Abstract

Galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) evokes responses in muscles of both legs when bilateral stimuli are applied during normal stance. We have used this technique to assess whether asymmetrical standing alters the distribution of responses in the two legs. Subjects stood either asymmetrically with 75 % of their body weight on one leg or symmetrically with each leg taking 50 % of their body weight. The net response in each leg was taken from changes in ground reaction force measured from separate force plates under each foot. The net force profile consisted of a small initial force change that peaked at ∼200 ms followed by an oppositely directed larger component that peaked at ∼450 ms. We analysed the second force component since it was responsible for the kinematic response of lateral body sway and tilt towards the anode. In the horizontal plane, both legs produced lateral force responses that were in the same direction but larger in the leg ipsilateral to the cathodal ear. There were also vertical force responses that were of equal size in both legs but acted in opposite directions. When subjects stood asymmetrically the directions of the force responses remained the same but their magnitudes changed. The lateral force response became 2-3 times larger for the more loaded leg and the vertical forces increased 1.5 times on average for both legs. Control experiments showed that these changes could not be explained by either the consistent (< 5 deg) head tilt towards the side of the loaded leg or the changes in background muscle activity associated with the asymmetrical posture. We conclude that the redistribution of force responses in the two legs arises from a load-sensing mechanism. We suggest there is a central interaction between load-related afferent input from the periphery and descending motor signals from balance centres.

Following hemiplegia caused by stroke, abnormalities can be seen in standing posture and balance. Patients with hemiplegia often stand asymmetrically with the unaffected limb taking up to 75 % of their body weight (Bohannon & Larkin, 1985; Mizrahi et al. 1989; Chaudhuri & Aruin, 2000). Furthermore, there is an asymmetry of postural response in the two legs while maintaining standing balance. For example, the response to an external perturbation or to self-initiated upper or lower limb movements is often smaller in the hemiplegic limb (Di Fabio, 1997; Garland et al. 1997; Kirker et al. 2000). The degree that the initial stance asymmetry contributes to the postural response asymmetry is unclear. Therefore we have assessed the effects of asymmetrical standing on the bipedal distribution of postural responses in healthy control subjects.

We use galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) to evoke a postural response. The stimulus acts by increasing the firing rate of vestibular afferents on the side of the cathode and decreasing afferent firing on the side of the anode (Lowenstein, 1955; Goldberg et al. 1982; Courjon et al. 1987). Bilateral, bipolar GVS produces a characteristic lateral sway and tilt of the body in the direction of the anodal ear, which has been suggested to reflect engagement of the balance control system (Day et al. 1997). Electromyographic recordings have shown that the GVS-evoked response is distributed to muscles of both legs in standing subjects (Nashner & Wolfson, 1974; Britton et al. 1993). Such a stimulus, therefore, is suitable for studying the influence of stance asymmetry on the bipedal distribution of a postural response involved in balance control. By recording the ground reaction force responses under each foot we show that the contribution from the two legs to the net response is modified by the degree of initial stance asymmetry.

METHODS

Experiments were performed on twelve healthy male subjects without any neurological impairment. Subjects participated with informed consent and the approval of the local ethics committee according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Nine subjects participated in each experiment. The same subjects participated in experiments 1 and 3 (mean ± s.d.; age, 30.2 ± 8.9 years; body weight, 755.8 ± 86.0 N) and six of nine of these subjects also participated in experiment 2 (age, 33.4 ± 10.7 years; body weight, 740.0 ± 91.1 N). In all experiments practice trials were given as required and rests were provided after every 30 trials.

Experiment 1

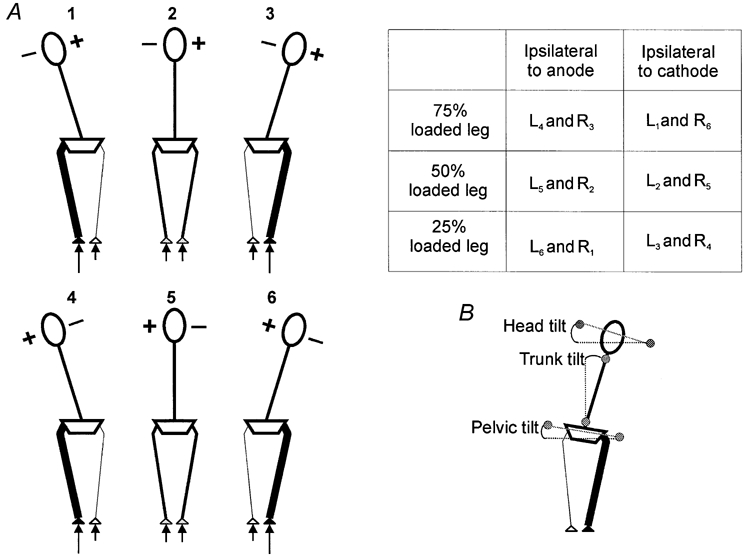

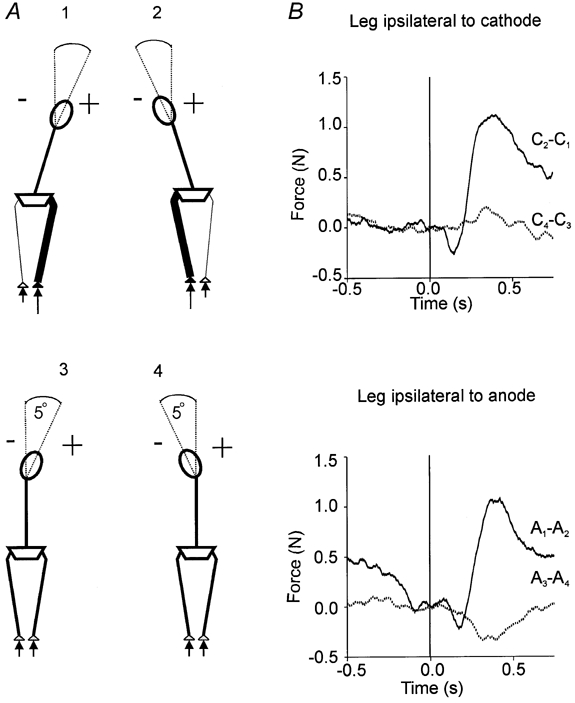

Subjects stood either asymmetrically, with 75 % of their total body weight taken by one leg and 25 % by the other, or symmetrically with each leg taking 50 % of body weight (Fig. 1A). Subjects stood with feet parallel and 5 mm apart. The feet were on separate force plates (Kistler types 9281B (left leg) and 9287 (right leg), Kistler Instrumente AG, CH-8408 Winterthur, Switzerland), which measured ground reaction force vectors. Body motion was measured using a 3-D motion tracking system (CODA mpx30, Charnwood dynamics, Rothley, Leicestershire, UK). Movements of the trunk were recorded using infrared emitting markers placed over C7 and L3 spinous processes. Head and pelvis movements were measured from pairs of markers fixed to horizontal bars that were attached to the posterior aspect of a rigid adjustable helmet and a semi-rigid belt.

Figure 1. Loading conditions and means of assessing data in experiment 1.

A, schematic dorsal view of subjects during six loading and stimulation conditions. The loaded leg is indicated by a thick line whilst the polarity of stimulation is adjacent to the head (+ indicates the side of the anode; – indicates the side of the cathode). The method of combining force plate data collected under identical loading and stimulation conditions is shown in the adjacent table. L and R refer to data collected from the left and the right force plates whilst the subscript refers to the condition number above each of the stick diagrams. B, definition of the angles measured. (Circles indicate the position of the markers used.)

A bar-graph display, consisting of a horizontal row of twenty red LEDs, was placed at eye level 100 cm in front of the subject. The display provided instantaneous feedback in 5 % steps of the percentage total vertical force applied through the right leg. Three green LED condition markers situated above the display indicated the point when the right leg took either 25, 50 or 75 % of the total body weight. Trial onset was indicated by a tone, followed by illumination of one of the three condition markers. When subjects had adjusted their weight appropriately using feedback from the display, they triggered the occlusion of vision by pressing a hand-held switch, which changed the state of liquid crystal spectacles from transparent to opaque (PLATO visual occlusion spectacles, Translucent technologies, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). After a 0.5-2.0 s random interval the collection of data commenced. After a further fixed 3 s baseline period, a 3 s 1 mA galvanic stimulus was applied bilaterally via electrodes (PALS plus, Nidd valley medical Ltd, Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, UK) fixed to the mastoid processes. Each recording lasted for a total of 9 s after which vision was restored. Two stimulus polarities were investigated resulting in a total of six conditions. Ten trials of each condition were randomly presented (60 trials total). Kinematic and force plate data were sampled at 200 Hz.

Experiment 2

This experiment was performed to control for the consistent 2-3 deg head tilt towards the side of the more loaded leg that was seen in the first experiment (see Results). The procedure differed from that used in experiment 1 in the following way. Using the bar-graph feedback display subjects stood with 50 % of their body weight on each leg. A horizontal bar on the subject's helmet was illuminated from behind to cast a shadow onto a target placed 200 cm in front of the subject. By tilting the head in the frontal plane the shadow could be aligned to one of three lines drawn on the target board. The lines subtended angles of 0 deg and ± 5 deg to the horizontal. Three head tilts were assessed randomly with the required tilt being indicated by the condition markers on the feedback display. Once the correct starting position had been attained subjects initiated a trial by pressing a hand-held switch as in experiment 1. GVS polarity and head tilt condition were randomly varied and a total of 60 trials (10 conditions per trial) were recorded.

Experiment 3

This experiment was performed to control for the change in muscle activity that occurred when subjects stood asymmetrically. Subjects were required to (i) stand symmetrically, (ii) stand asymmetrically, or (iii) stand symmetrically while contracting leg muscles to the same degree as that of the more loaded leg during the asymmetrical stand. The experiment was simplified by investigating only one type of asymmetrical stand in which the left leg took 75 % of the total body weight.

Surface EMG was recorded from the left and right soleus, lateral head of the gastrocnemius and tensor fascia lata (TFL). These muscles were chosen as they have been shown previously to make an important contribution to the response evoked by GVS under similar conditions (Day et al. 1997). The symmetrical and asymmetrical stands were accomplished as in experiment 1. To achieve EMG matching, the signals from left TFL and left soleus were rectified and low-pass filtered and displayed on an oscilloscope in front of the subject. The level of EMG activity that occurred in these muscles during the asymmetrical stand was marked on the screen. In the EMG matching condition subjects stood symmetrically using the bar-graph display for feedback as before. They then isometrically contracted the TFL and soleus bilaterally to achieve the required EMG level. Activation of TFL was controlled by exerting a bilateral abducting force of the legs. Activation of soleus was controlled by the subject leaning slightly forwards. When subjects were satisfied that the starting condition had been achieved they pressed a hand-held switch to start the trial. Thereafter the procedure was the same as for experiment 1 with the exception that GVS was applied for only 1 s. EMG data was pre-amplified (× 100) at a head box that was attached to the subject and then filtered (56-300 Hz), further amplified (× 500) and sampled at 1000 Hz. A total of 120 trials were recorded and the order of standing conditions and polarity of stimulation were randomized resulting in 20 trials per condition.

Analysis

All data was stored on-line and converted to text files for subsequent analysis. Head, trunk and pelvis tilt in the frontal plane were calculated as indicated in Fig. 1B. GVS resulted in a characteristic sway towards the side of the anode (see Results), kinetic and kinematic data from trials when the anode was on the left side were therefore inverted and averaged with those when the anode was on the right side. For experiments 1 and 2 lateral forces produced under the same loading and stimulus polarity conditions were averaged as indicated in Fig. 1A. In experiment 3 only data gathered from the left force plate were analysed. For all experiments the average lateral and vertical reaction forces were calculated between 250-450 ms post-stimulus onset when forces developed that resulted in the ensuing postural sway (see Results). EMG signals were rectified and the mean amplitude over the 3 s baseline period and 140-200 ms post-stimulus was determined, EMG response size was calculated relative to the EMG size over the baseline period.

Data were analysed using a repeated-measures general linear model (SPSS, version 10.0, SPSS Inc.) the factor being condition (3 levels per experiment). An additional factor of polarity (2 levels) was included when assessing data from each force plate. Corrections for sphericity were made where necessary and results were taken to be significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the response to GVS when standing symmetrically

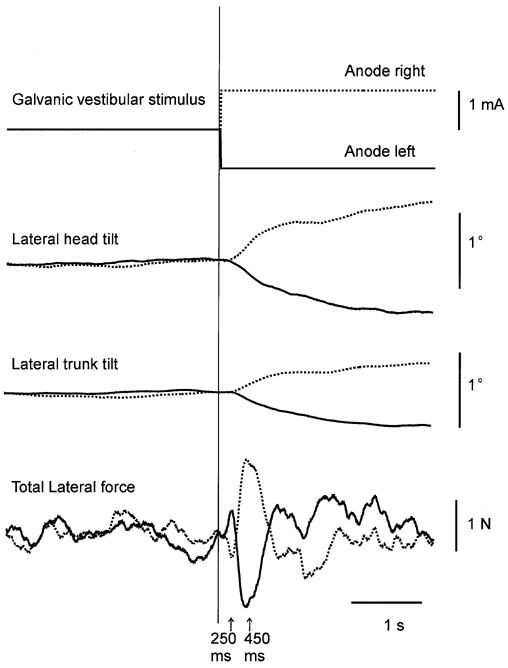

Subjects responded to GVS by swaying towards the side of the anode (Fig. 2). As shown previously (Day et al. 1997), the body motion was characterized by a tilt of body segments in the frontal plane with higher segments achieving greater tilt angles. This postural change was accomplished by generating a complex pattern of forces between each foot and the ground. The net force profile consisted of a small initial force change that peaked at ∼200 ms followed by an oppositely directed larger component that peaked at ∼ 450 ms (indicated by arrows in Fig. 2). The analysis will focus on the development of this second larger component of force between 250-450 ms since it was responsible for the observed postural change.

Figure 2. Group mean responses to GVS during symmetrical stance.

From top to bottom: timing of the galvanic vestibular stimulus, lateral head tilt, lateral trunk tilt and total lateral forces acting on the body, with the anode either on the right (dotted lines) or left side (continuous lines). Here and in subsequent figures the vertical line at 0 s indicates the time of stimulus onset.

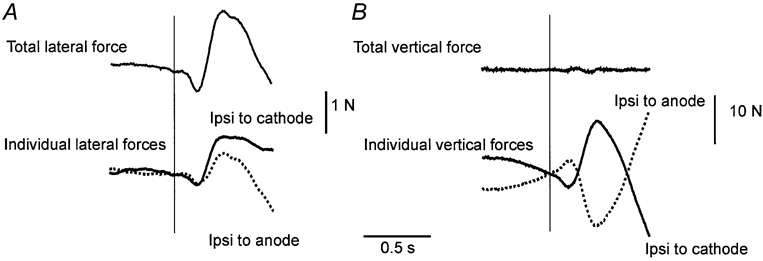

It is convenient to resolve the force under each foot into horizontal and vertical components. The lateral horizontal reaction forces acted on both legs in the same direction although the size of response tended to be higher and more sustained in the leg ipsilateral to the cathode (Fig. 3A). In the vertical direction the legs produced equal but oppositely directed force changes. The vertical force increased in the leg on the side of the cathode and decreased in the leg on the side of the anode (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Group mean force responses in each leg to GVS during symmetrical stance.

Lateral forces (A) and vertical forces (B) are indicated. Top: forces summed from the two legs. Bottom: forces acting on the leg either ipsilateral (Ipsi) to the anode (dotted lines) or ipsilateral to the cathode (continuous lines).

Effect of asymmetrical standing on the bipedal response to GVS

Subjects leant sideways in order to stand asymmetrically. This involved both lateral displacements and tilts of the head, trunk and pelvis (Table 1). With this asymmetrical posture GVS caused the body to sway towards the anode in a similar fashion to when standing symmetrically.

Table 1.

Variation in starting position during limb loading with 25 and 75% of their body weight (experiment 1)

| Legipsilateral to anode loaded by: | ||

|---|---|---|

| 75% of body wt | 25% of body wt | |

| Percentage body weight change reltive to symmetrical loading condition*† | +22.3 ± 1.2 | −22.3 ± 1.1 |

| Head tilt (frontal plane) (deg)† | +2.6 ± 0.9 | −3.0 ± 0.8 |

| Trunk tilt (frontal plane) (deg)† | +2.3 ± 0.5 | −2.4 ± 0.7 |

| Hip tilt(frontal plane) (deg)† | +1.4 ± 0.2 | −1.5 ± 0.2 |

Values are means ± standard deviation. Positions are given relative to that achieved during the symmetrical standing condition. The angles measured are indicated in Fig. 1B.

Indicates significant difference between conditions as assessed using a general linear model.

Data from the legipsilateral to the anode and ipsilateral to the cathode have been combined.

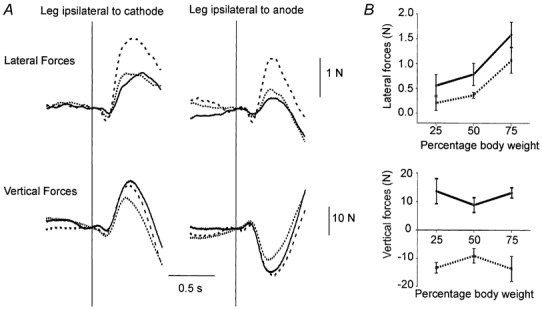

The net GVS-evoked lateral horizontal force summed from the two legs was not significantly affected by standing asymmetrically (F(2,16) = 1.9, P > 0.2). However, analysis of data from individual legs revealed differences. A leg that was more loaded produced greater lateral force (Condition, F(2,16) = 13.3, P < 0.01; Fig. 4A and B). There was also an effect of stimulus polarity with larger lateral forces being produced by the leg ipsilateral to the cathode (polarity, F(1,8) = 7.9, P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). There was no interaction between stimulus polarity and degree of loading.

Figure 4. Effect of asymmetrical stance on group mean force responses to GVS.

A, lateral (top) and vertical (bottom) force responses acting on the leg ipsilateral to the cathode (left) or to the anode (right) when the leg was loaded by 75 % (dashed line), 50 % (dotted line) or 25 % (continuous line) of body weight. B, group mean lateral (top) and vertical (bottom) forces acting on the leg 250-450 ms post stimulus onset under the three different loading conditions for the leg ipsilateral to cathode (continuous line) and the leg ipsilateral to anode (dotted line). Standard error of the mean is indicated.

The vertical force responses under the two feet were always of equal magnitude and oppositely directed, irrespective of the degree of initial stance asymmetry (polarity, F(1,8) = 32.0, P < 0.001). The vertical force increased in the leg ipsilateral to the cathode and decreased in the leg ipsilateral to the anode. During asymmetrical standing the magnitude of vertical force response was greater than during symmetrical standing (condition × polarity, F(2,16) = 9.2, P < 0.01, Fig. 4B).

Effect of lateral head tilt on the bipedal response to GVS

In experiment 1 a slight but significant tilt of the head in the frontal plane was present during asymmetrical standing. The head was tilted towards the more loaded leg by 2.9 deg on average (Table 1). To investigate whether this could be responsible for the changes in bipedal force responses we measured the effect of pure head tilt when subjects stood symmetrically (Fig. 5A, Table 2).

Figure 5. Effect of head tilt on group mean differences in lateral force responses to GVS.

A, schematic dorsal view to demonstrate the head tilt associated with limb loading in experiment 1 (top) and with symmetrical stance in experiment 2 (bottom). Note that conditions have been combined such that the anode always appears on the right (see Methods). B, responses expressed as difference traces in the leg ipsilateral to the cathode (top) and the leg ipsilateral to the anode (bottom). Each difference trace illustrates the lateral force when the head was tilted towards the leg minus the lateral force when it was tilted away from the leg in either experiment 1 (continuous line) or experiment 2 (dotted line). The force plate data used to calculate the differences are indicated next to each trace. C and A refer to force responses from the leg on the side of the cathode and anode respectively and subscripts indicate the condition number as shown in A. There were no significant differences in the traces prior to stimulus onset (F(1,8) = 0.007, P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Variation in starting position with different head tilts (experiment 2)

| Condition 1 Head laterally tilted towards anode | Condition 3 Head laterally tilted away from anode | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage body weight change relative to symmetrical loading condition*† | 0.4 ± 1.0 | −0.5 ± 1.4 |

| Head tilt(frontal plane) (deg)† | +4.9 ± 0.4 | −4.7 ± 0.5 |

| Trunk tilt(frontal plane)(deg) | +0.3 ± 0.5 | −0.3 ± 0.5 |

| Hip tilt(frontal Plane) (deg) | −0.02 ± 0.1 | +0.01 ± 0.1 |

Data are means ± standard deviation. Positions are given relative to that achieved during the symmetrical standing condition.

Indicates significant difference between conditions as assessed using a general linear model.

Data from the leg ipsilateral to the anode and ipsilateral to the cathode have been combined.

As in experiment 1 there were effects of stimulus polarity on the ensuing lateral and vertical forces. Thus the leg ipsilateral to the cathode produced a greater lateral force (polarity, F(1,8) = 22.2, P < 0.01) whilst the bipedal vertical force responses were equal in magnitude but oppositely directed (polarity, F(1,8) = 10.6, P < 0.05). There was no main effect of head tilt on the lateral ground reaction forces produced by the two legs in response to GVS but there was a significant interaction between polarity and side of head tilt (condition × polarity, F(1,8) = 3.5, P = 0.05). The leg ipsilateral to the cathode produced greater lateral force when the head was tilted towards rather than away from it, whereas the converse was observed for the leg ipsilateral to the anode. This effect is illustrated in Fig. 5B in which difference traces have been plotted. For comparison, equivalent difference traces have been plotted for the data of experiment 1. In this figure the effect of head tilt on its own is seen to be relatively small and insufficient to explain the greater lateral force response produced by the more loaded leg in experiment 1.

Effect of background muscle activity on the force and EMG responses to GVS

The difference in the response to GVS in the two legs when standing asymmetrically may have been due to differences in the degree of background muscle activation and hence excitability of the motoneurone pools through which the response ultimately acts. This was tested by getting subjects to stand symmetrically whilst isometrically contracting the hip abductors and soleus muscles to the same degree as seen when standing asymmetrically (Fig. 5A, Table 3). Subjects successfully performed this EMG matching task (Table 3).

Table 3.

Starting position parameters in experiment 3

| Condition 1 Left leg 75% loaded | Condition 3 Left leg 50% loaded, EMG matching | |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage body weight change relative to symmetrical loading condition† | 23.1 ± 1.5 | 0.6 ± 1.6 |

| Mean rectified TFL activity (μV)† | 19.7 ± 12.9 | 20.2 ± 11.2 |

| Mean rectified soleus activity (μV)† | 13.5 ± 9.3 | 14.8 ± 11.4 |

| Head tilt(frontal plane)(deg)† | −2.3 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| Trunk tilt(frontal plane)(deg)† | −2.0 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.3 |

| Hip tilt(frontal plane)(deg)† | −1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| Trunk tilt(sagittal plane)(deg)† | 0.0 ± 1.8 | 3.0 ± 2.8 |

Values are means ± standard deviation. Positions and EMG levels are given relative to that achieved during the symmetrical standing condition. Measures calculated over the 3 second baseline period.

Indicates signficant difference between conditons as assessed using a general linear model. Negative values of tilt indicate that the subject was leaning to the left in condition 1.

There were differences in initial posture between the experimental conditions. As with experiment 1, the asymmetrical stand was achieved by a lateral displacement and tilt of the body towards the more loaded left leg. In the EMG-matching condition subjects leant further forwards compared to the other conditions in order to activate soleus adequately (Table 3, Fig. 6A). Since the asymmetrical stand was restricted to a leftward body lean (see Methods), responses from the left leg only are presented.

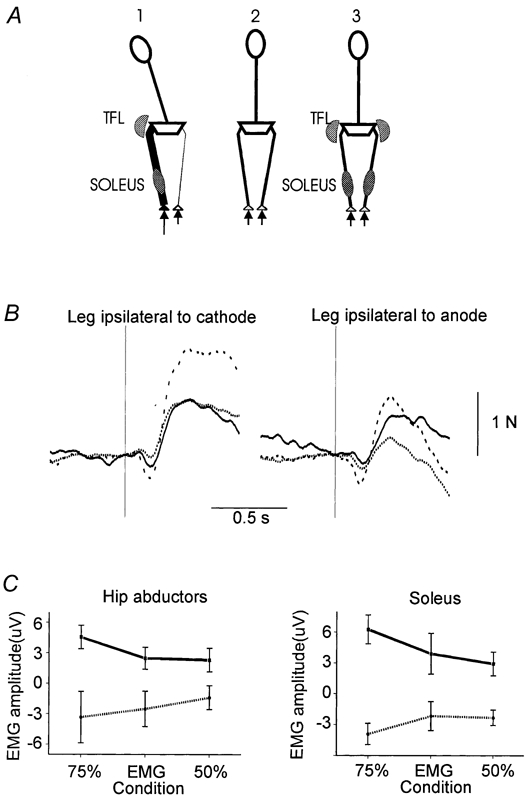

Figure 6. Effect of loading and isometric muscle activation on group mean lateral force responses and lower limb muscle responses to GVS.

A, schematic dorsal view indicating the initial starting conditions in experiment 3. Muscles indicated in conditions 1 and 3 were activated to the same degree. Loading of the lower limbs is indicated by the length of arrows beneath the feet. B, lateral forces acting on the left leg when it was either ipsilateral to the cathode (left) or ipsilateral to the anode (right). Traces show the responses when the left leg was loaded by 75 % (dashed line) or 50 % (dotted line) of body weight or when EMG levels were matched (continuous line). C, mean rectified EMG responses 140-200 ms post-stimulus relative to baseline for the left hip abductors (left) and left soleus (right) when the left leg was ipsilateral to the cathode (continuous line) or ipsilateral to the anode (dotted line). Standard error of the mean is indicated.

The stance condition had a significant effect on the lateral force response (condition, F(2,18) = 6.9, P < 0.01; Fig. 6B). A priori contrasts revealed that the evoked force was greater when subjects stood asymmetrically compared with when they stood symmetrically with matched EMG levels (a priori simple contrasts 75 % vs.EMG F(1,9) = 5.9, P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between a normal symmetrical stand and a symmetrical stand with elevated EMG levels (a priori simple contrasts 50 % vs.EMG; F(1,9) = 2.0, P > 0.2). As before, the lateral and vertical ground reaction forces were affected by stimulus polarity (polarity: lateral, F(1,8) = 18.7, P < 0.01, Fig. 6B; vertical, F(1,8) = 39.4, P < 0.001).

For both the hip abductors and soleus the main EMG response was seen 140-200 ms post-stimulation. Over this period the EMG response amplitude increased when muscles were ipsilateral to the cathode and decreased when ipsilateral to the anode (polarity: hip abductors, F(1,8) = 4.3, P = 0.07; soleus, F(1,8) = 20.5, P < 0.01, Fig. 6C). There was a significant interaction between stance condition and polarity (Fig. 6C) for both muscle groups (condition × polarity: hip abductors, F(2,16) = 6.42, P < 0.01; soleus F(2,16) = 5.2, P < 0.05). A priori contrasts revealed that the EMG response size (increment or decrement depending on polarity) was significantly greater in 75 % loaded condition compared with the symmetrically loaded condition (a priori contrasts: hip abductors, F(1,8) = 9.9, P < 0.05; soleus, F(1,8) = 16.9, P < 0.01). Further, the EMG response size was also greater in the 75 % condition compared with the EMG-matched condition (a priori contrasts: hip abductors, F(1,8) = 12.8, P < 0.01; soleus, F(1,8) = 5.6, P < 0.05).

These analyses of reaction forces and surface EMG responses suggest that the greater lateral force response produced by the more loaded leg in experiment 1 cannot be explained by the differences in background muscle activity.

DISCUSSION

Britton et al. (1993) showed that GVS evokes responses in those muscles that are engaged in maintaining balance. Accordingly, during bipedal stance EMG responses appear in muscles of both legs. Our measurements of bipedal force responses confirm this. One advantage of recording force is that it represents the net result of all the distributed muscle activities. This has allowed us to quantify the contribution from each leg to the overall response. With this approach we have been able to show that the force responses are not the same on both sides even when subjects stand symmetrically. When an asymmetrical stance is adopted the bipedal force responses are modified further.

Responses to GVS when standing symmetrically

The reaction forces acting under each foot had components in both the lateral and vertical directions. Temporally, there were two responses consisting of a small, early force change that peaked at ∼200 ms followed by a larger oppositely directed force that peaked at ∼450 ms. These are likely to be the mechanical consequences of the two oppositely directed components of the lower limb EMG response described previously (Britton et al. 1993; Fitzpatrick et al. 1994). Britton et al. (1993) speculated that two separate descending motor pathways mediate these two components, possibly via the reticulospinal and vestibulospinal tracts.

The later component of force change produces the main lateral sway and tilt of the body. Both legs contributed an increase in lateral force in the same direction with the force on the side of the cathode being higher and more sustained than that on the side of the anode. The lateral force produced by the anodal leg rapidly reversed in direction, which acted to decelerate the body and sustain a quasi-static tilted posture. The vertical force responses were equal and opposite under the two feet, which explains why vertical force changes are not seen when subjects stand on a single force plate. The vertical force response decreased in the leg on the side of the anode and increased in the leg on the side of the cathode.

The ground reaction force vectors are the net effect of torques that are actively and passively applied across multiple joints of the body. The ankle joints contribute to a lateral acceleration of the body by exerting evertor and invertor torques. The hip joints contribute by exerting abduction and adduction torques (Day et al. 1993). Indeed, lateral sway responses to GVS are accompanied by EMG responses both in ankle joint and in hip joint muscles (Day et al. 1997). The equal and opposite changes in vertical force under the two feet are similar to those observed during spontaneous lateral body sway of standing subjects (Winter et al. 1996). Winter et al. (1996) termed this a loading/unloading mechanism and proposed that it arises from active generation of hip abductor/ adductor torques. It is possible that the knee joints also contribute to such a loading/unloading mechanism by producing an effective lengthening/ shortening of the legs. This could be achieved by an extension of the knee on the side of the cathode and a flexion of the knee on the side of the anode. Thus the changes in lateral and vertical reaction forces caused by the vestibular stimulus are probably due to involvement of multiple muscles acting both proximally and distally.

Responses to GVS when standing asymmetrically

When subjects changed their posture so that one leg took more body weight than the other, the bipedal distribution of force response to GVS was altered. The vertical force responses remained equal and opposite under the two feet but increased in magnitude. The lateral force responses increased under the more loaded foot and decreased under the other foot such that the sum of the two remained approximately the same. At least part of this change in force distribution was actively achieved since hip and ankle EMG responses also changed with initial stance asymmetry.

The effect caused by asymmetrical stance did not seem to be due to the fact that the head was always tilted towards the more loaded leg. Such a change of head position in space would alter ongoing vestibular afferent activity, which could affect the response to GVS. However, simple head tilt on its own had only a minor effect on the response forces.

Asymmetrical stance was also accompanied by changes in the legs’ background EMG activities. The EMG activities were greater in the more loaded leg, which implies a higher excitability of the parent motoneurones. A given descending signal elicited by GVS might be expected to interact with a more excited motoneurone pool to produce a larger response size. This does not seem to be the explanation for our results since matching the EMG levels while maintaining a symmetrical stance did not produce equivalent responses to those obtained during asymmetrical stance. However, in this control experiment we are unable to rule out that voluntary bilateral activation of leg muscles, as used for EMG matching, altered the GVS-evoked input to motoneurones compared to asymmetrical stance.

A possible loading effect

Asymmetrical stance is associated with a change in loading of the legs as well as a change in body geometry. Further experiments are required to distinguish which of these two possible factors underlie the effects on the GVS-evoked response reported here. However, the factor we believe to be important is the degree of loading of the legs. Previously, Dietz and colleagues found that increased body loading led to an increase in the electromyographic (EMG) response of gastrocnemius to a backward platform perturbation (Dietz et al. 1989; Horstmann & Dietz, 1990). In those experiments variable loading was achieved using total body immersion to unload the body and then applying weighted jackets to achieve progressive loading. Loading effects on stretch-related soleus or gastrocnemius activity in stance or during gait has also been observed by other authors (Nashner, 1980; Dietz et al. 1992; Sinkjaer et al. 2000; Fouad et al. 2001). The source of the load-related afferent input remains unclear. There may be several sources of information, for example from muscle, tendon and joint receptors in the lower limbs and/or trunk and from cutaneous receptors on the plantar aspect of the foot (Duysens et al. 2000).

In conclusion, we suggest that the increase in the response size to GVS was caused by an interaction between load-related afferent information and the signal elicited by vestibular stimulation. Where this interaction occurs is uncertain. Load-related information modifies muscle response size in subjects with complete spinal cord injury (Harkema et al. 1997). This suggests that the spinal cord contains circuitry that processes load-related information. Spinal cord interneurones would be good candidates since our results seem to indicate that the interaction is not at the level of the spinal motoneurones. However, interactions at higher levels are also possible. The proposed interaction of load-related afferent information and a descending signal of supraspinal origin may partly explain why the effects of loading during gait re-training is less effective in complete as opposed to incomplete spinal cord injury (Dietz et al. 1994).Finally, the fact that the postural response is modified by the degree of lower limb loading has potential implications for interpreting balance response abnormalities following stroke where decrements in the postural response are often observed on the paretic side (Dietz & Berger, 1984; Rogers et al. 1993). Indeed, it has been shown that prior to step initiation the magnitude of the vertical and horizontal forces generated under the paretic leg varies according to the initial loading taken through that limb (Brunt et al. 1995). This raises the important question of whether such abnormalities of postural control are simply a secondary effect of an underlying stance asymmetry or a primary deficit of the postural control process caused by the central lesion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr R. Bedlington and Mr D. Buckwell for technical assistance. This work was funded by the Medical Research Council. J. Castellote was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport.

REFERENCES

- Bohannon RW, Larkin PA. Lower extremity weight bearing under various standing conditions in independently ambulatory patients with hemiparesis. Physical Therapy. 1985;65:1323–1325. doi: 10.1093/ptj/65.9.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton TC, Day BL, Rothwell J, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Postural eletromyographic responses in the arm and leg following galvanic vestibular stimulation in man. Journal of Physiology. 1993;94:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00230477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt D, Vander Linden DW, Behrman AL. The relation between limb loading and control parameters of gait initiation in persons with stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;76:627–634. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80631-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri S, Aruin AS. The effect of shoe lifts on static and dynamic postural control in individuals with hemiparesis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2000;81:1498–1503. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.17827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courjon JH, Precht W, Sutherling WW. Vestibular nerve and nuclei unit responses and eye movement responses to repetitive galvanic vestibular stimulation of the labyrinth in the rat. Experimental Brain Research. 1987;66:41–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BL, Cauquil A, Bartolomei L, Pastor MA, Lyon IN. Human body-segment tilts induced by galvanic stimulation: a vestibularly driven balance protection mechanism. Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:661–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BL, Steiger MJ, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Effect of vision and stance width on human body motion when standing: implications for afferent control of lateral sway. Journal of Physiology. 1993;469:479–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio RP. Adaptation of postural stability following stroke. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 1997;3:62–75. doi: 10.1080/10749357.1997.11781074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Berger W. Interlimb coordination of posture in patients with spastic paresis. Brain. 1984;107:965–978. doi: 10.1093/brain/107.3.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Colombo G, Jensen L. Locomotor activity in spinal man. Lancet. 1994;344:1260–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Gollhofer A, Kleiber M, Trippel M. Regulation of bipedal stance: dependance on ‘load’ eceptors. Experimental Brain Research. 1992;89:229–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00229020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Horstmann G, Trippel M, Gollhofer A. Human postural reflexes and gravity – an under water simulation. Neuroscience letters. 1989;106:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duysens J, Clarac F, Dietz V. Load-regulating mechanims in gait and posture: Comparative aspects. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:84–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R, Burke D, Gandevia SC. Task-dependent reflex responses and movement illusions evoked by galvanic vestibular stimulation in standing humans. Journal of Physiology. 1994;478:363–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad K, Bastiaanse CM, Dietz V. Reflex adaptations during treadmill walking with increased body load. Experimental Brain Research. 2001;137:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s002210000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland SJ, Stevenson TJ, Ivanova T. Postural responses to unilateral arm perturbation in young, elderly and hemiplegic subjects. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1997;78:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JM, Fernandez C, Smith CE. Responses of vestibular nerve afferents in the squirrel monkey to externally applied galvanic currents. Brain Research. 1982;252:156–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkema SJ, Hurley SL, Patel UK, Requejo PS, Dobkin BH, Edgerton VR. Human lumbrosacral spinal cord interprets loading during stepping. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;77:797–811. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann G, Dietz V. A basic posture control mechanism: the stabilisation of the center of gravity. Electroencephaplography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1990;76:165–176. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(90)90214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirker SGB, Jenner JR, Simpson DS, Wing A. Changing patterns of postural hip muscle activity during recovery from stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2000;14:618–626. doi: 10.1191/0269215500cr370oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein O. The effect of galvanic polarization on the impulse discharge from sense endings in the isolated labyrinth of the thornback ray (Raja clavata) Journal of Physiology. 1955;127:104–117. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi J, Solzi P, Ring H, Nisell R. Postural stability in stroke patients: vectorial expression of asymmetry, sway activity and relative sequence of reactive forces. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing. 1989;27:181–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02446228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM. Balance adjustments of humans while walking. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1980;44:650–664. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.4.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM, Wolfson P. Influence of head position and proprioceptive cues on short latency postural reflexes evoked by galvanic stimulation of the human labyrinth. Brain Research. 1974;67:255–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MW, Hedman LD, Pai Y-C. Kinetic analysis of dynamic transitions in stance support accompanyinh voluntary leg flexion movements in hemiparetic adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1993;74:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkjaer T, Andersen JB, Ladouceur M, Christensen LOD, Nielsen JB. Major role for sensory feedback in soleus EMG activity in the stance phase of walking in man. Journal of Physiology. 2000;523:817–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA, Prince F, Frank JS, Powell C, Zabjek KF. Unified theory regarding A/P and M/L balance in quiet stance. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:2334–2343. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]