Abstract

Intracellular H+ mobility was estimated in the rabbit isolated ventricular myocyte by diffusing HCl into the cell from a patch pipette, while imaging pHi confocally using intracellular ratiometric SNARF fluorescence. The delay for acid diffusion between two downstream regions ≈40 μm apart was reduced from ≈25 s to ≈6 s by replacing Hepes buffer in the extracellular superfusate with a 5 % CO2/HCO3− buffer system (at constant pHo of 7.40). Thus CO2/HCO3− (carbonic) buffer facilitates apparent mobility. The delay with carbonic buffer was increased again by adding acetazolamide (ATZ), a membrane permeant carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitor. Thus facilitation of apparent mobility by CO2/HCO3− relies on the activity of intracellular CA. By using a mathematical model of diffusion, the apparent intracellular H+ equivalent diffusion coefficient () in CO2/HCO3−-buffered conditions was estimated to be 21.9 × 10−7 cm2 s−1, 5.8 times faster than in the absence of carbonic buffer. Facilitation of mobility is discussed in terms of an intracellular carbonic buffer shuttle, catalysed by intracellular CA. Turnover of this shuttle is postulated to be faster than that of the intrinsic buffer shuttle. By regulating the carbonic shuttle, CA regulates effective mobility which, in turn, regulates the spatiotemporal uniformity of pHi. This is postulated to be a major function of CA in heart.

The accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) reported that, in rabbit ventricular myocytes, the apparent diffusion coefficient for the intracellular H+ ion () or its ionic equivalent such as OH− is ≈300-fold lower than in dilute, unbuffered solution, and about 55-fold lower than that for simple inorganic ions like Na+ or K+. This value of represents the intrinsic mobility of H+ equivalents in the cytoplasmic compartment, determined in situ in the absence of an intracellular CO2/HCO3− buffer system. The consequence of a low is that a spatially localized intracellular acidosis spreads slowly as a diffusive wave, taking more than 1 min to pass down the length of a 100 μm cardiac myocyte. Such slow kinetics of acid movement mean that acid/base transport at the sarcolemma may be expected to result in a spatial non-uniformity of pHi, with unpredictable consequences for cardiac function.

The movement of cytoplasmic acid is likely to be limited by the mobility of intracellular buffers, as these bind almost all intracellular acid (Junge & McLaughlin, 1987; Irving et al. 1990). In cardiomyocytes, intrinsic mobility will therefore be defined by intracellular mobile buffers such as small peptides containing histidine (e.g. derivatives of carnosine, anserine and homocarnosine) and by intracellular taurine and Pi (see Table 1 of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). If this model of equivalent mobility is correct, adding a more mobile buffer to the intracellular compartment should increase intrinsic mobility.

CO2/HCO3− is a physiological buffer system that would be expected to have relatively high effective mobility, as both CO2 and HCO3− are low molecular weight solutes that lack specific intracellular binding proteins, at least in the heart, and which are non-charged or have low electronic valency. The ability of this buffer system to facilitate mobility may, however, be limited by the speed of the chemical interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−, as the uncatalysed hydration of CO2 is known to be slow (Swenson & Maren, 1978), taking at least 30 s to reach equilibrium in unbuffered solution, and considerably longer (≈5 min) in the presence of intrinsic, intracellular buffers (Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998). Since reversible CO2 hydration is catalysed by carbonic anhydrase (CA) and since CA activity is expressed (Bruns & Gros, 1992) and functionally active in cardiomyocytes (Lagadic-Gossmann et al. 1992; Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998), there may be an important role for this enzyme in regulating intracellular H+ ion mobility and hence the spatial distribution of intracellular pH. Evidence for the regulation of mobility by intracellular CA has emerged recently from confocal imaging of spatial pHi non-uniformities induced by membrane acid transport in epithelial duodenal enterocytes (Stewart et al. 2000).

In the present work we have used the method of diffusing acid locally into a ventricular myocyte through a patch pipette in order to explore the effect of CO2/HCO3− buffer and CA activity on the longitudinal movement of equivalents. Intracellular pH was monitored using AM-loaded SNARF, and apparent mobility was assessed by imaging intracellular pH (pHi) using laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Preliminary reports of these experiments have been published previously (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2000a, b).

METHODS

Details are given in full in Methods of the accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Briefly, ventricular myocytes were isolated enzymatically from hearts of New Zealand White rabbits (2-3 kg). The animals were anaesthetized with an intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbitone (50 mg kg−1) and 0.5 ml heparin to prevent blood clotting, in accordance with national guidelines. Intracellular pH was measured ratiometrically in single cells during pipette acid loading using the fluorescent pH indicator SNARF-1 (loaded into the cell in its acetoxymethyl ester (AM) form) and a confocal microscope. Myocytes were held in the glass-bottomed cell chamber and continuously superfused at 36 ± 0.3 °C with a CO2/HCO3−-buffered solution containing (mm): NaCl 126.0, KCl 4.4, MgC12 1.0, dextrose 11.0, CaC12 1.1 and 18.5 Na HCO3−. It was continuously gassed with 5.0 % CO2-95.0 % O2 to give a pH of 7.4. The barometric pressure in the laboratory was ≈640 mmHg, yielding a PCO2 of ≈30 mmHg. This solution also contained 1 mm amiloride (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) to inhibit Na+-H+ exchange. In some experiments 10 μM of the CA inhibitor acetazolamide (ATZ) (Sigma) was also included. This concentration of ATZ has been shown to inhibit maximally the influence of CA on the rate of intracellular CO2 hydration in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes bathed in CO2/HCO3−-buffered solution (Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998). The composition of the pipette filling solution was the same as that described in the preceding paper (mm: KCl 140, dextrose 5.5, MgCl2 0.5, and HCl 1.0, pH = 3). It was gas equilibrated with 5.0 % CO2-95.0 % O2 immediately before use and held in a glass syringe at 37 °C before back-filling the pipettes.

Determination of intracellular buffer capacity

Total intracellular buffer capacity (βtot) is equal to the sum of intrinsic buffer capacity (βi) and CO2-dependent buffer capacity (βCO2). As noted in the accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) we used the following empirical equation (Leem et al. 1999) to compute βi:

| (1) |

where A and B are two buffer populations of concentration 84.22 and 29.38 mM, respectively, and -log of dissociation constant

(pK) values (pKa and pKb) of 6.03 and 7.57, respectively. βCO2 was calculated as:

| (2) |

where [HCO3−]i and [HCO3−]o are the intra- and extracellular bicarbonate concentrations, respectively.

This assumes that the CO2 solubility coefficient and the pKa of CO2/HCO3− are the same inside and outside the cell. It also assumes that the CO2/HCO3− buffer system is at equilibrium.

Summarized results are presented as means ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test for unpaired data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of CO2/HCO3− buffer on pHi during intracellular acid loading by pipette

Acid loading in proximal and distal regions

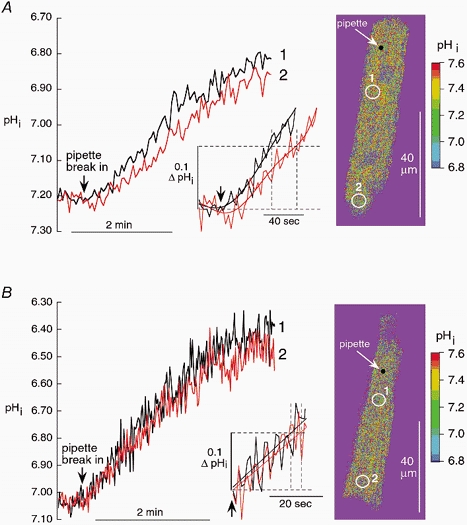

Figure 1 compares the time course of acid loading in two confocal regions of interest (ROIs) defined within a myocyte superfused with either Hepes-buffered Tyrode solution (A) or CO2/HCO3−-buffered Tyrode solution (B), both at pHo 7.4. In each case, an acid-filled (pH 3.0) patch pipette was attached to one end (the proximal end) of the cell. In the case of the CO2/HCO3−-buffered cell, care was taken to ensure that the pipette filling solution was also saturated with 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. Ratiometric confocal images of pHi were obtained at roughly 2 s intervals. Specimen ratiometric images are illustrated to the right of Fig. 1A and B. Throughout the present work, the centres of the two ROIs were standardized as close as possible to 16 μm (proximal ROI) and 58 μm (distal ROI) downstream from the pipette, as indicated in the images.

Figure 1. Longitudinal diffusion delay is reduced in CO2/HCO3− buffer.

Acid is diffused into a rabbit myocyte from a patch pipette. Standardized longitudinal positions of pipette and regions of interest (ROIs) are shown in a confocal, calibrated ratiometric SNARF image (right). Distance from pipette to centre of ROI 1: 15 μm; ROI 1 to ROI 2: 40 μm. Main graph shows the time course of acid loading averaged within the ROIs. Inset shows the initial period after break-in at higher amplification. To help identify the arrival time of pHi at the 0.1 threshold, polynomial fits (5th order) were applied to each curve over the first 2.3 min. Dashed lines indicate time delay between the two ROIs estimated at a threshold fall of pHi (ΔpHi) of −0.1 units. A, Hepes-buffered superfusate. B, 5 % CO2/HCO3−-buffered superfusate.

In Hepes buffer (Fig. 1A), the cell acidified following break-in with the pipette but, at the distal ROI, onset of acidification, measured at a threshold acidification of −0.1 ΔpHi, was delayed by ≈25 s (see Fig. 1A, inset) and proceeded more slowly, as reported in the accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). In contrast, in CO2/ HCO3− buffer (Fig. 1b), proximal and distal acidification rates were very similar and the distal delay for onset of acidification was reduced considerably to a few seconds (see Fig. 1B, inset).

Diffusion delay

To measure this, we used a protocol developed in the accompanying paper, where arrival of the diffusing acid within an ROI was measured at a threshold rise of 20 nm [H+]i (this is, for example, equivalent to a 0.1 unit fall in pHi from a starting pHi of 7.10). The pHi traces were therefore converted to changes in [H+]i (for an illustration of this process see Fig. 8 of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). The procedure was adopted because inter-ROI time delay at a 20 nm threshold was used later for estimating . The time delay was ≈4-fold lower when using CO2/HCO3−-buffered superfusates. Mean delay in Hepes was 25.1 ± 5.1 s (n = 10; data from Fig. 6 of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) whereas it was 5.93 ± 2.96 s (n = 7) in CO2/HCO3−.

Longitudinal spatial profiles of pHi

The reduced delay for intracellular H+ equivalent movement in the presence of CO2/HCO3− buffer implies that the longitudinal spatial profile for acid loading should be more uniform throughout the loading period. The accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) showed that, when using Hepes superfusates, a longitudinal pHi gradient of 0.2-0.4 units was evident during acid loading. In the present work, when using CO2/HCO3−-buffered superfusates, no clear longitudinal gradient of pHi could be resolved within ROIs drawn down the length of the cell (n = 7; not shown). A gradient, however, must have existed as distal acid loading lagged behind proximal loading by several seconds. The amplitude of longitudinal pHi gradients under these conditions can be appreciated from the inset in Fig. 1B where linear fits to the proximal and distal acid loading traces suggest a spatial pH difference of 0.02-0.03 pH units. Resolving these small differences more clearly will require significant improvements in the signal-to-noise ratio of the pHi traces. In conclusion, spatial uniformity of pHi is enhanced greatly by CO2/HCO3−, consistent with an increase in the mobility of intracellular acid equivalents.

Effect of acetazolamide on pHi during acid loading by pipette

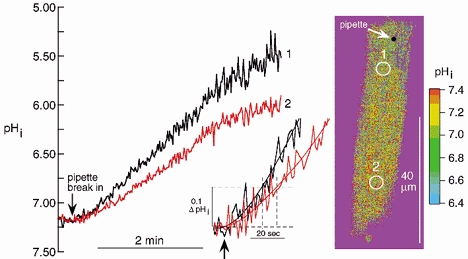

The experiment shown in Fig. 2 illustrates the effect of inhibiting CA with 10 μM of the membrane permeant CA inhibitor acetazolamide (ATZ). This agent has been shown to inhibit fully intracellular CA activity in ventricular cardiomyocytes (Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998). Despite the fact that CO2/HCO3− buffer was present, the distal ROI acidified more slowly than the proximal ROI and, as shown in the inset, there was a delay of several seconds between the proximal and distal regions. In eight cells superfused with CO2/HCO3−, the average inter-ROI time delay in the presence of ATZ (measured at a threshold rise of 20 nm [H+]i) was 15.53 ± 2.65 s (n = 8), 2.6 times longer than in the absence of the drug. The result indicates that while CO2/HCO3− buffer can facilitate intracellular H+ equivalent movement, efficient facilitation requires the activity of intracellular CA.

Figure 2. ATZ increases intracellular diffusion delay.

Time course of acid loading averaged within ROIs 1 and 2 plotted in main graph. Calibrated ratiometric image shows standardized longitudinal positions of pipette and the two ROIs (see legend to Fig. 1 for quantitative spacing). Inset shows the initial period after break-in at higher amplification. Continuous lines fitted to traces by computer (8th order polynomial). Dashed lines indicate diffusion delay (at a −0.1 ΔpHi threshold level).

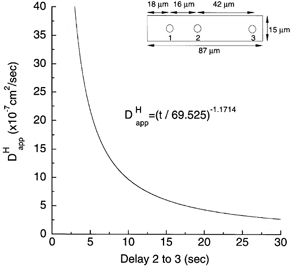

Apparent diffusion coefficient in CO2/HCO3−

In the accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) we showed that, for a given longitudinal separation of ROIs downstream from the pipette, the time delay for acid movement between the ROIs provided a useful assessment of (see Fig. 10B of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). In that paper, a mathematical model was developed to describe the spatiotemporal properties of [H+]i accumulation in response to continuous diffusion of H+ from the pipette. It was shown that, for a specified set of cell parameters (given at the top of Fig. 3 of the present paper), inter-ROI time delay (t) could be described empirically as:

which, on rearrangement gives:

| (3) |

where time for first appearance of diffusing acid within an ROI was taken at a threshold rise (Δ[H+]i) of 20 nm. Equation (3) gave a good fit to experimental data derived in the absence of CO2/HCO3− (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). The function is essentially hyperbolic, and has been plotted as the continuous line in Fig. 3. For convenience, we have used this function to estimate from measurements of time delay in the present experiments, while matching our experimental cell parameters as closely as possible to those specified in the mathematical model (see Fig. 3 legend for details).

Figure 3. Relationship between inter-ROI time delay and apparent mobility.

Results of the mathematical model of diffusion described in previous paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Graph drawn according to the equation: = (delay/69.525)−1.1714. Delay was measured in a model cell (at a 20 nm threshold rise of [H+]i) between points 2 and 3 downstream from a pipette sited at point 1 (see inset for dimensions and point positions of model cell). The relationship is shown for time delays of 2-14 s. The equation was derived empirically from time courses predicted by the model for the rise of acid at sites 2 and 3 (for further details see Fig. 11 of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002).

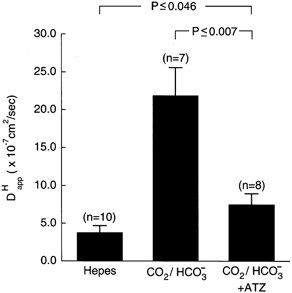

Values for , obtained by substituting time delay into eqn (3), were averaged and have been plotted in the histogram shown in Fig. 4. Also plotted is the mean value for estimated previously in Hepes (taken from Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). The estimated in CO2/ HCO3−-buffered conditions was 21.89 × 10−7 cm2 s−1, which is nearly 6-fold higher than that determined in Hepes. This higher value is reduced in the presence of ATZ to 7.53 × 10−7 cm2 s−1, a value approaching that estimated in Hepes.

Figure 4. mobility coefficient is increased by 5 % CO2/HCO3− but this increase is attenuated by ATZ.

The number of cells is shown in parentheses. ATZ dose =10 μM. The results of Student's unpaired t test are indicated above the bars.

DISCUSSION

Intracellular CO2/HCO3− facilitates ion movement

Facilitation is regulated by carbonic anhydrase

The effective diffusion coefficient in the mammalian ventricular myocyte is enhanced nearly 6-fold in the presence of a CO2/HCO3− buffer system. In the absence of CO2/HCO3−, net diffusive flux of intrinsic buffer will be greater than H+ flux (because intrinsic, mobile buffer concentration >> [H+]i) and will therefore govern overall H+ ion movement (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Adding sufficient concentration of a more mobile, extrinsic buffer, such as CO2/HCO3−, will short circuit the intrinsic buffer shuttle by adding a faster shuttle, resulting in a faster apparent mobility of .

Previous models of intracellular proton mobility (Junge & McLaughlin, 1987; Irving et al. 1990) did not consider the potential importance of CO2/HCO3− buffer (carbonic buffer). The present work shows that the increase in upon addition of carbonic buffer dramatically reduces the spatial non-uniformity of pHi caused by local acid influx. In addition, inhibiting intracellular CA activity removes most of this effect. This is similar to a recent report by Stewart et al., (2000) where addition of ATZ to an isolated duodenal enterocyte removed the ability of carbonic buffer to attenuate spatial pHi gradients elicited by membrane H+ transport. This suggests that regulation of mobility by CA may be a fundamental role of the enzyme.

Regulation of H+ mobility by CA need not be restricted to the intracellular compartment. Extracellular CA isoforms that are membrane bound (Dodgson, 1991) are expressed not only in heart (De Hemptinne et al. 1987) but also in various other tissues (Geers & Gros, 2000; Tong et al. 2000a). These extracellular sites may therefore help to reduce the possibility of local pHo non-uniformity. Such a role would be particularly important in unstirred interstitial spaces such as those within the CNS where significant local changes of pHo are known to occur (Sykova et al. 1988; Tong et al. 2000b; Menna et al. 2000).

Cardiac carbonic anhydrase

Functional expression of CAi in heart is modest (Bruns & Gros, 1992), in that it catalyses the hydration rate of intracellular CO2 ≈3-fold (Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998) as compared with erythrocytes where catalysis is ≈17000-fold (Forster, 1969). The low catalytic levels in heart may represent an ideal level of CAi function: sufficient to enhance intracellular and hence reduce spatiotemporal non-uniformity of pHi, but low enough to allow most metabolically produced CO2 to escape from the cell.

All cardiac CA appears to be bound to SR and sarcolemmal membranes (Bruns & Gros, 1992) (cytosolic isoforms have not so far been identified). A membrane-bound CA may suffice to catalyse intracellular H+ ion mobility provided some of its active sites are cytoplasmically oriented. The SR in ventricular myocytes interdigitates with t-system membranes, so that most areas of cytoplasm should be within a few micrometres of a catalytic site. Even in cardiac cells that lack a t-system, such as atrial and Purkinje cells, the SR remains highly branched in the transverse direction (Cordeiro et al. 2001) so that CA active sites should still be available throughout the cytoplasmic compartment. An SR- and sarcolemmal-bound CA could therefore readily function as the regulatory site for carbonic facilitation of H+ mobility in the cardiomyocyte.

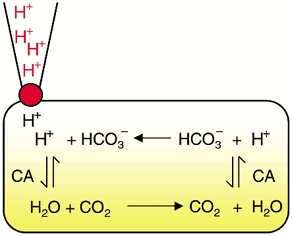

How does CA regulate mobility?

H+ ions entering the cell from a patch pipette are buffered proximally by intracellular HCO3− forming carbonic acid that dissociates into CO2 and water (illustrated in Fig. 5). While some CO2 diffuses out of the cell across the sarcolemma, some diffuses longitudinally to more distal (more alkaline) intracellular regions. There it is rehydrated, thus regenerating H+ and HCO3− ions. Some downstream diffusion of carbonic acid may also occur in parallel with CO2, again producing HCO3− distally. By these mechanisms H+ ions have, in effect, moved from a proximal to a distal region of the cell, although the H+ ions appearing distally are not the same as those injected proximally. The HCO3− that is regenerated distally then diffuses back towards proximal regions where it is available to buffer more acid diffusing from the pipette. On the scheme shown in Fig. 5, intracellular acid moves on a CO2/HCO3− shuttle, downstream via CO2 (or H2CO3) and upstream via HCO3− diffusion.

Figure 5.

Intracellular carbonic buffer shuttle showing longitudinal diffusion of CO2 and HCO3− and carbonic anhydrase (CA)-catalysed reversible hydration of CO2.

The shuttle is catalysed at two points by CA. These are the two chemical steps where CO2 and HCO3− are reversibly interconverted. The fact that carbonic buffer greatly increases apparent mobility would be consistent with turnover rate of this shuttle being faster than that of intrinsic mobile buffers (for a description of the intrinsic shuttle see Fig. 11 (top panel) of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Thus the ‘effective mobility’ of carbonic buffer appears faster than that of intrinsic buffers.

Evidence for the above model comes from the effect of inhibiting CA with ATZ. This slows the two chemical steps and, if one of these were to become rate limiting, the turnover of the shuttle would slow thus decreasing , as indeed found experimentally (Fig. 2). In the absence of CA activity, the rate constant for CO2 hydration is known to be slow (0.144 s−1, ≈400-fold slower than the reverse step (e.g. Swenson & Maren, 1978; Leem & Vaughan-Jones, 1998) and is likely to be the rate-limiting step. Furthermore, the observation that ATZ reduces to a value more similar to that seen in the absence of carbonic buffer (Fig. 4) suggests that turnover of the carbonic shuttle is now comparable to that of the intrinsic shuttle.

Effective mobility of CO2 and non-CO2 buffers in the ventricular myocyte

Provided intracellular buffers are not saturated, the apparent diffusion coefficient () can be approximated as the sum of several terms defining the mobility and fractional buffer capacity of each of the component buffers (Junge & McLaughlin, 1987; Irving et al. 1990):

| (4) |

where DH is the diffusion coefficient for H+ ions in dilute, unbuffered solution (0.9 × 10−4 cm2 s−1 at 25 °C; Vanysek, 1999), β is the buffer capacity for a given type of intracellular buffer of diffusion coefficient Dβ, and βtot is the total intracellular buffer capacity (equal to the sum of all intrinsic and CO2-dependent buffer capacities).

At physiological pHi, the first term on the right side of eqn (4) << the other terms, and can be ignored. For a cell bathed in CO2/HCO3−-buffered Tyrode solution, the right hand terms will include intrinsic and carbonic buffers.

| (5) |

where Dmob and βmob are, respectively, the diffusion coefficient lumped for all mobile intrinsic buffers (8.9 × 10−7 cm2 s−1) and their summed buffer capacity (11.4 mm/pH unit; Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Dcarb and βCO2 are, respectively, the effective diffusion coefficient and buffer capacity (eqn (2)) of intracellular carbonic buffer. Note that Dcarb does not represent the diffusion coefficient of a specified solute. It is a theoretical term, governed by the rate constants of the carbonic shuttle shown in Fig. 5. By comparing Dcarb with the diffusion coefficient for intrinsic buffer (Dmob), one may assess the effectiveness of the two buffer systems at mediating spatial H+ movement. Equation (5) has been used to estimate Dcarb using the mean values of in Hepes and in CO2/HCO3− ± ATZ (data from Fig. 4). These estimates are shown in Table 1, along with the value of Dmob. The effective mobility for carbonic buffer, Dcarb (4.47 × 10−6 cm2 s−1), is 5-fold higher than for Dmob. Interestingly, Dcarb is reduced ≈4-fold in the presence of ATZ, consistent with the suggestion (previous section) that intrinsic and carbonic buffer mobility are comparable once CA activity is inhibited.

Table 1.

Apparent diffusion coefficients (cm2 s−1) derived for intracellular, mobile intrinsic and extrinsic (CO2/HCO3−) buffer

| Intrinsic | Extrinsic | |

|---|---|---|

| Dmob | Dcarb (with CA) | Dcarb (no CA) |

| 8.9 × 10−7 | 44.7 × 10−7 | 12.2 × 10−7 |

Comparison of facilitated diffusion with facilitated diffusion of CO2

There is evidence that carbonic buffer can also facilitate the diffusion of CO2 within unstirred compartments For example, up to half of the CO2 flux across the extracellular unstirred layer (100 μm thick) of a skeletal muscle fibre is believed to occur via a facilitated mechanism (Geers & Gros, 2000). This facilitation occurs through hydration of CO2 to HCO3− which then diffuses across the unstirred layer whereupon it is reconverted to CO2, the CO2 transformations being catalysed by CA. There are therefore strong similarities between the facilitation of spatial H+ and CO2 movements, both relying upon the diffusion of HCO3− and the activity of CA. There are, however, important differences: facilitated H+ diffusion requires the back diffusion of HCO3− in a shuttle mechanism (see Fig. 5), while facilitated CO2 diffusion requires a forward movement of protonated intrinsic buffers in parallel with the HCO3− diffusion (for a review of facilitated CO2 diffusion see Geers & Gros, 2000).

Do spatiotemporal gradients of pHi occur physiologically in the heart?

Longitudinal gradients persist in CO2/HCO3−

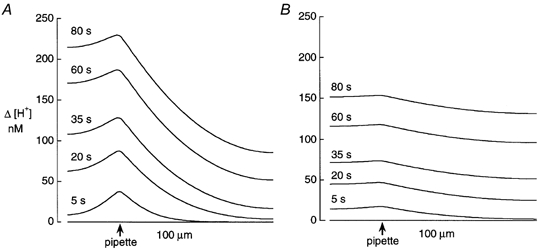

Following a local influx of acid (e.g. from a pipette or via a pH transporter), spatiotemporal gradients of intracellular H+ equivalents must occur, the question is whether they are large enough and sufficiently sustained to be of physiological significance. Figure 6 shows theoretical reconstructions of the longitudinal gradients induced by diffusion from an acid-filled pipette. These were obtained from the mathematical model described in the accompanying paper (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) while using typical values for in the absence (Fig. 6A) and presence (Fig. 6b) of carbonic buffer.

Figure 6. Modelling the longitudinal profile of [H+]i during acid diffusion from a patch pipette.

The model shows profiles predicted at different times after break-in, displayed as Δ[H+]i (nm), the increase above control levels. Length of model cell, 100 μm; width, 15 μm. Diameter pipette tip, 2 μm. Pipette site, 25 μm from left end of model cell and positioned 7.5 μm from the longitudinal edge. A, CO2/HCO3−-free conditions with = 3.8 × 10−7 cm2 s−1. B, CO2/HCO3−-buffered conditions with = 22.0 × 10−7 cm2 s−1. Model taken from Vaughan-Jones et al. (2002).

In the absence of carbonic buffer (Fig. 6A), a considerable pHi gradient is predicted during acid loading. For example, 35 s after break-in, a Δ[H+]i of 107 nm extends from the pipette to the distal end of the cell. This is equivalent to a longitudinal ΔpHi of 0.32 units (assuming initial pHi was 7.1), a gradient comparable to that seen experimentally (for example see Fig. 7 of Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). In the presence of carbonic buffer (Fig. 6b), a longitudinal pHi gradient is still predicted, but its amplitude is considerably reduced to about 20 nm, equivalent to 0.06 ΔpHi units at 35 s, and 0.04 at 80 s, again comparable to that estimated experimentally.

The above simulations illustrate that pHi microdomains persist for several tens of seconds in the presence of CO2/HCO3−, but their peak amplitude is typically < 0.1 pH units. Although modest, if such spatial differences of pHi occurred naturally, they would exert significant effects within a myocyte, given the high pH sensitivity of many spatially distributed intracellular proteins such as myofilaments (Fabiato & Fabiato, 1978), sarcolemmal channels (Irisawa & Sato, 1986) and transporters (Philipson et al. 1982), and SR Ca2+ release channels (Meissner & Henderson, 1987; Choi et al. 2000; Balnave & Vaughan-Jones, 2000).

Radial gradients

Acid diffusion from the pipette was ≈10 mm l−1 min−1, comparable to whole-cell acid efflux on sarcolemmal Na+-H+ exchange at pHi 6.5 (Leem et al. 1999), thus raising the possibility of physiologically relevant pHi gradients being generated radially during pHi regulation (Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002). Carbonic buffer will attenuate these pHi gradients, especially in myocytes with invaginated t-system membranes which express pH transporters. In cells lacking a t-system, however (e.g. atrial and Purkinje cells), modelling suggests that radial gradients may still occur in some cardiac cells in CO2/HCO3− -buffered conditions (say, ≤ 0.05 pH units), given that surface to core (i.e. radial) distances in Purkinje myocytes can be ≈15 μm in rabbit (Cordeiro et al. 1998) and up to 30 μm in dog (Boyden et al. 1989). One aim of future experimental work must be to assess the existence of radial pH microdomains.

facilitation should disappear at low pHi; relevance to myocardial ischaemia?

One assumption in the simulations illustrated in Fig. 6 is that remains constant during acid loading. While the simulations reproduce many features observed experimentally, we do not exclude the possibility that effective H+ mobility may vary, particularly during large changes of pHi. As pointed out previously (Al Baldawi et al. 1992; Vaughan-Jones et al. 2002) may decrease as mobile intrinsic buffers with pK values in the physiological range become saturated at low pHi. Facilitation of mobility by carbonic buffer may also fail at low pHi, especially during episodes of metabolic acidosis. Under these conditions intracellular HCO3− concentration decreases and, at a sufficiently low bicarbonate level, turnover of the carbonic shuttle will effectively cease (given that βCO2 in the second term on the right side of eqn (5) is proportional to [HCO3−]i). The important role of CO2/HCO3− in regulating spatial pHi uniformity will therefore be compromised during metabolic acid overload. This also predicts that facilitation by carbonic buffer may be compromised during pathological disorders, such as myocardial ischaemia, that are associated with severe metabolic acidosis. Intracellular pH non-uniformity may therefore be more prevalent under these conditions.

Conclusions

Given the ubiquitous nature of the CO2/HCO3− buffer in eukaryotic cells, its facilitation of mobility is likely to be a fundamental role. The fact that facilitation requires intracellular CA activity, an enzyme also commonly expressed in eukaryotic cells, suggests that regulation of spatiotemporal pH uniformity is a major function of the enzyme.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-42873) and the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation to K.W.S. and by grants from the British Heart Foundation and the Wellcome Trust to R.D.V.-J. We thank Dr P. R. Ershler for assistance with the confocal imaging.

REFERENCES

- Al-Baldawi NF, Abercrombie RF. Cytoplasmic hydrogen ion diffusion coefficient. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61:1470–1479. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81953-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balnave CD, Vaughan-Jones RD. Effect of intracellular pH on spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden PA, Albala A, Dresdner KP. Electrophysiology and ultrastructure of canine subendocardial Purkinje cells isolated from control and 24-hour infarcted hearts. Circulation Research. 1989;65:955–970. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns W, Gros G. Membrane-bound carbonic anhydrase in the heart. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:H577–584. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Trafford AW, Orchard CH, Eisner DA. The effect of acidosis on systolic Ca2+ and sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;529:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR. Repolarizing K+ currents in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:811–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.811bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR, Ershler PE, Cannell MB, Bridge JHB. Location of the initiation site of calcium transients and sparks in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:301–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0301i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hemptinne A, Marrannes R, Vanheel B. Surface pH and the control of intracellular pH in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1987;65:970–977. doi: 10.1139/y87-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson SJ. The carbonic anhydrase. In: Dodgson SJ, Tashian RE, Gros G, Carter ND, editors. The Carbonic Anhydrases: Cellular Physiology and Molecular Genetics. London: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Effects of pH on the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from cardiac and skeletal muscles. Journal of Physiology. 1978;276:233–255. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster RE. The rate of CO2 equilibrium between red cells and plasma. In: Forster RE, Edsall JT, Otis AB, Roughton FJW, editors. CO2: Chemical, Biological, and Physiological Aspects. Washington: NASA SP-188; 1969. pp. 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Geers C, Gros G. Carbon dioxide and carbonic anhydrase in blood and muscle. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:681–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irisawa H, Sato R. Intra- and extracellular actions of protons on the calcium current of isolated guinea pig ventricular cells. Circulation Research. 1986;59:348–355. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving M, Maylie J, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Intracellular diffusion in the presence of mobile buffers. Application to proton movement in muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1990;57:717–721. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge W, McLaughlin S. The role of fixed and mobile buffers in the kinetics of proton movement. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1987;890:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ, Podolsky RJ. Ionic mobility in muscle cells. Science. 1969;166:1297–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3910.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagadic-Gossmann D, Buckler KJ, Vaughan-Jones RD. Role of bicarbonate in pH recovery from intracellular acidosis in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. Journal of Physiology. 1992;458:361–384. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem CH, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Vaughan-Jones RD. Characterization of intracellular pH regulation in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:159–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0159z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem CH, Vaughan-Jones RD. Out-of-equilibrium pH transients in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. Journal of Physiology. 1998;509:471–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.471bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G, Henderson JS. Rapid calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles is dependent on Ca2+ and is modulated by Mg2+, adenosine nucleotide, and calmodulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menna G, Tong CK, Chesler M. Extracellular pH changes and accompanying cation shifts during ouabain-induced spreading depression. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:1338–1345. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson KD, Bersohn MM, Nishimoto AY. Effects of pH on Na+-Ca2+ exchange in canine cardiac sarcolemmal vesicles. Circulation Research. 1982;50:287–293. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AK, Boyd CAR, Vaughan-Jones RD. A novel role for carbonic anhydrase: pH gradient dissipation in mouse small intestinal enterocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000;516:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.209aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson ER, Maren TH. A quantitative analysis of CO2 transport at rest and during maximal exercise. Respiratory Physiology. 1978;35:129–159. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(78)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykova E, Svoboda J, Chvatal A, Jendelova P. Extracellular pH and stimulated neurons. Ciba Foundation Symposium. 1988;139:220–235. doi: 10.1002/9780470513699.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong CK, Brion LP, Suarez C, Chesler M. Interstitial carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity in brain is attributable to membrane-bound CA type IV. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000a;20:8247–8253. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08247.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong CK, Cammer W, Chesler M. Activity-dependent pH shifts in hippocampal slices from normal and carbonic anhydrase II-deficient mice. Glia. 2000b;31:125–130. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(200008)31:2<125::aid-glia40>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanysek P. Ionic conductivity and diffusion at infinite dilution. In: Lide DR, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, section 5, Thermochemistry, Electrochemistry and Kinetics. 79. London: CRC Press; 1999. pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Jones RD, Ershler PR, Skolnick RL, Spitzer KW. Slow intracellular H+ mobility regulated by carbonic anhydrase activity in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2000a;78:223A. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Jones RD, Erschler P, Skolnick R, Spitzer KW. Intracellular H+ mobility is facilitated by carbonic anhydrase activity in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2000b;527.P:67P. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Jones RD, Peercy BE, Keener JP, Spitzer KW. Intrinsic H+ ion mobility in the rabbit ventricular myocyte. Journal of Physiology. 2002;541:139–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]