Abstract

The adhesive force generated by the interaction of integrin receptors with extracellular matrix (ECM) at the focal adhesion complex may regulate endothelial cell shape, and thereby the endothelial barrier function. We studied the role of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) activated by integrin signalling in regulating cell shape using cultured human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. We used FAK antisense oligonucleotide (targeted to the 3′-untranslated region of FAK mRNA (5′-CTCTGGTTGATGGGATTG-3′) to determine the role of FAK in the mechanism of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability. Reduction in FAK expression by the antisense augmented the thrombin-induced decrease in transendothelial electrical resistance (decrease in mock transfected cells of −43 ± 1 % and in sense-transfected cells of −40 ± 4 %, compared to the decrease in antisense-transfected cells of −60 ± 3 %). Reduction in FAK expression also prolonged the drop in electrical resistance and prevented the recovery seen in control endothelial cells. Thus, the thrombin-induced increase in permeability is both greater and attenuated in the absence of FAK expression. Inhibition of actin polymerization with latrunculin-A prevented the translocation of FAK to focal adhesion sites and tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin, and concomitantly reduced the thrombin-induced decrease in electrical resistance by ∼50 %. Thus, the modulatory role of FAK on endothelial barrier function is dependent on actin polymerization. FAK translocation to focal adhesion complex in endothelial cells guided by actin cables and the consequent activation of FAK-associated proteins serve to reverse the decrease in endothelial barrier function caused by inflammatory mediators such as thrombin.

The endothelium consisting of the monolayer of endothelial cells and the underlying extracellular matrix (ECM) constitutes the barrier for the transcapillary exchange of liquid and solutes (Albelda, 1991; Lum & Malik, 1994, 1996). Integrin receptors co-localized with the focal adhesion complex mediate interactions of the endothelial cell with ECM, and thus contribute to endothelial barrier integrity (Burridge et al. 1988; Lampugnani et al. 1991; Qiao et al. 1995; Gao et al. 2000). Ligation of the endothelial cell surface Protease Activated Receptor-1 (PAR-1) with thrombin induces minute intercellular gaps which are responsible for the observed increase in vascular permeability (Garcia et al. 1993; Lum et al. 1993; Gerszten et al. 1994). The formation of these gaps and loss of endothelial barrier function occurs as a result of a cell shape change secondary to actin-myosin-driven contractile force (Lum & Malik, 1994, 1996; Garcia et al. 1995; Moy et al. 1996). At the same time there is a countervailing adhesive force generated at the focal adhesion complex and cell junctions (Ingber, 1993; Wang et al. 1993; Ingber, 1997) that may maintain cell shape and serve to prevent the increase in endothelial permeability. This complex interplay between the contractile and adhesive forces suggests that the adhesive force mediated by integrin-ECM attachments must be regulated in response to engagement of the contractile force. However, the relationship between these two opposing forces and how they contribute to the mechanism of increased endothelial permeability remain unclear.

Actin cables transmit the contractile force from inside the cell to the ECM at the focal adhesion sites (Burridge et al. 1988; Wang et al. 1993). These sites are the critical nexus points for the connection of actin filaments to the cytoplasmic domain of integrins via the cytoskeletal proteins, vinculin, talin and α-actinin; thus, these focal points serve to transmit tension from the actin cytoskeleton to ECM (Burridge et al. 1988; Burridge & Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, 1996). Focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase, is activated by integrin clustering (Richardson & Parsons, 1995; Frisch et al. 1996; Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999; Schaller, 2001). FAK appears to be key for not only the formation of focal adhesion sites but also the turnover of these sites (Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999).

Studies show that stimulation of endothelial cells with permeability-increasing mediators such as thrombin, hydrogen peroxide and vascular endothelial growth factor induces activation of FAK and focal adhesion formation (Abedi & Zachary, 1997; Schaphorst et al. 1997; Vepa et al. 1999; Carbajal et al. 2000). FAK activation depends on the state of actin filament organization since cytochalasin, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, prevented the activation (Abedi & Zachary, 1997; Vepa et al. 1999). Inhibition of actin polymerization also prevented the thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability (Phillips et al. 1989; Moy et al. 1996). These data suggest that the increase in endothelial permeability that is the result of actin polymerization occurs in association with FAK activation. Despite studies implicating FAK in the mechanism of transendothelial permeability, its precise role remains unclear. In the present study, we used the FAK antisense oligonucleotide to inhibit FAK expression (Tang & Gunst, 2001) and latrunculin-A (Lat-A), an agent that prevents actin filament (F) polymerization by binding to globular (G)-actin monomers (Coue et al. 1987; Morton et al. 2000), to address the role of FAK in the mechanism of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability.

METHODS

Materials

Human α-thrombin was obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN, USA). Human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (HPAEC) and endothelial growth medium (EBM-2) were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, CA, USA). Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS), l-glutamine, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and trypsin were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). Electrodes for endothelial monolayer electrical resistance measurements were purchased from Applied Biophysics (Troy, NY, USA). Fura 2-AM, latrunculin-A, Alexa-conjugated phalloidin, and Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Anti-focal adhesion kinase (clone No. 77) and paxillin (clone No. 349) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were obtained from BD Transduction Laboratory (Lexington, KY, USA) and anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (PY20) was obtained from ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Costa Mesa, CA, USA).

Endothelial cell culture

HPAEC were cultured in T-75 flasks coated with 0.1 % gelatin in EBM-2 medium supplemented with 10 % FBS. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 and 95 % air until confluent. Cells from each primary flasks were detached with 0.05 % trypsin-0.02 % EDTA and resuspended in fresh culture medium and passaged to 35 mm dishes containing 12 mm coverslips for imaging, or to 8-well electrodes for electrical resistance measurement, or to 60–100 mm dishes for immunoprecipitation of FAK and paxillin and for measurement of protein phosphorylation. All experiments were made in a confluent monolayer of endothelial cells. Confluence of the monolayer was assessed by contact inhibition of the cells forming the monolayer, VE-cadherin staining and formation of adherens junctions, and achievement within 3 day of a stable electrical resistance value on an electrode following seeding of the cells. A HPAEC monolayer was washed twice with serum-free medium and incubated in 1 % serum supplemented medium for 2 h before treatment with latrunculin or thrombin challenge. Latrunculin-A (Lat-A) was used as it specifically prevents actin filament (F) polymerization by binding to the globular (G)-actin monomers (Coue et al. 1987; Morton et al. 2000). In all experiments, we used endothelial cells between passages 4 and 8.

Quantification of filamentous (F) actin

F-actin polymerization was determined as described by Cano et al. (1991). Confluent monolayers of HPAEC (150 000 cells) grown in gelatin-coated 35 mm dishes were pretreated with 0–100 nm latrunculin for 15 min, after which they were stimulated with 50 nm thrombin. After 0–5 min, dishes were placed on ice and cells were lysed in PHEM buffer (containing (mm): 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 60 Pipes, 25 Hepes, 0.5 % Triton X-100, and 10 μm DNAase) followed by addition of 0.6 μl of tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (TRITC)-phalloidin (final concentration; 0.6 μm). Extracts were incubated in the dark at 0 °C for 1 h, and then each sample was centrifuged at 35 000 g in a Beckman centrifuge. The cell pellet was washed with cold PHEM buffer, and the F-actin bound rhodamine complex was extracted by adding methanol to the cell pellet. TRITC fluorescence in the methanol was read using 540 nm excitation and 560 nm emission in a Photon Laboratory International Spectrofluorometer. Polymerized F-actin was calculated from the percentage increase in fluorescence over that obtained in unstimulated cells.

Transfection of HPAEC with oligonucleotides

The phosphorothioate oligonucleotides to FAK, in the sense (5′-CAATGCCATCAACCAGAG-3′) and antisense configurations (5′-CTCTGGTTGATGGGATTG-3′) have been described; each is targeted to the 3′-untranslated region of FAK mRNA (Tang & Gunst, 2001). HPAEC were grown on 60 mm dishes or 8-well gold electrodes to 80 % confluence. Lipofectin (Life Technologies, Inc.) was prepared in 0.2 ml Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, Inc.) containing 5 μg of Lipofectin per micromole of oligonucleotide and equilibrated for 45 min. Either antisense or sense oligonucleotide was prepared at 2.5 μm in 0.2 ml of Opti-MEM and equilibrated for 1 min. The Lipofectin and oligonucleotides were then mixed gently and incubated at room temperature for 15 min before being diluted to a final volume of 2 ml with Opti-MEM to give the final concentration of 250 nm. The cells were washed with sterile PBS and treated with an Opti-MEM-lipofectin-oligonucleotide mixture for 8 h before being returned to EBM medium with 20 % fetal bovine serum. Cells were harvested 36 h after transfection.

Assessment of endothelial cell retraction

The time course of endothelial cell retraction (a measure of endothelial barrier function) in response to thrombin was measured according to previously described procedures (Tiruppathi et al. 1992). HPAEC (200 000 cells) seeded on gelatin-coated small gold electrodes (4.9 × 10−4 cm2) were allowed to grow till they achieve a stable electrical resistance value (a marker of a confluent monolayer). Cells were pretreated with latrunculin or oligonucleotides, and the thrombin-induced change in electrical resistance of the endothelial monolayer was measured. The small electrode and larger counter electrode were connected to a phase-sensitive lock-in amplifier. A constant current of 1 mA was supplied by a 1-V, 4000-Hz alternating current connected serially to 1 MΩ resistor between the small electrode and the larger counter electrode. The voltage between the small and large electrodes was monitored by a lock-in amplifier, stored and processed on a computer. Data were calculated as the average basal electrical resistance (in units of Ω cm2) as well as changes in the resistive (in phase) portion of impedance normalized to its initial value at time 0.

Intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) measurement

The change in [Ca2+]i was measured using the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye fura 2-AM (Ellis et al. 1999). Cells grown to confluence on gelatin-coated 22 mm glass coverslips were washed twice with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) and then incubated with 5 mm fura 2-AM for 45 min at 37 °C. Latrunculin was added to these cells after 25 min incubation in HBSS containing fura 2-AM, and the cells were incubated for another 15 min. After loading, the cells were washed twice with HBSS. The cells were imaged using an Attoflor Ratio Vision digital Fluorescence microscopy system (Atto Instruments, Rockville, MD, USA) equipped with a Zeiss Axiovert S100 inverted microscope and a F-Fluar × 40, 1.3 NA oil immersion objective lens. Regions of interest in individual cells were marked and excited at 334 and 380 nm with emission at 520 nm. The increase in 334 nm/380 nm excitation ratio as a function of [Ca2+]i was captured at 5 s intervals. At the end of each experiment, 5 μm ionomycin was added to obtain fluorescence from free fura-2 (low [Ca 2+]i). [Ca 2+]i was calculated based on a Kd value of 225 nm with a two point fit curve.

Myosin light chain phosphorylation

Phosphorylation of myosin light chain was measured in HPAEC by urea PAGE as previously described (Garcia et al. 1995). HPAEC monolayers grown on 100 mm dishes were pretreated with 0–100 nm latrunculin for 15 min after which cells were stimulated with 50 nm thrombin. After 2 min, the reaction was stopped by addition of ice-cold 10 % trichloroacetic acid containing 10 mm dithiothreitol solution. Endothelial cells were scraped from the dish after which they were centrifuged. Cell pellets were washed 4 times with diethyl ether and suspended in 6.7 m urea sample buffer to extract myosin light chains (MLCs). MLCs were separated by glycerol-urea-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated MLCs were detected by incubating the membrane with polyclonal rabbit anti-MLC20 antibody followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham) for visualization of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated bands of MLCs by chemiluminescence.

Immunofluorescence

HPAEC grown to confluence on gelatin-coated glass cover slips were pretreated for 15 min with or without 100 nm latrunculin at 37 °C. The cells were then stimulated with 50 nm thrombin. After 0–60 min of thrombin stimulation, the cells were fixed for 15 min with 2 % paraformaldehyde in HBSS containing 10 mm Hepes buffer (pH 7.3) at room temperature. The cells were thoroughly rinsed twice with HBSS and then permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton X-100 for 3 min. After rinsing, cells were again rinsed 3 times, and were then incubated with 5 % goat serum in HBSS followed by incubation with 2 μg ml−1 of FAK antibody. After 1 h, the cells were rinsed 3 times in HBSS followed by incubation with the fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody (1 μg ml−1 Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG) for an additional 45 min. Cells were then incubated with 1 U ml−1 of Alexa-568-conjugated phalloidin for 30 min followed by incubation with DAPI for 20 min to stain nuclei. Cells were then washed 3 times with HBSS, mounted with Prolong Antifade mounting medium and viewed with a × 60 objective lens in a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope using appropriate filters.

Phosphorylation and immunoprecipitation of FAK and paxillin

Cells grown to confluence in 60 mm dishes were treated with 0–100 nm latrunculin for 15 min. After 0–2 min of thrombin stimulation, the reaction was terminated by transferring dishes to ice. The cells were then quickly rinsed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and lysed for 20 min on ice with 300 μl of lysis buffer. Lysis buffer contained 10 mm Tris, 150 mmNaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0.5 % Nonidet P-40, 1 % Triton-X, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF) and 1 μg ml−1 each of leupeptin, pepstatin A, and aprotinin. The lysate was scraped and centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10 min and protein was determined in an aliquot of supernatant using the Pierce kit. Cell lysates normalized to equal amounts of protein were precleared for 30 min with 50 μl of a 10 % suspension of protein-A-sepharose beads. The samples were then centrifuged and incubated overnight with anti-mouse monoclonal FAK antibody or paxillin antibody, and for an additional 2 h with 100 μl of a 10 % suspension of protein A-sepharose beads coupled to anti-mouse IgG. Beads from each sample were collected by centrifugation and washed 4 times with ice-cold lysate buffer. Paxillin or FAK was eluted from the beads by boiling the samples for 5 min in sample buffer. Immunoprecipitates of FAK and paxillin were electrophoresed on 10 % SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 2 % gelatin, and probed with antibody to phosphotyrosine (PY-20) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) for visualization by chemiluminescence. The nitrocellulose membrane was then stripped of bound antibodies and re-probed with a monoclonal antibody against paxillin or FAK to confirm the location of FAK or paxillin and to normalize for minor differences in protein loading. Tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin were visualized by chemiluminescence and quantified by scanning densitometry.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between experimental groups were made by ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance using SigmaStat software. Differences in mean values were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Latrunculin-A prevents thrombin-induced F-actin polymerization in endothelial cells

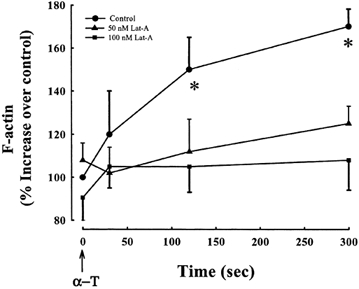

Figure 1 shows the time course of F-actin polymerization in response to thrombin in cells treated for 15 min with different latrunculin concentrations. Polymerized F-actin was quantified by measuring the fluorescence of the bound phalloidin. Thrombin induced the polymerization of F-actin within 30 s and the values reached a plateau within 2 min. F-actin polymerization was markedly reduced in cells treated with latrunculin with the reduction being greater at higher latrunculin concentrations (100 nm). In unstimulated cells, basal F-actin content was not different between control and latrunculin-pretreated cells.

Figure 1. Effects of latrunculin on F-actin polymerization in endothelial cells stimulated with thrombin.

Fluorescence of bound phalloidin was measured to quantitate F-actin in HPAEC treated without or with latrunculin. In untreated cells,actin polymerized within 30s and reached a plateau within 2 min after thrombin stimulation (50 nM).Latrunculin markedly reduced F-actin polymerization in response to thrombin. Differences in F-actin were significant in untreated cells as compared to cells treated with latrunculin. F-actin in HPAE cell monolayer was calculated as the percentage increase in F-actin over that in the unstimulated monolayer. Values are means ± S.E.M.(n = 3). *Values different from untreated monolayer (P < 0.05). α-T, α-thrombin;Lat-A, latrunculin A.

Inhibition of actin polymerization prevents thrombin-induced endothelial cell retraction

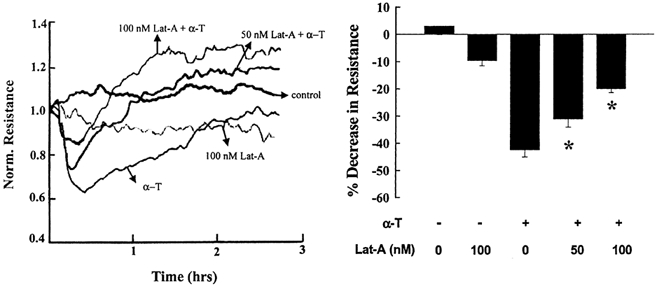

Addition of thrombin significantly decreased transendothelial electrical resistance by 40–50 % from a mean basal value of (414 ± 33) × 10−2 Ω cm2 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Latrunculin treatment prevented in a concentration-dependent manner, the decrease in electrical resistance in response to thrombin (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Effects of inhibition of actin polymerization on time course of thrombin-induced endothelial retraction.

HPAEC grown to confluence on gold electrodes were pretreated without or with latrunculin after which they were stimulated with 50 nm thrombin to measure the time course of transendothelial electrical resistance. Latrunculin prevented the thrombin-induced decrease in electrical resistance. A, real time data from a single experiment. B, data from multiple experiments presented as means ± s.e.m. of the maximum decrease in electrical resistance (n = 9). * Values different from untreated monolayer (P < 0.05). α-T, α-thrombin; Lat-A, latrunculin A.

Table 1.

Effects of thrombin on HPAEC monolayer resistance values

| Condition | HPAEC resistance (Ωcm2) × 10−2 |

|---|---|

| Control | 414 ± 33 |

| Lat-A (100 nm) | 374 ± 26 |

| Thrombin (50 nm) | 240 ± 11 |

| Lat-A (50 nm) + thrombin (50 nm) | 293 ± 21* |

| Lat-A (100 nm) + thrombin (50 nm) | 334 ± 21* |

HPAEC monolayer electrical resistance was measured as described in Methods; values (shown as means ± s.e.m.) are the maximum decreases in resistance in the different groups. Results are from 9 experiments made in duplicate.

Different from thrombin (P < 0.05).

Inhibition of actin polymerization fails to prevent thrombin-activated Ca2+signalling and MLC phosphorylation

We determined the effects of latrunculin on the thrombin-induced increase in [Ca2+]i and MLC phosphorylation to evaluate whether inhibition of cell retraction was secondary to disruption of Ca2+ signalling and MLC phosphorylation. Fura 2-AM-loaded HPAEC were pretreated for 15 min with latrunculin, and the cells were then challenged with thrombin. Figure 3A shows similar Ca2+ transients in response to thrombin in both latrunculin-treated and control cells. MLC phosphorylation was assessed by separating the non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated MLCs by glycerol-urea-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-MLC20 antibody. Latrunculin had no effect on thrombin-induced MLC phosphorylation as a similar response was seen as in the control cell (Fig. 3B). Thus, inhibition of thrombin-induced cell retraction by latrunculin was not secondary to interference in Ca2+ signalling or MLC phosphorylation.

Figure 3. Effects of inhibition of actin polymerization on thrombin-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ and MLC phosphorylation.

A, effects of inhibition of actin polymerization on thrombin-induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ in endothelial cells. HPAEC grown to confluence on glass coverslips were loaded with fura 2-AM followed by treatment without or with latrunculin. Cells were stimulated with thrombin to measure increases in cytosolic Ca2+concentration ([Ca2+]i). Similar rises in [Ca2+]i were obtained in latrunculin-treated cells as in untreated cells. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times. As results from the experiments were similar, data from a representative experiment are shown. B, effects of inhibition of actin polymerization on thrombin-induced MLC phosphorylation in endothelial cells. HPAEC treated without or with latrunculin were stimulated with 50 nm thrombin for 2 min and assessed for phosphorylated MLC by urea gel electrophoresis. HPAEC have both non-muscle and smooth muscle isoforms (5 MLC isoforms). MLC phosphorylation was similar in untreated cells and cells treated with latrunculin. Experiments were repeated 3 times. Data are from a representative experiment. α-T, α-thrombin; Lat-A, latrunculin; -, absence; +, presence; non-P, non phosphorylated; mono P, monophosphorylated; Di-P, diphosphorylated.

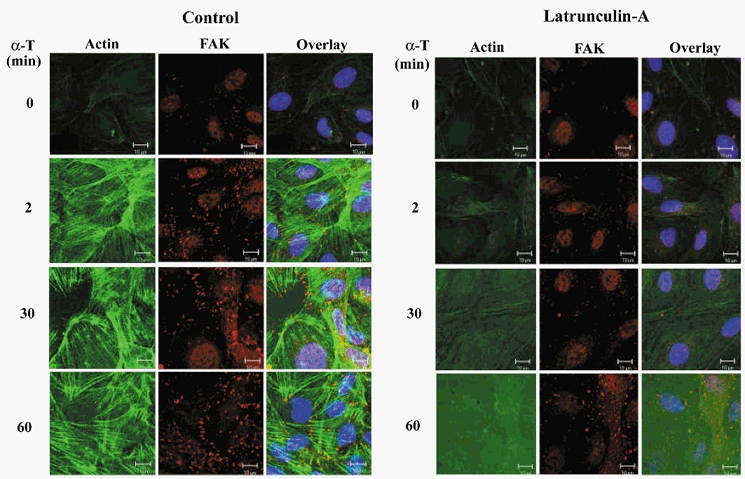

Inhibition of actin polymerization prevents FAK translocation to the focal adhesion complex and FAK activation

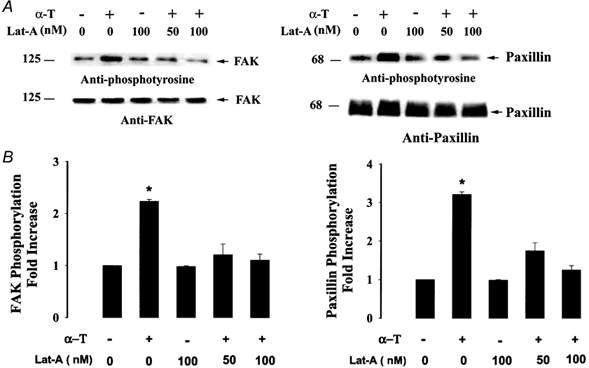

We determined the relationship between actin polymerization and FAK activation to address how cell retraction induced by actin polymerization contributed to the loss of endothelial barrier function. Latrunculin-pretreated or control cells were fixed at 0, 2, 30, or 60 min after thrombin stimulation. FAK was co-localized with F-actin by staining with anti-FAK antibody followed by fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody to label FAK and fluorescent-tagged phalloidin to label the actin stress fibres. In unstimulated cells, FAK was diffusely localized within the cytoplasm with actin stress fibres (which were less prominent in these control, unstimulated cells). Thrombin induced the formation of actin stress fibres and the translocation of FAK to focal adhesion sites within 2 min of stimulation. FAK staining preferentially co-localized with the ends of actin stress fibres. A pattern of significant FAK and actin stress fibre co-localization was apparent up to 60 min after thrombin stimulation. FAK translocation to focal adhesion sites was not seen in the absence of actin polymerization (Fig. 4). As FAK recruitment to focal adhesion sites may activate effector proteins such as paxillin as well as FAK itself, we determined the effects of inhibition of actin polymerization on tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin. FAK and paxillin were immunoprecipitated and tyrosine phosphorylation was assessed using phosphotyrosine antibody. In untreated cells, thrombin induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin, whereas neither protein was phosphorylated in the absence of actin polymerization (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Inhibition of actin polymerization in endothelial cells prevents thrombin-induced translocation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) to focal adhesion sites and association with actin stress fibres.

HPAEC treated without or with 100 nm latrunculin were stimulated for up to 60 min with 50 nm thrombin, fixed, and triple stained for actin stress fibres (green), FAK (red), and nuclei (blue). Thrombin induced actin stress fibre formation and FAK translocation to focal adhesion sites within 2 min of stimulation. FAK staining was co-localized with the ends of actin stress fibres (overlay, yellow). This distinct pattern of co-localization of FAK with actin stress fibres was apparent up to 60 min after thrombin stimulation. In the absence of actin polymerization, thrombin failed to induce translocation of FAK to focal adhesion sites. This experiment was repeated at least 3 times; results are from representative experiments. α-T, α-thrombin; FAK, focal adhesion kinase. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Figure 5. Inhibition of actin polymerization prevents thrombin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin was determined in HPAEC after stimulation with thrombin in cells treated with 50 or 100 nm latrunculin. Blots of FAK and paxillin immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, stripped, and reprobed with anti-FAK or anti-paxillin antibody. In untreated cells, thrombin induced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin. In the absence of actin polymerization, thrombin failed to activate FAK and paxillin phosphorylation. A, Western blot of immunoprecipitates of FAK and paxillin. B, data from multiple experiments shown as means ± s.e.m. of the increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin (n = 3) in response to thrombin, quantified as the increase relative to phosphorylation in unstimulated cells. * Values different from unstimulated cells (P < 0.05). α-T, α-thrombin; Lat-A, latrunculin A; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; -, absence; +, presence.

Reduction in FAK expression augments the decrease in endothelial barrier function

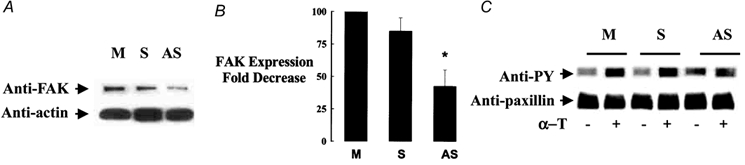

Since the inhibition of actin polymerization prevented the thrombin-induced FAK activation and endothelial retraction, we addressed the effects of reduced FAK expression on endothelial barrier function. We used FAK antisense oligonucleotide to address the effects of reduced FAK expression (Tang & Gunst, 2001) on these responses. FAK expression was analysed by Western blotting following transfection of the sense and antisense phosphothioronate oligonucleotides in HPAEC. Antisense concentration of 0.25 μm was found to be optimal for inhibiting FAK expression by ∼60 %, whereas a similar concentration of sense oligonucleotide had no significant effect on FAK expression (Fig. 6A and B). FAK antisense oligonucleotide also had no effect on actin expression (Fig. 6A). In the presence of reduced FAK expression, we observed that thrombin failed to activate tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Decreased FAK expression by antisense oligonucleotide decreases thrombin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin was determined in HPAEC after 2 min thrombin stimulation following transfection without or with 0.25μm of FAK sense or antisense oligonucleotide. Proteins from cell lysates were probed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, stripped, and re-probed with anti-paxillin antibody. In mock or sense-transfected cells, thrombin induced tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin. In FAK antisense-treated cells, thrombin failed to activate paxillin phosphorylation. A,Western blot of FAK or actin in cell lysate following transfection with FAK sense or antisense oligonucleotide. B, data from multiple experiments are shown as means ± s.e.m. of fold decrease in FAK expression. FAK expression was quantitated as decrease relative to protein levels in control cells. C, Western blot of cell lysate using phosphotyrosine and paxillin antibodies following transfection of cells with FAK sense or antisense oligonucleotide. * Values different from mock- or sense-transfected monolayer (P < 0.05). α-T, α-thrombin; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; -, absence; +, presence; PY, phosphotyrosine; M, mock-transfected; S, sense; AS, antisense.

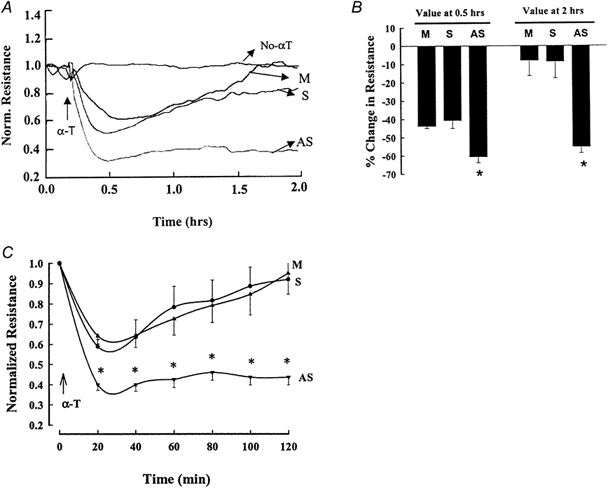

Stimulation of endothelial cells with thrombin induces rapid retraction of endothelial cells followed by recovery of barrier function within 2 h, as shown above. As FAK is an integral component of integrin signalling, we addressed the possibility that FAK might modulate endothelial barrier function; thus, we determined the effects of reduced FAK expression on transendothelial electrical resistance. Confluent HPAEC were transfected with FAK antisense or sense using Lipofectin as described in Methods. The 36 h transfection period (prior to thrombin challenge) resulted in small decreases in electrical resistance that were similar in all groups. Without oligonucleotide, electrical resistance decreased by 12 ± 0.3 % from the pretransfection basal value. Electrical resistance with FAK sense or antisense oligonucleotide decreased by 14 ± 0.4 % or 16 ± 0.3 %, respectively, of pretransfection resistance values. In the endothelial cells challenged with thrombin, we showed that the reduction in FAK expression resulted in not only a greater decrease in transendothelial resistance in response to thrombin but also a longer lasting decrease in resistance (Fig. 7A-C and Table 2).

Figure 7. Effect of reduction in FAK expression on thrombin-induced endothelial cell retraction.

HPAEC grown to confluence on gold electrodes were transfected with Lipofectamin alone or with 0.25μm of FAK sense or antisense oligonucleotide. Cells were stimulated with 50 nm thrombin to measure the time course of changes in transendothelial electrical resistance. The reduction in FAK expression prolonged and augmented the thrombin-induced decrease in electrical resistance. A, real time data from a single experiment. B, data from multiple experiments presented as means ± s.e.m. of resistance values at 0.5 and 2 h (n = 9). C, time course of transendothelial electrical resistance changes from multiple experiments presented as means ± s.e.m. (n = 9–12). * Values different from mock- or sense-transfected monolayer (P < 0.05). α-T, α-thrombin; M, mock transfected; S, sense; AS, antisense.

Table 2.

Effects of FAK antisense on HPAEC monolayer resistance values in response to thrombin stimulation

| HPAEC resistance(Ωcm2) × 10−2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Basal | 0.5 h | 2 h |

| Mock | 294 ± 12 | 165 ± 21 | 268 ± 26 |

| FAK Sense | 279± 34 | 167 ± 18 | 255 ± 30 |

| FAK Antisense | 252 ± 23 | 100 ± 16* | 112 ± 19* |

HPAEC monolayer electrical resistance was measured as described in Methods; values (shown as means ± s.e.m.) shown are the maximum decreases in resistance in the three groups. Results are from 3 experiments made in triplicate.

Different from mock or sense transfected cells (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show using the antisense approach that a reduction in FAK expression both augmented and prolonged the thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability. The results indicate that FAK modulates in a negative feedback manner the decrease in endothelial barrier function. Moreover, actin polymerization is required for FAK translocation to the endothelial focal adhesion complex, suggesting that the formation of actin cables by thrombin induces FAK translocation and its activation so as to reverse the increase in endothelial permeability.

We studied the response to thrombin because it produces a well-characterized increase in endothelial permeability. The cells retract within minutes (indicative of a rapid increase in paracellular permeability) and this is followed by a recovery phase within 2 h during which the barrier function is restored (Tiruppathi et al. 1992; Moy et al. 1996; Schaphorst et al. 1997). Retraction of endothelial cells depends on their ability to produce an actin-myosin-generated contractile force that induces the cell shape change (Wysolmerski & Lagunoff, 1990; Lum & Malik, 1994, 1996; Garcia et al. 1995; Moy et al. 1996). Integrin receptors localized in the focal adhesion complex are crucial in mediating endothelial cell-ECM interactions (Burridge et al. 1988). Thus, any alterations in integrin function can modify the cell attachments to the ECM and result in cell shape change, and thereby influence endothelial barrier function. The focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a constituent of focal adhesions, is activated by integrins (Richardson & Parsons, 1995; Frisch et al. 1996; Gilmore & Burridge, 1996; Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999; Schaller, 2001), and in turn FAK can also influence the interaction of integrins with ECM. Upon activation, FAK is targeted to the focal adhesion complex, where it induces phosphorylation of the focal adhesion complex-linked cytoskeletal proteins such as paxillin (Richardson & Parsons, 1995; Frisch et al. 1996; Gilmore & Burridge, 1996; Schaller et al. 1999; Schaller, 2001). The present study focuses on FAK because its phosphorylation and recruitment to focal contacts may be a key event regulating interaction of the integrins with ECM (Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999).

Studies show that stimulation of endothelial cells with permeability-increasing mediators as diverse as thrombin, hydrogen peroxide and vascular endothelial growth factor induces cell retraction, which occurs in association with actin polymerization, actin stress fibre formation, activation of FAK, and focal adhesion formation (Abedi & Zachary, 1997; Schaphorst et al. 1997; Vepa et al. 1999). Since inhibition of actin polymerization blocks FAK function as well as the increase in endothelial permeability (Abedi & Zachary, 1997; Vepa et al. 1999), we surmised that the increased endothelial permeability dependent on actin polymerization may be regulated by FAK activation. We therefore determined the role of FAK in the mechanism of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability. We used either FAK antisense oligonucleotide to block FAK expression (Tang & Gunst, 2001) or latrunculin to inhibit actin polymerization and thus prevent the actin-dependent FAK activation (Coue et al. 1987; Morton et al. 2000). The results show that actin is polymerized in endothelial cells within 30 s after thrombin stimulation and polymerization stabilizes within 2 min, in parallel with the time course of the increase in endothelial permeability (Lum et al. 1992; Thurston & Turner, 1994; Goeckeler & Wysolmerski, 1995). The results also show that latrunculin prevents the thrombin-induced actin polymerization as well as the increase in endothelial permeability. As inhibition of actin polymerization may interfere with Ca2+ signalling or MLC phosphorylation (Bourguignon et al. 1993; Holda & Blatter, 1997; Ribeiro et al. 1997), we measured both [Ca2+]i and MLC phosphorylation to rule out the possibility that the effects of latrunculin could not be ascribed to these events. Since latrunculin had no effect on thrombin-induced [Ca2+]i or MLC phosphorylation, it is likely that latrunculin has a direct effect in inhibiting actin polymerization.

We observed that FAK was translocated to the ends of actin stress fibres in thrombin-stimulated endothelial cells, whereas this failed to occur in the absence of actin polymerization in latrunculin-treated cells. In the absence of actin polymerization, thrombin also failed to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK and paxillin. Thus, actin filament polymerization is required for FAK mobilization to the focal adhesion complex and for FAK activation in endothelial cells. The finding that thrombin induced the translocation of FAK to adhesion sites with the ECM is temporally consistent with formation of focal adhesions occurring in parallel with the loss of endothelial barrier function (Lum & Malik, 1996; Moy et al. 1996; Schaphorst et al. 1997; Carbajal et al. 2000). To address the effects of FAK in the response, we used the antisense approach to reduce FAK expression in endothelial cells. We addressed the possibility that thrombin-induced activation of FAK and the formation of focal adhesion contribute to the increase in endothelial permeability dependent on actin polymerization. Reduction in FAK expression resulted in decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin, indicating that FAK is an integral component of the signalling pathway leading to paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Richardson & Parsons, 1995; Frisch et al. 1996; Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999; Schaller, 2001). Importantly, the reduced FAK expression produced a greater and prolonged decrease in transendothelial resistance in response to thrombin. These results indicate that activation of FAK is not the basis of the actin polymerization-dependent increase in endothelial permeability, but rather is critically involved in restoring the barrier function when junctional permeability is increased by the actin-myosin contractile machinery of endothelial cells.

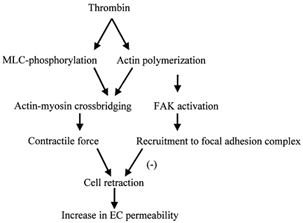

In conclusion, we propose a novel role of FAK in the negative feedback regulation of endothelial permeability. In this model (Fig. 8), FAK translocation to the focal adhesion complex induced by actin polymerization opposes the formation of inter-endothelial gaps and attenuates the increase in transendothelial permeability. This model helps to explain the reversible nature of the increase in endothelial permeability in response to inflammatory mediators and the persistent nature of hyper-permeability associated with chronic inflammatory states.

Figure 8. Proposed model of the role of FAK in regulating endothelial barrier dysfunction.

Thrombin induces actin polymerization and MLC phosphorylation that leads to generation of contractile force through actin-myosin cross-bridging. The generated contractile force results in cell retraction by altering cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions. Actin polymerization activates FAK that in turns serves in a negative feedback manner to reverse the increase in endothelial permeability by inhibiting cell retraction. MLC, myosin light chain; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; EC, endothelial cell.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants HL27016, HL46350, and HL45638.

REFERENCES

- Abedi H, Zachary I. Vascular endothelial growth factor stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and recruitment to new focal adhesions of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:15442–15451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albelda SM. Endothelial and epithelial cell adhesion molecules. American Journal of Respiratory and Cell Molecular Biology. 1991;4:195–203. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon LY, Iida N, Jin H. The involvement of the cytoskeleton in regulating IP3 receptor-mediated internal Ca2+ release in human blood platelets. Cell Biology International. 1993;17:751–758. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1993.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 1996;12:463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Fath K, Kelly T, Nuckolls G, Turner C. Focal adhesions: transmembrane junctions between the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. Annual Review of Cell Biology. 1988;4:487–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano ML, Lauffenburger DA, Zigmond SH. Kinetic analysis of F-actin depolymerization in polymorphonuclear leukocyte lysates indicates that chemoattractant stimulation increases actin filament number without altering the filament length distribution. Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;115:677–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal JM, Gratrix ML, Yu CH, Schaeffer RCJr. ROCK mediates thrombin's endothelial barrier dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2000;279:C195–204. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.1.C195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coue M, Brenner SL, Spector I, Korn ED. Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Letters. 1987;213:316–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CA, Tiruppathi C, Sandoval R, Niles WD, Malik AB. Time course of recovery of endothelial cell surface thrombin receptor (PAR-1) expression. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:C38–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui PY. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Curtis TM, Blumenstock FA, Minnear FL, Saba TM. Increased recycling of (alpha)5(beta)1 integrins by lung endothelial cells in response to tumor necrosis factor. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113:247–257. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1995;163:510–522. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JG, Patterson C, Bahler C, Aschner J, Hart CM, English D. Thrombin receptor activating peptides induce Ca2+ mobilization, barrier dysfunction, prostaglandin synthesis, and platelet-derived growth factor mRNA expression in cultured endothelium. Journal of Cell Physiology. 1993;156:541–549. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041560313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerszten RE, Chen J, Ishii M, Ishii K, Wang L, Nanevicz T, Turck CW, Vu TK, Coughlin SR. Specificity of the thrombin receptor for agonist peptide is defined by its extracellular surface. Nature. 1994;368:648–651. doi: 10.1038/368648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AP, Burridge K. Molecular mechanisms for focal adhesion assembly through regulation of protein-protein interactions. Structure. 1996;4:647–651. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeckler ZM, Wysolmerski RM. Myosin light chain kinase-regulated endothelial cell contraction: the relationship between isometric tension, actin polymerization, and myosin phosphorylation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;130:613–627. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holda JR, Blatter LA. Capacitative calcium entry is inhibited in vascular endothelial cells by disruption of cytoskeletal microfilaments. FEBS Letters. 1997;403:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AR, Parsons JT. Cell migration-movin’ on. Science. 1999;286:1102–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Cellular tensegrity: defining new rules of biological design that govern the cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Science. 1993;104:613–627. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampugnani MG, Resnati M, Dejana E, Marchisio PC. The role of integrins in the maintenance of endothelial monolayer integrity. Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;112:479–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H, Andersen TT, Siflinger-Birnboim A, Tiruppathi C, Goligorsky MS, Fenton JW, Malik AB. Thrombin receptor peptide inhibits thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability by receptor desensitization. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120:1491–1499. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H, Aschner JL, Phillips PG, Fletcher PW, Malik AB. Time course of thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability: relationship to Ca2+i and inositol polyphosphates [published erratum appears in American Journal of Physiology 263: section L following table of contents] American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:L219–225. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.2.L219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H, Malik AB. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:L223–2241. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.3.L223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H, Malik AB. Mechanisms of increased endothelial permeability. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1996;74:787–800. doi: 10.1139/y96-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton WM, Ayscough KR, McLaughlin PJ. Latrunculin alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent polymerization. Nature Cell Biology. 2000;2:376–378. doi: 10.1038/35014075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy AB, Van Engelenhoven J, Bodmer J, Kamath J, Keese C, Giaever I, Shasby S, Shasby DM. Histamine and thrombin modulate endothelial focal adhesion through centripetal and centrifugal forces. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97:1020–1027. doi: 10.1172/JCI118493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PG, Lum H, Malik AB, Tsan MF. Phallacidin prevents thrombin-induced increases in endothelial permeability to albumin. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;257:C562–567. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.3.C562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao RL, Yan W, Lum H, Malik AB. Arg-Gly-Asp peptide increases endothelial hydraulic conductivity: comparison with thrombin response. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C110–117. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.1.C110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro CM, Reece J, Putney JWJr. Role of the cytoskeleton in calcium signaling in NIH 3T3 cells. An intact cytoskeleton is required for agonist-induced [Ca2+]i signaling, but not for capacitative calcium entry. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:26555–26561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Parsons JT. Signal transduction through integrins: a central role for focal adhesion kinase. Bioessays. 1995;17:229–236. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller MD, Hildebrand JD, Parsons JT. Complex formation with focal adhesion kinase: A mechanism to regulate activity and subcellular localization of Src kinases. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1999;10:3489–3505. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaphorst KL, Pavalko FM, Patterson CE, Garcia JG. Thrombin-mediated focal adhesion plaque reorganization in endothelium: role of protein phosphorylation. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1997;17:443–455. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.4.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang DD, Gunst SJ. Depletion of focal adhesion kinase by antisense depresses contractile activation of smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2001;280:C874–883. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston G, Turner D. Thrombin-induced increase of F-actin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Microvascular Research. 1994;47:1–20. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Del Vecchio PJ, Keese CR, Giaever I. Electrical method for detection of endothelial cell shape change in real time: assessment of endothelial barrier function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:7919–7923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vepa S, Scribner WM, Parinandi NL, English D, Garcia JG, Natarajan V. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in vascular endothelial cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:L150–158. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.1.L150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 1993;260:1124–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.7684161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Involvement of myosin light-chain kinase in endothelial cell retraction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1990;87:16–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]