Abstract

Kv4 channels are believed to underlie the rapidly recovering cardiac transient outward current (Ito) phenotype. However, heterologously expressed Kv4 channels fail to fully reconstitute the native current. Kv channel interacting proteins (KChIPs) have been shown to modulate Kv4 channel function. To determine the potential involvement of KChIPs in the rapidly recovering Ito, we cloned three KChIP2 isoforms (designated fKChIP2, 2a and 2b) from the ferret heart. Based upon immunoblot data suggesting the presence of a potential endogenous KChIP-like protein in HEK 293, CHO and COS cells but absence in Xenopus oocytes, we coexpressed Kv4.3 and the fKChIP2 isoforms in Xenopus oocytes. Functional analysis showed that while all fKChIP2 isoforms produced a fourfold acceleration of recovery kinetics compared to Kv4.3 expressed alone, only fKChIP2a produced large depolarizing shifts in the V1/2 of steady-state activation and inactivation as seen for the native rapidly recovering Ito. Analysis of RNA and protein expression of the three fKChIP2 isoforms in ferret ventricles showed that fKChIP2b was most abundant and was expressed in a gradient paralleling the rapidly recovering Ito distribution. Ferret KChIP2 and 2a were expressed at very low levels. The ventricular expression distribution suggests that fKChIP2 isoforms are involved in modulation of the rapidly recovering Ito; however, additional regulatory factors are also likely to be involved in generating the native current.

The transient outward potassium current, Ito, is a rapidly activating and inactivating current which plays important roles in phase 1 repolarization and modulation of excitation-contraction coupling in working ventricular myocytes (Antzelevitch et al. 2000). In many species, including humans, two Ito phenotypes have been described with heterogeneous expression across the ventricles. A phenotype with rapid kinetics of recovery from inactivation is prominent in left ventricular (LV) epicardial and right ventricular (RV) myocytes and a slowly recovering phenotype is prominent in LV endocardial myocytes (Campbell et al. 1993; Wettwer et al. 1994; Näbauer et al. 1996; Brahmajothi et al. 1999). At the molecular level, evidence suggests that Kv4.2/4.3 underlie the rapidly recovering Ito, while Kv1.4 is responsible for the slowly recovering phenotype (Brahmajothi et al. 1999; Oudit et al. 2001; Nerbonne, 2002). With regard to the rapidly recovering phenotype, heterologous expression of cardiac Kv4.2/4.3 α subunits alone gives rise to a current which resembles the native Ito (Yeola & Snyders, 1997; Franqueza et al. 1999). However, Kv4.2/4.3 α subunits fail to reconstitute many of the important biophysical characteristics of the native Ito phenotype, particularly with regard to the kinetics of recovery from inactivation.

Recently, numerous isoforms of Ca2+-binding proteins referred to as Kv channel interacting proteins (KChIPs) have been identified (An et al. 2000; Bähring et al. 2001). These studies demonstrated that when KChIPs are heterologously expressed with Kv4.2 or Kv4.3, there is an increase in Kv4 channel cell surface expression and the kinetics of recovery from inactivation of the expressed currents approach those of the native rapidly recovering Ito. Therefore, KChIPs may be involved in regulating the gating characteristics and current amplitude of the rapidly recovering RV and LV epicardial Ito.

We have cloned three KChIP2 isoforms from ferret heart and show that these KChIP isoforms exert distinct modulatory effects on ferret Kv4.3 α subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. We also demonstrate the presence of both RNA and protein gradients of KChIP2 isoforms paralleling the distribution of the rapidly recovering Ito across the ventricular walls. The heterogeneity of expression and differences in functional effects of the KChIP2 isoforms may provide molecular mechanisms for selectively modulating gating characteristics of Ito phenotypes expressed in various anatomical regions of the ventricles.

METHODS

Animal protocols

All animal protocols were conducted according to NIH approved guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University at Buffalo, SUNY. Male ferrets (8–20 weeks old) were anaesthetized (i.p.; sodium pentobarbital, 35 mg kg−1) and the hearts removed (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). Xenopus laevis oocytes were obtained as previously described (Comer et al. 1994). Frogs were anaesthetized by soaking in 0.75 g l−1 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester. After five surgeries, 6 weeks apart, the frogs were killed by lethal overdose of anaesthesic.

Cloning of ferret KChIP2 isoforms and ferret Kv4.3

Ferret Kv4.3 and KChIP2 isoforms were cloned using RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from ferret hearts and reverse transcribed. Kv4.3 and KChIP2 sequences were amplified by PCR with primers based on human, mouse and rat sequences available in GenBank. The fKChIP2, 2a, 2b, and fKv4.3 (long form) sequences have been assigned GenBank numbers AF454385–8, respectively.

RNase protection assays

The apex and base of the RV and LV free walls were discarded and the remaining middle one-third was used for RNA preparation. The entire free wall of the RV was used, while LV tissue samples were dissected as ∼1 mm deep strips from the epicardial and endocardial surfaces. The fKChIP probe was constructed by PCR amplifying the first 247 base pairs from the fKChIP2b clone and subcloning into pBSII-KS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The control cyclophilin probe was prepared by RT-PCR with ferret heart cDNA. The PCR primers were designed based on the sequence of mouse cyclophilin (GenBank M60456). The cyclophilin PCR products were ligated into pBluescript. The plasmids were linearized and transcribed (MaxiScript Kit, Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) in the presence of α-32P-rCTP to generate high specific activity antisense probes. RNase protection assay hybridizations and digestions were done with the RPA III Kit (Ambion). Experimental results were verified with RNA preparations from three ferret hearts.

KChIP antibodies

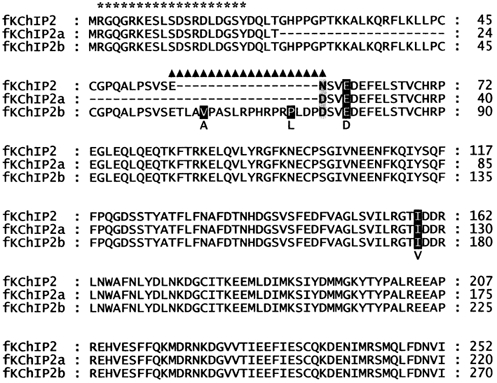

Pan-fKChIP2 and fKChIP2b antibodies were generated by Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, TX, USA) in rabbits against the synthetic peptides RGQGRKESLSDSRDLDGSY and ETLAVPASLRPHRPRPLDPD (Fig. 1). Antibodies were affinity purified against the respective peptides conjugated to Sepharose.

Figure 1. Ferret KChIP2 isoforms and RNA expression profiles.

Amino acid sequence alignment of fKChIP2 isoforms. Residues absent in fKChIP2 and 2a are indicated by a dash. An amino acid difference in the C-terminal common region is shaded grey. Differences between human and ferret KChIPs are shaded black and noted below the sequence. The peptides used for the pan-fKChIP2 and fKChIP2b antibody generation are indicated by ‘*’ and ‘▴’, respectively.

Cell transfection

Ferret KChIP2, 2a and 2b were subcloned into the pGreen Lantern-1 (Gibco BRL) transfection vector with the green fluorescent protein removed by Not I digestion. HEK 293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Gibco BRL).

Protein preparations

Tissue culture cell lines and Xenopus oocyte protein extracts were prepared by lysing cells in 1 % Igepal CA-630 (Sigma), 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate, 0.1 % SDS, 2 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonylfluoride (AEBSF), and 1 mm EDTA, incubating on ice 30–60 min, centrifuging 10 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and collecting the supernatant. Ferret heart proteins were prepared by dissecting tissue as described above and homogenizing 2 × 10 s with a polytron (Brinkman Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA), small probe, setting 5, in an ice cold solution of 10 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm iodoacetamide, 1 mm 1,10-phenanthroline, 1 mm benzamidine, 0.5 mm AEBSF, 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin and 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A (solution composition from Barry et al. 1995). The homogenate was centrifuged 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected. The pellet was resuspended, homogenized and centrifuged again. The second supernatant was collected and combined with the first. Protein concentrations were determined using the MicroBCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Immunoblots

Proteins were acetone precipitated and resuspended in sample buffer for loading onto 12 % Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gels. Protein was transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 10 % normal goat serum in TBST (20 mm Tris, 140 mmNaCl, 0.1 % Tween20, pH 7.6), rinsed with TBST, and incubated with primary antibody (1:500 dilution in TBST) for 1 h. Membranes were then washed 1 × 15 min and 3 × 5 min with TBST, incubated 1 h with a 1:50000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) diluted in TBST. Membranes were subsequently washed 1 × 15 min and 3 × 5 min with TBST and incubated in ECL-Plus Reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Chemiluminescence was detected using a FluorChem Imager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). Experimental results were verified with protein preparations from three ferret hearts.

Electrophysiology

fKv4.3, fKChIP2, 2a and 2b were subcloned into the pGEM-HE5 vector. cRNA was transcribed using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). Oocytes were injected with 23 fmol of fKv4.3 cRNA or 23 fmol of each fKv4.3 and fKChIP. Two-microelectrode voltage clamp (GeneClamp 500B, Axon Instruments; microelectrodes filled with 3 m KCl and 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.40, resistances 0.8–3.0 MΩ) was conducted 60–80 h after injection (Comer et al. 1994). Recordings (20 ± 2 °C) were conducted in ND 96 (mm: 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 Hepes, pH 7.40). Data were acquired and analysed using pCLAMP 8.0 software (Axon Instruments).

RESULTS

Cloning of ferret KChIP2 isoforms

We have cloned three KChIP2 isoforms, fKChIP2, 2a and 2b, from the ferret heart (Fig. 1). These KChIPs are identical in their C-terminal 195 amino acids but differ in the lengths of their N-termini. The longest clone, fKChIP2b, differs from a similar human clone (GenBank AAK53710) at two amino acids in the C-terminal common region and at two amino acids that are specific to the KChIP2b isoform. These three isoforms are similar to previously identified clones (An et al. 2000; Ohya et al. 2001; Bähring et al. 2001; Kuo et al. 2001). Similar to the results of others, we were unable to detect KChIP1 or KChIP3 in the heart by RT-PCR analysis (data not shown) (An et al. 2000; Rosati et al. 2001).

Identification of an optimal heterologous cell expression system

To determine the optimal heterologous cell expression system for analysis of functional differences between the fKChIP2 isoforms, we performed an immunoblot analysis for endogeneous KChIP expression in four commonly used cell types. An fKChIP2b isoform-specific antibody failed to detect protein in non-transfected HEK 293, COS, and CHO cells and uninjected Xenopus oocytes (refer to Fig. 3D). In contrast, a pan-fKChIP2 antibody which detects all fKChIP2 isoforms produced a signal of ∼21 kDa in non-transfected HEK 293, COS and CHO cells but not in Xenopus oocytes (refer to Fig. 3E). There was also an additional ∼40 kDa band in CHO cells. Based upon the possibility of an endogenous KChIP-like protein in HEK 293, COS and CHO cells interfering with our functional analysis, we used Xenopus oocytes as our expression system.

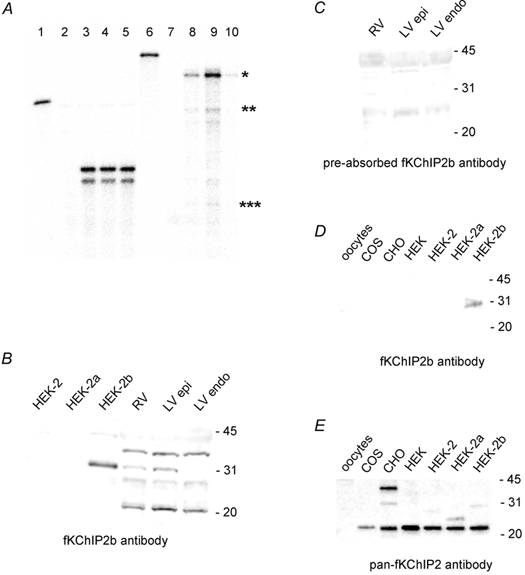

Figure 3. RNA and protein expression profile of KChIP2 isoforms.

A, RNase protection assay for fKChIP2 isoforms across ferret ventricular walls. Lane 1: full-length undigested cyclophilin probe. Lane 2: hybridization of cyclophilin probe to yeast RNA. Lanes 3, 4, 5: hybridization of cyclophilin probe to 5 μg RV, LV epicardial and LV endocardial RNA, respectively. (Nucleotide mismatches between the ferret cyclophilin sequence and mouse primers used for cloning the cyclophilin probe can account for the double bands seen in the final assay.) Lane 6: full length undigested fKChIP2b probe. Probe was designed towards the first 247 nt of fKChIP2b and thus would hybridize to 247 nt of fKChIP2b, 169 nt of fKChIP2 and 73 nt of fKChIP2a. Lane 7: hybridization of fKChIP2b probe to yeast RNA. Lanes 8, 9, 10: hybridization of fKChIP2b probe to 10 μg RV, LV epicardial and LV endocardial RNA, respectively. The hybridization signals for fKChIP2b, 2, and 2a are indicated by one, two and three asterisks, respectively. For immunoblot analysis, 10 μg HEK 293, COS, CHO, or Xenopus oocyte or 75 μg RV, LV epicardium, or LV endocardium protein was separated in each lane. HEK-2, −2a, or −2b refers to HEK 293 cells transfected with fKChIP2, 2a or 2b. B, immunoblot with fKChIP2b antibody. C, immunoblot with fKChIP2b antibody pre-incubated with fKChIP2b peptide used for antibody production. Exposures were equal for B and C. D, immunoblot with fKChIP2b antibody on protein from uninjected oocytes; non-transfected COS, CHO, or HEK 293 cells; and transfected HEK 293 cells. Exposure based on detection of HEK-2b as positive control. E, immunoblot with pan-fKChIP2 antibody on protein from uninjected oocytes; non-transfected COS, CHO, or HEK 293 cells; and transfected HEK 293 cells. Exposure based on detection of fKChIPs in transfected HEK 293 cells. fKChIP2, 2a and 2b are 29, 26, and 31 kDa, respectively.

Functional characterization of ferret KChIP2 isoforms

To analyse functional differences between the fKChIP2 isoforms, fKv4.3 and the individual fKChIPs were coexpressed in Xenopus oocytes for analysis of basic gating parameters with two-microelectrode voltage clamp. Data are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 1.

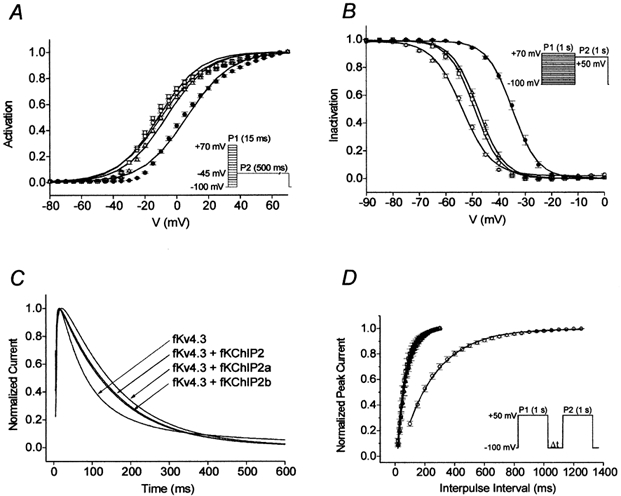

Figure 2. Functional characterization of fKChIP2 isoforms.

Symbols: ○, fKv4.3; □, fKv4.3 + fKChIP2; •, fKv4.3 + fKChIP2a; and Δ, fKv4.3 + fKChIP2b. Data points are means ± s.e.m.A, mean steady-state activation relationships (saturating tail current protocol in inset) approximated by single Boltzmann distributions. B, mean steady-state inactivation relationships (double pulse protocol in inset) fitted with single Boltzmann distributions. C, effects of fKChIP2 isoforms on Kv4.3 inactivation kinetics (2 s pulse to +50 mV, VH=−100 mV). For illustrative purposes, currents have been normalized and the first 600 ms are shown. D, effects of fKChIP2 isoforms on fKv4.3 recovery kinetics (double-pulse protocol in inset). Mean data points fit with single exponential functions.

Table 1.

Effects of fKChIP2 isoforms on fKv4.3 gating parameters and comparison to native LV epicardial myocytes

| Xenopus oocytes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fKv4.3 | fKv4.3 + fKChIP2 | fKv4.3 + fKChIP2a | fKv4.3 + fKChIP2b | LV epicardial myocytes * | |

| V½,act (mV) | −9.8 (7) | −11.5 (7) | 6.3 (7) | −6.6 (8) | 22.5 |

| τ1, inact,+50mV (ms) | 67.0 ± 4.6 (6) | 148.6 ± 5.9 (7) | 153.6 ± 3.3 (5) | 139.2 ± 3.8 (7) | 75.7 ± 4.8 |

| τ2, inact,+50mV (ms) | 489.4 ± 5.3 (6) | — | — | — | — |

| % τ1,inact | 0.808 ± 0.007 (6) | — | — | — | — |

| V½,inact (mV) | −53.8 (7) | −49.0 (7) | −34.7 (8) | −47.7 (8) | −9 |

| kinact (mV) | 5.5 (7) | 4.8 (7) | 4.8 (8) | 4.9 (8) | 5.45 |

| τrec,−100 mV (ms) | 229.2 ± 2.4 (7) | 54.6 ± 0.6 (6) | 60.8 ± 0.6 (6) | 63.3 ± 0.4 (8) | 51.2 ± 2.6 † |

LV epicardial myocyte data from Brahmajothi et al. (1999).

−70mV. Values of n are given in parentheses.

Activation

The mean steady-state activation data under each expression condition (measured using a standard saturating tail current protocol; Fig. 2A, inset) was approximated by a single Boltzmann relationship. fKChIP2 and 2b produced minimal shifts in the V1/2 of activation compared to fKv4.3 expressed alone. In contrast, fKChIP2a caused a ∼16 mV depolarizing shift in the mean V1/2 of activation.

Inactivation

The mean steady-state inactivation data under each expression condition (protocol in Fig. 2B, inset) was well fitted with a single Boltzmann relationship. Coexpression of fKv4.3 and fKChIP2 or 2b resulted in small shifts in V1/2 values of inactivation compared to fKv4.3 expressed alone. However, similar to its effect on activation, coexpression of fKv4.3 and fKChIP2a resulted in a ∼19 mV depolarizing shift in the steady-state inactivation relationship.

The kinetics of macroscopic inactivation (2000 ms pulse to +50 mV) for fKv4.3 were best described as a double exponential process (Fig. 2C). However, in the presence of fKChIPs inactivation was best described as a single exponential process and was approximately two times slower.

Recovery

Under all conditions mean recovery kinetics (VH= −100 mV; protocol in Fig. 2D, inset) were well described as single exponential processes. Compared to fKv4.3 expressed alone, expression with any of the fKChIP2 isoforms accelerated the kinetics of recovery ∼4-fold.

Expression profile of ferret KChIP2 isoforms

Our functional characterization showed that each fKChIP2 isoform had a different modulatory effect on the gating properties of fKv4.3. Since the functional characteristics of fKChIP2a came closest to mimicking the native rapidly recovering Ito phenotype, we hypothesized that fKChIP2a would be the most abundantly expressed fKChIP2 isoform in the ferret heart RV and LV epicardium. Previous studies have used RT-PCR to suggest that KChIP2a is the most abundant KChIP2 isofrom in the whole human heart (Decher et al. 2001; Bähring et al. 2001). We therefore examined mRNA and protein expression patterns of fKChIP2 isoforms across the ventricles of the ferret heart.

RNase protection assays

The mRNA expression pattern of the fKChIP2 isoforms was analysed by RNase protection assays. The RNase protection assay probe was designed to the first 247 nt of the fKChIP2b coding sequence across the 5′ length variations of the fKChIP2 isoforms. This probe would thus hybridize to 247 nt of fKChIP2b, 169 nt of fKChIP2 and 73 nt of fKChIP2a. Hybridization of this probe to RNA isolated from the RV, LV epicardium and LV endocardium showed one prominent band corresponding to the size of fKChIP2b (Fig. 3A). Bands corresponding to the sizes of fKChIP2 and 2a were present at barely detectable levels. A distinct gradient of fKChIP2b mRNA was seen across the walls of the ventricle with greatest expression in the LV epicardium and RV and least expression in the LV endocardium. Although fKChIP2 and 2a also seemed to display an expression gradient across the ventricles, their low expression levels prevented definitive determination. The cyclophilin probe verified the integrity of RNA used in the hybridizations.

Immunoblot analyses

Our RNase protection assays showed that fKChIP2b was the predominant fKChIP2 isoform and was expressed in a gradient across the ventricles. Previous studies have shown that RNA and protein expression patterns in the heart do not always correspond (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). We therefore examined the ventricular protein expression pattern of fKChIP2b, the most abundantly expressed fKChIP2 isoform.

We designed an antibody specific to the fKChIP2b isoform (see Fig. 1). To determine the specificity of the fKChIP2b antibody, HEK 293 cells were transfected with fKChIP2, 2a or 2b. Transfection was verified by immunoblot using the pan-fKChIP2 antibody which recognizes all fKChIP2 isoforms. Subsequent immunoblot analysis with the fKChIP2b antibody revealed no bands in cells expressing fKChIP2 or 2a, while a single prominent band (∼31 kDa, corresponding to the predicted size of fKChIP2b) was observed in cells transfected with fKChIP2b (Fig. 3B), thereby verifying specificity of the antibody for the fKChIP2b isoform.

Immunoblot analysis with the fKChIP2b antibody was next conducted on protein preparations obtained from ferret RV, LV epicardial and LV endocardial tissue samples. In contrast to transfected HEK 293 cells, multiple ‘background’ bands were observed in all tissue preparations (Fig. 3B). However, only the band corresponding to the size of fKChIP2b displayed a gradient of expression across the ventricles (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the fKChIP2b protein expression pattern parallels the mRNA expression pattern, with greatest expression in the LV epicardium and RV and least expression in the LV endocardium. Furthermore, all distinct bands were absent when the antibody was preincubated with the fKChIP2b peptide utilized for antibody production, although background ‘smearing’ prominent around ∼25 and ∼43 kDa remained (Fig. 3C). The block of all distinct bands by preabsorbing the antibody suggests that the ‘background’ bands represent proteins with epitopes similar to the fKChIP2b antigenic peptide. However, the additional bands represent proteins of unknown identity.

DISCUSSION

The three KChIP2 isoforms we have identified, fKChIP2, 2a and 2b, have distinct expression patterns in the ferret heart. fKChIP2b is the most abundant of these three isoforms. It displays a transmural gradient of mRNA and protein, with greatest expression in the LV epicardium and RV and minimal expression in the LV endocardium. The gradient of fKChIP2b mRNA and protein expression parallels the distribution of the rapidly recovering Ito in the ferret heart (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). Ferret KChIP2 and 2a may be similarly distributed, but our detection methods were not sufficiently sensitive to allow a conclusive determination.

KChIPs have been implicated in the generation of the Ito density gradient in the human heart (Rosati et al. 2001). Electrophysiologically, the action potential morphologies, Ito biophysical characteristics and distributions of Ito phenotypes across the LV free wall of the ferret are very similar to those observed in human (Näbauer et al. 1996; Brahmajothi et al. 1999). Similarly, the KChIP expression gradient we observe in the ferret corresponds to the KChIP expression gradient in the human suggesting that similar mechanisms of Ito regulation are involved in both species. In contrast, KChIP expression is uniform across the LV free wall of the rat heart (Rosati et al. 2001). While analyses in human have not distinguished between KChIP2 isoforms, previous studies suggest that the equivalent of fKChIP2a is the most abundant in the human heart (Bähring et al. 2001). In contrast, the equivalents of ferret KChIP2b and 2 are the most abundant in the mouse heart, where it has been demonstrated that KChIP2 gene deletion leads to the absence of Ito expression (Kuo et al. 2001). Therefore, our results on both the KChIP gradients and isoform distributions are not specific to the ferret but are common to many studied species.

Comparison to the native rapidly recovering LV epicardial Ito phenotype: 2b or not 2b?

It is clear from our results that significant differences exist in the modulatory effects exerted by different KChIP2 isoforms on Kv4.3 channel function. Compared to fKv4.3 expressed alone in Xenopus oocytes, the native rapidly recovering Ito phenotypes observed in ferret LV epicardial myocytes have: (i) faster kinetics of recovery; (ii) comparable time constants of inactivation; (iii) single exponential inactivation kinetics; and (iv) more depolarized V1/2 values of steady-state activation and inactivation (Table 1) (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). Some of these differences may be due to differences in the recording solutions used and the use of Xenopus oocytes as an expression system. It is also possible that heteromultimers of fKv4.2 + fKv4.3 α subunits may underlie the ferret LV epicardial Ito. With these caveats, all of the fKChIP2 isoforms we have characterized produce an acceleration of recovery kinetics and single exponential kinetics of inactivation, properties which are also displayed by the native rapidly recovering Ito. The closest combination for reconstituting the native LV epicardial Ito steady-state activation and inactivation characteristics would be fKv4.3 + fKChIP2a. However, fKChIP2a is expressed at minimal levels in the ferret heart compared to fKChIP2b. This suggests that regulatory factors in addition to KChIPs may be involved (see further discussion below).

We focused our experiments on fKv4.3 because it is abundantly expressed throughout the ferret LV. However, ferret heart also expresses Kv4.2. In contrast to the ubiquitous expression of Kv4.3, Kv4.2 is expressed in a gradient across the wall of the ferret LV in a pattern that follows the distribution of the rapidly recovering Ito phenotype (Brahmajothi et al. 1999). In addition, ferret RV appears to express Kv4.2 most abundantly. While the functional implications of these differential Kv4 expression patterns are at present unclear, they may provide further localized mechanisms for selective modulation of distinct ventricular Ito phenotypes by the various KChIP2 isoforms.

Based upon evidence that mice lacking the KChIP2 gene display a complete loss of Ito and susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia, KChIPs are clearly essential components underlying cardiac Ito expression (Kuo et al. 2001). Functionally, KChIPs also significantly accelerate the kinetics of recovery from inactivation to rates similar to the native rapidly recovering Ito. However, KChIPs alone do not reconstitute all gating characteristics of the native rapidly recovering Ito in heterologous cell expression systems. It is likely that Kv4 channels underlying Ito are modified by KChIPs in combination with other factors. For example, all of the fKChIP2 isoforms we examined caused a twofold slowing in the kinetics of fKv4.3 inactivation. Kv4 channels and KChIPs may therefore interact with or be modified by additional components that accelerate inactivation, such as a Kv-accelerating factor(s) (KAF) (Nadal et al. 2001). Other endogenous components in combination with KChIPs may also modulate the rapidly recovering Ito in the heart, although none of these components alone fully reconstitutes the native rapidly recovering Ito (Kuryshev et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2001).

Heterologous expression systems: interpretive implications

Based upon our immunoblot analysis of common cell types used for electrophysiological studies, neither the pan-fKChIP2 nor the fKChIP2b antibody detected protein in uninjected Xenopus oocytes. However, non-transfected CHO, COS and HEK 293 cells all express an ∼21 kDa protein that is recognized by the pan-fKChIP2 antibody, but does not correspond to the sizes of KChIP2, 2a or 2b. This protein may correspond to the size of an unpublished hypothetical alternatively spliced KChIP deposited in GenBank (KChIP2.5; GenPept AAK53708).

These results may have important interpretive implications for the variations that have been reported for functional effects of KChIPs in different cell types. For example, the results of An et al. (2000) show significant hyperpolarizing shifts in the V1/2 of activation for rKv4.2 + KChIP1 in CHO cells but no shift when hKv4.3 + KChIP1 are expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Bähring et al. (2001) observed depolarizing shifts in the V1/2 of activation for coexpression of hKv4.3 and KChIP2 in HEK 293 cells. However, Decher et al. (2001) observed no shift upon expression of hKv4.3 with KChIP2 isoforms in Xenopus oocytes.

Our immunoblot results thus advocate the need for caution in comparing the results of heterologous expression studies to native physiological properties. In particular, while our data do not definitively demonstrate the presence of an unidentified KChIP2-like protein in HEK, COS and CHO cells, it lends support to the hypothesis that such a regulatory protein(s) may account, at least in part, for differences reported on the effects of KChIPs on various Kv4 channels expressed in these cell lines.

Conclusions

Three KChIP2 isoforms, fKChIP2, 2a, and 2b, are found in the ferret heart. Ferret KChIP2b is the most abundantly expressed of these isoforms. Ferret KChIP2b mRNA and protein expression is heterogeneous and parallels the distribution of the rapidly recovering Ito observed in the ferret heart, thus supporting the hypothesis that fKChIPs are modulators of this Ito phenotype. While all three fKChIP2 isoforms produce single exponential inactivation kinetics and accelerate recovery kinetics to rates which approach those of the native LV epicardial Ito phenotype, they exert differential effects on steady-state gating characteristics. Our data supports the role of fKChIP2 isoforms in modulation of the rapidly recovering Ito. However, fKChIPs only partially reconstitute this current phenotype suggesting that additional regulatory factors are also likely to be involved.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant HL52874 to HCS and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 0140005N to D.L.C.

REFERENCES

- An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling HP, Mendoza G, Hinson JW, Mattsson KI, Strassle BW, Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Yan G, Shimizu W, Burashnikov A. Electrical heterogeneity, the ECG, and cardiac arrhythmias. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 222–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bähring R, Dannenberg J, Peters HC, Leicher T, Pongs O, Isbrandt D. Conserved Kv4 N-terminal domain critical for effects of Kv channel-interacting protein 2. 2 on channel expression and gating. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:23888–23894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Trimmer JS, Merlie JP, Nerbonne JM. Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits in adult rat heart. Relation to functional K+ channels? Circulation Research. 1995;77:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmajothi MV, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Morales MJ, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM, Strauss HC. Distinct transient outward potassium current (Ito) phenotypes and distribution of fast-inactivating potassium channel alpha subunits in ferret left ventricular myocytes. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;113:581–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Qu Y, Strauss HC. The calcium-independent transient outward potassium current in isolated ferret right ventricular myocytes. I. Basic characterization and kinetic analysis. Journal of General Physiology. 1993;101:571–601. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer MB, Campbell DL, Rasmusson RL, Lamson DR, Morales MJ, Zhang Y, Strauss HC. Cloning and characterization of an Ito-like potassium channel from ferret ventricle. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:H1383–1395. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decher N, Uyguner O, Scherer CR, Karaman B, Yüksel-Apak M, Busch AE, Steinmeyer K, Wollnik B. hKChIP2 is a functional modifier of hKv4. 3 potassium channels: Cloning and expression of a short hKChIP2 splice variant. Cardiovascular Research. 2001;52:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00374-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franqueza L, Valenzuela C, Eck J, Tamkun MM, Tamargo J, Snyders DJ. Functional expression of an inactivating potassium channel (Kv4. 3) in a mammalian cell line. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;41:212–219. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Cheng CF, Clark RB, Lin JJ, Lin JL, Hoshijima M, Nguyêñ-Trân VT, Gu Y, Ikeda Y, Chu PH, Ross J, Giles WR, Chien KR. A defect in the Kv channel-interacting protein 2 (KChIP2) gene leads to a complete loss of Ito and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryshev YA, Gudz TI, Brown AM, Wible BA. KChAP as a chaperone for specific K+ channels. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;278:C931–941. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.5.C931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, überfuhr P, Steinbeck G. Regional differences in current density and rate-dependent properties of the transient outward current in subepicardial and subendocardial myocytes of human left ventricle. Circulation. 1996;93:168–177. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal MS, Amarillo Y, De Miera EV, Rudy B. Evidence for the presence of a novel Kv4-mediated A-type K+ channel-modifying factor. Journal of Physiology. 2001;537:801–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM. Molecular analysis of voltage-gated K+ channel diversity and functioning in the mammalian heart. In: Page E, Fozzard HA, Solaro RJ, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Cardiovascular System, The Heart. I. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 568–594. [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S, Morohashi Y, Muraki K, Tomita T, Watanabe M, Iwatsubo T, Imaizumi Y. Molecular cloning and expression of the novel splice variants of K+ channel-interacting protein 2. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;282:96–102. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Zobel C, Backx PH. The molecular physiology of the cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito) in normal and diseased myocardium. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2001;33:851–872. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, Pan Z, Lypen S, Wang HS, Cohen I, Dixon JE, McKinnon D. Regulation of KChIP2 potassium channel β subunit gene expression underlies the gradient of transient outward current in canine and human ventricle. Journal of Physiology. 2001;533:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0119b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettwer E, Amos GJ, Posival H, Ravens U. Transient outward current in human ventricular myocytes of subepicardial and subendocardial origin. Circulation Research. 1994;75:473–482. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EK, Alvira MR, Levitan ES, Takimoto K. Kv β subunits increase expression of Kv4. 3 channels by interacting with their C termini. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:4839–4844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeola SW, Snyders DJ. Electrophysiological and pharmacological correspondence between Kv4. 2 current and rat cardiac transient outward current. Cardiovascular Research. 1997;33:540–547. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Jiang M, Tseng GN. minK-related peptide 1 associates with Kv4. 2 and modulates its gating function: potential role as beta subunit of cardiac transient outward channel? Circulation Research. 2001;88:1012–1019. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]