouring’ 2.5 mmHg MABP intervals was reached.

Statistical significance between corresponding flow values and between corresponding Pa,CO2 values was tested using Wilcoxon's sign rank test. Statistical comparison of the biophysical parameters between the different gestational ages was performed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. The Spearman Correlation coefficient was used to prove correlations between flow values obtained by the cortical surface and intracortical laser probes, between flow values obtained during hypercapnia and the increase of Pa,CO2, and between flow values obtained by LDF and by the microsphere technique during hypercapnia. Additionally a two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements was used for interpretation of the lCBF increase during hypercapnia measured by the intracortical and surface laser probes. Significance was assumed at a P value < 0.05. All results are given as means ± s.e.m.

RESULTS

Validation of laser Doppler flowmetry

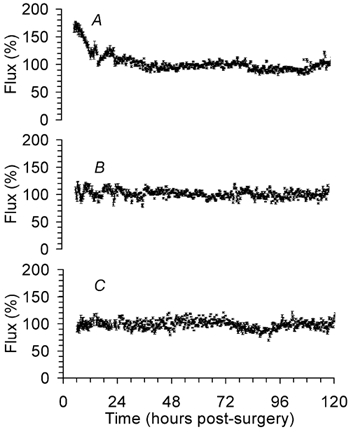

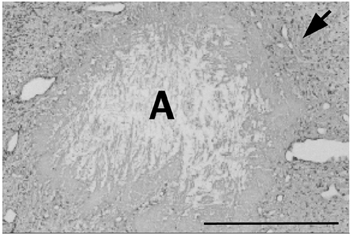

Blood gases, MABP and heart rate were in the physiological range at both gestational ages, although the Pa,O2 decreased slightly over 5 days in the older fetuses (Table 1). Continuous LDF measurements using intracortical flow probes showed stable lCBF values over 5 days in both groups (Fig. 2). Measurements did not vary more than 20 % around the mean in each animal. The cortical surface probes, however, showed a downward shift in the first hours of long-term measurements and needed about 24 h to equilibrate after which measurements were stable (Fig. 2). Gliosis was observed around the tip of the intracortical laser probes with a radius of 0.35 ± 0.06 mm (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Physiological parameters during long-term Laser Doppler flowmetry with recording beginning at 105 ± 2 and 120 ± 2 dGA

| 105 ± 2 dGA | 120 ± 2 dGA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Day 5 | Day 2 | Day 5 | |

| pH | 7.35 ± 0.02 | 7.37 ± 0.03 | 7.33 ± 0.02 | 7.31 ± 0.01 |

| Pa,CO2(mmHg) | 40 ± 2 | 39 ± 1 | 38 ± 3 | 41 ± 3 |

| Pa,O2 (mmHg) | 27 ± 2 | 28 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 24 ± 2* |

| MABP (mmHg) | 26 ± 5 | 24 ± 5 | 51 ± 2 | 53 ± 2 |

| HR (min−1) | 184 ± 5 | 182 ± 2 | 175 ± 5 | 177 ± 6 |

Values are means ±s.e.m.; n = 7 in both groups

P < 0.05 compared to day 2.

Figure 2. Long-term monitoring of baseline lCBF in the right parietal cortex of fetal sheep using laser Doppler flowmetry.

A, cortical surface laser probes in fetuses at 110 dGA (n = 6). B, intracortical laser probes in fetuses at 110 dGA (n = 5). C, intracortical laser probes in fetuses at 128 dGA (n = 7). Data are means ±s.e.m. Note the small s.e.m. indicating the small variation of the LDF measurement. 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF.

Figure 3. Example of the brain injury induced by an intracortical single fibre laser probe of 400 μm diameter (scale bar = 0.5 mm).

A: canal of the intracortical laser probe, arrow: surrounding gliosis.

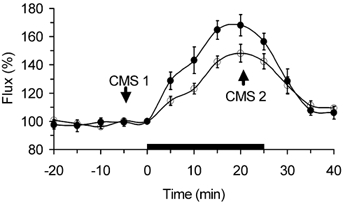

Insufflation of CO2 into the maternal trachea increased fetal Pa,CO2 from 42 ± 1 to 85 ± 3 mmHg (P < 0.01). Local CBF increased by 68 ± 8 % as measured by intracortical laser probes and by 48 ± 6 % as measured by cortical surface laser probes in fetuses at 110 dGA (both probes P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4). Local CBF changes measured by both probes showed a good correlation during the hypercapnic challenge (r = 0.91, P < 0.01, Fig. 4). Intracortical laser probes, however, produced a noisier signal.

Figure 4. Time course of lCBF changes during maternal hypercapnia (black bar) measured by cortical surface (○, n = 6) and intracortical (•, n = 5) laser probes in fetal sheep at 110 dGA.

Data are means ±s.e.m. Both probes correlate with r = 0.91 (P < 0.01). Arrows indicate CBF measurement using coloured microspheres before (CMS1) and during hypercapnia (CMS2). 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF.

While lCBF changes over the time were the main source of variation (80.7 % of total variation), variation between lCBF increases measured by the intracortical and cortical surface laser probes was only 1.8 % of total variation (P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). In addition, there was a small interaction between the lCBF increase over the time and the probe type (4.0 % of total variation, P < 0.01). Taken together, effects of the probe type on lCBF measurement make only a minor contribution to the flow changes observed.

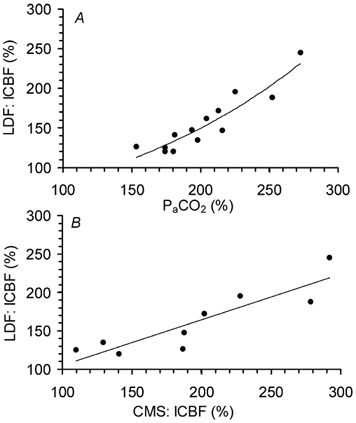

The increase in lCBF correlated with both the absolute fetal Pa,CO2 values (r = 0.68, P < 0.05) as well as with the Pa,CO2 increase relative to baseline values (r = 0.92, P < 0.01, Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Correlation of lCBF obtained by laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) to Pa,CO2 (A) and to lCBF obtained by coloured microspheres (CMS, B) during a hypercapnic challenge.

Measurements of the intracortical laser probes at both gestational ages are shown. Each point refers to one animal. 100 % corresponds to baseline. A: n = 13, r = 0.92; B: n = 9, r = 0.89, P < 0.05.

Measurement of absolute lCBF during hypercapnia using CMS indicated a baseline flow to the right parietal cortex of 88 ± 15 ml (100 g)−1 min−1 at 110 dGA and of 76 ± 11 ml (100 g)−1 min−1 at 128 dGA. During the hypercapnic challenge parietal cortical blood flow increased to 135 ± 10 ml (100 g)−1 min−1 at 110 dGA (P < 0.05) and to 178 ± 43 ml (100 g)−1 min−1 at 128 dGA (P < 0.05). Local CBF increase measured by intracortical laser probes correlated significantly to that obtained by CMSs in the same area of the right hemisphere (r = 0.89, P < 0.01, Fig. 5).

Limits of cerebral autoregulation

Blood gases, MABP and heart rate were in the physiological range at the beginning of the cerebral autoregulation study. The fetuses at 110 dGA and 128 dGA did not show statistical differences in pH (7.34 ± 0.01 vs. 7.33 ± 0.01), Pa,CO2 (39 ± 1 vs. 38 ± 2 mmHg) and Pa,O2 (26 ± 1 vs. 25 ± 1 mmHg). Resting blood pressure increased significantly between 110 and 128 dGA from 33 ± 3 to 54 ± 2 mmHg (P < 0.01) while heart rate decreased significantly from 182 ± 2 beats min−1 at 110 dGA to 171 ± 4 beats min−1 at 128 dGA (P < 0.05).

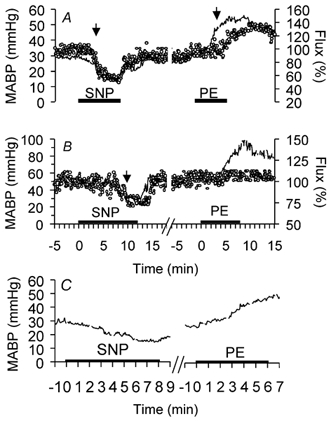

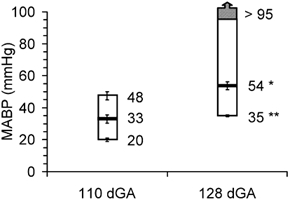

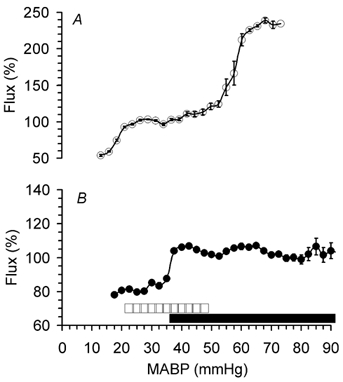

Acute changes of MABP outside limits of cerebral autoregulation were accompanied by corresponding lCBF changes (Fig. 6). As during the hypercapnic challenge, lCBF values measured by the intracortical and cortical surface laser probes showed a good correlation during SNP (r = 0.82, P < 0.001) and PE infusions (r = 0.89, P < 0.001). During SNP infusion, MABP began to decrease at a constant lCBF (Fig. 6). The point at which a significant decrease of lCBF occurred was taken as the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation. This lower limit was at a MABP of 20 ± 1 mmHg at 110 dGA and at a MABP of 35 ± 1 mmHg at 128 dGA (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, P < 0.05). During PE infusion, MABP increased at a constant lCBF at both gestational ages. (Fig. 6). Local CBF started to increase at 48 ± 3 mmHg in fetuses at 110 dGA indicating the upper limit of cerebral autoregulation (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, P < 0.05). In fetuses at 128 dGA, the upper limit of cerebral autoregulation was not reached even though systemic MABP was increased from 54 ± 2 to 95 mmHg (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

Figure 6. Time course of fetal MABP (line) and lCBF changes (circles) during sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and phenylephrine (PE) infusions (black bars) measured by an intracortical single fibre probe in a fetal sheep at 110 dGA (A) and at 128 dGA (B). C shows in higher time resolution the stepwise decrease and increase of MABP in the same animal as in A.

Note the lower and upper limit of cerebral autoregulation (arrows). The upper limit of cerebral autoregulation was not reached at 128 dGA (B). 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF.

Figure 7. Baseline mean arterial blood pressures (MABP, black bar), lower and upper limits of cerebral autoregulation in fetal sheep at 110 and 128 dGA.

Data are means ±s.e.m., n = 7 in each group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to 110 dGA.

Figure 8. Developmental changes of the limits of cerebral autoregulation in the cortex of fetal sheep between 110 (A) and 128 dGA (B).

The range of MABP over which cerebral autoregulation was observed is indicated by the white (110 dGA) and black (128 dGA) bars. 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF. Data are means with s.e.m. indicated unless it is smaller than the symbols, n = 7 in each group.

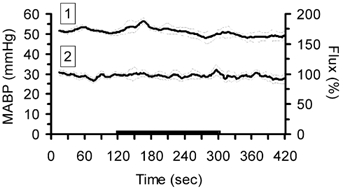

There was no effect of direct intracarotid infusion of SNP on lCBF and systemic blood pressure (Fig. 9). Therefore, potential direct local vasodilator effects of SNP on cerebral vessels that would affect estimation of the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation can be excluded at the dosage used.

Figure 9. MABP (1) and lCBF (2) obtained by intracortical laser probes during infusion of sodium nitroprusside (black bar) directly into the fetal carotid artery at 128 dGA.

Data are means ±s.e.m., n = 3. Note that neither the MABP nor the lCBF were affected by the infusion. 100 % corresponds to baseline lCBF.

DISCUSSION

In the present study conducted in chronically instrumented fetal sheep at 110 and 128 dGA, LDF proved to be a reliable method for monitoring continuously lCBF during long-term measurements as well as acute blood flow changes in the unanaesthetised fetal sheep in utero. Our study extended a recent paper that has demonstrated the feasibility of LDF measurements of acute lCBF changes during hypoxaemia in fetal sheep at 125–127 dGA using intracortical laser Doppler probes (Lan et al. 2000). Using both cortical surface and intracortical single fibre probes, we were able to obtain stable laser Doppler signals that showed a good correlation between both probes. In addition, we validated LDF flow measurements by comparing them to the lCBF changes obtained simultaneously by the CMS technique in the same animals at the same time. The assessment we made of dynamic changes in cerebral capillary system perfusion allowed exact determination of limits of cerebral autoregulation. The limits and range of MABP over which cerebral autoregulation was observed increased during development in association with the increase in resting blood pressure.

Validation of the laser flow probes

The use of both cortical surface and intracortical single fibre probes has advantages and disadvantages. Intracortical single fibre probes can be implanted in almost any region of the brain. Although they induce brain injury, the good correlation of the lCBF changes obtained by intracortical and surface laser probes (which are not susceptible to gliosis) suggests that gliosis around the tip of the intracortical probes does not significantly change the flows. Indeed, the estimated penetration depth of the laser light is 1 mm (Stern et al. 1977; Haberl et al. 1989), that is about three times deeper than the gliosis around the tip of the intracortical probes. However, the intracortical laser probes are more sensitive to movement artefacts and produced a noisier signal than surface laser probes due to the small diameter of the single fibres. Our own unpublished observations indicate that smaller intracortical single fibre probes with a diameter of 200 μm produce an even noisier signal although the local histological changes are minimised. Moreover, a decrease of fibre diameter leads to a decrease of sampling depth (Jakobsson & Nilsson, 1993). When sampling depth is decreased, equivalent amounts of gliosis around the tip of the laser probes will have a greater effect on the measurements obtained. Therefore, there is a trade off between size of fibre and accuracy of results.

Surface laser probes can be fixed to the skull bones through a small window in the bone, thereby keeping the dura and the brain tissue intact. Laser data of Kuchiwaki et al. (1991) showed a temporary increase of CBF for about 4 h revealing an initial hyperaemic period during stabilisation as we have shown for the surface probes, too.

Validation of laser Doppler flowmetry with the microsphere technique

The correlation of 0.89 between relative lCBF changes obtained by LDF and CMS found in our study was similar to that obtained in the adult cat brain obtained by hydrogen clearance (Haberl et al. 1989) and in the adult rat brain obtained by hydrogen clearance (Skarphedinsson et al. 1988) or 14C iodoantipyrine autoradiography (Dirnagl et al. 1989). The accuracy of LDF in detection of relative lCBF changes has also been demonstrated in the adult brain by comparison with results obtained by the microsphere technique (Eyre et al. 1988) or estimation of pial arteriolar diameter (Haberl et al. 1989). The poor agreement of LDF and the microsphere technique in our study in spite of the excellent correlation resulted in an underestimation of the flow changes detected by LDF. In contrast, Fabricius & Lauritzen (1996) have shown an overestimation of lCBF increases detected by LDF in comparison to the 14C-iodoantipyrine autoradiography in the adult rat brain. They assumed that this was due to dissociation of the velocity of red cells and plasma in the capillary system during a lCBF increase since the volume and velocity of red cells detected by LDF increases more than plasma flow due to an opening of additional capillaries (Fabricius & Lauritzen, 1996). Comparing LDF with the microsphere technique is an appropriate way to validate LDF because microspheres and red cells distribute similarly in the circulation. However, previous studies did not show good absolute agreement of both methods in spite of good correlation (Lindsberg et al. 1989; Colditz et al. 1993). These systematically differing flow changes detected by LDF seem to occur specifically during lCBF increases while the slope of the regression line between lCBF changes obtained by LDF and 14C-iodoantipyrine autoradiography (Dirnagl et al. 1989) or hydrogen clearence (Skarphedinsson et al. 1988; Haberl et al. 1989) is reported as being approximately 0.9 at a reduced lCBF in the adult rat brain. We did not examine the correlation during a decrease in lCBF since withdrawal of reference blood for CMS measurements during a MABP decrease below the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation may compromise the condition of the fetus. It must be acknowledged that the tissue sampled by the LDF is approximately 1 mm3 (Stern et al. 1977; Haberl et al. 1989), which is considerably smaller than that sampled by the microsphere technique. The microsphere technique requires brain samples of approximately 0.5–2.0 g and will inevitably contain a different mix of cells, grey and white matter. The excellent correlation is strong evidence for the validity of the method although the slope of the regression line is not 1.0.

Estimation of the limits of cerebral autoregulation

The ability of LDF to monitor changes in lCBF continuously allowed us to determine exact limits of cerebral autoregulation and its developmental changes in the unanaesthetised fetal sheep in utero. Previous studies have used the microsphere technique to estimate the limits of cerebral autoregulation in fetal sheep. We observed a clear developmental increase of both the lower and upper limit of cerebral autoregulation in the cerebral cortex with a clearly detectable autoregulatory response at 110 dGA. Earlier in gestation, an inconsistent global cerebral autoregulatory response was found in the entire cerebrum at 92 dGA during reductions of cerebral perfusion pressure by ventricular fluid infusion (Helou et al. 1994). At 90–100 dGA, Szymonowicz et al. (1990) could only demonstrate an autoregulatory response in the brainstem during haemorrhagic hypotension. The lower limit of cerebral autoregulation was 39 mmHg and already higher than that found in our study in the cerebral cortex at 110 dGA. This supports the assumption that cerebral autoregulation develops first in the more ancient cytoarchitectural structures as the brainstem and subcortical regions (Szymonowicz et al. 1990; Helou et al. 1994; Tuor & Grewal, 1994). All these studies conducted early in gestation did not investigate the upper limit of cerebral autoregulation. A consistent global autoregulatory response was first found at 118–122 dGA after aortic and brachicephalic occlusions in fetal sheep with chronic sinoaortic denervation (Papile et al. 1985). The autoregulatory range reported in that study was 45 − 80 mmHg. However, autoregulatory ranges given for the sheep fetus from this age onwards differ considerably probably due to the limited number of repeated measurements with the microsphere technique, the brain regions under investigation, the different methods of inducing changes in blood pressure and the wide ranges of gestational ages that were averaged. Thus, Ashwal et al. (1984) have shown sufficient cerebral autoregulation in all major brain regions over the range of 30–78 mmHg at 124–146 dGA by rapidly bleeding or transfusing the fetus. Szymonowicz et al. (1990) determined the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation during haemorrhagic hypo tension at 45 mmHg in the cerebral cortex at 125–136 dGA. Tweed et al. (1983) showed using blood withdrawal and retransfusion that CBF to all major brain regions is autoregulated between 42 and 62 mmHg at 130–140 dGA. But they did not determine the limits of cerebral autoregulation. Using the 133Xe-clearence technique, Purves & James (1969) found cerebral autoregulation in the grey matter over the range of 43–90 mmHg after hypercapnia and administration of catecholamines in exteriorised anaesthetised fetal sheep at 135–150 dGA.

None of these earlier studies provide any information on the time course of development of cerebral autoregulation once the cerebral autoregulatory response begins to mature. The gestational age between 100 and 118 dGA at which cerebral autoregulation seemed to mature was not investigated. The wide ranges of gestational ages that were averaged made it difficult to determine the time course of development. The need to calculate the MABP : CBF ratio from flow values obtained at different MABP values in several animals due to the limited number of repeated lCBF measurements with the microsphere technique (Papile et al. 1985) might have caused the variations in the results. Importantly, results of some of these studies are undoubtedly affected by performing the experiments at the first postoperative day (Tweed et al. 1983; Papile et al. 1985; Helou et al. 1994). Halothane used for anaesthesia (Papile et al. 1985; Helou et al. 1994) increases CBF in the postnatal brain (Anderson et al. 1980; Bazin, 1997) and alters cerebrovascular reactivity and autoregulation (Drummond et al. 1987; Ipsiroglu et al. 2000).

Taken together, our studies extend previous observations in two major ways. First, we could demonstrate that cerebral autoregulation in response to a blood pressure increase and decrease is present by as early as 110 dGA in the cerebral cortex. Secondly, we were able to characterise the development in the range of MABP over which cortical blood flow is autoregulated. The upper limit of cerebral autoregulation seems to mature faster, increasing the range of MABP over which autoregulation was observed.

The increase of both the lower and upper limit of cerebral autoregulation parallels the developmental increase in resting blood pressure. Although cerebral autoregulation was present at 110 dGA, resting arterial blood pressure was still close to the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation at this stage of development. The poor autoregulatory capacity that accompanies a fall in blood pressure leads to cerebral hypoperfusion and may place the premature fetal brain at risk of injury in the arterial ‘watershed zones’ of periventricular regions (Lou, 1994; Reddy et al. 1998). The immature autoregulatory capacity during hyperaemia may also contribute to the vulnerability of the premature brain to haemorrhage (Reynolds et al. 1979; Lou, 1993). In comparison to the developmental increase of resting MABP the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation increased only slowly. The small difference of 13 mmHg between the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation and the resting MABP at 110 dGA is similar to the differences of about 9 mmHg and 15 mmHg estimated in previous studies at 118–122 dGA (Papile et al. 1985) and 120–140 dGA (Ashwal et al. 1984), respectively. In contrast to our finding of a developmental increase in the difference between the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation and the resting MABP that reached 19 mmHg at 128 dGA, Szymonowicz et al. (1990) determined that the resting MABP in the cerebral cortex was identical to the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation at this gestational age. On the other hand, Purves & James (1969) found that the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation in the grey matter in exteriorised anaesthetised fetal sheep at 135–150 dGA is about 30 mmHg below the MABP.

Determination of the limits of cerebral autoregulation using vasoactive drugs requires that the drugs themselves do not affect cerebrovascular tone directly. Previous studies have shown that concentrations of PE similar to those we used do not affect cerebral autoregulatory response in newborn sheep (Ong et al. 1986). Reports on the effects of nitric oxide (NO) on cerebral autoregulation are controversial. In several species systemic administration of NO synthase inhibitors indicated that NO is not involved in the autoregulatory response to marked decreases in MABP (Wang et al. 1992; Buchanan & Phillis, 1993; Meadow et al. 1994; Saito et al. 1994; Thompson et al. 1996). Other studies in the adult brain have suggested that NO is at least one of the mediators of vasodilatation near the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation demonstrating a rise in the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation after inhibition of NO synthase in the brain (Kobari et al. 1994; Jones et al. 1999) or a decrease after infusion of SNP as a NO donator (Stange et al. 1991; Tsutsui et al. 1995). To exclude a potential direct NO effect on cerebral vasculature in our study, we tested the direct effect of SNP on the cerebral circulation. Direct intracarotid infusion of twice the amount of SNP that would be distributed to the brain after intravenous infusion did not provoke any change in cerebral perfusion. This observation is in agreement with one previous study in neonatal lambs in which the cerebral circulation was perfused with a tenfold higher concentration of SNP than we used (Ong et al. 1986). One of the reasons for the lack of a direct SNP effect on cerebral vasculature in our study is probably that we examined fetuses and the effect of NO in mediating cerebral vasodilatation increases with age (Armstead et al. 1994; Zuckerman et al. 1996; Willis & Leffler, 1999). Moreover, the total dose of SNP used by Stange et al. (1991) (1.3 ± 0.2 mg kg−1) and Tsutsui et al. (1995) (1.0 mg kg−1) that led to a decrease of the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation in anaesthetised young pigs and adult rats, respectively, was much higher than that used in our study of up to 23 μg kg−1 at 110 dGA and up to 10 μg kg−1 at 128 dGA.

The whole body SNP infusion should not lead to plasma levels in excess of those infused directly into the lingual artery because SNP has a short dose-dependent plasma half-life (Friederich & Butterworth, 1995). At the dose used plasma half-life is much less than 2 min. Thus, SNP does not alter lCBF directly in the fetal brain at concentrations that decrease MABP significantly from its resting level. This lack of a NO-dependent action in regulating cerebral perfusion in the fetus and newborn is likely to reflect the fact that the major regulation is prostaglandin dependent (Chemtob et al. 1990; Meadow et al. 1994).

In conclusion, LDF provides a reliable tool to assess dynamic changes in cerebral perfusion continuously in the fetal brain in utero. Although LDF allows only relative and not quantitative measurements in terms of volume per unit time and weight of tissue (Eyre et al. 1988; Skarphedinsson et al. 1988; Dirnagl et al. 1989; Haberl et al. 1989; Tuor & Grewal, 1994; Fabricius & Lauritzen, 1996) the method will be of importance in monitoring the time course of relative changes of lCBF in utero. As a result the use of LDF can provide critical information on the pathophysiological processes of cerebral ischaemic insults such as occur during repetitive umbilical cord occlusion. Using LDF we were able to determine developmental changes of the limits of cerebral autoregulation. Our results indicate that the immature brain is especially susceptible to ischaemia during hypotension and haemorrhage during hypertension.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Petra Dobermann for surgical assistance, Claudia Hiepe for histological processing and Ute Jaeger for processing the coloured microspheres. This work was supported by the Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina and the Verbund Klinische Forschung at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena.

REFERENCES

- Anderson RE, Michenfelder JD, Sundt TM. Brain intracellular pH, blood flow, and blood-brain barrier differences with barbiturate and halothane anesthesia in the cat. Anesthesiology. 1980;52:201–206. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Zuckerman SL, Shibata M, Parfenova H, Leffler CW. Different pial arteriolar responses to acetylcholine in the newborn and juvenile pig. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1994;14:1088–1095. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal S, Dale PS, Longo LD. Regional cerebral blood flow: studies in the fetal lamb during hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis, and hypotension. Pediatric Research. 1984;18:1309–1316. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazin JE. Effects of anesthetic agents on intracranial pressure. Annales Françaises d’ Anesthésie et de Réanimation. 1997;16:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(97)81477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brace RA, Brittingham DS. Fetal vascular pressure and heart rate responses to nonlabor uterine contractions. American Journal of Physiology. 1986;251:R409–416. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JE, Phillis JW. The role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cerrebral blood flow. Brain Research. 1993;610:248–255. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91408-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckberg GD, Luck JC, Payne DB, Hoffman JI, Archie JP, Fixler DE. Some sources of error in measuring regional blood flow with radioactive microspheres. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1971;31:598–604. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob S, Beharry K, Rex J, Varma DR, Aranda JV. Prostanoids determine the range of cerebral blood flow autoregulation of newborn piglets. Stroke. 1990;21:777–784. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz PB, Bartholomew PH, Sinclair JI, Murphy D, Rolfe P, Wilkinson AR. Electrical impedance plethysmography: its use in studying the cerebral circulation of the rabbit. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing. 1993;31:39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02446883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Kaplan B, Jacewicz M, Pulsinelli W. Continuous measurement of cerebral cortical blood flow by Laser-Doppler flowmetry in a rat stroke model. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1989;9:589–596. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond JC, Scheller MS, Todd MM. The effect of nitrous oxide on cortical cerebral blood flow during anesthesia with halothane and isoflurane, with and without morphine, in the rabbit. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1987;66:1083–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre JT, Essex TJH, Flecknell PA, Bartholomew PH, Sinclair JI. A comparison of measurements of cerebral blood flow in the rabbit using laser-Doppler spectroscopy and radionuclide labeled microspheres. Clinical Physics and Physiological Measurement. 1988;9:65–74. doi: 10.1088/0143-0815/9/1/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius M, Lauritzen M. Laser-Doppler evaluation of rat brain microcirculation: comparison with the [14C]-iodoantipyrine method suggests discordance during cerebral blood flow increases. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1996;16:156–161. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence G, Seylaz J. Rapid autoregulation of cerebral blood flow: A Laser-Doppler Flowmetry study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1992;12:674–680. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederich JA, Butterworth JFIV. Sodium nitroprusside: twenty years and counting. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1995;81:152–162. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199507000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberl RL, Heizer ML, Maramarou A, Ellis EF. Laser-Doppler assessment of brain microcirculation: effect of systemic alterations. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:H1255–1260. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helou S, Koehler R, Gleason C, Jones DM, Traystman RJ. Cerebrovascular autoregulation during fetal development in sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:H1069–1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.3.H1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipsiroglu OS, Kohler J, Meger B, Pumberger W, Grabner C, Semsroth M. Orthostasis in halothane anesthesia. A model situation for studying cerebrovascular autoregulation in infants. Anaesthesist. 2000;49:511–515. doi: 10.1007/s001010070091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson A, Nilsson GE. Prediction of sampling depth and photon pathlength in laser Doppler flowmetry. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing. 1993;31:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02458050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Radinsky CR, Furlan AJ, Chyatte D, Perez Trepichio AD. Cortical NOS inhibition raises the lower limit of cerebral blood flow-arterial pressure autoregulation. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:H1253–1262. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobari M, Fukuuchi Y, Tomita M, Tanahashi N, Takeda H. Role of nitric oxide in regulation of cerebral microvascular tone and autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in cats. Brain Research. 1994;667:255–262. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchiwaki H, Inao S, Kashima S. An experimental study of cerebral blood flow and some considerations on obtaining reliable data using a Laser Flow Meter. Laser Therapy. 1991;3:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lan J, Hunter CJ, Murata T, Power GG. Adaptation of laser-Doppler flowmetry to measure cerebral blood flow in the fetal sheep. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;89:1065–1071. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsberg PJ, O'Neill JT, Paakkari IA, Hallenbeck JM, Feuerstein G. Validation of laser-Doppler flowmetry in measurement of spinal cord blood flow. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:H674–680. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.2.H674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou HC. On the pathogenesis of germinal layer hemorrhage in the neonate. APMIS Supplements. 1993;40:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou HC. Hypoxic-hemodynamic pathogenesis of brain lesions in the newborn. Brain Development. 1994;16:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadow W, Rudinsky B, Bell A, Lozon M, Randle C, Hipps R. The role of prostaglandins and endothelium-derived relaxation factor in the regulation of cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen utilization in the piglet: operationalizing the concept of an essential circulation. Pediatric Research. 1994;35:649–656. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong BY, MacIntyre C, Bose D, Palahniuk RJ. Comparison of two methods of altering blood pressures for assessing neonatal cerebral blood flow autoregulation. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1986;64:1023–1026. doi: 10.1139/y86-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papile LA, Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in the preterm fetal lamb. Pediatric Research. 1985;19:159–161. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves MJ, James IM. Observations on the control of cerebral blood flow in the sheep fetus and newborn lamb. Circulation Research. 1969;25:651–667. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy K, Mallard C, Guan J, Marks K, Bennet L, Gunning M, Gunn A, Gluckman P, Williams C. Maturational change in the cortical response to hypoperfusion injury in the fetal sheep. Pediatric Research. 1998;43:674–682. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds ML, Evans CA, Reynolds EO, Saunders NR, Durbin GM, Wigglesworth JS. Intracranial haemorrhage in the preterm sheep fetus. Early Human Development. 1979;3:163–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. The circulation of the fetus in utero. Methods for studying distribution of blood flow, cardiac output and organ blood flow. Circulation Research. 1967;21:163–184. doi: 10.1161/01.res.21.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Wilson DA, Hanley DF, Traystman RJ. Nitric oxide synthase does not contribute to cerebral autoregulatory phenomenon in anesthetized dogs. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1994;49:S73–76. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarphedinsson JO, Harding H, Thoren P. Repeated measurements of cerebral blood flow in rats. Comparisons between the hydrogen clearance method and Laser Doppler flowmetry. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1988;134:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1988.tb08469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange K, Lagerkranser M, Sollevi A. Nitroprusside-induced hypotension and cerebrovascular autoregulation in the anesthetized pig. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1991;73:745–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern MD, Lappe DL, Bowen PD, Chimosky JE, Holloway GA, Jr, Keiser HR, Bowman RL. Continuos measurement of tissue blood flow by Laser-Doppler spectroscopy. American Journal of Physiology. 1977;232:H441–448. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1977.232.4.H441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymonowicz W, Walker AM, Yu VY, Stewart ML, Cannata J, Cussen L. Regional cerebral blood flow after hemorrhagic hypotension in the preterm, near-term, and newborn lamb. Pediatric Research. 1990;28:361–366. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BG, Pluta RM, Girton ME, Oldfield EH. Nitric oxide mediation of chemoregulation but not autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in primates. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1996;84:71–78. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.1.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui T, Maekawa T, Goodchild C, Jones JG. Cerebral blood flow distribution during induced hypotension with haemorrhage, trimetaphan or nitroprusside in rats. British Journal of Anaesthesiology. 1995;74:686–690. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.6.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuor UI, Grewal D. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow: influence of local brain development and postnatal age. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:H2220–2228. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.6.H2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweed WA, Cote J, Pash M, Lou H. Arterial oxygenation determines autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in the fetal lamb. Pediatric Research. 1983;17:246–249. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter B, Bauer R, Gaser E, Zwiener U. Validation of the multiple colored microsphere technique for regional blood flow measurements in newborn piglets. Basic Research in Cardiology. 1997;92:191–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00788636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Paulson OB, Lassen NA. Is autoregulation of cerebral blood flow inrats influenced by nitro-L-arginine, a blocker of the synthesis of nitric oxide. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1992;145:297–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis AP, Leffler CW. No and prostanodi:age dependence of hypercapniaand histamine-induced dilations of pig pial arterioles. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:H299–307. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.H299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman SL, Armstead WM, Hsu P, Shibata M, Leffler CW. Age dependence of cerebrovascular response mechanisms in domestic pigs. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:H535–540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]