Abstract

The water permeability of biological membranes has been a longstanding problem in physiology, but the proteins responsible for this remained unknown until discovery of the aquaporin 1 (AQP1) water channel protein. AQP1 is selectively permeated by water driven by osmotic gradients. The atomic structure of human AQP1 has recently been defined. Each subunit of the tetramer contains an individual aqueous pore that permits single-file passage of water molecules but interrupts the hydrogen bonding needed for passage of protons. At least 10 mammalian aquaporins have been identified, and these are selectively permeated by water (aquaporins) or water plus glycerol (aquaglyceroporins). The sites of expression coincide closely with the clinical phenotypes – ranging from congenital cataracts to nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. More than 200 members of the aquaporin family have been found in plants, microbials, invertebrates and vertebrates, and their importance to the physiology of these organisms is being uncovered.

Discovery of the lipid bilayer in the 1920s provided the explanation for how cells maintain their optimal intracellular environment when bathed in an extracellular fluid of lower or higher pH or containing toxic concentrations of Ca2+ or other solutes. The discovery of ion channels, exchangers and co-transporters beginning in the 1950s provided molecular explanations for transmembrane movements of solutes. Nevertheless, it was long assumed that the transport of water is due to simple diffusion through the lipid bilayer. Observations from multiple experimental systems with high membrane water permeabilities, such as amphibian bladder and mammalian erythrocytes, suggested that the diffusion through lipid bilayers is not the only pathway for water to cross the membrane. While various explanations were proposed, no molecular water-specific transport protein was known until the discovery of AQP1 just 10 years ago (Preston et al. 1992).

It is now well agreed that diffusion and channel-mediated water movements both exist. Diffusion occurs through all biological membranes at relatively low velocity. Aquaporin water channels are found in a subset of epithelia with a 10- to 100-fold higher capacity for water permeation. Remarkably, the selectivity of aquaporin water channels is so high that even protons (H3O+) are repelled. In most tissues, diffusion is bi-directional, since water enters and is released from cells, whereas aquaporin-mediated water flow in vivo is directed by osmotic or hydraulic gradients. Chemical inhibitors of diffusion are not known, and diffusion occurs with a high Ea (Arrhenius activation energy). In contrast, most mammalian aquaporins are inhibited by mercurials, and the Ea is equivalent to diffusion of water in bulk solution (≈5 kcal mol−1).

The discovery of the aquaporins illustrates the importance of serendipity in biological research and has caused a complete shift in the paradigm for how water crosses biological membranes during epithelial fluid transport. This topic is of large importance to normal physiology as well as to the pathophysiology of multiple clinical disorders affecting humans. Aquaporins have been identified in virtually every living organism, including higher mammals, other vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, eubacteria, archebacteria, and other microbials, indicating that this newly recognized family of proteins is involved in diverse biological processes throughout the natural world.

Discovery of AQP1

The red cell Rh blood group antigens are not known to participate in water transport (Heitman & Agre, 2000), but studies of Rh led to the serendipitous discovery of the aquaporins. A biochemical technique for purification of the Rh polypeptides yielded a contaminating 28 kDa polypeptide (Agre et al. 1987). Based upon the relative insolubility of the 28 kDa protein in the detergent, N-lauroylsarcosine, a simple purification system was developed which yielded large amounts of the protein. The 28 kDa protein was shown to be highly abundant in both red cells and renal proximal tubules – tissues with the highest known water permeability (Denker et al. 1988). Moreover, the 28 kDa protein behaved as a tetrameric integral membrane protein – often a characteristic of membrane channel proteins (Smith & Agre, 1991). The N-terminal sequence of the 28 kDa polypeptide was used to clone a cDNA encoding a 269 amino acid polypeptide from an erythroid library (Preston & Agre, 1991). Analysis of the genetic database showed homologues in diverse species including microbials and plants, but their molecular functions were unknown. ‘CHIP28′ was temporarily used to describe this protein as a ‘channel-like integral protein of 28 kDa.‘

The focus of our laboratory changed dramatically on 9 October 1991, the day we discovered that the 28 kDa protein is a water channel. The protein was expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, and swelling was monitored microscopically after transfer to hypotonic buffer (Fig. 1). The very first experiments revealed dramatic explosion of oocytes expressing the 28 kDa protein when they were placed in distilled water. By adjusting the tonicity (70 mosmol l−1 was optimal) swelling could be measured for up to 3 min, permitting us to measure the water permeability accurately. Subsequent experiments revealed the low Ea, inhibition by mercurials, and lack of measurable membrane currents (Preston et al. 1992). The water permeability of the protein was confirmed by experiments with pure 28 kDa protein reconstituted into liposomes and measurement of fluorescence quenching (or light scatter) after stopped-flow transfer to hyperosmolar solutions (Zeidel et al. 1992, 1994). This technique permitted calculation of the unit permeation, pf ∼2 × 109 water molecules per subunit per second. Despite a huge capacity for water transport, we were unable to detect transport of other solutes including urea, glycerol, or even protons. We suggested ‘aquaporins’ as a functionally relevant name for CHIP28 and related proteins (Agre et al. 1993). The formal name ‘aquaporin-1′ (abbreviated AQP1) was officially adopted by the Human Genome Organization (Agre, 1997).

Figure 1. Functional expression of AQP1 water channel in Xenopus laevis oocytes.

Incubation in hypotonic buffer fails to cause swelling of a control oocyte (left). In contrast, an oocyte injected with AQP1 cRNA (right) exhibits high water permeability and has exploded. Reprinted from Science with permission (Preston et al. 1992).

Structure of AQP1

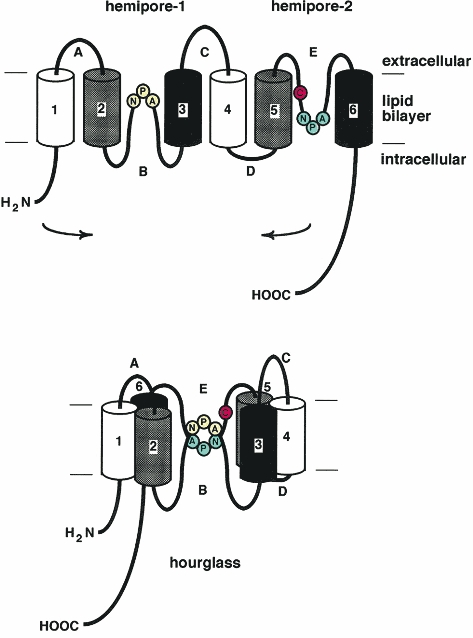

Great effort has been directed toward determining the structure of AQP1, given its unique and specific permeability characteristics. The deduced sequence revealed a previously undescribed topology, two tandem repeats each formed from three transmembrane domains with two highly conserved loops (B and E) containing the signature motif, asparagine-proline-alanine (NPA). Curiously, the repeats were predicted to be oriented at 180 deg with respect to each other (Fig. 2, top). This unique symmetry was confirmed by expressing site-directed insertion mutants of AQP1 in Xenopus laevis oocytes (Preston et al. 1994a). The site of mercurial inhibition was demonstrated at Cys-189 proximal to the NPA motif in loop E. Mutants with replacement of residues flanking the NPA by residues of larger molecular mass did not exhibit water permeability, suggesting that loop E formed part of the aqueous pore (Preston et al. 1993). When the corresponding position preceding the NPA motif in loop B (Ala-73) was replaced by a cysteine, the water permeability was also inhibited by mercurials. When residues flanking the NPA motif were replaced with larger residues, it was observed that this loop B also behaved as though it formed part of the aqueous pore. Together, these studies led to the proposal that the AQP1 subunits each contain an internal aqueous pore formed in part by the ‘hourglass’ (Fig. 2, bottom), the structure resulting from loops B and E which fold into the bilayer from the opposite sides of the membrane touching midway between the leaflets of the bilayer (Jung et al. 1994b).

Figure 2. Hourglass model for AQP1 topology.

Arrangement of loops B and E with highly conserved NPA motifs forms a single aqueous pathway through the AQP1 subunit. Reprinted from Journal of Biological Chemistry with permission (Jung et al. 1994b).

In 1992, a longstanding collaboration was begun with Andreas Engel and colleagues at the Biozentrum at the University of Basel, Switzerland, and subsequently with Yoshinori Fujiyoshi and colleagues at the Kyoto University, Japan, to solve the structure of AQP1 protein. Using the purification methods made simple by pre-extraction of membrane vesicles with N-lauroylsarcosine, up to 5 mg of AQP1 could be purified to homogeneity from a pint of human blood (Smith & Agre, 1991). When high concentrations of the protein were carefully reconstituted into lipid bilayers by dialysis, uniform lattices (‘membrane crystals’) were formed in which the protein retained 100 % of its water transport activity (Walz et al. 1994b). The tetrameric organization of the protein was clearly established at low resolution, and its organization in the membrane was determined by 3D electron microscopy of negatively stained samples (Walz et al. 1994a). Refined membrane crystals studied at tilts of up to 60 deg, with the technically advanced electron microscope developed by our colleagues in Kyoto, produced an electron density map at 3.8 Å resolution. Modelling with the primary sequence of AQP1 using constraints established from studies of the recombinants yielded the first atomic model for AQP1 structure (Murata et al. 2000). Another model based on electron microscopy was published with different main chain orientation in the same helical arrangement (Ren et al. 2001).

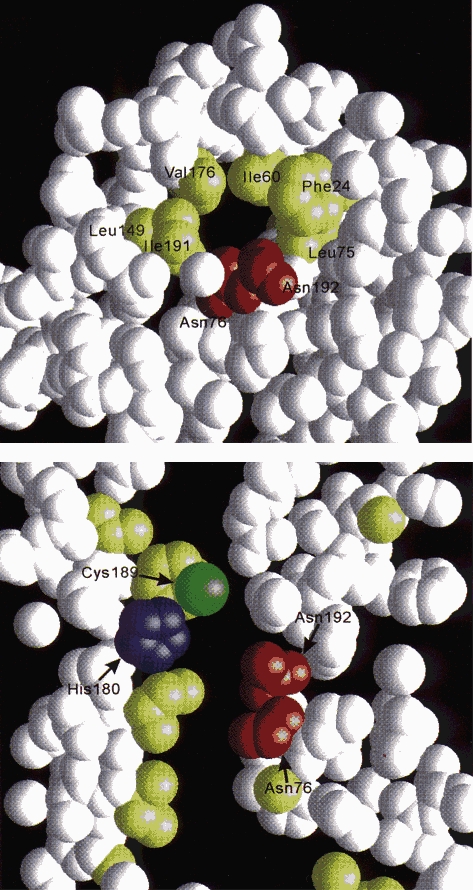

Unlike ion channels, in which four subunits surround a central pore, AQP1 exists as a tetramer with each subunit containing its own pore. The pore narrows to approximately 3 Å diameter midway between the leaflets of the bilayer. At this point, the walls formed from transmembrane domains TM1, 2, 4, and 5 are hydrophobic, whereas the two highly conserved Asn-76 and Asn-192 in the NPA motifs are juxtaposed, as predicted in the hourglass model, providing the polar residues for hydrogen bonding (Fig. 3). In addition, the terminal parts of the pore-forming loops B and E each contain short α-helices which create a partial positive charge in the centre of the membrane. This structure lies just below a 2.8 Å constriction surrounded by residues Phe-56, His-180, Cys-189 (the mercury inhibition site), and Arg-195 which is well recognized in the refined AQP1 structure (de Groot et al. 2001). Arg-195 is nearly perfectly conserved among all members of the large aquaporin gene family and provides a functionally important positive charge at the narrowest segment of the channel. His-180 is uncharged at neutral pH, but becomes protonated at lower pH, providing a second positive charge. Together, Arg-195, His-180 and the positive dipoles from the pore helices provide strong repelling charges resisting passage of protons (hydronium ions) during water permeation.

Figure 3. AQP1 structure determined by electron crystallography.

Space-filling model of AQP1 reveals three dimensional structure of aqueous pore. Top, horizontal section midway through AQP1 subunit shows 3 Å pore surrounded by hydrophobic residues (yellow) and tandem hydrogen-binding sites (Asn-192 and Asn-76, red). Bottom, vertical section shows aqueous channel lined by functionally important residues (Cys-189, His-180, Asn-76 and Asn-192; Arg-195 is not shown). Reprinted from Nature with permission (Murata et al. 2000).

The ability to confer minimal resistance to water permeation while excluding larger or charged solutes is well-explained by these structural features of AQP1. In particular, the ability to block proton transport clarifies how the kidneys can reabsorb hundreds of litres of water from glomerular filtrate each day while excreting acid. Importantly, X-ray diffraction analysis of three-dimensional crystals of the E. coli homologue GlpF at 2.2 Å resolution (Fu et al. 2000) permitted refinement of the AQP1 structure (de Groot et al. 2001) that is virtually identical to the model determined from three dimensional crystals of bovine AQP1 at 2.2 Å resolution (Sui et al. 2001). Real-time molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that rotation of water occurs during passage past the juxtaposed Asn-76 and Asn-192 of the NPA motifs (de Groot & Grubmuller, 2001). The molecular dynamic studies were also undertaken by other investigators (Kong & Ma, 2001; Tajkhorshid et al. 2002). Structural studies and molecular dynamics simulations have brought a remarkably high level of atomic understanding to the process of membrane water transport. Investigators in diverse fields of biomedical research now recognize that aquaporins provide the mechanism for rapid and selective movement of water through biological membranes.

Distribution of AQP1

In November 1991, a longstanding collaboration was initiated with Søren Nielsen and his team at the University of Aarhus, Denmark. Our goal was to localize AQP1 (and subsequently other aquaporin proteins) in kidney and other tissues at a cellular and sub-cellular level using light microscopy and immunoelectron microscopy. These studies provided clear evidence for the physiological and pathological roles for AQP1 and firmly predicted the existence of homologous proteins at other sites.

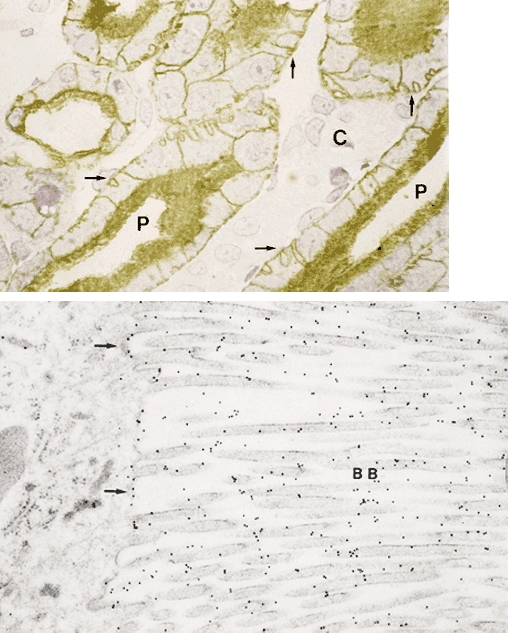

Since the early career of Homer Smith in the 1930s, the kidney has attracted the interest of transport physiologists more than any other organ. Using affinity-purified antibody specific to the C-terminus of the AQP1 protein and a second antibody to the N-terminus, the location of AQP1 was pinpointed in the apical brush border and basolateral membranes of proximal tubules (Fig. 4) and descending thin limbs of Henle in kidneys from rats (Nielsen et al. 1993c) and humans (Maunsbach et al. 1997). In addition, the protein was identified in descending vasa recta (Pallone et al. 1997), defining the pathway for the transfer of large amounts of water from tubular lumen to the interstitium and then into the vascular space. AQP1 protein was clearly shown to be present only in the plasma membranes at these sites and not in intracellular sites. Thus, the paradigm was established that water is transported across the epithelium of proximal tubules and descending thin limbs through AQP1 in the apical and basolateral plasma membranes with the driving force provided by small standing osmotic gradients created by the vectorial movement of solutes through specific transport proteins in these membranes (Nielsen & Agre, 1995).

Figure 4. Immunolocalization of AQP1 in rat kidney.

Top, anti-AQP1 immunohistochemical evaluation of proximal convoluted tubule in outer medulla shows AQP1 in apical and basolateral membranes. Basal membrane (arrows); lumen (P); collecting duct (C). Bottom, anti-AQP1 immunogold electron microscopic examination of apical brush border (BB). Reprinted from Journal of Cell Biology with permission (Nielsen et al. 1993c).

AQP1 protein was also demonstrated in other tissues with important secretory roles including choroid plexus (cerebrospinal fluid), non-pigment epithelium in anterior compartment of eye (aqueous humour), cholangiocytes (bile), and capillary endothelium in many organs including bronchial circulation of lung (Nielsen et al. 1993b). Importantly, renal collecting ducts were found to totally lack AQP1, firmly predicting the need for multiple water channel proteins. Likewise, salivary gland epithelium lacked AQP1 protein, predicting the existence of other homologues.

AQP1 null humans

Identification of people totally lacking AQP1 protein permitted demonstration of the importance of this protein to human physiology. The AQP1 locus was mapped to human chromosome 7p14 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (Moon et al. 1993). The Colton (Co) blood group antigens had previously been linked to the short arm of human chromosome 7 (Zelinski et al. 1990). Anti-Co immunoprecipitation studies and sequencing of DNA from individuals with defined Co blood types revealed that the Co antigens are the result of a polymorphism in AQP1 at the extracellular site of loop A which connects the first and second bilayer-spanning domains – Coa has Ala-45 while the less common Cob has Val-45 (Smith et al. 1994).

Individuals lacking Coa and Cob were known to be exceedingly rare, since only six kindreds were listed by the International Blood Group Registry in Bristol, UK. The Co null probands are women who became sensitized during pregnancy, causing them to have circulating anti-Co antibodies. These antibodies make it impossible for these patients to receive heterologous blood transfusions, so each Co null individual has units of her own blood cryopreserved in local blood banks. We obtained blood, urine and DNA from Co null individuals from three different kindreds, and each was found to lack AQP1 protein in red cells and urine sediment. The proband in each kindred was found to be homozygous for a different disruption of the AQP1 gene (hence ‘AQP1 null’) – deletion of exon 1, frame-shift in exon 1, or destabilizing mutation at the end of the first transmembrane domain (Preston et al. 1994b). Surprisingly, the AQP1 null individuals led normal lives and were entirely unaware of any physical limitations.

Careful clinical analyses of the AQP1 null individuals were undertaken to identify possible physiological abnormalities in renal concentration and capillary permeability. In the first study, two unrelated AQP1 null individuals underwent detailed analyses at the Johns Hopkins Hospital before and during water deprivation by an approved protocol with defined endpoints and safety mechanisms. Baseline studies were entirely normal. When thirsted for up to 24 h, both subjects exhibited normal serum osmolalities and normal serum vasopressin levels which rose as expected after approximately 6 h of thirsting. The major surprise was that neither AQP1 null individual could concentrate urine above 450 mosmol kg−1 even after 24 h of thirsting. Moreover, the patients could not concentrate urine above 450 mosmol kg−1 even after infusion of vasopressin or 3 % NaCl, to maximally stimulate urinary concentration (King et al. 2001). In contrast to the AQP1 null individuals, normal individuals all respond to overnight thirsting by concentrating their urine to approximately 1000 mosmol kg−1.

The AQP1 null subjects were not polyuric, and they did not exhibit abnormalities of glomerular filtration rate, free water clearance, or lithium clearance (indices of proximal tubule function). The concentration defect is believed to result from a combination of reduced water transport across the descending thin limbs and reduced water transport into and out of the vasa recta. Thus AQP1 null individuals have partially lost their ability to generate medullary hyperosmolality needed for efficient concentration by the countercurrent mechanism. While this does not interfere with normal day-to-day life, the Co null individuals are at risk for life-threatening clinical problems should they become dehydrated due to another illness or environmental causes.

The expression of AQP1 in lumenal and ablumenal membranes of capillary endothelium suggests that the protein may play an important role in movement of water between vacular space and interstitium (Nielsen et al. 1993b,c). Moreover, the expression of AQP1 in capillary endothelium appears to be actively modulated by various stimuli in vivo. For example, expression of AQP1 in pulmonary capillary endothelium in rat is increased up to 10-fold by corticosteroids, and expression in rat lung also occurs precisely at the time of birth (King et al. 1996, 1997). AQP1 in cultured fibroblasts is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway (Leitch et al. 2001). It is considered very likely that these processes will also be found to occur in human physiology.

The possibility that human AQP1 null individuals will manifest physiological abnormalities due to the lack of AQP1 protein in vascular endothelium was evaluated with a second approved clinical research protocol. The AQP1 null individuals were examined by high resolution computer tomography of lung before and after rapid infusion of 3 h of warmed physiological saline (King et al. 2002). Each of five normal individuals and both AQP1 null individuals sustained engorgement of pulmonary vessels (20 % increase in cross-sectional area) after the infusions of fluid. Each of the five normal individuals manifested a significant increase in the thickness of bronchiolar walls (up to 40 % increase in wall area) consistent with early peribronchiolar oedema formation. Each of the normal individuals was aware of moderate pulmonary congestion (incipient pulmonary oedema) that disappeared over the following hours. Surprisingly, neither of the two AQP1 null individuals was found to have increased bronchiolar wall thicknesses, and neither complained of any symptoms of pulmonary congestion.

These findings paradoxically suggest that lack of AQP1 may protect against acute onset pulmonary oedema. Nevertheless, in settings such as congestive heart failure, pulmonary oedema appears over several hours or days. Since AQP1 is also the pathway for fluid reuptake into the vascular bed, these studies predicted that AQP1 null individuals would be at a severe disadvantage if they experienced subacute or chronic fluid overload. Thus, it is predicted that AQP1 null individuals would be unable to rapidly dissipate oedema by returning fluid to the vascular space. While unproven, the rapid clearance of water from lung at birth may not be fully operational in AQP1 null subjects and may therefore explain why AQP1 null subjects are so extremely rare. Moreover, reduced expression of AQP1 in lung of premature infants could very well contribute to the severe respiratory difficulties commonly found in neonatal intensive care units.

Multiple aquaporins

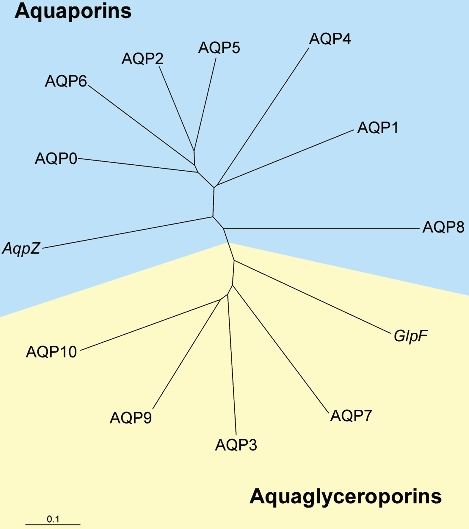

Following the discovery of AQP1, research groups in Europe, Japan and the USA joined the quest to isolate cDNAs encoding aquaporins from sites where water transport is known to be high (reviewed by Agre et al. 1998). The existence of highly conserved sequences has made this possible using polymerase chain amplifications at reduced stringency. From these studies, ten mammalian aquaporins have been identified (Fig. 5). Sequence for an eleventh homologue (AQP10) has been published, but confirmation of protein expression is still lacking (Hatakeyama et al. 2001). Studies of humans and lab animals have been undertaken. Mice with targeted gene disruptions have also been generated (reviewed by Agre, 1998; Verkman, 2000). The results of numerous studies have underscored the importance of these proteins to basic physiology as well as the pathophysiology of several disease states. In addition, more than 200 different aquaporin sequences from diverse species have now appeared in the genetics database indicating the importance of aquaporins throughout nature.

Figure 5. Human aquaporin gene family.

Water permeable (aquaporins) and glycerol permeable (aquaglyceroporins) family members are shown. AQP10 is included, but no confirmation of protein expression is yet published. Shown also are E. coli homologues (AqpZ and GlpF). The scale bar represents genetic distance between homologues.

AQP2 – vasopressin-regulated water channel of renal collecting ducts

The identification of AQP1 drew immediate interest from renal physiologists. Moreover the lack of AQP1 in collecting duct principal cells predicted the existence of homologous proteins at the site where vasopressin had long been known to regulate water transport. Using oligonucleotide primers designed from the highly conserved NPA motifs of AQP1, a cDNA was isolated from collecting duct (Fushimi et al. 1993). This collecting duct homologue, now referred to as AQP2, was shown to confer increased water permeability when expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, and was inhibited by mercurials. AQP2 was localized in collecting duct principal cells and studies of chronically thirsted rats showed that AQP2 expression is enhanced (Nielsen et al. 1993a).

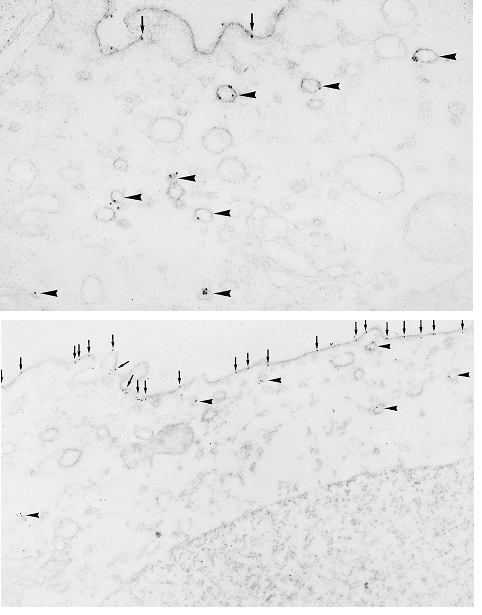

The function and distribution of AQP2 were clearly defined by analysis of collecting ducts (Nielsen et al. 1995). Water transport was measured in isolated, perfused rat collecting ducts in the absence of vasopressin, after addition of 100 pm vasopressin, and after removal of the agent. Collecting ducts were fixed and AQP2 protein was localized by immunogold electron microscopy (Fig. 6). By this approach, it was shown that AQP2 is largely restricted to intracellular vesicles in the basal state, but vasopressin induces redistribution to the apical membrane accompanied by a fivefold increase in water permeability. When vasopressin was removed, AQP2 is reinternalized and the water permeability returns to baseline. AQP2 was subsequently shown to be regulated by exocytosis by receptor-activated adenylyl cyclase-protein kinase A phosphorylation of Ser-256 in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the protein (Katsura et al. 1995; Christensen et al. 2000). Subsequently, AQP3 was shown to reside at the basolateral membranes of principal cells (Ecelbarger et al. 1995). Together, AQP2 in the apical membrane and AQP3 in the basolateral membrane provide the transcellular pathway for water to move from lumen across the collecting duct into the interstitium.

Figure 6. Immunolocalization of AQP2 in isolated rat collecting duct.

Top, anti-AQP2 immunogold electron microscopic examination of unstimulated collecting duct shows predominant labelling of intracellular vesicles. Bottom, after incubation with 100 pm vasopressin, collecting duct shows predominant labelling at apical surface (arrows). Reprinted from Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA with permission (Nielsen et al. 1995).

These studies suggested that AQP2 may be involved in some types of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI). This important clinical disorder had previously been shown to result from mutations in the gene encoding the V2 receptor for vasopressin in X-linked NDI (Bichet, 1998). Investigators at University of Nijmegen, the Netherlands, had previously identified patients with recessively inherited NDI who did not have mutations in the gene encoding V2. By sequencing the structural AQP2 gene, they identified mutations in the transmembrane and pore-forming domains of AQP2 (Deen et al. 1994). These mutations cause misfolding of the AQP2 protein which is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. Subsequently, a family with dominantly inherited NDI was identified, and the site of the mutation was found to lie two residues distal to the PKA phosphorylation site (Mulders et al. 1998). Interestingly, the mutant protein oligomerizes with the wild-type AQP2, and the complex is retained in the Golgi.

Animal models for important and frequently encountered disorders of water balance have been shown by multiple research groups to include abnormal expression of AQP2 protein (see reviews by Schrier et al. 1998; Yamamoto & Sasaki, 1998; Kwon et al. 2001). AQP2 was found to be under-expressed in renal concentration defects with polyuria including classical diabetes insipidus (simple deficiency of vasopressin), lithium therapy (commonly used for therapy of bipolar disorder), post-obstruction (often following transurethral prostatectomy), hypokalaemia (consequence of anti-hypertensive medications), and even nocturnal enuresis. In contrast, AQP2 was found to be over-expressed in fluid retention states such as congestive heart failure, syndrome of inappropriate ADH, cirrhosis, and even pregnancy. Thus, secondary disorders of AQP2 are of paramount importance to the practice of clinical medicine. Moreover, these studies predicted that additional members of the aquaporin family would be identified, and that these aquaporins participate in other important clinical disorders predicted by the sites where the proteins are expressed.

AQP6 – gated ion channel of renal collecting ducts

The functional repertoire of aquaporins was expanded by discovery of AQP6. Although AQP6 may exist in tissues outside the collecting duct, cross-reactivity of the AQP6 antibody has precluded rigorous studies of non-renal tissues. Nevertheless, AQP6 was clearly identified in acid-secreting α-intercalated cells from renal collecting duct where the protein was restricted to intracellular sites (Yasui et al. 1999b). Further analysis showed that AQP6 is colocalized alongside H+-ATPase in intracellular vesicles, but not in the plasma membrane (Yasui et al. 1999a).

AQP6 is not a simple water channel. When expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, AQP6 resides in the oocyte plasma membrane where it exhibits minimal water permeability. Treatment of AQP6 oocytes with mercuric chloride failed to lower the water permeability, even though inhibition of water permeability, the expected result, had been reported previously by others (Ma et al. 1996). Very surprisingly, we found that low concentrations of mercuric chloride increased the water permeability and induced an accompanying membrane current (Yasui et al. 1999a). Thus, while the primary sequence of AQP6 is closest to AQP2 and AQP5 (both inhibited by mercuric chloride), the structure of AQP6 must contain functionally important differences.

The location of AQP6 in intracellular vesicles also containing H+-ATPase (Yasui et al. 1999b) suggests a role in the secretion of acid. Importantly, AQP6 ion currents become rapidly and reversibly activated at low pH, confirming that AQP6 may participate in acid secretion by α-intercalated cells. Study of rats exposed to chronic acidosis did not manifest changes in AQP6 expression, but chronic alkalosis and water loading resulted in a significant increase in AQP6 expression (Promeneur et al. 2000). The membrane currents carried by AQP6 are relatively selective for anions, and single channel studies indicate that rapid flickering occurs. These studies are being further delineated by analysis of mice bearing targeted disruption of the gene encoding AQP6 (M. Yasui, unpublished observations). Presently, it is believed that AQP6 may be linked to some forms of acid-base disturbances.

AQP0 – lens major intrinsic protein (MIP)

Before the functional identification of AQP1, an abundant protein had been identified in lens fibre cells (Gorin et al. 1984; Zampighi et al. 1989), although its function was unclear. MIP was initially thought to be a gap junction protein, but it was found to be unrelated to connexins (Ebihara et al. 1989). After discovery of the function of AQP1, expression of MIP in oocytes was shown to induce a relatively small increase in water permeability not inhibited by mercurials – thus the symbol AQP0 (Mulders et al. 1995). Unlike other aquaporins, electron and atomic force microscopic studies of AQP0 have generated evidence that this protein may have a structural role as a cell-to-cell adhesion protein (Fotiadis et al. 2000). While this role is still unestablished for AQP0, the paradigm that transport proteins may be structurally important components of the cell skeleton has been established by studies of the anion exchanger, band 3 (Van Dort et al. 2001).

The relationship of AQP0 to human disease emerged from genetic linkage studies of large kindreds with congenital cataracts. Two such families from the United Kingdom were linked to human chromosome 12q13, and point mutations were identified in each – Glu-134-Gly in one family and Thr-138-Arg in the other (Berry et al. 2000). The human AQP0 was cloned and mutated to Gly-134 or Arg-138, and the cRNAs were injected into Xenopus laevis oocytes. Although the mutant proteins were expressed, trafficking to the plasma membrane was impaired (Francis et al. 2000).

The inheritance pattern of the cataracts was clearly dominant in each of the families. The loss of vision first appeared in members of each family while they were small children, but the morphology of the cataracts was distinctly different in the two families. Patients with Glu-134-Gly suffered from lamellar opacities corresponding to the size of the lens at birth. Curiously, this observation suggests that the lens is somehow stressed in a special manner during the neonatal period, but not before birth or afterwards. Patients with the Thr-138-Arg mutation sustain a lifelong problem with newly appearing opacities throughout the lens body. The sites of these mutations were found to reside in important structural areas. Glu-134 is conserved in all known aquaporin homologues, and the atomic structure of AQP1 indicates that this residue lies near the highly conserved residue Arg-187 and may restrict the orientation of loop E within the six transmembrane domains (de Groot et al. 2001; Sui et al. 2001). When Thr-138 is replaced by a bulky Arg, a space restriction and a competing positive charge may alter the orientation of Glu-134. The occurrence of early onset cataracts associated with major defects in the AQP0 structure strongly suggests that less severe defects will be found in some patients with typical, late-onset cataracts common in the elderly, or in some patients with cataracts found in association with diabetes mellitus or chronic ultraviolet light exposure. Thus, searches for human mutations in the gene encoding AQP0 are being pursued.

AQP4 – water channel protein in brain

The cDNA encoding AQP4 was obtained from brain where the protein is abundant (Jung et al. 1994a). This member of the aquaporin family is not sensitive to mercurial inhibition (Hasegawa et al. 1994) and lacks a cysteine preceding the NPA motif in loop E which is known to confer mercurial sensitivity to AQP1 (Preston et al. 1993). AQP4 is otherwise constitutively active similar to AQP1.

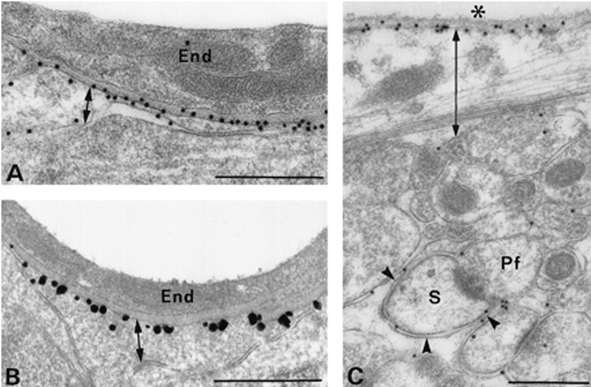

Perhaps in no other organ is the location of a protein more important than in the central nervous system. Expression of AQP4 in brain and retina was established by immunohistochemistry and by immunogold electron microscopy (Nielsen et al. 1997b; Nagelhus et al. 1998). AQP4 protein is most abundant in astroglial cells where brain and liquid interfaces exist – adjacent to the subarachnoid space, adjacent to capillaries, and in ependymal cells lining the ventricles. The astroglial end-feet adjacent to capillary basement membranes form the glia limitans, a domain which has long been known to contain square arrays (also referred to as orthogonal arrays) when freeze fracture replicas are analysed by electron microscopy. Direct anti-AQP4 immunogold labelling identified square arrays as microcrystalline assemblies of AQP4 (Rash et al. 1998). AQP4 protein is also abundant in osmosensory regions of brain, including supraoptic nucleus where it is present in glial lamellae surrounding vasopressin-secretory neurons; AQP4 has not been identified in neurons. Thus in glial cells, AQP4 lies at the membrane opposite to where glutamate transporters are known to reside (Fig. 7), and AQP4 colocalizes in retina with a specific potassium channel, Kir4.1 (Nagelhus et al. 1999). AQP4 has also been shown to reside in the sarcolemma of fast twitch fibres in skeletal muscle (Frigeri et al. 1998).

Figure 7. Polarized expression of AQP4 in rat brain.

A and B, anti-AQP4-immunogold electron microscopy demonstrates AQP4 in glial membranes facing blood vessels but not in membranes facing neuropil. C, anti-AQP4-immunogold electron microscopy demonstrates AQP4 in sub-pial astrocyte membranes. Scale bars: A and B, 0.5 μm; C, 1 μm. Reprinted from Journal of Neuroscience with permission (Nielsen et al. 1997b).

Several clues provide insight into the molecular mechanisms for precise localization of AQP4 in glial cells and fast twitch skeletal muscle fibres. The C-terminus of AQP4 (-Ser-Ser-Val-COOH) conforms to the motif for binding to PDZ domains – a protein-protein association domain named for the proteins where it was first identified, PSD-95, Discs Large, and Z-Occludins (Songyang et al. 1997). This suggested that the localization of AQP4 may be caused by association with cytoskeletal proteins. Mutations in the human gene encoding dystrophin are found in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and the mdx mouse is an animal model for this important disorder. When distribution was analysed in mdx mice, AQP4 expression was grossly abnormal in the mature animals, suggesting that AQP4 may be part of the complex of proteins associated with dystrophin (Frigeri et al. 2001). Selective immunoprecipitations demonstrated that α-syntrophin, a PDZ domain protein in the dystrophin complex, is associated with AQP4 (Neely et al. 2001; Adams et al. 2001). AQP4 is also mistargeted in astroglia of α-syntrophin null mice. Moreover, when expressed by transfection into cultured mammalian cells, survival half-life for full length AQP4 was three times longer than AQP4 lacking the terminal Ser-Ser-Val. AQP4 has been shown to be reduced in skeletal muscle from Duchenne muscular dystrophy and some cases of Becker muscular dystrophy (A. Frigeri, unpublished observations).

The physiological function of AQP4 protein is not yet clear. The association with potassium channels suggests that a function of AQP4 in brain may be to facilitate the transfer of fluid across cell membranes in response to potassium siphoning which occurs after neural stimulation (Nagelhus et al. 1999). It is believed that AQP4 may permit water to cross the blood-brain barrier that separates parenchyma and vascular space. Although most evidence indicates that AQP4 is constitutively active, it has been suggested by one group of investigators that AQP4 in oocytes may be gated shut by phosphorylation in response to phorbol ester treatment (Han et al. 1998). Consistent with this, AQP4 in cultured cells exhibit small changes in water permeability when phorbol diesters are present (M. Zelenina & A. Aperia, unpublished observations). If AQP4 is gated, the fluid passage across the blood-brain barrier may not be constitutively open. Analysis of mice bearing targeted disruption of the gene encoding AQP4 revealed a relative sparing of the null animals when stressed with acute hyponatraemia (Manley et al. 2000). Although the investigators suggested that inhibition of AQP4 may be beneficial, the opposite could easily be true, since dissipation of brain oedema is essential for patients sustaining closed head injuries or after cerebral vascular accidents. Thus, the importance of AQP4 in human cerebral oedema is still undefined.

AQP5 – water channel in secretory glands, lung and eye

First cloned from a submandibular gland cDNA library (Raina et al. 1995), AQP5 has been localized to the apical membrane of multiple secretory glands, including lacrimal glands, salivary glands and submucosal glands of airways (Nielsen et al. 1997a). These sites predicted that AQP5 may be rate limiting for glandular fluid release, as was confirmed in salivary glands and airways from mice bearing targeted disruption of the gene encoding AQP5 (Ma et al. 1999; Song & Verkman, 2001). AQP5 is present in the apical membranes of sweat glands in rat, mouse and humans, and sweat secretion was markedly diminished in paws of AQP5 null mice (Nejsum et al. 2002). The general significance of this observation is yet to be established, since other investigators have concluded that AQP5 is not involved in sweat secretion in mice (Song et al. 2002).

The importance of AQP5 to human disease may also include important disorders of lung and airways. AQP5 has been localized in the apical membranes of type 1 epithelial cells lining the alveoli in rat lung (Nielsen et al. 1997a). The distribution is broader in mouse lung, and surprisingly, AQP5 null mice were found to exhibit increased bronchospasm in response to cholinergic stimulation (Krane et al. 2001). Broader AQP5 distribution has also been shown in human lung (Kreda et al. 2001). Some forms of human asthma have been linked to chromosome 12q close to the site where AQP5 has been identified (Lee et al. 1996), but a role for AQP5 in human asthma has not yet been confirmed.

AQP5 is important to the physiology of human eye. AQP5 is expressed in corneal epithelium at the surface of the eye (Hamann et al. 1998), where it is suspected to contribute epithelial hydration and transparency and may participate in corneal wound healing. AQP5 has been studied in lacrimal glands of the human eye (Gresz et al. 2001). Defective cellular trafficking was noted by immunohistochemical analysis of lacrimal gland biopsies from six patients with Sjögren's syndrome but not in four patients with non-Sjögren's dry eye (Tsubota et al. 2001). The general significance of this is awaited, since defective trafficking of AQP5 has been found in salivary gland biopsies of some Sjögren's patients (Steinfeld et al. 2001) but not others (Beroukas et al. 2001).

AQP3, 7, and 9 – aquaglyceroporins

The identification of AQP3, a homologue permeated by water plus glycerol, contradicted the tenet that all members of the aquaporin family are selectively permeated only by water (Echevarria et al. 1994; Ishibashi et al. 1994; Ma et al. 1994). AQP3 is distributed in multiple organs including kidney (Ecelbarger et al. 1995), airways (Nielsen et al. 1997a), skin (Nejsum et al. 2002), and eye (Hamann et al. 1998). The glycerol permeation has been carefully documented (Zeuthen & Klaerke, 1999), but the physiological significance of glycerol permeation is still not understood (Yang et al. 2001). AQP7 was identified in adipose tissue and was shown to be permeated by water plus glycerol (Ishibashi et al. 1997; Kishida et al. 2000). AQP9 was identified in hepatocytes and was shown to be permeated by water, glycerol and a variety of other small uncharged solutes (Tsukaguchi et al. 1998). The presence of AQP7 in adipocytes and AQP9 in hepatocytes suggests that glycerol permeation may be important during fasting states. Triglycerides are degraded in adipocytes where AQP7 may provide the exit route for glycerol, and AQP9 may provide the entry into hepatocytes where gluconeogenesis occurs. Thus, a physiological role for aquaglyceroporins as glycerol transporters may be important during fasting or starvation. The functional repertoire of AQP7 and AQP9 was recently boosted by the discovery that they are permeated by arsenite, As(OH)3 (Liu et al. 2002). This surprising finding along with the known expression of AQP9 in leukocytes strongly suggests that the protein may be pharmacologically important during the treatment of promyelocytic leukaemia with arsenite.

Aquaporins in non-mammalian organisms

While beyond the focus of this review, it must be mentioned that aquaporins are represented in virtually all life forms and have drawn interest from a tremendous range of biologists. Insects were early shown to contain members of the aquaporin gene family in digestive tract (Le Caherec et al. 1996) and brain (Rao et al. 1990). Aquaporins have been identified throughout the microbial world, and the functions are widely varied (reviewed by Hohmann et al. 2000). Plants express the largest collection of aquaporin homologues and their functions are being identified (reviewed by Johansson et al. 2000; Santoni et al. 2000).

Implications

As summarized in this review, aquaporins have been implicated in numerous physiological and pathological processes in humans and other mammalian species. Although it is impossible to accurately predict all clinical disorders where aquaporins will play pathological roles, preliminary studies suggest that the list of disease states involving aquaporins will be extensive.

Aquaporins have been linked to defects in vision and salivary gland dysfunction, and other examples of aquaporin-mediated defects are expected in visual and oral processes. Structurally severe defects in AQP0 cause some forms of early onset cataracts, and polymorphisms in AQP0 may be identified in some cases of typical cataract found commonly late in life. Thus, sequencing the AQP0 gene from such individuals may reveal inherited risk factors. AQP5 is expressed in multiple sites including cornea (Hamann et al. 1998) where it may participate in corneal wound healing. Defective targeting of AQP5 has been found in lacrimal and salivary glands from some Sjögren's syndrome patients (Tsubota et al. 2001; Steinfeld et al. 2001; Beroukas et al. 2001), suggesting that the sicca syndrome (dry eye and dry mouth) may be heterogeneous. Local gene rescue therapies which have already been used in animal studies (Delporte et al. 1996) may be feasible for some humans. Aqueous humour secretion and absorption are both predicted to involve AQP1, and glaucoma is known to result from small increases in anterior chamber pressure. Still untested is the possibility that aquaporins may contribute to aqueous humour imbalance in glaucoma.

Aquaporins are involved in a variety of other systemic problems. Recognition of AQP5 in sweat glands suggests that the protein may contribute to some forms of hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (Nejsum et al. 2002). AQP5 has been implicated in drug-induced bronchospasm (Krane et al. 2001) and defective airway secretion (Song & Verkman, 2001). Functional relationships between the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) and AQP3 indicate that the regulatory defect in cystic fibrosis may involve both proteins (Schreiber et al. 1999). Our understanding of gastrointestinal fluid secretion and absorption have so far shown that aquaporins may participate in pancreatic (Hurley et al. 2001) and cholangiocytic fluid balance (Marinelli et al. 1997) as well as possible hepatic glycerol and ketone body transport during fasting. It remains still unclear how aquaporins are involved in fluid movements in stomach, small intestine and colon and whether aquaporins are involved in diarrhoeal diseases.

The involvement of aquaporins in several major problems in perinatal medicine is expected. Lactation involves large fluid shifts, but the molecular determinants remain undefined. Problems with aquaporin expression during airway maturation are already predicted from animal studies (Yasui et al. 1997). Large water loss through skin is known to occur in prematurity, and vascular and cutaneous aquaporins must play a role. The roles of AQP1 and AQP2 in renal-vascular fluid balance have already been clearly established, but the possible involvement in additional disorders such as pre-eclampsia or eclampsia of pregnancy warrants investigation. The roles of aquaporins may provide new approaches to far-reaching problems. Taken together, it is realistic to conclude that many more chapters in the aquaporin story still remain to be written.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the International Union of Physiological Sciences, The Journal of Physiology Lecture Committee, and the Nobel Jubilee Symposium Committee. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. We thank David Kozono for his expert assistance in preparing the figures.

REFERENCES

- Adams ME, Mueller HA, Froehner SC. In vivo requirement of the alpha-syntrophin PDZ domain for the sarcolemmal localization of nNOS and aquaporin-4. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;155:113–122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agre P. Molecular physiology of water transport: aquaporin nomenclature workshop. Mammalian aquaporins. Biology of the Cell. 1997;89:255–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agre P. Aquaporin null phenotypes: the importance of classical physiology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:9061–9063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agre P, Bonhivers M, Borgnia MJ. The aquaporins, blueprints for cellular plumbing systems. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:14659–14662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agre P, Preston GM, Smith BL, Jung JS, Raina S, Moon C, Guggino WB, Nielsen S. Aquaporin CHIP: the archetypal molecular water channel. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:F463–476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.4.F463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agre P, Saboori AM, Asimos A, Smith BL. Purification and partial characterization of the Mr 30,000 integral membrane protein associated with the erythrocyte Rh(D) antigen. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:17497–17503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukas D, Hiscock J, Jonsson R, Waterman SA, Gordon TP. Subcellular distribution of aquaporin 5 in salivary glands in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Lancet. 2001;358:1875–1876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry V, Francis P, Kaushal S, Moore A, Bhattacharya S. Missense mutations in MIP underlie autosomal dominant ‘polymorphic’ and lamellar cataracts linked to 12q. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:15–17. doi: 10.1038/75538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet DG. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. American Journal of Medicine. 1998;105:431–442. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen BM, Zelenina M, Aperia A, Nielsen S. Localization and regulation of PKA-phosphorylated AQP2 in response to V2-receptor agonist/antagonist treatment. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology. 2000;278:F29–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deen PM, Verdijk MA, Knoers NV, Wieringa B, Monnens LA, Van Os CH, Van Oost BA. Requirement of human renal water channel aquaporin-2 for vasopressin- dependent concentration of urine. Science. 1994;264:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot BL, Engel A, Grubmuller H. A refined structure of human aquaporin-1. FEBS Letters. 2001;504:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot BL, Grubmuller H. Water permeation across biological membranes: mechanism and dynamics of aquaporin-1 and GlpF. Science. 2001;294:2353–2357. doi: 10.1126/science.1066115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delporte C, O'connell BC, He X, Ambudkar IS, Agre P, Baum BJ. Adenovirus-mediated expression of aquaporin-5 in epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:22070–22075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker BM, Smith BL, Kuhajda FP, Agre P. Identification, purification, and partial characterization of a novel Mr 28,000 integral membrane protein from erythrocytes and renal tubules. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:15634–15642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara L, Beyer EC, Swenson KI, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Cloning and expression of a Xenopus embryonic gap junction protein. Science. 1989;243:1194–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.2466337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecelbarger CA, Terris J, Frindt G, Echevarria M, Marples D, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Aquaporin-3 water channel localization and regulation in rat kidney. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:F663–672. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.5.F663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria M, Windhager EE, Tate SS, Frindt G. Cloning and expression of AQP3, a water channel from the medullary collecting duct of rat kidney. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:10997–11001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis D, Hasler L, Muller DJ, Stahlberg H, Kistler J, Engel A. Surface tongue-and-groove contours on lens MIP facilitate cell-to-cell adherence. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;300:779–789. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis P, Chung JJ, Yasui M, Berry V, Moore A, Wyatt MK, Wistow G, Bhattacharya SS, Agre P. Functional impairment of lens aquaporin in two families with dominantly inherited cataracts. Human Molecular Genetics. 2000;9:2329–2334. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.hmg.a018925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Nico B, Quondamatteo F, Herken R, Roncali L, Svelto M. Aquaporin-4 deficiency in skeletal muscle and brain of dystrophic mdx mice. FASEB Journal. 2001;15:90–98. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0260com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Verbavatz JM, Valenti G, Svelto M. Expression of aquaporin-4 in fast-twitch fibers of mammalian skeletal muscle. Journal of Clinical Invesigation. 1998;102:695–703. doi: 10.1172/JCI2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D, Libson A, Miercke LJ, Weitzman C, Nollert P, Krucinski J, Stroud RM. Structure of a glycerol-conducting channel and the basis for its selectivity. Science. 2000;290:481–486. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushimi K, Uchida S, Hara Y, Hirata Y, Marumo F, Sasaki S. Cloning and expression of apical membrane water channel of rat kidney collecting tubule. Nature. 1993;361:549–552. doi: 10.1038/361549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin M, Yancey S, Cline J, Revel J, Horwitz J. The major intrinsic protein (MIP) of the bovine lens fiber membrane. Cell. 1984;39:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresz V, Kwon TH, Hurley PT, Varga G, Zelles T, Nielsen S, Case RM, Steward MC. Identification and localization of aquaporin water channels in human salivary glands. American Journal of Physiology – Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2001;281:G247–254. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.1.G247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, Zeuthen T, La Cour M, Nagelhus EA, Ottersen OP, Agre P, Nielsen S. Aquaporins in complex tissues: distribution of aquaporins 1–5 in human and rat eye. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C1332–1345. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Wax MB, Patil RV. Regulation of aquaporin-4 water channels by phorbol ester-dependent protein phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:6001–6004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Ma T, Skach W, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Molecular cloning of a mercurial-insensitive water channel expressed in selected water-transporting tissues. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:5497–5500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S, Yoshida Y, Tani T, Koyama Y, Nihei K, Ohshiro K, Kamiie JI, Yaoita E, Suda T, Hatakeyama K, Yamamoto T. Cloning of a new aquaporin (AQP10). abundantly expressed in duodenum and jejunum. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;287:814–819. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman J, Agre P. A new face of the Rhesus antigen. Nature Genetics. 2000;26:258–259. doi: 10.1038/81532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann I, Bill RM, Kayingo I, Prior BA. Microbial MIP channels. Trends in Microbiology. 2000;8:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley PT, Ferguson CJ, Kwon TH, Andersen ML, Norman AG, Steward MC, Nielsen S, Case RM. Expression and immunolocalization of aquaporin water channels in rat exocrine pancreas. American Journal of Physiology – Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2001;280:G701–709. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi K, Kuwahara M, Gu Y, Kageyama Y, Tohsaka A, Suzuki F, Marumo F, Sasaki S. Cloning and functional expression of a new water channel abundantly expressed in the testis permeable to water, glycerol, and urea. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:20782–20786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi K, Sasaki S, Fushimi K, Uchida S, Kuwahara M, Saito H, Furukawa T, Nakajima K, Yamaguchi Y, Gojobori T. Molecular cloning and expression of a member of the aquaporin family with permeability to glycerol and urea in addition to water expressed at the basolateral membrane of kidney collecting duct cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:6269–6273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I, Karlsson M, Johanson U, Larsson C, Kjellbom P. The role of aquaporins in cellular and whole plant water balance. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1465:324–342. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JS, Bhat RV, Preston GM, Guggino WB, Baraban JM, Agre P. Molecular characterization of an aquaporin cDNA from brain: candidate osmoreceptor and regulator of water balance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994a;91:13052–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.13052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JS, Preston GM, Smith BL, Guggino WB, Agre P. Molecular structure of the water channel through aquaporin CHIP. The hourglass model. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994b;269:14648–14654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsura T, Verbavatz JM, Farinas J, Ma T, Ausiello DA, Verkman AS, Brown D. Constitutive and regulated membrane expression of aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 2 water channels in stably transfected LLC-PK1 epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:7212–7216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Choi M, Fernandez PC, Cartron JP, Agre P. Defective urinary-concentrating ability due to a complete deficiency of aquaporin-1. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:175–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Nielsen S, Agre P. Aquaporin-1 water channel protein in lung: ontogeny, steroid-induced expression, and distribution in rat. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97:2183–2191. doi: 10.1172/JCI118659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Nielsen S, Agre P. Aquaporins in complex tissues. I. Developmental patterns in respiratory and glandular tissues of rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:C1541–1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Nielsen S, Agre P, Brown RH. Decreased pulmonary vascular permeability in aquaporin-1-null humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:1059–1063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022626499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida K, Kuriyama H, Funahashi T, Shimomura I, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Takahashi M, Hotta K, Nakamura T, Yamashita S, Tochino Y, Matsuzawa Y. Aquaporin adipose, a putative glycerol channel in adipocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:20896–20902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Ma J. Dynamic mechanisms of the membrane water channel aquaporin-1 (AQP1) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:14345–14349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251507998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krane CM, Melvin JE, Nguyen HV, Richardson L, Towne JE, Doetschman T, Menon AG. Salivary acinar cells from aquaporin 5 deficient mice have decreased membrane permeability and altered cell volume regulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:23413–23420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreda SM, Gynn MC, Fenstermacher DA, Boucher RC, Gabriel SE. Expression and localization of epithelial aquaporins in the adult human lung. American Journal of Respiratory Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2001;24:224–234. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.3.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon TH, Hager H, Nejsum LN, Andersen ML, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S. Physiology and pathophysiology of renal aquaporins. Seminars in Nephrology. 2001;21:231–238. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.21647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Caherec F, Deschamps S, Delamarche C, Pellerin I, Bonnec G, Guillam MT, Thomas D, Gouranton J, Hubert JF. Molecular cloning and characterization of an insect aquaporin functional comparison with aquaporin 1. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1996;241:707–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MD, Bhakta KY, Raina S, Yonescu R, Griffin CA, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Preston GM, Agre P. The human aquaporin-5 gene. Molecular characterization and chromosomal localization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:8599–8604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch V, Agre P, King LS. Altered ubiquitination and stability of aquaporin-1 in hypertonic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:2894–2898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041616498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Shen J, Carbrey JM, Mukhopadhyay R, Agre P, Rosen B. Arsenite transport by mammalian aquaglyceroporins AQP7 and AQP9. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:6053–6058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092131899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Frigeri A, Hasegawa H, Verkman AS. Cloning of a water channel homolog expressed in brain meningeal cells and kidney collecting duct that functions as a stilbene-sensitive glycerol transporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:21845–21849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Song Y, Gillespie A, Carlson EJ, Epstein CJ, Verkman AS. Defective secretion of saliva in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-5 water channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:20071–20074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Yang B, Kuo WL, Verkman AS. cDNA cloning and gene structure of a novel water channel expresed exclusively in human kidney. Genomics. 1996;35:543–550. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GT, Fujimura M, Ma T, Noshita N, Filiz F, Bollen AW, Chan P, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nature Medicine. 2000;6:159–163. doi: 10.1038/72256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli RA, Pham L, Agre P, Larusso NF. Secretin promotes osmotic water transport in rat cholangiocytes by increasing aquaporin-1 water channels in plasma membrane. Evidence for a secretin-induced vesicular translocation of aquaporin-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:12984–12988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsbach AB, Marples D, Chin E, Ning G, Bondy C, Agre P, Nielsen S. Aquaporin-1 water channel expression in human kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1997;8:1–14. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V811. (published erratum appears in Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 8, 358–360) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon C, Preston GM, Griffin CA, Jabs EW, Agre P. The human aquaporin-CHIP gene. Structure, organization, and chromosomal localization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:15772–15778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders SM, Bichet DG, Rijss JP, Kamsteeg EJ, Arthus MF, Lonergan M, Fujiwara M, Morgan K, Leijendekker R, Van Der Sluijs P, Van Os CH, Deen PM. An aquaporin-2 water channel mutant which causes autosomal dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is retained in the Golgi complex. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102:57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders SM, Preston GM, Deen PM, Guggino WB, Van Os CH, Agre P. Water channel properties of major intrinsic protein of lens. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:9010–9016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.9010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Mitsuoka K, Hirai T, Walz T, Agre P, Heymann JB, Engel A, Fujiyoshi Y. Structural determinants of water permeation through aquaporin-1. Nature. 2000;407:599–605. doi: 10.1038/35036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhus EA, Horio Y, Inanobe A, Fujita A, Haug FM, Nielsen S, Kurachi Y, Ottersen OP. Immunogold evidence suggests that coupling of K+ siphoning and water transport in rat retinal Muller cells is mediated by a coenrichment of Kir4. 1 and AQP4 in specific membrane domains. Glia. 1999;26:47–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199903)26:1<47::aid-glia5>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhus EA, Veruki ML, Torp R, Haug FM, Laake JH, Nielsen S, Agre P, Ottersen OP. Aquaporin-4 water channel protein in the rat retina and optic nerve: polarized expression in Muller cells and fibrous astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:2506–2519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02506.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely JD, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Ottersen OP, Froehner SC, Agre P, Adams ME. Syntrophin-dependent expression and localization of aquaporin-4 water channel protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:14108–14113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241508198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejsum LN, Kwon TH, Jensen UB, Fumagalli O, Frokiaer J, Krane CM, Menon AG, King LS, Agre PC, Nielsen S. Functional requirement of aquaporin-5 in plasma membranes of sweat glands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2002;99:511–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012588099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Agre P. The aquaporin family of water channels in kidney. Kidney International. 1995;48:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Chou CL, Marples D, Christensen EI, Kishore BK, Knepper MA. Vasopressin increases water permeability of kidney collecting duct by inducing translocation of aquaporin-CD water channels to plasma membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:1013–1017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Digiovanni SR, Christensen EI, Knepper MA, Harris HW. Cellular and subcellular immunolocalization of vasopressin-regulated water channel in rat kidney. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993a;90:11663–11667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, King LS, Christensen BM, Agre P. Aquaporins in complex tissues. II. Subcellular distribution in respiratory and glandular tissues of rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1997a;273:C1549–1561. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Nagelhus EA, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Bourque C, Agre P, Ottersen OP. Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997b;17:171–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Smith BL, Christensen EI, Agre P. Distribution of the aquaporin CHIP in secretory and resorptive epithelia and capillary endothelia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993b;90:7275–7279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Smith BL, Christensen EI, Knepper MA, Agre P. CHIP28 water channels are localized in constitutively water-permeable segments of the nephron. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993c;120:371–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone TL, Kishore BK, Nielsen S, Agre P, Knepper MA. Evidence that aquaporin-1 mediates NaCl-induced water flux across descending vasa recta. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:F587–596. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.5.F587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Agre P. Isolation of the cDNA for erythrocyte integral membrane protein of 28 kilodaltons: member of an ancient channel family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:11110–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Carroll TP, Guggino WB, Agre P. Appearance of water channels in Xenopus oocytes expressing red cell CHIP28 protein. Science. 1992;256:385–387. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5055.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Jung JS, Guggino WB, Agre P. The mercury-sensitive residue at cysteine 189 in the CHIP28 water channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Jung JS, Guggino WB, Agre P. Membrane topology of aquaporin CHIP. Analysis of functional epitope-scanning mutants by vectorial proteolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994a;269:1668–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM, Smith BL, Zeidel ML, Moulds JJ, Agre P. Mutations in aquaporin-1 in phenotypically normal humans without functional CHIP water channels. Science. 1994b;265:1585–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.7521540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promeneur D, Kwon TH, Yasui M, Kim GH, Frokiaer J, Knepper MA, Agre P, Nielsen S. Regulation of AQP6 mRNA and protein expression in rats in response to altered acid-base or water balance. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology. 2000;279:F1014–1026. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.6.F1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina S, Preston GM, Guggino WB, Agre P. Molecular cloning and characterization of an aquaporin cDNA from salivary, lacrimal, and respiratory tissues. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:1908–1912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y, Jan LY, Jan YN. Similarity of the product of the Drosophila neurogenic gene big brain to transmembrane channel proteins. Nature. 1990;345:163–167. doi: 10.1038/345163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Yasumura T, Hudson CS, Agre P, Nielsen S. Direct immunogold labeling of aquaporin-4 in square arrays of astrocyte and ependymocyte plasma membranes in rat brain and spinal cord. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:11981–11986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Reddy VS, Cheng A, Melnyk P, Mitra AK. Visualization of a water-selective pore by electron crystallography in vitreous ice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2001;98:1398–1403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041489198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoni V, Gerbeau P, Javot H, Maurel C. The high diversity of aquaporins reveals novel facets of plant membrane functions. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2000;3:476–481. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R, Nitschke R, Greger R, Kunzelmann K. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activates aquaporin 3 in airway epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:11811–11816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrier RW, Ohara M, Rogachev B, Xu L, Knotek M. Aquaporin-2 water channels and vasopressin antagonists in edematous disorders. Molecular Genetics of Metabolism. 1998;65:255–263. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BL, Agre P. Erythrocyte Mr 28,000 transmembrane protein exists as a multisubunit oligomer similar to channel proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:6407–6415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BL, Preston GM, Spring FA, Anstee DJ, Agre P. Human red cell aquaporin CHIP. I. Molecular characterization of ABH and Colton blood group antigens. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;94:1043–1049. doi: 10.1172/JCI117418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Sonawane N, Verkman AS. Localization of aquaporin-5 in sweat glands and functional analysis using knockout mice. Journal of Physiology. 2002;541:561–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-5 dependent fluid secretion in airway submucosal glands. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:41288–41292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Fanning AS, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, Crompton A, Chan AC, Anderson JM, Cantley LC. Recognition of unique carboxyl-terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997;275:73–77. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld S, Cogan E, King LS, Agre P, Kiss R, Delporte C. Abnormal distribution of aquaporin-5 water channel protein in salivary glands from Sjogren's syndrome patients. Laboratory Investigation. 2001;81:143–148. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui H, Han BG, Lee JK, Walian P, Jap BK. Structural basis of water-specific transport through the AQP1 water channel. Nature. 2001;414:872–878. doi: 10.1038/414872a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajkhorshid E, Nollert P, Jensen MO, Miercke LJ, O'Connell J, Stroud RM, Schulten K. Control of the selectivity of the aquaporin water channel family by global orientational tuning. Science. 2002;296:525–530. doi: 10.1126/science.1067778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota K, Hirai S, King LS, Agre P, Ishida N. Defective cellular trafficking of lacrimal gland aquaporin-5 in Sjogren's syndrome. Lancet. 2001;357:688–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaguchi H, Shayakul C, Berger UV, Mackenzie B, Devidas S, Guggino WB, Van Hoek AN, Hediger MA. Molecular characterization of a broad selectivity neutral solute channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:24737–24743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dort HM, Knowles DW, Chasis JA, Lee G, Mohandas N, Low PS. Analysis of integral membrane protein contributions to the deformability and stability of the human erythrocyte membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:46968–46974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS. Physiological importance of aquaporins: lessons from knockout mice. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2000;9:517–522. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz T, Smith BL, Agre P, Engel A. The three-dimensional structure of human erythrocyte aquaporin CHIP. EMBO Journal. 1994a;13:2985–2993. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz T, Smith BL, Zeidel ML, Engel A, Agre P. Biologically active two-dimensional crystals of aquaporin CHIP. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994b;269:1583–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Sasaki S. Aquaporins in the kidney: emerging new aspects. Kidney International. 1998;54:1041–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Ma T, Verkman AS. Erythrocyte water permeability and renal function in double knockout mice lacking aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:624–628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui M, Hazama A, Kwon TH, Nielsen S, Guggino WB, Agre P. Rapid gating and anion permeability of an intracellular aquaporin. Nature. 1999a;402:184–187. doi: 10.1038/46045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui M, Kwon TH, Knepper MA, Nielsen S, Agre P. Aquaporin-6: An intracellular vesicle water channel protein in renal epithelia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999b;96:5808–5813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui M, Serlachius E, Lofgren M, Belusa R, Nielsen S, Aperia A. Perinatal changes in expression of aquaporin-4 and other water and ion transporters in rat lung. Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.003bc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampighi GA, Hall JE, Ehring GR, Simon SA. The structural organization and protein composition of lens fiber junctions. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;108:2255–2275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidel ML, Ambudkar SV, Smith BL, Agre P. Reconstitution of functional water channels in liposomes containing purified red cell CHIP28 protein. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7436–7440. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidel ML, Nielsen S, Smith BL, Ambudkar SV, Maunsbach AB, Agre P. Ultrastructure, pharmacologic inhibition, and transport selectivity of aquaporin channel-forming integral protein in proteoliposomes. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1606–1615. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinski T, Kaita H, Gilson T, Coghlan G, Philipps S, Lewis M. Linkage between the Colton blood group locus and ASSP11 on chromosome 7. Genomics. 1990;6:623–625. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90496-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T, Klaerke DA. Transport of water and glycerol in aquaporin 3 is gated by H+ Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:21631–21636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]