Abstract

The role of cooperative interactions between individual structural regulatory units (SUs) of thin filaments (7 actin monomers:1 tropomyosin:1 troponin complex) on steady-state Ca2+-activated force was studied. Native troponin C (TnC) was extracted from single, de-membranated rabbit psoas fibres and replaced by mixtures of purified rabbit skeletal TnC (sTnC) and recombinant rabbit sTnC (D27A, D63A), which contains mutations that disrupt Ca2+ coordination at N-terminal sites I and II (xxsTnC). Control experiments in fibres indicated that, in the absence of Ca2+, both sTnC and xxsTnC bind with similar apparent affinity to sTnC-extracted thin filaments. Endogenous sTnC-extracted fibres reconstituted with 100 % xxsTnC did not develop Ca2+-activated force. In fibres reconstituted with mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC, maximal Ca2+-activated force increased in a greater than linear manner with the fraction of sTnC. This suggests that Ca2+ binding to functional Tn can spread activation beyond the seven actins of an SU into neighbouring units, and the data suggest that this functional unit (FU) size is up to 10–12 actins. As the number of FUs was decreased, Ca2+ sensitivity of force (pCa50) decreased proportionally. The slope of the force-pCa relation (the Hill coefficient, nH) also decreased when the reconstitution mixture contained < 50 % sTnC. With 15 % sTnC in the reconstitution mixture, nH was reduced to 1.7 ± 0.2, compared with 3.8 ± 0.1 in fibres reconstituted with 100 % sTnC, indicating that most of the cooperative thin filament activation was eliminated. The results suggest that cooperative activation of skeletal muscle fibres occurs primarily through spread of activation to near-neighbour FUs along the thin filament (via head-to-tail tropomyosin interactions).

Calcium regulates actomyosin interactions in vertebrate striated muscles via tropomyosin (Tm) and the three subunits of troponin (Tn), TnC, TnI and TnT (Farah & Reinach, 1995; Gordon et al. 2000). In skeletal muscle, contraction is triggered when two Ca2+ ions bind to coordination sites in the N-terminal EF-hands of skeletal TnC (sTnC) (Grabarek et al. 1992). The stoichiometry of thin filament proteins is one Tm and one Tn complex for every seven actin monomers (A7TnTm), such that an individual, 1 μm-long actin filament consists of two sets of ∼26 A7TnTm structural units (SUs) aligned end-to-end with one set on each side of the actin helix. Each Tm interacts with neighbouring Tms via head-to-tail overlapping contacts. Within the geometry of the sarcomere, up to four myosin S1 heads could potentially interact with each A7TnTm SU (Gordon et al. 2000). Structural studies indicate that S1 binding to actin (cross-bridges) influences the position of Tm on the thin filament (Vibert et al. 1997; Xu et al. 1999). Thus a great number of protein-protein interactions are thought to be involved in establishing the level of thin filament activation during Ca2+-activated steady-state force development.

The steady-state relation between [Ca2+] and force is steeper than expected if force was just proportional to Ca2+ binding, indicating that cooperative mechanisms must be involved in activation of the thin filament (Hellam & Podolsky, 1969; Julian, 1969; Donaldson & Kerrick, 1975). There are several possible sources of cooperative interactions that could account for the steepness of the force-pCa relation. These sources include: (1) coupling between Ca2+ binding at the two N-terminal sites of an individual sTnC and/or Ca2+ binding to sTnC facilitating Ca2+ binding to other sTnC molecules along each thin filament, (2) strong cross-bridge binding-induced increases in Ca2+ binding to sTnC, (3) stabilization of Tm position on the thin filament where strong cross-bridge binding occurs, allowing further localized cross-bridge binding, and (4) spread of activation and strong cross-bridge binding from activated SUs (those with Ca2+ bound to TnC) into neighbouring SUs (those without Ca2+ bound to sTnC) via head-to-tail interactions of the neighbouring Tm molecules, or through the actin filament. This spread of activation would suggest that Ca2+ binding to individual Tn complexes can regulate myosin binding to more than seven actins, such that the size of a functional unit (FU) is larger than an SU, as indicated by solution biochemical studies (Greene & Eisenberg, 1980; Lehrer & Geeves, 1994).

In skeletal muscle, Ca2+ binding to the two N-terminal sites of each sTnC could potentially increase the slope of the force-pCa relation (nH of the Hill equation, eqn (1)) from 1.0 to 2.0 (Grabarek et al. 1983), but there is little evidence for extensive cooperativity between the two Ca2+ binding sites (Zot & Potter, 1987). Evidence also suggests that binding of cycling cross-bridges causes little (Cannell, 1986; Caputo et al. 1994; Vandenboom et al. 1998) or no (Fuchs & Wang, 1991; Martyn et al. 1999) enhancement of Ca2+ binding in skeletal muscle. Fluorescent probe studies have demonstrated some cooperativity in Ca2+ binding along the thin filament (nH of up to 1.5) (Grabarek et al. 1983), but this is not sufficient to completely account for the high nH values in skeletal muscle. On the other hand, there is considerable evidence for cooperative activation via a direct effect of strongly bound cross-bridges, independent of a change in Ca2+ binding. Strongly attached cross-bridges may facilitate further binding of cross-bridges to that SU and into neighbouring SUs in an allosteric or graded manner, resulting in an FU that is larger than each SU (reviewed in Gordon et al. 2000).

Elucidating the exact size and properties of FUs in skeletal muscle cells has proven difficult because isolation of the interactions between neighbouring units (due to head-to-tail interactions of overlapping Tm molecules) is not easy. Earlier efforts to examine ‘near-neighbour’ cooperative interactions involved partial extraction of sTnC from permeabilized muscle fibres (Brandt et al. 1984; Moss et al. 1985). These studies showed that partial extraction of sTnC greatly decreases nH, demonstrating that cooperative interactions along the thin filament are important in establishing the steady-state level of activation attainable at a given [Ca2+]. However, quantitative assessment of cooperative mechanisms may have been limited in these studies because removal of TnC might substantially alter the complex interactions that occur between TnI, TnT, Tm and actin. Earlier studies of S1 and S1-ADP binding to regulated thin filaments in the absence of Ca2+ (Greene & Eisenberg, 1980) and more recent biochemical measures of ATPase and S1 binding to regulated thin filaments in the presence of Ca2+ also suggest that the FU size is > 7 actins and may be 10–12 actins (Maytum et al. 1999). Another technique used in biochemical studies is to disrupt interactions between neighbouring units with non-polymerizable Tm (Mak & Smillie, 1981; Walsh et al. 1985; Pan et al. 1989), but this technique has not been useful in skinned fibre studies because of the difficulty of extracting Tm and replacing it with other tropomyosins. Importantly, evaluations of FU size and the importance of near-neighbour FU cooperative interactions in thin filament activation need to be made in muscle cells (where steric constraints are imposed by the contractile lattice structure) containing the full complement of Tn subunits.

In this paper we describe a method using fibres with the full complement of Tn subunits that allows us to separate the local activation related to Ca2+ binding to individual Tn complexes from the cooperative interactions between neighbouring Ca2+-activated FUs along thin filaments. In chemically permeablized rabbit psoas fibre segments, we completely extracted the native sTnC and reconstituted Tn complexes with varying mixtures of purified native sTnC and a recombinant mutant rabbit sTnC (D27A, D63A) for which Ca2+ coordination at N-terminal low-affinity sites I and II had been disrupted by replacing the aspartic acids at the x position in both EF-hands with alanines (xxsTnC). These mutations are equivalent to the mutations of chicken sTnC used by Szczesna et al. (1996). This technique is similar to the one used by Butters et al. (1997) to study the ATPase of S1 activated by cardiac thin filaments made with varying fractions of a cTnC deficient in N-terminal Ca2+ binding. By varying the ratio of sTnC:xxsTnC reconstituted into skinned fibres we have relatively fine control of the number of FUs. This allows us to study the influence of cooperative interactions between units and, at low sTnC content, we can also study the properties of individual isolated FUs. Measurements of maximal Ca2+-activated force from fibres containing different ratios of sTnC:xxsTnC indicate that Ca2+ binding to individual Tn complexes allows myosin binding to more than the seven actins of an SU. Measures of the force-pCa relations in these fibres demonstrate that loss of near-neighbour interactions greatly reduces the cooperativity of thin filament activation, which suggests that there may be little cooperative activation within individual FUs in rabbit psoas muscle.

A preliminary report of this work has been published previously (Regnier et al. 1999a).

METHODS

Rabbits were housed in the Department of Comparative Medicine at the University of Washington and cared for in accordance with the USA National Institutes of Health Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols were approved by the University of Washington Animal Care Committee.

Recombinant and native troponin C

Preparation of double-mutant rabbit sTnC (D27A, D63A) (xxsTnC)

Total RNA was isolated from adult rabbit skeletal muscle using the guanidium isothiocyanate method of Chomczynski & Sacchi (1987). The rabbits were killed with an overdose of pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1) administered through the marginal ear vein. The rabbit sTnC gene was cloned as previously described for rat cardiac cTnC (Dong et al. 1996). Mutations were introduced at the x positions of the low affinity, N-terminal Ca2+ binding sites 1 and 2 (D27A and D63A, respectively) by site-directed mutagenesis using T7-GEN In Vitro Mutagenesis Kit (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA). The vector pET-24 (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) containing the T7 promoter, lac operator and a kanamycin resistance gene was used for the expression of xxsTnC cDNA in E. coli, and the protein was extracted and purified from bacterial cells as described for rat cardiac cTnC (Dong et al. 1996).

Native troponin C from rabbit skeletal muscle

Native sTnC was purified from ether powder of rabbit skeletal (back and leg) muscles according to the method of Potter (1982). The molecular mass and extinction coefficient used for both native sTnC and xxsTnC were 18 kDa and 0.20 cm−1 at 277 nm. The purity of native sTnC and xxsTnC was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Single fibre mechanics

Experimental solutions

Compositions of relaxing and activating solutions for fibre mechanics experiments were calculated and solutions made as described previously (Martyn et al. 1994). Binding constants used to calculate solution compositions were taken from the USA National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes Database. Solutions contained: 5 mm MgATP, 15 mm phosphocreatine (PCr), 15 mm EGTA, at least 40 mm Mops, 1 mm free Mg2+, 135 mm Na++ K+, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 250 units ml−1 creatine kinase (CK; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), and 4 % (w/v) dextran T-500 (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Ca2+ levels (given as pCa = -log[Ca2+]) were established by varying the amount of Ca(propionate)2. The ionic strength (Γ/2) was 0.17 m and the pH was 7.0 at the experimental temperature of 15 °C.

Preparation of single, glycerinated muscle fibre segments

Segments of single fibres from rabbit psoas muscle were prepared as described by Chase & Kushmerick (1988) with minor modifications. Rabbits were first sedated with ketamine (40 mg kg−1) and xylazine (5 mg kg−1) injected i.m. and then anaesthetized by continuous perfusion through the marginal ear vein with ketamine (19.4 mg ml−1) and xylazine (0.83 mg ml−1) in saline. Exposed psoas muscles were chilled with frozen saline and small bundles of fibres were tied to Teflon strips to maintain physiological sarcomere length upon removal. Upon completion of surgery, each animal was killed with an overdose of pentobarbital (120 mg kg−1). Isolated bundles of psoas fibres were placed first in skinning solution (5 mm MgATP, 25 mm EGTA, 50 mm Mops, 1 mm free Mg2+, 2 mm DTT, 50 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 0.13 mΓ/2 adjusted with K+ as the cation and acetate as the anion, pH 7.1 at 0–4 °C) on ice, followed by 60 min in skinning solution + 0.5 % Brij 58 (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA) at 0–4 °C, and then incubated overnight at 0–4 °C in skinning solution. The fibre bundles were transferred to glycerol:skinning solution (1:1 v/v) for 4–6 h at 0–4 °C and finally stored individually at −20 °C in fresh aliquots of glycerol:skinning solution.

Uniform segments from single fibres were isolated in glycerol:relaxing solution (50:50 v/v) on the chilled stage of a dissecting microscope. Isolated fibre segments were treated with 1 % (v/v) Triton X-100 in relaxing solution to remove membranous residue. In the majority of experiments, the fibre segment ends were chemically fixed by focal application of 1 % glutaraldehyde in H2O to form artificial tendons that minimized compliance (Chase & Kushmerick, 1988). Fibre segments with fixed ends were wrapped in aluminium foil T-clips for attachment to the mechanical apparatus.

Data acquisition and experimental control

Mechanical measurements on individual fibre segments were performed using two sets of apparatus. In all experiments, sarcomere length (LS) was set initially to 2.5 − 2.6 μm using He-Ne laser diffraction and LS was monitored continuously for experiments with fixed-end fibres. These fibres were excluded if LS shortened to < 2.25 μm during contractions in pCa 4.0 activation solution. Preliminary experiments and experiments concerning the relative binding affinities of purified native sTnC vs. xxsTnC in reconstituted fibres were conducted with fibre segments (not glutaraldehyde fixed) wrapped around fine wire hooks connected to a force transducer and a micromanipulator (Martyn et al. 1993). In this limited set of experiments, LS was monitored periodically and force was recorded on a Gould Brush chart recorder model 280 (Valley View, OH, USA).

For most experiments, fibre segments with fixed ends were connected via T-clips to minutien pin hooks on a force transducer and a linear motor, all mounted on the base of a Leitz Diavert (Wetzlar, Germany) inverted microscope (Chase & Kushmerick, 1988). Silicone sealant or vacuum grease was used to stabilize T-clips on the minutien pins. To maintain structural and functional integrity, fibres were periodically (every 5 s) unloaded by being shortened from ∼20 % to ∼80 % of total fibre segment length (LF) at 4 LF s−1, then rapidly restretched to LF (Brenner, 1983; Sweeney et al. 1987; Chase & Kushmerick, 1988) using a Cambridge Technology model 300 motor (Watertown, MA, USA) adjusted for 300 μs step time. The resulting force transients are evident as vertical lines in the slow time base recordings of Fig. 1 and Fig. 3 recorded on a General Scanning (Watertown, MA, USA) model RS4–5P chart recorder. Fibre diameters were measured from digitized images using an XR-77 CCD camera (Sony, Japan), a DT3155 frame grabber (Data Translation, Marlboro, MA, USA) and HLImage++98 software (Western Vision Software, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) for determination of fibre cross-sectional area.

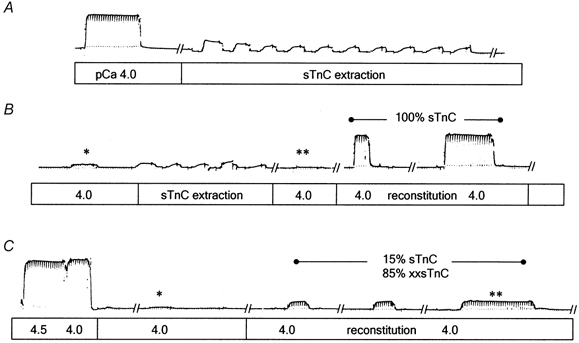

Figure 1. Chart records demonstrating the TnC extraction-reconstitution protocol in single, permeabilized rabbit psoas muscle fibres.

Following determination of Fmax (force at pCa 4.0) endogenous TnC was extracted (force seen during extraction is due to rigor cross-bridges), followed by reconstitution with 100 % sTnC (A and B) or a 15 % sTnC:85 % xxsTnC mixture (C). Cyclical incubations in extraction solution (30 s), followed by incubation in pCa 9.2 solution, were performed until pCa 4.0 force was reduced to < 1–2 % of Fmax (** for fibre in A and B; * for fibre in C). Tn complexes were then reconstituted with TnC-containing solutions until pCa force no longer increased (Fmax,r). For the fibre reconstituted with 100 % sTnC, Fmax,r was 96 % of Fmax (B); for the fibre reconstituted with 15 % sTnC:85 % xxsTnC, Fmax,r was 16 % of Fmax. For A and B, initial force was 80.4 mg and fibre diameter was 52 μm. For C, initial force was 98.2 mg and fibre diameter was 73 μm.

Figure 3. Chart records of Ca2+-dependent force in an example permeabilized psoas muscle fibre.

A, records before extraction of endogenous sTnC; B, records after reconstitution with a solution mixture of 20 % sTnC:80 % xxsTnC; C, records following extraction of the sTnC:xxsTnC mixture and reconstitution with 100 % sTnC. Values for Fmax,r, pCa50 and nH are given in Results. pCa values of the solutions are shown below the records.

Force, LF and LS signals were digitized and analysed using custom data acquisition and control software (Chase et al. 1994). All signals were low-pass filtered (CyberAmp 380, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) to avoid aliasing. Steady-state isometric force was measured with either a Cambridge Technology model 400A (2.2 kHz resonant frequency) or a SensoNor model AE801 (≥ 5 kHz resonant frequency; Horten, Norway) transducer. In all experiments fibres were moved rapidly between solutions of varying pCa held in individual, temperature-controlled troughs. For experiments on fibres with fixed ends, solutions were held in 200 μl troughs of anodized aluminum, chilled by feedback-controlled Peltier thermoelectric chips (Quest Scientific ATR-4 Adaptable Thermoregulator, North Vancouver, BC, Canada). Measurements of total force were obtained from the initial portion of digitized records in which the zero-force baseline was unambiguously determined by a subsequent slackening of the fibre. Maximal Ca2+-activated force (Fmax) was determined at pCa 4.5 or 4.0. Passive force was determined by the same procedure at pCa 9.2 and was subtracted from the total force to obtain Ca2+-activated force. Force was normalized to fibre cross-sectional area (calculated from the diameter, 59 ± 2 μm, assuming circular geometry) and Fmax was 265 ± 14 mN mm−2 (mean ±s.d., n = 37 fibres) prior to extraction of endogenous sTnC.

Extraction of troponin C and reconstitution of Tn complexes

TnC was selectively extracted from fibres as described previously (Regnier et al. 1999b). The TnC-extracting solution contained (mm): 10 Mops, 5 EDTA and 0.5 trifluoperazine (TFP) at pH 6.6 (Metzger et al. 1989; Hannon et al. 1993). In the majority of experiments, fibres were placed in extracting solution for 30 s followed by 15 s in relaxing solution (pCa 9.2), and this procedure was repeated ten times for a total of 5 min in the extracting solution. Alternatively, a single 15 min bout of extraction was performed. The efficacy of extraction was evaluated by measuring Ca2+-activated force at pCa 4.5 or 4.0 after first washing the fibre for 5 min at pCa 9.2 with two solution changes to remove TFP, which has been shown to inhibit Ca2+-activated force (Chandra et al. 1994). Additional extraction was performed if Ca2+-activated force (pCa 4.0) was ≥ 2 % of the control Fmax.

Reconstitution of Tn complexes with mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC was achieved by 1 min incubations in 1 mg ml−1 (total) TnC at pCa 9.2 without CK or dextran (Hannon et al. 1993; Regnier et al. 1999b). Reconstitution was considered complete when force at pCa 4.0 no longer increased (Fmax,r) with subsequent incubations, usually with 5–10 min total incubation (Fig. 1). Prior to reconstitution, fibres were incubated in relaxing solution containing BSA to minimize non-specific binding of TnC. For all reconstitution mixtures elevation of [Ca2+] to pCa 3.5 did not increase values obtained for Fmax,r over those measured at pCa 4.0 or pCa 4.5, indicating that force was maximal. For incorporation of xxsTnC alone, a single 12–15 min incubation was performed. Extraction of native sTnC and reconstitution with purified TnC (sTnC and/or xxsTnC) was evaluated by silver-stained SDS-PAGE and force reconstitution and will be discussed later (Fig. 2). Analysis using SDS-PAGE indicated that no loss of myosin light chains resulted from the sTnC extraction procedure.

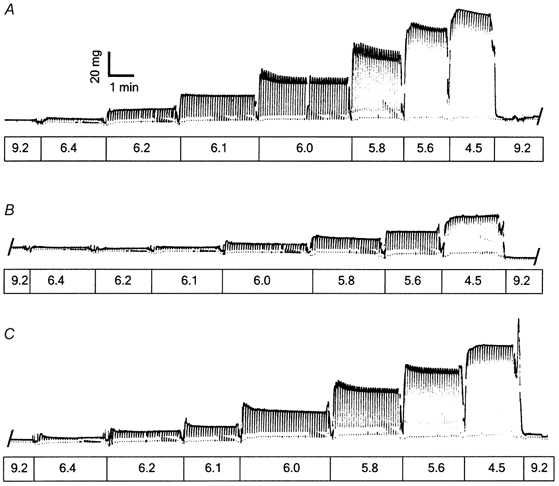

Figure 2. Force assay used to determine the relative binding affinity of sTnC and xxsTnC to thin filaments in permeabilized psoas fibres.

Details are given in Results. A, chart records of force for an example fibre showing Fmax and complete recovery of force following extraction of endogenous TnC and reconstitution with 100 % sTnC (Fmax,r), followed by reduction of force with repeated exposure to pCa 9.2 solution containing 100 % xxsTnC (1 mg ml−1). A second TnC extraction and reconstitution with 100 % sTnC resulted in the return of Fmax,r to 92 % of pre-extracted Fmax (72.6 mg). Fmax and Fmax,r in pCa 4.0 solutions is indicated by asterisks below the force trace. B, time course of Fmax,r decay for exchange of xxsTnC into muscle fibres reconstituted with 100 % sTnC by the protocol described in A (▾). The decay of force was well fitted by the equation: y = ymin+ae−bx (r2 = 0.983), where ymin = 35 % Fmax, the amplitude a = 1 - ymin and the time constant for force decay (1/b) was 6.2 min (continuous line). Incubation in pCa 9.2 solution alone (♦) or pCa 9.2 solution containing 1 mg ml−1 BSA (▪) did not reduce Fmax,r. Reconstitution of extracted fibres with 100 % xxsTnC resulted in no Ca2+-activated force, and subsequent incubations in 100 % sTnC solutions resulted in a progressive increase in Fmax,r (•) that was well fitted by the equation: y = y0+a(1 - e−bx) (r2 = 0.980), where a = 65 % Fmax and the time constant for force rise (1/b) was 6.6 min (continuous line).

Curve fitting and statistical analyses

The force-pCa relation prior to endogenous sTnC extraction and following Tn complex reconstitution was evaluated for each fibre by fitting the Hill equation to the data:

| (1) |

using non-linear least squares regression analysis (SigmaPlot version 5, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Individual fibre force was normalized to Fmax or Fmax,r for estimation of the regression parameters, pCa50 and nH. For individual regressions, parameter estimates are given ±s.e. Average force values and regression parameter estimates for each experimental condition are reported as means ±s.e.m. Comparisons were made using Student's t tests (Excel 2000, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

RESULTS

Replacement of sTnC with mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC

For each fibre, Fmax and the force-pCa relation were determined prior to extraction of native TnC. Following reconstitution of the Tn complex with either purified sTnC (control) or mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC, these measurements were repeated to determine reconstituted Fmax (Fmax,r) and changes in the force-pCa relation. Figure 1 shows example chart records of force demonstrating the extraction-reconstitution protocol. Following measurement of Fmax, native TnC was extracted from the fibre by a series of ten 30 s incubations (Fig. 1A; see Methods). Force at pCa 4.0 was then tested (*, Fig. 1B) and, since a small amount of force remained, the fibre was incubated for five more 30 s cycles in extraction solution. The second test at pCa 4.0 gave a force of < 1 % of pre-extracted Fmax (**, Fig. 1B). Tn complexes within the fibre were then reconstituted by repeated 1–2 min incubations in pCa 9.2 solution containing 100 % sTnC (1.0 mg ml−1 protein) until force at pCa 4.0 no longer increased. In this example fibre, Fmax,r was 96 % of (pre-extracted) Fmax after two incubations in sTnC. In a second fibre (Fig. 1C), following determination of Fmax, native TnC was extracted (not shown, extracted force at pCa 4.0 indicated by *) and reconstitution with a mixture of 15 % sTnC and 85 % xxsTnC (1 mg ml−1 total protein) was achieved by three, 2 min incubations in pCa 9.2 solution. In this fibre, Fmax,r (** in Fig. 1C) was 16 % of Fmax.

Apparent binding affinities of xxsTnC and sTnC to Tn complexes in fibres

The proportion of Tn complexes reconstituted with sTnC vs. xxsTnC depends not only on the proportion of each species in the reconstitution mixture, but also the relative binding affinities of these two TnCs to the open site. Since reconstitution was carried out at pCa 9.2, the relative affinities needed to be estimated under this condition. They were assessed by measuring the ability of sTnC or xxsTnC to displace the other when incorporated into a skinned fibre, as demonstrated in Fig. 2. In separate groups of fibres Tn complexes were reconstituted with either 100 % xxsTnC or 100 % sTnC. In the example force trace shown in Fig. 2A, Fmax was determined (first *), endogenous sTnC was extracted (first arrow, second *), and following two 1 min incubations in 100 % sTnC, Fmax,r (fourth *) was equal to the control Fmax (first *). To test the ability of xxsTnC to exchange with sTnC, the reconstituted fibre was then incubated in pCa 9.2 solution containing 100 % xxsTnC for 1 min periods, followed by testing for reduction of Fmax,r. This cycle was repeated six times (fifth to eleventh *). In this fibre, a second TnC extraction was performed followed by reconstitution of Tn complexes with 100 % sTnC to demonstrate that the force decay was not due to deteriorating fibre quality. This second reconstitution restored Fmax,r to 92 % of pre-extracted Fmax (final * in Fig. 2A). The time course of xxsTnC exchange for sTnC for several fibres, with up to 22 repeated incubations in xxsTnC, is summarized in Fig. 2B (▾). As can be seen, the time course of exchange was slow in comparison to that for reconstitution of TnC-extracted fibres (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2A), but force decreased to 35 % of Fmax,r over the time examined, indicating substantial exchange of xxsTnC for sTnC in thin filament Tn complexes.

Comparable experiments in which fibres were first reconstituted with 100 % xxsTnC, then incubated in sTnC, are summarized in Fig. 2B. Following incubation in 100 % xxsTnC for 10–15 min, a test of Fmax,r indicated no Ca2+-dependent force (• at time = 0) (in agreement with Szczesna et al. 1996). However, when these fibres were subsequently incubated for 1 min periods in 100 % sTnC, followed by tests of the force in pCa 4.0 solution (• at times > 0), Fmax,r slowly increased to 65 % of Fmax with a time course indicating that exchange of sTnC for xxsTnC (•) was similar to the time course of exchange of xxsTnC for sTnC (▾). Following a second total TnC extraction and reconstitution with 100 % sTnC, Fmax,r rapidly (within 1–3 min) returned to the level of Fmax at the beginning of the experiments for all fibres (data not shown). Single exponential fits to these data (continuous lines) yielded similar half-times of Fmax,r decay (with sTnC incubations) or recovery (with xxsTnC incubations), indicating that each form of TnC (xxsTnC or sTnC) appears to be equally effective at displacing the other TnC bound in the Tn complex of fibres (see legend to Fig. 2 for details). To determine whether these results could be explained by gradual loss of TnC from Tn complexes rather than by competitive binding, fibres were reconstituted with 100 % sTnC, and the force in pCa 4.0 solution was repeatedly measured following 1 min incubations in relaxation solution, in either the absence or presence of BSA (shown in Fig. 2B as ♦ and ▪, respectively). These procedures did not affect Fmax,r, suggesting that either form of TnC reconstituted into thin filament Tn complexes was stably bound, but could be displaced by competing TnC. Taken together, our force measurements in permeabilized fibres suggest similar affinities of sTnC and xxsTnC for Tn complexes in thin filaments. This conclusion is supported by measurements made by V. Korman & L. S. Tobacman (personal communication) showing similar binding affinities of Tn reconstituted from sTnC or xxsTnC for Tm-actin filaments in solution (see Discussion). Silver-stained SDS gels demonstrated that sTnC could be extracted totally from fibres and that sTnC and/or xxsTnC could be reconstituted into the fibres (not shown). Quantitative determination of the extent of sTnC and xxsTnC reincorporation into the fibres when the two proteins were mixed in the reconstitution solution was not possible using gels because the silver staining intensity of xxsTnC was much less than that of sTnC.

Ca2+-activated force with TnC mixtures

To determine how reduced numbers of FUs affect thin filament activation with maximal and sub-maximal [Ca2+], force-pCa relations were determined in fibres with Tn complexes reconstituted with varying mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC. The Ca2+ dependence of force was characterized by two parameters obtained from fitting the Hill equation to the data (see Methods), the negative log[Ca2+] required to elicit half of the maximal Ca2+-activated force (i.e. pCa50 or Ca2+ sensitivity; eqn (1)) and the slope (nH or Hill coefficient). Figure 3 shows force traces for an example fibre recorded prior to extraction of native TnC (A) and following reconstitution with a TnC mixture of 20 % sTnC:80 % xxsTnC (B). Following reconstitution, Fmax,r was 35 % of pre-extracted Fmax, pCa50 was reduced from 5.92 ± 0.01 to 5.67 ± 0.01 (P < 0.01) and nH was reduced from 3.5 ± 0.3 to 2.0 ± 0.2 (P < 0.01). In this fibre the TnC extraction procedure was then performed a second time, and the fibre subsequently reconstituted with 100 % sTnC to determine the reversibility of the decrease in Fmax,r, pCa50 and nH (Fig. 3C). Following this second TnC reconstitution, Fmax,r recovered to 88 % of pre-extracted Fmax, pCa50 recovered to 5.87 ± 0.01 and nH recovered to 3.1 ± 0.3.

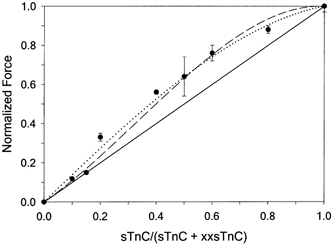

The level of Fmax,r increased with the fraction of sTnC in the reconstitution mixture, i.e. with the fraction of FUs in thin filaments of fibres. This relation is summarized in Fig. 4. The level of Fmax,r increased more than proportionally as the fraction of sTnC in the reconstitution solution was increased to > 15 % of total TnC (indicated by elevation above the continuous line representing proportionality in Fig. 4). If sTnC and xxsTnC incorporate into the Tn complexes of fibres in proportion to the mixture solution, as suggested by control measurements (Fig. 2), the greater than linear increase in Fmax,rvs. the fraction of FUs (Fig. 4) implies that Ca2+ binding to sTnC and the associated cross-bridge binding can activate a greater length of the thin filament than the A7TnTm SU. Analysis of these data (see Appendix) suggests that Ca2+ binding to each sTnC exposes 10–12 actins for myosin binding.

Figure 4. Dependence of Fmax,r on the reconstitution mixture of sTnC and xxsTnC.

For all mixture ratios > 0.2, Fmax,r was greater than proportionality between force and sTnC content (indicated by continuous line). Dotted and dashed lines are model fits to the data (see Appendix).

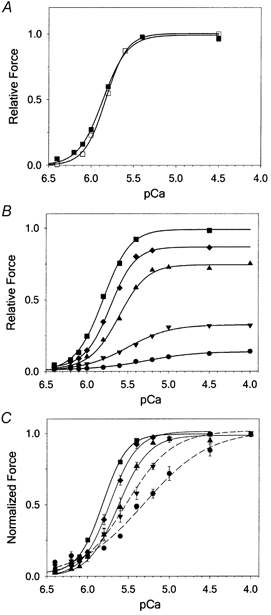

The fraction of FUs also greatly affects the Ca2+ sensitivity of force. To determine whether any changes in the force-pCa relation result from the extraction and reconstitution procedure we first compared fibres prior to extraction, then following reconstitution with 100 % sTnC. The data for the example fibre shown in Fig. 5A demonstrate that this procedure had little effect on maximal force or the Ca2+ dependence of force (Hill fit values in legend to Fig. 5). For five fibres reconstituted with 100 % sTnC, Fmax,r was similar (0.97 ± 0.01) to Fmax, pCa50 was unchanged (5.83 ± 0.02 reconstituted vs. 5.85 ± 0.02 pre-extracted) and there was a small decrease in nH (3.8 ± 0.1 reconstituted vs. 4.4 ± 0.2 pre-extracted).

Figure 5. Force- pCa relations in fibres prior to extraction of endogenous TnC and after reconstitution with mixtures of sTnC and xxsTnC.

A, in this example fibre reconstituted with 100 % sTnC, Fmax,r was 96 % of pre-extracted Fmax, pCa50 was unchanged (5.86 ± 0.01 reconstituted vs. 5.83 ± 0.01 pre-extracted) and nH was decreased slightly (4.0 ± 0.1 reconstituted vs. 4.6 ± 0.2 pre-extracted). B, summary of pCa-force data for fibres with reconstitution mixtures containing 15 % sTnC (•), 20 % sTnC (▾), 60 % sTnC (▴), 80 % sTnC (♦) and 100 % sTnC (▪). Data for 40 % sTnC have not been plotted for ease of viewing. Force is normalized relative to Fmax. C, data from B, normalized to Fmax,r for each fibre to visualize changes in pCa50 and nH.

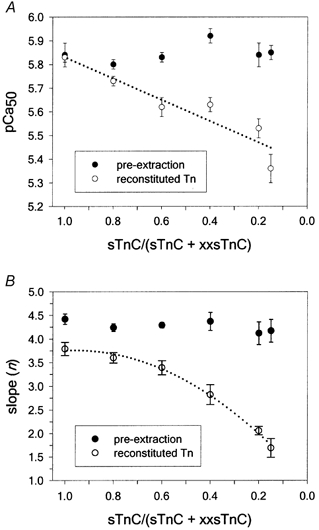

The effect of varying reconstitution mixtures on the Ca2+ dependence of force is summarized in Fig. 5B and C and values for pCa50 and nH are summarized in Fig. 6. Values following reconstitution with TnC mixtures were compared with the values obtained in fibres following reconstitution with 100 % sTnC, to eliminate the influence of the minimal procedural effects. Measures of the force-pCa relation were limited to reconstitution mixtures containing at least 15 % sTnC (and 85 % xxsTnC) because we could not accurately measure small changes in force at low Ca2+ concentrations in fibres with a sTnC content of ≤ 10 % (where Fmax,r was < 15 % of pre-extracted Fmax). Figure 5B shows that as the sTnC content of the reconstitution mixture was reduced, there was a progressive decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of the force accompanying the decrease in Fmax,r. To compare values obtained for pCa50 and nH, and to better visualize the relative effect of different TnC mixtures on the force-pCa relation, force was normalized to Fmax,r following reconstitution (Fig. 5C). This comparison clearly shows that, as the content of sTnC in the reconstitution mixture was reduced, there was a rightward shift of the force-pCa relation, characterized by a progressive decrease in pCa50 (summarized in Fig. 6A). In fibres reconstituted with mixtures containing only 15 % sTnC, pCa50 decreased approximately 0.5 pCa units, indicating a large decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of force. The slope of the force-pCa relation was also reduced as the sTnC content of fibres was reduced. With reconstitution mixtures containing > 50 % sTnC the decrease in nH was small, but when the sTnC content was reduced to < 50 % the decrease in slope was more dramatic and nH was only 1.7 ± 0.2 for fibres with reconstitution mixtures containing only 15 % sTnC (Fig. 6B). This low value of nH indicates that most of the apparent cooperativity in the force-pCa relation was eliminated.

Figure 6. Dependence of pCa50 (A) and nH (B) parameters from the Hill equation fits to force-pCa data on the fraction of sTnC in reconstitution mixtures.

The data in A were fitted with the linear equation: y = y0+ax (dotted line) yielding a slope of 0.45 + 0.09 and y0 = 5.83 ± 0.09 (r2 = 0.87). The reconstitution data in B were fitted with the quadratic formula: y = y0+ax+bx2, where y0 = 0.95 ± 0.11 (r2 = 0.995).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report a method to study how the cooperative interactions between neighbouring FUs in skeletal muscle thin filaments influence steady-state force development in skinned skeletal muscle fibres. By extracting endogenous sTnC from permeabilized muscle fibres and reconstituting with mixtures of the xxsTnC mutant (deficient in Ca2+ binding to the two N-terminal trigger sites) and purified native sTnC, we produced conditions in which interactions between individual FUs were reduced or disrupted. Maximal Ca2+-activated force was absent with 100 % xxsTnC and increased in a greater than linear manner with the percentage of sTnC in the reconstitution solution (Fig. 4). The Ca2+ sensitivity of force decreased in proportion to the fraction of FUs, with a greater than threefold increase in [Ca2+] needed to reach pCa50 when fibres were reconstituted with only 15 % sTnC in the mixture (Fig. 6A). This implies that the Ca2+ dependence of activation for FUs increases with an increase in the probability that one or both neighbouring FUs can be activated. However, Ca2+ binding to FUs appears to be unaltered by the loss of neighbouring FUs since Ca2+-activated force was obtained at the lowest [Ca2+] tested (pCa 6.4) both prior to native sTnC extraction (2 ± 0.3 % Fmax) and following reconstitution (2 ± 0.2 % Fmax) with only 15 % sTnC, even though Ca2+ sensitivity was decreased by 0.5 pCa units (Fig. 5B). In contrast to pCa50, nH decreased less than the fraction of FUs until the sTnC content in mixtures was near 0.6, then it decreased to a value of about 1.7 when the fraction was 0.15 (Fig. 6B). Since nH has been used as a standard measure of cooperativity, this suggests that a factor(s) contributing to cooperative activation of the thin filament was lost as the fraction of FUs was reduced to < 0.6. We conclude that this decreased nH most probably results from decreased cooperativity between near-neighbour FUs when non-functional units are randomly located along thin filaments. Additionally, the results obtained with low fractions of FUs suggest that there is minimal cooperative activation within individual, isolated FUs in psoas muscle fibres.

The ability to isolate FUs depends critically on the assumption that the affinities of the sTnC-extracted thin filaments for sTnC and xxsTnC were equal under the conditions used for reconstitution. If the affinities are equal, the distribution of xxsTnC along the thin filament should be random and the proportion of each TnC should be determined by the ratio of xxsTnC to sTnC in the reconstitution mixture because diffusion coefficients of sTnC and xxsTnC are expected to be very similar. In our experiments, either protein could displace the other from Tn complexes in muscle fibres with a similar time course (Fig. 2), suggesting that the affinities were equal under our conditions. However, if the ratio of affinities of sTnC:xxsTnC for binding to the open site in TnC-extracted fibres was about 1.9, we could explain the data at concentrations of sTnC of 20 % and higher, but this would predict much greater force values than we observed for the 10 and 15 % sTnC data. A difference of 1.9 in relative affinities should also have been apparent in the time courses of exchange shown in Fig. 2. Thus although we cannot completely rule out that different affinities can account for some of the deviations from linearity in Fig. 4, we do not think that it accounts for the entire difference. Furthermore, Morris et al. (2001) have recently demonstrated similar affinity of the comparable cardiac TnC (cTnC) mutant (CBMII) vs. cTnC for Tn complexes in de-membranated psoas fibres under conditions similar to those used in the present study. The idea that TnC mutants with low N-terminal Ca2+ capacity have binding affinities similar to those of native TnC for Tn complexes in thin filaments is further supported by the demonstration that, in the absence of Ca2+, cTn made from either cTnC or CBMII bound with equal affinity to actin-tropomyosin (Huynh et al. 1996). Additionally, sTn made from either sTnC or xxsTnC bound with equal affinity to actin-tropomyosin in the absence of Ca2+ (L. S. Tobacman & V. Korman, personal communication), as demonstrated by the equal ability to displace Tn made with cardiac TnC from thin filaments. All of these data suggest that, under our reconstitution conditions (i.e. pCa 9), the affinities are equal and therefore the distribution of sTnC and xxsTnC along thin filaments should be random. Thus fibres reconstituted with low sTnC content should have FUs with a high probability of having units that cannot be activated (i.e. those with xxsTnC bound to Tn) on either side, and therefore the thin filaments in these fibres would have isolated FUs.

Properties of isolated FUs

The use of xxsTnC to reduce or eliminate near-neighbour interactions allowed us to estimate the properties of isolated FUs in fast skeletal muscle thin filaments. The data in Fig. 4 show how the fraction of FUs affects maximal Ca2+-activated force, and clearly suggest that the length of thin filament activated by Ca2+ binding to an individual sTnC is not the same as that of the A7TnTm SU. If this length is just seven actins (A7) Fmax,r should be proportional to the fraction of Ca2+-activatable units (dotted line in Fig. 4). If the size of isolated FUs is < A7, the curve in Fig. 4 should start with a slope of less than one, with an upward curvature determined by the level of near-neighbour cooperativity that occurs along the thin filament. However, the data show a convex curve with a decreasing slope as force approaches maximum, indicating an FU size > A7. Our estimate of FU size from analysis of the data in Fig. 4 (see Appendix) suggests that Ca2+ binding to each Tn can make 10–12 actins available for strong myosin binding. Biochemical experiments have also suggested that the FU size is > 7 actins and may be 10–12 actins (Maytum et al. 1999) or more (Greene & Eisenberg, 1980). Finally, the Tn extraction data of Moss et al. (1986) also indicate an FU size of > 7 actins.

Interestingly, Morris et al. (2001) recently reported that extraction of endogenous TnC from skinned psoas muscle fibres, followed by reconstitution with mixtures of cardiac TnC and CBMII cTnC (the cardiac form of xxsTnC) produced a linear relation between the fraction of FUs and maximal Ca2+-activated force. They interpreted this linear relation to be the result of positive cooperativity from FUs being balanced by a negative cooperative effect from neighbouring units containing CBMII. An alternative explanation is that cardiac TnC is less able to activate the thin filament, as suggested by the ability of cTnC-reconstituted fibres to produce only about 65 % of the maximal Ca2+-activated force seen prior to extraction (Morris et al. 2001). Perhaps the size of an FU in psoas fibres reconstituted with cTnC is only ≤ 7 actins. The idea that cTnC activates fewer actins than sTnC is supported by Butters et al. (1997), who measured cardiac S1 ATPase data with actin reconstituted with various ratios of Tn containing cTnC and CBMII and found that the relation between Ca2+-activated ATPase vs. fraction of cTnC was concave. This may imply that < 7 actins were activated by Ca2+ binding to each cTnC-containing FU. The implication of the data from Morris et al. (2001) and Butters et al. (1997) may be that the size of an FU is smaller in cardiac muscle than in skeletal muscle. However, even if the non-activatable units (those containing xxsTnC) in our experiments did exert negative cooperativity, this would suggest that our value of 10–12 actins is a lower limit of size for an FU.

The data in Fig. 6 enable us to estimate the steady-state force-pCa properties of isolated FUs in muscle fibres. The dotted line in Fig. 6A is a linear fit to pCa50 as a function of the fractional sTnC in reconstitution mixtures. The dotted line in Fig. 6B is a quadratic fit of nH as a function of the fractional sTnC in reconstitution mixtures. Extrapolating these curves to extremely low levels of sTnC could provide information about the properties of an isolated FU in muscle fibres. At an sTnC content close to zero the extrapolated value of pCa50 approaches 5.38 and the extrapolated value for nH approaches 1.0. If extrapolation correctly reflects the properties of isolated FUs, it would suggest little or no cooperative Ca2+ activation in individual units, and steady-state force generation in each isolated FU would simply be proportional to Ca2+ binding to sTnC. It would also suggest that the apparent Ca2+ affinity for sTnC in an isolated FU is ∼4.2 μm. However, extrapolation of the data may not accurately reflect the properties of isolated FUs, particularly in the case of nH, so additional data at very low levels of sTnC need to be obtained to verify these conclusions. At the lowest sTnC concentration (15 %) used to obtain the data in Fig. 6, only a small amount of cooperativity remained (as indicated by the nH value of 1.7).

Cooperative activation along the thin filament

Prior to TnC extraction, pCa50 was 5.85 and nH was 4.4, values much greater than those obtained under conditions that maximize isolation of FUs (Fig. 6). From these data, and the preponderance of evidence from other investigators (reviewed in Gordon et al. 2000), it is clear that there is a high degree of cooperative activation along the thin filament via interactions between FUs. This is demonstrated most dramatically in Fig. 6B, where nH decreases when the fraction of sTnC in the reconstitution mixture is reduced to < 0.5, a point at which about half the units would be expected to have an FU as a nearest-neighbour. The strong dependence of nH on the fraction of FUs, and the small value of nH when fibres are reconstituted with only 15 % sTnC, clearly suggests that near-neighbour FU cooperativity is crucial for complete activation of skeletal muscle thin filaments by Ca2+ binding and strong cross-bridge attachment.

The most likely source of this form of cooperativity is through coupling between overlapped neighbouring Tms along the thin filament, although one cannot rule out some contribution from actin-actin interactions. Since there is little evidence of strong cooperativity in Ca2+ binding between consecutive Tns along the thin filament, the major candidate for cooperative thin filament activation in skeletal muscle must be strong cross-bridge binding to actin monomers stabilizing Tm in the ‘on’ position, not only within an individual FU, in which initial strong cross-bridge attachment might occur, but also into neighbouring FUs, via transmission through Tm overlap.

The large effect that the fraction of FUs has on nH and pCa50 (Fig. 6) implies that near-neighbour interactions must be important in determining both parameters of thin filament activation. Both Brandt et al. (1984) and Moss et al. (1986) also found that extraction of TnC (without reconstitution of Tn) reduced nH. However, Brandt et al. (1984) found that extraction of a small fraction of TnC reduced nH. They interpreted this to mean that, since extraction of just one TnC from a thin filament decreased cooperativity, the whole thin filament was activated as a unit. Moss et al. (1985) also found a less than linear relation between force and TnC content, in contrast to the greater than linear relation (Fig. 4) we found when all Tn complexes contained TnC (either sTnC or xxsTnC). This result is not surprising since extraction of TnC from the Tn complex should increase binding of TnI to the thin filament in an inhibiting position. Also, sites III-IV of TnC remain intact in the xxsTnC mutant, minimizing any alterations in interactions of TnC with TnI or TnT that might occur. Additionally, there are questions about the uniformity of TnC extraction along the thin filaments of partially extracted muscle fibres (Yates et al. 1993; Swartz et al. 1997). Under our conditions, uniformity of extraction is not an issue, as the endogenous TnC was completely extracted.

The more difficult issue is why the Ca2+ sensitivity of force changes in a linear manner with the fraction of FUs. These results are qualitatively similar to those observed with TnC extraction (Brandt et al. 1984). The implication is that as the sTnC content in the thin filament is increased (in our experiments), the probability that any FU has a neighbouring unit that is also an FU is also increased (see Appendix). Thus the enhanced pCa50 seen under these conditions could simply be due to the movement of Tm in one FU by Ca2+ or cross-bridge binding, making it easier for Ca2+ binding to result in the movement of Tm in the neighbouring FU. Another possibility is that the Ca2+ affinity of TnC in an FU is increased by the activation of a neighbouring FU. This seems less likely since cooperativity in Ca2+ binding along the thin filament is low (Grabarek et al. 1983; Güth & Potter, 1987) and the binding of cycling cross-bridges does not cause a significant increase in Ca2+ binding to skeletal fibre thin filaments (Fuchs & Wang, 1991). A kinetic model of this activation scheme would also depend on consideration of the relative time scale for Ca2+ binding, Tm movement, and strong cross-bridge attachment-detachment, although such a model would require more information on the kinetics of activation than is currently available.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Joe Howard for discussions on models of cooperativity, Larry Tobacman and Vicci Korman for solution measurements of Tn binding to Tm-actin filaments, Drs E. Homsher and D. A. Martyn for critical comments and Ying Chen, Robin Mondares, Carol Freitag, Martha Mathiason and Claire Zhang for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by USA NIH HL61683, HL65497 and HL52558.

APPENDIX

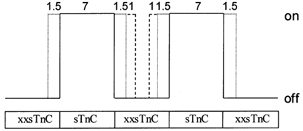

The spread of activation along thin filaments with Ca2+ binding to individual FUs was modelled from the data in Fig. 4. Since there is substantial evidence that tropomyosin (Tm) is flexible and able to move over the surface of the thin filament (reviewed in Gordon et al. 2000), we allowed the number of actins that are activated (available for strong myosin binding) by Ca2+ binding to an individual sTnC to vary from the A7 of the SU. To model cooperative interactions, we have assumed that the thin filament is infinite in length (it is actually 26 A7TmTn SUs long, so an ∼4 % error could be introduced by neglecting end effects of the finite filament), though a more detailed model could involve the statistical calculations used by Butters et al. (1997). The diagram shown in Fig. 7 represents five structural A7TmTn SUs in series along a thin filament, with alternating FUs (those containing sTnC) surrounded by non-activatable FUs (those containing xxsTnC). The myosin binding state of actins can vary from a weak (off) state to a strong, force-bearing state (on) depending on the position of tropomyosin in the thin filament; this is indicated by the lines in Fig. 7. The continuous line represents the actins available for strong cross-bridge binding if only the SU is ‘turned on’ by Ca2+ binding to sTnC. The data in Fig. 4 show that Fmax,r increases in a greater than linear manner with the fraction of FUs, demonstrating an apparent cooperativity of thin filament activation and force generation. In turn, this implies that there is some activation and strong cross-bridge binding to actins outside the A7TmTn SU. This could occur by either (1) an extended size of an isolated unit to greater than seven activated actins or (2) some additional cooperative activation of actins in non-activatable units if both surrounding units could be activated by Ca2+. The former (1) is illustrated by a spread of activation by 1.5 actin monomers in the neighbouring, non-activatable units (dotted lines in Fig. 7). The latter (2) is illustrated by activation of an additional actin monomer in the intervening, non-Ca2+-activatable unit from each Ca2+-activatable unit (dashed lines in Fig. 7). If x were the mole fraction of Tn sites occupied by sTnC, then Fmax,r with cooperative spread by mechanism (1) would be given by:

| (A1) |

Figure 7. Model of activation in fibres with isolated FUs.

For details see Appendix.

The dotted line in Fig. 4 shows the fit of this equation to the data. If mechanism (2) (additional activation of non- Ca2+-activatable units via interactions with surrounding Ca2+-activatable units) were taken into consideration, the additional actin activation and force added would be:

| (A2) |

Combining these two mechanisms for increased activation of actin in neighbouring units gives:

| (A3) |

The dashed line in Fig. 4 illustrates the fit of this combined equation to the data. The values of a and b that are the best fits to the data are a = 1.5 actins (on each side of a Ca2+-activatable unit) and b = 2 actins (of a non-Ca2+-activatable unit), indicated by the dotted (r2 = 0.98) and dashed (r2 = 0.99) lines (respectively) in Fig. 4 and Fig. 7. Fits to the data in Fig. 4 imply that each Ca2+-activatable unit is not limited to the seven actins contained in an SU, but instead extends to 10 actins, and may extend to 12 actins when next-nearest-neighbour units are active.

REFERENCES

- Brandt PW, Diamond MS, Schachat FH. The thin filament of vertebrate skeletal muscle co-operatively activates as a unit. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1984;180:379–384. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Technique for stabilizing the striation pattern in maximally calcium-activated skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1983;41:99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84411-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters CA, Tobacman JB, Tobacman LS. Cooperative effect of calcium binding to adjacent troponin molecules on the thin filament-myosin subfragment 1 MgATPase rate. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:13196–13202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB. Effect of tetanus duration on the free calcium during the relaxation of frog skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1986;376:203–218. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo C, Edman KAP, Lou F, Sun YB. Variation in myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration during contraction and relaxation studied by the indicator fluo-3 in frog muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1994;478:137–148. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra M, Da Silva EF, Sorenson MM, Ferro JA, Pearlstone JR, Nash BE, Borgford T, Kay CM, Smillie LB. The effects of N helix deletion and mutant F29W on the Ca2+ binding and functional properties of chicken skeletal muscle troponin C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:14988–14994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase PB, Kushmerick MJ. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1988;53:935–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase PB, Martyn DA, Hannon JD. Activation dependence and kinetics of force and stiffness inhibition by aluminiofluoride, a slowly dissociating analogue of inorganic phosphate, in chemically skinned fibres from rabbit psoas muscle. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1994;15:119–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00130423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson SKB, Kerrick WGL. Characterization of the effects of Mg2+ on Ca2+- and Sr2+- activated tension generation of skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1975;66:427–444. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Rosenfeld SS, Wang C-K, Gordon AM, Cheung HC. Kinetic studies of calcium binding to the regulatory site of troponin C from cardiac muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:688–694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah CS, Reinach FC. The troponin complex and regulation of muscle contraction. FASEB Journal. 1995;9:755–767. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.9.7601340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs F, Wang Y-P. Force, length, and Ca2+-troponin C affinity in skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;253:C541–546. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.5.C787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek Z, Grabarek J, Leavis PC, Gergely J. Cooperative binding to the Ca2+-specific sites of troponin C in regulated actin and actomyosin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1983;258:14098–14102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek Z, Tao T, Gergely J. Molecular mechanism of troponin-C function. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1992;13:383–393. doi: 10.1007/BF01738034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene LE, Eisenberg E. Cooperative binding of myosin subfragment-1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1980;77:2616–2620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güth K, Potter JD. Effect of rigor and cycling cross-bridges on the structure of troponin C and on the Ca2+ affinity of the Ca2+-specific regulatory sites in skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:13627–13635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon JD, Chase PB, Martyn DA, Huntsman LL, Kushmerick MJ, Gordon AM. Calcium-independent activation of skeletal muscle fibers by a modified form of cardiac troponin C. Biophysical Journal. 1993;64:1632–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellam DC, Podolsky RJ. Force measurements in skinned muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1969;200:807–819. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q, Butters CA, Leiden JM, Tobacman LS. Effects of cardiac thin filament Ca2+: statistical mechanical analysis of a troponin C site II mutant. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79704-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian FJ. Activation in a skeletal muscle contraction model with a modification for insect fibrillar muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1969;9:547–570. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(69)86403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. Dynamics of the muscle thin filament regulatory switch: the size of the cooperative unit. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:273–282. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80478-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak AS, Smillie LB. Non-polymerizable tropomyosin: preparation, some properties and F-actin binding. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1981;101:208–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(81)80032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Chase PB, Hannon JD, Huntsman LL, Kushmerick MJ, Gordon AM. Unloaded shortening of skinned muscle fibers from rabbit activated with and without Ca2+ Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1984–1993. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Coby R, Huntsman LL, Gordon AM. Force-calcium relations in skinned twitch and slow-tonic frog muscle fibers have similar sarcomere length dependencies. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1993;14:65–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00132181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Freitag CJ, Chase PB, Gordon AM. Ca2+ and cross-bridge-induced changes in troponin C in skinned skeletal muscle fibres: effects of force inhibition. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:1480–1493. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77308-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maytum R, Lehrer SS, Geeves MA. Cooperativity and switching within the three-state model of muscle regulation. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1102–1110. doi: 10.1021/bi981603e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger JM, Greaser ML, Moss RL. Variations in cross-bridge attachment rate and tension with phosphorylation of myosin in mammalian skinned skeletal muscle fibers: Implications for twitch potentiation in intact muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;93:855–883. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA, Tobacman LS, Homsher E. Modulation of contractile activation by a calcium-insensitive troponin C mutant. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:20245–20251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss RL, Allen JD, Greaser ML. Effects of partial extraction of troponin complex upon the tension-pCa relation in rabbit skeletal muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 1986;87:761–774. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss RL, Giulian GG, Greaser ML. The effects of partial extraction of TnC upon the tension-pCa relationship in rabbit skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Journal of General Physiology. 1985;86:585–600. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B-S, Gordon AM, Luo Z. Removal of tropomyosin overlap modifies cooperative binding of myosin S1 to reconstituted thin filaments of rabbit striated muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:8495–8498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JD. Preparation of troponin and its subunits. Methods in Enzymology. 1982;85:241–263. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier M, Rivera AJ, Bates MA, Chase PB. Calcium regulation of steady-state force and rate of tension redevelopment in rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1999a;76:A161. [Google Scholar]

- Regnier M, Rivera AJ, Chase PB, Smillie LB, Sorenson MM. Regulation of skeletal muscle tension redevelopment by troponin C constructs with different Ca2+ affinities. Biophysical Journal. 1999b;76:2664–2672. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz DR, Moss RL, Greaser ML. Characteristics of troponin C binding to the myofibrillar thin filament: extraction of troponin C is not random along the length of the thin filament. Biophysical Journal. 1997;73:293–305. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney HL, Corteselli SA, Kushmerick MJ. Measurements on permeabilized skeletal muscle fibers during continuous activation. American Journal of Physiology. 1987;252C:575–580. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.5.C575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczesna D, Guzman G, Miller T, Zhao J, Farokhi K, Ellemberger H, Potter JD. The role of the four Ca2+ binding sites of troponin C in the regulation of skeletal muscle contraction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:8381–8386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenboom R, Claflin DR, Julian FJ. Effects of rapid shortening on rate of force regeneration and myoplasmic [Ca2+] in intact frog skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.171bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert P, Craig R, Lehman W. Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1997;266:8–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh TP, Trueblood CE, Evans R, Weber A. Removal of tropomyosin overlap and the co-operative response to increasing calcium concentrations of the acto-subfragment-1 ATPase. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1985;182:265–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Craig R, Tobacman L, Horowitz R, Lehman W. Tropomyosin positions in regulated thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77:985–992. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates LD, Coby RL, Luo Z, Gordon AM. Filament overlap affects TnC extraction from skinned muscle fibres. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1993;14:392–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00121290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zot HG, Potter JD. Calcium binding and fluorescence measurements of dansylaziridine-labelled troponin C in reconstituted thin filaments. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1987;8:428–436. doi: 10.1007/BF01578432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]