Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I has an important role in myogenesis but its developmental regulation in skeletal muscle before birth remains unknown. In other tissues, cortisol modulates IGF gene expression and is responsible for many of the prepartum maturational changes essential for neonatal survival. Hence, using RNase protection assays and ovine riboprobes, expression of the IGF-I and growth hormone receptor (GHR) genes was examined in ovine skeletal muscle during late gestation and after experimental manipulation of fetal plasma cortisol levels by fetal adrenalectomy and exogenous cortisol infusion. Muscle IGF-I, but not GHR, mRNA abundance decreased with increasing gestational age in parallel with the prepartum rise in plasma cortisol. Abolition of this cortisol surge by fetal adrenalectomy prevented the prepartum fall in muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance. Conversely, raising cortisol levels by exogenous infusion earlier in gestation prematurely lowered muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance but had no effect on GHR mRNA. When all data were combined, plasma cortisol and muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance were inversely correlated in individual fetuses. Cortisol is, therefore, a developmental regulator of IGF-I gene expression and is responsible for suppressing expression of this gene in ovine skeletal muscle near term. These observations have important implications for muscle development both before and after birth, particularly during conditions which alter intrauterine cortisol exposure.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I promotes growth and development of skeletal muscle both before and after birth (Florini et al. 1996). In vitro studies have shown that IGF-I stimulates proliferation, differentiation and hypertrophy of myogenic cells and cell lines (Florini & Ewton, 1992). In vivo, disruption of the IGF-I gene in mice leads to muscular dystrophy and to abnormalities in myofibrillar organization in specific skeletal muscles, such as the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, which prove fatal at birth (Liu et al. 1993; Powell-Braxton et al. 1993). Conversely, over-expression of IGF-I during intrauterine development leads to an increased muscle mass and myofibre hypertrophy, even when over-expression is confined specifically to muscle (Mathews et al. 1988; Coleman et al. 1995). Local production of IGF-I therefore appears to have an important role in myogenesis during intrauterine development. However, relatively little is known about the control of IGF-I gene expression in skeletal muscle before birth.

By mid gestation, expression of the IGF-I gene can be detected in fetal skeletal muscle in a number of species including the rat, pig, sheep and human (Han et al. 1988; Dickson et al. 1991; Lee et al. 1993; Edmondson et al. 1995). Expression of this gene in skeletal muscle in utero is higher than in many other fetal tissues including the liver until close to term when the prepartum maturational changes in expression begin to occur (Dickson et al. 1991; Lee et al. 1993; Edmondson et al. 1995; Kind et al. 1995). Fetal skeletal muscle also expresses the growth hormone receptor (GHR) gene (Lee et al. 1993; Adams, 1995; Edmondson et al. 1995) although growth hormone (GH) appears to have little effect on fetal plasma IGF-I levels or intrauterine growth despite high GH levels in utero (Gluckman, 1979; Fowden, 1995). In ovine liver, there are ontogenic increases in GHR and IGF-I mRNA abundances during late gestation which are dependent on the rise in fetal cortisol concentrations towards term (Li et al. 1996). This cortisol surge is responsible for inducing many of the maturational changes essential for neonatal survival and activates the GH dependent production of IGF-I in the liver in preparation for extrauterine life (Fowden et al. 1998a). In skeletal muscle, there is a decrease in IGF-I, but not GHR, mRNA abundance between mid and late gestation in pigs and sheep (Dickson et al. 1991; Lee et al. 1993; Brameld et al. 2000). In addition, recent studies have shown that IGF-I mRNA abundance in ovine skeletal muscle can be reduced by infusion of cortisol for 5 days before delivery at 130 days of gestation (Forhead et al. 2002). However, nothing is known about the effects of cortisol earlier in gestation or in the period just before delivery when fetal cortisol concentrations are increasing most rapidly. Hence, in the present study, expression of the GHR and IGF-I genes were examined in ovine skeletal muscle during the last 40-45 days of gestation and after experimental manipulation of the fetal cortisol level.

METHODS

Animals

A total 24 Welsh Mountain ewes carrying 37 fetuses of known gestational age were used in this investigation. All but seven of the fetuses studied were twins. The ewes were housed in individual pens and fed concentrates (200 g day−1; H. & G. Beart, Stowbridge, King's Lynn, UK) and hay ad libitum. Food but not water was withheld for 18-24 h before surgery. All procedures were approved and licensed by the Home Office of the UK government under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Surgical procedures

Under halothane anaesthesia (1.5 % in O2-N2O), one of the three following procedures were carried out using surgical methods already published (Li et al. 1996): (1) intravascular catheterization of the dorsal aorta and caudal vena cava of intact fetuses via the tarsal vessels (n = 16, all twin fetuses), (2) fetal adrenalectomy (AX) and intravascular catheterization (n = 6, all single fetuses) and (3) fetal AX alone (n = 4, twin fetuses; unoperated intact twins used as controls, n = 4). The precise numbers and gestational ages of the fetuses at operation are shown in Table 1 (term 145 ± 2 days).

Table 1.

Numbers and gestational ages of the intact and adrenalectomized (AX) fetuses in the experimental groups

| Gestational age (days) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | At adrenalectomy | At catheterization | At tissue collection | Total number of fetuses | Number of twins | Number of singles | |

| Intact | Uncatheterized | — | — | 100–145 | 11 | 10 | 1 |

| Catheterized | |||||||

| Saline infused | — | 97–104 | 110–114 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| — | 114–117 | 127–130 | 4 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Cortisol infused | — | 97–104 | 110–114 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| — | 114–117 | 127–130 | 4 | 4 | 0 | ||

| AX | Uncatheterized | 115–119 | — | 143–145 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Catheterized | |||||||

| Saline infused | 115–119 | 115–119 | 127–130 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Cortisol infused | 114–119 | 114–119 | 128–131 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

Experimental procedures

Blood samples of 2 ml were taken daily throughout the experimental period from all the catheterized fetuses to determine plasma cortisol concentrations and to monitor fetal well being (levels of blood pH, PO2, PCO2, glucose, lactate and haemoglobin). At least six days after catheterization, eight pairs of intact twin fetuses were infused intravenously with cortisol (2-3 mg kg−1 day−1 in 3.0 ml 0.9 % saline; EF-Cortelan, Glaxo, Greenford, Middlesex, UK, n = 8) or saline (3.0 ml day−1, 0.9 % w/v saline, n = 8) beginning between either 105 and 109 days or 123 and 125 days of gestation (Table 1). One of each pair was infused with saline while the other was infused with cortisol. Similarly, six AX fetuses were infused intravenously with either cortisol (2-3 mg kg−1 day−1 in 3 ml 0.9 % w/v saline, n = 3 single fetuses) or saline (3 ml day−1 0.9 % w/v saline, n = 3 single fetuses) beginning between 123 and 126 days of gestation (Table 1). Fetuses were randomly assigned to be saline or cortisol infused. The dose of cortisol was chosen to mimic the fetal plasma concentrations that normally occur immediately before parturition.

Tissue collection

All catheterized fetuses, irrespective of previous treatment, and 15 additional untreated intact and AX fetuses were delivered by Caesarean section under sodium pentobarbitone anaesthesia (20 mg kg−1i.v.); details of the numbers and gestational ages of the animals at delivery are given in Table 1. Blood samples were taken from all the fetuses at the time of delivery either through the indwelling catheters or by venipuncture from the umbilical artery after anaesthesia had been induced. After administration of a lethal dose of anaesthetic (200 mg kg−1 sodium pentobarbitone), 3-5 g samples of the biceps femoralis muscle were collected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80 °C. Several other tissues were also collected at this time as part of another study (not shown here). All blood samples were centrifuged immediately at 4 °C and the plasma stored at −20 °C until analysis. At delivery, no obvious adrenal remnants were found in any of the AX fetuses.

Biochemical analyses

Hormone concentrations

. Plasma concentrations of cortisol were measured by radioimmunoassay validated for use with ovine plasma as described previously (Robinson et al. 1983). The limit of detections was 1.5 ng ml−1 and the interassay coefficient of variation was 10 %.

RNase protection assays

. Total RNA was isolated from 1 g portions of frozen muscle with a guanidinium thiocyanate method and quantified by absorbance at 260 nm (absorbance of 1 = 40 μg ml−1). The integrity of the RNA samples was routinely checked by denaturing gel electrophoresis. To check the equivalence of RNA samples, total poly (A)+ content was also measured as published previously (Pell et al. 1993). A constant relationship between absorbance and poly (A)+ content was found for ovine tissues (Pell et al. 1993). This procedure was adopted because recent studies have identified numerous problems with using ‘housekeeping’ genes as RNA controls (Ivell, 1998). A rigorously optimized RNase protection assay was therefore used (White & Dauncey, 1998) with several animals (3-4) per age or treatment group (Table 1). In addition, treatment groups to be compared were run on the same gel. Furthermore, any small errors due to differences between samples will have been included in the total experimental variation as indicated by the standard errors for each group.

RNase protection assays were performed on 50 μg of total RNA using GHR and IGF-I riboprobes derived from published sequences as described previously (Dickson et al. 1991; Li et al. 1996). The GHR riboprobe protected a 138 nucleotide fragment of GHR mRNA from the intracellular domain of the receptor. Ovine IGF-I mRNA has multiple forms which have been classified as Class 1 or Class 2 transcripts depending on which of two possible 5′ leader exons (exon 1 or exon 2) is spliced to the IGF-I first coding exon 3 (Dickson et al. 1991). The IGF-I riboprobe used in this study spanned exons 2-3 and protected two fragments of 132 and 147 nucleotides derived from hybridization to the Class 1 and Class 2 IGF-I mRNA transcripts, respectively (Dickson et al. 1991). Protected fragments were separated on 6 % polyacrylamide denaturing gels and exposed to X-ray film (Kodak, Cambridge, UK). Protected bands were quantified by measuring the integrated optical density of each band with a computerized image analyser (Seescan, Cambridge, UK). A constant rectangular area of the X-ray film that included the complete mRNA signal plus background was defined. This background area was used to set zero intensity. Exposure time was adjusted so that band intensities were within the linear range of detection of the analyser. To ensure valid comparison of data from different gel runs, a control muscle mRNA sample was run on every gel. These quality controls varied by < 5 % and hence only minor adjustments, if any, were required to compare different gels.

Statistical analyses

Mean and s.e.m. values have been given throughout and statistical analyses were made according to the methods of Armitage (Armitage, 1971). Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA with Tukey's test, paired and unpaired t tests, as appropriate. Correlation was calculated by linear regression. Probabilities of < 5 % were considered significant.

RESULTS

Ontogenic changes

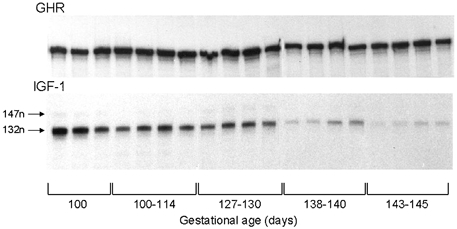

Expression of the GHR and IGF-I genes was observed in skeletal muscle at all ages studied from 100-145 days of gestation (Fig. 1). Throughout this period, the predominant form of the IGF-I mRNA was the Class 1 transcript derived from exon 1 (132 nucleotides, Fig. 1). The Class 2 transcript was detectable at the younger ages but was not quantifiable (147 nucleotides, Fig. 1). Consequently, abundance of IGF-I mRNA could only be calculated for the Class 1 protected bands.

Figure 1. Ontogeny of GHR and IGF-I gene expression in ovine fetal skeletal muscle.

Autoradiograms of RNase protection assay using the GHR and IGF-I riboprobes with 50 mg of total RNA from skeletal muscle of groups of intact fetuses aged 100-145 days of gestation. For IGF-I mRNA, protected probes gave bands at 132 nucleotides (132 n) for Class 1 transcripts and at 147 nucleotides (147 n) for Class 2 transcripts.

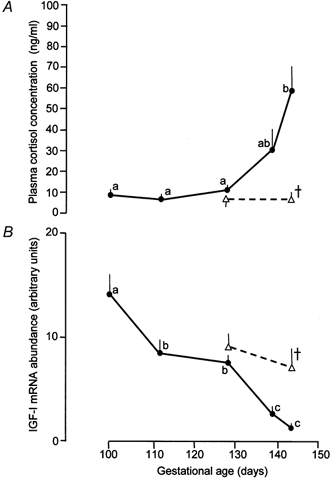

There was no apparent change in GHR mRNA levels over the period of gestation examined in the present study (Fig. 1). The mean GHR mRNA abundance in skeletal muscle at 143-145 days (7.1 ± 0.9 arbitrary units, n = 4) was not significantly different from the values observed at any of the other age ranges (P > 0.05, all cases). In contrast, abundance of muscle IGF-I mRNA decreased with increasing gestational age towards term (Fig. 1). Mean IGF-I mRNA levels fell by 90 % between 100 and 145 days of gestation but not progressively (Fig. 2B). Levels of IGF-I mRNA were highest at 100 days and then decreased to stable values between 110 and 130 days before declining again during the last 7-10 days of gestation (P < 0.01, Fig. 2). The final prepartum decline in muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance closely paralleled the normal rise in fetal plasma cortisol concentration towards term (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Changes in plasma cortisol concentration and Class 1 IGF-I mRNA abundance with gestational age.

Mean (± s.e.m.) values of plasma cortisol concentration (A) and Class 1 IGF-I mRNA abundance (B) with respect to gestational age in skeletal muscle from intact (•) and AX (▵) sheep fetuses. Values with different letters are significantly different from each other (ANOVA, P < 0.05). † Significantly different from values seen in intact fetuses at the same gestational age (P < 0.01).

The effects of manipulating the fetal cortisol concentration

Adrenalectomy

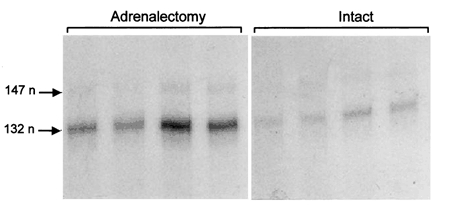

Fetal AX prevented the prepartum cortisol surge (Fig. 2A) and abolished the normal decline in muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance towards term (Fig. 3). At 143-145 days, the mean muscle IGF-I mRNA level in the AX fetuses was significantly higher than that in intact fetuses (P < 0.01) and was similar to the values observed in the intact and AX fetuses at 127-131 days (Fig. 2B). At 143-145 days, fetal AX had no effect on muscle GHR mRNA: the mean value in the AX fetuses (6.7 ± 0.2 arbitrary units, n = 4) was not significantly different from that seen in the intact controls at term (7.1 ± 0.9 arbitrary units, n = 4, P > 0.05). Muscle GHR mRNA abundance was not measured in the younger AX fetuses.

Figure 3. Effect of adrenalectomy on IGF-I gene expression in ovine fetal skeletal muscle at term.

Autoradiograms of Class 1 and Class 2 IGF-I mRNA in skeletal muscle from AX and intact sheep fetuses at 143-145 days of gestation.

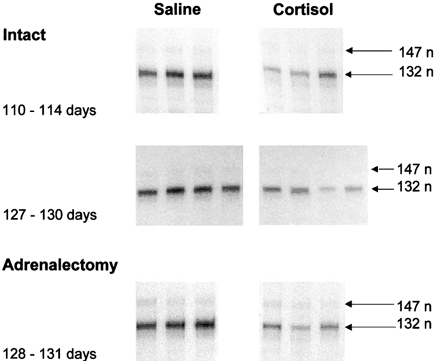

Fetal cortisol infusion

Cortisol infusion into the fetus for 5 days lowered muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance in intact fetuses at both 110-114 days and 127-130 days and in AX fetuses at 127-131 days (Fig. 4). Plasma cortisol levels in the cortisol infused fetuses were significantly higher than those in the corresponding groups of saline infused fetuses (P < 0.05, Table 2), and were similar to those observed in the intact fetuses at 143-145 days (Fig. 2A). At 127-130 days, plasma cortisol levels were similar in the intact and AX fetuses (Table 2) as fetal cortisol is derived primarily from the maternal circulation at this gestational age (Hennessy et al. 1982). In both the intact and AX fetuses, mean muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance in the cortisol infused animals was significantly less than in the corresponding group of saline infused controls (P < 0.05, Table 2) and was similar to the value seen in the intact fetuses near term (Fig. 2B). Cortisol infusion had no effect on muscle GHR mRNA abundance in the intact fetuses at 127-130 days: mean values in the cortisol and saline infused fetuses were 6.7 ± 0.8 and 7.2 ± 0.8, respectively (arbitrary units, n = 4 in each group, P > 0.05). Since muscle GHR mRNA abundance was unaffected either by AX at 143-145 days or by cortisol infusion at 127-130 days, GHR gene expression was not analysed in the other groups of cortisol infused fetuses.

Figure 4. Effect of cortisol infusion on IGF-I gene expression in ovine fetal skeletal muscle.

Autoradiograms of Class 1 and Class 2 IGF-I mRNA transcripts in skeletal muscle from intact and AX fetuses infused with saline or cortisol for 5 days before delivery at either 110-114 days or 127-131 days. Details of the dose of cortisol are given in the text.

Table 2.

Mean (± s.e.m.) values of plasma cortisol and Class 1 IGF-I mRNA abundance in intact and adrenalectomized fetal sheep infused with saline or cortisol for 5 days before delivery at 110–114 days or 127–131 days

| Gestational age at delivery (days) | Plasma cortisol (ng ml−1) | Class I IGF-I mRNA (arbitrary units) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline infused | Cortisol infused | Saline infused | Cortisol infused | ||

| Intact | 110–114 | 7.3 ± 1.4 (4) | 35.2 ± 6.8 † (4) | 8.70 ± 0.79 (4) | 3.58 ± 1.05 † (4) |

| 127–130 | 11.4 ± 1.3 (4) | 63.5 ± 11.8 † (4) | 7.62 ± 0.47 (4) | 1.40 ± 0.42 † (4) | |

| Adrenalectomy | 128–131 | 6.9 ± 1.3 (3) | 47.1 ± 12.3 † (3) | 9.49 ± 1.03 (3) | 2.10 ± 1.07 † (3) |

Number of animals in parentheses.

Significantly different from the value in the corresponding saline infused group (P < 0.05).

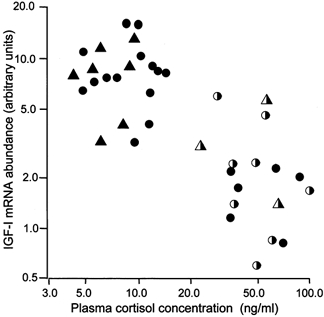

Relationship between fetal plasma cortisol and muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance

Since all the groups of fetuses with elevated plasma cortisol levels, whether exogenous or endogenous, had lower muscle IGF-I mRNA levels than those with low plasma cortisol values, the relationship with fetal plasma cortisol was examined further. When the data from all the fetuses were combined, irrespective of treatment or age, there was a significant inverse correlation between log plasma cortisol and log muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance in the individual animals (r = −0.761, n = 38, P < 0.001, Fig. 5). There was also a significant inverse correlation between these parameters in the control animals alone (r = −0.805, n = 20, P < 0.001, Fig. 5)

Figure 5. The relationship between the plasma cortisol concentration and skeletal muscle Class 1 IGF mRNA abundance in individual sheep fetuses.

•,intact control fetuses,unoperated and saline infusion;, cortisol infused intact fetuses; ▴, adrenalectomized fetuses;

, cortisol infused adrenalectomized fetuses. All animals, log10y = 1.479-[0.688 log10x], n = 37, r = −0.761, P < 0.001; control animals alone, log10y = 1.580 − [0.760 log10x], n = 19, r = −0.805, P < 0.001).

, cortisol infused adrenalectomized fetuses. All animals, log10y = 1.479-[0.688 log10x], n = 37, r = −0.761, P < 0.001; control animals alone, log10y = 1.580 − [0.760 log10x], n = 19, r = −0.805, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The results demonstrate that there are developmental changes in gene expression of IGF-I, but not GHR in ovine skeletal muscle during the last 40-45 days of gestation. In common with the adult animal (Saunders et al. 1991; Pell et al. 1993), the class 1 transcript was the predominant form of IGF-I mRNA in ovine skeletal muscle before birth. Abundance of this transcript fell in fetal biceps femoralis muscle between 100 and 110 days of gestation and then again between 130 days and term. The earlier decline in muscle IGF-I gene expression occurred at the period of gestation when formation of the secondary myotubes is nearing completion (Ashmore et al. 1972; Maier et al. 1992). High levels of muscle IGF-I may therefore be associated with ovine myogenesis as appears to occur in the human infant (Tanaka et al. 1995; Han et al. 1988). Certainly, expression of the IGF-II gene is known to peak in ovine skeletal muscle around 90 to 100 days of gestation when the secondary fibres are forming most rapidly (Dauncey & Gilmour, 1996). The later decline in fetal muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance after 130 days occurred at a time in gestation associated with muscle differentiation (Walker & Luff, 1995). Close to term, there are changes in the contractile and oxidative properties of ovine skeletal muscle fibres which are accompanied by a switch in heavy chain myosin expression from the fetal to the adult isoforms (Finkelstein et al. 1992; Maier et al. 1992; Schiaffino & Reggiani, 1994). The current in vivo observations that developmental changes in muscle IGF-I gene expression coincide with major phases of myofibre proliferation and differentiation in utero are consistent with the known actions of IGF-I on cultured myogenic cells in vitro (Florini & Ewton 1992).

The final prepartum decrease in muscle IGF-I gene expression also occurred in parallel with the normal rise in fetal plasma cortisol towards term. When this cortisol surge was abolished by fetal adrenalectomy, the prepartum decline in muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance was prevented. Conversely, raising cortisol levels to prepartum values, at times when fetal plasma concentrations are normally low, lowered muscle IGF-I mRNA levels in both intact and AX fetuses. Cortisol, therefore, appears to downregulate IGF-I gene expression in ovine skeletal muscle during late fetal development. These findings confirm our previous study (Forhead et al. 2002) and extend it to show that muscle IGF-I gene expression is responsive to cortisol throughout the last 40 days of fetal development. Since cortisol has also been shown to suppress muscle IGF-II gene expression before birth (Li et al. 1993), the current study suggests that the prepartum cortisol surge is responsible for overall downregulation of local IGF production in skeletal muscle before delivery. The correlation observed in the present study between the plasma cortisol concentration in utero and muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance also indicates that cortisol is a natural developmental regulator of IGF-I gene expression in ovine skeletal muscle during late gestation. Using the same probes and experimental protocol, cortisol has been shown to have a similar regulatory role in the fetal liver but whereas cortisol downregulates muscle IGF-I gene expression, it upregulates hepatic IGF-I mRNA abundance (Li et al. 1996; Forhead et al. 2000). These opposing actions of cortisol on hepatic and muscle IGF-I gene expression may explain, in part, why fetal plasma IGF-I concentrations are unaffected by fetal cortisol infusion or advancing age between 110 days and term (Li et al. 1996). The effects of cortisol on IGF-I gene expression in utero are therefore tissue specific and appear to switch the somatotrophic axis from paracrine IGF-I synthesis to the endocrine production of hepatic IGF-I characteristic of the postnatal animal.

The mechanism by which cortisol reduces muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance remains unclear. There may be changes in gene transcription, mRNA stability or nucleocytoplasmic mRNA transport. Cortisol is unlikely to act directly on the IGF-I gene as the published genomic sequence, which includes extensive regions 5′ to known transcriptional initiation points for the two transcript classes, does not contain recognizable glucocorticoid response elements (Dickson et al. 1991). Its actions may therefore be mediated indirectly through other transcription factors or cortisol dependent endocrine changes such as the prepartum increase in plasma triiodothyronine (T3; Fowden et al. 1998a). Thyroid hormones are known to have an important role in muscle growth and differentiation prenatally (Finkelstein et al. 1991) and have been shown to alter muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance during late fetal development (Forhead et al. 2002). Changes in thyroid hormone status and tissue thyroid hormone receptors may also partially explain the fall in muscle IGF-I gene expression observed between 100 and 110 days of gestation (Polk et al. 1989).

Nutrient availability in utero influences IGF status during late gestation (Owens 1991; Fowden 1995). Muscle IGF-I gene expression is reduced in fetal sheep undernourished by placental insufficiency or cord occlusion (Kind et al. 1995; Green et al. 2000), and is increased in fetal pigs made hyperglycaemic by maternal diabetes (Ramsey et al. 1994). Restricting maternal dietary intake early in pregnancy has also been shown to lower IGF-I gene expression in ovine skeletal muscle near term (Brameld et al. 2000). In part, these effects of nutrient availability may be due to changes in the fetal insulin level (Owens, 1991; Fowden, 1995). Insulin is known to regulate IGF production and has been shown to enhance IGF-I synthesis in utero, even in hypoglycaemic conditions (Fowden, 1995; Oliver et al. 1996). Fetal glucose and insulin levels were not measured in the present study, but were unaltered by gestational age or cortisol infusion in previous studies of the sheep fetus (Fowden et al. 1996; Aldoretta et al. 1998; Fowden et al. 1998b). Changes in fetal glucose and/or insulin concentrations are, therefore, unlikely to account for the reductions in muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance observed in the present study.

Postnatally, muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance is affected by GH independent and GH dependent mechanisms (Florini et al. 1996). Growth hormone increased muscle IGF-I mRNA abundance in adult rats but not sheep or pigs (Pell et al. 1993; Brameld et al. 1996; Lemmey et al. 1997). However, in newborn pigs, muscle IGF-I gene expression is responsive to GH (Lewis et al. 2000). Although the Class 1 IGF-I mRNA transcript appears to be GH insensitive in adult sheep (Saunders et al. 1991; Pell et al. 1993), the cortisol-induced upregulation of this transcript in fetal ovine liver has been attributed, at least in part, to the concomitant increase in GHR gene expression (Li et al. 1999). No changes in muscle GHR mRNA abundance were observed either during late gestation or in response to cortisol infusion in the present study. However, decreased activation of muscle GHR may contribute to the fall in muscle Class I IGF-I mRNA abundance observed both between 100 and 110 days and towards term, as GH levels fall to a nadir between 100 and 110 days and also decrease rapidly from high values during the last 2-3 days before delivery in the sheep fetus (Gluckman et al. 1979).

The absence of any effects of endogenous or exogenous cortisol on muscle GHR gene expression in the present study was not entirely unexpected. In previous studies, no consistent changes in GHR gene expression were observed in porcine or ovine skeletal muscle with the natural increases in fetal plasma cortisol that occur between mid and late gestation and during the perinatal period (Dickson et al. 1991; Lee et al. 1993; Adams, 1995). In addition, no glucocorticoid response elements have been identified in the promoter of the GHR transcript predominantly expressed in ovine skeletal muscle (Adams, 1995). However, in fetal ovine liver, this GHR transcript is upregulated by cortisol, probably via the concomitant change in fetal plasma T3 (Li et al. 1999). Hence, the effects of cortisol on ovine GHR gene expression, like those on the ovine IGF-I gene, are tissue specific during late fetal development. Cortisol, therefore, suppresses IGF-I gene expression and has no effect on GHR mRNA abundance in fetal skeletal muscle but upregulates expression of both genes in fetal liver.

Suppression of muscle IGF-I gene expression by cortisol has important implications for muscle development. IGF-I is known to regulate myogenic gene expression, metabolism and excitability of skeletal muscle (Florini & Ewton, 1992; Florini et al. 1996; Boyle et al. 1998). It may also affect expression of the myosin isoforms (Dauncey & Gilmour, 1996). The metabolic actions of IGF-I in muscle are anabolic and are associated with changes in the activity of key biosynthetic and oxidative enzymes in skeletal muscle (Dauncey & Gilmour, 1996; McKoy et al. 1998). Since ovine myogenesis appears to be largely complete by the end of gestation (Ashmore et al. 1972), downregulation of muscle IGF-I gene expression is more likely to affect the size and transformation of fibre types than the number of myofibres per se. However, immunohistochemical studies of ovine skeletal muscle have suggested that a tertiary phase of myotubule proliferation may begin around 130 days of gestation (Maier et al. 1992) at a time when muscle IGF-I gene expression starts to decline with the prepartum increase in fetal plasma cortisol. Changes in IGF-I gene expression in utero may therefore lead to differences in the contractility and metabolic properties of muscles postnatally with consequences for muscle strength and sensitivity to circulating hormones such as insulin, in later life. However, the extent to which changes in muscle IGF-I gene expression result in altered IGF-I protein availability remains to be determined.

The actions of cortisol on muscle IGF-I gene expression are in keeping with the other known maturational effects of cortisol in utero (Fowden et al. 1998a). At birth, ovine skeletal muscle must assume antigravity, locomotive and thermoregulatory functions for the first time. In preparation for these functional adaptations, there are changes in the metabolic and contractile characteristics of the myofibres during the immediate prepartum period (Schiaffino & Reggiani, 1994; Walker & Luff, 1995; McKoy et al. 1998). The results of this and our previous study of muscle IGF-II (Li et al. 1993) indicate that cortisol-induced downregulation of muscle IGF gene expression may have an important role in these prepartum maturational changes. Since skeletal muscle accounts for 25-35 % of fetal body weight during late gestation (Owens, 1991; Fowden, 1995), downregulation of local IGF gene expression earlier in gestation is likely to have major consequences not only for muscle development but also for fetal growth overall. Abnormalities in muscle development may therefore contribute to the growth retardation observed during adverse conditions, such as placental insufficiency and undernutrition, which are associated with a precocious increase in fetal plasma cortisol. Moreover, adaptation of skeletal muscles to their new postnatal functions may be impaired in neonates delivered prematurely before the normal prepartum increment in fetal plasma cortisol. The current findings therefore have important implications for the control of muscle development both before and after birth, and provide a potential mechanism whereby the postnatal structure and function of skeletal muscle may be programmed in utero (Fowden et al. 1998a).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Paul Hughes, Malcolm Bloomfied and Ted Saunders for technical assistance; Sue Nicholls and Vicky Johnson for care of the animals; Dee Hughes for the photography and Nicola Allanson for typing the manuscript. The work was funded, in part, by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

REFERENCES

- Adams TE. Differential expression of growth hormone receptor messenger RNA from a second promoter. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1995;108:23–33. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)92575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldoretta PW, Carver TD, Hay WW. Maturation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in fetal sheep. Biology of the Neonate. 1998;73:375–386. doi: 10.1159/000014000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage P. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. Oxford: Blackwells; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore CR, Robinson DW, Rattray P, Doerr I. Biphasic development of muscle fibres in the fetal lamb. Experimental Neurology. 1972;37:241–255. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(72)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DW, Denne SC, Moorehead H, Lee W-H, Bowsher RR, Lichty EA. Effect of rhIGF-I on whole fetal and fetal skeletal muscle protein metabolism in sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:E1082–1091. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.6.E1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brameld JM, Atkinson JL, Saunders JC, Pell JM, Buttery PJ, Gilmour RS. Effects of growth hormone administration and dietary protein intake on insulin-like growth factor I and growth hormone receptor mRNA expression in porcine liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Journal of Animal Science. 1996;74:1832–1841. doi: 10.2527/1996.7481832x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brameld JM, Mostyn A, Dandrea J, Stephenson TJ, Dawson JM, Buttery PJ, Symonds ME. Maternal nutrition alters the expression of insulin-like growth factors in fetal sheep liver and skeletal muscle. Journal of Endocrinology. 2000;167:429–437. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1670429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman ME, DeMayo F, Yin KC, Lee HM, Geske R, Montgomery C, Schwartz RJ. Myogenic vector expression of insulin-like growth factor I stimulates muscle cell differentiation and myofiber hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:12109–12116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauncey MJ, Gilmour RS. Regulatory factors in the control of muscle development. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1996;55:543–559. doi: 10.1079/pns19960047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson MC, Saunders JC, Gilmour RS. The ovine insulin-like growth factor-I gene: characterization, expression and identification of a putative promoter. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 1991;6:17–31. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0060017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson SR, Werther GA, Russell A, Leroith D, Roberts CT, Jr, Beck F. Localization of growth hormone receptor/binding protein messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) during rat fetal development: Relationship to insulin-like growth factor-I mRNA. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4602–4609. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein DI, Andrianakis P, Lutt AR, Walker DW. Effect of thyroidectomy on development of skeletal muscle in fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:R1300–1306. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.5.R1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein DI, Andrianakis P, Luff AR, Walker DW. Developmental changes in hindlimb muscles and diaphragm of sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:R900–908. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.4.R900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florini JR, Ewton DZ. Induction of gene expression in muscle by IGFs. Growth Regulation. 1992;2:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florini JR, Ewton DZ, Coolican SA. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor system in myogenesis. Endocrine Reviews. 1996;17:481–517. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-5-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhead AJ, Li J, Gilmour SJC, Dauncey MJ, Fowden AL. Thyroid hormones and the mRNA for the growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factors in skeletal muscle of fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;282:E80–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00284.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhead AJ, Li J, Saunders JC, Dauncey MJ, Gilmour RS, Fowden AL. Control of ovine hepatic growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor I by thyroid hormones in utero. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;278:E1166–1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL. Endocrine regulation of fetal growth. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1995;7:351–363. doi: 10.1071/rd9950351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Li J, Forhead AJ. Glucocorticoids and the preparation for life after birth: are there long term consequences of the life insurance? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1998a;57:113–122. doi: 10.1079/pns19980017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Munday L, Silver M. Developmental regulation of glucogenesis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. Journal of Physiology. 1998b;508:937–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.937bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Szemere J, Hughes P, Gilmour RS, Forhead AJ. The effects of cortisol on growth rate of the sheep fetus during late gestation. Journal of Endocrinology. 1996;151:97–105. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1510097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman PD, Mueller PL, Kaplan SL, Rudolph AM, Grumbach MM. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus. I. Circulating growth hormone in mid and late gestation. Endocrinology. 1979;104:162–168. doi: 10.1210/endo-104-1-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LR, Kawagoe Y, Hill DJ, Richardson BS, Han VKM. The effect of intermittent umbilical cord occlusion on insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in preterm and near-term ovine fetuses. Journal of Endocrinology. 2000;166:565–577. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han VK, Lund PK, Lee DC, D'Ercole AJ. Expression of somatomedin/insulin-like growth factor messenger riconucleic acids in the human fetus: identification, characterization and tissue distribution. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1988;66:422–429. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-2-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy DP, Coghlan JP, Hardy KJ, Scoggins BA, Wintour EM. The origin of cortisol in the blood or fetal sheep. Journal of Endocrinology. 1982;95:71–79. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0950071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivell R. A question of faith or the philosophy of RNA controls. Journal of Endocrinology. 1998;159:197–200. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind KL, Owens JA, Robinson JS, Quinn KJ, Grant PA, Walton PE, Gilmour RS, Owens PC. Effect of restriction of placental growth expression of IGFs in fetal sheep: relationship of fetal growth, circulating IGFs and binding proteins. Journal of Endocrinology. 1995;146:23–34. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1460023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Chung CS, Simmen FA. Ontogeny of the porcine insulin-like growth factor system. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1993;93:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(93)90141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmey AB, Glassford J, Flick-Smith HC, Holly JMP, Pell JM. Differential regulation of tissue insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP)-3, IGF-1 and IGF type 1 receptor mRNA levels, and serum IGF-1 and IGFBP concentrations by growth hormone and IGF-I. Journal of Endocrinology. 1997;154:319–328. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1540319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AJ, Wester TJ, Burrin DG, Dauncey MJ. Exogenous growth hormone induces somatotrophic gene expression in neonatal liver and skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology. 2000;278:R838–844. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gilmour RS, Saunders JC, Dauncey MJ, Fowden AL. Activation of the adult mode of ovine growth hormone receptor gene expression by cortisol during late fetal development. FASEB Journal. 1999;13:545–552. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Owens JA, Owens PC, Saunders JC, Fowden AL, Gilmour RS. The ontogeny of hepatic growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor I gene expression in the sheep fetus during late gestation: developmental regulation by cortisol. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1650–1657. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Saunders JC, Gilmour RS, Silver M, Fowden AL. Insulin-like growth factor-II messenger ribonucleic acid expression in fetal tissues of the sheep during late gestation: effects of cortisol. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2083–2089. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8477658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-L, Baker J, Perkins AS, Roberson EJ, Efstatiadis A. Mice carrying null mutations of the genes encoding insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and type I IGF receptor (IGF-Ir) Cell. 1993;75:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A, McEwan JC, Dodds KG, Fischman DA, Fitzsimons RB, Harris AJ. Myosin heavy chain composition of single fibres and their origins and distribution in developing fascicles of sheep tibialis cranialis muscles. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1992;13:551–572. doi: 10.1007/BF01737997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews LS, Hammer RE, Behringer RR, D'Ercole AJ, Bell GI, Brinster RL, Palmiter RD. Growth enhancement of transgenic mice expressing human insulin-like growth factor I. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2827–2833. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-6-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKoy G, Léger M-E, Bacou F, Goldspink G. Differential expression of myosin heavy chain mRNA and protein isoforms in four functionally diverse rabbit skeletal muscles during pre- and postnatal development. Developmental Dynamics. 1998;211:193–203. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199803)211:3<193::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MH, Harding JE, Breier BH, Gluckman PD. Fetal insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-II are regulated differently by glucose or insulin in the sheep fetus. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1996;8:167–172. doi: 10.1071/rd9960167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA. Endocrine and substrate control of fetal growth: placental and maternal influence and insulin-like growth factors. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1991;3:501–517. doi: 10.1071/rd9910501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell JM, Saunders JC, Gilmour RS. Differentiation regulation of transcription initiation from insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) leader exons and of tissue IGF-I expression in response to changed growth hormone and nutritional status in sheep. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1797–1807. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.8462477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk D, Cheromcha D, Reviczky A, Fiher DA. Nuclear thyroid hormone receptors: ontogeny and effects in sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:E543–549. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.4.E543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Braxton L, Hollingshead P, Dowd M, Pitts-Meek S, Dalton D, Gillett N, Stewart TA. IGF-I is required for normal embryonic growth in mice. Genes and Development. 1993;7:2609–2617. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey TG, Wolverton CK, Steele NC. Alternation in IGF-I mRNA content of fetal swine tissues in response to maternal diabetes. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:R1391–1396. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PM, Comline RS, Fowden AL, Silver M. Adrenal cortex of fetal lambs: changes after hypoplysectomy and the effects of synacthen on cytoarchitecture and secretory activities. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology. 1983;68:15–27. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1983.sp002697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JC, Dickson MC, Pell JM, Gilmour RS. Expression of a growth hormone-responsive exon of the ovine insulin-like growth factor-I gene. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 1991;7:233–240. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0070233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Myosin isoforms in mammalian skeletal muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;77:493–501. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka O, Shinohara H, Oguni M, Yoshioka T. Ultrastructure of developing muscle in the upper limbs of human embryo and fetus. Anatomical Record. 1995;241:417–424. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092410317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DW, Luff A. Functional development of fetal limb muscles: a review of the roles of muscle activity, nerves and hormones. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1995;7:391–398. doi: 10.1071/rd9950391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P, Dauncey MJ. An enhanced method for RNase protection assays using free DNA co precipitant. Life Sciences News. 1998;1:23–25. [Google Scholar]