Abstract

Various cardio-active stimuli, including endothelin-1 (ET-1), exhibit potent arrhythmogenicity, but the underlying cellular mechanisms of their actions are largely unclear. We used isolated rat atrial myocytes and related changes in their subcellular Ca2+ signalling to the ability of various stimuli to induce diastolic, premature extra Ca2+ transients (ECTs). For this, we recorded global and spatially resolved Ca2+ signals in indo-1- and fluo-4-loaded atrial myocytes during electrical pacing. ET-1 exhibited a higher arrhythmogenicity (arrhythmogenic index; ratio of number of ECTs over fold-increase in Ca2+ response, 8.60; n = 8 cells) when compared with concentrations of cardiac glycosides (arrhythmogenic index, 4.10; n = 8 cells) or the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (arrhythmogenic index, 0.11; n = 6 cells) that gave similar increases in the global Ca2+ responses. Seventy-five percent of the ET-1-induced arrhythmogenic Ca2+ transients were accompanied by premature action potentials, while for digoxin this proportion was 25 %. The β-adrenergic agonist failed to elicit a significant number of ECTs. Direct activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptors with a membrane-permeable InsP3 ester (InsP3 BM) mimicked the effect of ET-1 (arrhythmogenic index, 14.70; n = 6 cells). Inhibition of InsP3 receptors using 2 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, which did not display any effects on Ca2+ signalling under control conditions, specifically suppressed the arrhythmogenic action of ET-1 and InsP3 BM. Immunocytochemistry indicated a co-localisation of peripheral, junctional ryanodine receptors with InsP3Rs. Thus, the pronounced arrhythmogenic potency of ET-1 is due to the spatially specific recruitment of Ca2+ sparks by subsarcolemmal InsP3Rs. Summation of such sparks efficiently generates delayed afterdepolarisations that trigger premature action potentials. We conclude that the particular spatial profile of cellular Ca2+ signals is a major, previously unrecognised, determinant for arrhythmogenic potency and that the InsP3 signalling cassette might therefore be a promising new target for understanding and managing atrial arrhythmia.

In the heart, Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is a key event during the process of excitation- contraction coupling and is believed to be triggered through the mechanism of Ca2+-induced Ca2+-release (CICR). Essentially, Ca2+ influx via voltage-operated Ca2+ channels is amplified by the liberation of Ca2+ from the lumen of the SR (Callewaert, 1992). The release is mediated by the concerted opening of specialised Ca2+ release channels, the ryanodine receptors (RyRs) on the membrane of the SR. Such rhythmic Ca2+ responses, i.e. the occurrence of a single Ca2+ signal following an action potential, represent the physiological behaviour of the cardiac cell. Under a variety of patho-physiological conditions, altered membrane currents can disturb the heartbeat. The origin of such alterations can be either changes in the expression pattern of ion channels or direct modulation of the gating of channels (Keating & Sanguinetti, 2001). Modified gating of the potassium currents, such as the delayed rectifier, for example, may lead to delayed repolarisation and can result in the reactivation of the L-type Ca2+ current, referred to as early afterdepolarisations (EADs; Fozzard, 1992). Very rapid and dynamic modulation of membrane currents can occur on a beat-to-beat basis through the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Thus, spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR has been implicated to evoke depolarising membrane currents (such as Iti) and delayed after-depolarisations (DADs) under conditions of cellular Ca2+ overload (Berlin et al. 1989; Fozzard, 1992). Recent evidence points to the direct involvement of agents such as endothelins, angiotensins and α-adrenergic agonists in the generation of cardiac arrhythmia (for reviews see Golfman et al. 1991; Woodcock et al. 1998) but their detailed cellular and subcellular mode of action is largely unclear.

In contrast to ventricular arrhythmia, such as ventricular fibrillation, that are life-threatening conditions, atrial arrhythmias exhibit more modest effects on the circulation. Atrial arrhythmias are the most common forms of long lasting or continuous cardiac arrhythmia and the risk of stroke is increased 5- to 7-fold (Ezekowitz, 1999). Despite their widespread occurrence (e.g. almost 20 % of the entire population at the age of 75 years display atrial arrhythmias; Ezekowitz, 1999) our understanding of their cellular mechanisms, particularly in relation to the hormonal agents mentioned above, is sparse.

One mechanism that has been suggested for the arrhythmogenic action of stimuli such as ET-1 involves coupling to the Gq-phospholipase C (PLC) signalling pathway, resulting in the mobilisation of the second messenger InsP3 (Golfman et al. 1991). In many cell types, this messenger engages its subcellular binding site on the InsP3 receptor (InsP3R) and causes release of Ca2+ from the Ca2+ storing organelle (Berridge et al. 2000). In heart, the presence and importance of this intracellular Ca2+-release channel is controversial (for example see Woodcock et al. 1998; Marks, 2000). In the present study, we investigated the effects of various inotropic agents in causing arrhythmogenic Ca2+ release events in rat atrial myocytes. Furthermore we correlated their arrhythmogenicity to the characteristic subcellular Ca2+ release patterns, with particular emphasis on the putative involvement of InsP3Rs.

METHODS

Rat atrial myocytes were isolated from male Wistar rats (∼250 g, 8 weeks in age) by established enzymatic isolation methods (Lipp et al. 2000). For this, the animal was killed by cervical dislocation after CO2 anaesthesia, as approved by the Babraham Institute's ethical committee (Schedule 1 killing in accordance with Home Office regulations). The heart was removed quickly and placed into a Langendorff apparatus after which cell isolation was performed as described earlier (Lipp et al. 2000). Single cells were kept in an extracellular medium (EM) containing (mm): NaCl 135, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 1, glucose 10, Hepes 10, pH 7.35. The osmolarity of all solutions was verified with an osmometer (Roebling Osmometer, Camlab, Cambridge, UK).

All experiments were performed at room temperature (20-22 °C). In our hands, at that temperature Ca2+ indicators (either indo-1 or fluo-4) are better retained inside the myocytes and are not transported out so quickly by unspecific anion transporters (see Thomas et al. 2000). This process will lead to a decreased indicator level and thus decreased signal-to-noise ratio. We have performed control experiments at 37 °C and found that apart from faster onsets of the effects (for all agonists, isoproterenol, digoxin, ET-1 and InsP3 BM) there was no qualitative change in the results (data not shown). Due to the indicator problem and the fact that the slower response of the cells to the application of the agonists allowed us to perform a more detailed analysis of the time course of those processes, we chose to do the study at room temperature.

The experiments involving global Ca2+ concentration measurements were carried out on a PhoCal system (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Cambridge, UK). For this, the cells were loaded with indo-1 (40 min in EM with 2 μM indo-1 AM, 20 min de-esterification). Indo-1 was excited at 360 nm and the fluorescence was simultaneously monitored at 405 nm (F405) and 490 nm (F490). The Ca2+ concentration is expressed as the background corrected ratio of F405/F490. The recording protocol comprised repetitive 30 s illumination and 60 s resting periods. All compounds were applied via a solenoid-driven perfusion system with an exchange time of ∼1 s.

For confocal recording, the cells were loaded with fluo-4 (20 min in EM with 2 μM fluo-4 AM, 20 min de-esterification) and transferred onto the stage of a real-time confocal microscope (NORAN Oz, Middleton, USA). Confocal images (512 × 115 pixels) were acquired at a rate of 30 Hz (4 consecutive images at 120 Hz were averaged, z section < 1 μm). Analysis of the confocal movies was performed with a customised version of NIH Image or ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, USA). The fluo-4 fluorescence (excitation 488 nm, emission > 500 nm) was converted into Ca2+ concentrations by methods described earlier (Lipp et al. 2000). Cells were electrically paced with two field electrodes (0.3 Hz, 40 V, 2 ms durat ion).

Patch-clamp experiments were performed in the whole-cell mode with pipettes (series resistance ∼2 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing (mm): KCl 135, NaCl 10, EGTA 0.1, MgATP 3, MgCl2 1, Hepes 10 at pH 7.3. The membrane potential was recorded with an EPC-9 patch-clamp amplifier system (HEKA, Germany) that also provided brief (∼2 ms) current injections to evoke action potentials. The amplitude of the current injection varied between cells but was set 20 % higher than the threshold current necessary for triggering an action potential under control conditions.

The immunocytochemistry was carried out as described elsewhere (Lipp et al. 2000). We used confocal microscopy (UltraView, Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Cambridge, UK) to probe the subcellular distribution of either Texas Red- or fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Averaged fluorescence from subcellular locations was further analysed with IGOR software (Wavemetrics, USA). Statistical significance was tested using Student's t test or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test where indicated (Statistica 5.0, StatSoft, USA).

We identified ECTs as spontaneous Ca2+ increases whose amplitudes exceeded two times the standard deviation of the time-dependent variations in the Ca2+ concentration at rest. Detailed analysis of the ECTs was only performed when the Ca2+ transient peaked at least 300 ms after the peak of the electrically induced Ca2+ response.

RESULTS

Arrhythmogenicity and increases in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients are not directly correlated

Application of ET-1 to electrically paced rat atrial myocytes caused increases in the amplitude of the electrically evoked Ca2+ responses that coincided with the occurrence of arrhythmogenic extra Ca2+ transients (ECTs; Fig. 1A and B). These ECTs are generally attributed to an increase in the cellular Ca2+ load. However, application of concentrations of isoproterenol and digoxin to cells that gave Ca2+ responses of similar amplitude as ET-1 (Fig. 1Ba) revealed that there was no direct correlation between the Ca2+ signal amplitude and likelihood of spontaneous Ca2+ release (i.e. number of diastolic spontaneous ECTs; Fig. 1Bb). In order to quantify the effect of each stimulus to evoke ECTs and also normalise for differences in the increase of the electrically evoked Ca2+ signals, we estimated the arrhythmogenic index (AI) for each condition as the ratio of the number of ECTs (per 30 s recording period) relative to the increase in the global Ca2+ signal (determined when the Ca2+ increase had reached a steady state). For this, we counted the number of ECTs during a 30 s recording period and divided that value by the fold increase in the normalised amplitude of the electrically evoked Ca2+ response (normalised to the control values before application of the agonist). Digoxin (AI, 4.1; n = 8 cells) was approximately half as effective as ET-1 (8.6; n = 8 cells), whilst isoproterenol gave very few ECTs (0.1; n = 6 cells) despite a rapid and robust enhancement of the Ca2+ responses that even superseded ET-1 or digoxin-induced increases (268 ± 23 %; n = 6 cells for isoproterenol vs. ∼170 % for ET-1 (± 31) and digoxin (± 25); n = 8 cells for both). These data suggest that (i) increasing Ca2+ influx through phosphorylation of L-type Ca2+ channels (isoproterenol), (ii) loading of the SR with Ca2+ by phosphorylation of phospholamban (isoproterenol), (iii) increasing Ca2+ influx via Na+-Ca2+ exchange (digoxin) or (iv) sensitisation of ryanodine receptors (digoxin; McGarry & Williams, 1993) are not necessarily sufficient to cause spontaneous Ca2+ release. Clearly, the other agents used in this study did not mimic ET-1′s arrhythmogenicity. It was particularly interesting to observe the lack of ECTs during the duration of isoproterenol application (here up to 10 min), a β-adrenergic agonist, despite the most robust increase in the Ca2+ transient amplitude, since β-adrenergic receptor activation is believed to be a major arrhythmogenic stimulus in ventricular tissue (Talukder et al. 2001). Indeed, in parallel experiments conducted on rat ventricular myocytes, we found that during similar observation periods the substantial increases of the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals observed during application of the β-adrenergic agonist were accompanied by the occurrence of a large number of ECTs (data not shown). This suggests differences in the hormonal response in atrial and ventricular myocytes that we did not pursue further in this study.

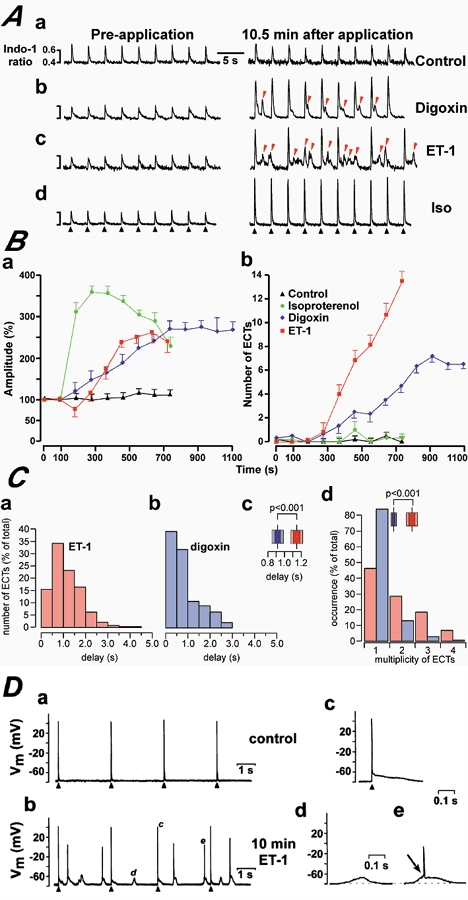

Figure 1. ET-1 evoked increases in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients, ECTs and action potentials.

A depicts representative traces showing the effects of application of the bath solution (control, Aa), digoxin (1 μM, Ab), ET-1 (0.1 μM, Ac) and isoproterenol (0.1 μM, Ad) on electrically paced atrial cells. The black arrowheads indicate the timing of electrical stimulation. ECTs were marked with red arrowheads for ET-1 and digoxin. B, summarises the responses of isolated indo-1-loaded electrically paced rat atrial myocytes to application of isoproterenol (green circles), digoxin (blue diamonds) and ET-1 (red squares). Ba depicts the change in relative amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients (data points were normalised against the Ca2+ transient amplitude prior to drug addition). Bb shows the development of ECTs. The data points represent averaged values of at least 6 cells for each condition. The drugs were applied after a 120 s control period. C, depicts the detailed analysis of peak-to-peak times for ET-1- and digoxin-induced ECTs. For this we measured the time delay between the peak of the electrically evoked Ca2+ signals and the peak of the ECT. The resulting histograms are shown in Ca for ET-1 and Cb for digoxin. The statistical analysis with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (Statistica 5.0, StatSoft, USA) showed a mean delay of 1.15 ± 0.046 s for ET-1 (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 250) and 0.92 ± 0.043 s for digoxin (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 225). The resulting P value (P < 0.001) demonstrated a significantly different distribution of the time delays. This is summarised in Cc, which also indicates the confidence intervals of 1 × s.e. (dark colouring) and 2 × s.e. (light colours) for ET-1 (red) and digoxin (blue). Panel Cd illustrates the distribution of the number of ECTs following a single action potential in the presence of ET-1 (red) and digoxin (blue). The statistical analysis with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated mean values of 1.82 ± 0.07 (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 250) for ET-1 and 1.07 ± 0.04 (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 225) for digoxin. The resulting P value (P < 0.001) suggested significantly different distributions. The inset illustrates the confidence intervals (see Cc for description). D, shows membrane potential recordings from patch-clamped atrial myocytes. The cells were stimulated as indicated by the black arrowheads. Da depicts membrane potential recordings under control conditions. 10 min after application of 0.1 μM ET-1, numerous diastolic membrane potential changes were recorded (panel Db). The events marked with corresponding characters in Db were redrawn at an expanded timescale in Dc, d and e to illustrate an evoked action potential (Dc), a premature action potential (De) and a subthreshold DAD (Dd). The transition from a subthreshold DAD to a premature action potential is indicated by the arrow in De.

These data suggested that there is a difference between the digoxin- and ET-1-induced ECTs, at least in their probability of occurrence for similar levels of Ca2+ transient increases. To further substantiate such a different characteristic of the two types of ECTs, we performed a detailed analysis of the distribution of the time delays, with which the ECTs occurred after the electrically evoked Ca2+ signals during ET-1 and digoxin stimulation (Fig. 1C). The two histograms summarise the peak-to-peak times for ET-1 (red) and digoxin (blue). Although both distributions seemed to be skewed towards shorter intervals, this tendency was more apparent in the digoxin distribution. We thus analysed the statistical significance of a different spreading between these two groups. Since the two data sets were not normally distributed, we used a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which aside from mean values and variances also takes into account general shape differences between the two data sets. The analysis showed mean values of 1.15 ± 0.046 s for ET-1 (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 250) and 0.92 ± 0.043 s for digoxin (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 225) with P < 0.001 (see Fig. 1Cc). From these results we suggest that the ECTs generated during digoxin superfusion have the tendency towards shorter delay times than those during ET-1 stimulation, which seem to occur at longer time intervals after an evoked action potential. Such a difference might hint to diversity in the underlying mechanism of generation (see Discussion). This was further substantiated by the fact that ET-1 induced multiple ECTs following a single action potential-induced Ca2+ signal (54 % of all ECTs) while digoxin predominantly caused single ECTs (only 14 % of all ECTs were multiple ones; Fig. 1Cd).

From electrophysiological recordings performed in parallel, we further characterised the ET-1-induced ECTs and found that they caused either subthreshold delayed after-depolarisations (DADs, Fig. 1Dd), which would remain locally in the intact tissue or suprathreshold DAD-induced premature action potentials that could potentially propagate through neighbouring cells (75 % of all ECTs; n = 83 from 4 cells; Fig. 1D). In contrast, digoxin-induced ECTs were mainly characterised as subthreshold DADs (70 %; n = 79 from 4 cells; data not shown) and were thus less arrhythmogenic in terms of their potency to trigger premature action potentials.

The subcellular properties of ET-1- and digoxin-induced ECTs

To understand the different effects of the ET-1- and digoxin-evoked ECTs with respect to the generation of action potentials, we examined the subcellular properties of these ECTs using video-rate laser-scanning confocal microscopy. For ET-1-stimulated cells, all ECTs occurred as highly localised subsarcolemmal Ca2+ increases (Fig. 2A). Subthreshold DADs (Fig. 2Abi) appeared as a burst of Ca2+ sparks forming a non-regenerative ‘ring’ of Ca2+ around the cell periphery (Fig. 2Ac and e), i.e. this ring did not cause CICR in deeper layers of the cytosol. In contrast to that, suprathreshold DADs (Fig. 2Abiii) appeared initially as a ring of Ca2+ sparks subsequently triggering a Ca2+ signal in deeper layers of the cell indicative of an action potential (i.e. synchronised activation of many Ca2+ sparks; Fig. 2Ad; Mackenzie et al. 2001; similar observations were made elsewhere, Hüser et al. 1996; Kockskämper et al. 2001). Application of digoxin to myocytes did not evoke subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks, instead digoxin-evoked ECTs were almost exclusively Ca2+ waves (>90 %; n = 36; data from 4 cells; Fig. 2B) of random subcellular origin (Berlin et al. 1989). All digoxin-evoked Ca2+ waves analysed displayed varying subcellular origins, with multiple wave origins in the same cell. Ca2+ waves either propagated through a part of the atrial myocyte before dying out or occupied a sufficient cytoplasmic volume to trigger a premature action potential (Fig. 2Bbii).

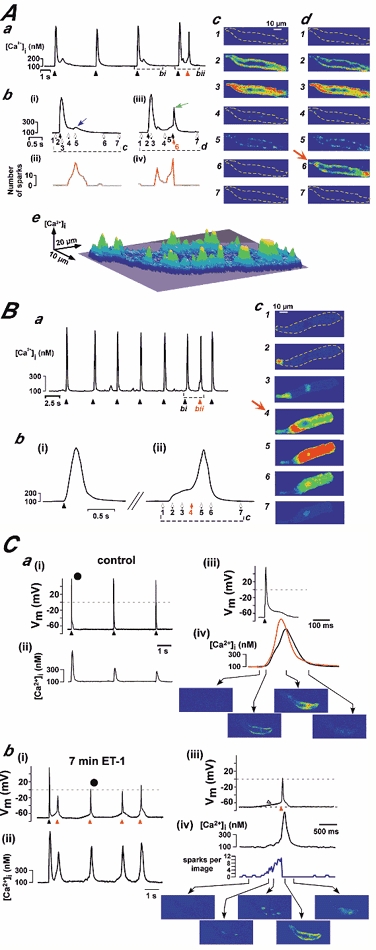

Figure 2. Subcellular properties of ET-1- and digoxin-evoked ECTs.

Aa shows the global Ca2+ concentration from a cell stimulated with 0.1 μM ET-1 for 8 min. The black arrowheads indicate the timings of electrical stimulations, and the red arrowhead depicts a Ca2+ signal from a premature action potential. The portions of traces bounded by dashed lines in Aa are shown on expanded timescales in Abi and iii. The numbered arrows beneath the traces indicate the time points at which the confocal images shown in Ac and Ad were taken. The expanded trace in Abi and the corresponding confocal images in Ac show an evoked action potential that was followed by a Ca2+ signal accompanied by a sub-threshold DAD (blue arrow) during which subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks were observed (see Ac5). Panels Abii and Abiv illustrate the time course of the occurrence of identifiable Ca2+ sparks. For this, every confocal image was analysed and the number of Ca2+ sparks plotted against time. The sudden disappearance of Ca2+ sparks in Abiv indicated the generation of an action potential (see panel C for further verification). The 3D-surface representation of Ac5 shown in Ae emphasises the peripheral nature of Ca2+ release, indicated by the local elevations around the circumference of the cell. The evoked action potential shown in Abiii was followed by a ring of subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks that subsequently triggered a premature action potential (see corresponding confocal images in Ad, marked by a green arrow). B, depicts a similar analysis as shown in A for a cell stimulated with 1 μM digoxin for 8 min. Panel Ba illustrates the global Ca2+ concentration response. The black arrowheads indicate the timings of electrical stimulation, and the red arrowhead denotes a premature action potential. The portion of the trace bounded by a dashed line in Ba is shown on an expanded timescale in Bb. The numbered arrows below the trace in Bbii indicate the times at which the confocal images shown in Bc were taken. These data are typical of the responses of 5 cells (from 4 hearts each) for both ET-1 and digoxin. C, illustrates simultaneous recordings of the membrane potential (Cai and iii and Cbi and iii) and subcellular Ca2+ signals (Caii and iv and Cbii and iv). Ca depicts the recordings under control conditions, while Cb shows the same cell 7 min after application of 100 nm ET-1. The black arrowheads in Cai mark events of electrical field stimulation. The action potential marked • was redrawn in Caiii and iv at an expanded time scale. Here, the red tracing was averaged from peripheral Ca2+ release sites, while the black tracing was obtained from a deeper layer inside the atrial myocyte. Selected self-ratioed confocal images are shown in the lower part of Caiv. The data depicted in Cb was recorded at the end of a train of evoked action potentials (10 action potentials, 1 Hz). The black arrowhead marks the last stimulation of that train while the red arrowheads identify spontaneous action potentials. The premature action potential marked • was redrawn in Cbiii and iv at an expanded time scale. Selected self-ratioed confocal images are shown in the lower part of Cbiv. The increase in the number of visible Ca2+ sparks during the DAD (marked by the open arrowhead) and the abrupt decline upon generation of the action potential (red arrowhead) are apparent. Similar results were obtained in 4 cells from 2 hearts.

Experiments were conducted to further verify and confirm the identification of sub-threshold and supra-threshold DADs. We used simultaneous recording of the membrane voltage and Ca2+ concentration to characterise the basis of the subcellular pattern of the underlying Ca2+ release signal (Fig. 2C). Under control conditions (Fig. 2Ca) each external electrical stimulation is followed by a regular Ca2+ transient. The time series of confocal images in Fig. Caiv shows the typical ‘Ca2+ ring’ during ec-coupling described previously (Mackenzie et al. 2001). Seven minutes after application of ET-1 (100 nm) another train of stimuli was applied, of which Fig. Cbi and ii depict the last stimulation (black arrowhead) and the following train of spontaneous action potentials (marked by the red arrowheads). The detailed analysis of the selected spontaneous action potential (marked with the black circle) shown in Fig. 2Cbiii and iv indicates that indeed the DAD (open arrowhead) is generated by an increased frequency of peripheral Ca2+ sparks (see also Fig. 2Abi and ii) while the transition from the subthreshold membrane depolarisation to the action potential (red arrowhead) is clearly marked by an abrupt and complete disappearance of Ca2+ sparks (Fig. 2Cbiv, see also 2Abiii and iv). From these data we suggest that the identification and distinction of sub-threshold and supra-threshold Ca2+ signals (and DADs) is indeed possible on the basis of the pattern of the underlying Ca2+ release signals. Sub-threshold as well as supra-threshold Ca2+ transients (and DADs) are generated by the gradual build-up of the frequency of peripheral Ca2+ sparks while the successful triggering of a premature action potential is indicated by the abrupt loss of visible Ca2+ sparks.

Involvement of InsP3Rs in arrhythmogenicity and increases of the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals

InsP3Rs are expressed in the heart (Moschella & Marks, 1993; Gorza et al. 1993; Perez et al. 1997; Lipp et al. 2000) and their expression pattern changes during various cardiac pathologies that are associated with different forms of arrhythmia (Go et al. 1995; Marks, 2000). We therefore sought to examine the involvement of InsP3Rs in ET-1-induced ECTs. In order to avoid the pleiotropic effects of phospholipase C (PLC) activation (Golfman et al. 1991), we evoked InsP3R gating directly by superfusing cells with a membrane-permeant ester of InsP3 (InsP3 BM; Lipp et al. 2000). In contrast to ET-1, application of InsP3 BM caused a much smaller increase in the amplitude of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients (58 ± 24 %; n = 6 cells; Fig. 3A). However, its ability to induce ECTs was comparable with 100 nm ET-1 (Fig. 3A and B). These findings support our earlier notion of the dissociation between increases in the global Ca2+ response and arrhythmogenicity. In the presence of ET-1 or InsP3 BM cells often passed into a state of ‘cellular fibrillation’, indicated by the rapid drop in the Ca2+ transient amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals (Fig. 3A; filled black circles after 15 min). We apply this picturesque term of ‘cellular fibrillation’ if an atrial myocyte displayed Ca2+ transients at such a high frequency that: (i) the individual Ca2+ signals started to largely fuse and (ii) it was virtually impossible to identify individual Ca2+ signals caused by electrical stimulation. In addition, under these conditions no co-ordinated contraction of the myocyte could be observed (data not shown). Only the biologically active d-myo-inositol stereoisomer of InsP3 BM was capable of evoking ECTs and ‘cellular fibrillation’, whereas the l-myo-InsP3 BM isomer was inactive (data not shown), indicating that the action of the ester was highly specific.

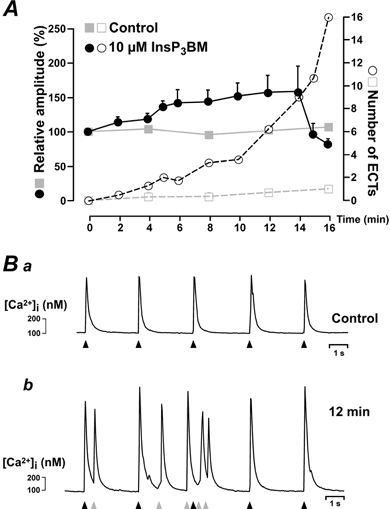

Figure 3. Direct InsP3R activation evoked increases in the amplitude of electrically induced Ca2+ transients and ECTs.

A shows the time course of the relative amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals (filled symbols) and the occurrence of ECTs (open symbols) for control cells (grey symbols) and InsP3 BM stimulated cells (black symbols). The data were averaged from 3 control cells and 6 InsP3 BM-treated cells loaded with indo-1. Ba and Bb show the global Ca2+ signals (calculated from the fluo-4 fluorescence) in an atrial myocyte before, and 12 min after, InsP3 BM addition, respectively. The black arrowheads indicate the timings of electrical simulation. The diastolic ECTs were observed as subsarcolemmal Ca2+ rises and are marked with grey arrowheads. Similar results were observed in 6 cells from 3 hearts.

Additional evidence for the role of InsP3 in generating ECTs during ET-1 application was obtained using the membrane permeant InsP3R antagonist 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB; Maruyama et al. 1997). This compound rapidly and reversibly inhibited both the increase in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals and the ECTs occurring during InsP3 BM application (Fig. 4A). The generation of ECTs was completely abrogated (Fig. 4Ab). Since several recent reports suggested effects of 2APB other than on the InsP3 receptor (see for example Broad et al. 2001), we conducted a series of control experiments. We first tested whether 2 μM 2APB affects normal atrial ec-coupling and found that at this concentration 2APB did not cause any changes on normal atrial Ca2+ signals up to durations of more than 30 min (n = 4 cells from 3 hearts; data not shown). For this we applied 2APB onto atrial myocytes during constant electrical stimulation at 0.3 Hz and analysed the amplitude and the time course (upstroke and relaxation) of the Ca2+ transients (data not shown). Application of 2APB did not affect any of these parameters at lower concentrations (∼2 μM). Higher concentrations of 2APB (> 30 μM) suppressed atrial ec-coupling (electrical pacing did not cause any increases in the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and the cells stopped contracting) in a concentration and time-dependent manner (data not shown) indicating that at those high concentrations it started to display non-specific effects. From this we concluded that 2APB at the concentration of 2 μM used here appears to be an appropriate tool for inhibiting InsP3 action in cardiac myocytes without interfering with normal ec-coupling.

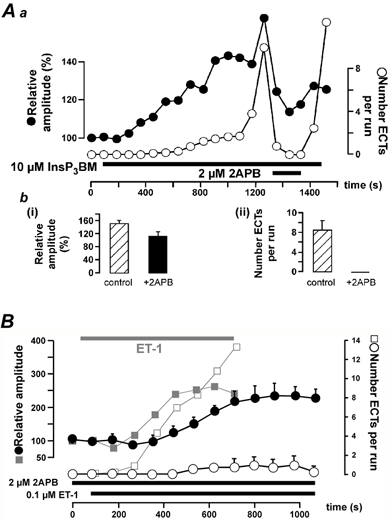

Figure 4. 2APB suppressed InsP3 BM- and ET-1-evoked ECTs.

Aa shows the reversible inhibitory effect of 2APB on InsP3 BM-induced increases in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ responses (filled symbols) and ECTs (open symbols). The timing of InsP3 BM and 2APB application is indicated by the black bars. Ab summarises the effect of 2APB on the positive inotropy (Abi) and ECTs (Abii); n = 9 cells from 3 hearts. The responses were analysed just before 2APB application ( ) and 3 min after 2APB administration (▪). The effect of 2APB on ET-1 application is depicted in B. The greyed curves in the background show data taken from Fig. 1Ba and b to allow comparison of the effect of ET-1 in the absence of 2APB. The timing of ET-1 and 2APB application is indicated by the black bars.

) and 3 min after 2APB administration (▪). The effect of 2APB on ET-1 application is depicted in B. The greyed curves in the background show data taken from Fig. 1Ba and b to allow comparison of the effect of ET-1 in the absence of 2APB. The timing of ET-1 and 2APB application is indicated by the black bars.

The antagonist 2APB caused a small but non-significant reduction in the amplitude of the ET-1 response (reduction to 75 ± 38 %; P > 0.01) and delayed its development (Fig. 4B; filled circles). The maximal ET-1-induced increase in pacing-evoked Ca2+ transient amplitude was 259 ± 20 % in the absence, and 229 ± 19 % in the presence of 2 μM 2APB. In contrast to its weak effect on ET-1-evoked increases in the Ca2+ transients, 2-APB reduced the occurrence of ECTs on average by 93 % (n = 6 cells from 4 hearts; Fig. 4B; open circles). These data suggest a pivotal role for InsP3Rs in the arrhythmogenic component of the ET-1 response. The persistent amplitude increase of the electrically induced Ca2+ responses evoked by ET-1 during InsP3R inhibition most likely reflects the remaining activation of mechanisms downstream of PLC (Golfman et al. 1991) such as increased Ca2+ currents via PKC-dependent phosphorylation of L-type Ca2+ channels (He et al. 2000) which would allow for an increased cellular response.

Localisation of InsP3Rs and distribution of Ca2+ release likelihood

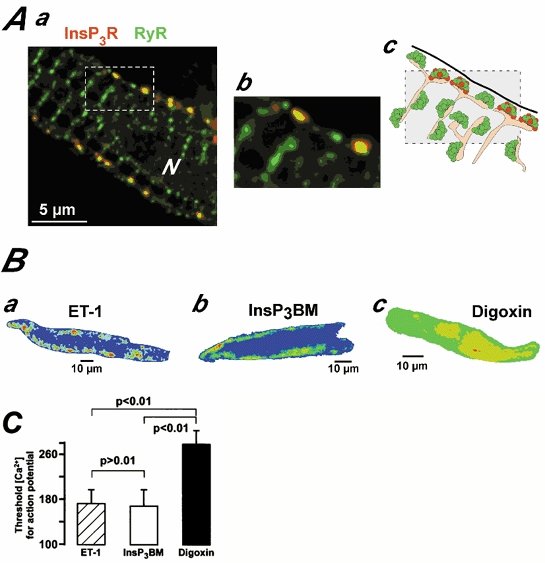

The immunolocalisation of InsP3Rs and RyRs in atrial myocytes indicated that the InsP3R type II (red staining in Fig. 5A) co-localised with part of the junctional RyR type II (green staining in Fig. 5A) population. A cartoon representation of these findings is given in Fig. 5Ac. These data support the idea of a signalling microdomain comprised of these two Ca2+-release channels. We estimated the subcellular Ca2+ release likelihood during ET-1-, InsP3 BM- and digoxin-induced ECTs (i.e. the subcellular locations where ECTs were most commonly observed) by averaging 4-6 consecutive confocal images around the peak of 8 subthreshold ECTs for every stimulus, and colour coded the resulting images so that warmer colours would indicate higher Ca2+ release likelihood and cooler colours would indicate lower release likelihood.

Figure 5. The localisation of InsP3Rs and RyRs correlates with the distribution of Ca2+ release likelihood.

Aa depicts a rat atrial myocyte probed for InsP3Rs type II (red) and RyR type II (green). N denotes the cell nucleus. Ab shows the part of the cell marked in Aa with a dashed box at a higher magnification. A schematic cartoon of the arrangement of plasma membrane (thick black line), SR (orange filled) and Ca2+ release channel clusters (green-RyRs and red-InsP3Rs) is depicted in Ac. B, distribution of SR Ca2+ release likelihood from ECTs during ET-1 (Ba), InsP3 BM (Bb) and digoxin (Bc) application. For the images, confocal sections of 8 subthreshold ECTs were superimposed and averaged (each ECT was derived from 4-6 consecutive confocal images taken around the peak of the signal). The resultant image was colour coded with cool colours (blue, green) denoting low Ca2+ release likelihood and warm colours (red, yellow) indicating high Ca2+ release likelihood. Similar distributions were found in all cells analysed. For Bc the same cell was used as in Fig. 2Bc. C compares threshold Ca2+ concentrations for triggering premature action potentials during ET-1 ( ), InsP3 BM (□) and digoxin (▪) application.

), InsP3 BM (□) and digoxin (▪) application.

Our results indicated that spontaneous Ca2+ release was distributed in a characteristic fashion for each stimulus. In particular, the ECTs caused by both ET-1 and InsP3 BM showed an increased likelihood of occurring in subplasmalemmal locations (Fig. 5Ba and b). This further substantiates the involvement of subsarcolemmal RyR/InsP3R signalling microdomains in the action of ET-1 and InsP3 BM. In contrast, digoxin displayed a largely homogeneous Ca2+ release likelihood (Fig. 5Bc), which was due to the Ca2+ waves exhibiting randomised subcellular origins (see also Berlin et al. 1989).

These spatially distinct distributions of the Ca2+ release likelihood are also reflected in the threshold Ca2+ concentration needed to trigger an action potential for the various stimuli (Fig. 5C). For this, we analysed 31 ECTs for each condition. We identified the transition from a subthreshold Ca2+ signal (and DAD) to a transient indicative of a triggered action potential in two independent ways. (i) First, we averaged the global, whole cell fluorescence. In such traces, the transition between the spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and the action potential-induced Ca2+ sparks was clearly visible as the inflection point in the trace, where the Ca2+ concentration began to rise abruptly (see Fig. 2Abiii and Cb). (ii) Second, we analysed the occurrence of Ca2+ sparks. During the subthreshold DAD, Ca2+ sparks arise in a subsarcolemmal localisation in a random fashion, but at the onset of an action potential they appear highly synchronised (see also Mackenzie et al. 2001). The global Ca2+ concentration at that time was taken as the threshold concentration. For Ca2+ waves that triggered an action potential, as seen most frequently during digoxin application, the threshold was identified as the occurrence of a partial ring of Ca2+ sparks, as seen in Figure 2Bc 3 and 4. The global Ca2 + concentration at that time was taken as the threshold concentration for an action potential. While ET-1 and InsP3 BM displayed a consistently low threshold (∼170 nm; hatched and open bar in Fig. 5C), the digoxin-induced ECTs had to generate a much more substantial global Ca2+ rise (threshold ∼270 nm; black bar in Fig. 5C) before triggering an action potential.

These data suggest that the arrhythmogenicity of agents that act on cardiac myocytes cannot simply be estimated based on their ability to increase the cellular Ca2+ load or sensitisation of the Ca2+ release mechanism. Instead, the stimulus-specific spatial recruitment of Ca2+ release appears to be a central determinant for cellular arrhythmogenicity in atrial myocytes.

DISCUSSION

Atrial arrhythmias are the most common form of long lasting cardiac arrhythmias and thus it is of immediate interest to understand their cellular basis and to investigate possible novel targets for managing these cardiac pathologies. Although the involvement of signalling pathways, such as those activated by ET-1, angiotensin-II or α-adrenergic agonists, are implicated in the generation of cardiac arrhythmia, their cellular action is largely unknown. This seems surprising when taking into account recent evidence for their contribution to the death rate in chronic heart failure (Sakai et al. 1996). In the present study, we investigated possible cellular mechanisms of hormone action contributing to the generation of cardiac arrhythmia with particular emphasis on the atrium. We used the rat atrial myocyte as an animal model cell system, since: (i) inhibition of ET-1 receptors had been shown to substantially increase the survival rate in a rat model of cardiac hypertrophy (Sakai et al. 1996) and (ii) ET-1 receptors promote phospholipid turnover in rats (Woodcock et al. 1995) which is associated with production of inositol phosphates. In addition, we have recently reported that activation of InsP3 receptors in rat atrial myocytes can substantially increase the occurrence of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks, the principal building blocks of cardiac Ca2+ signalling (Lipp et al. 2000). Here, we present evidence, that amongst all agonists tested, ET-1 exhibited the highest rate of spontaneous diastolic Ca2+ transients despite similar degrees of increases in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients. In order to quantify this property, we calculated the ‘arrhythmogenic index’ (AI) as the ratio between the number of ECTs during a recording period (30 s) and the fold increase in the amplitude of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients. The results of such calculations revealed the prominent status of ET-1 with an AI of 8.60 (digoxin 4.10; isoproterenol 0.11), which was only superseded by a direct activation of InsP3Rs with its natural ligand derived from the membrane permeant ester, InsP3 BM (AI, 14.70). We were surprised by the pronounced ability of InsP3 BM to predominantly generate ECTs while the increases in the Ca2+ response amplitude were only modest. Nevertheless, these findings were in line with the experiments in which we blocked InsP3Rs with 2APB. Here, we found that 2APB predominantly inhibited the occurrence of ET-1-induced ECTs while the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients was not affected significantly (Fig. 4B). Both results taken together clearly point to the fact that the mechanisms, responsible for ECT generation and the increase in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ responses might be different. Following the application of ET-1, the majority of the ECTs are generated by the activation of InsP3Rs in the periphery, while the Ca2+ response amplitude can be increased by PKC-dependent phosphorylation of L-type Ca2+ channels and the resulting increased Ca2+ influx during the action potential (He et al. 2000).

In addition, around 75 % of the ET-1-evoked ECTs were able to trigger spontaneous premature action potentials. The other agonists had a lower propensity to cause spontaneous activity and only 25 % of their ECTs were accompanied by premature action potentials while 75 % represented subthreshold DADs. Thus, despite the highest increase in the Ca2+ responses during application of the β-adrenergic agonist, it failed to generate substantial numbers of ECTs.

In addition, we found further supporting evidence for a mechanistical difference between the digoxin and ET-1-induced ECTs when analysing the time interval between the preceding electrically induced Ca2+ signal and the peak of subsequenct ECTs (Fig. 1C). ECTs seem to occur significantly earlier in the presence of digoxin than when cells were stimulated with ET-1. The reason for that is still unclear. We might hypothesis that in the presence of digoxin, spontaneous Ca2+ release is purely triggered by RyRs and thus the shorter time interval reflected a shorter functional refractoriness of the SR after the preceding Ca2+ release event. In contrast, the longer time interval in the presence of ET-1 might reflect a different activation mechanism involving InsP3Rs. This notion is supported by the fact that in the presence of digoxin, we found predominantly single ECTs following the action potential-evoked Ca2+ transient while in the presence of ET-1, a much larger proportion of multiple ECTs occurred (see Fig. 1Cd). We interpret the multiplicity of ECTs upon ET-1 stimulation as being the result of an InsP3 production that sensitises the RyRs to enter the spontaneous Ca2+ release cycle more frequently.

Subthreshold ECTs in individual myocytes by themselves contribute to the generation of microheterogeneities in the distribution of excitability and thus may add to an increase in the likelihood of re-entry and fibrillation (Nattel et al. 2000). Nevertheless these effects will remain rather local, probably even restricted to the single cell, because of the purely electrotonic propagation and the associated damping of the signal by the three dimensional structure of the cardiac tissue. In contrast to that, suprathreshold DADs trigger action potentials that can spread into larger proportions of the atrial tissue. Consequently, premature action potentials may increase the likelihood of local unidirectional conduction blocks and increase the dispersion of refractoriness; both processes that enhance the occurrence of re-entrant circuits and atrial fibrillation (Nattel & Yue, 2000). It has to be mentioned here, that a single cell producing a single premature action potential is very unlikely to trigger electrical activity in many neighbouring cells. Nevertheless, such changes of the electrical behaviour in response to ET-1 application will not be restricted to a single cell, rather the entire atrial tissue might be affected and thus, the likelihood of larger numbers of cells displaying electrical disturbances is increased.

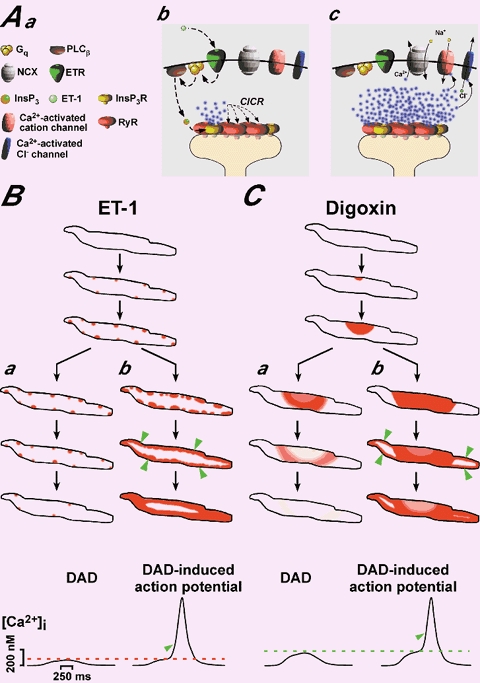

We present evidence for the direct involvement of InsP3Rs, which co-localise with junctional RyRs, in the ET-1 responses and conclude that InsP3Rs and RyRs share the same signalling microdomain (Fig. 6A). Thus, despite similar increases in the global Ca2+ responses, the spatial properties of subcellular Ca2+ release determined the arrhythmogenicity of agonist application. Consequently, the arrhythmogenicity of particular agonists that act on the heart cannot simply be judged on their ability to modulate cardiac ec-coupling in general either by Ca2+ loading of the cells or sensitisation of the Ca2+ release process itself.

Figure 6. Activation of Ca2+-dependent membrane currents and the relationship between subcellular Ca2+ release patterns, DADs and DAD-induced action potentials.

A depicts a model of how InsP3Rs impact on cardiac ec-coupling, Ca2+ signalling and membrane depolarisation. Aa introduces the symbols used in Ab and Ac. As depicted in Fig. 5Ac, InsP3Rs and RyRs share the same peripheral signalling microdomain in the junction between plasma membrane and SR (Ab). Activation of ET-1 receptors mobilises InsP3 (Ab) that stimulates InsP3Rs to release Ca2+, which then activates RyRs opening via CICR (Ab) and evokes depolarising membrane currents (Ac). B and C represent schematic diagrams for the subcellular pattern of Ca2+ release during subthreshold DADs (Aa for ET-1 and Ba for digoxin) and supratheshold premature action potentials induced by ET-1 (Ab) and digoxin (Bb). The black lines illustrate the plasma membrane of rat atrial myocytes and the intensity of the red shading indicates the Ca2+ concentration. The ET-1 induces subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks that either evoke a DAD (Aa) or they are recruited to produce a larger Ca2+ elevation and the resulting depolarisation reaches threshold for triggering an action potential (Ab). Digoxin acts differently by setting up Ca2+ waves that are either confined in their propagation (Ba) and generate a subthreshold DAD (Ba) or they spread further throughout the cell (Bb) to trigger a DAD-induced action potential (Bb; threshold for digoxin indicated by the dashed green line). In both cases, the transition from a subthreshold to a suprathreshold Ca2+ signal is clearly indicated by the occurrence of the typical Ca2+ ‘ring’ (marked by the green arrowheads).

The ability of ET-1- and digoxin-induced diastolic ECTs to trigger premature action potentials results from the activation of Ca2+-sensitive membrane currents, such as Ca2+-dependent Cl− or unspecific cation currents (Lederer & Tsien, 1976) and forwardmode Na+-Ca2+ exchange (Lipp & Pott, 1988; Fig. 6A). In principle, these currents only sense the subsarcolemmal Ca2+ concentration. Thus, Ca2+ signals confined to the sub-plasma membrane region, such as observed for ET-1 and InsP3 BM (Fig. 5; see also cartoon in Fig. 6), effectively generate substantial depolarising currents for relatively small increases in the global Ca2+. In accordance with that, we observed a lower global Ca2+ threshold concentration for action potential generation in the presence of ET-1 and InsP3 BM than for the digoxin application (Fig. 5C; see also cartoon in Fig. 6C). It is important to note here that although we did not monitor subcellular Ca2+ signals and changes of the membrane potential simultaneously for most of the cells (but see Fig. 2C), we are confident that the majority of action potential-induced ECTs represented DADs rather than EADs. Here, we define EADs as premature depolarisations that were clearly superimposed onto the shoulder of the rat atrial action potential. Although we were able to record EADs during our electrophysiological experiments, less than 2 % of all after-depolarisations were identified as EADs (data not shown). In addition, we are able to distinguish EADs from DADs based on the particular recruitment of Ca2+ sparks. The highly synchronised activation of Ca2+ sparks (via the reactivating L-type Ca2+ channels) during EADs is contrasted by the rather slow and gradual build up of the spark frequency observed during DADs. DADs only cause synchronised Ca2+ spark recruitment when they successfully triggered a premature action potential (see Fig. 2). Thus DADs and EADs could be distinguished temporally on membrane potential recordings and spatially on confocal Ca2+ recordings.

Many agents including ET-1, angiotensin II and catecholamines have been implicated in the generation of atrial arrhythmia and fibrillation without explanations for their cellular effects (Du et al. 1995; Woodcock et al. 1998). Although these stimuli all activate the Gq-PLC signalling pathway and cause generation of InsP3, the role of InsP3Rs in cardiac myocytes is controversial, with suggestions that they play only a minor role during cardiac Ca2+ signalling or have a solely organelle specific function (Marks, 2000). In contrast, several laboratories have suggested a direct involvement of InsP3 production in various heart pathologies. For example, the involvement of InsP3Rs in inflammatory cardiac diseases accompanied by arrhythmia was suggested recently by Felzen and colleagues (Felzen et al. 1998). They used the PLC inhibitor U73122 and the InsP3R antagonist heparin to block the InsP3 limb of the fas-mediated response to lymphocyte-myocyte interaction. In addition, Woodcock and colleagues demonstrated significant InsP3 production following ischaemic periods that was associated with the occurrence of cardiac arrhythmia (Du et al. 1998). They also reported that various strategies that either blocked InsP3 production directly or depleted the plasma membrane pool of the InsP3-precursor phosphatidyl-4,5-bisphosphate suppressed the ischaemia-induced arrhythmias (Du et al. 1998). Furthermore, ischaemic insults substantially increase the production of InsP3 during α-adrenergic application increasing the likelihood of InsP3 signalling during such stresses (Woodcock et al. 1995). In the present study, we used isolated cardiac myocytes from healthy animals and possible periods of ischaemia during cell isolation were minimised and where unavoidable kept well below 2 min in total. Despite these precautions, we can, of course, not rule out absolutely that the cells suffered a period of ischaemia that somehow ‘primed’ them for a more substantial InsP3 production during ET-1 application. However, the robust effects of InsP3 BM on atrial myocytes indicates that these cells display a functional response to InsP3 unrelated to any effects that ischaemia may have on hormone-induced InsP3 production.

It was interesting to find substantial increases in the amplitudes of electrically evoked Ca2+ responses of rat atrial myocytes during digoxin application, since the rat heart is well known for its reduced sensitivity towards cardiac glycosides (Levi et al. 1994). The major reason for this relative insensitivity is most likely due to the reduced expression of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger found in rat heart (for example see Sham et al. 1995), the Ca2+ entry pathway that is activated upon inhibition of the Na+-K+ pump. Indeed, in control experiments we found that digoxin concentrations that caused robust responses in atrial cells, failed to induce substantial Ca2+ transient increases and ECTs in ventricular cells (data not shown). At present, we do not fully understand these differences between atrial and ventricular cells and between species. However, our data hint to the possibility that similar stimuli can cause differential modulation of Ca2+ signalling. This is likely to be brought about by variations in ratios of homeostatic mechanisms such as Na+-Ca2+ exchange vs. Na+-K+ pump.

The concentrations of ET-1 used in the present study exceed reported apparent dissociation constant KDs for ET-1 binding to its receptors (low nanomolar values for ET-A and ET-B receptors; for a review see Golfman et al. 1991). Binding of ET-1 to its receptors has been described as ‘quasi’ irreversible (at least for the duration of even our longest experiments, see Golfman et al. 1991). Thus, for experiments using saturating ET-1 concentrations ([ET-1] >15-20 nm) the actual concentration will not alter steady-state occupancy of the receptors, instead it only affects the apparent association rate. The more rapid onset of substantial ET-1 effects has recently been described for increased concentrations ([ET-1] >10 nm; Talukder et al. 2001). Therefore, the high ET-1 concentrations used here, will ensure rapid occupancy of all the receptors and thus permits us to investigate effects of receptor binding on cellular Ca2+ signalling in the limited time for confocal microscopy. In addition, we are confident that even those high ET-1 concentrations do not cause substantial unspecific effects since 2-APB was able to specifically inhibit the arrhythmogenic actions of ET-1.

It is unlikely that cardiac myocytes would express InsP3Rs if they were solely involved in pathological responses. In keeping with this, our study clearly demonstrates a function for InsP3 in cardiac physiology. The positive inotropy observed during activation of InsP3Rs could be considered as a beneficial result from PLC activation. Although we observed that the inotropy and ECTs developed concurrently, it may be possible by titrating the concentration of stimulus to provoke the positive response without the pathological Ca2+ release activity.

In summary, we have demonstrated that expression of functional InsP3Rs in the same subsarcolemmal signalling microdomain as RyRs underlies their ability and potency to modulate cardiac ec-coupling. Direct activation of the InsP3Rs with a membrane-permeable InsP3 derivative, or their inhibition using 2APB, indicates that they can significantly contribute to the physiology (increases in the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ signals) and pathophysiology (arrhythmogenicity) of agonist-stimulated atrial cardiomyocytes. The proximity between these two Ca2+ release channels, allows the InsP3 signalling cassette to modulate ec-coupling in a way that one can almost speak of two parallel stimulation-contraction coupling mechanisms co-existing in cardiac muscle, the pharmaco- contraction and the excitation-contraction coupling, with both signalling cassettes converging on the RyRs.

Apart from the physiological occurrence of InsP3Rs in normal atrial tissue, several reports pointed out a characteristic up-regulation of InsP3 mRNA in hearts from hypertrophy and end-stage heart failure patients, while in parallel RyR mRNA was down-regulated (Marks, 2000). Furthermore, more than 50 % of those patients suffer initially from atrial arrhythmia and only later from ventricular arrhythmia, which in the light of our findings, might, at least in part, be explained by the changes of the InsP3R/RyR expression ratio. In addition to that, InsP3R expression also significantly increases during aging in humans (Go et al. 1995; Marks, 2000), a development that is again paralleled by an increase in the propensity to acquire particular forms of atrial arrhythmia, including fibrillation (Ezekowitz, 1999). Despite all this, it has to be pointed out here, that cardiac arrhythmia represents a multifactorial process. Many different mechanisms contribute to the occurrence of such arrhythmia, including the mechanisms reported here but also an altered gene expression for a range of membrane currents (Keating & Sanguinetti, 2001). Nevertheless, our current study shows, that the InsP3 signalling cassette might provide a novel target for the pharmacological management of atrial arrhythmias. However, further studies, especially on human preparations are necessary to refine our findings on the rat atrial myocytes and establish InsP3 as a putative key arrhythmogenic agent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the MRC (Grant no: G9808149) and the BBSRC. M.D.B. is a Royal Society University Fellow, L.M. is a MRC student and M.L. was supported by the Paavo Nurmi Foundation and by The Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research.

REFERENCES

- Berlin JR, Cannell MB, Lederer WJ. Cellular origin of the transient inward current in cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 1989;65:115–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad LM, Braun FJ, Lievremont JP, Bird GSJ, Kurosaki T, Putney JW. Role of the phospholipase C-inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate pathway in calcium release-activated calcium current and capacitative calcium entry. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:15945–15952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert G. Excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac cells. Cardiovascular Research. 1992;26:923–932. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.10.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XJ, Anderson KE, Jacobsen A, Woodcock EA, Dart AM. Suppression of ventricular arrhythmias during ischemia-reperfusion by agents inhibiting Ins(1,4,5)P3 release. Circulation. 1995;91:2712–2716. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.11.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezekowitz MD. Atrial fibrillation: The epidemic of the new millennium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;13:537–538. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felzen B, Shilkrut S, Less H, Sarapov I, Maor G, Coleman R, Robinson RB, Berke G, Binah O. Fas (CD95/Apo-1)-mediated damage to ventricular myocytes induced by cytotoxic T lymphocytes from perforin-deficient mice: a major role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphoshpate. Circulation Research. 1998;82:438–450. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.4.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozzard HA. Afterdepolarizations and triggered activity. Basic Research in Cardiology. 1992;87:105–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72477-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go LO, Moschella MC, Watras J, Handa KK, Fyfe BS, Marks AR. Differential regulation of two types of intracellular calcium release channels during end-stage heart failure. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95:888–894. doi: 10.1172/JCI117739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golfman LS, Hata T, Beamish RE, Dhalla NS. Role of endothelin in heart function in health and disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 1991;9:635–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorza L, Schiaffino S, Volpe P. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in heart evidence for its concentration in purkinje myocytes of the conduction system. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;121:345–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JQ, Pi Y, Walker JW, Kamp TJ. ET-1 and photoreleased diacylglycerol increase L-type Ca2+ current by activation of protein kinase C in rat ventricular myocytes. Journal Physiology. 2000;524:807–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüser J, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Calcium gradients during excitation-contraction coupling in cat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:541–651. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 2001;104:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockskämper J, Sheehan KA, Bare DJ, Lipsius SL, Mignery GA, Blatter LA. Activation and propagation of Ca2+ release during excitation-contraction coupling in atrial myocytes. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:2590–2605. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer WJ, Tsien RW. Transient inward current underlying arrhythmogenic effects of cardiotonic steroids in Purkinje fibers. Journal of Physiology. 1976;263:73–100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi AJ, Boyett MR, Lee CO. The cellular action of digitalis glycosides on the heart. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 1994;62:1–54. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Pott L. Transient inward current in guinea-pig atrial myocytes reflects a change of sodium-calcium exchange current. Journal of Physiology. 1988;397:601–630. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Laine M, Tovey SC, Burrell KM, Berridge MJ, Li W, Bootman MD. Functional IP3 receptors that may modulate excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Current Biology. 2000;10:939–942. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry SJ, Williams AJ. Digoxin activates sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channels: a possible role in cardiac inotropy. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;108:1043–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. Predetermined recruitment of calcium release sites underlies excitation-contraction coupling in rat atrial myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 2001;530:417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0417k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AR. Cardiac intracellular calcium release channels: role in heart failure. Circulation Research. 2000;87:8–11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3 -induced Ca2+ release. Journal Biochemistry-Tokyo. 1997;122:498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschella MC, Marks AR. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor expression in cardiac myocytes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120:1137–1146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S, Li D, Yue L. Basic mechanisms of atrial fibrillation-very new insights into very old ideas. Annual Review in Physiology. 2000;62:51–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez PJ, Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Mignery GA. Identification and functional reconstitution of the type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor from ventricular cardiac myocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:23961–23969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Miyauchi T, Kobayashi M, Yamagushi I, Goto K, Sugishita Y. Inhibition of myocardial endothelin pathway improves long-term survival in heart failure. Nature. 1996;384:353–355. doi: 10.1038/384353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sham JSK, Hatem SN, Morad M. Species-differences in the activity of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Journal of Physiology. 1995;488:623–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talukder MAH, Norota I, Sakurai K, Endoh M. Inotropic response of rabbit ventricular myocytes to endothelin-1: difference from isolated papillary muscles. American Journal of Physiology – Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;281:H596–605. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Tovey SC, Collins TJ, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. A comparison of fluorescent Ca2+ indicator properties and their use in measuring elementary and global Ca2+ signals. Cell Calcium. 2000;28:213–223. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock EA, Matkovich SJ, Binah O. Ins(1,4,5)P3 and cardiac function. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;40:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock EA, Suss MB, Anderson KE. Inositol phosphate release and metabolism in rat left atria. Circulation Research. 1995;76:252–260. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]