Abstract

The lumbrical skeletal muscle fibres of mice exhibited electrically bistable behaviour due to the nonlinear properties of the inwardly rectifying potassium conductance. When the membrane potential (Vm) was measured continuously using intracellular microelectrodes, either a depolarization or a hyperpolarization was observed following reduction of the extracellular potassium concentration () from 5.7 mm to values in the range 0.76–3.8 mm, and Vm showed hysteresis when was slowly decreased and then increased within this range. Hypertonicity caused membrane depolarization by enhancing chloride import through the Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter and altered the bistable behaviour of the muscle fibres. Addition of bumetanide, a potent inhibitor of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter, and of anthracene-9-carboxylic acid, a blocker of chloride channels, caused membrane hyperpolarization particularly under hypertonic conditions, and also altered the bistable behaviour of the cells. Hysteresis loops shifted with hypertonicity to higher values and with bumetanide to lower values. The addition of 80 μM BaCl2 or temperature reduction from 35 to 27 °C induced a depolarization of cells that were originally hyperpolarized. In the range of 5.7–22.8 mm, cells in isotonic media (289 mmol kg−1) responded nearly Nernstianly to reduction, i.e. 50 mV per decade; in hypertonic media this dependence was reduced to 36 mV per decade (319 mmol kg−1) or to 31 mV per decade (340 mmol kg−1). Our data can explain apparent discrepancies in ΔVm found in the literature. We conclude that chloride import through the Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter and export through Cl− channels influenced the Vm and the bistable behaviour of mammalian skeletal muscle cells. The possible implication of this bistable behaviour in hypokalaemic periodic paralysis is discussed.

Cells can have two stable steady-state membrane potentials (Vm) under identical conditions in media with lowered potassium concentration (Gadsby & Cranefield, 1977; Mølgaard et al. 1980; Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1991, 1994). This was found in a variety of myocardiac and vascular cells, e.g. calf (Weidmann, 1956) and dog right ventricle trabecular cells (Gadsby & Cranefield, 1977), sheep Purkinje fibres (Carmeliet et al. 1987), human ventricular myocardial cells (McCullough et al. 1989), bovine aortic (Mehrke et al. 1991) and pulmonary artery endothelial cells (Voets et al. 1996). It was also observed in skeletal muscle fibres of frogs (Hodgkin & Horowicz, 1959; Nánási & Dankó, 1989), rats (Mølgaard et al. 1980) and mice (Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1991, 1994). Furthermore, it was found in a number of other cells, such as mouse macrophages (Gallin & Livengood, 1981) and rat (Sims & Dixon, 1989) and chicken osteoclasts (Ravesloot et al. 1989). This bistable behaviour, also called dichotomy or bimodality, is related to the negative slope conductance of the inward potassium rectifier (KIR; Gadsby & Cranefield, 1977). Some of the above cells were reported to switch from the hyperpolarized to the depolarized state (and vice versa) upon electrical stimulation in media with reduced potassium (Gadsby & Cranefield, 1977; Carmeliet et al. 1987).

We demonstrate here that this behaviour can also be evoked by reduction of potassium alone. If a cell becomes hyperpolarized when the potassium concentration () in the medium is lowered below 5.7 mm, then the cell membrane is regarded to be in a ‘switched-on’ state. However, if a cell becomes depolarized when is lowered below 5.7 mm, then the cell membrane is regarded as being in a ‘switched-off’ state and the at which such depolarization occurs is defined as the ‘switch-off value’ (Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1994). When is reduced slowly, one finds that the switch-off value is smaller than the ‘switch-on’ value in one and the same cell; this phenomenon we call ‘hysteresis’.

Furthermore, this study shows that other processes influencing Cl− movements across the plasmalemma, such as exposure to hypertonic media, inhibition of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and blocking the conductive Cl− channels, affect the electrical bistable behaviour of the muscle cells, as does Ba2+ block of KIR and a change in temperature from 27 to 35 °C. Some of these results have been presented in abstract form (Geukes Foppen et al. 1999).

METHODS

Preparation

Male and female white Swiss mice were housed and used in accordance with Dutch regulations concerning animal welfare. The mice were killed by cervical dislocation and the lumbrical muscle was removed from a hind foot as described earlier (Van Mil et al. 1997). The muscle bundle was stretched to a length slightly greater than the relaxed length and pinned down at the tendons in the measuring chamber. Experiments were started 30 min after the muscle was pinned down. Only superficial fibres were impaled. The lumbrical muscle was used throughout this study, unless otherwise stated. Whole bundles of extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and soleus and strips of diaphragm muscle were dissected and handled similarly.

Perfusion media and chemicals

The modified Krebs-Henseleit solution contained (mm): 117.5 NaCl, 5.7 KCl, 25.0 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2 and 5.6 glucose, saturated with humidified gas (95 % O2-5 % CO2); pH 7.35-7.45. concentrations were varied by equimolar replacement of NaCl by KCl or vice versa, thereby maintaining external Cl− concentration constant throughout (130.6 mm). Isotonic solutions had an osmolality of 289 mmol kg−1 (s.d. 6 mmol kg−1). All hypertonic solutions were made by addition of polyethyleneglycol (PEG) with a molecular weight of 400 Da (PEG 400), large enough to be impermeant. The most common hypertonic solutions contained either 9.7 g PEG per litre (319 mmol kg−1) or 18.6 g PEG per litre (340 mmol kg−1). A more hypertonic medium contained 38 g PEG per litre (398 mmol kg−1), and a slightly less hypertonic medium (372 mmol kg−1) was made by diluting the most hypertonic medium with isotonic solution. The osmotic values of all media used were expressed as osmolality, which was measured with a vapour-pressure osmometer (Wescor Model 5100C). Bumetanide and anthracene-9-carboxylic acid (9-AC) were added to the perfusion media in supramaximal concentrations (75 μM). 9-AC does not completely block the chloride conductance (GCl; Palade & Barchi, 1977) and its potency depends on the extracellular chloride concentration (Astill et al. 1996). However, 75 μM 9-AC generated the maximal effect in our experimental conditions. All chemicals were of analytical grade. Salts were supplied by Janssen Chimica (Geel, Belgium), PEG 400 by Merck and all other chemicals by Sigma.

Measuring chamber

The measuring chamber, made of Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), had a volume of approximately 0.1 ml and was continuously perfused (flow velocity 3 ml min−1). It was mounted on the object stage of an Olympus SZH microscope. Prewarmed solutions were transported to the chamber by means of a peristaltic pump (ISMATEC ISM 726, Ismatec SA, Zürich, Switzerland). Just before entering the chamber, the solution temperature was adjusted to 35.0 ± 0.5 °C by passing it along a resistor heated by electrical current. Temperature was continuously measured with a K-type miniature thermometer (Keithley 871A, Cleveland, OH, USA) in the chamber. Turning the current off induced a drop in temperature to 27 ± 1 °C. For fast temperature changes, a flush-through stainless-steel capillary was used to rapidly decrease (within 3 s) the temperature to 25 ± 0.5 °C. The drop in temperature caused the bicarbonate-buffered solutions to acidify by less than 0.1 pH unit. The temperature dependence of ΔVm caused by solution changes was calculated using the equation Q10 = (ΔVm2/ΔVm1)α, where α = (10/T2 – T1), T is the temperature (°C) and T2 > T1, and where ΔVm2 and ΔVm1 are the membrane potential changes resulting from solution changes at temperatures T2 and T1 in the same cell.

Measurement procedure and the definition of Vm

Fine-tipped glass microelectrodes (containing 3 m KCl; tip resistance 25-80 MΩ) were used to measure Vm. They were all pulled on a Brown and Flaming puller (Sutter P 87, Sutter, Novato, CA, USA). Criteria for recordings to be considered representative and definition of Vm have been described previously (Van Mil et al. 1997). The output of the microelectrode amplifier (WPI, M4-A) and the potential of the reference bath microelectrode were sampled (1 kHz) using LABView 3.1 (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The data over 1 s were averaged and stored. We frequently used staircase protocols, where we did not switch back to control solution but continued to change the solution composition (for example see Fig. 1). In the hysteresis measurements we also used staircase protocols, making very small steps by mixing different proportions of 2.85 and 0.76 mm -containing solutions in steps of 10 %.

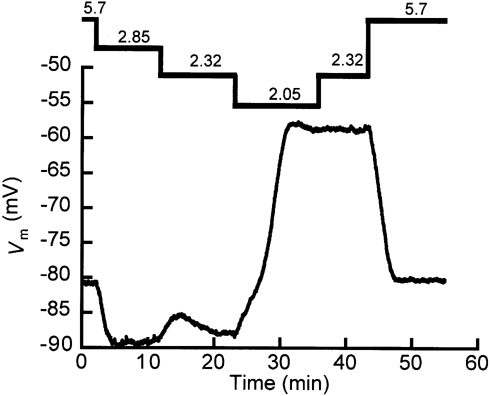

Figure 1. Effects of stepwise changes in on the membrane potential (Vm).

The numbers at the top are the extracellular potassium concentrations (mm). First, was reduced in steps until the cell depolarized massively (ΔVm = 30 mV at t ∼ 24 min), after which was increased in a stepwise manner. The switch from a of 2.32 to 2.05 mm gives a clear illustration of the definition of ‘switch-off’ value; below 2.32 mm the cell ceased to remain in the A-state. So the switch-off value of is in the range between 2.03 and 2.32 mm. The bistable behaviour exhibited by the cell is manifested at a of 2.32 mm because there are two stable Vm values: -87.9 mV (at t ∼ 20 min) and -58.9 mV (at t ∼ 40 min). Re-addition of the medium with 5.7 mm caused the cell to return to its original Vm value.

Membrane state

The status of the cell membrane in the range between 0.76 and 3.8 mm was determined based on the value of Vm in relation to a threshold calculated by averaging an equal number of the most positive and the most negative Vm values for a specific at given osmolality. If the Vm was more negative than the threshold value, then the cell membrane was considered to be in the A-state and if Vm was more positive than the threshold value, then the membrane was considered to be in the B-state. This method for ascertaining the A- or B-state of the membrane is similar to the half-amplitude threshold technique routinely used to separate the open and the closed states of single channels (Colquhoun, 1994).

Statistics

Steady-state data, obtained at a particular and osmolality, are presented as means ± s.e.m. with the number of observations (n) in parentheses. The number of animals (N) is given when it differs from n. When mean values are compared, the significance was assessed using either Student's t test (n > 6) or the Mann-Whitney U test (n < 6). Unless indicated otherwise, P < 0.05 was assumed to indicate a significant difference. P was not calculated when n was less than 4. The correlation coefficient (r) is given when a curve was fitted to data.

RESULTS

Bistable behaviour is a cellular property

The staircase protocol for changing in Fig. 1 reveals that bistable behaviour is a property of an individual cell. First, was decreased stepwise from 5.7 mm to a value that made the cell depolarize to about – 60 mV (when was made 2.05 mm the cell switched off). Then we increased to 2.32 mm again. The cell remained depolarized, whereas with the same concentration before the switch off it was hyperpolarized. Therefore, at the same concentration (here 2.32 mm) we found two different membrane potentials, one hyperpolarized (A-state) and one depolarized (B-state) with respect to the value in normal medium. The results in Fig. 1 were reproduced in seven other fibres (N = 7) with similar results.

Hysteresis exhibited by Vm in response to small changes in isotonic, hypertonic and bumetanide-containing media

We also applied staircase protocols with smaller steps of approximately 0.2 mm (see Methods), and waited 4 min at each or 45 min when the switch value was crossed. After a ‘control’ staircase protocol in isotonic media was completed, a second staircase protocol was attempted in either hypertonic media (Fig. 2A) or isotonic media containing bumetanide (Fig. 2B). The completion of two successive full staircase protocols in one cell took about 3 h. In Fig. 2A the result of such a double staircase protocol is displayed. First, was reduced with an end-point of 0.76 mm and the switch-off value was 1.6 mm. Then was increased, returning to 5.7 mm; the switch-on value was 2.64 mm. In every full experiment (n = 10) the switch-on value was higher than the switch-off value. After the control experiment, as shown in Fig. 2A, we conducted the experiment in a hypertonic solution (340 mmol kg−1). Now we found a switch-off value of 2.85 mm and a switch-on value of 3.14 mm. The hysteresis loop was narrower than in isotonic media and shifted to a higher .

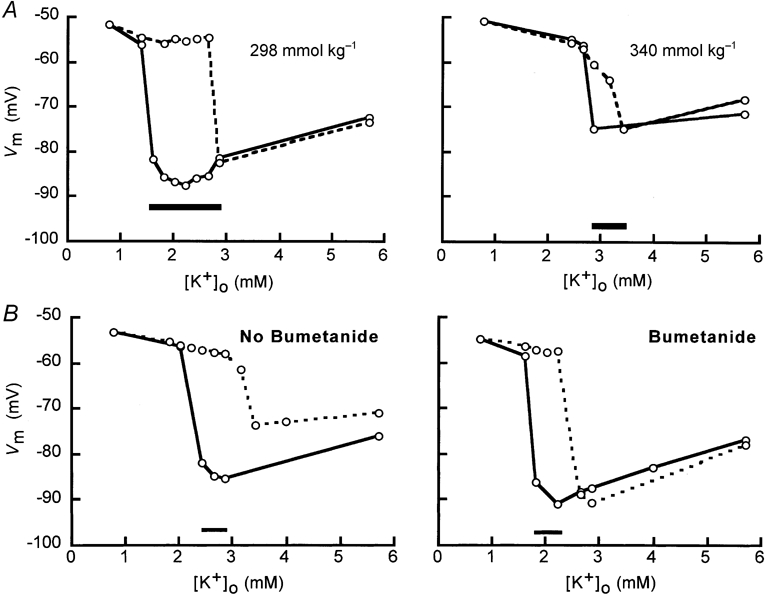

Figure 2. Hysteresis in isotonic and hypertonic solutions and in media containing bumetanide.

A, hysteresis in isotonic and hypertonic media in the same cell. Vm of the cell exhibited two stable values when was decreased and then increased in small steps. The hysteresis loop in isotonic media is shown in the left panel and the hysteresis loop at 340 mmol kg−1 in the right panel. In both panels, the data with decreasing are connected by continuous lines and the data with increasing by dashed lines. The bar at the bottom of each panel indicates the range of where hysteresis occurred. B, hysteresis of Vm in isotonic media without and with bumetanide. In the left panel, for isotonic mediawithout bumetanide, and in the right panel, for isotonic media containing bumetanide, was decreased and then increased in small steps. The data with decreasing are connected by continuous lines and the data with increasing by dashed lines. The last three data points of the increasing part of the staircase protocol in the isotonic media differ from the values expected on the basis of the results of decreasing part. However, when was 5.7 mm, Vm was -71.2 mV. This value is still sufficiently negative according to the criterion for a correct impalement (Van Mil et al. 1997). The bar at the bottom of each panel indicates the range of where hysteresis occurred.

Bumetanide shifted the hysteresis loop to lower values (Fig. 2B). The switch-off values decreased from a control value of 2.43 to 1.81 mm in bumetanide-containing media and the switch-on value decreased from 3.14 to 2.22 mm.

Similar recordings were obtained from three more cells in hypertonic media and two more cells in the presence of bumetanide. Also several other recordings (n = 4) where the cell membrane was damaged before completing the hysteresis loop further support this conclusion. Thus it appears that the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter can facilitate the closure of KIR at higher .

The dependence of Vm on and medium osmolality

The steady-state relationship between Vm and was determined at three osmolalities (289, 319 and 340 mmol kg−1; Fig. 3A). Because the previous results demonstrated bistable behaviour in media with lowered , we separated our data into two groups: hyperpolarized cells in the A-state and depolarized cells in the B-state. All mean Vm values of the A- and B-state with the same and osmolality differed significantly from one another (P < 0.01; see Fig. 3A). In hypertonic solutions, cells switched off at higher . For cells in the B-state all slopes of the Vm- relation were similar and small. In the range between 5.7 and 22.8 mm (indicated by the horizontal bar in Fig. 3A) the slopes decreased with increasing osmolality from 50 mV per decade () at 289 mmol kg−1 to 36 mV per decade at 319 mmol kg−1 and 31 mV per decade at 340 mmol kg−1.

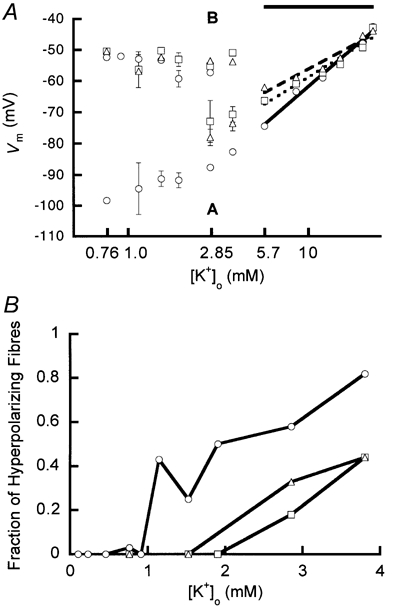

Figure 3. The influence of and osmolality on the membrane state.

A, Vm as function of at 3 different osmolalities. The osmolalities used were 289 (isotonic, ○), 319 (□) and 340 mmol kg−1 (▵). In the range of bistable behaviour, data were separated into two groups (A and B; see Methods). Group A: Vm is dependent (‘conductive-KIR’ state); group B: Vm is independent (‘non-conductive KIR’ state). The slopes of the Vm- relation in the range between 5.7 and 22.8 mm (below the horizontal bar) decreased upon increasing osmolality. A semilogarithmic function was used to fit these data. The following slopes were found: 50 mV per decade () (continuous line at 289 mmol kg−1, r = 0.99), 36 mV per decade (dotted line at 319 mmol kg−1, r = 0.97) and 31 mV per decade (dashed line at 340 mmol kg−1, r = 0.97). All slopes of B-state fibres were similar and small. Error bars represent s.e.m. and are in most cases smaller than the markers. For all determinations n and N > 5 (except for 1.14 mm; 289 mmol kg−1: A-state 3, 3 and B-state 4, 4 (n, N)). B, fraction of hyperpolarizing fibres as a function of at different osmolalities. The osmolalities were the same as in A. For every fraction larger than 0, n > 10 (with the exception of isotonic 1.14 mm, where n = 7).

Since Fig. 3A does not show how many cells hyperpolarized at lower values, we also plotted the fraction of hyperpolarized cells as a function of (Fig. 3B). This fraction diminished when the tonicity increased. Frequently, we found that in one muscle bundle some fibres hyperpolarized while others depolarized with the same . On visual inspection no correlation could be found between fibre appearance and the status of the membrane.

Vm can also be related to osmolality. At a of 5.7 mm a slope of 230 ± 10 mV mol−1 kg (n = 1.6, N = 96) was found with the three standard osmolalities. This dependence was also calculated at values of 0.76 and 15 mm, and in a solution containing 5.7 mm and 80 μM Ba2+. These three solutions caused cells to depolarize to approximately -55 mV (B-state). In 0.76 mm the dependence was 48 ± 6 mV mol−1 kg (n = 14,N = 10), in 15 mm it was 3.8 ± 12 mV mol−1 kg (n = 14,N = 8) and in Ba2+-containing media it was 50 ± 10 mV mol−1 kg (n = 7,N = 5). All these values differ significantly (P < 0.001) from the sensitivity with a of 5.7 mm. These results corroborate our previously published data with mannitol as the osmotic agent (Siegenbeek van Heukelom et al. 1994).

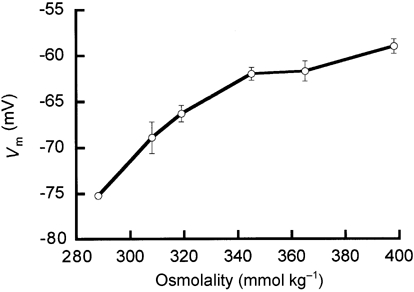

We also measured cell responses at 5.7 mm in a wider range of hypertonicity than we reported earlier (Van Mil et al. 1997), but the preparation often deteriorated after exposure to osmolalities above 370 mmol kg−1. This deterioration was observed in two ways. First, the depolarization was not always reversible and second, on microscopic inspection, the preparation frequently changed from transparent to nontransparent. Therefore, we have only a limited number of successful experiments ‘above the (patho)physiological range’ (approximately 350 mmol kg−1; Hoffmann & Simonsen, 1989). Vm as a function of osmolality saturated at approximately -58 mV (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Increased osmolality causes cell depolarization in the presence of 5.7 mm .

The error bars represent s.e.m.; at 289 mmol kg−1 the error was smaller than the marker.

Bistable behaviour at a of 0.76 mm differs in various muscles

We set out to examine the variation in bistable behaviour among muscles. Therefore, we compared the fraction of hyperpolarizing cells when was decreased from 5.7 to 0.76 mm in lumbricalis, EDL, soleus and diaphragm muscle. At this concentration we found that in the lumbrical muscle 2.7 % of the cells hyperpolarized (15 hyperpolarizations, n = 5.3, N = 2.0). In the EDL this was 70 % (39 hyperpolarizations, n = 56,N = 30), in the soleus 32 % (9 hyperpolarizations, n = 28,N = 21) and in diaphragm muscle 30 % (3 hyperpolarizations, n = 10,N = 6). Compared to the lumbrical muscle, cells of all other muscles responded differently (P < 0.05 using the χ2 test). Even though the switch-off value measured using staircase protocols in lumbricalis was between 1.3 and 2.5 mm (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3A), it can evidently be as low as a of 0.76 mm, in rare cases.

Bumetanide, 9-AC and hypertonicity modulate the bistable behaviour

To demonstrate better that chloride transport influences the relation between Vm and , we conducted experiments in which we applied bumetanide or 9-AC at various values of and osmolality (see Table 1). At an osmolality of 340 mmol kg−1 and 5.7 mm , bumetanide had a larger effect than 9-AC (P < 0.05). Both agents had smaller effects when was 15 mm or when cells were depolarized in low- media. After addition of bumetanide, the application of 9-AC still induced a small hyperpolarization (ΔVm = -1.5 ± 0.2 mV, n = 9,N = 8,P < 0.05) that was also evident in the hypertonic medium (340 mmol kg−1; ΔVm = -0.6 ± 0.2 mV, n = 6,N = 5,P < 0.05). This suggests an additional uphill Cl− import (see Discussion).

Table 1.

Vm changes (ΔVm) induced by application of bumetanide or 9-AC

| ΔVm (mV) (n; N) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bumetanide in 289 mmol kg−1 | Bumetanide in 319 mmol kg−1 | Bumetanide in 340 mmol kg−1 | 9-ACin 289 mmol kg−1 | 9-AC in 340 mmol kg−1 | |

| (mM) | |||||

| 0.76 B | 0.0(5; 4) | −1.0 (4)* | −1.0 (5;3)* | −1.1 (9; 8)* | −1.4 (2) |

| 1.52 B | −0.3 (4) | — | — | — | — |

| 2.85 A | −2.8 (4;3)* | — | — | — | — |

| 2.85 B | −2.5 (6)* | — | — | −1.5 (6;4)* | — |

| 5.7 | −3.7 (52;47)* | −7.1 (7;6)* | −12.9 (31;25)* | −3.0 (32;21)* | −5.2 (28;22)* |

| s.e.m. at 5.7 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 15 | 0.3 (7;5) | −0.9 (5) | −2.5 (5) | −0.1 (4) | −0.3 (5) |

The changes were measured in media with 3 different osmalalitites and several concentrations of . The letters A or B after the potassium concentration refer to the state of the cell. All data are compared to zero

P < 0.05. The s.e.m. values of the data in the row for 5.7 mM are given in the next row. In 340 mmol kg−1 solution and with a mM the ΔVm due to 9-AC is significantly less than found with bumetanide (P < 0.01). Other s.e.m. values are not presented, because the numbers were either small or the ΔVm was smaller than 1 mV. Vm at a of 15 mM was approximately −53 mV.

Addition of bumetanide or 9-AC in the presence of Ba2+ (either in isotonic or hypertonic media) resulted in very small or nonsignificant hyperpolarizations; cells deteriorated quickly with the combined exposure to Ba2+, hypertonicity and bumetanide. Addition of bumetanide in normal medium caused a hyperpolarization not only in lumbrical muscle cells (-3.7 mV, Table 1), but also in cells from the diaphragm muscle (-2.9 ± 0.8 mV, n = 7,N = 6), soleus (-2.9 ± 1 mV, n = 4) and EDL (-2.8 ± 0.7 mV, n = 6,N = 5).

The effects of bumetanide and 9-AC on the bistable behaviour can also be demonstrated using the staircase protocol. Figure 5 demonstrates that cells which depolarized on decreasing from 5.7 to 2.85 mm (at t = 10 min) could hyperpolarize in the presence of bumetanide (at t ∼ 55 min), in response to the same reduction. While the application of bumetanide during the depolarized state was ineffective (see Fig. 5 at t ∼ 20 min) to switch on the cells depolarized from the A-state to the B-state (-55.9 mV, n = 2) due to the wash-out of bumetanide. The choice of 2.85 mm was made because even at this concentration cells could depolarize (see Fig. 3B) and this concentration is slightly above the estimated half-maximal for the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter (approximately 2 mm; Isenring & Forbush, 1997). When the medium was changed to a of 0.76 mm, cells switched off even in the presence of bumetanide (n = 8,N = 7, see also Fig. 2B).

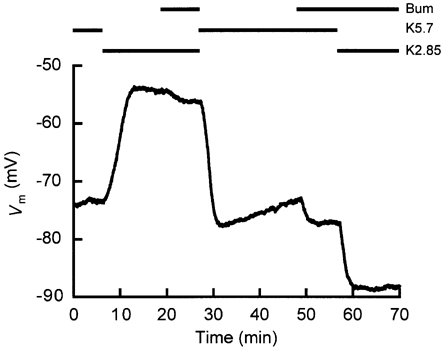

Figure 5. Influence of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter on bistable behaviour.

A reduction of from 5.7 to 2.85 mm induced a depolarization to the B-state (t ∼ 10 min). Application of bumetanide caused the cell to hyperpolarize slightly, without switching the cell membrane to the A-state (t ∼ 20 min). However, the cell remained in the A-state when bumetanide was added (at t ∼ 49 min) before the same reduction (t ∼ 57 min). The experimental protocol is depicted above the recording, where K5.7 and K2.85 represent the values of 5.7 and 2.85 mm, respectively, and Bum represents the application of bumetanide. Note that the two Vm values at t ∼ 26 and t ∼ 67 min are very different, though the composition of the extracellular solution is the same. In 4 cells, the average Vm values obtained thus in the A- or B-state with 2.85 mm in the presence of bumetanide differed significantly: -87.4 ± 1.9 and -55.3 ± 1.3 mV, respectively.

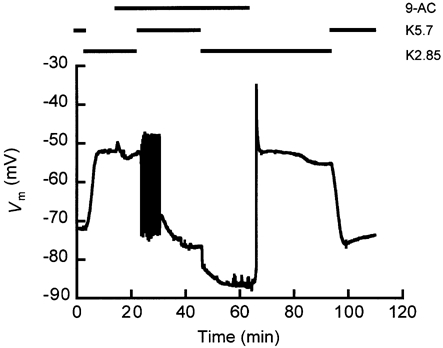

With the staircase protocol we found that addition of 9-AC, given before the reduction, caused a cell to hyperpolarize (in Fig. 6 at t ∼ 45 min), in contrast to the depolarization observed in the absence of 9-AC when was reduced (at t ∼ 5 min). All cells we studied showed the same pattern; when 9-AC was given before the reduction to 2.85 mm, they hyperpolarized (Vm = -86.8 ± 2.4 mV, n = 3), but not when 9-AC was given after the reduction (Vm = -54.4 ± 3.3 mV, n = 3). Bistable behaviour was never observed when was reduced to 0.76 mm (n = 7). Reducing in the presence of 9-AC sometimes induced oscillations of Vm, most probably because of the removal of the damping effect exerted by GCl. In Fig. 6 such oscillations are shown, when was switched from 2.85 to 5.7 mm (t = 23.28 min). We also sometimes found spikes that we identified as myotonic discharges because we frequently lost the cell at that moment. In Fig. 6 at t ∼ 60 min spikes started to manifest themselves in the presence of 9-AC and the GCl blocker was removed before the cell was damaged.

Figure 6. Chloride conductance influenced bistable behaviour.

Note the two stable Vm values found with a of 2.85 mm (K2.85 in the experimental protocol depicted above the recording) in the presence of 9-AC, at t ∼ 23 min (Vm ∼ -53 mV) and t ∼ 60 min (Vm ∼ -87 mV). In this figure, oscillations occurred during the response of Vm to the switch of from 2.85 to 5.7 mm (t ∼ 23 min) in the presence of 9-AC. At t ∼ 60 min spikes were manifesting and 9-AC was washed out at t = 63 min. This protocol was carried out three times (N = 3).

Effects of Ba2+ on electrical bistable behaviour

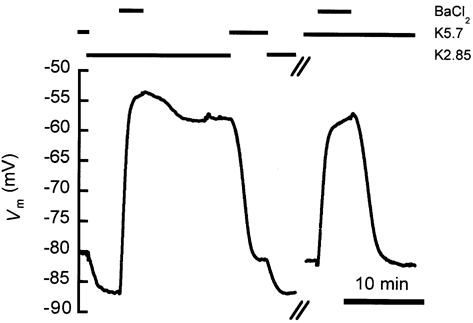

Since Ba2+ blocks the current through KIR we also studied the effect of washing out Ba2+ from the preparation. Figure 7 shows that in normal medium the cell repolarized from the B-state to the A-state when Ba2+ (80 μM) was washed out. This was not the case when was 2.85 mm (n = 4). The repolarization after washing Ba2+ out in normal medium with 5.7 mm was not influenced by 9-AC (n = 5) or hypertonicity (n = 5,N = 4).

Figure 7. Influence of barium on the bistable behaviour of a cell.

In media with 2.85 mm (left part of the figure) as well as with 5.7 mm (right part of the figure), 80 μM Ba2+ induced the cell to switch off. Upon washing out Ba2+, the cell did not return to the A-state with a of 2.85 mm (n = 4), but it always returned to the A-state in 5.7 mm (n = 32,N = 23). The experimental protocol is depicted above the recording.

The effects of temperature

Data on the effects of hypertonicity and the introduction of bumetanide or 9-AC at 35 and 27 °C in hypertonic media with a of 5.7 mm are compared in Table 2. The experiments were carried out at 340 mmol kg−1 to increase the responses to bumetanide and 9-AC (see Table 1). The depolarizations induced by hypertonicity and the hyperpolarizations induced by bumetanide were significantly smaller at 27 °C compared to those at 35 °C. Remarkably, the hyperpolarizations due to 9-AC in hypertonic media were increased at lower temperature (Table 2). The cell responses to 80 μM Ba2+ at 35 and 27 °C did not differ significantly (P > 0.05, n = 6,N = 5).

Table 2.

Responses (ΔVm) to hypertonicity, bumetanide and 9-AC at 35 and 27 °C

| ΔVm (mV) (n; N) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertonicity 340 mmol kg−1 | Bumetanide in 340 mmol kg−1 | 9-AC in 340 mmol kg−1 | |

| At 35 °C | 17.8 ± 2.0(6) | −13.8 ± 1.4(7) | −4.9 ± 1.1(6;4) |

| At 27 °C | 7.9 ± 0.9(6) | −8.7 ± 1.5(7) | −9.2 ± 1.3(6;4) |

| Apparent Q10 | 3.0 ± 0.6(6) | 2.1 ± 0.4(7) | 0.6 ± 0.2(6;4) |

All responses were measured at a of 5.7 mM: at 27 °C they differed significantly from the paired values at 35 °C (P < 0.05). At 27 °C the responses induced by bumetanide and 9-AC did not differ significantly. The temperature sensitivity is given as ‘apparent Q10’, i.e. the average of the Q10 values determined in individual cells; it therefore deviates from the value determined from the averages as given in this table.

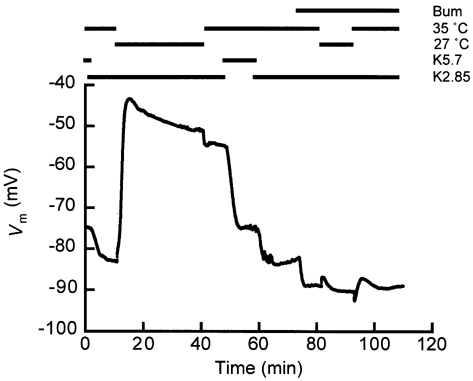

The effects of temperature changes are illustrated in Fig. 8, which shows one of seven similar recordings. Temperature was rapidly changed (approximately 3 s) from 35 to 27 °C and vice versa. When cells were cooled in a medium with a of 2.85 mm, they switched off (ΔVm = 37 ± 3 mV, n = 6). However, on one occasion a cell did not switch off; we found Vm = -88.1 mV (35 °C), decreasing to -86.6 mV (27 °C) and then increasing to -89.9 mV (35 °C). When a steady state was reached at 27 °C (Vm = -48 ± 3 mV, n = 6), the temperature was increased again to 35 °C. Two cells hyperpolarized completely to approximately -82 mV and four did not (ΔVm = -4 ± 4 mV). Together with the results of other recordings, less complete than the one in Fig. 8, in ten depolarized cells at 27 °C we found a switch to the A-state on increasing temperature (ΔVm = -34 ± 1 mV) on six occasions but not on four others (ΔVm = -5 ± 3 mV). This bistable behaviour was never found when was 5.7 mm (n = 10).

Figure 8. Temperature reduction can induce the switch off.

Cells normally switched off on temperature reduction from 35 to 27 °C with a of 2.85 mm (at t ∼ 12 min in this figure; see protocol indications above the recording) and could not repolarize on warming up again (at t ∼ 45 min). Thus, at 35 °C and with a of 2.85 mm, owing to its bistable behaviour the cell had two stable values of Vm, at t ∼ 10 min (Vm ∼ 84 mV) and at t ∼ 45 min (Vm ∼ 55 mV). The change in temperature was achieved in approximately 3 s. As shown in Fig. 5, the switch off could be prevented by inhibition of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter. Six similar recordings (N = 6) of the first part (until approximately 60 min) and three (N = 3) of the last part were obtained.

Figure 8 (from approximately 70 min onwards) also illustrates, like Fig. 5, that the addition of bumetanide can aid a cell to maintain the A-state on reduction of . This was found in all cells we tested with this protocol (ΔVm = 1 ± 1.7 mV, n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Bistable behaviour expressed as two stable membrane potentials has been observed for different types of cells in media with reduced potassium concentration with respect to control media and it is generally agreed that this behaviour is caused by the properties of the KIR (see Introduction). Gadsby & Cranefield (1977) could switch heart cells by electrical stimulation through an intracellular electrode from a non-conductive KIR state to a conductive state and vice versa. Because skeletal muscle cells are too large to demonstrate the switch by such stimulation, we demonstrated here similar bistable behaviour by perfusion changes or temperature jumps. This behaviour occurred over only a small range of potassium concentrations and it was influenced by chloride transport across the cell membrane. Chloride accumulation will occur as the outcome of Cl− entry through the secondary active Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and electrodiffusional passive efflux through GCl. If Cl− is accumulated above its equilibrium potential, then passive efflux of Cl− will occur, which contributes to depolarization of the cell, and this will increase the switch-off to a value that can be physiologically relevant. When KIR is blocked by barium, the more negative Vm values are apparently not attainable. This suggested that a conductive KIR is essential for maintaining the A-state. In skeletal muscle, the best candidate for the inward potassium rectifier is the strongly rectifying Kir2.1 (Barrett-Jolley et al. 1999), for the chloride channel underlying GCl it is ClC-1 (Pusch & Jentsch, 1994) and for the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter it is the bumetanide-sensitive cotransporter 2 (BSC2; Delpire et al. 1994) or the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1; Payne et al. 1995).

How does Cl− transport influence the bistable behaviour of muscle cells?

As mentioned earlier, electrical bistable behaviour of the cell is caused by the properties of KIR, which is the dominant element of the potassium permeability (PK), as described by the following equation (Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1994):

where Po is a residual, KIR-independent potassium permeability, which makes Vm become about -50 mV when KIR is closed. This is the reversal potential for the equimolar exchange of potassium and sodium. PKIR,max specifies the maximal steady-state permeability of KIR. It is divided by the square root of and the Boltzmann partition function that describes the kinetic behaviour of KIR (Hille, 1992). Vs gives the steepness of the voltage dependence. This expression fits the experimental data of Standen & Stanfield (1978). Owing to the Boltzmann distribution, KIR already opens at Vm values slightly less negative than the potassium equilibrium potential, EK. Without chloride transport, the equations (Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1994) describing the balance of cations and the activity of the Na+-K+-pump suffice to explain the bistable behaviour and hysteresis. Experiments with bumetanide exemplify this situation.

The Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and large chloride conductance present a depolarizing influence on the membrane potential. Uphill import of chloride through the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter will lead to accumulation of chloride in the cell and the equilibrium potential of chloride (ECl) will be positive with respect to Vm. Because of the large chloride conductance, the difference (Vm – ECl) is small. Nevertheless, the depolarizing influence of ECl on Vm leads to an increase of Vm- EK in the denominator of the Boltzmann equation (Van Mil, 1998). As the exponential in the denominator increases, PK decreases, because the KIR slides down its permeability-voltage relation. This process can force KIR to close regeneratively, and Vm attains a new steady-state value of approximately -50 mV, where PK ∼ Po.

The above-mentioned mechanism is enhanced in hypertonic solutions because of two collaborating effects. First, cell shrinkage will occur, though it must be so small that we could not detect it visually. This shrinkage by itself concentrates potassium and chloride in the cell and leads to an increase in Vm – EK, because EK becomes more negative and ECl more positive with respect to Vm. Second, stimulation of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter by hypertonicity enhances the chloride accumulation in the cell. ECl and Vm will become less negative. The coupled K+ import will simultaneously make EK more negative. Therefore, hypertonicity will promote the regenerative closure of KIR, as mentioned above.

A full description can only be given by solving all equations involved simultaneously (Geukes Foppen et al. 2001). These equations do not explain why the Vm of cells with closed KIR do not demonstrate strong dependence on osmolality in all cases. However, small variations were observed sometimes (see Fig. 5 at t ∼ 20 min, when addition of bumetanide evoked a small negative ΔVm). Two possible processes might be the reason. First, due to the reduction of Vm the driving force for uphill transport, the sodium gradient, is been substantially reduced. Second, the closure of KIR impedes the efflux of potassium and influences the intracellular concentrations of sodium and potassium unfavourably for uphill transport of chloride (see also the next paragraph). Only the measurement of intracellular cation concentrations can provide data that document whether the electrical or chemical component of the sodium gradient is most important.

Effects of 9-AC and bumetanide compared

Bumetanide and 9-AC both reduced the chloride efflux as a positive current into the cell, bumetanide by reducing the driving force and 9-AC by reducing GCl. With both agents the cell remained more easily in the A-state. When was 5.7 mm their effect appeared to be optimal. When cells exhibited bistable behaviour, application of bumetanide or 9-AC did not induce cells in the B-state to switch to the A-state. In the B-state Vm – EK is so large that, most probably, the Na+-K+-pump is not powerful enough to repolarize the cell and reopen the KIR. When was 15 mm the influences of hypertonicity, bumetanide or 9-AC were small because the potassium gradient across the membrane had been reduced considerably and Vm approached ECl.

The effect of 9-AC on the membrane potential consists of two elements, the inhibition of GCl (with a hyperpolarizing effect) and the subsequent augmented chloride accumulation (with a depolarizing effect). In isotonic medium, the hyperpolarizations due to 9-AC and bumetanide compare well (-3.0 vs. 3.7 mV). However, in hypertonic media (340 mmol kg−1) the mean ΔVm due to 9-AC is -5.2 mV, and due to bumetanide -12.9 mV, most probably because 9-AC is not a complete blocker of GCl (Palade & Barchi, 1977).

The fact that 9-AC induced a ΔVm ∼ -1 mV in both iso- and hypertonic media containing bumetanide, might indicate an additional bumetanide-insensitive Cl− entry (Davis, 1996; Chipperfield et al. 1997). A second explanation may be that this residual potential change is caused by a small HCO3− permeability (PHCO3) of the ClC-1 channels. Rychkov et al. (1998) mentioned that PHCO3/PCl of ClC-1 is 0.027. The equilibrium potential of protons is between -10 and -30 mV (Aickin & Thomas, 1977), which is equal to the equilibrium potential of HCO3− (EHCO3) in bicarbonate buffers with constant PCO2. These values for PHCO3/PCl and EHCO3 are sufficient to account for a shift in reversal potential for ClC-1 of approximately 1 mV. The alternative explanation, that bumetanide does not inhibit all the active Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporters, seems unlikely because the concentration we used appears to be supramaximal (Van Mil et al. 1997).

Temperature dependence of Cl− transport

At 27 °C, ΔVm induced by hypertonicity and by bumetanide were both about half the values observed at 35 °C. This suggests that the activity of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter is highly temperature dependent, in accordance with the finding of Lytle et al. (1998). Therefore, at 35 °C cells might accumulate more chloride than the 1.4 mm at room temperature reported by Aickin et al. (1989). If GCl is temperature insensitive, as reported by Palade & Barchi (1977) in rat diaphragm muscle (25-40 °C), it is understandable why the hyperpolarization induced by 9-AC depended inversely on temperature. At 27 °C and 340 mmol kg−1 the effects of bumetanide and 9-AC were equal (see Table 2), because the two elements of the effect of 9-AC, hyperpolarization due to the reduction of GCl and depolarization due to accumulation of chloride, made them comparable. At 35 °C, however, the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter was more vigorous and achieved more chloride accumulation with blocked GCl.

Discrepancies in ΔVm in skeletal muscle reported in the literature

Our data can explain apparent discrepancies in ΔVm found in the literature. The inverse temperature dependence of hyperpolarization induced by 9-AC can explain why Aickin et al. (1989) reported a value of 10-15 mV at room temperature, whereas we found 3 mV. Donaldson & Leader (1984) reported that in media of 290 mmol kg−1 there was no chloride accumulation in the EDL of the mouse, whereas Dulhunty (1978), using 335 mmol kg−1, concluded that chloride is accumulated actively in the same preparation. Additionally, different ΔVm/Δ values were reported for rat soleus muscle and for mouse EDL. For soleus Mølgaard et al. (1980) reported a ΔVm/Δ of 52.5 mV per decade at 288 mmol kg−1, while Chua & Dulhunty (1988) found a sensitivity of 36 mV per decade at 335 mmol kg−1. As for the EDL of mice, Siegenbeek van Heukelom (1991) measured at 289 mmol kg−1 55 mV per decade, whereas Dulhunty (1980) found 36 mV per decade at 335 mmol kg−1. In the present study, in mouse lumbrical muscle fibre, we found a decline of ΔVm/Δ from 50 mV per decade in 289 mmol kg−1 to 31 mV per decade in 340 mmol kg−1. From our results we conclude that, taking into account chloride transport and its dependence on tonicity and temperature, it is possible to explain the discrepancies in these data in the literature.

Physiological role

Though intracellular Mg2+ or polyamines appear to be the rectifying agents of KIR (Nichols & Lopatin, 1997), we only studied the influence of monovalent ion transport systems on Vm as a parameter of total cell behaviour.

Gallant (1983) concluded that treatment of mammalian skeletal muscle cells with Ba2+ induced a number of effects similar to those observed during hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. Ba2+ application can prevent excessive loss of potassium but jeopardizes contractile force development, as is the case after exercise or during an episode of hypokalaemic periodic paralysis (Clausen & Overgaard, 2000). The reduced potassium permeability mentioned by Gallant (1983) can be interpreted as the closure of the KIR. Along with our earlier observations (Siegenbeek van Heukelom, 1991, 1994; Van Mil et al. 1995), we conclude that our present observations might provide additional insight into hypokalaemic periodic paralysis (Barchi, 1994). At lower temperatures, as is the case in the body extremities, the closure of KIR will be most marked. Individual cells with closed KIR will accumulate potassium, thus reducing the extracellular potassium concentration in restricted spaces. In turn, this reduction in extracellular potassium can cause the closure of KIR in the neighbouring cells and consequently these cells may also depolarize, thus increasing the number of depolarized cells. Although this bistable behaviour of the cells is mainly caused by the highly nonlinear character of KIR, it is nevertheless susceptible to influences of other transport mechanisms, as shown in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank F. H. Geukes Foppen, J. A. Groot, W. J. Wadman and D. L. Ypey for their comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aickin CC, Betz WJ, Harris GL. Intracellular chloride and the mechanism for its accumulation in rat lumbrical muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1989;411:437–455. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC, Thomas RC. Micro-electrode measurement of the intracellular pH and buffering power of mouse soleus muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1977;267:791–810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astill D, St J, Rychko VG, Clarke JD, Hughes BP, Roberts ML, Bretag AH. Characteristics of skeletal muscle chloride channel ClC-1 and point mutant R304E expressed in Sf-9 insect cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1280:178–186. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi RL. The muscle fiber and disorders of muscle excitability. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Uhler ME, editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular Cellular and Medical Aspects. New York, NY, USA: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 703–722. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Jolley R, Dart C, Standen NB. Direct block of native and cloned (Kir2. 1). inward rectifier K+ channels by chloroethylclonidine. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;128:760–766. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet E, Biermans G, Callewaert G, Vereecke J. Potassium currents in cardiac cells. Experientia. 1987;43:1175–1184. doi: 10.1007/BF01945519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield AR, Davis JPL, Harper AA. Sodium-independent inward chloride pumping in rat cardiac ventricular cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:H735–739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua M, Dulhunty AF. Inactivation of excitation-contraction coupling in rat extensor digitorum longus and soleus muscles. Journal of General Physiology. 1988;91:737–757. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.5.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen T, Overgaard K. The role of K+ channels in the force recovery elicited by Na+-K+ pump stimulation in Ba2+-paralysed rat skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology. 2000;527:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. Practical analysis of single channel records. In: Ogden D, editor. Microelectrode Techniques. The Plymouth Workshop Handbook. 2. London, UK: Mill Hill; 1994. pp. 101–140. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JPL. Evidence against the contribution by Na+-Cl− cotransport to chloride accumulation in rat arterial smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1996;491:61–68. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Rauchmann MI, Beier DR, Hebert SC, Gullans SR. Molecular cloning and chromosome localization of a putative basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter from mouse inner medullary collecting duct (mIMCD-3) cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:25677–25683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson PJ, Leader JP. Intracellular ionic activities in the EDL muscle of the mouse. Pflügers Archiv. 1984;400:166–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00585034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulhunty AF. The dependence of membrane potential on extracellular chloride concentration in mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1978;276:67–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulhunty AF. Potassium contractures and mechanical activation in mammalian skeletal muscles. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1980;57:223–233. doi: 10.1007/BF01869590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Cranefield PF. Two levels of resting potential in cardiac purkinje fibers. Journal General Physiology. 1977;70:725–746. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.6.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant EM. Barium-treated mammalian skeletal muscle: similarities to hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. Journal of Physiology. 1983;335:577–590. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallin EK, Livengood DR. Inward rectification in mouse macrophages: evidence for a negative resistance region. American Journal of Physiology. 1981;241:C9–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1981.241.1.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geukes Foppen RJ, Van Mil HGJ, Bier M, Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. Hysteresis of mouse skeletal muscle membrane potential in response to varying medium potassium. Physiological Research. 1999;48:S73. [Google Scholar]

- Geukes Foppen RJ, Van Mil HGJ, Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. Osmolality influences bistability of membrane potential under hypokalaemic conditions in mouse skeletal muscle: an experimental and theoretical study. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 2001;130:533–538. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Horowicz P. The influence of potassium and chloride ions on the membrane potential of single muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1959;148:127–160. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann EK, Simonsen LO. Membrane mechanisms in volume and pH regulation in vertebrate cells. Physiological Reviews. 1989;69:315–382. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenring P, Forbush B., III Ion and bumetanide binding by the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:24556–24562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle C, McManus TJ, Haas M. A model of Na-K-2Cl cotransport based on ordered ion binding and glide symmetry. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:C299–309. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough JR, Chua WT, Rasmussen HH, Ten Eick RE, Singer DH. Two stable levels of diastolic potential at physiological K+ concentrations in human ventricular myocardial cells. Circulation Research. 1989;66:191–201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrke G, Pohl U, Daut J. Effects of vasoactive agonists on the membrane potential of cultured bovine aortic and guinea-pig coronary endothelium. Journal of Physiology. 1991;439:277–299. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mølgaard H, Stürup-Johansen M, Flatman JA. A dichotomy of the membrane potential response of rat soleus muscle fibres to low extracellular potassium concentrations. Pflügers Archiv. 1980;383:181–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00581880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nánási PP, Dankó M. Paradox response of frog muscle membrane to changes in external potassium. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:157–161. doi: 10.1007/BF00580958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lopatin AN. Inward rectifier potassium channels. Annual Reviews of Physiology. 1997;59:171–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade PT, Barchi RL. Characteristics of the chloride conductance in muscle fibers of the rat diaphragm. Journal of General Physiology. 1977;69:325–342. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JA, Xu JC, Haas M, Lytle CY, Ward D, Forbush B., III Primary structure, functional expression, and chromosomal localization of the Bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-Cl cotransporter in human colon. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:17977–17985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Jentsch TJ. Molecular physiology of voltage-gated chloride channels. Physiological Reviews. 1994;74:813–827. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravesloot JH, Ypey DL, Vrijheid-Lammers T, Nijweide PJ. Voltage-activated K+ conductances in freshly isolated embryonic chicken osteoclasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:6821–6825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychkov GY, Pusch M, Roberts ML, Jentsch TJ, Bretag AH. Permeation and block of the skeletal muscle chloride channel, ClC-1, by foreign anions. Journal of General Physiology. 1998;111:653–665. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.5.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. Role of the anomalous rectifier in determining membrane potentials of mouse muscle fibres at low extracellular K+ Journal of Physiology. 1991;434:549–560. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. The role of the potassium inward rectifier in defining cell membrane potentials in low potassium media, analyzed by computer simulation. Biophysical Chemistry. 1994;50:345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Siegenbeek van Heukelom J, Van Mil HGJ, Poptsova MS, Doumaid R. What is controlling the cell membrane potential? In: Gnaiger E, editor. What is Controlling Life? Modern Trends in Biothermokinetics. Vol. 3. Innsbruck, Austria: Innsbruck University Press; 1994. pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sims SH, Dixon SJ. Inwardly rectifying K+ current in osteoclasts. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:C1277–1282. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.6.C1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standen NB, Stanfield PR. Inward rectification in skeletal muscle: A blocking particle model. Pflügers Archiv. 1978;378:173–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00584452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mil HGJ. Analysis of a model describing the dynamics of intracellular ion composition in biological cells. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos. 1998;8:1043–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mil HGJ, Geukes Foppen RJ, Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. The Influence of bumetanide on the membrane potential of mouse skeletal muscle cells in isotonic and hypertonic media. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:39–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mil HGJ, Kerkhof CJM, Siegenbeek van Heukelom J. Modulation of the Isoprenaline-induced membrane hyperpolarization of mouse skeletal muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;116:2881–2888. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15940.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Membrane currents and the resting membrane potential in cultured bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:95–107. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidmann S. Elektrophysiologie der Herzmuskelfaser. Bern, Switzerland: Huber; 1956. [Google Scholar]