Abstract

Lyotropic anions with low free energy of hydration show both high permeability and tight binding in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel pore. However, the molecular bases of anion selectivity and anion binding within the CFTR pore are not well defined and the relationship between binding and selectivity is unclear. We have studied the effects of point mutations throughout the sixth transmembrane (TM6) region of CFTR on channel block by, and permeability of, the highly lyotropic Au(CN)2− anion, using patch clamp recording from transiently transfected baby hamster kidney cells. Channel block by 100 μm Au(CN)2−, a measure of intrapore anion binding affinity, was significantly weakened in the CFTR mutants K335A, F337S, T338A and I344A, significantly strengthened in S341A and R352Q and unaltered in K329A. Relative Au(CN)2− permeability was significantly increased in T338A and S341A, significantly decreased in F337S and unaffected in all other mutants studied. These results are used to define a model of the pore containing multiple anion binding sites but a more localised anion selectivity region. The central part of TM6 (F337-S341) appears to be the main determinant of both anion binding and anion selectivity. However, comparison of the effects of individual mutations on binding and selectivity suggest that these two aspects of the permeation mechanism are not strongly interdependent.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), in common with most types of Cl− channels that have been studied in detail (e.g. Bormann et al. 1987; Halm & Frizzell, 1992; Rychkov et al. 1998; Smith et al. 1999; Qu & Hartzell, 2000), shows a lyotropic anion permeability sequence (Tabcharani et al. 1997; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1998; Dawson et al. 1999; Smith et al. 1999), meaning that anions which are more easily dehydrated (lyotropes) tend to show a higher permeability than those which retain their waters of hydration more strongly (kosmotropes). In addition to showing high permeability, lyotropic anions also bind relatively tightly within the CFTR pore. Experimentally, this is manifested in two ways. First, lyotropic anions with high permeability often show low conductance, suggesting a longer residency time within the pore than less permeant anions (Mansoura et al. 1998; Linsdell, 2001a, b). Secondly, lyotropic anions are effective open channel blockers of Cl− permeation (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a, b; Linsdell & Gong, 2002), suggesting that they bind tightly enough within the pore to slow the overall rate of ionic flux. The fact that both permeability and apparent intrapore binding affinity follow an approximate lyotropic sequence supports the hypothesis that anion dehydration is a limiting step in anion permeation through the CFTR channel pore (Dawson et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a).

Although both anion permeability and anion binding in CFTR show similar dependencies on anion hydration energy, recent evidence suggests that these two facets of the permeation mechanism are only weakly interdependent (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a), which has led to the suggestion that they may show distinct structural bases within the pore (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a). Two opposing scenarios have been proposed. First, anion binding might be determined at a small number of discrete sites, while anion permeability is determined over the entire pore length (Dawson et al. 1999; Smith et al. 1999). Alternatively, we have suggested that anion permeability is predominantly determined at a single discrete site and that anion binding sites may be more diffuse (Linsdell et al. 2000; Linsdell 2001a).

Structure-function investigations of the CFTR channel pore have emphasised the dominant role played by the sixth transmembrane region (TM6) in determining permeation properties (Dawson et al. 1999; McCarty, 2000; Gupta et al. 2001). Numerous TM6 residues have been proposed to contribute to anion binding sites, for example R334 (Smith et al. 2001), K335 (Mansoura et al. 1998), F337 (Linsdell 2001a), T338 (Linsdell 2001a), S341 (McDonough et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 2000), R347 (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; but see Cotten & Welsh, 1999) and R352 (Guinamard & Akabas, 1999). Our previous work has emphasised the role of adjacent TM6 residues F337 (Linsdell et al. 2000) and T338 (Linsdell et al. 1998) in controlling selectivity between different anions. However, a comparative examination of the relative roles of different TM6 residues in determining permeant anion binding and permeability has not previously been carried out. In the present study, we compare the effects of single point mutations at different sites within TM6 on anion binding and selectivity. Wild-type and mutant channels are probed using the lyotropic Au(CN)2− anion, which shows both high permeability (Smith et al. 1999) and tight binding (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell & Gong, 2002) within the wild-type CFTR pore.

METHODS

Mutagenesis and transient expression of CFTR

Wild-type and mutant forms of human CFTR were transiently transfected into baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells along with enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP), allowing successfully transfected cells to be identified during a patch clamp experiment using fluorescence microscopy. To ensure consistent coexpression, CFTR cDNA was subcloned from the pNUT vector (Chang et al. 1998) into the bicistronic pIRES2-EGFP vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) using PstI restriction sites. Site-directed mutagenesis of CFTR was then carried out within the pIRES2-EGFP vector using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), as follows. The thermal cycling cocktail contained a final concentration of 100–200 ng pIRES2-EGFP-CFTR plasmid DNA, 1.5 × Pfu reaction buffer, 250 ng of each of two synthesised complementary oligonucleotide primers containing the desired mutation (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada), 500 μm each of dNTPs and 5 U Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Temperature cycling was performed using a Progene thermal cycler (Techne, Princeton, NJ, USA), with a short (30 s) denaturing step at 95 °C followed by 20 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 60 s) and extension (68 °C for 20 min.). Following cycling, DNA was treated with DpnI for 2 h at 37 °C to digest template DNA, transformed into competent XL-1 Blue Escherichia coli cells and grown overnight on LB agar plates containing 30 μg ml−1 kanamycin (Life Technologies). Five to ten separate colonies were selected and expanded, and plasmid DNA was isolated for confirmation of the desired mutation by sequencing using the T7 version 2.0 Sequenase kit (Amersham, Baie d'Urfe, PQ, Canada).

BHK cells, kindly provided by Dr John Hanrahan (McGill University, Montréal, PQ, Canada) were cultured as described in the accompanying manuscript (Linsdell & Gong, 2002), except that methotrexate, resistance to which is conferred by the pNUT vector, was omitted from the medium. For patch clamp studies, the cells were seeded at low density onto 22 mm glass cover slips. One day after seeding, cells were transfected with 0.5 μg ml−1 wild-type or mutated pIRES2-EGFP-CFTR DNA, or, for control studies, pIRES2-EGFP vector alone. For transfection, DNA was pre-complexed with Plus reagent (Life Technologies) for 15 min, followed by Lipofectamine (Life Technologies) for an additional 15 min, all at room temperature. Complexed DNA was then diluted in supplement-free medium to the required concentration and added to the cells. After 5 h at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere, the medium was completely replaced with normal medium containing 5 % fetal bovine serum. Transfected cells could be identified by fluorescence microscopy within 24 h and cells were used for patch clamp recording 1–4 days after transfection.

Detection of CFTR protein

BHK cells were transfected with either pIRES2-EGFP-CFTR or the pIRES2-EGFP vector alone. After 48 h, cells were lysed with 1.5 % sodium dodecyl sulphate and DNA was sheared by passing through a 27 gauge needle. 40 μg total protein was run on a 7.5 % polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Immunoblotting was performed using the M3A7 primary antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) at 1:500 dilution followed by incubation with the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-labelled sheep anti-mouse; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at 1:10,000 dilution. Detection was carried out using the ECL Plus kit, following manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Choice of mutations

Previously we have studied the effects of multiple substitutions for the TM6 residues F337 (Linsdell et al. 2000; Linsdell, 2001a) and T338 (Linsdell et al. 1998). In order to obtain a more comprehensive overview of the roles of different TM6 residues, here we compare the relative effects of a single mutation at each of a number of different residues. Some of these have previously been associated with altered anion selectivity (F337S, T338A; Linsdell et al. 1998, 2000), altered anion:cation selectivity (R352Q; Guinamard & Akabas, 1999), or disrupted open channel blocker binding (S341A; McDonough et al. 1994). In other cases (K329, R334, K335, I344, T351), alanine substitutions were employed. In spite of its previous association with altered anion binding (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996), mutation of R347 was avoided, since most mutations at this site appear to grossly perturb pore structure due to disruption of a salt bridge between TMs (Cotten & Welsh, 1999). Apart from R347, mutagenesis was carried out at all TM6 residues from R334 to R352 which have previously been suggested, on the basis of substituted cysteine accessibility mutagenesis, to have side chains which are in contact with the aqueous pore lumen (Cheung & Akabas, 1996; Liu et al. 2001).

Electrophysiological recording

Excised, inside-out patch clamp recordings were made as described in the accompanying manuscript (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). For whole cell recordings, the bath (extracellular) solution contained (mm): 140 HCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Tes and the pipette (intracellular) solution contained (mm): 110 aspartic acid, 30 HCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Tes, 1 MgATP, 0.1 EGTA; both adjusted to pH 7.4 with N-methyl-d-glucamine. Whole cell current-voltage relationships were constructed using 500 ms voltage steps to between −100 and +100 mV from a holding potential of 0 mV. Voltage steps were applied at a frequency of 0.2–0.7 Hz. Following attainment of the whole cell configuration by application of excess suction to the pipette, and recording of background currents, CFTR was activated by addition of a combination of forskolin (10 μM) and the membrane-permeant adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) analogue 8-Br-cAMP to the bath solution. Both were added from 100-fold stock solutions in normal extracellular solution. Forskolin was initially solubilised at 50 mm in DMSO. Pipette resistances for whole cell experiments were 3–5 MΩ. Whole cell currents were filtered at 2 kHz and digitised at 5 kHz as described for inside-out patch currents (Linsdell & Gong, 2002).

For Au(CN)2− permeability measurements in excised patches, the pipette (extracellular) solution contained (mm): 150 KAu(CN)2 or 150 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Tes and the bath (intracellular) solution contained (mm): 150 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 Tes. Macroscopic current reversal potentials (Vrev) were estimated by fitting a polynomial function to the leak-subtracted current-voltage (I-V) relationship and were used to estimate the permeability of Au(CN)2− relative to that of Cl− (PAu(CN)2) according to the equation:

| (1) |

where [X]i and [X]o refer to intracellular and extracellular concentrations of anion X− and R, T and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings. Other methodological details are exactly as described (Linsdell & Gong, 2002).

RESULTS

Transient expression of CFTR

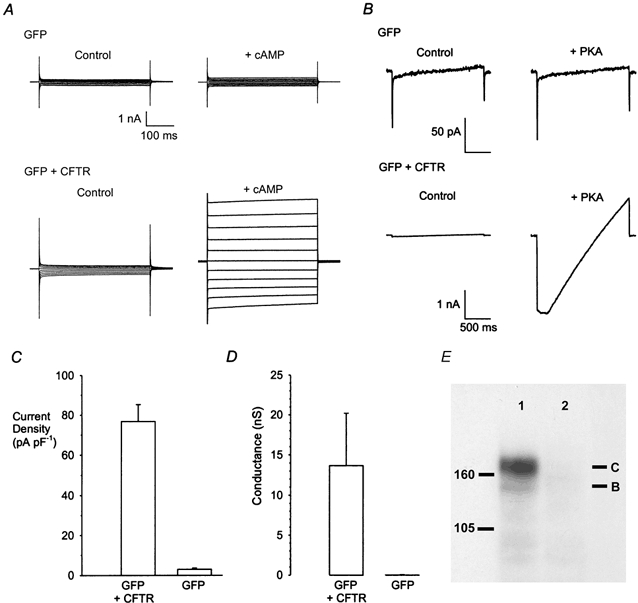

In the accompanying manuscript we characterised the effects of Au(CN)2− on wild-type CFTR channels stably expressed in BHK cells (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). In order efficiently to compare the interaction of Au(CN)2− with multiple CFTR mutants, we have transiently expressed CFTR together with GFP, allowing CFTR-expressing cells to be identified by fluorescence microscopy within 24 h of transfection. Coexpression of wild-type CFTR and GFP, but not GFP alone, led to the appearance of large cAMP-activated whole cell Cl− currents (Fig. 1A, C) and PKA- and ATP-dependent currents in inside-out membrane patches (Fig. 1B, D); both whole cell and macroscopic inside-out patch currents were indistinguishable from those observed in BHK cells stably expressing CFTR (e.g. Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Such currents were not observed in non-green cells following transfection with pIRES2-EGFP-CFTR (not shown). Finally, BHK cell transfection with pIRES2- EGFP- CFTR, but not pIRES2-EGFP, led to the production of both core glycosylated (band B) and fully glycosylated (band C) CFTR protein, as judged by Western blotting (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Expression of CFTR Cl− currents in transfected BHK cells.

A, example whole cell currents recorded from BHK cells expressing GFP alone (top) or GFP along with wild-type CFTR (bottom), before (control) and after (+ cAMP) addition of forskolin (10 μm) plus 8-Br-cAMP (100 μm) to the extracellular solution. B, example macroscopic currents recorded from inside-out patches from BHK cells expressing GFP alone (top) or GFP along with CFTR (bottom), in response to a depolarising voltage ramp (−100 to +60 mV, holding potential 0 mV), before (control) and after (+ PKA) addition of 50 nm PKA in the continuous presence of 1 mm ATP. C, mean increase in whole cell current amplitude at +100 mV in response to forskolin plus 8-Br-cAMP, estimated from experiments like that shown in A. Mean of data from 5 cells in each case. D, mean increase in macroscopic current conductance in response to PKA, estimated from experiments like that shown in B. Mean of data from 14 GFP + CFTR-expressing cells and 7 GFP-expressing cells. E, Western blots of CFTR protein in BHK cells transfected with pIRES2-EGFP-CFTR (lane 1) or pIRES2-EGFP (lane 2). Lines to the left indicate the positions of 105 and 160 kDa molecular weight markers.

Au(CN)2− block of TM6 mutants

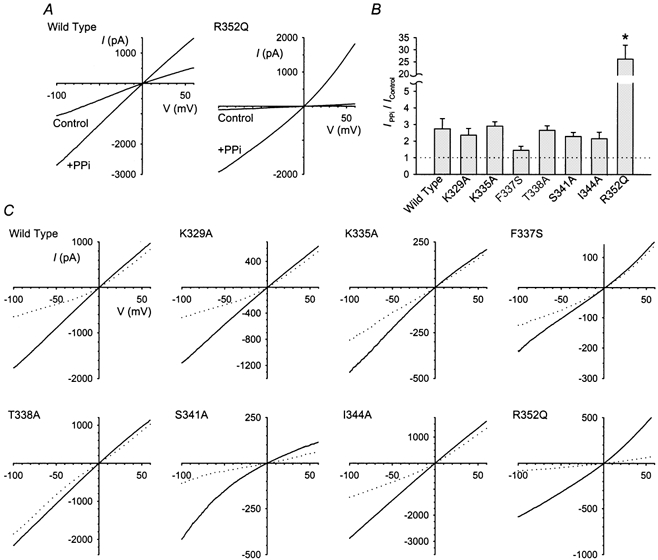

Numerous amino acid residues within TM6 of CFTR have been proposed as potentially contributing to anion binding sites (see Introduction). Anion binding was compared between different mutants by studying the block of Cl− permeation by the lyotropic Au(CN)2− anion, a high-affinity probe of intrapore anion binding sites (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). In order to avoid the potentially confounding effects of intracellular Au(CN)2− on CFTR channel gating (Linsdell & Gong, 2002), block of macroscopic CFTR currents in inside-out membrane patches by intracellular Au(CN)2− was examined following current stimulation with PKA and ATP plus 2 mm sodium pyrophosphate (PPi) (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Following attainment of full current amplitude with PKA and ATP, 2 mm PPi increased wild-type CFTR current at −100 mV by 2.74 ± 0.61-fold (n = 6) (Fig. 2A and B), almost identical to the stimulation observed in stably transfected BHK cell patches under similar conditions (2.49 ± 0.29-fold; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Currents carried by the CFTR mutants K329A, K335A, T338A, S341A and I344A were also stimulated an average of 2–3-fold by PPi (Fig. 2B). The stimulation of F337S appeared somewhat less (1.46 ± 0.24-fold, n = 5), although this was not significantly different from wild-type (P > 0.1, Student's two-tailed t test). In contrast, while only very small R352Q currents were recorded in the presence of PKA and ATP, currents were massively stimulated on addition of PPi (by an average of 26.3 ± 5.7-fold; Fig. 2A, B). Although single channel recordings were not carried out, this implies that the channel open probability for R352Q in the absence of PPi is very low (< 0.04). Two other mutants were also transfected into BHK cells; however, even in the presence of PPi, currents carried by R334A and T351A were too small for proper analysis (not shown).

Figure 2. Block of PPi-stimulated wild-type and mutant CFTR Cl− currents by Au(CN)2−.

A, example CFTR I-V relationships recorded from inside-out membrane patches from BHK cells transfected with wild-type (left) or R352Q-CFTR (right). Currents were recorded before (control) and after (+ PPi) addition of 2 mm PPi to the intracellular solution. B, mean change in CFTR current amplitude at −100 mV following addition of PPi. The PPi-induced increase in current amplitude was significantly different from wild-type only in R352Q (* P < 0.001, Student's two-tailed t test). C, example CFTR I-V relationships for different mutants recorded before (continuous lines) and after (dotted lines) addition of 100 μm Au(CN)2− to the intracellular solution, following maximal current stimulation with PKA and PPi.

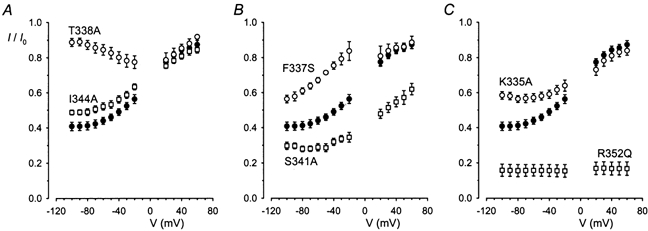

Examples of the effects of addition of 100 μm Au(CN)2− to the intracellular solution on PPi-stimulated wild-type and mutant CFTR currents are shown in Fig. 2C. Although in each case Au(CN)2− reduced the current amplitude, its blocking effects were altered in most mutants, as shown more clearly in the mean fractional current-voltage relationships shown in Fig. 3. The effects of this concentration of Au(CN)2− on wild-type CFTR were indistinguishable from those observed in stably transfected BHK cell patches (compare Fig. 3 with Fig. 5C, Linsdell & Gong, 2002). However, for all mutants studied except K329A, the blocking effects of 100 μm Au(CN)2− at −100 mV were significantly altered relative to wild-type (P < 0.05 in each case, Student's two-tailed t test). Comparison between different channel variants at −100 mV reveals the sensitivity to this concentration of Au(CN)2− is R352Q > S341A > wild-type, K329A > I344A > K335A = F337S > T338A. At depolarised voltages, where the blocking effects of 100 μm Au(CN)2− are weak, block of most mutants was not significantly different from wild-type; the only differences in Au(CN)2− sensitivity at +60 mV were R352Q > S341A > wild-type.

Figure 3. Sensitivity of different CFTR variants to block by Au(CN)2−.

Each panel shows the mean fraction of control current remaining (I/I0) following addition of 100 μm Au(CN)2− as a function of membrane potential. In each case filled symbols represent wild-type. Results for K329A were indistinguishable from wild-type (not shown). Mean of data from 4–6 cells.

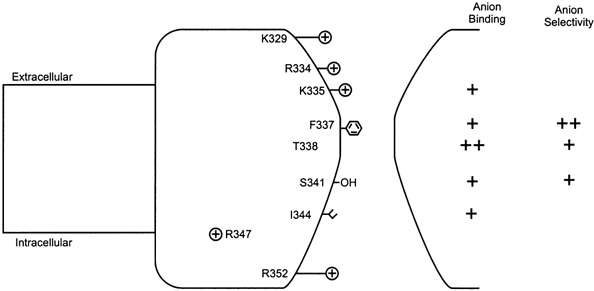

Figure 5. A simple model of the pore.

The present study attempted to address the roles of amino acid residues in TM6 from K329, predicted to lie at the extracellular end of this TM region, to R352 at the intracellular end. Many of these residues (K329, R334, K335, F337, S341, I344, R347, R352) have side chains which have been suggested, on the basis of substituted cysteine accessibility mutagenesis, to be in contact with the aqueous pore lumen (Cheung & Akabas, 1996), although this now appears not to be the case for R347 (Cotten & Welsh, 1999). The polar side chain of T338 was proposed by Cheung & Akabas (1996) to be non-pore-lining, suggesting that the effects of mutations at this residue were indirect (Linsdell et al. 1998); however, the normal orientation of this amino acid side chain has also been refuted by others (Liu et al. 2001). The relative effects of mutagenesis of different residues on lyotropic anion binding (judged by Au(CN)2− block of Cl− current) and lyotropic anion selectivity (judged by Au(CN)2− permeability) are indicated to the right. In this model, both anion binding and anion selectivity are determined primarily over a narrow central region of the pore, although anions also bind in wider vestibule regions on either side of this narrow region (see Discussion).

Although block of PPi-stimulated channels by 100 μm Au(CN)2− was strongly voltage dependent in wild-type and most mutants, consistent with the ‘conduction effect’ of this anion (Linsdell & Gong, 2002), the strong inhibitory effects on R352Q were practically voltage independent. This potent, voltage-independent block is in fact more consistent with the Au(CN)2− ‘gating effect’ (Linsdell & Gong, 2002). Together with the extreme stimulation of R352Q current by PPi (Fig. 2A and B), this suggests that we are unable to separate permeation from gating effects in this mutant and, as such, the potential role of R352Q in contributing to intrapore anion binding cannot be addressed in the present study.

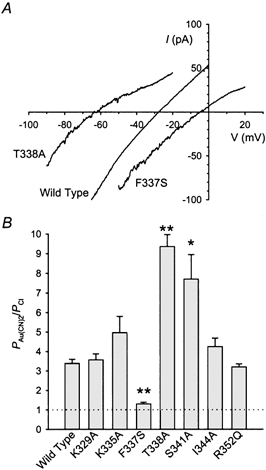

Au(CN)2− permeability of TM6 mutants

DISCUSSION

Previous site-directed mutagenesis studies of CFTR have emphasised the dominant role played by TM6 in forming the pore and determining its permeation properties (Dawson et al. 1999; McCarty, 2000). Point mutations within TM6 have previously been shown to affect interactions between permeant ions and the pore, leading to alterations in anion selectivity (Linsdell et al. 1998, 2000), permeant anion binding (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Mansoura et al. 1998; Linsdell, 2001a) and unitary Cl− conductance (Sheppard et al. 1993; Tabcharani et al. 1993; McDonough et al. 1994; Linsdell et al. 1998; Guinamard et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a; Smith et al. 2001). However, comparative studies of the relative roles of different TM6 residues under identical experimental conditions are lacking. Although other TM regions are also considered likely to be involved in forming the pore, their precise contributions are presently unclear (Dawson et al. 1999; McCarty, 2000; Gupta et al. 2001).

Highly lyotropic anions with low free energy of hydration have been popular probes of the conduction pathway of CFTR (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Mansoura et al. 1998; Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001b) and other Cl− channels (e.g. Bormann et al. 1987; Halm & Frizzell, 1992; Rychkov et al. 1998; Qu & Hartzell, 2000; see Dawson et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001b). In CFTR, lyotropic anions such as SCN− and Au(CN)2− show both higher permeability than Cl− (Gray et al. 1993; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1998; Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001b) and tighter intrapore binding than Cl− (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Mansoura et al. 1998; Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a, b; Linsdell & Gong, 2002). These dual effects of lyotropic anion interactions with the pore suggest that similar forces, most likely involving anion dehydration, are involved in both anion selectivity and intrapore anion binding (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a, b; Dawson et al. 1999). However, the structural bases of anion selectivity and anion binding within the CFTR pore are not well defined. Recent conflicting models have proposed that selectivity is determined over the entire length of the pore (Dawson et al. 1999; Smith et al. 1999) or at a single discrete site (Linsdell et al. 2000). Furthermore, although numerous TM6 residues have been proposed as potentially contributing to anion binding sites (see Introduction), the relative importance of different residues have not been directly compared. In the present study we used the lyotropic Au(CN)2− ion, which shows both high permeability and tight binding within the wild-type CFTR channel pore, to survey the role of residues throughout TM6 in both anion binding and selectivity.

Binding of Au(CN)2− within the pore, assayed by its ability to block Cl− current, was altered in most TM6 mutants studied (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). Most mutations appeared to differentially affect block at hyperpolarised versus depolarised potentials (Fig. 3), although the voltage dependence of block was not analysed quantitatively. Since block at depolarised, but not hyperpolarised voltages was strengthened by reducing the extracellular Cl− concentration (see Fig. 5C, Linsdell & Gong, 2002), we assume that block at strongly hyperpolarised potentials reflects the strength of the interaction between Au(CN)2− ions and the pore in the absence of additional electrostatic repulsion effects due to extracellular Cl− ions (Linsdell et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2001). We therefore consider block at −100 mV to be the best indicator of the relative affinity of Au(CN)2− binding within the pore. At this voltage, block by 100 μm Au(CN)2− was significantly weakened in K335A, F337S, T338A and I334A, significantly strengthened in S341A and R352Q and unaffected in K329A (Fig. 3). The sequence of relative sensitivity to block by 100 μm Au(CN)2− at −100 mV (R352Q > S341A > wild-type, K329A > I344A > K335A = F337S > T338A) suggests that T338 normally makes the strongest contribution to Au(CN)2− binding within the pore, with nearby residues K335 and F337 also making large contributions. Mutagenesis of F337 and T338 has previously been shown to affect block by lyotropic ClO4−, I− and SCN− ions (Linsdell, 2001a). Interestingly, in spite of its previous association with disrupted anion binding within the pore (McDonough et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 2000), S341A showed significantly strengthened Au(CN)2− block at all potentials (Fig. 3), suggesting that the polar hydroxyl side chain of S341 does not contribute to lyotropic anion binding. This raises the possibility that S341 contributes to a relatively kosmotropic anion binding site that would bind Cl− more tightly than Au(CN)2−; disruption of this site might then increase Au(CN)2− occupancy of the pore relative to Cl− occupancy, leading to enhanced Au(CN)2− block of Cl− permeation. As discussed in the text, the effects of R352Q cannot be confidently ascribed to open channel block and, as such, we are unable to determine the role of R352 in anion binding in the pore. Nevertheless, the finding that most other TM6 mutants were associated with altered Au(CN)2− binding suggests that multiple binding sites exist along the pore axis. This is consistent with functional evidence that the pore can be occupied by multiple anions simultaneously (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Linsdell et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2001).

In contrast to the finding that all but one mutation studied altered Au(CN)2− block, only three out of seven mutants tested significantly affected Au(CN)2− permeability (Fig. 4). The relative effect of different mutations on PAu(CN)2/PCl shown in Fig. 4B strongly suggests that the central region of TM6 (F337-S341) plays a dominant role in determining lyotropic anion selectivity, supporting our previous hypothesis of a localised selectivity region in the pore (Linsdell et al. 2000). The effects of F337S and T338A on PAu(CN)2/PCl are consistent with the disruption (F337S; Linsdell et al. 2000) and strengthening (T338A; Linsdell et al. 1998) of lyotropic anion selectivity previously described in these two mutants. However, the dramatic increase in PAu(CN)2/PCl observed in S341A (Fig. 4) suggests that the region of the pore which predominantly controls selectivity between different anions may extend further towards the intracellular end of TM6 than previously appreciated.

Figure 4. Au(CN)2− permeability of different CFTR variants.

A, example CFTR I-V relationships recorded with 150 mm KAu(CN)2 in the extracellular solution and 150 mm KCl in the intracellular solution, for wild-type, F337S and T338A. The different reversal potentials indicate different relative Au(CN)2− permeabilities (PAu(CN)2/PCl), as calculated from eqn (1) and shown in B. *Significant difference from wild-type, P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005; Student's two-tailed t test. Mean of data from 4–7 cells.

A qualitative summary of the effects of mutations of different TM6 residues on Au(CN)2− block and permeability, and a simple model of the relative positions of different TM6 residues within the pore, is shown in Fig. 5. Multiple TM6 residues contribute to anion binding, as determined by Au(CN)2− block of Cl− permeation; the dramatic weakening of Au(CN)2− block in T338A suggests a particularly strong role of this residue in binding. In contrast, only residues in the central portion (F337-S341) of TM6 contribute to anion selectivity; the disruption of lyotropic selectivity associated with mutation of F337 (Fig. 4; Linsdell et al. 2000) implies a particularly crucial role of this residue in discrimination between different permeant anions.

The salient features of the model shown in Fig. 5 are: (1) multiple residues in TM6 contribute to anion binding; (2) a more discrete group of residues are involved in anion selectivity; (3) mutation of some residues affects both binding and selectivity. Although the physical distance between different TM6 residues in the three-dimensional architecture of the pore is unknown, the fact that residues at least over the portion from K335 to I344 contribute to permeant anion binding is consistent with functional evidence that the pore can accommodate more than one anion simultaneously (Tabcharani et al. 1993; Linsdell et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 2001). Multiple residues over a similarly large part of TM12 (T1134, M1137, S1141) have previously been shown to contribute to binding of the lyotropic SCN− ion within the pore (Gupta et al. 2001).

Only mutations in the central portion of TM6 (F337S, T338A, S341A) affected both Au(CN)2− binding and Au(CN)2− permeability (Figs 3–5). These mutations, as well as substitutions of other uncharged amino acid side chains for F337 or T338, also drastically alter unitary Cl− conductance (McDonough et al. 1994; Linsdell et al. 1998; Linsdell, 2001a). Together these results implicate this central region of TM6 as the primary determinant of the anion permeation phenotype of CFTR. This region also appears to be the most physically constricted part of the pore (Linsdell et al. 1998, 2000) (see Fig. 5). Both extracellular (i.e. K335) and intracellular (i.e. I344) to this central region, mutations altered anion binding but not selectivity. We suggest that anions bind within wider vestibules on either side of the narrow pore region, but that anion binding in these vestibules has little impact on selectivity. This would explain the common finding that anion binding in CFTR is more sensitive to mutagenesis than is anion selectivity (Mansoura et al. 1998; Gupta et al. 2001). Unfortunately, we were unable to test the role of TM6 residues more intracellular than I344 on anion binding; R347 was not studied because of its association with pore stability (Cotten & Welsh, 1999), T351A was not well expressed in BHK cells and the blocking effects of Au(CN)2− on R352Q most likely do not reflect open channel block. The present study does not therefore offer any insight into the role of anion binding within the putative wide intracellular pore vestibule (Fig. 5; Linsdell & Hanrahan, 1996; Hwang & Sheppard, 1999).

The present results suggest that the TM6 region including F337, T338 and S341 is the main determinant of both lyotropic anion binding and lyotropic anion selectivity. Nevertheless, there does not seem to be a strong correlation between these two aspects of pore function, such that they may be controlled independently by the same structural features of the pore. Thus, F337S is associated with weakened Au(CN)2− binding and decreased Au(CN)2− permeability, T338A with weakened Au(CN)2− binding and increased Au(CN)2− permeability and S341A with strengthened Au(CN)2− binding and increased permeability (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The results with T338A are particularly interesting, since this mutant shows less lyotropic anion binding characteristics than wild-type (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) and yet more lyotropic anion selectivity than wild-type (Fig. 4). These findings support the view that lyotropic anion binding and lyotropic anion selectivity, in spite of their similar dependence on anion hydration energies, are not strongly interdependent parameters of pore function (Smith et al. 1999; Linsdell, 2001a).

In addition to the direct structural information obtained on TM6, which suggests that the permeation phenotype of CFTR is predominantly determined over a short, central pore region, these results confirm the value of Au(CN)2− as a probe of a Cl− channel pore. When combined with site-directed mutagenesis, Au(CN)2− can be used to identify residues involved in both anion binding and anion selectivity and taken together these results can illuminate the relationship between these aspects of pore function. This may be useful not only in the study of diverse Cl− channel types, but also in assessing the relative roles of different TM regions in controlling anion permeation in the CFTR channel pore.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CCFF). X.G. is a CCFF postdoctoral fellow. P.L. is a CCFF scholar.

REFERENCES

- Bormann J, Hamill OP, Sakmann B. Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and γ-aminobutyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1987;385:243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X-B, Kartner N, Seibert FS, Aleksandrov AA, Kloser AW, Kiser GL, Riordan JR. Heterologous expression systems for study of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Methods in Enzymology. 1998;292:616–629. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)92048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M, Akabas MH. Identification of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel-lining residues in and flanking the M6 membrane-spanning segment. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:2688–2695. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79838-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten JF, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis-associated mutations at arginine 347 alter the pore architecture of CFTR. Evidence for disruption of a salt bridge. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:5429–5435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DC, Smith SS, Mansoura MK. CFTR: mechanism of anion conduction. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79:S47–75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MA, Plant S, Argent BE. cAMP-regulated whole cell chloride currents in pancreatic duct cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264:C591–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinamard R, Akabas MH. Arg352 is a major determinant of charge selectivity in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5528–5537. doi: 10.1021/bi990155n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW, Linsdell P. Asymmetric structure of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore suggested by mutagenesis of the twelfth transmembrane region. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6620–6627. doi: 10.1021/bi002819v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm DR, Frizzell RA. Anion permeation in an apical membrane chloride channel of a secretory epithelial cell. Journal of General Physiology. 1992;99:339–366. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T-C, Sheppard DN. Molecular pharmacology of the CFTR Cl− channel. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1999;20:448–453. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P. Relationship between anion binding and anion permeability revealed by mutagenesis within the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Journal of Physiology. 2001a;531:51–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0051j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P. Thiocyanate as a probe of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2001b;79:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Evagelidis A, Hanrahan JW. Molecular determinants of anion selectivity in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:2973–2982. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76836-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Gong X. Multiple inhibitory effects of Au(CN)2− ions on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel currents. Journal of Physiology. 2002;540:29–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Hanrahan JW. Disulphonic stilbene block of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channels expressed in a mammalian cell line and its regulation by a critical pore residue. Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:687–693. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Hanrahan JW. Adenosine triphosphate-dependent asymmetry of anion permeation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:601–614. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Tabcharani JA, Hanrahan JW. Multi-ion mechanism for ion permeation and block in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:365–377. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.4.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P, Zheng S-X, Hanrahan JW. Non-pore lining amino acid side chains influence anion selectivity of the human CFTR Cl− channel expressed in mammalian cell lines. Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.001bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang ZR, Billingsley JT, McCarty NA, Dawson DC. CFTR: pH titration and chemical modification indicate that T338 (TM6) lies on the outward-facing, water-accessible surface of the protein. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2001;22(Supplement):176. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Mansoura MK, Smith SS, Choi AD, Richards NW, Strong TV, Drumm ML, Collins FS, Dawson DC. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) anion binding as a probe of the pore. Biophysical Journal. 1998;74:1320–1332. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77845-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty NA. Permeation through the CFTR chloride channel. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2000;203:1947–1962. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.13.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough S, Davidson N, Lester HA, McCarty NA. Novel pore-lining residues in CFTR that govern permeation and open-channel block. Neuron. 1994;13:623–634. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Anion permeation in Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. Journal of General Physiology. 2000;116:825–844. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychkov GY, Pusch M, Roberts ML, Jentsch TJ, Bretag AH. Permeation and block of the skeletal muscle chloride channel, ClC-1, by foreign anions. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:653–665. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Rich DP, Ostedgaard LS, Gregory RJ, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Mutations in CFTR associated with mild-disease-form Cl− channels with altered pore properties. Nature. 1993;362:160–164. doi: 10.1038/362160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Liu X, Zhang Z-R, Sun F, Kriewall TE, McCarty NA, Dawson DC. CFTR: covalent and noncovalent modification suggests a role for fixed charges in anion conduction. Journal of General Physiology. 2001;118:407–431. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Steinle ED, Meyerhoff ME, Dawson DC. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Physical basis for lyotropic anion selectivity patterns. Journal of General Physiology. 1999;114:799–818. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani JA, Linsdell P, Hanrahan JW. Halide permeation in wild-type and mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels. Journal of General Physiology. 1997;110:341–354. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani JA, Rommens JM, Hou Y-X, Chang X-B, Tsui L-C, Riordan JR, Hanrahan JW. Multi-ion pore behaviour in the CFTR chloride channel. Nature. 1993;366:79–82. doi: 10.1038/366079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z-R, Zeltwanger S, McCarty NA. Direct comparison of NPPB and DPC as probes of CFTR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 2000;175:35–52. doi: 10.1007/s002320001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Hu S, Hwang T-C. Voltage-dependent flickery block of an open cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel pore. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:435–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0435f.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]