Abstract

Effects of adenosine on voltage-gated Ca2+ channel currents and on arginine vasopressin (AVP) and oxytocin (OT) release from isolated neurohypophysial (NH) terminals of the rat were investigated using perforated-patch clamp recordings and hormone-specific radioimmunoassays. Adenosine, but not adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), dose-dependently and reversibly inhibited the transient component of the whole-terminal Ba2+ currents, with an IC50 of 0.875 μm. Adenosine strongly inhibited, in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 = 2.67 μm), depolarization-triggered AVP and OT release from isolated NH terminals. Adenosine and the N-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA, but not other Ca2+ channel-type antagonists, inhibited the same transient component of the Ba2+ current. Other components such as the L-, Q- and R-type channels, however, were insensitive to adenosine. Similarly, only adenosine and ω-conotoxin GVIA were able to inhibit the same component of AVP release. A1 receptor agonists, but not other purinoceptor-type agonists, inhibited the same transient component of the Ba2+ current as adenosine. Furthermore, the A1 receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT), but not the A2 receptor antagonist 3, 7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPGX), reversed inhibition of this current component by adenosine. The inhibition of AVP and OT release also appeared to be via the A1 receptor, since it was reversed by CPT. We therefore conclude that adenosine, acting via A1 receptors, specifically blocks the terminal N-type Ca2+ channel thus leading to inhibition of the release of both AVP and OT.

ATP is known to affect several biological functions (see reviews by Burnstock, 1978; El-Monatassim et al. 1992) including neurotransmission (Ribeiro, 1978; Burnstock, 1978, 1996; White, 1988; Fieber & Adams, 1991; Evans et al. 1992; Edwards & Gibb, 1993; Wu & Saggau, 1994; Zimmermann, 1994; Kennedy et al. 1996), secretion (Diverse-Pierluissi et al. 1991; Gandia et al. 1993; Currie & Fox, 1996; Harkins & Fox, 2000) and vascular contraction (Kolb & Wakelam, 1983; Katsuragi & Su, 1980). The modulation by ATP of pre-synaptic ion channels (Zimmermann, 1994) via specific purinergic receptors, for example, could result in changes in subsequent release of neurotransmitters from the pre-synaptic site and, as a consequence, on the functional effect at the post-synaptic site.

ATP is rapidly hydrolysed by ecto-nucleotidases (Gordon et al. 1989) even at pre-synaptic sites (Thirion et al. 1996) to adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP) and adenosine. Adenosine, the final hydrolysed metabolite of ATP (Gordon et al. 1989; Kennedy et al. 1996; see review by Rathbone et al. 1999), is another strong neuromodulator that may interact with another group of specific receptors at pre- (White, 1988; Scanziani et al. 1992; Yawo & Chuhma, 1993; Umemiya & Berger, 1994; Wu & Saggau, 1994) or post-synaptic sites (Rathbone et al. 1999). These adenosine receptors belong to a family of receptors including A1, A2 and A3 subtypes (Reppert et al. 1991) that are distinct from those purinergic receptors specifically activated by ATP (see reviews by Dalziel & Westfall, 1994; Fredholm et al. 1994; Rathbone et al. 1999). Despite an accumulation of evidence that adenosine acts as an auto-modulator via these pre-synaptic receptors to exert negative feedback, no direct evidence has demonstrated mechanisms by which it modulates such pre-synaptic functions. In order to address this issue, we utilized the rat NH as an example of central ‘pre-synaptic’ nerve terminals, since endogenous ATP was reported to be co-stored with the neuropeptides AVP and OT in their large neurosecretory vesicles (Troadec et al., 1998; Sperlagh et al. 1999) and hydrolysed by ecto-nucleotidases to adenosine (Thirion et al. 1996).

Ca2+ entry into pre-synaptic nerve terminals is required for triggering exocytotic release of neurotransmitters/ hormones (Llinas et al. 1981; Augustine et al. 1985; Turner et al. 1993; Reuter, 1995). It has been established that during depolarization-secretion coupling in NH terminals, Ca2+, acting as a second messenger, flows into these nerve terminals via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and consequently evokes neurohormone release (Brethes et al. 1987; Dayanithi et al. 1987; Wang et al. 1993). There are four subtypes of high voltage-threshold Ca2+ channels in the rat NH terminals: L- (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989), N- (Wang et al. 1992b), P/Q- (Wang et al. 1997) and R-types (Wang et al. 1999). While the L- and N-type Ca2+ channel currents play equivalent roles in AVP and OT release, Q-and R-type Ca2+ channel currents preferentially control AVP vs. OT release (Wang et al. 1997, 1999).

We measured voltage-gated ion channel currents and hormone release in order to determine if they were affected by exogenously applied adenosine or specific agonists/antagonists of purinoceptors (Thirion et al. 1996; Troadec et al. 1998; Sperlagh et al. 1999; Loesch et al. 1999; Lemos & Wang, 2000). We found that adenosine exerted significant effects on both N-type Ca2+ channel currents (Wang & Lemos, 1995) and peptide release from these terminals.

METHODS

Electrophysiology

Isolation of nerve terminals

Experiments were conducted on freshly dissociated NH nerve terminals of male adult (6–8 weeks) CD rats (Charles River Laboratory, Boston, MA, USA). Briefly, as previously described (Cazalis et al. 1987), the rat, after anaesthetization by a high concentration of CO2, was decapitated (as approved by University of Massachusetts Medical School protocol A-1031), the brain was removed and the pituitary gland then excised. The NH, after being carefully separated from the anterior pituitary and the pars intermedia, was homogenized in the following solution (mm): sucrose, 270; Tris-Hepes, 10; EGTA, 0.01; pH 7.2. The isolated terminals were then placed in a 35 mm Petri dish coated with 0.1 % poly-l-lysine and perfused with normal-Ca2+ Locke solution containing (mm): NaCl, 145; KCl, 5; CaCl2, 2.2; MgCl2, 1; Tris-Hepes, 10; glucose, 15; pH 7.3. The nerve terminals could be identified using an inverted microscope equipped with phase and Hoffman-modulated contrast optics (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Only terminals 7–9 μm in diameter were chosen for patch-clamping. The electrophysiological experiments were all done at room temperature, 22–24 °C and the release experiments were performed at 37 °C.

Whole-terminal patch-clamp recording

After approximately 1 h of perfusion with normal-Ca2+ Locke solution, nerve terminals were then perfused with Ba2+ solution (mm): TEA-Cl, 100; NaCl, 30; BaCl2, 5; KCl, 5; MgCl2, 1; Tris-Hepes, 10; glucose, 15; pH 7.3. In these experiments, the pipette solution for amphotericin B-perforated (Rae et al. 1991; Lemos & Wang, 1993; Wang et al. 1997, 1999), whole-terminal patch-clamp contained (mm): caesium glutamate, 135; TEA-Cl, 20; Tris-Hepes, 10; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; glucose, 5; pH 7.2, including amphotericin B, 30 μg ml−1. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Most of the terminals were raised from the bottom of the Petri dish after GΩ seal formation so that the entire area of their membrane would have direct contact with the perfusion medium. While the perforation was developing, the capacitance of the terminal gradually increased. Those terminals with access resistances less than 35 MΩ of the perforated-patch membrane were then chosen for the Ca2+ channel current recordings. Using the perforated-patch (Rae et al. 1991), ‘whole-terminal’ configuration (Hamill et al. 1981), the amplitude of the Ba2+ current (IBa) was usually stable for more than 30 min without any rundown problems. This allowed us to sequentially apply specific Ca2+ channel blockers and test specific agonists/antagonists. The L-type channel is long-lasting and very sensitive to dihydropyridines (DHP) (Nowycky et al. 1985; Fox et al. 1987; Tsien et al. 1988; Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Wang et al. 1992; Wang et al. 1997, 1999). The N-, P/Q- and R-type Ca2+ channel currents, however, are transient and can be identified pharmacologically by their sensitivity to selective peptide toxins (Nowycky et al. 1985; Fox et al. 1987; Tsien et al. 1988; Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Turner et al. 1992; Mintz et al. 1992a, b; Wang et al. 1992b; Sather et al. 1993; Stea et al. 1994; Wheeler et al. 1994; Wang & Lemos, 1994; Wang et al. 1997, 1999; Newcomb et al. 1998).

Membrane currents were recorded by an EPC-7 amplifier (List Electronics, Germany) and were filtered at 3 kHz corner frequency, −3 dB, with an 8-pole Bessel filter (902LPF, Frequency Devices Inc., Haverhill, MA, USA) and stored on high-density disks for later analysis. pCLAMP computer software (Axon Instruments, Inc., Union City, CA, USA) and an A-D converter (Scientific Solutions, Solon, OH, USA) were used to generate command voltage potentials. The resistances of soft glass pipettes (Drummond Scientific Co., PA, USA), which had been double-pulled (Model 700C, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA), Sylgard-coated, and fire-polished (Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab., Tokyo, Japan), were 2–3 MΩ.

Data analysis

pCLAMP computer software (versions 5 and 6) was used for the acquisition and analysis of the data. In most cases, the leakage currents were subtracted from the total currents in order to analyse the pure inward IBas. The amplitude of IBa at the end of the 200 ms steps was considered to be that of the long-lasting component of the IBa and the difference in amplitude between this component of IBa and the peak IBa is considered to be that of the transient IBa (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989). Data are given as means ± s.e.m. Student's t test was used to examine statistical significance of paired or unpaired data, as indicated.

Drugs

Adenosine, ATP, 2-methylthio-ATP tetrasodium (2Met-ATP), 2-chloroadenosine (2-CA), N-0840, DMPGX, CPT and the DHP nicardipine were all purchased from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, USA). The polypeptide toxins SNX-482, ω-conopeptides GVIA and MVIIC utilized in this study were the synthetic versions, prepared by Neurex Pharmaceutical Corporation (Palo Alto, CA, USA; see Wang et al. 1997, 1999). The synthetic version of ω-AgaIVA (Mintz et al. 1992a, b) was purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, KY, USA).

Assay of peptide release

The nerve endings were prepared as previously described (Cazalis et al. 1987; Wang et al. 1997). Briefly, rat neurohypophyses were homogenized in a solution containing (mm): sucrose, 270; Tris-Hepes, 10 (pH 7.25); EGTA, 2. The homogenate was centrifuged at 100 g for 2 min and the resulting pellet was centrifuged at 2400 g for 6 min. The final pellet contains highly purified nerve terminals. The isolated nerve terminals were loaded onto filters (0.45 μm Acrodisc, Gelman Scientific, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and perfused at 37 °C with Locke solution (Dayanithi et al. 1987). Fractions of perfusate were collected at 2 min intervals and the evoked release was triggered by an eight minute long pulse of a depolarizing concentration (50 mm) of KCl. The results are given as AVP or OT release per fraction measured using specific radioimmunoassays (Cazalis et al. 1987; Dayanithi et al. 1987). The medium before and after the depolarizing period contained (mm): NaCl, 40; KHCO3 5; N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG)-Cl2, 100; MgCl2, 1; CaCl2, 2; glucose, 10; Tris-Hepes, 10 (pH 7.2) with 0.02 % BSA. Depolarization medium contained 50 mm K+, in which the NMG was reduced to maintain the osmolarity (300–305 mOsmol).

RESULTS

Adenosine dose-dependently inhibits the transient Ba2+ currents in NH terminals

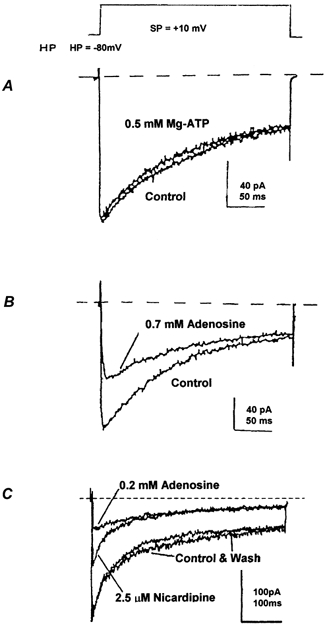

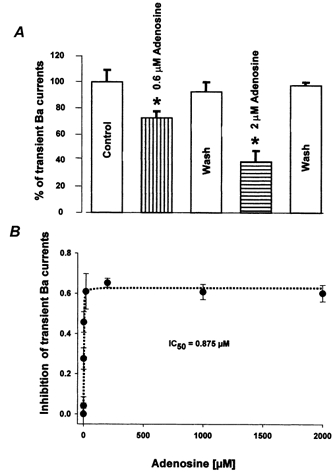

We examined the effects of adenosine on voltage-gated Ca2+ channel currents in isolated NH nerve terminals of the rat. There are four subtypes of high threshold-voltage-activated Ca2+ channel currents: L, N and P/Q or R in these nerve terminals (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Wang et al. 1992b, 1997, 1999; Wang & Lemos, 1992, 1994). While the L-type current is long lasting, the N-, P/Q- and R- types are transient currents (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Wang et al. 1992b, 1997, 1999). We observed that ATP exerted little influence (−9.2 ± 5.2 %; n = 3) on Ba2+ current at doses as high as 0.5 mm (Fig. 1A) to 1 mm (Wang & Lemos, 1995). In contrast, 0.2–0.7 mm adenosine specifically inhibited (by 61.2 ± 12 %; n = 3) the transient part of whole-terminal Ba2+ currents (Fig. 1B and C). Even very low (0.6 μm) concentrations of adenosine displayed a significant inhibitory effect (−27.5 ± 5.3 %; n = 4) on the transient component of whole-terminal Ba2+ currents (Fig. 2A). When increased to 2 μm and above, the effects of adenosine on this transient Ba2+ current appear to be saturated at approximately 37 % (36.8 ± 2.9 %; n = 9) of controls, with an IC50 of 0.875 μm (Fig. 2B). This inhibition is reversible upon washing with the adenosine-free control buffer (Figs. 1C and 2A).

Figure 1. Adenosine inhibits the transient Ba2+ current in NH terminals.

The transient component of whole-terminal Ba2+ currents elicited from − 80 mV to +10 mV (see protocol above) using the perforated-patch method was strongly and specifically inhibited by 0.7 mm adenosine (B), but not by 0.5 mm ATP (A). C, representative traces of the whole-terminal Ba2+ currents also elicited from − 80 mV to +10 mV in a different isolated NH terminal. The L-type Ca2+ channel current was first blocked by a saturating concentration (2.5 μm) of nicardipine (Wang et al. 1997, 1999). Further application of 0.2 mm adenosine led to a reversible (wash) inhibition of the nicardipine-resistant, transient Ba2+ current. Dotted lines represent baseline currents.

Figure 2. Adenosine dose-dependently inhibits the transient Ba2+ current in nerve terminals.

A, the isolated transient component (see Fig. 1C) of NH Ba2+ currents was dose-dependently and reversibly inhibited by low concentrations (0.6 − 2 μm) of adenosine. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of adenosine on the isolated transient current were reversible upon washing (Wash). * Significant (P < 0.05) differences from controls in this and all subsequent figures. B, dose-response curve for the effects of adenosine on the transient Ba2+ current in the nerve terminals indicates an IC50 of 0.875 μm. Dotted line represents Lineweaver-Burk fit (r2 = 0.97) to the data (expressed as means ± s.e.m., n = 3–5).

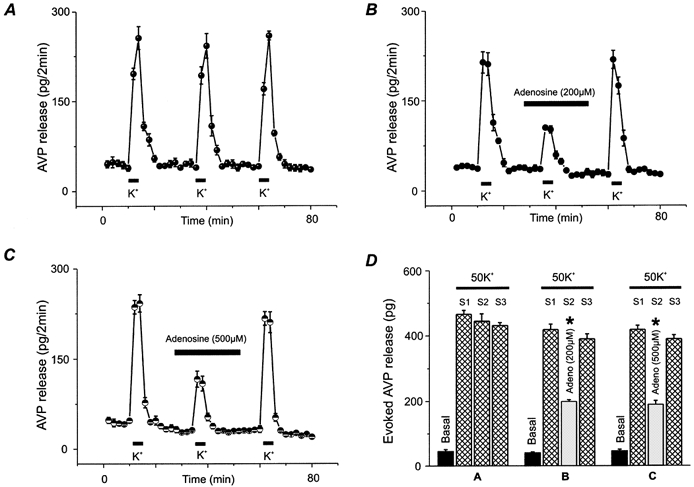

Adenosine dose-dependently inhibits peptide release from NH terminals

In order to determine if the metabolite of ATP, adenosine, could modulate neurosecretion, we measured AVP and OT release, using specific radioimmunoassays, from isolated, perfused NH terminals (Dayanithi et al. 1987). Figure 3A shows repeated stimulations (S) with 50 mm K+ that gave, each time, essentially identical AVP release profiles, (basal = 45 ± 6 pg; evoked S1 = 466 ± 12 pg; S2 = 443 ± 15 pg; S3 = 431 ± 9 pg; n = 5). The Ca2+-dependent AVP release was strongly inhibited by 200 μm adenosine (Fig. 3B; basal = 40 ± 3 pg; evoked S1 = 418 ± 7 pg; S2 = 196 ± 6pg; S3 = 390 ± 15 pg; n = 5), but not even higher (500 μm) concentrations were able to completely block the stimulated release (basal = 44 ± 5 pg; evoked S1 = 418 ± 13 pg; S2 = 189 ± 12pg; S3 = 390 ± 12 pg; n = 5) (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the maximal proportion (42 %) of release affected by adenosine correlates well with the proportion (35 %) regulated by the N-type Ca2+ current (Wang et al. 1997, 1999).

Figure 3. Effects of adenosine on the release of AVP from isolated rat NH nerve terminals.

A, AVP release was stimulated (S) for 8 min by 50 mm KCl (K+) repeated at three regular time intervals. B, nerve terminals were challenged with high K+ either in the absence (S1 & S3) or in the presence (S2) of 200 μm adenosine as indicated by the bar above the data points. All drugs were present for 20 min before, during and after high K+ challenges. C, similarly, in order to further characterize this action on Ca2+-dependent peptide release, 500 μm adenosine was added 20 min before and during the second stimulus (S2). All traces represent the mean of 4–6 experiments ± s.e.m.D, bar graph summarizes basal and evoked release for panels A, B and C expressed as means ± s.e.m., n = 4–6.

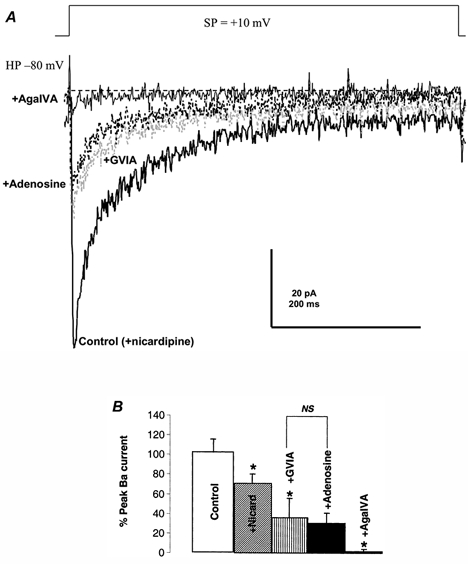

Adenosine inhibits the N-type component of Ca2+ currents

In an effort to determine which Ca2+ current subtype is specifically blocked by adenosine, pharmacological protocols known to differentiate between the terminal Ca2+ channel types (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Wang et al. 1992b, 1997, 1999) were utilized. As already shown in Fig. 1C, the DHP Ca2+-channel antagonist nicardipine (2.5 μm) selectively inhibited the long-lasting component of the Ba2+-current in these isolated NH terminals, in agreement with previous reports (Lemos & Nowycky, 1989; Wang et al. 1997, 1999). In the presence of 2.5 μm nicardipine, the total peak NH Ba2+ current was decreased from 100 ± 34.3 % (n = 7) to 71.1 ± 9.1 % (n = 4). Subsequent addition of 2 μm adenosine still led to rapid inhibition of a large proportion (36.5 ± 10.3 %; n = 7, P < 0.05) of the remaining transient component of the Ba2+-current, suggesting that the L-type Ca2+ current was not involved in the inhibition by adenosine.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4A, after blocking the L-type current (control), upon addition of the specific N-type channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA a large portion (69.5 ± 6.5 %; n = 5) of the NH transient Ba2+ current was reduced. Subsequent addition of even saturating (0.5–2 mm) concentrations of adenosine (n = 6) did not significantly affect the remaining current. Addition of 450 nm ω-AgaIVA could, however, completely block (by 98.1 ± 2.1 %) the remaining P/Q type component of the Ba2+ current (Wang et al. 1997, 1999).

Figure 4. The transient Ba2+ current blocked specifically by adenosine is the N-type Ca2+ channel.

A, the isolated transient Ba2+ current was elicited by stepping from −80 to +10 mV (SP) in the presence of 2.5 μm nicardipine (control). Saturating concentrations (800 nm) of the N-type channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA (grey, dotted line) were used to block the N-type Ca2+ current in this nerve terminal. Not even very high concentrations (2000 μm) of adenosine (black, dotted line) had any significant effect on the ω-conotoxin GVIA-resistant, transient Ba2+ current. This nicardipine-, ω-conotoxin GVIA- and adenosine-resistant Ba2+ current is, however, sensitive to high concentrations (450 nm) of ω-AgaIVA. B, bar graph summarizes multiple (n = 4–7) effects observed as in A. NS, no significant differences between indicated conditions in this and all subsequent figures (P > 0.05).

In other experiments in the presence of nicardipine, addition of saturating (0.5–2 mm) concentrations of adenosine could induce a further decrease in the peak NH Ba2+ current from 71.1 ± 9.1 % (n = 4) to 34.6 ± 20.3 % (n = 7, P < 0.05). Furthermore, application of even a saturating concentration (800 nm) of ω-conotoxin GVIA (Wang et al. 1992b) failed to significantly (n = 4, P > 0.05) inhibit the nicardipine- and adenosine-resistant component of the NH Ba2+ current, which was changed from 34.6 ± 20.3 % in the presence of nicardipine and adenosine (n = 7) to 25.8 ± 10.2 % in the presence of ω-conotoxin GVIA. Application of P/Q-type channel (Mintz et al. 1992a, b) blockers ω-AgaIVA (450 nm) or ω-MVIIC (100 nm), however, could eventually reduce the remaining Ba2+ current from 25.8 ± 10.2 % (n = 4) to 2.2 ± 2.0 % (n = 3).

This inhibition of the nicardipine- and adenosine-resistant transient Ca2+ current component by both low concentrations of SNX-482 (by 95 %; n = 2), a specific R-type Ca2+ channel blocker (Wang et al. 1999), and high concentrations of ω-AgaIVA (Fig. 4B; n = 4) lead us to conclude that adenosine cannot inhibit the Q- or R-type channel (Wang et al. 1997, 1999). In addition, neither ATP nor adenosine had any significant effect on the L-type current (see above). Finally, since the effects of ω-conotoxin GVIA and adenosine are not additive, it appears that adenosine specifically blocks only the N-type channel in NH terminals (Wang & Lemos, 1995).

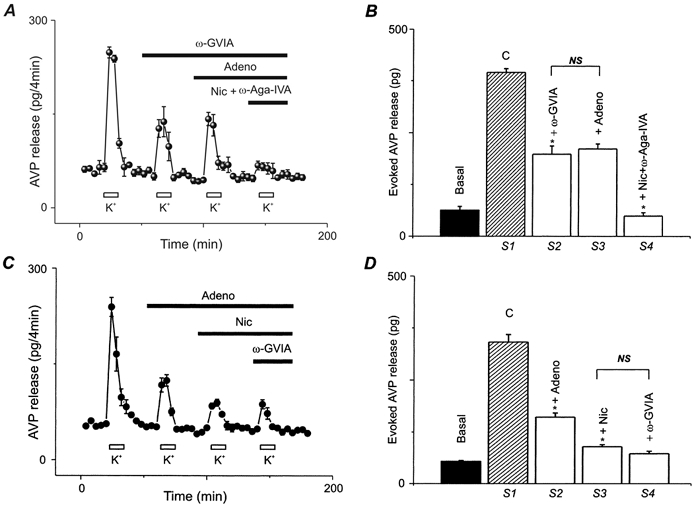

Adenosine only inhibits the N-type component of AVP release

In order to check for the involvement of N-type Ca2+ channels in the inhibition of AVP release by adenosine, we performed two different sets of experiments. Figure A and B shows that the high K+-evoked release (395 ± 9 pg; n = 4) was significantly (P < 0.01) inhibited (198 ± 20 pg) by the N-type channel antagonist, ω-conotoxin GVIA (Kasai et al. 1987; Hirning et al. 1988; Wang et al. 1997) and that 200 μm adenosine did not further inhibit AVP release (211 ± 12 pg). However, additional inhibition could be achieved (49 ± 8 pg) by application of L- and P/Q-type channel blockers (nicardipine and ω-AgaIVA). Similarly, we have confirmed these results by reversing the order of application of adenosine, and the L- and N-type Ca2+ channel blockers (see Fig. 5C and D). The high K+-evoked AVP release (341 ± 18 pg; n = 4) inhibited by adenosine (161 ± 10 pg) and further inhibited (90 ± 5 pg) by nicardipine, an L-type channel blocker, was not affected (73 ± 6 pg) by GVIA, an N-type channel blocker.

Figure 5. Effect of Ca2+ channel blockers and adenosine on AVP release.

A, nerve terminals were challenged for 8 min with 50 mm K+ repeated at four regular time intervals either in the absence (S1) or in the presence of 800 nm ω-conotoxin GVIA (S2), plus 200 μm adenosine (S3), plus 1 μm nicardipine and 450 nm of ω-AgaIVA (S4) as indicated by the bars above the data points. All blockers were present for at least 16 min before, during, and after each K+ challenge. C, similar experiments were performed, but by applying first adenosine (S2), followed by addition of nicardipine (S3) and then ω-conotoxin GVIA (S4). All drugs were present for at least 16 min before, during and after each high K+ challenge. All traces represent the mean of 4–6 experiments ± s.e.m.B and D, bar graphs summarizing basal and evoked release for A and C expressed as means ± s.e.m., n = 4–6.

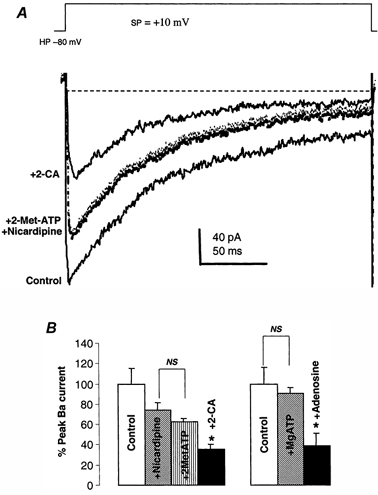

A1 receptor mediates the inhibition by adenosine of the N-type Ca2+ current

In order to determine which receptor subtype is involved in inhibition of the whole terminal Ca2+ channels, we then examined the effects on the Ba2+ currents of several purinergic receptor subtype agonists, such as the adenosine A1 receptor agonist 2-chloroadenosine (2-CA; Fredholm et al. 1994), the A2 receptor agonist 2-phenylamino-adenosine (White, 1988), and the P2Y receptor agonist 2-methylthio-ATP tetrasodium (2Met-ATP) (Zimmerman, 1994).

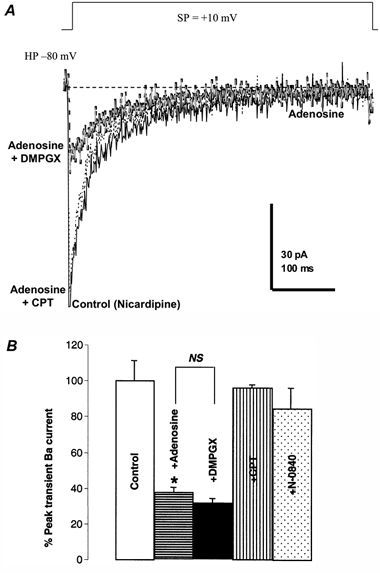

2Met-ATP (Fig. 6; n = 4), 2-phenylamino-adenosine (data not shown; n = 2), and Mg-ATP (Fig. 1A and Fig. 6B; n = 3) were all ineffective on the whole-terminal Ba2+ currents resistant to nicardipine. In contrast, the A1 agonist 2-CA, at 20–100 μm concentrations, had effects (−64.7 ± 5 %; n = 5) similar to those of adenosine (−61.7 ± 12.2 %; n = 3) on the transient Ba2+ current in the nerve terminals (Fig. 6A and B). In addition, as shown in Fig. 7, only the A1 receptor antagonist CPT (n = 8), but not the A2 receptor antagonist DMPGX (n = 3), could reverse the inhibition by adenosine (n = 9) of the transient Ba2+ current in the nerve terminals. By themselves, neither CPT (−4.1 ± 1.7 %) nor DMPGX (−6.2 ± 8.2 %) had any substantial effect on the transient Ba2+ current in the nerve terminals. The receptor agonist/antagonist data thus indicate that the activation of an A1 receptor mediates the inhibition of the N-type Ca2+ channel by adenosine.

Figure 6. Only A1 receptor agonists inhibit the N-type Ca2+ current in these nerve terminals.

A, representative traces of Ba2+ currents (control) from a single isolated nerve terminal demonstrate that the long-lasting component of the terminal current is partially blocked by a saturating concentration (2.5 μm) of nicardipine. The purinergic (P1) receptor agonist 2Met-ATP (at 20 μm) had no significant effect on the nicardipine-resistant Ba2+ current, but 20 μm 2-CA did inhibit it. The remaining current was due to the Q-type Ca2+ channel, since it was blocked by 100 μm ω-MVIIC (data not shown). B, statistical summary of the effects illustrated in A on the macroscopic Ba2+ currents. Only 2-CA shows a significant inhibition of the nicardipine-resistant transient Ba2+ currents in NH terminals. Furthermore, 20 μm adenosine had a significant effect on the current, whereas 1 mm Mg-ATP did not.

Figure 7. The Ba2+ currents inhibited by adenosine could be reversed by an A1, but not an A2, antagonist.

A, the whole-terminal Ba2+ currents were elicited from −80 to +10 mV in the presence of 2.5 μm nicardipine (control trace). Adenosine (20 μm) was applied to inhibit the Ba2+ current (black, dashed trace). Addition of 20 μm DMPGX, an A2 receptor antagonist, could not reverse the inhibition by adenosine of the transient current (grey trace). However, further addition of 20 μm CPT, an A1 receptor antagonist, almost completely reversed this inhibition (dotted line). B, statistical summary of the effects illustrated in A on the macroscopic Ba2+ currents. Only CPT shows a significant inhibition of the inhibition by adenosine of transient Ba2+ currents in NH terminals. Furthermore, 20 μm N-0840, another A1 antagonist, had similar effects.

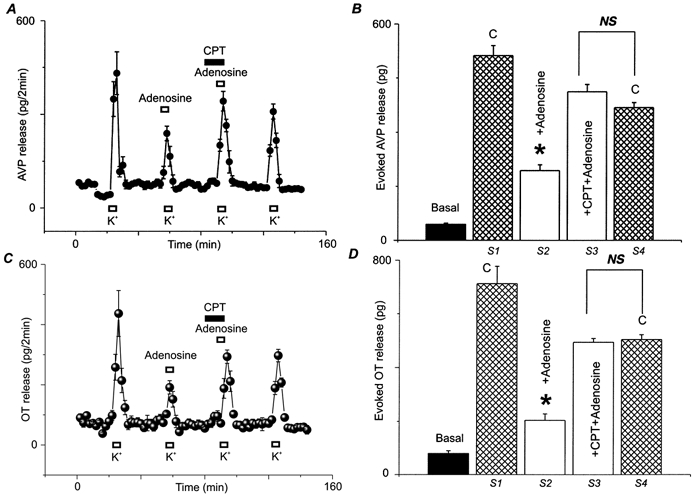

A1 receptor mediates adenosine inhibition of peptide hormone release

In an effort to determine what purinoceptor might mediate the effects of adenosine on AVP and OT release we attempted to block the inhibition by adenosine with various antagonists. Even lower concentrations (20 μm) of adenosine were able to significantly (P < 0.01) inhibit both high K+ stimulated AVP (Fig. 8A; basal release = 44 ± 4 pg; 50 mm K+ = 512 ± 28 pg; plus adenosine = 194 ± 16 pg; n = 4;) and OT release (Fig. 8C; basal = 80 ± 10 pg; 50 mm K+ = 712 ± 65 pg; plus adenosine = 204 ± 24 pg; n = 4;), and this inhibition could be reversed only by A1-antagonists, such as CPT (Fig. 8B and D; recoveries of 93.2 ± 4.8 % for AVP and 87.5 ± 3 % for OT) or N-0840 (84.8 ± 10.7 % recovery; n = 3), but not by the A2-antagonist, DMPGX (2.7 ± 5 %; n = 3). Taken together, the release results demonstrate an apparent IC50 of 2.67 μm for adenosine. This correlates reasonably well with the electrophysiological data (see above), suggesting that the N-type Ca2+ channel component mediates the action of adenosine via A1-receptors on depolarization-secretion coupling in these central nervous system terminals.

Figure 8. Effects of adenosine on the release of AVP and OT from isolated rat NH nerve terminals could be reversed by an A1 antagonist.

AVP (A) and OT (C) release was stimulated (S) for 4 min by 50 mm KCl (K+) repeated four times (S1–4) at regular time intervals. Nerve terminals were challenged with high K+ either in the absence (S1, S4) or in the presence (S2, S3) of 20 μm adenosine. Preincubation with 20 μm CPT, an A1 receptor antagonist, almost completely reversed the inhibition by adenosine (S3). All drugs were present as indicated by bars above each high K+ challenge. B and D, basal and evoked release summarized for AVP and OT, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This paper reports a role for purines as modulators of both ionic channels and peptide hormone secretion from the isolated nerve terminals of the rat NH. The ATP metabolite, adenosine, appears to inhibit Ca2+-dependent secretion of AVP and OT via an A1 receptor. This is in contrast with previous results that ATP can stimulate Ca2+-dependent secretion of neurotransmitters/ neurohormones from neurons or endocrine secretory cells (Evans et al. 1992; Scanziani et al. 1992; Zimmermann, 1994; Troadec et al. 1998), but could explain why ATP appeared to inhibit AVP release from intact neurohypophyses (Sperlagh et al. 1999).

In fact, the effects of ATP and adenosine are not always easily distinguished. Added to a tissue preparation, ATP is hydrolysed by ecto-nucleotidases and, thus, might act via any of the metabolites formed. ATP released from a tissue might be hydrolysed to adenosine before it appeared in the perfusate and thus ATP effects might be mistaken for those of adenosine (El-Monatassim et al. 1992; Zimmermann, 1994). In the case of the NH nerve terminals, the surface-located ecto-nucleotidases, including ecto-ATPase, ecto-ADPase and ecto-5′nucleotidase, responsible for hydrolysis of ATP have been found at sites of ATP release (Thirion et al. 1996). The end product of ATP hydrolysis is generally adenosine, which is also a signalling substance (Burnstock, 1978). The fact that adenosine is a more potent (with an IC50 of 0.87 μm) inhibitor of the transient Ba2+ current than its precursor, ATP (see Figs. 1A and 6B), indicates that this nucleotide could inhibit the Ba2+ current via its metabolite.

Burnstock (1978) was the first to suggest a sub-classification of purinoceptors into two classes: P1 purinoceptors (including A1 and A2 adenosine receptors) with an agonist potency order of adenosine > AMP > ADP > ATP and P2 purinoceptor with a reverse ranking: ATP > ADP > AMP > adenosine. The use of different agonists for these purinergic receptors, some of which are non-hydrolysable, allowed us to distinguish ATP effects from those of adenosine.

Judging from the different potency of adenosine, 2-CA, ATP and 2Met-ATP on the N-type Ca2+ channel currents (Figs 1, 2 and 6), our data strongly suggest that adenosine exerted its reversible effects on the N-type channel through the activation of an A1 purinoceptor on the terminal membrane. Our results obtained from the secretory terminals of NH are in agreement with those found in other neurotransmitter systems, in that adenosine specifically blocks pre-synaptic voltage-gated N-type Ca2+ channels (Yawo & Chuhma, 1993). ATP, however, might also act through another pathway in this model system, which may be coupled to the inhibition of the KCa2+ channel on the terminal membrane (Wang et al. 1992a; Lemos & Wang, 2000). Most importantly, the antagonist data also indicate that the activation of the A1 purinoceptor mediates the adenosine Ca2+ channel block (Fig. 7) and the subsequent inhibition of AVP release (Fig. 8).

Furthermore, it appears that adenosine specifically blocks the transient N-, instead of the Q-, R- or L-type Ca2+ channels in the NH nerve terminals through the activation of A1 adenosine receptors. The exact mechanism by which the signal transduction pathway of cellular responses of NH nerve terminals to extracellular adenosine occurs, however, is still unknown. Nevertheless, in other neuronal systems, activation of purinergic receptors similarly induces an inhibition of neurotransmitter release by pre-synaptic mechanisms, predominantly by blockade of N-type Ca2+ channels via activation of A1 receptors (Yawo & Chuhma, 1993; Mogul et al. 1993; Dittman & Regehr, 1996; Ambrosio et al. 1997; Wu & Saggau, 1997). The mechanisms underlying the inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels in pre-synaptic nerve terminals by adenosine are associated with a second message system, in which a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein (Dolphin & Prestwich, 1985) and protein kinase C (Budd & Nicholls, 1995) may be involved. In contrast to the A1 receptor at pre-synaptic sites, activation of A2 receptor enhances the evoked release of neurotransmitters or hormones (Popoli et al. 1995; Ambrosio et al. 1997; Kumari et al. 1999; Okada et al. 2001) that may involve P/Q-type Ca2+ channels at pre-synaptic sites (Mogul et al. 1993; Umemiya & Berger, 1994).

ATP directly blocks Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the nerve terminal (Lemos & Wang, 2000) and, via a P2X receptor, also increases intraterminal [Ca2+]i (Troadec et al. 1998). These two effects appear to be additive, since the delay in repolarization of the action potential would also result in higher Ca2+ levels in the terminal and, thus, an increase in AVP release, in particular. As shown here, however, any subsequent inhibition is due to the hydrolysed metabolite of ATP, adenosine, which strongly and preferentially inhibits the N-type Ca2+ channel, leading to a decrease in both AVP and OT release.

In conclusion, purinergic modulation of these nerve terminal ion channels, even though complicated by its multiple effects, is physiologically significant. We hypothesize that during depolarization-secretion coupling in the NH terminals, ATP, co-released with the hormones, would initially act locally to block KCa channels (Lemos & Wang, 2000). This would result in a prolongation of action potentials and, via P2X2 receptors, open divalent cation channels (Troadec et al. 1998), both leading to more subsequent Ca2+ entry, and thus, more AVP release. ATP would, meanwhile, be rapidly hydrolysed to adenosine by ecto-nucleotidases bound to the pre-synaptic membrane (Thirion et al. 1996). Adenosine could then act through the A1 receptor to specifically block the N-type Ca2+ channel and decrease the release of both neuropeptides. These dual, conflicting autocrine/paracrine effects of ATP released from NH terminals and its metabolite, adenosine, could help explain (see also Lemos & Wang, 2000) why the levels of AVP vs. OT release are optimized as a result of different physiological patterns of stimulation in vivo (Cazalis et al. 1985). These multiple feedback effects could also have widespread ramifications in terms of CNS synaptic modulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants NS29470 and DA10487.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosio AF, Malva JO, Carvalho AP, Carvalho CM. Inhibition of N-, P/Q- and other types of Ca2+ channels in rat hippocampal nerve terminals by the adenosine A1 receptor. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;340:301–310. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Charlton MP, Smith SJ. Calcium entry and transmitter release at voltage clamped nerve terminals of squid. Journal of Physiology. 1985;369:163–181. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brethes D, Dayanithi G, Letellier L, Nordmann JJ. Depolarization-induced Ca2+ increase in isolated neurosecretory nerve terminals measured with fura-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1987;84:1439–1443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd DC, Nicholls DG. Protein kinase C-mediated suppression of the presynaptic adenosine A1 receptor by a facilitatory metabotropic glutamate receptor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;65:615–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. In: Cell membrane receptors for drugs and hormones, a multidisciplinary approach. Straub RW, Bolis L, editors. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Wood JN. Purinergic receptors: their role in nociception and primary afferent neurotransmission. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1996;6:526–532. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalis M, Dayanithi G, Nordmann JJ. The role of patterned burst and interburst interval on the excitation-coupling mechanism in the isolated rat neural lobe. Journal of Physiology. 1985;369:45–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalis M, Dayanithi G, Nordmann JJ. Hormone release from isolated nerve endings of the rat neurohypophysis. Journal of Physiology. 1987;390:55–70. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie K P M, Fox AP. ATP serves as a negative feedback inhibitor of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel currents in cultured bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1996;16:1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel HH, Westfall DP. Receptors for adenine nucleotides and nucleosides subclassfication, distribution and molecular characterization. Pharmacological Review. 1994;46:449–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayanithi G, Martin-moutot N, Barlier S, Colin DA, Kretz-Zaepfel M, Couraud F, Nordmann JJ. The calcium channel antagonist ω-conotoxin inhibits secretion from peptidergic nerve terminals. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1987;156:255–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Contribution of calcium-dependent and calcium-independent mechanisms to presynaptic inhibition at a cerebellar synapse. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1623–1633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diverse-pierluissi M, Dunlap K, Westhead EW. Multiple actions of extracellular ATP on calcium currents in cultures bovine chromaffin cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;881:1261–1265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC, Prestwich SA. Pertussis toxin reverses adenosine inhibition of neuronal glutamate release. Nature. 1985;316:148–150. doi: 10.1038/316148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Gibb AJ. ATP - a fast neurotransmitter. FEBS Letters. 1993;325:86–89. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Monatassim C, Dornand J, Mani JC. Extracellular ATP and cell signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1134:31–45. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RJ, Derkach V, Surprenant A. ATP mediates fast synaptic transmission in mammalian neurons. Nature. 1992;357:503–505. doi: 10.1038/357503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieber LA, Adams DJ. Adenosine triphosphate-evoked currents in cultured neurones dissociated from rat parasympathetic cardiac ganglia. Journal of Physiology. 1991;434:239–256. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. Kinetic and pharmacological properties distinguish three types of calcium currents in chick sensory neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1987;394:149–172. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Abbracohio MP, Burnstock G, Daly JW, Harden TK, Jacobson KA, Leff P, Williams M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandia L, Garcia AG, Morad M. ATP modulation of calcium channels in chromaffin cells. Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:55–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EL, Pearson JD, Dickinson ES, Moreau D, Slakey LL. The hydrolysis of extracellular adenine nucleotides by arterial smooth muscle cells. Regulation of adenosine production at the cell surface. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:8986–8995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cell and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins AB, Fox AP. Activation of purinergic receptors by ATP inhibits secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Brain Research. 2000;885:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02952-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirning LD, Fox AP, Mccleskey EW, Olivera BM, Thayer SA, Miller RJ, Tsien RW. Dominant role of N-type Ca2+ channels in evoked release of norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons. Science. 1988;239:57–61. doi: 10.1126/science.2447647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai H, Aosaki T, Fukuda J. Presynaptic Ca-antagonist ω-conotoxin irreversibly blocks N-type Ca-channels in chick sensory neurons. Neuroscience Research. 1987;4:228–235. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(87)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuragi T, Su C. Purine release from vascular adrenergic nerves by high potassium and a calcium ionophore, A-23187. Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1980;215:685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, McLaren GJ, Westfall TD, Sneddon P. ATP as a co-transmitter with noradrenaline in sympathetic nerves-function and fate. Ciba Foundation Symposia. 1996;198:223–238. doi: 10.1002/9780470514900.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb HA, Wakelam MJ. Transmitter-like action of ATP on patched membranes of cultured myoblasts and myotubes. Nature. 1983;303:621–623. doi: 10.1038/303621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M, Buckingham JC, Poyer RH, Cover PO. Roles for adenosine A1-and A2 -receptors in the control of thyrotrophin and prolactin release from the anterior pituitary gland. Regulatory Peptides. 1999;79:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JR, Nowycky MC. Two types of calcium channels coexist in peptide-releasing vertebrate nerve terminals. Neuron. 1989;2:1419–1426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JR, Wang G. Perforated patch recordings of Ca2+ currents from neurohypophyseal terminals using amphotericin B. Biophysical Journal. 1993;64:A229. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JR, Wang G. Excitatory versus inhibitory modulation by ATP of neurohypophyseal terminal activity in the rat. Experimental Physiology. 2000;85:67S–75S. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.2000.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K. Relationship between presynaptic calcium current and postsynaptic potential in squid giant synapse. Biophysical Journal. 1981;33:323–352. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch A, Miah S, Burnstock G. Ultrastructural localization of ATP-gated P2X2 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. Journal of Neurocytology. 1999;28:495–504. doi: 10.1023/a:1007009222518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992a;9:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Venema VJ, Swidere KM, Lee TD, Bean BP, Adams ME. P-type calcium channels blocked by the spider toxin ω-Aga-IVA. Nature. 1992b;355:827–829. doi: 10.1038/355827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogul DT, Adams ME, Fox AP. Differential activation of adenosine receptors decreases N-type but potentiates P-type Ca2+ current in hippocampal CA3 neurons. Neuron. 1993;10:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90322-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb R, Szoke B, Palma A, Wang G, Chen X, Hopkins W, Cong R, Miller J, Tarczy-hornoch K, Loo JA, Dooley DJ, Nadasdi L, Tsien RW, Lemos JR, Miljanich G. A selective peptide antagonist of the class E calcium channel from the venom of the tarantula Hysterocrates gigas. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15353–15362. doi: 10.1021/bi981255g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowycky MC, Fox AP, Tsien RW. Three types of neuronal calcium channels with different calcium agonists sensitivity. Nature. 1985;316:440–442. doi: 10.1038/316440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Nutt JD, Murakami T, Zhu G, Kamata A, Kawata Y, Kaneko S. Adenosine receptor subtypes modulate two major functional pathways for hippocampal serotonin release. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:628–640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00628.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoli P, Betto P, Reggio R, Ricciarello G. Adenosine A2A receptor stimulation enhances striatal extracellular glutamate levels in rats. European Journal Pharmacology. 1995;287:215–217. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J, Cooper K, Gates P, Watsky M. Low access resistance perforated patch recordings using amphotericin B. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1991;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90017-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone MP, Middlemiss PJ, Gysbers JW, Andrew C, Herman MA, Reed JK, Ciccarelli R, Di Iorio P, Caciagli F. Trophic effects of purines in neurons and glial cells. Progress in Neurobiology. 1999;59:663–690. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Stehle JH, Rivkees SA. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rat A1 -adenosine receptor that is widely expressed in brain and spinal cord. Molecular Endocrinology. 1991;88:1037–1048. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-8-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. Measurements of exocytosis from single presynaptic nerve terminals reveal heterogeneous inhibition by Ca2+ channel blockers. Neuron. 1995;14:773–779. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JA. ATP related nucleotides and adenosine on neurotransmission. Life Science. 1978;22:1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather WA, Tanabe T, Zhang J-F, Mori Y, Adams ME, Tsien RW. Distinctive biophysical and pharmacological properties of class A BI calcium channel α1 subunits. Neuron. 1993;11:291–303. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90185-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Capogna M, Gaehwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of miniature excitatory synaptic currents by baclofen and adenosine in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperlagh B, Mergl Z, Juranyi Z, Vizi ES, Makara GB. Local regulation of vasopressin and oxytocin secretion by extracellular ATP in the isolated posterior lobe of the rat hypophysis. Journal of Endocrinology. 1999;160:343–350. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea A, Tomlinson WJ, Soong TW, Bourinet E, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. Localization and functional properties of a rat brain α1A calcium channel reflect similarities to neuronal Q- and P-type channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:10576–10580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirion S, Troadec JD, Nicaise G. Cytochemical localization of ecto-ATPases in rat neurohypophysis. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 1996;44:103–111. doi: 10.1177/44.2.8609366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troadec JD, Thirion S, Nicaise G, Lemos JR, Dayanithi G. ATP-evoked increases in [Ca2+]i and peptide release from rat isolated rat neurohypophysial terminals via a P2X2 purinoceptor. Journal of Physiology. 1998;511:89–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.089bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Lipscombe D, Madison DV, Bley KR, Fox AP. Multiple types of neuronal calcium channels and their selective modulation. Trends in Neurosciences. 1988;11:431–438. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TJ, Adams ME, Dunlap K. Calcium channels coupled to glutamate release identified by ω-Aga-IVA. Science. 1992;258:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.1357749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TJ, Adams ME, Dunlap K. Multiple Ca2+ channel types coexist to regulate synaptosomal neurotransmitter release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:9518–9522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemiya M, Berger AJ. Activation of adenosine A1 and A2 receptors differently modulates calcium channels and glycinergic synaptic transmission in rat brainstem. Neuron. 1994;13:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Dayanithi G, Kim S, Hom D, Nadasdi L, Kristipati R, Ramachandran J, Stuenkel E, Nordmann JJ, Newcomb R, Lemos JR. Role of Q-type Ca2+ channels in vasopressin secretion from neurohypophysial terminals of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1997;502:351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.351bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Dayanithi G, Newcomb R, Lemos JR. An R-type calcium current in rat neurohypophysial nerve terminals preferentially controls oxytocin secretion. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:9235–9241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09235.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Lemos JR. Tetrandrine blocks a slow, large-conductance, Ca2+ -activated potassium channel besides inhibiting a non-inactivating Ca2+ current in isolated nerve terminals of the rat neurohypophysis. Pflügers Archiv. 1992;421:558–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00375051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Lemos JR. Effects of funnel-web spider toxin on Ca2+ currents in neurohypophysial terminals. Brain Research. 1994;663:215–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Lemos JR. Activation of adenosine A1 receptor inhibits only N-type Ca2+ current in rat neurohypophysial terminals. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:A11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Thorn P, Lemos JR. A novel large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel and current in nerve terminals of the rat neurohypophysis. Journal of Physiology. 1992a;457:47–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM, Treistman SN, Lemos JR. Two types of high-threshold calcium currents inhibited by ω-conotoxin in nerve terminals of rat neurohypophysis. Journal of Physiology. 1992b;445:181–199. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XM, Treistman SN, Wilson A, Nordmann JJ, Lemos JR. Ca2+ channels and peptide release from neurosecretory terminals. News in Physiological Sciences. 1993;8:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TD. Role of adenine compounds in autonomic neurotransmission. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1988;38:129–168. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(88)90095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Saggau P. Adenosine inhibits evoked synaptic transmission primarily by reducing presynaptic calcium influx in area CA1 of hippocampus. Neuron. 1994;12:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, SAGGAU P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawo H, Chuhma N. Preferential inhibition of omega-conotoxin-sensitive presynaptic Ca2+ channels by adenosine autoreceptors. Nature. 1993;365:256–268. doi: 10.1038/365256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Signaling via ATP in the nervous system. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]