Abstract

To investigate the ionic mechanisms controlling the dendrosomatic propagation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (LTS) in Purkinje cells (PCs), somatically evoked discharges of action potentials (APs) were recorded under current-clamp conditions. The whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp method was used in PCs from rat cerebellar slice cultures. Full blockade of the P/Q-type Ca2+ current revealed slow but transient depolarizations associated with bursts of fast Na+ APs. These can occur as a single isolated event at the onset of current injection, or repetitively (i.e. a slow complex burst). The initial transient depolarization was identified as an LTS Blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels increased the likelihood of recording Ca2+ spikes at the soma by promoting dendrosomatic propagation. Slow rhythmic depolarizations shared several properties with the LTS (kinetics, activation/inactivation, calcium dependency and dendritic origin), suggesting that they correspond to repetitively activated dendritic LTS, which reach the soma when P/Q channels are blocked. Somatic LTS and slow complex burst activity were also induced by K+ channel blockers such as TEA (2.5 × 10−4m) charybdotoxin (CTX, 10−5m), rIberiotoxin (10−7m), and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 10−3m), but not by apamin (10−4m). In the presence of 4-AP, slow complex burst activity occurred even at hyperpolarized potentials (−80 mV). In conclusion, we suggest that the propagation of dendritic LTS is controlled directly by 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels, and indirectly modulated by activation of calcium-activated K+ (BK) channels via P/Q-mediated Ca2+ entry. The slow complex burst resembles strikingly the complex spike elicited by climbing fibre stimulation, and we therefore propose, as a hypothesis, that dendrosomatic propagation of the LTS could underlie the complex spike.

A fundamental aspect of neuronal integration concerns the electrical properties underlying dendrosomatic communication. Many distinct types of voltage-gated ion channels are present on dendritic and somatic membranes (Johnston et al. 1996). Depending upon their biophysical properties and localization, somatic and dendritic channels can modulate differentially the temporal and spatial summation of synaptic events and their ability to trigger fast APs at the axon hillock (Yuste & Tank, 1996; Stuart et al. 1997). In many neurones under physiological conditions, fast Na+ action potentials (APs) can not be initiated or fully actively propagated back through the dendritic tree because of low Na+ channel density (Stuart & Hausser, 1994) or high K+ channel density (Hoffman et al. 1997; Colbert & Pan, 1999) in the dendrites. In contrast, Ca2+ APs are typically initiated in the dendrites (see Yuste & Tank, 1996). In many cases, the propagation of Ca2+ spikes is restricted to the dendrites, with Ca2+ spikes rarely observed in somatic recordings (see Schiller et al. 1997; Golding et al. 1999).

In hippocampal neurones, the densities of somatic and dendritic Ca2+ channels are comparable (Magee & Johnston, 1995), but strong activation of K+ channels in the soma restricts the Ca2+ spike to the dendrite (Golding et al. 1999). In cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs), the somatic density of Ca2+ channels is too low to allow the generation of Ca2+ spikes (Usowicz et al. 1992). Nevertheless, considering the robust Ca2+ spike observed in the PC dendrites (Llinás & Sugimori, 1980b), one would expect to record an attenuated Ca2+ spike at the somatic level, even in the absence of somatic Ca2+ channels. In fact, somatic Ca2+ spikes have been observed, but only after large current injections (Llinás & Sugimori, 1980a, b; Tank et al. 1988). It has been shown that PCs fire exclusively fast Na+ spikes in response to small current injections, whereas for higher current injections, dendritic Ca2+ spikes are generated that induce bursts of spikes in the soma (Llinás & Sugimori, 1980a). The nature of the Ca2+ channels that are responsible for the generation of dendritic Ca2+ spikes, P/Q type (Llinás et al. 1992) or low-threshold type (Pouille et al. 2000), is still under debate. Active models of PCs incorporating either a dominant contribution of P/Q channels (De Schutter & Bower, 1994a) or low-threshold Ca2+ channels (Miyasho et al. 2001) reproduce both types of spiking behaviour.

Why are strong depolarizations required for somatic Ca2+ spikes to be observed? First, the current injected into the soma attenuates along the dendrite, and strong current injections are necessary to depolarize the dendrite to the threshold for calcium-spike initiation. Second, strong current injections are needed to overcome an intrinsic block of dendrosomatic propagation of Ca2+ spikes. Evidence for this dendritic blocking phenomenon has been obtained in rat PCs recorded in slice cultures (Pouille et al. 2000). In this preparation, low-threshold Ca2+ spikes could be evoked in the dendrites, but were rarely observed in the soma. The aim of the present study was to analyse the ionic mechanisms that control the propagation of the dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spike to the soma.

Among the ionic channels that are expressed with a high density in the dendrites of PCs, we investigated the role of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. These channels can impair the genesis and the dendrosomatic propagation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes either by producing a sustained depolarization of dendrites, thereby inactivating low-threshold Ca2+ channels (Zhan et al. 2000), or by activating calcium-dependent K+ conductances. We also examined the role of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive K+ channels, which may control the dendrosomatic propagation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes in PCs through mechanisms similar to those controlling the back-propagation of fast Na+ spikes in the dendrite (Hoffman et al. 1997) or propagation in the axon (Debanne et al. 1997) in hippocampal pyramidal neurones. Previous observations in PCs indicate that 4-AP-sensitive K+ conductances regulate the amplitude of dendritic Ca2+ spikes (Etzion & Grossman, 1998) and of dendritic Ca2+ transients sensitive to nickel (Watanabe et al. 1998), and influence the compartmentalization of Ca2+ spikes in the dendrites (Midtgaard et al. 1993).

METHODS

Preparation of cerebellar slice cultures

Organotypic cerebellar slice cultures were prepared from rats using the roller tube technique, as described by Gähwiler (1981). Cerebella were removed under aseptic conditions from 0- to1-day-old rats that had been killed by decapitation in accordance with the French guidelines. Parasagittal 425 μm thick slices were cut using a McIlwain tissue chopper. Individual slices were attached to glass coverslips in a film of clotted chicken plasma (Cocalico, Reamstown, PA, USA) and placed into culture tubes containing 750 μl of culture medium composed of 25 % heat-inactivated horse serum, 50 % Eagle's basal medium, 25 % Hank's balanced salt solution containing 33.3 mm d-glucose and 0.1 mm glutamine. The tubes were placed into a roller drum inside an incubator at 36 °C. The culture medium was partly changed once a week. Electrophysiological recordings were performed after a period of at least 3 weeks in culture.

Preparation of acute cerebellar slices

Standard procedures were used to prepare 200 μm thick cerebellar slices from 21-day-old Wistar rats after injection of 200 μl of an anaesthetic solution containing ketamine (64 mg ml−1) + xylazine (16 mg ml−1). After dissection, the slices were maintained at room temperature for at least 1 h before recording in a submerged chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid equilibrated with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2. The artificial cerebrospinal fluid contained (in mm): NaCl 119, KCl 2.5, NaHPO4 1, MgCl2 1.3, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 26, glucose 11. The pH was adjusted to 7.4.

Electrophysiology

Recordings from slice cultures

Cerebellar slice cultures were transferred to a recording chamber fixed onto the stage of a Nikon Optiphot2 microscope (Tokyo, Japan). Patch-clamp recordings were carried out under current-clamp conditions in the whole-cell recording (WCR) configuration using an Axopatch 200 A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). PCs were visualized on a monitor screen using an infrared camera (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Planegg, Germany) and identified by their typical morphology and by their localization in the periphery of the slice culture.

For the patch-clamp experiments, pipettes of 5 MΩ were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (Clark electromedical instruments, Pangbourne, UK) with a horizontal micropipette puller (BB-CH-PC, Mecanex, Geneva, Switzerland), coated with sylgard (Rhône Poulenc, Saint-Fons, France) and filled with a solution containing (in mm): potassium gluconate 132, EGTA/KOH 1, MgCl2 2, NaCl 2, Hepes/KOH 10, MgATP 2 and NaGTP 0.5. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-OH. Gigaohm seals between the pipette and the cell were obtained and capacitance transients were minimized to 0–25 pA.

The cultures were perfused at room temperature with a bath solution containing (in mm): NaCl 130, KCl 2, CaCl2 2.8, MgCl2 2, Hepes/Tris 10, glucose 5.6. 6-Cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) and bicuculline were added to the external solution at 10−5m to abolish excitatory and inhibitory synaptic activity. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with Tris-OH.

To block the P/Q-type Ca2+ current completely, some slices were incubated prior to electrophysiological recording in an external solution containing ω-conotoxin-MVIIC (5 × 10−6m) or ω-agatoxin TK (2 × 10−7m) for 15–20 min.

After going into the WCR configuration the membrane potential was maintained at −80 mV from a resting value of about −45 mV by injection of a steady-state current (300–650 pA) to remove inactivation of the low-threshold Ca2+ current. A custom-built stimulator was used for current injections. The resulting voltage traces were digitized at 47.2 kHz using a digital data recorder (VR-10B, Instrutech, Great Neck, NY, USA) before storage on a Panasonic video recorder (Matsushita Electric Industrial, Osaka, Japan). Off-line analysis was performed using Pclamp 6 software (Axon Instruments).

In some experiments, cells were superfused locally by applying positive pressure to a second electrode containing 330 mm saccharose and 10 mm fast green (to ensure under visual control that saccharose ejection was restricted to the soma or dendrite). Fast green by itself had no effect on neuronal responses.

Recordings from acute slices

Acute slices were transferred to a recording chamber that was fixed onto the stage of a Zeiss microscope (Axiovert 135, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and continuously perfused at room temperature with artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing CNQX (10−5m) and bicuculline (10−5m). PCs were visualized on a monitor screen using an infrared camera (T.I.L.L. Photonics) and identified by their typical morphology.

WCR electrodes (2–5 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (in mm): potassium gluconate 132, EGTA/KOH 1, MgCl2 2, NaCl 2, Hepes/KOH 10, MgATP 2 and GTP 0.5. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-OH. Current-clamp recordings were obtained with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Current injections were performed using a digital stimulator (PG 4000; Neuro Data Instruments, New York, USA). The resulting voltage signals were digitized on-line with a DIGIDATA 1200 interface (Axon Instruments) for off-line analysis using the pCLAMP 8 software.

Chemicals

Bicuculline methiodide, TTX, 4-AP and TEA (Sigma, St Louis, USA) were prepared as 10−2m, 5 × 10−5m, 0.1 m and 2 × 10−2m stock solutions in distilled water, respectively, and CNQX (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK) as a 10−2m stock solution in DMSO. ω-Conotoxin-MVIIC (Latoxan, Rosans, France), ω-agatoxin TK, apamin, dendrotoxin (α-DTX or DTX-k) and rIberiotoxin (Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel) were prepared as 10−4m, 2 × 10−5m, 5 × 10−4m, 2 × 10−4m and 10−5m stock solutions in distilled water, respectively. Charybdotoxin (CTX; Alomone) was prepared as a 10−5m stock solution in NaCl 100 mm, Tris-OH 10 mm, EDTA/NaOH 1 mm, and 0.1 % bovine serum albumin. Stock solutions were stored at −20 °C for 2 weeks. All drugs were diluted to their final concentration immediately before use.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the PC evoked response after blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

In our previous study (Pouille et al. 2000), we demonstrated that Ca2+ entry via P/Q-type Ca2+ channels activates hyperpolarizing conductances that allow PCs to repetitively fire fast Na+ APs. Following perfusion with an external solution containing toxins that block P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (ω-conotoxin-MVIIC or ω-agatoxin TK), low-frequency bursts of APs associated with small oscillations in membrane potential could be observed (see Fig. 10B in Pouille et al. 2000). This pattern of discharge also sometimes occurred during application of Cd2+ (see Fig. 10A in Pouille et al. 2000). We proposed that the appearance of these oscillations was related to dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes, which were now able to invade the soma because of P/Q Ca2+ channel blockade.

To analyse the effect of P/Q channel blockade in more detail, we compared evoked discharge in PCs (recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV) under control conditions (see Pouille et al. 2000) with the discharge obtained after full blockade of P/Q channels by preincubating the slices with ω-conotoxin-MVIIC (5 × 10−6m, n = 20) or with ω-agatoxin TK (2 × 10−7m, n = 60) for at least 15 min. After toxin treatment, only 11 out of 80 cells exhibited high-frequency firing of Na+ APs (60–80 Hz), confirming that P/Q-type Ca2+ channels are important for repetitive firing of fast Na+ APs (see Pouille et al. 2000). Interestingly, in 63 pretreated cells (Fig. 1A, B) the response to current injection started with a transient but slow depolarization (amplitude (A) 22 ± 7 mV and a duration measured at A/2 of 20 ± 12 ms) that triggered 1–3 fast APs (see the red trace in the inset in A). In 28 cells, this initial response was followed by a sustained plateau of depolarization (Fig. 1A) with, in 6 cases, oscillations of the membrane potential that triggered an irregular discharge of fast APs (not illustrated). In many cases (Fig. 1B, n = 35), this initial event was followed by transient but slow depolarizations (A = 25 ± 10 mV and a duration measured at A/2 of 45 ± 13 ms) that elicited bursts of fast APs (Fig. 1C). We designated the motif comprising a transient depolarization associated with fast APs a ‘slow complex burst’ (Fig. 1C). Each slow complex burst was followed by a slow hyperpolarization. The frequency of slow complex bursts increased with the intensity of the depolarizing current, reaching a maximal value of about 10–15 Hz (Fig. 1D). In the six remaining cells, the response started with a fast Na+ AP followed by a depolarizing plateau, which displayed only small oscillations in membrane potential inducing, in three cells, an irregular low-frequency discharge of fast APs (not illustrated).

Figure 1. Somatically evoked responses recorded after the blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels reveal slow but transient depolarizations.

A-C, responses to current injections recorded after preincubation with toxins that block P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. A, an initial transient depolarization (shown on an expanded time scale in the inset, with an amplitude and duration as indicated by arrows) triggering a fast action potential (AP). This initial response is followed by a depolarizing plateau. B, an initial slow, transient depolarization triggering a fast AP, which is followed by slow depolarizing waves, each of which elicited fast APs. C, a slow complex burst with amplitude and duration as indicated by arrows. D, frequency of slow complex bursts (typified in C) as a function of injected current intensity. E, time course of the effects on the evoked discharge of a drop of ω-agatoxin TK (2 × 10−7m) applied close to the recorded cell. F, effects on the evoked discharge of Cd2+ (5 × 10−5m). In both cases, the left traces are the control responses (regular firing of fast APs) and the middle traces are the responses after the application of either toxin or Cd2+ (a firing of slow complex bursts is induced as shown by the third traces on an expanded time scale). The right panel illustrates the initial response under control conditions (thin trace) and after toxin and Cd2+ application (red thick trace). Note the appearance of an initial slow but transient depolarization in the presence of toxin or Cd2+.

In conclusion, our results using the P/Q channel blocker preincubation protocol confirmed that (1) P/Q channels are essential for eliciting firing of repetitive fast Na+ APs at high frequency and (2) slow complex bursts can be revealed in the absence of P/Q channel activity. Furthermore, these experiments showed that blocking P/Q channels in PCs evoked responses that frequently started with an initial transient depolarization resembling a dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spike (see below).

The next series of experiments was designed to verify whether blockade of P/Q channels in PCs with toxins or Cd2+ could switch the evoked responses from a fast spiking mode to a slow complex bursting mode beginning with an initial transient depolarization. Only when toxin was applied close to the recorded cell (Fig. 1E, n = 3 out of 6) did we observe an initial transient depolarization (see left panel, red trace) followed by slow complex bursts (illustrated on an expanded time scale, third trace). After bath application of Cd2+ (at 5 × 10−5m), as described in Pouille et al. (2000), the cell depolarized rapidly and the repetitive firing of fast sodium-dependent APs was suppressed. When the intensity of injected current was decreased during application of Cd2+, an initial transient depolarization (amplitude 20 ± 8 mV, duration 18 ± 11 ms, see left panel red trace) was revealed in some cells, followed by slow complex bursts (amplitude 20 ± 10 mV, duration 21 ± 12 ms; also illustrated on an expanded time scale, third trace; Fig. 1F, n = 9 out of 17).

After blockade of P/Q channels, the initial transient depolarization was not systematically associated with firing of slow complex bursts, consequently these two components were analysed separately.

The initial transient depolarization is a low-threshold Ca2+ spike

In the next series of experiments we determined the properties of the initial somatic transient depolarization, which was observed in 78 % of the PCs after preincubation with toxin. First, the ionic basis of this initial transient depolarization recorded from the soma was determined (Fig. 2A). When TTX (5 × 10−6m) was added, fast APs were blocked and the initial transient depolarization was recorded in isolation (first panel from top, n = 6). Replacing external Na+ with Tris-HCl did not affect the response (second panel from top, n = 2). However, the initial transient depolarization was abolished by the removal of external Ca2+ (third panel from top, n = 5). Figure 2B illustrates the activation properties of the initial transient depolarization isolated in the presence of TTX. Increasing the current intensity revealed the all-or-none nature of this event. From these observations we conclude that the initial slow transient depolarization is a calcium-dependent AP. It was triggered at a membrane potential of −48 ± 6 mV (see arrow in Fig. 2B, n = 9). Consequently, this AP is considered to be a low-threshold Ca2+ spike, which inactivated when the holding potential was fixed between −80 and −20 mV (n = 3, not illustrated). Thus, the Ca2+ spike recorded from the soma after blockade of P/Q Ca2+ channels has the same properties as the low-threshold Ca2+ spike identified in PC dendrites (Pouille et al. 2000). Whereas low-threshold Ca2+ spikes were only occasionally detected (about 15 % of cases) in somatic recordings under control conditions, they were frequently present (78 % of cases) after blockade of P/Q channels.

Figure 2. The initial transient depolarization recorded in the soma after blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels is a Ca2+ AP with a low activation threshold.

A, in all cases the time scale is shown between 200 and 500 ms to illustrate the initial response. The initial transient depolarization is insensitive to TTX (first panel from top). The left trace is the control response and the right trace is the response after TTX (5 × 10−7m). The initial transient depolarization is not sodium-dependent (second panel from top). The left trace shows the evoked response recorded in the presence of TTX and the right trace the response after perfusion of a sodium-free external solution. The initial transient slow depolarization is calcium-dependent (third panel from top). The left trace shows the initial transient depolarization isolated in the presence of TTX, and the right trace the response after perfusion with a calcium-free solution. B, activation of the calcium-dependent initial response isolated in the presence of TTX. Responses evoked with current injections of increasing intensity are shown. The threshold potential for the transient depolarization is indicated by the arrow: during the current injection the cell first depolarized, following an exponential time course (thick line) until (arrow) the slow AP was evoked. C, the probability of recording a Ca2+ spike depends upon the recording site. Histogram of the percentage of recordings displaying a Ca2+ spike as a function of the distance along the dendrite under control conditions (black bars) and after preincubation with ω-agatoxin TK or ω-conotoxin MVII C to block P/Q channels (white bars).

Which mechanisms could contribute to the increased occurrence of somatic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes after blockade of P/Q Ca2+ channels? Two likely possibilities are that when P/Q channels are blocked, (1) the low-threshold Ca2+ spike can be initiated in the soma or (2) the dendrosomatic propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike is facilitated. First, we determined whether the dendritic occurrence of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes was modified after P/Q channel blockade. We compared the proportion of recordings displaying an evoked low-threshold Ca2+ spike as a function of distance of the recording site from the soma (Fig. 2C) under control conditions (black histograms, taken from Fig. 6C, Pouille et al. 2000) and after preincubation with toxin (open histograms). In the presence of toxins, the Ca2+ spike was recorded with a higher probability in the soma and in the proximal dendrites at a distance of 10–25 μm from the somata, where we suggest that a P/Q-channel-dependent inhibition of propagation occurred. For greater distances from the soma, the occurrence of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes was similar in control conditions and after the blockade of P/Q channels. These observations suggest that P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activity controls the dendrosomatic propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike.

Figure 6. Effects of apamin and 4-AP on evoked responses recorded after the blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

To reveal slow complex burst firing, cultured slices were preincubated with ω-agatoxin-TK for at least 15 min to block P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. A, effects of apamin. The left trace is the control response; the middle trace and the right trace represent the response 50 s and 75 s after apamin treatment, respectively. Note that the repetitive slow complex bursts were abolished by apamin after 75 s. The left panel illustrates the control response on an expanded time scale (thin black trace) and the response during application of apamin (thick red trace), to show that apamin reduced the slow hyperpolarization that followed the slow complex burst. B, C, effects of 4-AP (10−3m). B, the left trace is the control response (only an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike was evoked) and the middle trace and the right trace are responses 35 s and 45 s after 4-AP treatment, respectively. The right panel illustrates the control response on an expanded time scale (black thin trace) and the response during application of 4-AP (red thick trace). Note the appearance of a discharge of slow complex bursts. C, the left trace is the control response (a discharge of slow complex bursts), the middle trace is the response after bath application of TTX (5 × 10−7m; only an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike is evoked), and the right trace is the response after a bath application of 4-AP (10−3m) in the presence of TTX (a discharge of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes was induced).

To see directly whether P/Q channel activity could change the initiation site of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike, we tried to localize this site under control conditions and after blockade of P/Q channels. We first compared somatically evoked discharge after electrical isolation of the PC soma or dendrite by local perfusion of saccharose (see Gottmann & Lux, 1990). In the region of saccharose application, external ions were displaced, transforming this site into a non-excitable element. Somatic, and to a lesser extent dendritic, application of saccharose depolarized the cell. To compare evoked responses before and after saccharose application, hyperpolarizing current was therefore injected to maintain a membrane potential around −80 mV during saccharose applications. Under control conditions, when the discharge of PCs was characterized by a sustained discharge of fast APs, the superfusion of saccharose onto the soma (Fig. 3A, n = 7) induced a rapid suppression (1–2 s) of repetitive discharge with a disappearance of the first fast AP (n = 1), which probably occurred when the saccharose reached the axon-hillock. When saccharose was superfused onto the dendrite, only a decrease in the duration of discharge was observed (Fig. 3B, n = 6). Both effects were similar to that produced by Ca2+ removal (see Pouille et al. 2000). Indeed, when the saccharose reached the soma or the dendrite, the response stabilized at a more depolarized potential, concomitant with the suppression of discharge. From these observations we propose that superfusion of the soma with saccharose suppressed directly the calcium-dependent hyperpolarizing conductance required for maintaining repetitive firing. Superfusion of dendrites with saccharose abolished most but not all Ca2+ entry, leading to the activation of the calcium-dependent hyperpolarizing conductance. Indeed, fluorimetric measurements reveal that a brief depolarizing pulse induces an increase in Ca2+ concentration in a somatic submembrane shell (Eilers et al. 1995). This somatic Ca2+ increase, which is probably due to a distant dendritic Ca2+ entry that is amplified by calcium-induced Ca2+ release from internal stores (Llano et al. 1994), could activate a calcium-dependent hyperpolarizing conductance over a long physical distance.

Figure 3. Comparison of the effect of saccharose application on the soma and on the main dendrite reveals a dendritic initiation site for the low-threshold Ca2+ spike with or without functional P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

To the left of the figure are schematic diagrams of the protocol indicating that the recording pipette was on the soma and a second pipette was used to apply saccharose (dashed lines) onto either the soma (second drawing from top) or the main dendrite (fourth drawing from top). A and B, recordings from the same cell illustrating, under control conditions, sustained discharge of fast APs (see the traces on top) in response to a depolarizing current injection. The lower traces in A and B illustrate the response after application of saccharose onto the soma and onto the dendrite, respectively. The repetitive response of fast APs was either totally or partially abolished following the somatic or dendritic location of the saccharose application. C and D, recordings from another cell. Under control conditions, the evoked response was an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike with one fast AP on top (see the traces on top). The lower traces in C and D illustrate the response after application of saccharose onto the soma and onto the dendrite, respectively. The low-threshold Ca2+ spike was affected only when saccharose was applied onto the main dendrite. E and F, the same cell recorded after incubation with a toxin that blocks P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. The top traces in E and F illustrate the control responses to a depolarizing current injection (an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike with a fast AP on top). The lower traces in E and F illustrate the response after application of saccharose onto the soma and onto the dendrite, respectively. Again, the initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike was only affected when saccharose was perfused onto the dendrite.

Under control conditions, when the evoked discharge started with a low-threshold Ca2+ spike associated with a fast AP (9 % of cases), somatic application of saccharose did not affect the low-threshold Ca2+ spike (Fig. 3C, n = 2), whereas the Na+ spike was suppressed. However, as illustrated in Fig. 3D, when the dendritic region was superfused with saccharose the low-threshold Ca2+ spike was diminished or suppressed (n = 2), but the fast Na+ spike was not affected. These experiments demonstrate directly that under control conditions, low-threshold Ca2+ spikes are initiated in the dendrite. After incubation with toxins that block P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, low-threshold Ca2+ spikes are initiated in the dendrite. Low-threshold Ca2+ spike amplitude was not affected by application of saccharose onto the soma (Fig. 3E, n = 3 out of 3), but low-threshold Ca2+ spikes were abolished (n = 2) or diminished by 63 % when dendritic regions were superfused with the saccharose solution (Fig. 3F). In conclusion, the consequence of P/Q channel blockade is to promote the dendrosomatic propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike, without modifying the site of initiation.

Activation-inactivation properties and ionic dependency of the slow complex bursts

The activation-inactivation properties of the somatic slow complex bursting activity revealed after blockade of P/Q Ca2+ channel were examined (Fig. 4A) by injecting steady-state current of various intensities to maintain the membrane potential at hyperpolarized or depolarized levels. Slow bursts were elicited at a membrane potential of −47 ± 3 mV (n = 5) and appeared either as isolated events at a regular frequency (Fig. 4A, left panel) or as grouped events on top of depolarizing plateaus (not shown). Depolarizing the membrane beyond the threshold potential increased the frequency of slow complex bursts but decreased their amplitude (Fig. 4A, left panel, n = 5), indicating a voltage-dependent inactivation process. We determined the voltage sensitivity of inactivation of the slow component of the burst (Fig. 4A, right panel) by measuring its amplitude (as indicated by the inset) as a function of membrane potential. The amplitude of the slow component decreased with depolarization and was completely inactivated at −25 ± 3 mV (n = 5).

Figure 4. Activation-inactivation properties and ionic dependence of the slow complex burst discharge recorded after preincubation with toxins against P/Q channels.

A, complex burst firing recorded at different holding potentials (left panel) and the amplitude of the slow depolarizing wave (measured as indicated in the inset) as a function of the holding potential (right panel). B, ionic dependence of the slow complex burst discharge. The upper traces illustrate control responses. The lower trace on the left is obtained after perfusion with calcium-free external solution. Only a fast AP is elicited at the onset of the step. The lower trace in the middle represents the response obtained after bath application of TTX (5 × 10−7m): in this condition only a slow AP was triggered at the beginning of the step. The lower trace on the right shows the response recorded in sodium-free external solution, where only a slow AP is elicited at the beginning of the step. C, Somatic and dendritic conductances were required for a repetitive activation of the slow complex bursts revealed after the blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. The control response (protocol illustrated by the first drawing) recorded after incubation with ω-agatoxin-TK was a slow complex burst (upper trace on the left) and is shown on an expanded time scale (lower trace). The middle and right traces illustrate the responses after perfusion of saccharose onto the soma and onto the dendrite, respectively. The lower traces illustrate these responses on an expanded time scale. Saccharose applied onto the soma abolished repetitive firing, and saccharose applied onto the main dendrite after recovery to the control response (not shown) only blocked slow spikes.

In the next series of experiments, the ionic basis of slow complex bursts was investigated. Slow complex bursts were calcium-dependent, as they were abolished by removal of external Ca2+ (Fig. 4B, left panel, n = 5). Only a fast AP could be elicited at the onset of the step. Bath application of TTX prevented the discharge of slow complex bursts (middle panel of Fig. 4B, n = 9). After TTX application, a slow AP, which corresponded to the dendritic-initiated low-threshold Ca2+ spike (n = 6 out of 9), was isolated at the beginning of the step. The effects of TTX were mimicked by the removal of external Na+ (Fig. 4B, right panel, n = 2). In conclusion, the generation of slow complex bursts depends upon calcium- and TTX-sensitive Na+ conductances.

According to the hypothesis proposed by Llinás & Sugimori (1980a,b), Ca2+ conductances in PCs are of dendritic origin, whereas Na+ conductances are somatic. Thus, saccharose application onto the dendrite and onto the soma should affect the slow complex bursts recorded after blockade of P/Q channels. As illustrated in Fig. 4C, saccharose application onto the soma completely abolished slow complex bursting activity (n = 3), whereas dendritic application transformed slow complex bursting activity into a regular discharge pattern of fast APs (n = 6). In the latter case only the slow component of the slow complex burst was abolished.

From these observations, we suggest that slow complex burst firing is due to the repetitive activation of dendritically initiated low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (corresponding to the slow component of the slow complex burst), triggering a burst of fast APs when blockade of P/Q channel activity allows their propagation to the soma. This repetitive activation of the low-threshold spike requires a concomitant activation of a somatic conductance, probably the TTX-sensitive, persistent Na+ conductance (Llinás & Sugimori, 1980a).

Low-threshold Ca2+ spikes and complex responses can be recorded in the soma after chelating internal Ca2+ or after blocking calcium-dependent K+ channels

Among the different mechanisms that could explain the effect of P/Q channel activity on dendrosomatic propagation of the Ca2+ spike, we decided to test whether Ca2+ entry via P/Q channels could activate co-localized calcium-dependent K+ channels. The resulting hyperpolarization and decrease in membrane resistance would be expected to hinder propagation of the dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spike to the soma. If this mechanism is of importance, application of an internal Ca2+ chelator should reproduce the effects of P/Q channel blockade. This was indeed the case in some PCs in which external application of BAPTA-AM transformed the firing pattern of fast APs evoked under control conditions into a discharge of complex responses with an amplitude and duration of 12 ± 5 mV and 19 ± 8 ms, respectively (n = 3 out of 12; not illustrated). A low-threshold Ca2+ spike (amplitude 15 ± 5 mV, duration 15 ± 9 ms) sometimes also appeared with perfusion of BAPTA-AM (not illustrated). In other cases, as reported in Pouille et al. (2000), BAPTA-AM perfusion only suppressed the repetitive discharge of fast APs.

To identify the family of calcium-dependent K+ channels blocking Ca2+ spike propagation, we used specific blockers and analysed their effects on evoked discharge. The K+ channel blocker TEA (bath applied at 2 × 10−4 and 2.5 × 10−4m; n = 8 out of 9) and the BK channel blocker CTX (bath applied at 10−5m; n = 8 out of 11) induced bursting activity. Examination of the TEA-induced (Fig. 5A, n = 4) or CTX-induced (Fig. 5B, n = 4) bursting activity showed the appearance in some cases of an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike (amplitude 19 ± 9 mV, duration 15 ± 9 ms) and slow complex bursts (amplitude 20 ± 5 mV, duration 19 ± 9 ms; lower panel in A for TEA, n = 3 and lower panel in B for CTX, n = 3). In other cases only fast APs were detected in the burst. Furthermore, when slices were incubated with rIberiotoxin (10−7mCandia et al. 1992), an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike and slow complex bursting activity were recorded in six out of seven PCs (data not shown).

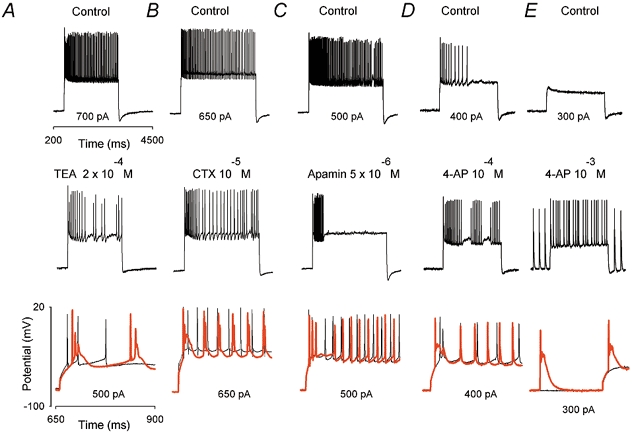

Figure 5. Effects of K+ channels blockers on the firing of fast APs: BK channel blockers and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), but not apamin, induced firing of slow complex bursts and the appearance of an initial Ca2+ spike.

A-E, effects of TEA (2 × 10−4m), charybdotoxin (CTX; 10−5m), apamin (10−4m), 4-AP (10−4m) and 4-AP (10−3m) on the evoked discharge, respectively. Upper traces are control responses and middle traces are responses recorded after bath application of K+ channel blockers. The lower traces illustrate the initial response on an expanded time scale under control conditions (thin trace) and after the application of a K+ channel blocker (red thick trace). TEA and CTX induced the appearance of an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike and slow complex burst. Apamin reduced the duration of fast AP discharge. 4-AP applied at 10−4m induced an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike followed by fast APs, whereas application of 4-AP at 10−3m induced slow complex bursts, even at −80 mV.

As expected for BK channel blockade, the application of TEA or CTX decreased the fast after-hyperpolarization that followed each fast AP (52 ± 18 %, n = 8). The duration of the first fast AP measured in four cells in the presence of TEA and in eight cells in the presence of CTX increased slightly (by 14 ± 6 % and by 7 ± 3 %, respectively). However, no consistent change in input resistance was observed with TEA and CTX. This action was specific for this family of calcium-dependent K+ channels. Indeed, apamin (bath applied at 5 × 10−6m, n = 6), a specific blocker of some SK channels (Coetzee et al. 1999), never induced slow complex bursting activity or an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike. However, as illustrated in Fig. 5C (n = 4 out of 6), apamin reduced the duration of discharge, as was observed previously when Ca2+ was removed from the external solution. When P/Q channels were blocked, apamin increased the frequency of slow complex burst firing (Fig. 6A, second trace from the left), which was associated with a decreased duration of the slow hyperpolarization following each slow complex burst (Fig. 6A, right panel, compare the black trace (control) and the red trace (during apamin). After longer applications, apamin abolished slow complex bursts (Fig. 6A, third trace from the left).

In conclusion, these results are consistent with the activation of BK channels after P/Q-channel-mediated Ca2+ entry, which controls dendrosomatic propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike. Apamin-sensitive SK channels contribute to the calcium-dependent hyperpolarization required for repetitive firing of fast APs and to the slow hyperpolarization observed after each slow complex burst under conditions when dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes propagate to the soma.

4-AP-sensitive K+ channels and electrogenesis of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike

In hippocampal pyramidal cells, low-threshold 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels are known to control the back-propagation of fast APs in the dendrite (Hoffman et al. 1997). To determine whether in PCs such channels could also affect the electrogenesis of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (i.e. their repetitive activation and their propagation to the soma), the effects of bath-applied 4-AP on somatic evoked discharge were characterized. As illustrated in Fig. 5D, bath-applied 4-AP at 10−4m (n = 6) induced an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike with an amplitude of 27 ± 10 mV and a duration of 29 ± 9 ms (black and red traces, lower panel), and fast AP bursting activity (see the middle trace). By increasing the 4-AP concentration to 10−3m (see Fig. 5E, n = 5) the bursting activity of fast APs converted to slow complex responses (amplitude 18 ± 9 mV, duration 26 ± 9 ms). Surprisingly, slow complex responses were also observed at hyperpolarized potentials (−80 mV; the black trace illustrates the control response and the red trace the response after 10−3m 4-AP in the lower panel).

These results demonstrate that 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels control the electrogenesis of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes. Furthermore, after blockade of P/Q channels, bath-applied 4-AP at 10−3m induced slow complex bursts when the control response was an initial low-threshold spike (Fig. 6B, n = 4), and restored the repetitive activation of low-threshold spikes if these were previously blocked by TTX (Fig. 6C, n = 4 out of 8). In contrast, DTXs specific for the Kv1 family of K+ channels such as α-DTX (n = 3) and DTX-k (n = 3; bath applied at 2 × 10−6m) did not affect the discharge patterns recorded under control conditions (data not shown).

Spontaneous firing pattern: simple spikes and slow complex bursts

A proportion of the PCs (n = 68 out of 302) fired APs spontaneously at the resting membrane potential (around −48 mV). This activity consisted mainly of fast APs at a mean frequency of 5.2 ± 0.6 Hz (Fig. 7A, n = 41), but slow complex bursts at a mean frequency of 2.5 ± 0.3 Hz were also sometimes observed (Fig. 7B, n = 22). The slow component of the slow complex bursts had an amplitude of 24 ± 5 mV and a duration of 70 ± 29 ms. In a few cases (n = 5), simple spikes and slow complex bursts were combined as APs riding on depolarizing plateaus (Fig. 7C). These observations indicate that even during control conditions, some PCs display spontaneous electrical activity similar to that observed after blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, BK channels or 4-AP-sensitive channels.

Figure 7. Spontaneous activity of Purkinje cells (PCs): simple spikes and slow complex bursts.

Spontaneous activity of PCs recorded at the resting membrane potential. A, sustained regular discharge of fast APs is recorded. B, regular discharge of slow complex bursts. C, simple spikes and slow complex bursts evoked on depolarizing plateaus.

Comparison with PCs recorded in acute slices

The last series of experiments was carried out to determine whether the mechanisms that control the electrical activity in PCs recorded in slice cultures are also of importance in PCs recorded in acute slices. First, are initial low-threshold Ca2+ spikes present under physiological conditions? Second, can the firing of fast APs be transformed into slow complex burst firing after blockade of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels or BK channels?

Recordings were obtained from 15 PCs, and as described for PCs in slice cultures (Pouille et al. 2000), three modes of discharge were observed (mode 1 n = 8; mode 2 n = 4 and mode 3 n = 3). Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 8A (black trace), in some PCs (n = 4) the firing induced by depolarizing current injections started with a small transient depolarization that triggered a short burst of fast APs. In the presence of TTX, this initial transient depolarization could be isolated (see the red trace), suggesting that it corresponded to the low-threshold Ca2+ spike recorded from PCs in slice cultures (see also Crepel & Penit-Soria, 1986).

Figure 8. Evoked responses of PCs recorded from acute slices. Co-application of TEA and Cd2+ induced firing of slow complex bursts.

A, evidence for an initial slow depolarization that is insensitive to TTX. The evoked response to current injection is illustrated on an expanded time scale to show the initial part of the response. The thin black trace illustrates an initial slow depolarization triggering a burst of fast APs, and the red thick trace shows the response after TTX, where an initial slow transient depolarization was isolated. B, D, effects of TEA (2.5 × 10−4m) and Cd2+ (5 × 10−5m) on the evoked discharge. B, the left trace is the control response (sustained firing of fast APs), the middle trace is the response after TEA (burst of fast APs), and the right trace shows the response when Cd2+ was applied in the presence of TEA, revealing slow complex bursts. C, the initial response under control conditions on an expanded time scale (black thin trace) and after a co-application of TEA and Cd2+ (red thick trace) to show that TEA + Cd2+ reveals an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike. D, slow complex bursts on an expanded time scale, revealed by co-application of TEA and Cd2+ in a PC recorded from an acute slice (upper panel, same cell as in B) and from a slice culture (lower panel).

As described for slice cultures, low concentrations of TEA induced bursts of fast APs (compare the first and the second trace in Fig. 8B (n = 5). However, this TEA-induced bursting activity was not clearly associated with the appearance of an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike and slow complex bursts. Slow complex bursting activity (third trace in Fig. 8B) was only obtained with co-application of TEA and Cd2+ (5 × 10−6m, n = 5). Under these conditions, an initial low-threshold transient depolarization triggering a burst of fast APs was also revealed (Fig. 8C, black trace recorded in control conditions versus red trace recorded after TEA + Cd2+). Slow complex bursts in PCs from acute slices revealed by co-application of TEA and Cd2+ (Fig. 8D, upper panel) were similar to the slow complex bursts seen in PCs from slice cultures after the same treatment (Fig. 8D, lower panel, n = 3). As described in Pouille et al. (2000) for PCs recorded in slice cultures, application of Cd2+ alone suppressed repetitive discharge of fast Na+ APs without inducing slow bursting activity (n = 2). Unfortunately, because of the large quantity of toxin required to block P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in continuously perfused acute slices, we were not able to reproduce the evoked responses characterized in slice culture after toxin incubation.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study (Pouille et al. 2000), we have shown that somatic firing of APs evoked in PCs can be divided into three modes. In mode 1, the response consisted of a single spike or a short burst of fast APs at the beginning of the current step. In modes 2 and 3, PCs fired repetitively, with a sustained discharge of fast APs in mode 2 and bursts of fast APs in mode 3. Furthermore, we present evidence than when a dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ AP propagates to the soma, the somatic response starts with a slow but transient depolarization that triggers a burst of fast APs.

In this report, we describe a further firing mode in PCs (mode 4), which consists of repetitive slow complex bursts. We demonstrate that K+ channels sensitive to TEA, CTX, and 4-AP are required for bursts of fast APs (mode 3), for the initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike and for slow complex burst firing (mode 4). We suggest that slow complex burst firing (mode 4) is produced by the repetitive activation of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes invading the soma. The repetitive nature of this pattern of discharge is under the control of a somatic TTX-sensitive Na+ conductance and K+ channels that are sensitive to 4-AP. Furthermore, apamin-sensitive SK channels contribute to the slow afterhyperpolarization that follows each slow complex burst, thereby modulating the firing frequency. We present evidence that P/Q channel activity controls the dendrosomatic propagation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes, most probably by activating the calcium-dependent K+ channels of the BK family. Finally, we show that the firing patterns of APs in PCs in acute slices can also be categorized according to these four modes.

The role of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in dendrosomatic propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike

The regulation of dendrosomatic propagation of Ca2+ spikes by P/Q-type Ca2+ channels emerging from our study constitutes a novel mechanism of neuronal integration that involves an interaction between two distinct types of dendritic Ca2+ channels. How do P/Q-type Ca2+ channels control the dendrosomatic propagation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes? On the basis of our data, an indirect mechanism can be proposed that involves the calcium-dependent K+ channels of the BK family. When these channels are activated by P/Q-channel-mediated Ca2+ entry, the propagation of the low-threshold Ca2+ spike from the dendrite to the soma is prevented. Chelating internal Ca2+ using BAPTA-AM, bath application of micromolar concentrations of TEA or CTX, or preincubation of slices with rIberiotoxin, mimics the effects of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blockade (appearance of an initial low-threshold Ca2+ spike and of slow complex burst firing). However, we can not exclude that the TEA effects are mediated by not only BK channels, but also K+ channels of the Kv3 subfamily that are sensitive to low concentrations of TEA (Coetzee et al. 1999).

If our suggestion is correct, P/Q and BK channels should be expressed on the dendritic membrane of PCs. Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings have demonstrated the presence of both P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (Llinás et al. 1992; Mouginot et al. 1997) and BK channels (Gruol et al. 1991; Jacquin & Gruol, 1999) on PC dendrites. Furthermore, dendritic P/Q (Westenbroek et al. 1995; Pouille et al. 2000) and BK (Cerminara & Rawson, 2000) channel proteins have been revealed using specific antibodies. We propose that a coupling between P/Q and BK channels occurs in PCs, at least on the proximal dendrites where the block of propagation is likely to take place. In neocortical pyramidal neurones, specific coupling has been demonstrated between P/Q-type Ca2+ channels and the calcium-activated K+ channels responsible for the medium afterhyperpolarization (Pineda et al. 1998). However, we cannot exclude that in PCs the activity of P/Q channels controls directly the genesis of the dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spike. Indeed, the dendritic depolarization induced by P/Q channel openings could inactivate low-threshold Ca2+ spikes, as described by Zhan et al. (2000) in thalamic relay cells.

The role of 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels

We show that 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels control the electrogenesis of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes in PCs. Several Kv subunits encode various K+ channels that are sensitive to 4-AP in the micromolar (Kv3 subfamily) or millimolar (Kv1 and Kv4 subfamily) range of concentrations. The Kv1.4, Kv3.3, Kv3.4 and Kv4 subfamilies (summarized as IA) exhibit fast activation and inactivation, whereas Kv1.1, Kv1.3, Kv1.5, Kv3.1 and Kv3.2 inactivate slowly. Moreover, the currents encoded by the Kv4 subfamily activate at a subthreshold range of potentials, whereas those encoded by the Kv1 and Kv3 families activate at a suprathreshold range of potentials.

Conductances sensitive to 4-AP have been reported in rat (Hirano & Hagiwara, 1989; Wang et al. 1991) and mouse (Southan & Robertson, 2000) PCs. The presence of the Kv4 subunit, which mediates the subthreshold (mainly Kv4.3, Serôdio & Rudy, 1998) and suprathreshold (mainly Kv3.3, Weiser et al. 1994) 4-AP-sensitive A-type currents, has been demonstrated in PCs. The pharmacological profile of the K+ current expressed at the somatic level of PCs indicates a dominant contribution of the Kv3 subfamily (Southan & Robertson, 2000). On the basis of our observations, two types of 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels are present in rat PCs. One is sensitive to low concentrations of 4-AP (100 μm): 4-AP at this concentration induced an initial somatic low-threshold Ca2+ spike followed by bursting activity. The other K+ conductance is sensitive to 4-AP in the millimolar range: 1 mm 4-AP induced firing of slow complex bursts (see below). In a previous report in PCs, a low concentration of 4-AP (10 μm) increased Ca2+ spike amplitude and reduced the firing threshold (Etzion & Grossman, 1998). As described by Hoffman et al. (1997), an IA-like current controls retrograde propagation of the Na+ spike in the dendrites of hippocampal neurones. Similarly, we propose that the 4-AP-sensitive K+ conductance in PCs prevents the propagation of dendritic Ca2+ spikes to the soma. The characteristics and localization of the underlying channels, and the nature of the Kv α-subunits involved remain to be determined. Nevertheless, based on the lack of effect of DTX on the firing of PCs, the participation of Kv1 subunits can be excluded.

The firing of slow complex bursts

General features and ionic basis

The motif that we named slow complex burst has also been described in hippocampal pyramidal cells (Golding et al. 1999; Magee & Carruth, 1999) and modelled by Traub et al. (1991). In this model, a back-propagated Na+ AP triggers a dendritic Ca2+ current that outlasts the Na+ AP and provides a depolarization that evokes additional Na+ spikes. In PCs, the firing of complex responses could be due to repetitive activation of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes by a train of Na+ spikes passively invading the dendrite. Nevertheless, in the presence of TTX (n = 5 out of 8), it was still possible in some cases to evoke a low-threshold Ca2+ spike by somatic depolarization, in which case the repetitive activation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes was not observed. This indicates that in PCs a TTX-sensitive conductance, most probably the persistent Na+ conductance (for a review see Crill, 1996), is also required to maintain the membrane potential within a range that allows the repetitive activation of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ spikes. However, the voltage-dependent current activated by hyperpolarization, Ih (Crepel & Penit-Soria, 1986), may also participate in the repetitive firing of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes. Repetitive firing of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes is also under the control of a K+ conductance that is sensitive to 1 mm 4-AP. Thus, in the presence of 1 mm 4-AP, repetitive activation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes was induced by depolarizing current injections, even in the presence of TTX. A 4-AP-dependent A-like current has been implicated in regulating dendritic calcium-spike firing in PCs (Hounsgaard & Midtgaard, 1988; Midtgaard et al. 1993).

The third conductance involved in the control of slow complex burst firing is an apamin-sensitive channel (probably SK). This type of calcium-dependent K+ channel may be specifically coupled to the Ca2+ entry that is mediated by low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (see also Williams et al. 1997) to regulate the Ca2+ spike interval.

It will now be important to identify the Ca2+ channel type(s) underlying the low-threshold Ca2+ spike. Several types of Ca2+ channel subunits have been identified in PCs, mainly α1A (i.e. P/Q-type Ca2+ channels), α1G (i.e. T-type Ca2+ channels), α1E (i.e. class E- or R-type Ca2+ channels). The T- and R-type Ca2+ channels, which are activated at low-threshold, could be responsible for the low-threshold spike. Unfortunately, because of the lack of specific blockers for these types of channels, their relative contribution to the Ca2+ spike could not yet be determined (see Pouille et al. 2000 for detailed discussion and references). Furthermore, we cannot exclude that a new type of calcium-permeable channel underlies the Ca2+ spike.

Comparison with the rhythmic discharge of thalamic neurones

The firing of complex responses after P/Q channel blockade in PCs shares similarities with oscillations described in thalamic neurones (for a review see Destexhe et al. 1999). In these neurones, oscillations present as low-frequency discharges (0.5–12 Hz) of slow (100–300 ms) transient depolarizations (20–30 mV) elicit bursts of fast APs. Slow transient depolarizations are, as we propose in PCs, low-threshold Ca2+ spikes generated by the activation of mainly dendritic low-threshold transient Ca2+ channels. In thalamic relay cells, a sequential activation of Ih and of low-threshold Ca2+ channels mediates this rhythmic activity. However, the ionic basis establishing rhythmic activity is different in PCs. First, complex responses of PCs are triggered at more depolarized potentials (around −50 mV) than the oscillations in thalamic neurones, which appear, depending upon cell type, to be between −85 and −65 mV. Second, thalamic neurones generate a rhythmic discharge of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes even in the presence of TTX. Such differences could result from a different contribution of the K+ conductance sensitive to 4-AP concentrations in the millimolar range. In the presence of 1 mm 4-AP, PCs, like thalamic neurones, can display a rhythmic discharge of slow complex bursts at hyperpolarized potentials and, in the presence of TTX, firing of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes.

Physiological implications

This work raises important questions regarding the physiology of PCs in vivo. Indeed, is the propagation of the dendritic Ca2+ spike we describe involved in generating the complex response elicited by climbing fibre stimulation (Eccles et al. 1967)? Climbing fibre input to the active membrane model of the complex spike developed by De Schutter & Bower (1994b) results in an extensive depolarization of the dendritic tree associated with substantial Ca2+ currents in all regions. While it has been shown that dendritic Ca2+ channels play an important role in generating the complex spike (Eilers et al. 1995), it is still not clear which type of Ca2+ channels expressed in PCs (P/Q or T) is involved in complex spike formation (De Schutter & Bower, 1994b). Based on these studies and on the unexpected observation that the complex spike resembles the complex burst we describe after P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blockade, we raise the hypothesis that the dendrite-initiated low-threshold Ca2+ spike propagating to the soma could be responsible for the long depolarization of the climbing-fibre-evoked complex spike. To test this hypothesis, the ionic mechanisms underlying the complex spike produced by climbing fibre activation in olivocerebellar co-cultures (Mariani et al. 1991) should be determined.

Another question concerns the development of PCs in cerebellar cultures. It has been proposed that immature PCs are able to generate only simple spikes, whereas mature PCs generate both simple and complex spikes (Gruol & Franklin, 1987; Drake-Baumann & Seil, 1995). The complex-spike-like activity recorded in PCs from dissociated cultures resembles the slow complex bursts we describe in PCs from slice cultures. Gruol et al. (1992) proposed that the complex-spike-like activity is produced when the low-threshold Ca2+ current is activated. The absence of complex-spike-like activity in immature PCs may therefore be related to the late development of dendritic low-threshold Ca2+ conductances coincident with the development of the dendritic tree. Nevertheless, a direct link between the development of PCs in culture and the appearance of complex-spike-like activity has not been established. From our observations, even if all PCs after 3–4 weeks in slice cultures have developed a dendritic arborization, only 9 % of them display complex-spike-like spontaneous activity under control conditions (see Fig. 7). This proportion increased drastically when P/Q-type Ca2+ channels or 4-AP-sensitive K+ channels were blocked. This indicates that a large proportion of PCs from slice cultures express the ionic conductances underlying the complex-spike-like activity, but that the ability to generate this activity is a regulated process that appears to be independent of the developmental stage of the PCs.

It is well known that neuronal electrical properties and ionic channel expression vary during development and depend upon culture conditions. Thus, the properties of PCs we describe may be specific for young developing PCs. Nevertheless, PCs in acute slices from adult rats also fired according to the four modes we describe for PCs in slice cultures. However, slow complex burst firing is induced only after co-application of Cd2+ and 100 μm TEA. This indicates that the major electrophysiological properties of PCs after 3 weeks in slice culture are close to those of mature PCs recorded in acute slices. However, the segregation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes in the dendrite by K+ and P/Q-type Ca2+ conductances is probably more efficient in adult PCs in acute slices compared to PCs in slice cultures.

Finally, slow complex bursts were also observed under physiological conditions at a resting potential of around −50 mV (see Fig. 7B), and inactivated at around −30 mV (see Fig. 4). Furthermore, the activation threshold of slow complex burst firing could be shifted towards more hyperpolarized potentials (around −80 mV) when 4-AP-sensitive channels were blocked (see Fig. 5). Consequently, depending upon the degree of activation of 4-AP-sensitive channels, slow complex burst firing could occur over a large window of potentials centred around the physiological resting membrane potential.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor B. Gähwiler and Drs A. Feltz, V. Steuber and U. Gerber for their helpful comments and suggestions on this manuscript. This work was supported by the FRM (FDT 2001 121 4020/2).

REFERENCES

- Candia S, Garcia ML, Latorre R. Mode of action of iberiotoxin, a potent blocker of the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Biophysical Journal. 1992;63:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerminara NL, Rawson JA. Distribution of calcium-activated potassium channels in the cerebellum of the rat. Society of Neurosciences Abstracts. 2000;255.6:73. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, Moreno H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;29:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert CM, Pan E. Arachidonic acid reciprocally alters the availability of transient and sustained dendritic K+ channels in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurosciences. 1999;19:8163–8171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08163.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel F, Penit-Soria J. Inward rectification and low-threshold calcium conductance in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of Physiology. 1986;372:1–23. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crill WE. Persistent sodium current in mammalian central neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:349–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guérineau NC, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Action-potential propagation gated by an axonal I(A). -like K+ conductance in hippocampus. Nature. 1997;389:286–289. doi: 10.1038/38502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter E, Bower JM. An active membrane model of the cerebellar Purkinje cell. I. Simulation of current clamp in slice. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994a;71:375–400. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter E, Bower JM. An active membrane model of the cerebellar Purkinje cell. I. Simulation of synaptic responses. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994b;71:401–419. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destexhe A, McCormick DA, Sejnowsky TJ. Thalamic and thalamocortical mechanisms underlying 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharges. Progress in Brain Research. 1999;121:289–307. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake-Baumann R, Seil FJ. Electrophysiological differences between Purkinje cells in organotypic and granuloprival cerebellar cultures. Neuroscience. 1995;69:467–476. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00263-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Ito M, Szentagothai I. The Cerebellum as a Neuronal Machine. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers J, Callewaert G, Armstrong C, Konnerth A. Calcium signaling in a narrow somatic submembrane shell during synaptic activity in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:10272–10276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzion Y, Grossmann Y. Potassium currents modulation of calcium spike firing in dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Experimental Brain Research. 1998;122:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s002210050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gähwiler BH. Organotypic monolayer cultures of nervous tissue. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1981;4:329–342. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(81)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Jung HY, Mickus T, Spruston N. Dendritic calcium spike initiation and repolarization are controlled by distinct potassium channels subtypes in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:8789–8798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08789.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottmann K, Lux HD. Low-and high-voltage-activated Ca2+ conductances in electrically excitable growth cones of chick dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;110:34–39. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90783-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruol DL, Deal CR, Yool AJ. Developmental changes in calcium conductances contribute to the physiological maturation of cerebellar Purkinje neurons in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:2838–2848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02838.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruol DL, Franklin CL. Morphological and physiological differentiation of Purkinje neurones in cultures of rat cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:1271–1293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-05-01271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruol DL, Jacquin T, Yool AJ. Single-channel K+ currents recorded from the somatic and dendritic regions of cerebellar Purkinje neurons in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:1002–1015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-01002.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Hagiwara S. Kinetics and distribution of voltage-gated Ca, Na and K channels on the somata of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;413:463–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00594174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsgaard J, Midtgaard J. Intrinsic determinants of firing pattern in Purkinje cells of the turtle cerebellum in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1988;402:731–749. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin TD, Gruol DL. Ca2+ regulation of a large conductance K+ channel in cultured rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:735–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Christie BR. Active properties of neuronal dendrites. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1996;19:165–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Dipolo R, Marty A. Calcium-induced calcium release in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1994;12:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M. Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell somata in mammalian cerebellar slices. Journal of Physiology. 1980a;305:171–195. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M. Electrophysiological properties of in vitro Purkinje cell dendrites in mammalian cerebellar slices. Journal of Physiology. 1980b;305:197–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Sugimori M, Hillman DE, Cherksey B. Distribution and functional significance of the P-type, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the mammalian central nervous system. Trends in Neurosciences. 1992;15:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90053-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Carruth M. Dendritic voltage-gated ion channels regulate the action potential firing mode of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:1895–1901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. Characterization of single voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels in apical dendrites of rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:67–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani J, Knopfel T, Gähwiler BH. Co-cultures of inferior olive and cerebellum: electrophysiological evidence for multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by olivary axons. Journal of Neurobiology. 1991;22:865–872. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtgaard J, Lasser-Ross N, Ross WN. Spacial distribution of Ca2+ influx in turtle Purkinje cell dendrites in vitro: role of a transient outward current. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:2455–2469. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasho T, Takagi H, Suzuki H, Watanabe S, Inoue M, Kudo Y, Miyakawa H. Low-threshold potassium channels and a low-threshold calcium channel regulate Ca2+ spike firing in the dendrites of cerebellar Purkinje neurons: a modeling study. Brain Research. 2001;89:106–115. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouginot D, Bossu JL, Gähwiler BH. Low-threshold Ca2+ currents in dendritic recordings from Purkinje cells in rat cerebellar slice cultures. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:160–170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00160.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda JC, Waters RS, Foehring RC. Specificity in the interaction of HVA Ca2+ channel types with Ca2+-dependent AHPs and firing behavior in neocortical pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:2522–2534. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F, Cavelier P, Desplantez T, Beekenkamp H, Craig PJ, Beattie RE, Volsen SG, Bossu JL. Dendro-somatic distribution of calcium-mediated electrogenesis in Purkinje cells from rat cerebellar slice cultures. Journal of Physiology. 2000;527:265–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J, Schiller Y, Stuart G, Sakmann B. Calcium action potentials restricted to distal apical dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:605–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.605ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serôdio P, Rudy B. Differential expression of Kv4 K+ channel subunits mediating subthreshold transient K+ (A-type) currents in rat brain. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:1081–1091. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan AP, Robertson B. Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-gated K+ currents in cerebellar basket and Purkinje cells: Kv1 and Kv3 channel subfamilies are present in basket cell nerve terminals. Journal of Neurosciences. 2000;20:114–122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Hausser M. Initiation and spread of sodium action potentials in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1994;13:703–712. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Spruston N, Sakmann B, Hausser M. Action potential initiation and backpropagation in neurons of the mammalian CNS. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank DW, Sugimori M, Connor JA, Llinás R. Spacially resolved calcium dynamics of mammalian Purkinje cells in cerebellar slice. Science. 1988;242:773–777. doi: 10.1126/science.2847315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Wong RK, Miles R, Michelson H. A model of a CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neuron incorporating voltage-clamp data on intrinsic conductances. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;66:635–650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usowicz MM, Sugimori M, Cherksey B, Llinás R. P-type calcium channels in the somata and dendrites of adult cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1992;9:1185–1199. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90076-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Strahlendorf JC, Straslendorf HK. A transient voltage-dependent outward potassium current in mammalian cerebellar Purkinje cells. Brain Research. 1991;567:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91449-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Takagi H, Miyasho T, Inoue M, Kudo Y, Miyakawa H. Differential role of two types of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in the dendrites of rat cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Brain Research. 1998;791:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Kentros C, Moreno H, Franzen L, Hillman D, Baker H, Rudy B. Differential expression of Shaw-related K+ channels in the rat central nervous system. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:949–972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-00949.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Sakurai T, Elliott EM, Hell JW, Starr TV, Snutch TP, Catterall WA. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the alpha 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6403–6418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06403.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Serafin M, Muhlethaler M, Bernheim L. Distinct contributions of high-and low-voltage-activated calcium currents to afterhyperpolarization in cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons of the guinea pig. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:7307–7315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07307.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Tank DW. Dendritic integration in mammalian neurons, a century after Cajal. Neuron. 1996;16:701–716. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan XJ, Cox CL, Sherman SM. Dendritic depolarization efficiently attenuates low-threshold calcium spikes in thalamic relay cells. Journal of Neurosciences. 2000;20:3909–3914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03909.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]