Abstract

Duodenal infusion of hypertonic solutions elicits osmolality-dependent thermogenesis in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Here we investigated the involvement of the autonomic nervous system, adrenal medulla and brain in the mechanism of this thermogenesis. Bilateral subdiaphragmatic vagotomy greatly attenuated the first hour, but not the later phase, of the thermogenesis induced by 3.6 % NaCl (10 ml kg−1). Neither atropine pretreatment (10 mg kg−1, i.p) nor capsaicin desensitization had any effect on the osmotically induced thermogenesis, suggesting the involvement of non-nociceptive vagal afferents. Bilateral splanchnic denervation caudal to the suprarenal ganglia also had no effect, suggesting a lack of involvement of spinal afferents and sympathetic efferents to the major upper abdominal organs. Adrenal demedullation greatly attenuated the initial phase, but not the later phase, of thermogenesis. Pretreatment with the β-blocker propranolol (20 mg kg−1, i.p) attenuated the thermogenesis throughout the 3 h observation period. The plasma adrenaline concentration increased significantly 20 min after osmotic stimulation but returned to the basal level after 60 min. The plasma noradrenaline concentration increased 20 min after osmotic stimulation and remained significantly elevated for 120 min. Therefore, adrenaline largely mediated the initial phase of thermogenesis, and noradrenaline was involved in the entire thermogenic response. Moreover, neither decerebration nor pretreatment with the antipyretic indomethacin (10 mg kg−1, s.c) had any effect. Accordingly, this thermogenesis did not require the forebrain and was different from that associated with fever. These results show the critical involvement of the vagal afferents, hindbrain and sympathoadrenal system in the thermogenesis induced by osmotic stimulation of the intestines.

Food intake stimulates the metabolic rate of the whole body and increases the core body temperature (Tc). This phenomenon has been called diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT), postalimentary hyperthermia or the thermic effect of food. We recently found that duodenal infusion of glucose, fructose or amino acids, as well as non-nutrient NaCl or methylglucose, elicited osmolality-dependent thermogenesis in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Therefore we concluded that osmoreceptors are critically involved in the initiation of DIT (Osaka et al. 2001). Gõbel et al. (2001) also demonstrated that the metabolic rate and Tc of awake rats increased similarly after feeding with conventional chow or saccharine-sweetened CaCO3 or after intragastric injection of BaSO4, and they concluded that gastrointestinal chemical or mechanical, instead of caloric, signals determine the postalimentary hyperthermia.

In the present study, we investigated the mechanisms of thermogenesis induced by the duodenal infusion of hypertonic NaCl. Because the heat production induced by duodenal infusion was larger than that induced by infusion into the femoral or portal vein, which suggested an intestinal or mesenteric location for osmoreceptors (Osaka et al. 2001), we examined the afferent neural pathway by sectioning the vagus and splanchnic nerves. We then examined the possible involvement of the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal catecholamines, because several studies have demonstrated that DIT depends, at least in part, upon β-adrenoceptors (Acheson et al. 1983; Kim et al. 1994). Next we examined the effects of decerebration on the osmotically induced thermogenesis to elucidate the involvement of the forebrain, particularly the hypothalamus, which exerts integrative controls on osmotic, thermal and energy homeostasis. Finally, we tested the effects of pretreatment with an antipyretic, indomethacin, to examine apparent similarities between osmotic- and fever-induced thermogenesis.

METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar rats, weighing 250–320 g, were maintained at an ambient temperature of 24 ± 1 °C with lighting between 07.00 h and 19.00 h for at least 1 week before the experiments started. They had free access to water and laboratory food (MR stock, Nosan, Japan), but were fasted overnight (for ∼14 h) before the start of the experiments. The care of animals and all surgical procedures followed our institutional guidelines.

The rats were anaesthetized with urethane (1.2 g kg−1, i.p) and placed in the supine position on an operating table heated to 30–31 °C. Animals given this dose of urethane remained anaesthetized for at least 10 h, and our experiments always lasted less than 8 h. The method of intraduodenal cannulation was described previously (Osaka et al. 2001). Briefly, a Teflon cannula was inserted through a small incision in the wall of the forestomach and then passed 10 mm beyond the pylorus into the duodenum. The cannula was exteriorized through the abdominal wall and skin, and the incision was closed with surgical silk. The abdominal surface was then covered with a quilt to reduce heat dissipation. Animals were killed by an overdose of anaesthetic at the end of the experiment.

Metabolic and temperature recordings

The head of each rat was covered with a cylindrical hood, which was continuously ventilated at a constant rate of 1.0 l min−1. The difference in concentrations of O2 and CO2 between inflow and outflow air was measured with a differential O2 analyser (LC700E, Toray, Japan) and two CO2 sensors (GMW22D, Vaisala, Finland), respectively. Colonic temperature (Tc) was measured with a thermistor inserted ∼50 mm into the anus. Tail skin temperature was measured with a small thermistor taped to the lateral base of the tail. In some experiments, an electrocardiogram was recorded with needle electrodes subcutaneously inserted into the limbs of the rats. A counter (AT-601G, NihonKohden, Japan) was used to detect R-waves and to calculate the heart rate. All signals were fed into a computer and recorded at 15 s intervals through a PowerLab system (ADInstruments, Australia) for on-line data display and storage. After the experiments, data were averaged over 5 min intervals. The metabolic rate (M) was calculated from measurements of O2 consumption and CO2 production according to the following equation: M (kJ) = 15.8[O2]+ 5.2[CO2] (Kurpad et al. 1994), where [O2] and [CO2] are measured in litres at standard temperature and pressure. Values were corrected for metabolic body size (kg0.75). The amount of energy expenditure induced by infusion of a solution was calculated as the total area of increase in metabolic rate over resting values.

Experimental procedures

A solution of 3.6 % NaCl, 20 % glucose or 0.9 % NaCl was infused into the duodenum at a volume of 10 ml kg−1 for 10 min with a syringe pump (KDS100, KD Scientific, MA, USA). Solutions were warmed to 38–39 °C before administration, but the temperature of the solutions decreased slightly during infusion. The effects of each solution were tested in separate groups consisting of four to six rats.

Atropine sulphate (10 mg kg−1, ip.) was administered 30 min before infusion of the test solution. This dose of atropine was enough to block the sham feeding-induced insulin release in the rat (Berthoud & Jeanrenaud, 1982). dl-Propranolol hydrochloride (10 mg kg−1, i.p) was administered twice at 30 min before, and simultaneously with, the infusion of the test solution. Consequently, a total amount of 20 mg kg−1 propranolol was used. These drugs were dissolved in physiological saline solution. Indomethacin (10 mg kg−1, s.c.), dissolved in 1.25 % sodium bicarbonate solution containing 20 % ethanol, was administered 20 min before infusion of the test solution. This amount of indomethacin has been shown to attenuate fever induced by intravenous injection of lipopolysaccharide (Sehic et al. 1996). Control rats received the same amount of vehicle solution. For capsaicin desensitization, rats received increasing doses (15, 30 and 60 mg kg−1, s.c) of capsaicin, which was dissolved in physiological saline solution containing 10 % Tween 80 and 10 % ethanol, on three consecutive days; experiments were performed 5–10 days later. This procedure has been shown to block capsaicin-induced heat loss and heat production in urethane-anaesthetized rats (Kobayashi et al. 1998).

Sectioning of the subdiaphragmatic vagus and splanchnic nerves was performed under a dissecting microscope before the intraduodenal cannulation. For vagotomy, the stomach was retracted through a midline abdominal incision, and the anterior and posterior subdiaphragmatic vagi were dissected free from the oesophagus and sectioned. For transection of the splanchnic nerves, the mesentery, intestine, spleen and pancreas were placed on the animal's right flank, and they were covered with sterile saline-soaked gauze. The liver lobes were also covered with sterile saline-soaked gauze and were pushed upward. The coeliac plexus was identified on the aorta between its junction with the coeliac and superior mesenteric artery. The major splanchnic nerves were sectioned between the coeliac plexus and the suprarenal ganglion. Care was taken not to damage the adrenal nerves and coeliac branches of the vagus nerves. Visceral organs were then returned to their normal position. Experiments were carried out acutely after the nerve sectioning.

Bilateral adrenal demedullation was performed by the method described by Waynforth & Flecknell (1992) under anaesthesia with ketamine (50 mg kg−1, i.p) and isoflurane (1.2 % in air). Control rats received incisions in their skin and muscles, and the adrenal glands were located but not removed. These rats were used for experiments 2–3 weeks later. At the end of the experiments, blood was collected for catecholamine analysis. Rats with plasma adrenaline concentration > 0.05 ng ml−1 were excluded, as they were considered to represent failed adrenal demedullation.

Decerebration was made either by cerebral transection alone or by the transection and subsequent removal of the forebrain. Transection was made between the hypothalamus and midbrain by a method similar to that described previously (Osaka et al. 1989). Briefly, a slit was made in the frontal plane of the skull at a place 4 mm rostral to the interaural line. An L-shaped knife was then inserted vertically into the brain through the slit with the aid of a micromanipulator until it made contact with the cranium floor. The knife was moved medially, upward to contact the sagittal sinus, and then downward again to the cranium floor. The same procedures were repeated for the other side of the brain. The level of transection was later confirmed by examination of frozen sagittal sections of the brain. Half of the cerebral transected rats were further subjected to removal of the forebrain by suction. The cerebral cortices, hypothalamus, and all tissues rostral to the transection were removed. The cranium floor and cut surface of the brain was covered with a saline-soaked gelatine powder (Gelfoam powder, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Sweden) to prevent gradual bleeding. The incision in the skin was closed with a cyanoacrylate adhesive.

Blood (0.7 ml) was collected for catecholamine analysis through the jugular vein cannula at 0, 20, 60 and 120 min after the intestinal infusions. After the 0 min sampling, an equal volume of 0.9 % NaCl was infused back into the rat. After centrifugation (2000 g for 6–8 min) and removal of the plasma sample, an equal volume of 0.9 % NaCl was added to the erythrocytes. The blood was returned to the rat after the samplings at 20 and 60 min. Catecholamine concentrations were measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography and fluorescence detection (HLC-725CA, TOSOH, Japan).

Statistics

Data were presented as the mean ±s.e.m. A one-way ANOVA or one-way repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine significant differences. Tukey's post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Involvement of vagal, but not splanchnic, afferents in thermogenesis induced by intestinal infusion of hypertonic NaCl

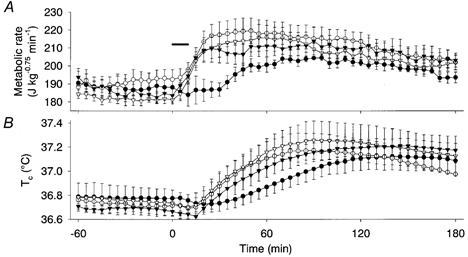

Infusion of 3.6 % NaCl (10 ml kg−1) into the duodenum increased the metabolic rate by 10–20 % of the baseline level for ∼3 h in splanchnic-denervated rats (Fig. 1A). The baseline metabolic rate and the amount and time course of the NaCl-induced increase in metabolic rate were similar to those in control rats (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3A). The Tc of splanchnic-denervated rats increased by 0.43–0.54 °C (Fig. 1B), which was also comparable to the increase in control rats. Tail skin temperature increased by ∼0.5 °C (data not shown) with a time course similar to that of Tc, suggesting that this increase was the result of hyperthermia.

Figure 1. Effects of denervation of vagus or splanchnic nerves, pretreatment with atropine, or capsaicin desensitization on responses to duodenal infusion of hypertonic NaCl.

Metabolic rate (A) and Tc (B) following vagotomy (•, n = 4), splanchnic denervation (▾, n = 4), atropine pretreatment (○, n = 4) and capsaicin desensitization (▿, n = 4). Hypertonic (3.6 %) NaCl was infused into the duodenum at a volume of 10 ml kg−1 for 10 min. The horizontal bar shows the period of NaCl infusion. The metabolic rate of vagotomized rats was significantly lower than other rats at 25–30 min, and the energy expenditure during the first hour was significantly lower in vagotomized rats than in the other groups, although energy expenditure during the 1–3 h period was comparable among all groups. Values are means and vertical bars show s.e.m.

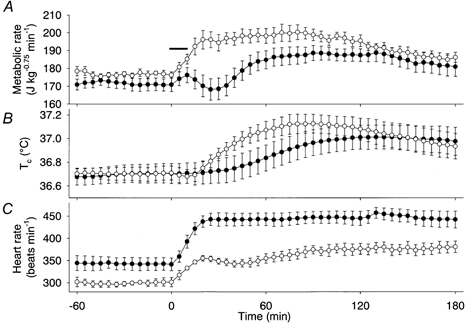

Figure 2. Effects of adrenal demedullation on duodenal hypertonic NaCl-induced responses.

The metabolic rate (A), Tc (B), and heart rate (C)of adrenal-demedullated rats (•, n = 6) and sham-operated control rats (○, n = 5). The metabolic rate of adrenal-medullated rats was significantly lower than that of sham-operated control rats for 20–50 min following infusion of 3.6 % NaCl, and the initial energy expenditure during the first hour in adrenal-demedullated rats was significantly lower than in control rats, although energy expenditure during the 1–3 h period was comparable. The horizontal bar shows the period of NaCl infusion.

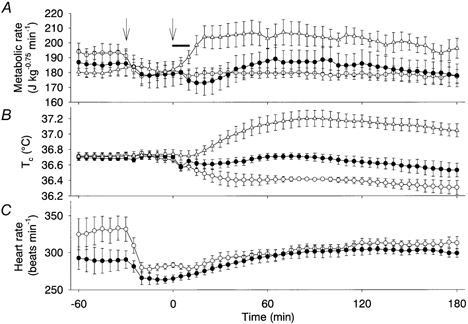

Figure 3. Contribution of β-adrenoceptors to the osmotically induced thermogenesis.

The effect on metabolic rate (A), Tc (B) and heart rate (C) of duodenal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl in propranolol-treated (•, n = 5) and control (▵, n = 5) rats, and 0.9 % NaCl infusion in propranolol-treated rats (○, n = 5). The propranolol-treated rats exhibited a significantly smaller thermogenic response than the control rats. However, propranolol-treated rats expended energy to a significantly higher degree after the 3.6 % NaCl infusion than after the 0.9 % NaCl infusion. Reflecting the changes in metabolic rate, Tc decreased in propanolol-treated rats after infusion of 0.9 % NaCl, but not after infusion of 3.6 % NaCl, and increased in control rats that had been infused with 3.6 % NaCl without administration of propranolol. Administration of propranolol alone significantly decreased the basal heart rate, and the changes in heart rate were similar between rats infused with 0.9 % NaCl and 3.6 % NaCl. We did not record the heart rate of the control group. The arrows show the time of propranolol administration; the horizontal bar shows the period of NaCl infusion.

The baseline metabolic rate of vagotomized rats was similar to that of control rats. However, the vagotomized rats did not show an increase in their metabolic rate until 30 min after the intestinal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl; then the rate slowly increased by ∼20 J kg−0.75 min−1 to a plateau level between 50 and 180 min (Fig. 1A). The energy expenditure for the first hour was 0.22 ± 0.12 kJ kg−0.75, which was significantly lower than that of splanchnic-denervated rats (1.33 ± 0.33 kJ kg−0.75). However, the energy expenditure during the period 1–3 h after infusion was not statistically different between vagotomized and splanchnic-denervated rats. The Tc of the vagotomized rats increased slowly and reached a plateau level of 37.1 °C at 100–180 min, which was comparable to that of control rats.

Vagotomy disrupts both afferent and efferent fibres. Accordingly, atropine (10 mg kg−1) was used to block the transmission of vagal efferents to determine if they were involved in the osmotically induced thermogenesis. However, pretreatment with atropine had no effect on either the magnitude or the time course of the increase in metabolic rate and Tc induced by 3.6 % NaCl (Fig. 1A and B). These results indicate that vagal afferents are critically involved in the initial phase of thermogenesis. We then used capsaicin desensitization to assess the possible involvement of nociceptive afferents. However, capsaicin-desensitized rats showed the increased metabolic rate and Tc after the duodenal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl (Fig. 1A and B).

Involvement of catecholamines and β-adrenoceptors

Adrenal-demedullated rats did not show any significant change in their metabolic rate for 40 min after the duodenal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl, though they had a baseline metabolic rate similar to that of sham-operated control rats (Fig. 2A). The energy expenditure for the first hour was 0.26 ± 0.09 kJ kg−0.75, which was significantly lower than that of control rats (1.06 ± 0.33 kJ kg−0.75). Thereafter, their metabolic rate slowly increased by 20 J kg−0.75 min−1 to a plateau level that was similar to the level in control rats between 120 and 180 min. The Tc of the adrenal-demedullated rats rose slowly but reached a level comparable to that of control rats after 120 min (Fig. 2B).

In this experiment, we simultaneously recorded the heart rate (Fig. 2C) to indirectly assess any possible compensatory action of the sympathetic nervous system and noradrenaline on the osmotically induced thermogenesis. The baseline heart rate of the adrenal-demedullated rats was 342 ± 14 beats min−1, which was significantly higher than that of the control rats (302 ± 10 beats min−1). Moreover, the heart rate of the adrenal-demedullated rats increased promptly to a plateau level of 450 beats min−1 within 20 min, and this level was maintained during the 3 h observation period. The heart rate of control rats increased to an initial small peak of 355 ± 6 beats min−1 at 20 min, and subsequently increased again, remaining elevated until at least 180 min. The difference in heart rate between adrenal-demedullated and control rats was significant throughout the experimental period.

Administration of propranolol (20 mg kg−1) alone significantly decreased the metabolic rate by 10–20 J kg−0.75 min−1, showing a contribution of β-adrenoceptors in the resting metabolic rate of the present preparation, and it greatly attenuated the entire osmotically induced thermogenesis (Fig. 3A). However, although propranolol-treated rats apparently showed similar changes in metabolic rate after administration of 3.6 % or 0.9 % NaCl, the cumulative energy expenditure of rats infused with 3.6 % NaCl (0.63 ± 0.18 kJ kg−0.75) was significantly higher than that of rats infused with 0.9 % NaCl (−0.42 ± 0.39 kJ kg−0.75). The Tc of propranolol-treated rats decreased after the infusion of 0.9 % NaCl but did not change after the infusion of 3.6 % NaCl (Fig. 3B). The tail skin temperature was similar in these two groups of rats (data not shown). The heart rate decreased by 20–50 beats min−1 following administration of propranolol. Thereafter, it increased slowly to the baseline level. These changes in heart rate were similar in rats infused with 0.9 % NaCl and rats infused with 3.6 % NaCl (Fig. 3C).

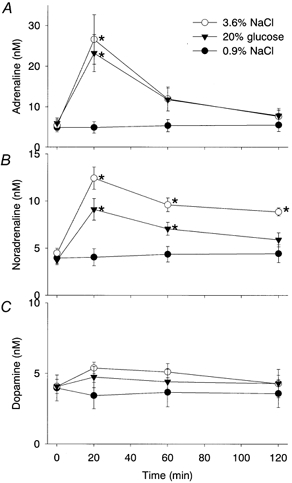

Duodenal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl increased the plasma adrenaline concentration from a baseline level of 5.4 ± 1.3 nm to a peak of 26.6 ± 6.1 nm at 20 min (Fig. 4A). Similarly, infusion of 20 % glucose also increased the plasma adrenaline level at 20 min. However, afterwards the level in each case returned rapidly to the baseline level. On the other hand, the noradrenaline concentration increased significantly at 20 and 60 min after the infusion of 3.6 % NaCl or 20 % glucose, and the increase was still significant in the rats infused with 3.6 % NaCl at 120 min (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the plasma dopamine concentration did not change after the infusions of these solutions (Fig. 4C). The infusion of 0.9 % NaCl had no effect on the plasma level of any of these catecholamines.

Figure 4. Changes in plasma levels of noradrenaline, adrenaline and dopamine after infusion of 3.6 % NaCl, 20 % glucose or 0.9 % NaCl.

Changes in plasma levels of noradrenaline (A), adrenaline (B), and dopamine (C) after infusion of 3.6 % NaCl (○, n = 6), 20 % glucose (▾, n = 6) or 0.9 % NaCl (•, n = 5). A, infusion of 3.6 % NaCl or 20 % glucose, but not 0.9 % NaCl, markedly increased the plasma adrenaline level at 20 min, although the level rapidly returned to basal. B, the plasma noradrenaline level increased after the infusion of either hypertonic solution, and the significant increase lasted for 2 h in the rats infused with 3.6 % NaCl, and for 1 h in the rats infused with 20 % glucose. C, the infusion of neither 3.6 % NaCl nor 20 % glucose had any effect on the plasma level of dopamine. * Significant difference from the corresponding value for the group infused with 0.9 % NaCl.

Lack of participation of the forebrain and prostaglandins

Neither cerebral transection nor suction removal of the forebrain had any effect on the osmotically induced thermogenesis. The energy expenditure for 3 h after the duodenal infusion of 3.6 % NaCl was 3.15 ± 0.36 kJ kg−0.75 (n = 6) in cerebrum-transected rats and was 3.46 ± 0.45 kJ kg−0.75 (n = 5) in forebrain-removed rats. These values were similar to the value for intact rats (3.49 ± 0.33 kJ kg−0.75, n = 5). The tachycardiac and hyperthermic responses were also similar to those found in intact rats.

In rats pretreated with indomethacin (10 mg kg−1), duodenal osmotic stimulation increased the metabolic rate and expended energy to 2.74 ± 0.40 kJ kg−0.75(n = 5), which was not statistically different from that of intact control rats or that of vehicle-treated rats (2.56 ± 0.33 kJ kg−0.75, n = 3). The Tc of indomethacin-pretreated rats increased by 0.41–0.61 °C, which was also similar to that increase seen in control rats.

DISCUSSION

Bilateral subdiaphragmatic vagotomy greatly attenuated the first hour of thermogenesis induced by duodenal infusion of hypertonic NaCl but did not affect the later phase of the thermogenic response. Pretreatment with atropine, which prevents vagal efferent transmission, had no effect on the thermogenesis. Thus, the vagal afferents mediated the initial phase of thermogenesis; however, the vagus nerve did not play a major role in the later phase of thermogenesis. In agreement with this conclusion, the abdominal vagal afferents convey signals that represent information on the feeding state, and they are considered to be involved in the regulation of energy metabolism (Székely, 2000).

We used capsaicin to desensitize polymodal nociceptors, because capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferents are known to mediate suppression of food intake by intestinal nutrients (Yox & Ritter, 1988), and because hypertonic infusions could evoke pain, which might cause stress-related thermogenesis. However, both metabolic rate and Tc of capsaicin-desensitized rats increased normally in response to duodenal osmotic stimulation. Therefore, the vagal afferent fibres insensitive to capsaicin were involved in the metabolic responses.

Vagal afferent units sensitive to osmotic stimulation of the duodenum were reported by Mei & Garnier (1986) and Blackshaw & Grundy (1990). On the other hand, the splanchnic nerves contain mesenteric osmosensitive afferents that modulate vasopressin secretion (Choi-Kwon & Baertschi, 1991). However, the splanchnic afferents were unlikely to be involved in the osmotically induced thermogenesis, because splanchnic denervation caudal to the suprarenal ganglion had no effect in the present study. Such a result also indicates that the sympathetic fibres in the splanchnic nerves had no significant role in thermogenesis, although lesions of adrenal sympathetic nerves attenuated the thermogenic response to duodenal osmotic stimulation (authors' unpublished observation).

The abdominal vagal afferents have been shown to participate in the febrile response to pyrogens, at least in its initiation (Romanovsky, 2000). Fever, regardless of its cause, increases the metabolic rate. Accordingly, there are apparent similarities between fever and hyperthermia elicited by intestinal osmotic stimulation. However, although it has been reported that capsaicin-sensitive neural fibres mediate the initial phase of fever induced by i.v infusion of lipopolysaccharide (Székely et al. 2000), capsaicin desensitization had no effect on the osmotically induced thermogenesis in the present study. Moreover, although prostaglandin E2 is crucially involved in the mechanism of fever (Sehic et al. 1996; Matsumura et al. 1998; Romanovsky et al. 1999), pretreatment with indomethacin, which inhibits biosynthesis of prostaglandins, had no effect on the osmotically induced thermogenesis. Furthermore, decerebration also had no effect, although fever is generally controlled by the hypothalamic thermoregulatory centre. These dissociations suggest that fever and the present osmotically induced thermogenesis are different phenomena.

As with vagotomy, adrenal demedullation also greatly attenuated the first hour of thermogenesis. The plasma adrenaline concentration increased during this period, and the β-adrenoceptor blocker propranolol reduced thermogenesis during the entire period, including the initial phase. These results demonstrate that a vago- sympathoadrenal reflex largely mediated the initial phase of the observed thermogenesis.

The late and long-lasting phase of osmotically induced thermogenesis was almost abolished by pretreatment with propranolol; however, it remained largely unchanged in adrenal-demedullated rats. The plasma concentration of noradrenaline, but not that of adrenaline, was higher than the baseline value for 1–2 h after the osmotic stimulation. The tachycardiac response to osmotic stimulation, particularly exaggerated in the adrenal-demedullated rats, suggests activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Accordingly, the later phase of thermogenesis was mediated mainly by noradrenaline through activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

However, even when rats were pretreated with propranolol, both cumulative heat production and Tc were higher in rats infused with 3.6 % NaCl than in rats infused with 0.9 % NaCl. Because these rats did not show the tachycardiac response, we consider that propranolol blocked the β-adrenoceptors effectively. The results suggest that mechanisms other than those involving β-adrenoceptors also participate in the osmotically induced thermogenesis. Since i.v infusion of hypertonic solutions stimulated skeletal muscle thermogenesis that was independent of β-adrenoceptors (Kobayashi et al. 2001), such a mechanism might have been activated simultaneously in the present experiments.

The lack of effect of decerebration on the osmotically induced thermogenesis clearly demonstrates that the forebrain made no significant contribution to this response, although this part of the brain contains osmosensitive neurons and integrates osmotic and various homeostatic functions. The hindbrain structures (medulla oblongata and pons) and midbrain, which control the autonomic nervous system, were intact in this preparation. These structures receive vagal afferents and contain premotor areas of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord (Strack et al. 1989). Osmosensitive neurons also exist in the medulla oblongata (Kobashi & Adachi, 1985). Accordingly, we consider that the hindbrain mediated thermogenesis without significant modulation by the forebrain. Similar to the present observation, systemic administration of capsaicin elicited thermogenesis in decerebrated, but not in spinalized, rats (Osaka et al. 2000).

In the present study, we have delineated the neural mechanisms of thermogenesis elicited by the duodenal infusion of hypertonic solutions. The Vago–sympathoadrenal reflex contributed largely to the initial phase of this thermogenesis. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system and noradrenaline contributed mainly to the later phase of the thermogenesis. However, the critical locus that mediates the osmotically induced thermogenesis in the hindbrain, and the osmosensitive structures responsible for the later phase of thermogenesis, remain to be identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Akira Niijima for his guidance on the innervation of upper abdominal organs. This study was supported by grants for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (no. 12670075) and from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (no. KH51059).

REFERENCES

- Acheson K, Jéquier E, Wahren J. Influence of β-adrenergic blockade on glucose-induced thermogenesis in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1983;72:981–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI111070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud HR, Jeanrenaud B. Sham feeding-induced cephalic phase insulin release in the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;242:E280–285. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1982.242.4.E280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw LA, Grundy D. Effects of cholecystokinin (CCK-8) on two classes of gastroduodenal vagal afferent fibre. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1990;31:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90185-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi-Kwon S, Baertschi AJ. Splanchnic osmosensation and vasopressin: mechanisms and neural pathways. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:E18–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.1.E18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gõbel Gy, Ember Á, Pétervári E, Kis A, Székely M. Postalimentary hyperthermia: a role for gastrointestinal but not for caloric signals. Journal of Thermal Biology. 2001;26:519–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Yamatodani A, Imamura K, Noguchi T, Tanaka T. The role of the autonomic nervous system in the thermic effects of protein and carbohydrates in rats. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 1994;40:523–534. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.40.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashi M, Adachi A. Convergence of hepatic osmoreceptive inputs on sodium-responsive units within the nucleus of the solitary tract of the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1985;54:212–219. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Osaka T, Inoue S, Kimura S. Thermogenesis induced by intravenous infusion of hypertonic solutions in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 2001;535:601–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Osaka T, Namba Y, Inoue S, Lee TH, Kimura S. Capsaicin activates heat loss and heat production simultaneously and independently in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:R92–98. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurpad AV, Khan K, Calder AG, Elia M. Muscle and whole body metabolism after norepinephrine. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:E877–884. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.6.E877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K, Cao C, Watanabe Y, Watanabe Y. Prostaglandin system in the brain: sites of biosynthesis and sites of action under normal and hyperthermic states. Progress in Brain Research. 1998;115:275–295. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei N, Garnier L. Osmosensitive vagal receptors in the small intestine of the cat. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1986;16:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(86)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T, Kobayashi A, Inoue S. Thermogenesis induced by osmotic stimulation of the intestines in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 2001;532:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0261g.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T, Kobayashi A, Lee TH, Namba Y, Inoue S, Kimura S. Lack of integrative control of heat production and heat loss after capsaicin administration. Pflügers Archiv. 2000;440:440–445. doi: 10.1007/s004240000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T, Yoshimatsu H, Kannan H, Yamashita H. Activity of hypothalamic neurons in conscious rats decreased by hyperbaric environment. Brain Research Bulletin. 1989;22:549–555. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky AA. Thermoregulatory manifestations of systemic inflammation: lessons from vagotomy. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2000;85:39–48. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky AA, Ivanov AI, Karman EK. Blood-bone, albumin-bound prostaglandin E2 may be involved in fever. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:R1840–1844. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.6.R1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehic E, Székely M, Ungar AL, Oladehin A, Blatteis CM. Hypothalamic prostaglandin E2 during lipopolysaccharide-induced fever in guinea pigs. Brain Research Bulletin. 1996;39:391–399. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Platt KB, Loewy AD. CNS cell groups regulating the sympathetic outflow to adrenal gland as revealed by transneuronal cell body labeling with pseudorabies virus. Brain Research. 1989;491:274–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Székely M. The vagus nerve in thermoregulation and energy metabolism. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2000;85:26–38. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Székely M, Balaskó M, Kulchitsky VA, Simons CT, Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Multiple neural mechanisms of fever. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2000;85:78–82. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00223-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waynforth HB, Flecknell PA. Experimental and Surgical Technique in the Rat. London: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yox DP, Ritter RC. Capsaicin attenuates suppression of sham feeding induced by intestinal nutrients. American Journal of Physiology. 1988;255:R569–574. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.4.R569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]