Abstract

We have investigated the pharmacological properties and targets of p2y purinoceptors in Xenopus embryo spinal neurons. ATP reversibly inhibited the voltage-gated K+ currents by 10 ± 3 %. UTP and the analogues α,β-methylene-ATP and 2-methylthio-ATP also inhibited K+ currents. This agonist profile is similar to that reported for a p2y receptor cloned from Xenopus embryos. Voltage-gated K+ currents could be inhibited by ADP (9 ± 0.8 %) suggesting that a further p2y1-like receptor is also present in the embryo spinal cord. Unexpectedly we found that α,β-methylene-ADP, often used to block the ecto-5′-nucleotidase, also inhibited voltage-gated K+ currents (7 ± 2.3 %). This inhibition was occluded by ADP, suggesting that α,β-methylene-ADP is an agonist at p2y1 receptors. We have directly studied the properties of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase in Xenopus embryo spinal cord. Although ADP inhibited this enzyme, α,β-methylene-ADP had no action. Caution therefore needs to be used when interpreting the actions of α,β-methylene-ADP as it has previously unreported agonist activity at P2 receptors. Xenopus spinal neurons possess fast and slow voltage-gated K+ currents. By using catechol to selectively block the fast current, we completely occluded the actions of ATP and ADP. Furthermore, the purines appeared to block only the fast relaxation component of the tail currents. We therefore conclude that the p2y receptors target only the fast component of the delayed rectifier. As ATP breakdown to ADP is rapid and ADP may accumulate at higher levels than ATP, the contribution of ADP acting through p2y1-like receptors may be an important additional mechanism for the control of spinal motor pattern generation.

ATP and adenosine are now widely accepted as important and universal signalling agents in the nervous system (see e.g. Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Robertson et al. 2001). ATP can act at ligand-gated channels (the P2X family, Valera et al. 1994) and at receptors coupled to G proteins (the P2Y family, Webb et al. 1993). Several variants of the P2Y receptor have been described and each has somewhat different agonist profiles and tissue distribution (von Kugelgen & Wetter, 2000). These include the P2Y1 receptors, which are more sensitive to di-phosphate agonists such as ADP than to ATP.

Following its release, ATP can be broken down in the extracellular space by a series of enzymes collectively called the ectonucleotidases (Zimmermann, 1996). The first step, mediated by ectoATPases, is rather rapid. Where the kinetics of these enzymes have been measured, the first step in the breakdown appears to have the highest rate (Gordon et al. 1986; James & Richardson, 1993). During neural activity ADP may thus accumulate to higher levels that ATP itself. This, and the presence of receptors that specifically respond to ADP, suggests that the diphosphate nucleotide may have important physiological modulatory roles in the nervous system.

In the spinal cord of the Xenopus embryo, ATP and adenosine control the temporal evolution of motor activity (Dale & Gilday, 1996; Dale, 1998; Brown & Dale, 2000). ATP is released and acts on p2y receptors to inhibit voltage-gated K+ currents and thus increases the excitability of the pattern-generating circuitry. However, the ATP is also broken down sequentially to adenosine which acts to inhibit voltage-gated Ca2+ currents and reduce the excitability of the spinal network. The changing balance between the excitatory and inhibitory actions of ATP and adenosine leads to a gradual run-down of motor activity and its eventual termination even in the absence of a terminating sensory signal. So far the identity of the p2y receptor involved and the nature of the voltage-gated current modulated has not been resolved. A p2y receptor has been cloned from Xenopus embryos and may play a developmental role (Bogdanov et al. 1997). Whether this receptor also mediates the physiological actions of ATP has not been established. Similarly we have not determined whether ADP may also help to inhibit the K+ currents.

Xenopus embryo spinal neurons possess several types of K+ current including two components of the delayed rectifier (fast and slow, Dale, 1995a; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998), a Na+-dependent K+ current (Dale, 1993) and a slowly activating Ca2+-dependent K+ current (Wall & Dale, 1995). The fast and slow components of the delayed rectifier have distinct roles, the former being involved in spike repolarization and threshold and the latter in the control of repetitive firing (Dale, 1995b; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). Although ATP modulates the voltage-gated K+ currents, it has not been established which components of the delayed rectifier are inhibited. Clearly, given their different roles, modulation of the separate components could have distinct functional consequences. Identification of the particular K+ current that is modulated by the p2y receptors is thus important to the quantitative and mechanistic understanding of how the purines regulate the generation of spinal motor patterns.

METHODS

Whole cell recording

In accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) stage 37/38 Xenopus embryos (Nieuwkoop & Faber, 1956) were anaesthetized in MS222 (1 mg ml−1, Sigma, Poole, UK). Their spinal cords were dissected free and, using previously described methods (Dale, 1991, 1995a; Sun & Dale, 1998), dissociated to provide acutely isolated neurons. Using a P97 puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA), electrodes were made from thick-walled borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA). An Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA), together with a DT31EZ or DT3010 interface (Data Translation, Marlboro, MA, USA) were used to record and digitize current and voltage records, which were acquired to the hard drive of a PC. Whole cell recordings had access resistance ranging from 5 to 20 MΩ. Between 75 and 85 % of this was compensated for electronically.

For recording K+ currents the pipette solution consisted of 100 mm KOH, 1 mm CaCl2, 100 mm MeSO3H, 2 mm BAPTA, 6 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATPNa2, 20 mm Hepes and 1 mm GTP, adjusted to pH 7.4 and 240 mosmol l−1. The external solution consisted of 115 mm NaCl, 2.4 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm Hepes, 5 mm glucose, 3 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm CaCl2 and 0.14 μm TTX, adjusted to pH 7.4 and 260 mosmol l−1. Drugs were applied through a multi-barrelled microperfusion pipette, which was positioned within 1 mm of the cell. All experiments took place at room temperature, 18–23 °C.

Measurement of K+ current modulation

To compensate for run-down of K+ currents, agonist effects for each cell were assessed by comparing the mean amplitude of the current during drug application to an equally weighted average of three to five measurements of current amplitude obtained immediately before agonist application and the same number of measurements taken after washout. The agonists were applied to several cells and the mean percentage inhibition of currents, in those cells that responded to the agonist, are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

The actions of purine nucleotide agonists on the voltage-gated K+ currents of spinal neurons

| Agonist | Proportion of cells responding | Mean inhibition (± s.e.m.) |

|---|---|---|

| ATP | 27/69 (39 %) | 10.3 ± 1.4% |

| UTP | 5/12 (42 %) | 5.3 ± 0.9% |

| α,β-Methylene-ATP | 3/15 (20 %) | 4.4 ± 0.9% |

| 2-Methylthio-ATP | 4/13 (31 %) | 5.4 ± 1.4% |

| ADP | 54/83 (65%) | 8.6 ± 0.8% |

| α,β-Methylene-ADP | 3/13 (23 %) | 7.0 ± 2.3% |

Both the proportion of cells showing modulation and mean inhibition in the neurons exhibiting inhibition are given.

HPLC analysis of spinal cord ecto-5′-nucleotidase

Ten spinal cords carefully isolated from stage 37/38 embryos were place in a small chamber (volume 2 μl) with a fine mesh bottom. The chamber had several inlets allowing different solutions to be introduced. To study the conversion of AMP to adenosine a 10 μm solution of etheno-AMP (ε-AMP) was run into the chamber and left for a period of 0, 30, 60, 120, 180 or 300 s. The chamber was then flushed with 100 μl of control saline and the perfusate collected on ice and stored frozen.

HPLC analysis was performed with a LUNA C8 (2) reverse phase column and a Thermo Separation Products HPLC gradient pump and fluorescence detector. The mobile phase consisted of the following solutions: 20 mm potassium phosphate pH 6.0 (A) and 75 % 20 mm potassium phosphate pH 6.0 and 25 % methanol (B; made according to the methods of Schweinsberg & Loo, 1980). A concave gradient was run going from 100 % A to 100 % B in 10 min. AMP typically eluted around 5 min and adenosine around 9 min. The column was re-equilibrated with solution A for 10 min between runs.

RESULTS

Triphosphate agonists

As previously reported, ATP caused rapid and reversible inhibition of the K+ currents in neurons acutely isolated from Xenopus spinal cord (Dale & Gilday, 1996; Fig. 1A, Table 1). ATP had these actions over a range of concentrations from 100 nm to 100 μm. The inhibition was on average rather small (∼10 %, Table 1), although in some instances considerably larger inhibition was observed (up to 23 %). The extent of observed inhibition appeared to depend upon the quality of the dissociated neurons suggesting that the receptors involved maybe somewhat labile during our dissociation procedures.

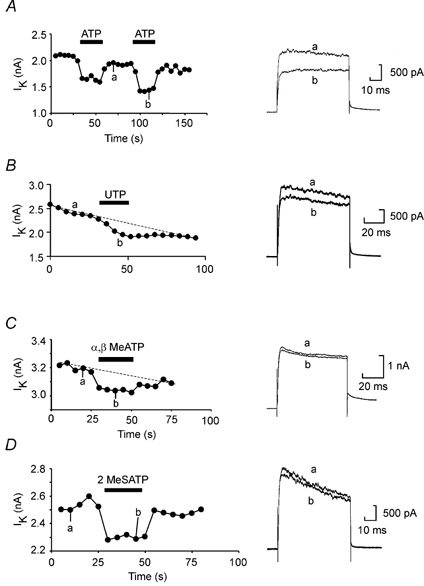

Figure 1. Voltage-gated K+ currents are modulated by the triphosphate nucleotides ATP, UTP and artificial analogues of ATP.

A, repeated voltage steps from −50 to 20 mV applied every 5 s evoked stable outward currents carried by the delayed rectifier in these neurons. ATP (100 μm) reversibly inhibited the current. B, in a different neuron UTP at 100 μm also inhibited the K+ currents. C and D, the non-hydrolysable ATP analogues α,β-methylene-ATP and 2-methylthio-ATP (at 100 μm) inhibited the K+ currents reversibly too.

We observed little dose dependence in the action of ATP: the modulation appeared to be all or none. This apparent lack of dose dependence may be because the total modulation was small and partial block could not be readily discriminated. As a concentration of 100 nm appeared to be saturating, the EC50 for the receptor is presumably lower than this value. This is similar to the concentration dependence of a p2y receptor cloned from Xenopus (xlp2y), which is also very steep and has an EC50 of around 80 nm (Bogdanov et al. 1997).

We investigated whether other triphosphate agonists could mimic the actions of ATP. We found that UTP, α,β-methylene-ATP and 2-methylthio-ATP caused very small but clearly reversible reductions of the K+ currents (Fig. 1B–D, Table 1). With the proviso that the receptor density of the acutely isolated neurons may be diminished, this range of effective agonists is qualitatively similar to that reported for the xlp2y receptor suggesting that this receptor could at least partially underlie the physiological actions of ATP in this preparation.

Diphosphate agonists

We next investigated whether diphosphate agonists could modulate K+ currents too. ADP reliably inhibited K+ currents in a higher proportion of neurons tested than did ATP (Table 1, Fig. 2). The maximum inhibition of K+ currents observed with ADP was 30 %. Surprisingly α,β-methylene-ADP, typically used as a blocker of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase, also inhibited K+ currents (Fig. 2, Table 1). These agents were as effective as ATP in their actions on the K+ currents. As ADP is only a weak agonist at the xlp2y receptor, we concluded that an additional receptor sensitive to ADP must be present. Given that 2-methylthio-ATP was an effective agonist (see above) our results suggest the existence of a p2y1-like receptor.

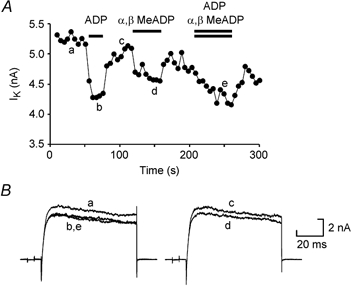

Figure 2. Voltage-gated K+ currents are modulated by the diphosphate nucleotides ADP and α,β-methylene-ADP acting at the same receptor.

A, graph showing the amplitude of the K+ currents evoked by repeated voltage steps from −50 to 20 mV applied every 5 s. ADP (100 μm) and α,β-methylene-ADP (100 μm) were applied separately and reversibly inhibited the currents. When the two agonists were applied simultaneously, the amount of block was no greater than that evoked by ADP alone. B, representative traces from the same experiment.

α,β-Methylene-ADP has not previously been reported as an agonist at p2y receptors. To test whether this ADP analogue might be active at p2y1 receptors we tested whether the actions of 100 μm ADP and 100 μm α,β-methylene-ADP were additive or occlusive. In six neurons, we applied ADP and α,β-methylene-ADP separately and in combination (Fig. 2). Separately, ADP and α,β-methylene-ADP caused mean inhibition of K+ currents by 10.7 ± 2.1 % and 7.4 ± 1.3 %, respectively. When applied together, the mean inhibition was 9.0 ± 1.5 %. The actions of ADP and α,β-methylene-ADP are thus not additive and we conclude that these agents act at the same p2y1-like receptor in Xenopus.

The actions of ADP on K+ currents could be blocked by the P2 antagonist PPADS. In five neurons ADP caused a mean inhibition of the K+ currents of 8.7 ± 1.3 %. Application of PPADS reduced this to 2.6 ± 1.0 %. Analysis of the cells responding to tri- and di-phosphate agonists gave further support for the existence of two p2y receptors. Out of 20 neurons where both ATP and ADP were tested, 13 neurons responded to both agents, 4 neurons only responded to ADP and 2 only to ATP (Fig. 3). Our results are most easily explained by proposing that the neurons express p2y1-like receptors in addition to the xlp2y receptor.

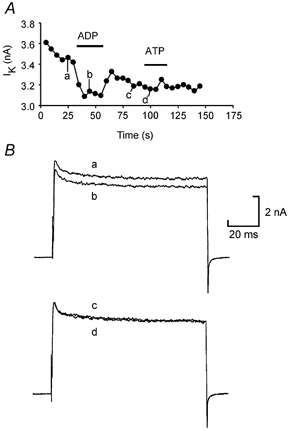

Figure 3. Some neurons are sensitive to ADP but not ATP suggesting that different receptors mediate the two responses.

A, graph showing the amplitude of the K+ currents evoked by repeated voltage steps from −50 to 20 mV applied every 5 s. ADP at 200 μm inhibited the currents, but ATP at 200 μm did not. B, representative current traces from the same experiment.

Like the action of ATP, the effects of ADP had a step-like dose sensitivity. Full modulation of the currents was observed at concentrations higher than 100 nm, but no modulation was observed below this dose. As for ATP this suggests an EC50 of less than 100 nm and we assume that the apparent lack of concentration sensitivity is due to the small magnitude of the observed modulation.

Identity of the voltage-gated K+ current

The fast and slow components of the delayed rectifier in Xenopus neurons have been characterized kinetically and pharmacologically (Dale, 1995a; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). We used catechol at a dose of 500 μm to block selectively the fast K+ current. This completely occluded the actions of ATP (Fig. 4A) suggesting that the fast K+ current but not the slow current was modulated.

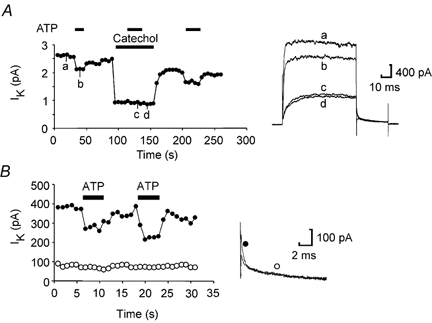

Figure 4. Modulation of the voltage-gated K+ currents is confined to the fast activating component and is occluded by catechol.

A, graph showing the amplitude of the K+ currents evoked by repeated voltage steps from −50 to 20 mV applied every 5 s. ATP (100 μm) inhibits the current (trace b). Catechol at 500 μm selectively blocks the fast activating component of the delayed rectifier. ATP applied during the catechol block has no effect on the remaining K+ currents (trace c, ATP washout trace d). Note that catechol (traces c and d) blocks only the fast component of the tail current. B, analysis of the tail currents shows that ATP only modulates the fast relaxation component (measured at 1 ms, •), but not the slow relaxation component (measured at 10 ms, ○). Representative tail current records illustrating modulation of the fast component by ATP are shown on the right.

To provide further evidence as to the nature of the K+ current inhibited by ATP, we examined the tail currents. These have two kinetic components at a potential of −30 mV: a fast decaying component with a time constant of around 1 ms, and a slow component with a time constant of around 15 ms. We found that ATP selectively blocked that fast component of the tail current but had no effect on the slow component (Fig. 4B). This confirms that ATP inhibits the fast but not the slow K+ current.

α,β-Methylene-ADP does not inhibit ecto-5′-nucleotidase in Xenopus

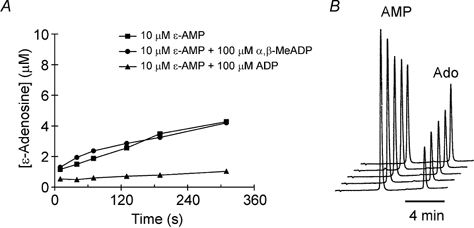

Our observation that α,β-methylene-ADP is a p2y1-like receptor agonist was unanticipated given that this agent is classically used as a blocker of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase. We therefore examined whether the native ecto-5′-nucleotidase in Xenopus embryo spinal cord was also sensitive to this agent. We used the conversion of etheno-labelled AMP (ε-AMP) to etheno-labelled adenosine as a convenient assay of ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity. This has the advantage that non-labelled ADP or α,β-methylene-ADP can be used as potential inhibitors of the enzyme reaction without interfering with the detection of the fluorescent product. ADP at 100 μm completely inhibited the conversion of ε-AMP to ε-adenosine (Fig. 5). By using a range of concentrations we estimated the IC50 for ADP on this enzyme as being around 6–10 μm. Despite this α,β-methylene-ADP at 100 μm had no effect on the conversion of ε-AMP to ε-adenosine (Fig. 5). We therefore conclude that α,β-methylene-ADP cannot block the ecto-5′-nucleotidase in Xenopus spinal cord.

Figure 5. Direct measurement of ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity in the spinal cord.

HPLC techniques were used to monitor the conversion of etheno-AMP (ε-AMP) to ε-adenosine. A, the enzyme was inhibited by ADP but not α,β-methylene-ADP, the classical antagonist of this enzyme. B, HPLC chromatograms showing the elution of ε-AMP and ε-adenosine (Ado). These chromatograms were obtained in the presence of α,β-methylene-ADP and represent the conversion of ε-AMP to ε-adenosine after 40, 70, 130, 190 and 310 s. The vertical axis is in units of absorbance. The ε-AMP clearly falls in size as the ε-adenosine peak rises.

DISCUSSION

Receptors present in Xenopus

Several variants of the G protein-linked P2Y receptor have now been described (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). One type of p2y receptor has already been cloned from Xenopus (Bogdanov et al. 1997). Transcripts for this receptor are abundant at early stages of development (stages 10–20) and then decrease in abundance although they are still found as late as stage 40 (Bogdanov et al. 1997). The receptor itself may of course persist considerably longer than this during development. The agonist profile that we find (at stage 37/38) for the inhibition of K+ currents is consistent with this receptor being present and functional in spinal neurons at this stage: ATP and UTP are effective agonists. However, we also found that ADP, α,β-methylene-ADP and 2-methylthio-ATP could inhibit K+ currents. These agents are at best only weak agonists at the xlp2y receptor. As ADP and 2-methylthio-ATP have been reported to be agonists at p2y1 receptors we suggest that these receptors or a close homologue are also present on Xenopus spinal cord neurons. In a small number of cases we found neurons that appeared to possess only one p2y receptor subtype - that is, they responded only to ADP or ATP, but not to both.

There are several reports of interactions between p2y receptors and ion channels in neurons (Ikeuchi & Nishizaki, 1995, 1996; Ikeuchi et al. 1996). In these examples the p2 receptor activated an outward K+ current in the neurons. Interestingly, the responses that were mediated by presumed p2y1-like receptors were membrane delimited, whereas a diffusible messenger mediated the actions of ATP (presumably through a p2y2-like receptor). Cloned P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors expressed in superior cervical sympathetic neurons can inhibit the native M currents of these neurons through a voltage-independent and pertussis toxin-insensitive mechanism (Brown et al. 2000). Our results in Xenopus have some similarity to those of the sympathetic neurons in that ATP and ADP (which are inhibitory rather than activating) act through separate receptors to target the same ionic current.

Role of ADP in motor pattern generation

We have previously demonstrated the importance of ATP, acting via p2y receptors, and its breakdown product adenosine, acting via A1 receptors in modulating the activity of the Xenopus central pattern generator (Dale & Gilday, 1996; Dale 1998; Brown & Dale, 2000). The kinetics of this breakdown, involving feed-forward inhibition by ATP and ADP of AMP conversion to adenosine, are vital to this scheme (Dale, 1998). Importantly, we have also demonstrated that the intermediate product AMP has no effect on A1 receptors (Brown & Dale, 2000). However, until now no investigation has been made of the agonist activity of ADP. The present study shows that it is just as effective at modulating K+ currents as ATP. This has important implications for the purinergic modulatory scheme. While the kinetics of the conversion of ATP by ectoATPases have not been directly studied in Xenopus spinal cord, in other tissues this first step proceeds very rapidly. ADP may therefore accumulate in the extracellular space to a greater degree than ATP itself suggesting that this molecule could play an important signalling role under physiological conditions.

Additionally, we have demonstrated that the ADP analogue α,β-methylene-ADP, often used as a blocker of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase, is effective as an agonist at the p2y1 receptor. This result fits into a pattern for the pharmacological tools used for investigating P2 receptors. Several antagonists active at P2 receptors also exhibit an ability to inhibit ectonucleotidases (cf. Ziganshin et al. 1996). Our finding is the converse - an antagonist of the ecto-5′-nucleotidase exhibits agonist action at the P2 receptor.

Dale & Gilday (1996) previously reported that α,β-methylene-ADP prolonged swimming episodes and interpreted this as occurring through an inhibitory action on the ecto-5′-nucleotidase. However, we have now demonstrated that this is not the case: the Xenopus ecto-5′-nucleotidase is not inhibited by α,β-methylene-ADP which acts instead as a p2y agonist. We now re-interpret our previous results and suggest that activation of the p2y1-like receptor in Xenopus is sufficient to increase the excitability of the spinal motor networks and thus enhance the length of swimming episodes. Given this dual action greater caution should be exercised in future over the interpretation of the physiological actions of α,β-methylene-ADP.

Modulation of K+ currents

P2 receptors play an important regulatory role over motor pattern generation as their blockade by PPADS or suramin greatly shortens the length of swimming episodes (Dale & Gilday, 1996). The modulation of K+ currents reported here by the likely natural agonists, ATP and ADP, was 8–10 %. This is slightly lower than that previously reported for ATP (∼13 %, Dale & Gilday, 1996) and may be somewhat artificially low because receptors may be lost or inactivated during the dissociation procedure. Nevertheless modulation of K+ currents by 10–20 % is capable of exerting considerable modulatory control over the motor pattern-generating network in computer simulations (especially when combined with parallel modulation of Ca2+ currents mediated by adenosine - Dale & Gilday, 1996; Dale, 1998). Furthermore experimental evidence shows that the spinal circuitry is remarkably sensitive to blockade of K+ channels (Wall & Dale, 1994; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). For example, blockade by non-specific agents such as TEA and 3,4-diaminopyridine by as little as 25 % of the total current will disrupt motor pattern generation. Thus, although small, the modulation of K+ currents reported here probably exerts significant control over the operation of the spinal motor circuits.

While the inhibition of K+ currents will reduce the threshold of the neurons and hence enhance overall circuit excitability, the contrasting roles of the fast and slow components of the delayed rectifier in generating motor activity make it important to establish the control exerted over each by p2y receptor activation. Both modelling and pharmacological studies suggest that the fast K+ current (about 80 % of the total current) affects spike threshold and width without markedly controlling the repetitive firing characteristics of these neurons (Dale, 1995b; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). The slowly activating K+ current by contrast has little effect on spike width but does indeed control repetitive firing and has a powerful action on threshold (Dale, 1995b; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). We have demonstrated that the modulatory effects are entirely confined to the fast, catechol-sensitive component of the delayed rectifier.

It is perhaps surprising that the slow current is not modulated by the p2y receptors since this current is a powerful determinant of circuit operation. However it may be too powerful - pharmacological blockade of this small current by about 40 % (equating to a reduction of around 10 % of the total outward current) rather easily disrupts swimming activity (Dale, 1995b; Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). Clearly a control system needs to exert subtle regulation that allows the circuit to function correctly throughout the entire range of control. The fast current, although a weaker determinant of threshold, may be a better site of action for modifying the operation of spinal circuits. The spinal circuits can maintain correctly patterned operation with up to 50 % of the fast current selectively blocked (Kuenzi & Dale, 1998). The modest modulation reported here (∼10 %) will not endanger the integrity of circuit function but will allow more subtle time-dependent control of the circuit. This would remain true even if, as seems probable, our recordings with isolated neurons underestimate the true extent of modulation of the K+ currents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust for generous support.

REFERENCES

- Bogdanov YD, Dale L, King BF, Whittock N, Burnstock G. Early expression of a novel nucleotide receptor in the neural plate of Xenopus embryos. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:12583–12590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Filippov AK, Barnard EA. Inhibition of potassium and calcium currents in neurones by molecularly-defined P2Y receptors. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 2000;81:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(00)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Dale N. Adenosine A1 receptors modulate high voltage-activated Ca2+ currents and motor pattern generation in the Xenopus embryo. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:655–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. The isolation and identification of spinal neurons that control movement in the Xenopus embryo. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;3:1025–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. A large, sustained Na+-dependent and voltage-dependent K+ current in spinal neurons of the frog embryo. Journal of Physiology. 1993;462:349–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. Kinetic characterization of the voltage-gated currents possessed by Xenopus embryo spinal neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1995a;489:473–488. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. Experimentally derived model for the locomotor pattern generator in the Xenopus embryo. Journal of Physiology. 1995b;489:489–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N. Delayed production of adenosine underlies temporal modulation of swimming in frog embryo. Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.265bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale N, Gilday D. Regulation of rhythmic movements by purinergic neurotransmitters in frog embryos. Nature. 1996;383:259–263. doi: 10.1038/383259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EL, Pearson JD, Slakey L. The hydrolysis of extracellular adenine nucleotides by cultured endothelial cells from pig aorta. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:15496–15504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi Y, Nishizaki T. The P2Y purinoceptor-operated potassium channel is possibly regulated by the beta gamma subunits of a pertussis toxin-insensitive G-protein in cultured rat inferior colliculus neurons. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;214:589–596. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi Y, Nishizaki T. ATP-regulated K+ channel and cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization in cultured rat spinal neurons. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;302:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi Y, Nishizaki T, Mori M, Okada Y. Regulation of the potassium current and cytosolic Ca2+ release induced by 2-methylthio ATP in hippocampal neurons. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;218:428–433. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S, Richardson PJ. Production of adenosine from extracellular ATP at the striatal cholinergic synapse. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;60:219–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb05841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzi FM, Dale N. The pharmacology and roles of two K+ channels in motor pattern generation in the Xenopus embryo. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:1602–1612. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Tables of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) Amsterdam: North Holland; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacological Reviews. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SJ, Ennion SJ, Evans RJ, Edwards FA. Synaptic P2X receptors. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11:378–386. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsberg PD, Loo TL. Simultaneous analysis of ATP, ADP, AMP and other purines in human erythrocytes by high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography. 1980;181:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ, Dale N. Differential inhibition of N and P/Q Ca2+ currents by 5-HT1A and 5-HT1D receptors in spinal neurons of Xenopus larvae. Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:103–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.103bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera S, Hussy N, Evans RJ, Adami N, North RA, Surprenant A, Buell G. A new class of ligand-gated ion channel defined by P2x receptor for extracellular ATP. Nature. 1994;371:516–519. doi: 10.1038/371516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Kugelgen I, Wetter A. Molecular pharmacology of P2Y-receptors. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 2000;362:310–323. doi: 10.1007/s002100000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MJ, Dale N. A role for potassium currents in the generation of the swimming motor pattern of Xenopus embryos. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1994;72:337–348. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MJ, Dale N. A slowly activating Ca2+-dependent K+ current that plays a role in termination of swimming in Xenopus embryos. Journal of Physiology. 1995;487:557–572. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TE, Simon J, Krishek BJ, Bateson AN, Smart TG, King BF, Burnstock G, Barnard EA. Cloning and functional expression of a brain G-protein-coupled ATP receptor. FEBS Letters. 1993;324:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81397-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziganshin AU, Ziganshina LE, King BF, Pintor J, Burnstock G. Effects of P2-purinoceptor antagonists on degradation of adenine nucleotides by ecto-nucleotidases in folliculated oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1996;51:897–901. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Biochemistry, localization and functional roles of ecto-nucleotidases in the nervous system. Progress in Neurobiology. 1996;49:589–618. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(96)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]