Abstract

As a neurohormone and as a neurotransmitter, oxytocin has been implicated in the stress response. Descending oxytocin-containing fibres project to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, an area important for processing nociceptive inputs. Here we tested the hypothesis that oxytocin plays a role in stress-induced analgesia and modulates spinal sensory transmission. Mice lacking oxytocin exhibited significantly reduced stress-induced antinociception following both cold-swim (10 °C, 3 min) and restraint stress (30 min). In contrast, the mice exhibited normal behavioural responses to thermal and mechanical noxious stimuli and morphine-induced antinociception. In wild-type mice, intrathecal injection of the oxytocin antagonist dOVT (200 μm in 5 μl) significantly attenuated antinociception induced by cold-swim. Immunocytochemical staining revealed that, in the mouse, oxytocin-containing neurones in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus are activated by stress. Furthermore, oxytocin-containing fibres were present in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. To test whether descending oxytocin-containing fibres could alter nociceptive transmission, we performed intracellular recordings of dorsal horn neurones in spinal slices from adult mice. Bath application of oxytocin (1 and 10 μm) inhibited excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) evoked by dorsal root stimulation. This effect was reversed by the oxytocin antagonist dOVT (1 μm). Whole-cell recordings of dorsal horn neurones in postnatal rat slices revealed that the effect of oxytocin could be blocked by the addition of GTP-γ-S to the recording pipette, suggesting activation of postsynaptic oxytocin receptors. We conclude that oxytocin is important for both cold-swim and restraint stress-induced antinociception, acting by inhibiting glutamatergic spinal sensory transmission.

Oxytocin is a neuropeptide synthesized in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and supraoptic nucleus (SON) of the hypothalamus. Oxytocin plays a major neuroendocrine role, modulating diverse physiological functions in mammals such as parturition, lactation, affiliative behaviour and social memory (Pederson et al. 1992; Brussaard et al. 1997; Russell & Leng, 1998). Genetically manipulated mice lacking oxytocin exhibit a defect in the milk ejection reflex and social amnesia, whereas other reproductive behaviours are normal in both males and females (Nishimori et al. 1996; Young et al. 1996; Gross et al. 1998; Ferguson et al. 2000). In addition to being a classical neurohormone, oxytocin plays a role as a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator in the central nervous system (Hatton, 1990: Armstrong, 1995; Kombian et al. 1997).

Interestingly, oxytocin has also been implicated in modulation of somatosensory transmission, such as nociception and pain (Uvnas-Moberg et al. 1992; Arletti et al. 1993; Lundeberg et al. 1994). Oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN send descending axons to the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Sawchenko & Swanson, 1982). Neurones in the superficial dorsal horn are important for conveying sensory information from the periphery to the central nervous system as well as for the central regulation of somatosensory function. Studies involving systemic, intracerebral or intracisternal injections of oxytocin have suggested that oxytocin could be antinociceptive or analgesic (Uvnas-Moberg et al. 1992; Arletti et al. 1993; Lundeberg et al. 1994; but see Xu & Wiesenfeld-Hallin, 1994). Finally, electrical stimulation of the PVN induces antinociception in both normal and arthritic rats (Kupers et al. 1988; Yirmiya et al. 1990).

Oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN are activated during different stressful conditions, as indicated by changes in immediate early gene expression in this region (Ceccatelli et al. 1989; Hatakeyama et al. 1996). Antinociceptive effects caused by stress have been well documented in both rats and mice (Hayes et al. 1978; Porro & Carli, 1988; Mogil et al. 1996). Lesions of the PVN reduce stress-induced antinociception of the spinal nociceptive tail-flick reflex (Truesdell & Bodnar, 1987), which suggests that oxytocin could participate in stress-induced analgesia.

Because of the limited selectivity of brain lesions and electrical stimulation, these previous studies have not directly addressed the involvement of oxytocin in stress-induced analgesia. In addition, the cellular mechanisms of antinociceptive or analgesic effects remain unclear. Taking advantage of genetically manipulated mice in which the oxytocin gene has been deleted, we employed both in vivo animal behavioural assays as well as in vitro spinal slice preparations to investigate: (1) the role of oxytocin in stress-induced antinociception; and (2) a spinal mechanism for oxytocin-produced antinociception.

METHODS

Generation of oxytocin-knockout mice

Agouti pups heterozygous for the mutated oxytocin-knockout allele (Gross et al. 1998) were bred to generate homozygous deficient mice and wild-type controls of the same genetic background (mixed 129/Sv × Black Swiss) for these experiments, as well as heterozygotes for subsequent strain propagation. The adult male mice used in these studies were housed on a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle with ad libitum access to rodent chow. All mouse protocols were in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University School of Medicine.

Stress and behavioural nociceptive tests

All tests were performed in male wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice 8–12 weeks of age, as previously described (Zhuo, 1998). The tail-flick and hot-plate tests measure the latency of the animal's response to noxious heat. Different temperatures (52.5 or 55.0 °C) were used in the hot-plate test to detect possible threshold-related differences between mutant and wild-type mice. Unlike the hot-plate test, where the plate temperature can be precisely controlled, radiant heat was used to elicit the tail-flick. The tail-flick was tested for two different current intensities heating the lamp. The skin temperature at the heated site of the tail or hindpaw was measured using a digital thermometer with a small probe (∼1.5 mm in diameter). It usually took a few seconds for the peak to be reached. The probe was held for another 5 s to assure the accuracy of the reading. Withdrawal to mechanical pressure on the tail by von-Frey filaments was used to measure non-thermal nociception. Filaments of different thickness, requiring different pressures to bow the filament (12.5–446.7 g), were applied sequentially until the tail was reflexively withdrawn: the pressure at which this occurred was taken to be the nociceptive mechanical (pressure) withdrawal threshold.

To induce stress, the mice were forced to swim in water at 10 °C for 3 min or were restrained for 30 min. Small cylindrical containers, with a diameter slightly larger than a mouse's body, were used for restraint. Responses to hot-plate and tail-flick were measured again following stress. In some experiments, the oxytocin receptor antagonist d(CH2)5-Tyr(Me)-[Orn8]-vasotocin (dOVT, 100 ng; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was injected intrathecally at the lower lumbar level, as described previously (Zhuo, 1998), 7 min before cold-swim stress. The dose of dOVT used was selected based on previous behavioural studies using spinal administration of oxytocin and related peptides (Millan et al. 1984; Lundeberg et al. 1994). During intrathecal injection, mice were anaesthetized with halothane (2 %). Injections (5 μl) were made with the steel tip of a 30 gauge needle connected via a 1 ft length of flexible PE-10 tubing to a 50 μl syringe. Saline was used as a control. After the injection, the animals took 2–3 min to recover.

All experiments were undertaken blind. Data are presented as mean response latency (s) or maximum possible inhibition (MPI = (response latency - baseline response latency)/(cut-off time - baseline response latency) × 100). To represent the total effect of stress over time, the area under the curve (MPI versus time) was used.

Immunocytochemistry

One hour after cold-swim, adult knockout and wild-type mice were deeply anaesthetized with halothane and perfused transcardially with 50 ml saline followed by 200 ml of cold (4 °C) 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB) containing 4 % paraformaldehyde. Cryostat-cut brain and lumbar spinal cord sections (30 μm) were immunocytochemically processed with mouse anti-c-Fos monoclonal antibody (1:100, Oncogene, Uniondale, NY, USA) or rabbit anti-oxytocin antibody (1:1000, Rohto Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan). Secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescent markers FITC (1:50, used with c-Fos) and Cy-3 (1:600, used with oxytocin, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) were used. Vasopressin staining was performed as previously described (Muglia et al. 1995). Some sections were processed for double staining by the conventional horseradish peroxidase (HRP) method. Briefly, after being incubated with both mouse anti-Fos antibody (1:500) and rabbit anti-oxytocin antibody (1:2000) overnight, the sections were then processed with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) followed by avidin-biotin- peroxidase complex (1:400; Vector Laboratories). The Fos staining was visualized by using the glucose-oxidase diaminobenzidine (DAB)-nickel method. After being rinsed several times in PBS, these sections were placed in goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:50; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) and then rabbit peroxidase anti-peroxidase (1:500; Chemicon). The bound peroxidase was identified by DAB reaction without nickel, showing brown reaction products for oxytocin immunoreactivity. Finally, sections were mounted, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared with xylene and coverslipped. Fluorescence images of brain and spinal cord sections were obtained with Olympus Fluoview (version 1.2) laser-scanning confocal fluorescence-imaging system. In order to view the distribution of oxytocin-containing terminals in the spinal cord, we generated a collapsed view of several confocal planes covering a depth of ∼27 μm (Gan et al. 2000).

Intracellular recordings from adult mouse spinal cord

Transverse lumbar spinal cord slices, 450–500 μm with 7–12 mm dorsal root, were obtained from male adult mice (8–10 weeks old), using previously described techniques (Kerchner et al. 2001). Mice were deeply anaesthetized with halothane and then cooled on ice for 10 min. The lumbar spinal cord was exposed, and ice-cold physiological saline (mm: NaCl 113, KCl 3, NaHCO3 25, NaH2PO3 1, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and d-glucose 25; equilibrated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2, pH 7.3) was poured over it to cool the spinal cord. A segment of lumbar spinal cord was quickly removed and immersed in oxygenated, ice-cold saline for 3 min or more. The dura was removed and 450–500 μm thick slices were cut with a vibratome. The slices were kept for a minimum of 2 h in a filtering funnel filled with oxygenated saline at room temperature.

Intracellular recordings of synaptic responses were performed from neurones located in the dorsal horn lamina I and II with 3 m potassium chloride-filled glass microelectrodes (DC impedance, 75–200 MΩ). Synaptic responses were elicited by electrical stimulation of the dorsal roots with a bipolar electrode. Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) were evoked by electrical stimulation at different intensities (stimulus width, 0.2 ms), and recorded through the high-input impedance bridge circuit of the amplifier (Intracellular Electrometer IE 210, Warner instrument Corporation, Hamden, CT, USA). Paired-pulse facilitation was tested using two pulses at a 50 ms interval. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). The perfusing medium (mm: NaCl 124, KCl 4, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1, MgSO4 1, CaCl2 2, glucose 10) was oxygenated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. The temperature and perfusion rate of the recording solution were kept at 34 °C and 2–5 ml min−1, respectively.

Whole-cell patch clamp

Transverse lumbar spinal cord slices, 150–200 μm thick, were obtained from rats on postnatal days 4–12, as described above and previously (Li & Zhuo, 1998). Rats were deeply anaesthetized with halothane. Whole-cell recordings were made using 5–10 MΩ electrodes without fire polishing. Recording electrodes contained (mm): caesium methanesulphonate 110, MgCl2 5, EGTA 1, Na-Hepes 40, Mg-ATP 2, Na3-GTP 0.1 (pH 7.2). The osmolarity was adjusted to 295–300 mosmol l−1. Membrane potential was clamped at 70 mV (liquid junction potential not corrected). Series resistance was 15–40 MΩ and was monitored throughout the experiments. Postsynaptic excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were evoked at 0.05 Hz with a bipolar tungsten electrode (stimulus width, 0.1 ms) placed at the dorsal root entry zone or dorsal root nerve. Monosynaptic EPSCs were identified using two criteria: the response latency did not change with increasingly intense electrical stimulation, and EPSCs followed high-frequency stimulation (50 Hz) with reduced amplitude and without changing response latency. Only monosynaptic EPSCs were used in the present study. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Bicuculline methiodide (10 μm) and strychnine hydrochloride (1 μm) were added to the perfusion solution.

To determine the involvement of postsynaptic oxytocin receptors, in some experiments we added the irreversible G protein activator guanosine 5′-O-3-thiotriphosphate (GTP-γ-S; 0.5 mm) to the intracellular solution to inhibit the postsynaptic oxytocin receptor pathway. We have reported previously that 0.5 mm GTP-γ-S inhibited the modulatory effects induced by a cholinergic (carbachol) or serotonergic (serotonin) receptor agonist (Azpiazu et al. 1999; Li & Zhuo, 2001). All compounds were from RBI or Sigma (both in St Louis, MO, USA).

In situ hybridization and Western blotting

In situ hybridization

Lumbar spinal cord fragments from P4 rats or adult mice were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN, USA), then frozen in dry ice for sectioning on a cryostat. Ten-micron sections were thaw-mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and hybridized to an α-33P-UTP-labelled 800 base oxytocin receptor antisense riboprobe. After hybridization and washes, sections were exposed to Hyperfilm β-Max (Amersham Life Sciences Inc., Arlington Heights, IL, USA) for localization of radiolabelled cells.

Western blot analysis

Cell membrane protein extracts from lumbar spinal cords of oxytocin-knockout and wild-type mice were prepared by sonication in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mm NaCl, 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A, 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 200 μm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. The supernatant formed after centrifugation at 800 g for 20 min at 4 °C was subjected to centrifugation at 46 000 g for 2 h at 4 °C. The subsequent pellet containing membrane proteins was resuspended in 100 mm Na2CO3, pH 11.5, 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A, 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 200 μm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting suspension was subjected to a second centrifugation at 46 000 g for 2 h at 4 °C, followed by resuspension of the pellet in 10 mm Hepes-potassium hydroxide, pH 7.5, 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin A, 2 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 5 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 200 μm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. Twenty microgram aliquots of the extracts were subjected to 10 % SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The anti-oxytocin receptor monoclonal antibody O-2F8 (Takemura et al. 1994) at 1 μg ml−1 (Rohto Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Japan), diluted in 0.44 m sodium chloride, 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 3 mm potassium chloride, 0.1 % Tween-20, 5 % non-fat dry milk, was used to detect oxytocin receptors, with visualization using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Life Sciences) followed by exposure to BioMax film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA). Equivalent protein loading and transfer was confirmed by Ponceau S staining of the membrane.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated from hypothalami and dorsal root ganglia of adult mice using TRIzol (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Two micrograms of RNA were used as a template for cDNA synthesis by Moloney Murine Leukaemia Virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) initiated from random hexamer primers in a reaction volume of 20 μl. PCR amplification of this cDNA for detection of oxytocin expression was performed using a sense strand primer from exon 1 of the mouse oxytocin gene (5′-TTG CTG CCT GCT TGG CTT AC-3′) and a reverse strand primer from exon 3 (5′-TAT TCC CAG AAA GTG GGC TC-3′). To control for RNA recovery and integrity, primers for the neurone-specific microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2) mRNA were also included in each reaction, as previously described (Fontan et al. 2000). Amplification of cDNA encoding oxytocin and MAP-2 results in PCR products of 376 and 189 bp, respectively. Samples were denatured at 96 °C for 3 min, followed by 26 cycles of 95 °C for 60 s, 55 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 4 min. Reactions were completed with the final extension for 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were electrophoresed through 1.5 % agarose and visualized with ethidium bromide.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, Dunnett test for post hoc comparison) or Student's t test. Data are presented as the mean value ± 1 s.e.m.P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

General behavioural observations and acute nociception

The strain of oxytocin-knockout mice used in these studies (Gross et al. 1998) arose from deletion of the entire oxytocin-neurophysin I coding region, and demonstrates appropriate expression of the adjacent vasopressin gene (C. E. Luedke & L. J. Muglia, unpublished data; see also Fig. 5B). No obvious behavioural difference was apparent between wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice.

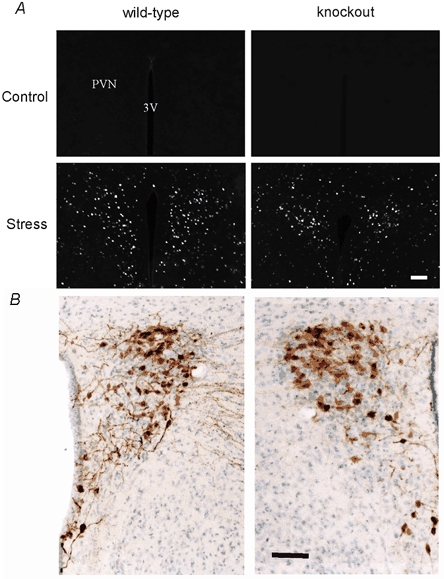

Figure 5. c-Fos activation by cold-swim stress in oxytocin-knockout and wild-type mice.

A, c-Fos expression in coronal sections of the PVN region of both wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice 1 h after cold-swim (Stress) or sham processing (Control). B, vasopressin immunoreactivity and Cresyl violet staining of coronal sections of the PVN region of both wild-type and knockout mice. Scale bars, 100 μm.

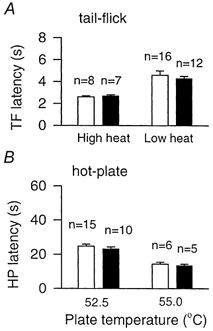

First, we examined the behavioural responses to acute noxious thermal or mechanical stimuli in both wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice using three different behavioural tests. No significant difference was detected in either the spinal nociceptive tail-flick reflex at two different heating intensities (n = 7–16 mice; Fig. 1A) or tail mechanical withdrawal threshold (wild-type, n = 6; 49.5 ± 3.4 g; knockout, n = 6; 50.8 ± 3.5 g). Responses to noxious heat were also tested with the hot-plate at two different intensities (55 and 52.5 °C), since different sets of transmitters may be involved in the response to moderate and high heat intensities (Cao et al. 1998). As shown in Fig. 1B, knockout and wild-type mice responded similarly (n = 5–15).

Figure 1. Nociception in oxytocin-knockout and wild-type mice.

Responses to acute noxious stimulation, as measured by the response latency of the tail-flick at two different heating intensities (A) and on the hot-plate at two different temperatures (55 and 52.5 °C, B), did not differ between wild-type (□) and oxytocin-knockout (▪) mice. Error bars represent s.e.m.

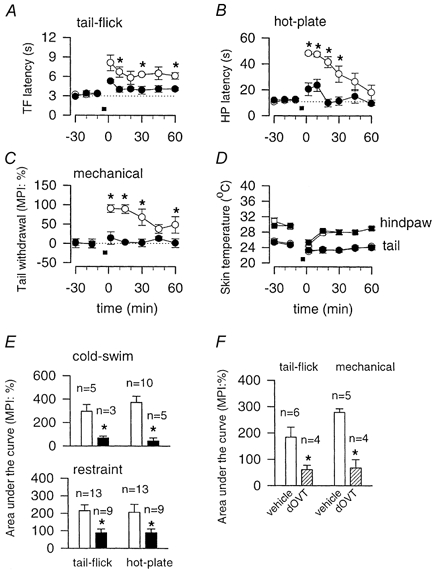

Lack of stress-induced antinociception in mice lacking oxytocin

We next tested whether oxytocin is required for stress-induced antinociception. Consistent with previous reports (Mogil et al. 1996), cold-swim (10 °C, 3 min) induced significant antinociceptive effects in the tail-flick, hot-plate and tail mechanical withdrawal tests in wild-type mice (n = 4–10; Fig. 2A–C). Oxytocin-knockout mice exhibited a drastically reduced stress-induced antinociceptive effect in all three tests (n = 3–5; P < 0.05 for each case). To ensure that this finding was not due to altered thermoregulation, we measured the skin temperature of both the tail and the hindpaw before and after swim-stress and found no significant difference between wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice (n = 4; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Antinociception in oxytocin-knockout and wild-type mice.

A-C, time course of antinociception induced by cold-swim (10 °C, 3 min; indicated by the filled horizontal bar) as measured by tail-flick (A), hot-plate (55 °C, B) and tail mechanical withdrawal (C) for wild-type (○) and oxytocin-knockout (•) mice. D, skin temperatures for the hindpaw (wild-type, □; knockout, ▪) and tail (wild-type, ○; knockout, •) were not significantly different between wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice. E, antinociceptive effect presented as area under the curve between 0 and 60 min after cold-swim or restraint stress. In both cases, oxytocin-knockout mice (▪) exhibited significantly less stress-induced analgesia compared with wild-type mice (□). F, antinociceptive effect presented as area under the curve between 0 and 30 min after cold-swim stress. Intrathecal injection of the oxytocin receptor antagonist dOVT significantly decreased the antinociceptive effect in wild-type mice. In control groups, animals received the same volume of vehicle injection. In all panels, error bars represent s.e.m.; *P < 0.05.

To test whether similar results could be obtained with another type of stress, we measured behavioural nociceptive responses in both the tail-flick and hot-plate tests following restraint stress (30 min), which is known to activate oxytocin-containing neurones in the hypothalamus (Ceccatelli et al. 1989; Hatakeyama et al. 1996). Again, wild-type mice demonstrated significantly greater stress-induced antinociception than oxytocin-knockout mice (n = 9–13, P < 0.05; Fig. 2E). These results consistently indicate that oxytocin is critical for stress-induced antinociception.

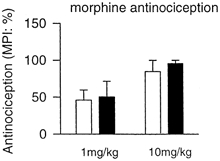

Cold-swim stress at 10 °C (3 min) is thought to be independent of opiate receptors (Mogil et al. 1996). In agreement, we found that cold-swim-induced antinociception for both tail-flick and hot-plate tests was not significantly affected by intraperitoneal injection of the opiate receptor antagonist naloxone (10 mg kg−1, n = 4; data not shown). We tested whether morphine-produced antinociception was also affected in oxytocin-knockout mice. Behavioural antinociception was evaluated following intraperitoneal injection of morphine at two different doses (1 and 10 mg kg−1; n = 4 for each case) in wild-type and knockout mice. No significant difference was found (Fig. 3). These results suggest that oxytocin is selectively required for stress-induced but not morphine-induced antinociception.

Figure 3. Morphine-induced antinociception in oxytocin-knockout and wild-type mice.

Morphine-induced antinociception in the hot plate test at two different doses (1 and 10 mg kg−1). □, wild-type mice; ▪, knockout mice. Error bars represent s.e.m.

Finally, we tested whether intrathecal administration of the oxytocin receptor antagonist dOVT (200 μm in 5 μl) affected swim-stress-induced antinociception. As shown in Fig. 2F, in both tail-flick and tail mechanical withdrawal tests, the antinociceptive effects were significantly reduced in wild-type mice intrathecally injected with dOVT (n = 4), compared with those injected with vehicle (n = 5–6; Fig. 2F).

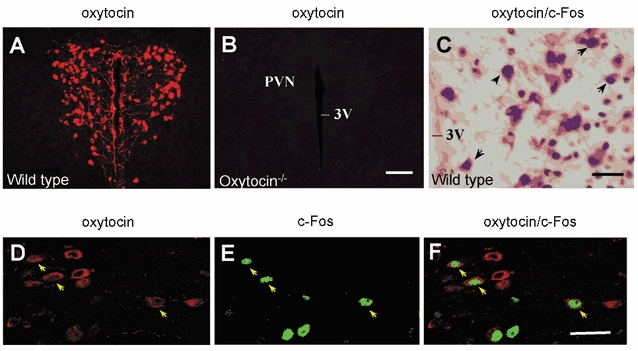

Activation of oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN

To establish whether oxytocin-containing hypothalamic neurones are activated during stress in mice, we examined the expression of c-Fos protein in the brain of wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice following cold-swim. In wild-type mice, cold-swim activated c-Fos expression in hypothalamic neurones, including magno- and parvo-cellular oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN (Fig. 4). As expected, c-Fos-positive cells not demonstrating oxytocin immunoreactivity were also found. These probably represent corticotropin-releasing hormone-expressing parvocellular neurones, which are known to be activated during stress. A similar pattern of c-Fos staining was seen in the knockout mice, with strong c-Fos expression in the PVN following cold-swim (Fig. 5A). A slight decrease in the number of c-Fos-positive cells per section was apparent (86.8 ± 3.4 in wild-type vs. 69.8 ± 5.5 in knockout mice, P < 0.05). Whether this represented the loss of oxytocin-containing neurones or slight alterations in descending modulation is not known. No gross anatomical difference between the hypothalamus of knockout and wild-type mice was apparent (Fig. 5B). Expression of vasopressin was also similar (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4. Stress-induced activation of oxytocin-containing neurones in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus.

A and B, immunofluorescence images showing the distribution of oxytocin immunoreactivity in the PVN of wild-type (A) and oxytocin-knockout (B) mice. The images were obtained from 30 μm thick tissue sections. C, double-labelling visualized with horseradish peroxidase in a 30 μm thick tissue section from a wild-type mouse, 1 h after cold-swim stress. Some neurones (indicated by arrows) in the PVN show cytoplasmic oxytocin immunostaining (brown) and nuclear c-Fos expression (dark blue). D-F, confocal images of the PVN neurones. Arrows indicate neurones with colocalized oxytocin (red) and c-Fos (green) immunoreactivity. These images are from optical sections (at 1.5 μm intervals) of wild-type mouse. Abbreviations: PVN, paraventricular nucleus; 3V, third ventricle. Scale bars: 100 μm (A and B), 30 μm (C-F).

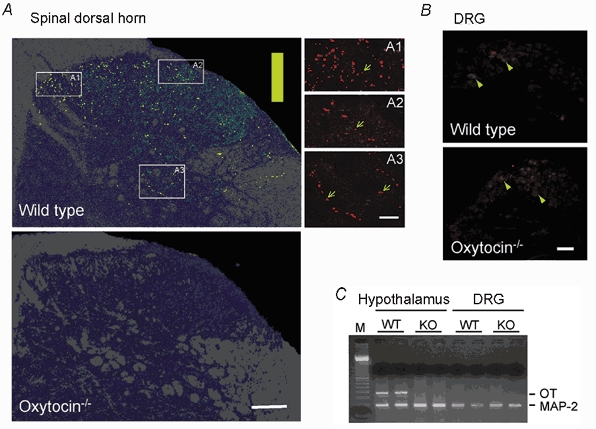

Cold-swim induced similar amounts of c-Fos expression in the spinal dorsal horn of wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice (32.3 ± 3.1 in wild-type vs. 38.0 ± 3.0 in knockout mice). We found a wide distribution of oxytocin-positive fibres and varicosities in the lumbar dorsal horn, lamina X and the dorsolateral funiculus of the spinal cord of wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). No oxytocin immunoreactivity was seen in the hypothalamus (Fig. 4B) or spinal cord (Fig. 6A) of oxytocin-knockout mice.

Figure 6. Distribution of oxytocin immunoreactivity in spinal dorsal horn.

A, distribution of oxytocin-labelled fibres in spinal dorsal horn of wild-type (top) and oxytocin-knockout (bottom) mice. The images represent a collapsed view of nine confocal optical planes covering 27 μm of depth. Immunostaining intensity is shown using a pseudo colour scale: from low (green) to high intensity (yellow) on a background of grey matter (dark blue) and white matter (grey). A1–3 correspond to high-magnification views of the areas outlined; oxytocin-positive fibres and varicosities are shown (arrows). B, weak immunostaining for oxytocin (red) is present in the lumbar dorsal root ganglion of both wild-type and knockout mice (arrowheads). C, lack of oxytocin mRNA expression in dorsal root ganglia in the mouse. Hypothalamic and DRG RNA was subjected to reverse transcription-PCR analysis for detection of oxytocin (OT) and MAP-2 mRNA expression. As expected, robust amplification of oxytocin sequences occurred in wild-type (WT) hypothalamus but not in oxytocin-knockout (KO) hypothalamus. No oxytocin mRNA-specific amplification product was produced from DRG RNA of either wild-type or oxytocin-knockout mice. All samples yielded the 189 bp MAP-2 product, confirming RNA integrity and the presence of neuronal tissue. M, 100 bp ladder marker. Scale bars: 100 μm (A), 25 μm (A1–3), 200 μm (B).

A previous report showed that many of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells in adult rats could be positively labelled by an oxytocin antibody (Kai-Kai et al. 1986). We obtained similar, low-level staining in mouse DRG cells (Fig. 6B). However, low-level staining was also found in our oxytocin-knockout mice, which lack all oxytocin- neurophysin I coding sequences (Fig. 6B). To further confirm that the oxytocin-like immunoreactivity observed in the DRG was not due to bona fide oxytocin production, we performed reverse transcription-PCR analysis of mouse DRG RNA. In contrast to wild-type hypothalamic RNA, wild-type DRG RNA did not yield a product consistent with amplification of oxytocin mRNA (Fig. 6C). We conclude that oxytocin is not synthesized in DRG neurones in the mouse and that the oxytocin antibody may weakly, non-selectively label other neurophysin-related proteins in DRG neurones.

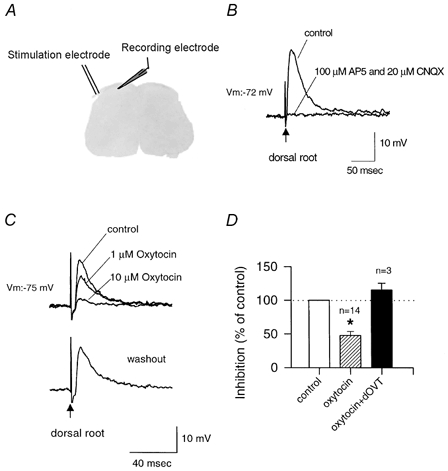

Oxytocin inhibits sensory synaptic transmission between primary afferent fibres and dorsal horn neurones in adult mice

What cellular mechanisms could explain the analgesic defect in the oxytocin-knockout mice? Oxytocin-containing neurones in the SON do not send descending projecting fibres to the spinal cord, but oxytocin-containing fibres from the PVN form axodendritic contacts with dorsal horn neurones (Rousselot et al. 1990).

To test whether oxytocin could modulate synaptic transmission in the dorsal horn, we used conventional intracellular recordings from lumbar dorsal horn neurones of adult wild-type mice. EPSPs were induced by direct stimulation of dorsal root nerves and were completely blocked by bath application of the glutamate AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; 20 μm) and the NMDA receptor antagonist amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP-5; 100 μm; n = 25; see Fig. 7B for an example). Bath application of oxytocin produced a dose-related, reversible inhibition of glutamatergic EPSPs (1–10 μm; Fig. 7C). At a concentration of 1 μm, oxytocin produced a mean inhibition of EPSPs of 20.4 ± 1.5 % (n = 3). Oxytocin at 10 μm produced a greater inhibition of the responses (47.7 ± 6.0 % of control, n = 14). Oxytocin at a concentration of 10 μm produced inhibitory effects in all neurones tested (from 8.3 to 82.5 % inhibition). The selective oxytocin receptor antagonist dOVT (1 μm) prevented the inhibition by oxytocin (10 μm; 115.3 ± 10.1 % of baseline with dOVT, n = 3), indicating that the inhibitory effect was mediated by oxytocin receptors (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7. Regulation by oxytocin of sensory synaptic responses in adult mouse spinal cord slices.

A, schema of intracellular recording from superficial dorsal horn neurones in a spinal cord slice from adult mice. Stimulation of the dorsal root activated the primary afferents and evoked responses in dorsal horn neurones, mimicking sensory stimulation. B, fast EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root (arrow) were completely blocked by bath application of the glutamate receptor antagonists AP-5 (NMDA receptor blocker) and CNQX (AMPA/kainate receptor blocker). C, inhibition of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root (arrow) during bath application of oxytocin (1 or 10 μm). This effect was reversed following washout of oxytocin. D, summary histogram of these experiments illustrating EPSP amplitude as a percentage of the control during application of oxytocin (10 μm) alone (47.7 ± 6.0 % of control) or in the presence of its specific antagonist dOVT (1 μm; 115.3 ± 10.1 % of control). Error bars represent s.e.m.; *P < 0.05.

We also tested the effect of oxytocin on paired-pulse facilitation, a simple form of synaptic plasticity. Application of oxytocin inhibited the first responses, and was without effect on the ratio of the paired-pulse responses (50 ms interval, n = 7; 93.6 ± 20.6 % of baseline paired-pulse ratio). Oxytocin application did not significantly affect the resting membrane potential of dorsal horn neurones (n = 12; −80.3 ± 2.3 mV before and −78.7 ± 2.4 mV after 10 μm oxytocin).

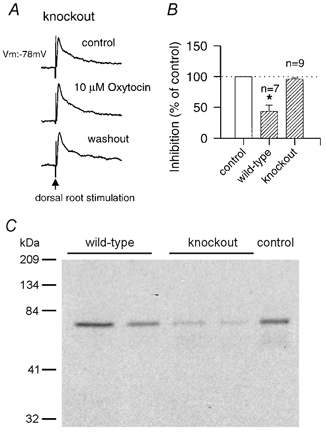

The effect of oxytocin was also tested in slices from oxytocin-knockout mice. Resting membrane potentials of dorsal horn neurones in slices from oxytocin-knockout mice (n = 22; −83.5 ± 1.5 mV) were not significantly different from those in slices from wild-type mice (n = 12; −80.3 ± 2.3 mV). EPSPs evoked by stimulation of primary afferent fibres also showed no significant difference between knockout and wild-type mice (see Fig. 8 for an example). Surprisingly, bath application of oxytocin (10 μm) failed to induce significant inhibition in slices from oxytocin-knockout mice (n = 9; 95.9 ± 2.0 % of control; Fig. 8B). To test whether oxytocin receptors in the spinal cord may be altered or reduced in knockout mice, we performed Western blot analysis of receptors in both wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice. The amount of oxytocin receptor was reproducibly decreased in knockout mice (2 mice per group; Fig. 8C), consistent with the lack of effect of oxytocin application.

Figure 8. Oxytocin and spinal sensory transmission in oxytocin-knockout mice.

A, representative traces of EPSPs evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root (arrow) in an oxytocin-knockout mouse, before, during and after bath application of oxytocin (10 μm). B, summary histogram of these experiments illustrating EPSP amplitude in response to oxytocin (10 μm) in wild-type and knockout mice as a percentage of the control. Error bars represent s.e.m.; *P < 0.05. C, Western blot for oxytocin receptor in the spinal cord. The amount of oxytocin receptor in the spinal cord of two wild-type and oxytocin-knockout mice is shown. The control represents the size of the oxytocin receptor from the mouse uterus.

Postsynaptic oxytocin receptors mediate inhibitory effects

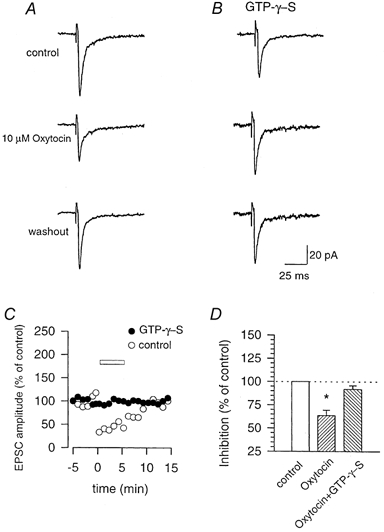

In order to examine whether oxytocin was acting presynaptically or postsynaptically, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed from dorsal horn neurones. Spinal slices from postnatal rats were used to obtain consistent patch-clamp recordings. First, similar to results for adult rats (Reiter et al. 1994), in situ hybridization for oxytocin receptor mRNA revealed the presence of oxytocin receptors in the superficial dorsal horn of the lumbar spinal cord in the young rat as well as the adult mouse (data not shown). As in slices from adult mice, bath application of oxytocin (1–10 μm) produced dose-related inhibition of EPSCs induced by stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone (n = 3–7; Fig. 9A). The inhibitory effects were reversible and returned to baseline after washout of oxytocin. To determine the involvement of postsynaptic oxytocin receptors, we added the irreversible G protein activator GTP-γ-S (0.5 mm) to the intracellular solution to inhibit the postsynaptic oxytocin receptor signalling pathway. We found that the inhibitory effect of oxytocin was completely abolished after postsynaptic inhibition of G proteins (n = 5, Fig. 9), indicating that postsynaptic oxytocin receptors are involved in synaptic inhibition by oxytocin.

Figure 9. Oxytocin inhibits glutamate mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents through postsynaptic receptors.

A and B, whole-cell recordings from dorsal horn neurones in a slice from a neonatal rat. EPSCs evoked by stimulation of the dorsal root entry zone were reversibly inhibited by oxytocin (10 μm; A). This effect was blocked by postsynaptic application of GTP-γ-S (0.5 mm), an irreversible activator of G proteins (B). C, time course of the experiments shown in A and B. D, summary histogram of the data (10 μm oxytocin). Error bars represent s.e.m.; *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

We used oxytocin-deficient mice to demonstrate that oxytocin is essential for stress-induced antinociception. Because spinal cord and DRG neurones in the mouse do not produce any oxytocin, these spinal inhibitory effects of oxytocin are probably due to the descending oxytocin-containing projection from hypothalamic PVN neurones. Normal spinal nociception is not significantly altered in mice lacking oxytocin, which suggests that descending oxytocin pathways do not tonically regulate spinal nociceptive transmission. Our results show that oxytocin inhibits glutamate-mediated sensory synaptic transmission between primary afferent fibres and dorsal horn neurones in both rats and mice, providing a cellular mechanism for the actions of oxytocin in the spinal cord.

The effects observed are most likely to be due to the deletion of the oxytocin gene, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the expression or function of other molecules may be affected by the knockout of the oxytocin gene. Whether the slight decrease in stress-induced c-Fos in the PVN of oxytocin-knockout mice reflects the loss of oxytocin-containing neurones or slight alterations in descending modulation is not known. However, the selective defect in stress-induced antinociception, but not in acute nociception or morphine-induced antinociception, indicates that the effect of the oxytocin deletion is relatively selective.

Spinal action of oxytocin

Because similar results were obtained with cold-swim stress and the temperature-independent restraint stress, our results argue against the possibility that alterations in the processing of peripheral temperature could contribute to the defect in oxytocin-knockout mice. In our studies, only the skin surface temperature at the hindpaw or tail was measured. Changes in deeper tissue could contribute to thermal antinociception, although, since similar findings were obtained with the mechanical withdrawal test, we believe that these potential skin temperature changes are not a major factor underlying the defect in the stress-induced antinociception.

Similarly, a role of circulating oxytocin or an alteration in stress hormones must be considered. A recent study in rats showed that intracerebral application of oxytocin receptor antagonists upregulated the adrenocorticotropic hormone levels (Neumann et al. 2000). However, the tail-flick is a spinally mediated nociceptive behavioural reflex, whereas the hot-plate test also activates supraspinal areas. The lack of stress-induced analgesia in both the hot-plate and the tail-flick test suggests that the spinal cord dorsal horn is a likely site of action for oxytocin. Our electrophysiological data demonstrate that oxytocin could indeed inhibit glutamate-mediated sensory transmission in the spinal cord. This mechanism provides a simple explanation of the behavioural phenotype.

It has been well documented that neurones in the PVN are activated during stress and release oxytocin (Cullinan et al. 1995). Immunostaining studies of different immediate early genes show that oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN are activated following restraint and other stressors (Ceccatelli et al. 1989; Hatakeyama et al. 1996). In the present study, we demonstrate similar results in adult mice. Cold-swim induces expression of c-Fos in PVN magno- and parvocellular neurones. Double staining with an antibody against oxytocin confirms that many of these c-Fos-positive cells contain oxytocin.

Previous studies have suggested that descending oxytocin neurones might contribute to antinociception (Lundeberg et al. 1994). PVN neurones containing oxytocin project to the spinal cord (Sawchenko & Swanson, 1982; Cechetto & Saper, 1988), where they synapse onto dorsal horn neurones (Rousselot et al. 1990), which express the oxytocin receptor (Reiter et al. 1994). As mentioned above, PVN neurones are activated by stress and oxytocin is reported to be released in the spinal cord following stress (Miaskowski et al. 1988). Thus, oxytocin-containing pathways from the PVN constitute a descending modulation system in addition to the well-defined input from the rostral ventral medulla (Gebhart & Randich, 1990; Fields et al. 1991). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that activation of projections to forebrain areas may also provoke antinociceptive effects.

We noted that oxytocin receptors were downregulated in mice lacking oxytocin. This differs from other transmitter systems, such as the enkephalin-opioid receptor in which upregulation of opioid receptors has been reported in mice lacking enkephalin (Brady et al. 1999). This raises the possibility that oxytocin may regulate postsynaptic expression of its own receptor in an activity-dependent manner. Future studies are needed to explore the molecular mechanisms for such downregulation of oxytocin receptors.

The loss of receptors in the knockout mice prevented us from attempting to rescue the phenotype of the knockout mice with intrathecal injections of oxytocin. The converse experiment, i.e. intrathecal injection of the oxytocin antagonist in wild-type mice, was performed. The results support the hypothesis that spinal release of oxytocin mediates stress-induced analgesia.

Central origin of spinal oxytocin in mice

Previous studies using different approaches have consistently suggested that the major source of spinal oxytocin-containing fibres is the parvocellular oxytocin-containing neurones in the PVN of the hypothalamus in rats (Lang et al. 1983; Pittman et al. 1984; White et al. 1986; Rousselot et al. 1990). It has been proposed that spinal oxytocin-containing fibres may also have a sensory afferent source, because oxytocin was detected in lumbar DRG in rats (Kai-Kai et al. 1985, 1986), although a recent study showed that central glomeruli in the dorsal horn, known to contain several neuropeptides and to be of primary sensory origin, were immunonegative for oxytocin (Rousselot et al. 1990). In our studies, we found no evidence for oxytocin mRNA in mouse lumbar DRG. One possible explanation is a difference between species. Indeed, no oxytocin immunoreactivity has been found in the DRG of cats (Garry et al. 1989). A disparity in the expression of oxytocin between the rat and mouse has been also reported in the uterus (Sugimoto et al. 1997; L. J. Muglia & S. K. Vogt, unpublished data). Furthermore, previous studies using immunohistochemical or high-performance liquid chromatography methods lacked the ultimate negative control, an animal deficient in oxytocin. Both Southern analysis and PCR have confirmed that our mouse line is devoid of all oxytocin coding regions (mature peptide as well as the pre-hormone) at the DNA level, so it is impossible for these mice to generate any oxytocin. These findings also indicate that the oxytocin antibody may bind to other proteins in DRG cells. This does not seem to be a concern in the central nervous system since no staining is seen in the hypothalamus and spinal cord of the knockout mice.

Mechanisms for oxytocin produced antinociception in the spinal cord

Although both glutamate and peptides can be released from primary afferents, recent studies using genetically manipulated mice as well as in vitro spinal slices have confirmed that glutamate is the major neurotransmitter for acute moderate nociceptive stimuli (Yoshimura & Jessell, 1990; Cao et al. 1998; De Felipe et al. 1998; Li et al. 1998, 1999; Woolf et al. 1998).

The present results show that oxytocin inhibits sensory glutamatergic transmission between afferent fibres and dorsal horn neurones. The intracellular mechanism of inhibitory action of oxytocin receptors is unknown and remains to be investigated. Oxytocin may activate G protein-related signal pathways and regulate the function of postsynaptic AMPA receptors, thus reducing synaptic responses. In rat vagal neurones, oxytocin directly gated a sustained sodium current, which depolarized the neurones and induced firing (Raggenbass & Dreifuss, 1992). However, in the present study, we found that bath application of oxytocin did not affect the resting membrane potential of dorsal horn neurones.

A presynaptic locus of action of oxytocin has previously been suggested, both in the SON (Kombian et al. 1997) and in spinal dorsal horn cultures (Jo et al. 1998). We cannot exclude presynaptic actions of oxytocin (e.g. decreases in presynaptic release of glutamate), although paired-pulse facilitation was not affected by oxytocin application. In cultured dorsal horn neurones, oxytocin significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs as well as the amplitude of evoked EPSCs (Jo et al. 1998). In contrast, our results in slices from the synapse between the primary afferent fibres and the dorsal horn neurones show an inhibitory and post-synaptic effect of oxytocin. These results are not contradictory. They may reflect differences in the experimental preparation employed (slice versus culture), and in the nature of presynaptic cells (primary afferent or local dorsal horn neurones). However, the net effect is similar. Because most cultured dorsal horn neurones are likely to contain inhibitory neurotransmitters, Jo et al. (1998) proposed that oxytocin indirectly inhibits sensory transmission between primary afferent fibres and dorsal horn neurones by exciting spinal inhibitory interneurones.

Oxytocin-mediated analgesia may have important sequelae for animal behaviour under different circumstances. For example, during the fight or flight response, stress-induced antinociception could reduce potential suffering from injury. Finally, while our results and those of others suggest that oxytocin antinociception is independent of morphine-induced antinociception (Millan et al. 1984; Lundeberg et al. 1994), the two systems may be synergistic (Arletti et al. 1993). This raises the possibility that a combination of oxytocin and opioids might be an efficient therapy, allowing doses of opioids to be reduced.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Jeff Lichtman for suggestions. This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (NIDA 10833, NINDS 38680; M.Z.), and McDonnell High Brain Function at Washington University (M.Z.), Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Development Award in the Biomedical Sciences (L.J.M.).

REFERENCES

- Arletti R, Benelli A, Bertolini A. Influence of oxytocin on nociception and morphine antinociception. Neuropeptides. 1993;24:125–129. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(93)90075-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong WE. Morphological and electrophysiological classification of hypothalamic supraoptic neurons. Progress in Neurobiology. 1995;47:291–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiazu I, Cruzblanca H, Li P, Linder M, Zhuo M, Gautam N. A G protein gamma subunit-specific peptide inhibits muscarinic receptor signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:35305–35308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady LS, Herkenham M, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Konig M, Zimmer AM, Zimmer A. Region-specific up-regulation of opioid receptor binding in enkephalin knockout mice. Molecular Brain Research. 1999;68:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussaard AB, Kits KS, Baker RE, Willems WP, Leyting-Vermeulen JW, Voorn P, Smit AB, Bicknell RJ, Herbison AE. Plasticity in fast synaptic inhibition of adult oxytocin neurons caused by switch in GABA(A) receptor subunit expression. Neuron. 1997;19:1103–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YQ, Mantyh PW, Carlson EJ, Gillespie AM, Epstein CJ, Basbaum AI. Primary afferent tachykinins are required to experience moderate to intense pain. Nature. 1998;392:390–394. doi: 10.1038/32897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccatelli S, Villar MJ, Goldstein M, Hokfelt T. Expression of c-Fos immunoreactivity in transmitter-characterized neurons after stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:9569–9573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cechetto DF, Saper CB. Neurochemical organization of the hypothalamic projection to the spinal cord in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;272:579–604. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Battaglia DF, Akil H, Watson SJ. Pattern and time course of immediate early gene expression in rat brain following acute stress. Neuroscience. 1995;64:477–505. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felipe C, Herrero JF, O'Brien JA, Palmer JA, Doyle CA, Smith AJ, Laird JM, Belmonte C, Cervero F, Hunt SP. Altered nociception, analgesia and aggression in mice lacking the receptor for substance P. Nature. 1998;392:394–397. doi: 10.1038/32904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Hearn EF, Matzuk MM, Insel TR, Winslow JT. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Heinricher MM, Mason P. Neurotransmitters in nociceptive modulatory circuits. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1991;14:219–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontan JJ, Cortright DN, Krause JE, Velloff CR, Karpitskyi VV, Carver TWJ, Shapiro SD, Mora BN. Substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor expression by intrinsic airway neurons in the rat. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2000;278:L344–355. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.2.L344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan WB, Grutzendler J, Wong WT, Wong RO, Lichtman JW. Multicolor ‘DiOlistic’ labeling of the nervous system using lipophilic dye combinations. Neuron. 2000;27:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry MG, Miller KE, Seybold VS. Lumbar dorsal root ganglia of the cat: a quantitative study of peptide immunoreactivity and cell size. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;284:36–47. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart GF, Randich AI. Brainstem modulation of nociception. In: Klemm WR, Vertes RP, editors. Brainstem Mechanisms of Behaviour. New York: Wiley and Sons; 1990. pp. 315–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gross GA, Imamura T, Luedke C, Vogt SK, Olson LM, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y, Muglia LJ. Opposing actions of prostaglandins and oxytocin determine the onset of murine labor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:11875–11879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S, Kawai Y, Ueyama T, Senba E. Nitric oxide synthase-containing magnocellular neurons of the rat hypothalamus synthesize oxytocin and vasopressin and express Fos following stress stimuli. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 1996;11:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(96)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI. Emerging concepts of structure-function dynamics in adult brain: the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. Progress in Neurobiology. 1990;34:437–504. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90017-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes RL, Bennett GJ, Newlon PG, Mayer DJ. Behavioural and physiological studies of non-narcotic analgesia in the rat elicited by certain environmental stimuli. Brain Research. 1978;155:69–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YH, Stoeckel ME, Freund-Mercier MJ, Schlichter R. Oxytocin modulates glutamatergic synaptic transmission between cultured neonatal spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:2377–2386. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02377.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai-Kai MA, Anderton BH, Keen P. A quantitative analysis of the interrelationships between subpopulations of rat sensory neurons containing arginine vasopressin or oxytocin and those containing substance P, fluoride-resistant acid phosphatase or neurofilament protein. Neuroscience. 1986;18:475–486. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai-Kai MA, Swann RW, Keen P. Localization of chromatographically characterized oxytocin and arginine-vasopressin to sensory neurones in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1985;55:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Li P, Zhuo M, Huettner JE. Presynaptic kainate receptors regulate spinal sensory transmission. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:59–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombian SB, Mouginot D, Pittman QJ. Dendritically released peptides act as retrograde modulators of afferent excitation in the supraoptic nucleus in vitro. Neuron. 1997;19:903–912. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupers RC, Vos BP, Gybels JM. Stimulation of the nucleus paraventricularis thalami suppresses scratching and biting behaviour of arthritic rats and exerts a powerful effect on tests for acute pain. Pain. 1988;32:115–125. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RE, Heil JW, Ganten D, Hermann K, Unger T, Rascher W. Oxytocin unlike vasopressin is a stress hormone in the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;37:314–316. doi: 10.1159/000123566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Calejesan AA, Zhuo M. ATP P2x receptors and sensory synaptic transmission between primary afferent fibers and spinal dorsal horn neurons in rats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80:3356–3360. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Wilding TJ, Kim SJ, Calejesan AA, Huettner JE, Zhuo M. Kainate-receptor-mediated sensory synaptic transmission in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1999;397:161–164. doi: 10.1038/16469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Zhuo M. Silent glutamatergic synapses and nociception in mammalian spinal cord. Nature. 1998;393:695–698. doi: 10.1038/31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Zhuo M. Cholinergic, noradrenergic, and serotonergic inhibition of fast synaptic transmission in spinal lumbar dorsal horn of rat. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;54:639–647. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeberg T, Uvnas-Moberg K, Agren G, Bruzelius G. Anti-nociceptive effects of oxytocin in rats and mice. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;170:153–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Ong GL, Lukic D, Haldar J. Immobilization stress affects oxytocin and vasopressin levels in hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic sites. Brain Research. 1988;458:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Schmauss C, Millan MH, Herz A. Vasopressin and oxytocin in the rat spinal cord: analysis of their role in the control of nociception. Brain Research. 1984;309:384–388. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Sternberg WF, Balian H, Liebeskind JC, Sadowski B. Opioid and nonopioid swim stress-induced analgesia: a parametric analysis in mice. Physiology of Behaviour. 1996;59:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muglia L, Jacobson L, Dikkes P, Majzoub JA. Corticotropin-releasing hormone deficiency reveals major fetal but not adult glucocorticoid need. Nature. 1995;373:427–432. doi: 10.1038/373427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Kromer SA, Toschi N, Ebner K. Brain oxytocin inhibits the (re)activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in male rats: involvement of hypothalamic and limbic brain regions. Regulatory Peptides. 2000;96:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimori K, Young LJ, Guo Q, Wang Z, Insel TR, Matzuk MM. Oxytocin is required for nursing but is not essential for parturition or reproductive behaviour. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:11699–11704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson CA, Caldwell JD, Jirikowski GF, Insel TW. Oxytocin in maternal, sexual, and social behaviours. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;652:1–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman QJ, Riphagen CL, Lederis K. Release of immunoassayable neurohypophyseal peptides from rat spinal cord, in vivo. Brain Research. 1984;300:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90842-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porro CA, Carli G. Immobilization and restraint effects on pain reactions in animals. Pain. 1988;32:289–307. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggenbass M, Dreifuss JJ. Mechanism of action of oxytocin in rat vagal neurones: induction of a sustained sodium-dependent current. Journal of Physiology. 1992;457:131–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter MK, Kremarik P, Freund-Mercier MJ, Stoeckel ME, Desaulles E, Feltz P. Localization of oxytocin binding sites in the thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord of the adult and postnatal rat: a histoautoradiographic study. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;6:98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselot P, Papadopoulos G, Merighi A, Poulain DA, Theodosis DT. Oxytocinergic innervation of the rat spinal cord. An electron microscopic study. Brain Research. 1990;529:178–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90825-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Leng G. Sex, parturition and motherhood without oxytocin? Journal of Endocrinology. 1998;157:343–359. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1570343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1982;205:260–272. doi: 10.1002/cne.902050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Segi E, Tsuboi K, Aze Y, Nishimura T, Oida H, Yoshida N, Tanaka T, Katsuyama M, Hasumoto K, Murata T, Hirata M, Ushikubi F, Negishi M, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S. Failure of parturition in mice lacking the prostaglandin F receptor. Science. 1997;277:681–683. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemura M, Kimura T, Nomura S, Makino Y, Inoue T, Kikuchi T, Kubota Y, Tokugawa Y, Nobunaga T, Kamiura S, Onoue H, Azuma C, Saji F, Kitamura Y, Tanizawa O. Expression and localization of human oxytocin receptor mRNA and its protein in chorion and decidua during parturition. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;93:2319–2323. doi: 10.1172/JCI117236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truesdell LS, Bodnar RJ. Reduction in cold-water swim analgesia following hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus lesions. Physiology of Behaviour. 1987;39:727–731. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvnas-Moberg K, Bruzelius G, Alster P, Bileviciute I, Lundeberg T. Oxytocin increases and a specific oxytocin antagonist decreases pain threshold in male rats. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1992;144:487–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JD, Krause JE, McKelvy JF. In vivo biosynthesis and transport of oxytocin, vasopressin and neurophysin from the hypothalamus to the spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1986;17:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ, Neumann S. Null mutations lacking substance: elucidating pain mechanisms by genetic pharmacology. Neuron. 1998;20:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XJ, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Is systemically administered oxytocin an analgesic in rats? Pain. 1994;57:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya R, Ben-eliyahu S, Shavit Y, Marek P, Liebeskind JC. Stimulation of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus produces analgesia not mediated by vasopressin or endogenous opioids. Brain Research. 1990;537:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90354-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Jessell T. Amino acid-mediated EPSPs at primary afferent synapses with substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:315–335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WS, Shepard E, Amico J, Hennighausen L, Wagner KU, LaMarca ME, McKinney C, Ginns EI. Deficiency in mouse oxytocin prevents milk ejection, but not fertility or parturition. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1996;8:847–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1996.05266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M. NMDA receptor-dependent long term hyperalgesia after tail amputation in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;349:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]