Abstract

Many dramatic alterations in various cellular processes during the cell cycle are known to involve ion channels. In ascidian embryos and Caenorhabditis elegans oocytes, for example, the activity of inwardly rectifying Cl− channels is enhanced during the M phase of the cell cycle, but the mechanism underlying this change remains to be established. We show here that the volume-sensitive Cl− channel, ClC-2 is regulated by the M-phase-specific cyclin-dependent kinase, p34cdc2/cyclin B. ClC-2 channels were phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B in both in vitro and cell-free phosphorylation assays. ClC-2 phosphorylation was inhibited by olomoucine and abolished by a 632Ser-to-Ala (S632A) mutation in the C-terminus, indicating that 632Ser is a target of phosphorylation by p34cdc2/cyclin B. Injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B attenuated the ClC-2 currents but not the S632A mutant channel currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. ClC-2 currents attenuated by p34cdc2/cyclin B were increased by application of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, olomoucine (100 μm), an effect that was inhibited by calyculin A (5 nm) but not by okadaic acid (5 nm). A yeast two-hybrid system revealed a direct interaction between the ClC-2 C-terminus and protein phosphatase 1. These data suggest that the ClC-2 channel is also counter-regulated by protein phosphatase 1. In addition, p34cdc2/cyclin B decreased the magnitude of ClC-2 channel activation caused by cell swelling. As the activities of both p34cdc2/cyclin B and protein phosphatase 1 vary during the cell cycle, as does cell volume, the ClC-2 channel could be regulated physiologically by these factors.

There are several lines of evidence suggesting a link between Cl− channel activity and cell proliferation and the cell cycle. In mammalian cells, studies using flow cytometry and cell proliferation assays have shown that application of various types of Cl− channel blockers affects both progression of the cell cycle and cell proliferation (Voets et al. 1995; Shen et al. 2000). In rapidly proliferating human invasive cervical carcinoma cells, volume-sensitive Cl− currents recorded using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique were markedly activated compared to normal cervical epithelial cells and cervical intraepithelial tumor cells with low-grade malignancy (Chou et al. 1995). Electrophysiological experiments have shown that at the boundary of the G1/S phase of the cell cycle, several types of Cl− currents are activated, including the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel, outwardly rectifying Cl− channel and inwardly rectifying Cl− channel (Bubien et al. 1990; Postma et al. 1996; Ullrich & Sontheimer, 1997; Shen et al. 2000). In glioma cells, activation of Cl− currents was suggested to be linked to cytoskeletal rearrangements after cell division (Ullrich & Sontheimer, 1997). Activation of inwardly rectifying Cl− currents at the M phase of the cell cycle has been reported to occur in two species, in Caenorhabditis elegans oocytes (Rutledge et al. 2001) and in ascidian embryos (Block & Moody, 1990; Coombs et al. 1992; Villaz et al. 1995). Inwardly rectifying Cl− currents in ascidian embryos are activated at the end of the M phase, increased by a specific inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase, 6-dimethylaminopurine, and they are sensitive to cell volume (Block & Moody, 1990; Coombs et al. 1992; Villaz et al. 1995), suggesting regulation by both cyclin-dependent kinase and cell volume.

Among ClCs, a large gene family with members occurring in bacteria, yeast, plants and animals, the biophysical properties of ClC-2 most closely resemble those of the Cl− channels found in ascidian embryos, and the CLH-3 (CeClC-3) channel in Caenorhabditis elegans oocytes (Thiemann et al. 1992; Malinowska et al. 1995; Furukawa et al. 1998). Interestingly, the consensus motif (Ser/Thr-Pro-x-Arg/Lys) for phosphorylation by M-phase-specific cyclin-dependent kinase p34cdc2/cyclin B is conserved in all of the mammalian ClC-2 sequences cloned to date, including those from rat, rabbit, human and mouse (Moreno & Nurse, 1990; Thiemann et al. 1992; Cid et al. 1995; Malinowska et al. 1995; Joo et al. 1999). We show here that the ClC-2 channel is phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B most likely at the 632Ser residue, and that ClC-2 channel activities in Xenopus oocytes are inhibited by injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B, suggesting that the ClC-2 channel is functionally regulated by p34cdc2/cyclin B through phosphorylation. In addition, olomoucine, a p34cdc2/cyclin B inhibitor, augmented these ClC-2 currents, while calyculin A, a protein phosphatase (PPase) inhibitor, attenuated them, suggesting a counter-regulatory role of dephosphorylation, probably by PPase 1. Moreover, injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B decreased the sensitivity of the channels to activation by changes in cell volume. These findings suggest that the ClC-2 channel is regulated not only by cell-cycle-dependent phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, but also by alterations in cell volume.

METHODS

Plasmid construction

pSPORT1/ClC-2, pSPORT1/ClC-2(S632A), pSPORT1/HA/ClC-2 and pSPORT1/HA/ClC-2(S632A)

ClC-2 cDNA obtained from rabbit heart (Furukawa et al. 1995) was subcloned into pSPORT1 (Life Technologies). As reported of other members of the ClC supergene family (Steinmeyer et al. 1991), the Cl− currents could not be expressed in Xenopus oocytes from the original putative full-length rabbit ClC-2 cDNA. Accordingly, the DNA of the Torpedo ClC-0 5′ untranslated region (83 base pairs) was synthesised and added to the first ATG of rabbit ClC-2 by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Ho et al. 1989). The mutation of 632Ser to Ala (S632A) in the consensus sequence of p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation (632Ser-633Pro-634Ala-635Arg) was made by overlap extension using PCR (Ho et al. 1989). In order to facilitate immunoprecipitation of the ClC-2 or ClC-2(S632A) protein, a haemagglutinin (HA) tag was introduced between the third residue (3Ala) and the fourth residue (4Pro) of rabbit ClC-2 by overlap extension using PCR. The sequences of these and the following plasmid constructs were verified by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method using the 377 DNA sequence system (Perkin Elmer).

pGEX-4T-1/ClC-2CT and pGEX-4T-1/ClC-2CT(S632A)

DNA fragments containing the cytosolic C-terminus of rabbit ClC-2 (from 540Gln to 886Gln) and the S632A mutation were generated by PCR using pSPORT1/ClC-2 and pSPORT1/ClC-2(S632A) as a template, respectively, and were subcloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

pAS2-1/ClC-2CT and pACT2/ClC-2CT

The PCR fragment containing the cytosolic C-terminus of rabbit ClC-2 (from 540Gln to 886Gln) described above was subcloned into the pAS2-1 or pACT2 vector (Clonetech Laboratories).

In vitro phosphorylation assay

The recombinant glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged C-terminus of ClC-2 (GST/ClC-2CT), that of ClC-2(S632A) (GST/ClC-2CT(S632A)), and the GST protein alone as control were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and purified on glutathione-sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of eluted protein was determined by the Bradford method, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BIO-RAD Laboratories), and was confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis.

Three micrograms of purified GST/ClC-2CT, GST/ClC-2CT (S632A), or GST alone was mixed with 1.2 units of human recombinant p34cdc2/cyclin B in the presence of 10 μCi of [γ-32P]-ATP (specific activity 6000 μCi pmol−1, NEN Life Science Products). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. The phosphorylation reaction was terminated by addition of SDS (final concentration 3.7 %), and the samples were subjected to filter assay or SDS-PAGE analysis. For filter phosphorylation assay, kinase assay mixtures were spotted onto P-81 phosphocellulose filter paper (Whatman), and radioactivity was counted with a liquid scintillation counter (LSC-950; Aloka).

Expression of cRNA in Xenopus oocytes and recording of expressed ClC-2 currents

Xenopus oocyte preparation and handling were carried out as described previously (Furukawa et al. 1998). Briefly, stage V-VI oocytes purchased from COPACETIC (Aomori, Japan) were injected with in vitro synthesised cRNA (2.5 ng) for ClC-2 or ClC-2(S632A), or with distilled water as a control. Oocytes were incubated for 3 days at 19 °C in modified Barth's medium containing (mm): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 15 Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.3 Ca(NO3)2, 0.4 CaCl2, 0.8 MgSO4, 90 mg l−1 theophylline, 100 μg ml−1 sodium penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulphate.

Membrane currents were recorded from oocytes with a two-electrode voltage clamp using an amplifier (TEV-200; Dagan) at a room temperature of ∼24–26 °C. Current acquisition and analysis were performed on an 80386-based microcomputer using pCLAMP software and a TL-1 analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments). Oocytes were perfused continuously with ND-96 solution containing (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 Hepes (pH 7.4 with NaOH). The oocytes were voltage-clamped at a holding potential of −30 mV, and 2 s voltage steps to −160 mV were applied every 5 s. At several time points, 2 s voltage steps were applied from −160 to +60 mV in 20 mV increments. In order to investigate the relationship between regulation of ClC-2 currents by p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation and by volume, extracellular hypotonicity was established by changing the extracellular solution from an isotonic solution containing (mm): 48 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes and 96 mannitol (pH 7.4 with NaOH; osmolarity 228 ± 11 mosmol l−1) to a mildly hypotonic solution containing (mm): 48 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes and 48 mannitol (pH 7.4 with NaOH; osmolarity 162 ± 17 mosmol l−1), or to a severely hypotonic solution containing (mm): 48 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 and 5 Hepes (pH 7.4 with NaOH; osmolarity 109 ± 13 mosmol l−1).

Phosphorylation of ClC-2 in oocyte microsome fraction

Microsome fractions of Xenopus oocytes expressing HA/ClC-2 or HA/ClC- 2(S632A) were prepared as described by Geering et al. (1987). Briefly, stage V-VI oocytes were homogenised by 20 strokes in a glass/Teflon homogeniser in buffer containing (mm): 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 MgCl2, 1 EDTA, 1 DTT, 80 sucrose, 1 phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 10 μg μl−1 each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. The samples were centrifuged twice at 100 × g (4 °C, 10 min), the supernatant (yolk-free homogenate) was ultracentrifuged at 165 000 × g (4 °C, 90 min) and the pellet was dissolved in buffer containing (in mm) 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 MgCl2, 5 NaH2PO4, 1 DTT, 1 PMSF, and 10 μg ml−1 each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. The phosphorylation reaction in oocyte microsomes was carried out with aliquots of 10 oocytes in the presence of 50 μCi [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 30 °C for 1 h. The phosphorylation reaction was stopped by addition of SDS (final concentration 3.7 %), and the reaction mixture was preabsorbed by incubation with 20 μl of protein G-sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 3 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation for 1 min at 1500 × g. The supernatant was incubated with 2 μg ml−1 of anti-HA high-affinity antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) for 3 h at 4 °C. Fifteen microlitres of protein G-sepharose was added to the immune complex, which was then further incubated for 3 h at 4 °C, and then washed five times with immunoprecipitation buffer containing (mm): 150 NaCl, 20 Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 EDTA, 50 NaF, 1 Na2VO4, 5 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 % Nonidet P-40, 1 % sodium deoxycholate, 0.1 % SDS, 1 PMSF, and 10 μg ml−1 each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. The immune complex was collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 1500 × g, and was separated on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The gel was subjected to autoradiography and the quantification of magnitude of phosphorylation was performed by an image analyser (BAS1000; Fuji Photo Film). To compare the levels of protein expression among the different experimental conditions, oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2 or HA/ClC-2(S632A), or with distilled water as control, were incubated with modified Barth's medium containing 0.6 mCi ml−1 [35S]-methionine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 72 h. Microsome fractions prepared from 10 oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2 cRNA, HA/ClC-2(S632A) cRNA, or distilled water were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel and were subjected to autoradiography and densitometric analysis using an image analyser (BAS1000; Fuji Photo Film).

Yeast two-hybrid methods

Yeast two-hybrid screening and in vivo interaction assays were performed with the MATCHMAKER Two-Hybrid System 2 (Clonetech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A rat brain cDNA library in pACT2 (Clonetech) was transformed into yeast Y190 containing the pAS2-1/ClC-2CT, and spread on the Trp−, Leu−, His− plate containing 25 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma). Transformation efficiency (∼5.0 × 106) was determined by plating an aliquot to the Trp−, Leu− plate. After 7 days, HIS3-positive colonies grown on the Trp−, Leu−, His− plate were subjected to β-galactosidase filter assay. Both HIS3- and β-galactosidase-positive colonies were rescued by transforming DNAs prepared from yeast into Escherichia coli HB101, a leu− strain, permitting specific rescue of the leu+ plasmid, pACT2. DNAs from individual Escherichia coli were retested by transforming them back into Y190 containing pAS2-1/ClC-2CT. The LacZ-positive plasmids in the retest using β-galactosidase filter assay were subjected to sequence analysis and BLAST search in the dBEST database. A quantitative β-galactosidase assay was performed using a luminescence reader (BLR-201, Aloka), as described by Campbell et al. (1995).

Reagents

Human recombinant p34cdc2/cyclin B in buffer containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.01 % Brij, and 50 % glycerol was purchased from BIOMOL Research Laboratories, and aliquots were stored at a temperature below −80 °C until use. Olomoucine (WAKO Chemical, Osaka, Japan) was prepared as a 100 mm stock solution in acetone, and calyculin A (Wako Chemical) and okadaic acid (Wako Chemical) were prepared as 10 mm stock solutions in DMSO. They were stored at a temperature below −80 °C until use, when they were dissolved in the test solution to the final concentration required.

Statistics

All measured values are presented as means ± s.d. ANOVA was used to test for the significance of differences (P ≤ 0.05).

RESULTS

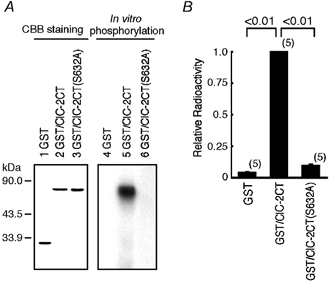

In vitro phosphorylation of the C-terminus of ClC-2

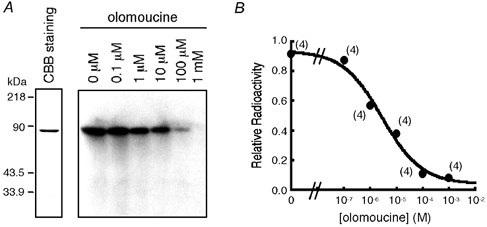

An in vitro phosphorylation assay was performed to determine whether the ClC-2 channel is phosphorylated directly by p34cdc2/cyclin B. Since a putative phosphorylation site by p34cdc2/cyclin B is present only in the C-terminus of the ClC-2 channel, the fusion protein of the ClC-2 C-terminus with GST (GST/ClC-2CT) was purified and incubated with activated p34cdc2/cyclin B in the presence of [γ-32P]-ATP. GST/ClC-2CT (lane 5 in Fig. 1A, B), but not GST protein alone (lane 4 in Fig. 1A, B), was phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B. When 632Ser in the consensus sequence of p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation in the ClC-2 sequence was replaced with Ala, in vitro phosphorylation by p34cdc2/cyclin B was completely abolished (lane 6 in Fig. 1A, B). To confirm further that the ClC-2 channel was phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B, we examined the effects of olomoucine, a membrane-permeable purine derivative that acts as a potent inhibitor of p34cdc2/cyclin B and related kinases (Vesely et al. 1994), on in vitro phosphorylation of the ClC-2 C-terminus. Olomoucine suppressed the magnitude of phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 2.7 μm (Fig. 2A, B). These data indicate clearly that the ClC-2 channel is phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B.

Figure 1. Phosphorylation of ClC-2 C-terminus in vitro.

A, lanes 1–3 show results of Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining: loaded with 0.2 μg of purified glutathione-S-transferase (GST) protein (lane 1); GST/ClC-2CT (lane 2); and GST/ClC-2CT (S632A) (lane 3). Lanes 4–6 show representative results of in vitro phosphorylation assay: loaded with reaction mixture containing GST (lane 4); GST/ClC-2CT (lane 5); and GST/ClC-2CT(S632A) (lane 6). B, quantification of in vitro phosphorylation by filter phosphorylation assay. Thirty microlitres of terminated kinase assay mixtures were spotted onto P-81 phosphocellulose paper, and radioactivity was counted with a liquid scintillation counter normalised to the value for GST/ClC-2CT. The mean radioactive value for GST/ClC-2CT was 14855 ± 1441 cpm (n = 5). The bar indicates standard deviation, and the number in parentheses attached to the bar indicates the number of experiments in this and in the following figures.

Figure 2. Effects of olomoucine on phosphorylation of the ClC-2 C-terminus in vitro.

A, the left panel shows the results of CBB staining; 0.2 μg of purified GST/ClC-2CT was loaded. The right panel shows representative results of experiments testing the effects of olomoucine on in vitro phosphorylation of GST/ClC-2CT by activated p34cdc2/cyclin B. The phosphorylation reaction was carried out in the absence (lane 1) or the presence of olomoucine at a concentration of 0.1 μm (lane 2), 1 μm (lane 3), 10 μm (lane 4), 100 μm (lane 5), and 1 mm (lane 6). B, dose-response curve for inhibition of in vitro phosphorylation by olomoucine. Incorporated radioactivity was measured by a liquid scintillation counter in a filter phosphorylation assay in four independent experiments. Values were normalised to those obtained in the absence of olomoucine.

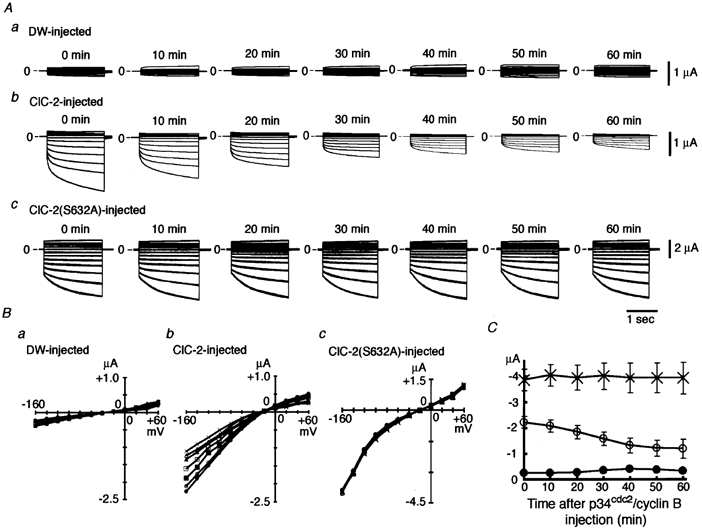

Effects of p34cdc2/cyclin B on ClC-2 currents

We investigated whether the ClC-2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes are functionally regulated by phosphorylation by p34cdc2/cyclin B. Twenty nanolitres of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B (2 units ml−1) was injected into the oocytes, and membrane currents were monitored for 60 min. The dose of p34cdc2/cyclin B injected (0.04 units oocyte−1) was chosen because it has been shown to regulate the R-eag K+ channels expressed in oocytes (Bruggemann et al. 1997). In oocytes injected with distilled water as control, the amplitude of membrane currents was not appreciably altered after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B for the entire 60 min (panel a in Fig. 3A and B); the current amplitude at −160 mV was −0.24 ± 0.07 μA and −0.32 ± 0.08 μA before and 60 min after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B, respectively (ns; n = 5). In oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA, hyperpolarisation-activated membrane currents with inward rectification and slow activation, properties typical of ClC-2 currents, were recorded. Injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B decreased the amplitude of ClC-2 currents (panel b in Fig. 3A, B); the current amplitude at −160 mV was −2.22 ± 0.23 μA and −1.19 ± 0.37 μA before and 60 min after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B, respectively (P ≤ 0.01; n = 7). The membrane currents continued to decrease for up to 40 min after p34cdc2/cyclin B injection, when the decrease in current amplitude reached a steady state (open circles in Fig. 3C). In oocytes injected with ClC-2(S632A) cRNA, membrane currents were activated by hyperpolarisation, and showed characteristics similar to those of wild-type ClC-2 currents, including inward rectification and slow, hyperpolarisation-induced activation. However, p34cdc2/ cyclin B injection did not significantly affect the amplitude of the mutant channel currents (panel c of Fig. 3A, B); the current amplitude at −160 mV was −3.87 ± 0.42 μA and −3.94 ± 0.62 μA before and 60 min after p34cdc2/cyclin B injection, respectively (ns; n = 4).

Figure 3. Effects of p34cdc2/cyclin B injection on ClC-2 currents.

A, representative experiments showing the effects of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B injected into oocytes on ClC-2 currents. Panel a, an oocyte injected with distilled water (DW); panel b, an oocyte injected with ClC-2 cRNA; and panel c, an oocyte injected with ClC-2(S632A) cRNA. Step pulses to various potentials between −160 mV and +60 mV in 20 mV increments were applied every 10 min after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u) for 60 min, and the superimposed currents at each time point are shown. B, current-voltage curves from five oocytes injected with DW (panel a), from seven oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA (panel b) and from four oocytes injected with ClC-2(S632A) cRNA (panel c) before (•) and 10 (○), 20 (▪), 30 (□), 40 (▴), 50 (▵), and 60 min (×) after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B. Bars showing standard deviation have been omitted for clarity. C, time course of changes in ClC-2 channel currents at −160 mV after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u). •, oocytes injected with distilled water; ○, oocytes injected with ClC-2 mRNA; ×, oocytes injected with ClC-2(S632A) mRNA.

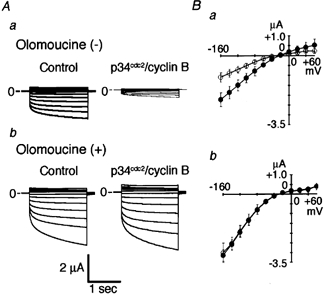

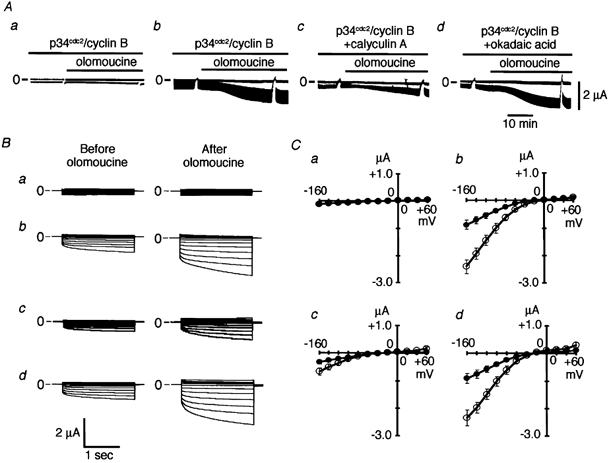

Effects of olomoucine on ClC-2 currents

To further confirm that the inhibitory effects of p34cdc2/cyclin B on ClC-2 currents are caused by phosphorylation of the channel, we examined the effects of olomoucine on p34cdc2/cyclin B-induced inhibition of ClC-2 currents. In the absence of olomoucine (100 μm), p34cdc2/cyclin B injection decreased the ClC-2 current amplitude (panel a in Fig. 4A, B); the current amplitude at −160 mV changed from −2.23 ± 0.41 μA before p34cdc2/ cyclin B injection to −1.09 ± 0.22 μA 60 min after injection (P ≤ 0.01; n = 7). After pre-incubation with olomoucine (100 μm) for 30 min, injection of p34cdc2/ cyclin B did not decrease ClC-2 current amplitude (panel b in Fig. 4A, B); the current amplitude was −3.13 ± 0.31 μA in the control state and −3.02 ± 0.48 μA after p34cdc2/cyclin B injection (ns; n = 5).

Figure 4. Effects of olomouocine on p34cdc2/cyclin B-inhibition of ClC-2 currents.

A, representative membrane currents before (left panel) and 60 min after (right panel) injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B. Panel a, an oocyte injected with ClC-2 cRNA; panel b, an oocyte injected with ClC-2 cRNA and pre-incubated with 100 μm olomoucine. Olomoucine was applied 30 min before injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B. Step pulses to various potentials between −160 mV and +60 mV in 20 mV increments were applied, and the superimposed currents are shown. B, current-voltage curves from seven oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA (panel a), from five oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA and pre-treated with olomoucine (panel b) before (•) and 60 min after (○) injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B.

Phosphorylation of full-length ClC-2 channels in the oocyte microsome fraction

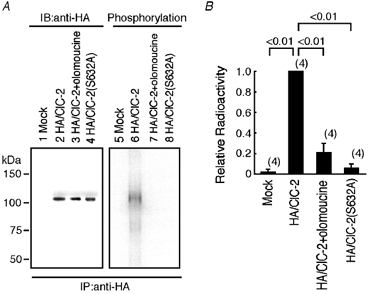

To determine whether the ClC-2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes are phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B, a cell-free phosphorylation assay of the oocyte microsome fraction was performed. Biosynthetic labelling with [35S]-methionine showed protein at a size of ∼105 kDa that was expressed to a similar extent in oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2 cRNA, injected with HA/ClC-2 cRNA and incubated with olomoucine, and injected with HA/ClC-2 (S632A; left panel in Fig. 5A). Phosphorylation assays of oocyte microsomes with activated p34cdc2/cyclin B showed a radioactive band at ∼105 kDa in oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2 cRNA (lane 6 in Fig. 5A). No radioactive band was seen in oocytes injected with mock or HA/ClC-2(S632A) (lane 5 or 8 in Fig. 5A). When a phosphorylation assay was performed in the presence of 100 μm olomoucine, radioactivity incorporation to the channel was almost completely abolished (lane 7 in Fig. 5A, B). These data suggest that the full-length ClC-2 channel expressed in the oocyte microsome fraction is phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B, most likely at the 632Ser residue.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation of full-length ClC-2 by p34cdc2/cyclin B in oocyte microsomes.

A, the left panel shows representative data demonstrating biosynthetic labelling with [35S]-methionine of oocytes injected with DW (lane 1), oocytes injected with haemagglutinin (HA)/ClC-2 cRNA (lane 2), oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2 cRNA and incubated with olomoucine for 1.5 h (lane 3), and oocytes injected with HA/ClC-2(S632A) cRNA (lane 4). The right panel shows representative data demonstrating results of phosphorylation of full-length ClC-2 in oocyte microsomes. Radioactive gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation. B, quantification of phosphorylation of oocyte microsomes by a BAS1000 image analyser. Radioactivity was normalised to the value for HA/ClC-2.

Effects of phosphatase inhibitors

In oocytes injected with activated p34cdc2/cyclin B where ClC-2 channels were phosphorylated, application of olomoucine increased membrane currents (panel b in Fig. 6A), suggesting that ClC-2 channel activities are controlled not only by phosphorylation but also by dephosphorylation by an intrinsic PPase. To confirm this, olomoucine (100 μm) was applied in the presence of a membrane-permeable phosphatase inhibitor, calyculin A or okadaic acid. Oocytes were pre-incubated with phosphatase inhibitor for 30 min prior to the application of olomoucine. The current amplitude was significantly less in the presence of calyculin A (5 nm) than in its absence both before (−0.34 ± 0.10 μA at −160 mV without calyculin A (n = 5) vs. −0.18 ± 0.08 μA with calyculin A (n = 5), P ≤ 0.01) and 30 min after (−0.91 ± 0.14 μA without calyculin A (n = 5) vs. −0.33 ± 0.13 μA with calyculin A (n = 5), P ≤ 0.01) application of olomoucine (panels c and d in Fig. 6A). The fold increase in current amplitude following olomoucine application was also significantly less in the presence of calyculin A (1.98 ± 0.31, n = 5) than in its absence (2.73 ± 0.37, n = 5; P ≤ 0.05). In contrast, incubation with okadaic acid (5 nm) did not affect the amplitude of ClC-2 currents before or after the application of olomoucine (panel d in Fig. 6A–C). These data indicate that the ClC-2 channel is regulated by an intrinsic PPase that is sensitive to 5 nm calyculin A but resistant to 5 nm okadaic acid.

Figure 6. Effects of protein phosphatase (PPase) inhibitors.

A, representative continuous recordings of membrane currents showing the effects of extracellularly applied 100 μm olomoucine. Activated p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u) was injected 30 min before olomoucine application in a DW-injected oocyte (panel a), in a ClC-2- injected oocyte (panel b), in a ClC-2-injected oocyte pre-treated with calyculin A (5 nm; panel c) and in a ClC-2-injected oocyte pre-treated with okadaic acid (5 nm; panel d); 2 s step pulses to −160 mV from a holding potential of −30 mV were applied every 5 s. Before and 30 min after application of olomoucine, step pulses at various potentials between −160 mV and +60 mV in 20 mV increments were applied. The upper lines show the current level at a holding potential of −30 mV and lower lines at a step pulse to −160 mV. Upward represents the outward current and downward represents the inward current. B, representative superimposed current traces before (left panel) and 30 min after olomoucine application (right panel) are shown. Panel a shows data from a DW-injected oocyte, panel b from a ClC-2-injected oocyte, panel c from a ClC-2-injected oocyte pre-treated with calyculin A (5 nm) and panel d from a ClC-2-injected oocyte pre-treated with okadaic acid (5 nm). C, the current-voltage curves from five oocytes injected with DW (panel a), from five oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA (panel b), from five oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA and pre-treated with calyculin A (5 nm; panel c) and from five oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA and pre-treated with okadaic acid (5 nm; panel d) before (•) and 30 min after (○) olomoucine application.

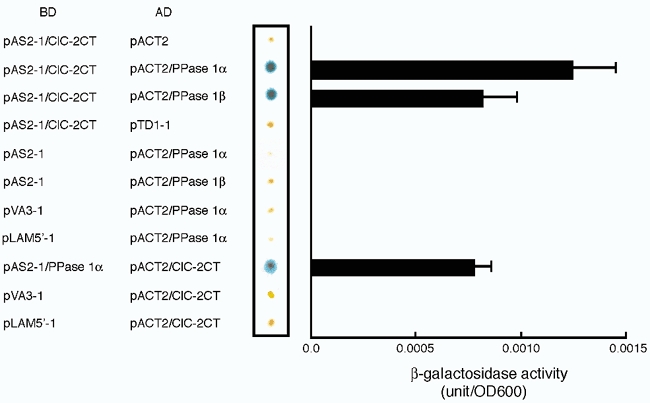

Interaction of ClC-2 and PPase 1 in yeast two-hybrid assay

Because the C-terminus of ClC-2 is thought to be the key region in regulation by p34cdc2/cyclin B, we searched for proteins that interact with this region using the yeast two-hybrid system. Screening a rat brain cDNA library with the C-terminus of ClC-2 as bait yielded 13 positive clones. Analysis of cDNA sequencing and BLAST search revealed that of the 13 positive clones, three clones corresponded to the catalytic subunit of the PPase 1 α-isoform, and two clones corresponded to the catalytic subunit of the PPase 1 β-isoform. Figure 7 shows the results of qualitative and quantitative β-galactosidase assay. The C-terminus of ClC-2 in the pAS2-1 vector (pAS2-1/ClC-2CT) interacted with the catalytic subunit of the PPase 1 α-isoform (pAS2-1/PPase 1α) or the catalytic subunit of the PPase 1 β-isoform (pAS2-1/PPase 1β) in the pACT2 vector but not with the pACT2 vector itself or with a totally unrelated cDNA in the pACT2 vector, SV40 large T-antigen (pTD1-1). Conversely, the C-terminus of ClC-2 in the pACT2 vector (pACT2/ClC2-CT) interacted with the catalytic subunit of the PPase 1 α-isoform in the pAS2-1 vector (pAS2-1/PPase 1α), but not with the pAS2-1 vector itself or totally unrelated cDNA murine p53 (pVA3-1) or human Lamin C (pLAM5′-1) in the pAS2-1 vector.

Figure 7. Interaction between ClC-2CT and PPase 1 shown by yeast two-hybrid assay.

The combinations of transformed plasmids for the GAL4-binding domain (BD)-fusion protein and the GAL4-activation domain (AD)-fusion protein are listed on the left. Results of representative qualitative β-galactosidase filter lift assay (middle panel, out of three experiments) and quantitative β-galactosidase assay (right panel, n = 4) for each combination of plasmid transformation are shown. pVA3-1, murine p53 in the pAS2-1 vector; pLAM5′-1, human Lamin C in the pAS2-1 vector; pTD1-1, SV40 large T antigen in the pACT2 vector.

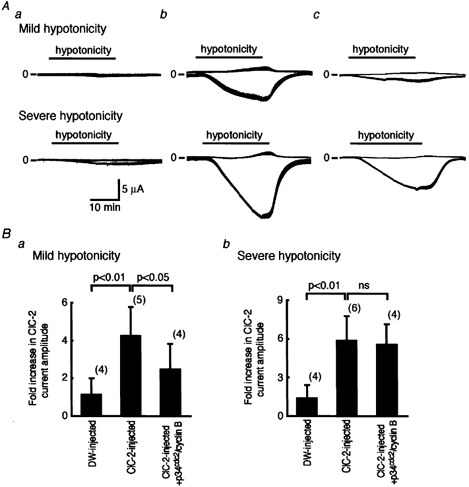

ClC-2 channel regulation by volume and p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation

Since the ClC-2 channel has been shown to be a swelling-activated Cl− channel (Grunder et al. 1992; Furukawa et al. 1998) and the cell volume increases about two-fold prior to cell division, we compared the effects on ClC-2 channel activity of changes in volume of the oocytes with and without injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B. Superfusion with a hypotonic solution significantly enhanced the membrane currents in oocytes injected with ClC-2 cRNA (Fig. 8Ab), but not those in controls injected with distilled water (Fig. 8Aa). In ClC-2-injected oocytes superfused with a mildly hypotonic solution 1 h after injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u) when the inhibitory effects of p34cdc2/cyclin B had reached a steady state (see Fig. 3C), the increment in current amplitude was significantly less than in oocytes without p34cdc2/cyclin B injection (Fig. 8A, upper panels). In ClC-2-injected oocytes without injection of p34cdc2/cyclin B, ClC-2 current amplitude at −160 mV was −2.12 ± 0.71 μA in the isotonic solution and −8.96 ± 3.11 μA 30 min after exposure to a mild hypotonic solution (n = 5), while in those injected with p34cdc2/ cyclin B (0.04 u), the corresponding values were −1.66 ± 0.88 μA and −4.12 ± 2.11 μA, respectively (n = 4); the fold increase in current amplitude was 2.48 ± 1.35 (n = 4) and 4.26 ± 1.52 (n = 5), respectively (P ≤ 0.05; Fig. 8B–a). The effect of a severe hypotonic solution, on the other hand, was similar in those with and without p34cdc2/cyclin B injection (Fig. 8A, lower panels); ClC-2 current amplitude at −160 mV before and 30 min after severe hypotonic challenge was −2.37 ± 0.88 μA and −14.42 ± 3.81 μA, respectively (n = 6), in p34cdc2/cyclin B-uninjected cells, while the corresponding values were −1.32 ± 0.84 μA and −7.55 ± 2.15 μA, respectively (n = 4), in p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u)-injected cells, and the fold increase was not significantly different (5.54 ± 1.62 (n = 4) vs. 5.89 ± 1.88 (n = 6); Fig. 8B–b).

Figure 8. Relationship between regulation of ClC-2 currents by volume and p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation.

A, representative continuous recordings of ClC-2 currents in a DW-injected oocyte (panel a), in a ClC-2-injected oocyte (panel b), and in a ClC-2-injected oocyte also injected with p34cdc2/cyclin B (0.04 u). The extracellular solution was changed from an isotonic solution to a mild hypotonic solution (upper panel) or to a severe hypotonic solution (lower panel) for 30 min. Step pulses from a holding potential of −30 mV to −160 mV were applied every 5 s. The upper lines show the current level at a holding potential of −30 mV and the lower lines at step pulses to −160 mV. Upward represents the outward current and downward represents the inward current. B, the fold increase in ClC-2 current amplitude at −160 mV, 30 min after superfusion with hypotonic solution relative to that in the isotonic solution with mild hypotonic solution (panel a) and with a severe hypotonic solution (panel b).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the results of the in vitro phosphorylation assay show that the C-terminus of ClC-2 is phosphorylated by activated p34cdc2/cyclin B, and that this is inhibited by olomoucine in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 value (2.7 μm) was within the range of the reported IC50 (7 μm) for inhibition of p34cdc2/cyclin B (Campbell et al. 1995). We also demonstrate that the full-length ClC-2 channels in the oocyte microsome fraction were phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B, and that this was inhibited by olomoucine. Since the substitution of 632Ser to Ala in the consensus motif of p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation completely abolished phosphorylation both in vitro and in oocyte microsomes, 632Ser in the ClC-2 sequence is the residue most likely to be phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B. Injection of activated p34cdc2/cyclin B inhibited ClC-2 channel currents heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes, but did not inhibit S632A ClC-2 mutant channel currents. Olomoucine attenuated the action of p34cdc2/cyclin B in suppressing ClC-2 channel currents. These two findings suggest that phosphorylation, most likely at 632Ser, by p34cdc2/cyclin B functionally regulates ClC-2 channel activity. The time course of current suppression was relatively slow, requiring ∼40 min to reach a steady state. Although the cause is not known, a similar time course was reported in p34cdc2/cyclin B-dependent suppression of R-eag K+ channel currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Bruggemann et al. 1997).

Since olomoucine increased currents through ClC-2 channels that had been phosphorylated by p34cdc2/cyclin B, ClC-2 channel activities might also be modulated by dephosphorylation by an intrinsic PPase in oocytes. The effect of olomoucine was inhibited by 5 nm calyculin A but not by 5 nm okadaic acid. Each of these reagents is known to inhibit PPase 1 and PPase 2A at a different range of concentrations: the IC50 of calyculin A for PPase 1 is 2 nm and that for PPase 2A is 0.5–1.0 nm (Ishihara et al. 1989); those of okadaic acid for PPase 1 and PPase 2A are 10–15 nm and 0.1 nm, respectively (Haystead et al. 1989). Thus, calyculin A at 5 nm should inhibit both PPase 1 and PPase 2A, while 5 nm okadaic acid should inhibit PPase 2A but not PPase 1. The PPase responsible for dephosphorylation of the ClC-2 channel, therefore, is likely to be PPase 1 rather than PPase 2A. Since inwardly rectifying ClC-2-like Cl− currents in ascidian embryos appear at the end of M phase, when cell cycle-dependent protein kinase activity is low, dephosphorylation is thought to be essential in activation of the channel (Villaz et al. 1995). In human intestinal T84 cells, hyperpolarisation-activated Cl− currents with biophysical and pharmacological properties resembling those of the ClC-2 channel have been described (Fritsch & Edelman, 1996, 1997). A low concentration of calyculin A but not of okadaic acid was found to suppress these currents when they were activated by extracellular hypotonic solution in T84 cells (Fritsch & Edelman, 1997), as in the ClC-2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. In addition, yeast two-hybrid experiments revealed a direct interaction between the cytosolic C-terminus of ClC-2 and PPase 1. ClC-2 channel function, therefore, is probably regulated by dephosphorylation of the ClC-2 channel by PPase 1 through a direct protein-protein interaction, as has been suggested of the class C L-type Ca2+ channel and PPase 2A (Davare et al. 2001).

The ClC-2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes are activated by cell swelling induced by exposure to extracellular hypotonic solutions (Grunder et al. 1992; Furukawa et al. 1998). In the present study, ClC-2 currents were augmented by cell swelling, even in oocytes injected with p34cdc2/cyclin B. Mild hypotonicity augmented ClC-2 current amplitude less in oocytes injected with p34cdc2/cyclin B than in non-injected oocytes, while severe hypotonicity augmented it both in p34cdc2/cyclin B-injected and non-injected oocytes. Thus, phosphorylation by p34cdc2/cyclin B affects the sensitivity of ClC-2 channels to oocyte swelling. This is consistent with findings in the ClC-2-like channels found in ascidian embryos (Villaz et al. 1995) as well as in Caenorhabditis elegans, in which the minimum cell volume required to activate CLH-3 (CeClC-3), a homolog or an ortholog of ClC-2, varies according to the stage of oocyte maturation.

In ClC-2-deficient mice, it was reported that the seminiferous tubules of the testis did not develop lumina and the germ cells failed to complete meiosis, which led to male infertility (Bosl et al. 2001). It was suggested that the failure of germ cell meiosis was due to a defect in transepithelial transport by Sertoli cells, which resulted in abnormal ionic homeostasis, rather than a defect in the control of the cell cycle in the germ cell itself. On the other hand, in Caenorhabditis elegans, the cell-cycle-dependent regulation of CLH-3 (CeClC-3) and its physiological role have been clearly shown (Rutledge et al. 2001). CLH-3 currents recorded using the whole-cell mode patch-clamp technique were larger in oocytes with nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) undergoing meiotic maturation than in those with an intact nuclear envelope. The disruption of CLH-3 expression by RNA interference did not affect the timing of NEBD, but did induce premature sheath cell ovulatory contraction, suggesting that CLH-3 activation in oocytes does not play an essential role in cell-cycle progression, but functions rather as a negative regulator of sheath cell ovulatory contraction. Since CLH-3 is not expressed in sheath cells, signals by cell-cycle-dependent CLH-3 activation in oocytes are likely to be transmitted electrically to the sheath cells through gap junctions. Although the physiological role of ClC-2 channel regulation by p34cdc2/cyclin B and PPase 1 in mammalian cells remains unclear, coordinated regulation with that by volume changes may play a physiological role in cell-cycle-dependent signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr K. Yamada for helpful discussion, K. Kato for helping with oocyte injection and S. Kuribayashi for helping with the yeast two-hybrid assay. This study was supported in part by Scientific Research Grants and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas ‘ABC Proteins’ (Grant 10217201) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- Block ML, Moody WJ. A voltage-dependent chloride current linked to the cell cycle in ascidian embryos. Science. 1990;247:1090–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.2309122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosl MR, Stein V, Hubner C, Zdebik AA, Jordt S -E, Mukhopadhyay AK, Davidoff MS, Holstein A -F, Jentsch TJ. Male germ cells and photoreceptors, both dependent on close cell-cell interactions, degenerate upon ClC-2 Cl− channel disruption. EMBO Journal. 2001;20:1289–1299. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggemann A, Stuhmer W, Pardo LA. Mitosis-promoting factor-mediated suppression of a cloned delayed rectifier potassium channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:537–542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubien JK, Kork KL, Rado TA, Frizzell RA. Cell cycle dependence of chloride permeability in normal and cystic fibrosis lymphocytes. Science. 1990;248:1416–1419. doi: 10.1126/science.2162561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS, Buder A, Deuschle U. Interactions between the amino-terminal domain of p56lck and cytoplasmic domains of CD4 and CD8 alpha in yeast. European Journal of Immunology. 1995;25:2408–2412. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CY, Shen MR, Wu SN. Volume-sensitive chloride channels associated with human cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 1995;55:6077–6083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid LP, Montrose Rafizadeh C, Smith DI, Guggino WB, Cutting GR. Cloning of a putative human voltage-gated chloride channel (ClC-2) cDNA widely expressed in human tissues. Human Molecular Genetics. 1995;4:407–413. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs JL, Villaz M, Moody WJ. Changes in voltage-dependent ion currents during meiosis and first mitosis in eggs of an ascidian. Developmental Biology. 1992;153:272–282. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90112-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, Horne MC, Hoshi T, Hell JW. A β2-adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel CaV1. 2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch J, Edelman A. Modulation of the hyperpolarization-activated Cl− current in human intestinal T84 epithelial cells by phosphorylation. Journal of Physiology. 1996;490:115–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch J, Edelman A. Osmosensitivity of the hyperpolarization-activated chloride current in human intestinal T84 cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C778–786. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Horikawa S, Terai T, Ogura T, Katayama Y, Hiraoka M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a truncated form (ClC-2β) of ClC-2α (ClC-2G) in rabbit heart. FEBS Letters. 1995;375:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01178-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Ogura T, Katayama Y, Hiraoka M. Characteristics of rabbit ClC-2 current expressed in Xenopus oocytes and its contribution to volume regulation. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C500–512. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geering K, Kraehenbuhl JP, Rossier BC. Maturation of the catalytic alpha-subunit of Na,K-ATPase during intracellular transport. Journal of Cellular Biology. 1987;105:2613–2619. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunder S, Thiemann A, Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. Regions involved in the opening of ClC-2 chloride channel by voltage and cell volume. Nature. 1992;360:759–762. doi: 10.1038/360759a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haystead TA, Sim AT, Carling D, Honnor RC, Tsukitani Y, Cohen P, Hardie DG. Effects of the tumour promoter okadaic acid on intracellular protein phosphorylation and metabolism. Nature. 1989;337:78–81. doi: 10.1038/337078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Karaki H, Ozaki H, Kato Y, Fusetani N, Watabe S, Hashimoto K, Uemura D, Hartshorne DJ. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1989;159:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo NS, Clarke LL, Han BH, Forte LR, Kim HD. Cloning of ClC-2 chloride channel from murine duodenum and its presence in CFTR knockout mice. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1446:431–437. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska DH, Kupert EY, Bahinski A, Sherry AM, Cuppoletti J. Cloning, functional expression, and characterization of a PKA-activated gastric Cl− channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:C191–200. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.1.C191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Nurse P. Substrates for p34cdc2: in vivo veritas? Cell. 1990;61:549–551. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90463-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma FR, Jalink K, Hengeveld T, Bot AG, Alblas J, de Jonge HR, Moolenaar WH. Serum-induced membrane depolarization in quiescent fibroblasts: activation of a chloride conductance through the G protein-coupled LPA receptor. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:63–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge E, Bianchi L, Christensen M, Boehmer C, Morrison R, Broslat A, Beld AM, George AL, Jr, Greenstein D, Strange K. CLH-3, ClC-2-anion channel ortholog activated during meiotic maturation in C. elegans oocytes. Current Biology. 2001;11:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M-R, Droogman SG, Eggermont J, Voets T, Ellory JC, Nilius B. Differential expression of volume-regulated anion channels during cell cycle progression of human cervical cancer cells. Journal of Physiology. 2000;529:385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmeyer K, Ortland C, Jentsch TJ. Primary structure and functional expression of a developmentally regulated skeletal muscle chloride channel. Nature. 1991;354:301–304. doi: 10.1038/354301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann A, Grunder S, Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. A chloride channel widely expressed in epithelial and non-epithelial cells. Nature. 1992;356:57–60. doi: 10.1038/356057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich N, Sontheimer H. Cell cycle-dependent expression of a glioma-specific chloride current: proposed link to cytoskeletal changes. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C1290–1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesely J, Havlicek L, Strnad M, Blow JJ, Donella Deana A, Pinna L, Letham DS, Kato J, Detivaud L, Leclerc S. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by purine analogues. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1994;224:771–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaz M, Cinniger JC, Moody WJ. A voltage-gated chloride channel in ascidian embryos modulated by both the cell cycle clock and cell volume. Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:689–699. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Szucs G, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Blockers of volume-activated Cl− currents inhibit endothelial cell proliferation. Pflügers Archiv. 1995;431:132–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00374387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]