Abstract

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) provide pacemaker activity in some smooth muscles. The nature of the pacemaker conductance is unclear, but studies suggest that pacemaker activity is due to a voltage-independent, Ca2+-regulated, non-selective cation conductance. We investigated Ca2+-regulated conductances in murine intestinal ICC and found that reducing cytoplasmic Ca2+ activates whole-cell inward currents and single-channel currents. Both the whole-cell currents and single-channel currents reversed at 0 mV when the equilibrium potentials of all ions present were far from 0 mV. Recordings from on-cell patches revealed oscillations in unitary currents at the frequency of pacemaker currents in ICC. Voltage-clamping cells to −60 mV did not change the oscillatory activity of channels in on-cell patches. Depolarizing cells with high external K+ caused loss of resolvable single-channel currents, but the oscillatory single-channel currents were restored when the patches were stepped to negative potentials. Unitary currents were also resolved in excised patches. The single-channel conductance was 13 pS, and currents reversed at 0 mV. The channels responsible were strongly activated by 10−7m Ca2+, and 10−6 m Ca2+ reduced activity. The 13 pS channels were strongly activated by the calmodulin inhibitors calmidazolium and W-7 in on-cell and excised patches. Calmidazolium and W-7 also activated a persistent inward current under whole-cell conditions. Murine ICC express Ca2+-inhibited, non-selective cation channels that are periodically activated at the same frequency as pacemaker currents. This conductance may contribute to the pacemaker current and generation of electrical slow waves in GI muscles.

Considerable evidence suggests that interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are the pacemakers cells in gastrointestinal (GI) muscles (e.g. Langton et al. 1989; Ward et al. 1994; Huizinga et al. 1995; Thomsen et al. 1998; Koh et al. 1998; Dickens et al. 1999). Freshly isolated (Langton et al. 1998) and cultured ICC (Thomsen et al. 1998; Koh et al. 1998) generate spontaneous electrical slow waves and pacemaker currents. Absence of ICC in tissues results in loss of slow waves (Torihashi et al. 1995; and for see review Sanders, 1996). Voltage clamp studies have shown that holding cells at potentials between −80 and 0 mV does not significantly affect the frequency of spontaneous pacemaker currents, suggesting that activation of the pacemaker conductance is not voltage-dependent (Koh et al. 1998). The pacemaker currents reversed near 0 mV, were blocked by Gd3+, and were reduced by niflumic acid, decreased extracellular Na+, and decreased extracellular Ca2+. From whole-cell studies, investigators have suggested that the pacemaker current may be due to Ca2+-activated Cl− channels or a non-selective cation conductance (Tokutomi et al. 1995; Thomsen et al. 1998; Koh et al. 1998). Both types of conductance are modulated by changes in intracellular Ca2+, so it is likely that a Ca2+-dependent conductance is important for the pacemaking mechanism in ICC.

Other studies support the notion that the pacemaker current is due to a conductance regulated by Ca2+. Activation of pacemaker currents in ICC and slow waves in GI muscles is associated with Ca2+ release from IP3-receptor operated channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999; Suzuki et al. 2000; Ward et al. 2000; van Helden et al. 2000), and one study has suggested that mitochondrial uptake of Ca2+ subsequent to release is the step that activates pacemaker current (Ward et al. 2000). It is still unclear which phase of the Ca2+ transient is actually responsible for current activation. In the scheme involving Ca2+-activated Cl−, a local rise in Ca2+ near the plasma membrane might activate clusters of pacemaker channels. In the concept involving mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, transient reduction in Ca2+ near the plasma membrane may be the activating step (Ward et al. 2000). The participation of non-selective cation channels in either mechanism has not been determined.

In the present study we performed whole-cell and single-channel studies to determine the nature of inward currents regulated by Ca2+ in ICC and whether such a conductance might contribute to the pacemaker currents in ICC. We provide evidence for a Ca2+-inhibited, non-selective cation conductance that is abundantly expressed by murine small intestinal ICC. We related the whole-cell current to a unitary conductance that displayed oscillatory activation at the same frequency as whole-cell pacemaker currents. We have also investigated the Ca2+ dependence of the single-channel currents and their regulation by Ca2+/calmodulin binding.

METHODS

Preparation of cells

Balb/C mice (10–15 days old) of either sex were anaesthetized with carbon dioxide and killed by cervical dislocation. Small intestines, from 1 cm below the pyloric ring to the caecum, were removed and opened along the myenteric border. Luminal contents were washed away with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate solution (KRB). Tissues were pinned to the base of a Sylgard dish and the mucosa was removed by sharp dissection. The use and treatment of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Nevada.

Small strips of intestinal muscle were equilibrated in Ca2+ free Hanks' solution for 30 min and cells were dispersed, as previously described (Koh et al. 1998), with an enzyme solution containing: collagenase (Worthington type II), 1.3 mg ml−1; bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) 2 mg ml−1; and trypsin inhibitor (Sigma). Cells were plated onto sterile glass coverslips coated with murine collagen (2.5 μg ml−1, BD Falcon) in 35 mm culture dishes. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 95 % O2-5 % CO2 incubator in SMGM (Smooth Muscle Growth Medium; Clonetics Corp., San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 2 % antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) and murine stem cell factor (SCF, 5 ng ml−1, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). These studies were performed on single ICC and small networks of ICC (< 10 cells).

Patch clamp experiments

Single-channel and whole-cell patch clamp techniques were used to record membrane currents from cultured ICC. Currents were amplified with an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) or a List EPC-7 (List Electronics, Darmstadt, Germany) and digitized with a 12 bit A/D converter (Axon Instruments). Data were sampled at 5 kHz (for single-channel recordings) and 1 kHz (for whole-cell experiments). Data were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized on line using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes, made of borosilicate glass, had resistances of 1–3 MΩ for whole-cell experiments and 3–5 MΩ for single-channel recordings. Capacitance in whole-cell experiments averaged 21 ± 1 pF (n = 35).

For the whole-cell patch clamp experiments, the cells were bathed in a solution (CaPSS) containing (mm): 5 KCl, 135 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethyl piperazine-N′-ethanesulphonic acid (Hepes), adjusted to pH 7.4 with tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris). For external high K+ solutions, extracellular Na+ was replaced with equimolar K+. For Cl− replacement, sodium isethionate was used with an agar bridge to avoid liquid junction potential. Na+ replacement was accomplished with equimolar N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+). The pipette solution in whole-cell experiments contained (mm): 110 caesium aspartate, 20 CsCl, 5 MgCl2, 2.7 K2ATP, 0.1 Na2GTP, 2.5 creatine phosphate disodium, 5 Hepes, and 0.1 EGTA (or 10 BAPTA) adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris. For the single-channel recordings, the pipette solution was CaPSS. To test Ca2+ sensitivity of channels in the excised patches, the bath solution contained (mm): 110 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 1 EGTA and 10 Hepes adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris. Ca2+ was added to a bath solution buffered by 1 mm EGTA to create Ca2+ activities from 10−7 to 10−6m. Activities were calculated with a program developed by C.-M. Hai (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA). Calmidazolium, W-7 and niflumic acid (Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and desired concentrations were obtained by further dilution in extra- or intracellular solutions. The final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.05 %.

Results were analysed using pCLAMP8 (Axon Instruments), Origin software (version 5.0, OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) and GraphPad Prism (version 2.01, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) software. All experiments were performed at 29 °C.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Differences in the data were evaluated by Student's t test. P values less than 0.05 were taken as a statistically significant difference. The ‘n values’ reported in the text refer to the number of cells used in patch clamp experiments or the number of membrane patches used in studies of single-channel activity.

RESULTS

Inward current activated in ICC by buffering intracellular Ca2+

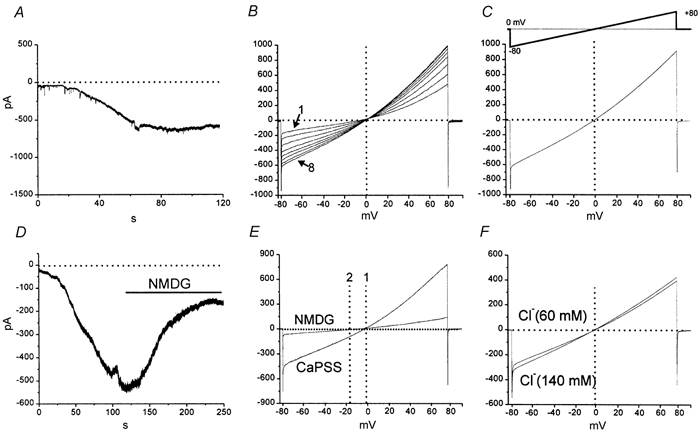

Previous studies have shown that Ca2+ release from IP3 receptors and uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria is associated with activation of inward (pacemaker) currents in ICC (Ward et al. 2000). To determine the effects of changing intracellular Ca2+ on membrane currents, we dialysed single ICC with 10 mm BAPTA (calculated free Ca2+ = 13 nm). During dialysis, cells were held at −10 mV and ramped every 5 s from −80 mV to +80 mV (n = 34). The current response to each successive ramp increased in magnitude (Fig. 1A and B). Persistent inward currents developed during BAPTA dialysis and reached an average current density of 33 ± 3 pA pF−1, and the current reversed at 0.7 ± 0.5 mV (Fig. 1C). When ICC were dialysed with 0.1 mm EGTA, the average holding current 2 min after breaking into the cell interior was 4.5 ± 0.7 pA pF−1 (P < 0.001). Thus high Ca2+ buffering elicited a significant inward current in ICC. There were concomitant changes in membrane potential with the two levels of Ca2+ buffering. With 0.1 mm EGTA and 10 mm BAPTA membrane potentials were −60 ± 2 mV (n = 12) and −18 ± 3 mV (n = 10), respectively. The current activated by 10 mm BAPTA was specific to ICC vs. smooth muscle cells. Dialysis of small intestine smooth muscle cells (n = 45) with 10 mm BAPTA did not activate an inward current (data not shown).

Figure 1. Activation of inward current in ICC by Ca2+ buffering.

A, persistent inward current activated by dialysis of an isolated ICC with BAPTA (10 mm) at a holding potential of −60 mV. B, responses to ramp potentials (inset in C) applied every 10 s during dialysis with BAPTA (10 mm) in another cell. Current that reversed at approximately 0 mV (denoted by dotted line) developed during the course of the dialysis (trace labelled 1 was the response after breaking in and trace labelled 8 was recorded after the steady state inward current developed). C, the BAPTA-dependent difference current obtained by subtracting the current response to the first ramp from the ramp at steady-state. The current reversed near 0 mV (denoted by dotted vertical line). D, the effect of replacing Na+ with NMDG+ after development of the current during BAPTA dialysis at −60 mV. NMDG was added as denoted by the black bar. This caused substantial decrease in the current as shown in the response to ramp potentials in E.; replacing Na+ caused a leftward shift in reversal potential (reversal in CaPSS shown by line 1 and reversal after Na+ replacement shown at line 2). F, ramp potential responses for the current after BAPTA dialysis in normal external Cl− (140 mm; ECl = −40 mV) and after replacement of a portion of the Cl− with isethionate− (60 mm Cl−; ECl = −18 mV; 20 min). Cl− replacement had no significant effect on the magnitude or the reversal potential of the current.

After full development of the BAPTA-dependent inward current in seven cells, replacement of external Na+ with NMDA reduced the inward current from 737 ± 116 pA to 158 ± 22 pA (at −60 mV; P < 0.001) and shifted the reversal potential from 0.4 ± 1.4 to −15 ± 2 mV (P < 0.001; Fig. 1D and E). In another series of experiments, external NaCl was partially replaced by sodium isethionate (Na+ 140 mm, Cl− 80 mm, isethionate− 60 mm). The change in ECl due to this solution change would be from −40 mV in control to −16 mV in the isethionate-substituted solution. The amplitude and reversal potential for the current activated by BAPTA dialysis were not significantly changed by sodium isethionate replacement of NaCl (n = 5; Fig. 1F).

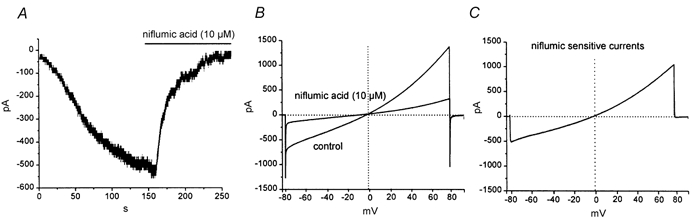

We have previously found that pacemaker currents in murine intestinal ICC can be partially blocked by DIDS (5 × 10−5m) (Koh et al. 1998) or niflumic acid (10−5m; S. D. Koh & K. M. Sanders, unpublished observations). Therefore, we tested niflumic acid on the inward current that developed after dialysis with BAPTA (10 mm). The equilibrium potential for Cl− ions was −40 mV in these experiments. Niflumic acid blocked a substantial portion of the inward current activated at a holding potential of −60 mV (Fig. 2A) but caused no shift in the reversal potential 1.6 ± 0.9 mV before and −0.7 ± 1.1 mV after niflumic acid (n = 7; P > 0.1). Figure 2 shows the effects of niflumic acid and difference currents showing the niflumic acid-sensitive current.

Figure 2. Effect of niflumic acid on the non-selective current activated by BAPTA dialysis.

After complete development of inward current during dialysis (current labelled control) niflumic acid was added to the bath (−60 mV holding potential) (A). Niflumic acid caused a significant decrease in the amplitude of the current and caused no significant shift in the reversal potential (B; reversal potential is shown by the vertical dotted line in B and C). C, the difference current representing the niflumic acid-sensitive current. This current reversed at a potential consistent with it being due to a non-selective cation current (e.g. ECl = −40 mV).

On-cell patch recordings from ICC

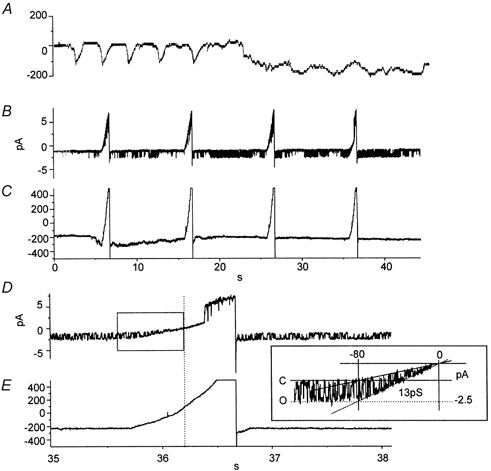

Next, we sought to determine the nature of the channels activated in ICC during spontaneous rhythmicity and whether these channels are similar to the conductance activated in ICC when cytoplasmic Ca2+ was reduced. In the first series of experiments, ICC were studied with the cell-attached patch clamp technique (bathing solution and pipette solution were CaPSS; patches were held at 0 mV). In greater than 75 % of 45 patches we observed single-channel currents, and there were periodic clusters of channel openings that generated inward currents averaging −13.4 ± 0.1 pA; n = 31 (Fig. 3). These summed membrane currents occurred at a frequency of 14 ± 0.4 events per min which was not significantly different from the frequency of spontaneous pacemaker currents recorded under whole-cell conditions (i.e. 14 ± 1 events per min; n = 17; P > 0.1).

Figure 3. Spontaneous inward currents recorded in an on-cell patch.

A, patch potential was held at 0 mV. Whole-cell potential was not controlled, so it must be assumed that cell membrane potential fluctuated between approximately −and −30 mV during spontaneous pacemaker events (see Koh et al. 1998). On-cell pipette recorded unitary currents between clusters of channel openings. B, a single inward current cluster (from record in A denoted by box) at a faster sweep speed.

The properties of the conductance(s) responsible for the current oscillations in cell-attached patches were difficult to ascertain under the conditions of these experiments. The whole-cell pacemaker currents of ICC cause membrane potential to depolarize from approximately −60 to −30 mV during each cycle (see Koh et al. 1998), and therefore the driving force on ions permeating channels in on-cell patches would be expected to change with time. Therefore, we performed additional experiments with two patch electrodes. One electrode was used in the whole-cell mode to maintain voltage control and to dialyse cells with 10 mm BAPTA (140 mm K+ and ECl = −30 mV). The second electrode was used in the on-cell patch configuration to monitor single-channel activity. After breaking into cells with the whole-cell pipette, a holding potential of −60 mV was applied, and a persistent inward current developed during BAPTA dialysis (Fig. 4A). Single-channel currents were recorded with a second electrode, and even in cells held at −60 mV regular oscillations in single-channel currents were observed, suggesting that the currents observed with a single electrode were not simply due to oscillations in driving force and periodic clusters of channel openings were not dependent upon voltage changes. As dialysis with 10 mm BAPTA proceeded, single-channel currents, recorded with the second electrode, were associated with the development of the whole-cell inward current (Fig. 4B). After the inward current elicited by BAPTA was fully developed, the cells were held at −80 mV and ramped from −80 mV to +80 mV (1 s ramps; see Fig. 4B and C). The unitary currents activated during BAPTA dialysis were inward at negative potentials and reversed at 0 mV (Fig. 4D and E). The conductance of the single channels (from linear regression analysis at potentials between −80 mV and 0 mV) was 13 pS (see Fig. 4D and E, inset).

Figure 4. Currents recorded during BAPTA dialysis with two electrodes.

A, the entire period of BAPTA dialysis during which spontaneous pacemaker activity gave way to the development of persistent inward current. B, unitary currents recorded from an on-cell patch on the same cell after completion of dialysis. The patch was held at 0 mV. C, whole-cell recording from the same cell during the same period as in B. The cell was held at −60 mV and periodically ramped from −80 to +80 mV. D and E, the period of a single ramp potential at a faster sweep speed. Note the effect of the ramp on the amplitude of the unitary currents (and see inset showing trace in region denoted by box in E). Extrapolation suggested that the unitary current reversed near 0 mV. Fitting of the amplitude of the unitary currents as a function of potential showed that the unitary currents were due to a 13 pS channel.

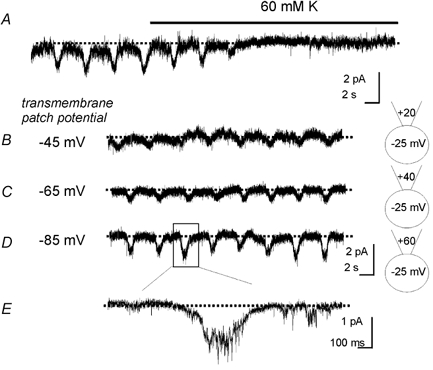

In an attempt to relate the conductance activated by intracellular Ca2+ buffering to the openings of channels in on-cell patches, we reduced cell membrane potential by elevating extracellular K+ concentration. In normal K+ (5 mm) small oscillations in patch membrane currents were noted in on-cell patches (patch holding potential 0 mV). Elevation of external K+ to 60 mm caused loss of the current oscillations (Fig. 5). Under these conditions, the estimated membrane potential of cells was approximately −25 mV, thus making the transmembrane potential of on-cell patches approximately −25 mV. Loss of resolvable currents under these conditions is consistent with the oscillating conductance in the on-cell patch having a reversal potential near 0 mV. While maintaining elevated external K+ (and therefore holding cell potential at approximately −25 mV) the patch potential was depolarized to more negative potentials (i.e. −20 to −60 mV). Thus, total potential across the membrane patch was varied from −45 mV to −85 mV. The rationale for this manoeuvre was to increase the driving force for the single-channel currents in the patch. Negative polarization of the patch restored the current oscillations (−1.8 ± 0.1 pA; and 14.0 ± 0.1 events per min at −85 mV; n = 4), and showed that single-channel conductance, described above, oscillates at the same frequency as the pacemaker mechanism (Koh et al. 1998; Ward et al. 2000). The monotonic increase in current amplitude as patch potential was moved away from 0 mV toward negative potentials and the fact that the oscillating conductance resulted in inward currents at −45 mV when Cl− equilibrium potential was approximately −40 mV suggests that the spontaneously oscillating currents in ICC were not due to a Cl− conductance. The frequency of the currents was 13.8 ± 0.9 at −45 mV events per min and 13.5 ± 0.6 events per min at −65 mV, demonstrating that oscillations in the conductance in on-cell patches were not regulated by patch voltage. This is consistent with the properties of the non-selective cation conductance responsible for pacemaker currents in ICC.

Figure 5. Effects of reducing cell membrane potential on unitary currents.

A, recording of inward currents using the on-cell patch technique. As denoted by the black bar, the solution bathing the cell was switched from 5 mm K+ to 60 mm K+ (changing EK to approximately −25 mV). The patch potential was held at 0 mV. Under these conditions it was not possible to resolve the spontaneous current oscillations. In B–D the membrane patch was stepped to more negative potentials (depicted in cartoons next to each trace) such that the combined transmembrane patch potential (cell potential-patch potential) was shifted from −45 mV to −85 mV. This produced a monotonic increase in the amplitude of the current oscillations. E, the current oscillation in D denoted by the box at a faster sweep speed.

Regulation of the pacemaker conductance by intracellular Ca2+

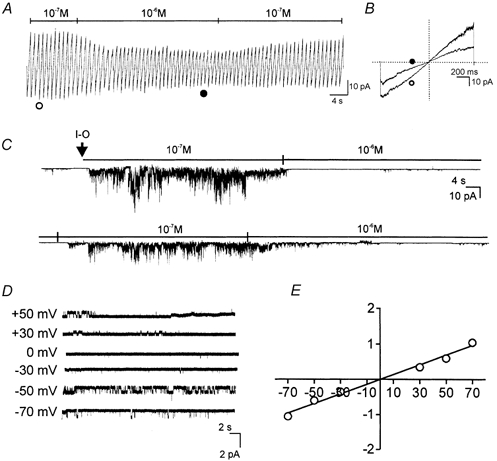

A whole-cell non-selective cation conductance and a single-channel conductance in on-cell patches that reversed at 0 mV were activated when cells were dialysed with 10 mm BAPTA. These observations suggest that reduced cytoplasmic Ca2+ may activate these channels. To test the properties of the channels more directly, patches were excised from spontaneously active cells, and the interior of the patch was exposed to bathing solutions containing 10−6 m Ca2+ (pipette solution contained CaPSS; EK and ECl were −87 and −30 mV, respectively, in these experiments). Under these conditions, we observed a single-channel conductance of 13 ± 1 pS (n = 4) that reversed at 0 mV. Representative traces and current-voltage curve are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6. Regulation of unitary currents by cytoplasmic Ca2+.

In excised patches, ramping patch potential from −80 to + 80 mV resulted in current that reversed at 0 mV (A and B). Switching the bath (cytoplasmic) Ca2+ from 10−7 to 10−6 m reduced channel openings in the patch. Current responses in B show ramps in 10−7 to 10−6 m Ca2+ denoted by ○ and • in A. Effects of changing Ca2+ are shown in a continuous record (−60 mV of holding potential) in C. At the arrow the patch was excised into bath solution containing 10−6 m Ca2+. At this Ca2+ concentration there were few channel openings. Channel openings were dramatically increased by changing the bath to 10−7m Ca2+. Switching back to 10−6 m Ca2+ inhibited channel openings. Activation of multiple channels at 10−7m made resolution of unitary currents difficult. D, the effect of voltage on unitary currents in a patch exposed to 10−6 m Ca2+. E, plotting the data from five cells shows the average current-voltage relationship (error bars contained within symbols). Fitting the averaged data points shows that the unitary currents were due to a conductance of 13.7 ± 0.7 pS.

The Ca2+ sensitivity of these channels was also examined. Ramp protocols (−80 to + 80 mV) were applied while switching the solution bathing the inside surface of the patch between 10−7 and 10−6 m Ca2+. Increasing intracellular Ca2+ (10−6m) dramatically decreased channel activity (Fig. 6A and B). When the cytosolic surface was exposed to 10−7 m Ca2+, openings of channels increased making it difficult to resolve unitary currents. The effects of cytosolic Ca2+ were rapidly reversed by switching back and forth between 10−7 and 10−6 m Ca2+ (−60 mV holding potential) (Fig. 6C).

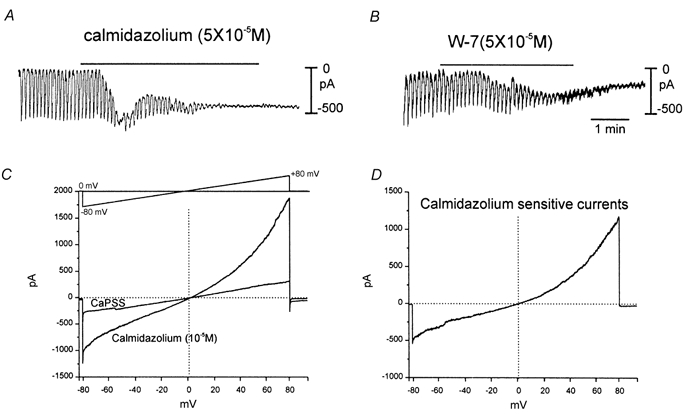

Regulation of non-selective conductance by Ca2+/calmodulin

The non-selective conductance negatively regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ was further investigated by testing the effects of calmodulin inhibitors. First, under whole-cell conditions we tested the effects of calmidazolium and W-7 (each at 50 μm) on small networks of ICC (Fig. 7A and B) and on isolated ICC (Fig. 7C and D). In each case, the calmodulin inhibitors activated persistent inward current and greatly reduced the amplitude (or blocked) the spontaneous pacemaker currents in ICC networks (−60 mV holding potential). The currents activated by calmidazolium and W-7 in isolated ICC reversed at 0.4 ± 2.0 mV, and this is not significantly different from the current activated by BAPTA dialysis (Fig. 7C and D).

Figure 7. Effects of calmodulin inhibitors on whole-cell currents in ICC.

A, recording from a small network of ICC. Regular, large-amplitude, pacemaker currents were recorded as previously described (Koh et al. 1998). Addition of calmidazolium (5 × 10−5 m) caused development of a persistent inward current and reduction of the spontaneous pacemaker currents (−60 mV holding potential). W-7 (5 × 10−5 m) had a similar effects in another network (B). C and D, application of calmidazolium to an isolated ICC. In C the cell was ramped from −80 to +80 mV (see inset in C) before and after calmidazolium (10−5 m). The drug initiated a large inward current. D, a difference current representing the calmidazolium-sensitive current. The current reversed near 0 mV. Vertical doted lines in C and D denote 0 mV.

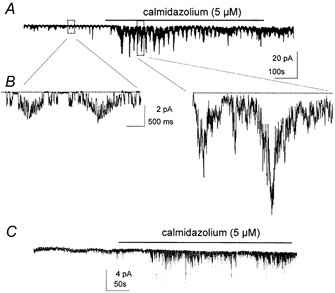

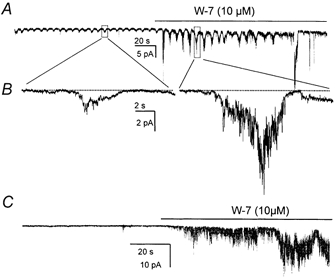

Additional experiments were performed on the currents in on-cell patches and excised patches. Application of calmidazolium (5 μm) while measuring single channels currents in on-cell patches greatly increased the magnitude of the current oscillations from −1.6 ± 0.1 pA to −12.9 ± 1.2 (P < 0.001; Fig. 8A and B; −60 mV holding potential). The calmodulin inhibitors apparently did not affect the mechanism driving these oscillations because there was no change in frequency (i.e. 14.5 ± 0.6 events per min in control and 13.8 ± 1.0 events per min after calmidazolium; P > 0.05). W-7 had the same effect: it raised the magnitude of the current oscillations to −10.7 ± 1.3 pA (P < 0.001) and had no effect on frequency (i.e. 14.0 ± 0.7 events per min in control and 13.8 ± 0.9 events per min after W-7; P > 0.05) (Fig. 9A and B). Similar observations were made with unitary currents in excised patches. In the presence of 10−6 m Ca2+ calmidazolium (Fig. 8C) and W-7 (Fig. 9C) activated 0.8 ± 0.1 pA unitary currents at −60 mV.

Figure 8. Effects of calmidazolium on single-channel currents.

A, clusters of channel openings at the frequency of pacemaker currents in an on-cell patch. Addition of calmidazolium (5 × 10−6 m) caused a significant increase in the openings of channels during clustered openings. The frequency of the clusters was not significantly altered by calmidazolium. B, portions of record in A denoted by boxes displayed at faster sweep speeds. Unitary currents can be observed before calmidazolium, but after application of the drug the increase in channel openings made it difficult to discern unitary currents. C, a recording from an excised patch with the cytoplasmic surface exposed to 10−6 m Ca2+. Addition of calmidazolium caused a dramatic increase in channel openings. Recordings were made at a holding potential of −60 mV.

Figure 9. Effects of W-7 on single-channel currents.

A, clusters of channel openings at the frequency of pacemaker currents in an on-cell patch. Addition of W-7 (10−5 m) caused a significant increase in the openings of channels during clustered openings. The frequency of the clusters was not significantly altered by W-7. B, portions of record in A denoted by boxes displayed at faster sweep speeds. C, a recording from an excised patch with the cytoplasmic surface exposed to 10−6 m Ca2+. Addition of W-7 dramatically increased channel openings. Recordings were made at a holding potential of −60 mV.

DISCUSSION

ICC generate spontaneous inward currents that are responsible for electrical slow waves in phasic GI muscles (see Sanders, 1996 for review). The pacemaker current responsible for slow waves in the intestine appears to be due to a non-selective cation conductance that is voltage-independent (i.e. the frequency of spontaneous pacemaker currents is not significantly affected by stepping voltage from −to 0 mV; Koh et al. 1998). In the present study, we identified 13 pS non-selective cation channels in on-cell patches of ICC that activate in clusters at the frequency of the slow wave cycle. Reducing intracellular Ca2+ also activated these channels. These channels were present in abundance in ICC; we estimate from cell capacitance measurements and channel density in patches that there were approximately 2 × 104 channels per cell. Single-channel currents due to channels with 13 pS conductance were also observed in excised patches. These currents reversed at approximately 0 mV under conditions in which the equilibrium potentials of all ions present were far from this potential. Openings of these channels were significantly increased when Ca2+ at the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane was reduced from 10−6 to 10−7 m. Whole-cell currents similar to the current activated by reduced intracellular Ca2+ were activated by calmodulin inhibitors calmidozolium and W-7. These compounds also activated single channels of the same conductance as those regulated by Ca2+ in on-cell and excised patches. The 13 pS channels we have identified are likely to contribute to the currents activated by BAPTA dialysis and calmodulin inhibitors, and they are likely to provide a major part of the conductance responsible for the spontaneous pacemaker currents in intestinal ICC.

The mechanism responsible for electrical rhythmicity in GI muscles has been described as ‘voltage-independent’since sucrose gap experiments performed on GI muscle strips showed that pacemaker frequency was weakly dependent upon membrane potential (i.e. 15 % change per 12 mV of depolarization; Ohba et al. 1975). Recent experiments on cultured ICC from the murine small intestine and stomach have also demonstrated that the frequency of pacemaker currents is not significantly affected by physiological membrane potentials (Koh et al. 1998; Kim et al. 2002). Thus a cellular event other than depolarization of the plasma membrane is involved in activating pacemaker currents.

With pharmacological tools and genetic models, several investigators have come to the conclusion that periodic release of Ca2+ from cell stores is the timing mechanism for pacemaker currents in ICC (Suzuki & Hirst, 1999; Suzuki et al. 2000; Ward et al. 2000; van Helden et al. 2000). At least one of these investigators has suggested that the local rise in Ca2+ due to Ca2+ release is responsible for initiating the pacemaker current (e.g. Nose et al. 2000). The present study, however, suggests that the falling phase of localized Ca2+ transients is most likely to be the primary activator of pacemaker currents. Periodic, localized reduction in Ca2+ may be accomplished in ICC by mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, and we have previously shown that mitochondrial Ca2+ rises shortly before the initiation of pacemaker currents in these cells (Ward et al. 2000). Furthermore, blocking mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by a variety of techniques, in GI muscles of several species, inhibits the generation of slow waves. Thus, pacemaker activity in GI muscles may result from Ca2+ release from IP3 receptor-operated stores, activation of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, localized reduction of Ca2+ concentration near the plasma membrane, and activation of pacemaker channels that are negatively regulated by Ca2+ (Sanders et al. 2000). Ultrastructural studies have demonstrated an abundance of SR and mitochondria in ICC (e.g. Faussone-Pellegrini et al. 1977; Thuneberg, 1982). SR and mitochondria lie in close proximity to each other, making it possible for Ca2+ release from IP3 receptors to stimulate mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. There is also close association between SR and mitochondria with the plasma membrane, making it possible that Ca2+ release and uptake via these organelles could affect the Ca2+ concentration in a microdomain just beneath the plasma membrane. These ultrastructural features of ICC are likely to be fundamental to the function of these cells as pacemakers.

It is difficult to unequivocally relate a single-channel conductance to a whole-cell current, and these difficulties are compounded when attempting to determine the role of specific channels in a pacemaker current. We found oscillation in the activity of channels in spontaneously rhythmic ICC, but currents from on-cell attached patches in single electrode experiments were difficult to interpret since the driving potential across the membrane patch would be affected by whole-cell membrane potential oscillations known to occur in these cells (Koh et al. 1998). Thus we used two methods to control cell voltage while recording membrane currents in patches. When cells were voltage-clamped with a second electrode to −60 mV we still noted oscillatory activation of channels in on-cell patches. Previous studies have shown that voltage-clamped cells continue to generate pacemaker currents (Koh et al. 1998; Thomsen et al. 1998; Ward et al. 2000), so continuation of oscillatory channel openings in patches on cells held at −60 mV is a property of the single channels that is shared with the pacemaker conductance. Dialysis of cells with BAPTA activated sustained, inward current in ICC and inhibited spontaneous pacemaker currents by apparently locking the underlying conductance on. BAPTA dialysis activated a whole-cell conductance and a 13 pS single-channel conductance, both of which reversed at 0 mV. The whole-cell conductance was not affected by shifting the Cl− equilibrium potential but was blocked when extracellular Na+ was replaced by NMDA. Finally, we depolarized cells with elevated external K+ to a point where single-channel currents could not be resolved. The estimated potentials of patches in these depolarized cells was close to the reversal potential of whole-cell pacemaker currents (Koh et al. 1998), so we expect that these conditions negated membrane potential oscillations. Depolarization of cells blocked the resolution of pacemaker currents but did not block the underlying mechanism that regulates pacemaker activity. Stepping the potential of membrane patches on depolarized cells to more negative potentials revealed clustered openings of channels like those observed in cells held at −60 mV. The amplitude of currents increased as patch potential was stepped negatively from 0 mV. Thus, we suggest that the 13 pS, non-selective, cation channels observed in ICC contribute to the spontaneous pacemaker currents generated by these cells. These channels are likely to be one of the key proteins responsible for electrical rhythmicity in GI muscles.

Our experiments do not exclude the possibility that other species of ion channels could contribute to pacemaker currents in ICC, but the reversal potentials of currents during the clusters of channel openings that occurred at the pacemaker frequency suggest that the major charge carriers in intestinal ICC are non-selective cation channels. Niflumic acid, which partially inhibits pacemaker currents in murine intestinal ICC (S. D. Koh & K. M. Sanders, unpublished observations), has been shown to have effects on non-selective cation conductances and, therefore, cannot be considered specific for Cl− channels (Gogelein et al. 1990; Accili & DiFrancesco, 1996; Zhang et al. 1998). In the present study we found that niflumic acid blocked a portion of the current activated when cells were dialysed with BAPTA, and the niflumic acid-sensitive current reversed at 0 mV, suggesting it was due to a non-selective cation conductance. We found no evidence for Ca2+-regulated, inward currents in excised patches other than the abundant 13 pS, non-selective, cation channels. Some of the Ca2+-activated Cl− channels that have been cloned have extremely low unitary conductances (Collier et al. 1996), and it is possible that tiny unitary currents were not resolved. However, if unresolved Cl− currents were a significant contributor to currents in ICC, one would expect reversal of current polarity to occur between 0 mV and the Cl− equilibrium potential and the reversal of whole-cell currents to be affected by shifts in the Cl− gradient. From our study, it does not appear that Ca2+-activated, inward currents, particularly due to Cl− conductances, are significant contributors to the pacemaker currents in intestinal ICC.

A conductance like the 13 pS channels found in ICC has not been observed in several previous studies of murine GI smooth muscle cells (e.g. Koh et al. 2001; Koh & Sanders, 2001), and we failed to activate inward current in smooth muscle cells with BAPTA dialysis in the present study. The lack of this conductance suggests that smooth muscle cells are not capable of slow wave activity, and this is consistent with experimental observations suggesting that active generation and regeneration of electrical slow waves is an exclusive property of ICC. Slow waves are thought to conduct passively from ICC into the smooth muscle syncytium (Horowitz et al. 1999). The unique expression of the 13 pS channels in ICC is another important indication of the special role for ICC in GI muscles.

The molecular identity of the 13 pS channels is unknown. Of known non-selective cation conductances, only transient receptor potential (Trp) channels have been shown to be inhibited by Ca2+/calmodulin binding (i.e. negatively regulated by Ca2+). Trp3 and Trp4 channels are inhibited by elevating Ca2+ at the cytoplasmic surface and are strongly activated by calmidazolium (Tang et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2001). We have previously reported that several species of Trp channels, including Trp4, are expressed by ICC (Epperson et al. 2000). These studies did not resolve expression of Trp3 channels in ICC. The channels expressed by ICC and characterized in the present study share the Ca2+/calmodulin regulatory properties of Trp3 and Trp4. Further experiments, including gene knock-out or anti-sense studies, will be required to unequivocally demonstrate the role of Trp channels in visceral pacemaker currents. The fact that Trp4 is expressed in ICC, and that these channels share important similarities with native pacemaker channels in terms of regulation by Ca2+ and calmodulin, make Trp4, or an unknown conductance with similar properties, leading candidates for the pacemaker conductance in GI muscles.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a program project grant from NIDDK (DK41315). Cultured ICC were produced by a core laboratory facility funded by the same grant.

REFERENCES

- Accili EA, Difrancesco D. Inhibition of the hyperpolarization-activated current (If) of rabbit SA node myocytes by niflumic acid. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431:757–762. doi: 10.1007/BF02253840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier ML, Levesque PC, Kenyon JL, Hume JR. Unitary Cl− channels activated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ in canine ventricular myocytes. Circulation Research. 1996;78:936–944. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens EJ, Hirst GD, Tomita T. Identification of rhythmically active cells in guinea-pig stomach. Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:515–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.515ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson A, Hatton WJ, Callaghan B, Doherty P, Walker RL, Sanders KM, Ward SM, Horowitz B. Molecular markers expressed in cultured and freshly isolated interstitial cells of Cajal. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;279:C529–539. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Cortesini C, Romagnoli P. Sull'ultrastruttura della tunica muscolare della prozione cardiale dell'esofago e dello stomaco umano con particolare riferimento alle cosiddette cellule inerstiziali di Cajal. Archivio Italiano di Anatomia e di Embriologia. 1977;82:157–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogelein H, Dahlem D, Englert HC, Lang HJ. Flufenamic acid, mefenamic acid, and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Letters. 1990;268:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80977-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz BM, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Cellular and molecular basis for electrical rhythmicity in gastrointestinal muscles. Annual Review of Physiology. 1999;61:19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Klüppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Beckett EAH, Hanna R, Koh SD, Ördög T, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Regulation of pacemaker frequency in the murine gastric antrum. Journal of Physiology. 2002;538:145–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Sanders KM. Stretch-dependent potassium channels in murine colonic smooth muscle cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;533:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0155b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Monaghan K, Ro S, Mason HS, Kenyon JL, Sanders KM. Novel voltage-dependent non-selective cation conductance in murine colonic myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2001;533:341–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0341a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Spontaneous electrical rhythmicity in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal from the murine small intestine. Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.203by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton P, Ward SM, Carl A, Norell MA, Sanders KM. Spontaneous electrical activity of interstitial cells of Cajal isolated from canine proximal colon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:7280–7284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba M, Sakamoto Y, Tomita T. The slow wave in the circular muscle of the guinea-pig stomach. Journal of Physiology. 1975;253:505–516. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose K, Suzuki H, Kannan H. Voltage dependency of the frequency of slow waves in antrum smooth muscle of the guinea-pig stomach. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 2000;50:625–633. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.50.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM. A case for interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:492–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM, Ördög T, Koh SD, Ward SM. A novel pacemaker mechanism drives gastrointestinal rhythmicity. News in Physiological Sciences. 2000;15:291–298. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Hirst GD. Regenerative potentials evoked in circular smooth muscle of the antral region of guinea-pig stomach. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0563t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Takano H, Yamamoto Y, Komuro T, Saito M, Kato K, Mikoshiba K. Properties of gastric smooth muscles obtained from mice which lack inositol trisphosphate receptor. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Lin Y, Zhang Z, Tikunova S, Birnbaumer L, Zhu MX. Identification of common binding sites for calmodulin and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors on the carboxyl termini of trp channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:21303–21310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102316200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L, Robinson TL, Lee JC, Farraway LA, Hughes MJ, Andrews DW, Huizinga JD. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate a rhythmic pacemaker current. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuneberg L. Interstitial cells of Cajal: intestinal pacemaker cells. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology and Cell Biology. 1982;71:1–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokutomi N, Maeda H, Tokutomi Y, Sato D, Sugita M, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa S, Nakao J, Imamura T, Nishi K. Rhythmic Cl− current and physiological roles of the intestinal c-kit-positive cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;431:169–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00410188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torihashi S, Ward SM, Nishikawa S-I, Nishi K, Kobayashi S, Sanders KM. c-kit-dependent development of interstitial cells and electrical activity in the murine gastrointestinal tract. Cell and Tissue Research. 1995;280:97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00304515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden DF, Imtiaz MS, Nurgaliyeva K, von der Weid P, Dosen PJ. Role of calcium stores and membrane voltage in the generation of slow wave action potentials in guinea-pig gastric pylorus. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:245–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:91–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Ördög T, Koh SD, Abu Baker S, Jun JY, Amberg G, Monaghan K, Sanders KM. Pacemaking in interstitial cells of Cajal depends upon calcium handling by endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McBride DW, Hamill OP. The ion selectivity of a membrane conductance inactivated by extracellular Ca2+ in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:763–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.763bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Tang J, Tikunova S, Johnson JD, Chen Z, Qin N, Dietrich A, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L, Zhu MX. Activation of Trp3 by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors through displacement of inhibitory calmodulin from a common binding domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:3168–3173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]